Abstract

Yeast-derived biomolecules are redefining the boundaries of green nanotechnology. Biosurfactants, exopolysaccharides, enzymes, pigments, proteins, and organic acids—when sourced from carbohydrate-rich lignocellulosic hydrolysates—offer a molecular toolbox capable of directing, stabilizing, and functionalizing nanoparticles (NPs) with unprecedented precision. Beyond their structural diversity and intrinsic biocompatibility, these biomolecules anchor a paradigm shift: the convergence of biorefineries with nanotechnology to deliver multifunctional materials for the circular bioeconomy. This review explores: (i) the expanding portfolio of metallic and metal oxide NPs synthesized through yeast biomolecules; (ii) molecular-level mechanisms of reduction, capping, and surface tailoring that dictate NP morphology, stability, and reactivity; (iii) synergistic roles in intensifying lignocellulosic processes—from enhanced hydrolysis to catalytic upgrading; and (iv) frontier applications spanning antimicrobial coatings, regenerative packaging, precision agriculture, and environmental remediation. We highlight structure–function relationships, where amphiphilicity, charge distribution, and redox activity govern resilience under saline, acidic, and thermally harsh industrial matrices. Yet, critical bottlenecks remain: inconsistent yields, limited comparative studies, downstream recovery hurdles, and the absence of comprehensive life-cycle and toxicological evaluations. To bridge this gap, we propose a translational roadmap coupling standardized characterization with real hydrolysate testing, molecular libraries linking biomolecule chemistry to NP performance, and integrated techno-economic and environmental assessments. By aligning yeast biotechnology with nanoscience, we argue that yeast-biomolecule-driven nanoplatforms are not merely sustainable alternatives but transformative solutions for next-generation lignocellulosic biorefineries.

1. Introduction

Economic growth remains closely connected to rising energy demand, still dominated by fossil fuels, particularly in developing economies, which accelerates environmental degradation [1]. Fossil resources such as coal, oil, and natural gas account for more than 75% of global greenhouse gas emissions and nearly 90% of CO2 emissions. The petrochemical sector intensifies this burden as it consumes fossil inputs not only as energy but also as raw material [2]. In this scenario, the transition toward a bioeconomy is no longer optional, but a strategic imperative to reduce fossil dependence and mitigate its environmental consequences [3]. The bioeconomy is based on the replacement of fossil-derived inputs with renewable biological resources in energy and industrial production. Among renewables, biomass stands out as the only carbon source capable of substituting fossil feedstocks in the manufacture of fuels, chemicals, and advanced materials [4]. Within this framework, lignocellulosic biorefineries rise as central pillars, integrating biotechnological processes to transform abundant residues into fuels, chemicals, and value-added bioproducts [5].

Globally, around 1.3 billion tons of lignocellulosic biomass are generated every year, yet less than 3% is effectively converted into products with industrial relevance [6]. Unlocking even a fraction of this potential could displace millions of barrels of fossil oil annually or meet a significant portion of the global chemical feedstock demand. In tropical regions such as Brazil, sugarcane bagasse represents not only an abundant residue but a strategic driver of circularity, given the country’s leadership in sugarcane production [7]. Its efficient conversion, however, requires disruptive solutions that overcome the intrinsic recalcitrance of lignocellulose, combining advanced pretreatments, enzymatic hydrolysis, and robust microbial platforms in intensified and integrated systems.

In parallel, nanotechnology has positioned itself as a transformative field in energy, environmental, and biomedical applications. Nanoparticles (NPs) exhibit unique physicochemical properties such as high surface-to-volume ratio, tunable electronic states, catalytic performance, and antimicrobial activity, enabling functionalities unattainable with bulk materials. Silver nanoparticles are widely applied in antimicrobial coatings, gold nanoparticles in catalysis and biosensing, and zinc oxide nanoparticles in smart packaging and pollutant degradation. Yet, conventional synthesis routes still rely on toxic reagents and harsh conditions, raising serious concerns regarding environmental safety, scalability, and regulatory acceptance [8]. Green synthesis emerges as a paradigm shift, using renewable feedstocks and biological molecules as reducing and stabilizing agents, and aligning nanotechnology with the core principles of the circular bioeconomy.

Yeasts are at the frontier of this convergence. Beyond their established role in biorefineries, they naturally produce a diverse repertoire of biomolecules—including biosurfactants, exopolysaccharides, enzymes, pigments, and organic acids—that can direct nanoparticle formation under mild and eco-friendly conditions. These compounds not only reduce and stabilize nanoparticles but also impart functional traits such as amphiphilicity, redox activity, and charge modulation, which govern morphology, stability, and performance. Despite this disruptive potential, current research remains fragmented, scattered across biotechnology, microbiology, and nanoscience. Few reviews have systematically articulated the continuum linking lignocellulosic feedstocks, yeast-derived biomolecules, nanoparticle synthesis, and applications in biorefineries.

This review seeks to fill this critical gap. We consolidate recent advances on yeast-derived biomolecules as mediators of nanoparticle biosynthesis within lignocellulosic biorefineries, integrating knowledge on biomass pretreatment, microbial robustness, and nanoparticle functionalization. More than sustainable alternatives, yeast biomolecules are presented here as disruptive enablers capable of reshaping the interface between biorefineries and nanoscience, and driving a new generation of circular bioeconomy solutions.

This review is based on a structured literature review of the last 5 years, focusing on articles published in peer-reviewed journals indexed in Scopus and Web of Science. The search was conducted using a limited set of core terms related to lignocellulosic biorefineries, yeast-derived biomolecules, and green synthesis of nanoparticles, such as “lignocellulosic biorefinery”, “yeast biosurfactant”, “yeast-derived biomolecules”, “green synthesis”, and “nanoparticles”, combined with Boolean operators (AND/OR) when appropriate. Only full-length articles and review papers written in English and aligned with the scope of this work were included, i.e., studies addressing (i) lignocellulosic biomass valorization in biorefinery contexts and/or (ii) the production and application of yeast-derived biomolecules in the synthesis or stabilization of nanomaterials. Conference abstracts, theses, patents, book chapters, non-indexed sources, and studies dealing exclusively with chemically synthesized nanoparticles without biological mediators were excluded. Additional relevant references were identified by screening the reference lists of the selected articles.

2. Lignocellulosic Biomass as Strategic Feedstock

Harnessing lignocellulosic biomass is not a matter of availability, but of overcoming its structural and chemical complexity. Despite more than 182 billion tons produced each year, less than 5% is effectively valorized, leaving behind an untapped reservoir of carbon-rich material that could redefine the future of energy, materials, and chemicals [9].

Its architecture—woven from cellulose (30–50%), hemicellulose (20–35%), and lignin (15–30%)—is at once its greatest strength and its primary bottleneck [10]. Cellulose offers crystalline microfibrils of β-(1→4)-linked glucose, the molecular backbone for bioethanol and biochemicals [11,12]. Hemicellulose, an amorphous heteropolymer of pentoses and hexoses, releases xylose, arabinose, and mannose, precursors for xylitol, furfural, and levulinic acid [13,14]. Lignin, long dismissed as waste, contains diverse aromatic building blocks that can be transformed into bio-aromatics, carbon fibers, and nanostructured materials. When integrated, these streams form the cornerstone of a true biorefinery concept, where no fraction is sidelined [15,16].

Yet this promise collides with recalcitrance. Lignin shields polysaccharides, hemicellulose cross-links cellulose, and crystalline regions resist enzymatic attack. Pretreatments partially overcome this barrier but generate inhibitory compounds—furfural, HMF, weak acids, phenolics, salts—that disrupt microbial physiology and redox balance [17,18,19]. Detoxification improves fermentability but demands additional energy and cost [20]. The bottleneck is not the existence of biomass, but the accessibility of its sugars and aromatics at scale.

To unlock this potential, the field must move beyond describing abundance and tackle the structural and metabolic constraints that keep lignocellulose underexploited. The challenge is not only to fractionate biomass, but to integrate pathways that valorize all its components into fuels, chemicals, and nanomaterials.

Table 1 summarizes the main pretreatment strategies applied to lignocellulosic biomass, the inhibitory compounds they generate, their impact on microbial performance, and the corresponding mitigation approaches in integrated biorefineries.

Table 1.

Pretreatment strategies for lignocellulosic biomass: generated inhibitors, microbial responses, and mitigation approaches in integrated biorefineries.

As shown in Table 1, conventional lignocellulosic pretreatments inevitably generate inhibitory cocktails that constrain microbial performance, making mitigation strategies and strain robustness central design criteria in integrated biorefineries. Beyond their inhibitory profiles, however, pretreatments also differ in their primary mode of action on biomass structure, which provides a useful basis for classifying them into physical, chemical, physicochemical and biological routes.

Pretreatment is therefore a cornerstone in overcoming the inherent recalcitrance of lignocellulosic biomass, as it improves the accessibility of structural polysaccharides to enzymatic hydrolysis and subsequent fermentation. Physical methods such as milling or steam explosion primarily enhance enzyme accessibility by reducing particle size, increasing surface area and disrupting crystallinity. Chemical treatments (acidic, alkaline, ionic liquids) target the solubilization of hemicellulose and lignin, while physicochemical techniques combine thermal or mechanical disruption with chemical action to maximize digestibility [17]. Biological pretreatments, although still limited by productivity and cost, harness the enzymatic repertoire of ligninolytic microorganisms to selectively degrade recalcitrant fractions under mild conditions [21].

Table 2 summarizes representative pretreatment categories, illustrating how different physical, chemical, physicochemical and biological routes modify lignocellulosic biomass and open specific opportunities for nanomaterial generation and nanotechnology applications in biorefineries.

Table 2.

Pretreatment categories of lignocellulosic biomass: representative examples, mechanistic outcomes, biorefinery relevance, and potential links to nanotechnology applications.

Together, these advances highlight that pretreatment cannot be regarded as an isolated operation, but rather as a strategic interface with microbial metabolism and downstream nano-enabled processes. Designing pretreatments that balance fractionation efficiency with reduced inhibitor formation is essential to minimize detoxification steps and accelerate process integration, while preserving the functionality of lignin- and cellulose-derived fractions for advanced materials. In parallel, valorization of these streams is greatly strengthened when coupled to robust yeast platforms, which are able to ferment under inhibitory conditions and producing biosurfactants, exopolysaccharides and other biomolecules capable of mediating nanoparticle synthesis and stabilization. This integrated vision—where pretreatment design, microbial resilience and nanobiotechnology are co-optimized—offers a rational framework for transforming lignocellulosic feedstocks into both biofuels and high-value nanomaterials, thereby enhancing the techno-economic and environmental feasibility of next-generation biorefineries.

3. Yeasts in Lignocellulosic Biorefineries

Yeasts are versatile eukaryotic microorganisms with long-standing applications in food, pharmaceuticals, and industrial biotechnology. Their strategic relevance in lignocellulosic biorefineries stems from key traits such as metabolic flexibility, tolerance to harsh environments (low pH, ethanol accumulation, and inhibitory compounds), and the Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) status attributed to several species, which facilitates safe implementation in industrial settings [19,34]. Unlike filamentous fungi, yeasts maintain a unicellular morphology that prevents excessive viscosity in high-cell-density fermentations, ensuring scalability and process stability.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae remains the cornerstone of industrial fermentation due to its robustness, genetic accessibility, and long history of safe use. However, its inability to natively ferment xylose—the second most abundant sugar in hemicellulosic hydrolysates—represents a significant bottleneck [35]. Even engineered S. cerevisiae strains display lower xylose conversion efficiencies compared to glucose. In contrast, non-conventional yeasts such as Scheffersomyces stipitis, Spathaspora passalidarum, and Scheffersomyces shehatae possess native xylose metabolic pathways and exhibit higher tolerance to inhibitors, positioning them as strategic candidates for lignocellulosic valorization [36]. Among them, Scheffersomyces shehatae is particularly relevant for its ability to maintain fermentation performance in partially detoxified hydrolysates, thereby reducing pretreatment demands and operational costs [37].

Beyond sugar metabolism, yeasts are increasingly recognized as adaptable biofactories for high-value metabolites. Strategies such as solid-state fermentation (SSF) and consolidated bioprocessing (CBP) have enabled yeast-driven transformation of agro-industrial residues into fuels, organic acids, enzymes, and biosurfactants [38,39]. Collectively, these attributes illustrate the dual importance of yeasts in lignocellulosic biorefineries: as robust fermentation platforms and as producers of metabolites that broaden the value chain beyond fuels.

In addition to their role as core fermentative platforms, yeasts provide a broad molecular repertoire of extracellular compounds that are increasingly exploited in green nanotechnology. This multifunctionality motivates a closer examination of yeast-derived biomolecules and their contributions to nanoparticle biosynthesis and stabilization in circular bioeconomy frameworks.

4. Yeast-Derived Biomolecules as Molecular Mediators of Nanoparticle Biosynthesis

Harnessing lignocellulosic biomass requires not only robust microbial platforms but also defined sets of biomolecules capable of driving reactions under eco-friendly conditions. Yeasts, beyond their established fermentative role, produce a diverse array of extracellular molecules, that act as reducing agents, ligands, and capping or stabilizing components during nanoparticle formation. Their structural diversity, amphiphilic character and redox-active functional groups enable the generation of nanomaterials with tailored properties. Rather than being mere by-products, these biomolecules operate as key molecular interfaces linking biorefinery streams with nanobiotechnology.

4.1. Biosurfactants

Yeast-derived biosurfactants, such as sophorolipids, mannosylerythritol lipids (MELs), and cellobiose lipids, are amphiphilic molecules with strong surface activity. They reduce surface and interfacial tension, stabilize emulsions, and enable hydrocarbon degradation [40,41]. In nanotechnology, these amphiphiles serve as dual-function agents, simultaneously reducing metal ions and stabilizing nanoparticles against aggregation. Sophorolipids produced by Starmerella bombicola have mediated the synthesis of silver and gold nanoparticles with antimicrobial activity [42], while MELs from Moesziomyces spp. have been employed as templates for gold nanostructures with catalytic potential [43,44]. Their biodegradability and low toxicity align with green chemistry principles, making them key biomolecules in sustainable nanomaterial design.

At a mechanistic level, yeast biosurfactants can influence nanoparticle formation in different ways depending on their molecular weight, architecture and self-assembly behavior. Low-molecular-weight glycolipids such as sophorolipids, MELs and cellobiose lipids readily self-assemble above their critical micelle concentration into micelles, vesicles or other supramolecular aggregates. These structures act as nanoscopic reaction domains that concentrate metal ions, redox-active cofactors and biosurfactant headgroups in confined volumes, thereby accelerating electron transfer and metal-ion reduction and strongly affecting nucleation and early growth. The curvature and packing of these aggregates can bias nanoparticle size and morphology, favoring small, roughly spherical particles when curvature is high, and more elongated or anisotropic structures when biosurfactant packing allows lower-curvature interfaces or more extended assemblies [45,46].

In contrast, higher-molecular-weight or more polymeric biosurfactants, including complexes of glycolipids with proteins or polysaccharides, tend to form thicker interfacial layers around growing nanoparticles, providing strong steric stabilization and slowing coalescence and Ostwald ripening. These “soft shells” can lead to colloids with enhanced kinetic stability and well-defined surface functionalities, but may also hinder mass transfer of reactants to the nanoparticle surface and partially mask catalytic or antimicrobial sites, effects that can be beneficial or detrimental depending on the target application [47,48]. The balance between low-molecular-weight glycolipids that favors fast nucleation and narrow size distributions, and more polymeric biosurfactant structures that enhance steric stabilization, is therefore a central design variable when using yeast-derived biosurfactants as mediators of nanoparticle synthesis. The surface activity and self-assembly properties that enable this control over nucleation and stabilization can also impact foam formation and broth rheology under aerated, stirred conditions; these process-level challenges and their implications for biorefinery integration are discussed in more detail in Section 8 [47].

From an industrial perspective, yeast biosurfactants already have a foothold in pilot- and commercial-scale processes, particularly sophorolipids produced by strains of Starmerella bombicola and MELs from Moesziomyces spp. in fed-batch or repeated-batch fermentations using sugar- and oil-based residues as co-substrates [49,50,51]. These processes demonstrate that high titres of glycolipid biosurfactants can be obtained from agro-industrial by-products under controlled conditions, and techno-economic and life-cycle assessments have begun to explore their integration into biorefinery concepts [50,52]. In contrast, nanoparticle synthesis mediated by these biosurfactants remains largely confined to laboratory-scale studies, typically conducted in small batch reactors with purified biosurfactant or cell-free supernatants [47,53]. This gap between mature biosurfactant production and early-stage nanoparticle applications suggests a realistic near-term pathway: first, to exploit existing sophorolipid and MEL production platforms in lignocellulosic biorefineries, and then to couple them with dedicated, well-characterized nanoformulation steps, rather than assuming fully integrated “one-pot” nanoparticle synthesis from the outset.

4.2. Exopolysaccharides (EPS)

Yeast-derived exopolysaccharides (EPS), such as β-glucans and heteropolysaccharides, are high-molecular-weight polymers enriched with hydroxyl groups capable of interacting with metal ions [54]. In hydrolysates, EPS production often arises under stress, providing cellular protection and extracellular scaffolds. In nanotechnology, EPS act as natural reductants and capping agents, enabling the synthesis of stable metallic and metal oxide nanoparticles. Reports highlight EPS-mediated silver and zinc oxide nanoparticles with antimicrobial and antioxidant functions [55,56]. Beyond stabilization, EPS-based nanocomposites find applications in food packaging, biomedical coatings, and pollutant remediation, exemplifying their versatility in the bioeconomy.

Structurally, yeast EPS typically consist of β-1,3- and β-1,6-linked glucan backbones, sometimes combined with heteropolysaccharidic regions bearing side chains and, in some cases, carboxyl or phosphate groups. This architecture provides a dense array of hydroxyl and other functional groups that can coordinate metal ions through hydrogen bonding, electrostatic interactions and chelation. During nanoparticle synthesis, EPS can thus play a dual role: they serve as mild reductants—by donating electrons from hydroxyl-rich domains and associated metabolites—and as three-dimensional scaffolds in which metal nuclei are formed and immobilized. As nanoparticles nucleate and grow within or on the surface of the polysaccharide network, the surrounding matrix limits coalescence and constrains growth, often leading to small, relatively monodisperse cores embedded in a hydrated polymer shell [57,58,59].

This EPS-derived shell contributes to colloidal stability through a combination of steric and, when charged groups are present, electrosteric repulsion. Thick polysaccharide layers increase the effective hydrodynamic diameter measured by dynamic light scattering while maintaining small inorganic cores observed by electron microscopy, highlighting the importance of distinguishing between core size and polymer-coated particle size. The density, branching and molecular weight of the EPS strongly influence these properties: highly branched, high-molecular-weight EPS can create crowded interfacial regions that efficiently prevent aggregation but may also hinder diffusion of reactants and products to and from the nanoparticle surface, with direct consequences for catalytic or antimicrobial performance [59,60].

At the bioprocess scale, EPS accumulation in lignocellulosic hydrolysates can substantially increase broth viscosity, modify rheology and affect mass and heat transfer in stirred and aerated reactors. In moderate amounts, this can be advantageous for film formation and the generation of EPS–nanoparticle nanocomposites for packaging or coating applications; at higher titers, however, it complicates mixing, oxygen transfer and solid–liquid separation, requiring careful control of operating conditions [58,61]. In contrast, nanoparticle synthesis directly mediated by yeast EPS remains largely restricted to laboratory-scale studies, often using purified polymers or cell-free supernatants obtained under well-defined stress conditions. Rather than acting as primary in situ reductants in highly viscous hydrolysate fermentations, EPS may therefore be more strategically positioned as structural matrices for nanocomposite films, hydrogels and coatings, where their film-forming ability, hydration capacity and biocompatibility are key design attributes. In a lignocellulosic biorefinery context, this suggests process configurations in which EPS are recovered or enriched as co-products and subsequently combined with preformed nanoparticles in downstream formulation steps, instead of relying on EPS-driven nanoparticle nucleation inside the fermentation broth [61,62].

4.3. Mannoproteins and Enzymes

Mannoproteins, structural components of the yeast cell wall, exhibit amphiphilic properties and reactive groups (amine, hydroxyl, carboxyl) that enable chelation and stabilization of metal nanoparticles. Enzymes produced by yeasts, particularly oxidoreductases, hydrolases, and dehydrogenases, further expand this set of molecular mediators. For instance, nitrate reductase and related oxidases catalyze the reduction of silver or gold salts into nanoparticles with controlled size and morphology [63,64,65,66]. These molecules illustrate how yeasts operate as living nanocatalysts, bridging biomass conversion with nanomaterial synthesis. In biorefineries, mannoproteins and enzymes not only support hydrolysis and fermentation but also contribute directly to NP functionalization and bioactivity.

At the molecular scale, mannoproteins consist of heavily glycosylated polypeptides anchored to a β-glucan network, combining hydrophobic peptide segments with extended, hydrophilic mannan chains [67,68,69,70]. This arrangement generates multiple binding sites for metal species—via carboxylate, hydroxyl and, to a lesser extent, amine groups—and favors adsorption of metal complexes on the cell envelope [68,69,70]. During nanoparticle formation, metal ions can bind to these residues, be reduced in their vicinity and form nuclei that remain partially embedded within the mannoprotein–glucan matrix [68,71,72]. The resulting protein-rich layer acts as a corona that provides steric and sometimes electrostatic repulsion, influencing colloidal stability, surface charge and interaction with biological targets [72,73,74]. Variations in mannoprotein composition and abundance between species, strains and growth conditions are therefore expected to translate into differences in size distributions, zeta potential and adsorption behavior, although these relationships remain poorly quantified and rarely reported in a systematic way [69,70].

Enzymes add a dynamic, redox-active component to this scenario. Oxidoreductases such as nitrate reductase, dehydrogenases and oxidases can channel electrons from intracellular or extracellular metabolites (e.g., NADH, organic acids, reduced cofactors) to metal ions, accelerating their reduction and initiating nucleation [64,72,74,75]. Hydrolases and glycosidases remodel the extracellular environment by releasing oligomers and polysaccharides that can act as additional capping agents or modify local viscosity and diffusion [67,69]. In whole-cell systems, expression and activity of these enzymes depend strongly on carbon source, oxygen availability and stress, so the same yeast strain may exhibit very different capacities for metal reduction and capping under different process regimes [64,72,75]. This enzyme-driven control is attractive because it offers handles to tune nucleation and growth kinetics via medium composition and culture conditions, but it also complicates reproducibility and mechanistic interpretation if enzyme activities and cofactor levels are not measured alongside standard spectroscopic and microscopic readouts [64,74].

Functionally, the combination of mannoprotein coronas and enzyme activity largely defines the “biological identity” of yeast-derived nanostructures. Glycoprotein coatings can provide recognition motifs, binding sites and stealth properties that modulate antimicrobial, catalytic or drug-delivery performance, while residual enzymes associated with the particles may contribute to reactive oxygen species generation or localized biocatalysis. At the same time, proteinaceous coronas are sensitive to pH, temperature and proteolysis, and can be displaced or restructured in complex matrices such as lignocellulosic hydrolysates, soils or biological fluids. For applications in food, agriculture or biomedicine, issues such as immunogenicity, batch-to-batch variability of protein composition and long-term stability of the corona need to be explicitly addressed rather than assuming that all “biogenic” coatings are inherently safe or functionally equivalent [70,72,73].

Within lignocellulosic biorefineries, cell-wall mannoproteins and extracellular enzymes are already central to hydrolysis, nutrient uptake and stress adaptation during fermentation. Their potential roles in nanoparticle formation point to two complementary implementation routes. One is to use intact or minimally processed yeast biomass as a low-cost, regenerable platform in which cell walls act simultaneously as biosorbents for metal ions and as scaffolds for nucleation and stabilization The other is to isolate or enrich specific mannoprotein and enzyme fractions for use as defined biocatalysts and capping agents in downstream nanoformulation steps, decoupling nanomaterial synthesis from the constraints of live-cell operation [68,69,71,72].

4.4. Pigments and Organic Acids

Beyond biosurfactants and polysaccharides, yeasts also accumulate a wide range of low- and high-molecular-weight metabolites, including pigments such as carotenoids (e.g., β-carotene, torulene, astaxanthin) and melanin, as well as organic acids such as citric, succinic and itaconic acids [76,77]. These metabolites are redox-active, providing electron-donating capacity and strong metal-binding potential. Melanin has been exploited in the biosynthesis of gold nanoparticles, imparting enhanced stability and photothermal activity [78]. Organic acids, in turn, act as both pH modulators and chelating agents, enabling controlled reduction and stabilization of nanoparticles [79,80]. Pigments add optical and antioxidant functionalities, broadening the multifunctionality of nanomaterials derived from yeast biorefineries.

From a molecular perspective, carotenoids are highly conjugated polyenes embedded in yeast membranes or associated with lipid droplets, where their extended π-electron systems underpin radical-scavenging and electron-transfer reactions. In principle, this conjugation allows carotenoids to behave as mild reducing agents and to interact with metal species through π–metal and hydrophobic interactions, thereby influencing nucleation and surface chemistry of nanostructures [81,82]. Melanin, in turn, is a heterogeneous, redox-active polymer rich in aromatic and quinone/semiquinone motifs, together with functional groups (carboxyl, hydroxyl, amine) that confer strong metal-binding capacity [83]. Fungal melanins, including those produced by yeasts, have been implicated in the biosynthesis of metal nanoparticles, where the polymer can complex metal ions, mediate their reduction to the zero-valent state and form a robust coating around the particles, enhancing colloidal stability and photothermal response [84,85,86].

Viewed through the lens of coordination chemistry, organic acids provide an additional level of control over nanoparticle formation. Metabolites such as citrate, succinate and itaconate act as both pH buffers and multidentate ligands, shifting metal ions between free and complexed forms and thereby altering reduction kinetics, nucleation rates and preferred crystal phases. Citrate-like coordination, well known from classical chemical routes, can similarly arise in yeast-derived systems, where produced acids compete with proteins, polysaccharides and biosurfactants for binding sites on nascent nanoparticle surfaces. Depending on concentration and pH, these small anions may promote the formation of small, negatively charged cores with good colloidal stability, or, if complexation is too strong or heterogeneous, slow reduction and lead to broader size distributions [85,86].

From a process and scale-up standpoint, pigment and organic acid titres are tightly linked to carbon source, C/N ratio, oxygen availability and stress conditions. Carotenogenic yeasts often accumulate pigments under nutrient limitation or oxidative stress, whereas organic acid production can increase under overflow metabolism or specific redox imbalances. In lignocellulosic biorefineries, this implies that the same yeast–hydrolysate combination can generate very different pigment and acid profiles depending on how fermentation is operated. On one hand, this offers process levers to tune nanoparticle synthesis—for example, by adjusting dissolved oxygen, feeding strategies or pH to favor melanin or organic acid accumulation when their redox and chelating properties are advantageous. On the other hand, it introduces additional sources of variability: shifts in pigment and acid levels can alter nanoparticle size, surface charge and optical properties from batch to batch, and excessive acid production may compromise cell robustness, corrosion behavior or downstream separations [81,85,86].

Functionally, pigment–acid systems extend the portfolio of yeast-derived nanomaterials beyond simple metal cores capped by generic stabilizers. Melanin- or carotenoid-associated nanoparticles can exhibit enhanced photothermal, antioxidant or light-harvesting properties, opening possibilities for photocatalysis, imaging, sensing and active packaging [83]. Organic acid capping can improve biocompatibility and colloidal stability, particularly in aqueous and mildly acidic environments relevant to food, agricultural and environmental applications [85,86]. However, fully exploiting these advantages in an industrial context will require more systematic mapping of how pigment and organic acid profiles correlate with nanoparticle characteristics, and clearer discrimination between the roles of pigments, small organic acids and co-produced macromolecules [82,84,85,86]. Without such quantitative structure–function relationships, it remains difficult to disentangle which metabolite classes are actually driving reduction, which are primarily responsible for capping, and how robust these effects are under realistic biorefinery conditions.

Table 3 summarizes the main classes of yeast-derived biomolecules, highlighting their structural features, mechanisms in nanoparticle biosynthesis, and representative applications within lignocellulosic biorefineries.

Table 3.

Yeast species, agro-industrial substrates and biomolecules involved in nanoparticle biosynthesis.

4.5. Closing Remarks

Together, these biomolecules represent a multifunctional molecular repertoire that redefines the role of yeasts in lignocellulosic biorefineries. They serve not only as metabolic core platforms for fuel and biochemical production but also as bio foundries of nanostructures, capable of reducing, stabilizing, and functionalizing nanoparticles under sustainable conditions. By integrating biomass valorization, yeast metabolism, and nanobiotechnology, these biomolecules establish a roadmap for disruptive innovations in the circular bioeconomy.

5. Green Nanotechnology and the Role of Yeast Biomolecules

Harnessing lignocellulosic biomass is not only about overcoming its structural complexity but also about unlocking new sets of molecular mediators capable of driving sustainable innovation. Yeasts, beyond their role as fermentative core platforms in biorefineries, they generate biomolecules, that were initially valued for improving hydrolysis, fermentation, or stabilization of process streams. Today, the very same molecules are being redefined as mediators of nanoscience. Their amphiphilicity, redox activity, and ability to chelate metal ions make them natural catalysts for the reduction, nucleation, and stabilization of nanoparticles. In this sense, biorefineries are no longer limited to fuels and chemicals: they become platforms for nanomaterial innovation.

From a mechanistic and energetic perspective, yeast-mediated nanoparticle synthesis can be viewed as a cascade that diverts metabolic reducing power into metal nucleation and colloidal stabilization [99]. During lignocellulosic sugar catabolism, pathways such as glycolysis and the pentose phosphate pathway generate NADH and NADPH, which sustain intracellular redox balance and fuel the formation of redox-active metabolites (e.g., glutathione, quinones, phenolic pigments) [100,101]. Under overflow conditions—high carbon flux combined with nitrogen or oxygen limitation—yeasts and other fungi also accumulate organic acids and polyols that simultaneously chelate metal ions and act as mild electron donors [102,103]. Together with carboxyl- and hydroxyl-rich exopolysaccharides and biosurfactants, these metabolites first complex Mⁿ+ species, lowering the free-energy barrier for nucleation, and then mediate stepwise reduction to M0 nanoclusters [104,105]. Amphiphilic coatings provided by biosurfactants and mannoproteins finally arrest growth at the nanoscale by decreasing surface free energy and providing electrosteric repulsion [105,106]. In this way, central carbon metabolism and stress-responsive pathways define an integrated “biological energy scheme” that links reduction, nucleation and stabilization in yeast-driven green nanotechnology [99].

At the nanoscale (1–100 nm), matter expresses unique physicochemical behaviors—quantum effects, enhanced surface reactivity, catalytic versatility, and antimicrobial activity—that cannot be achieved by bulk materials [107,108]. These properties fuel advances in medicine, catalysis, packaging, and environmental remediation. Yet conventional synthesis routes, such as chemical reduction with sodium borohydride, thermal decomposition, or high-energy irradiation, remain dependent on toxic reagents, hazardous by-products, and energy-intensive setups [109]. This raises critical concerns over scalability, environmental safety, and regulatory acceptance, undermining their integration into sustainable value chains.

Green nanotechnology disrupts this paradigm by replacing harsh reagents with biological molecules capable of dual action: reducing metal ions and stabilizing the resulting colloids [74]. Within this context, yeast-derived biomolecules stand out as a distinctive advantage. Biosurfactants such as sophorolipids and mannosylerythritol lipids, exopolysaccharides enriched with hydroxyl groups, mannoproteins with amphiphilic binding sites, and pigments or organic acids with strong redox capacity collectively enable precise control of nanoparticle size, morphology, and stability [110]. Unlike plant extracts or bacterial cultures, whose composition fluctuates with environmental conditions, yeast biomolecules can be produced in controlled fermentations, with composition fine-tuned through substrates derived directly from lignocellulosic hydrolysates.

This controlled production connects two fronts of the circular bioeconomy: valorization of agro-industrial residues and synthesis of nanomaterials with functional properties. Compared to bacteria—which may involve pathogenic producers—or plants and algae, which require extensive cultivation areas, yeasts combine safety (GRAS status), compact growth, and industrial scalability [111,112]. They also integrate seamlessly into biorefineries, where sugarcane bagasse, corn steep liquor, or fatty acid distillates serve simultaneously as fermentation substrates and feedstocks for nanomaterial production [113]. This coupling transforms biorefineries into hubs that deliver not only renewable fuels and chemicals but also advanced nanomaterials for environmental and biomedical applications.

In this vision, yeast biomolecules are not only sustainable alternatives to chemical reagents but also transformative agents capable of redefining the intersection between biorefineries and nanotechnology. Green nanotechnology is no longer peripheral—it becomes central to the expansion of lignocellulosic biorefineries into high-value, multifunctional product pipelines.

To reinforce this comparison with quantitative data, Table 4 summarizes representative examples of yeast-mediated and chemically synthesized nanoparticles, highlighting differences in particle size, functional performance, stability, and process conditions.

Table 4.

Comparative physicochemical and functional metrics of yeast-mediated and chemically synthesized nanoparticles.

As illustrated by the cases compiled in Table 4, nanoparticles obtained via yeast-derived biomolecules often display physicochemical and functional profiles that differ from those produced by conventional chemical reducers. For instance, silver and zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using cell-free yeast extracts or filtrates typically fall within the 5–30 nm range and exhibit narrow size distributions, stable surface plasmon resonance bands and ζ-potentials compatible with long-term colloidal stability, while maintaining high antimicrobial or antioxidant activity at relatively low doses [114,115,116,117]. In contrast, chemically synthesized AgNPs prepared by sol–gel or NaBH4 reduction under similar nominal conditions tend to show larger hydrodynamic diameters, signs of aggregation (e.g., broader SPR bands, less negative ζ-potentials) and, in some reports, comparable or lower antimicrobial efficacy at equal or higher concentrations [118,119]. These trends suggest that the complex coronas formed by yeast-derived biosurfactants, polysaccharides and proteins can promote the formation of smaller, better-dispersed cores with enhanced interfacial reactivity, rather than merely replacing synthetic capping agentes.

Beyond their sustainability profile, yeast-derived biomolecules therefore provide several additional advantages for nanoparticle synthesis. First, they enable in situ biofunctionalization: mannoproteins, exopolysaccharides and glycolipid biosurfactants adsorb on nascent nanoparticle surfaces, generating biologically meaningful coronas that can impart antimicrobial, antibiofilm, antioxidant or catalytic functions without post-synthesis modification steps [31,70,99,105]. Second, the absence of strong synthetic reductants such as NaBH4 or hydrazine reduces the risk of residual toxic reagents and simplifies toxicological assessment, particularly for applications in food, agriculture and biomedicine [120]. Third, yeast-derived coatings often improve colloidal stability in saline or protein-rich environments, where conventionally capped nanoparticles may aggregate or lose activity, because biosurfactant- and mannoprotein-based shells provide robust electrosteric barriers and maintain surface functionality under complex conditions [70,105,121]. Taken together, these features indicate that yeast-mediated routes not only decarbonize nanoparticle production but also expand the design space toward nanostructures with intrinsically bioactive, biocompatible and application-tailored surface chemistries.

6. Mechanisms of Yeast-Mediated Nanoparticle Synthesis

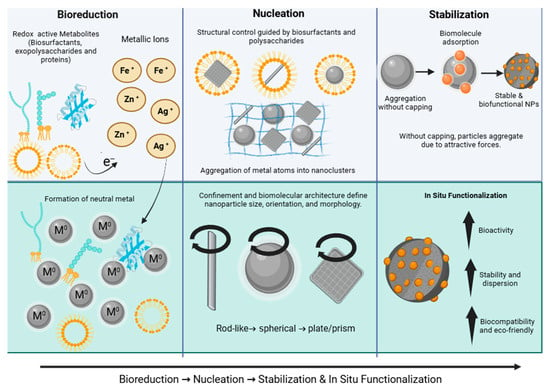

The biosynthesis of NPs by yeasts is a multistep process governed by biochemical interactions and environmental conditions. It typically unfolds through three core stages—bioreduction, nucleation, and stabilization—but is also shaped by the site of synthesis (extracellular vs. intracellular) and process parameters that dictate yield, morphology, and biofunctionality [122].

6.1. Bioreduction

The initial stage involves the conversion of metal ions into elemental atoms through electron donation. Functional groups such as hydroxyl, carbonyl, and carboxyl, together with reducing metabolites including NADH, quinones, flavonoids, and glutathione, act as electron donors [123,124]. Enzymes such as nitrate reductase and dehydrogenases accelerate these redox reactions, while pH exerts strong control over reaction kinetics [75]. Under mildly alkaline conditions, the efficiency of electron transfer increases, setting the foundation for rapid nanoparticle formation.

6.2. Nucleation

Once reduced, atoms aggregate into nanoclusters within supramolecular micro-environments such as micelles, protein scaffolds, or polysaccharide networks. These confined domains regulate crystal growth, orientation, and the final morphology of nanoparticles. For example, studies with sophorolipid biosurfactants show that simpler or shorter-chain glycolipid structures tend to favor the formation of small, predominantly spherical metal nanoparticles, whereas more asymmetric or branched sophorolipid molecules can promote deviations from perfect sphericity and the appearance of anisotropic morphologies [125,126]. This stage is crucial for defining particle size distribution and functional properties.

6.3. Stabilization and In Situ Functionalization

Stability of the nanoparticles is achieved through electrostatic repulsion—conferred by negatively or positively charged groups such as carboxylates, amines, and phosphates—and steric hindrance, mediated by hydrophobic tails and polysaccharide backbones. Together, these mechanisms prevent aggregation and preserve colloidal reactivity [127,128].

A unique advantage of yeast systems is their ability to achieve in situ functionalization. During NP formation, mannoproteins, exopolysaccharides, and biosurfactants adsorb onto particle surfaces, imparting bioactive traits such as antimicrobial activity, catalytic sites, or drug-conjugation capacity [99,129]. Unlike conventional synthesis, which often requires post-synthesis surface modification, yeast-mediated synthesis inherently generates biofunctional nanoparticles.

Figure 1 illustrates the three mechanistic stages previously described—bioreduction, nucleation, and stabilization/functionalization—highlighting the role of yeast-derived biomolecules in each step.

Figure 1.

Bioreduction, Nucleation, and Stabilization Pathways in Yeast-Assisted Nanoparticle Biosynthesis Created in https://BioRender.com.

6.4. Extracellular Versus Intracellular Synthesis

Yeasts Employ Two Distinct Pathways for Nanoparticle Formation

Yeasts employ two main pathways for nanoparticle (NP) formation, and each route has distinct implications for scale-up, separation and regulatory assessment.

Extracellular synthesis occurs when metal ions are reduced and stabilized by biomolecules produced and released into the culture medium. The resulting nanoparticles form directly in the supernatant, which can then be clarified by conventional operations such as centrifugation, microfiltration or tangential-flow ultrafiltration. This route is particularly attractive for industrial production of colloidal dispersions, because cells can be removed early and downstream processing resembles that of other fermentation-derived metabolites. However, the physicochemical environment in the broth is relatively heterogeneous, and competition among different capping agents often leads to broader size distributions and batch-to-batch variability in surface chemistry [130,131].

In intracellular synthesis, metal ions are transported across the cell envelope and reduced by cytoplasmic or organelle-associated enzymes and metabolites. The confined environment inside organelles and vesicles can promote more uniform nucleation and growth, so intracellularly formed nanoparticles are frequently smaller and more monodisperse than their extracellular counterparts [130]. From an industrial perspective, this tighter size control is offset by more complex recovery: cells must be harvested, disrupted (e.g., by high-pressure homogenization or bead milling) and the nanoparticles separated from dense cell debris. These additional unit operations increase energy demand, capital costs and fouling risks, and they can introduce biological impurities that are problematic for high-purity or regulatory-sensitive applications [130,132].

From a techno-economic standpoint, extracellular routes are generally associated with lower downstream-processing intensity, because they avoid cell disruption and reduce the number of solid–liquid separation steps. This typically translates into lower energy demand, simpler equipment trains and reduced capital expenditure, especially when nanoparticles can be recovered by clarification and membrane operations similar to those used for conventional fermentation products [130,133]. Recent work on cell-free yeast extract-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles, for example, shows that such extracellular systems can be implemented in stirred-tank reactors using renewable feedstocks, with process schemes explicitly described as cost-effective, environmentally friendly and scalable [131]. Reviews on fungal- and yeast-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles likewise emphasize that extracellular routes are experimentally simple, compatible with existing bioprocessing infrastructure and amenable to scale-up [133]. In contrast, intracellular synthesis workflows require biomass harvesting, mechanical or chemical disruption and multi-stage separations to remove dense cell debris, which tends to shift the cost structure towards downstream processing and raises concerns about biological impurities and toxicological assessment in high-purity applications [130,134]. As a result, intracellular routes are more likely to be economically viable in scenarios where nanoparticles are used together with the producing cells as reusable whole-cell catalysts or biosorbents, rather than as isolated colloids [132,135]. Overall, available data suggest that extracellular yeast-based processes are better aligned with current large-scale biomanufacturing and regulatory frameworks, while intracellular approaches remain attractive for specialized, high-value applications where superior size control or integrated biocatalytic functions justify the additional processing costs [130,131,132,133,134,135].

6.5. Influence of Process Parameters

Critical variables such as pH, temperature, precursor concentration, agitation and oxygen availability strongly affect nanoparticle synthesis. Mildly alkaline pH and moderate heating often accelerate nucleation kinetics and metal-ion reduction, whereas oxygen limitation can induce the accumulation of reductive metabolites, enhancing bio reduction but also increasing the risk of uncontrolled nucleation. Precursor concentration correlates with NP yield but also with aggregation when the supply of capping molecules is insufficient, particularly in extracellular systems were produced and released biomolecules are diluted in the bulk medium. Agitation and oxygen transfer further modulate both nanoparticle formation and yeast physiology, influencing stress responses, pigment production and organic acid secretion. Optimizing these parameters—frequently through design-of-experiments approaches—is therefore essential to balance productivity, monodispersity and colloidal stability, and to ensure that small-scale conditions can be translated into reproducible and scalable biosynthesis at reactor level [64,136].

Representative examples of yeast-mediated nanoparticle synthesis are summarized in Table 5, highlighting the diversity of yeast species, biomolecular mediators, synthesis mechanisms, and functional outcomes across different nanoparticle systems.

Table 5.

Yeast-mediated nanoparticle synthesis: species, biomolecular mediators, mechanisms and functional outcomes in green nanotechnology.

These representative cases demonstrate that yeast-derived biomolecules are not passive stabilizers but active molecular architects—providing reduction capacity, surface functionalization, and bioactivity. Their structural diversity enables nanoparticles with tailored functions, directly linking biorefineries to sustainable nanotechnology.

7. Industrial Applications and Case Studies

Yeast-mediated nanoparticles have progressed beyond proof-of-concept and are now being explored in several application domains. In food and packaging, Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell-free extracts have been used to generate extracellular silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) with sizes in the 10–30 nm range and negative zeta potentials, which exhibit broad-spectrum antibacterial activity and are explicitly described as scalable and cost-effective when produced in stirred-tank reactors [114]. These and related yeast-mediated AgNPs have been incorporated into emulsions or edible films to inhibit spoilage bacteria and extend the shelf life of fresh produce, mirroring the performance of other biogenic AgNPs already tested in whey-based coatings and polysaccharide films [143]. Laboratory studies with S. cerevisiae-mediated AgNPs consistently report strong inhibition zones against multidrug-resistant isolates of Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa [144], supporting their use as active components in antimicrobial packaging and surface sanitizers.

In catalysis and process intensification, glycolipid-stabilized gold nanoparticles provide a representative example. Mannosylerythritol lipid (MEL) biosurfactants from Moesziomyces antarcticus have been used as templating and capping agents to produce AuNPs with narrow size distributions (~10–30 nm), high colloidal stability and well-defined surface chemistry [44]. These MEL–AuNP systems show promising activity in model redox reactions such as 4-nitrophenol reduction, while the MEL corona offers additional handles for immobilization on supports and for tuning interfacial properties [145]. Such nanocatalysts conceptually integrate well with biorefineries where MELs are already produced from waste oils and sugars, enabling catalytic “bolt-on” modules that valorize side streams or intensify specific upgrading steps without introducing synthetic surfactants.

Agricultural and environmental applications of yeast-based nanomaterials are also emerging. Carbonized yeast cells containing in situ formed AgNPs have been developed as adsorbents for arsenate removal from water, achieving high As(V) uptake capacities and enabling magnetic or gravimetric separation after treatment [146]. More broadly, biogenic metal and metal oxide nanoparticles are being evaluated as components of nanofertilizers and nano-enabled amendments that enhance nutrient use efficiency, immobilize heavy metals or contribute to the degradation of pesticide residues; the use of yeast biomass as a low-cost, regenerable scaffold for such hybrids is increasingly highlighted in recent reviews of microbial nanotechnology [99]. These examples illustrate how yeast-based processes can couple waste valorization (spent biomass, hydrolysates) with water treatment and soil remediation functions.

In the biomedical arena, yeast-mediated nanoparticles have attracted attention due to their combined antimicrobial, antioxidant and immunomodulatory properties. Reviews on yeast-derived nanomaterials report S. cerevisiae as an efficient “factory” for selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs) and AgNPs, which display strong antibacterial and antifungal activity along with reduced cytotoxicity compared with some chemically synthesized analogs [99,147]. Yeast-synthesized SeNPs, in particular, have been investigated as nutraceutical and therapeutic candidates: preclinical studies show that SeNPs produced by S. cerevisiae can accelerate gastric ulcer healing via antioxidant and anti-inflammatory mechanisms [148], while other biogenic SeNP formulations exhibit antibiofilm, antioxidant and low-toxicity profiles compatible with applications in wound management and functional foods [147]. When combined with the intrinsic GRAS status and production scalability of many yeast strains, these findings support the positioning of yeast-based nanoplatforms as promising contenders for antimicrobial dressings, targeted delivery systems and bioactive food-contact materials.

Overall, the current case studies demonstrate that yeast-mediated nanoparticles are not confined to abstract “green” synthesis, but already interface with real application spaces in packaging, catalysis, environmental remediation and biomedicine. At the same time, most demonstrations remain at laboratory scale, and systematic data on long-term performance, regulatory compliance and techno-economic viability are still limited—issues that are taken up in detail in Section 8. Bridging this gap between lab-scale functionality and industrial reality will be crucial for yeast-based nanoplatforms to become fully integrated products within lignocellulosic biorefineries.

8. Challenges and Limitations

Although there is a growing number of proof-of-concept studies, yeast-mediated nanoparticle synthesis is still far from industrial reality. Much of the current literature is driven by the excitement of “green nanotechnology”, but often stops at showing color changes, UV–Vis bands and a few TEM images. A more critical look reveals several gaps that must be addressed before these systems can be credibly integrated into biorefineries or other industrial processes. Recent reviews on green and microbial nanoparticle synthesis also highlight issues of batch-to-batch variability, inconsistent reporting and limited mechanistic insight [57,99,123,124]. Addressing these gaps will require not only better biology and engineering, but also more realistic process evaluation and stronger dialog with regulatory frameworks.

8.1. Biological Variability and Limited Quantitative Control

One of the main bottlenecks is the strong dependence of nanoparticle formation on poorly controlled biological factors. The amount and composition of yeast-derived biomolecules change with strain, carbon source, oxygen supply, stress conditions and even inoculum preparation. Not surprisingly, particle size, morphology and surface chemistry vary widely from one study to another, sometimes even within the same yeast species. Recent analyses of green synthesis routes, including microbial systems, explicitly point to this batch-to-batch variability and the difficulty of controlling biomolecular composition as a major limitation for reproducibility and scale-up [86,99,124]. Claims of “monodisperse” or “stable” nanoparticles are frequently based on a single DLS curve or a handful of TEM images, with little or no information on batch-to-batch variation or long-term stability under realistic process conditions (high ionic strength, shear, temperature shifts). From an industrial perspective, this level of uncertainty is problematic, especially for applications that require tight specifications and regulatory approval. A concrete way forward is to combine more systematic bioprocess design (design-of-experiments, defined feed strategies, strict pH and DO control) with multi-omics-guided strain engineering and standardized reporting of nanoparticle properties and their variability, in line with broader recommendations for bio–nano systems [149,150]. This would gradually transform yeast-mediated synthesis from a qualitative “black box” into a quantitatively controllable platform.

8.2. Scale-Up, Process Integration and Techno-Economic Realism

A second challenge appears when we move from laboratory flasks to the scale of a biorefinery. Most published studies rely on small-scale batch experiments using relatively simple media and purified metal salts. When lignocellulosic hydrolysates are used, they are often detoxified, clarified or diluted to the point where the complexity of an actual process stream is no longer represented. Under real conditions, high solids, fluctuating inhibitor profiles, foaming due to biosurfactants and changes in viscosity will all affect mixing, mass transfer and nanoparticle nucleation. Very few works discuss these issues explicitly, and even fewer provide basic mass balances, volumetric productivities or techno-economic analyses to show whether yeast-mediated nanoparticles could be competitive with conventional chemical routes. Bioprocess simulations and techno-economic assessments for biogenic nanomaterials consistently show that yields, downstream processing and plant integration are decisive for economic viability [151,152,153]. As long as scale-up criteria (kLa, mixing times, foam management, shear sensitivity of cells) and integrated flowsheets remain largely unexplored, the promise of “in situ nanomaterials within biorefineries” will stay mainly conceptual. A practical solution is to move stepwise from shake flasks to controlled lab-scale and pilot reactors using realistic, minimally processed hydrolysates, while coupling experimental work to process modeling, techno-economic evaluation and, eventually, life-cycle assessment, following recent examples of LCA applied to “green” nanomaterials and safe-and-sustainable-by-design frameworks [151,152,154,155]. This would clarify under which conditions yeast-based nanomaterials genuinely add value to lignocellulosic biorefineries.

8.3. Regulatory, Safety and Environmental Questions

Another critical gap concerns regulation and safety. Yeast-based nanomaterials are often described as “green” simply because they avoid strong reducing agents or extreme conditions. However, the presence of complex biomolecular coronas on nanoparticle surfaces (biosurfactants, EPS, proteins, pigments) complicates their detection, standardization and toxicological assessment. Recent reviews on nanoparticle fate and toxicity show that even “green-synthesized” materials can accumulate in soils, aquatic systems or biota, with outcomes that depend sensitively on surface chemistry and environmental transformations [156,157]. Most yeast-based studies limit biological evaluation to short-term antimicrobial, antioxidant or cytotoxicity assays. There is very little information on long-term stability, transformation and fate of these nanoparticles in soils, aquatic systems, food contact materials or the human body. For applications in agriculture, packaging, cosmetics or environmental remediation, detailed toxicological data, standardized characterization protocols and life-cycle assessments will be required. At the moment, these aspects are largely missing, which creates a real barrier for technology transfer, regardless of how sustainable the upstream synthesis might appear. Addressing this challenge will require early collaboration with toxicologists and regulatory experts, adoption of safe-and-sustainable-by-design approaches and existing testing frameworks for nanomaterials, and the incorporation of life-cycle thinking into yeast-based nanoparticle development from the outset [151,152,154,158].

8.4. Methodological Fragmentation and Poor Comparability

Finally, the field is highly fragmented from a methodological point of view. Studies differ widely in inoculum age, medium composition, metal precursor concentration, pH regime and reaction time, often without a clear rationale. Analytical tools are also used unevenly: UV–Vis and TEM are almost always present, but zeta potential, FTIR, XPS, TGA and rigorous DLS analyses are not consistently applied. Negative results are rarely reported, which skews the literature towards success stories and makes it difficult to gauge how robust these systems truly are. This lack of common ground makes cross-comparison between studies difficult and delays the emergence of simple “design rules” linking specific yeast metabolites (for example, sophorolipids versus mannosylerythritol lipids versus EPS) to well-defined nanoparticle properties. Similar concerns have driven broader initiatives to define minimum information and characterization standards for nanomaterials and bio–nano systems [149,158]. One way to move beyond this fragmentation is to develop community guidelines or “minimum information” checklists for yeast-mediated nanoparticle synthesis, inspired by these existing initiatives that define essential process descriptors and core characterization requirements. Such harmonization would greatly enhance comparability, meta-analysis and rational process design.

In summary, yeast-mediated nanoparticle synthesis is frequently presented as an inherently sustainable alternative, but a closer and more critical inspection shows substantial gaps in reproducibility, scale-up, techno-economic justification, regulatory readiness and methodological standardization. Turning these challenges into opportunities will depend on coordinated efforts that link microbial physiology, process engineering, materials science and regulatory science, so that yeast-based green nanotechnology can evolve from attractive laboratory demonstrations into realistic options for next-generation biorefineries and circular bioeconomy strategies.

9. Conclusions

The convergence of lignocellulosic biorefineries and yeast-mediated nanotechnology is no longer a distant possibility—it is an emerging paradigm. The next frontier depends on five strategic moves: (i) standardization of synthesis and characterization to ensure reproducibility; (ii) integration with real hydrolysates and continuous bioprocesses to demonstrate scalability; (iii) omics-guided mapping of yeast biomolecules to establish predictive libraries linking structure to nanoparticle function; (iv) techno-economic and life-cycle analyses that prove superiority over petrochemical nanomaterials; and (v) cross-disciplinary alliances that merge microbiology, nanoscience, and engineering.

What lies ahead is not just incremental progress but a redefinition of industrial biotechnology. By transforming agro-industrial residues into bioactive nanoplatforms, yeasts can reposition themselves from fermentative core platforms to architects of a new nanobiotechnological era, driving circular bioeconomy from vision to reality.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.P.S.V., J.C.d.S. and S.S.d.S.; literature collection and analysis, F.P.S.V., N.J.C., G.A.L. and S.B.S.R.; critical discussion and data interpretation, F.P.S.V., K.A.G.B. and E.F.M.; writing—original draft preparation, F.P.S.V.; writing—review and editing, G.O.S., P.R.F.M. and S.S.d.S.; visualization and figure preparation, F.P.S.V. and G.O.S.; supervision and project coordination, S.S.d.S.; funding acquisition, S.S.d.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), Brazil (Finance Code 001), and by the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP), Brazil (grant number 2023/09789-8).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the School of Engineering of Lorena (EEL) at the University of Sao Paulo (USP) for providing access to their laboratories and facilities. The authors also thank INCT-Leveduras (CNPq 406564/2022-1), CNPq (304166/2022-7), FAPESP (Process 2023/09789-8) and CAPES (Code 001). During the preparation of this work the authors used the free version of CHATGPT (provided by OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA; available at https://openai.com/blog/chatgpt, accessed on 10 December 2025) in order to partially aid with the language edition. Afterwards, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kartal, M.T. The Role of Consumption of Energy, Fossil Sources, Nuclear Energy, and Renewable Energy on Environmental Degradation in Top-Five Carbon Producing Countries. Renew. Energy 2022, 184, 871–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farghali, M.; Osman, A.I.; Chen, Z.; Abdelhaleem, A.; Ihara, I.; Mohamed, I.M.A.; Yap, P.S.; Rooney, D.W. Social, Environmental, and Economic Consequences of Integrating Renewable Energies in the Electricity Sector: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21, 1381–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priefer, C.; Jörissen, J.; Frör, O. Pathways to Shape the Bioeconomy. Resources 2017, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowski, I. Securing a Sustainable Biomass Supply in a Growing Bioeconomy. Glob. Food Secur. 2015, 6, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubando, A.T.; Felix, C.B.; Chen, W.-H. Biorefineries in Circular Bioeconomy: A Comprehensive Review. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 299, 122585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baruah, J.; Nath, B.K.; Sharma, R.; Kumar, S.; Deka, R.C.; Baruah, D.C.; Kalita, E. Recent Trends in the Pretreatment of Lignocellulosic Biomass for Value-Added Products. Front. Energy Res. 2018, 6, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofsetz, K.; Silva, M.A. Brazilian Sugarcane Bagasse: Energy and Non-Energy Consumption. Biomass Bioenergy 2012, 46, 564–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auffan, M.; Rose, J.; Bottero, J.-Y.; Lowry, G.V.; Jolivet, J.-P.; Wiesner, M.R. Towards a Definition of Inorganic Nanoparticles from an Environmental, Health and Safety Perspective. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2009, 4, 634–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güleç, F.; Parthiban, A.; Umenweke, G.C.; Musa, U.; Williams, O.; Mortezaei, Y.; Suk-Oh, H.; Lester, E.; Ogbaga, C.C.; Gunes, B.; et al. Progress in Lignocellulosic Biomass Valorization for Biofuels and Value-Added Chemical Production in the EU: A Focus on Thermochemical Conversion Processes. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefining 2024, 18, 755–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajpai, P. Structure of Lignocellulosic Biomass. In Pretreatment of Lignocellulosic Biomass for Biofuel Production; Bajpai, P., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2016; pp. 7–12. ISBN 978-981-10-0687-6. [Google Scholar]

- Haq, I.U.; Qaisar, K.; Nawaz, A.; Akram, F.; Mukhtar, H.; Zohu, X.; Xu, Y.; Mumtaz, M.W.; Rashid, U.; Ghani, W.A.W.A.K.; et al. Advances in Valorization of Lignocellulosic Biomass towards Energy Generation. Catalysts 2021, 11, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J.; Sabapathi, S. Cellulose Nanocrystals: Synthesis, Functional Properties, and Applications. Nanotechnol. Sci. Appl. 2015, 8, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobsen, S.E.; Wyman, C.E. Cellulose and Hemicellulose Hydrolysis Models for Application to Current and Novel Pretreatment Processes. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2000, 84, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheller, H.V.; Ulvskov, P. Hemicelluloses. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2010, 61, 263–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.; Rani, A.; Dar, M.A.; Qaisrani, M.M.; Noman, M.; Yoganathan, K.; Asad, M.; Berhanu, A.; Barwant, M.; Zhu, D. Recent Advances in Characterization and Valorization of Lignin and Its Value-Added Products: Challenges and Future Perspectives. Biomass 2024, 4, 947–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancefield, C.S.; Weckhuysen, B.M.; Bruijnincx, P.C.A. Catalytic Conversion of Lignin-derived Aromatic Compounds into Chemicals. In Lignin Valorization: Emerging Approaches; The Royal Society of Chemistry: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmqvist, E.; Hahn-Hägerdal, B. Fermentation of Lignocellulosic Hydrolysates. I: Inhibition and Detoxification. Bioresour. Technol. 2000, 74, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenci Woiciechowski, A.; Dalmas Neto, C.J.; Porto de Souza Vandenberghe, L.; de Carvalho Neto, D.P.; Novak Sydney, A.C.; Letti, L.A.J.; Karp, S.G.; Zevallos Torres, L.A.; Soccol, C.R. Lignocellulosic Biomass: Acid and Alkaline Pretreatments and Their Effects on Biomass Recalcitrance—Conventional Processing and Recent Advances. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 304, 122848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jönsson, L.J.; Martín, C. Pretreatment of Lignocellulose: Formation of Inhibitory by-Products and Strategies for Minimizing Their Effects. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 199, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, E.L.N.; da Silva, T.A.; Pirich, C.L.; Corazza, M.L.; Pereira Ramos, L. Supercritical Fluids: A Promising Technique for Biomass Pretreatment and Fractionation. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, J.R.; Modig, T.; Petersson, A.; Hähn-Hägerdal, B.; Lidén, G.; Gorwa-Grauslund, M.F. Increased Tolerance and Conversion of Inhibitors in Lignocellulosic Hydrolysates by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Chem. Tech. Biotech. 2007, 82, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kululo, W.W.; Habtu, N.G.; Abera, M.K.; Sendekie, Z.B.; Fanta, S.W.; Yemata, T.A. Advances in Various Pretreatment Strategies of Lignocellulosic Substrates for the Production of Bioethanol: A Comprehensive Review. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2025, 7, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trache, D.; Tarchoun, A.F.; Derradji, M.; Hamidon, T.S.; Masruchin, N.; Brosse, N.; Hussin, M.H. Nanocellulose: From Fundamentals to Advanced Applications. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Liu, C.; Liu, Y.; Li, R.; Si, M.; Shi, Y. Preparation of Lignin Nanoparticles via Ultra-Fast Microwave-Assisted Fractionation of Lignocellulose Using Ternary Deep Eutectic Solvents. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2023, 120, 1557–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Qian, Y.; Yang, D.; Qiu, X.; Qin, Y.; Zhou, M. Lignin-Based Nanoparticles: A Review on Their Preparations and Applications. Polymers 2020, 12, 2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez Cabrera, P.A.; Lozano Pérez, A.S.; Guerrero Fajardo, C.A. Innovative Design of a Continuous Ultrasound Bath for Effective Lignocellulosic Biomass Pretreatment Based on a Theorical Method. Inventions 2024, 9, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Q.; Ju, M.; Li, W.; Liu, L.; Chen, Y.; Yang, Q. Pretreatment of Lignocellulosic Biomass with Ionic Liquids and Ionic Liquid-Based Solvent Systems. Molecules 2017, 22, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsuri, A.A.; Md. Jamil, S.N.A.; Abdan, K. Nanocellulose Extraction Using Ionic Liquids: Syntheses, Processes, and Properties. Front. Mater. 2022, 9, 919918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, T.; Xu, Y.; Li, P.; Han, J.; Wu, Z.; Tao, Y.; Yang, Q.-H. A Bio-Derived Sheet-like Porous Carbon with Thin-Layer Pore Walls for Ultrahigh-Power Supercapacitors. Nano Energy 2020, 70, 104531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Singh, J.; Singh, M.K.; Singhal, A.; Thakur, I.S. Investigating the Degradation Process of Kraft Lignin by β-Proteobacterium, Pandoraea Sp. ISTKB. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 15690–15702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koul, B.; Poonia, A.K.; Yadav, D.; Jin, J.-O. Microbe-Mediated Biosynthesis of Nanoparticles: Applications and Future Prospects. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madigal, J.P.T.; Terasaki, M.; Takada, M.; Kajita, S. Synergetic Effect of Fungal Pretreatment and Lignin Modification on Delignification and Saccharification: A Case Study of a Natural Lignin Mutant in Mulberry. Biotechnol. Biofuels Bioprod. 2025, 18, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqi, K.S.; Husen, A. Fabrication of Metal Nanoparticles from Fungi and Metal Salts: Scope and Application. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, P.F.F.; Coelho, M.A.Z.; Marrucho, I.M.J.; Coutinho, J.A.P. Biosurfactants from Yeasts: Characteristics, Production and Application. In Biosurfactants; Sen, R., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 236–249. ISBN 978-1-4419-5979-9. [Google Scholar]

- Matsushika, A.; Inoue, H.; Kodaki, T.; Sawayama, S. Ethanol Production from Xylose in Engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae Strains: Current State and Perspectives. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009, 84, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouro, A.; Cadete, R.M.; Santos, R.O.; Rosa, C.A.; Stambuk, B.U. Xylose and Cellobiose Fermentation by Yeasts Isolated from the Brazilian Biodiversity. BMC Proc. 2014, 8, P202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senatham, S.; Chamduang, T.; Kaewchingduang, Y.; Thammasittirong, A.; Srisodsuk, M.; Elliston, A.; Roberts, I.N.; Waldron, K.W.; Thammasittirong, S.N.R. Enhanced Xylose Fermentation and Hydrolysate Inhibitor Tolerance of Scheffersomyces Shehatae for Efficient Ethanol Production from Non-Detoxified Lignocellulosic Hydrolysate. Springerplus 2016, 5, 1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chilakamarry, C.R.; Mimi Sakinah, A.M.; Zularisam, A.W.; Sirohi, R.; Khilji, I.A.; Ahmad, N.; Pandey, A. Advances in Solid-State Fermentation for Bioconversion of Agricultural Wastes to Value-Added Products: Opportunities and Challenges. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 343, 126065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhania, R.R.; Patel, A.K.; Singh, A.; Haldar, D.; Soam, S.; Chen, C.-W.; Tsai, M.-L.; Dong, C.-D. Consolidated Bioprocessing of Lignocellulosic Biomass: Technological Advances and Challenges. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 354, 127153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banat, I.M.; Franzetti, A.; Gandolfi, I.; Bestetti, G.; Martinotti, M.G.; Fracchia, L.; Smyth, T.J.; Marchant, R. Microbial Biosurfactants Production, Applications and Future Potential. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 87, 427–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcelino, P.R.F.; Peres, G.F.D.; Terán-Hilares, R.; Pagnocca, F.C.; Rosa, C.A.; Lacerda, T.M.; dos Santos, J.C.; da Silva, S.S. Biosurfactants Production by Yeasts Using Sugarcane Bagasse Hemicellulosic Hydrolysate as New Sustainable Alternative for Lignocellulosic Biorefineries. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 129, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Gao, R.; Song, X.; Yuan, X.; Chen, X.; Zhao, Y. Study on the Production of Sophorolipid by Starmerella bombicola Yeast Using Fried Waste Oil Fermentation. Biosci. Rep. 2024, 44, BSR20230345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faria, N.T.; Nascimento, M.F.; Ferreira, F.A.; Esteves, T.; Santos, M.V.; Ferreira, F.C. Substrates of Opposite Polarities and Downstream Processing for Efficient Production of the Biosurfactant Mannosylerythritol Lipids from Moesziomyces spp. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2023, 195, 6132–6149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakur, A.; Niu, Y.; Kuang, H.; Chen, Q. Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles Derived from Mannosylerythritol Lipid and Evaluation of Their Bioactivities. AMB Express 2019, 9, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, P.; Selvaraj, K.; Prabhune, A. Sophorolipids: In Self Assembly and Nanomaterial Synthesis. World J. Pharm. Pharmacuetical Sci. 2013, 2, 1107. [Google Scholar]

- Penfold, J.; Chen, M.; Thomas, R.K.; Dong, C.; Smyth, T.J.P.; Perfumo, A.; Marchant, R.; Banat, I.M.; Stevenson, P.; Parry, A.; et al. Solution Self-Assembly of the Sophorolipid Biosurfactant and Its Mixture with Anionic Surfactant Sodium Dodecyl Benzene Sulfonate. Langmuir 2011, 27, 8867–8877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, A.F.; Banat, I.M.; Giachini, A.J.; Robl, D. Fungal Biosurfactants, from Nature to Biotechnological Product: Bioprospection, Production and Potential Applications. Bioprocess. Biosyst. Eng. 2021, 44, 2003–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, N.d.A.T.; Simões, L.A.; Dias, D.R. Biosurfactants Produced by Yeasts: Fermentation, Screening, Recovery, Purification, Characterization, and Applications. Fermentation 2023, 9, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]