Abstract

Oak (Quercus spp.), traditionally used for aging alcoholic bever ages, is not native in many countries, which increases production costs and environmental impact. During the aging process of alcoholic beverages, complex physical and chemical transformations occur that determine their chemical composition and sensory quality, many of which are unique depending on the type of wood used in the process. In this context, Maclura tinctoria (Tajuva), a native Brazilian species rich in phenolic compounds, was evaluated based on its phenolic composition and extraction behavior as a sustainable alternative for beverage aging. Wood chips were subjected to three toasting levels (untoasted, medium, and high) and aged for up to 360 days in two hydroethanolic model systems (10% and 14% v/v ethanol). The total and individual phenolic compounds were determined using the Folin–Ciocalteu method and HPLC–DAD/LC–MS/MS analysis. Results showed that toasting level, ethanol concentration, and aging time significantly influenced phenolic extraction. Untoasted Tajuva released the highest amounts of phenolic acids and flavonoids, particularly gallic and caffeic acids, and quercetin, respectively; while medium toasting favored the formation of thermally derived aromatic compounds, such as vanillic acid. The 14% ethanol system enhanced extraction efficiency for most analytes. Overall, Tajuva wood exhibited higher phenolic yields than French oak under comparable conditions, highlighting its chemical richness and extraction reactivity. These findings support the use of M. tinctoria as an eco-efficient and functional alternative to oak for the maturation of alcoholic beverages.

1. Introduction

The aging process of alcoholic beverages in contact with wood promotes complex physical, chemical, and sensory transformations that significantly affect their composition and quality [1,2]. During maturation, the interaction between ethanol, water, and the lignocellulosic matrix of the wood leads to the extraction of a wide variety of compounds, including tannins, phenolic acids, aldehydes, lactones, and volatile phenols [3,4,5]. These compounds contribute to the development of color, aroma, flavor, and antioxidant capacity, which are key attributes of aged beverages [6,7].

Oak (Quercus sp.) barrels remain the most traditional and widely used material for aging wines and spirits [1,2]. However, in Brazil, oak is not native and must be imported from Europe or North America, increasing production costs and environmental impacts. The search for sustainable and cost-effective alternatives has therefore led to interest in the use of native Brazilian woods, which are abundant and may impart distinctive chemical profiles and sensory characteristics to beverages [8,9]. Previous research has demonstrated that several native Brazilian wood species can be successfully used for the maturation of sugarcane spirits, such as peanut (Plerogyne nitens), amburana (Amburana cearensis), cedar (Cedrela fissilis), jatobá (Hymenaea courbaril), ipê (Tabebuia sp.), freijó (Cordia goeldiana), garapa (Apuleia leiocarpa), balm (Myroxylon peruiferum), yellow mahogany (Plathymenia foliosa), and jequitibá (Cariniana legalis), all of which promoted an increase in total phenolic content and contributed to color and flavor enhancement [10,11].

In addition to wood selection, the technological parameters of aging—such as wood size, toasting level, and contact surface area—play a fundamental role in the kinetics of compound extraction [12]. Traditional barrel maturation is slow and capital-intensive, often requiring several months or years to achieve the desired sensory complexity. To optimize this process, alternative methods such as the use of wood fragments (chips, cubes, granules, or staves) have been developed [13]. These materials increase the wood–liquid interface, accelerate the release of volatile and phenolic compounds, and allow for better control of extraction intensity [14,15]. The use of toasting further modifies the composition of extractable compounds by thermally degrading lignin, hemicellulose, and cellulose, leading to the formation of desirable aroma compounds such as vanillin, furfural, and guaiacol derivatives [1].

In this scenario, Maclura tinctoria (Tajuva), a South America native species of the Moraceae family, presents significant potential for use in beverage aging. This wood is known for its high density, attractive color, and richness in phenolic compounds such as epicatechin, catechin, quercetin, gallic acid, and syringaldehyde [16,17]. These compounds are associated with antioxidants and antimicrobial activities [18], which could positively influence both the preservation and sensory properties of aged beverages.

From a production and industrial perspective, M. tinctoria is a hardwood traditionally used in structural applications, furniture, and outdoor uses due to its mechanical resistance and durability [19]. Although detailed cost analyses specifically addressing its use in beverage aging are scarce, forestry-based economic surveys of Brazilian native species report indicative market values for M. tinctoria wood in the range of approximately USD 20–74 per cubic meter, depending on region, timber quality, and harvesting conditions [20]. These values suggest a substantially lower cost compared to imported oak commonly used in cooperage. However, despite its mechanical robustness, there are currently no reports in the scientific or cooperage literature documenting the use of M. tinctoria for the manufacture of traditional barrels or barriques, which require specific anatomical and physical characteristics—such as straight grain, controlled porosity, and dimensional stability—that are well established for Quercus spp. [21]. Consequently, the potential application of M. tinctoria in alcoholic beverage aging is more realistically associated with alternative technologies, such as wood chips, staves, or blocks used in inert containers, which allow controlled extraction of phenolic compounds while bypassing the strict requirements of barrel production. Considering its abundance in Brazil, its promising phenolic composition, and its economic accessibility, M. tinctoria may serve as a sustainable and functional alternative to oak within these technological frameworks.

Therefore, the present study aims to evaluate the transfer of polyphenolic compounds from Tajuva chips subjected to three toasting levels in two alcoholic model systems during different aging times in order to determine the extraction kinetics, optimal aging periods for total polyphenol release, and the resulting phytochemical profile.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Standards

Analytical standards of gallic acid (97.5%); catechin (98%); chlorogenic acid (95%); vanillic acid (97%); caffeic acid (98%); syringic acid (95%); p-coumaric acid (98%); trans-ferulic acid (99%); and kaempferol-3DGlp (97%) were obtained from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). HPLC-grade methanol was supplied by Merck (Darmstadt, Germany), while HPLC-grade acetonitrile and formic acid were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Ultrapure water was produced using a Milli-Q purification system (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). A polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) syringe filter and nylon membrane were supplied by Allcrom (São Paulo, SP, Brazil).

2.2. Wood Samples and Toasting Procedure

French oak (Quercus spp.) wood chips were supplied by WE Consultoria (Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil). The heartwood of Tajuva (Maclura tinctoria (L)) was obtained from the norwest region of Rio Grande do Sul (RS), Brazil (Porto Mauá), and reduced to chips with an approximate average thickness of 2 mm. Both wood chips were submitted to three treatments, without toast, medium toast (1.3 h at 175 °C), and high toast (1.5 h at 195 °C), in an electric conventional oven. The toasting protocol was adapted from a previously reported methodology [6].

2.3. Hydroethanolic Model System and Aging Conditions

Two hydroethanolic beverage models were tested to represent typical alcohol contents of wines, with ethanolic concentration of 10% (v/v; white wine) and 14% (v/v; red wine). Prior to wood contact, the model solutions were adjusted to pH 3.5 using tartaric acid, in order to mimic the acidic conditions commonly found in wine matrices. After thermal treatment, toasted and untoasted wood chips were placed in amber flasks with 100 mL of each beverage model. The solid-to-liquid ratio of wood chips to the hydroethanolic solution was 2:1000 g/mL. For each treatment and aging time, three independent flasks (n = 3) were prepared and stored in the dark at 20 °C for up to 12 months to simulate maturation. During this simulated aging period, samples (extracts) were collected at 1, 30, 60, 90, 120, 150, 180, and 360 days of aging and subsequently analyzed.

2.4. Total Phenolic Content and Extractions Kinetics

The extraction kinetics of total phenolic compounds were monitored throughout the aging period. Total phenolic content was determined using the Folin–Ciocalteu colorimetric assay [22]. Quantification was performed using gallic acid calibration curve (0–80 mg/L; Y = y = 0.0078x + 0.026; R2 = 0.999), and the results are expressed as milligrams of gallic acid equivalent per liter (mg GAE/L).

2.5. Phenolic Compound Identification via LC-IT-MS/MS

Prior to chromatographic analysis, samples were purified via solid-phase extraction (SPE) following the procedure described by [23], with minor adaptations. Briefly, C-18 SPE cartridges (Strata C18-E, Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA) were activated with methanol and conditioned with acidified water (0.1% v/v formic acid). After sample loading, polar interferents were removed with three volumes of aqueous formic acid solution (0.1% v/v; 3 × 3 mL), and phenolic compounds were eluted with ethyl acetate (2 × 3 mL). The eluates were evaporated under reduced pressure and reconstituted to 1 mL using acidified methanol and acidified water (0.1% v/v formic acid; 200 + 800 µL). The purified fractions were analyzed using an HPLC system coupled to an ion-trap mass spectrometer (Esquire 6000, Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA, USA) equipped with an electrospray ionization (ESI) source operating in negative ion mode. Instrumental parameters were set according to [24]. Chromatographic separation was achieved on a reversed-phase column (C-18 Kinetix Core-Shell, 150 mm × 4.6 mm, particle size 5 μm; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA) at 38 °C, using a gradient elution of ultrapure water (Milli-Q Gradient System, Millipore Corporation, Burlington, MA, USA) with methanol acidified with formic acid (95:5:0.1 v/v, mobile phase A) and acetonitrile and formic acid (99.9:0.1 v/v; mobile phase B) at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. The standardized best gradient elution conditions were set as follows: 100% A and 0% B from 0 to 4 min; 98% A and 2% B from 4.1 to 9 min; 80% A and 20% B from 9.1 to 24 min; 0% A and 100% B from 24.01 to 46 min; 100% A and 0% B from 46.01 to 53.01. The MS2 experiments were performed in a full scan range of 100 to 1800 m/z of all fragments, formed from three major parent ions. Phenolic compounds were identified based on the retention time, elution order in the reversed-phase column, UV–vis spectra, and MS fragmentation patterns, using authentic standards, literature data, and public databases (PubChem, KEGG, MoNA, ChemSpider, Phenol-Explorer, and FooDB).

2.6. Quantification of Phenolic Compound via HPLC-DAD

Tajuva phenolic compounds were determined via HPLC (LC-20A Prominence, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan), using a quaternary pump (LC-20AD), manual injector, oven column (CTA-20A), and diode array detector (SPDM-20A). The samples and standard solutions were injected in a volume of 20 µL, using the same analytical conditions used in the identification of phenolic compounds (see Section 2.5). Absorption spectrum was recorded from 200 to 800 nm and chromatograms for quantification purposes were obtained at 280 nm for hydroxybenzoates and tannins, at 320 nm for hydroxycinnamates, and at 360 nm for flavonoids and ellagic acid. LC solutions Software (Version 3, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) was used for data processing.

Quantification conditions were validated as pre-established in the Guidelines of the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) [25] (see Supplementary Material, Table S1). Validation was performed to determine the reliability of the analytical method by linearity, limits of detection and quantification, and accuracy, only with those standard compounds that were also detected in samples. Limits of detection (LOD) and quantification (LOQ) were determined as preconized by [25]. Calibration curves were constructed using stock solutions of nine phenolic compounds (gallic acid; catechin; caffeic acid; chlorogenic acid; vanillic acid; p-coumaric acid; trans-ferulic acid; syringic acid; and kaempferol 3-dGp) in methanol. These solutions were diluted in the initial mobile phase in nine equidistant points within the concentration range of 0.1 to 80 mg/L. Linear regression residual standard deviation (σ) and the slope (m) of calibration curves were used to calculate limits of detection (LOD) and quantification (LOQ). Method precision was evaluated by using repeatability (intra-day) and intermediate precision (inter-day) studies. Compounds that are derivatives of one of the standard monomers were quantified by equivalence and results are expressed as mg/L.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

For each treatment and aging time, three independent flasks (n = 3) were analyzed in these experiments with a completely randomized design. All results were submitted to a three-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Post hoc means comparisons in physicochemical and chromatographic analysis were performed using Tukey’s test at 5% of error probability, using the software Statistica® (Version 9.0, Statsoft, Tulsa, OK, USA).

3. Results and Discussion

In the first stage of this study, the kinetics of phenolic compound release from Tajuva wood during aging were evaluated, and these findings were compared with those of French oak (standard wood for aging). The results obtained showed that the release of phenolic compounds was significantly influenced by factors such as wood type, toasting degree, aging time, and hydroethanolic model systems (10% or 14% ethanol). According to Table 1, in both types of wood, increasing the toasting intensity resulted in a decrease in the release of phenolic compounds (untoasted > medium toast > high toast). The significant differences between toasting levels (indicated by different lowercase letters) suggest that excessive heating during toasting causes thermal degradation of phenolic compounds and the formation of carbonized surface layers, which act as barriers to compound diffusion into the liquid medium. Thus, more intense toasting reduces the availability of soluble phenolic compounds, which has also been observed with Robinia (Robinia pseudoacacia L.) [26]. Changes induced by high wood toasting resulted in the degradation of phenolic compounds, possibly due to aldehydes undergoing degradation reactions [10].

Table 1.

Content of phenolic compounds released over time (up to 360 days) from Tajuva and French oak wood chips in a model system with an alcohol content of 10% (v/v) and 14% (v/v) at three toasting levels.

As expected, aging time also significantly influenced the release of phenolic compounds, particularly in Tajuva wood. A pronounced release peak was observed around 30 days of aging, followed by fluctuations throughout the 360-day period. Although this behavior may initially appear atypical when compared to traditional barrel maturation, it is consistent with accelerated extraction systems employing wood chips. The high surface area-to-volume ratio of wood fragments promotes a rapid diffusion of readily soluble, low-molecular-weight phenolic compounds during the early stages of contact with hydroethanolic media, resulting in an initial extraction maximum [3,12,27]. Importantly, this extraction pattern was consistently observed for both Maclura tinctoria and French oak, regardless of toasting level or ethanol concentration, indicating that it reflects a general kinetic feature of chip-based aging systems rather than a wood-specific or analytical artifact.

Following this initial peak, fluctuations in phenolic content were observed over time, and in some cases, a secondary increase occurred at longer aging periods (180–360 days), which may be associated with the gradual release of compounds more strongly bound to the wood matrix or resulting from chemical transformations occurring over time, such as oxidation, depolymerization, or rearrangement reactions [3,6,14]. Similar fast-release phases followed by stabilization, redistribution, or fluctuation of phenolic content over time have been reported for oak and alternative woods aged in model wine systems using chips or staves [3,12,27]. For French oak, however, the effect of aging time was less pronounced, with smaller variations between periods, suggesting a more stable and predictable release. This behavior is consistent with the traditional use of oak in beverage aging, as its dense and well-characterized anatomical structure tends to promote a slower and more balanced extraction of phenolic compounds over time [27].

The formation of different flavors occurs during different methods of beverage aging, because of compounds produced by the practice of “toasting” or burning barrel wood or wood pieces used in aging, like furans, vanillin (a lignin degradation product), or lactones [28]. Thermal degradation level influences the physical and chemical properties of woods, increasing their porosity in the surface contact and compounds’ extractability [29]. The lignin structure is formed by two principal monomers, guiacyl (1-hidroxi-3-metoxifenilo) and syringil (3,5-dimetoxi-4-hidroxifenilo). In the aging of beverages, guaiacyl generates compounds such as vanillic acid, while syringil results in syringic acid. A possible explanation for the extraction of polyphenols during aging from lignin in the wood into the alcoholic beverage is the hydroethanolic extraction of released monomers. Thus, for French oak and Tajuva, aging times of 180 and 360 days had better extraction than shorter times with similar results in both hydroethanolic model systems.

Tajuva wood exhibited significantly higher values of phenolic compounds compared to French oak, regardless of ethanol concentration (10% or 14%), aging time, or toasting level. This trend, confirmed by the asterisks in Table 1, indicates that Tajuva wood is more reactive and has a greater ability to release soluble compounds, which may be related to its chemical composition—possibly a higher content of lignin and condensed tannins, or a more porous structure that favors diffusion [30]. This corroborates other studies that have shown a high level of phenolics like flavonoids in this wood [16,31].

Finally, increasing the ethanol concentration from 10% to 14% led to a marked increase in the extraction of phenolic compounds for both types of wood. This result is expected since alcohol acts as a more efficient solvent for phenolic substances, enhancing their solubility and the solvent’s penetration into the wood matrix. Therefore, solutions with higher alcohol content tend to show greater extraction potential during aging.

Both French oak and Tajuva showed greater extraction of phenolic compounds after 180 and 360 days of aging compared to shorter periods, with consistent behavior across both hydroethanolic model systems. Therefore, the 360-day aging period was selected for subsequent analyses, as it provided the most comprehensive and representative extraction profile. Moreover, because the phenolic composition of French oak is already widely documented in the scientific literature, quantification and identification efforts in this study were focused exclusively on Tajuva, the primary subject of this investigation, to avoid redundancy and ensure a more meaningful contribution.

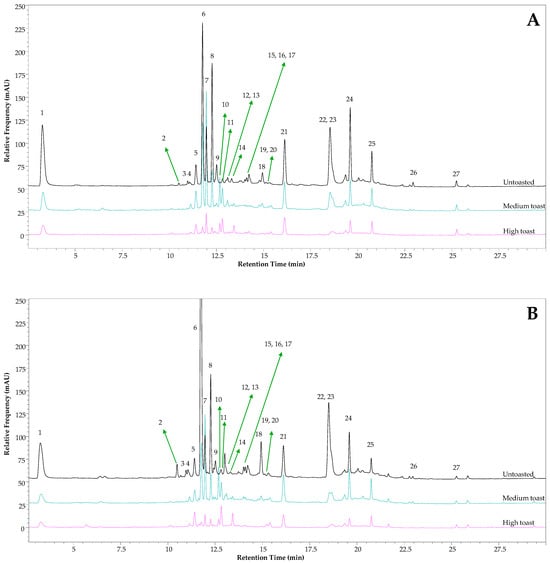

The investigation of the phytochemical profile revealed a diverse range of phenolic compounds in Tajuva extracts, including hydroxybenzoic and hydroxycinnamic derivatives, flavan-3-ols, flavonols, and other flavonoids (Figure 1 and Table 2). Among the identified compounds, quercetin, caffeic, gallic and syringic acids were the major constituents. Minor compounds such as vanillic acid, catechin, epicatechin, and naringenin-7-O-glucoside were also detected under specific toasting and ethanol conditions. These compounds are consistent with those previously reported in M. tinctoria heartwood, particularly flavonoids and phenolic acids associated with antioxidants and antimicrobial activities [16,17].

Figure 1.

Representative chromatograms of phenolic compound profiles of Tajuva wood chips in a model system with alcoholic degree 10% (A) and 14% (B) at three toasting levels. Information about peak numbers is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Spectral information and proposal of the identification and quantification of phenolic compounds from Tajuva wood chips in the model system with alcoholic degree 10% (v/v) and 14% (v/v) at three toasting levels.

Quantitatively, gallic and syringic acids exhibited the highest concentration among all hydroxybenzoic derivatives, particularly in the untoasted wood extracts, with mean values around 12.4 and 7.51 mg/L (10%) and 9.6 and 7.05 mg/L (14%), respectively. These results confirm that non-toasted Tajuva retains a greater proportion of extractable phenolic acids, typically derived from lignin and hydrolysable tannins [1,2]. Overall, increasing the toasting level consistently reduced hydroxybenzoic acid derivative concentrations (untoasted > medium > high toast), indicating thermal degradation of these compounds during heating, likely through decarboxylation and condensation reactions forming volatile phenolic derivatives such as vanillin or guaiacol [5,14,15]. Interestingly, vanillic acid exhibited notably higher values under medium toast conditions in both ethanol concentrations (7.14 mg/L at 10%; 6.18 mg/L at 14%). This pattern suggests the formation of thermally induced derivatives—possibly aldehydes or other aromatic degradation products from lignin syringyl and guaiacyl units—commonly associated with the generation of color and aroma precursors during the aging of alcoholic beverages [2,15,29].

For flavan-3-ols, represented mainly by catechin and epicatechin, only trace amounts were detected (<0.89 mg/L) in most treatments. This pattern suggests that toasting and prolonged exposure to ethanol promote oxidative polymerization of these compounds into condensed tannins or other derivatives not detected in the chromatographic window [3,6].

The compound tentatively identified as 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid showed a distinct pattern: its concentration decreased moderately with toasting, ranging from 1.86 ± 0.08 mg/L (UT, 10%) to 0.97 ± 0.03 mg/L (HT, 10%), and a similar trend was observed in the 14% ethanol model. This moderate reduction suggests partial stability of this molecule to thermal degradation compared to more labile acids [12].

Regarding the effect of ethanol concentration, the transition from 10% to 14% ethanol generally enhanced extraction for most analytes, confirming that ethanol acts as an efficient solvent for phenolic compounds by increasing wood permeability and solute solubility [4,10]. However, this effect was compound-dependent, with smaller gains observed for more polar acids. Additionally, Souza et al. (2025) [32] had already reported that higher ethanol content increases the solubility of more hydrophobic phenolic compounds, facilitating their extraction from the wood matrix, as observed with flavonols in the present study.

Overall, the phenolic profile of Tajuva demonstrates a rich composition dominated by phenolic acids and flavonols. The results highlight that untoasted or lightly toasted Tajuva wood provides a higher yield of low-molecular-weight phenolics, while medium toasting favors the formation of secondary aromatic compounds with potential sensory impact. These findings reinforce the suitability of M. tinctoria as a sustainable and distinctive alternative to oak for beverage aging, combining renewable sourcing with a unique chemical fingerprint capable of influencing both antioxidant and organoleptic properties of matured beverages [13,16,17].

From an industrial perspective, the phenolic-driven behavior observed for Maclura tinctoria wood suggests relevant potential for its application in alcoholic beverage aging processes. The high phenolic yields and faster extraction kinetics obtained using Tajuva chips indicate that this wood could be effectively employed in alternative aging strategies, such as the use of wood fragments in stainless steel tanks, which are already widely adopted by the wine, beer, and spirits industries. The enhanced release of phenolic acids and flavonoids, particularly under moderate toasting and higher ethanol content, may allow for shorter aging periods or reduced wood dosage while still achieving desirable chemical complexity. Additionally, the formation of thermally derived aromatic precursors under medium toasting conditions indicates that Tajuva wood may contribute not only to antioxidant capacity but also to sensory development, similarly to traditional oak. Considering its local availability, renewable sourcing, and chemical reactivity, M. tinctoria represents a promising option for producers seeking sustainable and cost-effective alternatives to imported oak, especially in regions where native wood utilization aligns with environmental and economic strategies. Nevertheless, further studies addressing sensory evaluation, scale-up feasibility, and regulatory aspects are required to support its industrial implementation.

4. Conclusions

The findings of this study reinforce that the combination of wood type, toasting level, and alcohol content plays a decisive role in determining the final chemical composition of the aged beverage. Moreover, native woods such as Maclura tinctoria (Tajuva) may represent technologically viable alternatives to traditional oak, depending on the desired sensory profile. This study demonstrated that Tajuva wood presents significant potential as a sustainable and efficient alternative to French oak for alcoholic beverage aging. The extraction kinetics revealed that both the type of wood and the toasting level markedly influenced the release of phenolic compounds, with Tajuva consistently exhibiting higher concentrations of total and individual phenolics than oak across all aging times and ethanol levels. Untoasted or medium toasted samples promoted greater extraction of phenolic acids such as gallic, syringic and caffeic acids, while medium toasting favored the formation of thermally derived compounds with possible sensory relevance, such as vanillic acid. Higher ethanol concentration (14%) also enhanced extraction efficiency, confirming the solvent’s role in improving wood–liquid interactions.

These results highlight that Tajuva wood not only provides a rich and distinctive phenolic composition but also contributes to the development of antioxidant and potentially flavor-active compounds in alcoholic matrices. Considering its local availability, renewable sourcing, and chemical performance, M. tinctoria emerges as a promising and eco-efficient alternative for wood aging processes, aligning with current trends in sustainable beverage production.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/beverages12010010/s1. Table S1: Validation parameters for the HPLC-DAD method for determining phenolic compounds in wood chips.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.W.F., T.C.T., V.C.B. and C.K.S.; methodology, F.W.F., C.O.d.S., J.P.F., T.C.T. and V.C.B.; validation, F.W.F., C.O.d.S., J.P.F., T.C.T. and V.C.B.; formal analysis, F.W.F., C.O.d.S., J.P.F., T.C.T. and V.C.B.; investigation, F.W.F., C.O.d.S., J.P.F., T.C.T., V.C.B., D.G.F., S.S. and C.K.S.; resources, V.C.B. and C.K.S.; data curation, F.W.F., V.C.B., S.S. and C.K.S.; writing—original draft preparation, F.W.F. and D.G.F.; writing—review and editing, D.G.F. and S.S.; visualization, F.W.F., C.O.d.S., J.P.F., T.C.T., V.C.B., D.G.F., S.S. and C.K.S.; resources, V.C.B. and C.K.S.; supervision, V.C.B., S.S. and C.K.S.; project administration, C.K.S.; funding acquisition, V.C.B. and C.K.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was financed in part by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq, Brazil), Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES, Brazil), and Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul (FAPERGS, RS, Brazil).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the authors used ChatGPT (Version GPT-5.2; OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA) for spelling and grammar correction, as well as for writing the text, ensuring fluency and logical sequence. The authors reviewed and edited the result and assume full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| HPLC | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| DAD | Diode Array Detector |

| LC | Liquid Chromatography |

| MS/MS | Tandem Mass Spectrometry |

| LC–ESI–IT–MS/MS | Liquid Chromatography–Electrospray Ionization–Ion Trap Mass Spectrometry |

| SPE | Solid-Phase Extraction |

| PTFE | Polytetrafluoroethylene |

| LOD | Limit of Detection |

| LOQ | Limit of Quantification |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| CV | Coefficient of Variation |

| UV-VIS | Ultraviolet–Visible |

| RT | Retention Time |

| GAE | Gallic Acid Equivalent |

| FCR | Folin–Ciocalteu Reagent |

| NF | Non-fragmented |

| UT | Untoasted |

| MT | Medium toast |

| HT | High toast |

References

- Castro-Vázquez, L.; Alañón, M.E.; Ricardo-Da-Silva, J.M.; Pérez-Coello, M.S.; Laureano, O. Study of Phenolic Potential of Seasoned and Toasted Portuguese Wood Species (Quercus pyrenaica and Castanea sativa). J. Int. Sci. Vigne Vin. 2013, 47, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Gil, A.; Cadahía, E.; Fernández de Simón, B.; Gutiérrez-Gamboa, G.; Nevares, I.; del Álamo-Sanza, M. Phenolic and Volatile Compounds in Quercus humboldtii Bonpl. Wood: Effect of Toasting with Respect to Oaks Traditionally Used in Cooperage. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 99, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordão, A.M.; Laureano, O. Extraction of Some Ellagic Tannins and Ellagic Acid from Oak Wood Chips (Quercus pyrenaica L.) in Model Wine Solutions: Effect of Time, pH, Temperature and Alcoholic Content. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2005, 26, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordão, A.M.; Correia, A.C.; DelCampo, R.; González SanJosé, M.L. Antioxidant Capacity, Scavenger Activity, and Ellagitannins Content from Commercial Oak Pieces Used in Winemaking. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2012, 235, 817–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prida, A.; Chatonnet, P. Impact of Oak-Derived Compounds on the Olfactory Perception of Barrel-Aged Wines. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2010, 61, 408–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyler, P.; Angeloni, L.H.P.; Alcarde, A.R.; da Cruz, S.H. Effect of Oak Wood on the Quality of Beer. J. Inst. Brew. 2015, 121, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Abda, E.; Bentis, A.; Amaral-Labat, G.; Pizzi, A.; Lacoste, C.; Koubaa, A.; Braghiroli, F.L. Bark Tannins: Extraction Methods, Characterization, and Reactivity. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 235, 121745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortoletto, A.M. Composição Química de Cachaça Maturada com Lascas Tostadas de Madeira de Carvalho Proveniente de Diferentes Florestas Francesas. Master’s Thesis, Universidade de São Paulo, Piracicaba, Brazil, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago, W.D.; Cardoso, M.G.; Nelson, D.L. Cachaça Stored in Casks Newly Constructed of Oak (Quercus sp.), Amburana (Amburana cearensis), Jatobá (Hymenaeae carbouril), Balsam (Myroxylon peruiferum) and Peroba (Paratecoma peroba): Alcohol Content, Phenol Composition, Colour Intensity and Dry Extract. J. Inst. Brew. 2017, 123, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortoletto, A.M.; Alcarde, A.R. Congeners in Sugar Cane Spirits Aged in Casks of Different Woods. Food Chem. 2013, 139, 695–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago, W.D.; Cardoso, M.G.; Santiago, J.D.A.; Gomes, M.S.; Rodrigues, L.M.A.; Brandão, R.M.; Cardoso, R.R.; Ávila, G.B.; Silva, B.L.; Caetano, A.R.S. Comparison and Quantification of the Development of Phenolic Compounds during the Aging of Cachaça in Oak (Quercus sp.) and Amburana (Amburana cearensis) Barrels. Food Chem. 2014, 158, 3140–3150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karvela, E.; Makris, D.P.; Kefalas, P.; Moutounet, M. Extraction of Phenolics in Liquid Model Matrices Containing Oak Chips: Kinetics, LC–MS Characterisation and Association with In Vitro Antiradical Activity. Food Chem. 2008, 110, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortes, J.P.; Franco, F.W.; Baranzelli, J.; Ugalde, G.A.; Ballus, C.A.; Rodrigues, E.; Mazutti, M.A.; Somacal, S.; Sautter, C.K. Enhancement of the Functional Properties of Mead Aged with Oak (Quercus) Chips at Different Toasting Levels. Molecules 2023, 28, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatonnet, P.; Escobessa, J. Impact of Toasting Oak Barrels on the Presence of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Wine. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 10351–10358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández de Simón, B.; Muiño, I.; Cadahía, E. Characterization of Volatile Constituents in Commercial Oak Wood Chips. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 9587–9596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cioffi, G.; Escobar, L.M.; Braca, A.; De Tommasi, N. Antioxidant chalcone glycosides and flavanones from Maclura (Chlorophora) tinctoria. J. Nat. Prod. 2003, 66, 1061–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamounier, K.C.; Cunha, L.C.S.; de Morais, S.A.L.; de Aquino, F.J.T.; Chang, R.; do Nascimento, E.A.; de Souza, M.G.M.; Martins, C.H.G.; Cunha, W.R. Chemical analysis and study of phenolics, antioxidant activity, and antibacterial effect of the wood and bark of Maclura tinctoria (L.) D. Don ex Steud. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 2012, 451039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coldebella, R.; Gentil, M.; Berger, C.; Costa, H.W.D.; Pedrazzi, C.; Labidi, J.; Delucis, R.A.; Missio, A.L. Nanofibrillated cellulose-based aerogels functionalized with Tajuva (Maclura tinctoria) heartwood extract. Polymers 2021, 13, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintero-Rincón, P.; Pájaro-González, Y.; Diaz-Castillo, F. Maclura tinctoria (L.) D. Don ex Steud. (Moraceae): A review of the advances in ethnobotanical knowledge, phytochemical composition, and pharmacological potential. Adv. Tradit. Med. 2025, 25, 331–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos Filho, E.M.; Sartorelli, P.A.R. Guide to Trees with Economic Value; Agroicone: São Paulo, Brazil, 2015; Available online: https://www.bibliotecaagptea.org.br/agricultura/biologia/livros/GUIA%20DE%20ARVORES%20COM%20VALOR%20ECONOMICO.pdf (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- Carpena, M.; Pereira, A.G.; Prieto, M.A.; Simal-Gandara, J. Wine Aging Technology: Fundamental Role of Wood Barrels. Foods 2020, 9, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Orthofer, R.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M. Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of Folin–Ciocalteu Reagent. Methods Enzymol. 1999, 299, 152–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Saona, L.E.; Wrolstad, R.E. Extraction, Isolation, and Purification of Anthocyanins. Curr. Protoc. Food Anal. Chem. 2001, F1.1.1–F1.1.11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quatrin, A.; Pauletto, R.; Maurer, L.H.; Minuzzi, N.; Nichelle, S.N.; Carvalho, J.F.C.; Maróstica, M.R.; Rodrigues, E.; Bochi, V.C.; Emanuelli, T. Characterization and quantification of tannins, flavonols, anthocyanins and matrix-bound polyphenols from jaboticaba fruit peel: A comparison between Myrciaria trunciflora and M. Jaboticaba. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2019, 78, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Council for Harmonisation (ICH). Validation of Analytical Procedures: Text and Methodology Q2(R1); ICH: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005; Volume 2005, Available online: https://database.ich.org/sites/default/files/Q2%28R1%29%20Guideline.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2022).

- Soares, B.; García, R.; Freitas, A.M.; Cabrita, M. Phenolic compounds released from oak, cherry, chestnut and robinia chips into a syntethic wine: Influence of toasting level. Cienc. Tec. Vitivinic. 2012, 27, 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, R.; Soares, B.; Dias, C.B.; Freitas, A.M.C.; Cabrita, M.J. Phenolic and furanic compounds of Portuguese chestnut and French, American and Portuguese oak wood chips. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2012, 235, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echave, J.; Barral, M.; Fraga-Corral, M.; Prieto, M.A.; Simal-Gándara, J. Bottle Aging and Storage of Wines: A Review. Molecules 2021, 26, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatonnet, P.; Dubourdie, D.; Boidron, J.-n.; Pons, M. The origin of ethylphenols in wines. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1992, 60, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Gil, A.; del Alamo-Sanza, M.; Sánchez-Gómez, R.; Nevares, I. Alternative Woods in Enology: Characterization of Tannin and Low Molecular Weight Phenol Compounds with Respect to Traditional Oak Woods. A Review. Molecules 2020, 25, 1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sohly, H.N.; Joshi, A.; Li, X.C.; Ross, S.A. Flavonoids from Maclura tinctoria. Phytochemistry 1999, 52, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, T.F.C.d.; Melo Miranda, B.; Colivet Briceno, J.C.; Gómez-Estaca, J.; Alves da Silva, F. The Science of Aging: Understanding Phenolic and Flavor Compounds and Their Influence on Alcoholic Beverages Aged with Alternative Woods. Foods 2025, 14, 2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.