In Situ Diversity of Native Cherimoya in Southern Ecuador: Phenotypic and Ecological Insights

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Location and Plant Material

2.2. Characterization of Quantitative and Qualitative Traits

2.3. Ecogeographic Characterization

2.4. Phenotypic Characterization

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Description of Characteristics

3.2. Correlation Between Traits

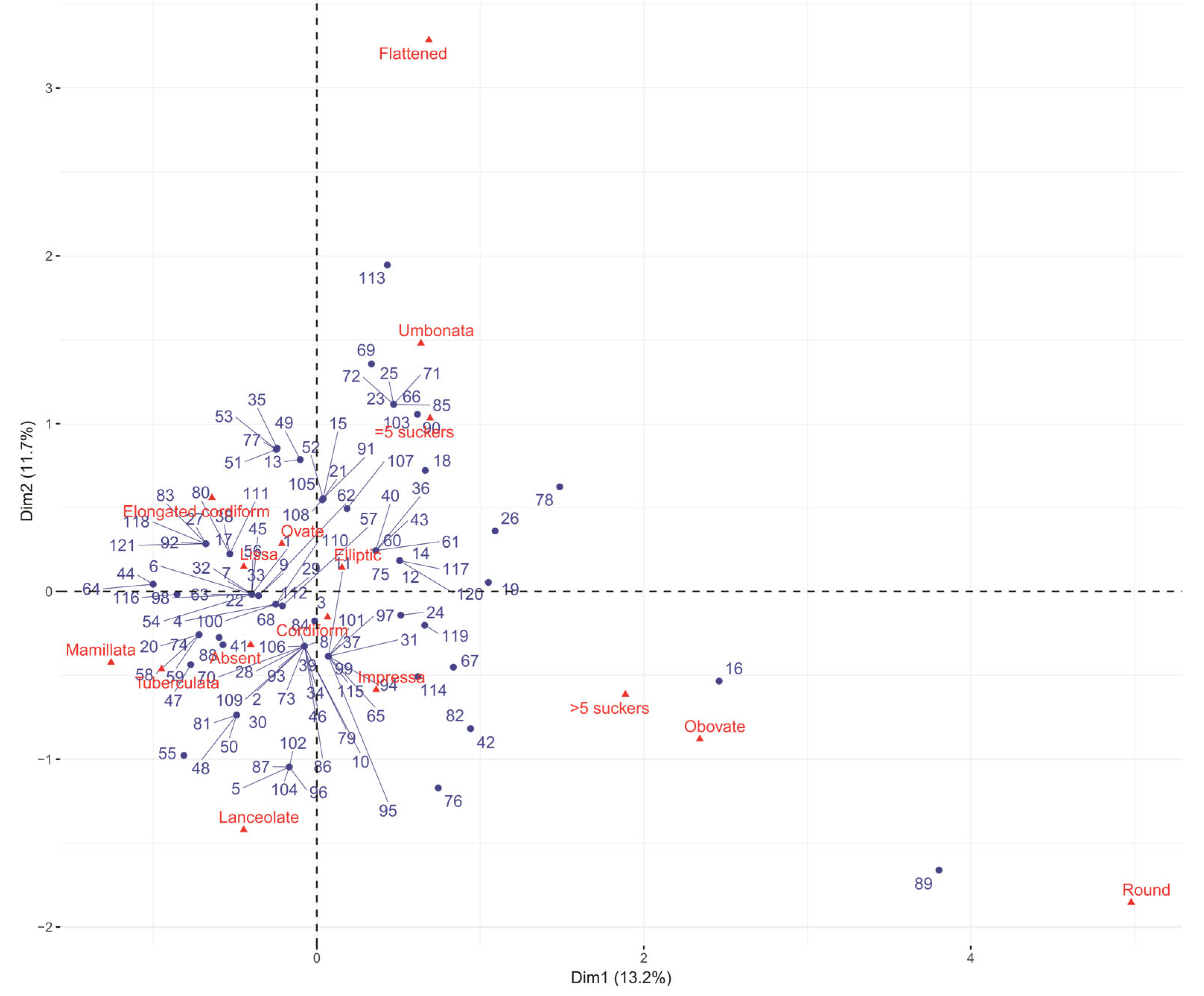

3.3. Multivariate Analysis

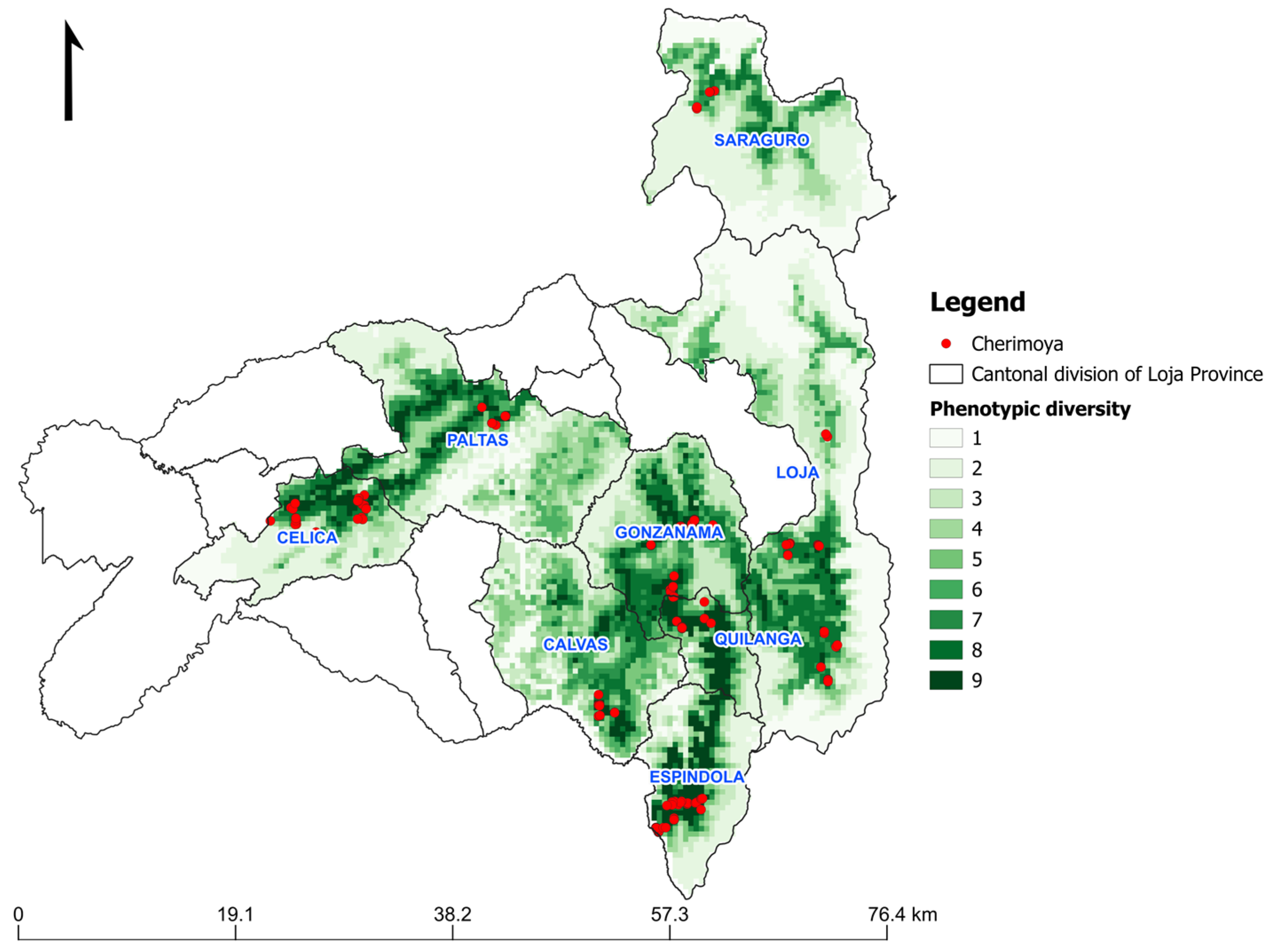

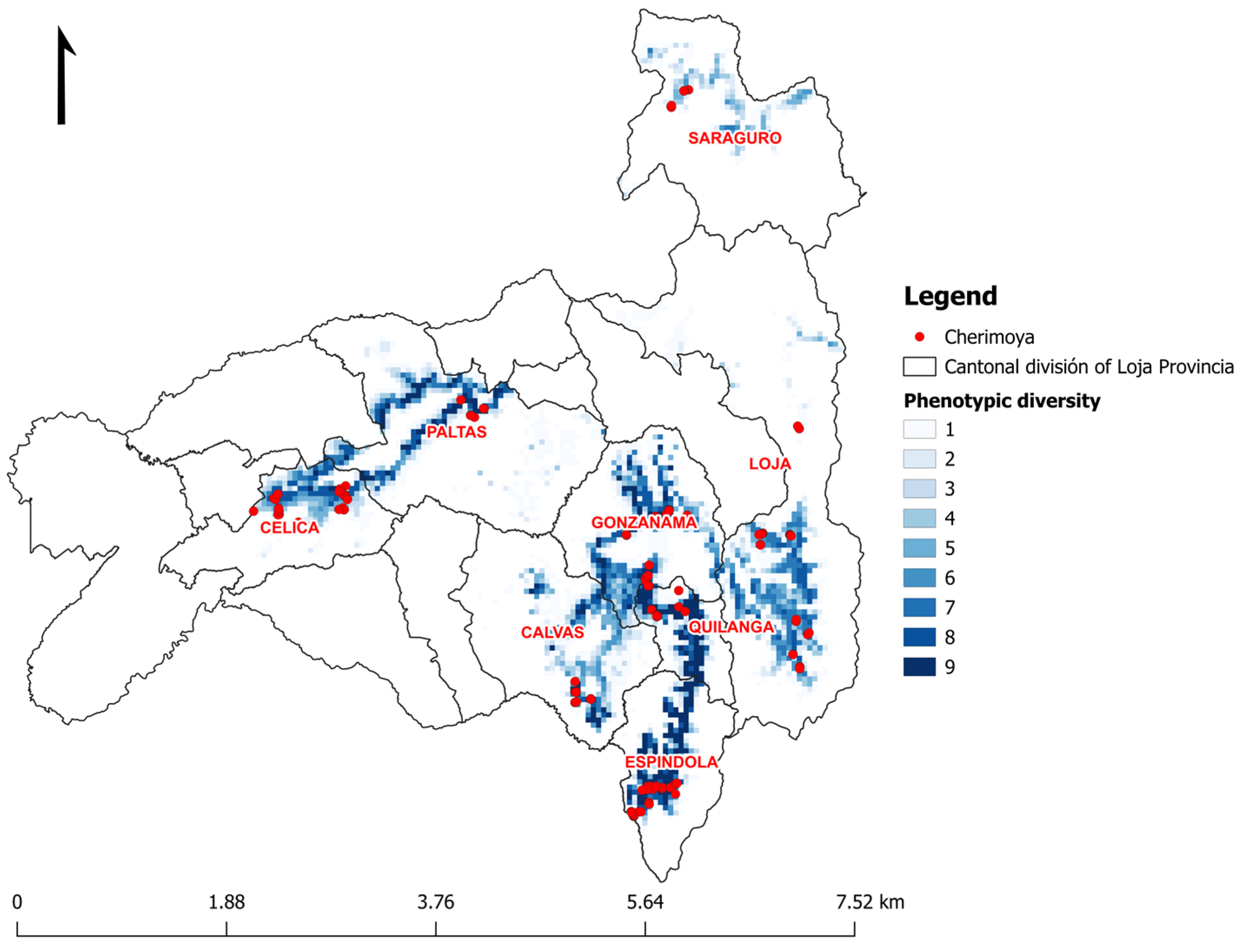

3.4. Ecogeographic and Phenotypic Diversity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Martin, C.; Viruel, M.A.; Lora, J.; Hormaza, J.I. Polyploidy in Fruit Tree Crops of the Genus Annona (Annonaceae). Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, U.C.; Kening, W.; Liang, S. Micronutrients in Soils, Crops, and Livestock. Earth Sci. Front. 2008, 15, 110–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larranaga, N.; Albertazzi, F.J.; Fontecha, G.; Palmieri, M.; Rainer, H.; van Zonneveld, M.; Hormaza, J.I. A Mesoamerican Origin of Cherimoya (Annona cherimola Mill.): Implications for the Conservation of Plant Genetic Resources. Mol. Ecol. 2017, 26, 4116–4130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, C.; Mannino, G.; Palazzolo, E.; Gianguzzi, G.; Perrone, A.; Serio, G.; Farina, V. Pomological, Sensorial, Nutritional and Nutraceutical Profile of Seven Cultivars of Cherimoya (Annona cherimola Mill). Foods 2020, 10, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheldeman, X. Distribution and Potential of Cherimoya (Annona cherimola Mill.) and Highland Papayas (Vasconcellea spp.) in Ecuador. Ph.D. Thesis, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Perrone, A.; Yousefi, S.; Salami, A.; Papini, A.; Martinelli, F. Botanical, Genetic, Phytochemical and Pharmaceutical Aspects of Annona cherimola Mill. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 296, 110896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larranaga, N.; van Zonneveld, M.; Hormaza, J.I. Holocene Land and Sea-trade Routes Explain Complex Patterns of pre-Columbian Crop Dispersion. New Phytol. 2021, 229, 1768–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larranaga, N.; Albertazzi, F.J.; Hormaza, J.I. Phylogenetics of Annona cherimola (Annonaceae) and Some of Its Closest Relatives. J. Syst. Evol. 2019, 57, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Damme, P.; Van Damme, V.; Scheldeman, X. Ecology and Cropping of Cherimoya (Annona cherimola Mill.) in Latin America. New Data from Ecuador. Fruits 2000, 55, 195–206. [Google Scholar]

- van Zonneveld, M.; Scheldeman, X.; Escribano, P.; Viruel, M.A.; Van Damme, P.; Garcia, W.; Hormaza, J.I. Mapping Genetic Diversity of Cherimoya (Annona cherimola Mill.): Application of Spatial Analysis for Conservation and Use of Plant Genetic Resources. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e29845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veasey, E.A.; Costa, F.M.; do Nascimento, W.F.; Ramos, S.L.F.; Clement, C.R. What Can We Say About Plant Domestication in the Neotropics? In Population Genetics in the Neotropics; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 317–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larranaga, N.; Agustín, J.A.; Albertazzi, F.; Fontecha, G.; Vásquez-Castillo, W.; Cautín, R.; Quiroz, E.; Ragonezi, C.; Hormaza, J.I. Underutilized Fruit Crops at a Crossroads: The Case of Annona cherimola—From Pre-Columbian to Present Times. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, M. Chirimoya (Annona cherimola Miller), Frutal Tropical y Sub-Tropical de Valores Promisorios. Cultiv. Trop. 2013, 34, 52–63. [Google Scholar]

- Scheldeman, X.; Van Damme, P.; Motoche, J.R.; Alvarez, J.U. Germplasm Collection and Fruit Characterisation of Cherimoya (Annona cherimola) in Loja Province, Ecuador, an Important Centre of Biodiversity. Belg. J. Bot. 2006, 139, 27–38. [Google Scholar]

- Bachman, S.P.; Brown, M.J.; Leão, T.C.; Nic Lughadha, E.; Walker, B.E. Extinction Risk Predictions for the World’s Flowering Plants to Support Their Conservation. New Phytol. 2024, 242, 797–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campuzano, L.; Angel, N.T.; Burkart, S. Cattle Ranching in Colombia: A Monolithic Industry? Hist. Ambient. Latinoam. Caribeña HALAC Rev. Solcha 2022, 12, 81–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curatola Fernández, G.F.; Obermeier, W.A.; Gerique, A.; Lopez Sandoval, M.F.; Lehnert, L.W.; Thies, B.; Bendix, J. Land Cover Change in the Andes of Southern Ecuador—Patterns and Drivers. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 2509–2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia-Armijos, M.F.; Homeier, J.; Munt, D.D. Spatio-Temporal Analysis of the Human Footprint in South Ecuador: Influence of Human Pressure on Ecosystems and Effectiveness of Protected Areas. Appl. Geogr. 2017, 78, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteros-Altamirano, Á.; Tapia, C.; Paredes, N.; Alulema, V.; Tacán, M.; Roura, A.; Lima, L.; Sørensen, M. Morphological and Ecogeographic Study of the Diversity of Cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) in Ecuador. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra Quijano, M.; Iriondo, J.M.; Torres, M.E.; López, F.; Phillips, J.; Kell, S. Capfitogen 3: Una Caja de Herramientas Para la Conservación y Promoción del Uso de La Biodiversidad Agrícola; Ministerio de Ciencia Tecnología e Innovación: Bogotá, Colombia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Biodiversity International; CHERLA. Descriptores Para Chirimoyo (Annona cherimola Mill.); Bioversity International: Rome, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Tourn, G.M.; Barthélémy, D.; Grosfeld, J. Una Aproximación a La Arquitectura Vegetal: Conceptos, Objetivos y Metodología. Bol. Soc. Argent. Botánica 1999, 34, 85–99. [Google Scholar]

- Castel, T.; Beaudoin, A.; Barczi, J.; Caraglio, Y.; Floury, N.; Le Toan, T.; Castagnas, L. On the Coupling of Backscatter Models with Tree Growth Models. 1. A Realistic Description of the Canopy Using the AMAP Tree Growth Model. In Proceedings of the IGARSS’97, 1997 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium Proceedings. Remote Sensing—A Scientific Vision for Sustainable Development, Singapore, 3–8 August 1997; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 1997; Volume 2, pp. 784–786. [Google Scholar]

- Posit team. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R. 2025. Available online: http://www.posit.co/ (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Thuiller, W.; Georges, D.; Engler, R.; Breiner, F. Biomod2: Ensemble Platform for Species Distribution Modeling. R Package Version 2016, 3, r539. [Google Scholar]

- Brun, P.; Zimmermann, N.E.; Hari, C.; Pellissier, L.; Karger, D.N. Global Climate-Related Predictors at Kilometer Resolution for the Past and Future. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2022, 14, 5573–5603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karger, D.N.; Schmatz, D.R.; Dettling, G.; Zimmermann, N.E. High-Resolution Monthly Precipitation and Temperature Time Series from 2006 to 2100. Sci. Data 2020, 7, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karger, D.N.; Wilson, A.M.; Mahony, C.; Zimmermann, N.E.; Jetz, W. Global Daily 1 Km Land Surface Precipitation Based on Cloud Cover-Informed Downscaling. Sci. Data 2021, 8, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karger, D.N.; Lange, S.; Hari, C.; Reyer, C.P.; Conrad, O.; Zimmermann, N.E.; Frieler, K. CHELSA-W5E5: Daily 1 Km Meteorological Forcing Data for Climate Impact Studies. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2023, 15, 2445–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bougeard, S.; Dray, S. Supervised Multiblock Analysis in R with the Ade4 Package. J. Stat. Softw. 2018, 86, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chessel, D.; Dufour, A.B.; Thioulouse, J. The Ade4 Package-I-One-Table Methods. R News 2004, 4, 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- Dray, S.; Dufour, A.B.; Chessel, D. The Ade4 Package-II: Two-Table and K-Table Methods. R News 2007, 7, 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Dray, S.; Dufour, A.-B. The Ade4 Package: Implementing the Duality Diagram for Ecologists. J. Stat. Softw. 2007, 22, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thioulouse, J.; Dray, S.; Dufour, A.-B.; Siberchicot, A.; Jombart, T.; Pavoine, S. Multivariate Analysis of Ecological Data with Ade4; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- ESRI. ArcMap 10.8; Environmental Systems Research Institute: Redlands, CA, USA, 2020; Available online: https://desktop.arcgis.com/ (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Qgis Association. QGIS Geographic Information System; Qgis Association: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H.; Hester, J.; Francois, R. Readr: Read Rectangular Text Data; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H. Dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation, R Package Version 04; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2015; Volume 3, p. 156.

- Ooms, J.; McNamara, J. Writexl: Export Data Frames to Excel’xlsx’format, Version 1.4. 2; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2023.

- Wei, T.; Simko, V.; Levy, M.; Xie, Y.; Jin, Y.; Zemla, J. Package “Corrplot”: Visualization of a Correlation Matrix; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kassambara, A.; Mundt, F. Factoextra: Extract and Visualize the Results of Multivariate Data Analyses; CRAN: Contributed Packages; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H.; Bryan, J. Readxl: Read Excel Files, R Package Version 1.4.5; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2019; Volume 1, p. 785.

- Maechler, M. Cluster: Cluster Analysis Basics and Extensions, R Package Version 20 7–1; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2018.

- Lê, S.; Josse, J.; Husson, F. FactoMineR: An R Package for Multivariate Analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 2008, 25, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perfectti, F.; Pascual, L. Genetic Diversity in a Worldwide Collection of Cherimoya Cultivars. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2005, 52, 959–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donhouedé, J.C.F.; Marques, I.; Salako, K.V.; Assogbadjo, A.E.; Ribeiro, N.; Ribeiro-Barros, A.I. Genetic and Morphological Diversity in Populations of Annona Senegalensis Pers. Occurring in Western (Benin) and Southern (Mozambique) Africa. PeerJ 2023, 11, e15767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nwosisi, S.; Dhakal, K.; Nandwani, D.; Raji, J.I.; Krishnan, S.; Beovides-García, Y. Genetic Diversity in Vegetable and Fruit Crops. In Genetic Diversity in Horticultural Plants; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 87–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Pelaez, J.C.; Saravia-Navarro, D.; Cruz-Delgado, J.H.; del Carpio-Salas, M.A.; Barboza, E.; Casanova Nuñez Melgar, D.P. Phenotypic Diversity of Morphological Traits of Pitahaya (Hylocereus spp.) and Its Agronomic Potential in the Amazonas Region, Peru. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourão Filho, F.d.A.A.; Espinoza-Núñez, E.; Stuchi, E.S.; Ortega, E.M.M. Plant Growth, Yield, and Fruit Quality of ‘Fallglo’and ‘Sunburst’Mandarins on Four Rootstocks. Sci. Hortic. 2007, 114, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penzel, M.; Kröling, C. Thinning Efficacy of Metamitron on Young’RoHo 3615’(Evelina®) Apple. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 272, 109586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrés-Agustín, J.; González-Andrés, F.; Nieto-Ángel, R.; Barrientos-Priego, A. Morphometry of the Organs of Cherimoya (Annona cherimola Mill.) and Analysis of Fruit Parameters for the Characterization of Cultivars, and Mexican Germplasm Selections. Sci. Hortic. 2006, 107, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prudent, M.; Dai, Z.W.; Génard, M.; Bertin, N.; Causse, M.; Vivin, P. Resource Competition Modulates the Seed Number–Fruit Size Relationship in a Genotype-Dependent Manner: A Modeling Approach in Grape and Tomato. Ecol. Model. 2014, 290, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Carmona, M.; Márquez-San Emeterio, L.; Reyes-Martín, M.; Ortiz-Bernad, I.; Sierra, M.; Fernández-Ondoño, E. Changes in Nutrient Contents in Peel, Pulp, and Seed of Cherimoya (Annona cherimola Mill.) in Relation to Organic Mulching on the Andalusian Tropical Coast (Spain). Sci. Hortic. 2020, 263, 109120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raes, L.; D’Haese, M.; Aguirre, N.; Knoke, T. A Portfolio Analysis of Incentive Programmes for Conservation, Restoration and Timber Plantations in Southern Ecuador. Land Use Policy 2016, 51, 244–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassa, A.; Alcaraz, L.; Larranaga, N.; De Meyer, E.; Hormaza, I.; de la Peña, E. Evaluation of Genetic Diversity of Ethiopian Mango Genotypes and Comparison with a Worldwide Germplasm Collection. Sci. Hortic. 2025, 348, 114211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lora, J.; Larranaga, N.; Hormaza, J.I. Genetics and Breeding of Fruit Crops in the Annonaceae Family: Annona spp. and Asimina app. Adv. Plant Breed. Strateg. Fruits 2018, 3, 651–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdemir, D.; Beavis, W.; Fritsche-Neto, R.; Singh, A.K.; Isidro-Sánchez, J. Multi-Objective Optimized Genomic Breeding Strategies for Sustainable Food Improvement. Heredity 2019, 122, 672–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurens, F.; Aranzana, M.J.; Arus, P.; Bassi, D.; Bink, M.; Bonany, J.; Caprera, A.; Corelli-Grappadelli, L.; Costes, E.; Durel, C.-E. An Integrated Approach for Increasing Breeding Efficiency in Apple and Peach in Europe. Hortic. Res. 2018, 5, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behán, T.; Kovács, S.; Tóth, E.G.; György, Z. Genetic Diversity of Cornelian Cherry (Cornus Mas L.) Cultivars from Eastern Europe Based on SSR Markers. Sci. Hortic. 2025, 349, 114232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Hayat, F.; Lei, Z.; Ruan, H.; Lin, W.; Tu, P.; Li, C.; Song, W.; Li, Y.; Li, J. Genetic Diversity Analysis of Pomelo Germplasm Resources Based on Leaf Phenotype and SCoT Markers. Sci. Hortic. 2025, 346, 114174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Ram, C.; Meena, R.; Yadav, L.P.; Kaldappa, G.; Gora, J.S.; Berwal, M.K.; Rane, J. Morpho-Biochemical Characterization and Molecular Diversity Analysis of Bael [Aegle Marmelos (L.) Correa.] Germplasm Using Gene-Targeted Molecular Markers. Sci. Hortic. 2025, 339, 113900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Traits | Min 1 | Max 2 | Mean | SD 3 | CV 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tree | |||||

| Crown diameter | 2.08 | 22.90 | 7.66 | 2.66 | 34.69 |

| Tree height | 1.90 | 13.18 | 7.03 | 1.80 | 25.61 |

| Trunk cross-sectional area | 0.00 | 8930.59 | 1182.98 | 1428.41 | 120.75 |

| Main trunk height | 1.00 | 1700.00 | 93.17 | 136.05 | 146.02 |

| Branch length | 5.67 | 72.78 | 18.51 | 10.93 | 59.07 |

| Number of leaves per branch | 3.33 | 39.00 | 8.78 | 4.97 | 56.54 |

| Number of nodes per meter of branch | 15.00 | 69.00 | 38.08 | 9.76 | 25.63 |

| Number of flowers per meter on the branch of the previous year | 1.00 | 63.00 | 13.49 | 10.84 | 80.32 |

| Leaves | |||||

| Leaf length | 30.60 | 177.90 | 122.03 | 18.44 | 15.11 |

| Leaf width | 43.81 | 113.92 | 76.53 | 12.97 | 16.95 |

| Leaf thickness | 0.02 | 1.94 | 0.24 | 0.13 | 53.03 |

| Petiole length | 5.75 | 26.43 | 1.22 | 2.35 | 19.26 |

| Petiole thickness | 0.23 | 4.10 | 2.30 | 0.45 | 19.34 |

| Number of primary veins in the leaf blade | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Fruit and seeds | |||||

| Fruit length | 45.00 | 147.00 | 91.84 | 18.60 | 20.25 |

| Fruit diameter | 48.85 | 204.73 | 91.25 | 18.30 | 20.05 |

| Fruit weight | 61.96 | 1266.66 | 418.02 | 201.26 | 48.15 |

| Exocarp thickness | 0.40 | 4.60 | 1.66 | 0.71 | 42.92 |

| Exocarp weight | 11.95 | 445.57 | 114.09 | 52.16 | 45.72 |

| Pulp weight | 33.90 | 786.44 | 275.60 | 152.49 | 55.33 |

| Total weight seeds per fruit | 3.18 | 83.19 | 31.08 | 15.54 | 50.00 |

| Number of seeds | 6.00 | 98.00 | 44.09 | 17.66 | 40.05 |

| Pulp-to-seed ratio | 2.53 | 96.81 | 20.28 | 13.02 | 64.23 |

| Resistance to penetration | 0.85 | 83.75 | 22.18 | 10.08 | 45.45 |

| Soluble solids | 7.10 | 35.70 | 21.81 | 3.94 | 18.07 |

| Titratable acidity | 0.06 | 0.74 | 0.36 | 0.11 | 29.43 |

| Soluble solids/titratable acidity ratio | 25.22 | 427.00 | 65.97 | 31.32 | 47.48 |

| Fresh seed weight | 0.28 | 1.77 | 0.70 | 0.19 | 26.48 |

| Seed length | 11.94 | 23.50 | 17.51 | 1.86 | 10.61 |

| Seed width | 7.38 | 12.52 | 9.98 | 0.92 | 9.22 |

| Inflorescence | |||||

| Flower weight | 0.46 | 9.95 | 1.33 | 1.11 | 83.74 |

| Petal length | 16.78 | 42.38 | 27.51 | 4.63 | 16.81 |

| Petal width | 4.52 | 10.70 | 6.95 | 1.17 | 16.79 |

| Petal weight | 0.05 | 18.76 | 1.26 | 1.73 | 137.57 |

| Flower peduncle length | 3.43 | 19.80 | 10.25 | 2.69 | 26.26 |

| Weight of the stigmatic cone | 0.03 | 0.79 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 116.67 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vásquez, S.C.; Erazo-Hurtado, S.; Capa-Morocho, M.; Granja, F.; Molina-Müller, M.; Viteri, L.O.; Romero, M.A.; Chamba-Zaragocin, D. In Situ Diversity of Native Cherimoya in Southern Ecuador: Phenotypic and Ecological Insights. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1505. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121505

Vásquez SC, Erazo-Hurtado S, Capa-Morocho M, Granja F, Molina-Müller M, Viteri LO, Romero MA, Chamba-Zaragocin D. In Situ Diversity of Native Cherimoya in Southern Ecuador: Phenotypic and Ecological Insights. Horticulturae. 2025; 11(12):1505. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121505

Chicago/Turabian StyleVásquez, Santiago C., Santiago Erazo-Hurtado, Mirian Capa-Morocho, Fernando Granja, Marlene Molina-Müller, Luis O. Viteri, Melissa A. Romero, and Diego Chamba-Zaragocin. 2025. "In Situ Diversity of Native Cherimoya in Southern Ecuador: Phenotypic and Ecological Insights" Horticulturae 11, no. 12: 1505. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121505

APA StyleVásquez, S. C., Erazo-Hurtado, S., Capa-Morocho, M., Granja, F., Molina-Müller, M., Viteri, L. O., Romero, M. A., & Chamba-Zaragocin, D. (2025). In Situ Diversity of Native Cherimoya in Southern Ecuador: Phenotypic and Ecological Insights. Horticulturae, 11(12), 1505. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121505