Abstract

The possibility of obtaining different structural types for gadolinium–europium heterometallic complexes by implementing the “structural type memory” effect is described. A series of seven Eu(III)/Gd(III) compounds with 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetate, having the same composition but belonging to different structural types, was synthesized and structurally characterized. The photoluminescent properties of the obtained compounds were studied. It was shown that compounds crystallizing in the triclinic phase in the P-1 space group exhibit more effective photoluminescence than similar compounds in the monoclinic symmetry with the P21/n space group.

1. Introduction

The targeted search for new materials requires the development of methods and approaches for designing compounds with specified properties. Therefore, the development of molecular and crystal chemical design of compounds with a specified set of properties, potentially capable of serving as components for various types of materials, is the subject of research by many scientific groups [1,2,3,4].

Among lanthanide coordination compounds, carboxylates are one of the most common and studied compounds of 4f metals. For several decades, they have attracted the attention of researchers due to their variety of coordination methods; carboxylates are capable of forming many different structures while maintaining the same composition of the compound [5,6,7,8,9,10]. The high absorption of aromatic carboxylates and the optimal triplet energy level allow for high luminescence intensity and efficiency: up to 100% for terbium complexes [11] and more than 80% for europium complexes [12]. Various coordination modes of carboxylate ions provide coordination compounds differing in the composition of the immediate environment of the central atom due to the coordination of water molecules and/or alcohols, which leads to a change in the emission constants and, as a result, to a change in the luminescence spectrum, its efficiency, and lifetime. The photoluminescence of lanthanide coordination compounds is used in the creation of electroluminescent devices, luminescent thermometers, and optical sensors [13,14,15,16,17].

Despite the successes achieved in the synthesis of highly efficient discrete lanthanide complexes (primarily europium and terbium), the luminescence efficiency for 4f-metal coordination polymers often remains low due to a non-radiative energy transfer mechanism via an intermetallic energy transfer process [18]. Doping of Eu3+ or Tb3+ ions within an optically inert Ln matrix (Y, La, or Gd) can be used to produce highly luminescent materials by spacing out emissive centers to achieve the distance required to reduce intermetallic energy transfer [19].

Such an approach is actively used to create heterometallic Eu/Tb systems whose luminescence depends on temperature and is used to control luminescent thermometers. [20,21,22]. Despite a significant number of works devoted to the production and use of lanthanide emission complexes, the influence of polymorphism and polymorphic transitions of REE carboxylates on spectral characteristics has been very poorly studied in the literature [23,24,25]. Heterometallic systems are most often obtained for isostructural compounds by providing reactions with a certain metal ratio. If the crystal lattices of the two lanthanides differ, it is extremely difficult to obtain single-phase heterometallic systems.

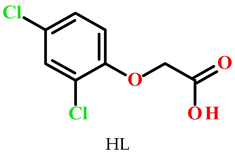

The main goal of this work is to analyze the features of the luminescence of mixed Eu3+ and Gd3+ complexes whose pure europium and gadolinium analogs belong to fundamentally different structures. Throughout the study, we tried to implement two tasks: the first was to study the effect of dilution on the ionic luminescence of europium, and the second was to study the possibility of obtaining heterometallic systems belonging to different structural types of 1D polymers based on Eu(III) and Gd(III) and anions of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (HL), with the general formulae [Ln1yLn22-yL6(DMF)3-s(H2O)s]n·0.5nDMF (labeled as Eu1–Eu4) and [Ln1zLn21-zL3(H2O)2]n·2nDMF·0.25mH2O (labeled as Gd1–Gd3), respectively, by the variation in synthesis conditions.

2. Results

General Characterization of Complexes

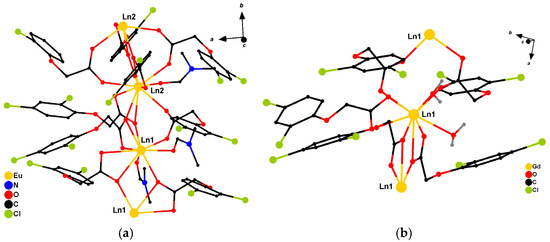

It has been previously shown that 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetates of europium and gadolinium crystallize in different crystal lattices of triclinic (type—Eu; complexes Eu1–Eu4) and monoclinic (type—Gd; complexes Gd1–Gd3) symmetry, respectively (Figure 1) [26,27]. However, given the close radii of the Gd3+ (107.8 Å) and Eu3+ (108.7 Å) cations, it can be expected that using a mixture of Gd3+/Eu3+ will result in the formation of heterometallic systems of both gadolinium and europium structural types. Considering that the central atoms in each of the structural types have different environment, obtaining europium-based heterometallic systems will allow us to evaluate the influence of the coordination polyhedron structure on photoluminescence, which is not achievable for the [Eu2L6(DMF)3]·0.5H2O homometallic complex described earlier.

Figure 1.

(a) Crystalline lattice of Eu-type structure, triclinic phase, space group P-1. (b) Crystalline lattice of Gd-type structure, monoclinic phase, P21/n.

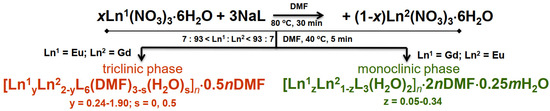

The heterometallic systems Gd1–Gd3 and Eu1–Eu4 were obtained using a general method similar to that previously used to obtain [Eu2L6(DMF)3]·0.5H2O, with the exception of the use of a mixture of gadolinium(III) and europium(III) nitrates in different ratios instead of pure Eu(NO3)3ꞏ6H2O. Current studies revealed that two structural series of complexes are formed during the synthesis of bimetallic carboxylates of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid based on europium(III) and gadolinium(III) (Scheme 1) with the same Eu3+/Gd3+ cation ratio. The key factor determining the structural features of the complexes is the order in which gadolinium and europium salts are added. The resultant complexes belong to the structural type of the metal that is added to the reaction medium first (Eu(NO3)3ꞏ6H2O or Gd(NO3)3ꞏ6H2O). This effect is observed for a wide range of lanthanide salts. The observed phenomenon can be called the structural memory effect. The first structural series is isostructural to the gadolinium(III) complex (complexes Gd1, Gd2, and Gd3), while the other ones (complexes Eu1, Eu2, Eu3, and Eu4) are isostructural to the europium(III) complex.

Scheme 1.

Synthetic route to the target complexes.

The obtained heterometallic systems were characterized by elemental analysis and IR spectroscopy. The Gd3+/Eu3+ ratio was determined by X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (Figure S1). The structural type and phase purity of each compound were determined based on PXRD data (Figures S2–S8). The diffraction data clearly allow compounds Gd1, Gd2, and Gd3 to be classified as belonging to the Gd-structural type, while compounds Eu1, Eu2, Eu3, and Eu4 belong to the europium structural type. It is noteworthy that for the pairs of compounds Gd1 and Eu1; Gd2 and Eu2; Gd3 and Eu3 the Gd/Eu ratio is the same.

The solvate composition and thermal behavior were studied using TGA and DSC data based on two representatives from each series (compounds Gd1 and Eu1). The TGA curve (Figure S9) of Gd1 suggests that there are several mass loss steps, although without a clear plateau. The first observed weight loss of 18% in the region of 70–215 °C (peak at 118 °C) corresponds to the multi-step desolvation process (calculated 18.7%). Desolvation is accompanied by a series of endothermic effects with maxima at 80 °C and 175 °C. The residual framework starts to decompose above 275 °C with a series of complicated weight losses and does not stop until heating ends at 700 °C. For the TGA curve (Figure S10) of Eu1, the weight loss of the lattice DMF and water (12.5%) occurs in the range of 105–215 °C (calculated 12.4%). The process is accompanied by three endothermic effects (minima of temperature around 110 °C, 140 °C, and 175 °C on the DSC curve). The main framework remains intact until it is heated to 255 °C. Further heating of the substances leads to thermal destruction of the complex, accompanied by a series of exothermic effects.

The IR spectra of coordination compounds (Figures S11–S17) show broad bands characteristic of OH bond vibrations at around 3450–3500 cm−1. The amide-1 band characteristic of the DMF molecule is observed at 1634–1660 cm−1. Strong bands attributed to the asymmetric vibrations of the carboxylate anion are found at 1575–1587 cm−1, while symmetric vibrations of the carboxylate anion are observed between 1382 and 1420 cm−1. Each of the valence vibrations is split into two or three bands. The frequency difference Δν = νas − νs = 133–205 cm−1 indicates the chelating coordination mode of the ligand.

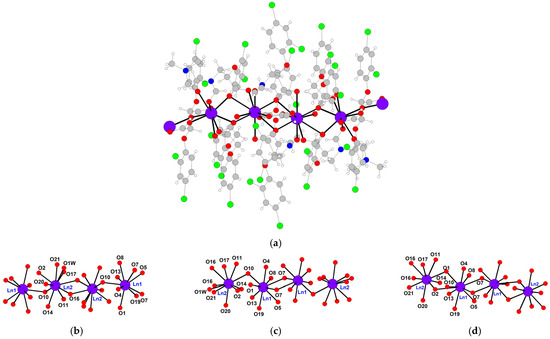

The molecular structure of systems Eu1, Eu2, and Eu4 belonging to the europium structural type was established based on SCXRD data (Table S1 and Figure 2).

Figure 2.

(a) Fragment of 1D-polymeric chain of compound Eu4 along 0b axis. (b–d) Numbering of atoms in the inner sphere of Eu/Gd cations in compounds Eu1 (b), Eu2 (c), and Eu4 (d).

The complexes are polymer chains with alternating dimeric fragments {Ln1Ln2(O2CR)6} linked in a tail-to-head manner, containing two crystallographically independent lanthanide atoms (Figure 2, compound Eu4). In the dimeric fragment Ln1Ln2, the metal atoms are linked by one chelate bridge and two bridge groups. The dimeric fragments are connected by two chelate bridge groups (Ln2Ln2), two bridge groups, and two chelate bridge groups (Ln1Ln1) (the most relevant bonds’ lengths are given in Table 1).

Table 1.

The most relevant bonds’ lengths of complexes Eu1, Eu2, and Eu4.

The geometry of the coordination polyhedrons Ln1O9 and Ln2O9 correspond to a distorted single-cap square antiprism (calculations of the geometry of the polyhedra are given in Table S2) [28]. The coordination node of each of the metal atoms is formed by oxygen atoms of carboxyl groups and DMF molecules. The composition of the coordination spheres of the atoms differs: Ln2 coordinates two DMF molecules, while Ln1 coordinates one. In crystals Eu1 and Eu2, the Ln2 atom coordinates a DMF molecule with occupancy of 0.5, and this position can be occupied by a water molecule with an occupancy of 0.5.

In the chains, C-H…O contacts are observed between the H atoms of the phenyl group/DMF molecules and the O atoms of the carboxylate or hydroxyl groups, and O-H…O bonds between the water molecule and the carboxylate group. In the crystal, interactions between chains are realized through C-H…π, C-Cl…π, C-H…Cl, and Cl…Cl contacts. The main parameters of interatomic contacts are given in Tables S3–S5.

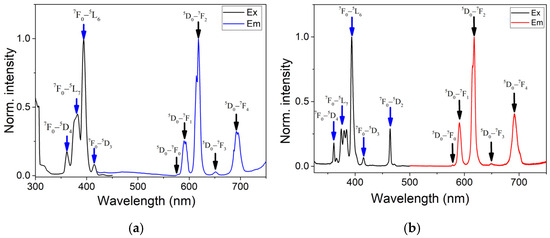

The photoluminescent properties of europium-gadolinium complexes are of interest since they allow the influence of the local environment of the europium ion to be evaluated, which is unattainable in homometallic [Eu2L6(DMF)3]·0.5H2O [20]. In addition, it would be interesting to study the effect of dilution on emissions [29]. All synthesized heterometallic compounds of both structural types upon excitation at 395 nm exhibit typical for Eu(III) cation red emission with CIE chromaticity coordinates (0.65–0.61, 0.32–0.30) characteristic of the europium cation (Figure 3 and Figure S24). The luminescence spectra contain several bands, i.e., at 578 (5D0→7F0 transition of the Eu3+ ion), 591 (5D0→7F1), 618 (5D0→7F2), 648 (5D0→7F3), and 691 nm (5D0→7F4) (Figures S18–S22) [30]. The most intense signal band, assigned to the hypersensitive 5D0→7F2 transition, is split into two Stark components. The observation of weak bands assigned to formally forbidden 5D0→7F0 and 5D0→7F3 transitions, can be explained by local symmetry distortions and J-mixing effects, which relax the selection rules and allow partial intensity borrowing [30,31]. In contrast, the 591 nm peak (5D0→7F1) is a magnetic dipole transition, insensitive to the coordination environment. Attention is drawn to the high intensity of the 5D0→7F4 transition, which accounts for 35–40% of the integral intensity. This phenomenon is usually not typical for coordination compounds of europium with organic ligands and is more typical for inorganic compounds containing Eu3+-centered distorted square antiprism [32,33] and that is in agreement with the geometry of coordination polyhedron determined from structural studies (Table S2).

Figure 3.

Excitation (λem = 617 nm) and emission (λex = 395 nm) spectra of compounds Gd1 (a) and Eu1 (b) in solid state at room temperature.

The most significant differences for representatives of the two series of compounds are observed in quantum yield and luminescence lifetime. The luminescence efficiency of the europium structural type is in the range of 27–46%, while for compounds belonging to the gadolinium structural type, the efficiency is significantly lower, at 5–7.5%. The lifetime of the compounds is described by a monoexponential curve and ranges from 1390 to 1468 μs for representatives of the europium structural type and from 598 to 615 μs for representatives of the gadolinium structural type (Figure S23). The general trend for the Eu-structural type suggests that the quantum yield increasing with a decrease in the europium content reaching maxima at 25:75 molar Gd:Eu ratio, followed by a decrease in efficiency with a further decrease in the europium cation content. A similar relationship is observed for the Gd-structural type, with an overall correction for lower total efficiency (Figure S25).

It should also be noted that as the concentration of europium decreases, the lifetime of the emission increases, apparently as a result of a decrease in concentration quenching.

The most likely reason for the different emission efficiency values may be the different coordination of the europium cation. In compounds of the gadolinium structural type (Gd1–Gd3), the central atom is coordinated by water molecules, which are effective quenchers of lanthanide ion luminescence [34]. Indeed, the calculated rate constants of non-radiative processes are 3–4 times higher than the corresponding value for representatives of the europium structural type. In addition, the efficiency of luminescence can be influenced by the different symmetry of the immediate environment of the Eu3+ cation [35]. To evaluate it, you can use the asymmetry parameter calculated by the formula [36]

For complexes of the europium structural type, this parameter ranges from 3.08 to 3.11, while for compounds of the gadolinium structural type, its values range from 1.98 to 1.75, indicating lower local symmetry of the europium ion in compounds of the Eu-structural type.

The phenomenological Judd–Ofelt parameters of the intensity of Eu3+ electron transitions can be calculated from the emission spectra of the complexes. The Judd parameters were calculated from the luminescence spectra using methods described in the literature [37,38] and are presented in Table 2. It is known that the parameter is sensitive to the local symmetry of the nearest environment of the lanthanide ion, increasing with its decrease. As can be seen from the table, the parameter Ω2, characterizing the probability of the 5D0 →7F2 transition, has fairly high values, and the dynamics of its change correlates with QEu, which indicates the role of low symmetry of the coordination polyhedron in increasing the probability of electron transition between the energy levels of the 4f shell of the europium ion [39].

Table 2.

Photoluminescent parameters for compounds Gd1–Gd3 and Eu1–Eu4.

3. Materials and Methods

All the reagents and solvents were commercially available and used as received without further purification. Elemental analyses of C, H, and N were performed with the EuroEA 3000 analyzer (EuroVector, Milan, Italy). The IR spectra were measured by the FSM 2202 spectrometer (Infraspek, Sankt-Petersburg, Russia) in the range of 4000–400 cm−1. Photoluminescence and excitation spectra were recorded on the Fluorolog FL3-22 spectrometer (HORIBA Scientific, Kyoto, Japan) for the complexes in solid state. Luminescence decays were measured using the same spectrometer equipped a xenon flash lamp (HORIBA Scientific, Kyoto, Japan). The luminescence quantum yields of the solid samples were determined by the absolute method using an integrating sphere (HORIBA Scientific, Kyoto, Japan). The thermal behavior was studied using the simultaneous thermal analysis (STA) technique. RXPD data at room temperature were collected using a SuperMini 200, Rigaku, (Supermini 200, Rigaku, Tokyo, Japan) (CuKα, λ = 1.54 Å).

Synthetic Procedures

The general method for obtaining compounds (Gd1–Gd3): First, 1.05 mmol of sodium 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetate was dissolved in 35 mL of N,N-dimethylformamide with heating and stirring. Gd(NO3)3ꞏ6H2O was added to the resulting solution, and then, after 30 min of stirring, a solution of Eu(NO3)3ꞏ6H2O was added in the required ratio (the total amount of lanthanides was 0.35 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred for 30 min. The resulting solution was left at room temperature for isothermal evaporation of the solvent until a crystalline precipitate formed. The precipitated crystals were filtered off and dried in air.

Compounds Eu1–Eu4 were obtained in a similar manner, except that europium(III) nitrate was added first, followed by gadolinium(III) nitrate.

[Gd0.05Eu0.95L3(H2O)2]∙2DMF∙0.25H2O (Gd1): (Initial Eu3+/Gd3+ molar ratio upon synthesis 93:7). Yield 74%. IR (cm−1): 3368, 1657, 1631, 1587, 1477, 1440, 1418, 1382, 1330, 1286, 1265, 1253, 1233, 1105, 1079, 1046, 937, 919, 872, 837, 799, 717, 675, 646, 608, 557, 460, 443. Anal. calc. (%) for C30H33.5N2Cl6Gd0.05Eu0.95O13.25: C 36.07, H 3.38, N 2.80. Found (%): C 36.45, H 3.03, N 3.01. Molar ratio of Ln ions. Found (%): Eu 94.48, Gd 5.52.

[Gd0.1Eu1.9L6(DMF)2.5(H2O)0.5]∙0.5DMF (Eu1): (Initial Eu3+/Gd3+ molar ratio upon synthesis 93:7). Yield 61%. IR (cm−1): 3469, 1657, 1634, 1614,1576, 1477, 1442, 1420, 1386, 1333, 12291, 1269, 1252, 1235, 1103, 1076, 1046, 930, 914, 882, 871, 862, 838, 805, 784, 725, 715, 700, 677, 666, 646, 612, 584, 557, 464, 443. Anal. calc. (%) for C57H52Cl12Eu1.9Gd0.1N3O21.5: C 36.95, H 2.83, N 2.27. Found (%): C 37.22, H 3.82, N 2.30. Molar ratio of Ln ions. Found (%): Eu 94.72, Gd 5.28.

[Gd0.26Eu0.74L3(H2O)2]∙2DMF∙0.25H2O (Gd2): (Initial Eu3+/Gd3+ molar ratio upon synthesis 70:30). Yield 70%. IR (cm−1): 3471, 1656, 1634, 1575, 1476, 1440, 1420, 1387, 1334, 1286, 1269, 1253, 1234, 1103, 1075, 1046, 942, 929, 863, 839, 803, 715/678, 666, 646, 607, 585, 559, 464, 443. Anal. calc. (%) for C30H33.5N2Cl6Gd0.26Eu0O13.25: C 36.03, H 3.38, N 2.80. Found (%): C 36.38, H 3.12, N 3.31. Molar ratio of Ln ions. Found (%): Eu 73.92, Gd 26.08.

[Gd0.5Eu1.5L6(DMF)2.5(H2O)0.5]∙0.5DMF (Eu2): (Initial Eu3+/Gd3+ molar ratio upon synthesis 70:30). Yield 69%. IR (cm−1): 3469, 1657, 1632, 1583, 1477, 1442, 1419, 1388, 1332, 1288, 1269, 1251, 1233, 1103, 1075, 1046, 929, 877, 861, 839, 806, 784, 715, 678, 666, 645, 610, 583, 559, 464, 443. Anal. calc. (%) for C57H52Cl12Eu1.5Gd0.5N3O21.5: C 36.91, H 2.83, N 2.27. Found (%): C 36.31, H 2.98, N 2.03. Molar ratio of Ln ions. Found (%): Eu 73.81, Gd 26.19.

[Gd0.34Eu0.66L3(H2O)2]∙2DMF∙0.25H2O (Gd3): (Initial Eu3+/Gd3+ molar ratio upon synthesis 60:40). Yield 55%. IR (cm−1): 3395, 1658, 1635, 1575, 1477, 1445, 1419, 1387, 1332, 1284, 1267, 1256, 1232, 1103, 1075, 1044, 931, 865, 839, 803, 770, 715, 678, 666, 646, 607, 583, 556, 465, 443. Anal. calc. (%) for C30H33.5N2Cl6Gd0.34Eu0.66O13.25: C 36.01, H 3.37, N 2.80. Found (%): C 36.51, H 3.19, N 2.94. Molar ratio of Ln ions. Found (%): Eu 64.80, Gd 35.20.

[Gd0.68Eu1.32L6(DMF)2.5(H2O)0.5]∙0.5DMF (Eu3): (Initial Eu3+/Gd3+ molar ratio upon synthesis 60:40). Yield 63%. IR (cm−1): 3488, 1654, 1589, 1476, 1454, 1428, 1386, 1335, 1287, 1267, 1255, 1233, 1103, 1077, 1047, 940, 864, 839, 803, 764, 715, 666, 646, 609, 559, 463, 441. Anal. calc. (%) for C57H52Cl12Eu1.32Gd0.68N3O21.5: C 36.89, H 2.82, N 2.26. Found (%): C 36.39, H 2.46, N 2.04. Molar ratio of Ln ions. Found (%): Eu 65.11, Gd 34.89.

[Gd1.76Eu0.24L6(DMF)3] (Eu4): (Initial Eu3+/Gd3+ molar ratio upon synthesis 7:93). Yield 73%. IR (cm−1): 3449, 1658, 1587, 1476, 1436, 1418, 1382, 1332, 1285, 1265, 1255, 1231, 1104, 1076, 1046, 936, 868, 838, 800, 761, 716, 675, 646, 607, 557, 468, 443. Anal. calc. (%) for C57H51Cl12Eu0.24Gd1.76N3O21: C 37.13, H 2.78, N 2.28. Found (%): C 36.95, H 2.71, N2.27. Molar ratio of Ln ions. Found (%): Eu 11.88, Gd 88.12.

Crystals suitable for X-ray structural analysis were selected from the bulk of the obtained substance Eu1, Eu2, and Eu4. X-ray structural analysis of single crystals selected from the bulk of the synthesized complex was performed on a Bruker D8 Venture diffractometer (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA) equipped with a CCD detector and a monochromatic radiation source (MoKα, λ = 0.71073 Å, graphite monochromator) using standard procedures. A semi-empirical absorption correction was introduced for all structures [40]. The structures were decoded using a direct method and refined in a full-matrix anisotropic approximation for all non-hydrogen atoms. The calculations were performed using SHELX-2018/3 [41] and Olex2 (version 1.3) [42] software. Structures were solved taking into account the disorder of one of the coordination positions at lanthanide atoms Eu1: coordination of the DMF molecule with occupancy p = 0.5 and the water molecule with p = 0.5, which forms an H-bond with the DMF solvate molecule (p = 0.5). When deciphering the structures, the heteronuclearity of the metal atoms was not taken into account; the lanthanide prevailing in the composition of the compound was chosen as the metal center. The coordinates of the atoms, thermal parameters, and a list of all reflections for the studied structures are deposited in the Cambridge Structural Data Bank (No. 2357968 (Eu1), 2357969 (Eu2), and 2465559 (Eu4) can be obtained upon request at deposit@ccdc.cam.ac.uk or http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures) (accessed on 1 November 2025). The geometry of the polyhedra of metal atoms was determined using the SHAPE 2.1 program [28].

4. Conclusions

A heterometal Eu/Gd lanthanide metal–organic frameworks were synthesized with varying Gd concentrations to determine an optimal doping concentration by reducing non-radiative energy transfer pathways. Emission studies suggest that the highest emission intensities were from the 75:25 Eu:Gd. The symmetry features coordination polyhedra to determine the specific relationship between the 5D0→7Fj bands in the europium spectrum, which is confirmed by the structural data and calculated Judd–Ofelt parameters. Moreover, during this study, we proposed a method that makes it possible to obtain heterometallic lanthanide coordination polymers of different structural series and coordination environments of the europium cation with the same molar ratio of lanthanides in the case of non-isostructurality of the initial “pure” polymers. This approach opens up the possibility of additional control over the photophysical characteristics of lanthanide complexes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/inorganics13120397/s1: Table S1. Crystallographic parameters and refinement details for Eu1, Eu2 and Eu4; Table S2. Geometry analysis of the LnO9 polyhedron in Eu1, Eu2 and Eu4 (EP-9 is enneagon, OPY-9 is an octagonal pyramid, HBPY-9 is a heptagonal bipyramid, JTC-9 is Johnson triangular cupola, JCCU-9 is a capped cube, CCU-9 is a spherical-relaxed capped cube, JCSAPR-9 is a capped square antiprism, CSAPR-9 is a spherical capped square antiprism, JTCTPR-9 is a tricapped trigonal prism, TCTPR-9 is a spherical tricapped trigonal prism, JTDIC-9 is a tridiminished icosahedron, HH-9 is a hula-hoop, MFF-9 is a muffin; calculations were performed in the Shape v2.1 program); Table S3. D-H…A (D = O, C; X = O, N, Cl) interactions in the crystal packing of Eu1, Eu2 and Eu4; Table S4. Intra- and intermolecular Y-X…π interactions in the crystal packing of Eu1, Eu2 and Eu4. (Cg(J) is a centroid of benzoic ring J; X..Cg is a distance of X to Cg; X-Perp is a perpendicular distance of H to ring plane J; γ is an angle between Cg-H vector and ring J normal; Y-X..Cg is X-H-Cg angle); Table S5. Parameters of intermolecular Cl…Cl interactions in the crystal packing of Eu1, Eu2 and Eu4.; Figure S1. X-ray fluorescence spectra of Gd1—a; Eu1—b; Gd2—c; Eu2—d; Gd3—e; Eu3—f; Eu4—g; Figure S2. PXRD of compound Gd1. Black line—calculated diffractogram of Gd-type; red line—experiment; Figure S3. PXRD of compound Eu1. Black line—calculated diffractogram of Eu-type; red line—experiment; Figure S4. PXRD of compound Gd2. Black line—calculated diffractogram of Gd-type; red line—experiment; Figure S5. PXRD of compound Eu2. Black line—calculated diffractogram of Eu-type; red line—experiment; Figure S6. PXRD of compound Gd3. Black line—calculated diffractogram of Gd-type; red line—experiment; Figure S7. PXRD of compound Eu3. Black line—calculated diffractogram of Eu-type; red line—experiment; Figure S8. PXRD of compound Eu4; Black line—calculated diffractogram of Eu-type; red line—experiment; Figure S9. TGA curve of complex Gd1; Figure S10. TGA curve of complex Eu1; Figure S11. IR-spectra of complex Gd1; Figure S12. IR-spectra of complex Eu1; Figure S13. IR-spectra of complex Gd2; Figure S14. IR-spectra of complex Eu2; Figure S15. IR-spectra of complex Gd3; Figure S16. IR-spectra of complex Eu3; Figure S17. IR-spectra of complex Eu4; Figure S18. Excitation and emission spectra of complex Gd2; Figure S19. Excitation and emission spectra of complex Eu2; Figure S20. Excitation and emission spectra of complex Gd3; Figure S21. Excitation and emission spectra of complex Eu3; Figure S22. Excitation and emission spectra of complex Eu4; Figure S23. Emission decay kinetics of Gd1—a; Eu1—b; Gd2—c; Eu2—d; Gd3—e; Eu3—f; Eu4—g. Red line—best fit approximation; Figure S24. CIE coordinates of complexes Gd1-Gd3 and Eu1-Eu4; Figure S25. The values of the luminescence quantum yield for complexes Gd1-Gd3 and Eu1-Eu4 with different Eu/Gd ratios.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G.; methodology, I.N., E.B. and M.S.; validation, W.L. and A.G.; formal analysis, O.K. and M.K.; investigation, M.S., I.N., M.K., E.B., O.K. and N.G.; writing—original draft preparation, O.K. and A.G.; writing—review and editing, M.K. and W.L.; supervision, A.G. and W.L.; project administration W.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

N. Gogoleva and M. Kiskin thank the state assignment of the IGIC RAS in the field of fundamental scientific research. This research was performed using the X-ray diffraction equipment of the JRC PMR IGIC RAS. The international cooperation between the authors has been initiated before the start of the Russian–Ukrainian conflict and does not violate the current regulatory prescriptions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Pode, R. Organic light emitting diode devices: An energy efficient solid state lighting for applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 133, 110043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, G.; Lee, K.; Choi, S.; Yoon, H.J. Organometallic and coordinative photoresist materials for EUV lithography and related photolytic mechanisms. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2023, 493, 215307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popy, D.A.; Saparov, B. “This or that”—Light emission from hybrid organic–inorganic vs. coordination Cu(I) halides. J. Mater. Chem. C 2025, 13, 521–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atzori, M.; Sessoli, R. The Second Quantum Revolution: Role and Challenges of Molecular Chemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 11339–11352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janicki, R.; Mondry, A.; Starynowicz, P. Carboxylates of rare earth elements. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2017, 340, 98–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, V.P.; Brandão, P.; Malvestiti, I.; Longo, R.L. Green syntheses of novel luminescent lanthanide compounds based on pentafluorobenzoate. Opt. Mater. 2024, 157, 116158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolot’ko, A.E.; Shmelev, M.A.; Chistyakov, A.S.; Voronina, J.K.; Varaksina, E.A.; Gogoleva, N.V.; Taydakov, I.V.; Sidorov, A.A.; Eremenko, I.L. Luminescence enhancement by mixing carboxylate benzoate–pentafluorobenzoate ligands in polynuclear {Eu2Zn2} and {Tb2Zn2} complexes. Dalton Trans. 2025, 54, 5708–5720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vialtsev, M.B.; Dalinger, A.I.; Latipov, E.V.; Lepnev, L.S.; Kushnir, S.E.; Vatsadze, S.Z.; Utochnikova, V.V. New approach to increase the sensitivity of Tb-Eu-based luminescent thermometer. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020, 22, 25450–25454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, M.-M.; Cui, J.; Zeng, Y.-L.; Ren, N.; Zhang, J.-J. Two novel Sm(III) complexes with different aromatic carboxylic acid ligands: Synthesis, crystal structures, luminescence and thermal properties. Polyhedron 2019, 158, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thi, D.N.; Thi, N.N.; Vu, A.-T.; Tran, T.Q.; Ngoc, T.N.; Xuan, D.L.; Thi, T.T.; Xuan, T.N. Pyridinedicarboxylate-Tb(III) Complex-Based Luminescent Probes for ATP Monitoring. J. Anal. Methods Chem. 2021, 7, 7030158. [Google Scholar]

- Utochnikova, V.V.; Kuzmina, N.P. Photoluminescence of Lanthanide Aromatic Carboxylates. Russ. J. Coord. Chem. 2016, 42, 679–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levina, A.A.; Chistyakov, A.S.; Shmelev, M.A.; Varaksina, E.A.; Voronina, J.K.; Gogoleva, N.V.; Taydakov, I.V.; Sidorov, A.A.; Eremenko, I.L. Effect of combining fluorinated non-fluorinated monocarboxylate anions in lanthanide complexes on structure photoluminescent properties. New J. Chem. 2025, 49, 12959–12970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanzariya, D.B.; Chaudhary, M.Y.; Pal, T.K. Engineering of Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs) for Thermometry. Dalton Trans. 2023, 52, 7383–7404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, W.; Liu, B.; Li, H.; Zheng, S.; Jiao, H.; Xu, L. Fluorescent Eu3+/Tb3+ Metal–Organic Frameworks for Ratiometric Temperature Sensing Regulated by Ligand Energy. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 14322–14332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, H.; Cheng, S.; Zhang, Z.; He, M.; Qian, J.; Li, L. Tailoring Energy Transfer in Mixed Eu/Tb Metal–Organic Frameworks for Ratiometric Temperature Sensing. Molecules 2024, 29, 3914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilmi, R.; Li, X.; Rasbi, N.K.; Zhou, L.; Wong, W.-Y.; Raithby, P.R.; Khan, M.S. Two new red-emitting ternary europium(III) complexes with high photoluminescence quantum yields and exceptional performance in OLED devices. Dalton Trans. 2023, 52, 12885–12891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilmi, R.; Xia, X.; Oliveira, W.F.; Dutra, J.D.L.; Zhou, L.; Wong, W.-Y.; Raithby, P.R.; Khan, M.S. Photo- and electro-luminescence studies of a new nine-coordinate ternary Eu(III) complex. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2026, 472, 116740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Natur, F.; Calvez, G.; Daiguebonne, C.; Guillou, O.; Bernot, K.; Ledoux, J.; Le Pollès Roiland, L.C. Coordination polymers based on heterohexanuclear rare earthcomplexes: Toward independent luminescence brightness and color tuning. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 6720–6730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbuzaru, B.V.; Corma, A.; Rey, F.; Atienzar, P.; Jordá, J.L.; García, H.; Ananias, D.; Carlos, L.D.; Rocha, J. Metal–organic nanoporous structures with anisotropic photoluminescence and magnetic properties and their use as sensors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 1080–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trannoy, V.; Carneiro Neto, A.N.; Brites, C.D.S.; Carlos, L.D.; Serier-Brault, H. Engineering of Mixed Eu3+/Tb3+ Metal-Organic Frameworks Luminescent Thermometers with Tunable Sensitivity. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2021, 9, 2001938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourtellaris, A.; Lafargue-Dit-Hauret, W.; Massuyeau, F.; Latouche, C.; Tasiopoulos, A.J.; Serier-Brault, H. Tuning of Thermometric Performances of Mixed Eu–Tb Metal–Organic Frameworks through Single-Crystal Coordinating Solvent Exchange Reactions. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2022, 10, 2200484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, J.; Brites, C.D.S.; Carlos, L.D. Lanthanide Organic Framework Luminescent Thermometers. Chemistry 2016, 22, 14782–14795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golikova, M.V.; Yapryntsev, A.D.; Jia, Z.; Fatyushina, E.V.; Baranchikov, A.E.; Ivanov, V.K. Synthesis and Physicochemical Properties of Yttrium Subgroup REE Lactates Ln(C3H5O3)3·2H2O (Ln = Y, Tb–Lu). Russ. J. Inorg. Chem. 2023, 68, 1414–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendin, M.; Tsymbarenko, D. 2D-Coordination Polymers Based on Rare-Earth Propionates of Layered Topology Demonstrate Polytypism and Controllable Single-Crystal-to-Single-Crystal Phase Transitions. Cryst. Growth Des. 2020, 20, 3316–3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.A.; Singh-Wilmot, M.A.; Hossack, C.H.; Cahill, C.L.; Ford, R.A.C. Expanding the Library: Twenty New Ln(III) Metal–Organic Frameworks, Including Two Isoreticular Pairs, from Dihaloterephthalic Acid. Cryst. Growth Des. 2024, 24, 7822–7836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusev, A.N.; Konnik, O.V.; Shul’gin, V.F.; Pevzner, N.S.; Kiskin, M.A.; Linert, W. Lanthanum and some lanthanides 2,4-dichlorophenoxyactetates: Structure and luminescent properties. Polyhedron 2024, 249, 116749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiskin, M.A.; Konnik, O.V.; Shul’gin, V.F.; Gusev, A.N. Crystal Structure of Lanthanide Salts with 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic Acid. Russ. J. Coord. Chem. 2024, 50, 476–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llunell, M.; Casanova, D.; Cirera, J.; Alemany, P.; Alvarez, S. SHAPE, version 2.1; SHAPE: Barcelona, Span, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Einkauf, J.D.; Rue, K.L.; Hoeve, H.A.T.; de Lill, D.T. Enhancing luminescence in lanthanide coordination polymers through dilution of emissive centers. J. Lumin. 2018, 197, 412–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binnemans, K. Interpretation of europium(III) spectra. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2016, 295, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bünzli, J.C. On the design of highly luminescent lanthanide complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2015, 293, 19–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettinelli, M.; Speghini, A.; Piccinelli, F.; Neto, A.N.C.; Malta, O.L. Luminescence spectroscopy of Eu3+ in Ca3Sc2Si3O12. J. Lumin. 2011, 131, 1026–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, R.A.S.; Nobre, S.S.; Granadeiro, C.M.; Nogueira, H.I.S.; Carlos, L.D.; Malta, O.L. A theoretical interpretation of the abnormal 5D0→7F4 intensity based on the Eu3+ local coordination in the Na9[EuW10O36]∙14H2O polyoxometalate. J. Lumin. 2006, 121, 561–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savchenko, V.D.; Zhuravlev, K.P.; Tsaryuk, V.I. Judd-Ofelt analysis of dimeric europium carboxylates with gradually changing distortions of the crystal field around Eu3+ ion. J. Lumin. 2024, 276, 120839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loiko, P.A.; Dashkevich, V.I.; Bagaev, S.N.; Orlovich, V.A.; Yasukevich, A.S.; Yumashev, K.V.; Kuleshov, N.V.; Dunina, E.B.; Kornienko, A.A.; Vatnik, S.M.; et al. Spectroscopic and photoluminescence characterization of Eu3+-doped monoclinic KY(WO4)2 crystal. J. Lumin. 2014, 153, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelczarska, A.J.; Stefańska, D.; Watras, A.; Macalik, L.; Szczygieł, I.; Hanuza, J. Structural and Luminescence Behavior of Nanocrystalline Orthophosphate KMeY(PO4)2: Eu3+ (Me = Ca, Sr) Synthesized by Hydrothermal Method. Materials 2022, 15, 1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judd, R. Optical Absorption Intensities of Rare-Earth Ions. Phys. Rev. 1962, 127, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofelt, G.S. Intensities of Crystal Spectra of Rare-Earth Ions. J. Chem. Phys. 1962, 37, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilmi, R.; Wang, J.; Dutra, J.D.L.; Zhou, L.; Wong, W.-Y.; Raithby, P.R.; Khan, M.S. Efficient Red Organic Light Emitting Diodes of Nona Coordinate Europium Tris(β-Diketonato) Complexes Bearing 4′-Phenyl-2,2′:6′,2′′-Terpyridine. Chem. Eur. J. 2023, 29, e202300376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. SHELXT–Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Found. Crystallogr. 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Cryst. Struct. Commun. 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolomanov, O.V.; Bourhis, L.J.; Gildea, R.J.; Howard, J.A.; Puschmann, H. OLEX2: A complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2009, 42, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).