Abstract

Brazil is one of the world’s largest producers of grains and cattle, activities that generate a large amount of organic waste, which has high potential for biogas and methane production. Cattle manure (CM) and industrial waste from corn processing are substrates with significant potential for biogas and methane generation, particularly through the process of anaerobic co-digestion (AcoD). This study aimed to assess the biogas and methane yield, as well as the stability of the AcoD process involving CM and corn grain residues (CG) derived from a grain processing agroindustry, in conjunction with the application of an enzyme complex. The experiment was conducted in plug-flow biodigesters, with a total volume of 28 L, under a semi-continuous feeding regime (OLR = 0.84 g vs. L d−1) at ambient temperature. The findings indicated increases in daily biogas and methane production for AcoD, without the addition of enzymes, of 52.1% and 44.4%, respectively, in comparison to CM mono-digestion. The incorporation of the enzyme complex did not yield beneficial effects, irrespective of the substrate composition. The utilization of enzymes in semi-continuous biodigesters to enhance methane yields necessitates further investigation to achieve favorable outcomes and validate its efficiency.

1. Introduction

Brazilian agribusiness depends on substantial agricultural and livestock production to satisfy both domestic and export demands. While this sector bolsters the country’s economy, it concurrently produces significant quantities of organic waste. The fundamental strategy is to reuse organic matter/biomass to transform the environmental problem into an economic opportunity and a sustainable energy solution [1]. The ongoing energy transition, characterized by the pursuit of cleaner energy sources, employs a strategy that leverages the abundance of biomass for renewable energy generation. Among these sources, biogas emerges as a promising biofuel owing to its potential to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions, minimize adverse environmental impacts, and enhance decarbonization and energy security [2].

Brazil has established itself as one of the largest producers and exporters of corn globally. This industry has experienced continuous growth, driven by demand from animal feed, ethanol production, and the food sector [3]. Among the biomass and residues generated during the harvesting (stalks, leaves) and processing (cobs, straw, damaged grains) stages, corn grain residues (rejected corn) exhibit significant potential for energy conversion due to their composition [4]. While corn cobs and straw possess a high lignocellulosic content [5,6], corn grains contain starch, sugars, proteins, and fibers (hemicellulose), which are more biodegradable compounds [4].

The anaerobic co-digestion (AcoD) technique has been widely used to improve the stability and degradability of substrates. It involves combining different organic wastes with complementary characteristics, promoting synergistic effects [7,8]. The result is improved conditions and efficiency in the anaerobic digestion (AD) process [9]. Cattle manure (CM) is one of the most widely used wastes in AcoD due to the benefits this waste provides, including (i) high buffering power and ability to neutralize acids, (ii) ability to balance the carbon-nitrogen ratio (C/N), as it is rich in N; and (iii) bioavailability of nutrients and microorganisms, which favors rapid adaptation to the environment and anaerobic activity [10,11,12].

Previous studies have shown that anaerobic AcoD of CM and fresh, silage, and dry yellow corn straw [12], maize silage [13], and food waste and corn straw [14] is beneficial for biomethane production and digestion stability in comparison with mono-digestion.

The use of enzymes in AD is another technique that can improve process efficiency and increase methane yields. Considered a biological pretreatment, this technique consists of choosing specific enzymes, such as cellulases and hemicellulases, which can break down complex substrate components, such as cellulose and hemicellulose, into simpler compounds [15,16,17]. As well as speeding up the rate of decomposition of organic matter, the application of enzyme complexes can improve the quality of the digestate, which can then be used as fertilizer. Previous investigations into the application of different enzymes in the AD of corn straw have obtained an increase in biomethane production of 24% (laccase, batch reactor) [18], 11.7% and 27.9% (cellulase and amylase, respectively, batch reactor) [19], and 110.76% in the AcoD with CM (amylase and protease, batch reactor) [20], when compared to the untreated substrate. Results can vary widely due to the complexity and interaction of multiple factors, such as operating conditions, microbial interactions, application method, enzyme degradation and stability, etc. [21].

By combining waste from different sources and biological pretreatments, it is possible to maximize the efficiency of the process and contribute to a more sustainable management of agricultural and livestock waste. Thus, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the yield and quality of biogas, as well as the stability of the anaerobic AcoD process of CM with corn grain waste (CG), generated in a grain processing agro-industry, associated with the application of an enzyme complex.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The study was conducted at the Laboratory of Biodigestion and Waste Management, on the main campus at Anápolis Headquarters of Exact and Technological Sciences (CET), State University of Goiás (UEG), between August and November 2021. According to Köppen, the local climate is classified as Aw type, which stands for rainy (October–March) and dry (April–September) seasons, with annual averages of 22.4 °C (temperature) and 1586 mm (rainfall).

2.2. Inoculum and Feedstock

The inoculum used in this experiment was taken from a biodigester in a semi-continuous system, which treated diluted dairy cattle manure (without the solid fraction) and had stable biogas production. The raw materials were dairy cattle manure (CM) and industrial corn grain residues (CG), collected from a dairy farm and a food industry, respectively. CM was collected weekly in the property’s compost barn and stored in a closed container at room temperature.

Industrial CG waste was first dried naturally to remove excess moisture for four days at average temperatures of 25 to 28 °C. Next, it was ground using a knife mill (Marconi MA580, Piracicaba 13405-455, Brazil) and passed through a 4 mm sieve. The material was put into LDPE (low-density polyethene) bags and kept in the freezer at −18 °C during the entire experiment.

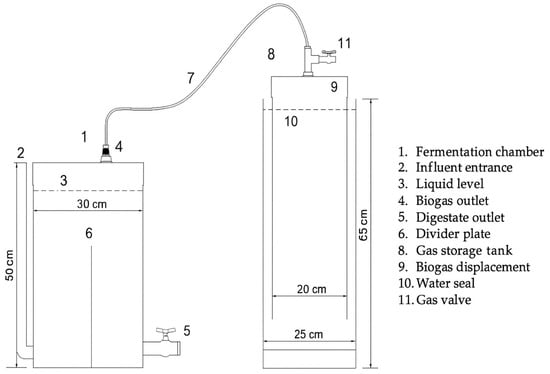

2.3. Semi-Continuous Biodigester Description

At a laboratory scale, the semi-continuous biodigesters were made up of hermetically sealed polyvinyl chloride (PVC) pipes with two distinct parts: the container with the fermenting material (fermentation chamber) and the gasometer (Figure 1). Semi-continuous biodigesters have an entrance for the load and an exit for the digestate, plus a hose to conduct the biogas to the gasometer. The gasometer consisted of two PVC tubes; one external pipe with a 25 cm diameter was filled with water, and a second pipe with a 20 cm diameter was submerged in water to allow displacement by the gas produced in the fermentation chamber. A graduated ruler was fixed to the outside of the gasometer to measure the displacement of the tube.

Figure 1.

Schematic cross-sectional design of the semi-continuous biodigester [22].

2.4. Treatment Descriptions

The experiment was set up in a completely random design, using a 2 x 2 (substrate vs. enzyme) factorial scheme with 4 replicates, making a total of 16 experimental plots. The treatments included different combinations of cattle manure (CM) and industrial corn grain waste (CG), either with or without the addition of digestive enzymes (E), according to their volatile solids (VS) content. The proportions were as follows: CM (100% CM without enzyme); CM + E (100% CM with enzyme); CM + CG (70% CM + 30% CG without enzyme); and CM + CG + E (70% CM + 30% CG with enzyme).

The experiment was performed using a 28-day hydraulic retention time (HRT) and a 28-L biodigester volume, with daily loads of 1 L. The biodigesters were started by adding 28 L of a mixture of CM and biodigester inoculum at a ratio of 1:4. For the next 28 days, CoD with CM was performed, followed by CoD of treatments for 56 days. CM and CG (≤4 mm) were separately diluted with water and homogenized to reach a total solids content of about 3% (OLR = 0.80–0.89 g vs. L d−1). The diluted CM was then filtered through a 4 mm mesh sieve to remove fibrous material. All daily loads of the treatments were placed in 1-L plastic bottles. Then, the bottles destined for treatments with enzyme addition were separated from the others to apply the enzymatic complex. The characteristics of the materials used in the CoD are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characterization of the substrates used in the semi-continuous biodigester experiment.

Covered lagoon biodigesters are frequently used in Brazil to treat livestock waste. However, this model faces limitations, such as a low volumetric organic load (0.3–0.5 kg SV mreactor −3 d−1) and a high hydraulic retention time (30–45 days). Implementing preliminary solid separation techniques can boost methane production capacity and reduce the treatment plant size [23]. Typically, the solid fraction of manure undergoes composting.

The enzyme complex used in this study came from a private company and included cellulase (2 million IU per kilogram), xylanase (100,000 IU per kilogram), pectinase (1 million IU per kilogram), and protease (5 million IU per kilogram), plus probiotics and natural catalysts.

After activating the complex, as recommended by the manufacturer, we added 1 mL of it to each liter of the substrate. The substrate was neutral, with a pH between 7.0 and 7.5, when the complex was applied. The applications were made every day for 56 days, just before the daily loads. The substrate composition of each treatment evaluated is presented at Table 2.

The activated complex was stored and refrigerated in a B.O.D. incubator at 8 ± 2 °C and 70 ± 5% RH.

Table 2.

Substrate composition (daily load) of each treatment evaluated.

Table 2.

Substrate composition (daily load) of each treatment evaluated.

| Treatments | Substrate Composition | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CM (g) | CG (g) | Water (g) | Enzyme (mL) | |

| CM | 163 | - | 837 | - |

| CM + E | 163 | - | 837 | 1 |

| CM + CG | 114 | 12 | 874 | - |

| CM + CG + E | 114 | 12 | 874 | 1 |

CM: 100% CM without enzyme; CM + E: 100% CM with enzyme; CM + CG: 70% CM and 30% CG without enzyme; and CM + CG + E: 70% CM and 30% CG with enzyme.

2.5. Laboratory Analyses

CM and CG were subjected to bromatological analysis for the determination of CP, NSC, EE, MM, CF, NDF, and ADF, following a method established by Instituto Adolfo Lutz [24]. The biodigester influent and effluent were analyzed for TS, VS, pH, and alkalinity [25]. Moreover, TOC and KTN were quantified by dividing vs. percentage by 1.8 [26] and by the micro-Kjeldahl method [27], respectively. These parameters were used to determine the C/N ratio. Finally, we analyzed the chemical composition of influent and effluent [24]. The levels of N (nitrogen), P (phosphorus), and K (potassium) were determined only for the biofertilizer (influent and effluent).

2.6. Biogas Monitoring

Daily biogas production (DBP) was measured by the vertical displacement of gasometers, which had an internal cross-sectional area of 0.02956 square meters. Temperature, biogas volumes, and environmental conditions were monitored throughout the experimental period. The correction of biogas volume for the conditions at 1 atm and 20 °C was carried out by means of Equation (1), resulting from the combination of Boyle’s and Gay-Lussac’s laws.

where

V0—Corrected volume of the biogas, m3;

P0—Corrected pressure of the biogas, 10,322.72 mmH2O;

T0—Corrected temperature of the biogas, 293.15 Kelvin (K);

V1—Volume of the gas in the gasometer;

P1—Biogas pressure at the time of reading, in mm H2O;

T1—Biogas temperature at the time of reading, in K.

The generated gases were analyzed on a gas chromatograph (PerkinElmer, Clarus 580 model, Santana de Parnaíba 06528-001, Brazil) equipped with a methane analyzer (400 °C) and series-coupled FID (250 °C) and TCD (200 °C) detectors. The equipment was made available by the laboratory of Materials and Catalysis of the Federal Institute of Education, Science and Technology of Goiás (IFG), at Goiânia Campus.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

The data underwent variance analysis using the F test. When significant, the means were compared by the Tukey test at 5% significance. The assumptions of variance homogeneity and residual normality were checked. The statistical analyses were performed using the SISVAR 5.6 software [28].

3. Results and Discussion

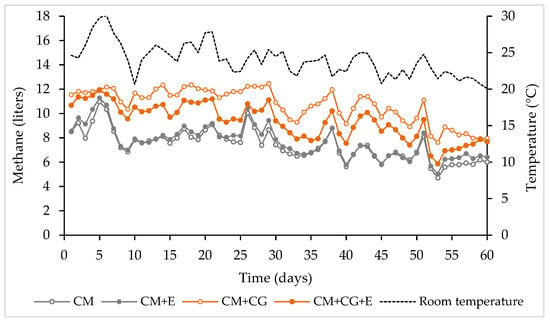

Figure 2 displays the daily average biogas production for all treatments and the variation in the temperature during the experimental period. Daily enzyme additions were made from day 6 to 60.

Figure 2.

Variation in daily biogas production and temperature during the experimental period. CM: 100% CM without enzyme; CM + E: 100% CM with enzyme; CM + CG: 70% CM and 30% CG without enzyme; and CM + CG + E: 70% CM and 30% CG with enzyme.

The average temperature of the environment during the experimental period was 24.1 °C, with a minimum of 20.1 °C and a maximum of 30.1 °C, which remained within the mesophilic range (20 to 40 °C) [29].

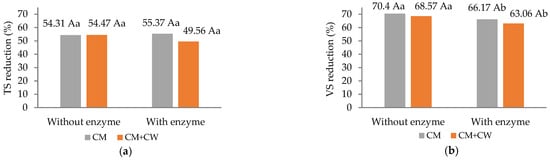

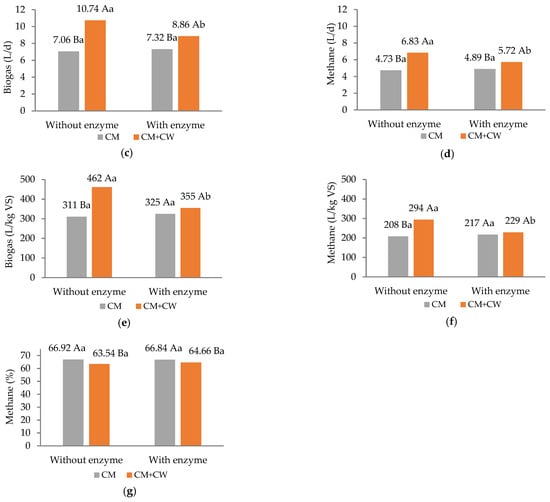

It was observed that the interaction between the factors (p < 0.05) affected the variables biogas and methane yields, as well as effluent alkalinity. A main effect of the enzyme (p < 0.05) was found for the variable volatile solids (VS) reduction, and a main effect of the proportion (p < 0.05) was observed for the methane content in biogas (Tables S1 and S2; Supplementary Materials).

When comparing mono-digestion (CM) and co-digestion (CM + CW), the inclusion of CG had a beneficial influence, promoting higher energy recovery from the substrate, which resulted in significantly greater (p < 0.05) biogas and methane yields (L/d and L/kg VS) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Total solids reduction (a), volatile solids reduction (b), daily biogas production (c), daily methane production (d), specific biogas yield (e), specific methane yield and (f) methane content in biogas (g). Different capital letters represent statistical differences within the factor, without and with CG. Different lowercase letters indicate statistical differences within the factor, without and with enzymes (Tukey’s test, p < 0.05).

The increases in daily biogas and methane production for CM + CG were 52.1% and 44.4%, respectively, compared to mono-digestion (Figure 3c,d). AcoD can enhance biogas and methane yields, particularly when one of the substrates serves as a source of labile carbon (e.g., corn residues or carbohydrate-rich material) while the other supplies mineral supplementation and promotes a balanced environment for optimal microbial performance (e.g., cattle or swine manure) [30]. In an earlier study by Zhang et al. [12], the addition of cow dung liquid (CoD with corn straw) as a nitrogen source adjusted the C/N ratio in the biodigester and increased the diversity of the microbial communities present, thus improving the microbial habitat and maximizing biogas production. The higher methane yield of CoD is attributed to more easily biodegradable compositions of CG (sugars and starch) in comparison with CM (lignocellulosic fibers). In the study conducted by Eliasson et al. [31], an improvement in the degradation of fibrous materials present in CM was reported as a result of CoD with potato starch. The authors highlighted the priming effect, where easily degradable substrates boost microbial activity and the production of hydrolytic enzymes, ultimately increasing the efficiency of anaerobic digestion (AD) and optimizing biogas yield from CM.

The inclusion of the enzyme in the mono-digestion of CM showed no influence on the evaluated parameters. In contrast, for CoD, a negative effect was observed due to the lower (p < 0.05) biogas and methane yields achieved in the CM + CG + E treatment (229 L/kg VSadded) compared to CM + CG (294 L/kg VSadded). The application of the enzyme resulted in decreases of 17.5% and 16.2% in daily biogas and methane production (1.88 and 1.11 L d−1, respectively). These findings diverge from those reported by Fernandes et al. [32], who assessed the direct application of 1 mL of a bioremediator (enzymatic complex) in the CoD of CM and commercial corn starch (plug-flow biodigester). The authors observed that enzyme addition enhanced biogas production in CM mono-digestion; however, it had no effect on the CoD tested.

Substrate proportion influenced methane content in the biogas, whereas enzyme addition had no effect on this parameter (Figure 3g). As reported in the literature, certain substrate mixtures may reduce methane content in biogas. Nevertheless, studies with brewery residues [22] demonstrated that higher biogas volumes could be obtained from CoD compared to mono-digestion, compensating for the final volume of methane produced. Despite this, CH4 concentrations in all treatments remained above 63.3%, indicating potential for energy utilization [33].

The methane yields obtained in this study for mono-digestion (173.3 L kg VS−1) and CoD (298.8 L kg VS−1) were close to the averages reported in previous studies with different organic residues. Zarkadas et al. [34] reported yields of 207 and 290 L/kg VSadded for CM/pasteurized food waste (100/0 and 70/30, on a VS basis, respectively). Akamine et al. [22], using plug-flow reactors, reported yields of 247.5 and 289.3 L/kg VSadded for CM/brewery waste (100/0 and 68/32, on a VS basis, respectively). Zhang et al. [14], using CSTR reactors (OLR = 2 g VS/L/d), reported yields of 244.3, 324.8, and 257.1 L/kg VSadded for CM mono-digestion, CM + food waste (3:1 proportion), and CM + corn straw (3:1 proportion), respectively.

The physical and chemical characteristics of influents and effluents from the evaluated treatments are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Characterization of the influent and effluent from different treatments.

When commercial enzymatic products are applied to substrates subjected to AD, a higher proportion of organic matter conversion is expected, thereby enhancing the efficiency of the hydrolytic phase [15]. Consequently, the products generated in this phase must be utilized in subsequent stages (acetogenesis, acidogenesis, and methanogenesis). However, when not consumed, these intermediates may cause an imbalance in the microbial community, potentially impairing the degradation of the formed constituents [17]. Certainly, the action of the enzymatic complex in the CM treatment may have been attenuated by the recalcitrance of the components present in the manure, which consists mainly of proteins and lignocellulosic biomass not digested by the animal [17].

The CM + CG + E treatment exhibited more pronounced reductions in some substrate constituents. The inclusion of the enzymatic complex may have promoted greater reductions in crude protein (9.56%), crude fiber (66.53%), NDF (47.41%), and ether extract (16.67%). Nevertheless, the intermediates formed from the breakdown of these compounds were not converted into biogas. Therefore, under the conditions adopted in the present study, the use of enzymes in the CoD of CM + CG did not enhance the process in terms of increasing the energy yield of these residues. However, the reduction in these constituents observed in the digestate is associated with higher degradability and stability, which can provide agronomic benefits when applied to soil.

Differences in NDF reduction were not observed (43.59 vs. 47.41%); however, an expressive reduction in ADF was observed at the CM + CG treatment when compared to the CM + CG + E (32.57 vs. 6.84%). This result represents an important point for the process interpretation. While the NDF is composed of hemicellulose, cellulose and lignin, the ADF is composed essentially of cellulose and lignin. Considering that cellulose has a substantially superior potential for conversion into methane than hemicellulose [35], the greater consumption difference in ADF (in other words, cellulose, for obvious reasons) led to a difference in CH4 production, despite the fact that the addition of enzymes demonstrated more efficiency in removing hemicellulose.

Furthermore, reductions in hemicellulose (84.56% para CM + CG + E) strengthen the hypothesis of the enzymatic action being more pronounced on easily accessible fractions. The cellulosic fraction remained protected by the lignified structure, as described by Li et al. [35], who emphasize the physical and chemical barrier imposed by lignin to cellulose hydrolysis. Thus, even with the partial degradation of hemicellulose, the system may have presented an imbalance amongst hydrolysis and methanogenesis steps, resulting in a possible accumulation of intermediates and produced CH4. Therefore, the observed removal of fibrous and hemicellulosic compounds indicates that part of the cellulose was decomposed, but methanogenesis was not the destination of the hydrolysis products. These findings reinforce the hypothesis that the addition of enzymes, even though increasing the structural degradation of the biomass, does not necessarily guarantee improvements in the final conversion into biogas, especially under psychrophile conditions and with possible limitations in the adaptation of the bacterial community.

Among the enzymes contained in the complex, (i) protease acts on proteins, forming peptides and amino acids; (ii) xylanase catalyzes the degradation of xylan, the main hemicellulose polymer (NDF-ADF), into oligosaccharides and monosaccharides; (iii) cellulase hydrolyzes cellulose into glucose; and (iv) pectinase degrades pectin into oligosaccharides, phenols, and organic acids [36]. Pectinase may aid in starch release by disrupting cell walls and the polysaccharide matrix in corn grains, facilitating the formation of fermentable sugars during enzymatic hydrolysis.

Previous investigations have shown that the methane potential of cellulose is greater than that of hemicellulose. However, hemicellulose is generally hydrolyzed more rapidly than cellulose, whereas lignin exhibits high resistance to degradation [37]. All treatments displayed high hemicellulose reductions compared with the other substrate constituents. Lignin is mainly degraded under aerobic conditions, while under low oxygen conditions, such as in the anaerobic digestion process, it may persist for long periods. Furthermore, lignin can form a barrier against hydrolytic enzymes when it is present in higher proportions in the substrate, leading to less effective conversions of organic matter into biogas [35].

The results obtained in this semi-continuous biodigester assay did not match the outcomes reported in the literature from batch assays, in which yields were maximized with enzyme addition [18,19,20,38]. In the study conducted by Muller et al. [38] on the CoD of CM and corn silage in semi-continuous reactors, daily enzyme addition did not increase biogas yield, and higher dosages resulted in reduced biogas production (13% and 36% lower than the reference).

The unsatisfactory outcome of enzymatic complex application may be attributed to the following reasons: (i) inadequate hydrolysis of complex organic matter, resulting in the formation of intermediates that increased alkalinity but were not efficiently converted into methane; (ii) premature inactivation and/or degradation of enzymes due to reactor conditions, such as temperature fluctuations and/or the presence of inhibitors (intermediates), since enzymes require specific conditions to function optimally; and/or (iii) introduced enzymes interfered with native microbial communities, disrupting the microbiological balance and possibly inhibiting beneficial microorganisms required for other stages of the AD process.

Previous studies by Muller et al. [38] and Wang et al. [20] also reported negative results with protease application. The authors highlighted several explanations: (i) proteases degrade certain essential enzymes, such as hydrolases, which are important in the hydrolytic phase, or enzymes involved in acidogenesis and methanogenesis; (ii) proteases attack the surface of microorganisms; and (iii) proteases promote the accumulation of intermediate products derived from protein degradation, such as phenyl acetate and propionate, leading to increased VFA concentrations and consequent inhibition of microorganisms.

It can be assumed that the enzymatic compound used was inhibited in the biodigester, particularly in the CM + E treatment, which could be further investigated in future studies, for example, by measuring enzymatic activity and biogas production time after enzyme application. Consequently, the results provide a basis for guiding future discussions on the application of enzymatic compounds at higher dosages; the efficacy of enzymes in carbohydrate-rich substrates; the structure of microbial communities in mono- and co-digestion with enzyme addition; and other studies addressing the technical and economic feasibility of additive use in AD.

Table 4 shows the results of pH, total alkalinity (TA), partial alkalinity (PA), intermediate alkalinity (IA) (in mg CaCO3 L−1), and their ratio (IA/PA) for influents and effluents during the experimental period. The parameters PA, IA, and TA showed significant interactions (p < 0.05) in effluents.

Table 4.

Partial alkalinity (PA), intermediate alkalinity (IA), total alkalinity (TA), and the ratio AI/AP in substrates (influent and effluent) from different treatments (substrates with and without enzyme addition).

Total alkalinity (TA) represents the overall capacity of the system to resist pH fluctuations, thereby preventing inhibition by acidification. TA is the sum of partial alkalinity (PA) and intermediate alkalinity (IA), where PA corresponds to alkalinity from carbonates and bicarbonates, and IA is due to volatile fatty acids (VFAs). At concentrations between 2.5 g L−1 and 5.0 g L−1, bicarbonate exerts a strong buffering effect [39]. Therefore, the IA values obtained in this study indicate good stability throughout the evaluation period (3455.0–4337.5 mg CaCO3 L−1, effluent). The optimal IA/PA ratio for stable AD performance is between 0.3 and 0.4, while values below 0.3 may indicate underloading of the reactor [39]. The values obtained for the effluents (0.14–0.18) suggest that the organic loading rate could have been increased, and consequently, a more effective response might have been achieved with the addition of the enzymatic complex. It is valid to consider that, due to the limitations of the biodigester model, low organic loads were applied, ensuring the safe operation of full-scale biodigesters (covered lagoon) without the risk of overloading and acidification.

In the influent, the CM + E treatment presented higher (p < 0.05) partial alkalinity compared to CM + CG + E. This difference is likely due to the replacement of part of CM with CG (70/30), since corn provides a higher proportion of readily degradable compounds to the substrate, thereby increasing acid concentrations in the system. For the same reason, total alkalinity values observed in CM and CM + E (3415.0 and 3690.0) were higher (p < 0.05) than those of CM + CG and CM + CG + E (3165.0 and 3285.0), respectively.

Evidence suggests that cattle manure plays a crucial role in maintaining buffering capacity during anaerobic CoD with various materials, such as food waste [40], corn waste, and agricultural residues [41].

The CM + E treatment also showed the highest values (p < 0.05) of PA, IA, and TA in the effluent. This result may indicate a system requirement to increase alkalinity due to the formation of long-chain organic acids derived from the action of the enzymatic complex. When organic acid production is not matched by the same consumption rate during methanogenesis, alkalinity may increase without a corresponding rise in biogas production.

4. Conclusions

The combination of cattle manure with corn grain waste in anaerobic co-digestion leads to higher daily biogas production (52.12%) and improved specific yields of methane (41.35%) and biogas (48.55%) compared to just using cattle manure (mono-digestion).

Adding enzymes to the substrate, whether it was just cattle manure or a combination of cattle manure and corn grain waste, did not increase biogas production. It is possible that the dose of enzymes used was not high enough to have a noticeable effect.

The technique of enzyme application in semi-continuous biodigesters, aimed at increasing biogas production, still requires further investigation in order to achieve positive results and confirm its efficiency. Future studies are recommended to include the measurement of enzymatic activity. Consequently, the findings provide a basis for guiding further discussions on the application of enzymatic compounds at higher dosages and the effectiveness of enzymes in carbohydrate-rich substrates, as well as supporting other studies that may address the technical and economic feasibility of additive use in anaerobic digestion and co-digestion.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/fermentation11120696/s1, Table S1: Summary of the analysis of variance (p-value) for the variables, specific biogas and methane production and reductions in total solids (TS) and volatile solids (VS); Table S2: Summary of the analysis of variance (p-value) for partial, intermediate and total alkalinity in the influent and effluent of the treatments studied.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.P.; methodology, R.P., L.A.A. and S.B.d.O.; software, L.M.C. and L.A.A.; validation, R.P. and S.B.d.O.; formal analysis, L.M.C., K.D.d.S. and F.F.C.; investigation, L.M.C., K.D.d.S. and F.F.C.; resources, R.P. and S.B.d.O.; data curation, L.M.C., R.P. and L.A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, L.M.C. and L.A.A.; writing—review and editing, R.P., L.A.A., L.M.C., S.R.R.D.; visualization, L.A.A.; supervision, R.P.; project administration, L.M.C.; funding acquisition, R.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC used the Financial Resource from the PrP/UEG PRÓ-PROGRAMAS No. 01/2024; Commitment Agreement No. 16/2024; SEI Process No. 202400020011306 of the Stricto sensu Postgraduate Program in Agricultural Engineering of the State University of Goiás.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brasil (CAPES)—Finance Code 001.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mendes, F.B.; Volpi, M.P.C.; da Silva Clementino, W.; Albarracin, L.T.; de Souza Moraes, B. An Overview of the Integrated Biogas Production through Agro-Industrial and Livestock Residues in the Brazilian São Paulo State. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Energy Environ. 2023, 12, e494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Mahur, B.K.; Izrayeel, A.M.D.; Ahuja, A.; Rastogi, V.K. Biomass Conversion of Agricultural Waste Residues for Different Applications: A Comprehensive Review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 73622–73647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guimarães, L.J.M. Dia Nacional Do Milho—A Importância Do Milho Para o Agronegócio Brasileiro. Embrapa Milho e Sorgo. Available online: https://www.embrapa.br/busca-de-noticias/-/noticia/89583335/artigo-dia-nacional-do-milho---a-importancia-do-milho-para-o-agronegocio-brasileiro (accessed on 18 May 2024).

- Allesina, G.; Pedrazzi, S.; Guidetti, L.; Tartarini, P. Modeling of Coupling Gasification and Anaerobic Digestion Processes for Maize Bioenergy Conversion. Biomass Bioenergy 2015, 81, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, F.B.; Lima, B.V.d.M.; Volpi, M.P.C.; Albarracin, L.T.; Lamparelli, R.A.C.; Moraes, B.d.S. Brazilian Agricultural and Livestock Substrates Used in Co-Digestion for Energy Purposes: Composition Analysis and Valuation Aspects. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefining 2023, 17, 682–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, D.J.C.; Machado, A.V.; Vilarinho, M.C.L.G. Availability and Suitability of Agroindustrial Residues as Feedstock for Cellulose-Based Materials: Brazil Case Study. Waste Biomass Valorization 2019, 10, 2863–2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, Y.; Khoshnevisan, B.; Duan, N. Meta-Analysis of Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Livestock Manure in Last Decade: Identification of Synergistic Effect and Optimization Synergy Range. Appl. Energy 2021, 282, 116128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnane, I.; Taoumi, H.; Elouahabi, K.; Lahrech, K.; Oulmekki, A. Valorization of Crop Residues and Animal Wastes: Anaerobic Co-Digestion Technology. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, X.; Xing, W.; Li, R.; Yang, T.; Yao, N.; Lv, D. Links between Synergistic Effects and Microbial Community Characteristics of Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Food Waste, Cattle Manure and Corn Straw. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 329, 124919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadam, R.; Jo, S.; Lee, J.; Khanthong, K.; Jang, H.; Park, J. A Review on the Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Livestock Manures in the Context of Sustainable Waste Management. Energies 2024, 17, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufaner, F.; Avşar, Y. Effects of Co-Substrate on Biogas Production from Cattle Manure: A Review. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 13, 2303–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhao, H.; Yu, H.; Chen, D.; Li, X.; Wang, W.; Piao, R.; Cui, Z. Evaluation of Biogas Production Performance and Archaeal Microbial Dynamics of Corn Straw during Anaerobic Co-Digestion with Cattle Manure Liquid. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 26, 739–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varol, A.; Ugurlu, A. Comparative Evaluation of Biogas Production from Dairy Manure and Co-Digestion with Maize Silage by CSTR and New Anaerobic Hybrid Reactor. Eng. Life Sci. 2017, 17, 402–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Kong, T.; Xing, W.; Li, R.; Yang, T.; Yao, N.; Lv, D. Links between Carbon/Nitrogen Ratio, Synergy and Microbial Characteristics of Long-Term Semi-Continuous Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Food Waste, Cattle Manure and Corn Straw. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 343, 126094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-Güiza, M.S.; Vila, J.; Mata-Alvarez, J.; Chimenos, J.M.; Astals, S. The Role of Additives on Anaerobic Digestion: A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 58, 1486–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, Z.; He, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Zheng, Z.; Wang, S.; Xu, J.; Cai, Y.; Ying, H. A Comprehensive Review of the Strategies to Improve Anaerobic Digestion: Their Mechanism and Digestion Performance. Methane 2024, 3, 227–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brémond, U.; de Buyer, R.; Steyer, J.P.; Bernet, N.; Carrere, H. Biological Pretreatments of Biomass for Improving Biogas Production: An Overview from Lab Scale to Full-Scale. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 90, 583–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroyen, M.; Vervaeren, H.; Van Hulle, S.W.H.; Raes, K. Impact of Enzymatic Pretreatment on Corn Stover Degradation and Biogas Production. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 173, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cheng, S.; Li, Z.; Men, Y.; Wu, J. Impacts of Cellulase and Amylase on Enzymatic Hydrolysis and Methane Production in the Anaerobic Digestion of Corn Straw. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, Z.; Zhou, X.; Wang, Q.; Wu, Y.; Saino, M.; Bai, X. Study on the Bio-Methane Yield and Microbial Community Structure in Enzyme Enhanced Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Cow Manure and Corn Straw. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 219, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weide, T.; Baquero, C.D.; Schomaker, M.; Brügging, E.; Wetter, C. Effects of Enzyme Addition on Biogas and Methane Yields in the Batch Anaerobic Digestion of Agricultural Waste (Silage, Straw, and Animal Manure). Biomass Bioenergy 2020, 132, 105442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akamine, L.A.; Passini, R.; Sousa, J.A.S.; Fernandes, A.; de Moraes, M.J. Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Cattle Manure and Brewer’s Residual Yeast: Process Stability and Methane and Hydrogen Sulfide Production. Fermentation 2023, 9, 993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, A.C.d.; Steinmetz, R.L.R.; Kunz, A. Os Biodigestores. In Fundamentos da Digestão Anaeróbia, Purificação do Biogás, Uso e Tratamento do Digestato; Kunz, A., Steinmetz, R.L.R., Amaral, A.C.d., Eds.; Sbera, Embrapa Suínos e Aves: Concórdia, Brazil, 2022; pp. 43–70. [Google Scholar]

- IAL. Métodos Físico-Químicos Para Análise de Alimentos; Instituto Adolfo Lutz: São Paulo, Brazil, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- APHA. Standard Methods for Examinations of Water and Wastewater, 21st ed.; American Water Works Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Carmo, D.L.d.; Silva, C.A. Métodos de Quantificação de Carbono e Matéria Orgânica Em Resíduos Orgânicos. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Do Solo 2012, 36, 1211–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IAL. Métodos Químicos e Físicos Para Análises de Alimentos; Instituto Adolfo Lutz: São Paulo, Brazil, 1985; Volume 121. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, D. Sisvar: A Computer Statistical Analysis System. Ciênc. Agrotecnol. 2014, 35, 1039–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernicharo, C.A.d.L. Anaerobic Reactors: Biological Wastewater Treatment Series, 1st ed.; IWA Publishing: London, UK, 2007; Volume 4, ISBN 9781843391647. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, G.; Ndegwa, P.; Harrison, J.H.; Chen, Y. Methane Yields during Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Animal Manure with Other Feedstocks: A Meta-Analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 728, 138224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eliasson, K.A.; Singh, A.; Isaksson, S.; Schnürer, A. Co-Substrate Composition is Critical for Enrichment of Functional Key Species and for Process Efficiency during Biogas Production from Cattle Manure. Microb. Biotechnol. 2023, 16, 350–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, A.; Montoro, S.B.; Akamine, L.A.; Branco, P.M.P.; Sousa, J.A.S.; Lucas Júnior, J.d. Viabilidade Técnica e Econômica de Aditivos in Situ Na Digestão Anaeróbia de Dejetos de Bovinos. Rev. Ibero-Am. Ciênc. Ambient. 2021, 12, 530–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deublein, D.; Steinhauser, A. Gas Preparation. In Biogas from Waste and Renewable Resources; Deublein, D., Steinhauser, A., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 333–355. ISBN 978-3-527-31841-4. [Google Scholar]

- Zarkadas, I.S.; Sofikiti, A.S.; Voudrias, E.A.; Pilidis, G.A. Thermophilic Anaerobic Digestion of Pasteurised Food Wastes and Dairy Cattle Manure in Batch and Large Volume Laboratory Digesters: Focussing on Mixing Ratios. Renew. Energy 2015, 80, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Khalid, H.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, R.; Liu, G.; Chen, C.; Thorin, E. Methane Production through Anaerobic Digestion: Participation and Digestion Characteristics of Cellulose, Hemicellulose and Lignin. Appl. Energy 2018, 226, 1219–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharathiraja, B.; Sudharsanaa, T.; Bharghavi, A.; Jayamuthunagai, J.; Praveenkumar, R. Biohydrogen and Biogas—An Overview on Feedstocks and Enhancement Process. Fuel 2016, 185, 810–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyi-Loh, C.E.; Lues, R. Anaerobic Digestion of Lignocellulosic Biomass: Substrate Characteristics (Challenge) and Innovation. Fermentation 2023, 9, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, L.; Kretzschmar, J.; Pröter, J.; Liebetrau, J.; Nelles, M.; Scholwin, F. Does the Addition of Proteases Affect the Biogas Yield from Organic Material in Anaerobic Digestion? Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 203, 267–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, A.C.d.; Steinmetz, R.L.R.; Kunz, A. O Processo de Biodigestão. In Fundamentos da Digestão Anaeróbia, Purificação do Biogás, Uso e Tratamento do Digestato; Kunz, A., Steinmetz, R.L.R., Amaral, A.C.d., Eds.; Sbera, Embrapa Suínos e Aves: Concórdia, Brazil, 2022; pp. 15–28. ISBN 978-65-88155-02-8. [Google Scholar]

- Akhiar, A.; Battimelli, A.; Torrijos, M.; Carrere, H. Comprehensive Characterization of the Liquid Fraction of Digestates from Full-Scale Anaerobic Co-Digestion. Waste Manag. 2017, 59, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Bi, G.; Liu, X.; Yu, Q.; Li, D.; Yuan, H.; Chen, Y.; Xie, J. Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Sugarcane Leaves, Cow Dung and Food Waste: Focus on Methane Yield and Synergistic Effects. Fermentation 2022, 8, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).