Abstract

Cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) have been extensively explored as tools for the intracellular delivery of diverse molecular cargoes. Although substantial progress has been made in elucidating their uptake mechanisms and sequence-dependent functions, limitations in cellular internalization efficiency remain a major challenge, hindering their broader biomedical application. To address this issue, the present study investigated whether microwave (MW) irradiation at 2.45 GHz can enhance CPP-mediated delivery. Using confocal laser scanning microscopy and fluorescence spectroscopy, we examined the effects of MW irradiation on the cellular uptake of arginine-rich peptides. Our results suggested that MW irradiation enhanced the cellular uptake of the peptides. These findings imply that CPP-mediated delivery assisted by MW irradiation is an effective method for improving intracellular transport and may open new avenues for the development of advanced drug delivery systems.

1. Introduction

Cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) represent a well-established strategy for delivering biologically active molecules into cells [1,2,3]. These peptides encompass a diverse range of sequences, including naturally derived peptides and synthetic analogs, and enable the efficient intracellular delivery of otherwise membrane-impermeable cargoes such as proteins, polynucleotides, and synthetic polymers, either through covalent conjugation or noncovalent complex formation [4,5]. Representative CPPs include peptides derived from the HIV-1 Tat protein and oligoarginines, which contain basic amino acids such as lysine and arginine that are positively charged under physiological conditions and play a critical role in membrane translocation. These peptides have been relatively well studied and are known to exhibit high cellular uptake efficiency, and considerable progress has been made in elucidating their internalization pathways. CPPs are generally internalized through two major pathways: direct translocation across the plasma membrane and endocytosis. Despite substantial progress in elucidating their uptake mechanisms and sequence-dependent behaviors, several challenges remain. High CPP concentrations can induce cytotoxicity, and conjugation with cargo molecules often reduces uptake efficiency [6]. In addition, CPP internalization is often compromised by biomolecular contaminants such as serum proteins, which are present under certain physiological conditions [7]. These limitations have motivated ongoing efforts to improve delivery efficiency and expand the biomedical applications of CPP-based technologies.

In parallel with efforts to optimize CPP-mediated delivery, increasing attention has been directed toward physical stimuli that may enhance cellular uptake [8,9,10]. Among these stimuli, microwaves (MWs), a type of electromagnetic wave widely used in various fields, such as science, industry, and medicine [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20], have emerged as a promising candidate in this context. For example, MW irradiation at 18 GHz has been shown to enhance the uptake of fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated dextrin into Escherichia coli [21] and silica nanospheres into Gram-positive cocci [22]. Similar MW-induced enhancements in silica nanosphere internalization have been reported in rabbit red blood cells and rat adrenal pheochromocytoma cells [23,24]. In mammalian cells, MW irradiation at 18 GHz has also been shown to enhance the uptake of peptides [25,26]. Furthermore, MW irradiation at 2.45 GHz has been reported to enhance the cellular uptake of the anticancer drug doxorubicin into MCF-7 human breast cancer cells [27]. Collectively, these findings suggest that MW irradiation induces subtle perturbations in cellular structures that facilitate the entry of exogenous materials. Although MW irradiation has been reported to enhance the cellular uptake of various molecules and nanomaterials, its applicability to CPPs and the underlying mechanisms involved remain poorly understood [24].

Given these reports, MW irradiation may offer a means to address some of the limitations associated with CPP-mediated delivery. Based on the hypothesis that MW irradiation induces transient pore formation in cellular membranes [24], we hypothesized that MW irradiation could similarly enhance the uptake of CPPs. Because the detailed mechanisms by which MW irradiation affects the cellular uptake of exogenous materials remain poorly understood, arginine-rich peptides, one of the most extensively studied classes of CPPs, were selected in this study to facilitate the interpretation and discussion of the experimental results, and we investigated the effect of MW irradiation on the internalization of the peptides into HeLa cells, both in serum-free and serum-containing media. To the best of our knowledge, this study provides the first experimental evaluation of a hybrid intracellular delivery strategy that combines CPPs with MW irradiation, thereby offering a promising approach for the development of advanced drug delivery systems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General Remarks

All chemicals and solvents were of reagent or high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) grade and were used without further purification. HPLC was performed using a GL7410 HPLC system (GL Sciences Inc., Tokyo, Japan) equipped with an Inertsil ODS-3 column (10 mm × 250 mm; GL Sciences) for preparative purification. A linear gradient was applied using 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in Milli-Q water (Solution A) and 0.08% TFA in acetonitrile (Solution B). Peptides were analyzed by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) using an Autoflex III mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Billerrica, MA, USA) with 3,5-dimethoxy-4-hydroxycinnamic acid as the matrix. Amino acid analysis was conducted using an Inertsil ODS-2 column (4.6 mm × 200 mm; GL Sciences) after hydrolyzing peptides in 6 M HCl at 110 °C for 24 h in a sealed tube, followed by derivatization with phenylisothiocyanate. Nα-(((9H-fluoren-9-yl)methoxy)carbonyl) (Fmoc))-Nω-(2,2,4,6,7-pentamethyldihydrobenzofuran-5-sulfonyl)-L-arginine (Fmoc-L-Arg(Pbf)-OH), Fmoc-NH-SAL PEG resin, 2-(1H-benzotriazole-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (HBTU), 1-hydroxy benzotriazole monohydrate (HOBt·H2O), 1-((dimethylamino)(dimethyliminio)methyl)-1H-[1,2,3]triazolo[4,5-b]pyridine 3-oxide hexafluorophosphate (HATU), N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIEA), TFA, and piperidine were obtained from Watanabe Chemical Industries, Ltd. (Hiroshima, Japan). 5(6)-Carboxyfluorescein (Flu) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). N-Methylpyrrolidone (NMP), triisopropylsilane, and diethyl ether were purchased from FUJIFILM Wako Chemical Corporation (Osaka, Japan).

2.2. Peptide Synthesis

The peptides were manually synthesized on Fmoc-NH-SAL PEG resin using standard Fmoc solid-phase synthesis [28]. For Fmoc-L-Arg(Pbf)-OH, coupling was performed for 30 min using the amino acids (10 eq.(equivalent)), HBTU (10 eq.), HOBt⸱H2O (10 eq.), and DIEA (8 eq.). Coupling of 5(6)-carboxyfluorescein (Flu) was carried out using 5(6)-carboxyfluorescein (4 eq.), HATU (4 eq.), and DIEA (8 eq.). Deprotection of the Fmoc group was achieved using 25% piperidine in NMP. The side chain of L-arginine was protected with the Pbf group. Cleavage of the synthesized peptides from the resins and global deprotection of side-chain protecting groups were performed using a TFA/H2O/triisopropylsilane (95/1/4, v/v/v). The peptides were precipitated by the addition of cold diethyl ether, collected by centrifugation, and dried under vacuum. Crude peptides were purified by reverse-phase HPLC and characterized by MALDI-TOF MS: Flu-R4, m/z 1001.0 ([M + H]+ calcd.1001.1); Flu-R6 m/z 1313.0 ([M + H]+ calcd. 1313.5); Flu-R8, m/z 1625.5 ([M + H]+ calcd. 1625.9). The total yields of Flu-R4 (molecular weight (MW): 1000.1), Flu-R6 (MW: 1312.5), and Flu-R8 (MW: 1624.8) were 13%, 15%, and 3%, respectively, with HPLC purities of 97.1%, 99.4%, and 99.8%. Purified peptides were dissolved in Milli-Q water at a concentration of 1 mM. The concentration was determined by amino acid analysis, and the peptide solutions were stored at 4 °C.

2.3. MW Irradiation System

The MW irradiating system, manufactured as a medical apparatus by Minato Medical Science Co., Ltd., (Osaka, Japan), was used (Figure S1a). The system generated MWs at a frequency of 2450 ± 3 MHz using a semiconductor-type oscillator, with an adjustable output power ranging from 10 to 60 W in 10 W increments. The output was delivered to a linearly polarized patch antenna with a voltage standing-wave ratio < 1.4. In this study, duty ratios of 9–45%, corresponding to output powers of 10–50 W, were used. The output power of the system was controlled by adjusting the ON/OFF cycle of the MWs, where the duty ratio was defined as the fraction of time during which the MWs were ON relative to the total cycle time. By setting the duty ratio of a device with a maximum output of 110 W to 9% or 45%, MW outputs of 10 W and 50 W, respectively, could be achieved. Cell culture dishes were placed 35 mm above the antenna and irradiated with MWs.

A thermocouple thermometer (Card Logger MR5300 with probe MR9302, CHINO Corp., Tokyo, Japan) was used to measure the temperature (Figure S1b). Previously, we had checked temperatures using the thermocouple thermometer had been almost the same as those using thermography (OPTXI40LTF20CFT090, Optris GmbH, Berlin, Germany) on the time-point measurements [18].

The electric field (E-field) of the irradiated MWs from the generators was monitored using a sensor head (6 mm × 6 mm × 23 mm, ES-100, Seikoh Giken Co., Ltd., Matsudo, Japan) and a controller (C5-D1-A, Seikoh Giken Co., Ltd., Matsudo, Japan) (Figure S1c). When we placed a cell culture dish at a position 35 mm above the MW antenna and measured the E-field strength above the dish under MW irradiation at 10 W, the X, Y, and Z components of the E-field were 355, 1616, and 211 V/m, respectively.

2.4. Cell Culture

HeLa cell line was obtained from Japanese Collection of Research Bioresources Cell Bank (JCRB; No. JCRB9004 Lot NO. 11062023). HeLa cells were cultured in D-MEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Although different types of containers were used for subsequent microscopy observations and for peptide quantification/cell viability measurements, the same volume of peptide solution was added in all cases.

2.5. Phase-Contrast Microscope Measurement

HeLa cells (3.4 × 105 cells) were seeded in 35 mm cell culture dishes (Wuxi NEST Bio-technology Co., Ltd., Wuxi, China). The samples were then exposed to MW irradiation at 10 W for 10–60 min, after which the cells were observed using phase-contrast microscopy (IX70, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) either immediately or following an additional 96 h of culture at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

2.6. Cytotoxicity Test

HeLa cells (3.4 × 105 cells) were seeded in 35 mm cell culture dishes and cultured at 37 °C for 24 h in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. The culture medium was then removed, and the cells were washed three times with 1 × PBS buffer (1 mL per wash). Subsequently, 800 μL of medium containing 5–20 μM peptide solution was added to each dish, and the samples were exposed to MW irradiation at 10 W for 10–60 min, followed by incubation at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. For nonirradiated conditions, cells were incubated at 32 °C for 10–60 min, followed by incubation at 37 °C min under the same conditions. For control experiments, cells were incubated at 37 °C without using peptides under nonirradiation. After incubation, the medium was removed, and the cells were washed three times with 1 × PBS buffer (1 mL per wash). Cytotoxicity was assessed using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8, Dojindo Laboratories, Mashiki, Japan).

2.7. Cellular Uptake of Peptides and Confocal Microscopic Observation

For serum-free conditions, HeLa cells (3.3 × 104 cells) were seeded in cell culture dishes (CELLview, Greiner Bio-One International GmbH, Kremsmünster, Austria) containing D-MEM supplemented with 1% penicillin-streptomycin (serum-free medium) and cultured at 37 °C for 24 h in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. After incubation, the medium was removed, and the cells were washed twice with 1 × PBS buffer (200 μL per wash). 800 μL of peptide solution prepared in serum-free medium with 20 mM HEPES buffer was added to each dish at a final peptide concentration of 10 μM. MW irradiation was performed at 10 W for 30 min. Following MW exposure, cells were incubated at 37 °C for 90 min in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. For nonirradiated conditions, cells were maintained at 32 °C for 30 min, followed by incubation at 37 °C for 90 min under the same atmospheric conditions. After incubation, cells were washed once with 200 μL of 20 mM HEPES buffer and then washed again with 100 μL of the same buffer. Cell nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 and observed using a confocal laser scanning microscope (LSM 700, Carl Zeiss Inc., Jena, Germany) equipped with a Plan-Apochromat 40×/1.3 oil DIC M27 objective lens. For observation of peptides and Hoechst 33342, the excitation and emission wavelengths were 492 and 350 nm for the green channel, and 579 and 461 nm for the red channel, respectively.

For serum-containing conditions, HeLa cells (3.3 × 104 cells) were seeded in cell culture dishes containing D-MEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (serum-containing medium) and cultured at 37 °C for 24 h in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. After incubation, the medium was removed, and the cells were washed twice with 1 × PBS buffer (200 μL per wash). 800 μL of peptide solution prepared in serum-containing medium with 20 mM HEPES buffer was added to each dish at a final peptide concentration of 5–20 μM. MW irradiation was performed at 10 W for 15 min. Following MW exposure, cells were incubated at 37 °C for 45 min in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. For nonirradiated conditions, cells were maintained at 32 °C for 15 min, followed by incubation at 37 °C for 45 min under the same atmospheric conditions. After incubation, cells were washed once with 200 μL of 20 mM HEPES buffer and then washed again with 100 μL of the same buffer. Cell nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 and observed using a confocal laser scanning microscope. For observation of peptides and Hoechst 33342, the excitation and emission wavelengths were 488 and 521 nm for the green channel, and 405 and 461 nm for the blue channel.

2.8. Quantification of Peptides Internalized into Cells

HeLa cells (3.4 × 105 cells) were seeded in 35 mm cell culture dishes and cultured at 37 °C for 24 h in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. The culture medium was then removed, and the cells were washed twice with 1× PBS buffer (500 μL per wash). A peptide solution (800 μL) prepared in serum-free medium with 20 mM HEPES buffer was added to the cells at a final peptide concentration of 10 μM. MW irradiation was performed at 10 W for 30 min, followed by incubation at 37 °C for 90 min in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. For nonirradiated controls, after addition of the 10 μM peptide solution (800 μL), the cells were maintained at 32 °C for 30 min, and then incubated at 37 °C for 90 min in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. After incubation, the medium was removed, and the cells were washed twice with 1 × PBS buffer (500 μL per wash). Next, 200 μL of 0.25 w/v% trypsin was added to each dish and incubated at 37 °C for 5 min. After that, 500 μL of 1 × PBS buffer was added, and the cell suspension was centrifuged at 1500 rpm at 25 °C for 3 min. The supernatant was removed, and this washing procedure was repeated twice. The resulting cell pellet was resuspended in 125 μL of 20 mM HEPES buffer. A solution containing CCK-8 (10 μL) and serum-free medium (40 μL) was dispensed into a 96-well plate (50 μL per well), followed by the addition of 50 μL of the cell suspension to each well. The plate was maintained at 37 °C for 60 min, and optical density (OD) of formazan at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader (MTP-310, Corona Electric Co., Ltd., Ibaraki, Japan). A CCK-8 assay was performed using known cell numbers to confirm a proportional relationship between cell number and OD of formazan at 450 nm. Using the resulting calibration curve, the number of cells (Ncells) in each sample was calculated from the measured OD. The formula used to calculate Ncells was shown in Equation (1). To lysis the cells, 70 μL of lysis buffer (0.4% NP-40, 0.04% SDS, and 8 mM HEPES) was added to the cell suspension. The mixture was sonicated for 10 min in an ice bath using an ultrasonicator (Bioruptor UCD-250, Cosmo Bio Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The lysate was then centrifuged at 8200 rpm at 4 °C for 10 min. The fluorescence of the resulting supernatant (100 μL) was measured using a microplate reader (MTP-601 Lab, Corona Electric Co., Ltd., Ibaraki, Japan). The fluorescence intensity of the peptide per 1000 cells (F1000) was calculated using the following Equation (2).

where a and b represent the slope and the intercept in the calibration curve, respectively.

Ncells = {(ODsample − ODblank) − b }/a

F1000 = (Fsample − Fblank) × 1000/Ncells

2.9. Quantification of Peptides Internalized into Nuclei

HeLa cells (3.4 × 105 cells) were seeded in 35 mm cell culture dishes and cultured at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 for 24 h. After removing the culture medium, the cells were washed twice with 1 × PBS buffer (500 μL per wash). A peptide solution (800 μL) prepared in serum-free medium with 20 mM HEPES buffer was added to the cells at a final peptide concentration of 10 μM. MW irradiation was performed at 10 W for 30 min, followed by incubation at 37 °C for 90 min in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. For nonirradiated controls, cells were treated with same peptide solution (800 μL), kept at 32 °C for 30 min, and then incubated at 37 °C for 90 min in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. After incubation, the cells were washed twice with 1 × PBS buffer (500 μL per wash). Next, 200 μL of 0.25 w/v% trypsin was added and incubated at 37 °C for 5 min. Cells were collected by adding 500 μL of 1 × PBS and centrifugation at 1500 rpm for 3 min. The supernatant was removed, and the pellet was resuspended in 500 μL of 1 × PBS buffer. A portion of the suspension (50 μL) was diluted in 450 μL of 1 × PBS buffer, centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 3 min, and resuspended in 20 mM HEPES buffer. A mixture of CCK-8 reagent (10 μL) and serum-free medium (40 μL) was added to each well of a 96-well plate (50 μL per well), followed by the addition of 50 μL of the prepared cell suspension. The plate was incubated at 37 °C for 60 min, and the OD of formazan at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader (MTP-310 Lab, Corona Electric Co., Ltd., Ibaraki, Japan). A CCK-8 assay was performed using known cell numbers to confirm a proportional relationship between cell number and OD of formazan at 450 nm. Using the resulting calibration curve, the number of cells (Ncells) in each sample was calculated from the measured OD. The formula used to calculate Ncells was shown in Equation (1) in Section 2.8. The remaining 450 μL of the cell suspension was centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 3 min, and the supernatant was removed. Cold Cytoplasmic Extraction Regents I (CER I, NE-PER™ Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagents, ThermoFisher scientific, Tokyo, Japan; 50 μL) was added to the pellet. The pellet was vortexed for 15 s to achieve complete resuspension and incubated on ice for 10 min. CER II (NE-PER™ Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagents, ThermoFisher scientific, Tokyo, Japan; 2.75 μL) was added, followed by vertexing for 5 s and incubation on ice for 1 min. The sample was vortexed again for 5 s and centrifuged at 16,000× g at 4 °C for 5 min. The supernatant was collected and kept on ice. The pellet containing nuclei was resuspended in 25 μL of cold Nuclear Extraction Regent (NER) (NE-PER™ Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagents, ThermoFisher scientific, Tokyo, Japan) and vortexed for 15 s, then incubated on ice for 10 min. This vortex–incubation cycle was repeated four times. The samples were centrifuged at 16,000× g at 4 °C for 10 min, and the supernatant containing the nuclear extract was collected and kept on ice. The aliquot of the extract (10 μL) was used for fluorescence measurement with a microplate reader. The fluorescence intensity of the peptide per 1000 cells (F1000) was calculated using the following Equation (2) in Section 2.8.

2.10. Endocytosis Inhibition Assay

HeLa cells (3.4 × 105 cells) were seeded in 35 mm cell culture dishes and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. The culture medium was then removed, and the cells were washed three times with 1 × PBS buffer (500 μL each). Subsequently, 800 μL of D-MEM supplemented with 1% penicillin-streptomycin and 5 μM cytochalasin D was added to the cells, followed by incubation at 37 °C for 15 min in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. After incubation, the medium containing cytochalasin D was removed, and the cells were washed three times with 1 × PBS buffer (500 μL each). Then, 800 μL of D-MEM supplemented with 1% penicillin-streptomycin, 10 μM peptide, 5 μM cytochalasin D, and 20 mM HEPES was added to the cells. MW irradiation was carried out at 10 W for 30 min, followed by incubation at 37 °C for 90 min in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. After incubation, cells were observed using confocal laser scanning microscopy and peptide internalization was quantified using the same method as described in Section 2.8.

2.11. Statistical Analysis

Two-tailed student’s t-tests were carried out in Microsoft Excel. Data were assumed to be normally distributed, and homogeneity of variances was assessed using an F-test before applying the t-tests. Experiments with p values not greater than 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Design of Peptides

Peptides are relatively easy to synthesize, and the efficiency of their cellular uptake can be modulated by altering their amino acid sequences. By utilizing peptides with differing uptake efficiencies, it may be possible to detect even modest effects of MW on peptide internalization. In this study, arginine-rich peptides were utilized as CPPs because of their well-characterized ability to translocate across cellular membranes, primarily via endocytosis. It is known that the presence of six or more L-arginine residues is appropriate for efficient intracellular delivery [29]. Although peptides containing four L-arginine residues are generally considered too short for efficient cellular uptake, we hypothesized that MWs could enhance their internalization. Accordingly, three peptides containing 4, 6, or 8 L-arginine residues were synthesized (Table 1, Figure S2). To perform observation and quantification of internalized peptides into cells, 5(6)-carboxyfluorescein (Flu) was conjugated to the N-terminus of each peptide.

Table 1.

Sequence and structure of peptides.

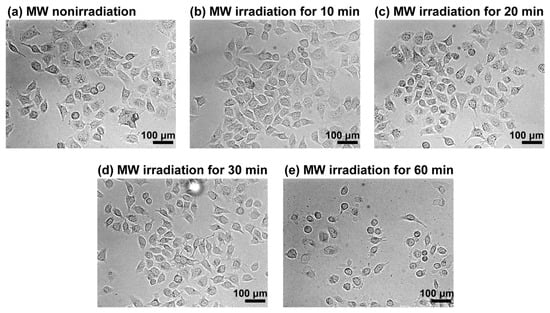

3.2. Effects of MW Irradiation on Cells

We used a previously developed MW irradiation system operating at 2.45 GHz with a semiconductor-type oscillator (Figure S1a) [18]. Before investigating the cellular uptake of peptides under MW irradiation, we evaluated the effects of MW irradiation on cells. HeLa cells were irradiated with MWs at 10 W, and morphological changes were observed using phase-contrast microscopy (Figure 1). Control experiments were conducted under nonirradiated conditions at 32 °C, corresponding to the temperature observed during MW irradiation at 10 W for 30 min (Figure S1b). Temperature measurements were performed using a thermocouple thermometer. No significant morphological differences were observed between cells after MW irradiation for 10 or 20 min and nonirradiated cells, suggesting the absence of immediate cellular damage. By contrast, slight morphological alterations were detected after 30 min of MW irradiation, and most cells exhibited a rounded morphology after 60 min, indicative of cell death. These results indicate that although prolonged MW irradiation can damage cells, short-term irradiation does not cause substantial cytotoxic effects.

Figure 1.

Phase-contrast microscopy images of HeLa cells. The images show cells (a) before and after MW irradiation at 10 W for (b) 10 min, (c) 20 min, (d) 30 min, and (e) 60 min.

To assess cell viability further, CCK-8 assays were performed on cells subjected to MW irradiation at 10 W for 30 or 60 min, corresponding to the conditions under which morphological changes were observed. When the viability of nonirradiated cells was set at 100%, cell viability after 30 and 60 min of irradiation was 97.8% and 54.0%, respectively (Figure S3a). These data indicate that irradiation for 30 min does not significantly induce cell death. To assess the long-term effects of MW irradiation on cells, HeLa cells exposed to MW at 10 W for 30 min were subsequently cultured under 5% CO2 at 37 °C for 96 h, followed by morphological observation. The morphological changes observed immediately after irradiation were no longer apparent (Figure S4), and the cells exhibited a normal morphology comparable to that of nonirradiated controls. In addition, cell viability was 95.9% relative to the nonirradiated control (Figure S3b). These results suggest that 30 min of MW irradiation does not induce notable cytotoxicity either immediately after irradiation or following extended culture, demonstrating minimal short- and long-term toxicity.

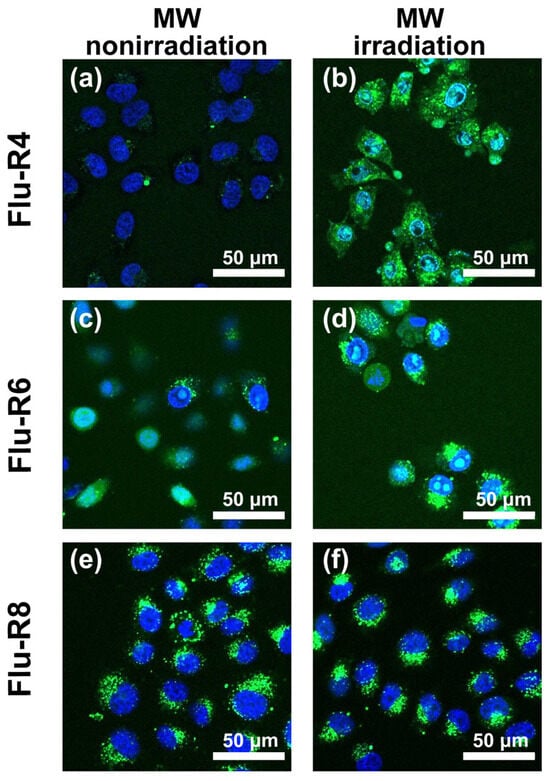

3.3. Effects of MW Irradiation on Cellular Uptake of the Peptides

First, the effects of MW irradiation on cellular uptake of the peptides were investigated. The peptides were added to HeLa cells in serum-free medium and then subjected to MW irradiation at 10 W for 30 min. Next, internalized peptides were observed by confocal fluorescence microscopy (Figure 2). Under nonirradiated conditions, the fluorescence derived from Flu-R4 was barely detectable, indicating minimal cellular uptake. By contrast, MW irradiation markedly increased intracellular fluorescence, suggesting the enhanced uptake of Flu-R4. For Flu-R6 and Flu-R8, peptide-derived fluorescence was observed even without MW irradiation, and MW exposure resulted in little additional enhancement. These observations suggest that among the peptides, Flu-R4 exhibits the most pronounced response to MW irradiation. To assess the cytotoxicity associated with peptide uptake under MW irradiation, a CCK-8 assay was performed. Cell viability was calculated relative to nonirradiated cells maintained at 37 °C in 5% CO2, which was defined as 100%. The viabilities of MW-irradiated cells following the uptake of Flu-R4, Flu-R6, and Flu-R8 were 91.7%, 92.3%, and 94.3%, respectively, indicating minimal cytotoxicity under the tested conditions (Figure S5).

Figure 2.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy images of HeLa cells after uptake of 10 μM peptides. The images show HeLa cells following the uptake of (a,b) Flu-R4, (c,d) Flu-R6, and (e,f) Flu-R8 under (a,c,e) MW irradiation at 10 W for 30 min and (b,d,f) nonirradiated conditions. Nuclei were stained blue with Hoechst 33342. Green fluorescence represents internalized peptides.

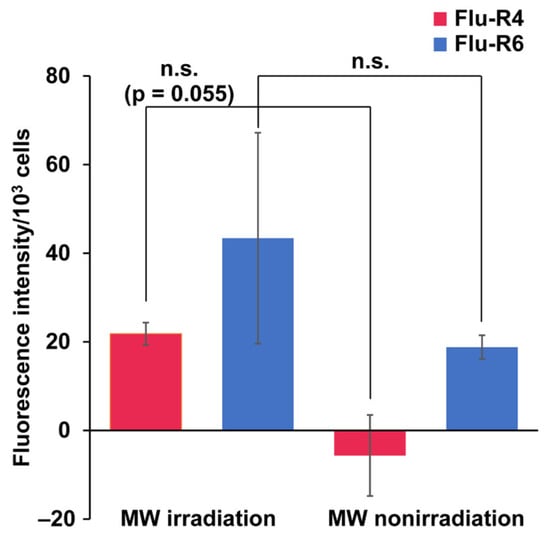

Next, quantitative analysis of peptide internalization was carried out for Flu-R4 and Flu-R6. Following trypsinization, peptide-internalized cells were lysed by ultrasonication, and the resulting lysates were measured to determine the amount of internalized peptide (Figure 3). Consistent with the microscopic observations, peptide-derived fluorescence tended to be higher under MW irradiation, suggesting that MW irradiation may enhance peptide uptake. However, no statistically significant difference was observed between the irradiated and nonirradiated conditions. Future work will focus on further refinement of the peptide quantification method and optimization of the MW irradiation conditions. These additional studies may also enhance the difference in peptide internalization between the irradiated and nonirradiated conditions. To distinguish MW-specific effects from general thermal effects, cells were incubated with Flu-R4 at elevated temperatures (37–42 °C) for 30 min in a thermostatically controlled chamber. Although a temperature-dependent increase in uptake was observed, the amount of internalized Flu-R4 was highest under MW irradiation, despite the MW-irradiated samples reaching only 32 °C. These findings indicate that the enhanced cellular uptake of Flu-R4 arises from MW-specific effects beyond simple thermal effects (Figure S6). Such MW-specific effects may arise from unique thermal distributions induced by MWs, as well as possible non-thermal effects associated with MW irradiation. MW irradiation may induce subtle perturbations in cellular structures, thereby facilitating the entry of peptides [24]. Because the confocal microscopy images suggested that Flu-R6 underwent nuclear translocation after cellular uptake, we also examined whether MW irradiation affected the nuclear entry of Flu-R4 and Flu-R6. Nuclear extracts were prepared from peptide-internalized cells following MW irradiation and analyzed for peptide-derived fluorescence (Figure S7). No significant increase in nuclear fluorescence was observed for either peptide, indicating that MW irradiation barely affects nuclear translocation.

Figure 3.

Quantification of peptides internalized into HeLa cells. Quantification of internalized (red) Flu-R4 and (blue) Flu-R6 into cells under MW irradiation at 10 W for 30 min. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation from three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. For Flu-R4 and Flu-R6, two-tailed Student’s t-test was used to compare conditions with and without MW irradiation (n.s.: not significant).

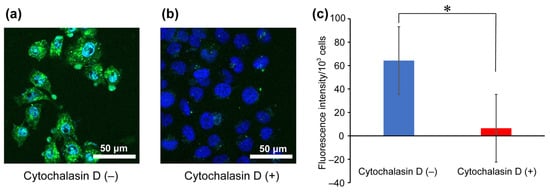

To investigate the uptake pathway of arginine-rich peptides under MW irradiation, an endocytosis inhibition assay using cytochalasin D was performed on Flu-R4, which exhibited the greatest increase in cellular uptake upon MW exposure as observed by confocal fluorescence microscopy (Figure 4). Cytochalasin D is known to inhibit macropinocytosis, a characteristic endocytic pathway involved in the cellular uptake of arginine-rich peptides. Macropinocytosis is an action-driven, fluid-phase endocytic process. Interactions between arginine-rich peptides and the cell surface induce actin reorganization, which promotes membrane protrusion and leads to membrane ruffling. Subsequent membrane fusion results in the formation of lipid vesicles, termed macropinosomes, which internalize surrounding solutes and substances adsorbed on the cell surface. Although arginine-rich peptides exhibit strong adsorption to the cell surface, those bound peptides are efficiently engulfed into macropinosomes and subsequently transported into the cell. Confocal fluorescence microscopy revealed that peptide-derived fluorescence was nearly absent in the cells under cytochalasin D treatment. Furthermore, quantitative fluorescence analysis confirmed a significant decrease in internalized Flu-R4 in the presence of the inhibitor. The enhanced peptide-derived fluorescence observed under MW irradiation could arise either from intracellular uptake of the peptide or from peptide–membrane interactions resulting in peptide retention on the cell surface. Cytochalasin D is known to bind to cytoplasmic F-actin and inhibit actin polymerization. Therefore, if the peptides remained associated with the cell membrane rather than being internalized, peptide-derived fluorescence would be expected to be observed even in the presence of cytochalasin D. These results suggest that Flu-R4 is internalized into cells under MW irradiation through a macropinocytosis-dependent pathway.

Figure 4.

Endocytosis inhibition assay. Confocal laser scanning microscopy images show HeLa cells following the uptake of Flu-R4 under MW irradiation at 10 W for 30 min in the absence (a,b) presence of cytochalasin D. Nuclei were stained blue with Hoechst 33342, and green fluorescence represents internalized Flu-R4. (c) Quantification of internalized Flu-R4 into cells under MW irradiation at 10 W for 30 min in the absence (blue) or presence (red) of cytochalasin D. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation from three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. Two-tailed Student’s t-test was used to compare conditions with and without cytochalasin D (* p < 0.05).

Fetal bovine serum at concentrations of 5–10% is included in standard cell culture. However, it is well established that arginine-rich peptides interact with serum proteins such as albumin when serum is present. These interactions substantially reduce the free, unbound fraction of peptides in the culture medium, and the proportion of unbound peptides decreases as the serum concentration increases. Under conditions containing 10% serum, the unbound fraction is only 25% of the total peptide [7]. As the unbound fraction decreases, cellular internalization of the peptide is markedly reduced. Consequently, arginine-rich peptides are often used in serum-free medium to achieve efficient intracellular delivery. However, in vivo environments are far more complex, containing not only serum but also numerous other biomolecules. Therefore, to enable successful clinical or in vivo applications, it is essential to develop methods that enhance the intracellular delivery of arginine-rich peptides under conditions that mimic the in vivo environment. To address this challenge, we investigated the effect of MW irradiation on the cellular uptake of arginine-rich peptides in the presence of 10% serum. The peptides (5–20 μM) were added to HeLa cells in serum-containing medium and subsequently subjected to MW irradiation at 10 W for 15 min. Internalized peptides were observed using confocal fluorescence microscopy (Figure S8). Although MW irradiation barely enhanced Flu-R4 uptake, MW irradiation increased fluorescence for Flu-R6 and Flu-R8 at 5 and 10 μM, suggesting enhanced uptake. Because the free, unbound fraction of peptides was reduced in serum-containing media, the effective peptide concentration was likely insufficient for Flu-R4, which inherently exhibited the lowest uptake efficiency among the peptides tested. As a result, no enhancement effect was observed for Flu-R4. The observed enhancement in Flu-R6 and Flu-R8 uptake may arise from not only the MW-induced modulation of the cell membrane, but also changes in the interactions between peptides and serum proteins. Next, a cell viability assay was performed for cells after Flu-R6 uptake in serum-containing medium. The viability after Flu-R6 uptake under MW irradiation was 99.4%, indicating minimal cytotoxicity under the conditions tested (Figure S9). Taken together, both confocal fluorescence microscopy and cell viability analyses suggested that MW irradiation enhances the intracellular delivery of arginine-rich peptides without cytotoxicity, even under serum-containing conditions, where the conventional uptake of arginine-rich peptides is typically suppressed. Finally, we attempted to quantify Flu-R6 in the serum-containing condition. However, no significant difference was detected between conditions with and without MW irradiation. This may also be partly due to a decrease in the effective concentration of Flu-R6 caused by its adsorption to serum proteins (Figure S10). Future work will focus on further refinement of the peptide quantification method and optimization of the MW irradiation conditions.

4. Conclusions

In the present study, we investigated the cellular uptake of arginine-rich peptides under MW irradiation. Our results suggested that MW irradiation enhanced the uptake of the peptides. Importantly, this enhancement was partially achieved while maintaining high cell viability, although further optimization of peptide quantification methods and irradiation conditions is required. However, elucidation of the mechanisms underlying the MW-assisted enhancement of uptake efficiency, evaluation using cargo-conjugated CPPs, and improvement of delivery efficiency under conditions involving impurities or complex biological matrices remain important issues to be addressed in future studies. In addition, further investigations using cell lines other than HeLa cells, as well as studies on the enhanced delivery of peptides targeting specific cellular organelles, are also warranted. Collectively, these findings suggest that the combination of arginine-rich peptides with MW irradiation is an effective method for achieving more efficient intracellular delivery.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/pr14030497/s1: Figure S1: Microwave irradiation system; Figure S2: HPLC charts for purified peptides; Figure S3: Cell viability of HeLa cells; Figure S4: Phase-contrast microscopy images of HeLa cells; Figure S5: Cell viability of HeLa cells after the uptake of peptides under microwave irradiation at 10 W for 30 min; Figure S6: Quantification of internalized Flu-R4 after microwave irradiation at 10 W for 30 min or incubation at 32–42 °C under nonirradiated conditions; Figure S7: Quantification of internalized Flu-R4 and Flu-R6 into nuclei after microwave irradiation at 10 W for 30 min; Figure S8: Confocal laser scanning microscopy images of HeLa cells after the uptake of 5–20 μM peptides under serum-containing conditions; Figure S9: Cell viability of HeLa cells after the uptake of Flu-R4 in serum-containing medium under microwave irradiation at 10 W for 15 min; Figure S10: Quantification of internalized Flu-R6 into cells under microwave irradiation at 10 W for 15 min in serum-containing medium.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.N. and K.U. methodology, M.H., Y.A., R.O., M.I., T.E. and N.N.; validation, F.K., T.K. and K.U.; investigation, M.H. and T.K.; writing—original draft preparation, F.K.; writing—review and editing, F.K., M.I., T.E. and K.U.; visualization, F.K. and T.K.; funding acquisition, K.U. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported in part by the JST CREST (JPMJCR21B2) and Konan University Research Institute.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank M. Komada, R. Kawatahara, H. Hatori (Konan University, Kobe, Japan), K. Minaki (DSP Research, Inc., Kobe, Japan), and T. Uraka (Minato Medical Science Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan) for valuable discussions and generous support.

Conflicts of Interest

Ryuji Osawa was employed by Seiko Giken Co., Ltd., and Nobuhiro Nakanishi was employed by DSP Research, Inc. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The company had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Gori, A.; Lodigiani, S.; Colombarolli, S.G.; Bergamaschi, G.; Vitali, A. Cell penetrating peptides: Classification, mechanisms, methods of study, and applications. ChemMedChem 2005, 18, e202300236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milletti, F. Cell-penetrating peptides: Classes, origin, and current landscape. Drug Discov. Today 2012, 17, 850–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Futaki, S.; Nakase, I. Cell-surface interactions on arginine-rich cell-penetrating peptides allow for multiplex modes of internalization. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 2449–2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowski, A.M.; Ensign, M.A.; Maisel, K. Cell-penetrating peptides as facilitators of cargo-specific nanocarrier-based drug delivery. Nanoscale 2025, 17, 20006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desale, K.; Kuche, K.; Jain, S. Cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs): An overview of applications for improving the potential of nanotherapeutics. Biomater. Sci. 2021, 9, 1153–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reissmann, S. Cell penetration: Scope and limitations by the application of cell-penetrating peptides. J. Pept. Sci. 2014, 20, 760–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toshihide, M.; Takeuchi, T.; Nakase, I.; Jones, A.T.; Futaki, S. Cellular internalization and distribution of arginine-rich peptides as a function of extracellular peptide concentration, serum, and plasma membrane associated proteoglycans. Bioconjugate Chem. 2008, 19, 656–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Bing, T.; Li, X.; Zhu, L.; Wen, S.; Chen, G.; Yu, Y. Ultrasound-triggered cascade delivery via Poly-oxaliplatin nanoparticles for immunotherapy. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2425565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Shen, M.; Bing, T.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Cai, Q.; Yang, X.; Yu, Y. A bioactive injectable hydrogel regulates tumor metastasis and wound healing for melanoma via NIR-light triggered hyperthermia. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2402208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, W.; Ye, B.; Yu, G.; Huang, F.; Mao, Z. Stimuli-responsive supramolecular biomaterials for cancer theranostics. Adv. Sci. 2026, 13, e15860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Hoz, A.; Díaz-Ortiza, Á.; Moreno, A. Microwaves in organic synthesis. Thermal and non-thermal microwave effects. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2005, 34, 164–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horikoshi, S.; Watanabe, T.; Narita, A.; Suzuki, Y.; Serpone, N. The electromagnetic wave energy effect(s) in microwave–assisted organic syntheses (MAOS). Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 5151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, H.; Kashimura, K.; Fujii, T.; Tsubaki, S.; Wada, Y.; Fujikawa, S.; Sato, T.; Uozumi, Y.; Yamada, Y.M.A. Production of bio hydrofined diesel, jet fuel, and carbon monoxide from fatty acids using a silicon nanowire array-supported rhodium nanoparticle catalyst under microwave conditions. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 2148–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, S.L.; Tofteng, A.P.; Malik, L.; Jensen, K.J. Microwave heating in solid-phase peptide synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 1826–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, J.M.; Singh, S.K.; White, T.A.; Cesta, D.J.; Simpson, C.L.; Tubb, L.J.; Houser, C.L. Total wash elimination for solid phase peptide synthesis. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 8168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchen, H.J.; Vallance, S.R.; Kennedy, J.L.; Tapia-Ruiz, N.; Carassiti, L.; Harrison, A.; Whittaker, A.G.; Drysdale, T.D.; Kingman, S.W.; Gregory, D.H. Modern microwave methods in solid-state inorganic materials chemistry: From fundamentals to manufacturing. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 1170–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wojnarowicz, J.; Chudoba, T.; Lojkowski, W. A review of microwave synthesis of zinc oxide nanomaterials: Reactants, process parameters and morphologies. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usui, K.; Ozaki, M.; Hirao, K.; Kosaka, T.; Endo, N.; Yoshida, S.; Yokota, S.; Arimoto, Y.; Osawa, R.; Nakanishi, N.; et al. Effect of linearly polarized microwaves on nanomorphology of calcium carbonate mineralization using peptides. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 12027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayamori, F.; Togashi, H.; Endo, N.; Ozaki, M.; Hirao, K.; Arimoto, Y.; Osawa, R.; Tsuruoka, T.; Imai, T.; Tomizaki, K.-Y.; et al. Development of a CaCO3 precipitation method using a peptide and microwaves generated by a magnetron. Processes 2024, 12, 1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicheł, A.; Skowronek, J.; Kubaszewska, M.; Kanikowski, M. Hyperthermia–description of a method and a review of clinical applications. Rep. Pract. Oncol. Radiother. 2007, 12, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamis, Y.; Taube, A.; Mitik-Dineva, N.; Croft, R.; Crawford, R.J.; Ivanova, E.P. Specific electromagnetic effects of microwave radiation on Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 3017–3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.H.P.; Shamis, Y.; Croft, R.J.; Wood, A.; Mclntosh, R.L.; Crawford, R.J.; Ivanova, E.P. 18 GHz electromagnetic field induces permeability of Gram-positive cocci. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 10980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.H.P.; Pham, V.H.; Baulin, V.; Croft, R.J.; Crawford, R.J.; Ivanova, E.P. The effect of a high frequency electro-magnetic field in the microwave range on red blood cells. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, P.G.T.; Nguyen, T.H.P.; Dekiwadia, C.; Wandiyanto, J.V.; Sbarski, I.; Bazaka, O.; Crawford, R.J.; Croft, R.J.; Ivanova, E.P. Exposure to high-frequency electromagnetic field triggers rapid uptake of large nanosphere clusters by pheochromocytoma cells. Int. J. Nanomed. 2018, 13, 8429–8442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.; Schüßler, M.; Hessinger, C.; Schuster, C.; Bertulat, B.; Kithil, M. Microwave induced electroporation of adherent mammalian cells at 18 GHz. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 78698–78705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milden-Appel, M.; Paravicini, M.; Milden, J.P.; Schüßler, M.; Jakoby, R.; Cardoso, M.C. Uptake of substances into living mammalian cells by microwave induced perturbation of the plasma membrane. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 20885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazinani, S.A.; Stuart, J.A.; Yan, H. Microwave-assisted delivery of an anticancer drug to cancer cells. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 31465–31470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, W.C.; White, P.D. Fmoc Solid Phase Peptide Synthesis; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Futaki, S.; Suzuki, T.; Ohashi, W.; Yagami, T.; Tanaka, S.; Ueda, K.; Sugiura, Y. Arginine-rich peptides. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 5836–5840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.