Abstract

Banana peel, an abundant by-product rich in bioactive compounds, presents high functional and technological potential. Despite its potential, the industrial use of banana peel is limited by enzymatic browning. Thus, this study proposed an integrated sequential extraction process using Generally Recognized As Safe (GRAS) solvents and simple methodologies. With this approach, it was possible to recover high-value compounds, including (all-E)-lutein (338.05 µg/g DW), pectin (3.81 g/100 g DW), and ferulic acid (212.48 µg/g DW). In addition to maximizing recovery of bioactive compounds, the process preserved the residual lignocellulosic fraction, namely cellulose (23.14 g/100 g DW), hemicellulose (19.91 g/100 g DW), and lignin (29.63 g/100 g DW), suitable for further bioprocesses such as bioethanol production. The strategy demonstrated technological and economic feasibility, reducing operational steps, eliminating the use of chemical agents, and promoting full biomass utilization. The results confirm the potential of banana peel as a platform for obtaining natural and sustainable ingredients, aligned with the principles of biorefinery and the circular bioeconomy.

1. Introduction

Banana (Musa sp.) is recognized as one of the most widely cultivated fruits in the world. According to the FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization), global banana production reached approximately 19.7 million tons in 2024, with Brazilian production estimated at around 7 million tons per year [1]. Of this total, approximately 8 million tons corresponds to peels, considering that peels generally account for about 40% of the fruit’s total weight [2]. Despite its rich composition of fiber, pectin, phenolic compounds, and cell-wall components such as lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose, this by-product is often deposited in landfills, promoting methane emissions and the loss of valuable natural resources [3].

Banana peel stands out as a feedstock for biorefineries due to its low cost and compositional versatility. Recent studies demonstrate its viability, for example, in the production of bioplastics, functional foods, and even second-generation (2G) ethanol [4]. However, 80% of this by-product still has limited applications, being utilized predominantly only in animal feed and fertilizer, highlighting the need for technologies for the selective extraction of soluble compounds or those bound to the lignocellulosic matrix [5]. The banana peel biorefinery faces critical technical challenges. For example, lignin hinders the hydrolysis of polysaccharides and bioactive compounds, such as insoluble phenols, which require acid/alkaline pretreatment steps for their release from the cell wall [6,7]. Overcoming these barriers requires integrated and sustainable processes aimed at sustainability [8].

An integrated process is a central strategy in integrated biorefinery approaches, in which the same biomass is subjected to successive and selective extraction steps, allowing the recovery of different classes of compounds and the efficient utilization of the residual fraction. This approach has been widely applied to the valorization of agro-industrial residues, as it enables the recovery of bioactive compounds and functional ingredients while preserving the lignocellulosic matrix for subsequent conversion processes. In addition to reducing reagent consumption, this strategy minimizes unit operations and enhances the economic and environmental viability of the process [9,10,11,12].

Despite the potential of banana peel as a feedstock, its industrial use may be limited by the dark coloration resulting from enzymatic browning, a phenomenon associated with polyphenol oxidase activity that also contributes to the degradation of soluble phenolic compounds [13]. The high moisture content of fresh banana peel represents another relevant limitation, as it hampers storage and favors microbial deterioration and the degradation of bioactive compounds [14]. For this reason, chemical pretreatments such as metabisulfite, citric acid, and ascorbic acid are commonly applied to preserve the sensory and functional attributes of banana peel. However, the present study adopts an alternative and simplified approach by using dried banana peel (50 °C for 24 h) without any blanching or chemical additives, demonstrating that even with natural browning, it is possible to obtain high–value bioactive compounds. Drying contributes to the reduction in biomass moisture, and the resulting material is consistent with the typical appearance of banana peel in industrial settings, where brown coloration indicates the action of oxidative enzymes on phenolic constituents. This strategy reduces operational costs and enhances the feasibility of by-product valorization, particularly in contexts demanding accessible and sustainable solutions [15,16].

In this scenario, the present research introduces an integrated process for obtaining high-value compounds from banana peel, namely carotenoids, pectin, and insoluble-bound phenolic compounds. Low environmental impact techniques (GRAS solvents) were primarily employed to recover bioactive and technological compounds, thereby promoting residue valorization and exploring their potential for industrial applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Biomass Preparation

Banana fruits of the ‘Prata’ variety (Musa sp., AAB group) (5 kg) were obtained in the municipality of Belém, State of Pará, Brazil (01°28′15″ S latitude, 48°27′32″ W longitude, and 10 m altitude). Only fruits at the fully ripe stage (entirely yellow) were selected for the study. The bananas were manually peeled, and the peels were separated from the pulp. The peels were washed under running water to remove impurities and immersed in a sodium hypochlorite (NaClO) solution at 200 ppm for 30 min, followed by rinsing to remove any residual disinfectant, according to the protocol of Segura-Badilla et al. [17]. Subsequently, the peels (88.12 ± 0.26% of moisture) were dried in an oven at 50 °C for 24 h (until constant weight), milled to reduce particle size (≤1 mm), vacuum-packed in polyethylene bags, and stored at 14 °C, and used within 24 h for subsequent analyses.

2.2. Determination of Extractives (Method A)

The determination of extractives was carried out according to Sluiter et al. [18] with minor modifications. The aim was to quantify the extractives content and prepare the material for subsequent analyses. Extractives were removed using a Soxhlet apparatus, where filter-paper cartridges, previously tarred, were each loaded with 10 g of dried banana peel. Extraction was performed with 200 mL of analytical-grade ethanol until complete decolorization of the sample (approximately 24 h). Upon completion of ethanolic extraction, the samples were washed with distilled water at 100 °C to remove any remaining extractives. Subsequently, the samples were dried in an oven with air circulation at 105 °C until a constant weight was reached. Extractives content was calculated using Equation (1).

2.3. Determination of Lignocellulosic Components

2.3.1. Acid Hydrolysis

The sample used in this step was the extractive-free material (Section 2.2). Extractive-free dried banana peel was subjected to acid hydrolysis with 72% H2SO4 following the methodology described by Sluiter et al. [18]. For the hydrolysis, 0.3 g of extractive-free dried peel was weighed into test tubes, 3 mL of 72% (w/w) H2SO4 was added, and the tubes were immediately placed in a water bath at 30 °C for 1 h, with agitation cycles every 10 min using a vortex mixer. Then, the samples were cooled in an ice bath to halt the hydrolysis. All hydrolyzed content from the test tubes was transferred to 250 mL Schott bottles, and 84 mL of distilled water was added, consequently diluting the sulfuric acid concentration to 4%. The bottles were sealed and autoclaved at 121 °C for 1 h. After depressurization, the Schott bottles were removed, cooled, and their contents were vacuum-filtered using previously tarred filter paper. The residue retained on the filter was dried at 40 °C and used for Klason lignin analysis.

2.3.2. Determination of Insoluble Lignin (Klason Lignin)

The residue from the acid hydrolysis (Section 2.3.1) was washed with approximately 2 L of distilled water until the washing water reached a pH of 7.0, ensuring no filter damage during drying at 105 °C due to residual acid. The filter paper containing the hydrolysis residue was then dried in an oven with air circulation at 105 °C until a constant weight was reached. After drying and weighing, the insoluble residue was used for ash content determination. Part of the insoluble material consists of ash, since ash is not soluble in acid. To avoid overestimating insoluble lignin, ash content was determined in a muffle furnace at 550 °C following the AOAC method 940.26 [19]. The insoluble lignin content was calculated according to Equation (2).

where m1 is the mass of the filter paper with dried insoluble lignin, m2 is the mass of the tarred filter paper, and m3 is the initial sample mass.

2.3.3. Determination of Lignin by Precipitation

Precipitated lignin was obtained following the method described by Huang et al. [20] with minor modifications. For the preparation of black liquor, where lignin precipitation occurs, 1 g of extractive-free dried banana peel (Section 2.2) was mixed with 25 mL of 2 M NaOH solution in a Schott bottle. The mixture was left to stand for 5 min to allow the solution to be absorbed by the sample. The bottle was then autoclaved at 121 °C for 15 min to perform hydrolysis. After depressurization, the bottles were removed, cooled, and the contents were vacuum-filtered using filter paper to obtain the black liquor. Lignin precipitation was induced by adjusting the liquor pH to 1.5 with 2 M HCl. The acidified liquor was refrigerated at 4 °C for approximately 16 h. The precipitated lignin was separated by centrifugation, yielding a gelatinous precipitate. To reduce moisture, the precipitate was dried in an oven with air circulation at 60 °C. Due to the sticky texture of the precipitated lignin, it was transformed into powder by dehydration with ethyl acetate for 120 h, at room temperature and in a closed system. After recovery, the powder was dried again in an oven with air circulation to ensure complete solvent evaporation. The precipitated lignin content was calculated according to Equation (3).

2.3.4. Determination of Hemicellulose

Hemicellulose quantification was performed using extractive-free material (Section 2.2). An aliquot of 1 g of extractive-free dried banana peel was treated with 150 mL of 0.5 M NaOH solution and maintained at 80 °C for 3.5 h. After this period, the sample was filtered and repeatedly washed with distilled water until the filtrate pH reached approximately 7, indicating the absence of residual ions. The solid residue was then oven-dried to constant weight. Hemicellulose content was calculated based on the mass difference between the initial sample and the final residue, considering the solubilized fraction as representative of hemicellulose content, following the methodology of Yang et al. [21] and Equation (4).

2.3.5. Determination of Cellulose

Cellulose content was obtained by difference according to Yang et al. [21], considering that the biomass is composed solely of extractives, hemicellulose, lignin, cellulose, and pectin. After determination of extractives, hemicellulose, Klason lignin, and pectin (see Section 2.5), cellulose content was calculated by subtracting the percentages of these components from the total sample. This method is based on the mass-balance approach widely used for lignocellulosic samples.

2.4. Extraction and Determination of Carotenoids

2.4.1. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) of Carotenoid and Extractive Determination (Method B)

The carotenoid extraction was performed with the dried banana peel following an adapted methodology from Silva et al. [22]. A 0.2 g sample was weighed into microcentrifuge tubes, and 3 mL of analytical-grade ethanol was added. The tubes were placed in an ultrasonic bath for 5 min and then centrifuged. The resulting ethanolic extract was collected, and the process was repeated ten times until the solvent in contact with the sample showed no color, indicating complete removal of carotenoids. All extracts from each cycle were combined and vacuum-filtered using quantitative filter paper, while the solid residue pellet was dried in an oven with air circulation at 40 °C until constant weight to determine extractive content (Method B).

The combined extract was subjected to liquid–liquid partitioning following the method of Matos et al. [23]. In a separatory funnel, the extract was mixed with petroleum ether/diethyl ether (1:1 v/v) and washed seven times with distilled water. For recovery, the organic phase was transferred to an Erlenmeyer flask containing anhydrous sodium sulfate and left to rest for 5 min. After this period, the carotenoid extract was concentrated using a rotary evaporator under vacuum (temperature < 38 °C) and re-dissolved in 5 mL of petroleum ether for total carotenoid quantification by spectrophotometry. A 1 mL aliquot was dried under a nitrogen stream and used for carotenoid analysis by HPLC-DAD.

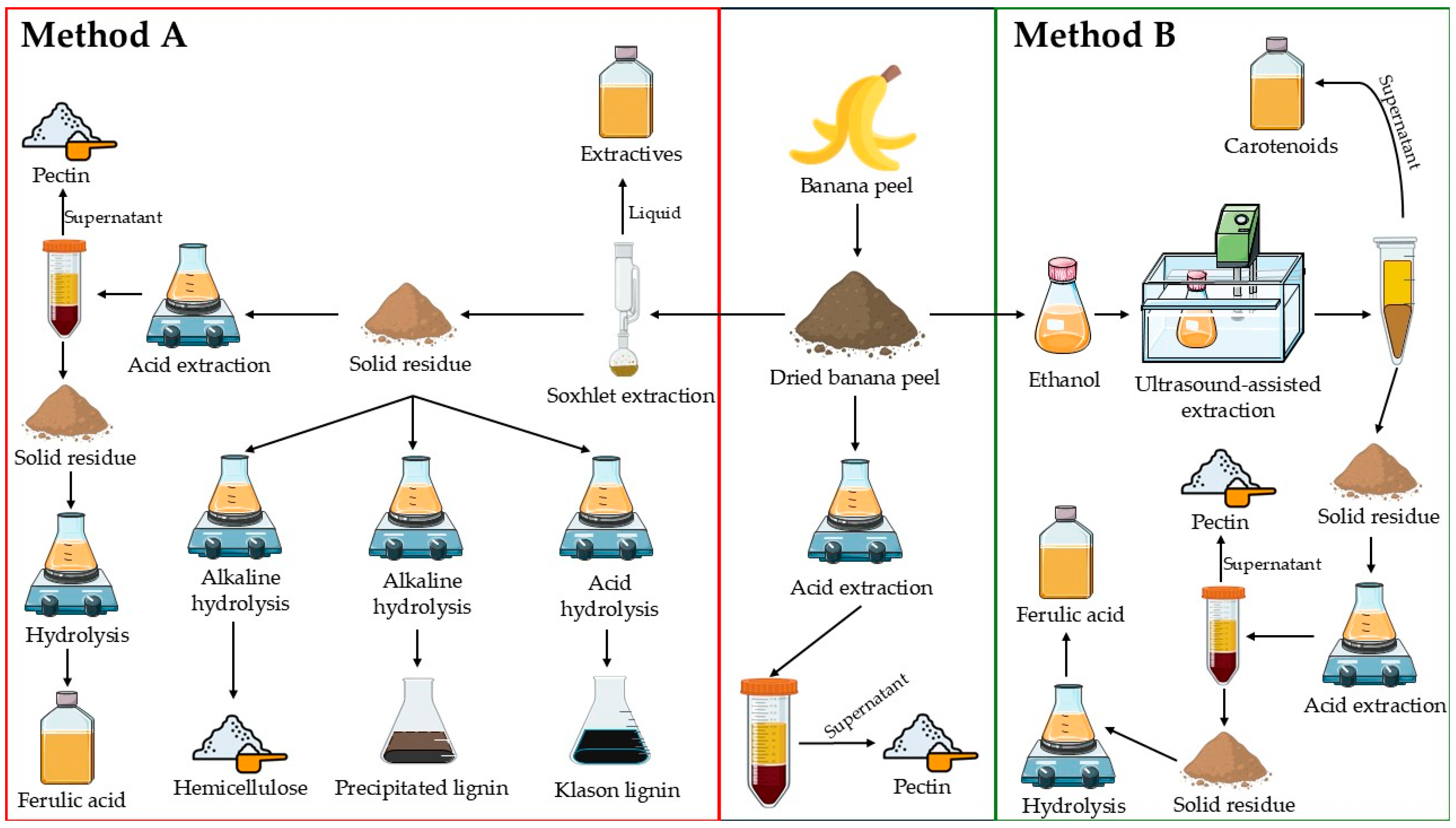

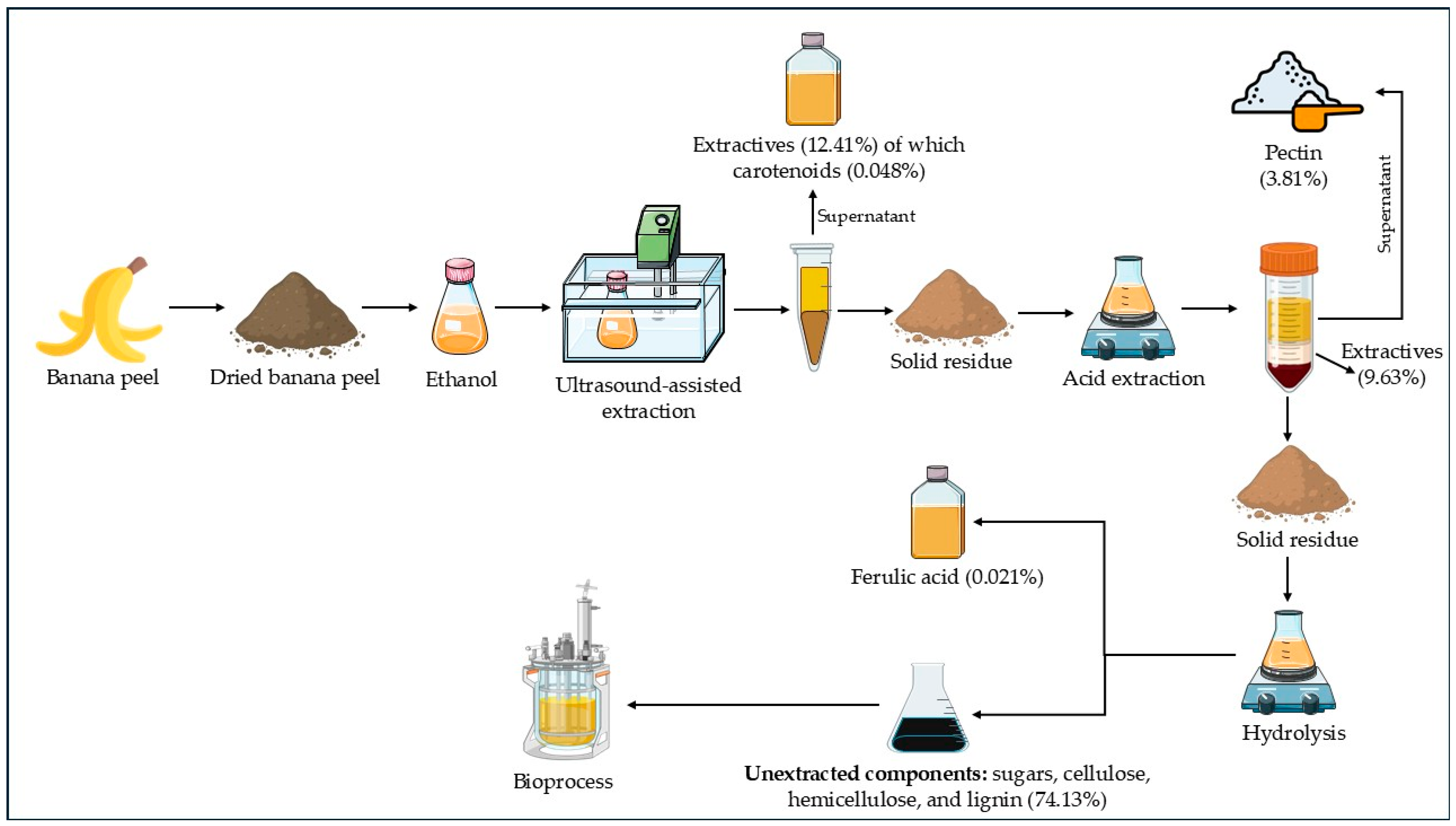

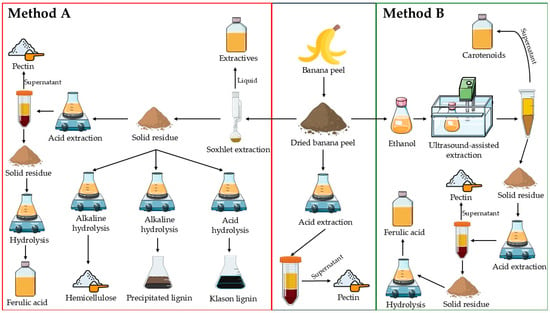

The extractives content (Method B) was determined to compare with the method described in Section 2.2 (Method A). Figure 1 presents a flowchart of both methods.

Figure 1.

Representative flowchart illustrating the methodology and experimental steps of Methods A and B used for extractives determination. Method A refers to extractives determined in Section 2.2 and Method B to those from Section 2.4.1.

The objective of this analysis was to verify whether carotenoid extraction using a GRAS solvent efficiently removes all extractives, thereby enabling the residual material (cell-wall fraction) to be used in subsequent biorefinery steps, such as pectin extraction and cell-wall component hydrolysis. Equation (5) was applied to quantify extractives content by Method B.

2.4.2. Total Carotenoid Determination by Spectrophotometry

The total carotenoid content was determined by spectrophotometry at λ = 450 nm, using the specific absorption coefficient of (all-E)-lutein in petroleum ether (2592) (carotenoid extract obtained after purification and concentration) or ethanol (2620) (ethanolic extract). Carotenoid content was calculated using Equation (6), and the results were expressed as micrograms per gram on a dry weight basis (µg/g DW) [23].

where A is the extract absorbance, is the specific absorption coefficient, k is the dilution factor of the extract, m is the sample mass (g), v is the extract volume (mL); 106 is the multiplier for conversion of the results into µg/g.

2.4.3. Carotenoid Composition by HPLC-DAD

The dried extract was dissolved in methanol (MeOH)/methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) (70:30 v/v) and filtered (0.22 µm syringe filter) before injection (20 µL) into the HPLC system. The HPLC system (Agilent Technologies 1260 Infinity II, Waldbronn, Germany) was equipped with a binary pump, degasser, autosampler, and diode-array detector. Carotenoid separation was performed on a reverse-phase YMC-C30 column (250 × 4.6 mm id, 5 µm particle size, YMC Europe, Schermbeck, Germany) at 29 °C, using methanol (Solvent A) and MTBE (Solvent B) as the mobile phase at a flow rate of 0.9 mL/min. The linear gradient was as follows: from 95:5 (A:B) to 70:30 over 30 min, then to 50:50 over 20 min. Chromatograms were acquired at 450 nm, and all spectra were recorded from 200 to 600 nm. Carotenoid identification was based on the combination of the following data: elution order on the C30 column, UV/Vis spectral characteristics [λₘₐₓ, fine spectral structure (%III/II) and cis-peak intensity (%AB/AII)], and co-chromatography with authentic standards. Prior data from the research group and the literature, obtained by HPLC-DAD coupled with mass spectrometry, were also considered for peak assignment [22]. Carotenoid contents were quantified using an external five-point calibration curve for (all-E)-lutein (2.5–80 µg/mL) and the results were expressed as micrograms per gram on a dry weight basis (µg/g DW).

2.5. Pectin Determination

Pectin was determined according to Oliveira et al. [24] from the raw material and extractive-free material (obtained in Section 2.2 and Section 2.4.1) using a citric acid solution at pH 2.0. Extraction was performed in a water bath at 87 °C under constant agitation for 160 min. The mixture was then centrifuged, and the supernatant was vacuum-filtered. An equal volume of absolute ethanol was added to the filtrate, and the pH was adjusted to 3.5 (the pH at which pectin solubility is minimized) with potassium hydroxide. The mixture was vortexed for 30 min, allowed to precipitate at 4 °C for 2 h, and centrifuged for 15 min. The resulting pellet was collected, washed with ethanol in a 1:1 (v/v) ratio to the pellet volume, centrifuged again for 15 min, and dried in an oven at 40 °C. Pectin content was calculated according to Equation (7).

2.6. Determination of Insoluble Phenolic Compounds

2.6.1. Insoluble Phenolic Compounds Extraction

Insoluble phenolic compounds were obtained according to Arruda et al. [25]. The residue resulting from pectin extraction (Section 2.5) was hydrolyzed with 4 M NaOH containing 10 mM EDTA and 1% ascorbic acid at a solid-to-solvent ratio of 1:20 (w/v) for 4 h at room temperature on a shaker to release insoluble phenolics. After hydrolysis, the mixture pH was adjusted to 2.0 using 6 M HCl, followed by centrifugation. The supernatant was extracted three times with an equal volume of hexane to remove interfering lipids. Insoluble phenolic compounds were then extracted three times with diethyl ether–ethyl acetate (1:1 v/v) at a solvent-to-aqueous phase ratio of 1:1 (v/v). The combined organic phases were filtered through filter paper containing anhydrous sodium sulfate, rotary-evaporated, and the phenolics were reconstituted in 5 mL of HPLC-grade methanol. The extract was filtered through a 0.22 µm syringe filter and used for HPLC-DAD analysis.

2.6.2. Insoluble Phenolic Compounds Analysis by HPLC-DAD

A high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system (Agilent Technologies 1260 Infinity II, Waldbronn, Germany) equipped with a diode-array detector (DAD) was used for data acquisition and processing. Separation was carried out on a Synergy Hydro-RP 80Å C18 column (150 × 4.6 mm id, 5 µm particle size, Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA) maintained at 30 °C. The mobile phases consisted of 1% (v/v) formic acid in water (Solvent A) and methanol (Solvent B). The following gradient was applied at a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min: 95% A for 10 min; linear decrease from 95% to 90% A over 6 min; from 90% to 85% A over 10 min; and from 85% to 75% A over 15 min. Sample injection volume was 20 µL. Chromatographic profiles were simultaneously monitored at 260, 280, 320, and 540 nm. The identification of phenolic compounds was achieved by comparing their retention times and UV/Vis spectral features with those of authentic standards [26]. A calibration curve for ferulic acid was constructed over the range of 5–50 µg/mL, and the results were expressed as micrograms per gram on a dry weight basis (µg/g DW).

2.7. Statistical Analyses

Data were subjected to one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) test for multiple comparisons of means, at a significance level of p ≤ 0.05. For comparisons between two groups, Student’s t-test was applied. All determinations were performed in triplicate, and results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Analysis of Compounds of Interest in Banana Peel

3.1.1. Extractives and Cell Wall Components

The characterization of banana peel revealed a significant content of extractives and lignin, indicating its potential for the extraction of bioactive compounds and biorefinery applications, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Extractives and cell wall components content of banana peel on a dry weight basis.

The extractives content (22.04 g/100 g DW) is considered high and indicates a substantial presence of compounds soluble in organic solvents, such as polyphenols, carotenoids, lipids, and other secondary metabolites of industrial interest [27]. The literature associates high extractive levels with antioxidant, antimicrobial, and bioactive potential, underscoring the relevance of this residue as a feedstock for food- and cosmetic-based biorefineries [28].

Yusof and Yusoff [29] reported an extractive content of 29.85% in banana peel using Soxhlet extraction with an alcohol–toluene mixture, a technique known for its high efficiency due to the combined ability of the solvents to solubilize apolar, semipolar, and resinous fractions. Although these values are higher than those observed in the present study, the difference is not substantial when considering that only ethanol—a polar, food-grade (GRAS) solvent—was employed here, resulting in a more selective extraction primarily targeted at hydrophilic metabolites. On the other hand, Nascimento et al. [30] reported extractive content for banana peel (19.8%) that was very similar to that found in our study. The discrepancy among the extractive values reported in different studies can be explained by the use of distinct solvents, solvent ratios, and extraction methodologies, which result in significant variations in the fraction effectively solubilized.

In other investigations involving alternative food biomasses, such as calamondin peel, extractive contents of approximately 10.26% have been reported, as observed by Husni et al. [31]. These values, which are considerably lower than those obtained for banana peel in the present study, reinforce the notion that banana peel exhibits comparable—or even superior—potential to other agricultural residues for the recovery of bioactive compounds.

The characterization of the cell wall components from banana peel revealed significant contents of lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose. Precipitated lignin accounted for 11.46 g/100 g DW, while Klason lignin totaled 29.63 g/100 g DW. These levels indicate a pronounced presence of lignin, the component responsible for imparting rigidity, impermeability, and protection against microbial degradation to plant cells [32]. In a recent study, Ghosh and Pramanik [33] reported a lignin content of 21.35% in banana peel, a value lower than that observed in the present study. Similarly, Jacqueline and Velvizhi [34] reported lignin contents ranging from 20 to 34.5% for the same biomass, depending on the pretreatment conditions applied. These findings highlight the broad compositional variability of banana peel, influenced both by the characteristics of the raw material and by the analytical methods employed. Lignin, due to its complex aromatic structure, is a strategic resource to produce bioplastics, eco-friendly adhesives, and natural antioxidants, as well as serving as a precursor to high-value compounds such as vanillin and phenolic resins [35].

The structural carbohydrate fraction of the cell wall from banana peel was represented by hemicellulose (19.91 g/100 g DW) and cellulose (23.14 g/100 g DW), totaling 43.05 g/100 g DW. Cellulose contents ranging from 18 to 60% [24,36] and hemicellulose contents from 17 to 40% [37,38] have been reported for banana peel in previous studies, and the values obtained in the present study fall within these ranges. In other agro-industrial residues, Romruen et al. [39] reported substantial hemicellulose (27.78–44.15%) and α-cellulose (33.18–45.81%) contents in matrices such as rice straw, corn cob, pineapple leaf, and pineapple peel. These findings indicate that various tropical biomasses exhibit robust structural compositions compatible with biorefinery valorization, demonstrating that banana peel presents a compositional profile comparable to other agricultural by-products used for the recovery of structural carbohydrates. These polymers perform complementary functions in the plant matrix, providing flexibility (hemicellulose) and mechanical strength (cellulose) to the tissue. Cellulose from residual biomass is widely used in biocomposites, biodegradable films, food applications, and pharmaceuticals [24], whereas hemicellulose is applied in the production of prebiotic oligosaccharides, second-generation bioethanol, and bioactive materials [36].

The pectin extracted from banana peel exhibited a content of 5.28 g/100 g DW. Rivadeneira et al. [40] reported pectin levels in dried banana peel ranging from 0.28% to 14.2%, depending on the extraction conditions applied. In addition to extraction parameters, factors such as banana variety, ripening stage, and the preservation state of the biomass may also influence the pectin content of the peel [41]. This polysaccharide is composed primarily of galacturonic acid units and plays an essential role in the cohesion and flexibility of the plant cell wall. Due to its high gelling capacity and emulsifying properties, pectin is employed as a functional ingredient in foods, as an encapsulating agent for bioactive compounds, and as a matrix for controlled drug release [42].

3.1.2. Carotenoids

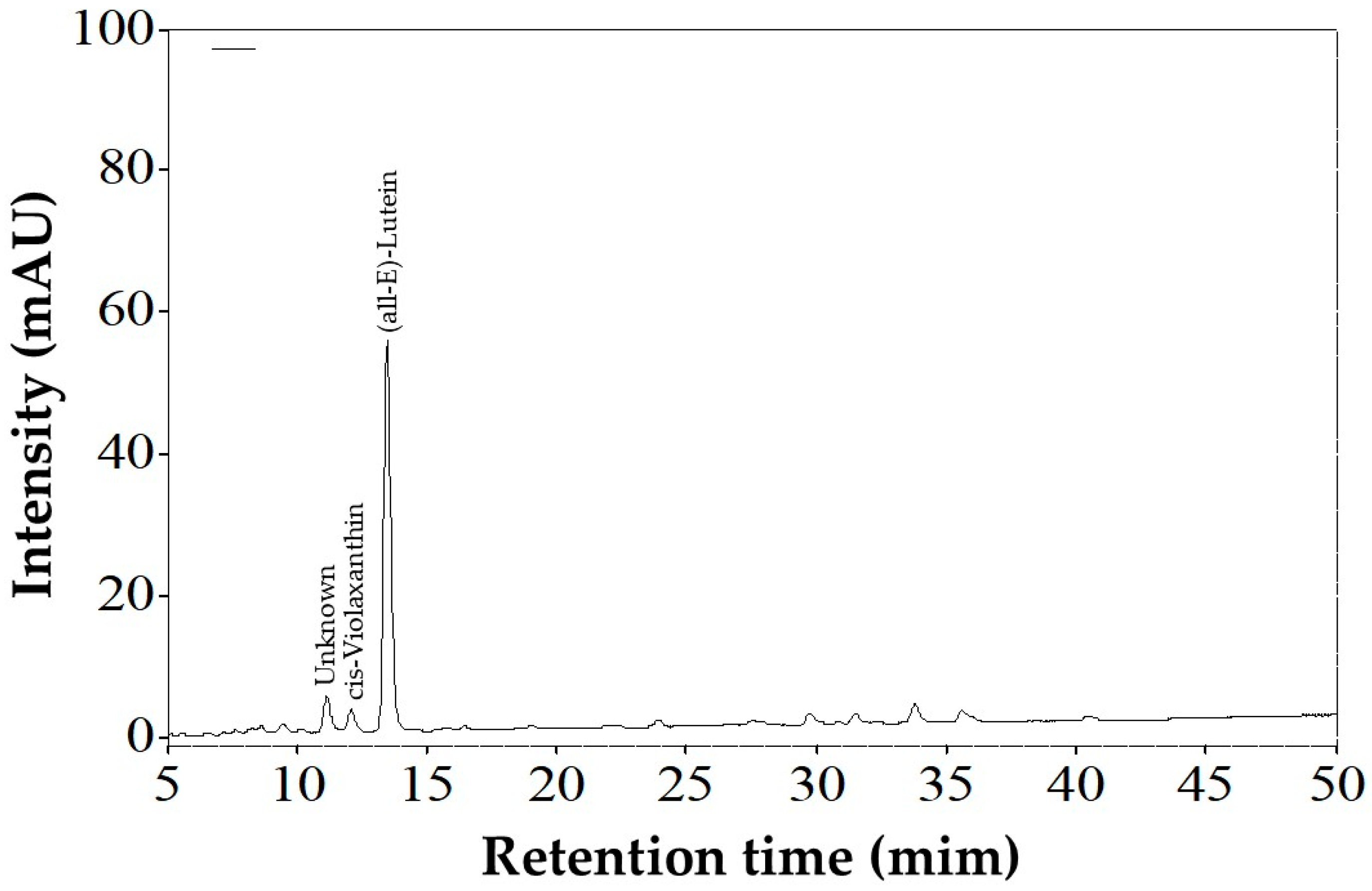

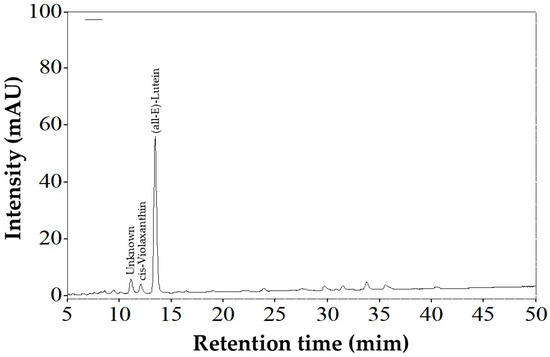

Figure 2 shows the HPLC-DAD chromatogram of the banana peel carotenoid extract obtained using ethanol, a GRAS (Generally Recognized as Safe) solvent.

Figure 2.

HPLC-DAD chromatogram of the ethanolic extract of carotenoids from dried banana peel, recorded at 450 nm.

Table 2 presents the carotenoids detected in the ethanolic extract of banana peel by HPLC-DAD, along with their retention times, maximum absorption wavelengths (λmax), and spectral ratios. Three main peaks were observed in the chromatogram, one of which remained unidentified, while the other two correspond to known carotenoids: cis-violaxanthin and (all-E)-lutein.

Table 2.

Carotenoids identified in the ethanolic extract of banana peel by HPLC-DAD.

Table 3 shows the carotenoid content in both the ethanolic extract and the dried banana peel, determined by liquid chromatography and spectrophotometry. Among the identified compounds, (all-E)-lutein was the predominant carotenoid, with an average content of 338.05 µg/g DW, corresponding to a concentration of 13.68 µg/mL in the ethanolic extract. (all-E)-Lutein is a carotenoid of the xanthophyll family, characterized by a system of conjugated double bonds that imparts its yellow color and antioxidant properties. Its chemical structure includes hydroxyl groups (–OH) at the 3 and 3′ positions, distinguishing it from non-oxygenated carotenes and influencing its solubility and bioactivity [44]. Thus, the ethanolic extract from the banana peel, rich in (all-E)-lutein, can be regarded as a high-value ingredient with potential applications in the food and cosmetic industries, serving as both a coloring and antioxidant agent.

Table 3.

Carotenoid content in the ethanolic extract and dried banana peel.

After converting the values to a fresh-weight basis for comparative purposes, it was observed that the ripe banana peel analyzed in this study presented higher total carotenoid levels (70.76 µg/g) than those reported by Aquino et al. [45] for the ‘Prata’ cultivar (17.23 µg/g). A similar trend was observed for lutein, where the value obtained in our study (40.16 µg/g) was notably higher than the 16.53 µg/g reported by the authors. These differences may be associated with both processing conditions and cultivar-specific characteristics, but they also indicate that the experimental approach employed here favored efficient carotenoid recovery, even without the application of oxidative protection strategies, which reflects the real industrial context of handling this residue. Furthermore, in the study by Aquino et al. [45], acetone was used for carotenoid extraction, whereas in our work, we employed ethanol, a GRAS solvent. This demonstrates that our approach not only extracts carotenoids from banana peel more efficiently but also facilitates the direct application of this extract in the food, pharmaceutical, and cosmetic industries, offering a clean-label appeal and complying with legal requirements regarding the use of green and non-toxic solvents [46].

Compared to other plant by-products, Ramos-Aguilar et al. [47] reported a lutein content of 102.9 µg/g DW in avocado peel, whereas Marcillo-Parra et al. [48] found 12.5 µg/g DW in mango peel. These values—lower than those observed for banana peel (338.05 µg/g DW)—highlight the potential of banana peel, relative to other plant by-products, as an alternative source to obtain carotenoids for functional and industrial applications. Combined with its abundant availability, banana peel emerges as a strategic and valuable resource.

As shown in Table 3, lutein is the predominant carotenoid in banana peel, accounting for approximately 71% of the total carotenoids present. In the food industry, lutein is used as a natural colorant and antioxidant, being incorporated into products such as juice, dairy, fortified products, and nutritional supplements to deliver health benefits and improve product stability, supporting the clean-label trend and the addition of bioactive compounds [49,50]. In the pharmaceutical sector, its inclusion in nutritional supplements aims to protect the macula against oxidative damage, helping to prevent age-related macular degeneration [51]. In cosmetics, lutein is explored for its anti-inflammatory and photoprotective properties, being incorporated into anti-aging formulations and skincare products [52].

According to Tan et al. [44], lutein exhibits low thermal stability at temperatures above 40 °C, especially under prolonged storage conditions with intense light exposure, resulting in significant compound degradation. However, the same study highlights that specific structural modifications or the presence of other natural compounds can contribute to enhancing lutein’s thermal resistance. The fact that lutein was identified as the predominant compound in banana peel even after biomass drying (50 °C for 24 h) suggests that this processing did not result in significant degradation of this carotenoid. This may represent a technological advantage for preserving this bioactive compound in dehydrated food matrices, particularly in plant by-products, thereby expanding its applications in the food industry and functional nutrition.

Other carotenoids were detected in banana peel extract, including an unidentified peak and cis-violaxanthin. When comparing the total carotenoid values obtained by chromatography (476.94 µg/g DW) and spectrophotometry (595.62 µg/g DW), it is observed that spectrophotometric quantification yielded higher values. This difference can be attributed, at least in part, to the presence of minor peaks that could not be quantified or fully resolved in the chromatographic analysis, as shown in Figure 2.

3.1.3. Pectin

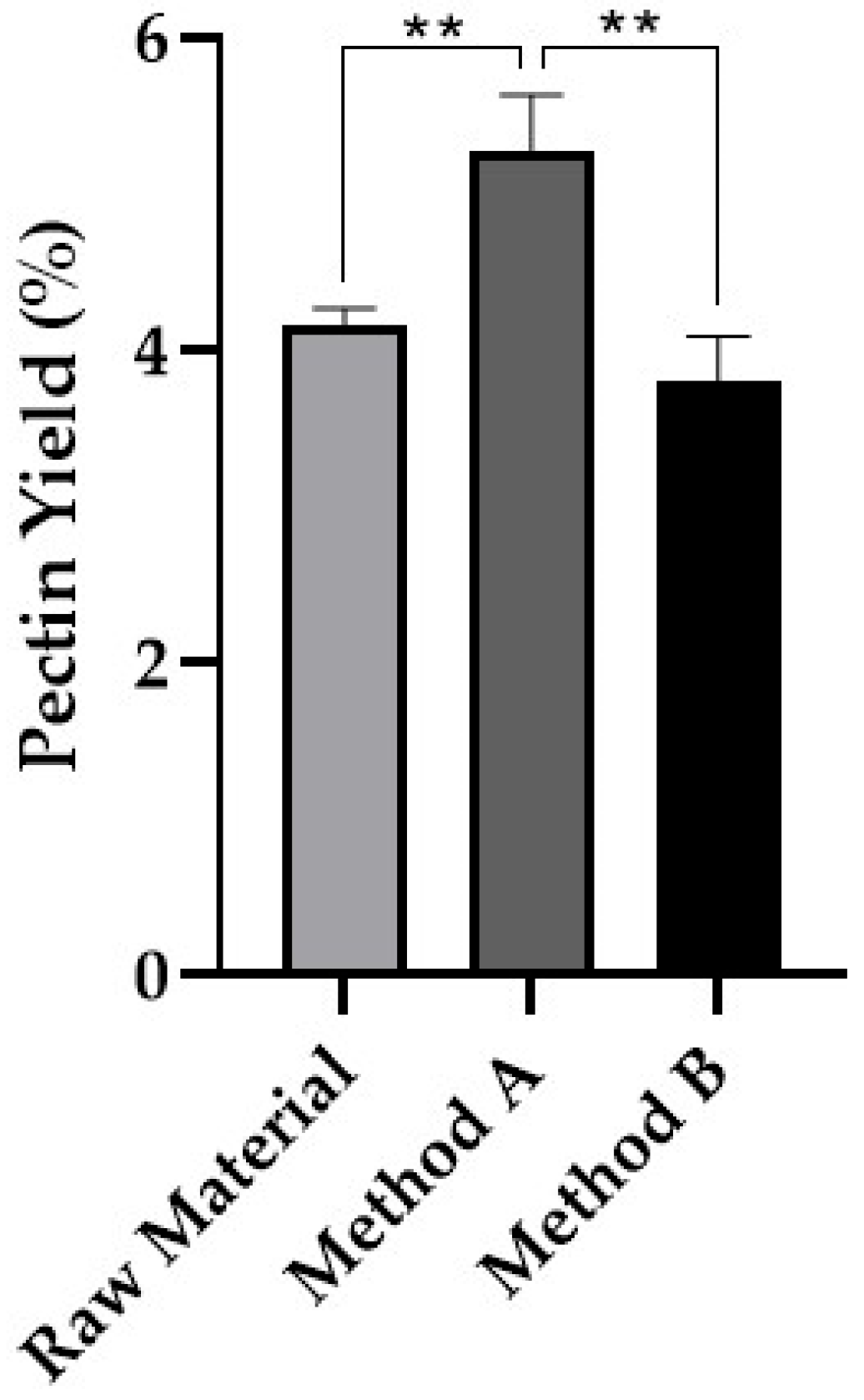

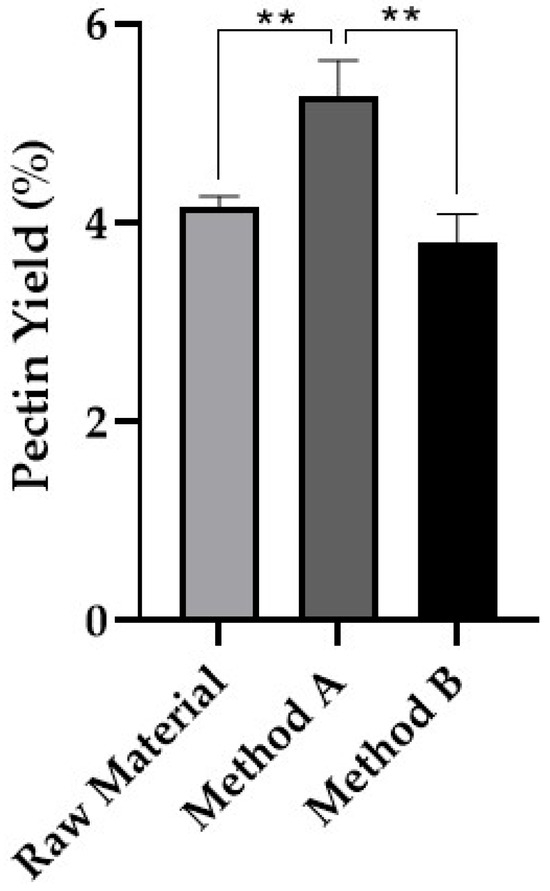

Figure 3 shows the effect of the pretreatment conditions on the pectin extraction of dried banana peel.

Figure 3.

Pectin extraction under different pretreatment conditions. Raw material: Pectin content in dried banana peel without pretreatment. Method A: Pectin content in dried banana peel after removing extractives according to Sluiter et al. [18]. Method B: Pectin content in dried banana peel after extracting carotenoids according to Silva et al. [22]. Values with p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. ** p < 0.01.

As shown in Figure 3, the pretreatment conditions of the banana peel significantly affect the pectin extraction yields. The sample retaining extractives (raw material) exhibited a pectin content of 4.16%, statistically like that of the sample subjected to extractives removal by Method B (3.81%) (p > 0.05). However, Method A, in which extractives were removed beforehand by heat-assisted Soxhlet extraction, yielded the highest pectin recovery (5.28%) (p < 0.05). This increase in yield may be attributed to the thermal treatment facilitating the cleavage of bonds between pectin and other structural components of the cell wall [53]. The difference in pectin yields may be associated with the structure of the banana peel cell wall and the efficacy of the treatment in degrading the polysaccharide matrix. Studies indicate that pectin extraction efficiency is influenced by reaction time and temperature [54]. Furthermore, thermal and hydrolytic degradation can impact pectin solubilization, which may explain the differences observed among treatments. Therefore, the selection of the extraction method and pretreatment conditions should consider not only yield but also purity and key structural and functional parameters of pectin—such as degree of methoxylation, molecular weight, and gelling capacity—which are influenced by processing conditions [55]. Therefore, future investigations evaluating the impact of different pretreatment strategies on pectin properties will be essential for defining extraction routes better suited to the specific requirements of distinct industrial applications.

The structural composition of the extracted pectin also influences its functional properties. Banana peel contains predominantly high-methoxyl pectin, characterized by a degree of esterification above 50%. This pectin type consists of homogalacturonan chains composed of galacturonic acid units linked by α-(1 → 4) bonds, which are partially methyl- and acetyl-esterified [56]. The presence of rhamnogalacturonan I segments, containing arabinan and galactan side-chains, contributes to the structural flexibility of the pectin and influences its emulsifying and gelling properties [53]. In technological applications, the high-methoxyl pectin extracted from banana peel shows strong potential as a thickening and stabilizing agent in the food industry. Moreover, its gelling capacity depends on the presence of sucrose and a decrease in pH, making it suitable for the production of jam and marmalade [57]. Another relevant factor is the high calcium content in banana peel, which can interact with pectin to form “egg-box” cross-link structures, thus influencing its rheological properties and its ability to encapsulate bioactive compounds [58].

Although pectin yield was lower in biomass without extractive removal (raw material), the absence of pretreatment steps can be advantageous from an energy and operational standpoint. Nadar et al. [59] highlight that reducing or eliminating operational steps such as heating and reagent use represents an important advantage in pectin extraction, as it contributes to lowering production costs and environmental impacts. In this context, the pretreatment-free process adopted in the present study eliminates thermal energy consumption and chemical inputs, supporting its application in more sustainable production systems.

Comparatively, similar pectin yields have been reported for kinnow peels (6.13%) using acid extraction [60]. Meanwhile, slightly higher values were obtained for lime orange waste by da Gama et al. [61], with a pectin yield of 8.04%. These data reinforce that banana peel represents a competitive pectin source, especially considering the use of GRAS solvents and sustainable extraction conditions.

3.1.4. Insoluble Phenolic Compounds

No soluble phenolic compounds were detected in the dried banana peel analyzed in this study. The absence of these compounds may be attributed to their degradation during the storage and drying process, likely due to polyphenol oxidase (PPO) activity. Since the enzyme was not inactivated beforehand and the sample was dried in an oven rather than lyophilized, it is plausible that phenolic oxidation occurred. This behavior is consistent with the typical appearance of banana peel in industrial settings, where brown coloration indicates the action of oxidative enzymes on the phenolic constituents [13].

The choice to use dried banana peel, maintaining the condition encountered in industry, aims to reflect the practical reality of valorizing this agro-industrial by-product. Although the oxidation process affects soluble phenolics and alters the biomass color, high-value compounds such as lutein can still be recovered in significant quantities (see Section 3.1.2). Furthermore, pectin and insoluble phenolic compounds, which are structurally more stable, remain available for extraction and utilization.

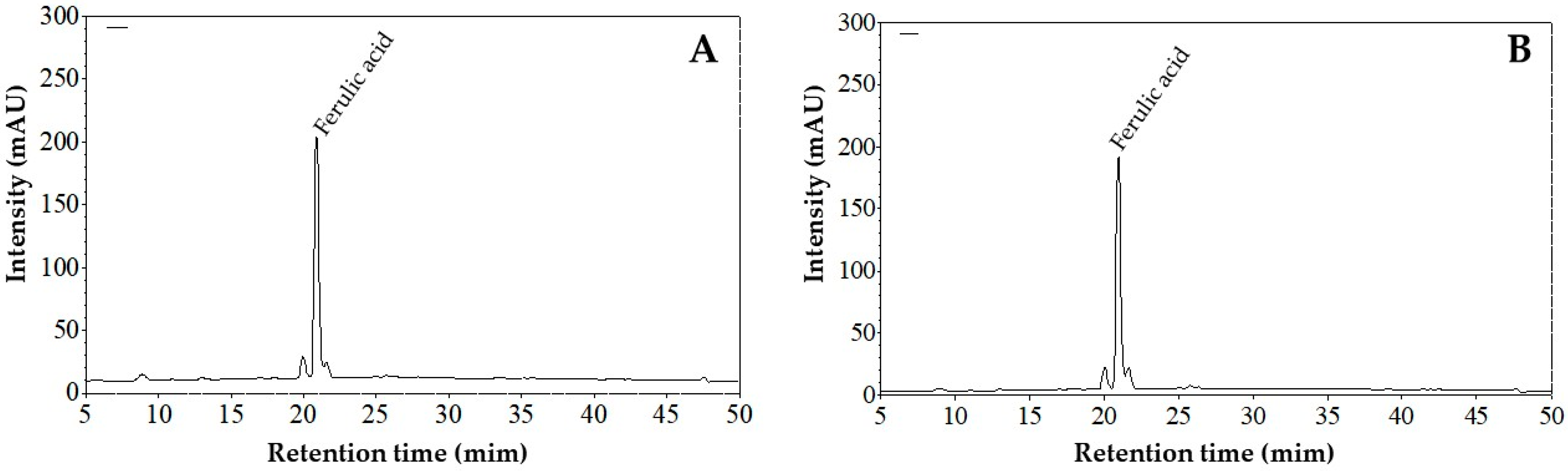

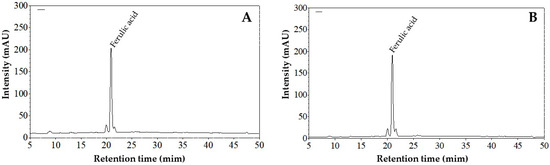

HPLC-DAD analysis (Figure 4) revealed a well-defined peak for ferulic acid in the dried banana peel samples subjected to the different pretreatments before phenolic extraction. This peak exhibited a retention time and UV/Vis spectrum consistent with the ferulic acid analytical standard. The detection of ferulic acid in significant amounts under both pretreatment conditions, Methods A and B, underscores its stability within the banana peel cell wall, even after oxidative (enzymatic browning) and thermal (oven-drying) processes during sample preparation. The clear identification of the ferulic acid confirms banana peel’s potential as a valuable source of insoluble-bound phenolics for functional and technological applications.

Figure 4.

HPLC-DAD chromatogram of insoluble phenolic extracts obtained from the hydrolysis of the cell wall material of extractive-free banana peel, using the extractive removal methods described by Sluiter et al. [18]. (Method A) (A) and Silva et al. [22] (Method B) (B).

Table 4 presents the insoluble ferulic acid content in dried banana peels treated with Methods A and B. Statistical analysis via a paired Student’s t-test showed that the difference between the two methods was not significant (p > 0.05) for both the purified extract and the extractive-free material. This demonstrates that removing extractives and pectin beforehand did not impact the amount of ferulic acid recovered from cell wall components. In contrast, the ferulic acid content calculated for the raw material was significantly higher for Method B (p < 0.05). We attribute this result to the less efficient removal of extractives by Method B, which may leave residual soluble ferulic acid that contributes to the final value measured after hydrolysis. However, overall, the amount of ferulic acid recovered from banana peel is similar between the two methods.

Table 4.

Content of ferulic acid from the insoluble phenolic extracts of dried banana peel obtained after different pretreatments.

The ferulic acid content in dried banana peel found in the present study ranged from 158.74 µg/g DW (Method A) to 178.02 µg/g DW (Method B). According to the Phenol-Explorer database [62], ferulic acid levels in fruit peels such as mango and apple range between 100 and 180 µg/g DW, while maize husks exhibit higher concentrations, around 250 to 300 µg/g DW. Comparatively, dried banana peel presents significant values, falling within the range observed for fruits and surpassing residues such as pineapple peel, which contains approximately 95 µg ferulic acid/g DW.

Ferulic acid (4-hydroxy-3-methoxycinnamic acid) is a phenolic compound of the hydroxycinnamic acid class, widely distributed in the cell walls of fruits, cereals, and plant residues. Structurally, it is characterized by an aromatic ring conjugated to an unsaturated side chain, conferring high antioxidant capacity and chemical stability [63]. In the plant matrix, ferulic acid is predominantly esterified to polysaccharides such as hemicellulose, reinforcing the structural integrity of the cell wall and contributing to protection against oxidative and pathogenic agents [64]. This structural linkage justifies its presence in biomass subjected to drying and oxidative processes, as observed in the dried banana peel of this study. In addition to its potent antioxidant activity, ferulic acid exhibits anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and photoprotective properties, making it a strategic ingredient for applications in functional foods, nutraceutical supplements, and cosmetic formulations [65].

Ferulic acid generates interest across industries due to its multifunctional properties. In the food industry, it is used as a natural antioxidant additive, delaying lipid oxidation and preserving the sensory and nutritional quality of products such as oils, cereals, and meat products [66]. In the pharmaceutical and nutraceutical sectors, ferulic acid is incorporated into formulations aimed at preventing chronic diseases associated with oxidative stress, such as cardiovascular and neurodegenerative disorders [64]. In cosmetic applications, ferulic acid stands out as an active ingredient in photoprotective and anti-aging creams due to its ability to neutralize reactive oxygen species and protect the skin from UV-induced damage [67]. More recently, it has been investigated for incorporation into active biodegradable packaging, imparting antioxidant and antimicrobial properties, and contributing to the extension of shelf life of perishable foods [68]. Valorization of ferulic acid extracted from agro-industrial by-products, such as banana peel, represents a sustainable strategy aligned with circular bioeconomy principles, adding value to by-products and promoting innovation in natural ingredients.

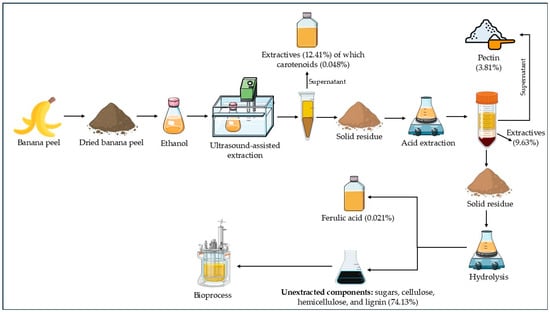

3.2. Integrated Process for Obtaining Various Products from Banana Peel

The development of an integrated process for the sequential extraction of bioactive compounds from dried banana peel represents an innovative strategy aligned with biorefinery principles and the circular bioeconomy [69]. Figure 5 presents a flowchart of the integrated process for obtaining bioactive compounds from dried banana peel. The process was proposed based on the data obtained in the previous steps.

Figure 5.

Proposed integrated process to obtain various functional and technological compounds from banana peel.

In the proposed integrated process, the dried banana peel was initially subjected to carotenoid extraction using ethanol as the solvent. This step removed 12.41% of extractives, of which 0.048% correspond to carotenoids. As shown in Table 1, the dried banana peel contained 22.04% extractives, indicating that 9.63% of extractives (other extractable components) remained in the sample after extracting carotenoids. These residual extractives were removed during pectin extraction and remained in the supernatant after hydrocolloid precipitation. Following carotenoid extraction, pectin was extracted, yielding an average of 3.81%. The extractive- and pectin-free cell wall material was hydrolyzed to obtain ferulic acid with a yield of 0.021%. The solid residue and the liquor obtained after the hydrolysis step and ferulic acid recovery accounted for 74.13% of the initial mass. Although the specific characterization of these fractions was not carried out in this study, it is possible to infer their composition based on the well-established behavior of lignocellulosic biomasses subjected to hydrolysis. The solid fraction tends to concentrate mainly on lignin, residual crystalline cellulose, and a portion of non-solubilized hemicellulose, whereas the hydrolytic liquor is generally composed of soluble sugars resulting from the partial degradation of hemicelluloses (such as xylose and arabinose), in addition to minerals, organic acids, and small oligosaccharides [70].

In this context, the proposed integrated process enabled the recovery of 33.8 mg of (all-E)-lutein, 3.81 g of pectin, and 21 mg of ferulic acid from 100 g of dried banana peel. Among the products obtained, (all-E)-lutein stands out owing to its high market value, especially as a high-purity analytical standard. For example, 1 mg of high-purity (all-E)-lutein costs on average USD 500, indicating that from 100 g of banana peel (oven-dried, PPO-oxidized) it is possible to obtain 33.8 mg of (all-E)-lutein, corresponding to a commercial value of USD 16,900 after appropriate processing. Although high-purity ferulic acid has a lower market value (100 mg for US$ 200), its extraction can yield approximately USD 42 per 100 g of dried banana peel. Commercial food-grade pectin is sold at approximately USD 9–15 per kilogram, which means that the 3.81 g recovered in this study would correspond to about USD 0.03–0.05, in addition to the other fractions obtained. Therefore, banana peel remains a good source of ferulic acid and pectin and can generate additional revenue through their commercialization. It should be noted that the extracts obtained in this study were not purified to analytical-grade standards; therefore, the economic values presented correspond to a theoretical estimation based on market prices of high-purity compounds. The assessment of extract purity and the application of additional purification steps are considered perspectives for future studies.

The ability to sequentially obtain carotenoids, pectin, and ferulic acid using simple steps and GRAS solvents demonstrates the practical feasibility of the proposed system. Each of these compounds has broad industrial interest: carotenoids are used as natural colorants and antioxidants in food and cosmetic products [49]; pectin serves as a thickening, emulsifying, and controlled-release agent in food and pharmaceutical applications [71]; and ferulic acid functions as a natural antioxidant and photoprotective agent in nutraceutical and cosmetic formulations [72].

In addition to generating high-value products, the proposed integrated process is distinguished by its operational simplicity, obviating the need for complex technologies and favoring industrial scalability. Sequential biomass utilization maximizes raw-material efficiency, reduces waste generation, and can minimize energy and solvent consumption, thereby promoting sustainable practices [58]. Another relevant advantage of this process is the valorization of the solid residue and the final liquor obtained after extractions. The resulting hydrolysate, rich in soluble sugars and partial cell wall hydrolysis products, can be employed in bioprocesses such as fermentations to produce bioethanol, biosurfactants, or other biotechnologically relevant compounds [73,74]. This approach is exemplified by Fit et al. [75], who investigated biorefinery design using agro-industrial by-products, such as rice husks, as a sustainable alternative for fossil fuel substitution and the development of biofuels from lignocellulosic materials.

Studies such as those by Goula and Lazarides [76] demonstrate the feasibility of integrated processes applied to the valorization of agro-industrial by-products, such as olive mill wastewater and pomegranate by-products. Like the present work, the authors employed a systematic sequence of extraction steps to obtain high-value products. Both approaches adopt a sequential logic aimed at maximizing bioactive compound recovery, reducing waste generation, and promoting full utilization of plant biomass. Therefore, the integrated process developed in our study not only highlights the potential for valorizing abundant agro-industrial by-products but also exemplifies the integration of technological innovation, sustainability, and the production of multiple value-added products for the food, pharmaceutical, and cosmetic industries.

4. Conclusions

The present study introduces an integrated process for the sequential extraction of bioactive compounds from dried banana peel, employing accessible techniques and preferably GRAS solvents for food-grade applications. The developed strategy enabled the recovery of extracts rich in carotenoids, pectin, and ferulic acid, which are high-value compounds for the food, pharmaceutical, and cosmetic industries. Yields obtained were comparable to or exceeded those reported for other reference biomasses, reinforcing the competitive potential of banana peel as feedstock for sustainable biorefineries. The adopted sequential process ensured efficient multi-component utilization, reducing waste generation and enhancing process sustainability. Furthermore, its operational simplicity and potential for industrial scaling demonstrate the practical feasibility of the proposed model for application in circular bioeconomy-based value chains. Despite the promising results obtained in this study, some limitations should be considered and may be addressed as future perspectives. These include the purification of carotenoid and ferulic acid extracts to obtain products with market-compatible values, as well as investigations into the influence of pretreatments on the degree of methoxylation of pectins. In addition, assessing the influence of polyphenol oxidase activity on the degradation of bioactive compounds represents a relevant aspect to be explored. The continuation of this research may consolidate banana peel as a versatile platform for the development of natural ingredients and sustainable technologies across different industrial sectors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.A.P.; methodology, L.d.S.d.S. and E.N.M.J.; formal analysis, L.d.S.d.S., E.N.M.J. and H.S.A.; investigation, L.d.S.d.S. and E.N.M.J.; resources, G.A.P.; data curation, L.d.S.d.S. and E.N.M.J.; writing—original draft preparation, L.d.S.d.S.; writing—review and editing, G.A.P. and H.S.A.; visualization, G.A.P. and H.S.A.; supervision, G.A.P.; project administration, G.A.P.; funding acquisition, G.A.P. and H.S.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES—Brazil, Finance code 001) and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq—Brazil, grant number 444295/2024-0).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GRAS | Generally Recognized As Safe |

| HPLC-DAD | High Performance Liquid Chromatography with Diode-Array Detector |

| MeOH | Methanol |

| MTBE | Methyl tert-butyl ether |

| UV/Vis | Ultraviolet/Visible |

| NaClO | Sodium hypochlorite |

| EDTA | Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid |

| PPO | Polyphenol oxidase |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| Tukey’s HSD | Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization (of the United Nations) |

| AOAC | Association of Official Analytical Chemists |

| NREL | National Renewable Energy Laboratory |

References

- FAO. Banana Market Review 2024; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, E.A.; Ballen, F.H.; Siddiq, M. Banana Production, Global Trade, Consumption Trends, Postharvest Handling, and Processing. In Handbook of Banana Production, Postharvest Science, Processing Technology, and Nutrition; Siddiq, M., Ahmed, J., Lobo, M.G., Eds.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2020; pp. 1–18. ISBN 9781119528265. [Google Scholar]

- Acevedo, S.A.; Carrillo, Á.J.D.; Flórez-López, E.; Grande-Tovar, C.D. Recovery of Banana Waste-Loss from Production and Processing: A Contribution to a Circular Economy. Molecules 2021, 26, 5282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, N.R.; Aziz, A.H.A.; Faizal, A.N.M.; Che Yunus, M.A. Methods and Potential in Valorization of Banana Peels Waste by Various Extraction Processes: In Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikulwe, E.M.; Kyanjo, J.L.; Kato, E.; Ssali, R.T.; Erima, R.; Mpiira, S.; Ocimati, W.; Tinzaara, W.; Kubiriba, J.; Gotor, E.; et al. Management of Banana Xanthomonas Wilt: Evidence from Impact of Adoption of Cultural Control Practices in Uganda. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaini, H.M.; Roslan, J.; Saallah, S.; Munsu, E.; Sulaiman, N.S.; Pindi, W. Banana Peels as a Bioactive Ingredient and Its Potential Application in the Food Industry. J. Funct. Foods 2022, 92, 105054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berktas, S.; Cam, M. Effects of Acid, Alkaline and Enzymatic Extraction Methods on Functional, Structural and Antioxidant Properties of Dietary Fiber Fractions from Quince (Cydonia oblonga Miller). Food Chem. 2025, 464, 141596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, N.T.K.; Nguyen, V.B.; Van Tran, T.; Nguyen, T.T.T. Microwave-Assisted Extraction of Pectin from Jackfruit Rags: Optimization, Physicochemical Properties and Antibacterial Activities. Food Chem. 2023, 418, 135807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, F.A.; Shriwastav, A.; Gupta, S.K.; Rawat, I.; Bux, F. Exploration of Microalgae Biorefinery by Optimizing Sequential Extraction of Major Metabolites from Scenedesmus obliquus. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2017, 56, 3407–3412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa Rocha, A.C.; de Andrade, C.J.; de Oliveira, D. Perspective on Integrated Biorefinery for Valorization of Biomass from the Edible Insect Tenebrio molitor. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 116, 480–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagh, M.S.; Sivakumar, S.; Nath, P.C.; Chakraborty, A.; Amrit, R.; Mishra, B.; Mishra, A.K.; Mohanta, Y.K. Valorisation of Agro-Industrial Wastes: Circular Bioeconomy and Biorefinery Process—A Sustainable Symphony. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 183, 708–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izanlou, Z.; Akhavan Mahdavi, M.; Gheshlaghi, R.; Karimian, A. Sequential Extraction of Value-Added Bioproducts from Three Chlorella Strains Using a Drying-Based Combined Disruption Technique. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2023, 10, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wohlt, D.; Schwarz, E.; Schieber, A.; Bader-Mittermaier, S. Effects of Extraction Conditions on Banana Peel Polyphenol Oxidase Activity and Insights into Inactivation Kinetics Using Thermal and Cold Plasma Treatment. Foods 2021, 10, 1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalangre, A.; Mirza, A.; Sharma, A.K.; Shaikh, N.; Shabeer, T.P.A. Effect of Drying Temperature on Preservation of Banana Peel and Its Impact on Degradation of Targeted Phytochemical by LC-Orbitrap-MS Analysis. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2025, 15, 30443–30458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.S.; Ballus, C.A.; Menezes, C.R.; Wagner, R.; Paniz, J.N.G.; Tischer, B.; Costa, A.B.; Barin, J.S. Green and Fast Determination of the Alcoholic Content of Wines Using Thermal Infrared Enthalpimetry. Food Chem. 2018, 258, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, Y.; Huang, J.; Zimmerman, A.R.; Chen, H.; Hu, X.; Gao, B. Mechanisms and Adsorption Capacities of Hydrogen Peroxide Modified Ball Milled Biochar for the Removal of Methylene Blue from Aqueous Solutions. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 337, 125432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura-Badilla, O.; Kammar-García, A.; Mosso-Vázquez, J.; Ávila-Sosa Sánchez, R.; Ochoa-Velasco, C.; Hernández-Carranza, P.; Navarro-Cruz, A.R. Potential Use of Banana Peel (Musa cavendish) as Ingredient for Pasta and Bakery Products. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sluiter, A.; Hames, B.; Ruiz, R.; Scarlata, C.; Sluiter, J.; Templeton, D.; Crocker, D. Determination of Structural Carbohydrates and Lignin in Biomass: Laboratory Analytical Procedure (LAP); National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Golden, CO, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC International. AOAC Official Method 940.26 Ash of Fruits and Fruit Products. In Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC INTERNATIONAL; Latimer, G.W., Jr., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, M.; Zhu, L.; Li, J.; Ma, Z. Recovery of Kraft Lignin from Industrial Black Liquor for a Sustainable Production of Value-Added Light Aromatics by the Tandem Catalytic Pyrolysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 446, 141388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Yan, R.; Chen, H.; Zheng, C.; Lee, D.H.; Liang, D.T. In-Depth Investigation of Biomass Pyrolysis Based on Three Major Components: Hemicellulose, Cellulose and Lignin. Energy Fuels 2005, 20, 388–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.V.M.; Santos, A.S.; Pereira, G.A.; Chisté, R.C. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction Using Ethanol Efficiently Extracted Carotenoids from Peels of Peach Palm Fruits (Bactris gasipaes Kunth) without Altering Qualitative Carotenoid Profile. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, K.A.N.; Lima, D.P.; Barbosa, A.P.P.; Mercadante, A.Z.; Chisté, R.C. Peels of Tucumã (Astrocaryum vulgare) and Peach Palm (Bactris gasipaes) Are by-Products Classified as Very High Carotenoid Sources. Food Chem. 2019, 272, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, T.Í.S.; Rosa, M.F.; Cavalcante, F.L.; Pereira, P.H.F.; Moates, G.K.; Wellner, N.; Mazzetto, S.E.; Waldron, K.W.; Azeredo, H.M.C. Optimization of Pectin Extraction from Banana Peels with Citric Acid by Using Response Surface Methodology. Food Chem. 2016, 198, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arruda, H.S.; Pereira, G.A.; de Morais, D.R.; Eberlin, M.N.; Pastore, G.M. Determination of Free, Esterified, Glycosylated and Insoluble-Bound Phenolics Composition in the Edible Part of Araticum Fruit (Annona crassiflora Mart.) and Its by-Products by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS. Food Chem. 2018, 245, 738–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modesto Jr., E.N.; Chaves, R.P.F.; Arruda, H.S.; Borsoi, F.T.; Pastore, G.M.; Pereira, G.A.; Chisté, R.C.; Pena, R.S. Microencapsulation of Anthocyanin-Rich Extract of Grumixama Fruits (Eugenia brasiliensis) Using Non-Conventional Wall Materials and in Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion. J. Food Eng. 2025, 389, 112393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, M.; Ghangrekar, M.M. Performance of Microbial Fuel Cell in Response to Change in Sludge Loading Rate at Different Anodic Feed pH. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 5114–5121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbe, M.; Wallberg, O. Pretreatment for Biorefineries: A Review of Common Methods for Efficient Utilisation of Lignocellulosic Materials. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2019, 12, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusof, N.N.; Yusoff, M. Investigation of Chemical Analysis and Physical Properties of Bio-Polymer Waste Banana Peel Fibre Composite. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 596, 012042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, L.S.; Vieira, F.I.D.M.; Horácio, V.; Marques, F.P.; Rosa, M.F.; Souza, S.A.; de Freitas, R.M.; Uchoa, D.E.A.; Mazzeto, S.E.; Lomonaco, D.; et al. Tailored Organosolv Banana Peels Lignins: Improved Thermal, Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Performances by Controlling Process Parameters. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 181, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husni, E.; Ismed, F.; Afriyandi, D. Standardization Study of Simplicia and Extract of Calamondin (Citrus microcarpa Bunge) Peel, Quantification of Hesperidin and Antibacterial Assay. Pharmacogn. J. 2020, 12, 777–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Q.; Qin, W.; Zhou, Z.; Wu, A.; Deng, W.; Li, Z.; Shan, W.; Chen, J.; Kuang, J.; Lu, W. Banana MaNAC1 Activates Secondary Cell Wall Cellulose Biosynthesis to Enhance Chilling Resistance in Fruit. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2024, 22, 413–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, S.; Pramanik, K. Extraction of Lignin from Sustainable Lignocellulosic Food Waste Resources Using a Green Deep Eutectic Solvent System and Its Property Characterization. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 307, 142094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacqueline, P.J.; Velvizhi, G. Substantial Physicochemical Pretreatment and Rapid Delignification of Lignocellulosic Banana, Pineapple and Papaya Fruit Peels: A Study on Physical-Chemical Characterization. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2024, 37, 101347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Arrigo, P.; Rossato, L.A.M.; Strini, A.; Serra, S. From Waste to Value: Recent Insights into Producing Vanillin from Lignin. Molecules 2024, 29, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harini, K.; Ramya, K.; Sukumar, M. Extraction of Nano Cellulose Fibers from the Banana Peel and Bract for Production of Acetyl and Lauroyl Cellulose. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 201, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odedina, M.J.; Charnnok, B.; Saritpongteeraka, K.; Chaiprapat, S. Effects of Size and Thermophilic Pre-Hydrolysis of Banana Peel during Anaerobic Digestion, and Biomethanation Potential of Key Tropical Fruit Wastes. Waste Manag. 2017, 68, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, M.A.F.; Monteiro, C.R.M.; Pereira, G.N.; Júnior, S.E.B.; Zanella, E.; Ávila, P.F.; Stambuk, B.U.; Goldbeck, R.; de Oliveira, D.; Poletto, P. Deconstruction of Banana Peel for Carbohydrate Fractionation. Bioprocess. Biosyst. Eng. 2021, 44, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romruen, O.; Karbowiak, T.; Tongdeesoontorn, W.; Shiekh, K.A.; Rawdkuen, S. Extraction and Characterization of Cellulose from Agricultural By-Products of Chiang Rai Province, Thailand. Polymers 2022, 14, 1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivadeneira, J.P.; Wu, T.; Ybanez, Q.; Dorado, A.A.; Migo, V.P.; Nayve, F.R.P.; Castillo-Israel, K.A.T. Microwave-Assisted Extraction of Pectin from “Saba” Banana Peel Waste: Optimization, Characterization, and Rheology Study. Int. J. Food Sci. 2020, 2020, 879425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamsucharit, P.; Laohaphatanalert, K.; Gavinlertvatana, P.; Sriroth, K.; Sangseethong, K. Characterization of Pectin Extracted from Banana Peels of Different Varieties. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2018, 27, 623–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.T.; Ho, H.T.; Hoang, D.Q.; Nguyen, Q.A.P.; Tran, T. Van Novel Films of Pectin Extracted from Ambarella Fruit Peel and Jackfruit Seed Slimy Sheath: Effect of Ionic Crosslinking on the Properties of Pectin Film. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 334, 122043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Rosso, V.V.; Mercadante, A.Z. Identification and Quantification of Carotenoids, By HPLC-PDA-MS/MS, from Amazonian Fruits. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 5062–5072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Li, H.; Huang, W.; Ma, W.; Lu, Y.; Yan, R. Enzymatic Acylation Improves the Stability and Bioactivity of Lutein: Protective Effects of Acylated Lutein Derivatives on L-O2 Cells upon H2O2-Induced Oxidative Stress. Food Chem. 2023, 410, 135393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino, C.F.; Salomão, L.C.C.; Pinheiro-Sant’ana, H.M.; Ribeiro, S.M.R.; De Siqueira, D.L.; Cecon, P.R. Carotenoids in the Pulp and Peel of Bananas from 15 Cultivars in Two Ripening Stages. Rev. Ceres 2018, 65, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, S.A.; Rizwan, D.; Bakshi, R.A.; Wani, S.M.; Masoodi, F.A. Extraction of Carotenoids from Agro-Industrial Waste. In Extraction of Natural Products from Agro-Industrial Wastes; Bhawani, S.A., Khan, A., Ahmad, F.B., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 157–178. ISBN 9780128233498. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Aguilar, A.L.; Ornelas-Paz, J.; Tapia-Vargas, L.M.; Gardea-Béjar, A.A.; Yahia, E.M.; Ornelas-Paz, J.J.; Ruiz-Cruz, S.; Rios-Velasco, C.; Escalante-Minakata, P. Effect of Cultivar on the Content of Selected Phytochemicals in Avocado Peels. Food Res. Int. 2021, 140, 110024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcillo-Parra, V.; Anaguano, M.; Molina, M.; Tupuna-Yerovi, D.S.; Ruales, J. Characterization and Quantification of Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Activity in Three Different Varieties of Mango (Mangifera indica L.) Peel from the Ecuadorian Region Using HPLC-UV/VIS and UPLC-PDA. NFS J. 2021, 23, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Li, X.; Dai, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Feng, L.; Nie, M.; Liu, C.; Li, D.; Zhang, M. Study on the Relationship between Lutein Bioaccessibility and in Vitro Lipid Digestion of Nanostructured Lipid Carriers with Different Interface Structures. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 139, 108569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Nolan, J.M.; Flynn, R.; Prado-Cabrero, A. Beyond Food Colouring: Lutein-Food Fortification to Enhance Health. Food Biosci. 2024, 59, 104085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Cheng, J.; Xiong, R.; Chen, H.; Huang, S.; Li, H.; Pang, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, H. Effects and Mechanisms of Lutein on Aging and Age-Related Diseases. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiprasongsuk, A.; Panich, U. Role of Phytochemicals in Skin Photoprotection via Regulation of Nrf2. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 823881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.; Yan, X.; Azarakhsh, N.; Huang, X.; Wang, C. Effects of High-pressure Pretreatment on Acid Extraction of Pectin from Pomelo Peel. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 57, 5239–5249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marenda, F.R.B.; Colodel, C.; Canteri, M.H.G.; de Olivera Müller, C.M.; Amante, E.R.; de Oliveira Petkowicz, C.L.; de Mello Castanho Amboni, R.D. Investigation of Cell Wall Polysaccharides from Flour Made with Waste Peel from Unripe Banana (Musa sapientum) Biomass. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 4363–4372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman-Benn, A.; Contador, C.A.; Li, M.W.; Lam, H.M.; Ah-Hen, K.; Ulloa, P.E.; Ravanal, M.C. Pectin: An Overview of Sources, Extraction and Applications in Food Products, Biomedical, Pharmaceutical and Environmental Issues. Food Chem. Adv. 2023, 2, 100192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepilova, O.; Aleeva, S.; Koksharov, S.; Lepilova, E. Supramolecular Structure of Banana Peel Pectin and Its Transformations during Extraction by Acidic Methods. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 242, 124616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarangi, P.K.; Mishra, S.; Mohanty, P.; Singh, P.K.; Srivastava, R.K.; Pattnaik, R.; Adhya, T.K.; Das, T.; Lenka, B.; Gupta, V.K.; et al. Food and Fruit Waste Valorisation for Pectin Recovery: Recent Process Technologies and Future Prospects. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 235, 123929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lyu, Y.; Tian, J.; Zhao, J.; Ye, N.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, L. Review of Waste Biorefinery Development towards a Circular Economy: From the Perspective of a Life Cycle Assessment. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 139, 110716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadar, C.G.; Arora, A.; Shastri, Y. Sustainability Challenges and Opportunities in Pectin Extraction from Fruit Waste. ACS Eng. Au 2022, 2, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoshal, G.; Negi, P. Isolation of Pectin from Kinnow Peels and Its Characterization. Food Bioprod. Process. 2020, 124, 342–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Gama, B.V.M.; de Farias Silva, C.E.; da Silva, L.M.O.; de Abud, A.S.K. Extraction and Characterization of Pectin from Citric Waste. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2015, 44, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phenol-Explorer Database on Polyphenol Content in Foods. Available online: http://phenol-explorer.eu/ (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Antonopoulou, I.; Sapountzaki, E.; Rova, U.; Christakopoulos, P. Ferulic Acid from Plant Biomass: A Phytochemical with Promising Antiviral Properties. Front. Nutr. 2022, 8, 777576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purushothaman, J.R.; Rizwanullah, M. Ferulic Acid: A Comprehensive Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e68063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hikal, W.M.; Said-Al Ahl, H.A.H.; Bratovcic, A.; Tkachenko, K.G.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Kačániová, M.; Elhourri, M.; Atanassova, M. Banana Peels: A Waste Treasure for Human Being. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2022, 2022, 7616452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobo-Velázquez, D.A. Ferulic Acid: Mechanistic Insights and Multifaceted Applications in Metabolic Syndrome, Food Preservation, and Cosmetics. Molecules 2025, 30, 3716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, J.; Horton, L.; Babadjouni, A.; Kincaid, C.M.; Mesinkovska, N.A. Ferulic Acid Use for Skin Applications: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol. 2025, 18, 38–42. [Google Scholar]

- Moll, E.; Chiralt, A. Active PHBV Films with Ferulic Acid or Rice Straw Extracts for Food Preservation. LWT 2025, 228, 118115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishnoi, S.; Sharma, S.; Agrawal, H. Exploration of the Potential Application of Banana Peel for Its Effective Valorization: A Review. Indian J. Microbiol. 2023, 63, 398–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, S.; Ruiz, H.A.; Ramos-Gonzalez, R.; Martínez, J.; Segura, E.; Aguilar, M.; Aguilera, A.; Michelena, G.; Aguilar, C.; Ilyina, A. Comparison of Physicochemical Pretreatments of Banana Peels for Bioethanol Production. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2017, 26, 993–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, T.; Yang, R.; Li, L.; Lin, H.; Kai, G. Research Progress and Application of Pectin: A Review. J. Food Sci. 2024, 89, 6985–7007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, P.; Singh, A.K.; Srivastava, R.K.; Rathore, S.S.; Sahoo, U.K.; Subudhi, S.; Sarangi, P.K.; Prus, P. Circular Bioeconomy in Action: Transforming Food Wastes into Renewable Food Resources. Foods 2024, 13, 3007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, Q.; Feng, Y.; Xuan, J. Composition of Lignocellulose Hydrolysate in Different Biorefinery Strategies: Nutrients and Inhibitors. Molecules 2024, 29, 2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, G.H.; Longo, V.D.; Romani, L.C.; Saldanha, L.F.; Fornari, A.C.; Bazoti, S.F.; Camargo, A.F.; Alves, S.L.; Treichel, H. Utilization of Banana Peel Waste for the Production of Bioethanol and Other High-Value-Added Compounds. Food Humanit. 2024, 3, 100376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fit, C.G.; Clauser, N.M.; Felissia, F.E.; Area, M.C. Biorefinery Design from Agroindustrial By-Products and Its Scaling-up Analysis. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2025, 31, 102175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goula, A.M.; Lazarides, H.N. Integrated Processes Can Turn Industrial Food Waste into Valuable Food By-Products and/or Ingredients: The Cases of Olive Mill and Pomegranate Wastes. J. Food Eng. 2015, 167, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.