Abstract

Asphalt pavements are significantly affected by high temperatures. Incorporating phase-change materials into asphalt can effectively absorb heat and reduce pavement temperatures. In this study, we prepared two PCMs—ethyl cellulose–polyethylene glycol (EC-PEG) and ethyl cellulose–myristic acid (EC-MA)—using ethyl cellulose (EC) as the shell material and polyethylene glycol 2000 (PEG) and myristic acid (MA) as the core materials via the counter-solvent method. The particle size, morphology, functional groups, and thermal properties of EC-PEG and EC-MA were characterized using a laser particle size analyzer, SEM, FTIR, and TG-DSC. By incorporating 5–30% EC-PEG and EC-MA into asphalt mixtures, mechanical properties were analyzed to determine the optimal phase-change particle content. Through temperature cycling tests on asphalt mixtures, the reduction in the cooling rate at the optimal dosage was determined. The test results have indicated the following: EC-MA exhibited a larger particle size than EC-PEG; EC-PEG forms loosely packed particles, while EC-MA adopted a blocky structure; EC-PEG and EC-MA formed a physical mixture without creating new chemical bonds; the PCMs phase-change enthalpies were 57.05 J/g and 89.15 J/g, respectively, with EC-MA exhibiting a higher encapsulation efficiency than EC-PEG. The optimal dosage of EC-PEG in asphalt mixtures was 15%, while that of EC-MA was 20%. At their respective optimal dosages, EC-MA demonstrated superior temperature control performance compared to EC-PEG, achieving a reduction in maximum temperature of 7.23 °C.

1. Introduction

Asphalt is a temperature-sensitive material [1], softening at high temperatures and exhibiting a decreased dynamic modulus [2]. Asphalt mixtures are viscoelastic materials; their high-temperature dynamic modulus decreases, making them prone to deformation [3,4]. During summer in Changsha, Hunan Province, asphalt pavement temperatures can exceed 70 °C. Asphalt pavements are susceptible to rutting under high temperatures [5,6]. Mu Yan et al. found that rutting on asphalt pavements at 70 °C is over ten times more severe than that at temperatures below 30 °C [7]. Temperature is considered a primary cause of asphalt pavement rutting [8]. Rutting damages pavements [9], not only increases the risk of traffic accidents [10] but also leads to high maintenance costs [11]. Thus, reducing high temperatures on asphalt pavements is essential. While there are multiple methods for lowering pavement temperatures [12], incorporating phase-change materials (PCMs), which absorb internal heat, into asphalt mixes [13] is one effective approach for reducing internal pavement temperatures [14,15]. Additionally, rapid temperature fluctuations within asphalt pavements are a significant cause of cracking [16,17]. PCMs regulate internal pavement temperatures, maintaining them within a stable range, thereby reducing pavement damage and conserving maintenance funds [18,19].

Numerous studies have investigated the incorporation of PCMs into asphalt mixtures. Huang et al. [20] investigated two PBMs, i.e., EPWP and EMAP, achieving maximum temperature reductions of 6.6 °C and 4.8 °C in asphalt mixtures, respectively. Deng et al. [21] added 3% PEG/SiO2 to asphalt mixtures, reducing the cumulative rutting depth by 4%. Betancourt et al. [22] employed phase-change microcapsules to regulate pavement temperature, achieving a 5–10 °C reduction in internal pavement temperatures. Anupam et al. [23] utilized OM35 and OM42 to lower asphalt pavement temperatures, achieving a maximum reduction in surface temperature of 4.12 °C. Gong et al. [24] designed a phase-change, thermal-induced structure that incorporated three composite phase-change materials, demonstrating their potential for pavement cooling and rutting resistance. Montoya et al. [25] investigated the rheological and thermal properties of asphalt mixtures containing phase-change materials. Athukorallage et al. [26] investigated the temperature regulation mechanism of phase-change materials, concluding that effective thermal conductivity plays a crucial role in asphalt pavement temperature distribution. Wei et al. [27] simulated phase-change asphalt pavements by using the finite element method, and found that different layers constructed with phase-change materials exhibit distinct thermal regulation capabilities. Dai et al. [28] developed a numerical model for pavements that incorporated 5–20% phase-change materials, demonstrating a significant reduction in the number of high-temperature days. Zhang et al. [29] utilized a composite phase-change material made from a binary eutectic of palmitic acid and stearic acid combined with waste steel slag in asphalt pavements, effectively reducing pavement temperature and mitigating the occurrence of high-temperature rutting.

Jia et al. [30] analyzed the bonding properties and rheological behavior of phase-change asphalt mixtures under laboratory aging conditions, using polyurethane as the solid-phase, phase-change material. Amini et al. [31] investigated the rutting resistance and fatigue performance of phase-change asphalt mixtures using MWCNT-modified phase-change materials. Bueno et al. [32] added tetradecane phase-change microcapsules to asphalt mixtures to evaluate their thermal performance. Kakar et al. [33] replaced 94–95 wt% of asphalt mixture aggregates with foam glass and lightweight ceramic aggregates impregnated with phase-change materials, achieving favorable cooling performance. Kataware et al. [34] discussed the application of organic or inorganic phase-change materials in asphalt pavements, comprehensively analyzing their impact on asphalt mixtures. Mizwar et al. [35] investigated the influence of phase-change materials on the rheological properties of asphalt mixtures.

Ethyl cellulose (EC) is a material characterized by excellent film-forming properties, low cost, good chemical and thermal stability, and high mechanical strength [36]. Several studies have explored the use of EC as a membrane material for preparing phase-change microcapsules [37]. Ma et al. [38] employed EC to encapsulate silica and activated carbon adsorbent phase-change materials, effectively addressing leakage issues associated with phase-change materials. Feczkó et al. [39] encapsulated hexadecane using EC, and the resulting phase-change microcapsules exhibited no significant changes in phase-change temperature or enthalpy over 1000 heating/cooling cycles. Wildy et al. [40,41] encapsulated a lauric acid/stearic acid mixture using EC to prepare phase-change drugs capable of regulating release rates in response to temperature changes. Gul et al. [42] prepared phase-change coatings using EC encapsulated coconut oil to regulate the temperature of cotton fabrics. Shuaib et al. [43] encapsulated polyethylene glycol with EC to create SS-CPCMs that exhibited prolonged luminescence in darkness. Can et al. [44] prepared phase-change materials for wood using EC encapsulating palmitic acid, enhancing the value of wood. Lin et al. [45] developed MPCMs with excellent thermal stability by encapsulating MA in EC. Noskov et al. [46] investigated the glass transition temperature and melting characteristics of phase-change materials prepared using EC and montmorillonite. Liu et al. [47] developed novel phase-change microcapsules using EC, carbon fiber, and stearic acid, exhibiting high latent heat and chemical stability. Amberkar et al. [48] prepared phase-change microcapsules by encapsulating beeswax with EC for temperature-controlled food packaging. Phadungphatthanakoon et al. [49] prepared a phase-change material by encapsulating undecane with EC and methylcellulose, which was blended with natural rubber to enhance its thermal and mechanical properties. Toth et al. [50] investigated the preparation process for phase-change materials by using a mixture of EC and alum. Xu [51] developed a temperature-responsive drug delivery system by combining EC and phase-change materials with rhodamine-loaded silk fibers. Huo et al. [52] developed organic/inorganic composite phase-change materials by encapsulating sodium sulfate dodecahydrate and disodium hydrogen phosphate dodecahydrate using an EC/acrylonitrile/butadiene/styrene copolymer.

As evidenced by the above literature, some research exists on the utilization of phase-change microcapsules for temperature regulation in asphalt pavements, and studies employing EC for encapsulating phase-change materials have also been reported. However, no studies have yet been published on the application of EC-PEG (EC encapsulated with PEG) or EC-MA (MA encapsulated with EC) to asphalt pavements. Incorporating EC-PEG and EC-MA into asphalt mixtures not only effectively enhances the mechanical properties of a mixture but also regulates its temperature, thereby improving the pavement’s resistance to rutting and delaying pavement deterioration.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials

The experiment used main experimental materials such as EC, PEG, OP-10, and anhydrous ethanol, all of which have AR grade purity. The specific parameters of the materials are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Materials and Main Technical Indicators.

2.2. PCM Preparation Process

The process indicated that 250 mL of anhydrous ethanol was measured by using a graduated cylinder and poured into a 500 mL beaker for later use. Then, the constant-temperature water bath was turned on, and the control temperature was set to 70 °C. Once the set temperature was reached, the beaker containing anhydrous ethanol was placed into the water bath for heating. After heating for 5 min, 1.5 g of OP-10 was poured into the beaker. The high-speed mixer was turned on and the speed was set to 600 rpm. 30 g of ethyl cellulose (EC) was weighed and slowly poured into the beaker. Once the ethyl cellulose was completely dissolved, the speed was set to 1200 rpm and continued stirring for 10 min. 4.5 g of ethyl phthalate was added to the beaker. Next, 60 g of MA or PEG was gradually added. Once the MA or PEG was completely dissolved, it was stirred for another 10 min. 100 mL of purified water was measured and slowly added dropwise using a pipette. After adding all the purified water, it was stirred for 30 min. The EC-MA/EC-PEG was separated from the purified water by using a vacuum filtration apparatus. The separated EC-MA/EC-PEG was washed three times with purified water. The separated EC-MA/EC-PEG was placed in a vacuum drying oven, maintained a constant temperature of 40 °C under vacuum, and the material was dried for 24 h before removal. The process indicated that the dried EC-MA/EC-PEG were ground by using a pulverizer to obtain EC-MA and EC-PEG.

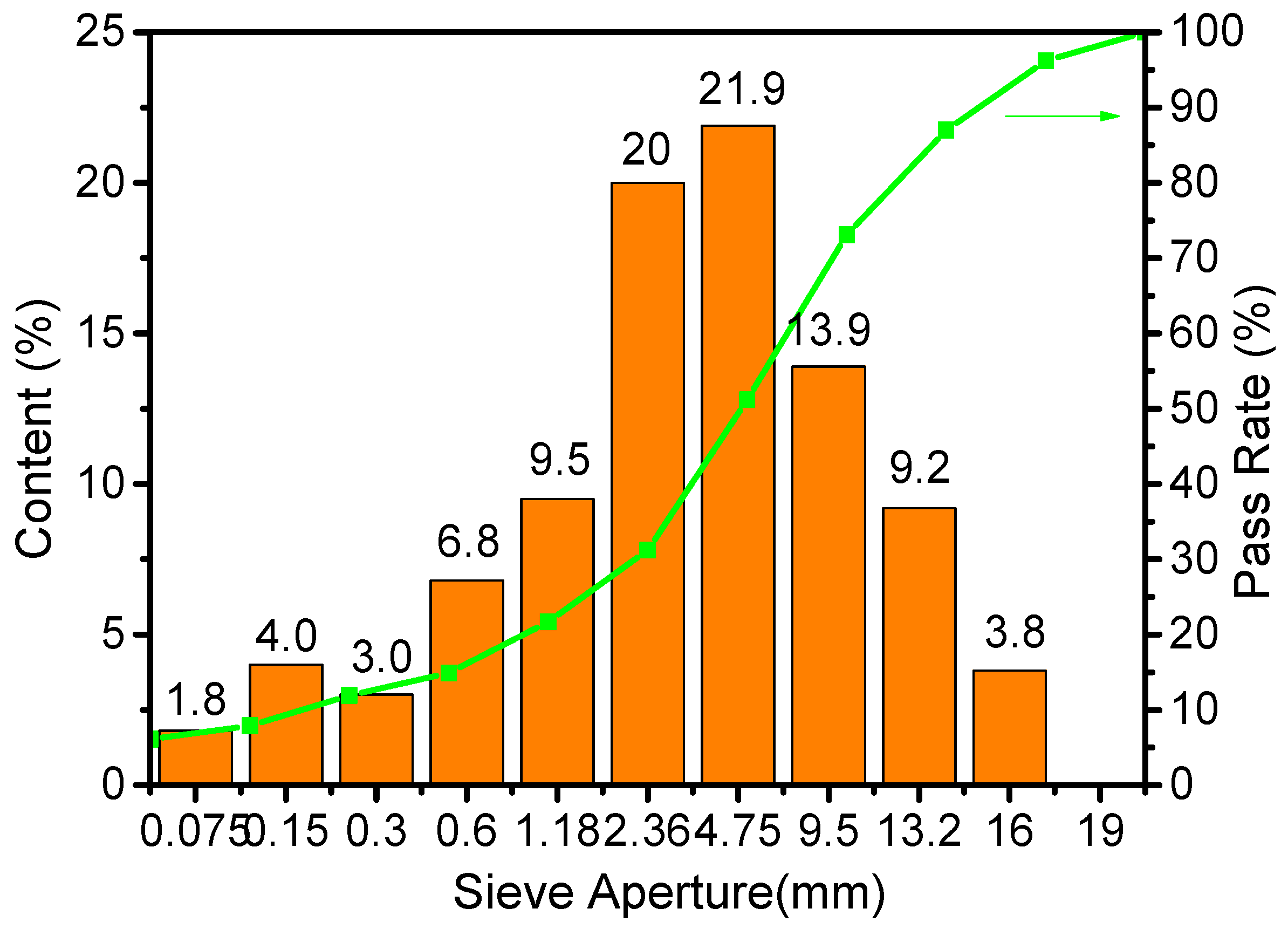

2.3. Asphalt and Aggregate Parameters

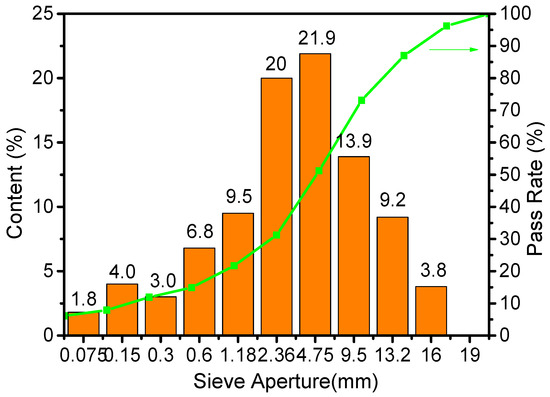

Donghai 70# asphalt was selected, and the following primary technical parameters were shown: Softening point: 53.2 °C; Ductility: 39.8 cm (50 mm/min, 10 °C); Penetration: 64.5 × 0.1 mm (25 °C, 5 s, 100 g); Density at 15 °C: 1.033 g/cm3; RTFOT residual mass change: 0.46%; Residual penetration at 25 °C: 70.2%. The aggregate selected was Jiangxi basalt, which was graded according to the classifications in Figure 1. The water absorption rate of the aggregate was 0.8%, and the crushing value was 8.5% (9.5–13.2 mm). The oil-to-aggregate ratio was set to 4.8%. The density of the asphalt mixture was 2.453 g/cm3.

Figure 1.

Aggregate grading curve.

2.4. Testing and Characterization

Particle size testing: Testing was conducted by using the Winner2000 particle analyzer (Winner, Jinan, China). Three random samples of crushed phase-change particles, each weighing 2 g, were tested. Prior to testing each sample, the channel was rinsed with purified water at least five times until the test background appeared clean. To initiate testing, we filled the sample cup two-thirds full with purified water. We then activated the instrument’s circulation button to establish water flow. We engaged ultrasonic agitation to uniformly disperse the sample. We then slowly poured the sample into the water within the sample cup. We launched the software to commence testing. The test sample’s refractive index was set to 1.5, with an absorption coefficient of 0.1. The final test result was determined by averaging the values from three trials, yielding the quantity of phase-change particles across each particle size range.

FTIR testing: Testing was conducted using Nicolet iS10 from Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. (Waltham, MA, USA). A small amount of phase-change material was mixed with KBr powder and ground in an agate mortar. The ground mixture was baked under an infrared lamp for 5–10 min, after which an appropriate amount was pressed into pellets. Pressure was applied at approximately 2 MPa to produce a complete, uniform, and translucent thin sheet. The pressed sample sheet was observed using Nicolet iS10. The scanning range was 4000–400 cm−1, with a scanning frequency of 16 times per sample.

SEM testing: Testing was conducted using ZEISS EVO10 from Sony Corporation of Japan (Minato ku, Tokyo, Japan). A small amount of phase-change particles was taken and adhered to a sample stage coated with conductive adhesive. The phase-change particles were then subjected to gold sputtering. Observations were performed under the protection of a nitrogen atmosphere. Both EC-MA and EC-PEG samples were examined.

TG-DSC testing: Testing was conducted using the STA449F3 instrument from Netzsch, Germany (Selb, Bavaria, Germany). After powering the instrument, it was preheated for 30 min. A sample weighing 5–10 mg was loaded. Nitrogen gas was used for protection. The heating rate was set to 10 °C/min, and the final temperature was set to 900 °C.

We blended EC-MA or EC-PEG into the asphalt, then mixed the asphalt mixture using asphalt containing phase-change particles. The phase-change particle content started at 5% of the asphalt content, increasing in 5% increments up to 30%. We calculated and weighed aggregates for each size fraction based on the specifications in Table 1. We heated the aggregates and phase-change asphalt, then prepared Marshall specimens using the compaction method specified in the “Standard Test Methods of Bitumen and Bituminous Mixtures for Highway Engineering” issued by the Ministry of Transport of China [53]. These Marshall specimens were also used for subsequent mechanical testing and thermal cycling tests.

Mechanical testing: Testing was conducted by using the Marshall Stability Tester acquired from Beijing Aerospace Keyu Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). The Marshall specimen and fixture were placed in water at 60 °C and heated at a constant temperature for 45 min. The Marshall specimen and fixture were then removed. The specimen was placed into the fixture, a displacement gauge was installed, and both the stability and flow values were reset to zero. The dynamic stability tester was activated to measure the dynamic stability and flow value of the specimen. The final result was determined as the average of the dynamic stability and flow values of eight Marshall specimens with identical phase-change material contents.

Temperature Cycling Test: Testing was conducted by using Victory Company’s 32-channel temperature measuring instrument. A groove approximately 3 mm wide and 5 mm deep was cut into the center of the lower surface of the Marshall specimen by using a cutting machine. The temperature probe was placed within the groove at the specimen’s center point. The groove was then filled with phase-change asphalt identical to that used for manufacturing the Marshall specimen, securing the temperature probe in place. A 15 mm wide paper strip was then applied over the groove to seal the phase-change asphalt, preventing it from flowing out of the groove at high temperatures. A second probe measuring the specimen’s surface temperature was placed at the center of the specimen’s upper surface. The temperature-measuring instrument recorded data at a frequency of 5 s per measurement. The light source was a 2500 W simulated sunlight source acquired from Suzhou Weishuo Optical Technology Co., Ltd. (Suzhou, Zhejiang, China), positioned at a height of 1 m, with an average irradiance of 1150 W/m2. The ambient test temperature was 17.5 °C. Two on-site tests were conducted, and the average temperature from both tests was taken as the final temperature.

3. Results and Discussion

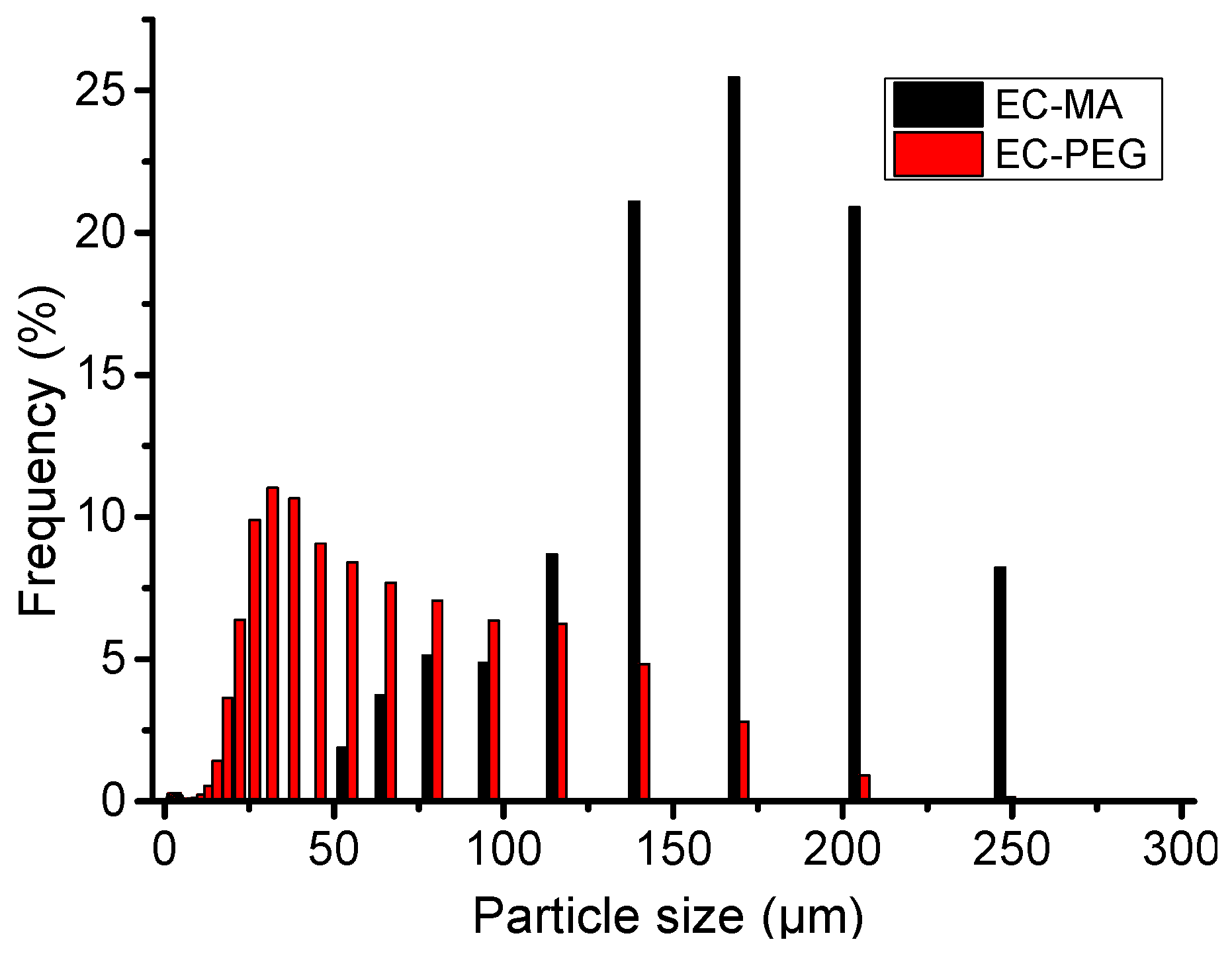

3.1. Particle Size Analysis

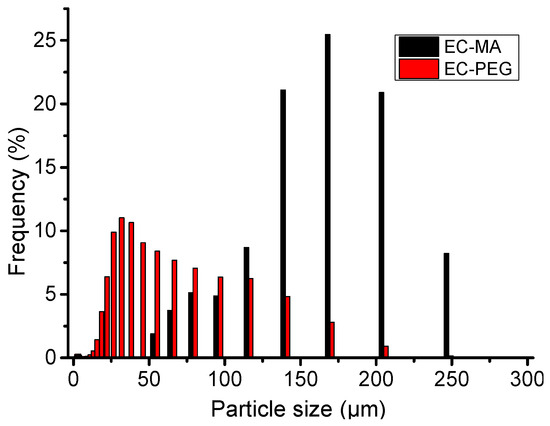

As shown in the diagram of the phase transformation particle size distribution depicted in Figure 2, EC-MA has the highest content in the range of 140 μm to 205 μm, accounting for approximately 67.44% of the total. The particle distribution follows a Poisson distribution, with a peak at 169 μm and a content of 25.45%. Particles with diameters less than 140 μm and greater than 205 μm have relatively low contents. EC-PEG particles are concentrated in a size range from 20.80 μm to 115.66 μm, with particles in this range accounting for 76.45% of the total. Particle sizes between 20.80 μm and 115.66 μm exhibit an irregular Poisson distribution, with the highest content at 30.46 μm, accounting for 11.02% of the total particle size. The content of particles between 25 μm and 115.66 μm decreases gradually, reaching a minimum of 6.25% at 115.66 μm. As shown, the average particle size of EC-MA is greater than that of EC-PEG.

Figure 2.

A diagram of the phase transition particle size distribution.

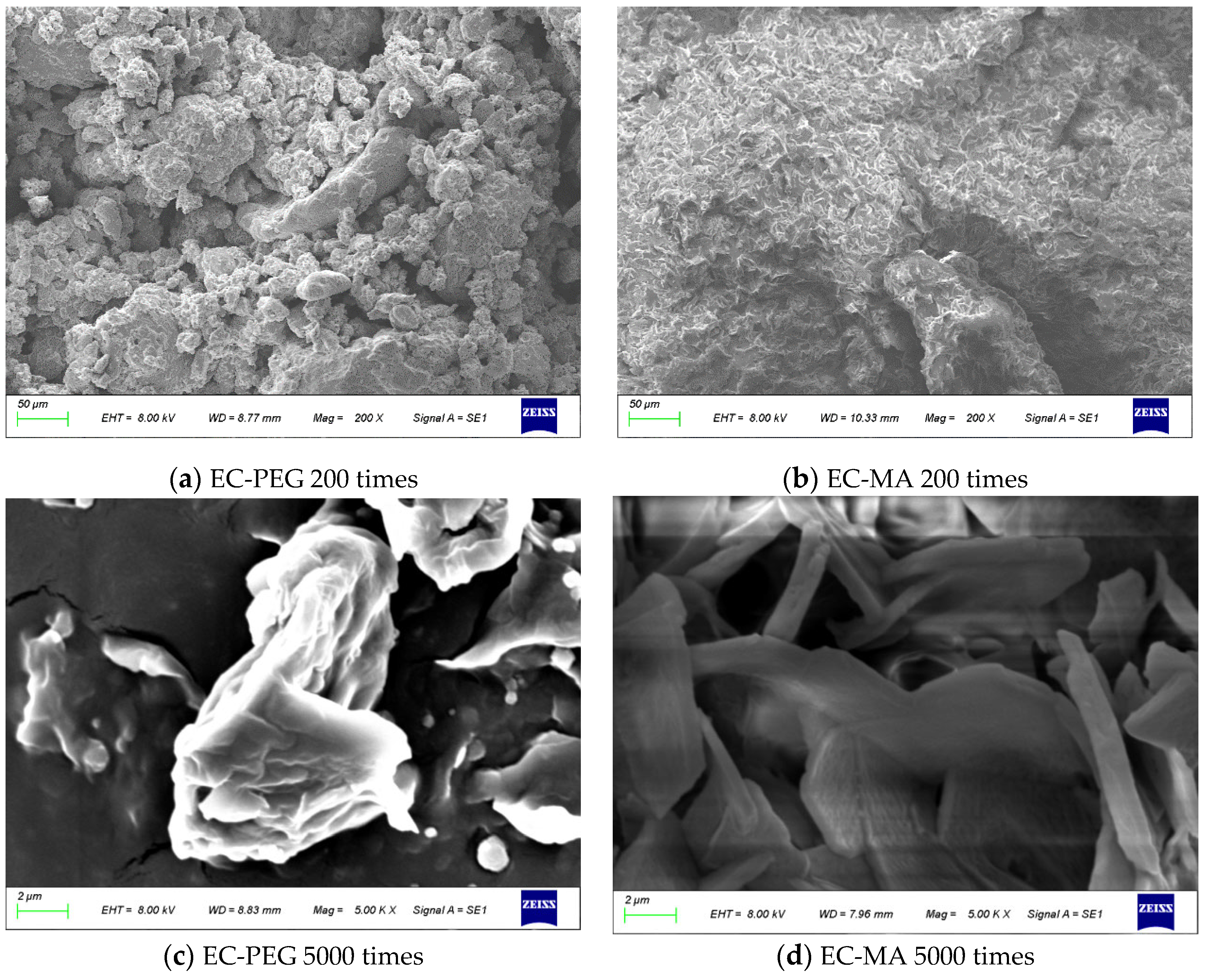

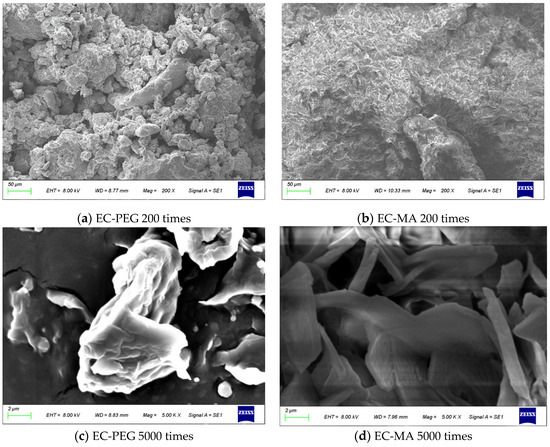

3.2. SEM Analysis

Two types of phase-change particles, EC-PEG and EC-MA, were observed. Figure 3 displays the morphological features of EC-PEG and EC-MA at magnifications of 200× and 5000×. As shown in Figure 3a, EC-PEG particles aggregated into clusters of varying sizes, with significant voids between these clusters forming a loosely packed structure. It could be seen that there are more particles around 25 μm in EC-PEG. Figure 3c shows EC-PEG at 5000× magnification; it can be observed that the surface particle shape is irregular. When crushed by a crusher, these small particles were not firmly bonded and easily detached from the larger particle group, forming small particle clusters. During grinding, these smaller particles readily detach from larger aggregates, forming smaller clusters. This has explained the higher proportion of small particles present in EC-PEG, directly corroborating the conclusions from Section 3.1.

Figure 3.

SEM images: (a) EC-PEG 200×, (b) EC-MA 200×, (c) EC-PEG 5000×, and (d) EC-MA 5000×.

Figure 3b,d displays the morphological features of EC-MA at 200× and 5000× magnification. Figure 3b has revealed that EC-MA particles have consolidated into compact masses with tightly bonded surfaces. Figure 3d has revealed numerous lamellar structures, a characteristic feature formed through the accumulation of MA lamellae on the particle surface. These interlocking lamellae enhanced interparticle bonding, resulting in a denser overall structure that resisted fragmentation. Compared to EC-PEG, EC-MA tended to maintain its original blocky structure during crushing, minimizing the generation of fine particles. This behavior aligned with its particle size distribution, which exhibited a higher proportion of large particles.

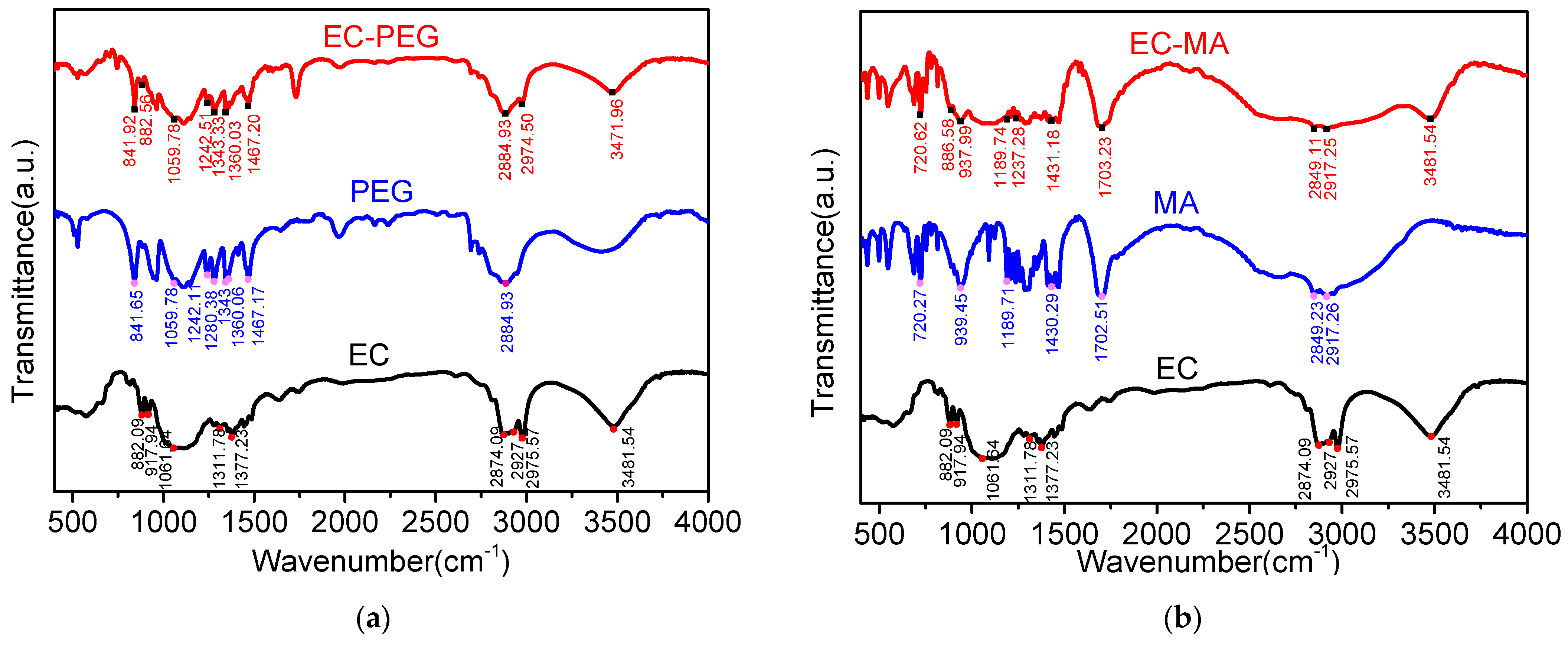

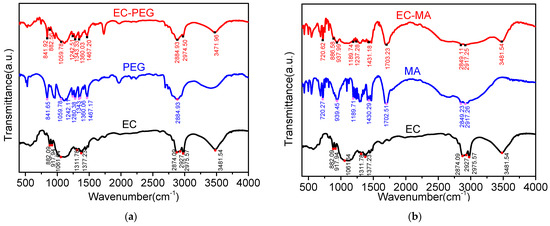

3.3. FTIR Analysis

The characteristic peaks of EC are shown in Figure 4. The peak at 3481.54 cm−1 corresponds to the -OH stretching vibration peak, while the peaks at 2975 cm−1 and 2874.09 cm−1 correspond to the asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibration peaks of the C-H bond in -CH3, respectively. The peak at 2927 cm−1 corresponds to the asymmetric stretching vibration peak of -CH2, 1377.23 cm−1 corresponds to the symmetric bending vibration peak of -CH3, 1311.78 cm−1 and 1061.64 cm−1 correspond to the symmetric stretching vibration peaks of C-O, and 917.94 cm−1 and 882.09 cm−1 correspond to the vibration peaks of -OC2H5.

Figure 4.

FTIR images: (a) EC, PEG, and EC-PEG spectra; (b) EC, MA, and EC-MA spectra.

The characteristic peaks of PEG are as follows: 2884.93 cm−1 corresponds to the symmetric stretching vibration peak of -CH2, 1467.17 cm−1 corresponds to the asymmetric stretching vibration bending peak of -CH3, 1360.06 cm−1 and 1280.38 cm−1 correspond to the peaks for the rocking vibration and out-of-plane rocking vibration of -CH2, 1059.78 cm−1 corresponds to the peak for the stretching vibration of -C-O, and 841.65 cm−1 corresponds to the peak for the in-plane rocking vibration of -CH2. The characteristic peaks of EC-PEG indicate that EC-PEG is a composite of the characteristic peaks of EC and PEG. EC-PEG possesses the characteristic peaks of both EC and PEG, indicating that this composite has not undergone a chemical reaction but merely represents physical fusion.

The characteristic peaks of MA are as follows: 2917.26 cm−1 corresponds to the antisymmetric stretching vibration peak of C-H in -CH3, 2849.23 cm−1 corresponds to the symmetric stretching vibration peak of C-H in -CH2, 1702.51 cm−1 corresponds to the stretching vibration peak of -C=O, 1430.29 cm−1 corresponds to the in-plane bending vibration peak of -CH, 1236.53 cm−1 corresponds to the C-C stretching vibration peak, 939.45 cm−1 corresponds to the out-of-plane bending vibration peak of -OH, and 720.27 cm−1 corresponds to the in-plane rocking vibration peak of -OH. Moreover, we have seen that the characteristic peak curve of EC-MA is almost identical to that of MA. The characteristic peak curve of EC-MA has combined the characteristics of both EC and MA. EC-MA is simply a physical blend of EC and MA materials, with no chemical reaction occurring.

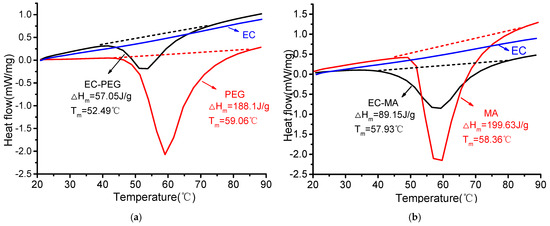

3.4. Thermogravimetric–Differential Thermal Analysis

- (1)

- DSC analysis

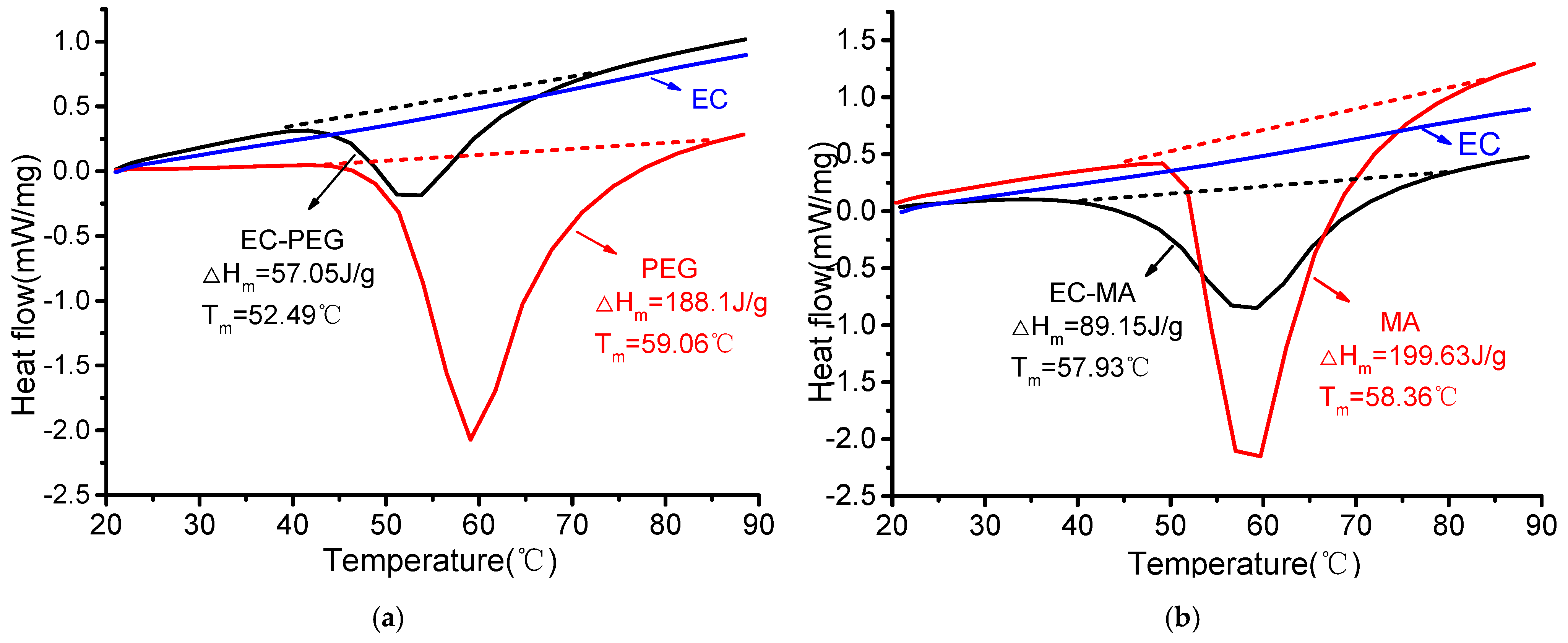

As shown in Figure 5a, the phase-change enthalpy of PEG is 188.1 J/g, while the phase-change peak temperature of EC-PEG is 52.49 °C, with a phase-change enthalpy of 57.05 J/g. As shown in Figure 5b, the phase-change enthalpy of MA is 199.63 J/g, while the phase-change peak temperature of EC-MA is 57.93 °C, with a phase-change enthalpy of 89.15 J/g. The phase-change enthalpy of EC-MA is significantly greater than that of EC-PEG. For the same mass of EC-PEG and EC-MA, EC-MA absorbs more heat than EC-PEG.

Figure 5.

DSC analysis images: (a) EC, PEG, and EC-PEG; (b) EC, MA, and EC-MA.

Encapsulation Rate Analysis: The encapsulation rate has served as a key indicator for evaluating PCM preparation, determined through the ratio of the mass of encapsulated core material to the initial mass of added core material. Specific calculation methods are detailed in Equations (1)–(4). Theoretical core material content is calculated using Equation (1):

In the above formula, is the theoretical core material content (%), is the enthalpy value of PCM J/g, and is the enthalpy value of MA or PEG (J/g).

The core material content of a successful encapsulation is calculated using Equation (2):

In the above formula, is the percentage of successfully encapsulated core material, while is the percentage of core material that has not been fully encapsulated.

The theoretical encapsulation rate and the actual encapsulation rate are calculated using Equations (3) and (4):

In the above formulae, is the theoretical encapsulation rate (%), is the actual encapsulation rate (%), is the mass of the prepared PCM (g), and is the mass of the core material input (g).

The theoretical and actual encapsulation rates of EC-MA and EC-PEG are finally calculated using Equations (1)–(4), as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Encapsulation rates.

As shown in Table 2, the actual encapsulation rate of EC-PEG is 36.33%, while that of EC-MA is 58.93%, indicating a significant difference between the two. Both the theoretical and actual encapsulation rates of EC-MA are considerably higher than those of EC-PEG. This is primarily because PEG is soluble in both water and ethanol, making it impossible to completely extract PEG from ethanol. Consequently, EC only binds with a portion of the PEG. MA, however, is insoluble in water and soluble only in ethanol. During the later stage of preparation, when water is added dropwise, the ethanol dissolves in water, causing MA to separate from the ethanol and be forced to bind with EC, thus becoming encapsulated by EC. Therefore, the encapsulation rate of MA is higher than that of PEG. On the other hand, EC-MA aggregates into plate-like structures, encapsulating MA within EC. In contrast, EC-PEG forms granular aggregates with a loose structure, where PEG is not fully encapsulated by EC. This also contributes to the lower encapsulation rate of EC-PEG.

- (2)

- TGA analysis

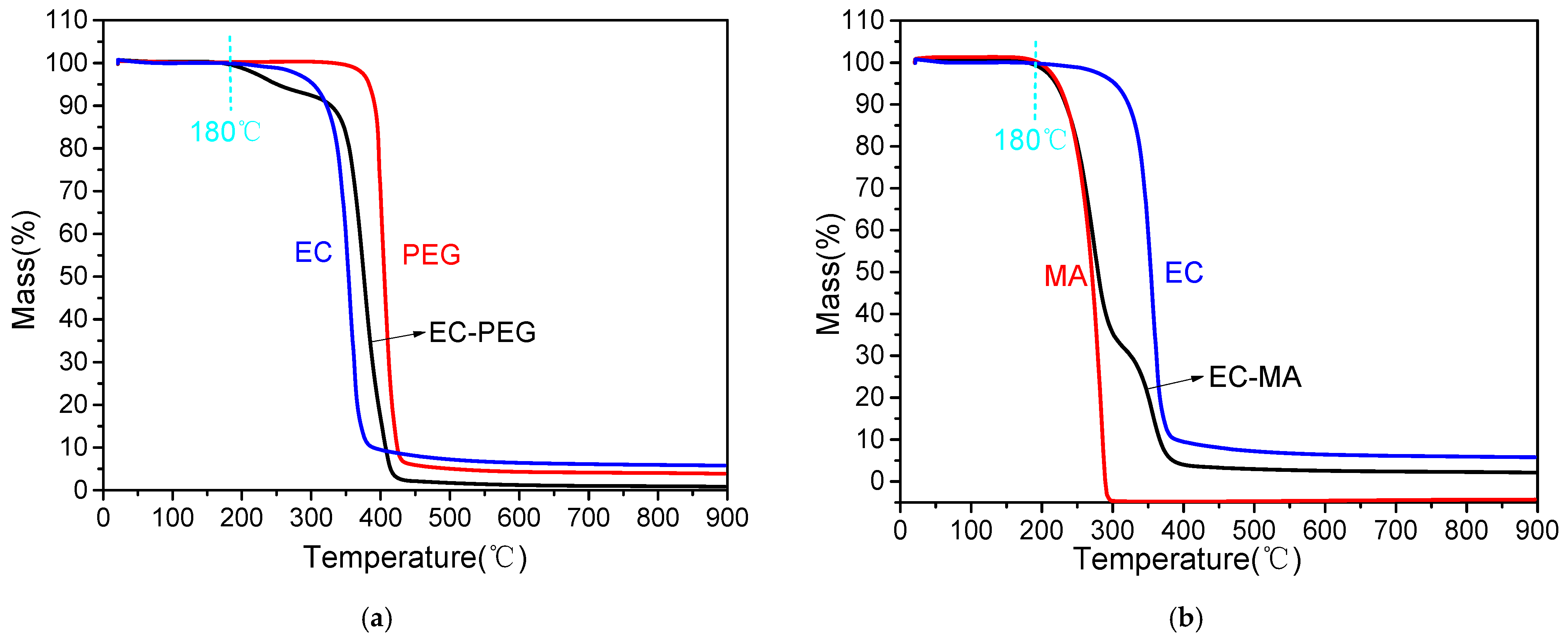

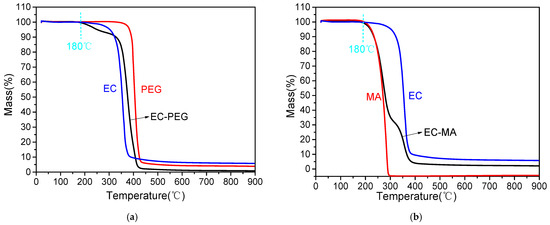

The higher the decomposition temperature of a material, the better its thermal stability. As shown in Figure 6a, EC begins to decompose at 165.35 °C, exhibits accelerated mass loss between 319 °C and 379 °C, and completes decomposition at 391.40 °C. PEG decomposes at 331.61 °C and completes decomposition at 481.4 °C. EC-PEG begins decomposition at 172 °C, exhibiting a small plateau between 200 °C and 324 °C. This plateau likely results from incomplete encapsulation or the decomposition of PEG outside the EC core. EC-PEG finally completes decomposition at 424 °C. As shown in Figure 6b, MA begins decomposition at 192.55 °C and completes it at 291 °C. EC-MA begins decomposition at 181.58 °C, exhibiting a gradual slope between 280 °C and 320 °C. This slope likely arises from the decomposition of leaked MA during EC decomposition. EC-MA ultimately completes decomposition at 398.64 °C.

Figure 6.

TGA images: (a) EC, PEG, and EC-PEG mass loss; (b) EC, MA, and EC-MA mass loss.

During asphalt mixture construction, materials such as asphalt, aggregates, and additives must be heated and mixed. The maximum heating temperature may reach 180 °C. Therefore, 180 °C is designated the critical temperature. Materials added to asphalt mixtures must withstand temperatures of 180 °C to remain stable. At 180 °C, EC exhibits a 0.07% mass loss, PEG and MA show no mass loss; EC-PEG experiences a 0.26% mass loss, and EC-MA suffers a 0.07% mass loss. Both EC-PEG and EC-MA demonstrate mass losses below 1%. This evidence indicates that at 180 °C, the thermal stability of all PCM components is satisfactory, meeting the high-temperature demands of asphalt mixture construction. Table 3 lists the temperatures at which each material experiences 0%, 5%, and 10% mass loss. The temperatures for 5% mass loss in EC-PEG and EC-MA are 252.45 °C and 221.54 °C, respectively, with both exceeding the maximum heating temperature of asphalt mixtures. The temperatures at which EC-PEG and EC-MA lose 10% mass are 329.30 °C and 236.33 °C, respectively, which are significantly higher than the maximum heating temperature of asphalt mixtures. Therefore, when PCMs are incorporated into asphalt mixtures, they can withstand the high temperatures encountered during construction, enabling PCMs to effectively perform their intended functions.

Table 3.

TGA mass losses.

3.5. Mechanical Testing of Asphalt Mixtures

Table 4 shows that maximum dynamic stability was achieved in specimens with 5% EC-PEG content, reaching 17.48 kN. The Marshall modulus peaked at 7.39 kN/mm when EC-PEG content was 15%. As the EC-PEG content varied from 5% to 30%, the Marshall modulus exhibited a slight decrease–increase–decrease trend. The Marshall moduli of specimens with 5% and 10% EC-PEG content were slightly higher than those of standard Marshall specimens. The Marshall modulus reached its maximum value at an EC-PEG content of 15%. It began to decrease at an EC-PEG content between 20% and 25%, with a significant decrease observed at 30%. This phenomenon can be explained by the fact that EC, in EC-PEG, acts as a binder, while PEG functions as a lubricant. At low EC-PEG dosages (below 10%), both the binding effect of EC and the lubricating effect of PEG are relatively weak. The binding effect of EC is only slightly greater than the lubricating effect of PEG, resulting in only a slight increase in the Marshall modulus value. When the EC-PEG dosage reaches 15%, the binding effect of EC becomes dominant, with the best mechanical properties of the asphalt mixture achieved at this point. When the content exceeds 15%, the lubricating effect of PEG becomes dominant, weakening the mechanical properties of the asphalt mixture. Therefore, the optimal EC-PEG content is 15%.

Table 4.

Test results for asphalt mixtures at various mixing ratios.

For EC-MA, the Marshall modulus steadily increases, followed by a decrease, as the content ranges from 5% to 30%. The maximum value is achieved at an EC-MA content of 20%. At EC-MA contents between 5% and 10%, the Marshall modulus is slightly higher than that of standard Marshall mixes. At EC-MA contents between 15% and 20%, the Marshall modulus increases significantly, peaking at 20%. At EC-MA dosages of 25–30%, the Marshall modulus decreases significantly. This phenomenon can be explained as follows: At low EC-MA dosages (below 10%), the bonding effect of EC and the lubricating effect of MA are both relatively weak, exerting minimal mechanical influence on the asphalt mixture. At EC-MA dosages of 15–20%, the binding effect of EC dominates, improving the mechanical properties of the asphalt mixture. When the EC-MA dosage exceeds 20%, the lubricating effect of MA becomes dominant, decreasing the mechanical properties of the asphalt mixture. Therefore, the optimal dosage of EC-MA is 20%.

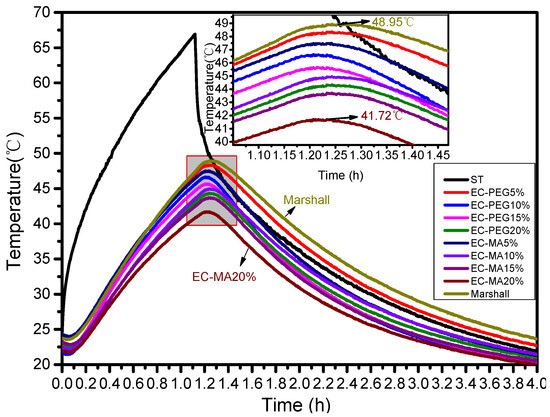

3.6. Temperature Adjustment Analysis of Asphalt Mixture

The greater the PCM content, the better the cooling effect; similarly, the higher the phase-change enthalpy of the PCM, the more effective the cooling effect. While there is a desire to incorporate more PCM into the asphalt mixture, excessive PCM content can adversely affect the mixture’s mechanical properties. The asphalt mixture with the optimal PCM content, determined through mechanical property testing, became the focal point of this experiment. Additionally, Marshall specimens with PCM contents ranging from 5% to 20% were selected as controls for concurrent testing. The test site is illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

On-site photograph depicting asphalt mixture specimen temperature testing.

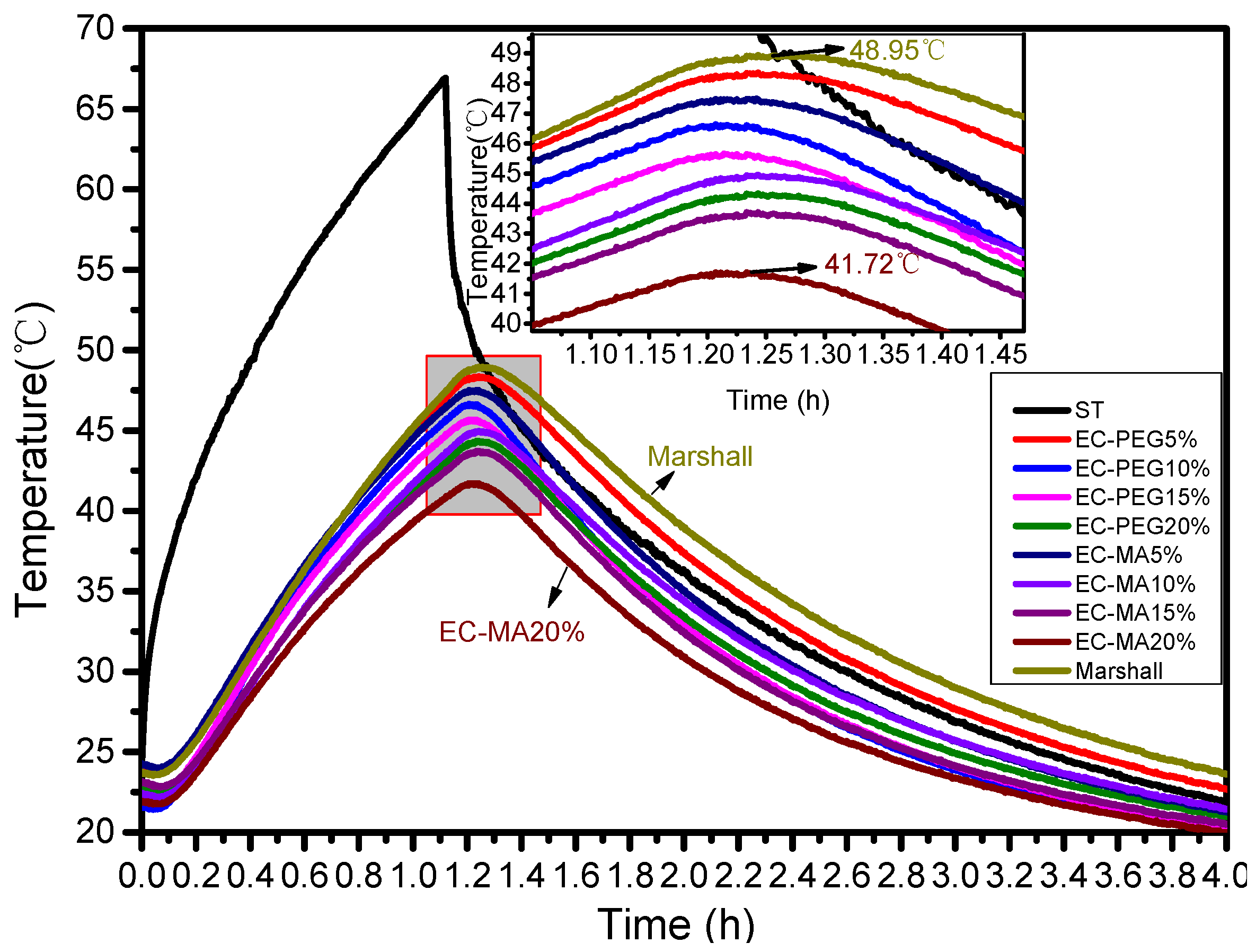

To ensure comparable light exposure intensity, Marshall specimens with identical PCM contents were positioned under similar light conditions. The heating phase lasted 1 h, and the cooling phase lasted 3 h. Heating involved using artificial light to raise specimen temperatures via radiant heat, while cooling occurred naturally after the lights had been turned off. Measured temperatures were plotted, as shown in Figure 8. The figure indicates that the upper surface (ST line) of the specimens heated up most rapidly, while the lower surface heated more slowly. After 1 h of illumination, the upper surface reached its peak temperature of 66.93 °C, with the lower surface reaching its peak approximately 7 min later. All specimens reached their maximum temperatures nearly simultaneously.

Figure 8.

A diagram of the temperature testing curve.

The standard Marshall specimen heated up the fastest and reached the highest temperature, peaking at 48.95 °C. Specimens with EC-PEG dosages of 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20% reached maximum temperatures of 48.34 °C, 46.65 °C, 45.63 °C, and 44.33 °C, respectively, representing temperature reductions of 0.61 °C to 4.62 °C compared to the standard Marshall specimen. Specimens with EC-MA contents of 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20% reached maximum temperatures of 47.5 °C, 44.96 °C, 43.68 °C, and 41.72 °C, respectively, with a cooling range of 1.45 °C to 7.23 °C compared to standard Marshall specimens. At the optimal EC-PEG content, the maximum phase transition temperature difference relative to the standard Marshall specimens was 3.32 °C. At the optimal EC-MA content, the maximum phase transition temperature difference compared to the standard Marshall specimens was 7.23 °C. EC-MA demonstrated superior temperature control performance compared to EC-PEG.

4. Conclusions

In this paper, two phase change materials—EC-PEG and EC-MA—were designed to mitigate the effects of high temperatures on asphalt mixtures. By incorporating EC-PEG and EC-MA into asphalt mixtures at specific dosages, the temperature of the mixtures was reduced through the heat absorption properties of these materials. The prepared EC-PEG and EC-MA were characterized using laser particle size analyzers, SEM, FTIR, and TG-DSC. Laser particle size analysis revealed that EC-PEG predominantly exhibited particles around 25 μm, while EC-MA particles were concentrated between 140 μm and 205 μm. SEM analysis showed EC-PEG contained numerous pores with granular agglomerates, whereas EC-MA exhibited a blocky structure. FTIR analysis confirmed that the fusion between EC and PEG/MA was physical in nature. TG-DSC measurements revealed a phase transition enthalpy of 57.05 J/g for EC-PEG and 89.15 J/g for EC-MA. The actual encapsulation rate was 36.33% for EC-PEG and 58.93% for EC-MA. Mechanical property tests on asphalt mixtures revealed the optimal dosage of EC-PEG to be 15% and EC-MA to be 20%. At these optimal dosages, EC-PEG achieved a maximum temperature reduction of 3.32 °C, while EC-MA achieved 7.23 °C, demonstrating superior temperature control performance compared to EC-PEG.EC-MA is the preferred choice for use in asphalt mixtures.

Limitations of Present Research

It should be noted that this study has certain limitations. First, the actual encapsulation efficiency levels of EC-PEG and EC-MA are not high. Second, whether chemical reactions occurred was not further verified via XRD. Third, the light source used in the heating and cooling tests performed on Marshall specimens achieved only 90% uniformity within the experimental range, resulting in higher temperatures in the central area and lower temperatures around it, indicating a need for further improvement in light uniformity. Despite these limitations, they do not hinder the conclusions drawn in this study. EC-MA demonstrates excellent cooling effects in asphalt mixtures. By conducting further research to enhance phase-change enthalpy and encapsulation efficiency, even better cooling performance could be achieved in asphalt mixtures.

Author Contributions

Z.H.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—original draft and editing. Q.F. and Y.Z.: Writing—review and Editing. J.W.: Resources. X.Z.: Data curation, Methodology. Z.F.: Validation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Key Project of the Education Department of Hunan Province (NO. 24A0246), and the Open Fund of the Hunan Engineering Research Center for Intelligent Construction of Fabricated Retaining Structures.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EC | Ethyl cellulose |

| MA | Myristic acid |

| PEG | Polyethylene glycol 2000 |

| EC-MA | Ethyl cellulose-myristic acid |

| EC-PEG | Ethyl cellulose-polyethylene glycol |

References

- Su, A.; Yin, H. Grey correlation analysis of asphalt-aggregate adhesion with high and low-temperature performance of asphalt mixtures. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e03765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Xiao, J.; Ding, J.; Li, Y.; Zhao, X.; Jiang, W. Damage characterization of high- and low-temperature performance of porous asphalt mixtures under multi-field coupling. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e03455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Zhang, H.; Yu, T.; Sun, J.; Shan, Z.; He, D. Meso-structural characteristics of porous asphalt mixture based on temperature-stress coupling and its influence on aggregate damage. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 342, 128064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Sun, L.; Li, J.; Liu, L. Effect of key design parameters on high temperature performance of asphalt mixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 348, 128651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuhong, W.; Zhichao, W. Prediction model for rutting of asphalt concrete pavement considering temperature influence. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, e04831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Ruan, P.; Lu, Z.; Liang, L.; Han, B.; Hong, B. Effects of the high temperature and heavy load on the rutting resistance of cold-mix emulsified asphalt mixture. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 298, 123831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Y.; Fu, Z.; Liu, J.; Li, C.; Dong, W.H.; Dai, J.S. Evaluation of High-Temperature Performance of Asphalt Mixtures Based on Climatic Conditions. Coatings 2020, 10, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Flintsch, G.W.; Dawson, A.R.; Parry, T. Examining effects of climatic factors on flexible pavement performance and service life. Transp. Res. Rec. 2013, 2349, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Tan, Y.; Gao, Y.; Fu, Y.; Li, J.; Li, S.; Zhou, X. Resilience assessment of asphalt pavement rutting under climate change. Transp. Res. Part D-Transp. Environ. 2022, 109, 103395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, B.; Cao, J.; Huang, W.; Ma, T.; Shi, Z. Rutting prediction model of asphalt pavement based on RIOHTrack full-scale ring road. Measurement 2025, 242, 115915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzarowski, L. The Development of Asphalt Mix Creep Parameters and Finite Element Modeling of Asphalt Rutting. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON, Canada, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Xu, T. Developments and thermal properties of thermochromic microcapsule and thermochromic asphalt-based composite coatings. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 438, 137184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, G.; Gao, A.; Niu, Q.; Xie, S.; Xu, B.; Pan, B. Study on the Performance of Phase-Change Self-Regulating Permeable Asphalt Pavement. Buildings 2023, 13, 2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Ma, F.; Fu, Z.; Sangiorgi, C.; Tataranni, P.; Tarsi, G.; Li, C.; Hou, Y.; Guo, Y. Binary eutectic phase change materials application in cooling asphalt: An assessment for thermal stability and durability. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 700, 134790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Qi, C.; Han, S.; Fan, L.; Huan, X.; Chen, H.; Kuang, D. Thermal storage kinetics of phase-change modified asphalt: The role of shell design and asphalt influence. Energy 2025, 322, 135660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Wu, H.; Song, W.; Yin, J.; Zhan, Y.; Yu, J.; Abubakar Wada, S. Thermal fatigue and cracking behaviors of asphalt mixtures under different temperature variations. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 369, 130623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Li, Q.; Song, W.; Chen, X.; Wada, S.A.; Liao, H. Meso-mechanical characterization on thermal damage and low-temperature cracking of asphalt mixtures. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2025, 316, 110862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Qu, H.; Huang, W.; Cheng, Z.; Liu, S.; Li, B. Evaluation of phase change thermoregulated asphalt on low temperature cracking performance of asphalt pavements. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, e04612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamedi, G.H.; Asadi, A.H.; Zarrinfam, J. Investigating the effect of fundamental properties of materials on the mechanisms of thermal cracking of asphalt mixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 411, 134426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Wei, J.; Fu, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Lei, M.; Pan, Z.; Zhang, X. Preparation and Experimental Study of Phase Change Materials for Asphalt Pavement. Materials 2023, 16, 6002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Shi, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J. Numerical modelling of rutting performance of asphalt concrete pavement containing phase change material. Eng. Comput. 2023, 39, 1167–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betancourt-Jimenez, D.; Montoya, M.; Haddock, J.; Youngblood, J.P.; Martinez, C.J. Regulating asphalt pavement temperature using microencapsulated phase change materials (PCMs). Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 350, 128924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anupam, B.R.; Sahoo, U.C.; Rath, P.; Pattnaik, S. Thermal Behavior of Phase Change Materials in Concrete Pavements: A Long-term Thermal Impact Analysis of Two Organic Mixtures. Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol. 2024, 17, 366–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Liu, W.; Ying, H. Phase Change Heat-induced Structure of Asphalt Pavement for Reducing the Pavement Temperature. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Civ. Eng. 2022, 46, 1655–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya, M.A.; Betancourt, D.; Rahbar-Rastegar, R.; Youngblood, J.; Martinez, C.; Haddock, J.E. Environmentally Tuning Asphalt Pavements Using Microencapsulated Phase Change Materials. Transp. Res. Rec. 2022, 2676, 158–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athukorallage, B.; Dissanayaka, T.; Senadheera, S.; James, D. Performance analysis of incorporating phase change materials in asphalt concrete pavements. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 164, 419–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, W.; Ma, B.; Ren, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Tian, Y.; Li, Y. Temperature responses of asphalt pavement structure constructed with phase change material by applying finite element method. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 244, 118088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, M.; Wang, S.; Deng, J.; Gao, Z.; Liu, Z. Study on the Cooling Effect of Asphalt Pavement Blended with Composite Phase Change Materials. Materials 2022, 15, 3208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Sani, B.M.; Xu, P.; Liu, K.; Gu, F. Preparation and characterization of binary eutectic phase change material laden with thermal conductivity enhancer for cooling steel slag asphalt pavement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 388, 131688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, M.; Sha, A.; Jiang, W.; Wang, W.; Yuan, D. Adhesion, rheology and temperature-adjusting performance of polyurethane-based solid–solid phase change asphalt mastics subjected to laboratory aging. Mater. Struct. 2023, 56, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, N.; Hayati, P.; Latifi, H. Evaluation of Rutting and Fatigue Behavior of Modified Asphalt Binders with Nanocomposite Phase Change Materials. Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol. 2023, 16, 678–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, M.; Kakar, M.R.; Refaa, Z.; Worlitschek, J.; Stamatiou, A.; Partl, M.N. Modification of asphalt mixtures for cold regions using microencapsulated phase change materials. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 20342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakar, M.R.; Refaa, Z.; Worlitschek, J.; Stamatiou, A.; Partl, M.N.; Bueno, M. Impregnation of Lightweight Aggregate Particles with Phase Change Material for Its Use in Asphalt Mixtures. In Proceedings of the 5th International Symposium on Asphalt Pavements & Environment (APE); Pasetto, M., Partl, M.N., Tebaldi, G., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 337–345. [Google Scholar]

- Kataware, A.V.; Shantharam, A. Review on Influence of Organic and Inorganic Phase Change Materials on Performance of Asphalt Binder and Asphalt Mix. Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizwar, I.K.; Napiah, M.; Sutanto, M.H. Effect of Phase Change Material on Rheological Properties of Asphalt Mastic. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Civil, Offshore and Environmental Engineering (ICCOEE2020); Mohammed, B.S., Shafiq, N., Kutty, S.R.M., Mohamad, H., Balogun, A.-L., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 836–843. [Google Scholar]

- Engleng, B.; Kalita, E. Cellulose-Based Nanocomposites for Tissue Engineering. In Novel Bio-Nanocomposites for Biomedical Applications; Sharma, K., Tiwari, S.K., Kumar, V., Kalia, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 261–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Wang, X.-q.; Zhou, X.-y.; Wei, K.; Huang, W. Measurement and analysis of thermophysical parameters of the epoxy resin composites shape-stabilized phase change material. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 223, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Ma, J.; Wang, D.L.; Peng, S.G. Preparation and Properties of Composite Shape-Stabilized Phase Change Material for Asphalt Mixture. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2011, 71, 118–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feczkó, T.; Kardos, A.F.; Németh, B.; Trif, L.; Gyenis, J. Microencapsulation of n-hexadecane phase change material by ethyl cellulose polymer. Polym. Bull. 2014, 71, 3289–3304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildy, M.; Hao, Q.; Wei, W.; Nguyen, D.H.; Xu, K.; Schossig, J.; Hu, X.; Salas-de la Cruz, D.; Hyun, D.C.; Wang, Z.; et al. Tunable chemotherapy release using biocompatible fatty acid-modified ethyl cellulose nanofibers. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2025, 9, 100670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildy, M.; Wei, W.; Xu, K.; Schossig, J.; Hu, X.; Salas-de la Cruz, D.; Hyun, D.C.; Lu, P. Exploring temperature-responsive drug delivery with biocompatible fatty acids as phase change materials in ethyl cellulose nanofibers. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 266, 131187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, Z.; Iqbal, K. Encapsulation of Coconut Oil Using Ethyl Cellulose as Coating Shell for Thermoregulating Response of Cotton. J. Nat. Fibers 2022, 19, 14422–14434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuaib, S.S.A.; Niu, Z.; Qian, Z.; Qi, S.; Yuan, W. Self-luminous, shape-stabilized porous ethyl cellulose phase-change materials for thermal and light energy storage. Cellulose 2023, 30, 1841–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Can, A. Preparation, characterization, and thermal properties of microencapsulated palmitic acid with ethyl cellulose shell as phase change material impregnated wood. J. Energy Storage 2023, 66, 107382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Zhu, C.; Alva, G.; Fang, G. Microencapsulation and thermal properties of myristic acid with ethyl cellulose shell for thermal energy storage. Appl. Energy 2018, 231, 494–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noskov, A.V.; Alekseeva, O.V.; Guseinov, S.S. A Differential Scanning Calorimetry Study of Phase Transitions in Ethyl cellulose/Bentonite Polymer Composites. Prot. Met. Phys. Chem. Surf. 2023, 59, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, N.; Ding, Y. Preparation and properties of composite phase change material based on solar heat storage system. J. Energy Storage 2021, 40, 102805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amberkar, T.; Mahanwar, P. Microencapsulation study of bioderived phase change material beeswax with ethyl cellulose shell for thermal energy storage applications. Energy Sources Part A-Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2023, 45, 11803–11818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phadungphatthanakoon, S.; Poompradub, S.; Wanichwecharungruang, S.P. Increasing the thermal storage capacity of a phase change material by encapsulation: Preparation and application in natural rubber. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2011, 3, 3691–3696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tóth, J.; Németh, B.; Gyenis, J. Formation of Microcapsulated Aluminium Potassium Sulfate Dodecahydrate by Phase Separation Method. Period. Polytech.-Chem. Eng. 2015, 59, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K. Silk Fibroin Nanofiber Design via Electrospinning for Temperature-Responsive and Ethanol-Sensitive Drug Delivery Systems. Master’s Thesis, Rowan University, Glassboro, NJ, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Huo, X.L.; Xie, D.H.; Zhao, Z.M.; Wang, S.J.; Meng, F.B. Novel method for microencapsulation of eutectic hydrated salt as a phase change material for thermal energy storage. Int. J. Low-Carbon Technol. 2022, 17, 760–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Transport of the People’s Republic of China. Test Methods of Bitumen and Bituminous Mixtures for Highway ENGINEERING (JTG 3410-2025); China Communications Press: Beijing, China, 2025.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).