Techno-Economic Assessment of Hydrogen and CO2 Recovery from Broccoli Waste via Dark Fermentation and Biorefinery Modeling

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

2.2. Substrate

2.3. Inoculum Source

2.4. Dark Fermentation Experiments for Biohydrogen Production

Statistical Analysis

2.5. Analytical Methods

2.6. Tecno-Economic Analysis of Broccoli Biorefineries

2.6.1. Cryogenization

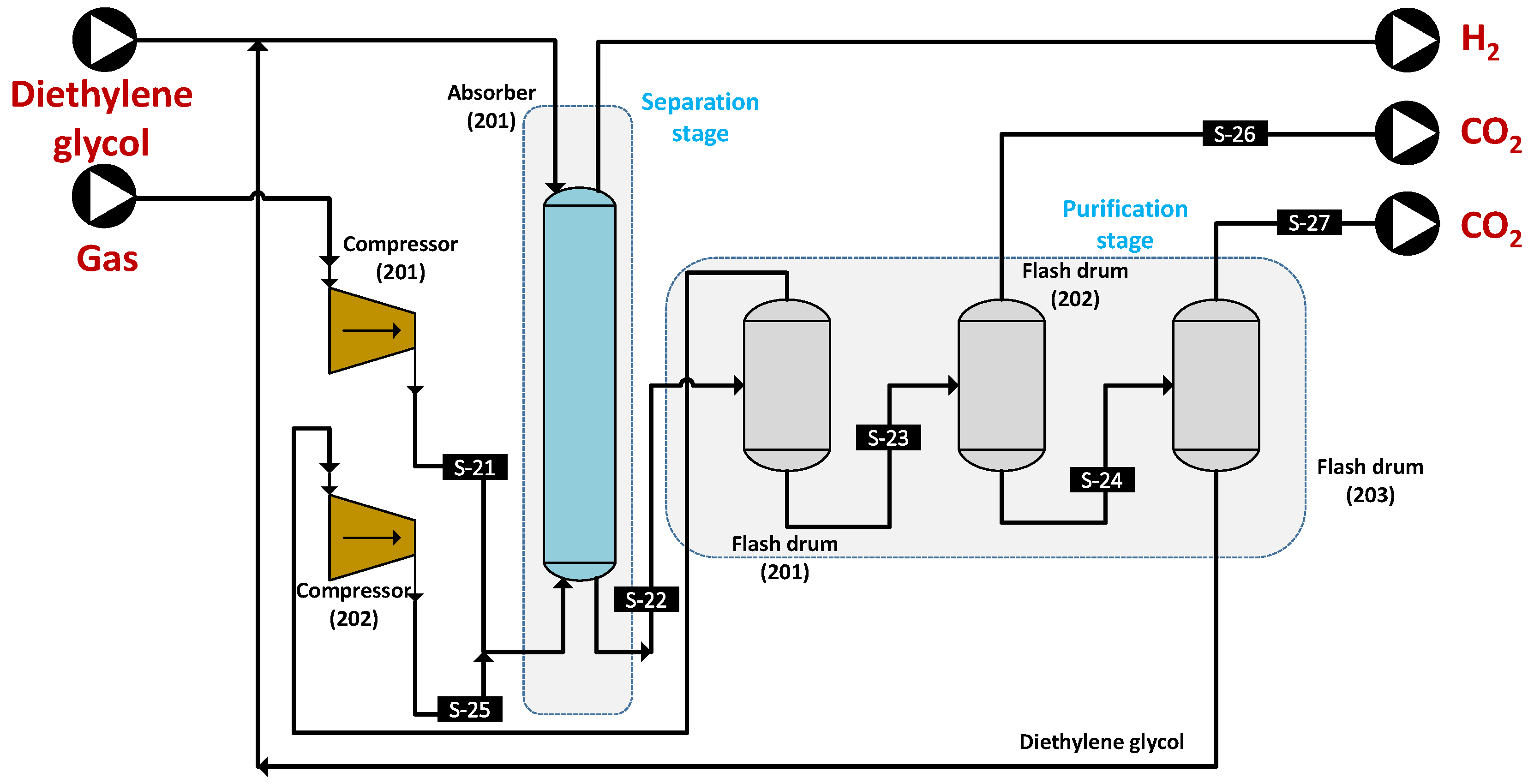

2.6.2. Absorption

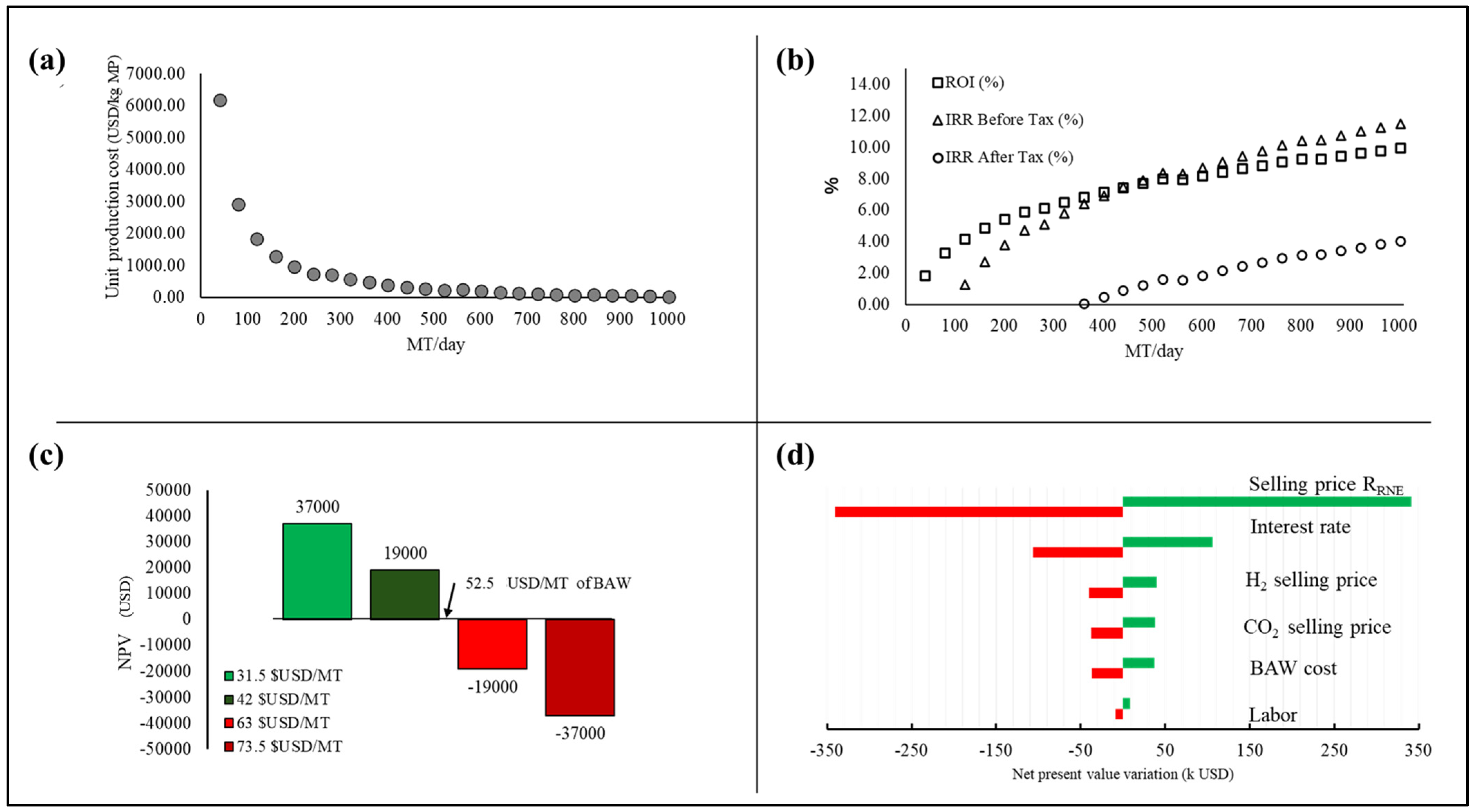

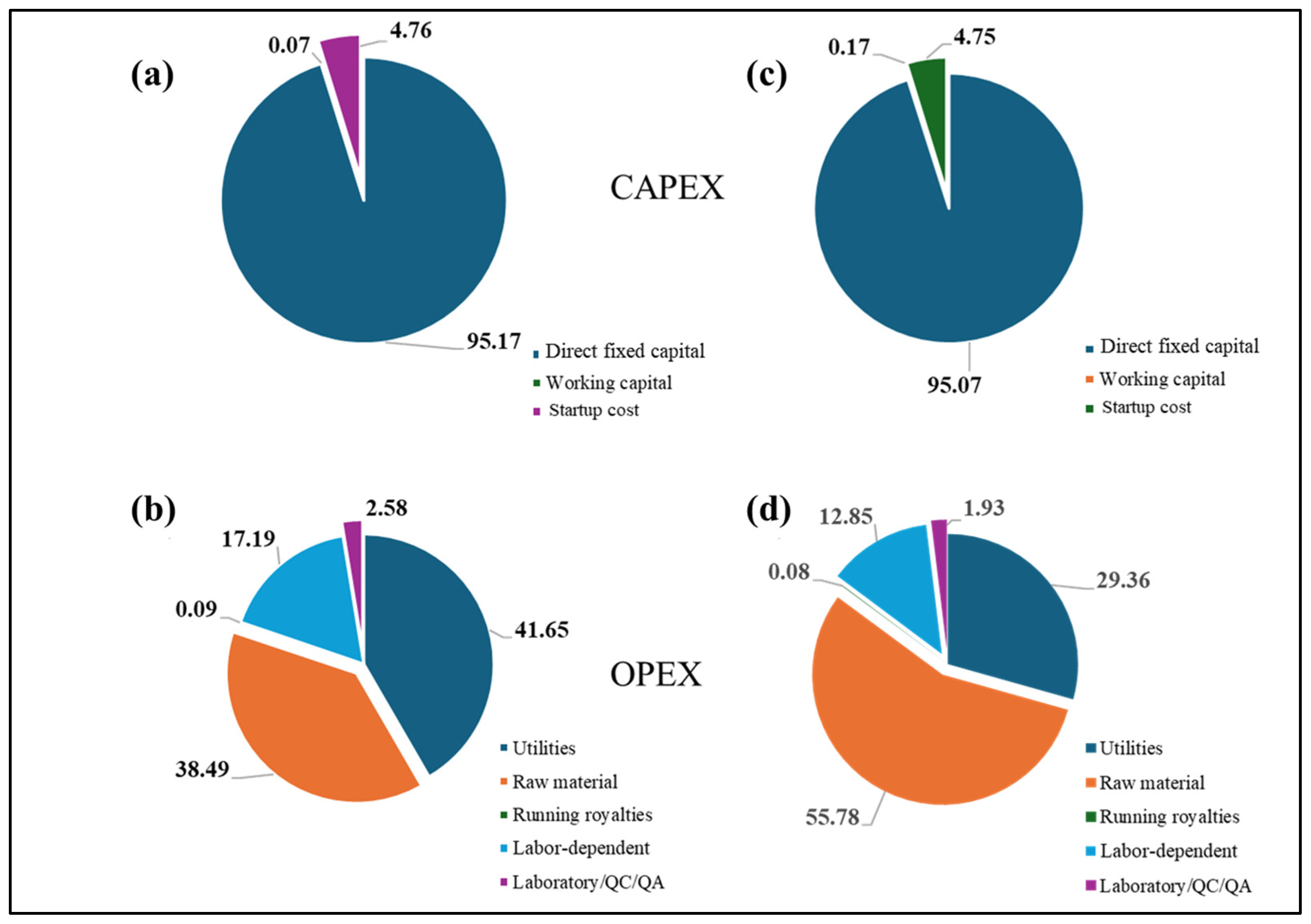

2.7. Economic Evaluation

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of the Source: Volatile and Total Solids of Broccoli Leaves and Stems

3.2. Dark Fermentation Experiments

Statistical Analysis Results

3.3. Biorefinery Simulation

3.3.1. Cryogenic Process Evaluation

3.3.2. Absorption Process Evaluation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Name | Type | Units | Size (Capacity) | Unit Price (USD/Unit) | Total Price (USD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-101 | Absorber | 1 | 1931.65 | L | 49,000 | 49,000 |

| AD-102 | Anaerobic Digester | 1 | 17,971.08 | m3 | 10,174,000 | 10,174,000 |

| G-101 | Centrifugal Compressor | 1 | 13.56 | kW | 85,000 | 85,000 |

| G-102 | Centrifugal Compressor | 1 | 15.37 | kW | 85,000 | 85,000 |

| V-103 | Flash Drum | 1 | 406.20 | L | 5000 | 5000 |

| V-101 | Flash Drum | 1 | 430.28 | L | 5000 | 5000 |

| V-102 | Flash Drum | 1 | 422.88 | L | 5000 | 5000 |

| RVF-101 | Rotary Vaccum Filter | 4 | 162.62 | m2 | 397,000 | 1,588,000 |

| SC-103 | Screw Conveyor | 2 | 15.00 | m | 92,000 | 184,000 |

| SR-102 | Shredder | 1 | 41.66 | MT/h | 286,000 | 286,000 |

| Name | Type | Units | Size (Capacity) | Unit Price (USD/Unit) | Total Price (USD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD-101 | Anaerobic Digester | 1 | 18,033.73 | m3 | 10,196,000 | 10,196,000 |

| G-102 | Centrifugal Compressor | 1 | 13.22 | kW | 85,000 | 85,000 |

| G-101 | Centrifugal Compressor | 1 | 1.99 | kW | 85,000 | 85,000 |

| G-103 | Centrifugal Compressor | 1 | 1.89 | kW | 85,000 | 85,000 |

| V-102 | Flash Drum | 1 | 57.05 | L | 2000 | 2000 |

| V-101 | Flash Drum | 1 | 57.05 | L | 2000 | 2000 |

| HX-101 | Heat Exchanger | 1 | 0.04 | m2 | 4000 | 4000 |

| RVF-101 | Rotary Vaccum Filter | 4 | 163.19 | m2 | 398,000 | 1,592,000 |

| SC-103 | Screw Conveyor | 2 | 15.00 | m | 93,000 | 186,000 |

| SR-102 | Shredder | 1 | 41.81 | MT/h | 287,000 | 287,000 |

References

- Holechek, J.L.; Geli, H.; Sawalhah, M.; Valdez, R. A Global Assessment: Can Renewable Energy Replace Fossil Fuels by 2050? Sustainability 2025, 14, 4792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merajul Islam, M.; Nafees, A. Transforming biomass into sustainable biohydrogen: An in-depth analysis. RSC Sustain. 2025, 3, 4250–4297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Chen, B.; Wang, T.; Zhao, X. A promising technical route for converting lignocellulose to bio-jet fuels based on bioconversion of biomass and coupling of aqueous ethanol: A techno-economic assessment. Fuel 2025, 381, 133670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, M.; Ciudad, G.; Cárdenas, J.P.; Medina, C.; Salas, A.; Oñate, A.; Pincheira, G.; Attia, S.; Tuninetti, V. Towards the development of performance-efficient compressed earth blocks from industrial and agro-industrial by-products. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 194, 114323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez-Vazquez, I.; Acevedo-Benítez, J.A.; Hernández-Santiago, C. Distribution and potential of bioenergy resources from agricultural activities in Mexico. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2010, 14, 2147–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, C.; Escamilla-Alvarado, C.; Sánchez, A. Wheat straw, corn stover, sugarcane, and Agave biomasses: Chemical properties, availability, and cellulosic-bioethanol production potential in Mexico. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefining 2019, 13, 1143–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Guerrero, C.E.; Sanchez, A.; Vázquez-Núñez, E. Energy potential of agricultural residues generated in Mexico and their use for butanol and electricity production under a biorefinery configuration. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 28607–28622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Chavez, J.J.; Arenas-Grimaldo, C.; Amaya-Delgado, L. Sotol bagasse (Dasylirion sp.) as a novel feedstock to produce bioethanol 2G: Bioprocess design and biomass characterization. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 178, 114571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Nieves, D.; Rostro Alanís, M.; de la Cruz Quiroz, R.; Ruiz, H.A.; Iqbal, H.; Parra-Saldíva, R. Current status and future trends of bioethanol production from agro-industrial wastes in Mexico. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 102, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veitía-de-Armas, L.; Reynel-Ávila, H.; Villalobos-Delgado, F.J.; Duran-Valle, C.; Adame-Pereira, M.; Bonilla-Petriciolet, A. A circular economy approach to produce low-cost biodiesel using agro-industrial and packing wastes from Mexico: Valorization, homogeneous and heterogeneous reaction routes and product characterization. Renew. Energy 2024, 237, 121684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SIAP. México produjo 567 mil toneladas de brócoli en 2017. México produjo 567 mil toneladas de brócoli en 2017. 2017. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/agricultura%7Cdgsiap/es/articulos/mexico-produjo-567-mil-toneladas-de-brocoli-en-2017 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Manríquez-Zúñiga, A.N.; Rosillo De La Torre, A.; Valdés-Santiago, L. Broccoli Leaves (Brassica oleracea var. italica) as a Source of Bioactive Compounds and Chemical Building Blocks: Optimal Extraction Using Dynamic Maceration and Life Cycle Assessment. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berndtsson, E.; Andersson, R.; Johansson, E.; Olsson, M. Side Streams of Broccoli Leaves: A Climate Smart and Healthy Food Ingredient. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, S.; Pandit, S.; Roy, C.; Obaidur, S.; Kumar, A.R.; Saeed, M.; Kumar, A.; Sharma, K.; Ranjan, N. Bioenergy recovery from jackfruit waste via biohydrogen production through dark fermentation and power generation through stacked microbial fuel cells. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 102, 845–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lufan, P.; Cardozo, R. Biohydrogen production from residual biomass: The potential of wheat, corn, rice, and barley straw−recent advances. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 432, 132638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez-Guzmán, B.E.; Rios-Del Toro, E.; Cardenas-López, R.; Méndez-Acosta, H.; González-Álvarez, V.; Arreola-Vargas, J. Enhancing biohydrogen production from Agave tequilana bagasse: Detoxified vs. Undetoxified acid hydrolysates. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 276, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudek, K.; Buitrón, G.; Valdez-Vazquez, I. Nutrient influence on acidogenesis and native microbial community of Agave bagasse. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 170, 113751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez-Vazquez, I.; Pérez-Rangel, M.; Tapia, A. Hydrogen and butanol production from native wheat straw by synthetic microbial consortia integrated by species of Enterococcus and Clostridium. Fuel 2015, 159, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva-Galindo, E.; Vital-Jácome, M.; Moreno-Andrade, I. Dark fermentation for H2 production from food waste and novel strategies for its enhancement. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 9957–9970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obiora, N.K.; Ujah, C.O.; Asadu, C.O.; Kolawole, F.O.; Ekwueme, B.N. Production of hydrogen energy from biomass: Prospects and challenges. Green Technol. Sustain. 2024, 2, 100100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, A.; Sun, P.; Liu, X.; Delgado, H.E.; Sun, L.; Elgowainy, A. Techno-economic and life cycle analysis of bio-hydrogen production using bio-based waste streams through the integration of dark fermentation and microbial electrolysis. Green Chem. 2025, 27, 6213–6231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elerakey, N.; Abdel-Hamied, M.; Hawary, H. Mathematical modeling of biohydrogen production via dark fermentation of fruit peel wastes by Clostridium butyricum NE95. BMC Biotechnol. 2024, 24, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez, M.P.; Villanueva-Galindo, E.; Moreno-Andrade, I. Enhanced hydrogen production from food waste via bioaugmentation with Clostridium and Lactobacillus. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 2025, 15, 27501–27513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inocencio-García, P.J.; Cardona Alzate, C.A. Techno-Economic Comparison of CO2 Valorization Through Chemical and Biotechnological Conversion. Waste Biomass Valor. 2025, 16, 3969–3985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ahn, H. Process swing adsorption with selective purge gas recirculation (PSA-SPUR): Adsorption process technology optimised for separation of heavy component from a gas mixture and its design for CO2 capture through Equilibrium Theory analysis. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 358, 130356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartini Suhaimi, N.; Jusoh, N.; Kar Yap, B.; Nur-E-Alam, M.; Soraya Sambudi, N.; Lai, L.S.; Izzuddin Adnan, A. Amine-functionalized MOF-based hybrid membranes for CO2 separation: Molecular interactions and separation performance. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2025, 17, 100542. [Google Scholar]

- Tuinier, M.J.; Hamers, H.P.; Annaland, M. Techno-economic evaluation of cryogenic CO2 capture—A comparison with absorption and membrane technology. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2011, 5, 1559–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byung-Moon, J.; Kim, J.; Young-Nam, K. Enhanced CO2/CH4 separation by solvent-based pressure swing absorption: Effects of solvent composition and concentration in ternary system. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 1, 166415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, G.; Yu, P.; Duan, S.; Chen, H.; Han, J. Design and analysis of cryogenic CO2 separation from a CO2-rich mixture. Energy Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 2253–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.H.; Ashkanani, H.E.; Morsi, B.I.; Siefert, N.S. Physical solvents and techno-economic analysis for pre-combustion CO2 capture: A review. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2022, 118, 103694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Liang, F.; Yang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, K.; Liu, W. An Improved CO2 Separation and Purification System Based on Cryogenic Separation and Distillation Theory. Energies 2014, 7, 3484–3502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, K.; Boyer, L.; Almoucachar, D.; Poulain, B.; Cloarec, E.; Magnon, C.; de Meyer, F. CO2 and H2S absorption in aqueous MDEA with ethylene glycol: Electrolyte NRTL, rate-based process model and pilot plant experimental validation. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 451, 138948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, J.; Villadsen, J. Bioreaction Engineering Principles, 3rd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, A.; Valdez-Vazquez, I.; Soto, A.; Sánchez, S.; Tavarez, D. Lignocellulosic n-butanol co-production in an advanced biorefinery using mixed cultures. Biomass Bioenergy 2017, 102, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, A.; Mohd Shariff, A.; Sufian, S.; Ayoub, M.; Lal, B. Phase identification of natural gas system with high CO2 content through simulation approach using Peng-Robinson model. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 458, 012068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavini, T.D.; Ali, M.-D.I.; Muhammad, W.S. Economic Evaluation of Selexol-Based CO2 Capture Process for a Cement Plant Using Post—Combustion Technology. Int. J. Sci. Res. Sci. Technol. 2015, 1, 194–203. [Google Scholar]

- Asgharian, H.; Pujol Duran, A.; Yahyaee, A.; Pignataro, V.; Pagh Nielsen, M.; Iov, F.; Liso, V. Sustainable urea production via CO2 capture from cement plants: A techno-economic analysis with focus on process heat integration and electrification. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 151, 150154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, A.; Sevilla-Güitrón, V.; Magaña, G.; Gutierrez, L. Parametric analysis of total costs and energy efficiency of 2G enzymatic ethanol production. Fuel 2013, 113, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seider, W.D.; Lewin, D.R.; Seader, J.D.; Widagdo, S.; Gani, R.; Ming, K. Product and Process Design Principles: Synthesis, Analysis, and Evaluation, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; p. 456. [Google Scholar]

- Diethylene Glycol Price Trend, Index, Chart, Database. 2024. Available online: https://www.procurementresource.com/resource-center/diethylene-glycol-price-trends (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Investment Research Data, Bloomberg Professional Service. 2025. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/professional/products/data/enterprise-catalog/investment-research-data/ (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Ajayi-Banji, A.A.; Rahman, S.; Sunoj, S.; Igathinathane, C. Impact of corn stover particle size and C/N ratio on reactor performance in solid-state anaerobic co-digestion with dairy manure. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2020, 70, 436–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir Khan, M.; Brulé, M.; Maurer, C.; Argyropoulos, D.; Müller, J.; Oechsner, H. Batch anaerobic digestion of banana waste—Energy potential and modelling of methane production kinetics. Agric. Eng. Int. CIGR J. 2016, 18, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Nandiyanto, A.; Azizah, N.; Chelvina, G.; Girsang, S. Optimal Design and Techno-Economic Analysis for Corncob Particles Briquettes: A Literature Review of the Utilization of Agricultural Waste and Analysis Calculation. Appl. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2022, 15, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, D.; Kitiborwornkul, N.; Sriariyanun, M.; Keerthi, K. A Review on Chemical Pretreatment Methods of Lignocellulosic Biomass: Recent Advances and Progress. Appl. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2022, 15, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Experiment | Leaf (g) | Stem (g) |

|---|---|---|

| E1 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| E2 | 0.5 | 2.0 |

| E3 | 2.0 | 0.5 |

| Parameter | Scenario A | Scenario B |

|---|---|---|

| Mole flow (kmol/day) | 169.82 | 72.84 |

| Pressure kPa | 101.325 | 101.325 |

| Vapor fraction | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Composition (mol fraction) | ||

| CO2 | 0.5856 | 0.6808 |

| H2 | 0.4143 | 0.3092 |

| Flow | Temperature [°C] | Pressure [kPa] | Mole Fraction [%] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO2 | H2 | |||

| BIOGAS | 36.00 | 101.32 | 69.08 | 30.92 |

| S-11 | 40.00 | 2101.32 | 69.08 | 30.92 |

| S-12 | −30.00 | 2101.32 | 69.08 | 30.92 |

| S-13 | −35.60 | 2101.32 | 69.08 | 30.92 |

| S-14 | −35.60 | 2100.00 | 60.95 | 39.05 |

| S-15 | 42.48 | 5000.00 | 60.95 | 39.05 |

| S-16 | −36.00 | 5000.00 | 60.95 | 39.05 |

| S-17 | −36.00 | 5000.00 | 97.20 | 2.79 |

| S-18 | −35.60 | 2100.00 | 98.55 | 1.45 |

| S-19 | −38.50 | 2100.00 | 97.20 | 2.79 |

| H2 | −36.00 | 5000.00 | 31.01 | 69.09 |

| CO2 | −20.45 | 2100.00 | 97.99 | 2.01 |

| Flow | Temperature [°C] | Pressure [kPa] | Mole Fraction [%] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO2 | H2 | |||

| Gas | 36.00 | 101.32 | 58.56 | 41.44 |

| S-21 | 40.00 | 2500.00 | 58.56 | 41.44 |

| S-22 | −30.00 | 2500.00 | 58.56 | 41.44 |

| S-23 | −35.60 | 2500.00 | 58.56 | 41.44 |

| S-24 | −35.60 | 2500.00 | 52.90 | 47.10 |

| S-25 | 42.88 | 5000.00 | 52.90 | 47.10 |

| S-26 | −36.00 | 5000.00 | 52.90 | 47.10 |

| S-27 | −36.00 | 5000.00 | 97.21 | 2.79 |

| S-28 | −35.60 | 2500.00 | 99.00 | 1.00 |

| S-29 | −38.50 | 2500.00 | 97.21 | 2.79 |

| H2 | −36.00 | 5000.00 | 31.08 | 68.90 |

| CO2 | −20.45 | 2500.00 | 97.21 | 2.08 |

| Flow | Temperature [°C] | Pressure [kPa] | Mole Fraction [%] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO2 | H2 | DEG Solution | |||

| Gas | 36.0 | 101.3 | 69.0800 | 30.9200 | 0.0000 |

| Diethylene glycol | 38.0 | 101.3 | 0.1000 | 0.0000 | 99.9000 |

| S-21 | 40.0 | 2360.0 | 69.0800 | 30.9200 | 0.0000 |

| S-22 | 38.1 | 2360.0 | 22.5000 | 2.4000 | 75.1100 |

| S-23 | 37.7 | 1800.0 | 0.6900 | 0.0023 | 99.3000 |

| S-24 | 38.0 | 980.7 | 0.6900 | 0.0023 | 99.3000 |

| S-25 | 63.8 | 1800.0 | 89.9000 | 10.1000 | 0.0000 |

| S-26 (CO2) | 37.8 | 980.7 | 99.8000 | 0.2000 | 0.0000 |

| S-27 (CO2) | 38.0 | 98.1 | 99.8000 | 0.2000 | 0.0000 |

| H2 | 36.7 | 2360.0 | 0.3000 | 99.7000 | 0.0000 |

| Flow | Temperature [°C] | Pressure [kPa] | Mole Fraction [%] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO2 | H2 | DEG Solution | |||

| BIOGAS | 36.0 | 101.3 | 58.5600 | 41.4400 | 0.0000 |

| DEG solution | 38.0 | 101.3 | 0.1000 | 0.0000 | 99.9000 |

| S-21 | 40.0 | 2360.0 | 58.5600 | 41.4400 | 0.0000 |

| S-22 | 38.1 | 2360.0 | 19.2000 | 3.1800 | 77.5000 |

| S-23 | 37.7 | 1800.0 | 0.6900 | 0.0023 | 99.3000 |

| S-24 | 38.0 | 980.7 | 0.6900 | 0.0023 | 99.3000 |

| S-25 | 63.7 | 1800.0 | 85.2700 | 14.4000 | 0.0000 |

| S-26 (CO2) | 37.8 | 980.7 | 98.2000 | 1.8000 | 0.0000 |

| S-27 (CO2) | 38.0 | 98.1 | 98.2000 | 1.8000 | 0.0000 |

| H2 | 36.7 | 2360.0 | 0.3000 | 99.7000 | 0.0000 |

| Economic Parameter | Cryogenic | Absorption | Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Capital Investment | 92,310,000 | 91,911,000 | USD |

| Operating Cost | 1,366,000 | 1,800,000 | USD/year |

| Net Unit Production Cost | 876.27 | 704.83 | USD/MP Entity |

| Gross Margin | 95.78 | 96.48 | % |

| Return On Investment | 8.63 | 9.84 | % |

| Payback Time | 11.58 | 10.22 | years |

| IRR (After Taxes) | 4 | 4 | % |

| NPV (at 4.0% Interest) | 30,000 | 33,000 | USD |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Molina-Guerrero, C.E.; Valdez-Vazquez, I.; Cruz López, A.; Ibarra-Sánchez, J.d.J.; Álvarez, L.C.B. Techno-Economic Assessment of Hydrogen and CO2 Recovery from Broccoli Waste via Dark Fermentation and Biorefinery Modeling. Processes 2025, 13, 4083. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124083

Molina-Guerrero CE, Valdez-Vazquez I, Cruz López A, Ibarra-Sánchez JdJ, Álvarez LCB. Techno-Economic Assessment of Hydrogen and CO2 Recovery from Broccoli Waste via Dark Fermentation and Biorefinery Modeling. Processes. 2025; 13(12):4083. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124083

Chicago/Turabian StyleMolina-Guerrero, Carlos Eduardo, Idania Valdez-Vazquez, Arquímedes Cruz López, José de Jesús Ibarra-Sánchez, and Luis Carlos Barrientos Álvarez. 2025. "Techno-Economic Assessment of Hydrogen and CO2 Recovery from Broccoli Waste via Dark Fermentation and Biorefinery Modeling" Processes 13, no. 12: 4083. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124083

APA StyleMolina-Guerrero, C. E., Valdez-Vazquez, I., Cruz López, A., Ibarra-Sánchez, J. d. J., & Álvarez, L. C. B. (2025). Techno-Economic Assessment of Hydrogen and CO2 Recovery from Broccoli Waste via Dark Fermentation and Biorefinery Modeling. Processes, 13(12), 4083. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124083