Abstract

Photosafety assessments are a key requirement for the safe development of pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, and agrochemicals. Although in vitro methods are widely used for phototoxicity and photoallergy testing, their limited applicability and predictive power often necessitate supplemental in vivo studies. To address this, we developed the PhotoChem Reference Chemical Database, comprising 251 reference compounds with curated data from in vitro, in vivo, and human studies. Using this database, we evaluated the predictive capacity of three OECD in vitro test guidelines—TG 432 (3T3 NRU), TG 495 (ROS assay), and TG 498 (reconstructed human epidermis)—by comparing the results against human and animal data. Against human reference data, all three test methods showed high sensitivity (≥82.6%) and strong overall accuracy: TG 432 (accuracy: 94.2% (49/52)), TG 495 (100% (27/27)), and TG 498 (86.7% (26/30)). In comparison with animal data, sensitivity remained high for all tests (≥92.0%), while specificity varied: TG 432 (54.3% (19/35)), TG 495 (63.6% (7/11)), and TG 498 (90.5% (19/21)). TG 498 demonstrated the most balanced performance in both sensitivity and specificity across datasets. We also analyzed 106 drug approvals from major regulatory agencies to assess real-world application of photosafety testing. Since the mid-2000s, the use of in vitro phototoxicity assays has steadily increased in Korea, particularly following the 2021 revision of the MFDS regulations. Test method preferences varied by region, with 3T3 NRU and ROS assays most widely used to evaluate phototoxicity, while photo-LLNA and guinea pig tests were frequently employed for photoallergy assay. Collectively, this study provides a valuable reference for optimizing test method selection and supports the broader adoption of validated, human-relevant non-animal photosafety assessment strategies.

1. Introduction

Photosafety testing primarily aims to evaluate two major aspects: phototoxicity and photoallergy. In pharmaceuticals, photosafety assessment refers to an integrated process that includes photochemical characterization, nonclinical testing, and human safety information, as outlined in the ICH S10 guideline (Photosafety Evaluation of Pharmaceuticals) [1]. The objective of a photosafety evaluation is to minimize the potential risks of chemicals caused by concomitant light exposure to humans. Phototoxicity is defined as a nonimmunologic skin reaction that occurs when reactive chemicals and sunlight interact simultaneously. Such reactions occur shortly after concomitant exposure to photoreactive chemicals and light and often resemble moderate to severe sunburns. In contrast, photoallergy is an acquired immune-mediated reaction in which a photoactive substance activated by sunlight forms an allergenic hapten. This reaction is triggered by either antibody-mediated (immediate) or cell-mediated (delayed) immune responses. Unlike phototoxicity, photoallergy can occur with significantly lower energy exposure. When induced by exogenous substances, it almost exclusively manifests as delayed-type hypersensitivity (type IV). Additionally, this reaction requires an induction period before clinical symptoms appear [2]. This reaction requires a sensitization phase before clinical symptoms manifest [3]. Clinically, photoallergic reactions commonly present as erythema, pruritus, and vesicular lesions, often accompanied by skin lichenification or desquamation. These responses may resemble urticarial or lichenoid eruptions. In particular, flat-topped, keratinized lesions are a characteristic feature of such reactions.

The photoreactive potential of a chemical can be identified by evaluating its absorption in the ultraviolet (UV) spectrum. To elicit a phototoxic or photoallergic response, a chemical must exhibit sufficient light absorption (≥1000 L/mol·cm) within natural sunlight (290–700 nm) [1].

The term photosensitization is often used as a general descriptor for all light-induced tissue responses. However, to ensure clarity between phototoxicity and photoallergy, ICH S10 discourages the use of this term. Accordingly, this study will exclusively focus on the evaluation of phototoxic and photoallergic responses. When a chemical is identified as photoreactive, it is assessed using specific toxicological test methods designed to evaluate both phototoxicity and photoallergy. Key considerations for identifying a photosafety hazard include (1) light absorption within the natural sunlight spectrum (290–700 nm), (2) the generation of reactive oxygen species upon UV–visible light exposure, and (3) adequate distribution to light-exposed tissues (e.g., skin and eyes). If a compound does not meet at least one of these criteria, it is unlikely to pose a direct photosafety concern. Although indirect mechanisms may increase photosensitivity (e.g., metabolic activation), they are not currently addressed due to the lack of established test methods [3]. Currently, in vitro photosafety assessments are primarily focused on phototoxicity and ROS evaluations as specified in OECD and ICH guidelines replacing in vivo phototoxicity tests. However, photoallergy evaluation still requires in vivo experiments, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Phototoxicity and Photoallergy test methods.

While in vitro photosafety tests considerably reduced the use of in vivo tests, comprehensive photosafety assessments still need in vivo tests due to the limitation of in vitro tests in the applicability domain and predictive capacity, demanding novel photosafety testing methods capable of accurately identifying chemicals that induce phototoxic or photoallergic reactions. Here, we compiled a comprehensive reference chemical database of 251 reference chemicals, including 59 phototoxic, 26 non-phototoxic, and 4 photoallergenic substances verified in humans, for the development and evaluation of alternative methods for phototoxic and photoallergy tests.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Construction of Phototoxicity Reference Substance Database

To support the research and validation of new phototoxicity test methods, a phototoxic reference chemical database was established. Each chemical was documented with key identifiers such as CAS numbers, physicochemical properties, and UV absorption parameters. To facilitate the development of testing methods across diverse chemical categories, information on their usage classification—pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, industrial chemicals, and agrochemicals—was also included. Both in vitro and in vivo data were collected. Importantly, test results from the OECD Test Guidelines (TGs) and human patch tests were incorporated to evaluate the predictive power and consistency between testing methodologies.

2.2. Phototoxicity Testing Methods Used for Pharmaceuticals

The phototoxicity testing methods used in the nonclinical stages of pharmaceutical development were investigated through searching regulatory approval documents and assessment reports from the U.S. FDA, Japan’s PMDA, the EMA, and South Korea’s MFDS.

2.3. Comparison of In Vivo and In Vitro Data of Phototoxicity Reference Chemicals

To evaluate the predictive performance and reliability of in vitro phototoxicity test methods, a comparative analysis was conducted using 252 reference chemicals with available in vivo or human data. The in vitro test methods were based on three internationally validated OECD guidelines (Table 2).

Table 2.

Criteria for phototoxicity prediction according to OECD Test Guidelines.

Only chemicals for which both in vitro and in vivo test results were available were included in the comparative analysis. Each compound was classified as either phototoxic (PT) or non-phototoxic (NPT) based on the outcomes of both test types. The sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy were calculated to assess the performance of each in vitro method.

2.4. Photochemical Properties

To evaluate the potential for light-induced reactivity, the primary criterion was whether the chemical absorbs light within the 290–700 nm wavelength range. A chemical was considered unlikely to cause direct phototoxicity if it exhibited a molar extinction coefficient (MEC) of less than 1000 L/mol·cm in this range. That is, if the chemical had an MEC value below 1000 L/mol·cm between 290 and 700 nm and lacked additional supportive data, it was deemed not to pose a photosafety concern in humans, according to ICH S10 guidelines [1].

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Reference Chemicals in the PhotoChem Database

A total of 251 reference chemicals were collected and classified based on their photo-toxicity and photosensitization profiles. These compounds are widely used in various industries, including pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, and agriculture, where photoreactivity under ultraviolet (UV) exposure plays a significant role in safety evaluation.

For each chemical, various physical properties were recorded, including physical state; molar absorbance (ε); maximum UV absorption wavelength (λmax); and test results across human, animal, and in vitro models.

To better understand the material characteristics, the physical states of all 251 chemicals were analyzed. As shown in Table 3, the majority of the chemicals were in solid form (n = 218, 86.9%), followed by liquids (n = 26, 10.4%). Gels accounted for two chemicals, and viscous or oil-based chemicals, categorized as “Other,” also accounted for two chemicals (0.8%), while three chemicals were labeled as “Unknown” due to the absence of a definitive classification (1.2%).

Table 3.

List of reference chemicals in the PhotoChem DB.

3.2. Human vs. Animal Test Results for Reference Test Chemicals

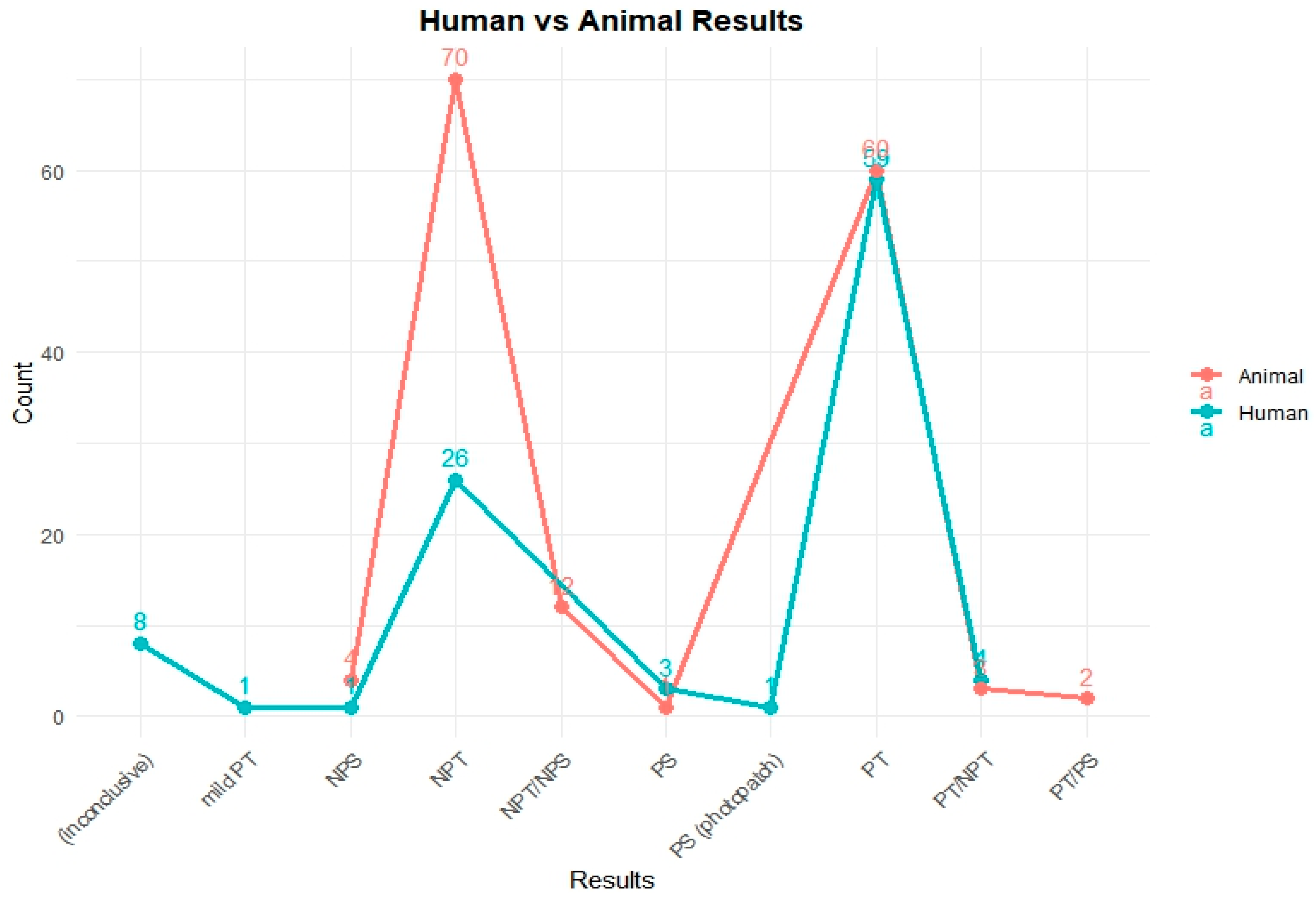

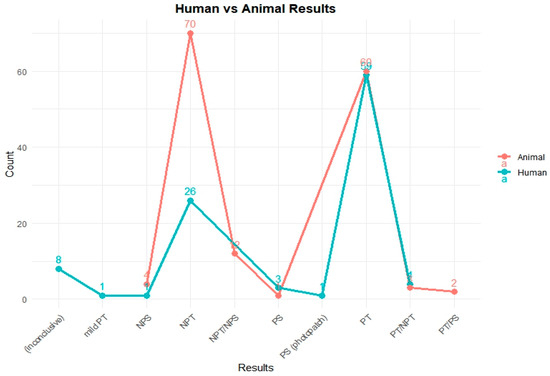

To assess the phototoxic potential of the reference chemicals in human models, available in vivo test data were categorized by their respective outcomes. Figure 1 illustrates the comparative distribution of test results from human and animal studies for 251 chemicals.

Figure 1.

Comparison of photosafety results from human and animal tests in the PhotoChem DB. This figure shows the photosafety results for reference chemicals based on human and animal test data. In animal studies, most compounds were clearly categorized as either non-phototoxic (NPT) or phototoxic (PT). In contrast, human data included a broader range of outcomes such as inconclusive results, mild reactions, or photosensitization (photopatch), reflecting the complexity of clinical assessments.

A total of 103 chemicals out of the PhotoChem DB have human test results: 59 chemicals were identified as phototoxic (PT); 26 chemicals were categorized as non-phototoxic (NPT); 8 chemicals were reported as inconclusive; 4 chemicals were given a PT/NPT; 3 chemicals were labeled as photosensitive (PS); and a single case each was observed for mild phototoxicity (mild PT), non-photosensitization (NPS), and PS (photo patch) testing, with each indication a specialized or rare response type.

Animal model studies were also reviewed to evaluate the phototoxicity potential of the 251 reference chemicals. These models provide complementary data for human studies and are particularly important when human testing is ethically or practically limited.

As depicted in Figure 1, the animal testing results reveal the following distribution: 70 chemicals were classified as non-phototoxic (NPT), 60 chemicals showed a positive phototoxicity (PT), 12 chemicals received mixed classifications (NPT/NPS), 4 chemicals were marked as non-photosensitive (NPS), 3 chemicals were classified as PT/NPT, 2 chemicals were classified as PT/PS, and 1 chemical was confirmed as photosensitive (PS).

3.3. Correlation of Human Test Data with In Vivo or In Vitro Tests

The classification results for phototoxicity and photosensitization from human and animal studies showed substantial agreement, although some variation in sensitivity was observed. Out of 251 total chemicals, those lacking paired results across test types were excluded from the analysis. Sensitivity, specificity, precision, and accuracy were evaluated accordingly (Table 4 and Table 5).

Table 4.

Predictive performance of in vivo phototoxicity tests compared with human patch tests.

Table 5.

Predictive performance of in vitro phototoxicity tests compared with human test results.

Table 5 presents the predictive performance of three OECD test methods (TG 432 (3T3 Neutral Red Uptake phototoxicity test), TG 495 (Reactive Oxygen Species assay), and TG 498 (Reconstructed Human Epidermis model)) against human or animal tests. These results indicate that while the classification of non-phototoxic chemicals aligns with some in vivo data, inconsistencies across untested or conflicting chemicals (e.g., PT and PT/NPT) highlight the need for comprehensive and standardized in vivo testing to improve the reliability of non-phototoxic classifications.

Overall, the findings emphasize the importance of integrating both human and animal data to achieve more accurate and reliable assessments of phototoxicity and photosensitization. Leveraging the strengths of each model can enhance predictive performance and improve overall safety evaluation strategies.

3.4. Analysis of Photosafety Testing Used in Drug Approvals

In recent decades, phototoxicity and photosensitization testing have gained increasing importance in pharmaceutical safety assessments. To examine how these tests are implemented in regulatory practice, we analyzed drug approvals from major regulatory agencies including the United States Food and Drug Administration (U.S. FDA), Japan’s Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA), the European Medicines Agency (EMA), and South Korea’s Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (MFDS). Based on compiled data from approved drug dossiers, we assessed the frequency, testing strategies, and adoption trends of photosafety evaluations.

The analysis revealed a growing adoption of photosafety testing across all agencies. In particular, data from Korea’s MFDS showed that photosafety test results were not consistently included in approval documents prior to the revision of its regulatory guidelines on 11 November 2021. At that time, certain nonclinical safety assessments, including photosafety tests, were exempted for specific categories of drugs. However, following the regulatory revision, phototoxicity and photosensitization testing became mandatory components of nonclinical safety evaluations. This regulatory shift highlights the increasing importance placed on photosafety assessments in Korea and aligns with the global trend toward comprehensive photoreactivity risk management.

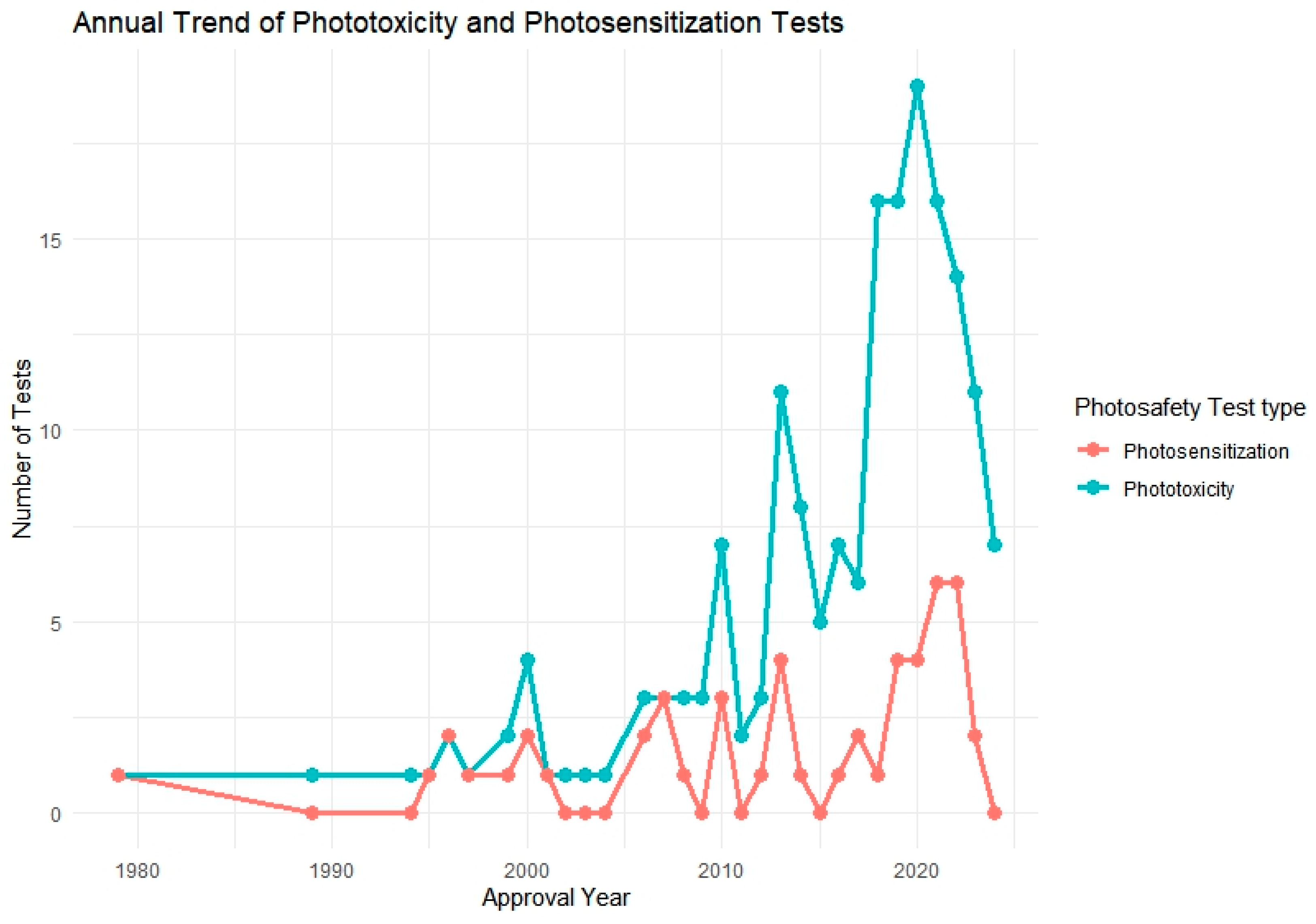

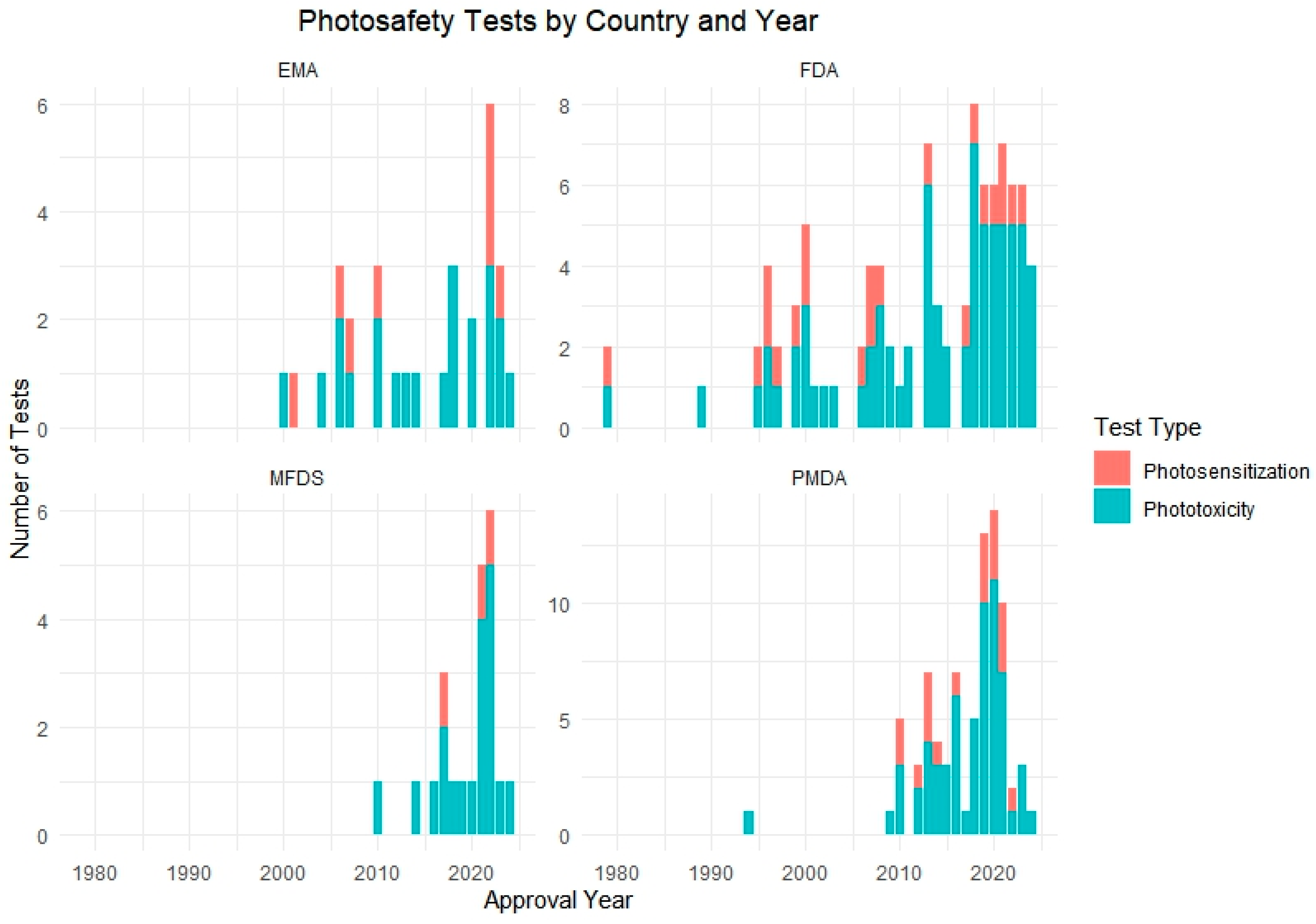

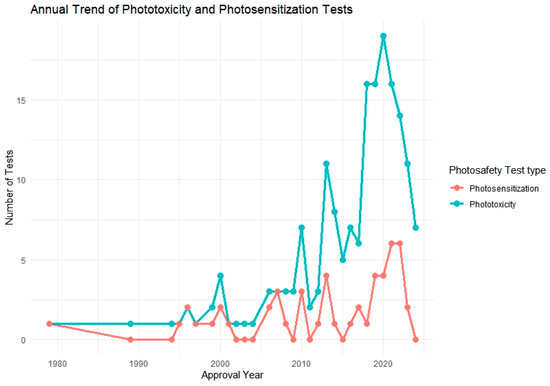

Following this, we further analyzed a total of 106 approved pharmaceutical products that included photosafety assessments, focusing on their annual adoption patterns and the specific test methods used. To visualize this trend, we generated a yearly distribution graph showing the implementation of phototoxicity and photosensitization testing over time (Figure 2). In addition, test method utilization was analyzed by regulatory authority, including the FDA, PMDA, EMA, and MFDS, to assess differences in test preferences among countries (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Annual trend of phototoxicity and photosensitization testing among approved pharmaceutical products (n = 106). The graph illustrates the increasing frequency of photosafety testing over the years, particularly for phototoxicity since the mid-2000s.

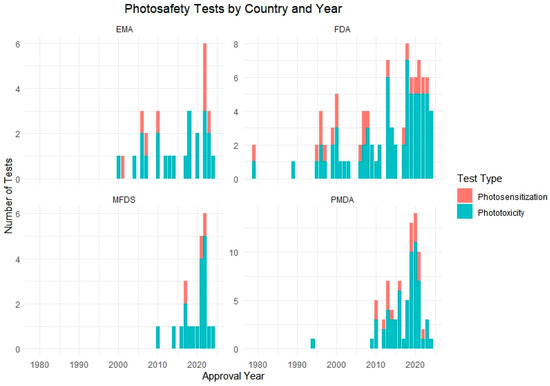

Figure 3.

Number of phototoxicity and photosensitization tests conducted by country and year. The chart displays the test method distribution across four regulatory authorities: the FDA, PMDA, EMA, and MFDS.

The analysis revealed a notable increase in the application of phototoxicity tests beginning in the mid-2000s, followed by a gradual rise in photosensitization testing in more recent years. Regionally, the PMDA and FDA showed the highest number of total test submissions, while MFDS data showed a steep increase post-2021. Across agencies, 3T3 NRU, ROS assays, and RHE-based models were most commonly used for phototoxicity, whereas LLNA and guinea pig-based protocols were predominantly used for photosensitization.

Figure 2 illustrates the annual trend in phototoxicity and photosensitization testing from 1979 to 2024, based on data extracted from 106 approved pharmaceutical products that included photosafety evaluations. During the early years of the dataset, reports of both phototoxicity and photosensitization testing were infrequent or absent, likely due to the absence of standardized regulatory requirements or test guidelines during that time.

A notable shift occurred beginning in the mid-2000s, with a steady increase in phototoxicity test implementation. This upward trend culminated between 2018 and 2021, during which over 18 phototoxicity assessments were recorded in a single year. This surge may be attributed to the widespread regulatory adoption of OECD TG 432 and increased emphasis on nonclinical photosafety data in global drug development and review processes.

In contrast, photosensitization testing exhibited a more gradual increase, with a relatively small number of cases—typically fewer than five per year—reported since 2010. This modest rise suggests that photosensitization assessments are applied more selectively, potentially limited to compounds with specific structural alerts, photoreactive moieties, or UV absorption profiles. The overall pattern reflects a growing awareness of photosafety considerations and regulatory alignment over time, particularly for phototoxicity.

Figure 3 presents a cumulative analysis of photosafety testing conducted by regulatory authority across four countries: the United States (the FDA), Japan (the PMDA), the European Union (the EMA), and South Korea (the MFDS). The data shows a distinct pattern in how each country has adopted and implemented phototoxicity and photosensitization testing in their regulatory processes over time.

The PMDA and FDA demonstrated relatively early adoption, with consistent test submissions reported since the mid-2000s. In contrast, data from the EMA showed a gradual increase, reflecting more selective application based on compound characteristics or risk assessment strategy. The most prominent change was observed in Korea’s MFDS, where a sharp rise in test submissions occurred after 2021, coinciding with the regulatory amendment that made photosafety testing mandatory for new drug applications.

This country-specific breakdown illustrates differing timelines and regulatory emphases in adopting photosafety tests, highlighting the importance of harmonized global guidelines and the evolving role of photoreactivity evaluation in drug approval pathways.

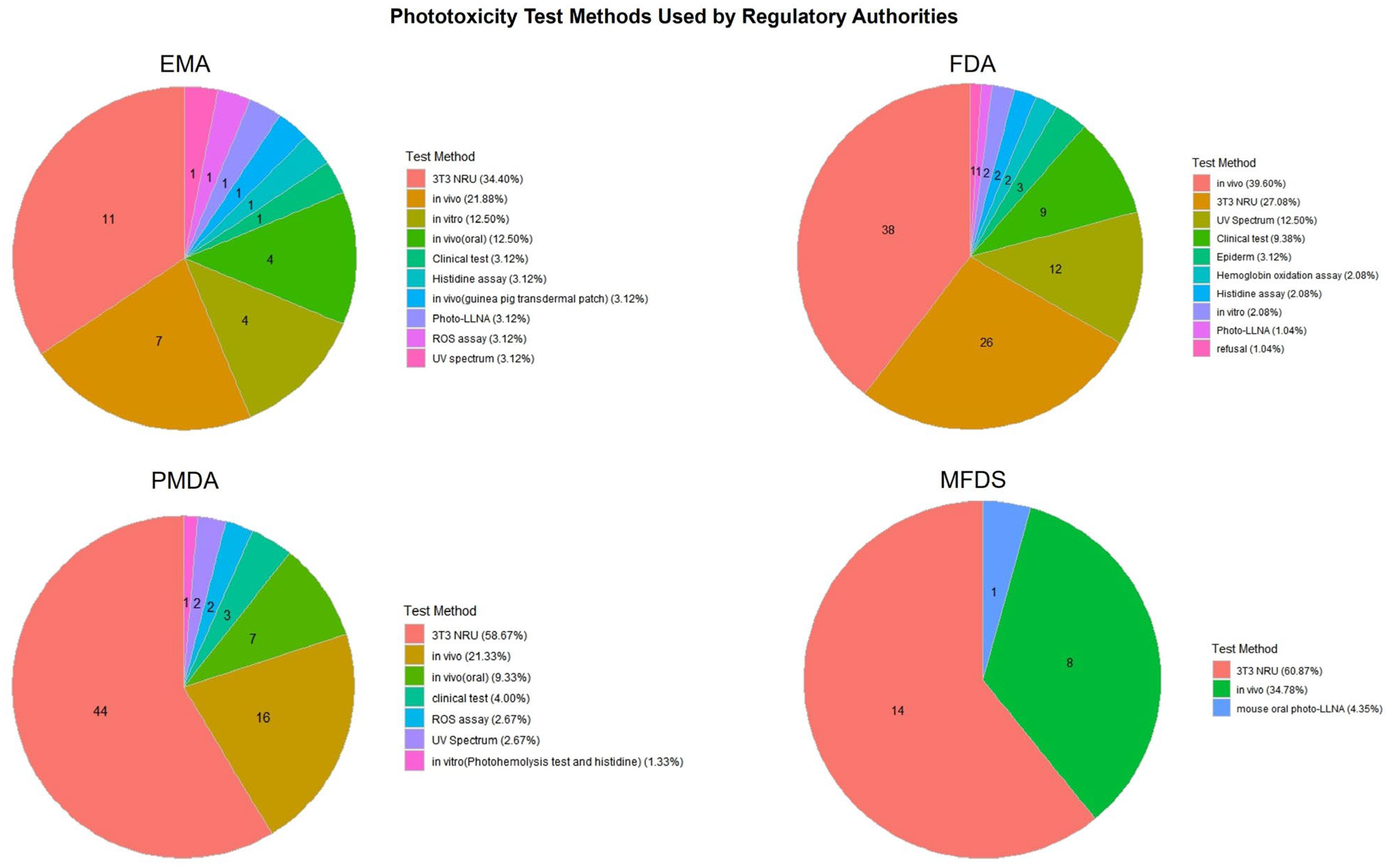

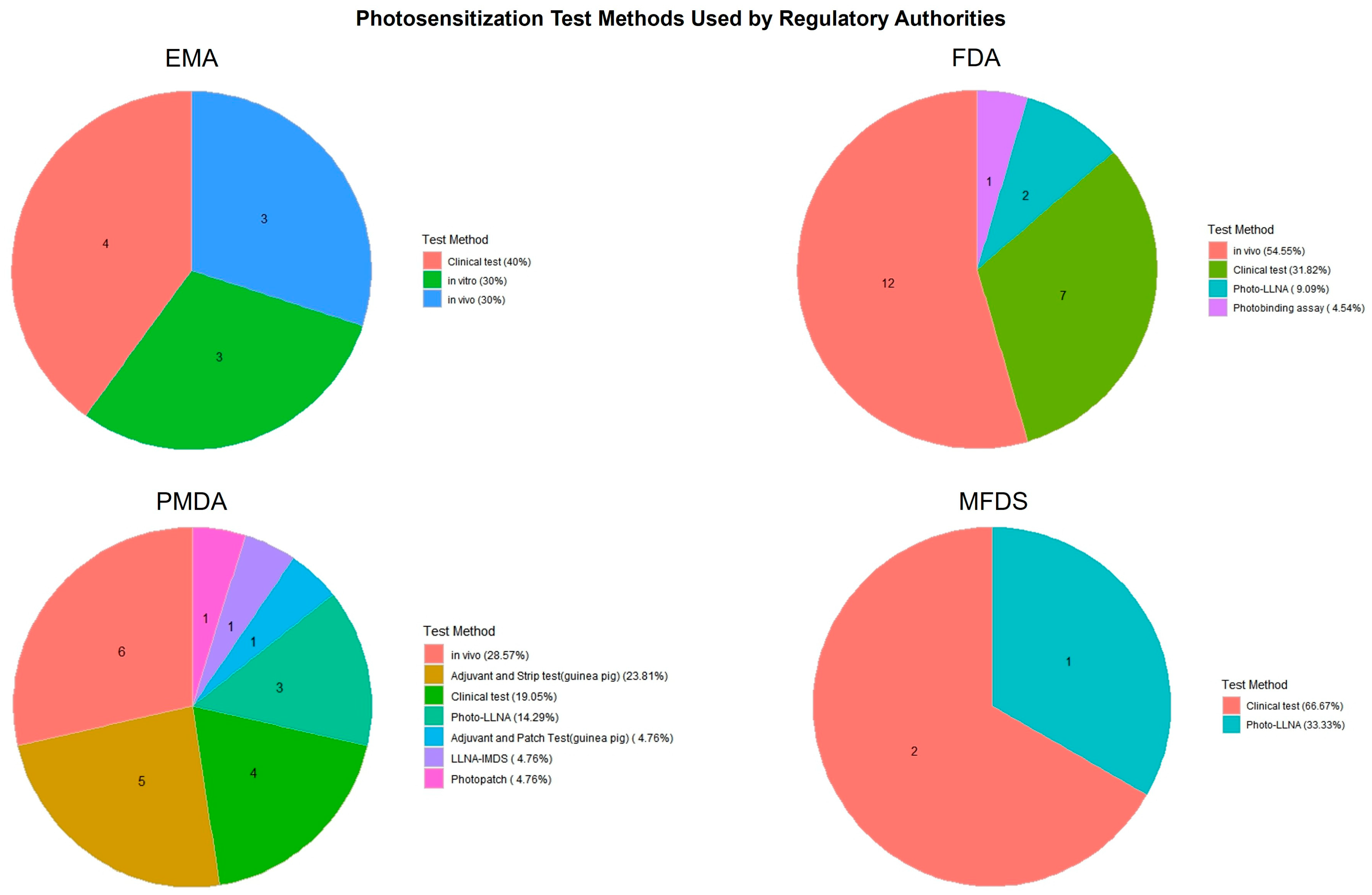

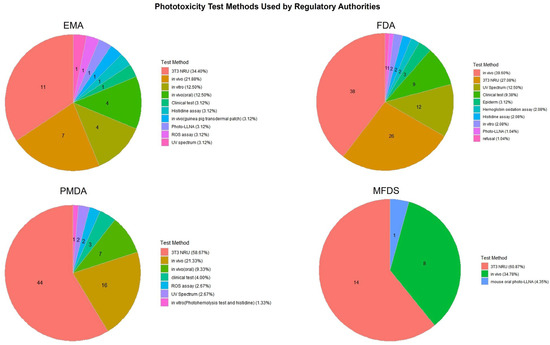

Figure 4 and Figure 5 present a comparative overview of phototoxicity and photosensitization test methods employed by four major regulatory agencies: the EMA, FDA, PMDA, and MFDS. These pie charts illustrate how each country distributes its use of test strategies for photosafety assessments based on approved pharmaceutical dossiers.

Figure 4.

Distribution of phototoxicity test methods used in pharmaceutical approvals by country. The chart compares the types of phototoxicity test methods adopted by four major regulatory authorities (the EMA, FDA, PMDA, MFDS), illustrating differences in testing strategies and preferences for alternative versus traditional approaches.

Figure 5.

Distribution of photosensitization test methods used in pharmaceutical approvals by country. This figure highlights the diversity of test types adopted for photosensitization assessment across the EMA, FDA, PMDA, and MFDS, indicating variation in clinical, in vivo, and alternative testing practices.

In phototoxicity evaluations (Figure 4), the 3T3 NRU test method was the most frequently applied across all agencies, particularly by the PMDA (58.67%) and EMA (34.40%). The FDA showed more diversified usage, including the clinical test, UV spectrum analysis, and hemoglobin oxidation methods. The MFDS primarily relied on in vivo studies and the 3T3 NRU test, reflecting its recent emphasis on incorporating alternative methods.

In contrast, photosensitization testing (Figure 5) exhibited greater heterogeneity across agencies. The FDA and MFDS predominantly used in vivo tests and clinical tests, while the PMDA applied a wider range of methods, including in vivo tests, Photo-LLNA, and photopatch testing. The EMA utilized a more balanced mix of in vivo, in vitro, and clinical approaches. These results suggest differences in regulatory preferences and test accessibility, as well as varying degrees of reliance on traditional versus alternative methods.

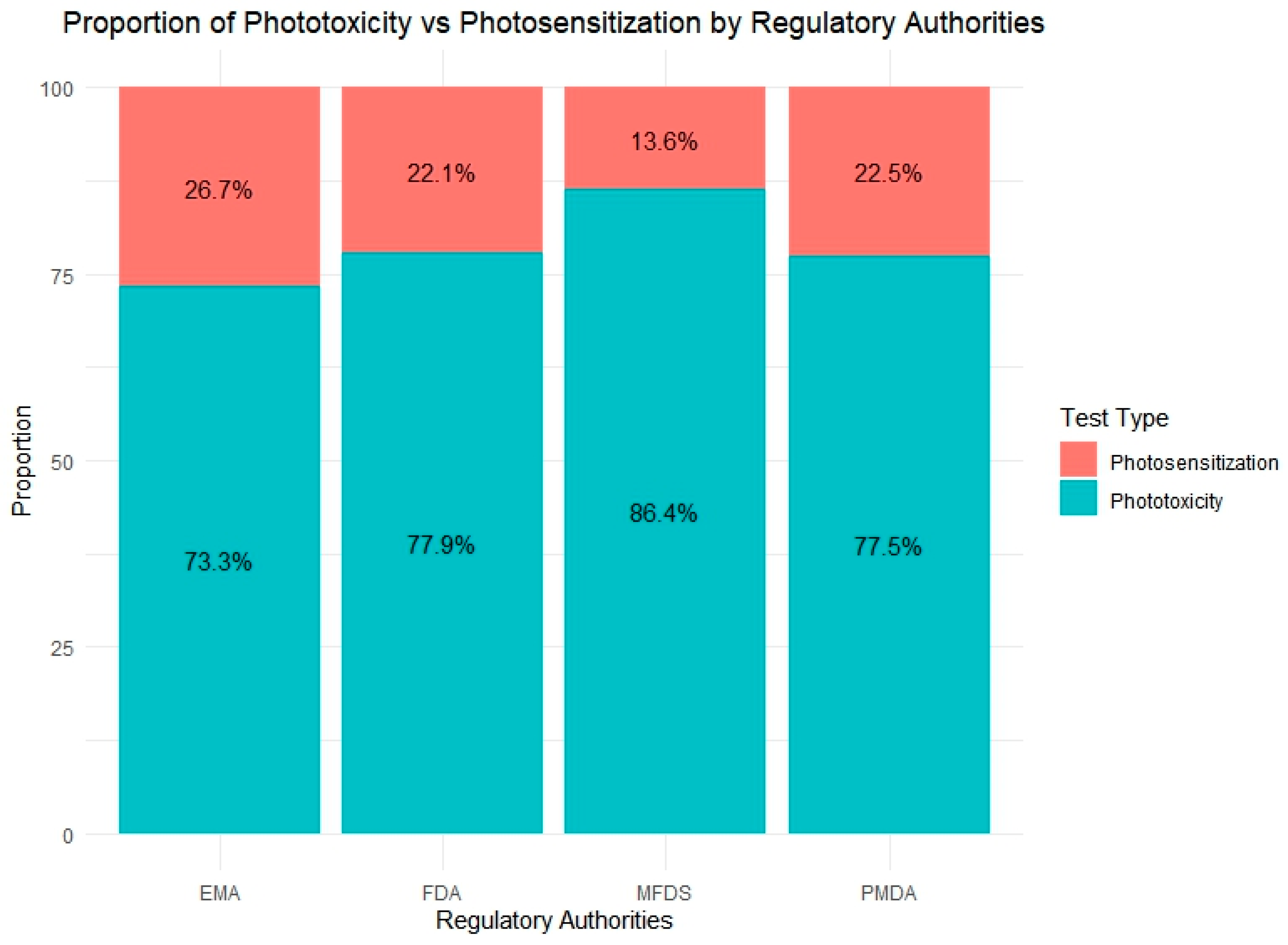

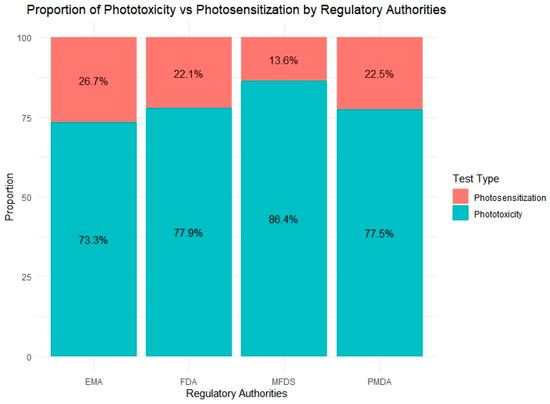

Figure 6 provides a comparative overview of the relative proportion of phototoxicity and photosensitization tests conducted by four regulatory agencies: the EMA, FDA, PMDA, and MFDS. Across all countries, phototoxicity assessments represented the dominant form of photosafety testing, reflecting its broader regulatory adoption and the availability of validated test guidelines such as OECD TG 432.

Figure 6.

Distribution of photosafety test types submitted to four regulatory agencies (the EMA, FDA, PMDA, MFDS). Phototoxicity tests accounted for the majority of evaluations across all agencies, with the MFDS showing the highest proportion (86.4%). In contrast, the EMA reported the highest relative use of photosensitization tests (29%), indicating varying emphasis on test types among regulatory bodies.

Among the agencies, the MFDS reported the highest proportion of phototoxicity testing (86.4%), which may reflect its more recent enforcement of standardized safety requirements and a preference for phototoxicity evaluation during initial risk screening. In contrast, the EMA exhibited the greatest use of photosensitization tests (26.7%), indicating a relatively broader application or heightened regulatory interest in photoallergy assessments. The FDA and PMDA showed similar test ratios, with phototoxicity accounting for approximately 77% of their total photosafety submissions. These findings suggest that approaches to photosafety assessment vary among regulatory agencies.

4. Discussion

This study highlights the need for a harmonized and scientifically robust approach to photosafety evaluation by providing a comprehensive overview of current trends and challenges and by establishing a curated database of reference substances with a comparative analysis of validated in vitro methods against in vivo outcomes. Through the development of the PhotoChem Reference Chemical Database, we compiled detailed information on 251 substances, including phototoxic, non-phototoxic, and photosensitization classifications. Our database includes cosmetics [159], pharmaceuticals [48], and industrial and agricultural chemicals [54] for which photosafety assessment is required. It also integrates CAS numbers, physicochemical data, UV absorbance characteristics, and test results from the literature and drug approval dossiers across four major regulatory regions: the United States, Europe, Japan, and South Korea.

An evaluation of three key OECD in vitro test methods, namely TG 432, TG 495, and TG 498, revealed that all three in vitro test methods demonstrated high sensitivity and accuracy when compared to human and animal classifications. These results suggest strong potential for these methods to serve as alternatives to traditional animal-based testing. However, the notably lower specificity observed in TG 432 and TG 495 (54.3% and 63.6%, respectively) compared to TG 498 highlights an important limitation of current cell-based models. These methods are designed to maximize sensitivity to minimize false negatives, but this often leads to an increased incidence of false positives, reducing overall specificity. In contrast, TG 498, which employs reconstructed human epidermis models, demonstrated superior performance in both sensitivity and specificity despite having fewer data points. This suggests that 3D reconstructed human skin-based models may better mimic in vivo conditions, and their use in photosafety testing is likely to expand in future regulatory frameworks. The observed differences in specificity underscore the need for continued refinement and novel photosafety testing methods suited to particular regulatory contexts.

To further address these limitations and enhance the precision of in vitro models, quantitative structure–activity relationship (QSAR) models and artificial intelligence (AI)-based prediction systems may offer promising complementary approaches. QSAR models can prescreen compounds based on structural alerts and physicochemical properties, while AI models trained on multi source data including UV spectrum, historical assay results, and chemical fingerprints can provide integrated, quantitative predictions of phototoxic potential. Importantly, the PhotoChem DB developed in this study provides a robust foundation for building and validating such predictive models, suggesting that our study may contribute to the evolution of more accurate and human relevant non-animal assessment strategies.

An analysis of 106 pharmaceutical approvals from the FDA, PMDA, EMA, and MFDS revealed an increasing emphasis on phototoxicity evaluation across jurisdictions. A notable increase in test submissions to the MFDS was observed following the 2021 revision of its regulatory guidelines. Moreover, the distribution of test method preferences varied by country, with the 3T3 NRU and ROS assays commonly used for phototoxicity evaluation, while photo-LLNA and guinea pig assays were frequently applied for photosensitization.

Together, the curated database and comparative method analysis reinforce the importance of developing scientifically validated and internationally aligned nonanimal testing strategies. These findings also demonstrate the value of integrating physicochemical and UV-reactive properties to enhance predictive toxicology and support regulatory decision making.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we assessed the phototoxic potential of a range of chemical compounds using the 3T3 Neutral Red Uptake Phototoxicity Test (3T3 NRU PT), along with other validated in vitro methods. Several test substances exhibited significant responses upon UVA exposure, underscoring the importance of early stage photosafety screening, particularly for substances likely to be simultaneously exposed to skin and light. The 3T3 NRU PT method proved to be a reliable and reproducible tool for identifying phototoxicity, supporting its continued use in safety assessments. When benchmarked against human and animal data, TG 495 and TG 498 also showed excellent predictive performance, further validating the role of in vitro alternatives in regulatory applications. Furthermore, the PhotoChem Reference Chemical Database developed in this study serves as a valuable platform for advancing research, regulatory alignment, and method innovation. By combining chemical characteristics, UV absorption profiles, and cross-platform results, the database enables an integrated and data-driven analysis of photoreactivity risk.

Future research should aim to improve the precision of in vitro models, deepen mechanistic understanding, and adopt computational tools such as quantitative structure activity relationship (QSAR) models and artificial intelligence-based prediction systems. These approaches will facilitate scientifically rigorous and ethically responsible photosafety evaluation while reducing reliance on animal testing. In addition, the PhotoChem DB is expected to evolve as a dynamic, expandable resource by incorporating newly identified reference compounds, mechanistic data, and test results. Its continued development will also support the creation and validation of QSAR and AI-driven models, contributing to more precise, efficient, and human relevant safety assessments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.-Y.L., S.B. and K.-M.L.; methodology, G.-Y.L., J.-H.H. (Jee-Hyun Hwang), J.-H.H. (Jeong-Hyun Hong), S.B. and K.-M.L.; formal analysis, G.-Y.L., J.-H.H. (Jee-Hyun Hwang) and J.-H.H. (Jeong-Hyun Hong); investigation, G.-Y.L., J.-H.H. (Jee-Hyun Hwang) and J.-H.H. (Jeong-Hyun Hong); resources, K.-M.L.; data curation, G.-Y.L., J.-H.H. (Jee-Hyun Hwang), J.-H.H. (Jeong-Hyun Hong) and K.-M.L.; writing—original draft preparation, G.-Y.L.; writing—review and editing, S.B. and K.-M.L.; supervision, K.-M.L.; project administration, K.-M.L.; funding acquisition, S.B. and K.-M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by grants (RS-2024-00396737 and 24212MFDS250) from the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety Korea.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with a minor correction to the Funding statement. This change does not affect the scientific content of the article.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| OECD | The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| ICH | International Council for Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use |

| FDA | U.S. Food and Drug Administration |

| PMDA | Japan Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency |

| EMA | European Medicines Agency |

References

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. S10 Photosafety Evaluation of Pharmaceuticals Guidance for Industry; ICH Guideline, ed.; Center for Drug Evaluation and Research: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, J.H. Phototoxicity and Photoallergy. Semin. Cutan. Med. Surg. 1999, 18, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linda, J.; Loretz, J.E.B. CTFA Safety Evaluation Guidelines; The Cosmetic, Toiletry, and Fragrance Association: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Test No. 432: In Vitro 3T3 NRU Phototoxicity Test; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Test No. 495: Ros (Reactive Oxygen Species) Assay for Photoreactivity; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Test No. 498: In Vitro Phototoxicity-Reconstructed Human Epidermis Phototoxicity Test Method; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.Y.; Seo, S.; Choi, K.H.; Yun, J. Evaluation of phototoxicity of tattoo pigments using the 3 T3 neutral red uptake phototoxicity test and a 3D human reconstructed skin model. Toxicol. Vitr. 2020, 65, 104813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelièvre, D.; Justine, P.; Christiaens, F.; Bonaventure, N.; Coutet, J.; Marrot, L.; Cotovio, J. The EpiSkin phototoxicity assay (EPA): Development of an in vitro tiered strategy using 17 reference chemicals to predict phototoxic potency. Toxicol. Vitr. 2007, 21, 977–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onoue, S.; Igarashi, N.; Yamada, S.; Tsuda, Y. High-throughput reactive oxygen species (ROS) assay: An enabling technology for screening the phototoxic potential of pharmaceutical substances. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2008, 46, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, S.; Ju, J.H.; Son, K.H.; Lee, J.P.; Kim, J.; Lim, C.H.; Hong, S.K.; Kwon, T.R.; Chang, M.; Kim, D.S.; et al. Alternative methods for phototoxicity test using reconstructed human skin model. Altex 2009, 26, 136. [Google Scholar]

- Spielmann, H.; Balls, M.; Brand, M.; Döring, B.; Holzhütter, H.; Kalweit, S.; Klecak, G.; Eplattenier, H.; Liebsch, M.; Lovell, W.; et al. EEC/COLIPA project on in vitro phototoxicity testing: First results obtained with a Balb/c 3T3 cell phototoxicity assay. Toxicol. Vitr. 1994, 8, 793–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spielmann, H.; Balls, M.; Dupuis, J.; Pape, W.J.; de Silva, O.; Holzhütter, H.G.; Gerberick, F.; Liebsch, M.; Lovell, W.W.; Pfannenbecker, U. A study on UV filter chemicals from Annex VII of European Union Directive 76/768/EEC, in the in vitro 3T3 NRU phototoxicity test. Altern. Lab. Anim. 1998, 26, 679–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liebsch, M. Prevalidation of the “EpiDerm™ Phototoxicity Test”—FINAL REPORT(Phase I, II, III); ZEBET, German National Centre for Documentation and Evaluation of Alternatives to Animal Experiments: Berlin, Germany, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- ROS Assay Validation Management Team. Validation Report for the International Validation Study on ROS (Reactive Oxygen Species) Assay as a Test Evaluating Phototoxic Potential of Chemicals (Atlas Suntest Version). 2013. Available online: https://www.jacvam.go.jp/files/news/ROS_Assay_full%2020130920%20atlas_fourth%20data.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Kandarova, H.; Liebsch, M. The EpiDerm™ Phototoxicity Test (EpiDerm™ H3D-PT). In Alternatives for Dermal Toxicity Testing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 483–503. [Google Scholar]

- Liebsch, M.; Barrabas, C.; Traue, D.; Spielmann, H. Development of a new in vitro test for dermal phototoxicity using a model of reconstituted human epidermis. Altex 1997, 14, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumanna, N.; Holzleb, E.; Plewigc, G.; Schwarzd, T.; Panizzone, R.; Breitf, R.; Ruzickaa, T.; Lehmanna, P. Photopatch testing: The 12-year experience of the German, Austrian, and Swiss photopatch test group. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2000, 42, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.A.; Lovell, W.W.; King, A.V.; Earl, L.K. In vitro testing for phototoxic potential using the EpiDerm 3-D reconstructed human skin model. Toxicol. Methods 2001, 11, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spielmann, H.; Lovell, W.W.; Hölzle, E.; Johnson, B.E.; Maurer, T.; Miranda, M.A.; Pape, W.J.W.; Sapora, O.; Sladowski, D. In vitro phototoxicity testing: The report and recommendations of ECVAM workshop 2. Altern. Lab. Anim. 1994, 22, 314–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spielmann, H.; Balls, M.; Dupuis, J.; Pape, W.; Pechovitch, G.; de Silva, O.; Holzhütter, H.-G.; Clothier, R.; Desolle, P.; Gerberick, F.; et al. The international EU/COLIPA in vitro phototoxicity validation study: Results of phase II (blind trial). Part 1: The 3T3 NRU phototoxicity test. Toxicol. Vitr. 1998, 12, 305–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernard, F.-X.; Barrault, C.; Deguercy, A.; De Wever, B.; Rosdy, M. Development of a highly sensitive in vitro phototoxicity assay using the SkinEthicTM reconstructed human epidermis. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2000, 16, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillot, J.-P.; Gonnet, J.-F.; Loquerie, J.-F.; Martini, M.-C.; Convert, P.; Cotte, J. A new method for the assessment of phototoxic and photoallergic potentials by topical applications in the albino guinea pig. J. Toxicol. Cutan. Ocul. Toxicol. 1985, 4, 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, J.; Elsaesser, C.; Picarles, V.; Grenet, O.; Kolopp, M.; Chibout, S.-D.; Fraissinette, A.d.B.d. Assessment of the phototoxic potential of compounds and finished topical products using a human reconstructed epidermis. Vitr. Mol. Toxicol. J. Basic Appl. Res. 2001, 14, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillaha, C.J.; Jansen, G.T.; Honeycutt, W.M.; Bradford, A.C. Selective cytotoxic effect of topical 5-fluorouracil. Arch. Dermatol. 1963, 88, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reus, A.A.; Usta, M.; Kenny, J.D.; Clements, P.J.; Pruimboom-Brees, I.; Aylott, M.; Lynch, A.M.; Krul, C.A. The in vivo rat skin photomicronucleus assay: Phototoxicity and photogenotoxicity evaluation of six fluoroquinolones. Mutagenesis 2012, 27, 721–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevisi, P.; Vincenzi, C.; Chieregato, C.; Guerra, L.; Tosti, A. Sunscreen sensitization: A three-year study. Dermatology 1994, 189, 55–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroon, S. Standard photopatch testing with Waxtar®, para-aminobenzoic acid, potassium dichromate and balsam of Peru. Contact Dermat. 1983, 9, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, L.R.; Tharmann, J.; Campos, P.M.M.; Liebsch, M. Skin phototoxicity of cosmetic formulations containing photounstable and photostable UV-filters and vitamin A palmitate. Toxicol. Vitr. 2013, 27, 418–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, B.; Holzhütter, H.-G. Holzhütter, In vitro phototoxicity testing: Development and validation of a new concentration response analysis software and biostatistical analyses related to the use of various prediction models. Altern. Lab. Anim. 2002, 30, 415–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liebsch, M. Prevalidation of the EpiDerm phototoxicity test. In Alternatives to Animal Testing II: Proceedings of the Second International Scientific Conference; European Cosmetic Industry: Brussels, Belgium, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kaidbey, K.H.; Kligman, A.M. Identification of topical photosensitizing agents in humans. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1978, 70, 149–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandarova, H.; Raabe, H.; Hilberer, A.; Choksi, N.; Allen, D. Retrospective Review on In Vitro Phototoxicity Data Generated in 3D Skin Models to Support the Development of New OECD Test Guideline. Poster Presented at: Society of Toxicology USA (SOT), 2021 Virtual Annual Meeting, March. 2021. Available online: https://www.mattek.com/reference-library/retrospective-review-on-in-vitro-phototoxicity-data-generated-in-3d-skin-models-to-support-the-development-of-new-oecd-test-guideline/ (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Kejlová, K.; Jírová, D.; Bendová, H.; Gajdoš, P.; Kolářová, H. Phototoxicity of essential oils intended for cosmetic use. Toxicol. Vitr. 2010, 24, 2084–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.; King, A.; Earl, L.; Lawrence, R. An assessment of the phototoxic hazard of a personal product ingredient using in vitro assays. Toxicol. Vitr. 2003, 17, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onoue, S.; Ochi, M.; Gandy, G.; Seto, Y.; Igarashi, N.; Yamauchi, Y.; Yamada, S. High-throughput screening system for identifying phototoxic potential of drug candidates based on derivatives of reactive oxygen metabolites. Pharm. Res. 2010, 27, 1610–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, T.; Honda, S.; Nakauchi, Y.; Ito, H.; Kinoshitu, M. Photocontact dermatitis due to bithionol, TBS, diaphene and hexachlorophene. Jpn. J. Dermatol. (Ser. B) 1971, 81, 238–244. [Google Scholar]

- Ritacco, G.; Hilberer, A.; Lavelle, M.; Api, A.M. Use of alternative test methods in a tiered testing approach to address photoirritation potential of fragrance materials. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2022, 129, 105098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Review, C.I. Safety Assessment of Citrus-Derived Peel Oils as Used in Cosmetics. 2014. Available online: https://www.cir-safety.org/sites/default/files/cpeelo062014tent.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Líšková, A.; Letašiová, S.; Jantová, S.; Brezová, V.; Kandarova, H. Evaluation of phototoxic and cytotoxic potential of TiO2 nanosheets in a 3D reconstructed human skin model. ALTEX-Altern. Anim. Exp. 2020, 37, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jírová, D.; Kejlová, K.; Bendová, H.; Ditrichová, D.; Mezulániková, M. Phototoxicity of bituminous tars—Correspondence between results of 3T3 NRU PT, 3D skin model and experimental human data. Toxicol. Vitr. 2005, 19, 931–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kejlová, K.; Jírová, D.; Bendová, H.; Kandárová, H.; Weidenhoffer, Z.; Kolářová, H.; Liebsch, M. Phototoxicity of bergamot oil assessed by in vitro techniques in combination with human patch tests. Toxicol. Vitr. 2007, 21, 1298–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.A.; King, A.V.; Lovell, W.W.; Earl, L.K. Phototoxicity testing using 3-D reconstructed human skin models. In Alternatives to Animal Testing II: Proceedings of the Second International Scientific Conference; European Cosmetic Industry: Brussels, Belgium; CPL Press: Newbury, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kandarova, H. Evaluation and Validation of Reconstructed Human Skin Models as Alternatives to Animal Tests in Regulatory Toxicology. 2006. Available online: https://refubium.fu-berlin.de/bitstream/handle/fub188/5740/00_kandarova01.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Schauder, S.; Ippen, H. Contact and photocontact sensitivity to sunscreens: Review of a 15-year experience and of the literature. Contact Dermat. 1997, 37, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messer, A.; Raquet, N.; Lohr, C.; Schrenk, D. Major furocoumarins in grapefruit juice II: Phototoxicity, photogenotoxicity, and inhibitory potency vs. cytochrome P450 3A4 activity. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2012, 50, 756–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkup, M.; Narayan, S.; Kennedy, C. Cutaneous recall reactions with systemic fluorouracil. Dermatology 2003, 206, 175–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinman, M.H.; Smith, M.D.; Kurali, E.; Kleinpeter, S.; Jiang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Kennedy-Gabb, S.A.; Lynch, A.M.; Geddes, C.D. An evaluation of chemical photoreactivity and the relationship to phototoxicity. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2010, 58, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybilla, B.; Ring, J.; Schwab, U.; Galosi, A.; Dorn, M.; Braun-Falco, O. Photosensitizing properties of nonsteroidal antirheumatic drugs in the photopatch test. Hautarzt Z. Dermatol. Venerol. Verwandte Geb. 1987, 38, 18–25. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, C.L.; Campbell, T.A.; Puertolas, L.F.; Kaidbey, K.H. Photoreaction potential of orally administered levofloxacin in healthy subjects. Ann. Pharmacother. 2000, 34, 453–458. [Google Scholar]

- Seto, Y.; Inoue, R.; Ochi, M.; Gandy, G.; Yamada, S.; Onoue, S. Combined use of in vitro phototoxic assessments and cassette dosing pharmacokinetic study for phototoxicity characterization of fluoroquinolones. AAPS J. 2011, 13, 482–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagai, N.; Yoshida, M.; Takayama, S. Phototoxic potential of the new quinolone antibacterial agent levofloxacin in mice. Arzneimittelforschung 1992, 43, 404–405. [Google Scholar]

- Dam, C.; Bygum, A. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus induced or exacerbated by proton pump inhibitors. Acta Derm.-Venereol. 2008, 88, 87–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljunggren, B.; Sjövall, P. Systemic quinine photosensitivity. Arch. Dermatol. 1986, 122, 909–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seto, Y.; Ohtake, H.; Sato, H.; Onoue, S. Phototoxic risk assessment of dermally-applied chemicals with structural variety based on photoreactivity and skin deposition. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2020, 113, 104619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilaç, C.; Şahin, M.T.; Ermertcan, A.T.; Ermertcan, A.T. The Interaction of Topically Applied 2% Erythromycin, 4% Erythromycin and Tetracycline with Narrow Band UVB. J. Turk. Acad. Dermatol. 2008, 2, jtad82101a. [Google Scholar]

- Kandarova, H.; Liskova, A.; Milasova, T.; Letasiova, S. Inter-and intra-laboratory reproducibility of the in vitro photo-toxicity test using 3D reconstructed human epidermis model. Toxicol. Lett. 2018, 295, S130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Review Report: TABRECTA Tablets 150 mg and 200 mg. 2020. Available online: https://www.pmda.go.jp/drugs/2020/P20200624005/300242000_30200AMX00494_A100_1.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 214018. 2021. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2021/214018Orig1s000IntegratedR.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 217424. 2024. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2024/217424Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 209353. 2018. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2018/209353Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Treatment of SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Hospitalized Patients with Moderate to Severe COVID-19 Infection Who Are at High Risk for Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS). 2022. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/162980/download (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 217417. 2023. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2023/217417Orig1s000IntegratedR.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 211964. 2021. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2021/211964Orig1s000IntegratedR.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 22-038. 2007. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2007/022038s000_PHARMR.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 202211. 2013. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2013/202211Orig1s000Pharm.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 212099. 2019. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2019/212099Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- European Medicines Agency. CHMP Assessment Report: Nubeqa. 2020. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/nubeqa-epar-public-assessment-report_en.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Review Report: ORLADEYO Capsules 150 mg. 2020. Available online: https://www.pmda.go.jp/drugs/2020/P20201124005/252211000_30300AMX00031_A100_1.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Background Information on LOQOA Tapes. 2015. Available online: https://www.pmda.go.jp/drugs/2015/P20150930001/400059000_22700AMX01021_B100_1.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Background Information on NAILIN Capsules 100 mg. 2018. Available online: https://www.pmda.go.jp/drugs/2018/P20180117001/300089000_23000AMX00012000_B100_1.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 216993. 2023. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2023/216993Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 212725. 2019. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2019/212725Orig1s000,%20212726Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- European Medicines Agency. CHMP Assessment Report: Jyseleca. 2020. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/jyseleca-epar-public-assessment-report_en.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- European Medicines Agency. CHMP Assessment Report: Adempas. 2014. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/adempas-epar-public-assessment-report_en.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- European Medicines Agency. CHMP Assessment Report: Tafinlar. 2013. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/tafinlar-epar-public-assessment-report_en.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- European Medicines Agency. CHMP Assessment Report: Braftovi. 2018. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/braftovi-epar-public-assessment-report_en.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- European Medicines Agency. CHMP Assessment Report: Mekinist. 2014. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/mekinist-epar-public-assessment-report_en.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Background Information on Mekinist Tablets 0.5 mg and 2 mg. 2018. Available online: https://www.pmda.go.jp/drugs/2018/P20180320003/300242000_22800AMX00374000_B100_1.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 204569 Pharmacology Review. 2014. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2014/204569Orig1s000PharmR.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- European Medicines Agency. CHMP Assessment Report: Lyfnua. 2023. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/lyfnua-epar-public-assessment-report_en.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Review Report: BIKTARVY Combination Tablets. 2019. Available online: https://www.pmda.go.jp/drugs/2019/P20190423002/230867000_23100AMX00302_A100_1.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Review Report: SUNLENCA Subcutaneous Injection 463.5 mg and Tablets 300 mg. 2023. Available online: https://www.pmda.go.jp/drugs/2023/P20230822001/230867000_30500AMX00183_A100_1.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 210806. 2018. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2018/210806Orig1s000,%20210807Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 22-291. 2008. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2008/022291s000_PharmR_P3.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Review Report: Visono Tape, Toa Eiyo Co., Ltd. 2019. Available online: https://www.pmda.go.jp/drugs/2019/P20190118001/480008000_22500AMX00993_A100_1.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- European Medicines Agency. CHMP Assessment Report: Mektovi. 2018. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/mektovi-epar-public-assessment-report_en.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Review Report: Adempas Tablets 0.5 mg, 1.0 mg, and 2.5 mg. 2013. Available online: https://www.pmda.go.jp/drugs/2013/P201300173/630004000_22600AMX00013000_A100_2.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 205834. 2014. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2014/205834Orig1s000PharmR.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 204790. 2013. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2013/204790Orig1s000PharmR.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 217347. 2024. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2024/217347Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Review Report: CRESEMBA Capsules 100 mg and Intravenous Infusion 200 mg. 2023. Available online: https://www.pmda.go.jp/drugs/2023/P20230118002/100898000_30400AMX00448_A100_1.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Review Report: Rebetol Capsules 200 mg. 2019. Available online: https://www.pmda.go.jp/drugs/2019/P20190116001/170050000_21300AMY00493_A100_1.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Review Report: Arokaris I.V. Infusion 235 mg. 2022. Available online: https://www.pmda.go.jp/drugs/2022/P20220325004/400107000_30400AMX00182_A100_2.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Review Report: EVRYSDI Dry Syrup 60 mg. 2021. Available online: https://www.pmda.go.jp/drugs/2021/P20210621001/450045000_30300AMX00294_A100_1.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Review Report: ONGENTYS Tablets 25 mg. 2020. Available online: https://www.pmda.go.jp/drugs/2020/P20200619001/180188000_30200AMX00487_A100_1.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Review Report: Moizerto Ointment 0.3% and 1%. 2021. Available online: https://www.pmda.go.jp/drugs/2021/P20211001002/180078000_30300AMX00436_A100_1.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Review Report: Rapalimus Gel 0.2%. 2018. Available online: https://www.pmda.go.jp/drugs/2018/P20180402001/620095000_23000AMX00464_A100_1.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Review Report: Omjjara Tablets 100 mg, 150 mg, and 200 mg. 2024. Available online: https://www.pmda.go.jp/drugs/2024/P20240705002/340278000_30600AMX00155_A100_1.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- European Medicines Agency. CHMP Assessment Report: Mayzent. 2019. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/mayzent-epar-public-assessment-report_en.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 215358. 2021. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2021/215358Orig1s000,Orig2s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Review Report: SCEMBLIX Tablets 20 mg, 40 mg. 2022. Available online: https://www.pmda.go.jp/drugs/2022/P20220330001/300242000_30400AMX00189_A100_1.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Review Report: Riamet Combination Tablets. 2016. Available online: https://www.pmda.go.jp/drugs/2016/P20161222001/300242000_22800AMX00727_A100_1.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 212887. 2021. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2021/212887Orig1s000,212888Orig1s000IntegratedR.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 207924. 2018. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2018/207924Orig1s000PharmR.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Review Report: ADLUMIZ Tablets 50 mg. 2021. Available online: https://www.pmda.go.jp/drugs/2021/P20210113006/180188000_30300AMX00003_A100_1.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Review Report: CORECTIM Ointment 0.5%. 2019. Available online: https://www.pmda.go.jp/drugs/2019/P20191209001/530614000_30200AMX00046_A100_1.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Review Report: Sirturo Tablets 100 mg. 2017. Available online: https://www.pmda.go.jp/drugs/2017/P20171228001/800155000_23000AMX00020_A100_1.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Review Report: Ofev Capsules 100 mg and 150 mg. 2015. Available online: https://www.pmda.go.jp/drugs/2015/P20150619001/530353000_22700AMX00693000_A100_1.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Review Report: Votrient Tablets 200 mg. 2012. Available online: https://www.pmda.go.jp/drugs/2012/P201200143/34027800_22400AMX01405_A100_2.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Review Report: Evrenzo Tablets 20 mg, 50 mg, and 100 mg. 2019. Available online: https://www.pmda.go.jp/drugs/2019/P20191007001/800126000_30100AMX00239_A100_1.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Review Report: Uptravi Tablets 0.2 mg and 0.4 mg. 2016. Available online: https://www.pmda.go.jp/drugs/2016/P20161011001/530263000_22800AMX00702_A100_1.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Review Report: FASLODEX Intramuscular Injection 250 mg. 2024. Available online: https://www.pmda.go.jp/drugs/2024/P20240618001/670227000_22300AMX01209_A100_1.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Review Report: Gonax Subcutaneous Injection 80 mg and 120 mg. 2012. Available online: https://www.pmda.go.jp/drugs/2012/P201200093/80012600_22400AMX00729000_A100_1.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Review Report: ANEREM 50 mg for I.V. Injection. 2020. Available online: https://www.pmda.go.jp/drugs/2020/P20200120002/770098000_30200AMX00031_A100_1.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Review Report: Koselugo Capsules 10 mg and 25 mg. 2022. Available online: https://www.pmda.go.jp/drugs/2022/P20220926004/870056000_30400AMX00430000_A100_1.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Review Report: Jeselhy Tablets 40 mg. 2022. Available online: https://www.pmda.go.jp/drugs/2022/P20220706001/400107000_30400AMX00211_A100_1.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Review Report: Beleximpo Tablets 80 mg. 2020. Available online: https://www.pmda.go.jp/drugs/2020/P20200407003/180188000_30200AMX00437_A100_1.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- European Medicines Agency. CHMP Assessment Report: Zelboraf. 2012. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/zelboraf-epar-public-assessment-report_en.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Review Report: Zelboraf Tablets 240 mg. 2014. Available online: https://www.pmda.go.jp/drugs/2014/P201400179/450045000_22600AMX01406_A100_1.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Review Report: Zavicefta Combination for Intravenous Infusion. 2024. Available online: https://www.pmda.go.jp/drugs/2024/P20240618004/672212000_30600AMX00154_A100_1.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Review Report: Sprycel Tablets 20 mg and 50 mg. 2009. Available online: https://www.pmda.go.jp/drugs/2009/P200900013/670605000_22100AMX00395_A100_1.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Review Report: JOYCLU 30 mg Intra-Articular Injection. 2021. Available online: https://www.pmda.go.jp/drugs/2021/P20210303001/380003000_30300AMX00234_A100_1.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 21-436. 2002. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2002/21-436_Abilify_pharmr_P1.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 20-749. 1997. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/97/20749_LAMISIL%20SOLUTION,%201%25_PHARMR.PDF (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 22-029. 2008. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2008/022029s000pharmr.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 202736. 2012. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2012/202736Orig1s000PharmR.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 20-941. 2000. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2000/020941s000_PharmR.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 21-307. 2001. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2001/21-307_Lotrimin_pharmr.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 22-122. 2007. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2007/022122_PharmR_P2.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 21-501. 2006. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2006/021501s000_PharmR.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 211527. 2019. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2019/211527Orig1s000MultidisclipineR.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 216632. 2024. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2024/216632Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 213189. 2020. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2020/213189Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 20-600. 1997. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/97/20600_TAZORAC%200.05%25%20AND%200.1%25_PHARMR_P1.PDF (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 215272. 2022. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2022/215272Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 19-931. 1996. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/96/019931ap.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 22-408. 2011. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2011/022408Orig1s000PharmR.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 215309. 2022. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2022/215309Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 215985. 2022. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2022/215985Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 21-302. 2001. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2001/21-302_ELIDEL_pharmr_P7.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 20-629. 1996. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/pre96/020629Orig1s000rev.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 208945 Pharmacology Review. 2017. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2017/208945Orig1s000PharmR.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 208552. 2017. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2017/208552Orig1s000PharmR.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 20-886. 1999. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/99/20886_phrmr_P2.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Report on the Deliberation ResultsAlabel Oral 1.5 g, Alaglio Oral 1.5 g. 2013. Available online: https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000153482.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 21-055. 1999. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/99/21055_Targretin_pharmr_P2.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 215064. 2024. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2024/215064Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 204708. 2013. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2013/204708Orig1s000PharmR.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 22-395. 2009. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2009/022395s000Pharmr.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 21-159. 2003. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2003/21159_Loprox_pharmr.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 213433. 2020. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2020/213433Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 21-794. 2005. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2005/021794s000_PharmR.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 205175. 2013. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2013/205175Orig1s000PharmR.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 203567. 2014. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2014/203567Orig1s000PharmR.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 20-985. 2000. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2000/20-985_Carac_Pharmr_P1.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 210361. 2018. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2018/210361Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 206255. 2014. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2014/206255Orig1s000PharmR.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. NDA 204153. 2013. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2013/204153Orig1s000PharmR.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Marcin, S.; Aleksander, A. Acute toxicity assessment of nine organic UV filters using a set of biotests. Toxicol. Res. 2023, 39, 649–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).