Abstract

Peru is currently distinguished by its remarkable biodiversity, which is characterized by a high level of endemism and a wide array of ecological niches. In the context of biodiversity, the genus Theobroma spp. is particularly noteworthy, encompassing the species Theobroma cacao, Theobroma grandiflorum and Theobroma bicolor, which are collectively referred to as cacao, cupuaçu, and macambo, respectively. The primary economic value of these species is derived from their mucilage-rich pulp and beans. In recent years, the mucilage of the genus Theobroma has gained economic relevance due to its flavor, floral and fruity aroma. The present review article aims to provide a comprehensive exploration of Theobroma spp. mucilage, addressing its characterization and potential applications. The present study investigates aspects related to its origin, cob morphology, proximal composition, bioactive compounds, volatile profile and its application in the food industry. The study highlights a high content of polysaccharides such as reducing sugars, organic acids, pectin, cellulose, hemicellulose, antioxidant capacity, presence of polyphenols and methylxanthines. Through this comprehensive review, a prospective vision is proposed on the opportunities for innovation and sustainable development around the Theobroma mucilage industry, highlighting its relevance not only as a agri-food byproduct, but also as a valuable resource in the productive circular economy and the sustainability of biodiversity.

1. Introduction

The Peruvian Amazon region has a lot of different plants and animals. One important group is the Malvaceae family, which includes 243 types and 4300 species [1]. This endemic family contains the genus Theobroma spp., which is characterized by its multiple applicability of grains in the agro-industrial and pharmaceutical sectors [2]. The genus Theobroma comprises 20 species, nine of which are found in the Amazonian region. The most notable species are T. cacao, T. grandiflorum and T. bicolor [3]. Although the trees have similar morphologies; their flowers and fruits differ in shape and colour [4]. The pods of the T. cacao tree can vary from having prominent grooves to being almost smooth, and display colors such as bright green, dark green, yellow or dark red, or a combination of these colors [5]. Conversely, the fruits of T. grandiflorum range in colour from light brown to dark brown, and can be oblong or ellipsoidal, and its seeds are covered by a semi-liquid mucilage that is ivory-colored [6,7]. The fruit of T. bicolor is ribbed, grooved and veined; its seeds are covered with creamy, yellowish mucilage [8].

Theobroma seeds are a significant source of polyphenolic compounds and methylxanthines [9]. Despite their phylogenetic proximity, flavonoid compounds unique to T. cacao, such as theograndins, are detected in T. grandiflorum [10,11]. Several studies have demonstrated the high antioxidant capacity of the exuded fermentation residues and the presence of compounds such as catechin, epicatechin and procyanidin [8,12,13]. The mucilages of the genus Theobroma are a source of nutrients and photochemical bioactives, including phenolic compounds. They are a promising source of alternative food ingredients for use in various sectors of the food, pharmaceutical and other industries.

The present review article aims to demonstrate the composition, functional properties and potential applications of mucilage from three species of Theobroma in order to stimulate interest among researchers in their reintroduction to the food industry using a circular economy approach.

2. Methodology

The present review has been proposed from an overview of Theobroma spp. Specifically, this review presents information on T. cacao, T. grandiflorum and T. bicolor mucilage, collected from scientific literature in the Scopus, ScienceDirect, SpringerLink and Web of Science databases. A comprehensive search was conducted using a range of keywords, including ‘mucilage’, ‘pulp’, ‘exudate’, ‘cocoa honey’, ‘bioactive compounds’, ‘volatile compounds ‘and ‘industrial applications’, all including ‘Theobroma spp.’ term.

Using the keyword ‘Theobroma spp.’, the search range was set to between 2000 and 2025, showing approximately 1150 results. The search was then refined using specific keywords, reducing the number of results to around 130 works. Around 60% of the articles reviewed were included in this review.

The data were systematically organized for the purpose of writing the present article, with a particular emphasis on current evidence and studies that were supported by scientific methodology.

2.1. Geographical Distribution of Theobroma spp.

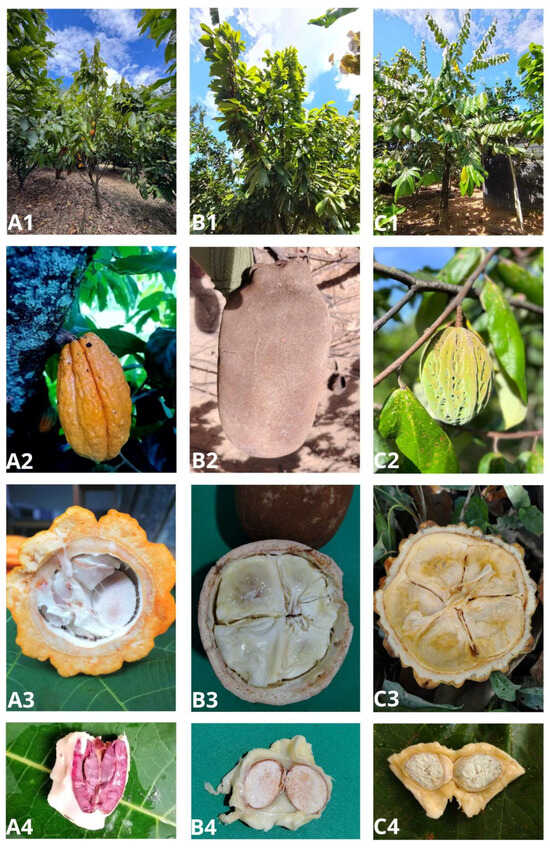

Theobroma spp. species are geographically distributed across various tropical regions of the world. They are a vital agricultural resource for communities in Latin America and other tropical regions of Asia and Africa. Figure 1 presents the main species of the genus Theobroma, specifically T. cacao, T. grandiflorum, and T. bicolor, and includes representative views of the tree, the cob, internal components of the cob, as well as the mucilage covered grains.

In T. cacao, studies indicate that the greatest genetic diversity is found in the humid forests of the Amazon region [14,15]. Within cacao species, two important groups have been identified: the Criollo and Forastero. The classification of these groups is based on distinct morphological characteristics, including the size and thickness of the cob, the mucilage/grain ratio, and other characteristics. However, the process followed by the chocolate industry is analogous, start with the harvesting of the pods, followed by partial separation of the mucilage from grains and, consequently fermentation. The process ends with the drying and roasting of the grains [16].

Figure 1.

Main species of the genus Theobroma spp. (A) T. cacao, (B) T. grandiflorum and (C) T. bicolor. Photographic views from the tree (A1,B1,C1), cob (A2,B2,C2), cross-section of cob (A3,B3,C3), grains and mucilage (A4,B4,C4).

T. grandiflorum has also been documented as originating in the Amazon region [17], with a predominance of occurrence in the northern part of Brazil. This species has contributed to agriculture in Central America, South America and some Caribbean islands, especially in countries such as Peru and Brazil [18]. This Amazonian fruit has been classified as highly commercially viable due to its intense and pleasant aroma, exotic flavour and creamy texture. These sensory characteristics make it ideal for consumption fresh and for use as an ingredient in the preparation of different food products, such as ice cream, natural juices, jams, yoghurts and compotes [19,20].

T. bicolor, more commonly referred to as “macambo” or “white cocoa”, is a species that demonstrates a propensity for growth in warm, humid tropical environments. The geographical origins of this practice remain a subject of debate, with some attributing its origins to Central America, while others suggest South America as the more probable origin [1]. The production is geographically diverse, extending from Mexico to northeastern Brazil, including countries such as Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador and Peru. Clearly, T. bicolor plant has been domesticated and refined technologically for the purpose of producing seeds and mucilage. Its products are destinated for use in the food and cosmetic industries [1]. Table 1 presents general information on the production and morphology of the plants and characteristics of the mucilage.

Table 1.

Morphological characteristics of the tree and fruit of Theobroma spp.

2.2. Agro-Industrial Byproducts from the Processing of Theobroma spp.

The cob, which is the fruit of Theobroma spp. tree, is composed of an outer shell, the inside of which contains beans surrounded by a pulp known as mucilage [27], which is released mainly during the opening of the ear and fermentation. Table 2 shows the percentages of agro-industrial byproducts generated from the processing of T. cacao, T. bicolor and T. grandiflorum.

Table 2.

Percentage of co-products from various species within the genus Theobroma.

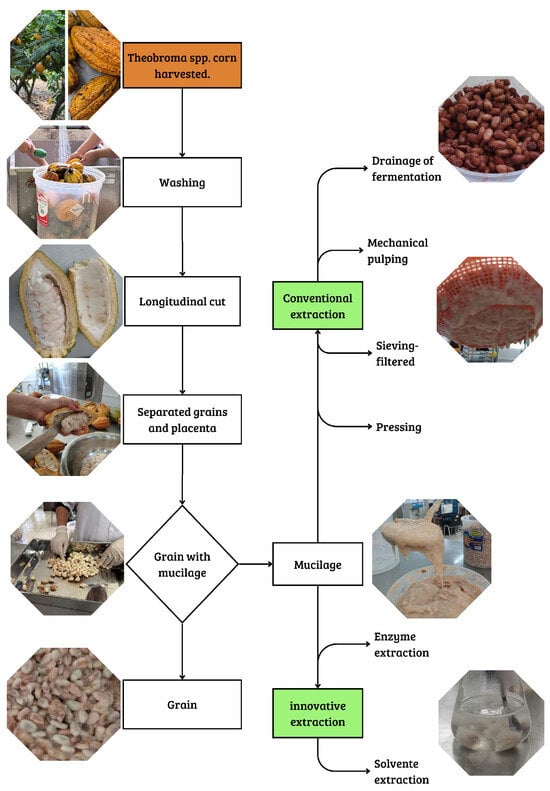

The extraction of Theobroma spp. mucilage can be carried out using traditional methods, based on physical separation as natural drainage during fermentation [12], mechanical pulping [30,31], sieving–filtering [32,33,34] and pressing [35]. However, innovative methods have been proposed, including extraction using organic solvents such as water, ethanol, and methanol, as well as pectolytic enzyme-assisted extraction through liquefaction processes, applied to the mucilage of Theobroma spp. after the pulping stage, with the aim of facilitating the breakdown of the polysaccharide matrix and improving the efficiency of exudate recovery [30,36]. Figure 2 illustrates the conditioning process of Theobroma spp. mucilage-coated grains, as well as the separation methods employed.

Figure 2.

Conventional methods and innovative strategies for the extraction of Theobroma spp. mucilage.

In general, byproducts generated during the processing of cobs are not adequately utilized, which represents a significant loss of biomass. In this context, it is essential to highlight the chemical composition, phytochemistry and volatile profile, with the aim of reintroducing it into the food industry and the sustainability of the supply chain. Despite its great potential for human consumption, Theobroma spp. mucilage is still scarcely exploited or studied.

3. Mucilage

Mucilage is a semi-liquid substance found in the family Plantaginaceae, Malvaceae Liliaceae, Linaceae, Plantaginaceae and Cactaceae, specifically in roots, bulbs, tubers, flowers and leaves [37,38]. Theobroma spp. mucilage is a complex, water-soluble polysaccharide, consisting mainly of monosaccharides and organic acids linked by glycosidic bonds, as well as glycoproteins and other compounds [39,40,41].

Recent research considers mucilage, in generic families, as a hydrocolloid containing arabinogalactan-proteins (93.2–98.2%), in which the protein fraction is linked to the carbohydrate chain [42,43].

Theobroma spp. mucilage plays a crucial role in the grain fermentation process, acting as a substrate for yeasts and bacteria (lactic and acetic). These microorganisms convert mucilage into leachates [44,45]. However, previous studies suggest partial pulping of the grains without negatively affecting the natural fermentation of the grains and their final sensory quality [46,47,48,49].

3.1. Chemical Constituents of Mucilage Theobroma spp.

Given its nature, Theobroma spp. mucilage is rich in simple sugars, polysaccharides, organic acids, phenolic and volatile compounds, making it a byproduct of great interest for the development of functional foods [12,50,51,52,53,54]. The chemical composition of the mucilage of T. cacao, T. grandiflorum and T. bicolor has been the subject of many studies. Table 3 shows the proximal macromolecular composition of the mucilage, as well as the physicochemical properties, reducing sugars and bio-compounds of the three species studied.

Table 3.

Proximal composition, physical–chemical properties, sugars, structural polysaccharides and micronutrients of Theobroma spp. mucilage.

These compositional differences have direct implications for the potential applications of Theobroma spp. mucilage. The high water content (82–93%) and soluble solids values (12–16 °Bx) are related to the carbohydrate content. In particular, T. cacao exhibits the highest °Bx content compared to the other two species [8]. Furthermore, an evaluation of the physical and chemical properties of the three species revealed that T. cacao and T. grandiflorum exhibited relatively acidic pH values (3–4). In contrast, T. bicolor exhibited a pH slightly acidic to near neutral (5–7) [8,54]. These values correlate with titratable acidity-TEA, expressed as citric acid, with contents of 60, 18, and 8 mg/g dry weight (DW), respectively, which manifests as a sweet-sour taste [8].

With regard to reducing sugar content, T cacao has the highest levels, followed by T. bicolor and T. grandiflorum. The sugar profile indicates a high concentration of sucrose in T. grandiflorum and T. bicolor. T. cacao has higher concentrations of glucose (69 mg/g) and fructose (72 mg/g), but these fermentable sugars contribute to the fermentation process carried out by S. cerevisiae, which transports and metabolizes them directly through its glycolytic pathways [58].

It has been demonstrated that T. cacao mucilage is characterized by the present of pectin as a structural polysaccharide, ranging from 0.5 to 1.2%. Research conducted by [64] involved the extraction, purification, and quantification of pectin from the mucilage of T. grandiflorum, revealing a high content of galacturonic acid. The pectin was mainly composed of highly esterified homogalacturonan, with a low degree of acetylation, as well as small regions of rhamnogalacturonan containing side chains rich in galactose and arabinose. However, increases in temperature and the activity of pectolytic enzymes, such as endopolygalacturonase, contribute to the degradation and liquefaction of these pectins during processing and fermentation [56].

Regarding the fatty acid profile of mucilage from Theobroma species, T. cacao has been reported to contain a low total lipid content (0.8–1.5%), although a detailed fatty acid profile for its mucilage has not yet been described [59]. In contrast, T. grandiflorum mucilage has been reported to be dominated by palmitic acid (55.22%), oleic acid (18.8%), and α-linolenic acid (17.9%) [60]. T. bicolor exhibits a higher proportion of saturated fatty acids, mainly stearic acid (49.6%) and palmitic acid (6.1%), whereas unsaturated fatty acids are primarily represented by oleic acid (39.9%) and linoleic acid (2.1%); the latter have been associated with protective mechanisms against fruit oxidation [65].

In this context, based on proximate quantification, physicochemical and structural characteristics, and micronutrients, the mucilage of Theobroma spp. presents a compositional profile that supports its potential incorporation into various lines of the food industry. However, the differences observed in its composition can be attributed to geographical variability, fruit maturity stage, harvest season, and intraspecific genetic variations [10].

From a food safety perspective, it is relevant to consider the potential presence of allergenic compounds in Theobroma spp. mucilage. Although this byproduct has traditionally been regarded as a safe food ingredient [66], the presence of pathogenesis-related (PR) proteins, including chitinases, osmotins, and β-1,3-glucanases, has been reported in both the mucilage and the testa tissues of cacao beans [8,67]. These enzymes play a key role in plant defense mechanisms by acting as antifungal regulators through the inhibition of spore germination and the degradation of fungal cell wall components. In particular, chitinases have been associated with cross-reactivity in latex-sensitized individuals, a phenomenon known as latex–fruit syndrome [68]. Meanwhile, osmotins and β-1,3-glucanases have demonstrated the ability to induce immunoglobulin E (IgE) synthesis, thereby triggering allergic responses in susceptible individuals [69].

3.2. Bioactive Compounds in Theobroma spp.

Bioactive compounds are phytochemical molecules naturally present in food or agro-industrial byproducts. Although they are not considered essential nutrients, they have the ability to interact with one or more constituents of living tissues, thus exerting relevant physiological effects [70]. These compounds exhibit diverse biological activities, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial and immunomodulatory properties, which explains the growing interest in the field of health and disease [71,72].

Species of the genus Theobroma spp. contain a wide variety of functional bioactive compounds with antioxidant activity, present in both the grain and mucilage, particularly in the form of flavonoids and methylxanthines and organic acids [10,60,73]. Theobroma grain is one of the main sources of these compounds; however, its use is limited by its low stability against oxidation and thermal degradation processes [9]. These compounds are primarily located in the cotyledons of the grains and can be lost during processing due to diffusion into the surrounding environment. Consequently, a significant fraction of the compound of interest can be transferred to the husk ant exudate, leading to the generation of byproducts with greater functional value rich in flavonoids and methylxanthines [11], procyanidins and proanthocyanidins [13], catechin and epicatechin extracts [74]. Table 4 provides a comprehensive overview of the compounds of interest present in mucilage, the processing parameters and the analysis method.

Table 4.

Sample preparation and analysis parameters for the quantification of bioactive compounds in Theobroma spp. mucilage.

3.2.1. Bioactive Compounds

The main bioactive compounds reported in the mucilage of Theobroma spp. have been quantified primarily using UV-Vis spectrophotometry techniques, with the Folin–Ciocalteu method being the most widely used for determining total polyphenols. Available studies show a higher total polyphenol content in T. bicolor (40–245 mg GAE/100 g), followed by T. cacao (50–105 mg GAE/100 g) and T. grandiflorum (40–66 mg GAE/100 g). The quantification of total flavonoids in the mucilage of T. cacao and T. grandiflorum has also been reported, with values ranging from 5.16 to 36.80 mg/100 mL and from 0.6 to 4 mg QE/100 g, respectively.

Quantification of bioactive compounds by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) confirmed the presence, in the mucilage of T. cacao, of flavonoids belonging to the catechin and epicatechin (0.95 mg/100 g) and proanthocyanidins B1, B2 and C1 (2.07 mg/100 mL), as well as xanthines, including theobromine in the range of 0.49 to 2.66 mg/100 mL and caffeine between 0.12 and 0.91 mg/100 mL. Several studies have reported a reduction in these alkaloids during the fermentation of the cocoa bean, which has been associated with their possible diffusion along with the exudated cellular fluids, released as a consequence of the increased permeability of the testa [51,80,81]. Furthermore, this technique has shown the presence of phenolic acids, such as gallic acid, 4-hydroxybenzoic acid and m-coumaric acid, in the mucilage of T. bicolor [54].

3.2.2. Antioxidant Capacity

The antioxidant capacity of Theobroma spp. mucilage has been evaluated using ABTS, FRAP, ORAC, and DPPH assays across the three species studied. Using the ABTS method, antioxidant activity values ranged from 4.5 to 8.5 µM TE/mL in T. cacao, from 90.6 to 96.9 µM QE/g in T. grandiflorum, and reached a value of 3.3 in T. bicolor. In contrast, FRAP-based antioxidant activity has only been reported for T. cacao, with values between 3.35 and 7.89 µM TE/mL. Regarding the ORAC assay, values of 1.28–1.33 µM TE/mL were observed in T. cacao, whereas significantly higher values (50.22–67.97) were reported for T. grandiflorum. Additionally, DPPH scavenging activity values of 4.09–4.11 µM TE/g were reported for T. grandiflorum, while a value of 1.93 mg TE/100 g was reported for T. bicolor. Importantly, several studies have demonstrated a positive correlation between total polyphenol and flavonoid contents and the antioxidant activity of cocoa mucilage [12].

In this context, Theobroma spp. mucilage, when classified according to the antioxidant effects of its bioactive compounds, exhibits a relatively high value compared to byproducts such as shell and testa, although it shows a lower antioxidant content than the cocoa bean. According to [82], who evaluated the antioxidant capacity of foods using the FRAP method, fruits and fruit juices present an average value of 0.69 mmol/100 g. Based on this criterion, Theobroma spp. mucilage can be categorized as a food with medium to high antioxidant capacity.

The compiled literature shows that botanical factors such as genetics, geographic origin, and maturity stage contribute substantially to the bioactive variability of Theobroma spp. mucilage [52]. Independently, factors such as the analytical method, processing conditions, and storage (fresh, frozen, and freeze-dried) can promote undesirable chemical and enzymatic reactions that affect the final quantification [75,83]. Furthermore, extraction parameters such as temperature, extraction time [84] and solvent polarity [78] have been shown to significantly influence both the overall extraction yield and the profile of the recovered compounds.

Although significant levels of bioactive compounds have been reported in the mucilage of Theobroma spp., there is currently no direct clinical evidence to support their benefits for human health. However, several in vitro studies have demonstrated that the intake of phytochemicals at low concentrations exhibits antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, which contribute to the prevention of cell damage, skin aging, and certain types of cancer, thus benefiting health [85]. These findings suggest that the compounds present in mucilage have high functional potential.

3.2.3. Antimicrobial Activity

Specific studies related to the antimicrobial activity of Theobroma spp. mucilage demonstrated no inhibition. However, non-traditional mucilages such as T. subincanum have shown a positive bacterial inhibitory effect against Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus mutans, with a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 37.5 mg/mL for both bacteria [54]. On the other hand, components of Theobroma spp. showed antimicrobial potential, such as the ethanolic extract of T. cacao beans against S. mutans, which presented inhibitory zones ranging from 6–15 mm, being less effective than chlorhexidine [86]. T. bicolor beans showed inhibition against the fungus C. albicans, with an MIC of 75 mg/mL. Similarly, aqueous and methyl extracts of cocoa leaves showed a positive effect against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli with inhibition zones of 12.00–26.33 mm and 14.33–26.67 mm, respectively, with a concentration range of 100 to 500 mg/mL [87]

3.3. Volatile Compounds in Theobroma spp.

Theobroma spp. is characterized by an exotic flavour, which is valued for its organoleptic properties, emphasizing the presence of floral and fruity volatile compounds [88]. As demonstrated in the studies conducted by [89,90], the volatile composition of mucilage is susceptible to influence from various factors, including genotype, cob origin and degree of maturity. Conversely, the extraction of these compounds has been achieved through the utilization of techniques such as simultaneous distillation–extraction, headspace and solid-phase extraction, followed by analysis via gas chromatography/mass spectrometry/olfactometry (GC/MS/O) [38]. As illustrated in Table 5, the results from various studies on the primary volatile components are reported.

Table 5.

Volatile compounds present in Theobroma spp. mucilage.

It has been observed that T. cacao mainly presents aromatic regions dominated by aldehyde compounds, followed by carboxylic acids, lactones, phenols, and ketones, which vary according to geographic origin, genotype, and conditioning. Studies conducted by [31] characterized cocoa from Indonesia, Vietnam, Cameroon, and Nicaragua, highlighting key odorants such as trans-4,5-epoxy-(E)-decenal, 2- and 3-methylbutanoic acid, 3-(methylthio)propanal, 2-isobutyl-3-methoxypyrazine, (E,E)-2,4-nonadienal, (E,E)-2,4-decadienal, 4-vinyl-2-methoxyphenol, δ-decalactone, 3-hydroxy-4,5-dimethylfuran-2(5H)-one, dodecanoic acid, and linalool. Complementarily, Ref. [22] identified 2-pentanal, linalool, 2-pentanone, and 2-methyl-3-buten-2-ol in Chuncho cocoa cultivars, associating these compounds with sensory descriptors such as almond, floral, fruity, and herbal. In agreement, Ref. [95] reported the presence of phenolic odorants, including 4-vinyl-2-methoxyphenol, methylphenol, and coumarin in the exudate, as well as the active contribution of linalool to aromatic complexity during the fermentation process, highlighting the possible diffusion of mucilage into the bean. Studies [31,55,91,96] have identified the presence of 2-phenylethanol in fresh mucilage, a compound widely recognized as “the flavor molecule” due to its commercial value and extensive use in the food industry. However, the presence of undesirable compounds such as indole characterized by intense floral notes accompanied by fecal nuances has also been reported. Indole can be reduced through the application of thermal treatments, thereby contributing to an improvement in the final sensory profile of the product, as well as to the formation of compounds belonging exclusively to the phenol and methylphenol groups (fruity and floral aromas) resulting from the degradation of polyphenols, lignin, enzymes, and microorganisms [55].

With regard to T. grandiflorum mucilage, the predominant major volatile components are found to be from the ester group, followed by terpenes and alcohols, such as ethyl butanoate, ethyl hexanoate, and linalool [19]. These esters have also been reported at predominant concentrations by [92,97], whereas Ref. [98] reported linalool and its oxides as an important fraction of compounds released through enzymatic hydrolysis. On the other hand, Ref. [19] compared acidic (pH 3.3) and neutral (pH 7) media, observing higher amounts of volatile compounds under acidic conditions, as well as the presence of eugenol, probably in glycosidically bound form. For T. bicolor, esters such as ethyl acetate and ethyl benzoate were also identified, along with linalool [94]. This species is characterized by a fresh, fruity aroma due to lower esters, a floral note attributed to linalool and ethyl benzoate, and a fatty note associated with fatty acids.

It is important to note that the perception of aroma is the result of complex interactions among multiple compounds; therefore, establishing a relationship with a single volatile compound often does not represent the actual sensory profile.

3.4. Mucilage Applications

In recent years, there has been an increasing awareness of the environmental impact of reinserting agri-food byproducts into the industry. The multiple applicability of this species has been demonstrated, and several authors have catalogued Theobroma spp. as a promising fruit for commercialization within the biodiversity of the Amazon region [99]. The conventional cocoa processing techniques entail a fermentation process that is intrinsic to the natural characteristics of the mucilage that envelops the cocoa bean. This process is advantageous in enhancing the sensory attributes of the final product. However, research has indicated that partial pulping of cocoa beans is advisable, as it does not hinder the fermentation process and it promotes the quality of the beans. Consequently, a substantial portion of the mucilage can be recovered and reintegrated into the value chain for various applications.

Table 6 showed the production of foods derived from T. cacao, T. grandiflorum and T. bicolor mucilage.

Table 6.

Applications of Theobroma spp. mucilage.

A significant challenge in the commercialization of T. cacao mucilage is its limited shelf life, attributable to its high moisture content and fermentable sugars, which render it a substrate of considerable biotechnological interest [107]. Research conducted [55] evaluated the preservation of mucilage through the application of pasteurization and UHT treatments. It was observed that the latter exhibited a higher incidence of nonenzymatic browning reactions, which were attributed to the elevated temperatures (135 °C) employed. Nevertheless, the UHT treatment demonstrated greater effectiveness in reducing the total mold and yeast counts (<100 CFU/g), an effect that, when considered in conjunction with the low pH of the mucilage, could be considered a limiting factor for microbial proliferation. Meanwhile, Ref. [108] appraised the impact of single and double pasteurization on total polyphenol content, antioxidant capacity, and storage stability. The study concluded that double pasteurization facilitated a reduced loss of active compounds. In addition, it was reported that storage temperatures of 4 °C and 25 °C were suitable for preserving the quality of the mucilage. On the other hand, Ref. [109] evaluated untreated mucilage syrups formulated with palm sugar, cane sugar, and refined sugar. Despite being stored at a temperature of 5 °C, these products exhibited a limited shelf life of only 5 days, indicating the necessity of thermal processing. In conclusion, the significance of implementing suitable thermal processes to guarantee microbiological stability and prolong the shelf life of mucilage derived products is emphasized by these findings.

Furthermore, T. cacao mucilage has been extensively explored as a raw material for the production of fermented beverages, including craft beer [58], kombucha [35], cocoa wine [102], non-alcoholic beverages [104] and musts [100]. However, the efficacy of these applications require strict control of ethanol production, whose yield is primarily dependent on the initial sugar content such as sucrose, glucose, and fructose, as well as on the growth rate and metabolic activity of the microorganisms involved in fermentation. Beyond its incorporation into fermented products, mucilage has been used in the formulation of jellies, ice creams, and nectars [103], where it performs both sensory and techno-functional roles by providing sweetness, aroma, and structural stability due to its pectin content. Furthermore, it has been documented that these matrices possess the capacity to retain substantial levels of flavonoids, vitamin C, and antioxidant activity, thereby augmenting their nutritional and functional value [53]. In addition, mucilage has been evaluated for its potential as a substrate in bioethanol production [101] and cellulose synthesis [57].

Regarding T. grandiflorum, applications have been reported mainly toward the development of biomaterials, particularly the formation of biofilms combined with pectin and chitosan. These biofilms exhibited satisfactory mechanical properties, such as adequate tensile strength and low permeability, partially attributed to the plasticizing effect of the sugars present, highlighting their potential application in food packaging systems [105]. Likewise, drying and microencapsulation processes using maltodextrin and inulin have been explored to obtain mucilage powders rich in ascorbic acid and phenolic compounds, with a low degree of agglomeration [106]. Additional applications include its use in the formulation of prebiotic and probiotic yogurts, in which improvements in texture and rheological properties have been observed in yogurts produced from goat milk [99]. Moreover, T. grandiflorum mucilage has been evaluated as a substrate for the cultivation of Lactobacillus rhamnosus, whose fermentation leads to lactic acid production, a compound that has demonstrated beneficial effects against endotoxemia [61] as well as in ice cream formulations.

By contrast, reports on applications of T. bicolor mucilage remain limited; however, its use in jelly formulations through the addition of stabilizing agents has been documented, suggesting an incipient technological potential that requires further research and development for industrial valorization [32].

4. Technological and Industrial Challenges

Theobroma spp. represent a significant economic value in the global market, with T. cacao being the most relevant species compared to T. grandiflorum and T. bicolor, as its dry beans are primarily used in the chocolate industry. Worldwide, cocoa production exceeded 5 million tons in 2020/2021, and its market is projected to reach USD 67 billion by 2032 [110]. The production of dry beans generates agro-industrial residues such as husk, placenta, and mucilage, which together account for approximately 85% of discarded material, with mucilage representing 3–5%. However, the growing interest in the valorization of cocoa agro-industrial by-products has positioned mucilage as a low-cost ingredient with high technological potential for the food industry, as this by-product degrades rapidly during the processing of fresh beans and is generally discarded in agricultural fields, representing an opportunity for the development of new commercially valuable products and an alternative source of income for farmers. In T. grandiflorum and T. bicolor, mucilage may have a higher economic value than the beans, although data on its market remain limited due to its recent valorization.

While the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) has classified it as a traditional ingredient suitable for human consumption [66], its development on an industrial scale remains limited by various technological and operational challenges. In particular, in the case of T. cacao, deficiencies have been reported in agricultural and manufacturing practices during the separation of the beans from the placenta, a process usually carried out in the field to facilitate transport to fermentation plants. These conditions lead to microbiological contamination of the mucilage. Furthermore, this initial handling triggers the activation of peroxidase enzymes, which compromises its stability and promotes uncontrolled biochemical reactions during fermentation, exacerbated by its high water and fermentable sugar content. In contrast, in T. grandiflorum and T. bicolor, the fruits are usually harvested and transported to the processing plant.

The greatest challenge in the industrialization of mucilage arises after its separation from the bean. This requires rapid conditioning without compromising its chemical, functional, and sensory characteristics to mitigate the risk of microbiological contamination and sensory degradation. These techniques have not yet been developed or designed on an industrial scale, as the reviewed literature has not identified the use of medium- or large-scale equipment, primarily for T. bicolor. However, T. cacao and T. grandiflorum have shown greater exploration due to their high economic value. The latter, in particular, benefits from the use of mucilage as a raw material, which is processed using small scale pulping machines and stored at low temperatures, reducing contamination and improving preservation. Consequently, the implementation of effective preservation strategies is essential. Therefore, specific research is required to develop and optimize scalable solvent extraction, stabilization and preservation processes (freezing, spray drying and freeze-drying) suitable for industrial and commercial applications, facilitating market access and supporting economic development and GDP growth in Theobroma producing regions.

The lack of technical criteria for the processing of value-added products constitutes a critical barrier to industrial scaling and the harmonization of regulatory frameworks intended to guarantee product safety, quality, and consistency.

5. Conclusions and Future Prospects

Theobroma spp. is native to Amazonian territories. The species T. cacao, T. grandiflorum and T. bicolor have demonstrated the most significant development since pre-Columbian times. The cacao bean (T. cacao) is an essential ingredient in the chocolate industry. However, recent research has explored the potential for innovating chocolate formulations by partially substituting T. grandiflorum and T. bicolor beans, which are collectively referred to as ‘Blend’. The growing development of the chocolate industry has led to the need to revalue its byproducts, generating renewed interest in Theobroma mucilage. In the case of T. grandiflorum and T. bicolor, the mucilage has traditionally been used as the primary product, with the beans being considered as byproducts.

The mucilage of Theobroma spp. has attracted interest due to its classification as a promising ingredient based on its valuable contents and availability. The mucilage contains a high concentration of sugars (sucrose, glucose and fructose), pectin, dietary fiber (hemicellulose and cellulose), and micronutrients (N, Ca and K). Furthermore, the presence of volatile compounds has been identified as a contributing factor to the floral aromas exhibited. From a functional perspective, the presence of mucilage is indicative of the high content of methylxanthines, polyphenols and organic acids (mainly citric and malic acid), which collectively confer a high antioxidant capacity.

The valorization of mucilage as a byproduct of the agro-industrial sector represents a strategic alternative for enhancing the economic and environmental sustainability of the Theobroma spp. production chain. This approach promotes the incorporation of mucilage as a functional ingredient, natural additive, substrate, and nutraceutical. However, agro-industrial waste intended for food production is subject to stringent regulatory requirements regarding environmental protection, safety, and quality. In view of the above, extracting mucilage in the harvest field carries a high risk of microbiological contamination and accelerated fermentation processes. Therefore, a comprehensive approach is required that combines technological innovation with compliance with international regulatory frameworks and specific regulations in each country.

The growing consumer preference for healthy diets has increased the demand for biologically active enriched foods. However, it has been proven that the application of uncontrolled heat treatments and prolonged exposure to the environment can have a significant impact on the functional properties and volatile composition of Theobroma spp. mucilage. In the current context, future prospects focus on the use of emerging technologies, such as freeze-drying, spray drying, UHT pasteurization and the incorporation of high hydrostatic pressures (HPP), with the aim of preserving functional compounds, minimizing bacterial load and efficiently conserving the sensory properties of mucilage. Due to its high sugar content, mucilage can be used as a fermentation substrate in the production of beer, kombucha, wine and spirits. At the same time, its structural properties derived from the presence of pectin make it an ideal stabilizer for the production of nectars, ice creams and jams. It is also important to highlight the biotechnological applications of the product in cellulose biosynthesis and biofilm production.

In this regard, the future prospects for the food industry focus on the development of new innovative products that preserve these compounds, ensuring not only their safety as well as the technological viability, process scalability, and compliance with legislation and directives on new foods derived from Theobroma spp. mucilage.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.R.H.-C., H.M.C.-S., L.Q.C., S.C.A.-A. and A.P.-R.; methodology, F.R.H.-C. and S.C.A.-A.; formal analysis, F.R.H.-C. and S.C.A.-A.; project administration, A.P.-R.; supervision, S.C.A.-A.; writing—original draft, F.R.H.-C.; validation, F.R.H.-C., H.M.C.-S., L.Q.C., S.C.A.-A. and A.P.-R.; visualization, F.R.H.-C.; writing—review & editing, F.R.H.-C., H.M.C.-S., L.Q.C., S.C.A.-A. and A.P.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by resources from Canon and Sobrecanon (RCO N° 305-2023-COO-UNIQ) at the Universidad Nacional Intercultural de Quillabamba.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mar, J.M.; da Fonseca Júnior, E.Q.; Corrêa, R.F.; Campelo, P.H.; Sanches, E.A.; Bezerra, J.d.A. Theobroma spp.: A Review of It’s Chemical and Innovation Potential for the Food Industry. Food Chem. Adv. 2024, 4, 100683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Meneses, C.J.; Feregrino-Pérez, A.A.; Gutiérrez-Antonio, C. Potential Use of Industrial Cocoa Waste in Biofuel Production. J. Chem. 2021, 2021, 3388067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motamayor, J.C.; Mockaitis, K.; Schmutz, J.; Haiminen, N.; Livingstone, D.; Cornejo, O.; Findley, S.D.; Zheng, P.; Utro, F.; Royaert, S.; et al. The Genome Sequence of the Most Widely Cultivated Cacao Type and Its Use to Identify Candidate Genes Regulating Pod Color. Genome Biol. 2013, 14, r53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tineo, D.; Calderon, M.S.; Maicelo, J.L.; Oliva, M.; Huamán-Pilco, Á.F.; Ananco, O.; Bustamante, D.E. Characterization and Phylogenetic Analysis of the Complete Plastid Genome of Theobroma bicolor (Malvaceae) from Peru. Mitochondrial DNA Part B Resour. 2024, 9, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toxopeus, H. Botany, Types and Populations. Cocoa 2001, 11–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prance, G.T. Fruits of Tropical Climates|Fruits of Central and South America. In Encyclopedia of Food Sciences and Nutrition; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 2810–2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinupp, V.F.; Lorenzi, H.; Cavalleiro, A.d.S.; Souza, V.C.; Brochini, V. Plantas Alimentícias Não Convencionais (PANC) No Brasil: Guia de Identificação, Aspectos Nutricionais e Receitas Ilustradas; Plantarum Institute for Flora Studies: São Paulo, Brazil, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Mora, W.; Jorrin-Novo, J.V.; Melgarejo, L.M. Substantial Equivalence Analysis in Fruits from Three Theobroma Species through Chemical Composition and Protein Profiling. Food Chem. 2018, 240, 496–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papillo, V.A.; Locatelli, M.; Travaglia, F.; Bordiga, M.; Garino, C.; Coïsson, J.D.; Arlorio, M. Cocoa Hulls Polyphenols Stabilized by Microencapsulation as Functional Ingredient for Bakery Applications. Food Res. Int. 2019, 115, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugliese, A.G.; Tomas-Barberan, F.A.; Truchado, P.; Genovese, M.I. Flavonoids, Proanthocyanidins, Vitamin C, and Antioxidant Activity of Theobroma grandiflorum (Cupuassu) Pulp and Seeds. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 2720–2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balentic, J.P.; Ačkar, Đ.; Jokic, S.; Jozinovic, A.; Babic, J.; Miličevic, B.; Ubaric, D.; Pavlovic, N. Cocoa Shell: A By-Product with Great Potential for Wide Application. Molecules 2018, 23, 1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llerena, W.; Samaniego, I.; Vallejo, C.; Arreaga, A.; Zhunio, B.; Coronel, Z.; Quiroz, J.; Angós, I.; Carrillo, W. Profile of Bioactive Components of Cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.) By-Products from Ecuador and Evaluation of Their Antioxidant Activity. Foods 2023, 12, 2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, N.; Romero, M.P.; Macià, A.; Reguant, J.; Anglès, N.; Morelló, J.R.; Motilva, M.J. Comparative Study of UPLC–MS/MS and HPLC–MS/MS to Determine Procyanidins and Alkaloids in Cocoa Samples. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2010, 23, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanaud, C.; Vignes, H.; Utge, J.; Valette, G.; Rhoné, B.; Garcia Caputi, M.; Angarita Nieto, N.S.; Fouet, O.; Gaikwad, N.; Zarrillo, S.; et al. A Revisited History of Cacao Domestication in Pre-Columbian Times Revealed by Archaeogenomic Approaches. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarrillo, S.; Gaikwad, N.; Lanaud, C.; Powis, T.; Viot, C.; Lesur, I.; Fouet, O.; Argout, X.; Guichoux, E.; Salin, F.; et al. The Use and Domestication of Theobroma cacao during the Mid-Holocene in the Upper Amazon. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 2, 1879–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Souza, P.A.; Moreira, L.F.; Sarmento, D.H.A.; da Costa, F.B. Exotic Fruits Reference Guide; Academic Press: London, UK, 2018; pp. 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colli-Silva, M.; Richardson, J.E.; Neves, E.G.; Watling, J.; Figueira, A.; Pirani, J.R. Domestication of the Amazonian Fruit Tree Cupuaçu May Have Stretched over the Past 8000 Years. Commun. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, O.; Paull, R. Exotic Fruits and Nuts of the New World; CABI: Birmingham, UK, 2014; ISBN 1780645058. [Google Scholar]

- Quijano, C.E.; Pino, J.A. Volatile Compounds of Copoazú (Theobroma grandiflorum Schumann) Fruit. Food Chem. 2007, 104, 1123–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, J.d.A.; Corrêa, R.F.; Sanches, E.A.; Lamarão, C.V.; Stringheta, P.C.; Martins, E.; Campelo, P.H. “Cupuaçu” (Theobroma grandiflorum): A Brief Review on Chemical and Technological Potential of This Amazonian Fruit. Food Chem. Adv. 2024, 5, 100747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benlloch-Tinoco, M.; Nuñez Ramírez, J.M.; García, P.; Gentile, P.; Girón-Hernández, J. Theobroma Genus: Exploring the Therapeutic Potential of T. Grandiflorum and T. Bicolor in Biomedicine. Food Biosci. 2024, 61, 104755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, R.; Rodriguez, C.; Ruiz, C.; Portales, R.; Neyra, E.; Patel, K.; Mogrovejo, J.; Salazar, G.; Hurtado, J. Cacao Chuncho Del Cusco. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322992031_CACAO_CHUNCHO_DEL_CUZCO (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Febrianto, N.A.; Zhu, F. Comparison of Bioactive Components and Flavor Volatiles of Diverse Cocoa Genotypes of Theobroma grandiflorum, Theobroma bicolor, Theobroma subincanum and Theobroma cacao. Food Res. Int. 2022, 161, 111764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.L.F.; Abreu, V.K.G.; Rodrigues, S. Cupuassu—Theobroma grandiflorum. In Exotic Fruits Reference Guide; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 159–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, T.K. Theobroma Bicolor. In Edible Medicinal And Non Medicinal Plants; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 204–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, A.A.; Moncada, J.; Idarraga, A.; Rosenberg, M.; Cardona, C.A. Potential of the Amazonian Exotic Fruit for Biorefineries: The Theobroma Bicolor (Makambo) Case. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 86, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, K.H.N.; García, N.V.M.; Vega, R.C. Cocoa By-Products. In Food Wastes and By-Products: Nutraceutical and Health Potential; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 373–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Rodriguez, J.; Aguayo-Flores, M.; Mendoza-Narvaez, A.; Alanis Acosta-Baca, A.; Paucar-Menacho, L.M. Copoazú (Theobroma grandiflorum): Caracterización Botánica, Composición Nutricional, Actividad Antioxidante y Compuestos Bioactivos. Agroind. Sci. 2021, 11, 339–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlán Vásquez, A.L. Caracterización Del Fruto de Theobroma Bicolor y Sus Posibles Aplicaciones; University of the Valley of Guatemala: Guatemala City, Guatemala, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bickel Haase, T.; Babat, R.H.; Zorn, H.; Gola, S.; Schweiggert-Weisz, U. Enzyme-Assisted Hydrolysis of Theobroma cacao L. Pulp. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 18, 101466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickel Haase, T.; Schweiggert Weisz, U.; Ortner, E.; Zorn, H.; Naumann, S. Aroma Properties of Cocoa Fruit Pulp from Different Origins. Molecules 2021, 26, 7618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrunátegui-Jácome, A.; Vera-Chang, J.; Alvarado-Vásquez, K.; Intriago-Flor, F.; Vásquez-Cortez, L.; Revilla-Escobar, K.; Aldas-Morejon, J.; Radice, M.; Naga-Raju, M.; Durazno-Delgado, L.; et al. Aprovechamiento Del Mucílago de Cacao Mocambo (Theobroma Bicolor Hump & Bonpl. L) Para La Obtención de Un Néctar. Agroind. Sci. 2024, 14, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arciniega, G.; Espinoza, R. Optimización de Una Bebida a Base Del Mucílago Del Cacao (Theobroma cacao), Como Aprovechamiento de Uno de Sus Subproductos. Dominio de Las Cienc. 2020, 6, 310–326. [Google Scholar]

- Amable, C.; Torres, V.; Gilberto, R.; Ocampo, D.; Gustavo, J.; Zamora, Q. Mucilago de Cacao (Theobroma cacao L.) Como Inoculo Para Mejorar El Sabor y Textura Del Queso Mozzarella. Centaurus 2020, 1, 80–87. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Castro, R.; Guerrero, R.; Valero, A.; Franco-Rodriguez, J.; Posada-Izquierdo, G. Cocoa Mucilage as a Novel Ingredient in Innovative Kombucha Fermentation. Foods 2024, 13, 1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criollo-Nuñez, J.; Fonseca-Blanco, J.D.; Lopez-Hernandez, M.D.P.; Sandoval-Aldana, A.P.; Criollo-Cruz, D. Estudio Comparativo de Dos Enzimas Pectinolíticas En La Licuefacción de La Pulpa de Copoazú (Theobroma grandiflorum) y Extracción de Fibra Dietaria. Ing. Y Compet. 2022, 24, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández Escobar, Á.O.; Erazo Solórzano, C.Y.; Torres Segarra, C.V.; Torres Navarrete, É.D.; Tuárez García, D.A.; Díaz Ocampo, R.G. Extracción de Mucílago de Cáscara de Theobroma cacao L. Para Uso En Clarificación de Jugos de Saccharum Officinarum. Cienc. Y Tecnol. 2022, 15, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saag, L.M.K.; Sanderson, G.R.; Moyna, P.; Ramos, G. Cactaceae Mucilage Composition. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1975, 26, 993–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, J.H.; Ong, D.S.M.; Ng, F.S.K.; Hua, X.Y.; Tay, W.L.W.; Henry, C.J. Application of Chia (Salvia Hispanica) Mucilage as an Ingredient Replacer in Foods. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 115, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aftab, K.; Hameed, S.; Umbreen, H.; Ali, S.; Rizwan, M.; Alkahtani, S.; Abdel-Daim, M.M. Physicochemical and Functional Potential of Hydrocolloids Extracted from Some Solanaceae Plants. J. Chem. 2020, 2020, 3563945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beikzadeh, S.; Khezerlou, A.; Jafari, S.M.; Pilevar, Z.; Mortazavian, A.M. Seed Mucilages as the Functional Ingredients for Biodegradable Films and Edible Coatings in the Food Industry. Adv. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2020, 280, 102164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, C.L.P.; Andrade, L.A.; Pereira, J. Optimization of Taro Mucilage and Fat Levels in Sliced Breads. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 5890–5897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, L.A.; Nunes, C.A.; Pereira, J. Relationship between the Chemical Components of Taro Rhizome Mucilage and Its Emulsifying Property. Food Chem. 2015, 178, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afoakwa, E.; Kongor, J.; Takrama, J.; Budu, A. Changes in Nib Acidification and Biochemical Composition during Fermentation of Pulp Pre-Conditioned Cocoa (Theobroma cacao) Beans. Int. Food Res. J. 2013, 20, 1843–1853. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, A.J.; Cardenas-Torres, E.; Miller, M.J.; Zhao, S.D.; Engeseth, N.J. Microbes Associated with Spontaneous Cacao Fermentations—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2022, 5, 1452–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, A.S. Fermentation and Organoleptic Quality of Cacao as Affected by Partial Removal of Pulp Juices from the Beans Prior to Curing; Ministério da Agricultura, Pecuária e Abastecimento (MAPA): Brasília, Brazil, 1979; Volume 9. [Google Scholar]

- Haruna, L.; Abano, E.E.; Teye, E.; Tukwarlba, I.; Adu, S.; Agyei, K.J.; Kuma, E.; Yeboah, W.; Lukeman, M. Effect of Partial Pulp Removal and Fermentation Duration on Drying Behavior, Nib Acidification, Fermentation Quality, and Flavor Attributes of Ghanaian Cocoa Beans. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 17, 101211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu-Thi; Nguyen, K.-N.; Tran, C.-H.; Nguyen, B.-P. Thang Quality Assessment During the Fermentation of Cocoa Beans: Effects of Partial Mucilage Removal. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manag. 2022, 26, 1369–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizcaino-Almeida, C.R.; Guajardo-Flores, D.; Caroca-Cáceres, R.; Serna-Saldívar, S.O.; Briones-García, M.; Lazo-Vélez, M.A. Non-Conventional Fermentation at Laboratory Scale of Cocoa Beans: Using Probiotic Microorganisms and Substitution of Mucilage by Fruit Pulps. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 57, 4307–4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldarriaga, S.; Rodríguez-Salazar, C.A.; Recalde-Reyes, D.P.; Paladines Beltrán, G.M.; Cuéllar Álvarez, L.N.; Silva Ortíz, Y.L. Phenolic Composition, Antioxidant, and Anti-Proliferative Activities Against Human Colorectal Cancer Cells of Amazonian Fruits Copoazú (Theobroma grandiflorum) and Buriti (Mauritia flexuosa). Molecules 2025, 30, 1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunetto, M.d.R.; Gutiérrez, L.; Delgado, Y.; Gallignani, M.; Zambrano, A.; Gómez, Á.; Ramos, G.; Romero, C. Determination of Theobromine, Theophylline and Caffeine in Cocoa Samples by a High-Performance Liquid Chromatographic Method with on-Line Sample Cleanup in a Switching-Column System. Food Chem. 2007, 100, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borja Fajardo, J.G.; Horta Tellez, H.B.; Peñaloza Atuesta, G.C.; Sandoval Aldana, A.P.; Mendez Arteaga, J.J. Antioxidant Activity, Total Polyphenol Content and Methylxantine Ratio in Four Materials of Theobroma cacao L. from Tolima, Colombia. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, E.N.; Da Cruz Ramos, D.; Miranda Menezes, L.; De Souza, A.O.; Da Silva Lannes, S.C.; Da Silva, M.V. Nutritional Value and Antioxidant Capacity of “Cocoa Honey” (Theobroma cacao L.). Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 34, 755–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyago-Cruz, E.; Salazar, I.; Guachamin, A.; Alomoto, M.; Cerna, M.; Mendez, G.; Heredia-Moya, J.; Vera, E. Bioactive Compounds, Antioxidant, and Antimicrobial Activity of Seeds and Mucilage of Non-Traditional Cocoas. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickel Haase, T.; Naumann-Gola, S.; Ortner, E.; Zorn, H.; Schweiggert-Weisz, U. Thermal Stabilisation of Cocoa Fruit Pulp—Effects on Sensory Properties, Colour and Microbiological Stability. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2023, 7, 100549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meersman, E.; Struyf, N.; Kyomugasho, C.; Jamsazzadeh Kermani, Z.; Santiago, J.S.; Baert, E.; Hemdane, S.; Vrancken, G.; Verstrepen, K.J.; Courtin, C.M.; et al. Characterization and Degradation of Pectic Polysaccharides in Cocoa Pulp. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 9726–9734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saavedra-Sanabria, O.L.; Durán, D.; Cabezas, J.; Hernández, I.; Blanco-Tirado, C.; Combariza, M.Y. Cellulose Biosynthesis Using Simple Sugars Available in Residual Cacao Mucilage Exudate. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 274, 118645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, C.S.O.; Da Silva, M.L.C.; Camilloto, G.P.; Machado, B.A.S.; Hodel, K.V.S.; Koblitz, M.G.B.; Carvalho, G.B.M.; Uetanabaro, A.P.T. Potential Applicability of Cocoa Pulp (Theobroma cacao L) as an Adjunct for Beer Production. Sci. World J. 2020, 2020, 3192585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Ospina, J.; Lucas-González, R.; Viuda-Martos, M.; Fernández-López, J.; Pérez-Álvarez, J.Á.; Martuscelli, M.; Chaves-López, C. Bioactive Compounds and Techno-Functional Properties of High-Fiber Co-Products of the Cacao Agro-Industrial Chain. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogez, H.; Buxant, R.; Mignolet, E.; Souza, J.N.S.; Silva, E.M.; Larondelle, Y. Chemical Composition of the Pulp of Three Typical Amazonian Fruits: Araça-Boi (Eugenia stipitata), Bacuri (Platonia insignis) and Cupuaçu (Theobroma grandiflorum). Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2004, 218, 380–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagmignan, A.; Mendes, Y.C.; Mesquita, G.P.; dos Santos, G.D.C.; Silva, L.d.S.; de Souza Sales, A.C.; Castelo Branco, S.J.d.S.; Junior, A.R.C.; Bazán, J.M.N.; Alves, E.R.; et al. Short-Term Intake of Theobroma grandiflorum Juice Fermented with Lacticaseibacillus Rhamnosus ATCC 9595 Amended the Outcome of Endotoxemia Induced by Lipopolysaccharide. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sifuentes Sangama, M.A. Evaluación Físico-Química de La Pulpa y Semilla de Dos Morfotipos Del Fruto Macambo “Theobroma Bicolor” (Humb. & Bompl.) de La Región Loreto, 2015; Universidad Nacional de la Amazonía Peruana: Iquitos, Peru, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sotelo, A.; Alvarez, R.G. Chemical Composition of Wild Theobroma Species and Their Comparison to the Cacao Bean. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1991, 39, 1940–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vriesmann, L.C.; de Oliveira Petkowicz, C.L. Polysaccharides from the Pulp of Cupuassu (Theobroma grandiflorum): Structural Characterization of a Pectic Fraction. Carbohydr. Polym. 2009, 77, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Torres, D.E.; Assunção, D.; Mancini, P.; Pavan Torres, R.; Mancini-Filho, J. Antioxidant Activity of Macambo (Theobroma bicolor L.) Extracts. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2002, 104, 278–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA. Technical Report on the Notification of Pulp from Theobroma cacao L. as a Traditional Food from a Third Country Pursuant to Article 14 of Regulation (EU) 2015/2283. EFSA Support. Publ. 2019, 16, 1724E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahmann, C.; Rinas, T.; Niemenak, N.; Hegmann, E.; Seigler, D.; Bisping, B.; Lieberei, R. The Influence of Fermentation-like Incubation on Cacao Seed Testa and Composition of Testa Associated Mucilage. J. Appl. Bot. Food Qual. 2020, 93, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiteneder, H.; Ebner, C. Molecular and Biochemical Classification of Plant-Derived Food Allergens. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2000, 106, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann-Sommergruber, K. Pathogenesis-Related (PR)-Proteins Identified as Allergens. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2002, 30, 930–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanakis, C.M. Nutraceutical and Functional Food Components. In Nutraceutical and Functional Food Components: Effects of Innovative Processing Techniques; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babbar, R.; Kaur, A.; Vanya; Arora, R.; Gupta, J.K.; Wal, P.; Tripathi, A.K.; Koparde, A.A.; Goyal, P.; Ramniwas, S.; et al. Impact of Bioactive Compounds in the Management of Various Inflammatory Diseases. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2024, 30, 1880–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Direito, R.; Barbalho, S.M.; Sepodes, B.; Figueira, M.E. Plant-Derived Bioactive Compounds: Exploring Neuroprotective, Metabolic, and Hepatoprotective Effects for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, A.L.F.; Feitosa, W.S.C.; Abreu, V.K.G.; Lemos, T.d.O.; Gomes, W.F.; Narain, N.; Rodrigues, S. Impact of Fermentation Conditions on the Quality and Sensory Properties of a Probiotic Cupuassu (Theobroma grandiflorum) Beverage. Food Res. Int. 2017, 100, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grillo, G.; Boffa, L.; Binello, A.; Mantegna, S.; Cravotto, G.; Chemat, F.; Dizhbite, T.; Lauberte, L.; Telysheva, G. Cocoa Bean Shell Waste Valorisation; Extraction from Lab to Pilot-Scale Cavitational Reactors. Food Res. Int. 2019, 115, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauchen, J.; Bortl, L.; Huml, L.; Miksatkova, P.; Doskocil, I.; Marsik, P.; Villegas, P.P.P.; Flores, Y.B.; Van Damme, P.; Lojka, B.; et al. Phenolic Composition, Antioxidant and Anti-Proliferative Activities of Edible and Medicinal Plants from the Peruvian Amazon. Rev. Bras. de Farmacogn. 2016, 26, 728–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morante-Carriel, L.; Abasolo, F.; Bastidas-Caldes, C.; Paz, E.A.; Huaquipán, R.; Díaz, R.; Valdes, M.; Cancino, D.; Sepúlveda, N.; Quiñones, J. Isolation and Characterization of Lactic Acid Bacteria from Cocoa Mucilage and Meat: Exploring Their Potential as Biopreservatives for Beef. Microbiol. Res. 2023, 14, 1150–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panganiban, C.A.; Panganiban, C.A.; Reyes, R.B.; Agojo, I.; Armedilla, R.; Consul, J.Z.; Dagli, H.F.; Esteban, L. Antibacterial Activity of Cacao (Theobroma cacao Linn.) Pulp Crude Extract Against Selected Bacterial Isolates. JPAIR Multidiscip. Res. 2010, 4, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona-Hernandez, J.C.; González-Correa, C.H.; Le, M.; Idárraga-Mejía, A.M. Flavonoid/Polyphenol Ratio in Mauritia Flexuosa and Theobroma grandiflorum as an Indicator of Effective Antioxidant Action. Molecules 2021, 26, 6431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Calderón, J.; Calderón-Jaimes, L.; Guerra-Hernández, E.; García-Villanova, B. Antioxidant Capacity, Phenolic Content and Vitamin C in Pulp, Peel and Seed from 24 Exotic Fruits from Colombia. Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 2047–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazaruddin, R.; Seng, L.K.; Hassan, O.; Said, M. Effect of Pulp Preconditioning on the Content of Polyphenols in Cocoa Beans (Theobroma cacao) during Fermentation. Ind. Crops Prod. 2006, 24, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopera, Y.E.; Fantinelli, J.; González Arbeláez, L.F.; Rojano, B.; Ríos, J.L.; Schinella, G.; Mosca, S. Antioxidant Activity and Cardioprotective Effect of a Nonalcoholic Extract of Vaccinium Meridionale Swartz during Ischemia-Reperfusion in Rats. In Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2013; Hindawi Publishing Corporation: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsen, M.H.; Halvorsen, B.L.; Holte, K.; Bøhn, S.K.; Dragland, S.; Sampson, L.; Willey, C.; Senoo, H.; Umezono, Y.; Sanada, C.; et al. The Total Antioxidant Content of More than 3100 Foods, Beverages, Spices, Herbs and Supplements Used Worldwide. Nutr. J. 2010, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shofian, N.M.; Hamid, A.A.; Osman, A.; Saari, N.; Anwar, F.; Dek, M.S.P.; Hairuddin, M.R. Effect of Freeze-Drying on the Antioxidant Compounds and Antioxidant Activity of Selected Tropical Fruits. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 12, 4678–4692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drużyńska, B.; Łukasiewicz, J.; Majewska, E.; Wołosiak, R. Optimization of the Extraction Conditions of Polyphenols from Red Clover (Trifolium pratense L.) Flowers and Evaluation of the Antiradical Activity of the Resulting Extracts. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi-Parizad, P.; De Nisi, P.; Scaglia, B.; Scarafoni, A.; Pilu, S.; Adani, F. Recovery of Phenolic Compounds from Agro-Industrial by-Products: Evaluating Antiradical Activities and Immunomodulatory Properties. Food Bioprod. Process. 2021, 127, 338–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, N.R.; Matar, M.; Walid, L.; Darwish, S. A Comparative Study of the Antimicrobial Activity of Cacao Ethanol Extract and Chlorhexidine Digluconate on Salivary Streptococcus Mutans. Egypt. Dent. J. 2024, 70, 2175–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulyn, A.T.; Inya, O.J.; Okewu, A.P. Phytochemical Screening and Antimicrobial Activity of Theobroma cacao on Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Samonella spp. and Shigella spp. Int. J. Sch. Res. Chem. Pharm. 2022, 1, 001–010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, C.V.A.; Salimo, Z.M.; de Souza, T.A.; Reyes, D.E.; Bassicheto, M.C.; de Medeiros, L.S.; Sartim, M.A.; de Carvalho, J.C.; Gonçalves, J.F.C.; Monteiro, W.M.; et al. Cupuaçu (Theobroma grandiflorum): A Multifunctional Amazonian Fruit with Extensive Benefits. Food Res. Int. 2024, 192, 114729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afoakwa, E.O.; Quao, J.; Budu, A.S.; Takrama, J.; Saalia, F.K. Effect of Pulp Preconditioning on Acidification, Proteolysis, Sugars and Free Fatty Acids Concentration during Fermentation of Cocoa (Theobroma cacao) Beans. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2011, 62, 755–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, L.K.; Ramos, K.K.; Ávila, P.F.; Goldbeck, R.; Vieira, J.B.; Efraim, P. Influence of Cocoa Varieties on Carbohydrate Composition and Enzymatic Activity of Cocoa Pulp. Food Res. Int. 2023, 173, 113393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetschik, I.; Kneubühl, M.; Chatelain, K.; Schlüter, A.; Bernath, K.; Hühn, T. Investigations on the Aroma of Cocoa Pulp (Theobroma cacao L.) and Its Influence on the Odor of Fermented Cocoa Beans. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 2467–2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, M.R.B.; Shibamoto, T. Volatile Composition of Some Brazilian Fruits: Umbu-Caja (Spondias citherea), Camu-Camu (Myrciaria dubia), Araca-Boi (Eugenia stipitata), and Cupuacu (Theobroma grandiflorum). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 1263–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia, M.; Pérez-Beltrán, M.; López, G.D.; Carazzone, C.; Galeano Garcia, P. Molecular Networking from Volatilome of Theobroma grandiflorum (Copoazu) at Different Stages of Maturation Analyzed by HS-SPME-GC-MS. Molecules 2025, 30, 1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quijano, C.E.; Pino, J.A. Analysis of Volatile Compounds of Cacao Maraco (Theobroma bicolor Humb. et Bonpl.) Fruit. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2009, 21, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskes, A.; Ahnert, D.; Garcia Carrion, L.; Seguine, E.; Assemat, S.; Guarda, D.; Garcia, R.P. Evidence on the Effect of the Cocoa Pulp Flavour Environment during Fermentation on the Flavour Profile of Chocolates. In Proceedings of the 17th Conférence Internationale sur la Recherche Cacaoyère, Yaounde, Cameroun, 15–20 October 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pino, J.A.; Ceballos, L.; Quijano, C.E. Headspace Volatiles of Theobroma cacao L. Pulp from Colombia. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2010, 22, 113–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, S.; Jennings, W.G. Volatile Composition of Certain Amazonian Fruits. Food Chem. 1979, 4, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulanger, R.; Crouzet, J. Free and Bound Flavour Components of Amazonian Fruits: 3-Glycosidically Bound Components of Cupuacu. Food Chem. 2000, 70, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.P.; Frasao, B.S.; Silva, A.C.O.; Freitas, M.Q.; Franco, R.M.; Conte-Junior, C.A. Cupuassu (Theobroma grandiflorum) Pulp, Probiotic, and Prebiotic: Influence on Color, Apparent Viscosity, and Texture of Goat Milk Yogurts. J. Dairy. Sci. 2015, 98, 5995–6003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, P.B.; Machado, W.M.; Guimarães, A.G.; De Carvalho, G.B.M.; Magalhães-Guedes, K.T.; Druzian, J.I. Cocoa’s Residual Honey: Physicochemical Characterization and Potential as a Fermentative Substrate by Saccharomyces Cerevisiae AWRI726. Sci. World J. 2019, 2019, 5698089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roini, C.; Asbirayani Limatahu, N.; Mulya Hartati, T. Sundari Characterization of Cocoa Pulp (Theobroma cacao L) from South Halmahera as an Alternative Feedstock for Bioethanol Production. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 276, 012038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, D.R.; Schwan, R.F.; Freire, E.S.; Dos Santos Serôdio, R. Elaboration of a Fruit Wine from Cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.) Pulp. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2007, 42, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejo Torres, C.; Díaz Ocampo, R.; Morales Rodríguez, W.; Soria Velasco, R.; Fabian Vera Chang, J.; Baren Cedeño, C. Utilización Del Mucílago de Cacao, Tipo Nacional y Trinitario, En La Obtención de Jalea. Rev. ESPAMCIENCIA 2016, 7, 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Klis, V.; Pühn, E.; Jerschow, J.J.; Fraatz, M.A.; Zorn, H. Fermentation of Cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.) Pulp by Laetiporus Persicinus Yields a Novel Beverage with Tropical Aroma. Fermentation 2023, 9, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, P.T.S.; Aouada, F.A.; De Moura, M.R. Fabricação de Filmes Bionanocompósitos à Base de Pectina e Polpa de Cacau Com Potencial Uso Como Embalagem Para Alimentos. Quim. Nova 2017, 40, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Vega, L.; Martínez-Suárez, J.F.; Sánchez-Garzón, F.S.; Hernández-Carrión, M.; Nerio, L.S. Optimization of the Encapsulation Process of Cupuassu (Theobroma grandiflorum) Pulp by Spray Drying as an Alternative for the Valorization of Amazonian Fruits. LWT 2023, 184, 114994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vuyst, L.; Weckx, S. The Cocoa Bean Fermentation Process: From Ecosystem Analysis to Starter Culture Development. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2016, 121, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endraiyani, V.; Ludescher, R.D.; Di, R.; Karwe, M.V. Total Phenolics and Antioxidant Capacity of Cocoa Pulp: Processing and Storage Study. J. Food Process Preserv. 2017, 41, e13029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firdaus, F.; Desmiarti, R.; Praputri, E.; Amir, A. Production of Cocoa Pulp Syrup by Utilizing Local Sugar Sources. J. Appl. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2022, 6, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICCO International Cocoa Organization. The World Cocoa Economy, Current Status, Challenges and Prospects. Available online: https://www.icco.org/economy/#board (accessed on 19 February 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.