Abstract

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) remains a critical global challenge, requiring novel complementary strategies beyond antibiotic development. Probiotic-fermented foods (PFFs) offer an emerging, low-cost approach to mitigate AMR risk through ecological, molecular, and immunological mechanisms. This review integrates mechanistic insights, clinical evidence, and translational frameworks linking PFFs to antimicrobial stewardship. Key mechanisms include colonization resistance, nutrient and adhesion-site competition, production of antimicrobial metabolites, such as bacteriocins, hydrogen peroxide, and organic acids and Quorum-quenching-sensing activities that suppress pathogen virulence. Randomized clinical trials indicate that fermented diets and probiotic supplementation can improve microbiome diversity, reduce inflammatory cytokines, and decrease antibiotic-associated diarrhea, though direct AMR outcomes remain underexplored. Evidence from kefir, kombucha, and other microbial consortia suggests potential for in vivo pathogen suppression and reduced infection duration. However, safe translation requires standardized starter-culture genomics, resistome monitoring, and regulatory oversight under QPS/GRAS frameworks. Integrating PFF research with One Health surveillance systems, such as the WHO GLASS platform, will enable tracking of antimicrobial consumption and resistance outcomes. Collectively, these findings position PFFs as promising adjuncts for AMR mitigation, linking sustainable food biotechnology with microbiome-based health and global stewardship policies.

1. Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is recognized as one of the most urgent public-health challenges of the twenty-first century. According to the World Health Organization’s Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Use Surveillance System (GLASS), nearly one in six bacterial infections worldwide now exhibit resistance to first-line therapies, leading to prolonged illness, increased morbidity and mortality, and significant economic strain on healthcare systems. The global rise in resistant pathogens not only undermines the effectiveness of essential medical treatments but also threatens routine procedures, such as surgeries, cancer therapies, and care of immunocompromised patients, that depend on reliable antimicrobial prophylaxis. While conventional antimicrobial stewardship has traditionally focused on optimizing antibiotic prescribing practices and strengthening infection-control measures, emerging scientific and policy frameworks now highlight the importance of preventive, nutritional, and microbiome-centered approaches to reduce infection risk and mitigate antibiotic demand [1,2,3,4]. Within this broader public-health context, probiotic-fermented foods (PFFs) have gained growing attention as sustainable, widely accessible tools capable of supporting microbiome resilience and potentially contributing to reduced infectious disease burden across populations [1,2,3,4].

Beyond its clinical impact, AMR also reflects broader ecological and societal pressures that demand integrated, multisectoral responses. The spread of resistance determinants across human, animal, and environmental interfaces, accelerated by global travel, intensive food production systems, and inadequate wastewater management demonstrates the limitations of antibiotic-centered interventions alone [1,2,3,4]. As resistant bacteria and mobile genetic elements circulate through food chains, agricultural systems, and natural ecosystems, there is increasing recognition that novel mitigation strategies must reinforce microbial ecosystem stability rather than rely solely on therapeutic control. This One Health perspective has catalyzed interest in interventions capable of modulating microbial communities in ways that reduce pathogen colonization and limit antibiotic use. Within this context, probiotic-fermented foods (PFFs) represent a promising, low-cost avenue for population-level resilience, supporting immune function, competitive exclusion of pathogens, and restoration of beneficial taxa disrupted by diet, stress, or infections [1,2,3,4].

Fermented foods are complex biological matrices in which selected or spontaneous microbial consortia transform raw substrates into products enriched with organic acids, peptides, vitamins, and bioactive metabolites [1,2,3,4]. When such foods contain defined probiotic strains, typically lactic acid bacteria and yeasts with demonstrated health benefits, they may be classified as probiotic-fermented foods [5,6,7,8,9]. Recent dietary-intervention trials have shown that regular consumption of fermented foods increases gut microbial diversity and attenuates in inflammatory responses in healthy adults [1,2,10]. Mechanistically, the microorganisms and postbiotic molecules present in PFFs exert multiple actions relevant to AMR mitigation: they compete with pathogens for adhesion sites and nutrients, produce bacteriocins and organic acids that inhibit antibiotic-resistant bacteria, enhance mucosal barrier function, and regulate host immune responses [3,4]. These cumulative effects can strengthen colonization resistance and potentially reduce infection rates and the unnecessary use of antibiotics, two essential targets of antimicrobial stewardship [1,2,3,4].

However, despite promising evidence, the translational bridge between PFF consumption and measurable AMR outcomes remains underdeveloped. The diversity of fermentation processes, microbial consortia, and product quality poses challenges to standardization, safety assurance, and mechanistic interpretation [1,2,3,4,10]. From a public-health perspective, the detection of antimicrobial-resistance genes (ARGs) in certain starter cultures and commercial probiotic formulations is particularly relevant, as these elements, especially when associated with mobile genetic platforms, may contribute to the unintended dissemination of resistance within the food chain. This concern extends beyond the food sector, given that mobile ARGs can circulate across human, animal, and environmental compartments, reinforcing AMR as a multisectoral OneHealth threat [1,2,3,4].

Strengthening genomic monitoring and functional characterization of PFF-associated microorganisms is therefore essential to distinguish intrinsic, non-transferable resistance traits from potentially mobilizable determinants that pose public-health risks. At present, key knowledge gaps limit regulatory clarity and hinder evidence-based implementation of PFFs in antimicrobial stewardship programs. These gaps include: (i) insufficient genome-resolved surveillance for starter and adjunct cultures; (ii) limited understanding of horizontal gene transfer potential during fermentation and gastrointestinal transit; (iii) variability in clinical and preclinical endpoints used to assess AMR-related benefits; and (iv) the absence of harmonized guidelines to define safety thresholds and quality criteria for PFFs [1,2,3,4,10].

Therefore, a critical synthesis of available data is required to delineate the mechanisms by which PFFs may support stewardship, to evaluate the strength and limitations of current clinical and preclinical evidence, and to outline regulatory and research pathways for their safe integration into public-health and One Health frameworks [1,2,3,4,10].

The objective of this review is to comprehensively analyze the role of probiotic-fermented foods within antimicrobial stewardship, focusing on three complementary dimensions: (1) the mechanistic basis through which PFFs influence microbial ecology, immune function, and pathogen suppression; (2) the clinical and translational evidence linking fermented-food consumption with reduced antibiotic exposure or improved microbiome recovery; and (3) the safety and regulatory considerations necessary to ensure that probiotic interventions contribute positively to the global fight against AMR. By bridging microbiology, nutrition, and public-health stewardship, this review aims to define how evidence-based PFFs could evolve from traditional dietary elements into scientifically validated components of next-generation antimicrobial-resistance mitigation strategies.

To ensure a comprehensive and balanced synthesis, this review was conducted as a narrative and integrative literature analysis. Peer-reviewed articles, official reports, and authoritative guidelines were searched across multiple scientific and institutional databases, including PubMed, ScienceDirect, Scopus, and the World Health Organization (WHO) website, as well as repositories of the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). The search covered publications from 2010 to 2025, using combinations of relevant keywords such as “probiotic-fermented foods,” “antimicrobial resistance,” “stewardship,” “bacteriocins,” “resistome,” “One Health,” “kefir,” and “kombucha”.

Additional references were identified through citation tracking of key papers and institutional reports. Studies addressing mechanistic, clinical, technological, or regulatory aspects of PFFs in the context of AMR were prioritized. The resulting corpus informed the conceptual integration presented in this manuscript, linking microbial ecology, food biotechnology, and public-health policy under a unified One Health framework.

2. Mechanistic Landscape: How Probiotic-Fermented Foods (PFFs) Can Counter Pathogens and Antibiotic Pressure

The bioactivity of probiotic-fermented foods (PFFs) arises from the combined action of their living microorganisms, structural cell-wall components, and diverse fermentation-derived metabolites, all of which synergistically modulate the gut microbial ecosystem and pathogen dynamics. Once consumed, these microorganisms and metabolites interact with the host intestinal environment by influencing microbial succession, strengthening mucosal barriers, and shaping competitive interactions between beneficial and pathogenic taxa. Such interactions operate through multiple and overlapping mechanisms that reinforce colonization resistance, inhibit pathogenic growth, regulate innate and adaptive immune responses, and alter metabolic niches in ways that are unfavorable to antibiotic-resistant organisms [1,2,3,4,10]. These effects are further supported by the production of organic acids, bioactive peptides, and short-chain fatty acids, which can directly impair pathogen viability while promoting a microbiome structure associated with greater resilience to infection and reduce reliance on antibiotics [10].

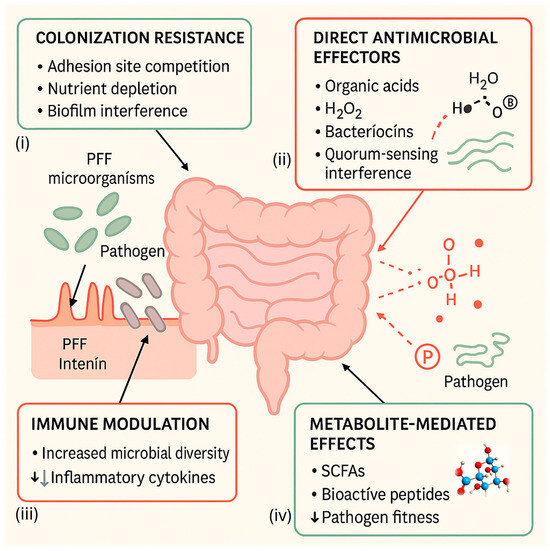

Given the complexity and interdependence of these processes, a visual synthesis is essential to clarify how microbial, metabolic, and immunological pathways interface within the broader concept of antimicrobial stewardship [1,2,3,4,10]. Figure 1 provides an integrated overview of these mechanistic pathways, illustrating how PFF-associated microorganisms and their metabolites collectively contribute to pathogen suppression, shaping of microbial communities, enhancement of host defenses, and mitigation of antimicrobial-resistance (AMR) risks [1,2,3,4,10]. By capturing these interactions in a unified framework, the figure helps contextualize the potential role of PFFs as complementary tools within public-health and One Health strategies aimed at reducing the global burden of AMR [1,2,3,4,10].

Figure 1.

Mechanisms of probiotic-fermented foods (PFFs) in antimicrobial stewardship. Schematic representation of the primary mechanisms by which probiotic-fermented foods (PFFs) contribute to pathogen control and antimicrobial-resistance (AMR) mitigation. The central intestine diagram illustrates interactions among four interconnected mechanisms: (i) colonization resistance, including competition for epithelial adhesion sites, nutrient depletion, and biofilm interference; (ii) direct antimicrobial effectors, such as organic acids, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and bacteriocins (nisin-like, pediocin-like, and kefir-derived peptides) that disrupt pathogen membranes or Quorum-sensing; (iii) immune modulation, in which fermented-food microorganisms enhance microbial diversity and down-regulate inflammatory cytokines; and (iv) metabolite-mediated effects, involving short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and other bioactive compounds that reduce pathogen fitness and promote mucosal integrity. Together, these processes reinforce host–microbe equilibrium, prevent pathogen overgrowth, and complement traditional antibiotic-stewardship strategies.

2.1. Colonization Resistance and Ecological Competition

A central mechanism by which PFFs support antimicrobial resilience is colonization resistance, defined as the capacity of a balanced microbiota to prevent pathogen establishment through competitive exclusion. The lactic acid bacteria (LAB) and yeasts typically found in kefir, kombucha, and other fermented matrices occupy epithelial adhesion sites, compete for essential nutrients, and form protective biofilms that act as physical and biochemical barriers to pathogen invasion [6,7]. This microbial competition limits the expansion of antibiotic-resistant strains, such as Escherichia coli, Clostridioides difficile, and Klebsiella pneumoniae, by depriving them of ecological niches within the gastrointestinal tract [8,9].

Fermented foods also contribute to biofilm interference. Certain kefir- and kombucha-derived isolates, including Lactobacillus kefiri, Lactobacillus plantarum, and Acetobacter spp., secrete extracellular polysaccharides and surface proteins that inhibit pathogen biofilm formation or destabilize existing structures [8,10,11]. This effect has been demonstrated in vitro against multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, suggesting that PFF microorganisms can disrupt Quorum-quenching and surface adhesion, mechanisms often associated with antibiotic tolerance. Together, these ecological and structural interactions underline the preventive rather than curative contribution of PFFs to AMR mitigation, complementing antibiotic stewardship by reducing the frequency and persistence of infections requiring pharmacological treatment.

2.2. Direct Antimicrobial Effectors: Organic Acids, Hydrogen Peroxide, and Bacteriocins

Probiotic and fermentative microorganisms produce a wide range of antimicrobial effectors that directly suppress pathogenic bacteria. Among the most potent are organic acids (lactic, acetic, and propionic acids), hydrogen peroxide, ethanol, carbon dioxide, and antimicrobial peptides collectively known as bacteriocins. These molecules act synergistically to lower environmental pH, alter membrane permeability, and inhibit cell wall synthesis, thereby reducing pathogen viability and virulence [3,4,10,12].

Organic acids generated during fermentation decrease intestinal pH to levels below 4.5, inhibiting acid-sensitive pathogens such as Salmonella enterica and Listeria monocytogenes. Additionally, LAB-derived hydrogen peroxide and reuttering contribute to redox imbalance and oxidative stress in competing microorganisms [7,9]. Such effects are enhanced in mixed fermentations like kefir, where co-cultivation of LAB and yeasts amplifies metabolite diversity and antimicrobial spectrum [8,9].

Bacteriocins, ribosomal synthesized antimicrobial peptides, represent particularly precise anti-pathogen tools (Box 1). Classical examples include nisin (from Lactococcus lactis) and pediocin (from Pediococcus acidilactici), both recognized for their ability to permeabilize bacterial membranes and inhibit Gram-positive pathogens, including methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) [3,4,12]. Novel bacteriocin-like compounds from kefir isolates, such as “kefirins” and “kefircins”, exhibit broad-spectrum activity and stability under gastrointestinal conditions [8,10,13].

The emergence of precision fermentation technologies now enables modulation of bacteriocin production and targeting, allowing the design of strain-specific antimicrobial formulations that could replace or potentiate antibiotic action in food and clinical contexts [5,10,12]. Importantly, bacteriocins act locally and degrade rapidly, minimizing selective pressure for resistance compared with conventional antibiotics [4,13]. Their application within PFFs therefore exemplifies how microbial metabolites can serve both as food preservatives and as functional agents in antimicrobial stewardship.

To provide a concise overview of their mechanisms and relevance to PFFs, the main features of bacteriocins are summarized in Box 1.

Box 1. Bacteriocins as Targeted Antimicrobial Peptides.

Bacteriocins are small, ribosomally synthesized peptides produced by probiotic and fermentative bacteria. They typically exhibit narrow or moderately broad spectra of antimicrobial activity and act mainly through membrane pore formation or inhibition of peptidoglycan synthesis. Compared with conventional antibiotics, bacteriocins offer several advantages: (i) strain-specific activity that minimizes collateral effects on commensal microbiota; (ii) biodegradability and low environmental persistence; (iii) potential synergy with host immune responses; and (iv) compatibility with food-grade fermentation processes [3,4,12]. Incorporating bacteriocin-producing strains into probiotic-fermented foods may therefore represent a sustainable strategy to reduce pathogen load and decrease antibiotic reliance within the One Health framework.

2.3. Immune Modulation: Fermented-Food Diets Increasing Diversity and Lowering Inflammatory Cytokines (Human RCT)

Regular consumption of probiotic-fermented foods (PFFs) has been associated with increased gut microbial diversity and attenuation of systemic inflammatory signaling in humans. In a randomized dietary intervention, a fermented-food-rich diet modulated multiple immune cell signatures and decreased circulating inflammatory cytokines while expanding microbiome diversity, an effect consistent with the ecological stabilization that underlies resistance to infection and antibiotic-associated dysbiosis [1,2,14].

These immunological shifts, which include reductions in IL-6 and other pro-inflammatory mediators, provide a plausible host-directed pathway by which PFFs could reduce infection susceptibility and, indirectly, antibiotic demand in community settings [1,14,15].

2.4. Metabolite-Mediated Effects: SCFAs, Bioactive Peptides, and Acidification That Lowers Pathogen Fitness

Beyond live cells, PFFs deliver postbiotics, notably short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), peptides, and other metabolites, that reshape gut physiology and pathogen fitness. SCFAs (acetate, propionate, butyrate) enhance epithelial barrier integrity, modulate immune tone via GPCR signaling and histone acetylation, and can directly suppress pathogen growth in a pH- and concentration-dependent manner [15,16,17].

Acidification from lactic and acetic acids lowers luminal pH and disrupts proton gradients, inhibiting acid-sensitive enteropathogens; in parallel, fermentation-derived peptides and small molecules can impair virulence programs, interfere with Quorum-quenching communication, and attenuate biofilm formation [3,4,12,15,16,17]. Together, these metabolic effects create an ecological landscape less permissive to colonization and expansion of antibiotic-resistant organisms, complementing the direct antimicrobial mechanisms described above.

2.5. Potential Anti-AMR Leverage: Shorter Illness → Fewer Prescriptions in Mild URTIs (Caveats Apply)

From a stewardship perspective, even modest reductions in symptom duration or severity for self-limited infections could translate into fewer antibiotic prescriptions. A recent randomized clinical trial in children with upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs) reported that a multi-strain probiotic mixture shortened fever duration by approximately two days versus placebo, without safety concerns, an effect that, if replicated, could plausibly reduce precautionary antibiotic use in primary care [18].

However, evidence remains mixed across populations and formulations: some pragmatic trials show no reduction in antibiotic administration with probiotics in older adults, underscoring that probiotics do not replace antibiotics and benefits are likely context- and product-specific [19,20]. Consequently, future studies should incorporate AMR-relevant endpoints (e.g., antibiotic prescriptions, multidrug-resistant organism carriage, resistome load) while standardizing strains, doses, and matrices typical of PFFs.

3. Evidence Base

3.1. Dietary Fermented Foods

Dietary intervention studies have demonstrated that the habitual consumption of fermented foods can beneficially modulate host immunity and microbial ecology. A pivotal randomized controlled trial (RCT) conducted by Wastyk et al. [1] revealed that a 10-week fermented-food diet significantly increased gut microbial diversity and decreased a broad range of inflammatory cytokines in healthy adults. These findings indicate that fermented-food consumption supports resilience against dysbiosis caused by antibiotics and may strengthen the gut ecosystem’s capacity to resist colonization by opportunistic pathogens [14,21].

Beyond the Cell study, observational and experimental data reinforce that fermented diets enriched with lactic acid bacteria (LAB) can improve epithelial barrier integrity, increase immunoglobulin A (IgA) production, and modulate toll-like receptor signaling, all of which are relevant for AMR prevention through improved mucosal immunity [14,15,22]. LAB present in fermented foods also contribute to the maintenance of intestinal homeostasis through competitive exclusion, secretion of organic acids, and production of antimicrobial peptides, which together reduce the ecological niches available for resistant pathogens [14,15,22].

Additional evidence from food microbiology studies demonstrates that LAB naturally present in fermented foods frequently exhibit metabolic traits that favor a healthier microbial environment, such as lactic-acid–driven pH reduction, biofilm disruption, and inhibition of pathogen adhesion to epithelial surfaces [14,15,22]. These microbes also produce fermentation-derived metabolites that modulate immune pathways involved in infection control and may attenuate inflammatory processes that otherwise increase susceptibility to resistant infections. Importantly, fermented foods rich in LAB have been shown to enhance microbial community stability following antibiotic exposure, supporting recovery of beneficial taxa and limiting expansion of resistant strains [14,21].

Moreover, findings from traditional fermented-food microbiota research suggest that the ecological interactions established during fermentation, such as cross-feeding, metabolite exchange, and in situ bacteriocin synthesis, contribute to shaping microbial assemblages with natural antagonistic activity against opportunistic pathogens [14,15,22]. Such mechanisms reinforce colonization resistance and reduce the likelihood that antibiotic-resistant organisms can proliferate or persist in the gut. These combined effects provide physiological and ecological justification for exploring probiotic-fermented foods as complementary tools in antimicrobial stewardship, especially within One-Health frameworks that integrate human, food, and environmental microbiomes [1,2,3,4,10].

3.2. Probiotics in Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhea (AAD) and Infection Outcomes

Clinical evidence for the prophylactic use of probiotics, particularly when delivered through fermented foods, has been most consistently observed in antibiotic-associated diarrhea (AAD) prevention. Meta-analyses covering more than 11,000 participants have confirmed a significant reduction in AAD incidence among subjects receiving probiotic strains such as Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG, Saccharomyces boulardii, and Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis, although the magnitude of benefit varies by species, dose, and clinical context [23,24].

Recent updates highlight an emerging stewardship-relevant dimension: in pediatric populations, probiotic supplementation during upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs) shortened fever duration by nearly two days and reduced overall symptom burden [18]. However, results across studies remain heterogeneous; pragmatic trials in institutionalized older adults found no significant decrease in antibiotic prescribing with probiotic supplementation [20]. Taken together, these findings support a modest yet reproducible effect of probiotics on maintaining gut homeostasis and reducing antibiotic-related adverse effects, an important auxiliary goal within AMR mitigation frameworks.

3.3. Ferment-Derived Antimicrobials: The Kefir Model

Among traditional fermented matrices, kefir stands out as an intricate symbiotic ecosystem composed of lactic acid bacteria, acetic acid bacteria, and yeasts coexisting in a polysaccharide matrix known as kefiran. This microbial consortium produces a vast repertoire of antimicrobial compounds, including organic acids, hydrogen peroxide, ethanol, diacetyl, and numerous bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances (BLIS) with demonstrated activity against antibiotic-resistant pathogens [8,9,10,13,25,26,27].

Experimental studies have demonstrated that kefir microorganisms such as Lactobacillus kefiri, Lactobacillus plantarum, and Kazachstania exigua inhibit Salmonella enterica, Listeria monocytogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, and Escherichia coli both in vitro and in vivo [8,25]. The fermentation of dairy, plant, and cereal substrates using kefir grains generates bioactive peptides with dual functionality, nutritional and antimicrobial, enhancing host defense while maintaining microbial equilibrium [9,26].

Recent research by Magalhães-Guedes and collaborators has expanded this knowledge by linking kefir-derived consortia to systemic and neuroimmune modulation, proposing that “smart probiotics” from kefir could interact with the gut–brain axis through neurotransmitter (GABA, serotonin) and cytokine regulation [8,9,28]. These studies provide mechanistic and translational evidence that kefir fermentation may contribute to the control of pathogen proliferation and the reduction in antibiotic exposure when integrated into regular dietary practices.

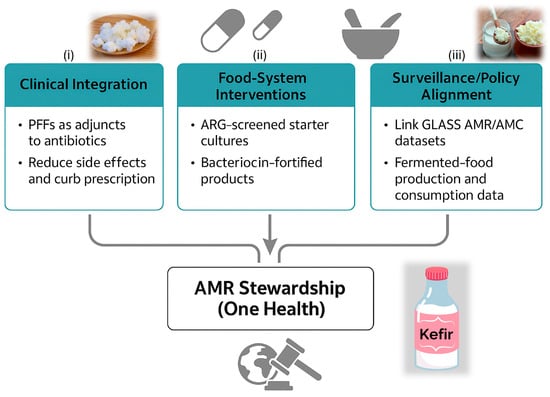

The interconnected clinical, food-system, and policy pathways through which probiotic-fermented foods contribute to antimicrobial stewardship within the One-Health framework are summarized in Figure 2, illustrating how nutritional microbiology, safe fermentation technologies, and surveillance integration converge to support sustainable AMR mitigation.

Figure 2.

Translational Pathways Linking Probiotic-Fermented Foods to Antimicrobial Stewardship. A schematic diagram summarizing three complementary translational axes through which probiotic-fermented foods (PFFs) can contribute to antimicrobial stewardship under the One-Health framework: (i) Clinical integration, highlighting the use of PFFs as adjuncts to antibiotics to reduce side effects and unnecessary prescriptions; (ii) Food-system interventions, emphasizing ARG-screened starter cultures and bacteriocin-fortified products for safer and more functional fermentation processes; and (iii) Surveillance and policy alignment, integrating fermented-food production and consumption data with GLASS AMR/AMC datasets for public-health monitoring. Together, these pathways illustrate a multi-level strategy that connects nutritional microbiology, sustainable food technology, and antimicrobial-resistance mitigation. Abbreviations: PFFs, probiotic-fermented foods; ARG, antimicrobial-resistance gene; GLASS, Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Use Surveillance System; AMR, antimicrobial resistance; AMC, antimicrobial consumption.

Clinical and preclinical evidence collectively supports that probiotic-fermented foods reduce the incidence of AAD and modestly shorten illness duration in mild infections such as URTIs. Ferment-derived antimicrobial metabolites, particularly those from kefir, strengthen ecological and immunological resilience, forming a biochemical bridge between nutritional microbiology and antimicrobial stewardship. Nevertheless, direct AMR endpoints (e.g., reduction in multidrug-resistant organism colonization, antibiotic-consumption metrics, or resistive analyses) remain scarce and should be prioritized in future standardized clinical trials linked to One Health surveillance systems [27,28,29].

3.4. Ferment-Derived Antimicrobials: The Kombucha Model

Kombucha represents another emblematic fermented matrix with remarkable antimicrobial and functional potential. It is produced through the symbiotic activity of acetic acid bacteria (AABs), lactic acid bacteria (LABs), and yeasts that coexist in a cellulose-based biofilm known as the SCOBY (Symbiotic Culture of Bacteria and Yeast). During fermentation, this microbial consortium converts sugars into a variety of bioactive compounds, including organic acids (acetic, gluconic, glucuronic), ethanol, carbon dioxide, polyphenol derivatives, and bacteriocin-like peptides, all of which contribute to pathogen inhibition and gut homeostasis [8,27].

Studies have demonstrated that kombucha extracts and isolates derived from its microbial members, such as Komagataeibacter xylinus, Zygosaccharomyces kombuchaensis, and Brettanomyces bruxellensis, exhibit broad-spectrum inhibitory activity against Escherichia coli, Salmonella enterica, Listeria monocytogenes, and Staphylococcus aureus [8]. This activity is mediated not only by low pH and organic acids but also by secondary metabolites and bioactive peptides that act synergistically to disrupt bacterial membranes and Quorum-quenching systems.

Recent innovations have expanded the application of kombucha beyond tea substrates. Yassin et al. [27] developed fruit-based smoothies fermented with kombucha microorganisms, demonstrating improved antioxidant capacity, increased microbial viability, and retention of functional metabolites. Such findings reinforce kombucha’s potential as a non-dairy probiotic delivery system with cross-functional properties relevant to antimicrobial stewardship.

Together, the compositional and functional diversity of kombucha fermentation positions it as a biochemical platform for natural antimicrobial production. When standardized for safety and monitored for the absence of transmissible resistance genes, kombucha-derived consortia can serve as sustainable microbial tools for modulating the gut microbiome and reducing infection risk, an important goal within One-Health-driven antimicrobial stewardship [8,27].

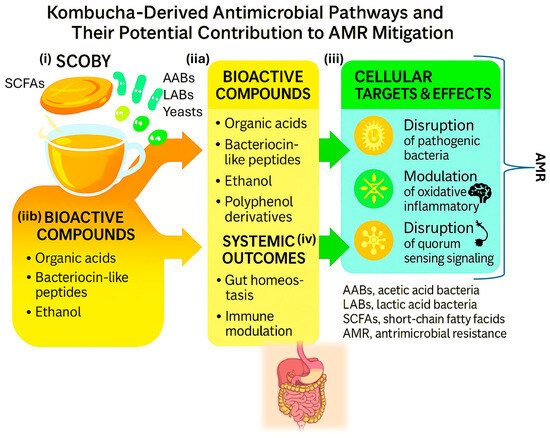

The multifactorial nature of kombucha’s antimicrobial potential and its translational relevance to antimicrobial stewardship can be visualized through the integrated model presented in Figure 3, which summarizes the composition of the SCOBY microbial consortium, the key bioactive compounds produced during kombucha fermentation, their cellular and molecular targets, and the systemic outcomes associated with host resilience and reduced antibiotic dependence [8,27]. As shown in the figure, the SCOBY is composed primarily of acetic acid bacteria (AABs), lactic acid bacteria (LABs), and yeasts, which interact synergistically to generate a diverse repertoire of metabolites, including organic acids, ethanol, bacteriocin-like peptides, polyphenol derivatives, and short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). These metabolites form the biochemical foundation of kombucha’s antimicrobial activity.

Figure 3.

Kombucha-Derived Antimicrobial Pathways and Their Potential Contribution to AMR Mitigation. Schematic representation of antimicrobial and immunomodulatory mechanisms derived from kombucha fermentation. The diagram illustrates: (i) the microbial consortium within the SCOBY (AABs, LABs, and yeasts); (iia,iib) the production of bioactive compounds such as organic acids, bacteriocin-like peptides, ethanol, and polyphenol derivatives; (iii) their cellular targets and effects, including disruption of pathogenic bacteria, modulation of oxidative and inflammatory responses, and inhibition of Quorum-sensing signaling; and (iv) systemic outcomes, encompassing gut homeostasis, immune modulation, and reduced antibiotic demand.

Figure 3 also illustrates how these fermentation-derived compounds act on specific cellular targets: (i) disruption of pathogenic bacteria through pH reduction, membrane destabilization, and metabolic inhibition; (iia,iib) modulation of oxidative and inflammatory pathways, which may decrease host susceptibility to infection; and (iii) interference with quorum-sensing signaling, thereby impairing pathogen coordination, virulence, and biofilm formation. By integrating these microbial and molecular mechanisms, the model highlights how kombucha-derived metabolites create hostile conditions for antibiotic-resistant organisms while simultaneously supporting beneficial taxa and mucosal immunity.

Finally, the figure connects these cellular effects to broader systemic outcomes, such as enhanced gut homeostasis and modulation of immune responses, which contribute to lower infection risk and reduce the likelihood of antibiotic use [8,27]. Through this multilevel framework from the microbial ecology of the SCOBY to host-level physiological responses. Figure 3 underscores kombucha’s potential role as a complementary tool within antimicrobial stewardship strategies and within a One-Health perspective.

4. Safety, AMR Risk, and Regulatory Guardrails

4.1. ARGs in Fermented Foods and Supplements: Prevalence, Context, and HGT Conditions

Multiple surveys and reviews indicate that antimicrobial-resistance genes (ARGs) and resistant bacteria can be detected in a subset of fermented foods and in some probiotic supplements, with prevalence varying by matrix, process, and microbial consortium [30,31]. Mechanistically, several non-pathogenic carriers (e.g., lactic acid bacteria, coagulase-negative staphylococci) may harbor intrinsic or acquired resistance; horizontal gene transfer (HGT) is theoretically favored by high cell density, close cell–cell contact, biofilms, and mobile genetic elements within fermentation ecosystems [30,31]. Recent meta-analyses and culture/metagenomic studies reported ARGs and viable resistant isolates in certain retail products (e.g., kimchi, artisan cheeses) and suggested that intervention diets rich in fermented foods can transiently increase gut resistome abundance in healthy adults, though the clinical significance remains uncertain and appears context dependent [32].

Conversely, substrate-anchored metagenomics across diverse ferments (including kombucha and water kefir) show large between-product variability, with some plant ferments displaying low detectable ARG counts under tested conditions [33]. Together, these findings support a risk-stratified view: while most fermented foods are safe, ARG surveillance is warranted, particularly for spontaneously fermented products and non-standardized starter cultures [30,31,32,33].

4.2. Screening Frameworks (GRAS/QPS) and Genome-Resolved Oversight

Current safety frameworks increasingly integrate AMR assessment. In the EU, the EFSA Qualified Presumption of Safety (QPS) process periodically updates taxonomic units with attention to acquired AMR determinants and overall safety dossiers [34]. In the U.S., FDA GRAS notifications for food microbes commonly include phenotypic antibiotic susceptibility testing and bioinformatic screens (e.g., CARD/ResFinder) to document absence of acquired, mobile ARGs of clinical concern [35,36].

Beyond point assessments, agencies and research consortia advocate genome-resolved surveillance for starter and adjunct cultures, combining complete genome assemblies, mobile-element scanning, and periodic re-qualification, and leveraging WGS/metagenomics in food safety investigations to improve traceability and risk attribution [34,37]. In line with these recommendations, several regulatory and scientific bodies emphasize that, for PFFs, product dossiers should include strain identity, genome sequence, and mobile-element context, along with clear labeling (strain IDs, CFU/dose, sequencing accession numbers where applicable) to better align consumer use with stewardship and safety goals.

4.3. Risk–Benefit Balance and Standardization Needs

Evidence to date suggests that ARG loads can be low in many plant-based ferments (e.g., kombucha, some water kefir) but are batch- and matrix-dependent; reports also indicate higher diversity of putative ARGs in certain water-kefir datasets than in milk-kefir/kombucha AAB metagenome-assembled genomes, underscoring that matrix, starter origin, and process control matter [33,38].

Given these gradients, standardization of starters (genome-verified, mobile-element screened), process controls (pH/time/temperature, contamination checks), and transparent labeling are realistic levers to retain health benefits while mitigating AMR risk. Importantly, routine post-market surveillance (periodic WGS/metagenomics of production lots) and data sharing can connect food-microbiology oversight to One Health AMR systems and help define product categories with low ARG/MGE risk profiles suited for stewardship-oriented use [31,33,37].

5. Translational Pathways for Stewardship (One Health)

The translation of probiotic-fermented food (PFF) research into antimicrobial-stewardship practice requires integration across clinical, food-system, and policy domains under the One Health paradigm. This integration aims to transform the preventive and restorative functions of PFFs into measurable public-health impact.

5.1. Clinical Integration

Clinically, PFFs can function as adjuncts to antibiotic therapy, reducing side effects such as antibiotic-associated diarrhea (AAD), sustaining microbial diversity, and potentially curbing unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions in self-limited infections [18,19,20,39]. Incorporation into hospital and community protocols should follow evidence-based guidelines, ensuring that probiotic strains are validated for safety and function. Tracking outcomes through GLASS (Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Use Surveillance System) indicators, including antimicrobial consumption (AMC) and resistance (AMR) rates, can help quantify PFF impacts on antibiotic stewardship at population scale [40].

5.2. Food-System Interventions

Across the agro-food chain, scaling safe fermentation technologies with starter cultures screened for ARGs and MGEs is essential [30,31,32,33]. Moreover, the development of bacteriocin-fortified fermented foods or bio-preservative systems offers an eco-friendly strategy to reduce pathogen burden and antibiotic dependence in livestock and food processing [4,12,41]. Studies in food-biotechnology pipelines have demonstrated that such biopreservatives, based on Lactococcus or Pediococcus peptides, can replace conventional antibiotics for pathogen control without compromising product quality [41,42]. Integrating these innovations into food policy could thus translate microbiological safety into tangible AMR mitigation.

The main performance indicators that can guide the integration of PFFs into clinical and food-system stewardship programs are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Proposed indicators (Key Performance Indicators (KPI)) for integrating probiotic-fermented foods into antimicrobial-stewardship frameworks.

Table 1 summarizes measurable indicators that can be incorporated into antimicrobial-stewardship programs to monitor the clinical, industrial, and policy-level impacts of probiotic-fermented foods (PFFs). These indicators align with GLASS metrics for antimicrobial consumption (AMC) and resistance (AMR) and support integration of food-microbiology data within One-Health surveillance systems.

5.3. Surveillance and Policy Alignment

For sustainable translation, food-microbiology oversight must be harmonized with AMR surveillance systems. The WHO GLASS framework, updated in 2025, emphasizes data integration across human, animal, and environmental sectors [40,43]. Including PFF exposure variables in population cohorts and AMR/AMC datasets would allow correlation between fermented-food intake, microbiome health, and resistance trends. Regulatory authorities, such as EFSA, FDA, and WHO, increasingly recognize the importance of transparent labeling, genome-verified strains, and resistome monitoring in probiotic foods [34,35,36,37,44]. Coordinated action among these stakeholders is key to transforming fermented foods into a recognized component of preventive antimicrobial stewardship.

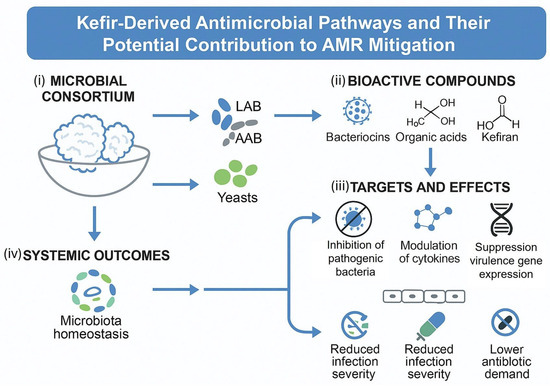

The multifactorial antimicrobial potential of kefir and its mechanistic relevance to antimicrobial-resistance mitigation are illustrated in Figure 4, which summarizes the microbial consortium, key bioactive compounds, molecular targets, and systemic outcomes that contribute to host resilience and reduced antibiotic demand [34,35,36,37,40,44]. As shown in the figure, the kefir grain microbiota is composed of a complex and stable consortium of lactic acid bacteria (LAB), acetic acid bacteria (AAB), and yeasts, whose metabolic interactions during fermentation generate a wide array of functional compounds with recognized antimicrobial and immunomodulatory properties. This microbial synergy forms the foundation of kefir’s bioactivity and contributes to the high functional diversity observed across kefir beverages.

Figure 4.

Kefir-Derived Antimicrobial Pathways and Their Potential Contribution to AMR Mitigation. A schematic representation of the antimicrobial and immunomodulatory mechanisms derived from kefir fermentation. The diagram illustrates: (i) the microbial consortium within kefir grains, composed of lactic acid bacteria (LAB), acetic acid bacteria (AAB), and yeasts; (ii) the production of bioactive compounds, including bacteriocins, organic acids, and kefiran; (iii) their molecular targets and biological effects, such as inhibition of pathogenic bacteria, modulation of cytokine production, and suppression of virulence gene expression; and (iv) the systemic outcomes, encompassing microbiota homeostasis, reduced infection severity, and lower antibiotic demand. Together, these processes illustrate how kefir acts as a natural bioreactor generating antimicrobial and immunoregulatory molecules relevant to antimicrobial-stewardship frameworks. Abbreviations: LAB, lactic acid bacteria; AAB, acetic acid bacteria; AMR, antimicrobial resistance.

Figure 4 also highlights the principal bioactive metabolites produced during fermentation, including bacteriocins, organic acids (such as lactic and acetic acid), and kefiran, a unique exopolysaccharide associated with barrier protection and immunomodulatory effects. These compounds exert antimicrobial actions by acidifying the intestinal environment, destabilizing pathogenic cell membranes, and disrupting key cellular processes in antibiotic-resistant organisms. Kefiran has been associated with enhanced colonization resistance and improved epithelial integrity, which are crucial for limiting pathogen invasion and systemic inflammation.

The figure further illustrates how these metabolites influence cellular and molecular targets relevant to AMR prevention:

- (i)

- Inhibition of pathogenic bacteria through acidification, membrane disruption, and organic acid-mediated metabolic suppression;

- (ii)

- Modulation of cytokine responses, reducing inflammatory signaling pathways that otherwise predispose the host to infection; and

- (iii)

- Suppression of virulence gene expression, which diminishes pathogen aggressiveness, biofilm formation, and overall infective capacity.

These mechanistic pathways are ultimately connected to broader systemic outcomes, such as the maintenance of microbiota homeostasis, reduced infection severity, and a lower need for antibiotic interventions. By supporting a resilient gut ecosystem and enhancing mucosal immunity, kefir-derived metabolites help limit the proliferation of resistant pathogens and promote conditions that reduce antibiotic demand. Together, these interconnected processes underscore kefir’s potential role as a complementary, food-based strategy in antimicrobial stewardship and within One-Health AMR mitigation frameworks [34,35,36,37,40,44].

6. Research Gaps and Priorities

Despite growing recognition of probiotic-fermented foods (PFFs) as potential allies in antimicrobial stewardship, critical research gaps limit the translation of mechanistic insights into actionable public-health outcomes. Future investigations should aim to bridge microbiological, clinical, and regulatory dimensions, using standardized and transparent methodologies.

6.1. Randomized Clinical Trials with AMR-Relevant Endpoints

Most existing randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on probiotics or fermented foods assess outcomes such as diarrhea incidence, microbiome composition, or inflammatory markers. Few, however, include AMR-relevant endpoints such as antibiotic prescription frequency, carriage of multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs), or quantitative ARG loads in stool metagenomes [18,20,23,24,45].

Future clinical designs should employ genome-verified PFF formulations, integrate resistome quantification, and link trial metadata with surveillance systems such as WHO GLASS, ensuring results are interpretable within stewardship frameworks [39,40]. Coordinated multicenter trials and open-access data repositories will be essential to establish reproducible evidence connecting PFF consumption with measurable AMR impact.

6.2. Standardized Starter Culture Genomics and Resistome Monitoring

The diversity of microbial consortia used in PFFs, particularly in kefir and kombucha, demands standardized genomic and mobile-element profiling. While current QPS/GRAS frameworks require the absence of transferable resistance genes [34,35,36], there is no unified scoring system to rank starter cultures by mobile-element risk.

Developing such a quantitative resistome risk index could facilitate the certification of ARG-safe starter cultures [30,31,33]. Longitudinal cohort studies combining shotgun metagenomics and resistome tracking after PFF exposure will clarify whether dietary interventions influence ARG abundance or mobility in the gut microbiota [32,37,46]. Integration of these datasets into One-Health AMR dashboards will accelerate translation from bench to policy.

6.3. Mechanistic Studies on Kefir and Kombucha Bioactives

Kefir and kombucha remain underexplored as reservoirs of novel bacteriocins, postbiotics, and Quorum-quenching molecules with potential in AMR mitigation. While in vitro studies show strong antagonism against resistant pathogens, in vivo evidence is limited. Future research should employ metabolomics-guided purification, RNA-seq, and animal infection models to delineate the activity spectra and host interactions of these bioactive compounds [10,13,25,26,47,48,49,50].

Notably, recent works have identified peptide-mediated Quorum-quenching mechanisms that suppress virulence gene expression and biofilm formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Listeria monocytogenes, suggesting potential therapeutic applications beyond food matrices [47,48]. Targeted studies on kefir- and kombucha-derived bacteriocins—such as kefiran peptides and kombucha in could unlock next-generation natural antimicrobials compatible with stewardship principles [49,50].

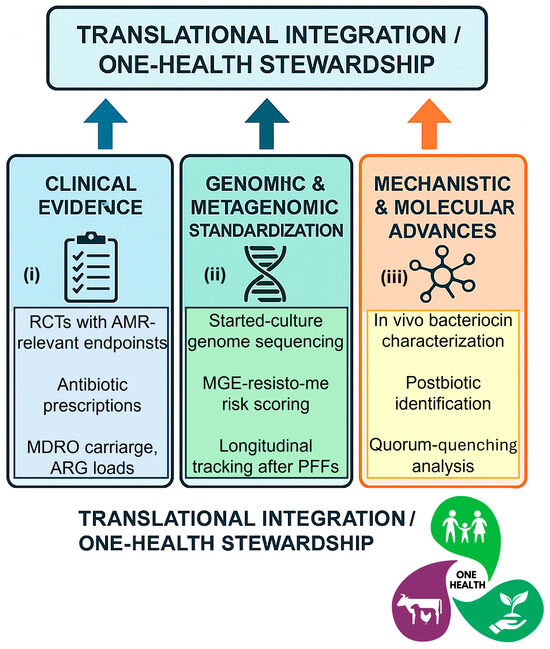

The key research gaps and translational priorities required to integrate probiotic-fermented foods into antimicrobial-stewardship frameworks are conceptually summarized in Figure 5, which outlines the main scientific, technological, and policy-oriented pillars guiding future One-Health research.

Figure 5.

Research and Policy Roadmap for Probiotic-Fermented Foods in Antimicrobial Stewardship. A schematic roadmap summarizing key research priorities and translational steps required to strengthen the evidence base for probiotic-fermented foods (PFFs) in antimicrobial stewardship. The diagram highlights three major pillars: (i) Clinical evidence, calling for randomized controlled trials with AMR-relevant endpoints (antibiotic prescriptions, MDRO carriage, ARG loads); (ii) Genomic and metagenomic standardization, including starter-culture genome sequencing, mobile-element risk scoring, and longitudinal resistome tracking after PFF exposure; and (iii) Mechanistic and molecular advances, focusing on in vivo characterization of bacteriocins, postbiotics, and Quorum-quenching molecules from kefir and kombucha. Together, these pillars define a translational framework bridging microbiome science, safe fermentation technologies, and One-Health policy integration. Abbreviations: PFF, probiotic-fermented foods; AMR, antimicrobial resistance; ARG, antimicrobial-resistance gene; MDRO, multidrug-resistant organism; MGE, mobile genetic element; RCTs, randomized controlled trials.

7. Conclusions

Probiotic-fermented foods (PFFs) represent a scientifically substantiated and sustainable strategy to complement antimicrobial stewardship initiatives. Acting through ecological, molecular, and immunological mechanisms, PFFs promote microbiota resilience, modulate inflammatory responses, and mitigate secondary infections following antibiotic exposure. Clinical evidence, although still heterogeneous, suggests reductions in antibiotic-associated diarrhea, shorter duration of mild respiratory infections, and improved gut microbial diversity among consumers of fermented diets [1,18,20,23,24].

These findings collectively highlight the potential of fermented foods to bridge nutritional microbiology and public-health policy. Nonetheless, their safe and effective translation into clinical and food-system frameworks demands rigorous product standardization, strain-level genomic authentication, and AMR-conscious regulation. Integration of PFFs into global surveillance networks, such as the WHO Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Use Surveillance System (GLASS), will be pivotal for identifying when, where, and for whom these interventions can meaningfully reduce antibiotic demand and resistance trajectories [40,41,42,43,44,45,46].

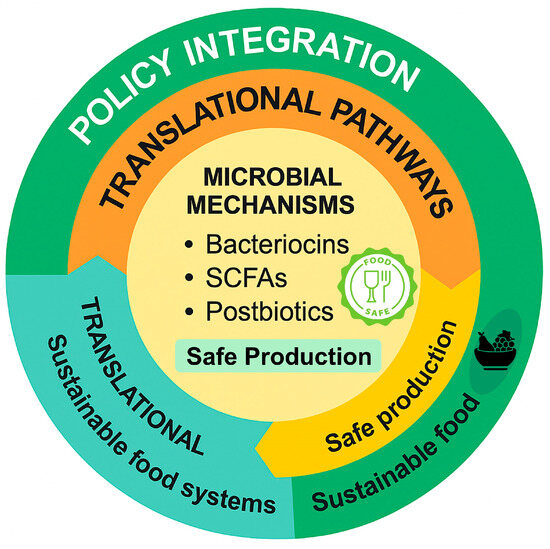

The integrative potential of probiotic-fermented foods within antimicrobial-stewardship frameworks, spanning microbial mechanisms, translational pathways, and policy alignment, is conceptually summarized in Figure 6, which illustrates how sustainable fermentation can be embedded into a One-Health strategy connecting food biotechnology, public-health nutrition, and global antimicrobial-resistance (AMR) mitigation efforts.

Figure 6.

From Fermentation to Stewardship: A One-Health Conceptual Synthesis. A circular conceptual model summarizing the integration of probiotic-fermented foods (PFFs) into antimicrobial-stewardship frameworks. The diagram illustrates three interconnected levels: microbial mechanisms, involving the production of bacteriocins, short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), and postbiotics through safe fermentation; translational pathways, emphasizing sustainable food production and process safety; and policy integration, linking food biotechnology and sustainability with global One-Health strategies. Together, these components outline a forward-looking framework that connects microbial ecology, food systems, and stewardship outcomes.

8. Future Perspectives

Despite substantial progress, the interface between probiotic-fermented foods and antimicrobial resistance remains underexplored. Addressing this gap requires coordinated, multidisciplinary research agendas that unify microbiology, clinical nutrition, and One-Health governance.

Priority directions include:

- Clinical validation: Designing multicenter randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with AMR-relevant endpoints, such as antibiotic-prescription frequency, multidrug-resistant organism (MDRO) carriage, and antimicrobial-resistance gene (ARG) load in stool samples.

- Genomic standardization: Implementing genome-resolved monitoring of starter cultures and consumer microbiomes to ensure the absence of transferable resistance determinants.

- Bioactive discovery: Characterizing bacteriocins, peptides, and Quorum-quenching molecules derived from kefir and kombucha as model systems for next-generation natural antimicrobials [47,48,49,50,51].

- Sustainability and policy: Integrating PFF innovation within circular-bioeconomy frameworks and national AMR action plans to enhance food security, stewardship efficiency, and environmental sustainability.

In the long term, aligning fermentation biotechnology with One Health and planetary-health principles could transform traditional fermented foods into evidence-based biotechnological tools for microbiome restoration, infection prevention, and antibiotic-resistance mitigation. This integration marks a paradigm shift, from reactive medical intervention to preventive microbial stewardship rooted in sustainable nutrition.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to the “Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico, Brazil (CNPq)” and “Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior, Brazil (Capes)”.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| AAD | Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhea |

| AAB | Acetic Acid Bacteria |

| AMC | Antimicrobial Consumption |

| AMR | Antimicrobial Resistance |

| ARG | Antimicrobial-Resistance Gene |

| CFU | Colony-Forming Unit |

| EFSA | European Food Safety Authority |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration (U.S.) |

| GLASS | Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Use Surveillance System |

| GRAS | Generally Recognized as Safe |

| HGT | Horizontal Gene Transfer |

| LAB | Lactic Acid Bacteria |

| MDRO | Multidrug-Resistant Organism |

| MGE | Mobile Genetic Element |

| One Health | Integrated approach linking human, animal, and environmental health |

| PFF | Probiotic-Fermented Foods |

| QPS | Qualified Presumption of Safety |

| RCTs | Randomized Controlled Trials |

| SCFAs | Short-Chain Fatty Acids |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Wastyk, H.C.; Fragiadakis, G.K.; Perelman, D.; Dahan, D.; Merrill, B.D.; Parker, S.C.; Mills, D.A.; Sonnenburg, E.D.; Gardner, C.D.; Sonnenburg, J.L. Gut-Microbiota-Targeted Diets Modulate Human Immune Status. Cell 2021, 184, 4137–4153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leeuwendaal, N.K.; Stanton, C.; O’Toole, P.W.; Beresford, T.P. Fermented Foods, Health and the Gut Microbiome. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rani, P.; Tiwari, S.K. Health Benefits of Bacteriocins Produced by Probiotic Lactic Acid Bacteria. In Developments in Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology: Microbial Biomolecules; Kumar, A., Bilal, M., Ferreira, L.F.R., Kumari, M., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; pp. 97–111. ISBN 978-0-323-99476-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismael, M.; Huang, M.; Zhong, Q. The Bacteriocins Produced by Lactic Acid Bacteria and the Promising Applications in Promoting Gastrointestinal Health. Foods 2024, 13, 3887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yee, C.S.; Zahia-Azizan, N.A.; Abd Rahim, M.H.; Mohd Zaini, N.A.; Raja-Razali, R.B.; Ushidee-Radzi, M.A.; Ilham, Z.; Wan-Mohtar, W.A.A.Q.I. Smart Fermentation Technologies: Microbial Process Control in Traditional Fermented Foods. Fermentation 2025, 11, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco, M.L.; Sanders, M.E.; Gänzle, M.; Arrieta, M.C.; Cotter, P.D.; De Vuyst, L.; Hill, C.; Holzapfel, W.; Lebeer, S.; Merenstein, D.; et al. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) Consensus Statement on Fermented Foods. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, S.A.; Yeboah, P.J.; Ayivi, R.D.; Eddin, A.S.; Wijemanna, N.D.; Paidari, S.; Bakhshayesh, R.V. A Review and Comparative Perspective on Health Benefits of Probiotic and Fermented Foods. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 58, 4948–4964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Anunciação, T.A.; Guedes, J.D.S.; Tavares, P.P.L.G.; de Melo Borges, F.E.; Ferreira, D.D.; Costa, J.A.V.; Umsza-Guez, M.A.; Magalhães-Guedes, K.T. Biological Significance of Probiotic Microorganisms from Kefir and Kombucha: A Review. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Nascimento, A.S.M.; da Silva, R.N.A.; Tavares, P.P.L.G.; Borges, A.S.; Cardoso, M.P.S.; Lobato, A.K.C.L.; Almeida, R.C.C.; Magalhães-Guedes, K.T. Kefir Probiotic-Enriched Non-Alcoholic Beers: Microbial, Genetic, and Sensory-Chemical Assessment. Beverages 2025, 11, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, K.T.; da Silva, R.N.A.; Borges, A.S.; Siqueira, A.E.B.; Puerari, C.; Bento, J.A.C. Smart and Functional Probiotic Microorganisms: Emerging Roles in Health-Oriented Fermentation. Fermentation 2025, 11, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, B.E.; Dutton, R.J. Fermented Foods as Experimentally Tractable Microbial Ecosystems. Cell 2015, 161, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisht, V.; Das, B.; Hussain, A.; Kumar, V.; Navani, N.K. Understanding of Probiotic Origin Antimicrobial Peptides: A Sustainable Approach Ensuring Food Safety. npj Sci Food 2024, 8, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Orozco, B.D.; García-Cano, I.; Jiménez-Flores, R.; Alvárez, V.B. Invited Review: Milk Kefir Microbiota—Direct and Indirect Antimicrobial Effects. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 3703–3715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erginkaya, Z.; Yalanca, İ.; Ünal Turhan, E. Antibiotic Resistance Profile of Lactic Acid Bacteria from Traditional Meat Products. Pamukkale Univ. J. Eng. Sci. 2019, 25, 834–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankarganesh, P.; Bhunia, A.; Kumar, A.G.; Babu, A.S.; Gopukumar, S.T.; Lokesh, E. Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs) in Gut Health: Implications for Drug Metabolism and Therapeutics. Med. Microecol. 2025, 25, 100139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadry, A.A.; El-Antrawy, M.A.; El-Ganiny, A.M. Impact of Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs) on Antimicrobial Activity of New β-Lactam/β-Lactamase Inhibitor Combinations and on Virulence of Escherichia coli Isolates. J. Antibiot. 2023, 76, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.B.; Alimova, Y.; Myers, T.M.; Ebersole, J.L. Short- and Medium-Chain Fatty Acids Exhibit Antimicrobial Activity for Oral Microorganisms. Arch. Oral Biol. 2011, 56, 650–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettocchi, S.; Comotti, A.; Elli, M.; De Cosmi, V.; Berti, C.; Alberti, I.; Mazzocchi, A.; Rosazza, C.; Agostoni, C.; Milani, G.P. Probiotics and Fever Duration in Children with Upper Respiratory Tract Infections: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e250669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarland, L.V.; Hecht, G.; Sanders, M.E.; Goff, D.A.; Goldstein, E.J.C.; Hill, C.; Johnson, S.; Kashi, M.R.; Kullar, R.; Marco, M.L.; et al. Recommendations to Improve Quality of Probiotic Systematic Reviews with Meta-Analyses. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2346872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, C.C.; Lau, M.; Gillespie, D.; Owen-Jones, E.; Lown, M.; Wootton, M.; Calder, P.C.; Bayer, A.J.; Moore, M.; Little, P.; et al. Effect of Probiotic Use on Antibiotic Administration among Care Home Residents: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2020, 324, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco, M.L.; Heeney, D.; Binda, S.; Cifelli, C.J.; Cotter, P.D.; Foligné, B.; Gänzle, M.; Kort, R.; Pasin, G.; Pihlanto, A.; et al. Health Benefits of Fermented Foods: Microbiota and Beyond. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2017, 44, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.R.; Biswas, A.P.; Tasnim, M.; Islam, M.N.; Azam, M.S. Probiotics and Their Applications in Functional Foods: A Health Perspective. Appl. Food Res. 2025, 5, 101193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hempel, S.; Newberry, S.J.; Maher, A.R.; Wang, Z.; Miles, J.N.; Shanman, R.; Johnsen, B.; Shekelle, P.G. Probiotics for the Prevention and Treatment of Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhea: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA 2012, 307, 1959–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, W.; Chen, C.; Wen, T.; Zhao, Q. Probiotics for the Prevention of Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhea in Adults: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trials. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2021, 55, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Souza Silva, A.R.; Peres, A.P.; dos Santos Martins, R.A.; Magalhães, K.T.; Puerari, C.; Morzelle, M.C.; Bento, J.A.C. The Addition of Plantain Peel (Musa paradisiaca) to Fermented Milk as a Strategy for Enriching the Product and Reusing Agro-Industrial Waste. Beverages 2025, 11, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, K.T.; Pereira, M.A.; Dragone, G.; Nicolau, A.; Domingues, L.; Teixeira, J.A.; Silva, J.B.A.; Schwan, R.F. Production of Fermented Cheese Whey-Based Beverage Using Kefir Grains as Starter Culture: Evaluation of Morphological and Microbial Variations. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 8843–8850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yassin, L.S.; Sheleidres, C.G.; Fischer, T.E.; Zielinski, A.A.F.; Los, P.R.; Lacerda, L.G.; Alberti, A.; Nogueira, A. Development of Smoothies Fermented with Kombucha Microorganisms: Sensory Characteristics, Functional Properties, and Microbiological Aspects. Fermentation 2025, 11, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, E.N.; Magalhães-Guedes, K.T.; Borges, F.E.M.; Ferreira, D.D.; da Silva, D.F.; Conceição, P.C.G.; Lima, A.K.C.; Cardoso, L.G.; Umsza-Guez, M.A.; Ramos, C.L. Probiotic Microorganisms in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: Live Biotherapeutics as Food. Foods 2024, 13, 4097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães-Guedes, K.T.; Borges, A.S.; Almeida da Silva, R.N. A Conceptual Framework for Understanding the Interaction between Smart Probiotics and the Gut–Brain Axis in Mood Regulation: An Integrative Approach. Int. J. Appl. Sci. Res. 2025, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinayamohan, P.G.; Salihu, S.; Kalia, V.C. Fermented Foods as a Potential Vehicle of Antimicrobial-Resistant Bacteria and Genes. Fermentation 2023, 9, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, B.E. Are Fermented Foods an Overlooked Reservoir of Antimicrobial Resistance? Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2023, 51, 101018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Fu, S.; Klein, M.S.; Wang, H. High Prevalence of Antibiotic Resistance in Traditionally Fermented Foods as a Critical Risk Factor for Host Gut Antibiotic Resistome. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leech, J.; Cabrera-Rubio, R.; Walsh, A.M.; Macori, G.; Walsh, C.J.; Barton, W.; Finnegan, L.; Crispie, F.; O’Sullivan, O.; Claesson, M.J.; et al. Fermented-Food Metagenomics Reveals Substrate-Associated Differences in Taxonomy and Health-Associated and Antibiotic Resistance Determinants. mSystems 2020, 5, e00522-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allende, A.; Alvarez-Ordóñez, A.; Bortolaia, V.; Bover-Cid, S.; De Cesare, A.; Dohmen, W.; Guillier, L.; Jacxsens, L.; Nauta, M.; Mughini-Gras, L.; et al. Update of the List of Qualified Presumption of Safety (QPS) Recommended Microbiological Agents Intentionally Added to Food or Feed as Notified to EFSA 22: Suitability of Taxonomic Units Notified to EFSA Until March 2025. EFSA J. 2025, 23, e9510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). GRAS Notice (GRN) No. 1084: Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus KCTC 12202BP (CBT LR5)—Agency Response Letter. 2023. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/177326/download (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). GRAS Notice (GRN) No. 1143: Bacillus subtilis NRRL 68053—Agency Response Letter (with Amendments). 2024. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/179728/download (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Whole-Genome Sequencing in Foodborne Outbreaks and Food Safety Investigations. 2025. Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/topics/topic/whole-genome-sequencing-foodborne-outbreaks (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Zhang, E.; Breselge, S.; Carlino, N.; Segata, N.; Claesson, M.J.; Cotter, P.D. A Genomics-Based Investigation of Acetic Acid Bacteria across a Global Fermented Food Metagenomics Dataset. iScience 2025, 28, 112139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). The Role of Nutrition and Microbiome in Antimicrobial Resistance Mitigation: A One-Health Perspective; WHO AMR Division: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Use Surveillance System (GLASS) Report 2025; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240116337 (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Castellano, P.; Melian, C.; Burgos, C.; Vignolo, G. Bioprotective Cultures and Bacteriocins as Food Preservatives. In Advances in Food and Nutrition Research; Toldrá, F., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; Volume 106, pp. 275–315. ISBN 978-0-443-19304-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, D.K.; Thakur, M.; Singh, S.; Tripathy, S.; Gupta, A.K.; Baranwal, D.; Patel, A.R.; Shah, N.; Utama, G.L.; Niamah, A.K.; et al. Bacteriocins as Antimicrobial and Preservative Agents in Food: Biosynthesis, Separation and Application. Food Biosci. 2022, 46, 101594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djordjevic, S.P.; Jarocki, V.M.; Seemann, T.; Kidd, T.J. Genomic Surveillance for Antimicrobial Resistance—A One Health Perspective. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2024, 25, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). The European Union Summary Report on Antimicrobial Resistance in Zoonotic and Indicator Bacteria from Humans, Animals and Food in 2022–2023. EFSA J. 2025, 23, e9237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredriksen, S.; de Warle, S.; van Baarlen, P.; Boekhorst, J.; Wells, J.M. Resistome Expansion in Disease-Associated Human Gut Microbiomes. Microbiome 2023, 11, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, A.M.; Leech, J.; Huttenhower, C.; Delhomme-Nguyen, H.; Crispie, F.; Chervaux, C.; Cotter, P.D. Integrated Molecular Approaches for Fermented Food Microbiome Research. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2023, 47, fuad001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, P.M.; Kuniyoshi, T.M.; Oliveira, R.P.S.; Hill, C.; Ross, R.P.; Cotter, P.D. Antimicrobials for Food and Feed: A Bacteriocin Perspective. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2020, 61, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kameswaran, S.; Gujjala, S.; Zhang, S.; Kondeti, S.; Mahalingam, S.; Bangeppagari, M.; Bellemkonda, R. Quenching and Quorum Sensing in Bacterial Biofilms. Res. Microbiol. 2024, 175, 104085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meleti, E.; Koureas, M.; Manouras, A.; Giannouli, P.; Malissiova, E. Bioactive Peptides from Dairy Products: A Systematic Review of Advances, Mechanisms, Benefits, and Functional Potential. Dairy 2025, 6, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziemlewska, A.; Nizioł-Łukaszewska, Z.; Zagórska-Dziok, M.; Mokrzyńska, A.; Krupski, W.; Wójciak, M.; Sowa, I. Anti-Aging, Anti-Inflammatory, and Cytoprotective Properties of Lactobacillus- and Kombucha-Fermented C. pepo L. Peel and Pulp Extracts with Prototype Skin Toner Development. Molecules 2025, 30, 4082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Fátima Dantas Linhares, M.; Fonteles, T.V.; de Oliveira, L.S.; de Souza, S.B.; de Castro Miguel, E.; Fernandes, F.A.N.; Rodrigues, S. Powdered Kombucha Flavored with Fruit By-Products: A Sustainable Functional Innovation. Processes 2025, 13, 3020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).