Abstract

Constipation is a common gastrointestinal disorder that seriously affects quality of life and is associated with multiple secondary complications. Barley leaves (BLs) have been suggested as potential functional foods for constipation prevention. Here, we investigated the preventive effects of common barley leaves (CBLs) and hulless barley leaves (HBLs) in a loperamide-induced constipation model in C57BL/6 mice. Both BLs improved stool parameters and gastrointestinal transit. Notably, high-dose HBLs increased stool weight to 263.84 ± 66.70 mg and stool amount to 250.20 ± 66.88 pellets, which were 12.7 and 11.1 times higher than those in the model group, respectively. BLs also modulated gut motility-related hormones (MTL, SP, Gas, SS, and VIP) and normalized colonic AQP3, AQP4, and 5-HT4R expression levels. Furthermore, BLs enhanced SCFAs production and modulated gut microbiota by increasing Bacteroides abundance and decreasing Akkermansia abundance. CBLs and HBLs also exhibited distinct mechanisms. High-dose CBLs affected SERT expression, whereas HBLs uniquely decreased Alistipes abundance and increased SCFA production. These findings suggest that BLs may help prevent loperamide-induced constipation in mice by modulating the gut barrier and microbiota. Future studies should identify key active components and validate efficacy in longer-term and clinical studies.

1. Introduction

Constipation is a widespread bowel disorder that influences approximately 12–19% of the global population and significantly impacts daily life and productivity, leading to considerable personal and societal burdens [1]. It is clinically characterized by various uncomfortable symptoms, including difficult defecation, infrequent bowel movements, or a sensation of incomplete evacuation [2]. Long-term constipation can lead to serious gastrointestinal diseases, such as accumulation of intestinal toxins, irritable bowel syndrome, and colon cancer [3], and is proposed to be associated with cardiovascular, respiratory, and nervous systems [4]. Thus, there is an urgent need to identify safe and effective strategies for the prevention and treatment of constipation. Current pharmacological interventions primarily include laxatives, secretagogues, serotonergic agonists, and suppositories, all of which are associated with significant side effects such as flatulence, bloating, and abdominal pain [5]. Therefore, plant-derived functional foods with minimal adverse effects have attracted increasing interest as alternative approaches for preventing and alleviating constipation, thereby potentially reducing the incidence of related diseases.

Barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) is a highly significant crop in global agriculture and can be divided into two primary types based on grain characteristics: hulled barley and hulless (naked) barley, with hulless barley (Hordeum vulgare L. var. nudum Hook.f.) as a typical example of the latter [6]. Barley leaves (BLs) are derived from the young grass of barley, the primary ingredient in a popular green functional drink in Asian countries [7]. Common barley leaves (CBLs), which are derived from hulled barley (i.e., hulled barley leaves), are rich in nutrients such as dietary fiber, protein, minerals, vitamins, and flavonoids [7]. In contrast, hulless barley leaves (HBLs) have been reported to contain higher contents of protein, amylose, and fiber and a lower lipid content than CBLs, attributed to their unique high-altitude growing environment, distinct climatic conditions, and genetics background [8]. Notably, these compositional traits can vary among barley varieties and growing environments [6]. These compositional differences suggest that CBLs and HBLs may exert distinct physiological effects.

Accumulating evidence indicates that BLs can prevent obesity, depression, and gastrointestinal disorders [9,10,11,12,13]. Polysaccharides from HBLs exhibit strong anti-proliferative activity against HT29, Caco-2, 4T1, and CT26 cancer cells [10]. Yan et al. reported that CBL polysaccharides can alleviate hyperlipidemia by regulating dyslipidemia, relieving liver injury, and reshaping intestinal flora structure [11]. Moreover, CBLs have been shown to influence gastrointestinal function in healthy human volunteers and patients with mild constipation [12], and studies in rats have demonstrated that water-insoluble dietary fiber from CBLs can increased fecal weight and shorten gastrointestinal transit time by promoting probiotic growth [13]. Nevertheless, previous studies on BLs have primarily focused on general nutritional and health benefits or on CBLs alone, with limited attention paid to their specific role and mechanisms in preventing constipation. It remains unclear how BLs modulate intestinal barrier function, neurotransmitter signaling, gut microbiota, and short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) production in the context of constipation and whether the distinct nutritional profiles of CBLs and HBLs translate into different protective outcomes.

Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the preventive effects of CBL and HBL interventions on loperamide-induced constipation in C57BL/6 mice. We assessed fecal parameters, gastrointestinal transit efficiency, colonic histomorphology, gene expression related to intestinal barrier function, serum neurotransmitter levels, gut microbiota structure, and short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). By examining CBLs and HBLs within the same experimental framework, we sought to clarify the mechanisms underlying BL-mediated protection against constipation and to determine the scientific relevance of using different barley leaf types as potential ingredients in functional foods aimed at preventing constipation.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Materials

CBLs and HBLs, sourced from Shanghai Ganya Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China), underwent cleaning, freeze-drying, grinding into a fine green powder, and sieving using a 40-mesh screen. Loperamide hydrochloride was commercially acquired from Xi’an Janssen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Xi’an, China). Naloxone hydrochloride was obtained from Jilin Zhenghe Pharmaceutical Group Co., Ltd. (Tonghua, China). Arabic gum and methyl tertiary butyl ether were commercially acquired from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Activated carbon, sulfuric acid, and 2-methylvaleric acid were obtained from Aradin Bio-chem Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

2.2. Compositional Analysis

2.2.1. Determination of Total Phenols and Total Flavonoids

The dried powder (0.5 g) was combined with 10 mL of 40% (v/v) methanol and maintained at 45 °C for 1.5 h. Once cooled, the mixture underwent centrifugation at 4000× g for 10 min, and the resulting supernatant was collected. The total phenolics and flavonoids content of CBLs and HBLs was determined as described previously [14]. The measurements were carried out in triplicate.

2.2.2. Protein Content

The protein of CLBs and HLBs was estimated by using a standard Kjeldahl method (N % × 6.25), as previously described [15]. The measurements were carried out in triplicate.

2.2.3. Dietary Fiber Content

The dietary fiber content of CLBs and HLBs was measured using an enzymatic–gravimetric procedure (AOAC Method 991.43) [16]. The measurements were carried out in triplicate.

2.3. Animal Experiments

All animal procedures were carried out under the authorization of the Animal Ethics Committee of Shanghai Jiao Tong University (No. A2023227-1). A total of 84 male C57BL/6 mice (7–8 weeks, 18–22 g) were randomly assigned to two cohorts to perform a defecation test and a gastrointestinal transit test, respectively. After seven days of adaptive feeding, mice in each cohort were further randomized into seven groups (n = 6 per group): normal control group (NC, saline solution), model group (MC, saline solution), positive drug group (PC, saline solution), low-dose CLBs powder group (L-CB, 0.1 g/kg bw), high-dose CLBs powder group (H-CB, 0.5 g/kg bw), low-dose HLBs powder group (L-HB, 0.1 g/kg bw), and high-dose HLBs powder group (H-LB, 0.5 g/kg bw). The doses of CBLs and HBLs (0.1 and 0.5 g/kg bw) were selected based on our preliminary dose-ranging experiment to ensure good tolerability and to allow evaluation of potential dose-dependent preventive effects during the 7-day intervention. Saline solution, CLBs powder, and HLBs powder were administered by gavage for seven days.

2.4. Defecation Test

Gum arabic (100 g) was dissolved in 1000 mL of deionized water and heated to clarity. Afterward, 50 g of activated carbon solution was added, and the solution was reheated three times.

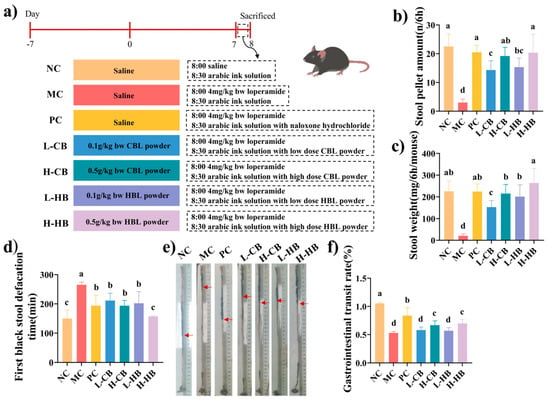

As shown in Figure 1a, after seven days of intervention, the mice were treated with loperamide hydrochloride (4 mg/kg bw) or normal saline (NC group). Thirty minutes later, arabic ink solution was intragastrical administered to the NC and MC groups, while the remaining groups (L-CB, H-CB, L-HB, H-HB) received the ink solution supplemented with their respective intervention powders. Naloxone hydrochloride was selected as a positive drug. Mice in the PC group were administered the arabic ink solution with naloxone hydrochloride (10 mg/kg bw) by gavage. Over a 6 h span, feces were harvested, and the amount and weight of fecal pellets were noted. The time to the first black stool, indicating the interval from activated carbon feeding to initial black feces excretion, was also evaluated.

Figure 1.

The effects of CBLs and HBLs on gastrointestinal indicators in constipated mice. (a) The animal experimental scheme, (b) stool pellet amount, (c) stool weight, (d) first black stool defecation, and (e) gastrointestinal transport rate experimental picture. (f) Gastrointestinal transit rate. The red arrows indicate the ink front position in the small intestine for transit-rate calculation. Results were expressed as mean ± SD (n = 6). Different small letters indicate that values are significantly different at the p < 0.05 level.

2.5. Gastrointestinal Transit

The mice were given loperamide hydrochloride and different arabic inks, similar to the procedure in Section 2.4. After 25 min, the animals were sacrificed and underwent dissection to obtain the entire segment of the small intestine, extending from the pylorus to the ileocecal valve. This measurement was taken as the overall length of the small intestine. The extent of ink migration and the total intestinal length were then recorded. Intestinal motility was expressed as the ratio of ink advancement to the full length of the small intestine, calculated using the following Formula (1).

ink propulsion rate (%) = ink propulsive length/total intestinal length × 100%

Then, the small intestine propulsion rate was derived from Formula (2).

2.6. Gene Expression in the Colon Tissues

The clone tissues were isolated and preserved at −80 °C. The total RNA was extracted and transcribed into cDNA according to the instructions of PrimeScriptTM RT Reagent Kit (Takara, Kusatsu, Shiga, Japan). Primers were synthesized by Sangon Bioengineering Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). GAPDH served as the internal reference, and its stability was verified across all groups prior to normalization. The primer sequences are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

The sequence of primers used to determine gene expression in colon tissue.

2.7. Histopathological Analysis

Colonic samples from three randomly selected mice per group were preserved in 4% paraformaldehyde for at least 48 h. Following this, the tissues were infiltrated with paraffin and cut into 5 μm sections. These sections were subsequently stained using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and examined under a Nikon DS-U3 microscope (Tokyo, Japan).

2.8. Determination of Serum SS, VIP, SP, MTL and Gas Levels

SS, VIP, SP, MTL, and Gas were measured (n = 6 per group) using commercial ELISA kits (Shanghai Yuanju Bio-Technology Venter, Shanghai, China).

2.9. Gut Microbiota Analysis

For microbiota analysis, each group contained six mice. One fecal pellet was collected from each mouse and combined to generate one pooled sample (six pellets per pooled sample). Three pooled fecal samples were prepared per group, and 16S rRNA sequencing was performed (n = 3 pooled samples per group). The gut microbiota analysis was determined as described previously [11].

2.10. Determination of SCFAs in Feces

The analysis of SCFAs was carried out using a previously reported protocol with slight modifications [17]. Fecal samples (n = 3 pooled samples per group) were processed as follows: stool (0.5 g) was added to 800 μL DI water, homogenized, and centrifuged at 13,200× g for 20 min. Acidification was achieved by mixing 0.4 mL of the supernatant with 100 μL of 50% sulfuric acid, after which 0.5 mL of internal standard solution was added (methyl tert-butyl ether containing 0.5 μg/mL 2-methylvalerate). Then, stool was centrifuged again under the same conditions (13,200× g, 20 min). The resulting supernatant was analyzed using a GC-MS system (Agilent 7890B-7000D, Palo Alto, CA, USA). Quantification was performed via an external standard calibration curve. Fecal samples were lyophilized (freeze-dried) to constant weight, and SCFA concentrations were reported as μg/g dry feces.

2.11. Statistical Analysis

The results were statistically analyzed using SPSS software (Version 20.0; SPSS Software, Chicago, IL, USA). Differences among groups were assessed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Duncan’s post hoc test. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The Figures were created using Origin 2025b software (OriginLab Corporation, North Hampton, MA, USA) and GraphPad Prism version 8 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of the Chemical Composition of CBLs and HBLs

As displayed in Table 2, both CBLs and HBLs were rich in dietary fiber and protein, with concentrations notably higher than those of common cereal grains, as previously reported [18]. HBLs contained higher contents of dietary fiber (475.7 ± 1.7 mg/g vs. 448.4 ± 2.1 mg/g) and protein (282.4 ± 1.1 mg/g vs. 219.0 ± 3.4 mg/g) than CBLs, which was also consistent with earlier findings on hulless barley leaves [8]. CBLs, however, exhibited a higher total phenolic content (21.43 ± 0.21 mg/g) than HBLs (7.42 ± 0.1 mg/g). The most pronounced difference was observed in total flavonoids content, with 20.7 ± 0.46 mg/g in CBLs, over 20 times higher than the 1.01 ± 0.06 mg/g detected in HLBs. This pattern contrasts with a previous report indicating higher total flavonoids content in hulless barley leaves [19], suggesting that flavonoid accumulation was strongly influenced by barley variety, growing conditions, harvest stage, extraction, and analytical methods [8,19]. Overall, these results confirm that BLs provide beneficial nutrients and that their phenolic and flavonoid profiles were variety-dependent, which might contribute to their differential effects on constipation prevention.

Table 2.

Chemical composition of CBLs and HBLs.

3.2. Effects of CBLs and HBLs on Defecation Function and Gastrointestinal Transit

Measures of four gastrointestinal indicators are shown in Figure 1b–f. In the MC group, stool weight and amount were markedly reduced compared with the NC group (stool weight: 225.5 ± 47.11 mg vs. 20.75 ± 6.25 mg; stool amount: 238.4 ± 47.11 pellets vs. 22.6 ± 8.19 pellets; p < 0.05), indicating that stool weight and amount were important manifestations of constipation. CBLs and HBLs both prevented these changes, with higher doses producing greater effects. Notably, high-dose HBLs increased stool weight to 263.84 ± 66.70 mg and stool amount to 250.20 ± 66.88, which were approximately 12.7 times and 11.1 times higher than those in the MC group, respectively, representing a marked recovery towards NC levels (Figure 1b,c). Overall, HBLs showed more pronounced effects than CBLs on these parameters.

Gastrointestinal transit function can be assessed by measuring the time it takes for black stool to appear. Loperamide significantly prolonged this interval in the MC group compared with the NC group (226.4 ± 9.20 min vs. 146.4 ± 28.75 min; p < 0.05). In contrast, the PC group and both CBL and HBL treatment groups shortened the time to first black stool in a dose-dependent manner. High-dose CBLs and HBLs reduced this interval to 196.4 ± 18.40 min and 157.2 ± 2.64 min, respectively, representing a reduction of approximately 13.3% and 30.6% relative to the MC group (p < 0.05), with HBLs exerting the most pronounced effect.

Among all groups, the NC group exhibited the highest intestinal propulsion rate (1.05 ± 0.018%), followed by the PC group (0.855 ± 0.140%). Loperamide reduced the transit rate to 0.52 ± 0.025% in the MC group, whereas both CBLs and HBLs significantly increased this parameter (p < 0.05 vs. MC). High-dose HBLs increased the intestinal transit rate to 0.71 ± 0.072%, which was about 1.4 times higher than that of the MC group, indicating a partial restoration of gastrointestinal motility.

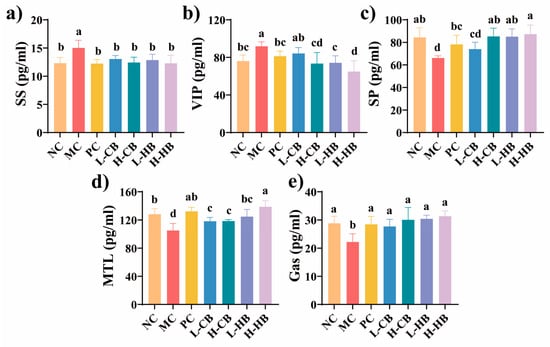

3.3. Effects of CBLs and HBLs on Serum Parameters

As illustrated in Figure 2, the serum excitatory neurotransmitter (MTL, SP, and Gas) levels in the MC group significantly decreased (p < 0.05), while the inhibitory neurotransmitter (SS and VIP) levels increased (p < 0.05). These trends were consistent with previous reports describing loperamide-induced alterations in excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters related to gut motility [20,21]. Notably, therapeutic interventions with naloxone hydrochloride (PC group), HBLs, and high-dose CBLs significantly decreased the SS and VIP levels and substantially increased the levels of MTL, SP, and Gas compared with the MC group (p < 0.05), shifting these indicators toward the levels observed in the NC group. These findings suggested that both CBLs and HBLs exerted regulatory effects on hormones and neurotransmitters associated with gut motility, potentially helping prevent constipation.

Figure 2.

The effects of CBLs and HBLs on serum neurotransmitter level in constipated mice. Serum concentrations of (a) somatostatin (SS), (b) vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), (c) substance P (SP), (d) motilin (MTL), and (e) gastrin (Gas) were measured. Results are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 6). Different small letters indicate that values are significantly different at the p < 0.05 level.

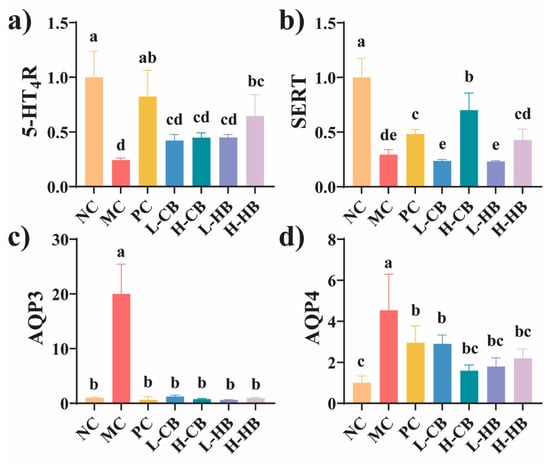

3.4. Effects of CBLs and HBLs on Colon Gene Expressions

Figure 3 presents the gene expression in the colon. Compared to the NC group, the MC group showed decreased expression of 5-HT4R and SERT in the colon, while the expression of AQP3 and AQP4 increased (p < 0.05). In addition, with CBL treatment, colon expression of AQP3 and AQP4 significantly decreased (p < 0.05). Interestingly, high-dose HBL treatment led to a significant increase in colonic 5-HT4R expression (p < 0.05), although low-dose treatment did not show a significant difference. However, high-dose CBL treatment resulted in a significant increase in colonic SERT expression (p < 0.05), with no significant difference observed for the low dose.

Figure 3.

The effects of CBLs and HBLs on mRNA expression in colon tissues after induction of constipation. (a) mRNA expression of 5-HT4R; (b) mRNA expression of SERT; (c) mRNA expression of AQP3; (d) mRNA expression of AQP4. Results are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 6). Different small letters indicate that values are significantly different at the p < 0.05 level.

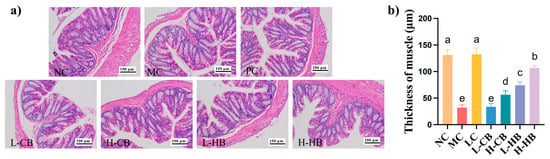

3.5. Effects of CBLs and HBLs on Colon Histological Morphology

As shown in Figure 4, histopathological differences in colon tissues were observed among the groups. Representative H&E-stained images are shown in Figure 4a; the MC group had a reduction in the colonic muscular layer and structural disruption of the mucosal layer compared with the NC group. However, both the CBLs and HBLs groups showed protection against colon damage and preservation of intestinal barrier integrity. Interestingly, the H-HB group exhibited colon morphology similar to that of the NC group. Consistently, quantitative analysis of muscular layer thickness (Figure 4b) showed that loperamide significantly reduced this parameter (NC: 131.17 ± 8.31 μm vs. MC: 31.92 ± 4.90 μm, p < 0.05), while CBLs and HBLs partially restored it, with the most pronounced improvement in the H-HB group (106.56 ± 3.78 μm, p < 0.05 vs. MC). These observations suggested that BLs had a protective effect against constipation-induced colonic injury, with the most pronounced effect found in the H-HB group.

Figure 4.

Protective effects of barley leaves on colonic histology in loperamide-induced constipation in mice. (a) Representative images of H&E staining in the colon tissues; (b) quantification of colonic muscular layer thickness. Results are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). Different small letters indicate that values are significantly different at the p < 0.05 level.

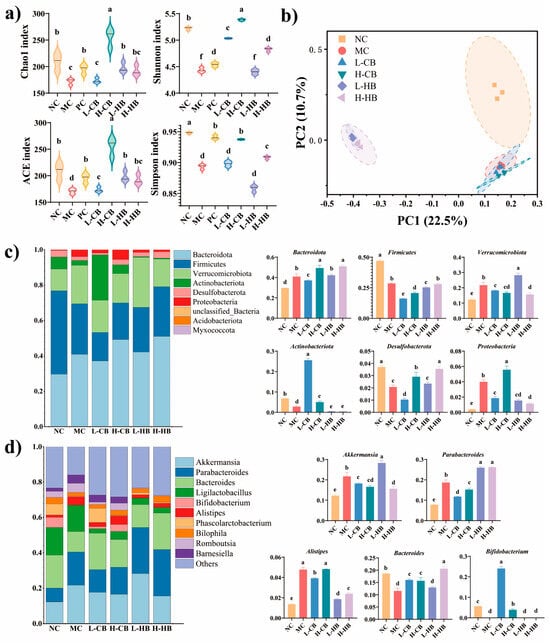

3.6. Effects of CBLs and HBLs on the Diversity of Fecal Microbiota

Comparative analysis revealed statistically significant differences in alpha-diversity indices (Chao1, ACE, Shannon, and Simpson; p < 0.05) between NC and MC groups (Figure 5a). Notably, low-dose CBLs failed to prevent the reduction in Chao1 and Simpson indices, whereas high-dose CBLs exhibited a significant protective effect on all four alpha diversity indices. Notably, unlike CBLs, high-dose HBLs markedly increased the Shannon and Simpson diversity indices (p < 0.05), with no significant changes observed in Chao1 or ACE indices (p > 0.05). Significant differences in beta diversity were detected between the MC and NC groups (p < 0.05), reflecting the impact of constipation on gut microbiota composition (Figure 5b). Although HBLs were administered, the microbial profiles remained unevenly distributed and the original structure of the fecal microbiome was not entirely reestablished. Intriguingly, in contrast to CBL treatments, HBLs intervention was differed from the microbiota of the MC group.

Figure 5.

Effects of CBL and HBL treatment on the gut microbiota in constipated mice. (a) Alpha diversity (Chao1, ACE, Shannon, and Simpson indexes); (b) beta diversity determined using the PCoA method; (c) top ten gut flora microbial taxa at the phylum level; (d) top ten gut flora microbial taxa at the genus level. Results are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). Different small letters indicate that values are significantly different at the p < 0.05 level.

At the phylum level (Figure 5c), elevated abundances of Bacteroidota, Actinobacteriota, Verrucomicrobiota, and Proteobacteria, along with reduced levels of Firmicutes and Desulfobacterota, were observed in the MC group compared to the NC group. An overgrowth of Verrucomicrobiota might contribute to reduced levels of SCFAs [20]. However, both CBLs and HBLs (H-CB and H-HB groups) consistently suppressed Verrucomicrobiota levels while enhancing the abundance of Desulfobacterota. Notably, CBLs (H-B) uniquely restored Actinobacteriota levels to those observed in the NC group, whereas HBLs (H-HB) showed superior therapeutic efficacy compared to the H-CB group in reducing Proteobacteria abundance and promoting Desulfobacterota recovery.

At the genus level (Figure 5d), compared to the NC group, the MC group elevated abundances of Akkermansia, Parabacteroides, and Alistipes, along with reduced levels of Bacteroides and Bifidobacterium. CBLs markedly upregulated the abundance of Bifidobacterium and downregulated the abundance of Akkermansia and Parabacteroides (p < 0.05). In contrast to CBLs, HBLs were associated with a reduction in Alistipes abundance, with the high-dose intervention additionally suppressing Akkermansia levels. These findings highlight distinct modulation patterns between the two interventions, suggesting differential mechanisms on gut microbial restructuring.

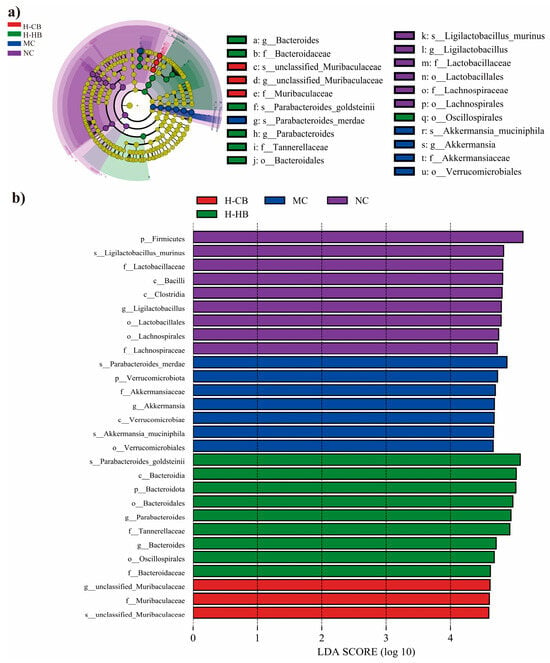

Focusing on specific bacterial taxa, distinct compositional modifications were observed following administration of loperamide, CBLs, and HBLs. Microbial community profiling using LEfSe methodology identified 21 operational taxonomic units (OUTs) exhibiting significant variation (Figure 6). Verrucomicrobiota at the genus level and Parabacteroides_merdae at the species level showed a significant response to the MC group mice. Altered gut microbiota could potentially contribute to the etiology of loperamide-induced constipation. The MC group was characterized by enrichment of Verrucomicrobiota-related taxa, including the genus Akkermansia and its species Akkermansia muciniphila, as well as the species Parabacteroides_merdae. In contrast, the H-HB group showed increased abundance of Bacteroidota/Bacteroidia/Bacteroidales and enrichment of the genera Bacteroides and Parabacteroides, with Parabacteroides_goldsteinii highlighted at the species level. The H-CB group was characterized by enrichment of Muribaculaceae, represented by an unclassified_genus within Muribaculaceae and an unclassified species within Muribaculaceae. The NC group exhibited enrichment of Firmicutes-related taxa and Ligilactobacillus, with Ligilactobacillus_murinus identified as a representative biomarker. Together, these species-level signatures provide additional resolution for understanding BL-associated microbial shifts in the constipation model.

Figure 6.

LEfSe analysis of intestinal microbiota among different mice groups. (a) Taxonomic cladogram obtained from LEfSe analysis. The brightness of each dot is proportional to its effect size. (b) LEfSe identified the most differentially abundant bacterial taxons among groups. Only taxa meeting an LDA significant threshold > 4 were shown (n = 3).

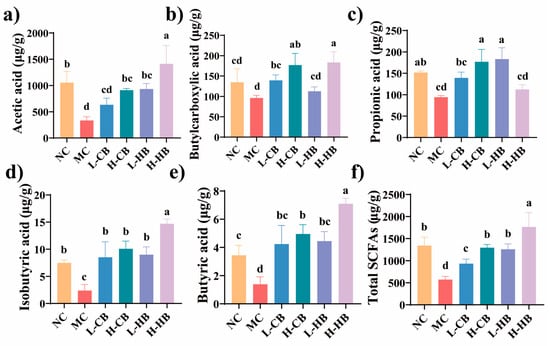

3.7. Effects of CBLs and HBLs on the Production of SCFAs

As illustrated in Figure 7, the amount of SCFAs in the MC group dramatically decreased (p < 0.05). Among SCFAs, acetic, butyric, and propionic acids were predominantly synthesized by gut microbes and made up more than 90% of the total. High-dose HBLs significantly elevated the levels of acetic, butylcarboxylic, isobutyric, and butyric acid compared with the MC group (p < 0.05). However, high-dose CBLs administration effectively enhanced the levels of SCFAs (p < 0.05).

Figure 7.

Effects of CBL and HBL treatments on SCFAs in stool contents (μg g−1). (a) Acetic acid; (b) butylcarboxylic acid; (c) propionic acid; (d) isobutyric acid; (e) butyric acid; (f) total SCFAs. Results are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). SCFA concentrations are reported as μg/g dry feces. Different small letters indicate that values are significantly different at the p < 0.05 level.

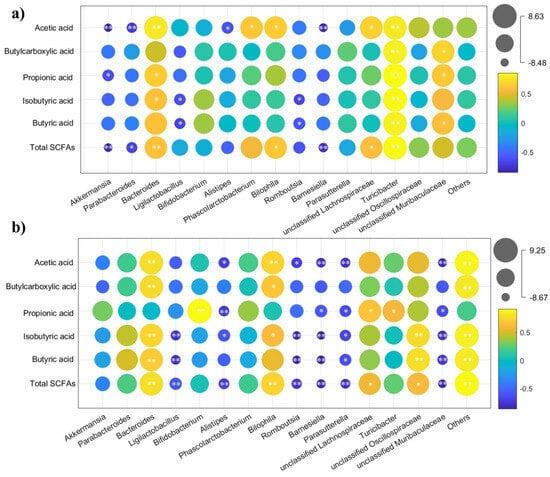

3.8. Relationship Between SCFAs and Microbiota

To investigate whether the prevention effects of CBLs and HBLs against constipation were mediated through alterations in gut microbiota, Spearman’s correlation was used to evaluate the connections between shifts in gut microbes and SCFAs. Following CBLs intervention, a strong positive association between Bacteroides and SCFA levels reached statistical significance (p < 0.05), while Akkermansia and Parabacteroides exhibited inverse correlations with SCFAs (Figure 8a, p < 0.05). However, in the HBL treatment group, Bacteroides maintained a positive correlation with SCFAs, and notable negative associations were observed for Ligilactobacillus and Alistipes (Figure 8b, p < 0.05).

Figure 8.

Heatmap of Spearman’s correlation coefficients between SCFAs and microbiota at genus level. (a) CBL treatment; (b) HBL treatment. The colors range from yellow (positive correlation) to blue (negative correlation), and significant correlations are marked with * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

4. Discussion

Constipation, resulting from a disruption in normal bowel function due to lifestyle factors such as low dietary fiber intake, inadequate hydration, or physical inactivity, is associated with various uncomfortable symptoms and represents a significant global public health challenge [21]. Dietary interventions are increasingly recognized as effective strategies for preventing constipation [22]. BLs have demonstrated various biological activities, including antiulcer, antioxidant, hypolipidemic, antidepressant, and antidiabetic potential [19]. However, their laxative effects and underlying mechanisms remain largely unexplored. Accordingly, two varieties of BLs (CBLs and HBLs) were selected, and their effects on constipation prevention and the underlying mechanisms were systematically investigated. Collectively, 7-day BLs administration effectively prevented loperamide-induced constipation, as evidenced by increased stool amount and weight, improved small intestinal motility, and shortened time to the first black stool. These protective outcomes were accompanied by coordinated changes in gut motility-related neurotransmitters, serotonin-related gene expression, aquaporins, gut microbiota, and SCFAs.

The regulation of neurotransmitters related to gut motility was observed following BL treatment. Evidence from previous studies has highlighted the involvement of enteric nervous system dysfunction in the development of constipation [23]. SS and VIP are inhibitory peptide neurotransmitters, while MTL, SP, and Gas are excitatory peptide neurotransmitters. MTL influences water and electrolyte transport, promotes gastrointestinal peristalsis, and stimulate secretions of hydrochloric acid secretion, pancreatic juices, and bile [24]. SP induces phasic contractions in gastrointestinal smooth muscles via neurokinin receptor activation. Gas is synthesized and secreted by G cells and promotes gastrointestinal motility through RAS-MAP kinase pathway activation [25,26]. Conversely, VIP suppresses gastrointestinal smooth muscle tone, thereby reducing intestinal motility [27]. Similarly, SS binds to its receptors on smooth muscle tissue and inhibits acetylcholine release, ultimately leading to decreased gastrointestinal peristaltic activity [28]. In our study, loperamide decreased serum MTL, SP, and Gas and increased SS and VIP, whereas CBL and HBL supplementation partially reversed these alterations, shifting the overall profile toward the NC group. These findings aligned with previous reports that loperamide disrupts neurotransmitters and impairs gut motility [20,21].

Gut motility enhances 5-HT by activating 5-HT4R receptors, which stimulate neurotransmitter release and promote intestinal contractions [29]. SERT transports 5-HT back into cells after activation, and its levels rise in response to increased 5-HT to prevent overstimulation [30]. Our gene expression data showed that high-dose CBLs markedly increased SERT expression, whereas high-dose HBLs increased 5-HT4R with minimal effect on SERT. These patterns suggest that CBLs may primarily affect 5-HT clearance/homeostatic regulation, while HBLs may preferentially influence 5-HT4R-related signaling. Overall, BLs may modulate serotonin-related pathways. However, the functional effects of BL-induced changes in SERT and 5-HT4R and the direct contribution of SERT/5-HT4R to gut motility still need further verification.

Clone aquaporins, particularly AQP3 and AQP4, play crucial roles in water transport and are potential targets for constipation prevention [31,32]. AQP3 is predominantly found in colonic epithelial cells and is involved in water reabsorption. AQP4 is widely distributed in the colon and gastric fundus and contributes to water and mucus secretion [31]. Compared with the MC group, the NC group exhibited notably higher levels of AQP3 and AQP4. Conversely, BLs attenuated these increases. These findings suggest that BLs may help modulate colonic water transport and thereby contribute to improved fecal hydration.

Gut microbiota dysbiosis disrupts normal bowel movements and intestinal peristalsis in constipation models [22]. BLs exhibited regulatory effects on the gut microbiota of constipated mice, partially restoring microbial diversity and community structure. MC group increased the abundances of Akkermansia, Parabacteroides, and Alistipes but decreased the abundances of Bacteroides. Interestingly, both CBLs and HBLs prevented the constipation-associated shifts by increasing the abundance of Bacteroides and reducing that of Akkermansia. Moreover, CLBs specifically decreased the abundance of Parabacteroides, whereas HLBs significantly lowered the abundance of Alistipes. Bacteroides is a dominant group known for producing acetate, propionate, and succinate and has been reported to decrease in constipated mice [27]. Akkermansia, a mucin-degrading bacterium, may disrupt mucin degradation processes when excessively enriched, leading to impaired intestinal barrier function [33]. Wang et al. reported an increase abundance of Akkermansia increased in constipated mice [34]. Previous studies have shown that Alistipes is associated with the development of intestinal injury and colorectal cancer [35]. Given the small sample size for microbiota sequencing (n = 3 pooled samples per group), these taxonomic findings should be interpreted cautiously and are considered exploratory and supportive. Nevertheless, the direction of microbial changes was consistent with improvements in fecal parameters, intestinal transit, and SCFA profiles.

SCFAs are microbial metabolites generated in the colon and are known to exert various biological effects on gut homeostasis and immune regulation [36]. SCFAs can elevate intestinal osmotic pressure and stimulate intestinal peristalsis [37]. We found that high dose of BLs (both CBLs and HBLs) could enhance the levels of SCFAs. This increase may be related to the enrichment of SCFA-producing taxa such as Bacteroides. Increased levels of SCFAs may directly or indirectly enhance 5-HT secretion, thereby promoting intestinal motility in constipated mice [38]. Furthermore, Ligilactobacillus has been reported to promotes 5-HT transport by increasing SERT expression in intestinal cells [39]. CBLs markedly upregulated the abundance of Bifidobacterium, which may have partially explained the distinct pattern of serotonin-related gene modulation observed in the CBL-treated groups. Correlation analysis further suggested association between Bacteroides and fecal SCFAs levels following treatment with BLs, whereas Akkermansia and Parabacteroides were negatively correlated with SCFAs in the CBL group, and Ligilactobacillus and Alistipes showed negative links in the HBLs group. Although multiple outcomes showed consistent improvements, direct causal links among microbial shifts, SCFA alterations, and neurotransmitter/serotonin-related signaling were not experimentally confirmed.

Potential biochemical differences between CBLs and HBLs may explain their distinct physiological effects. HBLs showed a higher content of dietary fiber and protein, whereas CBLs exhibited higher contents of total phenolics and flavonoids. The higher dietary fiber content in HBLs may provide more fermentable substrates for SCFA production, whereas the higher phenolic and flavonoid contents of CBLs may contribute to differential modulation of specific bacterial taxa and serotonin-related gene expression. Moreover, while BLs showed constipation-preventive effects, the key active ingredients and their specific roles were not elucidated. Future studies are needed to fully understand the causal relationships among microbial shifts, SCFA alterations, and neurotransmitter/serotonin-related signaling. Nevertheless, this study provides preliminary evidence for the preventive potential of different BLs against loperamide-induced constipation. This work lays a foundation for further mechanistic studies and dietary applications.

5. Conclusions

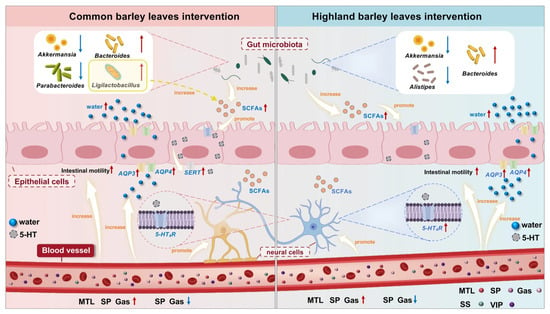

In summary, this study demonstrated that BLs exerted significant constipation-preventive effects in a loperamide-induced mice model, highlighting their potential for intestinal health regulation. The findings indicated that CBLs and HBLs had significant potential in preventing constipation by improving physiological parameters; increasing serum levels of Gas, SP and MTL; decreasing serum levels of SS and VIP; restoring colon AQP3, AQP4, and 5-HT4R mRNA expression; improving fecal SCFAs content; and modulating gut microbiota composition by increasing Bacteroides abundance and reducing that of Akkermansia (Figure 9). Histopathological analyses further supported these findings. CBLs and HBLs also exhibited distinct mechanisms. High-dose CBLs significantly increased SERT expression, whereas HBLs significantly decreased Alistipes abundance and increased SCFA levels. Although this study provides evidence for BLs as promising functional food ingredients for constipation prevention, future research still needs to conduct in-depth exploration in multiple aspects to comprehensively evaluate its safety and efficacy and reveal the specific mechanism of its treatment for constipation prevention.

Figure 9.

A summary of possible mechanisms of CBLs and HBLs in preventing constipation. Red arrows indicate increases and blue arrows indicate decreases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.X., M.M., Z.S. and H.C.; Methodology, Y.X., Z.W., M.M., Z.S. and H.C.; Software, Y.X., Z.W. and M.M.; Validation, Z.W.; Formal analysis, Y.X., Z.W., M.M., Z.S. and H.C.; Investigation, Y.X., Z.W. and M.M.; Resources, M.M. and Z.S.; Data curation, Y.X.; Writing—original draft, Y.X. and Z.W.; Writing—review & editing, Y.X., M.L.C., M.M., Z.S. and H.C.; Visualization, Y.X., Z.W. and M.L.C.; Supervision, M.M., Z.S. and H.C.; Project administration, Z.S.; Funding acquisition, Z.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Shanghai Ganya Biotechnology Co., Ltd.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All experimental procedures were strictly approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Shanghai Jiao Tong University (No. A2023227-001, approved on 25 December 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| BL | Barley leaf |

| CBL | Common barley leaf |

| HBL | Hulless barley leaf |

| GI | Gastrointestinal |

| SCFAs | Short-chain fatty acids |

| SP | Substance P |

| MTL | Motilin |

| Gas | Gastrin |

| SS | Somatostatin |

| VIP | Intestinal peptide |

| PCoA | Principal coordinate analysis |

| LEfSe | Linear discriminant analysis effect size |

References

- Sharma, A.; Rao, S. Constipation: Pathophysiology and current therapeutic approaches. Gastrointest. Pharmacol. 2016, 239, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vriesman, M.H.; Koppen, I.J.; Camilleri, M.; Di Lorenzo, C.; Benninga, M.A. Management of functional constipation in children and adults. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 17, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Fang, C.; Liu, Y.; Gao, M.; Zhang, D.; Shi, G.; Yin, Z.; Zheng, R.; Zhang, J. Comparative study of the laxative effects of konjac oligosaccharides and konjac glucomannan on loperamide-induced constipation in rats. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 7709–7717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, E.D.; Kim, H.M.; Schoenfeld, P. Efficacy and tolerability of guanylate cyclase-C agonists for irritable bowel syndrome with constipation and chronic idiopathic constipation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 113, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasior, A.; Reck, C.; Vilanova-Sanchez, A.; Diefenbach, K.A.; Yacob, D.; Lu, P.; Vaz, K.; Di Lorenzo, C.; Levitt, M.A.; Wood, R.J. Surgical management of functional constipation: An intermediate report of a new approach using a laparoscopic sigmoid resection combined with malone appendicostomy. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2018, 53, 1160–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taketa, S.; Kikuchi, S.; Awayama, T.; Yamamoto, S.; Ichii, M.; Kawasaki, S. Monophyletic origin of naked barley inferred from molecular analyses of a marker closely linked to the naked caryopsis gene (nud). Theor. Appl. Genet. 2004, 108, 1236–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panthi, M.; Subba, R.K.; Raut, B.; Khanal, D.P.; Koirala, N. Bioactivity evaluations of leaf extract fractions from young barley grass and correlation with their phytochemical profiles. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2020, 20, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhang, C.; Xu, Y.; Ma, M.; Yao, T.; Sui, Z. Impact of six extraction methods on molecular composition and antioxidant activity of polysaccharides from young hulless barley leaves. Foods 2023, 12, 3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Pu, X.; Yang, J.; Du, J.; Yang, X.; Li, X.; Li, L.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, T. Preventive and therapeutic role of functional ingredients of barley grass for chronic diseases in human beings. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 12, 3232080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Hua, W.; Xu, H.; Corke, H.; Huang, W.; Sui, Z. Alkaline extracted purified polysaccharide from hulless barley grass and its proliferation inhibitory effect against cancer cells. Starch-Stärke 2024, 76, 2200137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.K.; Chen, T.T.; Li, L.Q.; Liu, F.; Liu, X.; Li, L. The anti-hyperlipidemic effect and underlying mechanisms of barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) grass polysaccharides in mice induced by a high-fat diet. Food Funct. 2023, 14, 7066–7081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeguchi, M.; Ariura, Y.; Takagaki, K.; Ishibashi, Y.; Inagawa, A.; Sugawa, Y. Effects of young barley leaf powder on fecal weight and fecal microflora in healthy women. J. Jpn. Assoc. Diet. Fiber Res. 2004, 8, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeguchi, M.; Tsubata, M.; Takano, A.; Kamiya, T.; Takagaki, K.; Ito, H.; Sugawa-Katayama, Y.; Tsuji, H. Effects of young barley leaf powder on gastrointestinal functions in rats and its efficacy-related physicochemical properties. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 1, 974840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paśko, P.; Bartoń, H.; Zagrodzki, P.; Gorinstein, S.; Fołta, M.; Zachwieja, Z. Anthocyanins, total polyphenols and antioxidant activity in amaranth and quinoa seeds and sprouts during their growth. Food Chem. 2009, 115, 994–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcó, A.; Rubio, R.; Compañó, R.; Casals, I. Comparison of the Kjeldahl method and a combustion method for total nitrogen determination in animal feed. Talanta 2002, 57, 1019–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AOAC International. Official Methods of Analysis, 20th ed.; Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, S.; Yang, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, L. Active phase prebiotic feeding alters gut microbiota, induces weight-independent alleviation of hepatic steatosis and serum cholesterol in high-fat diet-fed mice. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 448–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y.; Ma, S.; Liu, J.; Wang, X. A systematic review of highland barley: Ingredients, health functions and applications. Grain Oil Sci. Technol. 2022, 5, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Hu, C.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, H. Characteristics of three typical Chinese highland barley varieties: Phenolic compounds and antioxidant activities. J. Food Biochem. 2018, 42, 12488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Guo, R.; Sun, X.; Kou, Y.; Ma, X.; Chen, Y.; Song, L.; Yuan, C.; Wu, Y. Xylooligosaccharides from corn cobs alleviate loperamide-induced constipation in mice via modulation of gut microbiota and SCFA metabolism. Food Funct. 2023, 14, 8734–8746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Yang, W.; Li, S.; Liu, S.; Yang, W.; Song, S.; Sheng, J.; Zhao, Y.; Tian, Y. Moringa oleifera leaf alleviates functional constipation via regulating the gut microbiota and the enteric nervous system in mice. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1315402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Tuck, C.; Gibson, P.R.; Chey, W.D. The role of food in the treatment of bowel disorders: Focus on irritable bowel syndrome and functional constipation. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 117, 947–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Guo, H.; Sun, M.; Jiang, C.; Jiang, S.; Mu, G.; Tuo, Y.; Gao, P. Milk fermented by combined starter cultures comprising three Lactobacillus strains exerts an alleviating effect on loperamide-induced constipation in BALB/c mice. Food Funct. 2023, 14, 5264–5276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soudah, H.C.; Hasler, W.L.; Owyang, C. Effect of octreotide on intestinal motility and bacterial overgrowth in scleroderma. N. Engl. J. Med. 1991, 325, 1461–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iijima, K.; Koike, T.; Abe, Y.; Shimosegawa, T. Cutoff serum pepsinogen values for predicting gastric acid secretion status. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2014, 232, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koppen, I.J.N.; van Wassenaer, E.A.; Barendsen, R.W.; Brand, P.L.; Benninga, M.A. Adherence to polyethylene glycol treatment in children with functional constipation is associated with parental illness perceptions, satisfaction with treatment, and perceived treatment convenience. J. Pediatr. 2018, 199, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, X.; Liu, L.; Gamallat, Y.; Zhang, B.; Xin, Y. Enteromorpha and polysaccharides from Enteromorpha ameliorate loperamide-induced constipation in mice. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 96, 1075–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, S.; Sutcliffe, J.; Ong, S.Y.; Lee, M.; Koh, T.; Wong, S.; Farmer, P.; Peck, C.; Stanton, M.; Keck, J. Substance P and vasoactive intestinal peptide are reduced in right transverse colon in pediatric slow-transit constipation. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2010, 22, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, B.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, S.; Han, S.; Fei, Y.; Ba, F.; Berglund, L.; Li, L.; Yao, M. Prevention of loperamide-induced constipation in mice and alteration of 5-hydroxytryptamine signaling by Ligilactobacillus salivarius Li01. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Qin, X.; Zhou, G.; Wang, C.; Mu, C.; Liu, X.; Zhong, W.; Xu, X.; Wang, B.; Jiang, K.; et al. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG supernatant promotes intestinal mucin production through regulating 5-HT4R and gut microbiota. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 12144–12155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.S.; Ma, T.; Filiz, F.; Verkman, A.; Bastidas, J.A. Colon water transport in transgenic mice lacking aquaporin-4 water channels. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2000, 279, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laforenza, U. Water channel proteins in the gastrointestinal tract. Mol. Asp. Med. 2012, 33, 642–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portune, K.J.; Benítez-Páez, A.; Del Pulgar, E.M.G.; Cerrudo, V.; Sanz, Y. Gut microbiota, diet, and obesity-related disorders—The good, the bad, and the future challenges. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 61, 1600252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Yang, S.; Sun, S.; Si, Q.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, G.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W. Lactobacillus rhamnosus strains relieve loperamide-induced constipation via different pathways independent of short-chain fatty acids. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, B.J.; Wearsch, P.A.; Veloo, A.C.; Rodriguez-Palacios, A. The genus Alistipes: Gut bacteria with emerging implications to inflammation, cancer, and mental health. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.G.; Lee, J.; Lee, A.R.; Jo, S.V.; Park, C.H.; Han, D.S.; Eun, C.S. Impact of short-chain fatty acid supplementation on gut inflammation and microbiota composition in a murine colitis model. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2022, 101, 108926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, T.; Wang, X.; Dong, X.; Wang, C.; Wang, L.; Yang, X.; Li, T. Broccoli-derived exosome-like nanoparticles alleviate loperamide-induced constipation, in correlation with regulation on gut microbiota and tryptophan metabolism. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 16568–16580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, X.; Shi, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Ji, Z.; Zhou, W.; Chen, S.; Mao, J. Alleviation of loperamide-induced constipation with sticky rice fermented huangjiu by the regulation of serum neurotransmitters and gut microbiota. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2023, 103, 692–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.N.; Feng, L.J.; Wang, B.M.; Jiang, K.; Li, S.; Xu, X.; Wang, W.Q.; Zhao, J.W.; Wang, Y.M. Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium longum supernatants upregulate the serotonin transporter expression in intestinal epithelial cells. Saudi J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 24, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.