4.1. Optimal Water and N Management

In lettuce production, reductions in yield are commonly associated with water applications below crop evapotranspiration requirements [

17,

28,

43,

44], due to a well-established non-linear relationship between yield response and irrigation levels [

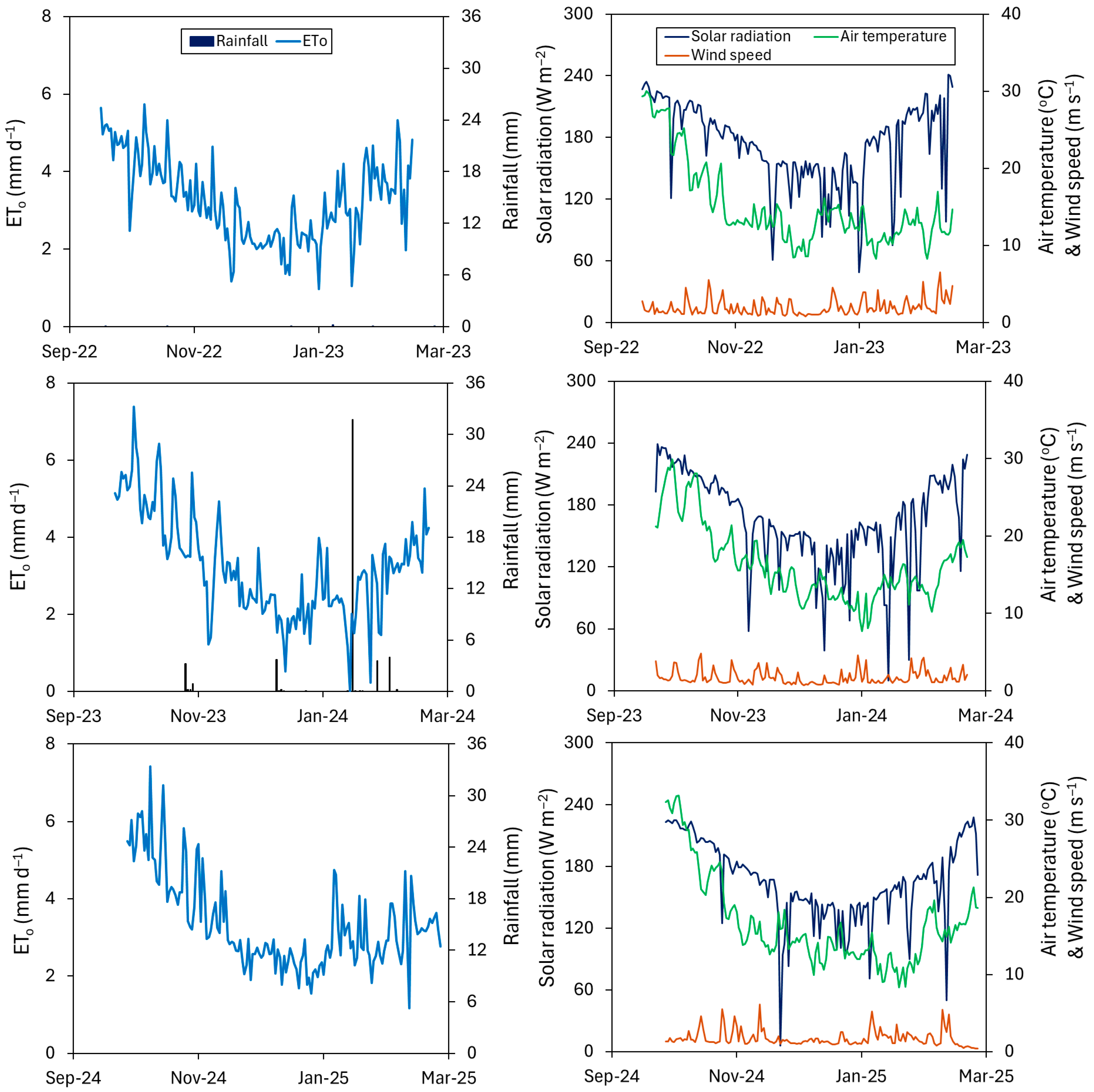

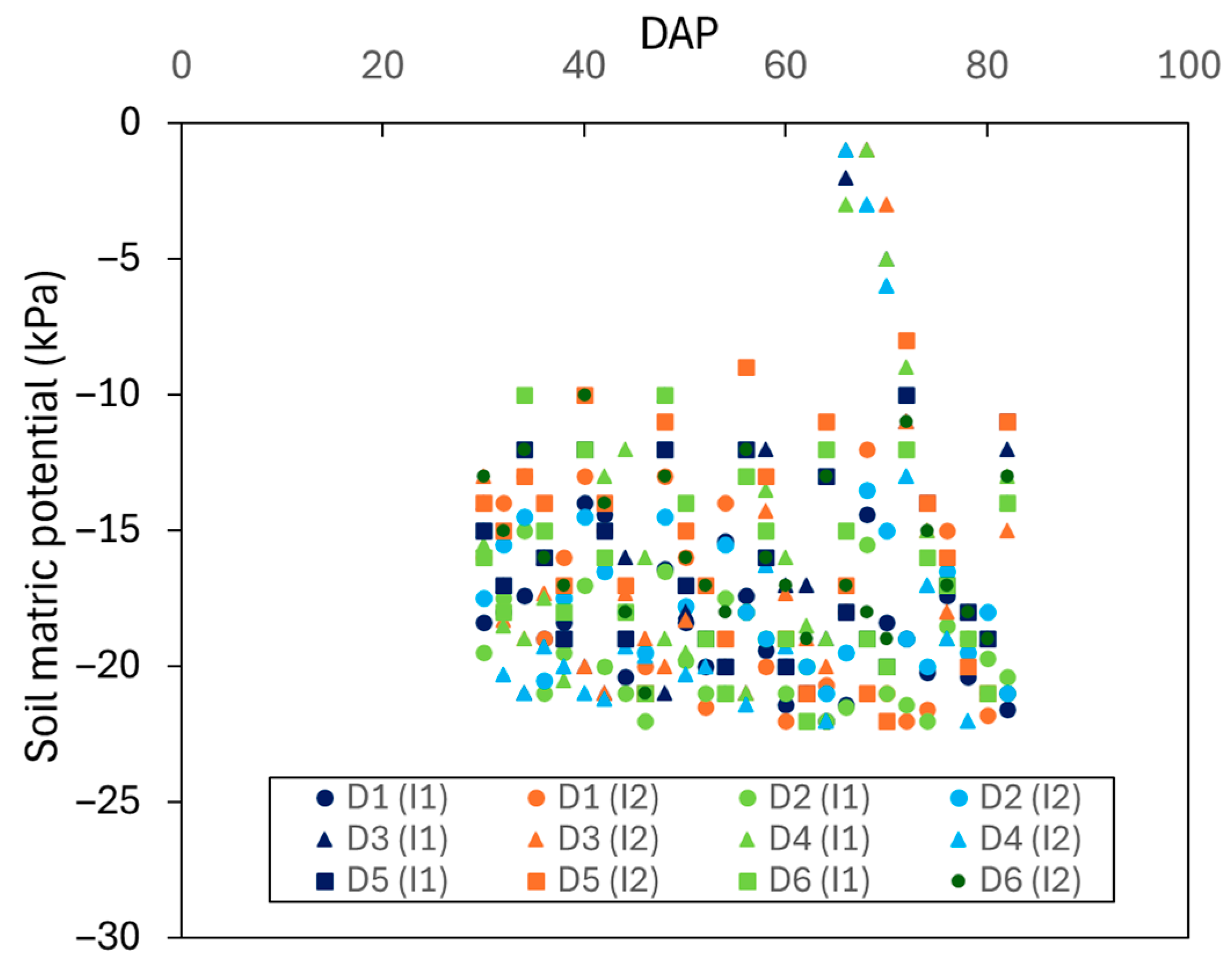

17]. In the present study, no deficit irrigation treatments were imposed, and soil matric potential measurements indicated that water stress was unlikely to have occurred during the experimental period (

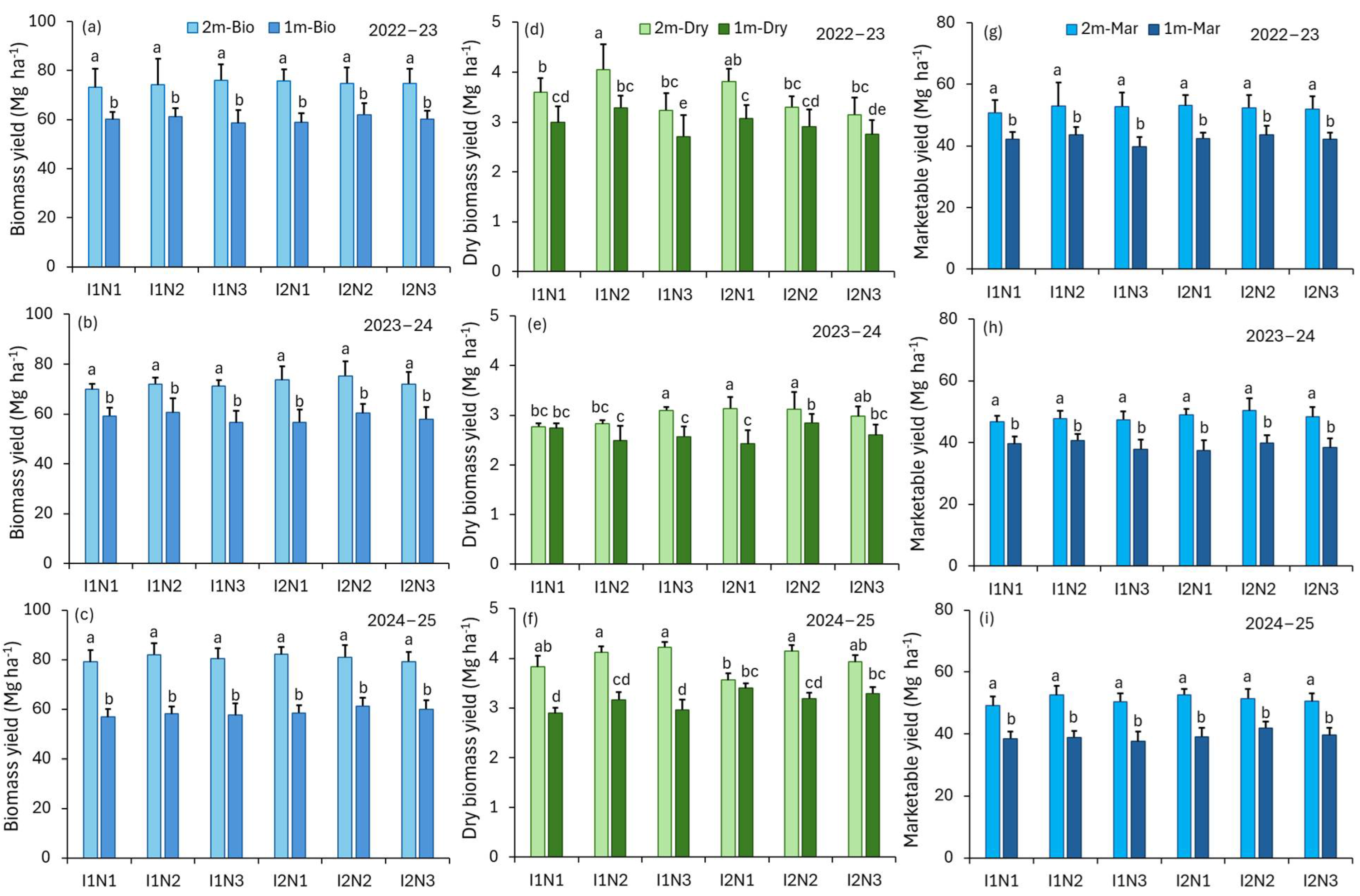

Figure 2). Additionally, no statistically significant differences in fresh biomass and marketable yield were observed across treatments receiving up to 25% more irrigation water and N application rates ± 20% of CM-based recommendations (

Figure 3). The lack of yield or growth differences between the 100% ET and 125% ET irrigation treatments suggest that the 100% ET level estimated by CropManage was sufficient to meet crop water requirements under the environmental and soil conditions of this study. However, this finding does not imply that 100% ET is excessive, as crop water needs can vary across seasons, soil textures, and climatic conditions. Because the tested irrigation range did not include deficit levels (<100% ET), the threshold at which water stress begins to impact lettuce yield could not be identified. Future research including irrigation levels below 100% ET is needed to determine the onset of water-stress responses.

The absence of a significant yield response to varying N inputs is consistent with previous studies that reported negligible effects of N fertilization rate (a wide range of applications more than 78 kg N ha

−1) on lettuce fresh and dry biomass accumulation [

6,

10,

15,

17,

44,

45,

46], thereby supporting the findings of this study.

The results of the trials suggest that implementing water and N rates recommended by CM could optimize biomass production and marketable yield in desert lettuce. This is consistent with findings from previous studies conducted in California’s Salinas Valley [

36,

37]. However, the water and N application rates identified in this study are lower than those reported in a study from Yuma, Arizona, which aimed to maximize lettuce yields under sprinkler irrigation [

5]. Similarly, the N rates are also lower than those recommended for baby green romaine lettuce production in Brazil [

44].

In this study, irrigation requirements ranged from 204 to 244 mm over a growing season of 83–90 days, which is lower than the 234–314 mm range reported by [

47] for furrow-irrigated lettuce cultivated over 63–107 days in Yuma, Arizona. Differences in irrigation methods and growing season duration are likely the primary factors contributing to variations in crop water use. In contrast, the irrigation amounts observed in this study exceed the 185–247 mm range reported in a more recent study from the Salinas Valley [

29].

The inverse relationship between WUE and applied irrigation volume observed here is supported by evidence from previous studies [

45,

48]. An average WUE of 300 kg ha

−1 mm

−1 for biomass yield was recorded under 100% ET irrigation treatments, closely matching values reported in an earlier study conducted in the Salinas Valley [

28].

In the present study, lettuce NUE based on dry biomass ranged from 20.2 to 40.1 kg kg

−1, substantially higher than the 2.9–10.7 kg kg

−1 reported in previous field study under Mediterranean conditions [

26], where the researchers noted that NUE was very low irrespective. This marked difference indicates that N utilization in our experiments was considerably more efficient, likely reflecting variations in cultivar selection, soil fertility, irrigation management, or N application timing. These results demonstrate that optimized agronomic practices and cropping systems, as implemented in our trials, can substantially enhance the conversion of applied N into marketable biomass, thereby mitigating the inefficiencies observed in previous studies.

The results showed a relatively wide range of N accumulated in lettuce plants across the trials and seasons at harvest, ranging from 99 kg N ha

−1 (treatment I1N2 in the 2023–2024 1 m wide bed trial) to 150 kg N ha

−1 (treatment I2N3 in the 2 m wide bed trial of the 2024–2025 season). Comparison of N applied and N uptake values across the trials (

Table 3 and

Table 4), together with the lack of significant yield response to N application rates within ±20% of the CM-based recommendations, indicates that growers can expect lettuce N uptake to fall within the range of 108–125 kg N ha

−1 under similar soil and environmental conditions. This range provides a practical reference for adjusting N applications in drip-irrigated lettuce on 1 m and 2 m bed widths. The observed N uptake is broadly consistent with previous findings in drip-irrigated lettuce in the Salinas Valley [

24] and falls at the lower end of the 100–150 kg N ha

−1 range suggested by [

17,

18], while remaining substantially below the 220 kg N ha

−1 reported by [

19]. Although one cited study reported no yield increase above 78 kg N ha

−1 [

40], those findings were based on different environmental and management conditions than those in our study (e.g., soil N status, climate, and soil types). In our experimental setting, the lowest rate of 87 kg N ha

−1 (CM recommendation) reflected the minimum N input required to avoid early-season N deficiency and remain consistent with locally recommended agronomic practices. Therefore, the N rates tested represent a realistic and practical range for lettuce production under our site-specific conditions rather than excessively high applications.

The observed increase in plant N uptake without a corresponding enhancement in yield indicates the occurrence of luxury N consumption, in which plants absorb N in excess of their metabolic or productive requirements. This finding is consistent with previous reports showing that lettuce is particularly prone to luxury N uptake under high fertilizer rates, where additional N does not translate into proportional biomass gains [

20,

49]. In line with this, NUE decreased significantly at higher N application rates, demonstrating that surplus N inputs were not efficiently converted into yield. Although leaf N concentrations increased under luxury N uptake, they remained below 4% of dry matter, within typical ranges for lettuce, suggesting that post-harvest quality and food safety were unlikely to be compromised. These results emphasize that excessive N fertilization can reduce NUE and increase the risk of environmental N losses without providing additional agronomic or quality benefits.

The lack of a yield response to N and irrigation treatments may be partly explained by the high initial soil nitrate levels measured at planting. The trial fields had been planted to sudangrass cover crops prior to lettuce, and mineralization of the cover crop residues likely supplied substantial plant-available N early in the season. This reduced the crop’s dependence on applied fertilizer across treatments. Additionally, the use of drip irrigation minimized plant water stress, thereby limiting the potential for irrigation-induced differences in yield. As noted earlier, lettuce can exhibit “luxury consumption”, whereby plants absorb N in excess of physiological demand without a corresponding increase in biomass or marketable yield. Although such uptake may buffer crops against short-term N deficits, it also lowers NUE and can elevate post-harvest soil nitrate, increasing the risk of leaching during subsequent irrigations or salt-leaching events. To reduce residual soil nitrate and improve soil health, sudangrass cover crops were planted after lettuce harvest as part of the cropping system. Sudangrass is effective at scavenging remaining soil nitrate and adding organic biomass, which helps reduce leaching potential and enhance soil quality. Collectively, these factors likely contributed to the limited yield response observed in this study.

Predominant soil types in desert lettuce production systems generally range from silty loam to silty clay loam, which are well-suited for implementing 2 m wide beds equipped with three driplines. In this study, WUE was consistently higher in the 2 m wide bed configurations, characterized by high-density planting, compared with the 1 m wide beds with lower plant density (

Table 5). This finding suggests that adopting 2 m wide beds may represent a viable strategy for desert farmers to simultaneously enhance lettuce yield and water productivity under suitable soil conditions. However, the broader adoption of wider beds may be limited in areas with fine sandy soils, where soil structure and infiltration characteristics could reduce their effectiveness. It is important to recognize that the management of sandy soils is inherently region-specific. Climatic factors, soil physicochemical properties, and locally adapted cropping systems collectively determine which management approaches are most suitable and effective.

Wider beds allow for a higher plant density per unit area, which can improve light interception and overall resource use efficiency, ultimately contributing to greater biomass accumulation and higher marketable yields. These results are consistent with previous studies [

50,

51] and emphasize the importance of optimizing bed width to achieve an ideal plant population that maximizes lettuce productivity while maintaining adequate water, nutrient, and space availability. Strategic management of bed width, therefore, represents a key approach to improving both crop performance and WUE in intensive desert lettuce production systems.

The findings highlight that optimal N fertilizer rates for lettuce are not fixed, but vary according to specific field conditions, including soil type, plant density relative to bed width, residual soil N from previous crops, and irrigation management under varying environmental settings. This variability underscores the importance of site-specific nutrient management strategies and reinforces the need to calibrate N recommendations using local agronomic data, crop uptake patterns, and real-time monitoring tools to avoid both over- and under-application of N fertilizer.

Integrated management of N and water is essential in lettuce production to enhance resource-use efficiency, enabling lower fertilizer application rates that support both profitability and environmental sustainability. Higher N rates may be required in over-irrigated fields, particularly where residual soil nitrate at planting is low or where soils are predominantly sandy and prone to leaching.

4.2. N Uptake During Early and Rapid Accumulation Phases

The N uptake values observed in the 2 m (109–155 kg N ha

−1) and 1 m (99–141 kg N ha

−1) bed trials (

Table 4) extended beyond the range previously reported for lettuce crops (121–136 kg N ha

−1) [

43], with values falling both below and above this reference range. This broader variability in N uptake may be attributed to differences in bed configuration, soil characteristics, irrigation and N practices, and the specific environmental conditions of the desert region. The average seasonal N uptake for romaine and iceberg lettuce across all trials (including both 2 m and 1 m bed widths) was 131 kg N ha

−1, exceeding the average uptake of 118 kg N ha

−1 reported for drip-irrigated lettuce in trials conducted on California’s Central Coast [

24]. This difference may be partially explained by climatic differences between the two regions, particularly the contrast between the arid desert environment and the more temperate coastal climate.

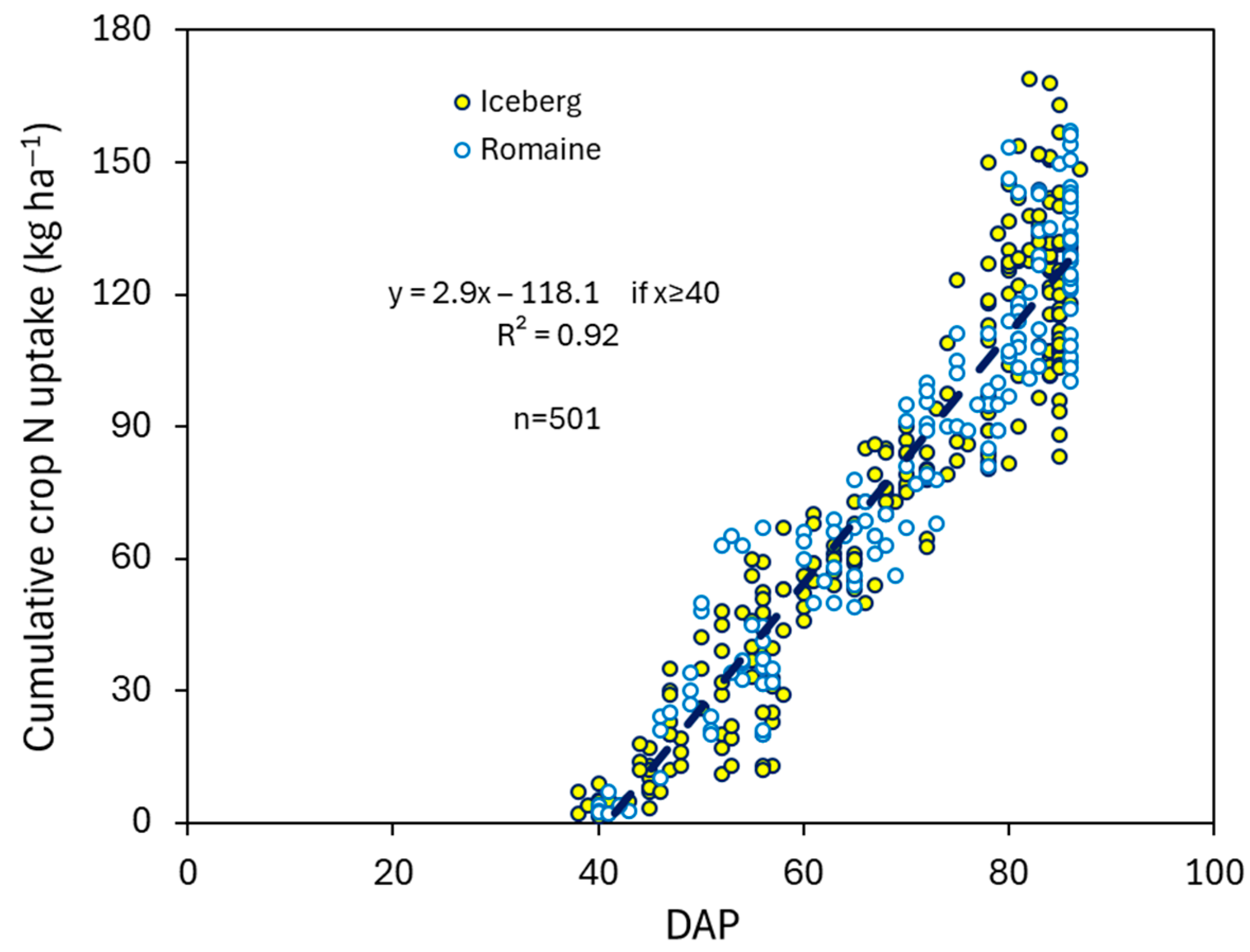

Crop N uptake exhibited a distinct two-phase pattern over the growing season (

Figure 5). During the early growth period (0–39 days after planting), cumulative N uptake reached approximately 10 kg, corresponding to an average daily uptake of 0.26 kg N d

−1. This relatively low rate reflects limited canopy and root development, slow biomass accumulation, and modest N demand during crop establishment. The gradual increase in N uptake during this phase is consistent with the progressive development of the root system and the initial expansion of leaf area, which together drive incremental nutrient acquisition.

Following early establishment, the crop entered a rapid N accumulation phase, during which cumulative N uptake increased sharply (≥40 days after planting) and was well described by the linear relationship:

where

y is cumulative N uptake (kg ha

−1) and

x is days after planting. The slope of 2.9 kg N ha

−1 d

−1 represents the average daily N uptake during this phase, which is more than tenfold higher than during the early growth period. The negative intercept (–118.1 kg ha

−1) is a mathematical artifact of the regression and indicates that the linear model is applicable only after the onset of accelerated growth. The near-linear cumulative uptake reflects a period of stable, high daily nitrogen demand, consistent with rapid vegetative growth, canopy expansion, and increased biomass accumulation, which together drive greater nutrient uptake up to harvest.

It should be noted that regional observations indicate that the lettuce growing season in commercial fields can occasionally extend beyond 90 days, although the typical crop duration for mid- and late-season plantings is 12 to 13 weeks. This extended duration underscores the relevance of characterizing N uptake patterns not only during early and rapid accumulation phases but also throughout the full production period up to harvest. Overall, these observations reveal a two-phase nitrogen uptake pattern: a prolonged period of slow, gradually increasing uptake during early establishment, followed by a period of high, relatively constant daily N accumulation during the rapid N accumulation phase. By combining cumulative uptake measurements with phase-specific average daily rates, this analysis provides a robust and biologically meaningful characterization of crop N dynamics, offering valuable insights for optimizing fertilizer management and supporting accurate crop growth modeling.

The linear pattern of lettuce crop N uptake observed in this study aligns with findings of previous studies [

22,

24], indicating a stable uptake rate during vegetative growth. A post-thinning N uptake rate of 4.0 kg N ha

−1 d

−1 has been reported for romaine and iceberg lettuce under drip irrigation in the Salinas Valley [

23], exceeding the average rate observed in this study. This difference could primarily be driven by climatic conditions and the duration of the crop season. Lettuce is grown in a mild winter climate with a longer crop season in the desert region, compared to the shorter spring–summer season in coastal production systems.

4.3. Prospects of CropManage in Commercial Desert Agricultural Operations

While the controlled research plots provided critical insights into the agronomic and resource-use efficiency outcomes of CropManage, understanding its broader applicability requires consideration of commercial production contexts. Supplementary observations from collaborating farmers in drip-irrigated desert systems were therefore used to evaluate the potential benefits of CM under large-scale operational conditions. These findings of this study are consistent with multi-year trials conducted in the Salinas Valley, which similarly reported that both N and irrigation inputs can be substantially reduced by following CM recommendations [

36,

37].

This analysis highlights substantial variability, as well as potential over-irrigation and over-fertilization, in commercial lettuce fields, indicating that operational efficiency in drip-irrigated desert lettuce production can be improved. It underscores the need for targeted extension efforts and the adoption of decision-support tools such as CM to guide farmers toward more efficient water and N use, ultimately enhancing sustainability, resource conservation, and crop productivity. Overall, this assessment provides insight into how decision-support tools like CM can be integrated into commercial production systems to improve input efficiency, reduce environmental impacts, and promote sustainable practices in arid environments.

Seasonal N application rates were lower in the trial fields than in the commercial sites (both farmer practice and CM), and several factors help explain this difference. The trial fields were planted to sudangrass cover crops prior to lettuce, and mineralization of the residues provided substantial plant-available N at planting. Consequently, the crop required less supplemental fertilizer N during the season. In contrast, the commercial sites did not include cover crops in their rotations and therefore began the season with lower baseline soil nitrate levels. Commercial growers also typically conduct more intensive pre-season salt-leaching irrigation, which can move nitrate below the root zone and further reduce initial soil N availability. Soil texture differences further contributed to the observed discrepancy; several commercial fields consisted of sandy loam or loamy fine sand, which have lower nutrient retention and greater nitrate-leaching potential, whereas the trial fields were located on heavier-textured soils that retain water and nutrients more effectively. Additionally, farmers in commercial systems often target higher marketable yields than those achieved in experimental trials, and higher yield expectations increase the N recommended by CM as well as the N applied under standard grower practices. Variability in planting dates, harvest dates, and overall season length among commercial fields also influenced crop N demand and contributed to higher seasonal N applications. Collectively, these factors explain why total N application rates were higher in the commercial fields than in the trial fields.

These differences between trial and commercial production systems also influence how decision-support tools such as CM are adopted and used. Although results from the commercial sites demonstrate that CM can reduce water and N inputs without compromising yield, several practical considerations affect its broader adoption. Effective use of CM requires accurate information on soil type, irrigation system performance, and planting schedules, which may limit adoption in fields where such data are not routinely collected. Successful implementation also depends on farmers’ familiarity with digital decision-support tools and their willingness to incorporate CM recommendations into existing practices. Training and technical support are therefore essential to ensure correct use and to build confidence in the system’s recommendations. Despite these challenges, CM has already been adopted by many large-scale vegetable operations in the Central Coast of California, indicating that the platform can meet commercial-scale needs when adequate support, field-specific calibration, and reliable field data are available. Together, these factors highlight both the potential and the practical requirements for broader CM adoption in desert lettuce production systems.