Use of Pichia manshurica as a Starter Culture for Spontaneous Cocoa Fermentation in Southern Bahia, Brazil

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Yeast Reactivation

2.2. Enzyme Production Evaluation

2.3. Assessment of Resistance to Stress Conditions

2.4. Evaluation of the Cytotoxicity of Pichia manshurica

2.5. Yeast Inoculum

2.5.1. Preparation of the Inoculum

2.5.2. Fermentation Box Inoculation

2.5.3. pH Analysis

2.5.4. Assessment of Almond Cut Quality

2.5.5. Assessment of Microbiological Quality of Almonds

3. Results and Discussion

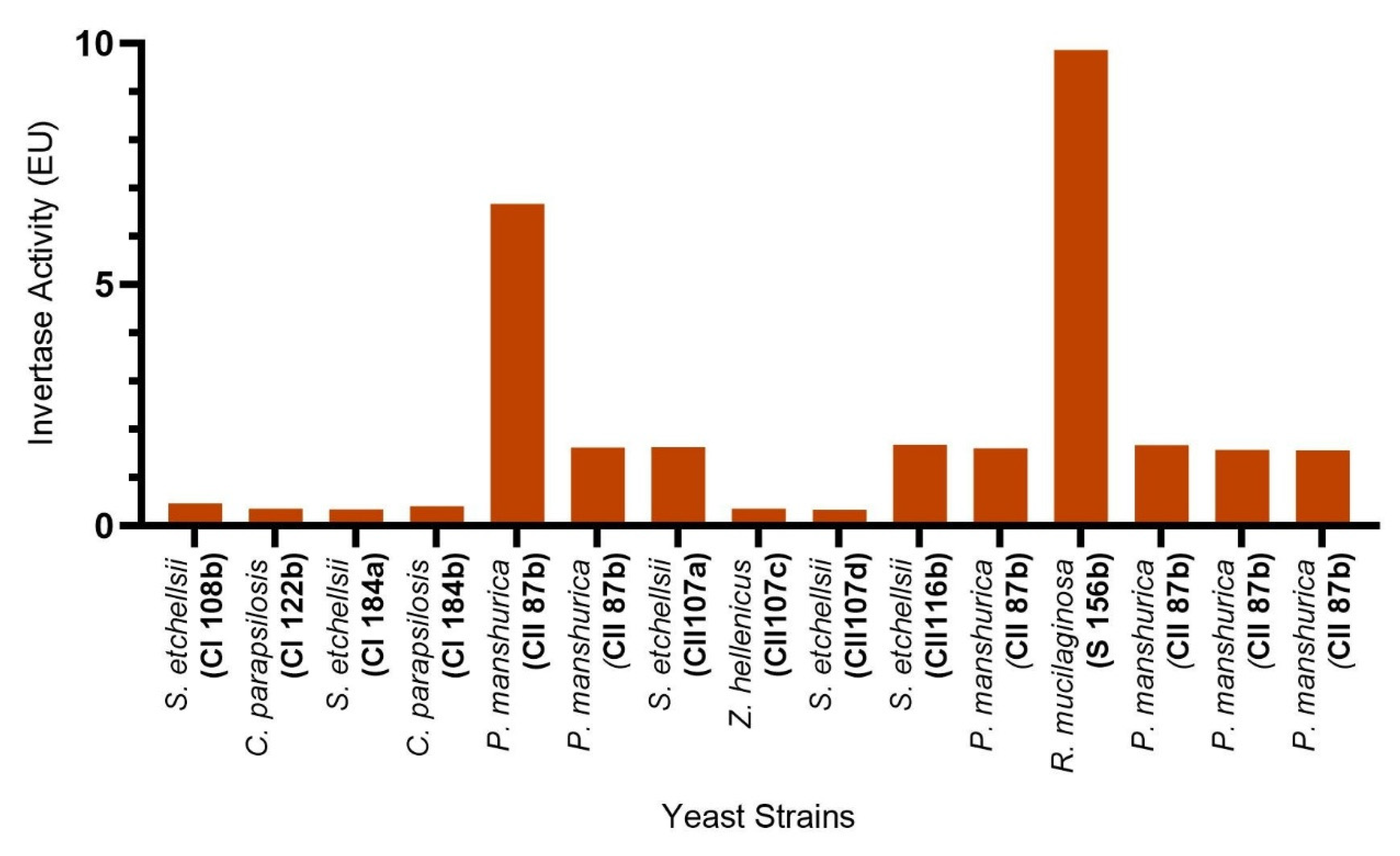

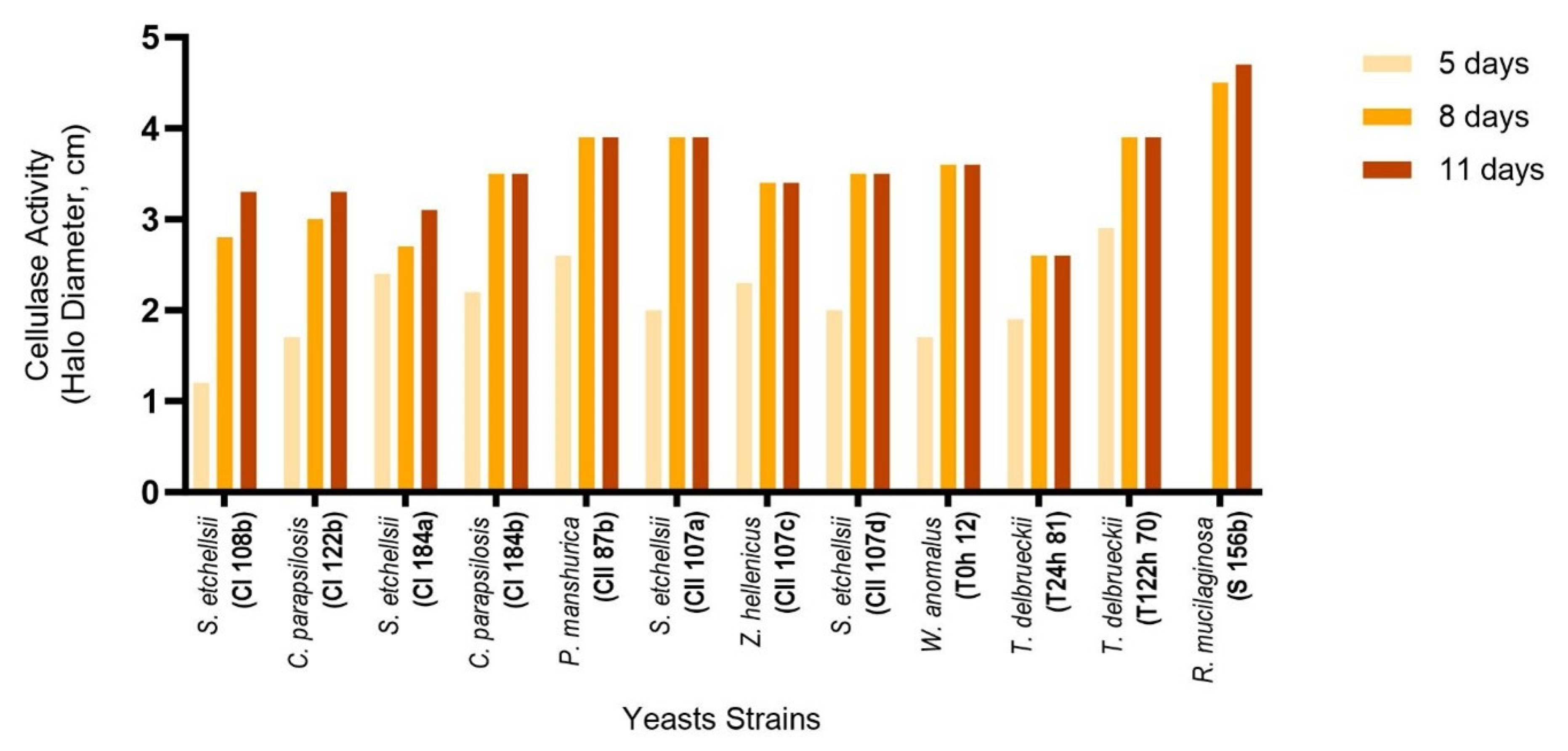

3.1. Enzyme Production

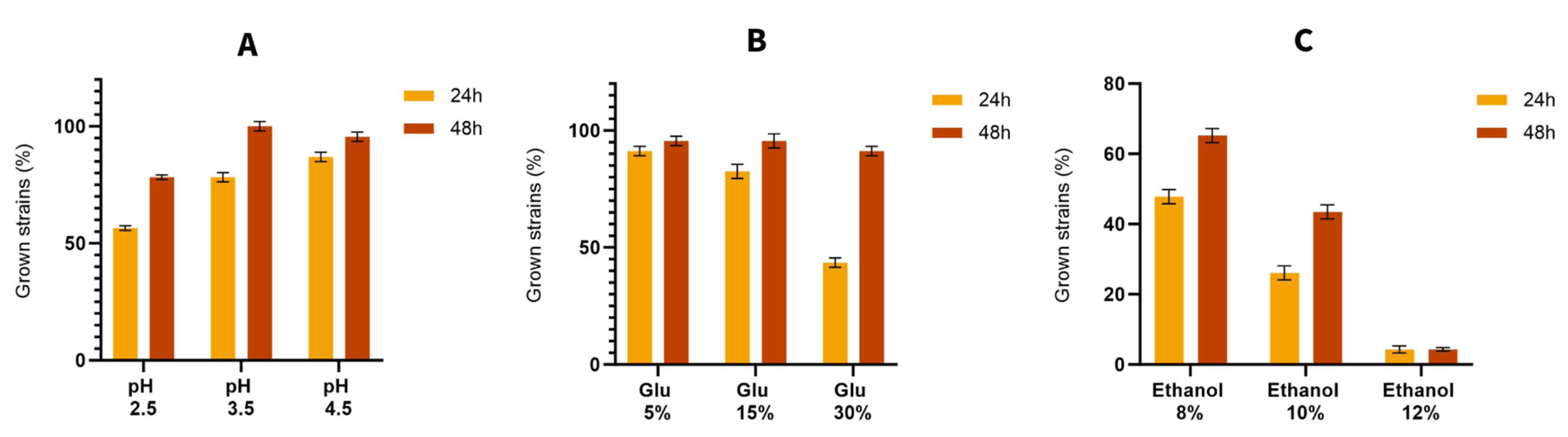

3.2. Resistance to Stressful Conditions

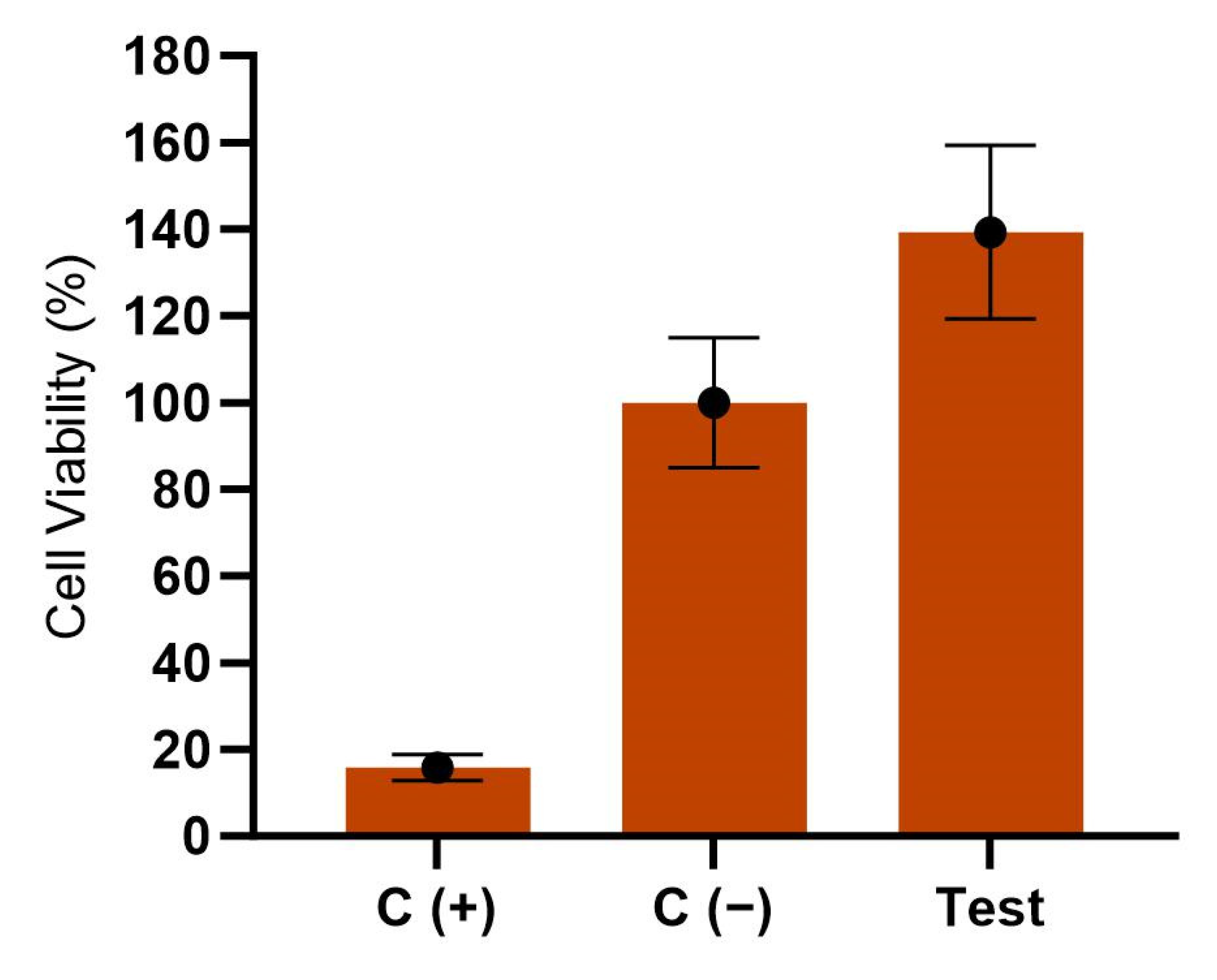

3.3. Inoculum Selection

3.4. Cytotoxicity Evaluation of Pichia manshurica

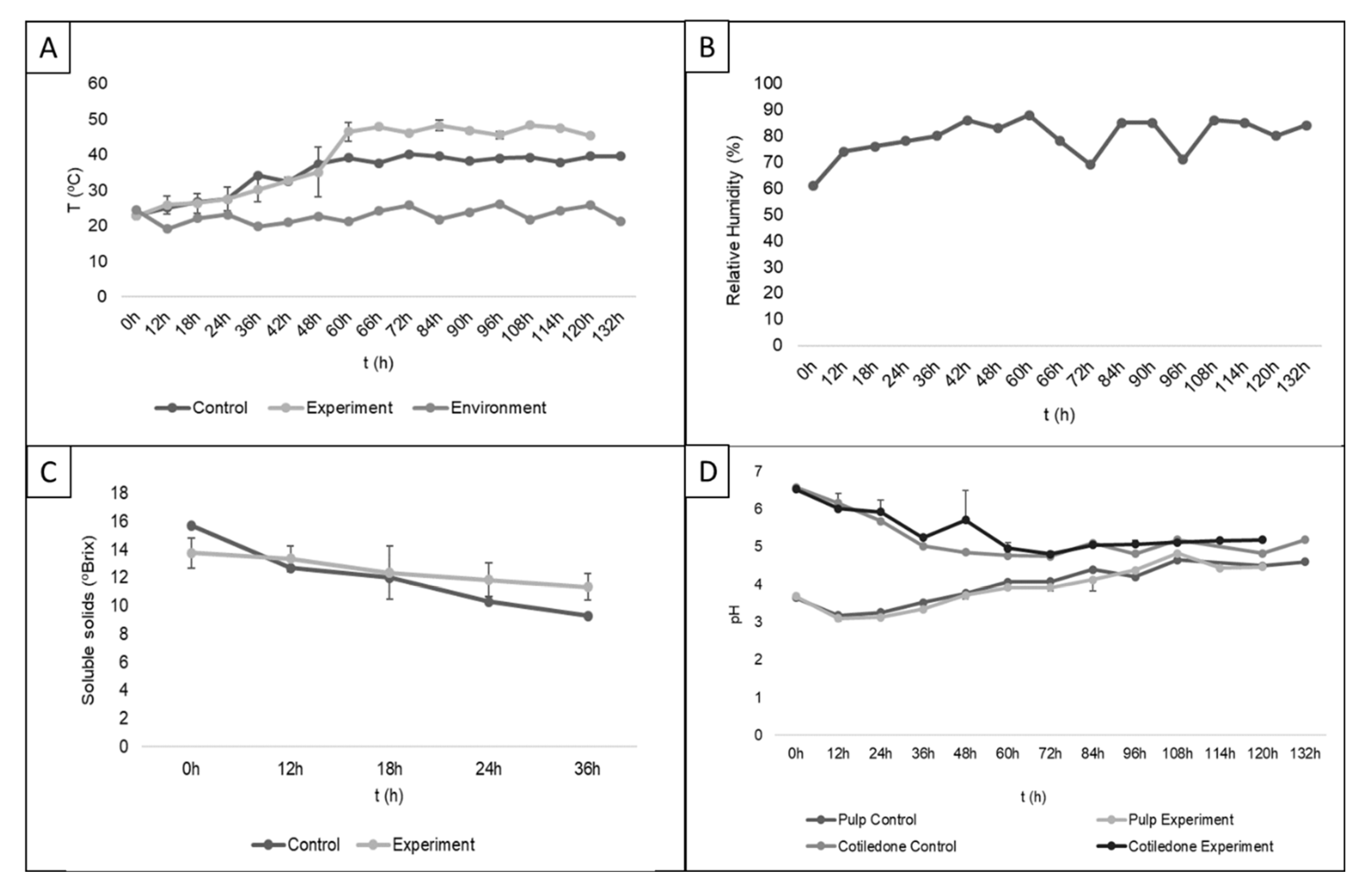

3.5. Inoculum Application in Fermentation Boxes

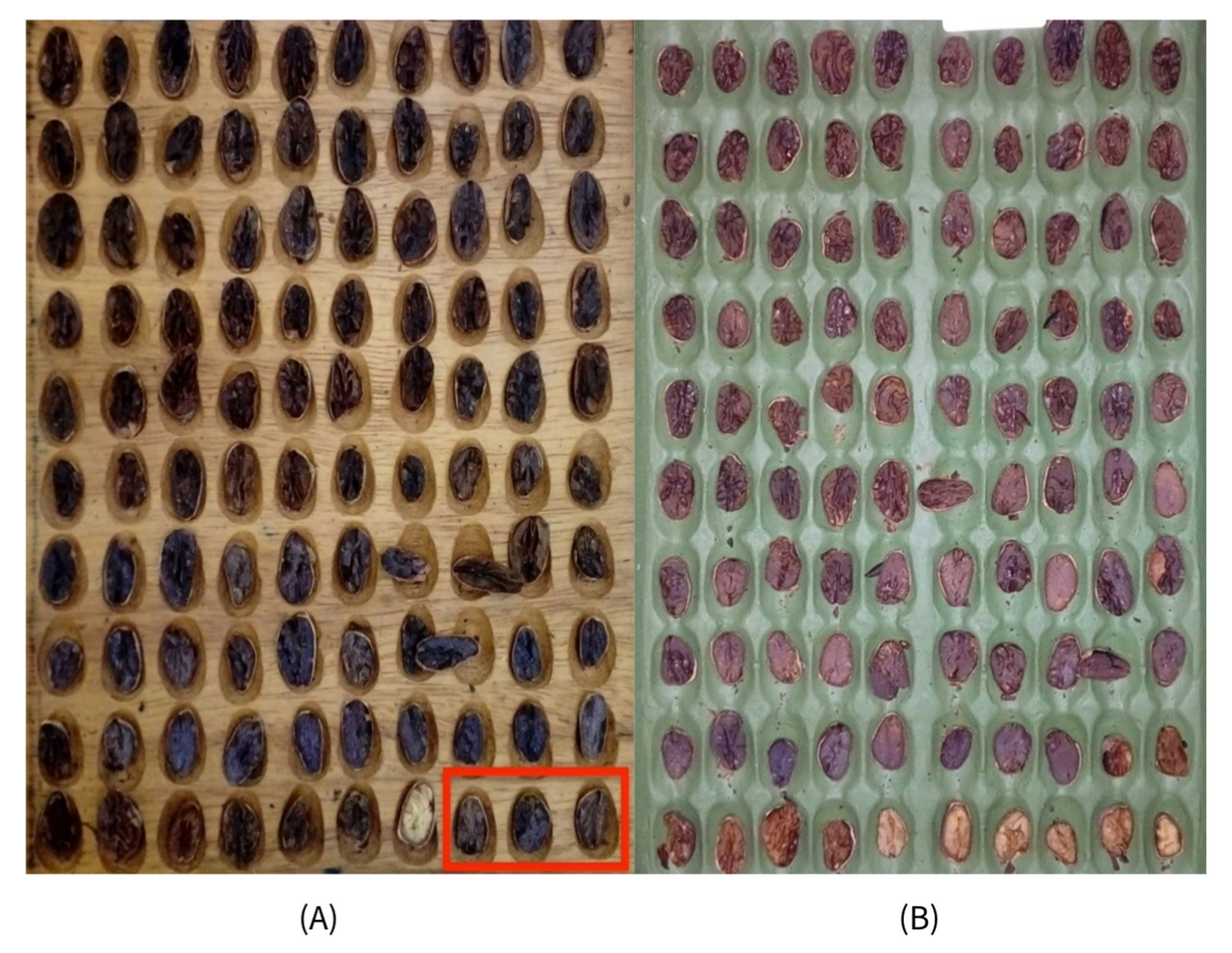

3.6. Impact of Starter Culture on the Final Quality and Safety of Cocoa Beans

3.7. Microbiological Safety Assessment of Cocoa Beans

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ho, V.T.T.; Zhao, J.; Fleet, G. Yeasts Are Essential for Cocoa Bean Fermentation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2014, 174, 72–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Veiga Moreira, I.M.; Miguel, M.G.d.C.P.; Duarte, W.F.; Dias, D.R.; Schwan, R.F. Microbial Succession and the Dynamics of Metabolites and Sugars during the Fermentation of Three Different Cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.) Hybrids. Food Res. Int. 2013, 54, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Huo, N.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, R.; Hou, H. Aroma-Enhancing Role of Pichia manshurica Isolated from Daqu in the Brewing of Shanxi Aged Vinegar. Int. J. Food Prop. 2017, 20, 2169–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perpetuini, G.; Tittarelli, F.; Battistelli, N.; Suzzi, G.; Tofalo, R. Contribution of Pichia manshurica Strains to Aroma Profile of Organic Wines. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2020, 246, 1405–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyotome, T.; Yamamoto, M.; Horie, M. Draft Genome Sequence of the Yeast Pichia Manshurica YM63, a Participant in Secondary Fermentation of Ishizuchi-Kurocha, a Japanese Fermented Tea. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, S.d.F.O.d.; Silva, L.R.C.; Junior, G.C.A.C.; Oliveira, G.; Silva, S.H.M.d.; Vasconcelos, S.; Lopes, A.S. Diversity of Yeasts during Fermentation of Cocoa from Two Sites in the Brazilian Amazon. Acta Amaz. 2019, 49, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, H.-M.; Vrancken, G.; Takrama, J.F.; Camu, N.; De Vos, P.; De Vuyst, L. Yeast Diversity of Ghanaian Cocoa Bean Heap Fermentations. FEMS Yeast Res. 2009, 9, 774–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Ospina, J.; Triboletti, S.; Alessandria, V.; Serio, A.; Sergi, M.; Paparella, A.; Rantsiou, K.; Chaves-López, C. Functional Biodiversity of Yeasts Isolated from Colombian Fermented and Dry Cocoa Beans. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koff, O.; Samagaci, L.; Goualie, B.; Niamke, S. Diversity of Yeasts Involved in Cocoa Fermentation of Six Major Cocoa-Producing Regions in Ivory Coast. Eur. Sci. J. ESJ 2017, 13, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Meersman, E.; Steensels, J.; Mathawan, M.; Wittocx, P.-J.; Saels, V.; Struyf, N.; Bernaert, H.; Vrancken, G.; Verstrepen, K.J. Detailed Analysis of the Microbial Population in Malaysian Spontaneous Cocoa Pulp Fermentations Reveals a Core and Variable Microbiota. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e81559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, O.d.S.; Chagas-Junior, G.C.; Chisté, R.C.; Martins, L.H.d.S.; Andrade, E.H.d.A.; Nascimento, L.D.d.; Lopes, A.S. Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Pichia manshurica from Amazonian Biome Affect the Parameters of Quality and Aromatic Profile of Fermented and Dried Cocoa Beans. J. Food Sci. 2022, 87, 4148–4161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.C.R. Beneficiamento de Cacau de Qualidade Superior, 1st ed.; PTCSB: Ilheus, Brazil, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Crafack, M.; Mikkelsen, M.B.; Saerens, S.; Knudsen, M.; Blennow, A.; Lowor, S.; Takrama, J.; Swiegers, J.H.; Petersen, G.B.; Heimdal, H.; et al. Influencing Cocoa Flavour Using Pichia Kluyveri and Kluyveromyces Marxianus in a Defined Mixed Starter Culture for Cocoa Fermentation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2013, 167, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leal, G.A.; Gomes, L.H.; Efraim, P.; de Almeida Tavares, F.C.; Figueira, A. Fermentation of Cacao (Theobroma cacao L.) Seeds with a Hybrid Kluyveromyces Marxianus Strain Improved Product Quality Attributes. FEMS Yeast Res. 2008, 8, 788–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lefeber, T.; Papalexandratou, Z.; Gobert, W.; Camu, N.; De Vuyst, L. On-Farm Implementation of a Starter Culture for Improved Cocoa Bean Fermentation and Its Influence on the Flavour of Chocolates Produced Thereof. Food Microbiol. 2012, 30, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwan, R.F. Cocoa Fermentations Conducted with a Defined Microbial Cocktail Inoculum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1998, 64, 1477–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, V.T.T.; Fleet, G.H.; Zhao, J. Unravelling the Contribution of Lactic Acid Bacteria and Acetic Acid Bacteria to Cocoa Fermentation Using Inoculated Organisms. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2018, 279, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggirello, M.; Nucera, D.; Cannoni, M.; Peraino, A.; Rosso, F.; Fontana, M.; Cocolin, L.; Dolci, P. Antifungal Activity of Yeasts and Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated from Cocoa Bean Fermentations. Food Res. Int. 2019, 115, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assi-Clair, B.J.; Koné, M.K.; Kouamé, K.; Lahon, M.C.; Berthiot, L.; Durand, N.; Lebrun, M.; Julien-Ortiz, A.; Maraval, I.; Boulanger, R.; et al. Effect of Aroma Potential of Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Fermentation on the Volatile Profile of Raw Cocoa and Sensory Attributes of Chocolate Produced Thereof. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2019, 245, 1459–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooi, T.S.; Ting, A.S.Y.; Siow, L.F. Influence of Selected Native Yeast Starter Cultures on the Antioxidant Activities, Fermentation Index and Total Soluble Solids of Malaysia Cocoa Beans: A Simulation Study. LWT 2020, 122, 108977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, D.S.; Rezende, R.P.; dos Santos, T.F.; Marques, E.d.L.S.; Ferreira, A.C.R.; e Silva, A.B.D.C.; Romano, C.R.; de Cerqueira e Silva, A.B.; da Cruz Santos, D.W.; Texeira Dias, J.C.; et al. Fermentation in Fine Cocoa Type Scavina: Change in Standard Quality as the Effect of Use of Starters Yeast in Fermentation. Food Chem. 2020, 328, 127110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, F.; De Vuyst, L. Lactic Acid Bacteria as Functional Starter Cultures for the Food Fermentation Industry. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2004, 15, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota-Gutierrez, J.; Botta, C.; Ferrocino, I.; Giordano, M.; Bertolino, M.; Dolci, P.; Cannoni, M.; Cocolin, L. Dynamics and Biodiversity of Bacterial and Yeast Communities during Fermentation of Cocoa Beans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84, e01164-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunshia, Y.; Sandhya, M.V.S.; Lingamallu, J.M.R.; Padela, J.; Murthy, P. Improved Fermentation of Cocoa Beans with Enhanced Aroma Profiles. Food Biotechnol. 2018, 32, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanens, E.; Freimüller Leischtfeld, S.; Volland, A.; Stevens, M.J.A.; Krähenmann, U.; Isele, D.; Fischer, B.; Meile, L.; Miescher Schwenninger, S. Screening of Lactic Acid Bacteria and Yeast Strains to Select Adapted Anti-Fungal Co-Cultures for Cocoa Bean Fermentation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2019, 290, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, C.M.; E Silva, A.B.d.C.; Marques, E.d.L.S.; Rezende, R.P.; Pirovani, C.P.; Ferreira, A.C.R.; Andrade, L.M.; Santos, D.W.d.C.; Díaz, A.M.; Soares, M.R.; et al. Biotechnological Starter Potential for Cocoa Fermentation from Cabruca Systems/Potencial Biotecnológico de Leveduras Starter Na Fermentação Do Cacau de Sistema Cabruca. Braz. J. Dev. 2021, 7, 60739–60759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekunsanmi, T.J.; Odunfa, S.A. Ethanol Tolerance, Sugar Tolerance and Invertase Activities of Some Yeast Strains Isolated from Steep Water of Fermenting Cassava Tubers. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 1990, 69, 672–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis of Aoac International, 18th ed.; Latimer, G.W., Ed.; Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Gaithersburgs, MD, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 2451:2014; Cocoa Beans—Specification. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- Brasil Ministério Da Saúde, Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (ANVISA). Regulamento Técnico Sobre Os Padrões Microbiológicos Para Alimentos; Resolução RDC No 12 de 02 de Janeiro de 2001; Brasil Ministério Da Saúde, Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (ANVISA): Brasília, Brazil, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- De Vuyst, L.; Leroy, F. Functional Role of Yeasts, Lactic Acid Bacteria and Acetic Acid Bacteria in Cocoa Fermentation Processes. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2020, 44, 432–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E Silva, A.B.d.C.; e Silva, M.B.d.C.; de Souza Silveira, P.T.d.S.; Marques, E.d.L.S.; Soares, S.E. Extraction and Determination of Invertase and Polyphenol Oxidase Activities during Cocoa Fermentation/Extração e Determinação Da Atividade de Invertase e Polifenoloxidase Durante Fermentação de Cacau. Braz. J. Dev. 2021, 7, 80316–80330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashko, S.; Zhou, N.; Compagno, C.; Piškur, J. Why, When, and How Did Yeast Evolve Alcoholic Fermentation? FEMS Yeast Res. 2014, 14, 826–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attfield, P. V Stress Tolerance: The Key to Effective Strains of Industrial Baker’s Yeast. Nat. Biotechnol. 1997, 15, 1351–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivorra, C.; Pérez-Ortín, J.E.; del Olmo, M. An Inverse Correlation between Stress Resistance and Stuck Fermentations in Wine Yeasts. A Molecular Study. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1999, 64, 698–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynd, L.R.; Ahn, H.-J.; Anderson, G.; Hill, P.; Sean Kersey, D.; Klapatch, T. Thermophilic Ethanol Production Investigation of Ethanol Yield and Tolerance in Continuous Culture. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 1991, 28–29, 549–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, R.O.; Batistote, M.; Cereda, M.P. Alcoholic Fermentation by the Wild Yeasts under Thermal, Osmotic and Ethanol Stress. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2013, 56, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouamé, C.; Loiseau, G.; Grabulos, J.; Boulanger, R.; Mestres, C. Development of a Model for the Alcoholic Fermentation of Cocoa Beans by a Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Strain. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2021, 337, 108917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samagaci, L.; Ouattara, H.; Goualie, B.; Niamke, S. Growth Capacity of Yeasts Potential Starter Strains under Cocoa Fermentation Stress Conditions in Ivory Coast. Emir. J. Food Agric. 2014, 26, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Melo Pereira, G.V.; Magalhães, K.T.; de Almeida, E.G.; da Silva Coelho, I.; Schwan, R.F. Spontaneous Cocoa Bean Fermentation Carried out in a Novel-Design Stainless Steel Tank: Influence on the Dynamics of Microbial Populations and Physical–Chemical Properties. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2013, 161, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente, J.; Calderón, F.; Santos, A.; Marquina, D.; Benito, S. High Potential of Pichia kluyveri and Other Pichia Species in Wine Technology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Song, L. Applicability of the MTT Assay for Measuring Viability of Cyanobacteria and Algae, Specifically for Microcystis Aeruginosa (Chroococcales, Cyanobacteria). Phycologia 2007, 46, 593–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthilraja, P.; Kathiresan, K. In Vitro Cytotoxicity MTT Assay in Vero, HepG2 and MCF -7 Cell Lines Study of Marine Yeast. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 28, 080–084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrini, S.; Mangani, S.; Romboli, Y.; Luti, S.; Pazzagli, L.; Granchi, L. Impact of Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Strains on Health-Promoting Compounds in Wine. Fermentation 2018, 4, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, N.N.; Ramos, C.L.; Ribeiro, D.D.; Pinheiro, A.C.M.; Schwan, R.F. Dynamic Behavior of Saccharomyces Cerevisiae, Pichia Kluyveri and Hanseniaspora Uvarum during Spontaneous and Inoculated Cocoa Fermentations and Their Effect on Sensory Characteristics of Chocolate. LWT–Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 63, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.C.R.; Marques, E.L.S.; Dias, J.C.T.; Rezende, R.P. DGGE and Multivariate Analysis of a Yeast Community in Spontaneous Cocoa Fermentation Process. Genet. Mol. Res. 2015, 14, 18465–18470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S.S.; Miller, K.B.; Lopes, A.S. Cocoa and Coffee. In Food Microbiology, Fundamentals and Frontiers; Doyle, M.P., Beuchat, L.R., Montville, T.J., Eds.; American Society for Microbiology Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001; pp. 721–733. [Google Scholar]

- Lehrian, D.W.; Patterson, G.R. Cocoa Fermentation. In Biotechnology, a Comprehensive Treatise; Rehm, H.J., Reed, G., Eds.; Wiley-VCH: Berlin, Germany, 1983; Volume 5, pp. 529–575. [Google Scholar]

- Ardhana, M.M.; Fleet, G.H. The Microbial Ecology of Cocoa Bean Fermentations in Indonesia. Int. J. Food. Microbiol. 2003, 86, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jespersen, L.; Nielsen, D.S.; Hønholt, S.; Jakobsen, M. Occurrence and Diversity of Yeasts Involved in Fermentation of West African Cocoa Beans. FEMS Yeast Res. 2005, 5, 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdul Samah, O.; Ibrahim, N.; Alimon, H.; Abdul Karim, M.I. Fermentation Studies of Stored Cocoa Beans. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1993, 9, 603–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biehl, B.; Brunner, E.; Passern, D.; Quesnel, V.C.; Adomako, D. Acidification, Proteolysis and Flavour Potential in Fermenting Cocoa Beans. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1985, 36, 583–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, C.E.; del Olmo, M.; Burri, C. Enzyme Activities in Cocoa Beans during Fermentation. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1998, 77, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misnawi; Jinap, S.; Jamilah, B.; Nazamid, S. Sensory Properties of Cocoa Liquor as Affected by Polyphenol Concentration and Duration of Roasting. Food Qual Prefer. 2004, 15, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 2451:2017; Cocoa Beans—Requirements. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Lima, L.J.R.; Almeida, M.H.; Nout, M.J.R.; Zwietering, M.H. Theobroma cacao L., “The Food of the Gods”: Quality Determinants of Commercial Cocoa Beans, with Particular Reference to the Impact of Fermentation. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2011, 51, 731–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Control Sample | Experimental Sample |

|---|---|---|

| Defects | Higher rate (internal mold, flattened, insect-damaged, germinated, and violet kernels > 50%) | Lower defect rate |

| Fermentation-Related | Higher % of compartmentation (white/brown almonds) and well-fermented almonds (70.3%) | Higher % of flat white, partially/sub-fermented almonds; fermentation index (85.1%) |

| pH | More acidic (5.20) | Less acidic (5.35)—more desirable |

| External Appearance | Brown almonds, no contamination | Brown almonds, no contamination |

| Aroma | Characteristic | Characteristic |

| Mold Presence | No external mold (drying well conducted) | No external mold (drying well conducted) |

| Key Notes | Higher % brown almonds | Higher fermentation index |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Silva, A.B.d.C.e.; Marques, E.d.L.S.; Rezende, R.P.; Santana, C.; Freitas, A.M.; Bessa Souza, M.C.; Santos, C.M.d.; Ferreira, A.C.R.; Soares, M.R.; Díaz, A.M.; et al. Use of Pichia manshurica as a Starter Culture for Spontaneous Cocoa Fermentation in Southern Bahia, Brazil. Fermentation 2025, 11, 694. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120694

Silva ABdCe, Marques EdLS, Rezende RP, Santana C, Freitas AM, Bessa Souza MC, Santos CMd, Ferreira ACR, Soares MR, Díaz AM, et al. Use of Pichia manshurica as a Starter Culture for Spontaneous Cocoa Fermentation in Southern Bahia, Brazil. Fermentation. 2025; 11(12):694. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120694

Chicago/Turabian StyleSilva, Adriana Barros de Cerqueira e, Eric de Lima Silva Marques, Rachel Passos Rezende, Cristiano Santana, Angelina Moreira Freitas, Maria Clara Bessa Souza, Carine Martins dos Santos, Adriana Cristina Reis Ferreira, Marianna Ramos Soares, Alberto Montejo Díaz, and et al. 2025. "Use of Pichia manshurica as a Starter Culture for Spontaneous Cocoa Fermentation in Southern Bahia, Brazil" Fermentation 11, no. 12: 694. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120694

APA StyleSilva, A. B. d. C. e., Marques, E. d. L. S., Rezende, R. P., Santana, C., Freitas, A. M., Bessa Souza, M. C., Santos, C. M. d., Ferreira, A. C. R., Soares, M. R., Díaz, A. M., Santos, Á. M. d. C., Andrade, L. M., Ramos, L. P., Romano, C. C., Dias, J. C. T., & Soares, S. E. (2025). Use of Pichia manshurica as a Starter Culture for Spontaneous Cocoa Fermentation in Southern Bahia, Brazil. Fermentation, 11(12), 694. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120694