Abstract

Visual inspection is a crucial quality assurance process across many manufacturing industries. While many companies now employ machine learning-based systems, they face a significant challenge, particularly in safety-critical domains. The outcomes of these systems are often complex and difficult to comprehend, making them less reliable and trustworthy. To address this challenge, we build on our previously proposed R4VR-framework and provide practical, step-by-step guidelines that enable the safe and efficient implementation of machine learning in visual inspection tasks, even when starting from scratch. The framework leverages three complementary safety mechanisms—uncertainty detection, explainability, and model diversity—to enhance both accuracy and system safety while minimizing manual effort. Using the example of steel surface inspection, we demonstrate how a self-accelerating process of data collection where model performance improves while manual effort decreases progressively can arise. Based on that, we create a system with various safety mechanisms where less than 0.1% of images are classified wrongly and remain undetected. We provide concrete recommendations and an open-source code base to facilitate reproducibility and adaptation to diverse industrial contexts.

1. Introduction

Machine learning (ML) is becoming increasingly relevant in many areas of our lives. One application of ML is image recognition tasks such as visual inspection [1], medical diagnosis [2,3,4], and structural health monitoring (SHM) [5]. ML-based visual inspection systems often surpass human operators or classical machine vision system and offer superior flexibility [6].

However, a major challenge when integrating ML in visual inspection systems is the black-box nature of ML models, making it difficult for humans to understand their decision-making process [7]. Consequently, it is not possible to determine how a model decides in each case, and malfunctions cannot be easily detected or ruled out. As a consequence, the models often lack user trust [8].

For most vision systems, this is not a problem. However, there are systems where high accuracy and deterministic behavior are mandatory. For example, in inspection of train wheel bearings, false negatives, i.e., an undetected defect, may lead to train derail and, in the worst case, cost many lives. False negatives, therefore, should not occur in such systems. There are several other systems where wrong decisions (false positives, false negatives, or both) may have an unacceptable impact. Due to the unacceptable consequences of wrong decisions, these systems are referred to as critical decision systemsin [9]. Other common critical decision systems the authors identify are self-driving cars, medical diagnosis systems, and intrusion detection systems. Many of these systems are also considered high-risk applications by the EU AI Act. Such high-risk applications have to be assessed before operation and also during their life cycle [10].

A method to make black-box models explainable and interpretable to humans is explainable artificial intelligence (XAI). XAI is nowadays extensively used to increase trust [11,12], improve ML models [13], and gain knowledge [14]. Beyond that, some authors also point out how to leverage XAI to actively enhance safety of ML applications by reducing bias [15,16,17], enhancing overall predictive performance [2,18], or increasing robustness [2,19]. Recently, we proposed a framework for creating safe and trustworthy ML models by integrating XAI throughout the entire life cycle of the model—the so called R4VR-framework [9].

The R4VR-framework suggests to keep a human in the loop throughout the entire life cycle of the model and consists of two phases: the development phase of the model, where the developer performs Reliability, Validation, and Verification, and the application phase, in which the end user performs Verification, Validation, and Reliability. The framework employs XAI and uncertainty quantification (UQ) through the entire cycle and thus helps the end user to make highly reliable decisions based on the model. It, therefore, fosters transparency and addresses key requirements of the EU AI Act. More details on the R4VR-framework itself, as well as the question of how it addresses the EU AI Act, are described in Section 2.

Although the framework covers the life cycle of the ML model itself perfectly, it does not cover mechanisms for reliable data collection. Also, clear recommendations on how to apply the framework in practice are missing. In this work, we, therefore, extend the framework by the step of reliable data collection, translate it into practical recommendations for different use cases, and show—using the example of steel surface inspection—how the framework can be implemented in real-life applications.

We, therefore, aim to provide a practical guideline for researchers and practitioners seeking to mitigate risks associated with ML deployment in critical decision systems. In particular, the paper’s contributions are the following:

- Extension of the R4VR-framework by definition of a reliable data collection process.

- Translation of the R4VR-framework into practical recommendations, allowing practitioners from different domains to adopt the framework.

- Demonstration of the framework using a use case which is relevant for many industries.

- Creation of a code base allowing for adaptation to diverse contexts.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: Section 2 provides an overview of XAI techniques and the R4VR-framework. Afterwards, we point out how the R4VR-framework can be applied in different use cases practically in Section 3. Section 4 points out how we implemented the workflow of the R4VR-framework using the example of metal surface inspection. We discuss our results in Section 5 and provide a conclusion in Section 6.

2. The R4VR-Framework and Its Relation to the EU AI Act

In this section, we give a detailed overview of the R4VR-framework, provide a short introduction to different techniques of XAI, and give a gentle introduction to the EU AI Act.

In course of a literature review on the question of how safety and reliability of ML models can be enhanced by XAI, we proposed the R4VR-framework. During our literature review, we observed that there are basically three mechanisms by which XAI can contribute to safer ML models:

- Reliability: First of all, XAI can help to increase reliability of decisions made by ML models or with the help of ML models. On the one hand, XAI can contribute to the creation of more reliable and safe models, and on the other hand, XAI can provide human decision makers with additional information for assessing a model prediction and making a decision based on the prediction.

- Validation: XAI techniques can help to validate a model’s prediction as they allow one to check if the explanation is stringent, meaning that the features that are highlighted as relevant in the explanation really affect the model prediction if changed.

- Verification: Finally, XAI techniques can serve to verify a model’s functioning in certain ranges. Although it is not possible to verify that a model predicts correctly for all conceivable data points, XAI techniques can help to assess how a model behaves in certain ranges and decrease probability of wrong predictions for these ranges.

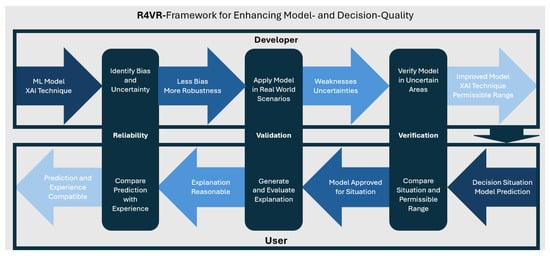

Based on these three mechanisms, we proposed the R4VR-framework—a two-layered framework including the developer as well as the end user of a model. The first layer of the framework addresses the development phase. Here, we suggested that the developer of a model should first of all increase reliability of the model by using XAI. In particular, the developer should harness XAI to reduce bias and increase robustness of the model. In the next step, the model is validated using a human-in-the-loop (HiL) approach. To that end, the model is applied in real-world scenarios with a human expert in the loop. During application, XAI as well as UQ are used in order to allow the human expert to better assess the model. That way, weaknesses of the model can be identified and then be addressed by the developer. Finally, the developer verifies the model, meaning that they examine the model behavior for certain input ranges. Based on the examination and the data the model was trained on, they specify a range in which the model can be applied.

Once the model is verified by the developer, it is handed over to the end user, who applies the model for decision support. Given a decision situation, they first of all verify if the model is approved for the situation. Afterwards, they apply the model along with XAI techniques and then validate the model prediction by looking at the model explanation and uncertainty. Finally, they compare the prediction with their expectation to ensure that it is reliable. A graphical outline of the R4VR-framework is also shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

General structure of the R4VR-framework; developer performs Reliability, Validation, and Verification, and end user performs these steps in reverse order. Reproduced from [9] with permission from the authors, published in AI by MDPI, 2024.

2.1. Explainable Artificial Intelligence as the First Pillar of the R4VR-Framework

The entire R4VR-framework is based on the application of XAI techniques. The main aim of XAI as a field of research is making ML systems explainable. Explainability enables humans to understand the reasons behind a prediction [20].

Within XAI, there are different ways to categorize methods. On the one hand, a distinction is made between intrinsic explainability and post hoc explanations. Intrinsic explainability refers to the property of an ML model of being explainable. Examples of intrinsically explainable models are linear regression, logistic regression, and decision trees. In contrast, post hoc methods uncover the relationship between feature values and predictions [21].

These post hoc methods can be divided in model-specific and model-agnostic methods. Model-specific methods are only applicable to a specific type of model. In contrast, model-agnostic methods can be applied to any model [21]. Furthermore, local and global explanations can be distinguished. While local explanations only explain a certain prediction, global explanations explain the overall model behavior [21].

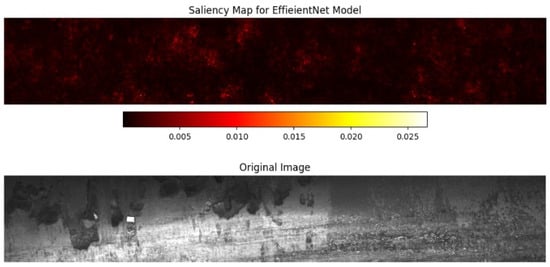

One common XAI technique in image recognition is represented by saliency maps. Saliency maps are applicable to CNNs and provide local explanations. They visualize which regions in an image affect the model’s prediction the most. There are different methods to obtain the regions that are most influential for the decision [22]. For the purpose of our examination, we will use gradient-weighted class activation mapping (Grad-CAM).

Grad-CAM calculates the gradients of the output with respect to the extracted features or the input via back-propagation. Based on this, attribution scores are estimated. These attribution scores can be visualized as a heatmap overlay of the image that is examined. That way, areas in an image that are relevant for the model prediction are visualized [23]. An example for such a saliency map is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Example of saliency map (upper plot) and corresponding image (lower plot). The most important regions used for classification are marked in lighter red; important regions correspond to the areas in the image where defect is located.

2.2. Uncertainty Quantification as the Second Pillar of the R4VR-Framework

Besides XAI, the R4VR-framework also incorporates UQ. UQ deals with measuring how (un-)certain a model is about a certain prediction. More and more authors recognize the importance of UQ when it comes to creating safe and reliable ML models. Mainly in safety-critical applications, UQ can serve as a relevant indicator and help humans to assess whether a model prediction can be trusted or whether validation of the case is necessary [9,24].

There are several approaches to UQ. Bayesian methods approach UQ by modeling weights or parameters of models as distributions. The prediction is sampled from the distribution. In contrast, ensembles employ a combination of different models [25]. Nowadays, approaches like Evidential Deep Learning (EDL) [26] and Deterministic Uncertainty Quantification (DUQ) [27] try to model uncertainty in a computationally efficient way without costly ensembles or sampling.

One commonly used method among Bayesian approaches is Monte Carlo (MC) dropout. MC dropout was proposed in [28]. The authors show that application of dropout before every layer of a neural network is equivalent to the deep Gaussian process and that the Kullback–Leibler (KL) divergence is minimized by dropout.

Using these insights, they show how to derive uncertainty from a model prediction. To do so, they make n predictions with an NN while dropout is enabled. The final prediction is obtained by averaging the results. The uncertainty of the model can be obtained by calculating variance, standard deviation, or entropy within the single predictions.

2.3. EU AI Act for High-Risk Applications

The EU AI Act categorizes AI systems into four levels: unacceptable (forbidden applications), high risk, medium risk, and low risk. High-risk systems are subject to the most stringent requirements because they can significantly affect fundamental rights, safety, or critical infrastructure [10]. We explicitly orient our framework toward the high-risk requirements, as they set a relevant benchmark for trustworthy ML in safety-critical settings.

For such high-risk applications, Articles 9–15 of the EU AI Act define a coherent framework that spans the entire life cycle of an AI system. Article 9 of the EU AI Act requires providers to establish a risk management system that is systematic, documented, and continuously updated. This system must cover foreseeable risks throughout development, deployment, and operation and ensure that residual risks remain at an “acceptable” level [10].

In the development phase, developers must use training, validation, and test sets and systematically examine the underlying data with respect to origin, bias, quantity, and assumptions (Article 10, EU AI Act [10]). These provisions make data governance and traceability central technical and organizational requirements. In parallel, developers are required to produce technical documentation (Article 11, EU AI Act [10]) and to implement logging mechanisms that record relevant operations and system modifications (Article 12, EU AI Act [10]). Together, these articles promote traceability of model behavior over time and support post hoc analysis of failures or near misses.

Articles 13–15 of the EU AI Act set requirements for how the system is exposed to and used by humans. It is mandatory to provide the end users with instructions on how to use the system and enable them to interpret the system’s output (Article 13, EU AI Act [10]). Also, human monitoring should be possible in the entire process (Article 14, EU AI Act [10]). Another requirement for application is sufficient accuracy and robustness (Article 15, EU AI Act [10]). These obligations collectively shape the design and operation of high-risk ML systems and form the regulatory backdrop for our approach.

Taken together, Articles 9–15 of the EU AI Act define not only what a compliant high-risk ML-based system must achieve but also how its life cycle must be organized. In Section 3.1, we map these legal obligations to the phases and roles of the R4VR-framework, showing how its concrete measures can support practitioners in implementing EU AI Act-aligned processes.

2.4. Related Concepts

There is already a wide body of research on HiL ML. Most current approaches mainly aim at improving model accuracy or speeding up learning rather than providing explicit safety guarantees or regulatory alignment [29]. One example of how HiL approaches can reduce manual work was recently proposed in [30]. The authors proposed an automated visual inspection system with an HiL concept designed to minimize manual work. The authors showed that careful dataset preparation and cleaning often have a stronger impact on performance than fine-tuning model architectures, yet their approach remains largely focused on model training and inline use, without explicit safety gates or regulatory mapping. There are various other approaches to HiL ML that we will not cover in detail here. What makes our framework unique is the holistic view striving to leverage XAI, UQ, and HiL for visual inspection with an explicit mapping to regulatory requirements and a focus on ensuring that wrong predictions are systematically detected.

Besides the HiL approach, active learning is also closely related to our work. There are various contributions in the field of active learning that are directly related to HiL visual inspection. For example, [31] combines active learning with explainable AI to support human–machine collaboration in industrial quality inspection. Their framework uses model explanations to guide labeling and sample selection, but it does not include uncertainty quantification or a formalized notion of risk-based operation over the full ML life cycle.

Our work is also connected to research that combines XAI and UQ for safety-critical decision systems. Reviews on uncertainty in XAI summarize both methodological advances and human perception challenges and highlight that uncertainty information must be presented in a way that aligns with human decision strategies to be effective as a safety signal [7,25]. Our contribution builds directly on this line of work: we not only adopt XAI and UQ as safety mechanisms but also embed them into a concrete, iterative end-to-end process for data collection, development, deployment, and monitoring tailored to visual inspection and show how these mechanisms can be used to derive actionable thresholds, warning conditions, and verification ranges.

One commonly used framework that already proposes end-to-end workflows for the entire life cycle of ML models is Machine Learning Operations (MLOps). By today, there are several slightly different conceptualizations of MLOps. In essence, however, MLOps is a paradigm that deals with end-to-end conceptualization, implementation, monitoring, deployment, and scalability of machine learning products. It includes best practices, concepts, but also development culture. MLOps strives to facilitate the creation of ML-based systems and bridge the gap between their development and operation. MLOps primarily addresses engineering and operational challenges such as reproducibility, infrastructure management, pipeline orchestration, and rollback mechanisms. Common principles in MLOps are CI/CD automation; workflow orchestration; reproducibility; the versioning of data, model, and code; collaboration; continuous ML training and evaluation; ML metadata tracking and logging; continuous monitoring; and feedback loop [32].

Recent reviews and empirical studies emphasize that despite its focus on production, MLOps increasingly overlaps with concerns of trustworthy AI and governance, including robustness, monitoring, and traceability. However, they also highlight persisting gaps around systematic human involvement, accountability, and domain-specific safety requirements, especially in high-risk applications. In many organizations, responsibility for regulatory compliance, risk management, and post-market surveillance is still handled outside the MLOps toolchain through manual processes and fragmented documentation [33].

Our work is complementary to these MLOps approaches. While MLOps provides the technical backbone for automating pipelines and operating models at scale, the R4VR-framework focuses on how such pipelines should be structured and governed in safety-critical visual inspection tasks. From an implementation perspective, the two perspectives can be integrated rather than seen as competing. Each phase of our framework can be realized on top of existing MLOps platforms. Recent work explicitly argues for such an integration, showing how MLOps pipelines can be extended with automated checks for transparency and reliability requirements in computer vision systems [34].

In summary, we do not propose an alternative to MLOps, but rather a domain-independent safety and oversight layer that can be instantiated within MLOps toolchains for visual inspection use cases. MLOps ensures that models and data flow through reproducible, automated pipelines. Our framework specifies which HiL, XAI/UQ artifacts, and regulatory controls should be embedded into these pipelines to meet the demands of high-risk industrial and medical applications.

3. R4VR-Framework in Practice

Building upon the theoretical foundations provided in Section 2, we now define a concrete process that converts the R4VR-framework into practical guidelines for adoption of ML in critical decision systems. Unlike the original R4VR-framework, we start even before modeling and take into consideration the process of data collection, which is a key requirement of the EU AI Act. Also, we provide differentiation options for adapting the workflow based on the risk level of the application. While the original R4VR-framework prescribes that the final decision for every instance is made by a human, which is unpractical in certain real-world use cases where thousands of images have to be examined every day, we take a more flexible approach and show how our guidelines can be implemented in different use cases. To outline how the approach can work in real-world scenarios, we also consider two particular use cases, namely, medical diagnosis from images and visual inspection tasks, and show how—based on our guidelines—ML-based systems in these use cases can be implemented in accordance with the EU AI Act.

At this point, we want to highlight that we do not see our work as a new framework. Instead, we want to offer practical measures for implementing the R4VR-framework and show how these can help to meet the requirements of the EU AI Act.

3.1. Practical Implications from the R4VR-Framework

To begin with, we point out particular guidelines that can be extracted from the R4VR-framework. This results in a modular process which operationalizes HiL mechanisms, XAI, and UQ in accordance with the EU AI Act. The process is outlined in Table 1. It ensures technical robustness, transparency, and traceability throughout the ML life cycle and is applicable across different use cases.

Table 1.

Practical recommendations for adoption of the R4VR-framework and preceding data collection to comply with the EU AI Act.

As Table 1 shows, the guidelines for implementation of the R4VR-framework consist of five iterative phases aligned with the EU AI Act. The entire framework is targeted to create highly accurate models and define measures to identify unreliable predictions. Therefore, the need for risk management (Article 9, EU AI Act [10]) is addressed throughout the entire life cycle. Also, all activities during development, as well as application, are logged (Article 12, EU AI Act [10]). By integrating a domain expert into the data generation process, it can be ensured that representative and verified data are used for model training (Article 10, EU AI Act [10]). Application of XAI and UQ throughout the entire framework ensures robust and reliable models (Article 15, EU AI Act [10]) and improves human oversight (Article 13, EU AI Act [10]), as well as human monitoring (Article 14, EU AI Act [10]), during application of the model. The obligation for technical documentation (Article 11, EU AI Act [10]) is satisfied by the Verification phase, where the developer defines and documents operating conditions, as well as thresholds for the flagging of unreliable predictions.

3.2. R4VR-Framework in Medical Use Cases

Having introduced practical guidelines on how to implement the R4VR-framework, we now take a look at how the framework can be adopted in medical use cases such as cancer diagnosis based on images. In such settings, ML systems are typically classified as high risk and must comply not only with the EU AI Act but also with sector-specific regulation and institutional governance procedures (e.g., ethics review, data protection rules, and clinical safety management) [35]. Beyond technical compliance, medical applications require adherence to ethical and data protection principles, for example, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in the EU [36].

Below, we outline how the phases Data Collection, Reliability, Validation, Verification, and Deployment and Monitoring can be implemented in a way that is compatible with the R4VR-framework and these regulatory constraints.

- Data Collection

In contrast to purely technical domains, data collection in medical use cases is tightly regulated. Although physicians routinely diagnose patients based on imaging modalities such as MRI, CT, and endoscopy, these clinical activities cannot be used for AI development without appropriate safeguards. Typically, an institutional governance process that includes at least the following is required [37]:

- Approval by an ethics committee and/or institutional review board;

- A clearly defined legal basis for data processing (e.g., consent, public interest, or care provision);

- Pseudonymization or anonymization of imaging data and associated labels;

- Secure storage and access control for the resulting dataset.

Once governance is in place, image data can be extracted from clinical systems. In many diagnostic pathways, physicians already record structured or semi-structured diagnostic labels in radiology reports or tumor boards. If they follow established clinical standards, they can often be deemed reliable and be used as labels for training ML models. During this phase, all relevant metadata (e.g., imaging modality, acquisition protocol, device, patient demographics, data source, and preprocessing steps) should be logged to support later verification and reproducibility [38].

- Reliability

The next step is to build reliable baseline models. Medical datasets are often imbalanced [39]. This must be explicitly addressed during model development, for example, by

- Constructing balanced training, validation, and test splits;

- Applying data augmentation tailored to the modality;

- Including data from multiple institutions or devices where feasible to improve robustness.

In line with the R4VR-framework, at least two sufficiently different models should be trained (e.g., different architectures, training seeds, data splits, and input preprocessing pipelines). For each model, XAI (e.g., Grad-CAM for local saliency maps) and UQ (e.g., MC dropout) are integrated from the beginning. Saliency maps allow the developer to check whether the model focuses on clinically meaningful regions, while UQ provides a quantitative estimate of prediction reliability [7]. Based on the empirical distribution of uncertainties in the development data, model-specific uncertainty thresholds are defined to indicate when predictions should be considered unreliable.

- Validation

In the next step, the developer and a domain expert improve the system collaboratively. The model is applied to new images from clinical practice that were not used during training. All cases for which either of the following applies are automatically flagged:

- The two models disagree;

- The uncertainty of at least one model exceeds its predefined threshold.

In addition, experts can further flag images based on non-stringent explanations, for example, if the saliency maps highlight irrelevant structures.

For each flagged case, the expert reviews the image, the model predictions, explanations, and uncertainty scores and confirms or corrects the label. Systematic patterns observed during this process (e.g., increased uncertainty for certain scanners, protocols, or anatomical variants) are documented. The verified and corrected cases are then added to the training set, and the models are retrained. This iterative HiL loop continues until the performance is deemed acceptable for the intended use.

- Verification

Finally, the models have to be verified by the developer. This step combines a formal assessment of the training data with targeted stress testing. For medical image diagnosis, this typically includes [37,38]

- Imaging modality and acquisition protocol (e.g., contrast-enhanced breast MRI and low-dose chest CT);

- Image characteristics (e.g., resolution, voxel spacing, and input preprocessing pipeline);

- Clinical context and population (e.g., screening vs. symptomatic patients, age ranges, and sex-specific indications);

- Institutional and device constraints (e.g., scanner models or vendors seen in training).

Within these constraints, the model is evaluated using internal and, ideally, external test sets to confirm performance and uncertainty behavior. For each model, an “operational envelope” that specifies when the system may be used as decision support, when manual review is mandatory, and when the model must not be applied at all is documented. These specifications, together with assumptions and limitations, are recorded as part of the technical documentation required by the EU AI Act [10].

- Model Deployment

Once the models are developed, they can be handed over to the end user, e.g., a physician. Typically, the system serves as a clinical decision support tool integrated into existing systems [38]. For handover, the model should be integrated into a user interface which

- Allows the user to upload images and make a prediction;

- Incorporates a visual representation of the model’s uncertainty, allowing the user to immediately see if one of the models is too uncertain;

- Visualizes local explanations (e.g., Grad-CAM overlays) directly on the medical images;

- Allows the end user to mark images where uncertainty is high, an explanation is not stringent, or at least one of the models predicts a result that the user does not agree with.

During application, clinicians follow the R4VR sequence Verification, Validation, and Reliability:

- Verification: The clinician checks whether the model is approved for the specific case. If not, the model output must not be used.

- Validation: For approved cases, the clinician examines whether all models agree, whether uncertainties remain below the predefined thresholds, and whether explanations are clinically plausible. Cases that fail these checks require increased scrutiny or alternative diagnostic pathways.

- Reliability: Finally, the clinician compares the model output to his or her own clinical judgment. The ML system is used as decision support but does not replace the physician’s responsibility for the final diagnosis.

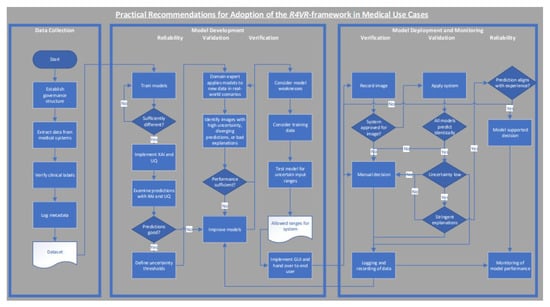

All interactions, warnings, and user corrections are logged to support traceability, post-market monitoring and future model updates in alignment with Articles 12 and 14 of the EU AI Act [10]. A flowchart showing the exact workflow of model development and model deployment is also visualized in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Flowchart showing how the R4VR-framework can be adopted in medical use cases.

3.3. R4VR-Framework in Industrial Image Recognition

For industrial settings such as visual inspection, adoption of the R4VR-framework can also be relevant. Depending on the application, ML-based inspection may be classified as non-high risk or high risk under the EU AI Act [10]. For example, inspection of safety components for critical infrastructure or transport systems clearly belongs to the latter category, while inspection of purely cosmetic defects often does not. In both cases, however, reliability, transparency, and human oversight remain crucial [40].

Compared with medical use cases, data availability, real-time constraints, and the role of domain experts differ. In particular, labeled data may be scarce, the environment may change over time (e.g., illumination and surface conditions), and continuous production throughput must be maintained [41]. Below, we outline how our guidelines can be adapted to these circumstances.

- Data Collection

A common issue in many industrial settings is a lack of data for model training [42]. Therefore, data collection and labeling should be explicitly planned as a prior phase that seamlessly integrates into the production process.

A practical strategy is to deploy an HiL labeling interface at the inspection system before a fully automated ML model is available. Each image recorded by the inspection camera is stored and by default assigned to the majority class (e.g., “OK” for visual inspection). Whenever the operator identifies a defect, he or she assigns the corresponding defect class in the interface. These operator-provided labels are logged together with metadata such as time, product ID, camera configuration, and process parameters. Over time, this yields an initial, traceable dataset.

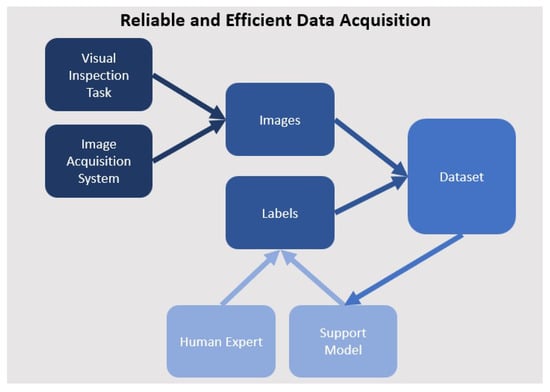

Once a small but representative dataset is available (e.g., 5–10 images per defect type), a first support model can be trained. The model is then integrated into the same interface. It proposes labels for new images and flags cases with predicted minority classes or low confidence. The operator can either confirm or correct these labels. The model can be retrained regularly in order to increase its accuracy. That way, a self-accelerating process in which the model gets better progressively emerges, which leads to reduced relabeling effort for the human domain expert [42]. A graphical outline of the process is also shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Graphical outline of data generation process: images are recorded in the process; human expert creates initial labels for training a support model; support model assists human expert in data collection and is retrained regularly.

The process is characterized by two key variables: number of images used for training the initial model and retraining frequency. These parameters determine the quality development of the model and have a significant impact on the number of images to be labeled manually but also the computational costs.

For compliance with the EU AI Act, the data collection process and all configuration changes should be documented. Also, the data acquisition period should be sufficiently long to capture relevant variations in the production environment [10].

- Reliability

Once a sufficiently large dataset is available, baseline models are trained in the Reliability phase. Similar to the medical setting, at least two diverse models (e.g., different architectures or input representations) should be developed. Data augmentation plays a central role to ensure robustness against common variations such as changes in illumination, small shifts in camera position, and surface appearance changes [43].

XAI and UQ are integrated directly into model development. Local explanations help verify that models attend to defect-related regions rather than to irrelevant background patterns or systematic artifacts (e.g., conveyor belt structures) [7]. UQ quantifies prediction uncertainty and supports the definition of thresholds for safe automation [44]. The developer analyses model errors and explanations and adjusts the data, augmentation, or architecture to reduce bias and overfitting.

- Validation

The Validation phase aims to iteratively improve the models based on expert feedback. Depending on the risk level and the availability of domain experts, two variants are possible:

- If domain experts are available and the use cases justifies the costs, Validation should be carried out as in the medical setting: experts review all images for which the models disagree, uncertainties exceed predefined thresholds, or explanations are implausible. They confirm or correct labels and provide qualitative feedback on failure patterns.

- If expert time is limited and the use case does not justify consultation of an expert, the developer leads the Validation phase and focuses primarily on explanations and systematic patterns (e.g., increased uncertainty for specific products or illumination conditions), while accepting that some individual misclassifications may remain undetected.

In both cases, flags are generated automatically whenever either of the following applies:

- Model uncertainty exceeds a threshold;

- Two models assign different defect classes to the same image.

For these cases, images, predictions, explanations, and associated process parameters are reviewed in more detail. New or corrected labels are added to the training data, and the models are retrained periodically. This aligns with previous work that demonstrates the benefit of uncertainty estimation and explainability for monitoring ML-based systems [45,46].

- Verification

In the Verification phase, the developer specifies the operational range in which the model can be used safely. This includes at least

- Type of inspected objects and defect classes;

- Expected range of image characteristics (e.g., resolution, field of view, camera angle, and brightness range);

- Production conditions (e.g., speed of the line, presence of cooling liquids, and scale);

- Limitations resulting from the training data (e.g., only certain product variants or surface finishes).

Targeted test sets are constructed to test the model’s behavior within and close to the boundaries of this operational range. For each configuration, accuracy and uncertainty patterns are evaluated. Based on these experiments and the training data analysis, the developer defines conditions under which the system may operate autonomously, conditions that require operator confirmation, and conditions where the model may not be used. This information is reflected in technical documentation and operating procedures.

- Deployment and Monitoring

After Verification, the model is handed over to the end user along with a user interface. In contrast to medical settings, the goal in many industrial use cases is partial automation of the inspection process [42]. To align this with the R4VR-framework, we recommend a user interface that

- Automatically processes each new image recorded by the inspection system;

- Visualizes uncertainty for each prediction and raises warnings when thresholds are exceeded;

- Shows explanations (e.g., saliency overlays) so that operators can see which regions drive the decision;

- Allows the operator to correct predicted labels and, if needed, annotate defect locations.

During operation, the R4VR steps are implemented as follows:

- Verification: Whenever the settings of the inspection system are changed or a new project is manufactured, the end user has to verify whether the model is approved for the situation. If not, the model output must be treated as unreliable, and a fallback procedure such as manual inspection has to be used.

- Validation: For images that trigger warnings (high uncertainty, model disagreement, or out-of-range process parameters), the operator manually determines the correct class and, optionally, updates the label in the interface. These images are stored as candidates for future retraining.

- Reliability: In order to detect performance degradation (e.g., due to data shift), the end user should regularly check a certain number of images manually. If systematic deviations are observed, the system re-enters the development cycle for renewed data collection and model improvement.

All predictions, warnings, operator corrections, and system changes are logged for traceability and potential audits as required by the EU AI Act. This results in an inspection process where automation and human oversight are balanced according to the potential risk and where XAI and UQ provide the technical basis for selective human intervention.

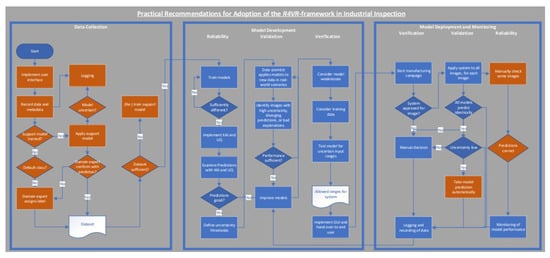

Using the described process, an automated inspection process where manual input is only required occasionally for checking the system’s reliability or examining selected images where uncertainty is high or models disagree emerges. The process is also outlined visually in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Flowchart showing how the R4VR-framework can be adopted in industrial inspection tasks. Key differences compared with recommendations on adoption of the R4VR-framework in medical use cases are highlighted in orange; key differences are as follows: data collection by HiL approach; model predictions can be used automatically after Validation; Reliability during model application is realized by occasional checks instead of model-supported decision.

4. Implementation of R4VR-Framework for Visual Steel Surface Inspection

Having introduced practical implementation guidelines for the R4VR-framework, we now demonstrate how the framework can actually be used to create very safe ML systems. To do so, we use the “Steel Defect Detection 2019 Challenge dataset” [47], which is widely used in research for defect classification and presents steel surfaces from production scenarios. The dataset was originally released on Kaggle (https://www.kaggle.com/c/severstal-steel-defect-detection, accessed on 10 October 2025).

The dataset consists of 18,074 images of steel surfaces. These images either show no defects or one of four possible defects (“pitted”, “crazing”, “scratches”, and “patches”). In course of the competition, 12568 annotated images were released. The remainder of the images came in a test set without labels. Originally, the dataset was intended as a dataset for segmentation. However, different researchers also applied it for classification tasks only, e.g., [48].

For this study, we assumed that the inspection of steel surfaces does not justify inclusion of an expert during Validation. From our point of view, the potential risks are not high enough. Also, the defects in the images are visible and distinguishable for most people. However, in real-world use cases, it has to be determined whether an expert has to be consulted for the Validation phase in every single case. Here, the potential risks but also the complexity of the data should be regarded. If the data are too specialized for the developer to conduct proper Validation, a domain expert is required.

As we currently do not have a real-world use case where we can actually deploy the readily developed model, we only exemplary demonstrated how the model could be deployed in real-world scenarios. All experiments described below are available in our GitHub (https://github.com/jwiggerthale/Human-in-the-Loop-Machine-Learning, accessed on 10 December 2025) repository. In our GitHub repository, there is also a test on a the “NEU-DET steel surface defect detection dataset” [49]. The dataset is not as big as the main dataset and allows for testing with fewer resources.

In course of this study, we trained two models, a ResNet18 model [50] and an EfficientNet-B0 model [51]. We also tested other architectures, such as vision transformers, but found that they performed worse. The code for training these other architectures is available in our GitHub repository. For training the models, we used the PyTorch 2.7.0 library [52] and pretrained weights for ImageNet1k [53]. All experiments were conducted 10 times with different seeds in order to ensure robustness. All reported metrics are average values. In our GitHub repository, we also report the results of every single run.

In case of the ResNet18 model, we added dropout layers in order to perform MC dropout. To obtain optimal model performance, we performed grid search on the hyperparameters. The general hyperparameters and settings used for training and testing are documented in Table 2. More special parameters, such as augmentations, applied in each single experiment can be found in our GitHub repository.

Table 2.

Parameters used for training models and UQ.

4.1. Data Collection

Although we used a labeled dataset, we imitated the process of data collection as outlined in Section 3.3. In particular, we trained EfficientNet-B0 as well as a ResNet18 model as support models using an initial dataset and retrained the models regularly. In real-world use cases, it would be sufficient to train one model as the support model. The implementation of two models would only add an additional layer of complexity because contradicting predictions that require additional operator actions could occur.

As explained in Section 3.3, the initial dataset size and the retraining frequency are important parameters that determine the efficiency of the process. To provide insights in the efficiency of different parameter settings, we conducted the training of a support model with different settings for “number of initial images” and “retraining frequency”. To do so, we varied the parameters “number of initial images” and “retraining frequency” and examined how many images have to be labeled manually and how many computing resources are required. We conducted the test using a GPU of type NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090. For each setting, we trained the models until 195 images of each class were available, as 195 is the number of unique images available in our final training dataset for images of class “crazing”, which is the least common class in the dataset.

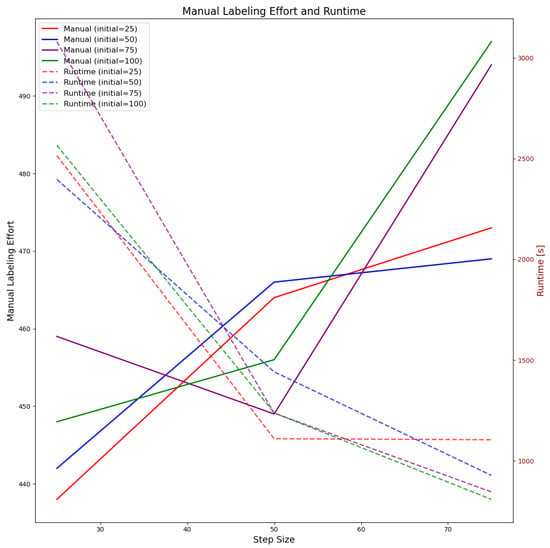

We tested an initial number of images between 25 and 100 (5–20 images per class) and retraining frequencies between 25 and 75 (5–15 images per class). For this study, we always used balanced datasets, meaning that all image classes are represented equally. Regarding the initial dataset—as there is no majority class in the dataset—we assume that four/five of the images have to be labeled; i.e., images of one class obtain the correct label automatically. The results of our test on parameter setting for the ResNet18 model are visualized in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Impact of number of images used for initial training and retraining frequency on number of images to be labeled manually and computing time when using ResNet18 model as support model, More images have to be labeled manually when number of images used for initial model training or step size increase; computing time reduces when reducing retraining frequency but is almost unaffected by number of initial images.

The continuous lines in Figure 6 show the total number of images to be labeled manually depending on the initial size of the training set (decoded by color) and the retraining frequency (x-axis). The number of images to be labeled manually increases as the number of images for the initial training dataset increases. Also, reduced retraining frequency leads to higher manual labeling effort in most cases. In contrast, reduced retraining frequency lowers computing effort as is visualized by the dashed lines. When using 25 images for initial model training and retraining every time 25 new images are available, only ∼440 images have to be labeled manually. However, this leads to a computing time of ∼2500 s (∼40 min). When reducing the retraining frequency to 75 images, ∼480 images have to be labeled manually, but the computing time decreases to ∼1100 s (20 min). When using 100 images in the initial dataset, ∼470 images have to be labeled manually when using a retraining frequency of 25 images. When decreasing the retraining frequency to 75 images, ∼520 images have to be labeled manually. Computing times are almost identical to the ones required when using 25 images for training the initial model. We observed similar behavior when using the EfficientNet-B0 model as the support model. The appropriate visualization is available in our GitHub repository.

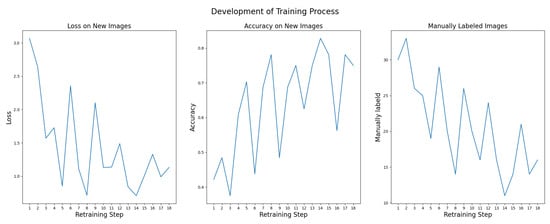

Hence, it can be said that reduced number of initial training samples tends to be better with regard to manual labeling effort but does not significantly increase computing costs. From Figure 6, it can be seen that using 75 images in the initial dataset (15 images per class) and retraining every time 50 new images (10 images per class) are available is a good trade-off between computing costs and manual labeling effort. That way, computation takes ∼1200 s (∼20 min), and ∼460 images have to be labeled manually. The performance development for a ResNet18 support model trained in this way is visualized in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Performance development of ResNet18 support model. Loss decreases from ∼3.0 to ∼1.0; accuracy increases from ∼0.4 to ∼0.8.

It can be seen from Figure 7 that loss decreases from ∼3.0 in the first retraining stage to ∼1.0 in the last retraining stages and accuracy increases from ∼0.4 to ∼0.8. The number of images to be labeled manually decreases from ∼30 to 10–15 in the last retraining stages.

4.2. Reliability—Creating Strong Baselines

Having collected a sufficient number of data by using the HiL approach, we implemented the actual R4VR-framework. To begin with, we conducted the step of Reliability and trained baseline models. The dataset was highly unbalanced. Therefore, we proceeded in two steps. In a first step, we applied the oversampling of minority classes to train the baseline models. Afterwards, we froze the models’ feature extractors and fine-tuned them on a dataset that reflects the real class distribution. For the former step, we created a training dataset which comprises a total of 5000 samples (1000 samples per class). In the latter step, we removed all duplicates from the dataset. For validation we used 1000 samples, and for the final tests conducted in course of this study, we used the remainder of labeled images from the dataset. In order to create sufficiently different models, we trained each model only on half of the images from the training dataset in the pretraining stage. For each of the 10 training cycles, images were randomly assigned to the different models. That way, we could rule out that one model is trained on easy samples and the other on hard samples. In use cases where data availability is limited, it would also be possible to apply different augmentations for each model or to train each model on a common basis (e.g., 80% of the images) and only vary a small share of images.

Models were validated on the validation set and finally tested on the test set. That way, we obtained an EfficientNet-B0 model with an accuracy of ∼0.88 and a ResNet model with an accuracy of ∼0.85.

Based on the models trained, we implemented XAI and UQ to enhance reliability of the baseline models. In particular, we used MC dropout for the purpose of UQ and Grad-CAM as the XAI technique. In practice, other XAI and UQ methods may also be used. MC dropout is suitable for this study as it can be integrated in models easily after training and is theoretically sound. For other methods, model training may be affected. For example, in the case of EDL, a targeted loss function is applied [26]. Grad-CAM was chosen since it is a well established standard method for image data and allows for the intuitive understanding of the explanation also by non-experts [21]. In our GitHub repository, we added an explanation generated by Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) [54]. We found that SHAP leads to similar explanations to Grad-CAM.

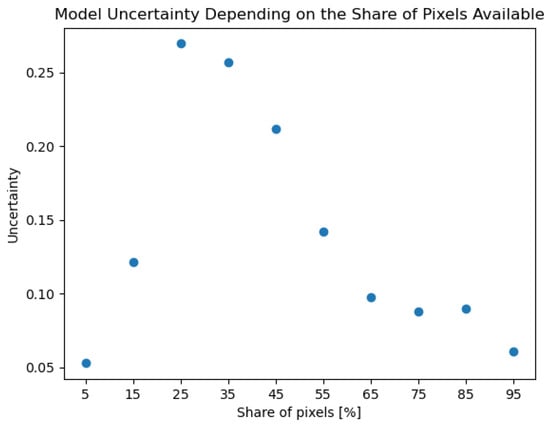

We used saliency maps in order to find out if a model relies on certain pixels too strongly. In particular, we calculated the gradients for each image and then made predictions on these images using just a certain share of the most relevant pixels. The share of pixels was increased gradually, and the model uncertainty was calculated. The results for the ResNet18 model are visualized in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Development of ResNet18 model uncertainty as the share of pixels available for classification increases. Uncertainty increases from ∼0.05 to ∼0.28 until ∼25% of pixels are available and decreases to baseline afterwards.

It can be seen from Figure 8 that uncertainty increases from ∼0.05 to ∼0.28 with an increase in the share of pixels from ∼5% to ∼25%. Afterwards, it decreases to the level of ∼0.05 again. This behavior is exactly what can be expected from a reliable model. When the model sees only few pixels, it cannot identify the images and is certain of that. When the number of pixels increases, the model can slowly recognize the image but is uncertain. When the number of pixels increases further, the model gets more certain of the image class. We observed similar behavior for the EfficientNet-B0 model. The plot is available in our GitHub repository.

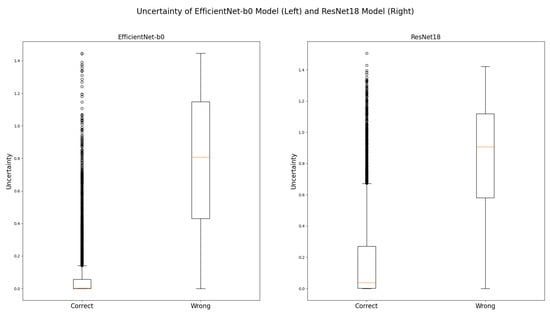

In the next step, we examined how the model uncertainties are distributed within the training samples and defined thresholds based on that. The distribution of model uncertainties on wrong and correct predictions for the EfficientNet-B0 model and the ResNet18 model are visualized in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Distribution of uncertainties on correct and wrong predictions for EfficientNet-B0 model (left) and ResNet18 model (right); clear separation between correct and wrong predictions for both models.

It can be seen from Figure 9 that the uncertainty for both models on correct predictions is close to zero in most cases. In contrast, uncertainty on wrong predictions is mostly higher. Correct and wrong predictions can be separated well by using uncertainty.

For both models, we used the upper fence in the box plot for correct predictions as threshold for uncertain decisions. However, it has to be noted that the separation is not perfect. Especially in the case of the ResNet18 model, there is an overlap between uncertainties on wrong predictions and our thresholds. This may lead to some images for which the model predicts wrongly being not considered by the score. For the final system, the score should be adapted depending on the potential risks.

4.3. Validation—Iteratively Improving the Baseline

Using the baseline models as well as the XAI and UQ implementation, we proceeded with the Validation phase of the R4VR-framework. To do so, we used the images from the test dataset. To each of these images, we applied the models, generated the explanation, and computed uncertainty. All images for which either the models predicted differently or the uncertainty of at least one model exceeded the predefined threshold were filtered automatically. These mechanisms were triggered 2921 times. That way, 1665 unique images were identified. The exact number of images per class identified by each mechanism is documented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Number of images per class that triggered a certain warning. Percentage in brackets indicates relation within the class. The highest model uncertainty was found for images of the class “crazing”.

Taking a closer look at these statistics reveals that both models show high uncertainty with regard to images of classes “crazing”, which is the class with the fewest samples in the dataset. These insights can already be important for training, as they show which images should be included into training more.

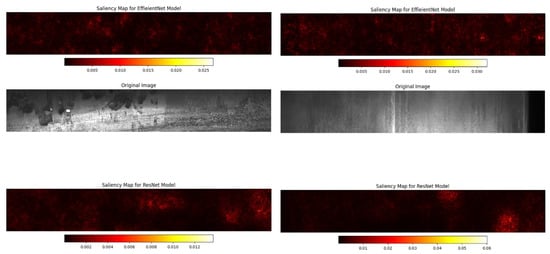

To obtain deeper insights into the reasons for the high uncertainty with regard to these images, we visualized the explanations for the images filtered by warning mechanisms. An explanation for an image where no warning was triggered (left visualization) and an image where both models were uncertain but predicted identically (right visualization) is shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Saliency maps for an image where no warnings were triggered (left visualization) and an image where both models were uncertain (right visualization). For the image where no warning was triggered, both models highlight the region in the image where the defect is located. For the image where both models were uncertain, no specific regions in the image are highlighted by the models.

The image where both models were certain shows that the models highlight the region in the image where the defect is located as relevant. For the image where both models were uncertain, this is not the case. Here, the models highlight no specific regions in the image.

The insight about the models’ focus is particularly relevant for examination of all images that were not marked by the automatic warning mechanisms. We examined these images and filtered all images where the explanations of the models do not focus on the region in the image that shows the defect. That way, we identify 67 more images.

We examined the images identified by the warning mechanisms as well as the images identified manually in more detail and looked for common patterns in the images. Most of the images appear to have been taken under poor lighting conditions. We observed overexposure, underexposure, but also a high gradient in exposure. An example is shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Image for which models are uncertain. High gradient in exposure.

To verify our first impression, we defined metrics to identify overexposure, underexposure, but also high gradient in exposure. We observed that ∼34.3 of the images flagged by warning mechanisms show unusual exposure. For the normal images, this is the case only in ∼2.4% of the cases. This indicates that exposure is an important factor for model performance. However, we cannot rule out that there are other factors that contribute to the observed errors. Factors such as defect variability, label noise, or background texture may have an impact. Nevertheless, we focused on exposure in the first step as it is a common characteristic of many images filtered by warning mechanisms.

The insights regarding exposure suggest different approaches for model improvement. In real-world use cases, it is possible to start on the hardware level. The camera settings or the lightning conditions could be adapted. Also, preprocessing is a possibility to overcome the issue with exposure. Methods such as histogram equalization or illumination normalization can lead to enhanced model performance. Finally, the issues can be addressed on the training level. Data augmentation, selection of model architectures, but also the fine-tuning of the model on hard samples is possible.

In a first step, we focused on the training level approach. We tried to improve the models by augmentation and fine-tuning on hard samples. The approach is useful, as it requires no changes to the existing inspection setup and can be integrated easily into a generic training pipeline. We retrained the models using the common images but also images with augmentation. That way, we improved accuracy of the EfficientNet-B0 model to ∼0.97 and the accuracy of ResNet18 to ∼0.98. These values compare well to leading solutions (https://www.kaggle.com/competitions/severstal-steel-defect-detection/leaderboard, accessed on 10 December 2025) handed in to the original challenge. Other methods from the literature report accuracy rates between ∼0.80 and ∼0.90 [48,55,56,57].

At this point, we want to highlight the fact that the iteration of model improvement and manual validation may be conducted several times. Depending on the potential risks and model performance, more than one step of model improvement may be necessary.

4.4. Verification—What Is the Model Capable of?

For the readily developed model, we conducted Verification, the final step of the development phase. To do so, we first of all regarded the characteristics of the data used for training. Obviously, the model is only applicable to images which show defect types that were already seen in training. Also, the model has to be applied to grayscale images of shape 1600 × 256, and the preprocessing of images has to be conducted as we did in training.

Based on the insights from the Validation phase, we took a closer look at the brightness of the images. We divided the validation images into different sets based on brightness and calculated accuracy and confusion matrices for these specific sets. That way, targeted upper and lower brightness were defined for each class. These values refer to the predicted class of the model. Once a model predicts a certain class and the class-specific limits are exceeded, the model prediction has to be checked manually. Similarly, we defined class-specific thresholds for uncertainty for each model.

Using the defined thresholds, we tested the model on all images from the test dataset. We obtained a combined accuracy of ∼96%. Of the wrongly classified images, only six images were not detected by the warning mechanisms, where four of these undetected images belonged to class 0 (no defect), meaning that only two defective parts (∼0.03%) had passed quality inspection. For production settings, where strict requirements regarding quality have to be met, the system, therefore, provides high safety standards.

4.5. Guidelines for Model Deployment and Monitoring

As we do not have a real production environment where the model can be deployed, we provide some guidelines for deployment based on the insights from Section 4.2, Section 4.3 and Section 4.4.

- Verification

As a first step when applying the model, it has to be verified if the model may be applied at all. In the case of our model for steel surface inspection, this means that the shape of the images has to be checked. Also, it has to be ensured that a grayscale image is used, and the brightness of the images has to be checked against the thresholds. All these steps can be conducted automatically. If a criterion is not met, a human expert has to be informed.

- Validation

If the requirements from Verification are met, the models can be applied to the image. The predictions are then compared against each other, and the uncertainties are calculated. If at least one model uncertainty is too high or the models predict differently, operator intervention is required.

- Reliability

In the case of our inspection setting, random model predictions and explanations should be checked regularly (e.g., once per shift) by a human expert. As soon as they notice any inconsistencies, the system has to enter the development phase for improvement again.

- Differentiation Based on Risk

Finally, we want to provide a brief guide on how to perform differentiation in model application based on the potential risks. First of all, it is possible to adapt the uncertainty thresholds for warnings. Also, the thresholds for allowed ranges for deploying the model can be adjusted. These adaptions can also be based on the risk of certain misclassification types. For example, thresholds for the individual classes can be selected in such a way that the probability of defective parts passing quality inspection is lower, while the probability of good parts being rejected by mistake is higher. Beyond that, it is conceivable to adapt the frequency of operator intervention. For highly critical applications, the operator could be acquired to review a certain number of model predictions every hour.

5. Discussion

We developed practical guidelines for adopting the R4VR-framework in real-world use cases and defined a process for reliable and efficient data collection that is compatible with our guidelines. We showed how these guidelines help to comply with the EU AI Act and demonstrated their applicability using a real-world scenario. Now, we critically discuss the guidelines and the outcomes of the case study.

5.1. Discussion of Methodological Approach

To begin with, we critically examine the methodological approach. In Section 3, we proposed precise guidelines for adopting the R4VR-framework in medical diagnosis and quality control and defined a process for reliable and efficient data collection that is compatible with our guidelines. Our guidelines should be implemented by an interdisciplinary team. On the evaluated dataset, less than 0.1% of images had been misclassified and not detected by the warning mechanisms, suggesting that the combination of UQ and XAI can strongly reduce undetected errors in this setting and enhance safety that way.

Our guidelines satisfy key obligations under the EU AI Act: risk management (Article 9, EU AI Act [10]), data governance (Article 10, EU AI Act [10]), technical documentation (Article 11, EU AI Act [10]), record keeping (Article 12, EU AI Act [10]), transparency and provision of information to deployers (Article 13, EU AI Act [10]), human oversight (Article 14, EU AI Act [10]), and accuracy and robustness (Article 15, EU AI Act [10]). However, requirements for post-market monitoring (Article 16, EU AI Act [10]) and incident reporting (Article 62, EU AI Act [10]) are only covered indirectly. Also, we did not provide exact guidelines on how to conduct documentation and logging. However, for regulatory compliance, it is important to regard the appropriate standards. Future work should, therefore, discover how post-market monitoring and incident reporting can be integrated into the framework and how the R4VR-framework helps to go through the actual regulatory processes.

For data collection, we proposed an iterative human-in-the-loop approach. The workflow ensures the generation of high-quality datasets that incorporate the knowledge of human domain experts to the greatest extent possible. Due to the iterative retraining of models, it is a self-accelerating process where the need for human intervention decreases progressively. However, the method assumes availability of domain experts for initial labeling, which may not scale in all industries.

Our guidelines for adoption of the R4VR-framework also emphasize human intervention. Full automation is not the aim. However, our guidelines couple explainability with uncertainty-driven decision thresholds, enabling selective human review rather than full manual inspection. Also, by coupling Grad-CAM explanations with MC dropout uncertainty estimates, we ensured interpretability and reliability at both the pixel and prediction levels.

A limitation of the approach is the fact that it currently does not address long-term data drifts. Data drifts can only be detected indirectly by high model uncertainty or during human supervision phases. Future work should, therefore, integrate methods for detection of data drifts in the deployment and monitoring phase.

Regarding the workflow proposed in medical use cases, every image must be reviewed by a human expert. That may seem laborious. However, the integration of a targeted user interface along with XAI and UQ mechanisms allows physicians to assess images more efficiently and reduces the end user’s workload while ensuring high reliability.

For visual inspection tasks, human review is only required at regular intervals. The integration of XAI and UQ mechanisms increases system transparency and allows human operators to detect model malfunctions early. It is important to note that the workflow cannot guarantee 100% accuracy. However, we provided opportunities for differentiation based on the risks involved. For more critical use cases, it is possible to increase the operator’s interaction effort to maximize reliability. This approach offers a scalable solution for deploying ML in high-stake visual inspection tasks, where the level of autonomy can be adjusted according to the severity of the risks. Nonetheless, safety assurance in real-world deployment requires governance measures such as audit trails, access control, and the versioning of retrained models. Future iterations could integrate automated anomaly monitoring and explainability audits to maintain operational safety over time.

5.2. Discussion of Results

To demonstrate how the guidelines can be implemented in practice, we considered a use case from visual inspection, namely, steel surface inspection. At this point, it has to be mentioned that all results observed only apply to our specific use case. Additional exploratory experiments (which are available in our GitHub repository) on a similar but smaller dataset show similar trends and support the robustness of our approach. However, for other domains and datasets, other results may be observed.

Regarding data collection, we demonstrated that a self-accelerating process where the model accuracy increases progressively while the manual effort decreases emerges. Beyond that, we showed how to harness XAI in every phase of the ML system’s life cycle. That way, we established a system that allows for precise inspection of steel surfaces where less than 0.1% of images are classified wrongly and not detected by warning mechanisms. Also, the system can be adapted flexibly to the severity of potential risks by increasing or decreasing the intervention effort for human experts.

Regarding data collection, we pointed out the trade-off between manual effort and computing costs. More frequent retraining reduces manual labeling effort but leads to higher computing costs. This trade-off may be addressed by an adaptive approach where the retraining frequency decreases as the model performance increases in future work.

Currently, the experimental validation is limited to two open datasets from steel surfaces, which may not reflect real production variability. Also, we did not apply the system in a real production scenario but only provided a theoretical description of how deployment in production scenarios could be implemented. Latency, throughput, and operator acceptance, therefore, remain open research questions. Future work should prove the validity of the results in other domains and real production scenarios. That way, extended insights into practical applicability and limitations can be gained.

Another limitation of the study is its focus on MC dropout as a method of UQ and Grad-CAM as a method of XAI. In the course of this study, we focused on MC dropout as it can be integrated into trained models without big adaptions. Grad-CAM is useful as it allows for the intuitive understanding of the explanations. However, the R4VR-framework does not prescribe usage of these specific methods. There is a variety of XAI techniques (e.g., LIME, SHAP, and LRP) and UQ methods (e.g., ensembles, DUQ, and EDL) that could be used instead. Future works should take such methods into account in order to provide comparative results on performance of the R4VR-framework when applied with different methods of XAI and UQ.

5.3. Implications for Practice

Overall, we showed how to create a very safe system for visual inspection that could be production-ready under similar conditions. The framework can offer support for compliance with the EU AI Act. Also, it can guide practitioners in industries like automotive, steel, and semiconductor manufacturing to integrate ML-based inspection systems safely. Its various mechanisms for ensuring safety, trustworthiness, and transparency of the final decisions can contribute to compliance with the EU AI Act and safe systems. Also, this can contribute to the adoption of ML-based systems for medical diagnosis. The modular structure allows for gradual automation: starting with full human verification and moving toward confidence-based autonomy. The open-source code base facilitates custom adaptation of explainability and uncertainty modules across domains. That way, we provide a practical resource supporting compliance with the EU AI Act.

6. Conclusions

In this work, we translated the R4VR-framework into a set of practical guidelines that enable the development of ML systems suitable for safety-critical decision environments. By extending the framework with a structured and efficient data collection process, we showed how human oversight, data governance, and risk management can be operationalized in a way consistent with the requirements of the EU AI Act. Therefore, we closed an important gap between high-level, trustworthy ML principles and their concrete implementation in industrial and medical contexts.

Using the example of steel surface inspection, we demonstrated that these guidelines can be applied in practice to build a highly reliable inspection system with effective warning mechanisms. The HiL data collection process led to a self-accelerating workflow in which manual effort decreased steadily as the system improved. Based on the curated dataset, we trained models that reached high accuracy, and less than 0.1% of images had been classified wrongly and not detected by the system’s uncertainty- and explanation-based warning mechanisms. The resulting workflow can be adapted flexibly to the risk profile of a given application, allowing for selective human involvement where necessary without compromising safety.

Taken together, the proposed guidelines provide a rigorous and practicable foundation for deploying ML in high-stake scenarios—ranging from industrial quality control to medical diagnosis—where reliability, transparency, and human oversight are indispensable. Future work will focus on deploying the system in real inspection environments and comparing its performance and safety characteristics with fully automated alternatives.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.R. and J.W.; methodology, C.R. and J.W.; software, J.W.; validation, C.R.; formal analysis, J.W.; investigation, J.W.; resources, C.R. and J.W.; data curation, J.W.; writing—original draft preparation, J.W.; writing—review and editing, C.R.; visualization, J.W.; supervision, C.R.; project administration, C.R.; funding acquisition, C.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research study received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available at Dataset Ninja (https://datasetninja.com/severstal, accessed on 6 December 2025).

Acknowledgments

LLMs were used for editorial purposes in this manuscript, and all outputs were inspected by the authors to ensure accuracy and originality. No content was generated by the LLM that changes the scientific claims, methodology, or results. The authors remain entirely responsible for the originality, accuracy, and integrity of all content in the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Madan, M.; Reich, C. Strengthening Small Object Detection in Adapted RT-DETR Through Robust Enhancements. Electronics 2025, 14, 3830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; McDermid, J.; Lawton, T.; Habli, I. The Role of Explainability in Assuring Safety of Machine Learning in Healthcare. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. 2022, 10, 1746–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirian, S.; Carlson, L.A.; Gong, M.F.; Lohse, I.; Weiss, K.R.; Plate, J.F.; Tafti, A.P. Explainable AI in Orthopedics: Challenges, Opportunities, and Prospects. In Proceedings of the 2023 Congress in Computer Science, Computer Engineering, & Applied Computing (CSCE), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 24–27 July 2023; pp. 1374–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renjith, V.; Judith, J. A Review on Explainable Artificial Intelligence for Gastrointestinal Cancer using Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 2023 Annual International Conference on Emerging Research Areas: International Conference on Intelligent Systems (AICERA/ICIS), Kerala, India, 16–18 November 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plevris, V. Assessing uncertainty in image-based monitoring: Addressing false positives, false negatives, and base rate bias in structural health evaluation. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2025, 39, 959–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwanatha, C.R.; Asha, V.; Saju, B.; Suma, N.; Mrudhula Reddy, T.R.; Sumanth, K.M. Face Recognition and Identification Using Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 2023 Third International Conference on Advances in Electrical, Computing, Communication and Sustainable Technologies (ICAECT), Bhilai, India, 5–6 January 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adadi, A.; Berrada Khan, M. Peeking inside the black-box: A survey on explainable artificial intelligence (XAI). IEEE Access 2018, 6, 52138–52160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, D.; Uslu, S.; Rittichier, K.J.; Durresi, A. Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence: A Review. ACM Comput. Surv. 2022, 55, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiggerthale, J.; Reich, C. Explainable Machine Learning in Critical Decision Systems: Ensuring Safe Application and Correctness. AI 2024, 5, 2864–2896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament. EU AI Act: First Regulation on Artificial Intelligence. 2023. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/topics/en/article/20230601STO93804/eu-ai-act-first-regulation-on-artificial-intelligence (accessed on 28 September 2024).

- Mahajan, P.; Aujla, G.S.; Krishna, C.R. Explainable Edge Computing in a Distributed AI - Powered Autonomous Vehicular Networks. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Communications Workshops (ICC Workshops), Denver, CO, USA, 9–13 June 2024; pp. 1195–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Vijayshankar, S.; Macwan, R. Demystifying Cyberattacks: Potential for Securing Energy Systems with Explainable AI. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Computing, Networking and Communications (ICNC), Big Island, HI, USA, 19–22 February 2024; pp. 430–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal-Houshmand, S.; Papamartzivanos, D.; Homayoun, S.; Veliou, E.; Jensen, C.D.; Voulodimos, A.; Giannetsos, T. Explainable Artificial Intelligence to Enhance Data Trustworthiness in Crowd-Sensing Systems. In Proceedings of the 2023 19th International Conference on Distributed Computing in Smart Systems and the Internet of Things (DCOSS-IoT), Pafos, Cyprus, 19–21 June 2023; pp. 568–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadasi, N.; Piran, M.; Valdez, R.S.; Baek, S.; Moghaddasi, N.; Polmateer, T.L.; Lambert, J.H. Process Quality Assurance of Artificial Intelligence in Medical Diagnosis. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Intelligent Systems and Computer Vision (ISCV), Fez, Morocco, 8–10 May 2024; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rožman, J.; Hagras, H.; Andreu-Perez, J.; Clarke, D.; Müeller, B.; Fitz, S. A Type-2 Fuzzy Logic Based Explainable AI Approach for the Easy Calibration of AI models in IoT Environments. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Fuzzy Systems (FUZZ-IEEE), Luxembourg, 11–14 July 2021; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shtayat, M.M.; Hasan, M.K.; Sulaiman, R.; Islam, S.; Khan, A.U.R. An Explainable Ensemble Deep Learning Approach for Intrusion Detection in Industrial Internet of Things. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 115047–115061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherry, L.; Baldo, J.; Berlin, B. Design of Flight Guidance and Control Systems Using Explainable AI. In Proceedings of the 2021 Integrated Communications Navigation and Surveillance Conference (ICNS), Virtual Event, 19–23 April 2021; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]