Preliminary Study of the Cytotoxic Activity of Pd(II) and Pt(II) Complexes Bearing P-N ligands Derived from Aminoalcohols

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

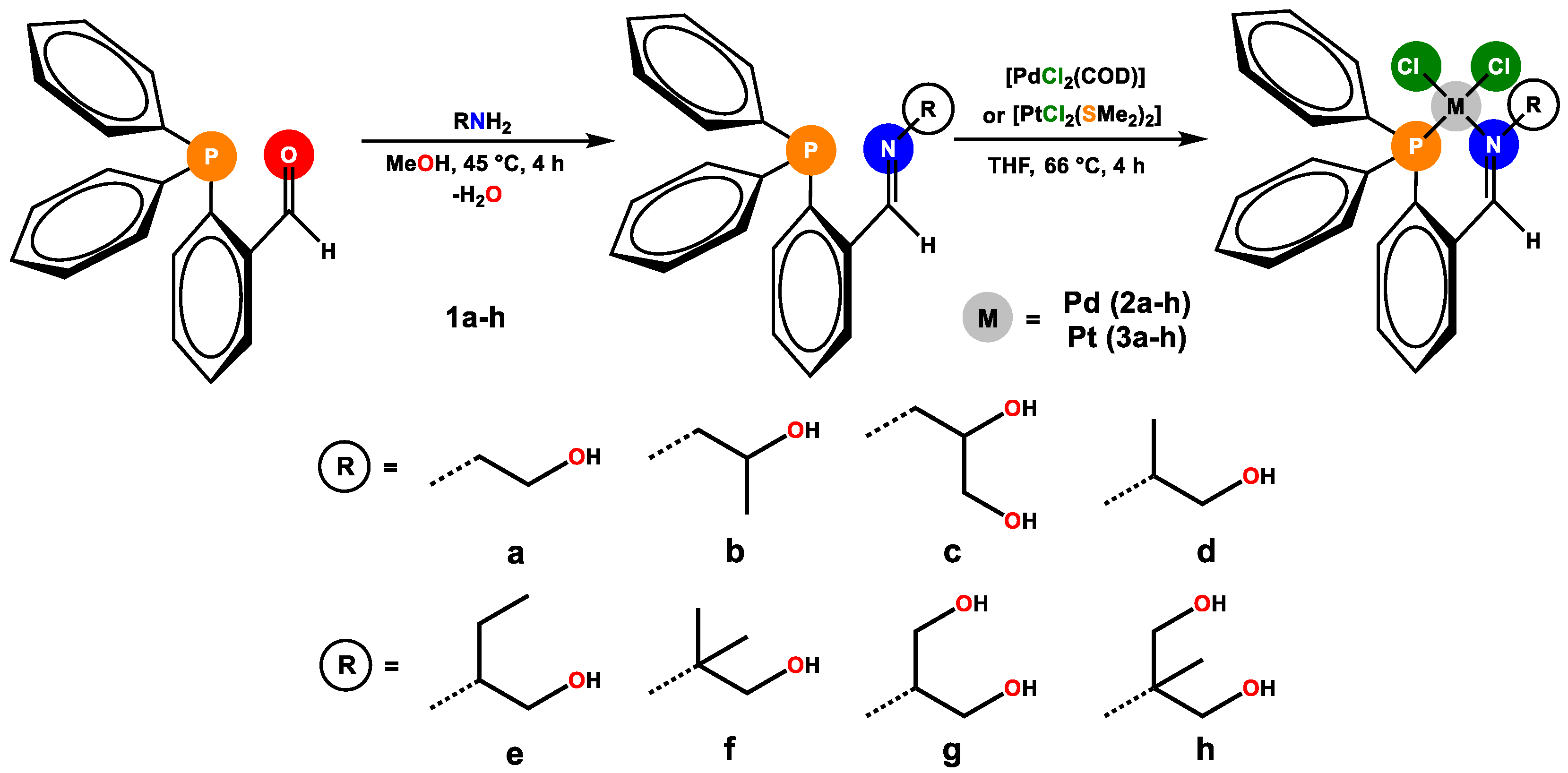

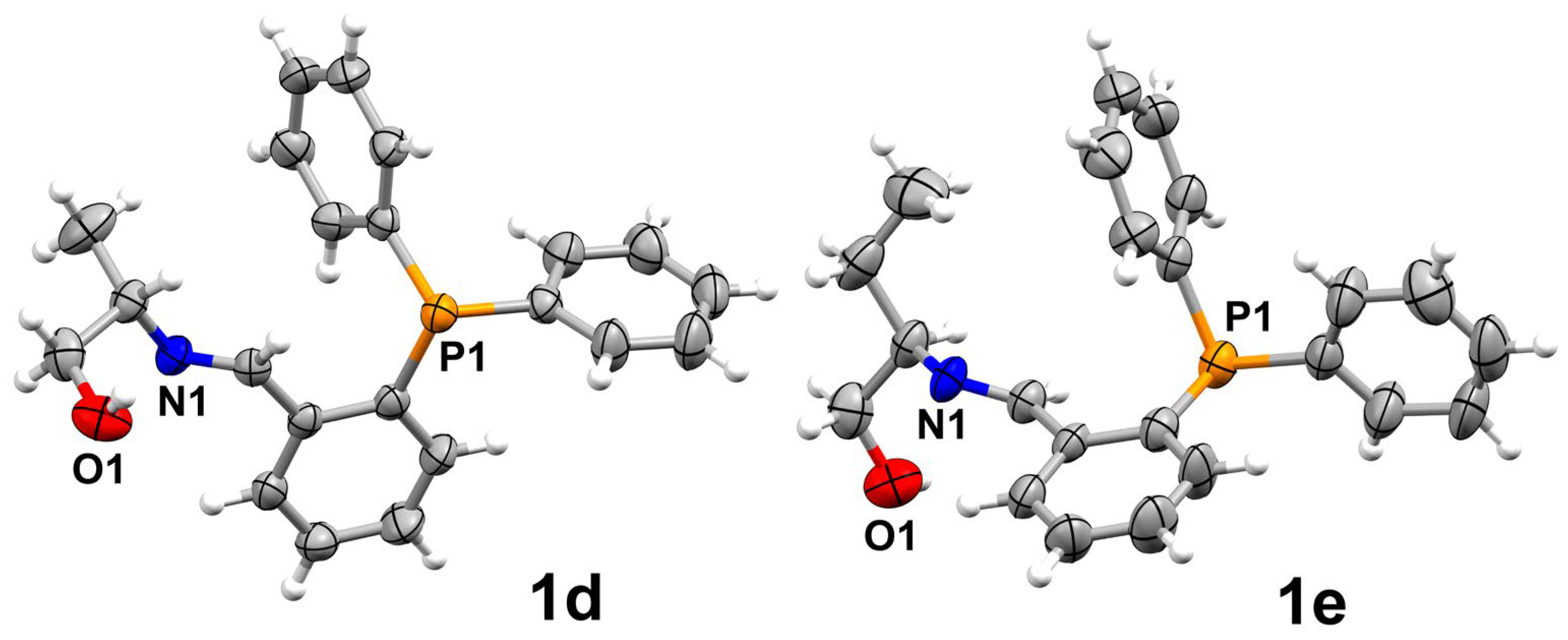

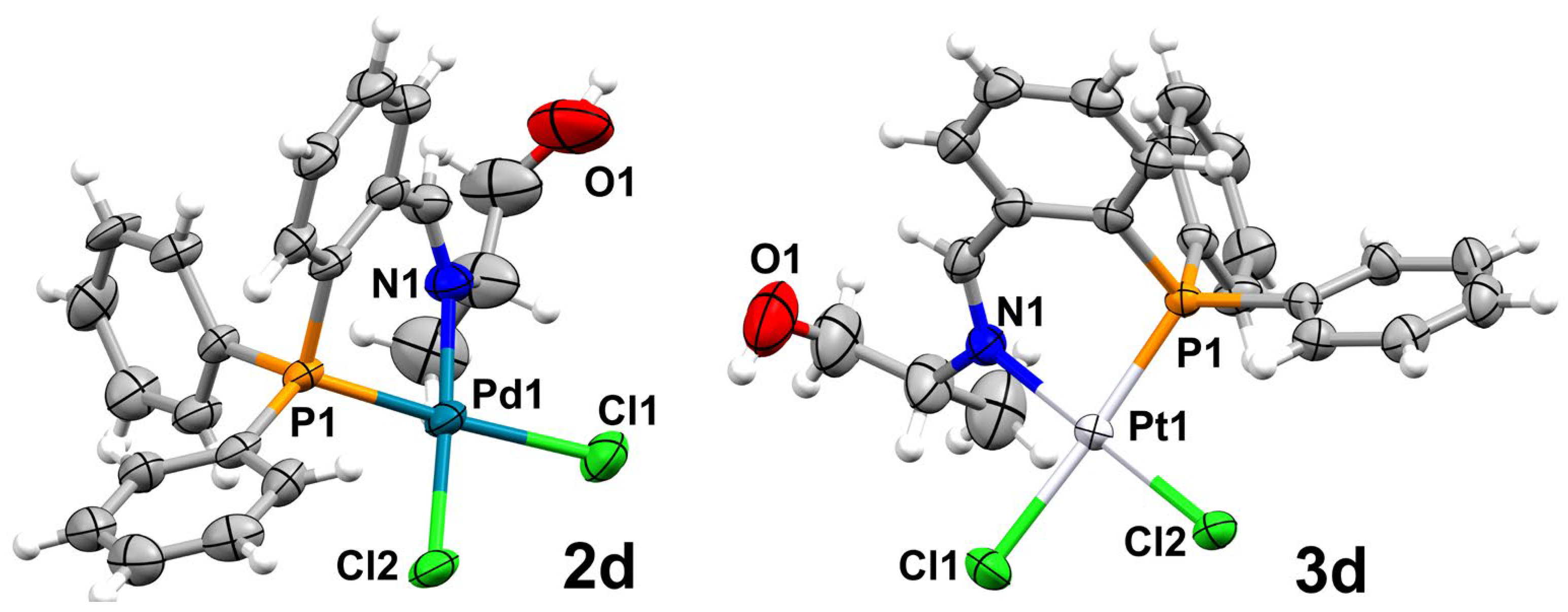

2.1. Synthesis of Pd(II) and Pt(II) Complexes with PN Ligands

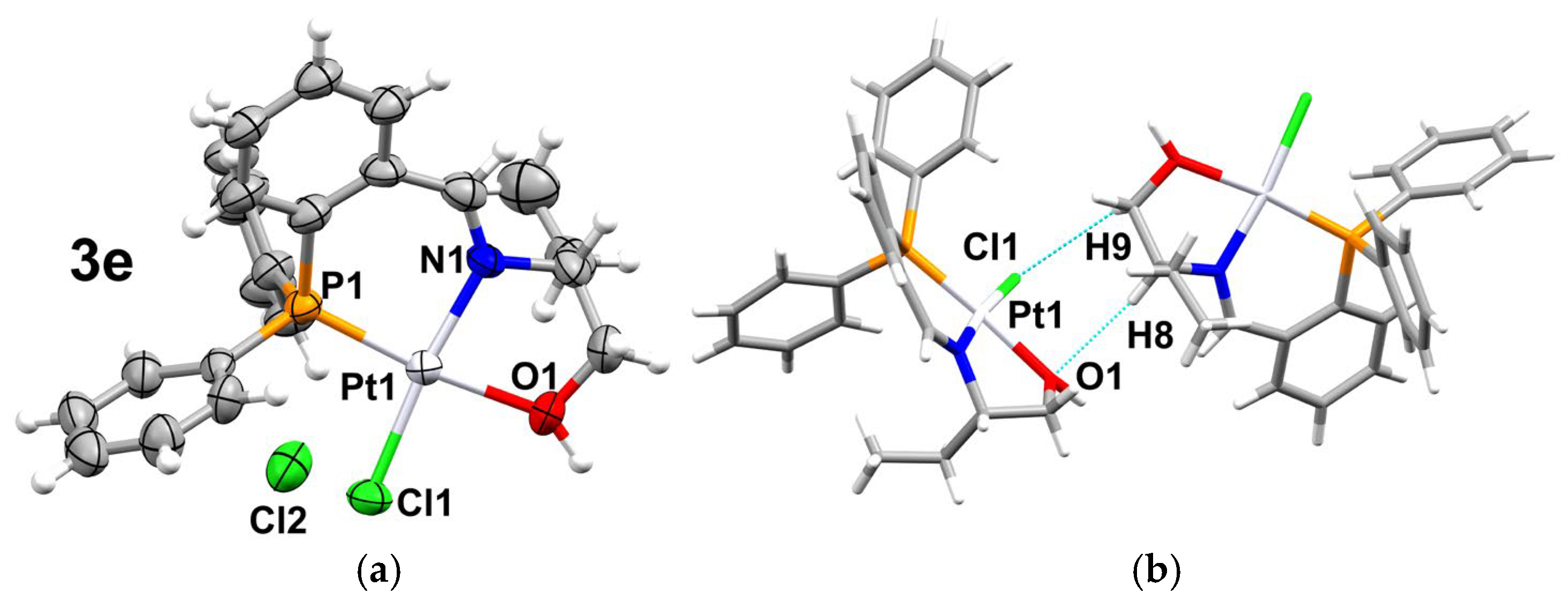

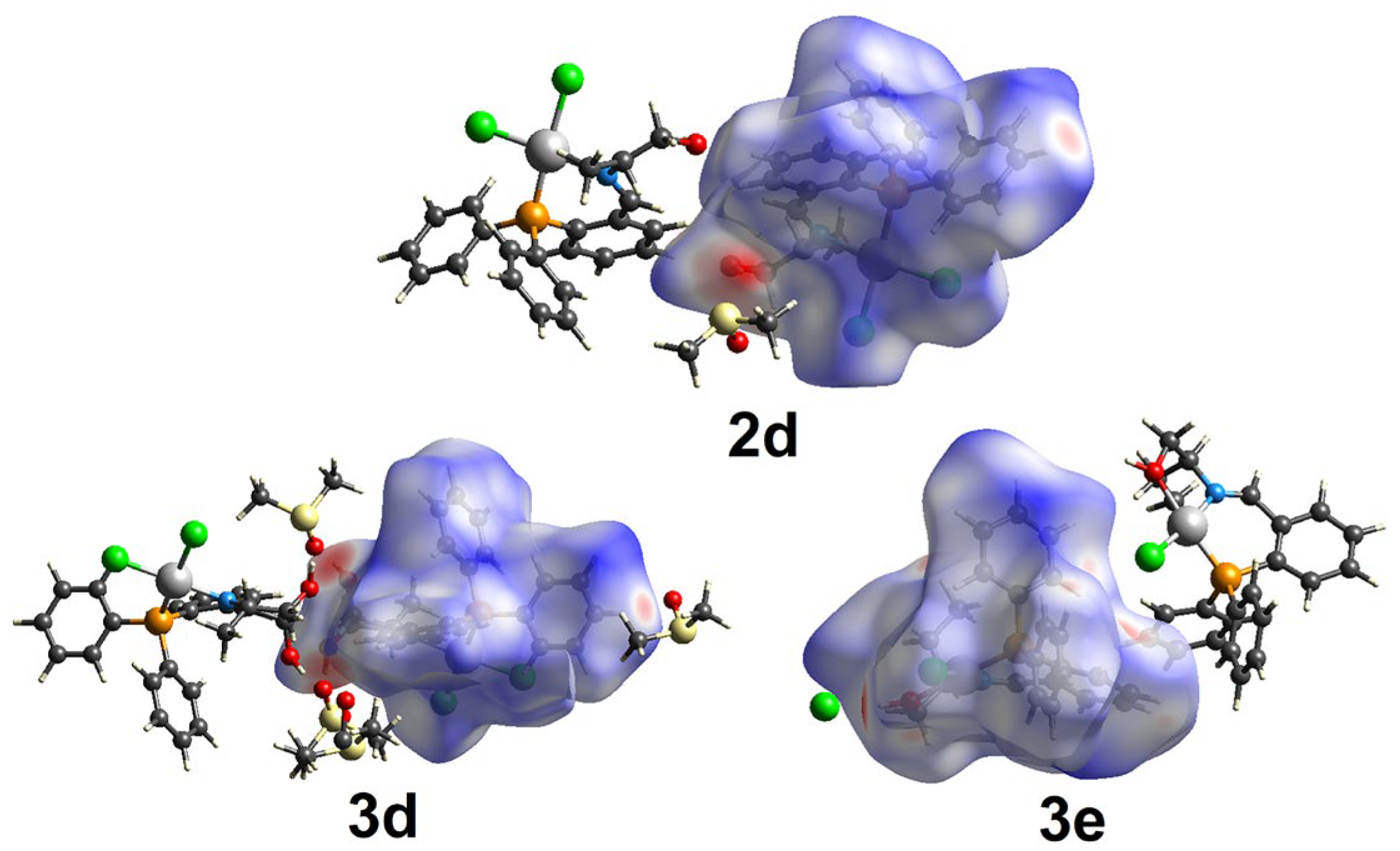

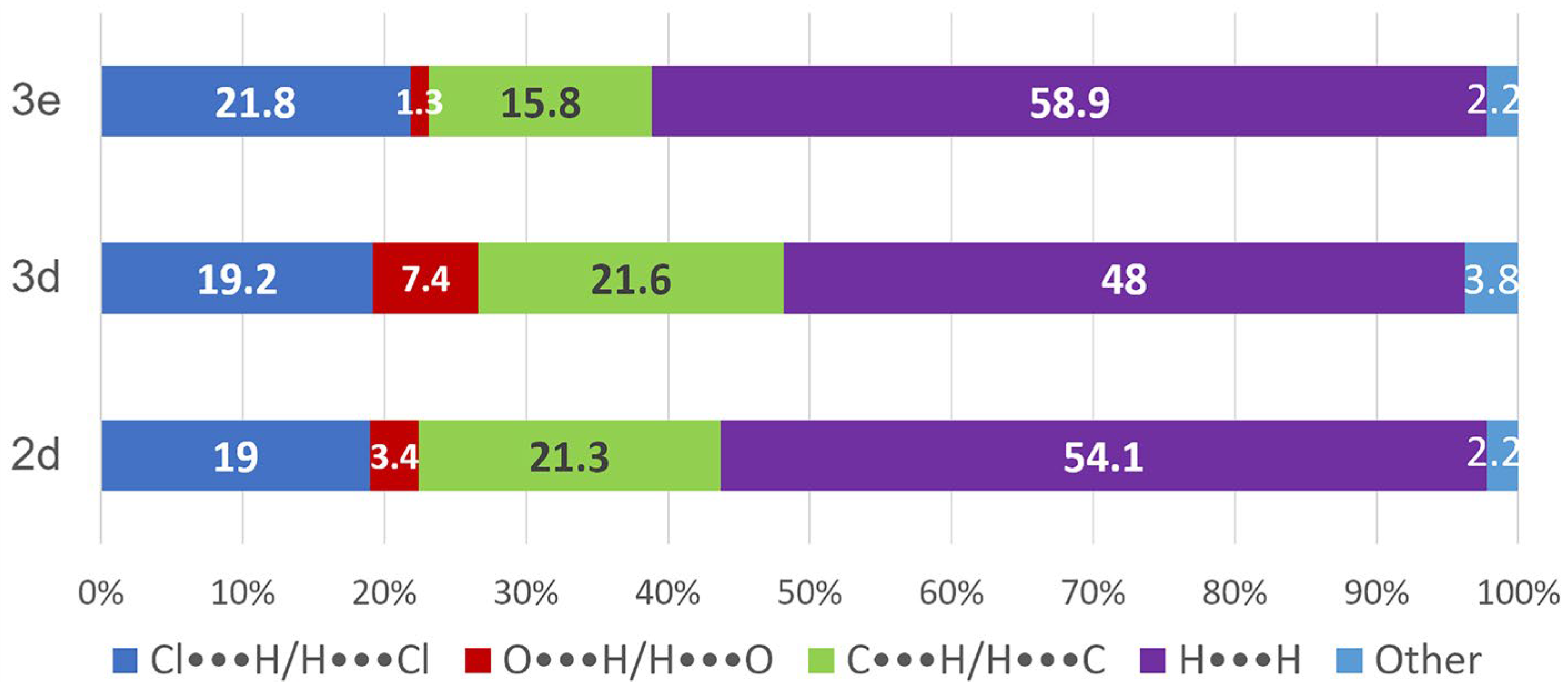

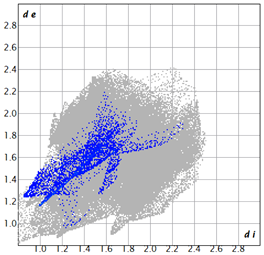

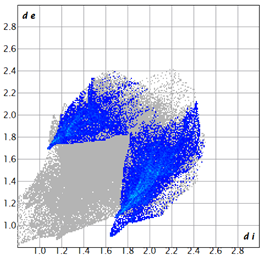

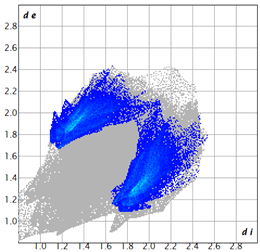

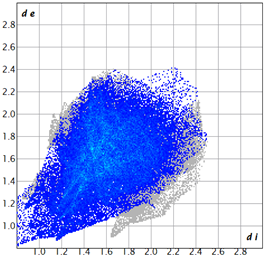

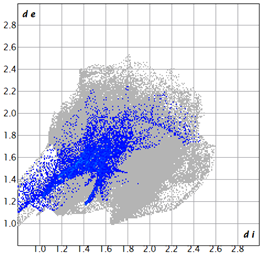

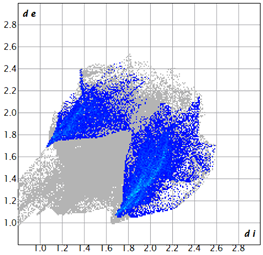

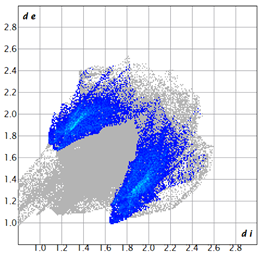

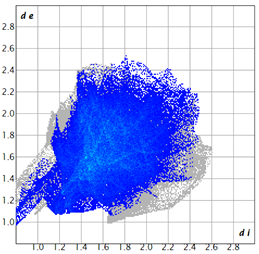

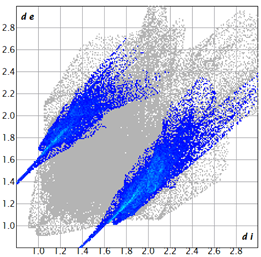

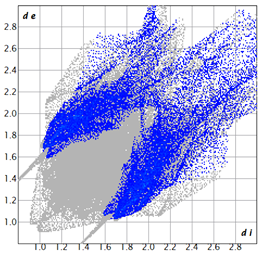

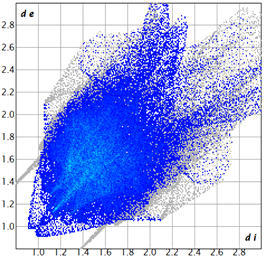

2.2. Supramolecular Analysis

2.3. Cytotoxic Evaluation

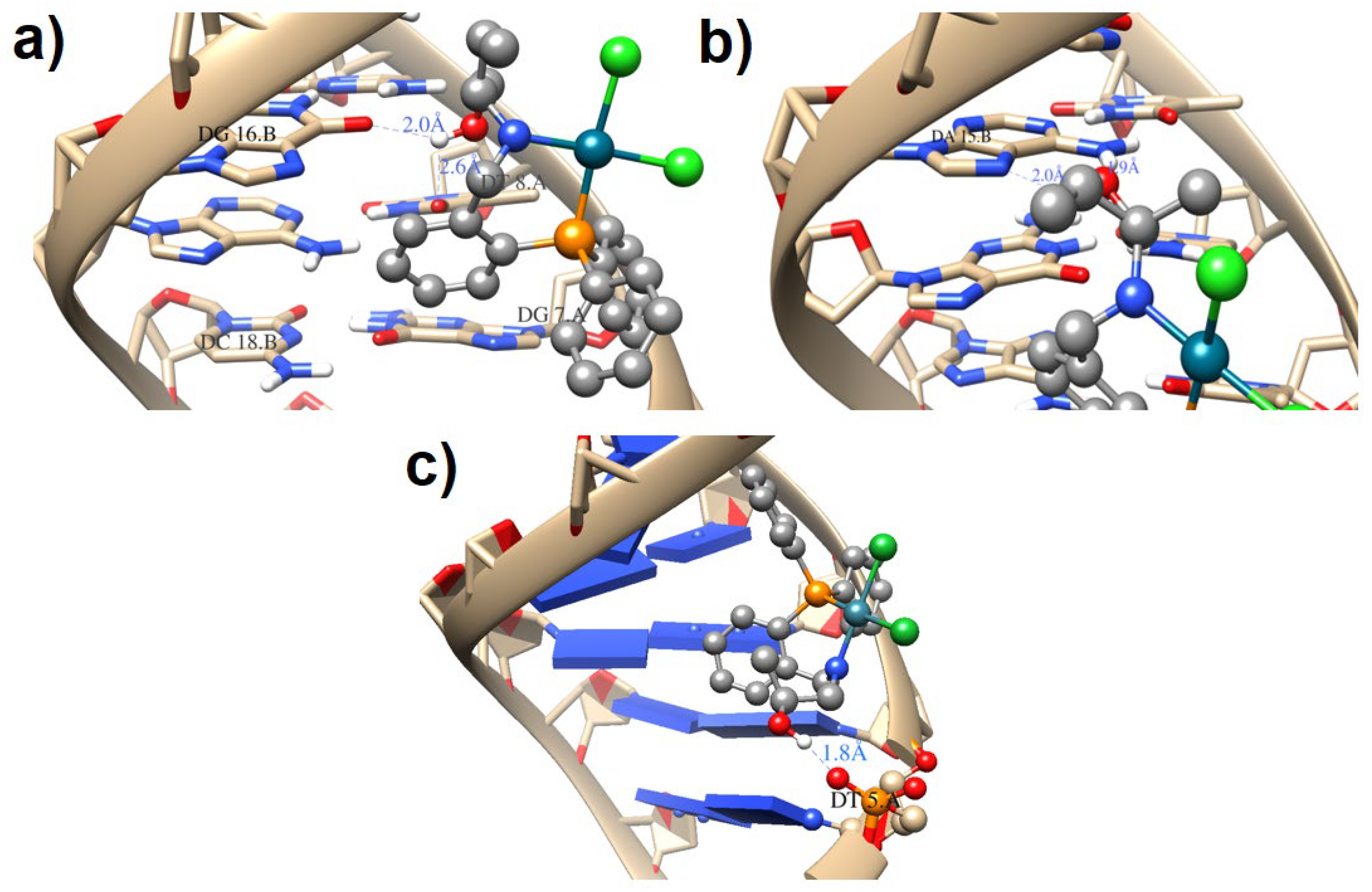

2.4. Computational Results

2.4.1. Electronic Structure Optimisation

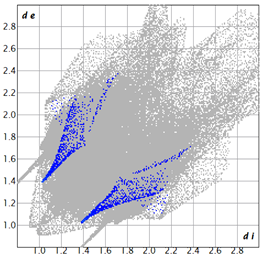

2.4.2. Molecular Docking Results

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Procedure for the Synthesis of Ligands (1a–h)

3.2. General Procedure for Synthesis of Pd(II)-Complexes (2a–h)

3.3. General Procedure for Synthesis of Pt(II)-Complexes (3a–h)

3.4. Cytotoxic Evaluation

3.5. Data Collection and Refinement for Crystalline Compounds

3.6. Computational Details

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alfonso-Herrera, L.A.; Rosete-Luna, S.; Hernández-Romero, D.; Rivera-Villanueva, J.M.; Olivares-Romero, J.L.; Cruz-Navarro, J.A.; Soto-Contreras, A.; Arenaza-Corona, A.; Morales-Morales, D.; Colorado-Peralta, R. Transition Metal Complexes with Tridentate Schiff Bases (ONO and ONN) Derived from Salicylaldehyde: An Analysis of Their Potential Anticancer Activity. ChemMedChem 2022, 17, e202200367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Cai, X.; Su, Y.; Hu, J.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, H.; Xiao, J.; Cheng, Y. Reducing cytotoxicity while improving anti-cancer drug loading capacity of polypropylenimine dendrimers by surface acetylation. Acta Biomater. 2012, 8, 4304–4313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Health Estimates: Leading Causes of Death, Cause-Specific Mortality, 2000–2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/mortality-and-global-health-estimates/ghe-leading-causes-of-death (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- World Health Organization. World Health Statistics 2022: Monitoring Health for the SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240051157 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Rottenberg, S.; Disler, C.; Perego, P. The rediscovery of platinum-based cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2021, 21, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romani, A.M.P. Cisplatin in cancer treatment. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2022, 206, 115323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dasari, S.; Tchounwou, P.B. Cisplatin in cancer therapy: Molecular mechanisms of action. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 740, 364–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynce, F.; Nunes, R. Role of Platinums in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2021, 23, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkisyan, Z.M.; Shkutina, I.V.; Srago, I.A.; Kabanov, A.V. Relevance of Using Platinum-Containing Antitumor Compounds (A Review). Pharm. Chem. J. 2022, 56, 729–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Romero, D.; Rosete-Luna, S.; López-Monteon, A.; Chávez-Piña, A.; Pérez-Hernández, N.; Marroquín-Flores, J.; Cruz-Navarro, A.; Pesado-Gómez, G.; Morales-Morales, D.; Colorado-Peralta, R. First-row transition metal compounds containing benzimidazole ligands: An overview of their anticancer and antitumor activity. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 439, 213930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzenbach, H.; Gahan, P.B. Resistance to cis- and carboplatin initiated by epigenetic changes in ovarian cancer patients. Cancer Drug Resist. 2019, 2, 271–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Kang, Y.; Chen, L.; Wang, H.; Liu, J.; Zeng, S.; Yu, L. The Drug-Resistance Mechanisms of Five Platinum-Based Antitumor Agents. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oun, R.; Moussa, Y.E.; Wheate, N.J. The side effects of platinum-based chemotherapy drugs: A review for chemists. Dalton Trans. 2018, 47, 6645–6653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanelli, M.; Formica, M.; Fusi, V.; Giorgi, L.; Micheloni, M.; Paoli, P. New trends in platinum and palladium complexes as antineoplastic agents. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2016, 310, 41–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarnomysy, R.; Radomska, D.; Szewczyk, O.K.; Roszczenko, P.; Bielawski, K. Platinum and Palladium Complexes as Promising Sources for Antitumor Treatments. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahromi, E.Z.; Divsalar, A.; Saboury, A.A.; Khaleghizadeh, S.; Mansouri-Torshizi, H.; Kostova, I.J. Palladium complexes: New candidates for anti-cancer drugs. Iran Chem. Soc. 2016, 13, 967–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, M.N.; Masood, S.; Chaudhry, G.; Muhammad, T.S.T.; Dalebrook, A.F.; Nazar, M.F.; Malik, F.P.; Mughal, E.U.; Wright, L.J. Synthesis, characterization and anti-cancer properties of water-soluble bis(PYE) pro-ligands and derived palladium(ii) complexes. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 15408–15418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, M.N.; Butt, A.M.; Chaudhry, G.; Perveen, F.; Nazar, M.F.; Masood, S.; Dalebrook, A.F.; Mughal, E.U.; Sumrra, S.H.; Sung, Y.Y.; et al. Pd(II) complexes with chelating N-(1-alkylpyridin-4(1H)-ylidene)amide (PYA) ligands: Synthesis, characterization and evaluation of anticancer activity. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2021, 224, 111590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, S.; Hussain, S.; Zafar, M.N.; Hussain, I.; Khan, F.; Mughal, E.U.; Tahir, M.N. Preliminary anticancer evaluation of new Pd(II) complexes bearing NNO donor ligands. Saudi Pharm. J. 2024, 32, 101915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, M.; Li, W.; Liang, J.; Pang., M.; Li., S.; Xu, G.; Zhu, M.; Liang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, F.J. Developing a Palladium(II) Agent to Overcome Multidrug Resistance and Metastasis of Liver Tumor by Targeted Multiacting on Tumor Cell, Inactivating Cancer-Associated Fibroblast and Activating Immune Response. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 16296–16310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Luo, W.; Zhu, M.; Zhao, L.; Gao, L.; Liang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, F. Human Serum Albumin-Platinum(II) Agent Nanoparticles Inhibit Tumor Growth Through Multimodal Action Against the Tumor Microenvironment. Mol. Pharm. 2024, 21, 346–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, X.-Y.; Sun, Z.-W.; Li, S.-H.; Xu, G.; Li, W.-J.; Zhang, Z.-L.; Liang, H.; Yang, F. Development of a Pt(II) compound based on indocyanine green@human serum albumin nanoparticles: Integrating phototherapy, chemotherapy and immunotherapy to overcome tumor cisplatin resistance. Rare Met. 2024, 43, 6006–6022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Li, S.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, G.; Man, X.; Yang, F.; Liang, H.J. Developing a Multitargeted Anticancer Palladium(II) Agent Based on the His-242 Residue in the IIA Subdomain of Human Serum Albumin. Med. Chem. 2023, 66, 8564–8579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rülke, R.E.; Kaasjager, V.E.; Wehman, P.; Elsevier, C.J.; van Leeuwen, P.W.N.M.; Vrieze, K.; Fraanje, J.; Goubitz, K.; Spek, A.L. Stable Palladium(0), Palladium(II), and Platinum(II) Complexes Containing a New, Multifunctional and Hemilabile Phosphino−Imino−Pyridyl Ligand: Synthesis, Characterization, and Reactivity. Organometallics 1996, 15, 3022–3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, S.; Knight, J.G.; Scanlan, T.H.; Elsegood, M.R.J.; Clegg, W.J. Iminophosphines: Synthesis, formation of 2,3-dihydro-1H-benzo[1,3]azaphosphol-3-ium salts and N-(pyridin-2-yl)-2-diphenylphosphinoylaniline, coordination chemistry and applications in platinum group catalyzed Suzuki coupling reactions and hydrosilylations. Organomet. Chem. 2002, 650, 231–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Gaxiola, J.I.; Valdés, H.; Rufino-Felipe, E.; Toscano, R.A.; Morales-Morales, D. Synthesis of Pd(II) complexes with P-N-OH ligands derived from 2-(diphenylphosphine)-benzaldehyde and various aminoalcohols and their catalytic evaluation on Suzuki-Miyaura couplings in aqueous media. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2020, 504, 119460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Barcia, L.M.; Fernández-Fariña, S.; Rodríguez-Silva, L.; Bermejo, M.R.; González-Noya, A.M.; Pedrido, R.J. Comparative study of the antitumoral activity of phosphine-thiosemicarbazone gold(I) complexes obtained by different methodologies. Inorg. Biochem. 2020, 203, 110931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traut-Johnstone, T.; Kanyanda, S.; Kriel, F.H.; Viljoen, T.; Kotze, P.D.R.; van Zyl, W.E.; Coates, J.; Rees, D.J.G.; Meyer, M.; Hewer, R.; et al. Heteroditopic P,N ligands in gold(I) complexes: Synthesis, structure and cytotoxicity. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2015, 145, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Guo, L.; Tian, Z.; Ge, X.; Gong, Y.; Zheng, H.; Shi, S.; Liu, Z. Lysosome-Targeted Phosphine-Imine Half-Sandwich Iridium(III) Anticancer Complexes: Synthesis, Characterization, and Biological Activity. Organometallics 2019, 38, 1761–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Đorđević, M.M.; Jeremić, D.A.; Rodić, M.V.; Simić, V.S.; Brčeski, I.D.; Leovac, V.M. Synthesis, structure and biological activities of Pd(II) and Pt(II) complexes with 2-(diphenylphosphino)benzaldehyde 1-adamantoylhydrazone. Polyhedron 2014, 68, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiririwa, H.; Moss, J.R.; Hendricks, D.; Smith, G.S.; Meijboom, R. Synthesis, characterisation and in vitro evaluation of platinum(II) and gold(I) iminophosphine complexes for anticancer activity. Polyhedron 2013, 49, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiririwa, H.; Moss, J.R.; Hendricks, D.; Meijboom, R.; Muller, A. Synthesis, characterisation and in vitro evaluation of palladium(II) iminophosphine complexes for anticancer activity. Transit. Met. Chem. 2013, 38, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motswainyana, W.M.; Onani, M.O.; Madiehe, A.M.; Saibu, M.; Thovhogi, N.; Lalancette, R.A. Imino-phosphine palladium(II) and platinum(II) complexes: Synthesis, molecular structures and evaluation as antitumor agents. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2013, 129, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalhan, S.C.; Hanson, R.W. Resurgence of Serine: An Often Neglected but Indispensable Amino Acid. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 19786–19791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spiegel, S.; Milstien, S. Sphingosine-1-phosphate: An enigmatic signalling lipid. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003, 4, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, S.; Milstien, S.; Spiegel, S.J. Sphingosine and Sphingosine Kinase 1 Involvement in Endocytic Membrane Trafficking. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 3074–3088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Małecka, M.; Budzisz, E. A structural framework of biologically active coumarin derivatives: Crystal structure and Hirshfeld surface analysis. CrystEngComm 2014, 16, 6654–6663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Małecka, M.; Kusz, J.; Eriksson, L.; Adamus-Grabicka, A.; Budzisz, E. The relationship between Hirshfeld potential and cytotoxic activity: A study along a series of flavonoid and chromanone derivatives. Acta Crystallogr. C Struct. Chem. 2020, C76, 723–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kupcewicz, B.; Małecka, M.; Zapadka, M.; Krajewska, U.; Rozalski, M.; Budzisz, E. Quantitative relationships between structure and cytotoxic activity of flavonoid derivatives. An application of Hirshfeld surface derived descriptors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 26, 3336–3341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinnon, J.J.; Jayatilaka, D.; Spackman, M.A. Towards quantitative analysis of intermolecular interactions with Hirshfeld surfaces. Chem. Commun. 2007, 2007, 3814–3816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spackman, M.A.; McKinnon, J.J. Fingerprinting intermolecular interactions in molecular crystals. CrystEngComm 2002, 4, 378–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monks, A.; Scudiero, D.; Skehan, P.; Shoemaker, R.; Paull, K.; Vistica, D.; Hose, C.; Langley, J.; Cronise, P.; Vaigro-Wolff, A.; et al. Feasibility of a High-Flux Anticancer Drug Screen Using a Diverse Panel of Cultured Human Tumor Cell Lines. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1991, 83, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruker. Apex3, Saint; Bruker AXS Inc.: Madison, WI, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C Struct. Chem. 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krause, L.; Herbst-Irmer, R.; Sheldrick, G.M.; Stalke, D.J. Comparison of silver and molybdenum microfocus X-ray sources for single-crystal structure determination. Appl. Crystallogr. 2015, 48, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, L.E.; Hay, P.J.; Martin, R.L. Revised Basis Sets for the LANL Effective Core Potentials. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008, 4, 1029–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marenich, A.V.; Cramer, C.J.; Truhlar, D.G. Universal Solvation Model Based on Solute Electron Density and on a Continuum Model of the Solvent Defined by the Bulk Dielectric Constant and Atomic Surface Tensions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 6378–6396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed, A.E.; Weinstock, R.B.; Weinhold, F.J. Natural population analysis. Chem. Phys. 1985, 83, 735–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 16, Revision C.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, G.M.; Huey, R.; Lindstrom, W.; Sanner, M.F.; Belew, R.K.; Goodsell, D.S.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 30, 2785–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahara, P.M.; Rosenzweig, A.C.; Frederick, C.A.; Lippard, S.J. Crystal structure of double-stranded DNA containing the major adduct of the anticancer drug cisplatin. Nature 1995, 377, 649–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasteiger, J.; Marsili, M. Iterative partial equalization of orbital electronegativity—A rapid access to atomic charges. Tetrahedron 1980, 36, 3219–3228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Couch, G.S.; Greenblatt, D.M.; Meng, E.C.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF Chimera—A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1605–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger. Schrödinger 2015 (Version 2.3.0): The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System; Schrödinger, LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Schrödinger. Schrödinger Release 2020-1: Maestro; Schrödinger, LLC: New York, NY, USA.

| Compound | 1d | 1e | 2d | 3d | 3e |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Empirical formula | C22H22NOP | C23H24NOP | C22H22Cl2NOPPd(DMSO) | C22H22Cl2NOPPt(DMSO) | C23H24Cl2NOPPt |

| Formula weight | 347.58 | 361.40 | 602.80 | 705.07 | 627.39 |

| Temperature (K) | 298(2) | 298(2) | 298(2) | 298(2) | 278(2) |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.71073 | 0.71073 | 0.71073 | 0.71073 | 0.71073 |

| Crystal system | Orthorhombic | Orthorhombic | Triclinic | Triclinic | Orthorhombic |

| Space group | Pbca | Pbca | P-1 | P-1 | Pna21 |

| Unit cell dimensions | a = 9.4896(8) Å b = 18.4909(16) Å c = 21.8278(18) Å α = 90° β = 90° γ = 90° | a = 9.9814(10) Å b = 18.6026(17) Å c = 21.742(2) Å α = 90° β = 90° γ = 90° | a = 9.1743(9) Å b = 10.0623(9) Å c = 14.0908(14) Å α = 92.699(3)° β = 99.021(3)° γ = 96.608(3)° | a = 9.1506(4) Å b = 10.0932(4) Å c = 14.1360(5) Å α = 92.7657(9)° β = 99.0621(8)° γ = 95.9741(8)° | a = 19.2035(11) Å b = 13.0441(8) Å c = 9.6781(6) Å α = 90° β = 90° γ = 90° |

| Volume (Å3) | 3830.2(6) | 4037.1(7) | 1273.3(2) | 1279.51(9) | 2424.3(3) |

| Z | 8 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Density (calc.) (Mg/m3) | 1.205 | 1.189 | 1.572 | 1.831 | 1.719 |

| Absorption coefficient | 0.152 mm−1 | 0.147 mm−1 | 1.105 mm−1 | 5.861 mm−1 | 6.088 mm−1 |

| F (0 0 0) | 1472.0 | 1536.0 | 612.0 | 690.0 | 1216.0 |

| Crystal size (mm3) | 0.333 × 0.254 × 0.222 | 0.6 × 0.19 × 0.1 | 0.274 × 0.101 × 0.088 | 0.419 × 0.329 × 0.201 | 0.31 × 0.077 × 0.041 |

| Theta range for data collection (°) | 4.406 to 50.706° | 3.746 to 50.816° | 4.53 to 50.874° | 4.536 to 50.62° | 5.242 to 50.508° |

| Index ranges | −11 ≤ h ≤ 11, −16 ≤ k ≤ 22, −17 ≤ l ≤ 26 | −12 ≤ h ≤ 12, −17 ≤ k ≤ 22, −26 ≤ l ≤ 26 | −11 ≤ h ≤ 11, −11 ≤ k ≤ 12, −16 ≤ l ≤ 16 | −10 ≤ h ≤ 10, −12 ≤ k ≤ 12, −16 ≤ l ≤ 16 | −22 ≤ h ≤ 22, −14 ≤ k ≤ 15, −4 ≤ l ≤ 11 |

| Reflections collected | 11,885 | 21,288 | 27,896 | 22,812 | 6987 |

| Independent reflections | 3502 [R(int) = 0.0841, R(sigma) =0.0708] | 3698 [R(int) = 0.1135, R(sigma) = 0.0943] | 4464 [R(int) = 0.0697, R(sigma) = 0.0456] | 4634 [R(int) = 0.0266, R(sigma) = 0.0185] | 2766 [R(int) = 0.0277, R(sigma) = 0.0374] |

| Data/restraints/parameters | 3502/1/230 | 3698/1/239 | 4464/180/356 | 4634/214/365 | 2766/331/361 |

| Goodness-of-fit on F2 | 0.946 | 1.030 | 1.120 | 0.991 | 1.074 |

| Final R indices [I > 2sigma(I)] | R1 = 0.0521, wR2 = 0.1057 | R1 = 0.0793, wR2 = 0.1776 | R1 = 0.0695, wR2 = 0.1843 | R1 = 0.0214, wR2 = 0.0618 | R1 = 0.0238, wR2 = 0.0520 |

| R indices (all data) | R1 = 0.0835, wR2 = 0.1226 | R1 = 0.1663, wR2 = 0.2340 | R1 = 0.0779, wR2 = 0.1955 | R1 = 0.0223, wR2 = 0.0623 | R1 = 0.0301, wR2 = 0.0556 |

| Largest diff. peak and hole (e.Å−3) | 0.47 and −0.37 | 0.53 and −0.28 | 1.24 and −1.83 | 1.01 and −0.80 | 0.70 and −0.41 |

| Compound | Interaction | Length (Å) D–X···A | Length (Å) D···A | Angle (°) D–X···A | Symmetry Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2d | C5H5···Cl1 C23H23A···Cl1 C23H23B···S1 | 2.902 2.936 2.727 | 3.723 3.886 3.405 | 147.97 172.39 127.96 | x, −1 + y, z −x, 1 − y, 2 − z −x, 2 − y, 2 − z |

| 3d | C5H5···Cl1 C14H14···O2 C23H23A···Cl1 O1H1···O2 | 2.895 2.399 2.860 1.885 | 3.727 3.311 3.608 2.673 | 149.53 166.37 135.66 152.33 | x, −1 + y, z x, y, 1 + z 1 − x, 1 − y, −z x, y, z |

| 3e | C9H9B···Cl1 C8H8···O1 C6H6···Cl2 C7H7···Cl2 O1H1···Cl2 C16H16···Cl2 C20H20···Cl1 | 2.942 2.512 2.835 2.800 1.882 2.842 2.912 | 3.638 3.456 3.706 3.690 2.849 3.760 3.563 | 129.58 102.23 156.66 160.54 171.19 169.55 127.99 | 1 − x, −y, 1/2 + z 1 − x, −y, 1/2 + z x, y, 1 + z x, y, 1 + z 1 − x, −y, 1/2 + z 1/2 + x, 1/2 − y, z 1/2−x, −1/2 + y, 1.5 + z |

| Compound | O∙∙∙H/H∙∙∙O (%) | Cl∙∙∙H/H∙∙∙Cl (%) | C∙∙∙H/H∙∙∙C (%) | H∙∙∙H (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2d |  3.4 |  19.0 |  21.3 |  54.1 |

| 3d |  7.4 |  19.2 |  21.6 |  48.0 |

| 3e |  1.3 |  21.8 |  15.8 |  58.9 |

| Compound | % Inhibition | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U251 | PC-3 | K562 | HCT-15 | MCF-7 | SKLU-1 | COS-7 | |

| 2a | 11.8 | 25.3 | 34.5 | 9.2 | 44.3 | 18.7 | 26.2 |

| 2b | 0 | 13.0 | 59.1 | 0 | 29.1 | 12.9 | 18.6 |

| 2c | 10.7 | 10.9 | 19.3 | 17.1 | 21.3 | 11.3 | 18.2 |

| 2d | 4.0 | 20.7 | 64.7 | 2.8 | 43.5 | 14.0 | 20.0 |

| 2e | 21.1 | 31.6 | 89.7 | 33.5 | 85.3 | 15.6 | 30.7 |

| 2f | 4.6 | 29.5 | 94.2 | 13.4 | 63.3 | 26.1 | 24.4 |

| 2g | 10.06 | 12.5 | 34.6 | 6.0 | 15.3 | 17.1 | 16.2 |

| 2h | 23.0 | 5.9 | 100 | 0 | 25.8 | 0 | 62.5 |

| cisplatin | 97.9 | 96.7 | 81.8 | 54.2 | 66.5 | 100 | 100 |

| Compound | % Inhibition | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U251 | PC-3 | K562 | HCT-15 | MCF-7 | SKLU-1 | COS-7 | |

| 3a | 0 | 0 | 9.9 | 2.4 | 5.4 | 3.0 | 7.4 |

| 3b | 77.6 | 30.0 | 98.7 | 18.5 | 42.26 | 87.7 | 25.6 |

| 3c | 0 | 0 | 12.6 | 0 | 3.6 | 26.2 | 0 |

| 3d | 95.9 | 93.4 | 100 | 74.6 | 85.5 | 100 | 100 |

| 3e | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 3f | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 3g | 100 | 1.8 | 100 | 92.3 | 100 | 97.9 | 100 |

| 3h | 73.2 | 53.9 | 97.2 | 88.5 | 89.2 | 96.6 | 100 |

| cisplatin | 97.9 | 96.7 | 81.8 | 54.2 | 66.5 | 100 | 100 |

| Compound | IC50 (µM) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| K562 | COS-7 | SI b | |

| 2a | 30.00 ± 3.0 | ---- | ---- |

| 2b | 20.17 ± 0.6 | 56.1 ± 9.3 | 2.8 |

| 2d | 14.96 ± 1.2 | ---- | ---- |

| 2e | 7.73 ± 1.4 | 11.2 ± 2.5 | 1.4 |

| 2f | 8.53 ± 1.9 | 26.4 ± 1.7 | 3.1 |

| 3b | 8.83 ± 1.5 | 77.9 ± 7.5 | 8.8 |

| cisplatin | 5.30 ± 1.3 | 5.8 ± 0.7 | 1.1 |

| Compound | Binding Energy | Compound | Binding Energy |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2a | −5.58 | 3a | −5.61 |

| 2b | −5.56 | 3b | −6.49 |

| 2c | −5.07 | 3c | −6.26 |

| 2d | −5.57 | 3d | −5.51 |

| 2e | −6.60 | 3e | −5.78 |

| 2f | −6.55 | 3f | −5.76 |

| 2g | −6.08 | 3g | −5.64 |

| 2h | −6.25 | 3h | −5.55 |

| cisplatin | −6.25 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ortega-Gaxiola, J.I.; Serrano-García, J.S.; Amaya-Flórez, A.; Galindo, J.R.; Arenaza-Corona, A.; Hernández-Ortega, S.; Ramírez-Apan, T.; Alí-Torres, J.; Orjuela, A.L.; Reyes-Márquez, V.; et al. Preliminary Study of the Cytotoxic Activity of Pd(II) and Pt(II) Complexes Bearing P-N ligands Derived from Aminoalcohols. Inorganics 2025, 13, 398. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics13120398

Ortega-Gaxiola JI, Serrano-García JS, Amaya-Flórez A, Galindo JR, Arenaza-Corona A, Hernández-Ortega S, Ramírez-Apan T, Alí-Torres J, Orjuela AL, Reyes-Márquez V, et al. Preliminary Study of the Cytotoxic Activity of Pd(II) and Pt(II) Complexes Bearing P-N ligands Derived from Aminoalcohols. Inorganics. 2025; 13(12):398. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics13120398

Chicago/Turabian StyleOrtega-Gaxiola, Jair Isai, Juan S. Serrano-García, Andrés Amaya-Flórez, Jordi R. Galindo, Antonino Arenaza-Corona, Simón Hernández-Ortega, Teresa Ramírez-Apan, Jorge Alí-Torres, Adrián L. Orjuela, Viviana Reyes-Márquez, and et al. 2025. "Preliminary Study of the Cytotoxic Activity of Pd(II) and Pt(II) Complexes Bearing P-N ligands Derived from Aminoalcohols" Inorganics 13, no. 12: 398. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics13120398

APA StyleOrtega-Gaxiola, J. I., Serrano-García, J. S., Amaya-Flórez, A., Galindo, J. R., Arenaza-Corona, A., Hernández-Ortega, S., Ramírez-Apan, T., Alí-Torres, J., Orjuela, A. L., Reyes-Márquez, V., Acosta-Encinas, M., Colorado-Peralta, R., & Morales-Morales, D. (2025). Preliminary Study of the Cytotoxic Activity of Pd(II) and Pt(II) Complexes Bearing P-N ligands Derived from Aminoalcohols. Inorganics, 13(12), 398. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics13120398