Phenotype, Squalene, and Lanosterol Content Variation Patterns During Seed Maturation in Different Leaf-Color Tea Cultivars

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Seed Traits Measurements

2.2.1. Seed Kernel-Related Traits

2.2.2. Oil Content of Dry Kernels

2.3. Analysis of Squalene and Lanosterol Content

2.3.1. Saponification and Unsaponifiable Matter Extraction of Tea Seed Oil

2.3.2. GC-MS Analysis of Squalene and Lanosterol in Tea Seed Oil

2.3.3. Squalene and Lanosterol Identification and Quantification

2.4. Data Analysis and Visualization

3. Results

3.1. Crude Water Content and Dehydration Rate During Maturation

3.2. Dry Kernel Content and Its Rate of Change in Fresh Fruits and Seeds During Maturation

3.3. Oil Content and Its Rate of Change in Dry Kernels During Maturation

3.4. Comprehensive Analysis of Tea Seed Traits During Maturation

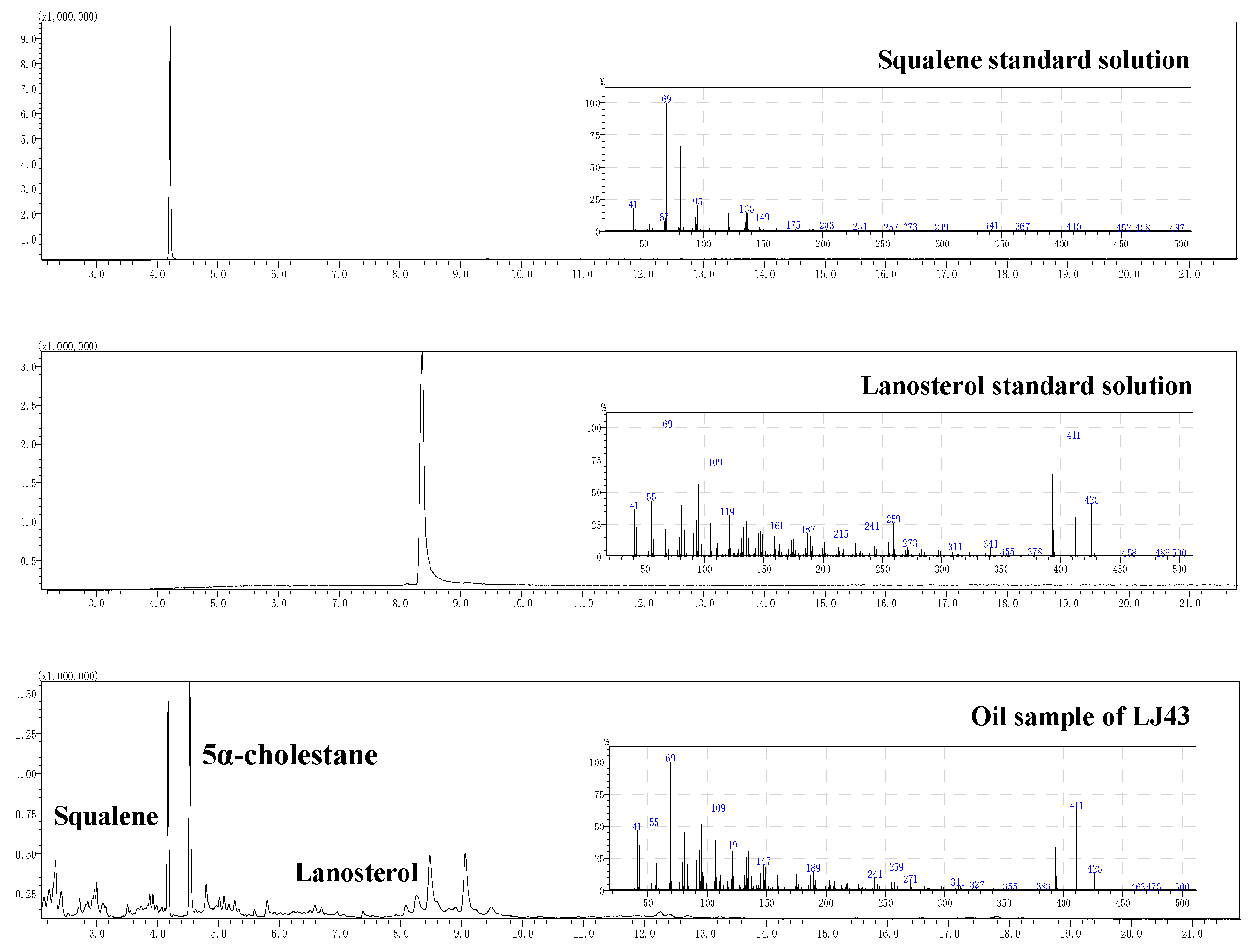

3.5. Identification of Peaks in GC-MS Analysis of Tea Seed Oil Extracts

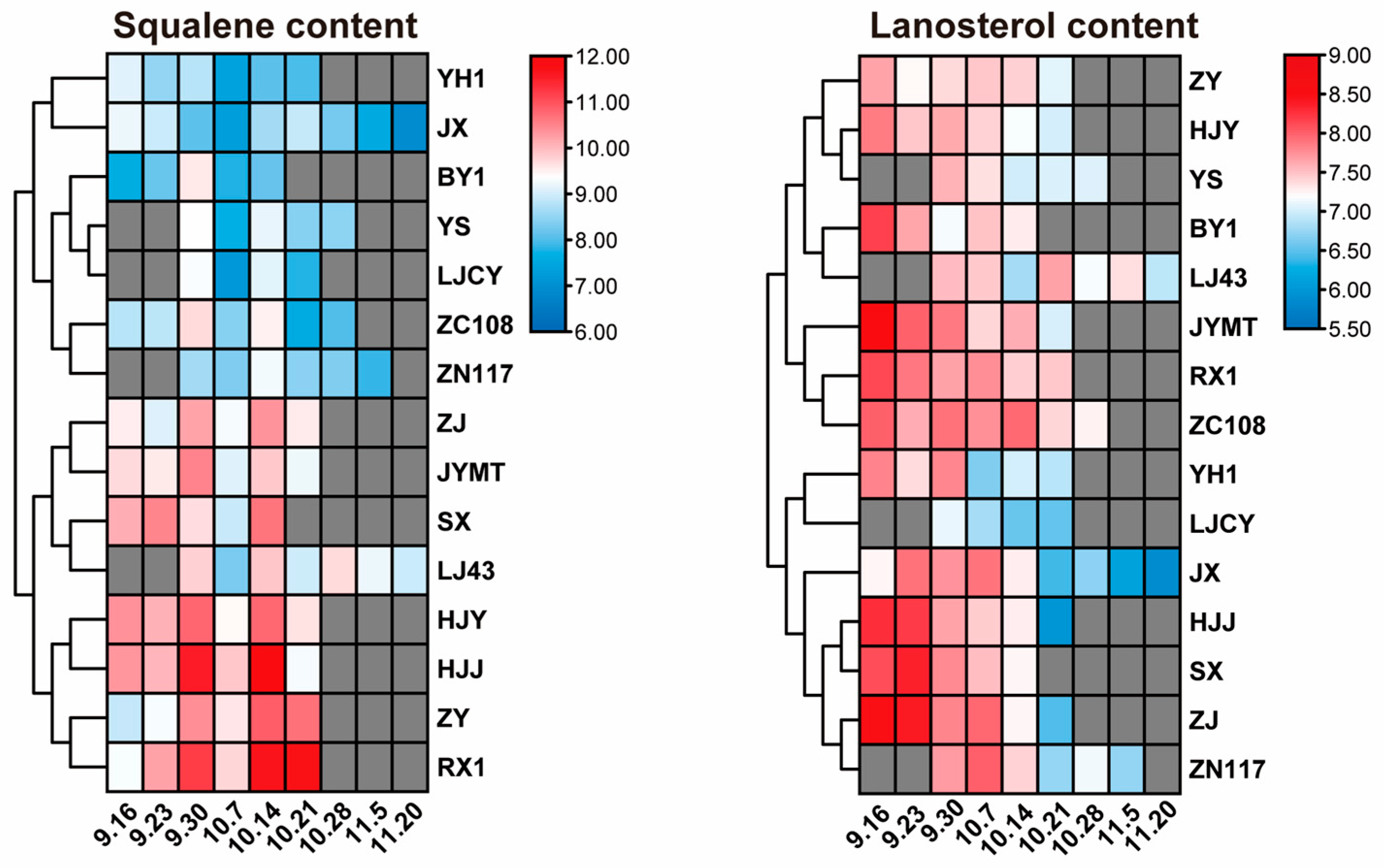

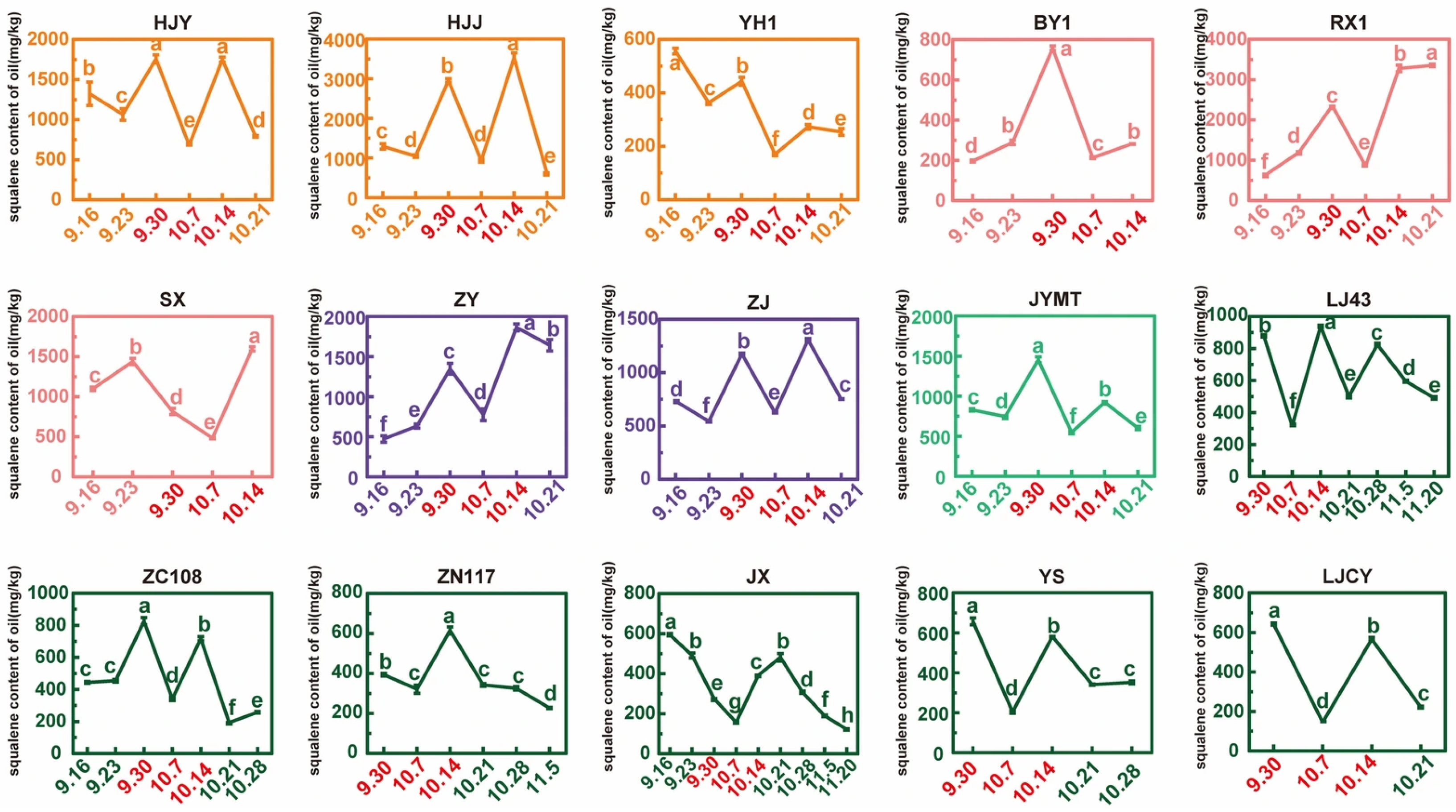

3.6. Squalene Content During Tea Seed Maturation

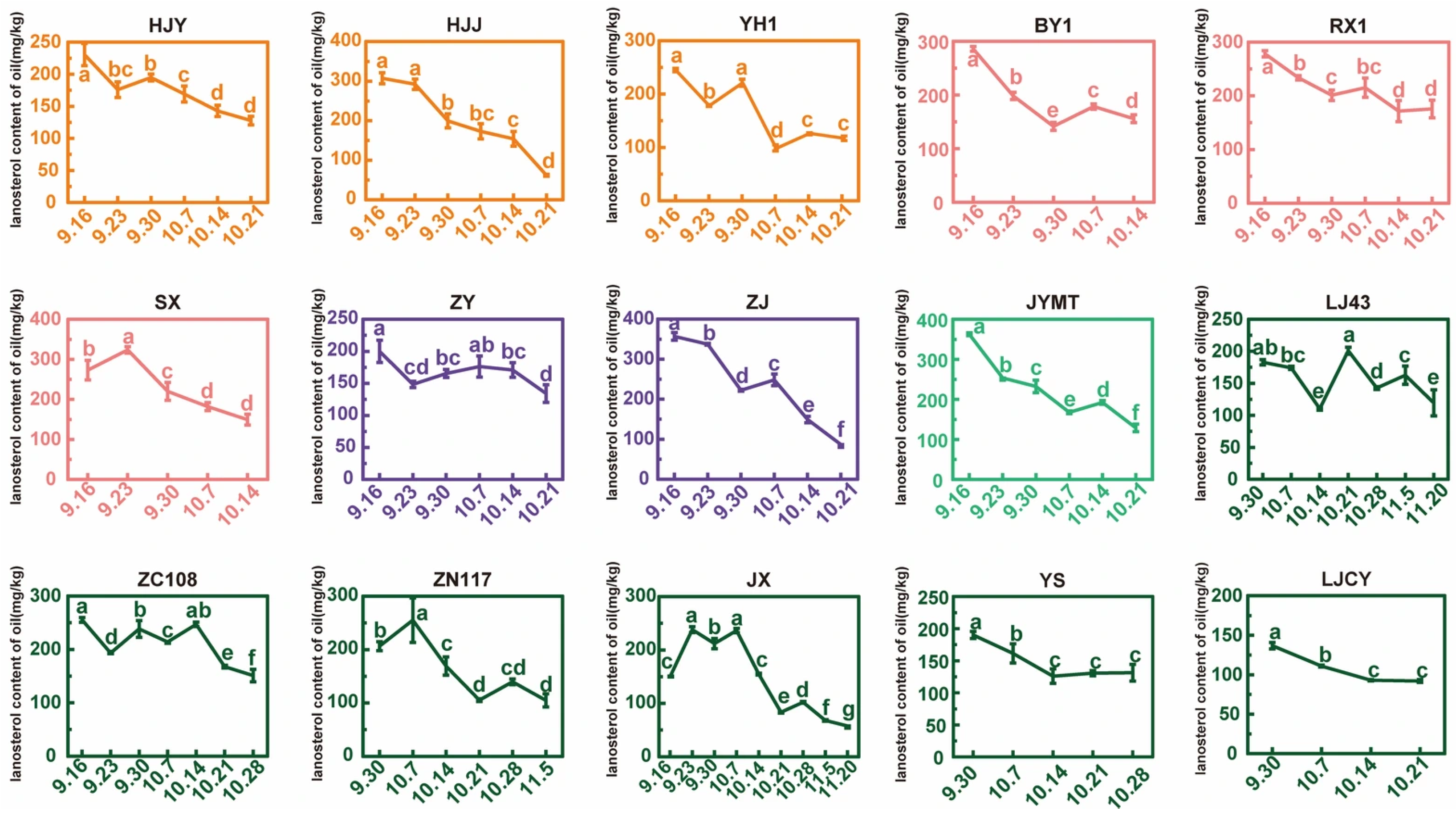

3.7. Lanosterol Content During Tea Seed Maturation

4. Discussion

4.1. Kernel Traits

4.2. Squalene

4.3. Lanosterol

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Szwarc, S.; Le Pogam, P.; Beniddir, M.A. Emerging trends in plant natural products biosynthesis: A chemical perspective. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2024, 82, 102649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Bermudez, J.; Baudrier, L.; Bayraktar, E.C.; Shen, Y.; La, K.; Guarecuco, R.; Yucel, B.; Fiore, D.; Tavora, B.; Freinkman, E.; et al. Squalene accumulation in cholesterol auxotrophic lymphomas prevents oxidative cell death. Nature 2019, 567, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, N.I.; Fairus, S.; Zulfarina, M.S.; Mohamed, I.N. The efficacy of squalene in cardiovascular disease risk-a systematic review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Rámila, S.; Mateos, R.; García-Cordero, J.; Seguido, M.A.; Bravo-Clemente, L.; Sarriá, B. Olive pomace oil versus high oleic sunflower oil and sunflower oil: A comparative study in healthy and cardiovascular risk humans. Foods 2022, 11, 2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.P.; Zheng, Y.; Dai, H.T.; Jia, Y.Y.; Li, C.M. Kinetics of squalene quenching singlet oxygen and the thermal degradation products identification. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 15755–15764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Chen, X.J.; Zhu, J.; Xi, Y.B.; Yang, X.; Hu, L.D.; Ouyang, H.; Patel, S.H.; Jin, X.; Lin, D.N.; et al. Corrigendum: Lanosterol reverses protein aggregation in cataracts. Nature 2015, 526, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araldi, E.; Fernández-Fuertes, M.; Canfrán-Duque, A.; Tang, W.W.; Cline, G.W.; Madrigal-Matute, J.; Pober, J.S.; Lasunción, M.A.; Wu, D.Q.; Fernández-Hernando, C.; et al. Lanosterol modulates TLR4-mediated innate immune responses in macrophages. Cell Rep. 2017, 19, 2743–2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Yang, Z.X.; Tian, X.; Chen, L.; Lee, S.; Huynh, T.; Ge, C.C.; Zhou, R.H. Lanosterol disrupts the aggregation of amyloid-β peptides. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2019, 10, 4051–4060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, R.M.; Hu, Z.X.; Jiang, X.H.; Qi, L.; Pan, Y.H.; Zhao, Y.N. Molecular mechanism of lanosterol binding to αB-crystallin for inhibition of UV-A induced aggregation. Spectrochim. Acta Part A 2025, 343, 126558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Beamonte, R.; Sánchez-Marco, J.; Felices, M.J.; Barranquero, C.; Gascón, S.; Arnal, C.; Burillo, J.C.; Lasheras, R.; Busto, R.; Lasunción, M.A.; et al. Dietary squalene modifies plasma lipoproteins and hepatic cholesterol metabolism in rabbits. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 8141–8153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.Q.; Jiang, Q.; Bao, X.T.; Yang, F.; Li, Y.Y.; Sun, H.H.; Yao, K.; Yin, Y.L. Plant-derived squalene supplementation improves growth performance and alleviates acute oxidative stress-induced growth retardation and intestinal damage in piglets. Anim. Nutr. 2023, 15, 386–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollenberg, A.; Barbarot, S.; Torrelo, A. Basic emollients for xerosis cutis in atopic dermatitis: A review of clinical studies. Int. J. Dermatol. 2025, 64, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.W.; Li, G.Q.; Guan, J.H.; Tang, X.Y.; Qiu, M.; Yang, S.H.; Lu, S.Z.; Fan, X. A comparative metabolomic study of Camellia oleifera fruit under light and temperature stress. CyTA J. Food 2023, 21, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, H.Y.; Bai, S.S.; Chen, C.X.; Bao, Y.Y.; Qu, X.X.; Sun, S.T.; Pan, J.P.; Yang, X.S.; Hou, C.; Deng, Y. Identification of reference genes via real-time quantitative PCR for investigation of the transcriptomic basis of the squalene biosynthesis in different tissues on olives under drought stress. Plant Stress. 2024, 14, 100575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.Y.; Zhao, M.Y.; Yu, K.K.; Zhang, M.T.; Wang, J.M.; Hu, Y.T.; Guo, D.Y.; Wang, K.; Wang, Q.; Cui, J.; et al. Squalene acts as a feedback signaling molecule in facilitating bidirectional communication between tea plants. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eads4888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S.A.; Nagadi, S.A.; Abo-Elyousr, K.A.M.; El-Fawy, M.M. Correction to: Mitigating helminthosporium leaf spot disease in sesame: Evaluating the efficacy of castor essential oil and sodium bicarbonate on disease management and crop yield enhancement. J. Plant Pathol. 2024, 106, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, H.J.; Wang, S.Y.; Civerolo, E.L. Lipid composition of citrus leaves from plants resistant and susceptible to citrus bacterial canker. J. Phytopathol. 1992, 135, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.X.; Wang, X.M.; Tang, X.Y.; Fang, W.G. Histone deacetylase HDAC3 regulates ergosterol production for oxidative stress tolerance in the entomopathogenic and endophytic fungus Metarhizium robertsii. Msystems 2024, 9, e00953-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsujimoto, M. A highly unsaturated hydrocarbon in shark liver oil. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1916, 8, 889–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Ji, T.T.; Zhang, M.; Fang, B. Recent advances in squalene: Biological activities, sources, extraction, and delivery systems. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 146, 104392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Wu, G.C.; Jin, Q.Z.; Wang, X.G. Detection of camellia oil adulteration using chemometrics based on fatty acids GC fingerprints and phytosterols GC–MS fingerprints. Food Chem. 2021, 352, 129422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.P.; Corke, H. Oil and squalene in Amaranthus grain and leaf. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 7913–7920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martakos, I.; Kostakis, M.; Dasenaki, M.; Pentogennis, M.; Thomaidis, N. Simultaneous determination of pigments, tocopherols, and squalene in greek olive oils: A study of the influence of cultivation and oil-production parameters. Foods 2019, 9, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leow, S.S.; Fairus, S.; Sambanthamurthi, R. Water-soluble palm fruit extract: Composition, biological properties, and molecular mechanisms for health and non-health applications. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 9076–9092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Zhu, F.; Chen, B.L.; Su, E.R.; Chen, Y.Z.; Cao, F.L. Composition, bioactive substances, extraction technologies and the influences on characteristics of Camellia oleifera oil: A review. Food Res. Int. 2022, 156, 111159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.J.; Liu, Y.J.; Wang, X.L.; Bai, J.; Lin, L.Z.; Luo, F.J.; Zhong, H.Y. A comprehensive review of health-benefiting components in rapeseed oil. Nutrients 2023, 15, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, S.Y.; Huang, B.; Wei, T.; Deng, Z.Y.; Li, J.; Wen, Q. Comprehensive evaluation of quality characteristics of four oil-tea camellia species with red flowers and large fruit. Foods 2023, 12, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuenyong, J.; Bennett, C.; Jiamyangyuen, S.; Mahatheeranont, S.; Sookwong, P. Development of a simultaneous normal-phase HPLC analysis of lignans, tocopherols, phytosterols, and squalene in sesame oil samples. Foods 2024, 13, 1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Jin, Q.Z.; Akoh, C.C.; Wang, X.G. Mango kernel fat fractions as potential healthy food ingredients: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 1794–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siger, A.; Antkowiak, W.; Dwiecki, K.; Rokosik, E.; Rudzińska, M. Nutlets of Tilia cordata Mill. and Tilia platyphyllos Scop.—Source of bioactive compounds. Food Chem. 2021, 346, 128888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasquez-Rojas, W.V.; Martin, D.; Miralles, B.; Recio, I.; Fornari, T.; Cano, M.P. Composition of Brazil nut (Bertholletia excels HBK), its beverage and by-products: A healthy food and potential source of ingredients. Foods 2021, 10, 3007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, R.X.; Gao, J.Y.; Yi, J.P.; Liu, P. Could peony seeds oil become a high-quality edible vegetable oil? The nutritional and phytochemistry profiles, extraction, health benefits, safety and value-added-products. Food Res. Int. 2022, 156, 111200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Cheng, Y.Y.; Fang, L.Y.; Yang, A.; Luo, F.J.; Lu, J.; Ren, J.L. Physicochemical properties, profile of volatiles, fatty acids, lipids and concomitants from four Kadsura coccinea seed oils. Food Chem. X 2024, 23, 101765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, W.K.; Wang, H.B.; Lan, Z.Z.; Xu, G.Z.; Ni, Q.X.; Mo, Q.F.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Wang, Y. Selection of moderate refining process for gardenia fruit oil based on SPE-HPLC-UV analysis of phytonutrients. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 222, 119547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.T.; Zhao, S.Q.; Zhou, Y.C.; Li, T.; Zhang, W.M. A comprehensive foodomics analysis of rambutan seed oils: Focusing on the physicochemical parameters, lipid concomitants and lipid profiles. Food Chem. X 2024, 23, 101699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grajzer, M.; Kozlowska, W.; Zalewski, I.; Matkowski, A.; Wiland-Szymanska, J.; Rekos, M.; Prescha, A. Nutraceutical prospects of pumpkin seeds: A study on the lipid fraction composition and oxidative stability across eleven varieties. Foods 2025, 14, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, F.Y.; Dai, T.T.; Guo, L.C.; Wang, C.L.; Li, C.H.; Li, C.H.; Chen, J.; Ren, C.Z. Comparative study of chemical compositions and antioxidant capacities of oils obtained from sixteen oat cultivars in China. Foods 2025, 14, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.X.; Zhang, B.; Deng, D.W.; Bai, X.; Xiao, Y.P.; Ma, B.F. Analysis and separation of unsaponifiable components in tomato seed oil. J. Chin. Cereals Oils 2015, 30, 125–128. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.P.; Jin, X.Y.; Yue, C. Current status of comprehensive utilization of tea seeds. Tea Fujian 2018, 40, 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, J. Study on Influencing Factors of Fatty Acids, Squalene and Lanosterol in Tea Seed Oil. Master’s Thesis, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 2022. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/doi/10.27461/d.cnki.gzjdx.2022.002431 (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- Zhu, J.X.; Zhu, Y.J.; Liu, G.Y.; Zhang, S.K.; Jin, Q.Z. Analysis of lipid concomitants in tea seed oil from 13 provinces. China Oils Fats 2013, 38, 84–88. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.Y.; Wang, X.G.; Jin, Q.Z.; Zhang, H.; Mao, W.D.; Zhu, J.X. Comparative analysis of bioactive components in tea seed oil across different regions. China Oils Fats 2014, 39, 44–47. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.Q.; Zeng, Q.M.; Verardo, V.; del Mar Contreras, M. Fatty acid and sterol composition of tea seed oils: Their comparison by the “FancyTiles” approach. Food Chem. 2017, 233, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, T.; Zhu, M.T.; Zhou, X.Y.; Huo, X.; Long, Y.; Zeng, X.Z.; Chen, Y. 1H NMR combined with PLS for the rapid determination of squalene and sterols in vegetable oils. Food Chem. 2019, 287, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, D.Y.; Chang, Y.X.; Ye, N.X.; Yang, J.F. Study on the variation patterns of major functional components during tea seed maturation. J. Tea Sci. 2013, 33, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.R.; Yan, X.S. Colorful tea plants adorn the mountains and rivers with vibrant hues. J. Zhejiang For. 2022, 3, 24–25. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano, A.; De La Rosa, R.; Sánchez-Ortiz, A.; Cano, J.; Pérez, A.G.; Sanz, C.; Arias-Calderón, R.; Velasco, L.; León, L. Chemical components influencing oxidative stability and sensorial properties of extra virgin olive oil and effect of genotype and location on their expression. LWT 2021, 136, 110257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, B.B.; Tin, H.S.; Mao, C.W.; Tong, X.; Wu, X.H. A comparative study on the characteristics of different types of camellia oils based on triacylglycerol species, bioactive components, volatile compounds, and antioxidant activity. Foods 2024, 13, 2894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Castellón, J.; Olmo-Cunillera, A.; Casadei, E.; Valli, E.; Domínguez-López, I.; Miliarakis, E.; Pérez, M.; Ninot, A.; Romero-Aroca, A.; Bendini, A.; et al. A targeted foodomic approach to assess differences in extra virgin olive oils: Effects of storage, agronomic and technological factors. Food Chem. 2024, 435, 137539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, X.X.; Dai, T.T.; Chen, M.S.; Liang, R.H.; Du, L.Q.; Chen, J.; Liu, C.M. Comparative study of chemical compositions and antioxidant capacities of oils obtained from 15 macadamia (Macadamia integrifolia) cultivars in China. Foods 2021, 10, 1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura-Borrego, M.P.; Ríos-Reina, R.; Puentes-Campos, A.J.; Jiménez-Herrera, B.; Callejón, R.M. Influence of the washing process and the time of fruit harvesting throughout the day on quality and chemosensory profile of organic extra virgin olive oils. Foods 2022, 11, 3004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.X.; Li, C.; Yang, X.R.; Lei, J.D.; Chen, H.X.; Zhang, C.W.; Wang, C.Z. Effect of variety and maturity index on the physicochemical parameters related to virgin olive oil from Wudu (China). Foods 2022, 12, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herchi, W.; Harrabi, S.; Rochut, S.; Boukhchina, S.; Kallel, H.; Pepe, C. Characterization and quantification of the aliphatic hydrocarbon fraction during linseed development (Linum usitatissimum L.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 5832–5836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherif, A.O.; Ben Messaouda, M.; Pellerin, I.; Boukhchina, S.; Kallel, H.; Pepe, C. Screening and profiling of hydrocarbon components and squalene in developing Tunisian cultivars and wild Arachis hypogaea L. Species. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2013, 90, 675–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mišina, I.; Sipeniece, E.; Rudzinska, M.; Grygier, A.; Radzimirska-Graczyk, M.; Kaufmane, E.; Seglina, D.; Lacis, G.; Górnas, P. Associations between oil yield and profile of fatty acids, sterols, squalene, carotenoids, and tocopherols in seed oil of selected Japanese quince genotypes during fruit development. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2020, 122, 1900386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.; Dong, L.; Zhong, S.Y.; Jing, H.S.; Deng, Z.Y.; Wen, Q.; Li, J. Chemical composition of Camellia chekiangoleosa Hu. seeds during ripening and evaluations of seed oils quality. Ind. Crops. Prod. 2022, 177, 114499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Q.B.; Chen, T.; Wang, H.; Zheng, S.H.; Wang, H.Z.; Liang, H.; Zhou, L.J.; Yang, H.Y.; Jiang, X.Y.; Ding, C.B.; et al. Variation of Camellia oleifera fruit traits and nutritional constituents in seed oil during development and post-harvest. Sci. Hortic. 2025, 339, 113903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Wang, Y.J.; Wu, G.C.; Jin, J.; Jin, Q.Z.; Wang, X.G. Chemical and volatile characteristics of olive oils extracted from four varieties grown in southwest of China. Food Res. Int. 2021, 140, 109987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 14488.1-2008; Oilseeds-Determination of Oil Content. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2008.

- Sheng, Y.Y.; Xiang, J.; Wang, K.R.; Li, Z.Y.; Li, K.; Lu, J.L.; Ye, J.H.; Liang, Y.R.; Zheng, X.Q. Extraction of squalene from tea leaves (Camellia sinensis) and its variations with leaf maturity and tea cultivar. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 755514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nsir, H.; Taamalli, A.; Valli, E.; Bendini, A.; Toschi, T.G.; Zarrouk, M. Chemical composition and sensory quality of Tunisian ‘Sayali’ virgin olive oils as affected by fruit ripening: Toward an appropriate harvesting time. J. Americ. Oil Chem. Soc. 2017, 94, 913–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grande-Tovar, C.D.; Johannes, D.O.; Puerta, L.F.; Rodríguez, G.C.; Sacchetti, G.; Paparella, A.; Chaves-López, C. Bioactive micro-constituents of ackee arilli (Blighia sapida K.D. koenig). An. Acad. Bras. Ciênc 2019, 91, e20180140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.J.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.H.; Xia, R. Tbtools: An integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.X.; Ying, J.; Guo, P.; Ling, X.G.; Deng, L.L.; Yi, W.Y.; Jiang, Z.Q.; He, Q.Y. Quality and physiological changes of feed mulberry (Morus spp.) at different maturity stages during low-temperature storage. Feed. Res. 2023, 46, 124–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.H.; Wang, Z.S.; Li, Q.H.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, J.G. Properties and chemical compositions of monovarietal virgin olive oil at different ripening stages: A study on olive cultivation in northwest China. Agron. J. 2023, 115, 2757–2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Yang, Q.Y.; Li, Z.Q.; Su, S.C. Changes in the physical attributes, chemical composition, and their correlation analysis of olive fruits at different maturation stages. J. Nucl. Agric. Sci. 2022, 36, 1089–1099. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado-Osorio, A.; Navajas-Porras, B.; Perez-Burillo, S.; Hinojosa-Nogueira, D.; Toledano-Marín, A.; de la Cueva, S.P.; Paliy, O.; Rufian-Henares, J.A. Cultivar and harvest time of almonds affect their antioxidant and nutritional profile through gut microbiota modifications. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, N.B.; Zarrouk, W.; Carrasco-Pancorbo, A.; Ouni, Y.; Segura-Carretero, A.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, A.; Daoud, D.; Zarrouk, M. Effect of olive ripeness on chemical properties and phenolic composition of chétoui virgin olive oil. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2010, 90, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asghar, Z.; Amin, M.; Ullah, S.; Hassan, H.; Habiba, U.-E.; Razzaq, K.; Rajwana, I.A.; Akhtar, G.; Faried, H.N.; Aiyub, M.; et al. Antioxidative enzymes, phytochemicals and proximate components in jujube fruit (Ziziphus mauritiana L.) with respect to genotypes and harvest maturity. Food Biosci. 2024, 60, 104504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oballim, G.; Opile, W.R.; Ochuodho, J.O. Phytic acid, protein, and oil contents and their relationship with seed quality during seed maturation of bambara nut (Vigna Subterranea (L.) Verdc.) landraces. Legume Sci. 2024, 6, e222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Ahrends, A.; He, J.; Gui, H.; Xu, J.; Mortimer, P.E. An evaluation of the factors influencing seed oil production in Camellia reticulata L. plants. Ind. Crops Prod. 2013, 50, 797–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferfuia, C.; Fantin, N.; Piani, B.; Zuliani, F.; Baldini, M. Seed growth and oil accumulation in two different varieties of industrial hemp (Cannabis sativa L.). Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 216, 118723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhshandeh, E.; Abdellaoui, R.; Sanehkoori, F.H.; Ghorbani, H.; Mirzaaghpour, N. Optimizing seed physiological maturity and quality in camelina through plant density variation: A nonlinear regression approach. Agric. Res. 2024, 13, 704–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.T.; Zhu, Q.F.; Xia, C.H. Main chemical components of tea fruit and their variation patterns during maturation. J. Tea Sci. 1990, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.M.; Wu, G.R.; Zhao, B.T.; Wang, H.; Luo, B.X. Study on the accumulation of crude fat and crude saponins in tea fruit. J. Nanjing Norm. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 1992, 15, 82–85. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Z.L. Transcriptome Analysis of Tea Seeds at Different Developmental Stages and Its Association with Fatty Acid Metabolism-Related Genes. Master’s Thesis, Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, Fuzhou, China, 2020. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/doi/10.27018/d.cnki.gfjnu.2020.000379 (accessed on 1 June 2020).

- Gu, P.; Gu, X.T.; Ma, J.W.; Fan, J.S.; Zhang, B.Y.; Lu, Y.Z.; Li, L.L. Dynamics of oil accumulation during fruit development in oil-use maple (Acer truncatum). J. Northwest AF Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2022, 50, 57–67+77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.Y. Accumulation and dynamics of storage reserves during peanut (Arachis hypogaea) fruit development. J. Shandong Agric. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 1990, 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, J.; Liang, Y.R.; Zhao, D.; Wang, K.R.; Lu, J.L.; Yuan, M.A.; Zheng, X.Q. Variation analysis of oil content in tea seed kernels and fatty acid composition in tea seed oil across different cultivars and regions. J. Tea Sci. 2022, 42, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, N.X.; Chang, Y.X.; Zheng, D.Y.; Sun, W.M. Characteristics, functional components, and utilization of tea (Camellia sinensis) fruit. Acta Tea Sin. 2011, 2, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.C.; Chen, R.B.; Xiao, L.P. Preliminary study on reproductive characteristics and fertility among different tea biogeographic groups and populations (part VI): Observations on fruiting capacity and fruit development patterns. Acta Tea Sin. 1983, 4, 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- Si, Y.Y.; Lu, Y.F.; Bai, Q.; Sun, Y.J.; Su, S.C. The combination of high-light efficiency pruning and mulching improves fruit quality and uneven maturation at harvest in Camellia oleifera. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D. Survey of Fruiting Ability Among Tea Varietals and Supercritical Extraction of Tea (Camellia sinensis L.) Seed Oil. Master’s Thesis, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 2012. (accessed on 1 March 2012). [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán, G.; Bucheli, M.E.; Aguilera, M.P.; Belaj, A.; Jimenez, A. Squalene in virgin olive oil: Screening of variability in olive cultivars. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2016, 118, 1250–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuberoso, C.I.G.; Kowalczyk, A.; Sarritzu, E.; Cabras, P. Determination of antioxidant compounds and antioxidant activity in commercial oilseeds for food use. Food Chem. 2007, 103, 1494–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Mansour, A.; Flamini, G.; Ben Selma, Z.; Le Dréau, Y.; Artaud, J.; Abdelhedi, R.; Bouaziz, M. Olive oil quality is strongly affected by cultivar, maturity index and fruit part: Chemometrical analysis of volatiles, fatty acids, squalene and quality parameters from whole fruit, pulp and seed oils of two Tunisian olive cultivars. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2015, 117, 976–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J.; Yu, L.; Zhao, A.N.; Karrar, E.; Zhang, H.; Jin, Q.Z.; Wu, G.C.; Yang, X.Y.; Chen, L.; Wang, X.G. Quality characteristics and antioxidant activity during fruit ripening of three monovarietal olive oils cultivated in China. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2021, 98, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliora, A.C.; Artemiou, A.; Giogios, I.; Kalogeropoulos, N. The impact of fruit maturation on bioactive microconstituents, inhibition of serum oxidation and inflammatory markers in stimulated PBMCs and sensory characteristics of Koroneiki virgin olive oils from Messenia, Greece. Food Funct. 2013, 4, 1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.J.; Mo, R.H.; Zhong, D.L.; Tang, F.B. Dynamic changes of lipids and lipophilic bioactives in Torreya grandis fruits during late growth stages. China Oils Fats 2023, 48, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Wang, W.F.; Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Xu, Q.Q.; Qi, S.J.; Lan, D.M.; Wang, Y.H. Typical characterization of commercial camellia oil products using different processing techniques: Triacylglycerol profile, bioactive compounds, oxidative stability, antioxidant activity and volatile compounds. Foods 2022, 11, 3489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuenyong, J.; Limkoey, S.; Phuksuk, C.; Winan, T.; Bennett, C.; Jiamyangyuen, S.; Mahatheeranont, S.; Sookwong, P. Enhancing functional compounds in sesame oil through acid-soaking and microwave-heating of sesame seeds. Foods 2024, 13, 2891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.Q.; Liu, X.D.; Chao, Y.; Wu, Y.Y.; Qiu, S.K.; Lin, B.N.; Liu, R.K.; Tang, R.C.; Wu, S.X.; Xiao, Z.H.; et al. The effect of extraction methods on the components and quality of Camellia oleifera oil: Focusing on the flavor and lipidomics. Food Chem. 2024, 447, 139046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, X.X.; Dai, T.T.; Chen, M.S.; Liang, R.H.; Du, L.Q.; Chen, J.; Liu, C.M. Comparative study on the extraction of macadamia (Macadamia Integrifolia) oil using different processing methods. LWT 2022, 154, 112614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J.; Su, Y.J.; Shehzad, Q.; Yu, L.; Tian, A.L.; Wang, S.H.; Ma, L.K.; Zheng, L.L.; Xu, L.R. Comparative study on quality characteristics of Bischofia polycarpa seed oil by different solvents: Lipid composition, phytochemicals, and antioxidant activity. Food Chem. X 2023, 17, 100588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, W.C.; Fang, E.H.; Wu, Y.F.; Xu, D.M.; Wang, X.Q. Analysis of sterol forms in camellia seed oil and their dynamic changes during refining and storage. Food Sci. 2021, 42, 39–45. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, P.; Liu, Q.; Fang, Z.X.; Sun, P.L. Chemical composition, thermal stability and antioxidant properties of tea seed oils obtained by different extraction methods: Supercritical fluid extraction yields the best oil quality. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2015, 117, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, T.; Zhu, X.C.; Liu, Y.H.; Li, J.K.; Zhong, B.; Li, Y.J.; Zhao, H.Y.; Jiang, C.Y.; Chen, Z.G.; Liu, H.Z. Research on the relationship between olive oil quality and cultivar, growing region, and fruit maturity. J. Chin. Cereals Oils Assoc. 2025, 40, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacometti, J.; Milin, C.; Giacometti, F.; Ciganj, Z. Characterisation of monovarietal olive oils obtained from Croatian cvs. Drobnica and Buza during the ripening period. Foods 2018, 7, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Wang, Z.; Qin, C.; Cao, H.; Kong, L.; Liu, T.; Jiang, S.; Ma, L.; Liu, X.; Ren, W.; et al. Cloning, expression characteristics of farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase gene from Platycodon grandiflorus and functional identification in triterpenoid synthesis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 11429–11437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.J.; Han, Y.X.; He, S.Q.; Cheng, Q.H.; Tong, H.R. Differential metabolic profiles of pigment constituents affecting leaf color in different albino tea resources. Food Chem. 2025, 467, 142290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Y.Y.; Shin, S.; Wang, K.R.; Lu, J.L.; Liang, Y.R. Effect of temperature on the expression of genes related to the accumulation of chlorophylls and carotenoids in albino tea. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2009, 84, 365–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, M.; Pierantozzi, P.; Contreras, C.; Stanzione, V.; Tivani, M.; Mastio, V.; Gentili, L.; Searles, P.; Brizuela, M.; Fernández, F.; et al. Thermal regime and cultivar effects on squalene and sterol contents in olive fruits: Results from a field network in different Argentinian environments. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 303, 111230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazra, A.; Dutta, M.; Dutta, R.; Bhattacharya, E.; Bose, R.; Biswas, S.M. Squalene synthase in plants—Functional intricacy and evolutionary divergence while retaining a core catalytic structure. Plant Gene 2023, 33, 100403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Date | KF | DKF | KS | DKS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 September | 36.37 ± 1.35 a | 9.83 ± 0.36 c | 61.50 ± 7.90 a | 16.62 ± 2.13 e |

| 23 September | 33.19 ± 0.90 a | 10.36 ± 0.28 c | 64.48 ± 4.00 a | 20.13 ± 1.25 d |

| 30 September | 36.14 ± 1.18 a | 14.24 ± 0.46 b | 67.19 ± 1.50 a | 26.47 ± 0.59 c |

| 7 October | 32.91 ± 1.55 a | 14.42 ± 0.68 b | 62.54 ± 1.89 a | 27.40 ± 0.83 bc |

| 14 October | 34.23 ± 2.65 a | 15.47 ± 1.20 ab | 65.11 ± 4.87 a | 29.41 ± 2.20 ab |

| Cultivars | CWC | DKF | DKS | ODK |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HJY | −0.949 ** | 0.931 ** | 0.927 ** | 0.979 ** |

| HJJ | −0.981 ** | 0.976 ** | 0.988 ** | 0.869 ** |

| YH1 | −0.926 ** | 0.967 ** | 0.932 ** | 0.892 ** |

| ZJ | −0.886 ** | 0.853 ** | 0.874 ** | 0.964 ** |

| ZY | −0.974 ** | 0.949 ** | 0.967 ** | 0.796 ** |

| BY1 | −0.955 ** | 0.825 ** | 0.886 ** | 0.768 ** |

| RX1 | −0.937 ** | 0.801 ** | 0.844 ** | 0.930 ** |

| SX | −0.972 ** | 0.965 ** | 0.977 ** | 0.892 ** |

| JYMT | −0.944 ** | 0.848 ** | 0.932 ** | 0.918 ** |

| LJ43 | −0.980 ** | 0.942 ** | 0.973 ** | 0.586 ** |

| ZC108 | −0.937 ** | 0.914 ** | 0.923 ** | 0.965 ** |

| ZN117 | −0.527 * | 0.521 * | 0.589 * | 0.778 ** |

| JX | −0.944 ** | 0.961 ** | 0.960 ** | 0.938 ** |

| YS | −0.861 ** | 0.800 ** | 0.857 ** | 0.705 ** |

| LJCY | −0.766 ** | 0.749 ** | 0.797 ** | 0.866 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ye, J.-J.; Fang, Y.-N.; Lu, X.-Q.; Dong, S.-L.; Liang, Y.-R.; Lu, J.-L.; Wang, K.-R.; Zhang, L.-J.; Zheng, X.-Q. Phenotype, Squalene, and Lanosterol Content Variation Patterns During Seed Maturation in Different Leaf-Color Tea Cultivars. Foods 2026, 15, 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010094

Ye J-J, Fang Y-N, Lu X-Q, Dong S-L, Liang Y-R, Lu J-L, Wang K-R, Zhang L-J, Zheng X-Q. Phenotype, Squalene, and Lanosterol Content Variation Patterns During Seed Maturation in Different Leaf-Color Tea Cultivars. Foods. 2026; 15(1):94. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010094

Chicago/Turabian StyleYe, Jing-Jing, Yu-Ning Fang, Xiao-Quan Lu, Shu-Ling Dong, Yue-Rong Liang, Jian-Liang Lu, Kai-Rong Wang, Long-Jie Zhang, and Xin-Qiang Zheng. 2026. "Phenotype, Squalene, and Lanosterol Content Variation Patterns During Seed Maturation in Different Leaf-Color Tea Cultivars" Foods 15, no. 1: 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010094

APA StyleYe, J.-J., Fang, Y.-N., Lu, X.-Q., Dong, S.-L., Liang, Y.-R., Lu, J.-L., Wang, K.-R., Zhang, L.-J., & Zheng, X.-Q. (2026). Phenotype, Squalene, and Lanosterol Content Variation Patterns During Seed Maturation in Different Leaf-Color Tea Cultivars. Foods, 15(1), 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010094