Abstract

The development of plant-based synbiotic beverages is gaining increasing attention as consumers seek sustainable, functional alternatives to dairy products. This preliminary study investigated the fortification of tibicos (water kefir) with lemon catnip (Nepeta cataria var. citriodora) hydrolate, an aromatic distillation byproduct rich in bioactive terpenoids. After 72 h-fermentation of tibicos, physicochemical, microbiological, health-promoting and sensory parameters were evaluated. Both control and fortified beverages exhibited typical fermentation kinetics, including a decrease in pH, reduction of soluble solids, and accumulation of organic acids. Lactic acid bacteria count remained stable, while yeast proliferation was slightly reduced in the hydrolate-fortified sample, consistent with the known yeast-sensitive nature of certain hydrolate-derived terpenoids. Importantly, hydrolate fortification significantly enhanced antioxidant capacity (DPPH: +34%; ABTS: +39%; RP: +38%). Enzyme-inhibitory activities also increased significantly in the hydrolate-fortified samples (α-Amylase and α-Glucosidase inhibition rates increased by 9% and 11%, respectively). ACE inhibition similarly increased from 32% to 44%, indicating an enhanced antihypertensive potential. HMG-CoA reductase inhibition increased from 31% to 42%, showing improved hypolipidemic activity. Sensory evaluation indicated improved sensory acceptability, imparting citrus–floral notes that balanced the acidic profile of tibicos. These findings highlight the potential of valorizing lemon catnip hydrolate as a functional fortifier in non-dairy synbiotic beverages.

1. Introduction

In recent years, there has been a growing consumer demand for plant-based fermented beverages endowed with functional properties, particularly those combining probiotic and prebiotic components to form synbiotics [1]. Among these, water kefir (tibicos) represents a refreshing non-dairy option featuring a synbiotic community of bacteria and yeasts that ferment a sugar-based substrate into a mildly acidic, lightly carbonated beverage. Tibicos grains are known to produce metabolites such as organic acids, ethanol, and exopolysaccharides, with potential health-promoting effects, including anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antioxidant, and antidiabetic properties, though human clinical studies remain scarce [2,3]. Moreover, the composition of water kefir varies considerably depending on the origin of the grains, fermentation substrate, and environmental conditions. This variability underscores the opportunity, and challenge of enhancing water kefir’s functional and sensory attributes through controlled fortification strategies [4].

One promising fortifying agent is the hydrolate derived from lemon catnip (Nepeta cataria var. citriodora). This plant originates from Western Europe but is now distributed worldwide, thanks to its decorative qualities, unique citrus and floral scent, and promising bioactive properties [5]. These properties are attributed to its flavonoids, phenolic acids, steroids, terpenoids, and volatile compounds, which exhibit a wide range of activities, including antioxidative, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, anti-nociceptive, and spasmolytic effects [6]. Nowadays, lemon catnip has been introduced into horticulture and is commonly cultivated as a medicinal and spice plant, as well as an essential oil-bearing crop, although its full potential remains underutilized [7]. Practically, this plant could serve as a highly profitable substitute for lemon balm (Melissa officinalis) due to its very similar aroma and a significantly higher essential oil yield [8]. Hydrolates are aqueous byproducts of essential oil distillation and may retain water-soluble volatile compounds absent or diminished in the corresponding essential oil [9,10]. A recent study revealed that both essential oil and hydrolate-derived recovery oil from lemon catnip are largely composed of terpene alcohols, especially nerol and geraniol, along with citral isomers such as geranial and neral, all exhibiting significant variations across seasons [11]. Furthermore, essential oils of lemon catnip demonstrate biological activities such as antimicrobial, antioxidant, antihyperglycemic, and anti-inflammatory effects [8]. These properties position lemon catnip hydrolate as a valorized byproduct with functional potential in fermented foods.

Nevertheless, to date there appears to be no literature combining the use of tibicos (water kefir) with lemon catnip hydrolate in a synbiotic beverage format. Therefore, this study provides the first comprehensive evaluation of how fortifying tibicos with lemon catnip hydrolate influences its physicochemical, microbiological, functional, and sensory characteristics, thereby providing proof of concept for the development of hydrolate-enhanced synbiotic beverages. The primary aim is to perform a preliminary assessment of a plant-based synbiotic beverage, produced by fermenting tibicos grains in the presence of lemon catnip hydrolate, and to evaluate its fermentation performance, microbial dynamics, functional bioactivity, and sensory characteristics.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials

2.1.1. Tibicos Grains

Tibicos grains (water kefir culture) were obtained from a local household source in Serbia, previously maintained in sucrose solution and refreshed weekly. The grains were maintained under stable conditions and standardized through pre-fermentation cycles. The culture was verified for microbial consistency prior to use and cryopreserved for reproducibility. Prior to experiments, the grains were activated by two fermentation cycles in sterile 10% (w/v) sucrose solution at 25 °C.

2.1.2. Lemon Catnip Hydrolate

Lemon catnip (N. cataria var. citriodora) was cultivated at the Institute of Field and Vegetable Crops, Novi Sad, on the experimental field in Bački Petrovac (voucher specimens are deposited in the BUNS Herbarium under number 2-1401). The plants were harvested at full bloom and distilled using a pilot scale stainless steel distillation unit. In brief, a stainless-steel distillation vessel with a volume of 0.8 m3 is filled with approximately 30 kg of lemon catnip, closed with a stainless-steel lid, and supplied with externally generated water vapor [7]. After passing the steam through the plant material, the volatile components are collected in a Florentine bottle via the condenser and cooler system, where the essential oil separates and floats on the surface of the water phase, forming the so-called hydrolate [12]. After decanting the essential oil, the main product, the remaining hydrolate, considered a by-product, was filtered through filter paper and stored in sterile plastic containers at 4 °C.

2.2. Profiling of Volatile Organic Compounds

Prior to the analysis, simultaneous steam distillation and extraction with dichloromethane using the Likens–Nickerson apparatus were performed to recover volatile organic compounds (VOCs) from the hydrolate (also known as secondary oil) [13]. VOC profiling from the hydrolate was carried out using gas chromatography—mass spectrometry (GC–MS) systems (Agilent 7890A GC (Santa Clara, CA, USA)) equipped with a flame ionization detector (FID), and Agilent 5973 GC (Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with a mass selective detector (MSD)), coupled with a nonpolar HP-5MS fused-silica capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm i.d., 0.25 μm film thickness) (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The GC–MS results consist of retention times (RT) and retention indices (RI) relative to an n-alkane series (C8–C24), as referenced in the NIST and Wiley mass spectral libraries [7].

2.3. Experimental Design

Two experimental groups were prepared:

- control (C) (traditional tibicos fermentation) and

- hydrolate-fortified (H) (tibicos fermentation with lemon catnip hydrolate instead of water).

Each group was set up in triplicate in sterile 500 mL Erlenmeyer flasks, containing 250 mL fermentation medium inoculated with 10% (w/v) tibicos grains. Fermentation was carried out at 25 °C for 72 h under static conditions. Samples were collected at 0, 24, 48, and 72 h for analyses. The fermentation substrate was prepared using a 10% (w/v) sucrose solution in which the entire water component was replaced with lemon catnip hydrolate. Thus, hydrolate was used at 100% of the liquid phase (i.e., 100 mL hydrolate per 100 mL substrate), with no additional dilution. The hydrolate-based sucrose solution was prepared fresh prior to inoculation with tibicos grains. For physicochemical analyses during fermentation, the following parameters were monitored in whole beverage samples: pH value, soluble solids and titratable acidity. pH was measured using a calibrated digital pH meter Mettler Toledo (ArtisanTG™, Greifensee, Switzerland). Soluble solids (°Brix) were determined using a handheld refractometer (Atago, Minato, Japan). Titratable acidity was quantified by titration with 0.1 M NaOH, expressed as g lactic acid/100 mL. Additionally, microbial counts were determined using standard spread plate methods [14,15,16,17,18,19]. In brief, lactic acid bacteria (LAB) were determined on De Man–Rogosa–Sharpe (MRS) agar (HiMedia, Mumbai, India), incubated anaerobically at 30 °C for 48 h, while yeasts were defined on Yeast Extract Peptone Dextrose (YPD) agar (HiMedia, Mumbai, India) with chloramphenicol (100 mg/L) (HiMedia, Mumbai, India), incubated at 28 °C for 48 h. The number of acetic acid bacteria (AAB) was determined using Glucose Yeast Extract Calcium Carbonate (GYC) agar (HiMedia, Mumbai, India), incubated aerobically at 30 °C for 72 h. Results were expressed as log CFU/mL.

2.4. Bioactivity-Related and Health-Promoting Potentials

Tibicos samples were centrifuged at 5000–6000× g by centrifuge (Eppendorf 5804R, Hamburg, Germany) for 10 min at 4 °C to remove residual microbial cells and suspended solids. The clarified supernatants were collected and, where required, sterile-filtered (0.22–0.45 µm) to minimize microbial enzymatic interference. For all tests related to bioactivity and health-promoting potentials, cell-free supernatants were used. All chemicals and standards for health-promoting assays were purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany).

2.4.1. Antioxidant Assays

For antioxidant assays involving organic solvents, methanolic extracts were prepared by mixing the supernatant with 80% methanol in a 1:1 ratio, followed by centrifugation. In addition, aliquots of the beverage were lyophilized to determine dry matter content, enabling expression of results on both a beverage volume and dry weight basis. The antioxidant capacity of tibicos was evaluated using DPPH•, ABTS•+, and reducing power (RP) assays described by Ranitović et al. [19]. For the DPPH• assay, clarified methanolic extracts were incubated with a methanolic DPPH• solution, and the decrease in absorbance was measured at 515 nm after incubation in the dark. Radical scavenging capacity was expressed as mmol Trolox equivalents (TE) per 100 mL of beverage and per 100 g dry matter. ABTS•+ radical cations were generated by the reaction of ABTS with potassium persulfate and adjusted to an initial absorbance of 0.70 at 734 nm. Tibicos supernatant was then added, and the reduction in absorbance was measured after incubation, with antioxidant capacity similarly expressed in Trolox equivalents. The reducing power was determined by monitoring the reduction of potassium ferricyanide in the presence of tibicos samples, followed by complexation with ferric chloride, with absorbance measured at 700 nm. All assays included appropriate reagent blanks and matrix controls to correct for turbidity or intrinsic sample color.

2.4.2. Antidiabetic Assays

The antidiabetic potential of tibicos was assessed through inhibition of α-amylase and α-glucosidase [20,21]. In the α-amylase assay, tibicos supernatants were pre-incubated with the enzyme prior to the addition of starch substrate. Reducing sugars released were quantified using the dinitrosalicylic acid (DNSA) method, with absorbance read at 540 nm. Inhibition was expressed as a percentage relative to the enzyme control and converted to mg acarbose equivalents (ACAE) per g dry matter using an acarbose calibration curve. The α-glucosidase inhibitory activity was determined using p-nitrophenyl α-D-glucopyranoside (pNPG) as a substrate. After incubation with the enzyme and tibicos extracts at 37 °C, the reaction was terminated with sodium carbonate, and the release of p-nitrophenol was measured at 400 nm. Inhibition rates were calculated against controls and expressed as ACAE/g dry matter.

2.4.3. Antihypertensive Assay

The antihypertensive potential was evaluated through inhibition of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE). Tibicos samples, pre-adjusted to pH 8.3 to avoid nonspecific inhibition by organic acids, were incubated with ACE, followed by the addition of hippuryl-histidyl-leucine (HHL) substrate [17]. The reaction was terminated with hydrochloric acid, and the resulting hippuric acid was extracted with ethyl acetate, evaporated, and re-dissolved in water. Quantification was performed spectrophotometrically at 228 nm, with captopril used as the reference inhibitor. For the ACE inhibitory assay, samples were adjusted to pH 8.3. All samples were centrifuged to remove solids prior to analysis.

2.4.4. Antihypercholesterolemic Assay

The potential antihypercholesterolemic activity of tibicos was investigated by measuring inhibition of HMG-CoA reductase (HMGR) as in the research of Rachmawati et al. [22] and Lee et al. [23]. Reaction mixtures containing NADPH, HMG-CoA, and HMGR enzyme were incubated with tibicos extracts at 37 °C, and the decline in NADPH absorbance at 340 nm was recorded kinetically over 10 min. The rate of NADPH oxidation in the presence of tibicos was compared to control reactions to calculate inhibition rates, and results were expressed as percentage inhibition and, where possible, as IC50 values. For the HMG-CoA reductase assay, samples were adjusted to pH 7.4 according to the kit protocol. All samples were centrifuged to remove solids prior to analysis.

2.4.5. Anti-Inflammatory Assay

The anti-inflammatory potential was determined using the protein denaturation assay with egg albumin [24]. Tibicos samples were incubated with albumin in phosphate buffer at pH 6.4, followed by heat treatment at 70 °C. After cooling, the absorbance was measured at 660 nm, and the degree of inhibition of protein denaturation was calculated relative to controls. Diclofenac or aspirin was used as a positive reference standard. All analyses were performed in triplicate using independent tibicos fermentations. Results were corrected for matrix interferences by including appropriate blanks and were expressed both in terms of beverage volume (per 100 mL) and normalized to dry matter (per 100 g DM).

2.5. Sensory Evaluation

The sensory evaluation was designed to examine the influence of hydrolate on tibicos, combining descriptive analysis with consumer testing (Table 1) [25]. The protocol followed established ISO standards for sensory panel training [26] and hedonic evaluation [27]. A trained panel of twelve assessors (6 males, 6 females; aged 23–45 years; non-smokers) participated in three 90 min training sessions to establish a lexicon, calibrate reference standards, and practice intensity scaling according to Quantitative Descriptive Analysis [28]. The finalized sensory vocabulary comprised aroma descriptors (citrus–lemon, citronella/lemongrass, floral, herbal-green, yeasty/fermented, and acetic/vinegary), flavor descriptors (sweetness, sourness, bitterness, citrus, floral), and mouthfeel/aftertaste descriptors (effervescence, astringency, citrus persistence, acid persistence). Control tibicos (C) and hydrolate-fortified tibicos (H) were served in 150 mL ISO glasses coded with three-digit random numbers and presented in balanced order using a Williams Latin square design [29]. Ratings were recorded on unstructured 10-point line scales, and evaluations were replicated across two sessions.

Table 1.

Summary of panelist information and sensory evaluation parameters [13,26,27,28].

Consumer acceptability was assessed with 20 untrained consumers (10 males, 10 females; aged 20–55 years), recruited among regular fermented beverage users. Samples were served under identical conditions as in the descriptive analysis. Participants evaluated overall impression, aroma, flavor, mouthfeel, and aftertaste on 9-point hedonic scales (1 = dislike extremely; 9 = like extremely), as recommended in sensory studies of fermented beverages [30,31]. Purchase intent was rated on a 5-point scale (1 = would definitely not buy; 5 = would definitely buy). To identify drivers of liking, Just-About-Right (JAR) scaling was applied for sweetness, sourness, citrus intensity, floral intensity, effervescence, and yeasty character using a 3-point scale (“too low,” “just right,” “too high”) [13].

Descriptive data were analyzed using linear mixed-effects models with treatment as a fixed effect and panelist and session as random effects. Consumer hedonic data were compared using paired t-tests, and effect sizes were calculated as Cohen’s dz. Penalty analysis was applied to JAR data, where attributes with ≥20% of responses outside “just right” and associated penalties ≥0.75 hedonic units were flagged as critical, following established sensory evaluation practice in functional and fermented beverages [29,30].

2.6. Statistical Analysis

All experimental data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and inferential tests to evaluate the effects of hydrolate fortification [31]. Fermentation kinetics were modeled using a four-parameter sigmoidal equation of the form Equation (1).

where a and d denote the lower and upper asymptotes, c represents the inflexion point, expressed in hours, corresponding to the maximum rate of change, and b is the slope (steepness) parameter. Model performance was validated through the coefficient of determination (R2), root mean square error (RMSE), and skewness [13]. For fermentation kinetics, the sigmoidal model was fitted to all individual replicate measurements at each sampling time. R2 and RMSE were calculated from these individual data points to reflect experimental variability. For this modeling, CFU values were first log10-transformed to stabilize variance and linearize the exponential region of the curve. The model was fitted to the log-transformed data, where parameter ‘d’ represents the upper asymptote of the log10 CFU curve (final population level). Thus, the fitted ‘d’ parameter corresponds to the predicted maximum log CFU per mL during fermentation. Model fitting was performed directly on log-transformed data, and no back-transformation was applied when presenting parameter estimates. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied to assess significant differences (p < 0.05) among treatments for all bioactivity parameters. Post hoc pairwise comparisons were performed using Tukey’s HSD test. Sensory data were processed using linear mixed-effects models with treatment as a fixed factor and panelist/session as random effects, while JAR data were interpreted through penalty analysis. All analyses were performed in IBM SPSS Statistics 27.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and visualized in Microsoft Excel 2021 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA).

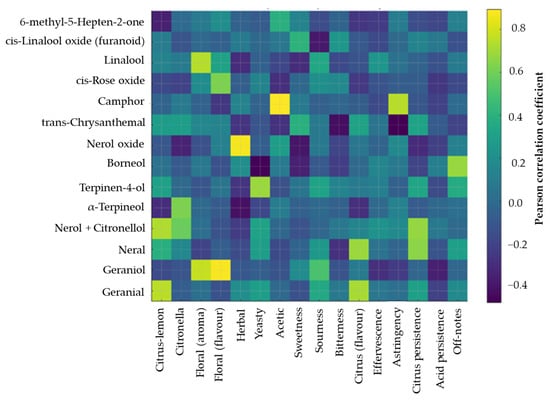

To investigate the relationship between the volatile profile of the lemon catnip hydrolate and the sensory characteristics of the tibicos beverages, a multivariate correlation analysis was performed. A set of 14 volatile compounds identified by GC–MS (6-methyl-5-hepten-2-one, cis-linalool oxide, linalool, cis-rose oxide, camphor, trans-chrysanthemal, nerol oxide, borneol, terpinen-4-ol, α-terpineol, nerol + citronellol, neral, geraniol and geranial) were compared with the 16 QDA sensory attributes, organized into aroma (citrus–lemon, citronella, floral aroma, herbal, yeasty, acetic, off-notes), flavor (sweetness, sourness, bitterness, citrus flavor, floral flavor) and mouthfeel/aftertaste descriptors (effervescence, astringency, citrus persistence, acid persistence). Volatile compound peak areas were standardized prior to analysis, and sensory attribute scores were averaged across panelists. Pearson correlation coefficients were then calculated for all volatile–sensory pairs, resulting in a 14 × 16 correlation matrix. The matrix was visualized as a heatmap generated using Python (Matplotlib, version 3.10.7.), with color intensity representing the strength and direction of correlations.

3. Results and Discussion

To explain the rationale for fortifying tibicos with lemon catnip hydrolate, its volatile composition was first analyzed by GC–MS (Table 2, Supplementary Figure S1). The hydrolate exhibited a profile dominated by oxygenated monoterpenes, with nerol + citronellol (54.3%) and geraniol (29.4%) as the major constituents. Other notable compounds included neral (3.8%) and geranial (2.9%), together representing the citral isomers, along with minor levels of linalool (1.9%), borneol (0.7%), terpinen-4-ol (0.6%), and trace amounts of rose oxide, camphor, and chrysanthemal. Lemon catnip hydrolate possesses a pleasant sweet, citrus, and floral odor and flavor, which can be attributed to the monoterpene alcohols nerol, geraniol, and citronellol, as clearly shown in Table 2 [7]. Collectively, these volatiles confer citrus, lemon-like, and floral/geranium-like notes, which correspond well with the sensory descriptors later observed in fortified tibicos.

Table 2.

Volatile composition of lemon catnip hydrolate.

This profile is in line with previous studies describing lemon catnip, which is particularly rich in geraniol, citronellol, and citral derivatives [7,32,33]. Importantly, these compounds are not only responsible for desirable aromatic qualities but also possess documented bioactive functions: geraniol and citronellol are known antimicrobials with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities, while citral and linalool have been studied for their capacity to modulate microbial growth and contribute to radical scavenging activity [33]. This dual role, sensory enhancement and functional potential, makes the hydrolate an attractive candidate for beverage fortification [34]. The use of aromatic plants and their derivatives to enrich fermented beverages is increasingly recognized as a promising strategy to bridge consumer expectations for natural flavors with demands for health-promoting functionality [35]. Recent studies have explored the incorporation of hibiscus, green tea, rose, mint, and other botanicals into kombucha and kefir-type beverages, showing that such fortification can both mask excessive acidic or yeasty notes and introduce bioactive molecules that strengthen antioxidant and metabolic regulatory properties [34,36,37,38,39]. Hydrolates, as by-products of essential oil distillation, represent a sustainable and underexplored option in this context [7]. Their water solubility, mild aromatic intensity, and bioactive content make them particularly suitable for application in aqueous, low-alcohol matrices such as tibicos.

3.1. Fermentation Kinetics and Physicochemical Evaluation

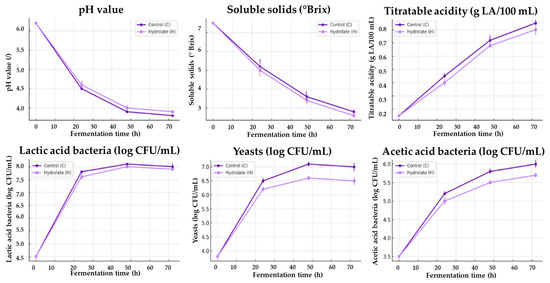

During the 72 h fermentation period, both control and hydrolate-fortified tibicos followed the characteristic dynamics expected for water kefir beverages (Figure 1). The pH dropped rapidly within the first 24 h, falling from an initial value of ~6.2 to around 4.5, and then declined more gradually toward ~3.7–3.8 by the end of fermentation. This acidification pattern is consistent with reports on water kefir and other lactic fermentations, where early lactic acid production is followed by a stabilization phase once microbial activity levels off [9,14,15]. The addition of lemon catnip hydrolate did not substantially alter the pH trajectory, though a slightly higher final pH was observed. This slight pH difference likely reflects variations in acid production dynamics during fermentation rather than indicating any specific buffering or antimicrobial effect.

Figure 1.

Fermentation kinetics of tibicos beverages during 72 h fermentation of control tibicos (dark purple line) and tibicos fortified with lemon catnip hydrolate (light purple line).

In parallel with the decrease in pH, soluble solids were steadily consumed. Starting from 7.5 °Brix, both control and fortified samples dropped to 3.0–2.6 °Brix by 72 h, reflecting efficient sugar metabolism by the mixed microbial consortium. Literature on water kefir fermentation typically reports sugar reductions of 50–70% within 48–72 h, which is very much in line with these findings [4]. Interestingly, the hydrolate-fortified sample showed a slightly slower sugar depletion, which could indicate mild inhibition of yeast activity by volatile compounds present in the hydrolate.

Titratable acidity mirrored these changes, increasing from a baseline of 0.15 g lactic acid/100 mL to nearly 0.8–0.9 g/100 mL by 72 h. The steepest rise occurred between 24 h and 48 h, consistent with the period of most intensive lactic acid bacterial metabolism. The fortified tibicos displayed a comparable acidity increase but with a slightly sharper slope, suggesting that the hydrolate may have promoted acid production efficiency despite modestly suppressing sugar utilization. This dual effect is reminiscent of findings in other fortified kefir-like systems, where plant extracts modulated microbial interactions rather than simply enhancing or inhibiting growth [15]. The progressive increase in organic acids over time closely mirrored the pH drop, indicating that acid accumulation was the primary driver of acidification. From a microbiological perspective, lactic acid bacteria are the main producers of lactic acid, whereas acetic acid bacteria oxidize yeast-derived ethanol to acetic acid. As can be seen in Figure 1, LAB reached similar final levels in both control and hydrolate-fortified tibicos, suggesting comparable lactic acid formation, while yeasts showed a modest but consistent reduction in the hydrolate treatment. This pattern is compatible with the slight differences in acetic character and acidity persistence between treatments. A slightly lower yeast activity would be expected to reduce ethanol supply for acetic acid bacteria, potentially moderating acetic acid accumulation and therefore the sharp, vinegar-like component of acidity.

3.2. Microbial Growth Dynamics

Microbial enumeration confirmed the observed biochemical trends. Lactic acid bacteria reached densities above 8 log CFU/mL within 48 h in both samples, demonstrating robust growth and dominance during fermentation. Yeasts followed a similar trajectory, rising from 3.8 log CFU/mL initially to 7 log CFU/mL at 72 h, though slightly lower values were recorded in the hydrolate-fortified batch. Acetic acid bacteria also proliferated steadily, though again the hydrolate sample displayed a modest reduction in final cell counts compared with the control. Such patterns are consistent with earlier studies showing that phenolic-rich plant extracts can selectively inhibit certain yeast and acetic acid bacteria while leaving lactic acid bacteria relatively unaffected [16]. The observed growth patterns of LAB, yeasts, and AAB showed the expected sequential proliferation typical of tibicos ecosystems. LAB dominated early growth, followed by yeasts and finally AAB. This succession is consistent with established microbial interactions in fermented beverages such as kombucha, kefir, and water kefir, where LAB initiate acidification, yeasts contribute ethanol and CO2, and AAB convert ethanol to acetic acid [40]. Hydrolate fortification did not suppress microbial development. LAB reached approximately 8 log CFU/mL in both treatments, yeast counts stabilized around 7 log CFU/mL, and AAB reached 6–6.5 log CFU/mL. The comparable microbial concentrations with traditional tibicos indicate that the hydrolate matrix did not adversely influence microbial viability but may have slightly shifted metabolic balance, which is consistent with the physicochemical observations. Fermentation kinetics observed here are highly comparable to published profiles of water kefir, with rapid acidification, strong lactic acid bacterial growth, and efficient sugar depletion. The integration of N. cataria hydrolate only slightly altered these dynamics, moderating yeast and acetic acid bacterial expansion while maintaining robust lactic fermentation. This indicates that hydrolate addition can provide functional enhancement without disrupting the core fermentation process, a balance that has been emphasized as crucial in the development of novel synbiotic beverages [17,26,41]. Additionally, the kinetic modelling using the four-parameter sigmoid function provided a description of the fermentation curves, with R2 values close to 1 and negligible RMSE across all parameters (Table 3).

Table 3.

Fermentation kinetic parameters and verification of the obtained models.

It should be noted that the present microbiological analysis quantified only the total populations of lactic acid bacteria, yeasts, and acetic acid bacteria, without identifying the dominant species or their succession patterns. These counts are sufficient to describe overall fermentation performance and to compare the effect of hydrolate addition, but the lack of species-level resolution limits the ability to attribute specific biochemical changes, such as organic acid dynamics or volatile formation, to particular microbial taxa.

For pH value, the estimated lower asymptotes were 3.748 for the control and 3.848 for the hydrolate-fortified tibicos, aligning well with the observed final values after 72 h. The calculated inflection points around 18 h confirm that the most intensive acidification occurs within the first day, which corresponds with typical water kefir fermentation kinetics described by Laureys and De Vuyst [14]. The modelling of soluble solids depletion indicated final asymptotes of ~1.3 °Brix for the control and ~1.0 °Brix for the hydrolate sample, reflecting complete sugar utilization. The inflection points (c ≈ 33–34 h) suggest that substrate consumption accelerates during the mid-fermentation phase. Similar sugar consumption dynamics, with midpoint depletion between 24 h and 36 h, have been reported in water kefir and kombucha systems [17]. Titratable acidity increased sharply after 24 h, with fitted asymptotes of 1.035 g/100 mL (control) and 0.922 g/100 mL (hydrolate). Notably, the hydrolate sample showed a higher shape parameter (b = 2.193 vs. 1.819), implying a more rapid acidification after the lag phase. Such accelerated acidification in plant-fortified fermentations has been linked to the stimulatory effects of certain phenolic compounds on lactic acid bacteria [42,43]. Microbial growth curves were also captured accurately. Lactic acid bacteria and yeasts reached upper asymptotes of approximately 8.0 and approx. 7.0 log CFU/mL, respectively, with very steep shape parameters (b = 10), reflecting the abrupt transition from lag to exponential growth. This sharp onset mirrors microbial dynamics reported in other mixed lactic-yeast fermentations [44]. Acetic acid bacteria increased more gradually, reaching asymptotes of 6.249 log CFU/mL (control) and 6.051 log CFU/mL (hydrolate), with lower b values (1.3–1.6). This indicates a slower, progressive growth pattern that is typical for acetic acid bacteria in synbiotic fermentations [18]. The growth modeling applied to log-transformed CFU values showed well-defined upper asymptotes (d values), confirming that both treatments achieved stable microbial populations typical of mature fermentation. The gained results demonstrate that hydrolate acts as a compatible additive that does not impair the core microbial ecology of tibicos.

The kinetic modelling confirms that the fermentation of both control and hydrolate-fortified tibicos follows classical microbial and metabolic dynamics, with rapid early acidification, mid-phase sugar consumption, and stabilization of microbial populations by the end of the process. The addition of lemon catnip hydrolate slightly shifted the inflection points and moderated yeast and acetic acid bacterial growth, but without disrupting the overall fermentation trajectory.

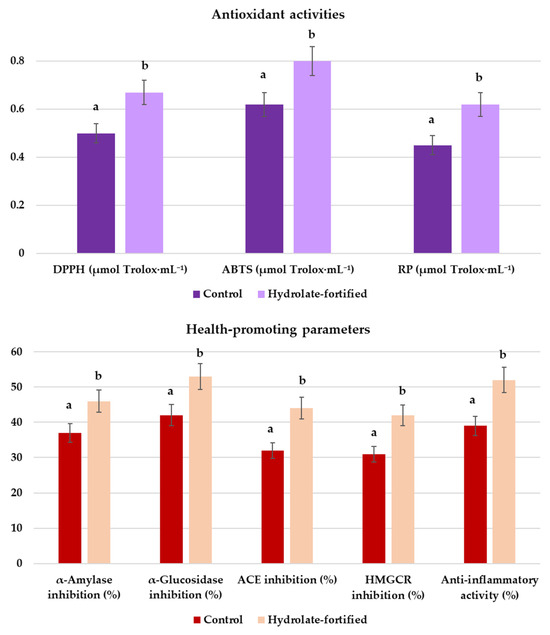

3.3. Antioxidant and Health-Promoting Potentials

The final tibicos beverages displayed promising antioxidant and health-promoting activities, which were further enhanced by fortification with lemon catnip hydrolate (Figure 2). Among the antioxidant assays, DPPH, ABTS, and RP, all showed higher values in the hydrolate-fortified sample compared with the control. DPPH radical scavenging increased from 0.50 to 0.67 μmol Trolox/mL, ABTS from 0.62 to 0.80 μmol Trolox/mL, and RP from 0.45 to 0.62 μmol Trolox/mL. These results indicate a 28–38% improvement in antioxidant performance upon hydrolate addition. The ABTS radical scavenging capacity, in particular, was significantly elevated, suggesting that hydrolate-derived phenolic and terpenoid compounds contributed additional electron-donating capacity. Similar improvements in antioxidant status have been reported when kefir-like beverages were supplemented with plant extracts rich in secondary metabolites, such as Hibiscus sabdariffa or green tea infusions [15,45,46]. The enhancement in antioxidant activity observed in the hydrolate-fortified tibicos is consistent with the chemical composition of N. cataria var. citriodora hydrolate, which is dominated by citral-type monoterpenoids, primarily geranial and neral, as well as geraniol, citronellol, linalool, and related oxygenated terpenes (Table 2). These compounds are well documented for their radical-scavenging properties. Citral acts as an efficient electron donor and can quench DPPH∙ and ABTS∙+ through hydrogen atom transfer and single electron transfer mechanisms [47]. Geraniol and citronellol similarly contribute through allylic hydrogen donation, while linalool is known to stabilize free radicals via resonance delocalization [48]. In the context of tibicos, these volatile compounds dissolve into the aqueous phase during fermentation, where they can interact with and neutralize free radicals present in the DPPH and ABTS assays.

Figure 2.

Bioactive properties of final tibicos beverages. Enzymatic inhibitory activities of control tibicos (dark purple bars) and hydrolate-fortified tibicos (light purple bars) against α-amylase, α-glucosidase, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase (HMGCR), and anti-inflammatory activity. Values are means ± SD (n = 3). Different letters above bars indicate statistically significant differences between groups (p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA).

The enzymatic inhibition assays further demonstrated the functional potential of these beverages. Enzyme-inhibitory activities also increased significantly in the hydrolate-fortified samples. α-Amylase inhibition increased from 37% in the control to 46% with hydrolate. α-Glucosidase inhibition increased from 42% to 53%. ACE inhibition similarly increased from 32% to 44%, indicating an enhanced antihypertensive potential. HMG-CoA reductase inhibition increased from 31% to 42%, showing improved hypolipidemic activity. Both samples exhibited inhibitory effects against α-amylase and α-glucosidase, key enzymes in carbohydrate digestion, with stronger inhibition observed in the fortified tibicos. This suggests a potential role in moderating postprandial glycemic response. Comparable outcomes have been reported for kombucha and plant-enriched kefir, where phenolic-rich components enhanced antidiabetic properties [46]. Inhibition of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) was also greater in the hydrolate-fortified beverage. ACE inhibition is a well-known pathway for blood pressure reduction, and functional beverages containing microbial biopeptides or plant polyphenols have often demonstrated such activity [49]. Similarly, inhibition of HMG-CoA reductase, the rate-limiting enzyme in cholesterol biosynthesis, was modestly higher in the fortified sample, suggesting an antihypercholesterolemic potential. Previous studies on fermented herbal infusions and synbiotic beverages also highlight this as a valuable functional endpoint [50].

Anti-inflammatory activity, as assessed by inhibition of pro-inflammatory pathways, was improved in the fortified tibicos compared to the control. As can be seen in Figure 2, anti-inflammatory activity also benefited from hydrolate incorporation, increasing from 39 ± 2.7% in the control to 52 ± 3.6% in the hydrolate-treated tibicos. This effect may be linked to both microbial metabolites (such as exopolysaccharides and short-chain fatty acids) and hydrolate-derived phytochemicals. In the literature, fortification of fermented drinks with essential oils and aromatic plant extracts has been shown to synergistically enhance anti-inflammatory capacity [51]. These results indicate that tibicos fermentation itself already generates a product with substantial bioactivity, but the incorporation of N. cataria hydrolate amplifies these effects, particularly for antioxidant activity, enzyme inhibition related to glucose and lipid metabolism, and anti-inflammatory potential. This positions hydrolate-fortified tibicos as a candidate synbiotic beverage with multifunctional health benefits, in line with the growing trend of plant–microbe synergistic functional foods. The enhancement of functional properties in the hydrolate-fortified tibicos is closely connected to the fermentation dynamics described earlier.

The enhanced antioxidant, enzyme-inhibitory, and anti-inflammatory potentials observed in the hydrolate-fortified tibicos can be attributed to the combined contributions of microbial fermentation processes and the bioactive constituents of N. cataria var. citriodora hydrolate. Fortification altered the chemical environment of the fermentation matrix, resulting in measurable increases in functional activities. However, additional metabolomic analyses would be required to precisely identify which compounds or metabolic pathways are responsible for these effects. Interestingly, hydrolate fortification was associated with a modest reduction in yeast counts, whereas lactic acid bacteria reached similar final levels in both treatments (Figure 1). This differential response is consistent with the antimicrobial profile of the predominant hydrolate constituents. Lemon catnip hydrolate is rich in citral-type aldehydes (geranial and neral), geraniol, citronellol, and other oxygenated monoterpenes (Table 2), which have been widely reported to exert stronger inhibitory effects on yeasts and filamentous fungi than on lactic acid bacteria [7,52]. These compounds can intercalate into ergosterol-containing membranes, increase membrane fluidity and permeability, and ultimately cause leakage of intracellular components and impairment of energy metabolism in yeast cells, while Gram-positive bacteria such as LAB often display higher tolerance due to differences in cell envelope structure and membrane composition [53]. The detected concentrations of hydrolate-derived terpenoids in this study were not sufficient to suppress yeast growth completely but may have slightly limited their proliferation compared with LAB, resulting in the selective reduction observed. The obtained results do not directly explain the mechanism of action, but the observed pattern fits well with the known higher sensitivity of yeasts to citral and related monoterpenoids and suggests that hydrolate can subtly modulate the microbial balance in the fermenting matrix.

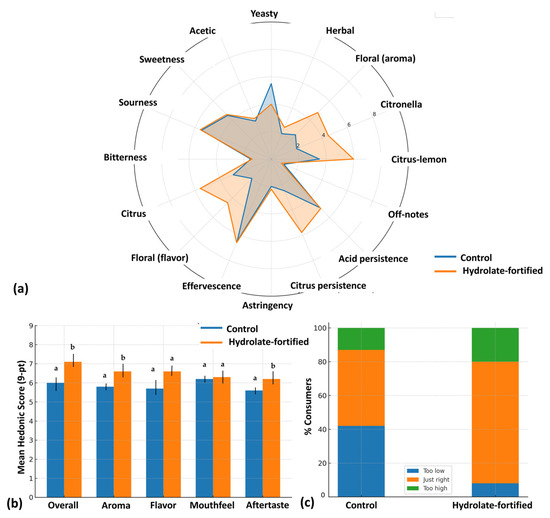

3.4. Volatile Profile and Sensory Attributes

The sensory assessment revealed that hydrolate fortification significantly shaped the aroma and flavor profile of tibicos (Figure 3). Trained panelists consistently described the hydrolate-fortified beverage as more citrus-forward and floral, with clear lemon-like and geranium-like notes. Quantitative descriptive analysis (QDA) confirmed these perceptions: the citrus-lemon aroma intensity in the fortified sample was nearly double that of the control, while floral flavor also scored significantly higher. At the same time, control tibicos carried stronger yeasty and slightly acetic impressions, which aligns with earlier findings that botanical extracts can soften fermentation-derived notes in kefir-like beverages [50,51]. The enhanced sensory profile can be directly linked to the volatile composition of Nepeta cataria var. citriodora. This hydrolate is rich in citronellal, geraniol, and citral, all of which are terpenoids with characteristic citrus and floral aromas [7]. The presence of these compounds not only shifted the QDA profiles but also contributed to the freshness and balance reported by panelists, who consistently associated the fortified sample with greater complexity and refinement.

Figure 3.

Sensory evaluation: (a) QDA analysis for all sensory attributes; (b) Mean hedonic score (bars represent means ± SD); (c) JAR analysis. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences between samples (p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA).

Consumer testing further supported these findings. Overall liking scores were significantly higher for the hydrolate-fortified tibicos (7.1 ± 1.1) compared to the control (6.0 ± 1.0), with a medium-to-large effect size (Cohen’s dz = 0.72). Hedonic evaluations of aroma and flavor showed the same pattern, with increases of nearly one point on the 9-point scale. Mouthfeel did not differ between samples, indicating that carbonation and tactile sensations were unaffected by the fortification process. However, aftertaste ratings were more favorable for the fortified beverage, with participants describing it as “fresher” and “less acidic.” Notably, purchase intent was also higher for the hydrolate-fortified tibicos, with 65% of participants indicating they would “probably” or “definitely buy,” compared to 40% for the control. These results echo recent consumer studies showing that botanical enrichment improves the acceptability and marketability of fermented beverages such as kombucha and kefir [33,54,55,56,57].

Just-about-right (JAR) analysis highlighted citrus intensity as a major driver of liking. In the control beverage, 42% of participants rated citrus as “too low,” a shortfall associated with a hedonic penalty of one full unit. By contrast, 72% of consumers judged citrus intensity in the fortified sample as “just right,” effectively eliminating penalties. Floral intensity produced a smaller but meaningful effect: while most consumers appreciated the floral note in the fortified tibicos, 20% rated it “too high,” with a penalty of approx. 0.8 hedonic units. This indicates that while hydrolate addition is beneficial, fine-tuning its concentration may optimize consumer acceptance further. Other sensory attributes, including sweetness, sourness, effervescence, and yeasty character, remained within acceptable ranges, with hedonic penalties well below the 0.75 threshold.

Altogether, the sensory results demonstrate that hydrolate addition enriched tibicos with distinctive citrus and floral attributes, enhancing both trained panel evaluation and consumer acceptance. These improvements reflect broader consumer trends favoring natural, plant-derived fortification strategies, which not only elevate sensory quality but also contribute bioactive terpenoids that may support functional claims. From a technological perspective, incorporating N. cataria var. citriodora hydrolate during fermentation represents a viable strategy to refine aroma and flavor complexity, echoing earlier reports where botanical supplementation enhanced the sensory and functional qualities of kombucha and kefir [37,56].

3.5. Multivariate Linkage Between Sensory and Volatiles

Additionally, the correlation heatmap (Figure 4) provides a detailed overview of how individual volatile compounds contributed to specific sensory attributes in the hydrolate-fortified beverage. A clear association was observed between citrus- and floral-type monoterpenes and corresponding sensory descriptors. Compounds such as nerol + citronellol, neral, geranial, linalool, and geraniol showed strong positive correlations with citrus–lemon, citronella, citrus flavor, citrus persistence, and both floral (aroma) and floral (flavor) attributes. These results confirm that the hydrolate’s characteristic monoterpene profile directly enhanced the citrus–floral aromatic quality reported by the QDA panel.

Figure 4.

Correlation heatmap linking GC–MS volatile compounds with sensory attributes of control and hydrolate-fortified tibicos.

Herbal sensory notes were primarily associated with nerol oxide and 6-methyl-5-hepten-2-one, reflecting their known green and herbal odor properties. In contrast, attributes such as yeasty, acetic, and acid persistence showed weak or negative correlations with most detected plant-derived volatiles, indicating that these characteristics were driven mainly by fermentation-related metabolites rather than hydrolate constituents. Off-notes and astringency displayed moderate positive correlations with borneol, camphor, and terpinen-4-ol, compounds known for camphoraceous or musty nuances. The used multivariate correlation analysis demonstrates a chemical–sensory linkage and shows that the enhanced aromatic profile of hydrolate-fortified tibicos is directly attributable to its monoterpene composition. This supports the sensory findings and provides mechanistic evidence for the flavor-modifying potential of Nepeta cataria var. citriodora hydrolate in fermented beverages.

The fermentation kinetics outlined earlier provide an essential framework for understanding both the functional and sensory outcomes of tibicos. The rapid decline in pH and efficient sugar utilization created a biochemical environment that supported robust lactic acid bacterial growth while stabilizing yeast and acetic acid bacteria populations. These microbial and metabolic dynamics directly shaped the antioxidant and enzymatic inhibition activities observed in the final beverages, as lactic acid bacteria are known to release bioactive peptides, while yeasts and acetic acid bacteria contribute phenolic biotransformation. The enhanced health-promoting activities in the hydrolate-fortified sample therefore reflect not only the intrinsic bioactivity of N. cataria compounds but also their interaction with the evolving microbial consortium during fermentation. These same biochemical and microbial processes also underpin the sensory attributes of the beverages. The moderation of yeast and acetic acid bacterial growth in the hydrolate-fortified tibicos likely contributed to the reduced perception of yeasty and acetic notes, while the terpenoid-rich hydrolate introduced fresh citrus and floral aromas that resonated with both trained panelists and consumers. In this way, the interplay between fermentation kinetics and bioactivity translates into tangible sensory benefits, with hydrolate fortification not only elevating health-related properties but also enhancing overall liking and purchase intent. Together, these results demonstrate how targeted botanical enrichment can harmonize microbial dynamics, functional activity, and sensory quality, positioning fortified tibicos as a multifunctional synbiotic beverage [57,58].

These findings demonstrate how the microbial and biochemical dynamics of tibicos fermentation directly translate into both functional bioactivity and sensory quality. The rapid acidification and robust lactic acid bacterial growth provided a stable fermentation base, while hydrolate fortification introduced subtle shifts that enhanced antioxidant potential and enzymatic inhibition activities. These biochemical improvements were paralleled by sensory benefits, with consumers perceiving the fortified tibicos as fresher, more citrus-forward, and overall more appealing. By linking fermentation kinetics, functional activities, and sensory outcomes, this study highlights the synergistic value of incorporating lemon catnip hydrolate, not only to strengthen the health-promoting properties of tibicos but also to align its sensory profile with consumer preferences. The chemical and microbiological shifts observed in hydrolate-fortified tibicos collectively shaped the sensory characteristics of the final beverage. The enhanced antioxidant capacity reflects the increased abundance of reactive monoterpenoids capable of donating hydrogen atoms or electrons to neutralize radicals. These same compounds reinforced the citrus–floral aroma profile, as confirmed by sensory analysis. At the microbiological level, the slight reduction in yeast proliferation likely moderated ethanol production, thereby limiting subsequent oxidation to acetic acid by acetic acid bacteria. This attenuation aligns with the marginally higher final pH and the sensory panel’s perception of a more balanced acidity. Meanwhile, LAB maintained normal growth and continued to produce lactic acid, contributing to the mild sourness typical of tibicos. Together, these interconnected chemical and microbial modulations translated into improved sensory outcomes, characterized by intensified citrus–floral notes, smoother acidity, and higher acceptability among consumers. Future studies should apply targeted and untargeted metabolomic approaches to identify and quantify the transformation of hydrolate-derived terpenoids during fermentation, determine their stability in the tibicos matrix, and evaluate how these metabolites contribute to antioxidant capacity, enzyme-inhibitory activities, and citrus–floral sensory expression.

However, the present study did not include targeted chemical characterization of fermentation-derived metabolites or in vivo validation of bioactivity, which should be addressed in future research. Future work should also systematically vary both inoculum size and hydrolate concentration to identify the minimal hydrolate dose that achieves the desired functional and sensory effects while maintaining optimal fermentation performance. Additional metabolomic and microbiome analyses would further clarify how hydrolate constituents interact with microbial communities and influence functional outcomes.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that fortification of tibicos with Nepeta cataria var. citriodora hydrolate represents an effective strategy for enhancing the functional and sensory attributes of a traditional fermented beverage. Hydrolate addition produced consistent improvements in antioxidant activity, enzyme-inhibitory potential, and anti-inflammatory responses while simultaneously modulating fermentation kinetics and promoting a more desirable citrus–floral aroma profile. The integrated multivariate approach further confirmed a clear linkage between hydrolate-derived volatile terpenoids and specific sensory attributes, providing a mechanistic basis for the observed improvements in product quality. Importantly, these findings highlight the feasibility of incorporating botanical hydrolates as natural functional enhancers in fermentation-based beverages, contributing to the broader development of plant-enriched synbiotic products. This work provides foundational evidence supporting the use of lemon catnip hydrolate as a multifunctional ingredient capable of enhancing both the sensory appeal and health-relevant properties of tibicos, offering promising opportunities for innovation within the functional beverage sector.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/fermentation11120683/s1, Figure S1: GS-MS analysis of Nepeta cataria var. citriodora hydrolate sample.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.T. and O.Š.; methodology, D.C., A.R. and J.Č.-B.; software, O.Š.; validation, L.T., A.V. and S.L.; formal analysis, L.T., A.V. and S.L.; investigation, A.T.; resources, M.A. and S.F.; data curation, A.T., O.Š. and A.R.; writing—original draft preparation, A.T., L.T., A.V. and S.L.; writing—review and editing, O.Š., D.C. and A.R.; visualization, A.T.; supervision, D.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia under the following grant numbers: 451-03-136/2025-03/200134, 451-03-137/2025-03/200134 and 451-03-136/2025-03/200032.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Technology Novi Sad, University of Novi Sad, Serbia (Ref. No. 020-8/34, approval date 30 September 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article and Supplementary Materials; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abdul Manan, M. Progress in Probiotic Science: Prospects of Functional Probiotic-Based Foods and Beverages. Int. J. Food Sci. 2025, 1, 5567567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkir, E.; Yilmaz, B.; Sharma, H.; Esatbeyoglu, T.; Ozogul, F. Challenges in water kefir production and limitations in human consumption: A comprehensive review of current knowledge. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida, K.V.; Sant’ Ana, C.T.; Wichello, S.P.; Louzada, G.E.; Verruck, S.; Teixeira, L.J.Q. Water Kefir: Review of Microbial Diversity, Potential Health Benefits, and Fermentation Process. Processes 2025, 13, 885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, A.F.; Moure, M.C.; Quiñoy, F.; Esposito, F.; Simonelli, N.; Medrano, M.; León-Peláez, Á. Water kefir, a fermented beverage containing probiotic microorganisms: From ancient and artisanal manufacture to industrialized and regulated commercialization. Future Foods 2022, 5, 100123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahl, H.S.A.; Naguib, N.Y.; Hussein, M.S. Evaluation growth and essential oil content of catmint and lemon catnip plants as new cultivated medicinal plants in Egypt. Ann. Agric. Sci. 2018, 63, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, A.; Shahzad, H.; Ahmed, B.; Muntean, T.; Waseem, M.; Tabassum, A. Phytochemical profiling of antimicrobial and potential antioxidant plant: Nepeta cataria. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 3, 969316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aćimović, M.; Lončar, B.; Rat, M.; Cvetković, M.; Stanković Jeremić, J.; Pezo, M.; Pezo, L. Seasonal Variation in Volatile Profiles of Lemon Catnip (Nepeta cataria var. citriodora) Essential Oil and Hydrolate. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimek, B.; Modnicki, D. Terpenoids and sterols from Nepeta cataria L. var. citriodora (Lamiaceae). Acta Pol. Pharm. 2005, 62, 231–235. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, H.H.; Fernandes, I.P.; Amaral, J.S.; Rodrigues, A.E.; Barreiro, M.F. Unlocking the potential of hydrosols: Transforming essential oil byproducts into valuable resources. Molecules 2024, 29, 4660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aćimović, M.; Tešević, V.; Smiljanić, K.T.; Cvetković, M.; Stanković, J.; Kiprovski, B.; Sikora, V. Hydrolates: By-products of essential oil distillation: Chemical composition, biological activity and potential uses. Adv. Technol. 2020, 9, 54–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, E.N.; Reichert, W.; Vasilatis, A.A.; Allen, K.A.; Wu, Q.; Simon, J.E. Essential oil yield and aromatic profile of lemon catnip and lemon-scented catnip selections at different harvesting times. J. Med. Act. Plants 2020, 9, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aćimović, M.; Lončar, B.; Cvetković, M.; Stanković Jeremić, J.; Vujisić, L.J.; Puvača, N.; Pezo, L. Correlation between weather conditions and volatile organic compound profiles in Artemisia absinthium L. essential oil and recovery oil from hydrolate. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2025, 122, 105029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šovljanski, O.; Saveljić, A.; Aćimović, M.; Šeregelj, V.; Pezo, L.; Tomić, A.; Ćetković, G.; Tešević, V. Biological Profiling of Essential Oils and Hydrolates of Ocimum basilicum var. Genovese and var. Minimum Originated from Serbia. Processes 2022, 10, 1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laureys, D.; De Vuyst, L. Microbial species diversity, community dynamics, and metabolite kinetics of water kefir fermentation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 2564–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello, F.; Restuccia, D.; Spizzirri, U.G.; Carullo, G.; Leporini, M.; Loizzo, M.R. Improving Kefir Bioactive Properties by Functional Enrichment with Plant and Agro-Food Waste Extracts. Fermentation 2020, 6, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, F.; Dai, X.; Liu, Y.; Mu, J.; Wang, J.; Ma, Q.; Sun, J. Changes in vinegar quality and microbial dynamics during fermentation using a self-designed drum-type bioreactor. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1126562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cufaoglu, G.; Erdinc, A.N. Comparative analyses of milk and water kefir: Fermentation temperature, physicochemical properties, sensory qualities, and metagenomic composition. Food Biosci. 2023, 55, 103079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erginkaya, Z.; Turhan, E.Ü. Enumeration and identification of dominant microflora during the fermentation of Shalgam. Akad. Gıda 2016, 14, 92–97. [Google Scholar]

- Ranitović, A.; Šovljanski, O.; Aćimović, M.; Pezo, L.; Tomić, A.; Travičić, V.; Markov, S. Biological potential of alternative kombucha beverages fermented on essential oil distillation by-products. Fermentation 2022, 8, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Shin, Y. Antioxidant compounds and activities of edible roses (Rosa hybrida spp.) from different cultivars grown in Korea. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2017, 60, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanisamy, U.D.; Ling, L.T.; Manaharan, T.; Appleton, D. Rapid isolation of geraniin from Nephelium lappaceum rind waste andits anti-hyperglycemic activity. Food Chem. 2011, 127, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachmawati, H.; Soraya, I.S.; Kurniati, N.F.; Rahma, A. In vitro study on antihypertensive and antihypercholesterolemic effects ofa curcumin nanoemulsion. Sci. Pharm. 2016, 84, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Kim, H.J.; Chae, H.; Yoon, N.E.; Jung, B.H. Aster glehni F. Schmidt Extract Modulates the Activities of HMG-CoA Reductase and Fatty Acid Synthase. Plants 2021, 10, 2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, H.A.; Zaman, S.; Juhara, F.; Akter, L.; Tareq, S.M.; Masum, E.H.; Bhattacharjee, R. Evaluation of antinociceptive, in-vivo & in-vitro anti-inflammatory activity of ethanolic extract of Curcuma zedoaria rhizome. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 14, 346. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, H.; Bleibaum, R.N.; Thomas, H.A. Sensory Evaluation Practices, 4th ed.; Elsevier Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 8586:2023; Sensory Analysis—Selection and Training of Sensory Assesors. International Standard Organization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- ISO 4121:2003; Sensory Analysis—Guidelines for the Use of Quantitative Response Scales. International Standard Organization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2003.

- Stone, H.; Sidel, J.; Oliver, S.; Woolsey, A.; Singleton, R.C. Sensory evaluation by quantitative descriptive analysis. In Descriptive Sensory Analysis in Practice; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004; pp. 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawless, H.T.; Heymann, H. Sensory Evaluation of Food: Principles and Practices; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Şafak, H.; Gün, İ.; Tudor Kalit, M.; Kalit, S. Physico-Chemical, Microbiological and Sensory Properties of Water Kefir Drinks Produced from Demineralized Whey and Dimrit and Shiraz Grape Varieties. Foods 2023, 12, 1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šovljanski, O.; Saveljić, A.; Tomić, A.; Šeregelj, V.; Lončar, B.; Cvetković, D.; Ranitović, A.; Pezo, L.; Ćetković, G.; Markov, S.; et al. Carotenoid-Producing Yeasts: Selection of the Best-Performing Strain and the Total Carotenoid Extraction Procedure. Processes 2022, 10, 1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, P.; Chinnasamy, B.; Jin, L.; Clark, S. Use of just-about-right scales and penalty analysis to determine appropriate concentrations of stevia sweeteners for vanilla yogurt. J. Dairy Sci. 2014, 97, 3262–3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formisano, C.; Rigano, D.; Senatore, F. Chemical constituents and biological activities of Nepeta species. Chem. Biodivers. 2011, 8, 1783–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Torre, C.; Pino, R.; Fazio, A.; Plastina, P.; Loizzo, M.R. Synergistic bioactive potential of combined fermented Kombucha and water kefir. Beverages 2025, 11, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajdek-Bieda, A.; Pawlińska, J.; Wróblewska, A.; Łuś, A. Evaluation of the antimicrobial activity of Geraniol and selected Geraniol Transformation products against Gram-positive Bacteria. Molecules 2024, 29, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbaspour, N. Fermentation’s pivotal role in shaping the future of plant-based foods: An integrative review of fermentation processes and their impact on sensory and health benefits. Appl. Food Res. 2024, 4, 100468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onsun, B.; Toprak, K.; Sanlier, N. Kombucha Tea: A Functional Beverage and All its Aspects. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2025, 14, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diez-Ozaeta, I.; Astiazaran, O.J. Recent advances in Kombucha tea: Microbial consortium, chemical parameters, health implications and biocellulose production. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2022, 377, 109783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendonca, G.R.; Pinto, R.A.; Praxedes, É.A.; Abreu, V.K.G.; Dutra, R.P.; Pereira, A.F.; de Oliveira Lemos, T.; dos Reis, A.S.; Pereira, A.L.F. Kombucha based on unconventional parts of the Hibiscus sabdariffa L.: Microbiological, physico-chemical, antioxidant activity, cytotoxicity and sensorial characteristics. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2023, 34, 100804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travičić, V.; Šovljanski, O.; Tomić, A.; Perović, M.; Milošević, M.; Ćetković, N.; Antov, M. Augmenting Functional and Sensorial Quality Attributes of Kefir Through Fortification with Encapsulated Blackberry Juice. Foods 2023, 12, 4163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, R.O.; de Oliveira, R.L.; de Moraes, M.M.; Santos, W.W.V.; Gomes da Câmara, C.A.; da Silva, S.P.; Porto, C.S.; Porto, T.S. Evaluation of the Impact of Fermentation Conditions, Scale Up and Stirring on Physicochemical Parameters, Antioxidant Capacity and Volatile Compounds of Green Tea Kombucha. Fermentation 2025, 11, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Shu, G.; Dai, C.; Kang, J.; Liu, Y.; Shan, C. Comparison of fermentation performance and metabolites of water kefir grains. Acta Sci. Pol. Technol. Aliment. 2024, 23, 379–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zannini, E.; Lynch, K.M.; Nyhan, L.; Sahin, A.W.; O’ Riordan, P.; Luk, D.; Arendt, E.K. Influence of Substrate on the Fermentation Characteristics and Culture-Dependent Microbial Composition of Water Kefir. Fermentation 2023, 9, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Montijo-Prieto, S.; Razola-Díaz, M.d.C.; Barbieri, F.; Tabanelli, G.; Gardini, F.; Jiménez-Valera, M.; Ruiz-Bravo, A.; Verardo, V.; Gómez-Caravaca, A.M. Impact of Lactic Acid Bacteria Fermentation on Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Activity of Avocado Leaf Extracts. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, R.J.; de Fatima Borges, M.; de Freitas Rosa, M.; Castro-Gómez, R.J.H.; Spinosa, W.A. Acetic acid bacteria in the food industry: Systematics, characteristics and applications. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2018, 56, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusufoğlu, B.; Açar, Y.; Kezer, G.; Zargarchi, S.; Mertoglu, K.; Esatbeyoglu, T. Exploring the potential of anthocyanin-infused fermented beverages for sustainable health solutions: A pathway to functional food development. Future Foods 2025, 12, 100708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhag, R.; Angeli, L.; Scampicchio, M.; Ferrentino, G. From Quantity to Reactivity: Advancing Kinetic-Based Antioxidant Testing Methods for Natural Compounds and Food Applications. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2025, 24, e70229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandur, E.; Major, B.; Rák, T.; Sipos, K.; Csutak, A.; Horváth, G. Linalool and Geraniol Defend Neurons from Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Iron Accumulation in In Vitro Parkinson’s Models. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadopoulou, D.; Chrysikopoulou, V.; Rampaouni, A.; Tsoupras, A. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of water kefir microbiota and its bioactive metabolites for health promoting bio-functional products and applications. AIMS Microbiol. 2024, 10, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xingfei, L.; Shunshun, P.; Wenji, Z.; Lingli, S.; Qiuhua, L.; Ruohong, C.; Shili, S. Properties of ACE inhibitory peptide prepared from protein in green tea residue and evaluation of its anti-hypertensive activity. Process Biochem. 2020, 92, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskaran, G.; Salvamani, S.; Ahmad, S.A.; Shaharuddin, N.A.; Pattiram, P.D.; Shukor, M.Y. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitory activity and phytocomponent investigation of Basella alba leaf extract as a treatment for hypercholesterolemia. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2015, 9, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Máthé, Á. Introduction to medicinal and aromatic plants in North America. In Medicinal and Aromatic Plants of North America; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Šovljanski, O.; Kljakić, A.C.; Tomić, A. Antibacterial and antifungal potential of plant secondary metabolites. In Plant Specialized Metabolites: Phytochemistry, Ecology and Biotechnology; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 163–204. [Google Scholar]

- Maleš, I.; Pedisić, S.; Zorić, Z.; Elez-Garofulić, I.; Repajić, M.; You, L.; Vladimir-Knežević, S.; Butorac, D.; Dragović-Uzelac, V. The medicinal and aromatic plants as ingredients in functional beverage production. J. Funct. Foods 2022, 96, 105210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazán, D.L.; del Río, P.G.; Domínguez, J.M.; Cortés-Diéguez, S.; Mejuto, J.C.; Pérez-Guerra, N. The Chemical, Microbiological and Volatile Composition of Kefir-like Beverages Produced from Red Table Grape Juice in Repeated 24-h Fed-Batch Subcultures. Foods 2022, 11, 3117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, A.M.D.O.; Miguel, M.A.L.; Peixoto, R.S.; Rosado, A.S.; Silva, J.T.; Paschoalin, V.M.F. Microbiological, technological and therapeutic properties of kefir: A natural probiotic beverage. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2013, 44, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, A.Q.; Lau, S.W.; Chin, N.L.; Talib, R.A.; Basha, R.K. Fermented beverage benefits: A comprehensive review and comparison of kombucha and kefir microbiome. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhiman, S.; Kaur, S.; Thakur, B.; Singh, P.; Tripathi, M. Nutritional Enhancement of Plant-Based Fermented Foods: Microbial Innovations for a Sustainable Future. Fermentation 2025, 11, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).