Abstract

Copper(II) coordination complexes with coumarin-derived heterocyclic ligands are promising in inorganic therapeutics for anticancer and antimicrobial applications. To establish quantitative structure–activity relationships for lead design, we studied six copper(II) complexes (Cu1–Cu6)with four- and five-coordinate geometries using Density Functional Theory, Conceptual Density Functional Theory, and visualization analyses. Geometry optimization at M06/6-31G(d)+DZVP revealed distorted coordination environments from Jahn–Teller effects. Tridentate -chelatedcomplexes (Cu4–Cu6) showed greater aqueous stability ( to kcal·mol−1) than four-coordinate analogs ( to kcal·mol−1). CDFT global descriptors contrasted reactivity: four-coordinate Cu1–Cu2 had higher electron affinity (>4.2 eV) and electrophilicity (>5.7 eV), suggesting propensity for redox cycling and for undergoing nucleophilic attack by DNA bases, whereas Cu4–Cu6 displayed increased chemical hardness (3.43–3.54 eV) and lower electrophilicity (≈3.8 eV), implying enhanced kinetic stability and bioavailability. Frontier orbital analysis indicated ligand-to-metal charge transfer via a LUMO delocalized over the -conjugated coumarin, facilitating intercalation by - stacking. The visualization showed strong covalent bonds (blue isosurfaces) stabilizing the metal and dispersive interactions (green surfaces) on the ligand, enabling solvent interactions and biomolecular recognition. Tridentate coordination thus balances electronic stability and biological reactivity, making Cu4–Cu6 promising for further study.

1. Introduction

Copper(II) coordination complexes have emerged as a promising area of inorganic therapeutics, often showing better effectiveness than traditional platinum-based chemotherapy drugs, while also having less toxicity and better compatibility with biological systems [1]. The improved therapeutic potential stems from copper’s inherent redox activity. This allows for various biological effects through the conversion between Cu(II) and Cu(I) oxidation states, along with the ability to create reactive oxygen species (ROS) and interact with important cellular molecules [2]. The utility of copper as a core metal ion is significantly enhanced through the strategic choice of organic ligands. These ligands can be precisely adjusted to influence coordination geometry, electronic structure, lipophilicity, and cell membrane permeability. These factors directly affect both bioavailability and the mechanism of action [3].

In copper coordination chemistry, a variety of ligand systems are used. Heterocyclic ligands that have nitrogen and oxygen donor atoms are especially useful for achieving specific biological effects [4]. Chelating groups, which are made of azomethine nitrogen and carbonyl oxygen atoms, allow for the creation of stable and well-defined coordination geometries. At the same time, these groups offer additional functionality because of their aromatic or conjugated backbone structures. When -conjugated groups are incorporated into these ligand structures, like those found in coumarin-based systems, the resulting metal complexes show improved electronic properties [5]. These properties can facilitate the formation of extended -systems that can intercalate DNA, increase lipophilicity to improve membrane permeability, and adjust the redox potential of the metal center. The combination of electronic properties and structural diversity in heterocyclic ligand systems has made them essential tools in medicinal inorganic chemistry, particularly for developing new metal-based drugs [6].

The biological effectiveness of copper(II) complexes is closely related to their coordination geometry. This geometry determines their electronic structure, redox behavior, and reactivity. Copper(II) complexes with four coordination sites usually have either square planar or distorted tetrahedral shapes. The specific geometry depends on the properties of the ligands. In contrast, complexes with five coordination sites show either square pyramidal or trigonal bipyramidal geometries [7]. These geometric alterations are not merely structural anomalies; they significantly affect the stability of the complex, its capacity to engage with enzymatically active sites, its tendency to bind DNA via intercalation or other mechanisms, and the availability of coordination sites for substrate or solvent molecules [8]. The inherent instability of tetrahedral Cu(II) complexes, arising from their electron configuration and the Jahn–Teller effect, often leads to distortion toward square planar or intermediate geometries. This characteristic can be exploited to fine-tune their reactivity. Furthermore, the introduction of water molecules or other small ligands in five-coordinate systems creates pseudo-octahedral arrangements. This can facilitate reversible ligand exchange kinetics and environment-responsive properties, which are crucial for prodrug activation mechanisms [9].

Copper complexes can exert anticancer activity through multiple, often synergistic, mechanisms, and their effects go beyond causing oxidative damage. Topoisomerase inhibition is a crucial mechanism. Copper complexes bind to topoisomerase–DNA adducts, preventing the rejoining of cut DNA strands. In addition to these protein-targeting pathways, copper complexes undergo redox cycling within cells. Specifically, Cu(II) is reduced to Cu(I) by endogenous glutathione or other reducing agents. This is followed by a quick reoxidation process under aerobic conditions, which produces superoxide anions and hydroxyl radicals. These radicals can then cause widespread DNA damage, RNA oxidation, and mitochondrial dysfunction [10,11]. Furthermore, numerous copper complexes exhibit a strong propensity to bind to DNA via noncovalent interactions. These interactions encompass intercalation within the DNA helix and electrostatic interactions with the phosphate backbone. These properties are significantly amplified when the complex incorporates extended -conjugated systems, which facilitate stacking interactions [12].

Similarly to their redox-based mechanisms, the antimicrobial and antioxidant properties of copper(II) complexes are also due to their direct interactions with microbial cell membranes and essential proteins. When redox cycling occurs, it generates reactive oxygen species (ROS), which cause significant oxidative stress in microbial cells. This stress then leads to the peroxidation of membrane lipids, protein denaturation, and permanent DNA damage. The efficacy of these effects is significantly heightened when the copper ion is bound to ligands that facilitate cellular absorption, elevate the local concentration at the site of action, or synergistically contribute their own biological characteristics. This is illustrated by coumarin-based ligands, which exhibit inherent antimicrobial and antioxidant properties that are amplified upon complexation with copper [13,14]. Coumarin derivatives have long been recognized as important structures in medicinal chemistry. This is because they are found in many bioactive compounds in nature. They can also undergo reversible redox reactions with reactive oxygen species (ROS). Additionally, they have good pharmacokinetic properties, including water solubility and easy absorption upon appropriate modification [15,16].

Therefore, the careful design of copper complexes with coumarin-based heterocyclic ligands offers a powerful approach to the synthesis of therapeutically beneficial compounds. These compounds would have adjustable coordination shapes, improved electronic properties, and multiple biological activities. The combination of Cu(II)’s redox activity, the structural variety and chelation ability of heterocyclic ligands, the extended conjugation and electronic properties of coumarin chromophores, and the inherent biological activity of the organic ligand scaffold creates a synergistic platform [17]. This platform allows for the rational design of highly effective anticancer, antimicrobial, and antioxidant agents. The coordination geometry of these complexes, which can be tetrahedral, square planar, or pentacoordinate, greatly influences their physical properties, their absorption in the body, their mechanism of action, and their effectiveness as treatments. Therefore, understanding their structure and optimizing their geometry are crucial for finding and developing promising compounds [18].

In addition to experimental methods, computational approaches have become essential in modern inorganic drug discovery. They offer molecular-level mechanistic insights that are difficult to obtain from experiments alone, and they enable the rational optimization of lead compounds before they are made. Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations offer a cost-effective and precise method for predicting the ground-state geometries, frontier orbital energies, and electronic structures of copper(II) coordination compounds [19,20]. This approach enables researchers to establish quantitative structure–activity relationships and to clarify how minor alterations in ligand substitution patterns affect redox potentials, highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO)–lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) gaps, and coordination environment parameters [21]. These predictions significantly accelerate the discovery and development of new compounds, while also reducing the number of compounds that need to be synthesized [22].

Figure 1 shows the molecular structures of the copper complexes studied in this research (Cu1–Cu6). In all instances, the copper ion is coordinated by two terminal chloride ligands and by donor atoms from the organic structure, primarily nitrogen and oxygen. This results in distorted coordination geometries typical of this class of compounds. The Cu1, Cu2, and Cu4 complexes exhibit four-coordinate environments defined by a donor set of nitrogen and oxygen atoms, along with two chloride ions. In contrast, Cu3 has a water molecule coordinated to it, resulting in a five-coordinate structure. In Cu5 and Cu6, the metal ion is held in place by nitrogen binding. This creates a tridentate platform. Along with two chloride ions, this arrangement forms a five-coordinate Cu center. The electronic structure and reactivity, which will be discussed later, are expected to be affected by combining -conjugated groups, such as those found in coumarin, with chelating sites containing heteroatoms.

Figure 1.

Ball-and-stick representations of the copper(II) complexes investigated in this work (Cu1–Cu6). Atom color code: Cu (orange), Cl (green), O (red), N (blue), S (yellow), C (cyan), and H (gray).

2. Methods

All calculations were performed using the Gaussian 16 software [23]. Density Functional Theory (DFT) [24,25] was used to find the lowest-energy molecular structures, harmonic vibrational frequencies, frontier molecular orbital (FMO) energy levels, and Conceptual DFT (CDFT) reactivity descriptors for the complexes being studied. Visual Molecular Dynamics (VMD) [26] was used specifically to visualize volumetric data generated by the Multifunctional Wavefunction Analyzer (Multiwfn) 3.8 software package [27,28], including Interaction Region Indicator (IRI) isosurfaces. Although VMD is widely recognized for molecular dynamics and protein visualization, it is also the standard and recommended tool for rendering complex three-dimensional real-space function analyses produced by Multiwfn. VMD provides enhanced capabilities for handling and mapping these quantum chemical isosurfaces. The molecular structures and molecular orbital density were generated using Chemcraft 1.8 software [29]. The M06 hybrid meta-Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA) functional [30] was used for all the calculations. The 6-31G(d) basis set was used for the chlorine, oxygen, nitrogen, sulfur, carbon, and hydrogen atoms [31]. In contrast, the copper atom was described using the double-zeta valence polarized (DZVP) basis set [32,33]. We chose the M06 global hybrid functional because it performs especially well for transition-metal chemistry. M06 includes some Hartree–Fock exchange and is carefully tuned to capture medium-range electron correlation energies. This is important for describing non-covalent interactions, like -stacking in the coumarin ligand system and the dispersion forces that help stabilize the coordination sphere [30]. The DZVP basis set was selected for copper due to its specific optimization for Density Functional Theory calculations involving transition metals, ensuring an accurate representation of the d-orbitals. The 6-31G(d) basis set was applied to light atoms to balance computational efficiency with sufficient accuracy in describing ligand geometry. Due to the electronic configuration of the copper(II) ion, all geometry optimizations and property calculations employed the Unrestricted formalism to accurately represent the open-shell character of the metal center. A spin multiplicity of a doublet state was assigned to each complex. The reliability of the electronic description was evaluated by assessing spin contamination through the expectation value of the spin squared operator, . The calculated values for all complexes were approximately 0.75, deviating by less than 0.002 from the exact value. These results confirm that the ground states are pure doublets and that spin contamination is negligible within this theoretical framework. Water solvent effects were included using the Solvation Model based on Density (SMD) [34]. This model was used to estimate solvation free energies (). Although this approach offers a reliable continuum representation of solvent effects, it characterizes thermodynamic solvation rather than dynamic pharmacokinetic behavior. The model does not explicitly consider ligand exchange kinetics, hydrolytic stability, or the effects of counterions and protonation equilibria, all of which are critical in physiological environments.

Conceptual Density Functional Theory (CDFT) has been proven to be a useful method for predicting chemical reactivity [35]. This is done by using response functions that are related to changes in electron numbers and the external potential. Using this method, we can find values like electron affinity (A) and ionization potential (I) from total-energy calculations [36]. This is done by treating the energy E as a function of the number of electrons N. We then use a smooth quadratic interpolation between the energy values at , , and .

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Molecular Structure

The molecular structures of the copper(II) complexes (Cu1–Cu6) were optimized using the M06/6-31G(d)+DZVP level of calculation, and the resulting structures are shown in Figure 1. Table 1 summarizes the relevant geometric parameters, including the selected bond lengths and bond angles.

Table 1.

Selected bond lengths (Å) and bond angles (degrees, °) for the Cu1–Cu6 copper complexes.

The Cu1 and Cu2 complexes have a four-coordinate environment. In these complexes, the copper ion is bonded to the chelating organic ligand through nitrogen and oxygen atoms. This coordination is completed by the addition of two chloride ions. Table 1 shows the bond lengths for the atoms around Cu1. The Cu1-N4 bond is 2.018 Å, and the Cu1-O3 bond is 2.124 Å. In contrast, the Cu1-Cl distances are 2.283 Å and 2.235 Å. The bond angles surrounding the metal center, specifically N4-Cu1-Cl7 (151.5°) and N4-Cu1-Cl2 (97.8°) within Cu1, exhibit considerable divergence from the idealized 109.5° of a tetrahedral arrangement or the 180° of a square planar configuration, thereby suggesting a notably distorted tetrahedral geometry. A comparable distortion is evident in Cu2; despite exhibiting similar bond lengths (Cu1-N4 at 2.006 Å), its angular configuration (Cl7-Cu1-Cl2 at 155.9°) differs, implying a transition toward a more planar structure relative to Cu1. In contrast to the four-coordinate species, the Cu3 complex has a five-coordinate structure formed by coordination of a water molecule. The addition of this aqua ligand results in a Cu1-O10 bond length of 2.074 Å (Table 1). This completes a coordination sphere that also includes the chelating ligand and two chloride ions.

The copper complexes Cu4, Cu5, and Cu6 exhibit an interesting structural pattern involving tridentate coordination. The computational data in Table 1 indicate a five-coordinate environment. This environment is defined by a donor set from the organic ligand (N8, N12, O5) and two chloride ions (Cl2, Cl3). Notably, Cu4 shows a significant Jahn–Teller distortion [37], which is seen in the elongation of one Cu-Cl bond (Cu1-Cl3) to 2.497 Å, compared to the equatorial Cu1-Cl2 bond, which measures 2.269 Å. The 4 + 1 coordination mode is also seen in Cu5 and Cu6, which have similar tridentate chelating structures. Cu5 shows Cu-N bond lengths of 2.012 Å (N8) and 2.064 Å (N12), along with a similarly long chloride bond (2.497 Å).

For the convenience of readers, the coordinates of the molecular structures of the studied systems are included in the Supplementary Materials to ensure access to all information.

3.2. Solvation Free Energies

The way metal complexes interact with their solvent environment is a key factor in determining their stability and potential for biological activity. The calculated values serve as indicators of aqueous stability from a thermodynamic perspective. These values establish a baseline for understanding the energetic preference of the complexes in water; however, they should not be directly equated with biological performance or pharmacokinetic profiles. Additional factors, including explicit water coordination and local chemical interactions in vivo, may further influence the suitability of drug delivery beyond the scope of a bulk thermodynamic model. Solvation free energies () were determined using the Solvation Model based on Density (SMD), which incorporates both bulk electrostatic polarization and short-range non-electrostatic interactions, including cavitation, dispersion, and solvent structural effects. The values presented in Table 2 were calculated as the difference between the total free energy of the complex in the aqueous phase and its total energy in the gas phase [34], as described by the following equation:

Table 2.

Solvation free energies () of the copper(II) complexes.

denotes the self-consistent field (SCF) energy obtained from full optimization in water, including non-electrostatic terms provided by the SMD model. represents the SCF energy of the optimized structure in vacuum.

The computed values span from −29.07 to −50.00 kcal/mol across all examined systems. The four-coordinate complexes Cu1, Cu2, and Cu3 show moderate solvation energies, specifically −31.54, −29.07, and −30.99 kcal/mol, respectively. In contrast, the complexes with tridentate ligands (Cu4, Cu5, and Cu6) show much more negative values of −48.98, −43.29, and −50.00 kcal/mol, respectively (Table 2).

3.3. Chemical Reactivity Parameters

To further clarify the electronic factors influencing the biological activity of the studied systems, we calculated global reactivity descriptors using Conceptual Density Functional Theory (CDFT), a framework for correlating electronic structure with chemical reactivity. This prediction involves different electronic states: a neutral system with N electrons , a cation with electrons , and an anion with electrons . This computational method allows for a direct calculation of the ionization potential and electron affinity. The ionization potential (I) and electron affinity (A) are fundamental to all subsequent descriptors, and they are defined as follows [36]:

Using the I and A values, we calculated the chemical potential () as follows [38]:

Chemical hardness (), a measure of how much electron density changes, is a key concept in the Hard and Soft Acids and Bases (HSAB) principle [39]. It was defined as

The electrophilicity index (), which quantifies the energy stabilization resulting from the most favorable electron acceptance, was then calculated using the following [40]:

This descriptor has been proven helpful in predicting how metal complexes interact with soft biological nucleophiles, leading to covalent complex formation. Additionally, the electroaccepting power () [41], which specifically measures the ability to accept electron charge from external donors, was calculated as

The descriptors of electron affinity (A), chemical hardness (), the electrophilicity index (), and electroaccepting power () are summarized in Table 3. These parameters provide a way to quantitatively connect the electronic structure of the complexes with their tendency to undergo the redox reactions and nucleophilic attacks described earlier.

Table 3.

Chemical reactivity parameters: electron affinity (A), chemical hardness (), electrophilicity index (), and electroaccepting power () of the copper(II) complexes. All values are in .

Table S1 in the Supplementary Materials provides a breakdown of all calculated chemical reactivity parameters. This includes the individual I, A, and intermediate CDFT-derived indices.

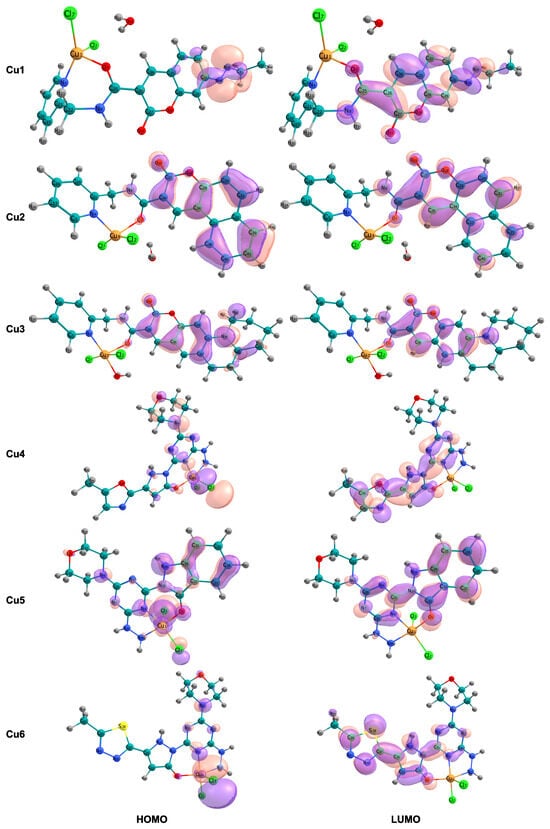

3.4. Frontier Molecular Orbitals

Figure 2 and Table 4 show the frontier molecular orbital energy levels and HOMO-LUMO energy gap of the studied molecular systems (in eV). The HOMO-LUMO energy gap reported in this study represents a fundamental electronic property associated with the chemical hardness and kinetic stability of the complexes in their ground state. This parameter should not be directly equated with the vertical excitation energy or the optical bandgap, as these quantities require consideration of excited-state effects and electron–hole interactions that are not accounted for in ground-state DFT calculations.

Figure 2.

Spatial distribution and localization patterns of the frontier molecular orbitals (FMOs) are presented. The left column illustrates the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO), and the right column depicts the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) for complexes Cu1 to Cu6.

Table 4.

Frontier molecular orbital energy levels and HOMO-LUMO energy gap () of the studied molecular systems (all values in eV).

The HOMO-LUMO energy gaps show considerable disparity across the series, ranging from 3.873 eV (Cu3) to 4.704 eV (Cu5) (Table 4); this approximately 0.8 eV difference indicates notable differences in electronic configuration and reactivity. In contrast to the other complexes, the four-coordinate complexes Cu1 and Cu2 exhibit notably smaller energy gaps of 4.169 and 4.113 eV, respectively, placing them at the lower end of the series. Conversely, the tridentate complexes Cu4, Cu5, and Cu6 display wider HOMO-LUMO gaps, 4.519, 4.704, and 4.215 eV, respectively, which implies enhanced electronic stability and a diminished likelihood of unprompted charge-transfer excitations. The five-coordinate complex Cu3, with an aqua ligand, exhibits the smallest energy gap, 3.873 eV.

The analysis of the frontier molecular orbital compositions, as shown in Figure 2, reveals a consistent pattern of orbital localization across the series. The highest occupied molecular orbitals are primarily localized on the chloride ligands and the copper metal center, indicating a significant d-orbital character of the Cu(II) ion. This localization pattern is consistent with -bonding interactions between the chloride p-orbitals and the copper d-orbitals. These interactions are responsible for the -donation of electron density to the metal center. In contrast, the lowest unoccupied molecular orbitals are mainly spread out across the coumarin-based ligand structure, including the aromatic carbon backbone and its -system.

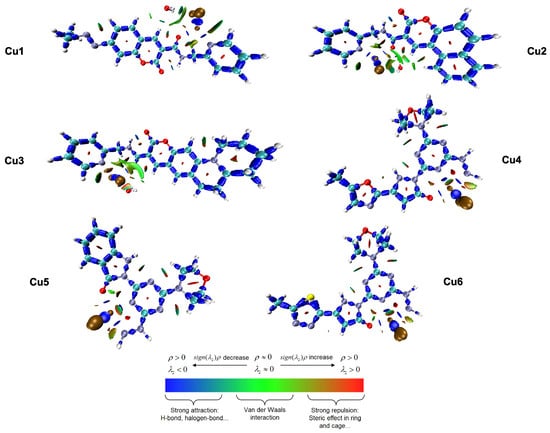

3.5. Interaction Region Indicator Analysis

To visualize and categorize the various interactions, both between and within molecules, that stabilize the copper(II) complexes, the Interaction Region Indicator (IRI) method was used. In contrast to conventional non-covalent interaction (NCI) analysis, the IRI method provides a unified real-space function defined as , capable of simultaneously revealing strong covalent bonds and weak non-covalent interactions within a single graphical representation [42]. Figure 3 shows the IRI isosurfaces for the Cu1–Cu6 complexes. These are mapped using the function to help identify the types of interactions.

Figure 3.

Interaction Region Indicator (IRI) isosurfaces for complexes Cu1–Cu6, illustrating the nature of chemical bonding and non-covalent interactions.

The color-coded isosurfaces provide a complete view of the electronic environment around the metal center. The blue areas, where is less than zero and has a large value, are mainly found along the ligand backbones. They are also notably present around the Cu-N, Cu-O, and Cu-Cl coordination bonds. The consistent presence and strong intensity of these blue isosurfaces confirm the significant coordinate covalent nature of the interactions between the metal and the ligand. This supports the stability of the distorted geometries discussed in Section 3.1. The tridentate complexes (Cu4–Cu6) show a notably high density of these attractive areas.

The green isosurfaces, which represent weak attractive interactions like van der Waals forces and hydrogen bonding (), are particularly important for understanding the biological mechanism. In all the complexes, large green areas are observed, distributed across the planar coumarin-based structures.

3.6. Electronic Structure Analysis via Density of States

The Supplementary Materials (Figures S1–S6) provide comprehensive Density of States analyses for all investigated copper complexes (Cu1-Cu6) using a three-component visualization strategy. The electronic structure of the Cu(II) complexes was further investigated using Total Density of States (TDOS), Partial Density of States (PDOS), and Overlap Population Density of States (OPDOS) analyses with Multiwfn 3.8 software. These methods offer complementary perspectives on orbital energy distributions, fragment-specific contributions, and bonding interactions, thereby extending insights from frontier molecular orbital analysis. For these calculations, each complex was divided into two fragments: Fragment 1 includes the copper center, chloride ligands, and aromatic rings surrounding the copper, representing the metal coordination core, while Fragment 2 comprises the remaining organic ligands derived from coumarin.

The TDOS profiles demonstrate distinct electronic structure patterns across the series. In the four-coordinate complexes Cu1–Cu3, the density of states displays prominent peaks in three regions: (i) valence orbitals between −21.77 and −13.61 eV, primarily associated with ligand orbitals; (ii) a middle-valence region from −10.88 to −5.44 eV with moderate state density; (iii) high-density frontier orbital regions between −5.44 eV and 0.00 eV, corresponding to the HOMO region. In contrast, the tridentate complexes Cu4–Cu6 exhibit enhanced state density in the frontier orbital region and a more continuous distribution of states across the valence manifold. This variation reflects the presence of an additional coordination site and extended -conjugation pathways provided by the tridentate chelation mode. The TDOS curves for Cu4–Cu6 display sharper features near the HOMO energy, indicating more localized electronic states at the frontier relative to the four-coordinate complexes.

The PDOS analysis identifies the spatial origin of electronic states across various energy ranges. In all complexes, Fragment 1 contributes predominantly in two regions: valence orbitals below −13 eV, primarily reflecting Cl 3s and 3p character, and occupied orbitals near the HOMO (−5.44 to 0.00 eV), where copper 3d character is most significant. This distribution aligns with the HOMO localization shown in Figure 2, where electron density is concentrated on the metal center and chloride ligands. Fragment 2 exhibits major PDOS contributions in the middle-valence region (−10.88 to −5.44 eV) and in the virtual orbital manifold (above 0.00 eV). For Cu1 and Cu2, ligand PDOS peaks at approximately −8.16 eV correspond to -bonding orbitals of the coumarin chromophore. In contrast, the tridentate complexes Cu4–Cu6 show increased ligand PDOS in the frontier region (−5.44 to −2.72 eV), indicating stronger metal–ligand orbital mixing due to the additional nitrogen donor in the tridentate chelating motif.

Quantitative analysis shows that in Cu1, Fragment 1 accounts for approximately 65–70% of the states between −5.44 and −2.72 eV, while Fragment 2 contributes 30–35%. In Cu4–Cu6, this distribution shifts to 55–60% (Fragment 1) and 40–45% (Fragment 2), reflecting more balanced metal–ligand electronic delocalization in the tridentate systems. The OPDOS curves directly characterize bonding and antibonding interactions between the metal coordination core and the organic ligand framework. Positive OPDOS values correspond to bonding character, indicating constructive orbital overlap, whereas negative values denote antibonding interactions.

In the virtual orbital region (above 0.00 eV), all complexes exhibit predominantly negative OPDOS values, indicating antibonding character. This antibonding signature in the LUMO and higher virtual orbitals accounts for the observation that electron excitation to these states would weaken metal–ligand interactions and may facilitate ligand dissociation or redox processes in biological environments.

4. Discussion

4.1. Structural and Geometric Implications

In all cases, the copper(II) center adopts a distorted coordination geometry. This is caused by the spatial limitations of the organic ligands and the electronic properties of the metal ion. For Cu1 and Cu2, the observed divergence from idealized angles suggests a notably distorted tetrahedral geometry. However, the angular configuration differences in Cu2 imply a transition toward a more planar structure relative to Cu1. Regarding Cu3, the addition of a five-coordinate system often increases stability in water, which could affect how quickly the complex undergoes substitution reactions. In the tridentate series, specific structural features, such as the elongation of the Cu-Cl bond in Cu4 (Jahn–Teller distortion), highlight the adaptability of the copper(II) coordination environment. The interaction between the tridentate ligand’s core and the chloride co-ligands gives rise to distorted square-pyramidal geometries. Consequently, these geometries are anticipated to significantly influence the complexes’ biological reactivity.

4.2. Solvation Analysis

The negative values indicate a thermodynamically favorable interaction with water molecules, suggesting that these complexes exhibit adequate solubility for potential biological applications. The observed increase in hydrophilicity, approximately 15–20 kcal/mol, can be attributed to the larger dipole moments and enhanced polarity. This is due to the tridentate coordination and the specific electronic changes in the coumarin-derived structures. From a medicinal chemistry perspective, the increased solvation stability of Cu4–Cu6 suggests they may have greater solubility in water than their four-coordinate counterparts. This characteristic is beneficial for drug delivery and distribution within the body.

4.3. Reactivity and Biological Mechanism

A clear difference in how the structure affects reactivity is seen when comparing the four-coordinate complexes (Cu1, Cu2) with the tridentate, five-coordinate systems (Cu4–Cu6). Cu1 and Cu2 show the highest values for electron affinity (A) and electroaccepting power (). Specifically, the A values are greater than 4.2 eV, and the values are above 8.7 eV. The anticancer properties of copper complexes often depend on the reduction of Cu(II) to Cu(I), which then generates reactive oxygen species (ROS). Therefore, the high electron affinity of Cu1 and Cu2 suggests that these complexes have a strong thermodynamic tendency to accept electrons. These elements could be particularly effective at initiating redox cycling processes within cells.

Chemical hardness () and the electrophilicity index () offer different perspectives on stability and selectivity. Chemical hardness () quantifies the resistance of a chemical system to charge transfer and the deformation of its electron cloud, while the electrophilicity index () is the measure of the stabilization in energy when a system acquires an additional electronic charge from the environment.

Cu1 and Cu2, exhibiting lower hardness values ( ≈ 2.67–2.91 eV), also exhibit notably higher electrophilicity indices ( > 5.7 eV), thereby classifying them as softer, more reactive electrophiles. The Hard and Soft Acids and Bases (HSAB) principle suggests that a soft acid–base character leads to stronger interactions with soft biological nucleophiles. These nucleophiles include the electron-rich nitrogen atoms found in DNA bases and the thiol groups in proteins.

In contrast, the complexes with tridentate ligands (Cu4, Cu5, and Cu6) show a significant increase in chemical hardness ( ≈ 3.43–3.54 eV) and much lower electrophilicity values ( ≈ 3.8 eV) compared to the four-coordinate complexes. This suggests that the tridentate coordination mode provides the metal center with greater electronic stability, thus making these complexes less prone to unwanted charge transfer. Considering the solvation results, which showed that Cu4–Cu6 had much greater hydrophilicity, these reactivity parameters suggest that the tridentate systems have a balanced physicochemical profile. Although Cu1 and Cu2 exhibit significant electronic properties and elevated intrinsic reactivity, Cu4–Cu6 exhibit a distinct behavior, characterized by improved stability and solubility, which are frequently advantageous for ensuring the drug’s unaltered delivery to its biological target.

Although Conceptual DFT descriptors, including the electrophilicity index and chemical hardness, offer valuable insights into the intrinsic electronic reactivity and thermodynamic stability of complexes, these measures have limitations in directly predicting complex biological behaviors. Such static electronic descriptors do not consider steric constraints within specific biomolecular targets, such as enzyme active sites, nor do they account for dynamic conformational changes or competitive ligand-exchange processes in biological environments. Consequently, the biological mechanisms proposed in this study, including specific nucleophilic attacks or intercalation efficiency, should be regarded as electronic predispositions and theoretical hypotheses. Further research, including molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulations, and experimental validation, is necessary to confirm the therapeutic relevance of these electronic trends.

4.4. Frontier Orbital Analysis

The electronic properties of copper(II) complexes are fundamentally determined by the energy levels and spatial distribution of the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO), which are collectively called frontier molecular orbitals (FMOs). These orbitals control the reactivity of these complexes. This is due to their ability to allow electronic excitations and their tendency to participate in charge-transfer interactions with biological molecules such as DNA and proteins. The wider HOMO-LUMO gaps in Cu4, Cu5, and Cu6 imply enhanced electronic stability and a diminished likelihood of unprompted charge-transfer excitations. Conversely, the smallest energy gap in Cu3 suggests it has the highest potential for electronic excitation among the systems studied. This property could be useful for light-driven redox reactions, which are important for photodynamic applications. However, this increased electronic reactivity in Cu3 is accompanied by diminished solvation stability and intermediate chemical hardness. This implies that Cu3 could undergo more rapid degradation or solvation-driven dissociation in biological fluids than the other complexes. Consequently, this characteristic might limit its use as a consistently stable therapeutic compound. The spatial separation between the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO), which is centered on the metal and chloride, and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO), which is centered on the ligand, gives the lowest electronic transitions a metal-to-ligand charge transfer (MLCT) character. This suggests that either photoexcitation or chemical excitation would likely move electrons from the metal center to the organic structure. The presence of this MLCT character has significant implications for biological activity. Because the LUMO is spread out over the extended -conjugated coumarin system, the complex can easily stack with the aromatic bases found in DNA. Small HOMO-LUMO gaps, like those seen in Cu1 and Cu2, 4.113–4.169 eV, allow for electronic excitation at physiological energies. This promotes electron-transfer processes that can cause oxidative damage to DNA. This damage can occur through the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Furthermore, a smaller energy gap correlates with increased electrophilicity, as shown in Table 3 for Cu1 and Cu2, enhancing its susceptibility to nucleophilic attack by DNA bases and protein residues. The favorable solvation properties and reduced electrophilicity of the tridentate complexes (Cu4–Cu6) align with a balance between electronic stability, as indicated by a large energy gap, and biological reactivity, as evidenced by accessible charge transfer states. These findings indicate that Cu4–Cu6 complexes constitute a more biologically relevant structure, optimized for drug delivery and sustained biological activity. The critical role of metal-to-ligand charge transfer (MLCT) transitions in mediating low-energy electronic excitations, in concert with the spatial distribution of frontier molecular orbitals, underscores the multifunctional significance of the coumarin chromophore as a facilitator of the complexes’ interactions with biological macromolecules—functioning simultaneously as both an electron donor and a spatial scaffold for biomolecular recognition. The -conjugated coumarin system functions not only as a passive chelating structure but also as an active participant in charge-transfer processes. This facilitates electronic excitation and the formation of stabilized adducts with DNA, owing to the extended overlap of its -system. This integrated electronic system, which combines metal redox reactions with charge transfer through ligands, exemplifies the combined principles that guide the design of advanced inorganic pharmaceuticals.

4.5. Intermolecular Interactions and Stability

The IRI analysis provides a connection between the geometric and electronic descriptions. The findings confirm that the stability of these complexes is mainly due to strong coordinate covalent bonds (shown in blue). This supports the earlier conclusion, based on the reactivity parameters discussed in Section 3.3, that the chelating mode improves the metal center’s electronic stability. The green isosurfaces are indicative of dispersive -electron interactions, which are crucial for two biological functions: (i) the stabilization of the complex–solvent interface, which corresponds to the favorable solvation energies () discussed in Section 3.2, and (ii) the ligand’s ability to interact through - stacking with DNA base pairs. The visual prominence of these dispersive areas on the coumarin part supports the FMO analysis (Section 3.4). This analysis showed that the LUMO was spread out over the same area. This suggests that the ligand acts as an anchor into the DNA double helix. Furthermore, subtle green, non-continuous surfaces are observed between chloride ions and hydrogen atoms near the organic ligands (C-H···Cl interactions). These weak hydrogen bonds within the molecule help maintain the shape of the distorted coordination spheres, which prevents the ligands from separating before the molecule enters the cell. The red areas seen in the centers of the aromatic rings indicate steric repulsion. This is a typical topological feature of cyclic aromatic systems, which confirms the structural integrity of the coumarin backbone. The results indicate that the stability of these complexes primarily arises from strong coordinate covalent bonds. In contrast, their biological relevance depends on the extensive network of non-covalent, dispersive interaction sites present on the ligand surface.

4.6. Electronic Structure Insights from Density of States Analysis

TDOS, PDOS, and OPDOS analyses offer a comprehensive electronic structure perspective that integrates geometric descriptions, frontier orbital analysis, and reactivity predictions. Whereas frontier orbital energy gaps and spatial distributions elucidate the characteristics of the highest occupied and lowest unoccupied states, DOS analysis reveals the full energy landscape of electronic states and quantifies fragment-specific contributions throughout the valence manifold.

The DOS curves distinctly differentiate the electronic structures of four-coordinate and five-coordinate tridentate complexes. Four-coordinate Cu1–Cu3 display discrete, well-separated peaks in their TDOS, reflecting the localized nature of molecular orbitals when the metal center engages with fewer donor atoms. The relatively low OPDOS values in the frontier region (−5.44 to −2.72 eV) indicate moderate covalent bonding strength, consistent with their higher electron affinity (>4.2 eV) and the softer, more electrophilic character described in Section 4.3.

In contrast, tridentate systems Cu4–Cu6 exhibit broader and more continuous TDOS features, with increased state density near the frontier orbitals. This observation indicates greater orbital mixing and delocalization, facilitated by the presence of an additional nitrogen donor. The significantly higher OPDOS values quantitatively confirm stronger metal–ligand covalent bonding within the coordination framework. This enhanced bonding electronically stabilizes the copper center, reduces its propensity for electron acceptance, and accounts for the decreased electrophilicity ( 3.8 eV) and increased chemical hardness ( 3.5 eV) reported in Table 3.

OPDOS offers unique insight into bonding mechanisms that are inaccessible through conventional bond order calculations or orbital visualization. The presence of positive OPDOS throughout the occupied valence region demonstrates that metal–ligand bonding extends beyond the frontier orbitals, encompassing multiple energy levels and establishing a robust electronic framework that underpins complex stability.

The increased -backbonding observed in tridentate complexes has significant mechanistic implications for their biological activity. Enhanced -backdonation into the coumarin ligand system raises electron density on the aromatic framework, which is expected to strengthen - stacking interactions with DNA bases, a key pathway for intercalation and cytotoxic activity. Concurrently, the stronger covalent bonding decreases the probability of premature ligand dissociation in aqueous biological environments, thereby addressing a major limitation identified for Cu1–Cu3.

5. Conclusions

This computational study establishes the value of integrating Density Functional Theory (DFT), Conceptual Density Functional Theory (CDFT), and real-space visualization techniques to predict the biological activity of metal coordination complexes before synthesis. Analysis of six copper(II)–coumarin complexes (Cu1–Cu6) identifies key structure–activity relationships that connect coordination architecture with thermodynamic stability and reactivity.

The optimized geometries demonstrate a distinct structural dichotomy resulting from the Jahn–Teller effect. The four-coordinate complexes display distorted, flattened geometries, while the tridentate ligand systems impose a stable five-coordinate square–pyramidal geometry. This structural transition serves as the principal physical factor underlying the observed differences in stability. Density of States and frontier molecular orbital analyses clarify the electronic implications of these structural variations. The data indicate that the four-coordinate complexes have a narrower HOMO-LUMO gap and accessible anti-bonding states, which corresponds to lower chemical hardness and higher reactivity. In contrast, the tridentate complexes exhibit a stabilized electronic structure with substantial bonding overlap populations (OPDOS) located deep within the valence band.

The four-coordinate complexes exhibit the highest chemical reactivity, owing to their softer, highly electrophilic character ( eV), which increases their reactivity toward biological nucleophiles. However, this elevated reactivity is associated with decreased aqueous solubility and an increased risk of non-specific side reactions. The tridentate coordination mode offers different characteristics and properties. Through heightened chemical hardness, augmented solvation stability, and a broader HOMO-LUMO gap, these complexes exhibit better properties against premature decomposition.

Using Interaction Region Indicator analysis to visualize interactions between and within molecules provided a new way to understand how strong coordinate covalent bonds and weaker dispersive interactions work together. The prominent green isosurfaces on the coumarin ligand scaffold directly explain the complexes’ ability to solvate well. At the same time, these surfaces provide accessible interaction sites for - stacking with DNA base pairs. This combination of properties is essential for the complexes’ effectiveness as biological therapeutics.

From a medicinal chemistry perspective, these findings suggest that Cu4–Cu6 are the most promising candidates for further development. Their improved solubility in water, increased stability over time, and controlled reactivity make them suitable for both laboratory tests of their ability to kill microbes or cells and, later, for studying how they behave in the body. Future research should focus on creating and testing these tridentate systems. This should include studying how they enter cells, how strongly they bind to DNA, and how well they work against common cancer cell lines and harmful microorganisms.

This research establishes a reusable computational framework to help design new metal-based therapies. Employing a combination of complementary theoretical methodologies, including molecular geometry optimization, global reactivity descriptors, frontier orbital analysis, and real-space interaction visualization, constitutes a robust framework for forecasting the impact of ligand structural alterations (such as substitution patterns, chelation denticity, and the electronic characteristics of donor atoms) on the physicochemical and biological behaviors of metal coordination complexes. Using this systematic approach in the early stages of drug discovery significantly reduces the number of compounds that need to be synthesized. This, in turn, accelerates the process of improving promising compounds and increases the likelihood of identifying compounds useful in clinical settings.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/pr14030498/s1, Table S1. Chemical reactivity parameters (electron affinity, ionization potential, chemical potential, chemical hardness, electrophilicity index, and electroaccepting power) of the molecular systems, calculated with the M06 functional and the 6-31G(d)+DZVP basis sets; Figure S1. Analysis of TDOS, PDOS, and OPDOS of Cu1; Figure S2. Analysis of TDOS, PDOS, and OPDOS of Cu2; Figure S3. Analysis of TDOS, PDOS, and OPDOS of Cu3; Figure S4. Analysis of TDOS, PDOS, and OPDOS of Cu4; Figure S5. Analysis of TDOS, PDOS, and OPDOS of Cu5; Figure S6. Analysis of TDOS, PDOS, and OPDOS of Cu6.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.S.-R. and J.B.-L.; methodology, J.B.-L. and D.G.-M.; validation, R.S.-R., J.B.-L. and D.G.-M.; formal analysis, J.B.-L.; investigation, R.S.-R., J.B.-L. and D.G.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, R.S.-R., J.B.-L. and D.G.-M.; writing—review and editing, R.S.-R., J.B.-L. and D.G.-M.; supervision, J.B.-L. and D.G.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere gratitude to Rodrigo Domínguez of CIMAV for his valuable technical assistance. Rody Soto-Rojo and Jesús Baldenebro-López are affiliated researchers at the Universidad Autónoma de Sinaloa. Daniel Glossman-Mitnik is affiliated researcher at the Centro de Investigación en Materiales Avanzados (CIMAV) and member of the Sistema Nacional de Investigadoras e Investigadores (SNII) of the Secretaría de Ciencia, Humanidades, Tecnología e Innovación (SECIHTI), México.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| DFT | Density Functional Theory |

| CDFT | Conceptual Density Functional Theory |

| FMO | Frontier Molecular Orbital |

| VMD | Visual Molecular Dynamics |

| Multiwfn | Multifunctional Wavefunction Analyzer |

| IRI | Interaction Region Indicator |

| GGA | Generalized Gradient Approximation |

| DZVP | Double-Zeta Valence Polarized |

| SMD | Solvation Model based on Density |

| A | Electron Affinity |

| I | Ionization Potential |

| Solvation Free Energy | |

| Chemical Potential | |

| Chemical Hardness | |

| HSAB | Hard and Soft Acids and Bases |

| Electrophilicity Index | |

| Electroaccepting Power | |

| HOMO | Highest Occupied Molecular Orbital |

| LUMO | Lowest Unoccupied Molecular Orbital |

| HOMO-LUMO Energy Gap | |

| MLCT | Metal-to-Ligand Charge Transfer |

| NCI | Non-Covalent Interaction |

| TDOS | Total Density of States |

| PDOS | Partial Density of States |

| OPDOS | Overlap Population Density of States |

References

- Ashraf, J.; Riaz, M.A. Biological potential of copper complexes: A review. Turk. J. Chem. 2022, 46, 595–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngece, K.; Khwaza, V.; Paca, A.M.; Aderibigbe, B.A. The Antimicrobial Efficacy of Copper Complexes: A Review. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krasnovskaya, O.; Naumov, A.; Guk, D.; Gorelkin, P.; Erofeev, A.; Beloglazkina, E.; Majouga, A. Copper Coordination Compounds as Biologically Active Agents. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, S.A.; Patil, S.A.; Patil, R.; Keri, R.S.; Budagumpi, S.; Balakrishna, G.R.; Tacke, M. N-Heterocyclic Carbene Metal Complexes as Bio-Organometallic Antimicrobial and Anticancer Drugs. Future Med. Chem. 2015, 7, 1305–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateo-Alonso, A. π-Conjugated Materials: Here, There, and Everywhere. Chem. Mater. 2023, 35, 1467–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, T.; Gadadhar, S.; Balaji, B.; Gole, B.; Karande, A.A.; Chakravarty, A.R. Ferrocenyl-l-amino acid copper(II) complexes showing remarkable photo-induced anticancer activity in visible light. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 11988–11999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mautner, F.A.; Fischer, R.C.; Torvisco, A.; Henary, M.M.; Louka, F.R.; Massoud, S.S.; Salem, N.M.H. Five-Coordinated Geometries from Molecular Structures to Solutions in Copper(II) Complexes Generated from Polydentate-N-Donor Ligands and Pseudohalides. Molecules 2020, 25, 3376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masternak, J.; Zienkiewicz-Machnik, M.; Łakomska, I.; Hodorowicz, M.; Kazimierczuk, K.; Nosek, M.; Majkowska-Młynarczyk, A.; Wietrzyk, J.; Barszcz, B. Synthesis and Structure of Novel Copper(II) Complexes with N,O- or N,N-Donors as Radical Scavengers and a Functional Model of the Active Sites in Metalloenzymes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Outlaw, T.C.; Robison, A.T.R.; Schulte, N.B.; Vaccaro, F.A.; Williams, I.G.; Repala, S.; Diaz, D.; Sturrock, G.R.; Fitzgerald, M.C.; Franz, K.J. Copper Activates a Redox Switch to Reversibly Inhibit Glyceraldehyde-3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase. Biochemistry 2025, 64, 4400–4413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahendiran, D.; Amuthakala, S.; Bhuvanesh, N.S.P.; Kumar, R.S.; Rahiman, A.K. Copper complexes as prospective anticancer agents: In vitro and in vivo evaluation, selective targeting of cancer cells by DNA damage and S phase arrest. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 16973–16990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.K.; Kumbhar, A.A.; Pokharel, Y.R.; Yadav, P.N. Anticancer potency of copper(II) complexes of thiosemicarbazones. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2020, 210, 111134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molinaro, C.; Martoriati, A.; Pelinski, L.; Cailliau, K. Copper Complexes as Anticancer Agents Targeting Topoisomerases I and II. Cancers 2020, 12, 2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldabaldetrecu, M.; Parra, M.; Soto, S.; Arce, P.; Tello, M.; Guerrero, J.; Modak, B. New Copper(I) Complex with a Coumarin as Ligand with Antibacterial Activity against Flavobacterium psychrophilum. Molecules 2020, 25, 3183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brahma, U.; Kothari, R.; Sharma, P.; Bhandari, V. Antimicrobial and anti-biofilm activity of hexadentated macrocyclic complex of copper (II) derived from thiosemicarbazide against Staphylococcus aureus. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 8050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezenarro-Salcedo, D.; Fonseca-López, D.; Leal-Pinto, S.M.; Roa-Cordero, M.V.; Vargas-Caicedo, J.D.; Macías, M.A.; Iglesias, B.A.; Piquini, P.C.; Hurtado, J.J. Synthesis, Characterization, and Antimicrobial Activity of Copper(II) Complexes Containing Ligands Derived from Azoles and Coumarins. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2025, 28, e202500118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Megid, M.; Adly, O.M.I.; Ibrahim, M.A.; Fouad, R. Synthesis, structural insights, antimicrobial potency, and theoretical studies of Cu(II), Ni(II), and Cd(II) complexes derived from Coumarin-based 1,2,4-Triazine. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2026, 589, 122893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujahid, M.; Trendafilova, N.; Rosair, G.; Kavanagh, K.; Walsh, M.; Creaven, B.S.; Georgieva, I. Structural and Spectroscopic Study of New Copper(II) and Zinc(II) Complexes of Coumarin Oxyacetate Ligands and Determination of Their Antimicrobial Activity. Molecules 2023, 28, 4560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahfouz, M.S.; Ali, A.A.M.; Shebl, M.; Adly, O.M.I.; Fouad, R. Copper(II) chelates of a coumarin-based acyl hydrazone ligand: Structural characterization and computational evaluations for prospective applications in antimicrobial, antiviral, antioxidant, and anticancer therapies. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 22972–22988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balbuena, P.B.; Derosa, P.A.; Seminario, J.M. Density Functional Theory Study of Copper Clusters. J. Phys. Chem. B 1999, 103, 2830–2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulik, H.J.; Cococcioni, M.; Scherlis, D.A.; Marzari, N. Density Functional Theory in Transition-Metal Chemistry: A Self-Consistent Hubbard U Approach. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 97, 103001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roopashree, B. A Review Study on Computational Insights Into Transition Metal Complex Cytotoxicity in Neurobiology. Dev. Neurobiol. 2026, 86, e23016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kore, S.; Maddikayala, S.; Bengi, K.; Pulimamidi, S.R. DNA Interaction, Molecular Docking, Antimicrobial, Anticancer and Thermal Studies of Ternary Metal Complexes of N-Methylbenzylamine and Ethylenediamine. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2024, 38, e7706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 16, Revision C.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2016; Available online: https://gaussian.com/citation/ (accessed on 27 December 2025).

- Hohenberg, P.; Kohn, W. Inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys. Rev. 1964, 136, B864–B871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, W.; Sham, L.J. Self-consistent equations including exchange and correlation effects. Phys. Rev. 1965, 140, A1133–A1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, W.; Dalke, A.; Schulten, K. VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996, 14, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Chen, F. Multiwfn: A Multifunctional Wavefunction Analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 2012, 33, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T. A comprehensive electron wavefunction analysis toolbox for chemists, Multiwfn. J. Chem. Phys. 2024, 161, 082503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemcraft—Graphical Software for Visualization of Quantum Chemistry Computations. Version 1.8, Build 682, Grigoriy A. Andrienko, Moscow, Russia. Available online: https://www.chemcraftprog.com (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Zhao, Y.; Truhlar, D.G. The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: Two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2008, 120, 215–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rassolov, V.A.; Ratner, M.A.; Pople, J.A.; Redfern, P.C.; Curtiss, L.A. 6-31G* basis set for third-row atoms. J. Comp. Chem. 2001, 22, 976–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godbout, N.; Salahub, D.R.; Andzelm, J.; Wimmer, E. Optimization of Gaussian-type basis sets for local spin density functional calculations. Part I. Boron through neon, optimization technique and validation. Can. J. Chem. 1992, 70, 560–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosa, C.; Andzelm, J.; Elkin, B.C.; Wimmer, E.; Dobbs, K.D.; Dixon, D.A. A local density functional study of the structure and vibrational frequencies of molecular transition-metal compounds. J. Phys. Chem. 1992, 96, 6630–6636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marenich, A.V.; Cramer, C.J.; Truhlar, D.G. Universal Solvation Model Based on Solute Electron Density and on a Continuum Model of the Solvent Defined by the Bulk Dielectric Constant and Atomic Surface Tensions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 6378–6396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geerlings, P.; Proft, F.D.; Langenaeker, W. Conceptual Density Functional Theory. Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 1793–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perdew, J.P.; Parr, R.G.; Levy, M.; Balduz, J.L., Jr. Density-Functional Theory for Fractional Particle Number: Derivative Discontinuities of the Energy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1982, 49, 1691–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahn, H.A.; Teller, E. Stability of polyatomic molecules in degenerate electronic states - I-Orbital degeneracy. P. Roy. Soc. A-Math. Phy. 1937, 161, 220–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parr, R.G.; Donnelly, R.A.; Levy, M.; Palke, W.E. Electronegativity: The density functional viewpoint. J. Chem. Phys. 1978, 68, 3801–3807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gázquez, J.L. A hardness and softness theory of bond energies and chemical reactivity. Theor. Comput. Chem. 1998, 5, 135–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parr, R.G.; Szentpály, L.V.; Liu, S. Electrophilicity Index. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 1922–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gázquez, J.L.; Cedillo, A.; Vela, A. Electrodonating and Electroaccepting Powers. J. Phys. Chem. A 2007, 111, 1966–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Chen, Q. Interaction Region Indicator: A Simple Real Space Function Clearly Revealing Both Chemical Bonds and Weak Interactions. Chem. Methods 2021, 1, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.