Abstract

In the present study, the endophytic fungus Fusarium fujikuroi was isolated from the medicinal plant Debregeasia salicifolia and cultivated for the extraction of bioactive metabolites. The crude extract was fractionated via gravity column chromatography using solvents of increasing polarity (n-hexane, n-hexane/chloroform 1:1 v/v, chloroform, ethyl acetate, and methanol) to isolate bioactive compounds. The antimicrobial activity of these fractions was evaluated against pathogenic bacteria (Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Escherichia coli). Most extracts exhibited significant antimicrobial activity, with the n-hexane/chloroform fraction (HCF) showing the highest efficacy (18 mm inhibition zone), followed by the n-hexane fraction while Ciprofloxacin was used as a positive control. Fractions were tested in triplicate; antibacterial activities (p < 0.05) were highest in the HCF. Bioactive compounds from the most potent fractions were further purified and analyzed using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS). The GC-MS profiling revealed the presence of diverse bioactive metabolites, including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), phenols, and fatty acids. Notably, several of these compounds have not been previously reported in Fusarium fujikuroi, highlighting the potential for novel antimicrobial agents from this endophytic strain. In silico toxicity prediction using the ProTox-II tool indicated that the major compounds possess low to moderate toxicity profiles, supporting their potential safety for further biological evaluation.

1. Introduction

The emergence of antibiotic resistance in pathogenic bacteria such as Staphylococcus, Mycobacterium, and Streptococcus, alongside the ongoing risk of naturally resistant strains, has heightened the demand for alternative approaches to tackle bacterial infections [1]. Consequently, there is an increasing need for innovative agrochemicals, chemotherapeutic drugs, and antibiotics that are very effective, low in toxicity, and sustainable for the environment [2]. Bioactive metabolites from natural products originating in plants, animals, and microorganisms have been essential therapeutic agents for medicines for thousands of years. The World Health Organization (WHO) states that more than 80% of the world’s population depends on traditional medicine for primary health care, highlighting their lasting significance [3,4]. In Asia, the application of herbal treatments is deeply embedded in traditional practices, showcasing a long-standing connection between people and their natural surroundings [5]. Plants and fungi generate a wide variety of bioactive substances that have proven effectiveness against viral infections and long-term illnesses. Nevertheless, the growing occurrence of drug resistance and negative reactions linked to synthetic medications has sparked renewed interest in ethnopharmacognosy as a potential alternative [6]. Significantly, numerous phytochemicals from plants provide safer, wide-ranging therapeutic possibilities with reduced side effects. These natural metabolites demonstrate various biological effects, such as antibacterial, anticancer, antioxidant, antidiarrheal, analgesic, and wound-healing activities [7,8]. In recent years, endophytic fungi have garnered significant attention due to their ability to synthesize diverse bioactive secondary metabolites with substantial pharmaceutical potential [9,10,11]. Compared to traditional medicinal plants which often face challenges of low yield and limited availability, endophytes represent a cost-effective and sustainable source of bioactive compounds. Moreover, these fungi produce secondary metabolites such as lytic enzymes and antibiotics, which exhibit broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity against various pathogens [12,13]. Fungal endophytes synthesize a wide array of bioactive compounds, including steroids, alkaloids, isocoumarins, terpenoids, phenylpropanoids, quinones, lactones, phenols, and phenolic acids, many of which demonstrate significant biological activities [14,15].

Fusarium fujikuroi, a member of the Fusarium fujikuroi species complex (phylum Ascomycota, kingdom Fungi), is an endophytic fungus residing within the medicinal plant Debregeasia salicifolia [16]. This species is prevalent in regions such as Pakistan, India, Afghanistan, and tropical Africa, where it has been traditionally used to treat various ailments, including cancer, skin disorders, and urinary tract infections [17]. Although local communities have long relied on crude preparations of medicinal plants and fungi, systematic phytochemical screening is essential to identify and isolate their bioactive constituents [18]. Purification of these compounds is critical, as purified metabolites often exhibit superior biological activity compared to crude extracts. Furthermore, crude extracts may contain toxic compounds that can be eliminated through fractionation, ensuring safer therapeutic applications [19]. Several studies have comprehensively characterized the secondary metabolite repertoire of F. fujikuroi, underscoring its biosynthetic richness and the potential for discovery of new antimicrobial agents [20,21,22].

Although Fusarium fujikuroi has been extensively studied for its role as a plant pathogen and producer of gibberellins, its capacity as an endophytic source of antibacterial metabolites remains largely unexplored. Moreover, few studies have provided a detailed GC–MS-based chemical profile of F. fujikuroi associated with medicinal plants. The present study addresses this gap by systematically fractionating the ethyl acetate extract of an endophytic F. fujikuroi strain from Debregeasia salicifolia, evaluating the antibacterial activity of each solvent fraction, and linking bioactivity to distinct chemical constituents detected by GC–MS. The identification of several metabolites such as 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol, hentriacontane, and long-chain fatty-acid esters not previously reported from this species highlights its previously unrecognized biosynthetic potential. To complement the bioactivity assessment, in silico toxicity prediction of the main identified compounds was performed using the ProTox-II platform to provide preliminary insights into their safety profiles.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Chemicals and Apparatus

The materials and equipment used in this study were sourced from commercial suppliers. Chromatographic separations were performed using silica gel (60–120 mesh; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and monitored on TLC Silica gel 60 F254 plates (Merck, Darmstadt Germany). Microbiological media, including Potato Dextrose Agar (Oxoid, Hampshire, U K) and Lactophenol Cotton Blue stain (Oxoid, Hampshire, UK), were used for fungal cultivation and identification. The antibacterial assays were conducted on Mueller-Hinton agar purchased from Guangdong Huankai Microbial Technology Co., Ltd. (Guangzhou, China). For instrumental analysis, gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) was carried out on a Clarus 600C system (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) and the resulting spectra were processed using TurboMass Software (version 6) and compared against the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) mass spectral database. The toxicity of major compounds was predicted in silico using the ProTox-II web tool (https://tox-new.charite.de/protox_II/, 10 November 2025). Statistical analysis was performed using Origin-pro software (version 9). All other solvents and chemicals, including the positive control antibiotic Ciprofloxacin, were of analytical grade.

2.2. Plant Collection and Fungal Isolation

The leaves and stem of D. salicifolia were collected from Abbotabad, Pakistan (34.1688° N, 73.2215° E). The leaves and stem of D. salicifolia were treated with 0.1% HgCl2 solution for 3 min, 70% (v/v) ethanol for 1 min, 1% (v/v) sodium hypochlorite for 5 min, and finally immersed in 70% (v/v) for 1 min for surface sterilization. After three rounds of washing with distilled water, the sterilized segments were patted dry on blotting paper. In order to prevent bacterial growth, the stem and leaf segments were chopped with sterile surgical blades and transferred to potato dextrose agar (Oxoid) treated with 100 mg/mL tetracycline. In order to verify the efficacy of surface sterilization, aliquots from the final rinsed water were likewise plated on the PDA plates. To start the fungal growth, the Petri plates were parafilm-sealed and incubated at 28 °C for 7 days [16]. A pure culture was obtained by subculturing the explants after mycelial development began to emerge after seven days of incubation. After being moved onto potato dextrose agar slants, pure colonies were stored for later use at 4 °C. The conserved fungi were occasionally subcultured.

2.3. Identification of Fungus

The morphological and microscopic identification of fungi was carried out according to the procedure reported by Kim et al. [23]. Potato Dextrose Broth (PDB) culture medium was inoculated with 30 mL preserved liquid cultures of endophytic F. fujikuroi. The flask was labeled as of DL 3.2. and incubated in a shaker incubator (IF30 Memmert, Eagle, WI, USA) for ten days at 28 °C. Saboraud Dextrose Agar (SDA) was used for morphological confirmation, inoculated with 10 µL of broth culture of DL 3.2. These plates were placed in a static incubator at 28 °C for five days. The fungal colony from the culture plate was put on a microscopic glass slide and teased with a needle. A drop of lactophenol cotton blue (LPCB) (oxoid) stain was flooded over the slide where the fungus was placed. Then, a cover slip was placed over the slide and examined under a light microscope (Leica Microsystems Inc., Buffalo Grove, Chicago, IL, USA).

2.4. Cultivation of Fusarium fujikuroi

For mass growth, a 6 L PDB medium was inoculated with broth culture of DL 3.2 strain. Flasks were incubated in a shaker incubator at 28 °C and 150 rpm for four weeks. The broth culture was then filtered through muslin cloth and vacuum filtered using Whatman No. 1 filter paper [24].

2.5. Extraction of Secondary Metabolites

In order to produce secondary metabolites, 150 mL of potato dextrose broth were autoclaved in a 500 mL Erlenmeyer flasks. The fungal culture was added to the medium and shaken at 170 rpm at 27 ± 1 °C for four weeks. Mycelium released secondary metabolites in the medium which were separated from the culture media by using muslin fabric. The metabolites were extracted from the crude culture broth by solvent extraction with ethyl acetate using a separating funnel. The solvent from metabolites was removed by using a rotary evaporator (Heidolph Scientific Products, Schwabach, Germany) and the concentrated extract was stored at 4 °C [25].

2.6. Fractionation of Metabolites by Column Chromatography

The crude extract (500 mL) was fractionated using a glass column (700 mm × 18 mm) packed with 100 g of silica gel (60–120 mesh, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Solvents of increasing polarity were applied sequentially to obtain distinct fractions. The solvent systems used were n-hexane (100%), n-hexane/chloroform (1:1, v/v), chloroform (100%), chloroform/ethyl acetate (1:1, v/v), ethyl acetate (100%), ethyl acetate/methanol (1:1, v/v), and methanol (100%). Each solvent phase (200 mL) was passed through the column twice to ensure complete elution of compounds. Eluates were collected in 50 mL fractions, concentrated using a rotary evaporator, and monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC), (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) for compound profile similarity. Fractions exhibiting identical TLC profiles were pooled and stored at 4 °C for antibacterial analysis [26,27]. The n-hexane/chloroform (1:1, v/v) fraction was represented by HCF. All chromatographic experiments were performed in triplicate to ensure reproducibility.

2.7. Antibacterial Activity of Fractions

Bacterial strains (Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Escherichia coli) were obtained from the departmental microbial culture collection (University of Haripur). These isolates originated from clinical sources and were selected as representative Gram-positive and Gram-negative human pathogens of clinical and pharmacological relevance. The agar well diffusion method was used to find out the antibacterial activity of different fractions against pathogenic bacteria including Bacillus subtilis, S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, and E. coli [28]. For each assay, 100 µL of bacterial inoculum (~1 × 108 CFU/mL) was spread uniformly on Mueller–Hinton agar plates. Wells of 6 mm diameter were filled with 80 µL of each fraction (dissolved at 50 mg/mL in the corresponding solvent). Each assay was performed in three biological replicates, each with three technical repeats. Pure n-hexane, chloroform, ethyl acetate, and methanol were used as negative controls, while ciprofloxacin (10 µg/mL) served as a positive control. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h, and the zone of inhibition (ZOI) was recorded as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Ciprofloxacin (10 µg/mL) was used as a positive control. All data were statistically analyzed as described in Section 2.11.

2.8. Thin Layer Chromatography of Bioactive Fractions

Fractions with bioactive potential were analyzed by TLC using Merck TLC Silica gel 60 F254 plates to find out the number of components in each extract [29]. A specified quantity (1 µL) of the concentrated fraction was spotted on the TLC plate using a capillary tube and the plate was immerged in HCF for 30 min. The spots/bands were visualized in UV chamber (UVphotonics NT GmbH, Berlin, Germany) at 254 nm to visualize each spot.

2.9. GC-MS Analysis

The crude extracts of F. fujikuroi were evaluated using GC-MS analysis using Clarus 600C GC-MS (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) fitted with an Elite-5 MS capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm). The initial temperature was adjusted to 50 °C, gradually increased to 230 °C at 5 °C/min for 30 min. Helium was used as the carrier gas, running with a 1 mL/min flow rate. The spectrum was observed between 40 and 600 m/z. The retention times of the several compounds that eluted from the GC column were noted and the mass spectra of the compounds were compared using TurboMass Software (version 6). The chemical compounds present in the extract were identified using the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) database. The database was searched for comparable compounds with the same molecular mass and retention time [30].

2.10. Toxicity Prediction

The potential toxicity of major bioactive compounds was evaluated in silico using the ProTox-II online tool (https://tox-new.charite.de/protox_II/, 10 November 2025). Parameters predicted included oral LD50 (mg/kg), toxicity class, and probabilities of neurotoxicity, carcinogenicity, and cytotoxicity [31].

2.11. Statistical Analysis

All data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) of three independent biological replicates, each consisting of three technical repeats. Data were expressed as mean ± SD of triplicate assays. Statistical comparisons among treatments were conducted using a two-factor factorial analysis of variance (ANOVA) in a completely randomized design (CRD), considering both solvent fraction and bacterial strain as factors. Significant differences among means were determined by Duncan’s multiple range (DMR) test at p < 0.05 using M-Stat-C software (version 1.3). Graphical presentation of results includes mean ± SD error bars and superscript letters denoting statistically different groups.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Isolation and Identification of F. fujikuroi

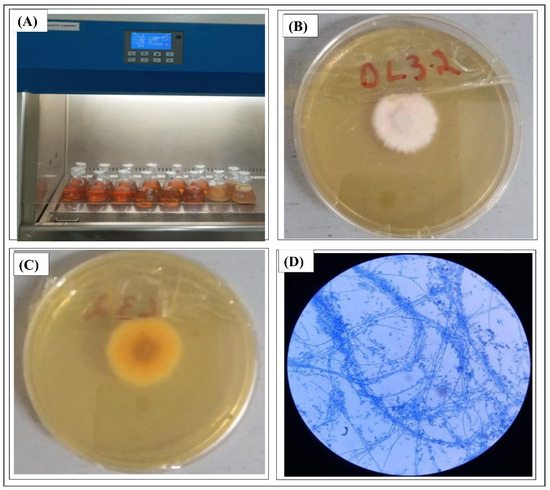

F. fujikuroi was isolated from the leaves and stem of Debregeasia salicifolia and the cultivation of fungus is shown in Figure 1A. The broth culture of Fusarium fujikuroi was grown on large scale for obtaining a large enough amount of extract for fractionation. For mass growth, 6 L PDB medium was poured into 12 Erlenmeyer flasks (500 mL), autoclaved and cooled. Then, these flasks were inoculated with DL 3.2 strains and incubated in a shaker incubator at 28 °C and 150 rpm for 4 weeks. Figure 1B shows that fungus formed a white colony on PDA plate while from the back side it shows a pinkish color (Figure 1C). The microscopic view of F. fujikuroi shows that the mycelium was aseptate since it had dispersed conidia, as shown in Figure 1D.

Figure 1.

(A) Cultivation of F. fujikuroi, (B) colony presentation of F. fujikuroi (DL 3.2) from front (C) view of DL3.2 from back side and (D) a microscopic view of F. fujikuroi.

3.2. Solvent Extraction of F. fujikuroi Filtrate

The culture filtrate (100 mL) was mixed with 200 mL ethyl acetate in a separating funnel, shaken for 10 min and kept for 30 min. Two immiscible layers were formed, i.e., organic layer and aqueous layer. The upper organic layer/ethyl acetate layer contained the desired compounds and collected as such, while the bottom layer was again mixed with 50 mL ethyl acetate in a separating funnel for extraction of any remaining compounds. Filtrate was extracted 3 times with ethyl acetate.

3.3. Fractionation of Crude Extract

Sample consisting of crude extract from F. fujikuroi (DL3.2) was loaded onto column packed with silica gel. Solvents of different polarities were passed through column for fractionation of the extract to separate bioactive metabolites. The solvents were then allowed to flow down through the column. The solvents selected for elution were n-hexane, n-hexane/chloroform (1:1, v/v), chloroform, chloroform/ethyl acetate (1:1, v/v), ethyl acetate, ethyl acetate/methanol (1:1, v/v) and methanol. Owing to the interaction of different chemical compounds with stationary phase and mobile phases, they were eluted the column in different time intervals and thus collected. Non-polar compounds were eluted with n-hexane, compounds of medium polarity were eluted by chloroform and ethyl acetate while highly polar compounds were eluted by methanol. In this way, the separation of compounds from the mixture was achieved. The fractions were collected in separate flasks and labeled with the eluent name such as n-hexane extract, ethyl acetate extract, etc.

3.4. Antibacterial Activities of Various Fractions

The fractions were collected from the column using different eluents, among which seven fractions showed antibacterial activity in agar well diffusion assay [32]. The antibacterial activities of different fractions of F. fujikuroi are presented in Table 1 and Figure 2 and Figure 3. It was observed that compounds soluble in hexane, chloroform, and ethyl acetate showed good antibacterial activity, while the extract obtained in methanol displayed no antimicrobial activity. Maximum activity was obtained for HCF with a 17.24 ± 0.64 mm inhibition zone against B. subtilis. The methanol fraction did not show any effect on bacterial growth. The n-hexane and ethyl acetate fractions showed ZOI of 13.7 ± 1. 52 mm and 12.3 ± 0.3 mm, respectively, against S. aureus. Table 1 shows the comparative analysis of bioactive fractions against E. coli, S. aureus, P. aeruginosa and B. subtilis strains. Ciprofloxacin (10 µg/mL) was used as a positive control, which produced inhibition zones of 19.35 ± 1.2 mm, 17.75 ± 2.5 mm, 20.71 ± 2.3 mm, and 19.92 ± 2.1 mm against E. coli, S. aureus, P. aeruginosa and B. subtilis, respectively.

Table 1.

Diameter of inhibition zone (mm) (mean ± SD) of fractions of F. fujikuroi against E. coli, S. aureus, P. aeruginosa and B. subtilis. The results were obtained in triplicate (n = 3), with Duncan’s test, p < 0.05, while lowercases are the output of Duncan’s Multiple Range Test, which is a post-hoc test.

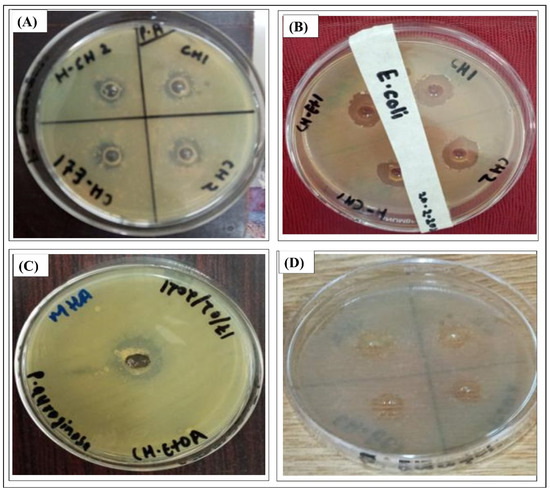

Figure 2.

Antibacterial activities of different fractions of F. fujikuroiI extract (A) chloroform, HCF, chloroform/ethyl acetate (1:1, v/v) against Staphylococcus aureus, (B) chloroform and chloroform/ethyl acetate (1:1, v/v) against E. coli, (C) chloroform/ethyl acetate (1:1, v/v) against Pseudomonas auroginosa, and (D) chloroform/ethyl acetate (1:1, v/v) against Bacillus subtilis.

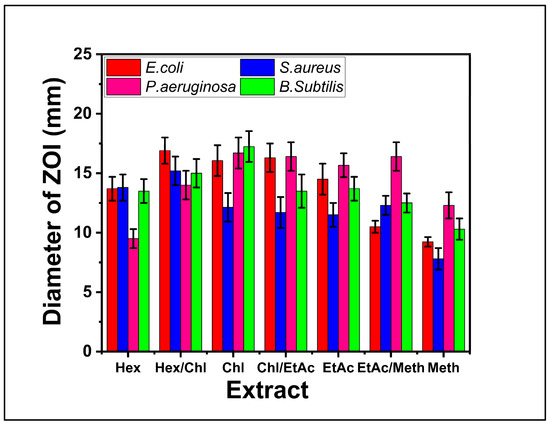

Figure 3.

Antibacterial activities of different bioactive fractions of F. fujikuroi obtained in different solvents against E.coli, S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, and B. subtilis.

Similarly, the antibacterial activities of different fractions of F. fujikuroi extract are shown in Figure 2. The results in Figure 2A show the antibacterial activities of chloroform, HCF, chloroform/ethyl acetate (1:1, v/v) fractions in 4 wells tested against Staphylococcus aureus. The results in Figure 2B show the antibacterial activity of chloroform and chloroform/ethyl acetate (1:1, v/v) against E. coli. Figure 2C shows the antibacterial activity of chloroform/ethyl acetate (1:1, v/v) against Pseudomonas auroginosa while Figure 2D shows the antibacterial activity of chloroform/ethyl acetate (1:1, v/v) extract against Bacillus subtiles.

The antibacterial activity of F. fujikuroi extracts were determined against clinical human pathogenic bacteria including E. coli, S. aureus, P. aeruginosa and B. subtilis in terms of ZOI and are shown in Figure 3. The results show that most of the fractions have shown significant activity against E. coli, S. aureus, P. aeruginosa and B. subtilis. For E. coli and S. aureus bacteria the highest antibacterial activity was obtained for HCF while for P. aeruginosa and B. subtilis the highest antibacterial activity was obtained for chloroform fraction. For HCF with 17.24 ± 0.64 mm inhibition zone at B. subtilis inoculated plates. Zones for other fractions ranged from 10 mm to 18 mm as shown in Figure 3. The lowest antibacterial activity was achieved for methanol fraction as shown in Figure 3.

The antibacterial activities of F. fujikuroi extract against the selected strain of bacteria are comparable with other studies reported in the literature. The hexane and ethyl acetate fractions of endophytic fungus Emericella quadrilineata RS-5 extract have shown ZOI of 14.5 ± 0.7 mm and 10 ± 0.8 mm, respectively, against S. aureus. In the present study, the n-hexane and ethyl acetate fractions of F. fujikuroi extract have shown the ZOI of 13.7 ± 1. 52 mm and 12.3 ± 0.3 mm, respectively, against S. aureus. Similarly, in the present study, the maximum activity was found for HCF with 18 mm inhibition zone for B. subtilis while ZOI of 20 mm was reported against B. subtilis using endophytic fungus extract isolated from Dipterocarpous trees [33]. Error bars represent mean ± SD (n = 3). Statistical analysis (ANOVA, p < 0.05) indicated significant differences among solvent fractions, with the HCF showing the highest inhibition against B. subtilis and E. coli.

3.5. GC-MS Analysis of Different Fractions

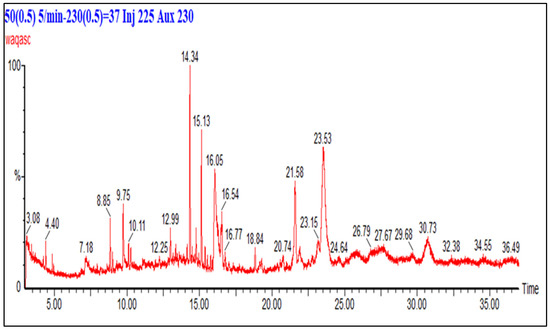

3.5.1. GC-MS Analysis of n-Hexane Fraction

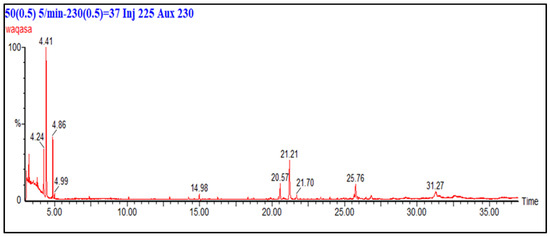

Figure 4 show the GC-MS analysis of the n-hexane fraction of F. fujikuroi extract. The chromatogram in Figure 4 shows 10 major peaks correspond to 10 different compounds. The analyte detected by GC-MS are ethylbenzene (4.24 min), p-xylene (4.41 min), 1,3 dimethylbenzene (4.86 min), hentriacontane (20.57), 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol (21.21 min), and hentriacontane derivatives (25.76 min and 31.27 min). This shows that major compounds present in the hexane fraction are linear chains and aromatic hydrocarbons. GC-MS profile of n-hexane fraction is similar to compounds identified in the bacterium Paracoccus pantotrophus FMR19 [34,35]. They reported that hentriacontane, dodecane, phenols, and benzene derivatives identified in GC-MS displayed significant activity against clinical pathogens and multidrug-resistant organisms. Similarly, Emericella quadrilineata produced 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol and long-chain alkanes responsible for antibacterial activity [36]. The presence of similar phenolic and hydrocarbon compounds in F. fujikuroi fractions suggests comparable bioactivity mechanisms. Moreover, 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol (2,4-DTBP) has been isolated from multiple endophytes [37]. This compound exerts antibacterial and anti-virulence activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus and other pathogens. Similarly, Fatty-acid esters and phthalate esters such as bis-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate/di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate have been isolated from fungi which have shown antibacterial activity [38].

Figure 4.

GC chromatogram of n-hexane fraction of F. fujikuroi extract. Column (30 m × 0.25 mm), temperature 50–230 °C, carrier gas: helium running at 1 mL/min.

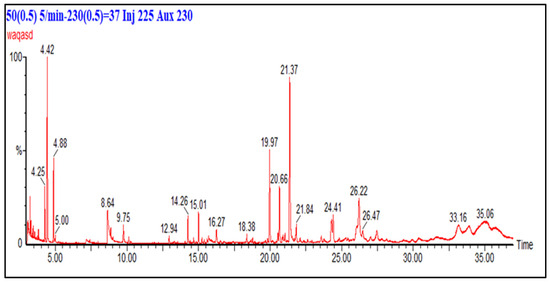

3.5.2. GC- MS Analysis of HCF

The GC-MS analysis of HCF of F. fujikuroi is shown in Figure 5. The chromatogram shows some significant peaks which were compared with the NIST mass spectra library for identification. The compounds identified in the HCF of F. fujikuroi are linear chain hydrocarbons, aromatic hydrocarbons, esters of fatty acids, and phenols. The major compounds are hentriocantane (8.85 min), nitrobenzene (9.75 min), 6 ethyloct-3-yl-isobutyl ester (10.11 min), 1,3 bis 1,1-dimethyl ethyl) (14.34 min), hentriocantane (15.13 min), m-aminophenyl acetylene (16.05 min), hentriocantane derivative (21.58 min) and 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol (23.53 min). Another study has reported the presence of benzene and its derivatives as major constituents of the extracted compounds from plants and their endophytes [39]. The antibacterial potential of benzene-related isolated from medicinal plants and fungi have been reported by several research studies [40]. The presence of carbonic acid, decyl phenyl ester, fatty acids and esters of fatty acids in HCF of F. fujikuroi is in close agreement with another study reported in the literature and these compounds have shown excellent antibacterial activity [41]. Similarly, another major compound in HCF of F. fujikuroi is 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol while the presence of phenols in the extract of Combritum albidum which displayed significant biological activities have been reported in the literature [42].

Figure 5.

GC chromatogram of HCF of F. fujikuroi extract. Column (30 m × 0.25 mm), temperature 50–230 °C, carrier gas: helium running at 1 mL/min.

3.5.3. GC-MS Analysis of Chloroform Fraction

The GC-MS analysis of the chloroform fraction of F. fujikuroi extract is shown in Figure 6. The major compounds identified from the chloroform fraction of F. fujikuroi are linear chain hydrocarbons, aromatic hydrocarbons, esters of fatty acids, alcohol, phenol, furan derivatives, barbiturate derivatives, sydnone derivatives and others. The major peaks in chromatogram correspond to p-xylene (4.42 min), 1,3-dimethylbenzene (4.88 min), 3-ureidopropionic acid (8.64 min), nitrobenzene (9.75 min), sydnone (12.94 min), 1,3-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-benzene (14.26 min), hentriacontane (15.01 min), 2, 5-cyclohexadiene (19.97 min), hentriacontane derivative (20.66 min), 2,4-di-tert butylphenol (21.37 min), 1,4,4,6-tetramethyl-7,8-octahydrocyclopenta (24.41 min) hentriacontane derivative (26.22 min) and 2-ethylhexyl nonyl ester carbonic acid (26.47 min). Sydnones, aliphatic and cyclic alcohols identified in the chloroform extract of F. fujikuroi have therapeutic effects including anticancer, antidiabetic and antimicrobial effects.

Figure 6.

GC chromatogram of chloroform fraction of F. fujikuroi extract. Column (30 m × 0.25 mm), temperature 50–230 °C, carrier gas: helium running at 1 mL/min.

The chemical compounds identified in n-hexane fraction, HCF and chloroform fraction of F. fujikuroi extract are given in Table 2. The retention times, chemical formulas and biological activities of these compounds are also presented and the corresponding literature has been cited where the biological activities of specific compounds have been evaluated. There are some compounds whose biological activities have been evaluated so far. These results indicating that F. fujikuroi contain several bioactive compounds which have antibacterial activities while other biological activities such as anticancer and antioxidant activities have not been evaluated. Chemical constituents were identified by comparing their mass spectra and retention times with entries in the NIST 2011 mass spectral library. Compounds showing a spectral similarity index of ≥80% were considered confidently identified and are listed in Table 2 along with their retention times, molecular formulas, and putative structures. Peaks with similarity scores below 80% or spectra corresponding only to general chemical classes. The unidentified peaks GC-MS spectra which are presented in Table 2 as not reported may represent potentially novel or co-eluting compounds that warrant further purification and structural elucidation in future work.

Table 2.

Selected bioactive compounds identified in different fractions (n-hexane, HCF, and chloroform) of F. fujikuroi extract analyzed by GC-MS.

3.6. In Silico Toxicity Prediction of Bioactive Compounds in F. fujikuroi

To gain preliminary insights into the safety profile of the major bioactive compounds identified from the different fractions, in silico toxicity predictions were performed using the ProTox-II online platform and the results are presented in Table 3. The predicted parameters included oral LD50 (mg/kg), toxicity class, and potential for neurotoxicity, carcinogenicity, and cytotoxicity. The results (Table 3) revealed that the compounds exhibited LD50 values ranging from 450 mg/kg to 4100 mg/kg, corresponding to toxicity classes 3–5, which indicate low to moderate toxicity. Notably, hentriacontane, present in multiple fractions (CF, HCF, and HF), showed a relatively lower LD50 (750 mg/kg; class 3) but was predicted to be inactive for neurotoxicity and carcinogenicity, though cytotoxic activity was indicated. In contrast, 2,5-Cyclohexadiene and 1,4,4,6-tetramethyl-octahydrocyclopentan exhibited higher LD50 values (2700–4100 mg/kg; class 5), suggesting lower toxicity potential. Compounds such as m-aminophenyl acetylene and 6-ethyloct-3-yl isobutyl ester showed moderate toxicity (LD50 = 450–900 mg/kg; class 4), with m-aminophenyl acetylene predicted to have neurotoxic and cytotoxic effects. Overall, the in silico toxicity analysis suggests that most of the major components possess acceptable safety margins, with limited predicted risks of carcinogenicity. These findings provide an initial toxicological assessment that supports the potential of these fractions for further biological and pharmacological evaluation, though experimental validation through in vitro and in vivo assays will be necessary in future work.

Table 3.

In silico toxicity prediction of major bioactive compounds identified from different fractions using the ProTox-II online tool, (toxicity level: highest = 1, lowest = 5).

4. Conclusions

In this study, the endophytic fungus Fusarium fujikuroi, isolated from the medicinal plant Debregeasia salicifolia, was cultivated and its bioactive metabolites were systematically extracted and fractionated. Ethyl acetate solvent extraction yielded a crude extract, which was subsequently fractionated using gravity column chromatography with a silica gel stationary phase. Bioactive compounds were eluted with solvents of varying polarity, including n-hexane, HCF and chloroform, to obtain distinct fractions. These fractions were evaluated for their biological activities and subjected to GC-MS analysis for compound identification. The GC-MS results revealed that F. fujikuroi produces a diverse array of bioactive metabolites, including both previously reported compounds and several new constituents not yet documented in the literature which need to be further purified and characterize to find out their chemical structure and composition. These findings underscore the potential of endophytic fungi as prolific sources of antimicrobial agents, which could help address the growing challenge of antibiotic resistance. The methodology employed in this study from fungal isolation to compound fractionation and characterization provides a reproducible framework for isolating bioactive metabolites not only from endophytic fungi but also from medicinal plants. Future studies should focus on the large-scale purification and structural elucidation of the unidentified compounds detected in this study. Further biological assays, including mechanistic studies and toxicity evaluations, will be essential to assess their therapeutic potential. If successfully developed, these bioactive metabolites could offer viable alternatives to conventional antibiotics, contributing to the global fight against drug-resistant pathogens.

Author Contributions

Z.F.: Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing—Original Draft, Data Curation. S.N.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing—Review and Editing. E.Y.S.: Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Software, Validation, Writing—Review and Editing. R.M.K.O.: Formal Analysis, Project Administration, Resources, Software, Validation, Writing—Review and Editing. A.A.: Conceptualization, Investigation, Supervision, Visualization, Data curation, Writing—Review and Editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Taif University, Saudi Arabia, Project number TU-DSPP-2024-225. The authors are also thankful to Higher Education Commission (HEC), Pakistan for supporting this work through project No. 199/IPFP-II(Batch-I)/SRGP/NAHE/HEC/2020/197.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to Taif University, Saudi Arabia, for supporting this work through project number (TU-DSPP-2024-225). The authors would also like to thank the University of Haripur, Pakistan for providing laboratory facilities to execute this work.

Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Kaul, S.; Gupta, S.; Ahmed, M.; Dhar, M.K. Endophytic fungi from medicinal plants: A treasure hunt for bioactive metabolites. Phytochem. Rev. 2012, 11, 487–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M.; Gururani, M.A.; Ali, A.; Bajwa, S.; Hassan, R.; Batool, S.W.; Imam, M.; Wei, D. Antimicrobial Properties and Therapeutic Potential of Bioactive Compounds in Nigella sativa: A Review. Molecules 2024, 29, 4914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qadri, M.; Johri, S.; Shah, B.A.; Khajuria, A.; Sidiq, T.; Lattoo, S.K.; Abdin, M.Z.; Riyaz-Ul-Hassan, S. Identification and bioactive potential of endophytic fungi isolated from selected plants of the Western Himalayas. Springerplus 2013, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nisa, S.; Bibi, Y.; Masood, S.; Ali, A.; Alam, S.; Sabir, M.; Qayyum, A.; Ahmed, W.; Alharthi, S.; Santali, E.Y.; et al. Isolation, Characterization and Anticancer Activity of Two Bioactive Compounds from Arisaema flavum (Forssk.) Schott. Molecules 2022, 27, 7932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altemimi, A.; Lakhssassi, N.; Baharlouei, A.; Watson, D.G.; Lightfoot, D.A. Phytochemicals: Extraction, Isolation, and Identification of Bioactive Compounds from Plant Extracts. Plants 2017, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.W.; Xu, B.G.; Wang, J.Y.; Su, Z.Z.; Lin, F.C.; Zhang, C.L.; Kubicek, C.P. Bioactive metabolites from Phoma species, an endophytic fungus from the Chinese medicinal plant Arisaema erubescens. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 93, 1231–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X. Antibacterial, Antifungal, and Antiviral Bioactive Compounds from Natural Products. Molecules 2024, 29, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riga, R.; Wardatillah, R.; Suryani, O.; Ryplida, B.; Suryelita, S.; Azhar, M.; Handayani, D.; Artasasta, M.A.; Benu, S.M.; Putra, A. Endophytic fungus from Gynura japonica: Phytochemical screening, biological activities, and characterisation of its bioactive compound. Nat. Prod. Res. 2025, 39, 4117–4125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogofure, A.G.; Pelo, S.P.; Green, E. Identification and Assessment of Secondary Metabolites from Three Fungal Endophytes of Solanum mauritianum Against Public Health Pathogens. Molecules 2024, 29, 4924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pun, B.; Joshi, S.R. Bioprospection unveils the bioactive potential of Colletotrichum taiwanense BPSRJ3, an endophytic fungus of an ethnomedicinal orchid, Vanda cristata Wall. Ex Lindl. Syst. Microbiol. Biomanufacturing 2025, 5, 754–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashem, A.H.; Attia, M.S.; Kandil, E.K.; Fawzi, M.M.; Abdelrahman, A.S.; Khader, M.S.; Khodaira, M.A.; Emam, A.E.; Goma, M.A.; Abdelaziz, A.M. Bioactive compounds and biomedical applications of endophytic fungi: A recent review. Microb. Cell Fact. 2023, 22, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A.; Meshram, V.; Gupta, M.; Goyal, S.; Qureshi, K.A.; Jaremko, M.; Shukla, K.K. Fungal Endophytes: Microfactories of Novel Bioactive Compounds with Therapeutic Interventions; A Comprehensive Review on the Biotechnological Developments in the Field of Fungal Endophytic Biology over the Last Decade. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawar, S.N.; Taha, Z.K.; Hamied, A.S.; Al-Shmgani, H.S.; Sulaiman, G.M.; Elsilk, S.E. Antifungal Activity of Bioactive Compounds Produced by the Endophytic Fungus Paecilomyces sp. (JN227071.1) against Rhizoctonia solani. Int. J. Biomater. 2023, 2023, 2411555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omomowo, I.O.; Amao, J.A.; Abubakar, A.; Ogundola, A.F.; Ezediuno, L.O.; Bamigboye, C.O. A review on the trends of endophytic fungi bioactivities. Sci. Afr. 2023, 20, e01594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Shen, X.; Zhu, B.; Qin, L. Roles of endophytic fungi in medicinal plant abiotic stress response and TCM quality development. Chin. Herb. Med. 2024, 16, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisa, S.; Khan, N.; Shah, W.; Sabir, M.; Khan, W.; Bibi, Y.; Jahangir, M.; Haq, I.U.; Alam, S.; Qayyum, A. Identification and Bioactivities of Two Endophytic Fungi Fusarium fujikuroi and Aspergillus tubingensis from Foliar Parts of Debregeasia salicifolia. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2020, 45, 4477–4487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibi, A.; Mubeen, F.; Rizwan, A.; Ullah, I.; Hammad, M.; Waqas, M.A.B.; Ikram, A.; Abbas, Z.; Halterman, D.; Saeed, N.A. Morpho-Molecular Identification of Fusarium equiseti and Fusarium oxysporum Associated with Symptomatic Wilting of Potato from Pakistan. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toghueo, R.M.K. Bioprospecting endophytic fungi from Fusarium genus as sources of bioactive metabolites. Mycology 2020, 11, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, J.J.; Zabot, G.L.; Tres, M.V.; Harakava, R.; Kuhn, R.C.; Mazutti, M.A. Fusarium fujikuroi: A novel source of metabolites with herbicidal activity. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2018, 14, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janevska, S.; Baumann, L.; Sieber, C.M.K.; Münsterkötter, M.; Ulrich, J.; Kämper, J.; Güldener, U.; Tudzynski, B. Elucidation of the Two H3K36me3 Histone Methyltransferases Set2 and Ash1 in Fusarium fujikuroi Unravels Their Different Chromosomal Targets and a Major Impact of Ash1 on Genome Stability. Genetics 2018, 208, 153–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amuzu, P.; Pan, X.; Hou, X.; Sun, J.; Jakada, M.A.; Odigie, E.; Xu, D.; Lai, D.; Zhou, L. Recent Updates on the Secondary Metabolites from Fusarium Fungi and Their Biological Activities (Covering 2019 to 2024). J. Fungi 2024, 10, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanasoff-Kardjalieff, A.K.; Studt, L. Secondary Metabolite Gene Regulation in Mycotoxigenic Fusarium Species: A Focus on Chromatin. Toxins 2022, 14, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.Y.; Yeo, S.H.; Baek, S.Y.; Choi, H.S. Molecular and morphological identification of fungal species isolated from bealmijang meju. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 21, 1270–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, R.; Li, S.; Zhu, L.; Yin, Z.; Hu, D.; Liu, C.; Mo, F. A review on co-cultivation of microalgae with filamentous fungi: Efficient harvesting, wastewater treatment and biofuel production. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 139, 110689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, M.; Fang, Z. Efficient physical extraction of active constituents from edible fungi and their potential bioactivities: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 105, 468–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Tan, J.; Nima, L.; Sang, Y.; Cai, X.; Xue, H. Polysaccharides from fungi: A review on their extraction, purification, structural features, and biological activities. Food Chem. X 2022, 15, 100414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, T.; Juhász, A.; Bose, U.; Shiferaw Terefe, N.; Colgrave, M.L. Research trends in production, separation, and identification of bioactive peptides from fungi—A critical review. J. Funct. Foods 2024, 119, 106343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.; Zhang, W.; Wu, C.; Feng, H.; Peng, Y.; Shahid, H.; Cui, Z.; Ding, P.; Shan, T. Diversity and antibacterial activity of fungal endophytes from Eucalyptus exserta. BMC Microbiol. 2021, 21, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.M.; Agatonovic-Kustrin, S.; Lim, F.T.; Ramasamy, K. High-performance thin layer chromatography-based phytochemical and bioactivity characterisation of anticancer endophytic fungal extracts derived from marine plants. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2021, 193, 113702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, N.; Arora, D.S.; Kalia, N.; Kaur, M. Bioactive potential of endophytic fungus Chaetomium globosum and GC-MS analysis of its responsible components. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muharrami, L.K.; Santoso, M.; Fatmawati, S. Chemical profiles, in silico pharmacokinetic and toxicity prediction of bioactive compounds from Boesenbergia rotunda. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2024, 10, 100992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Prasher, I.B. Antimicrobial potential of endophytic fungi isolated from Dillenia indica L. and identification of bioactive molecules produced by Fomitopsis meliae (Undrew.) Murril. Nat. Prod. Res. 2022, 36, 6064–6068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, C.; Ma, S.; Shi, X.; Xue, W.; Liu, C.; Ding, H. Diversity and Antimicrobial Activity of Endophytic Fungi Isolated from Chloranthus japonicus Sieb in Qinling Mountains, China. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodoira, R.; Maestri, D. Phenolic Compounds from Nuts: Extraction, Chemical Profiles, and Bioactivity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 927–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faridha Begum, I.; Mohankumar, R.; Jeevan, M.; Ramani, K. GC-MS Analysis of Bio-active Molecules Derived from Paracoccus pantotrophus FMR19 and the Antimicrobial Activity Against Bacterial Pathogens and MDROs. Indian J. Microbiol. 2016, 56, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goutam, J.; Sharma, G.; Tiwari, V.K.; Mishra, A.; Kharwar, R.N.; Ramaraj, V.; Koch, B. Isolation and Characterization of “Terrein” an Antimicrobial and Antitumor Compound from Endophytic Fungus Aspergillus terreus (JAS-2) Associated from Achyranthus aspera Varanasi, India. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R.; Kushveer, J.S.; Khan, M.I.K.; Pagal, S.; Meena, C.K.; Murali, A.; Dhayalan, A.; Venkateswara Sarma, V. 2,4-Di-Tert-Butylphenol Isolated from an Endophytic Fungus, Daldinia eschscholtzii, Reduces Virulence and Quorum Sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, M.R.; Salman, M.; Tariq, A.; Tawab, A.; Zahoor, M.K.; Naheed, S.; Shahid, M.; Ijaz, A.; Ali, H. The Antibacterial and Larvicidal Potential of Bis-(2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate from Lactiplantibacillus plantarum. Molecules 2022, 27, 7220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, R.-Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, R.-H.; Wang, X.-B.; Li, T.-X.; Kong, L.-Y.; Yang, M.-H. Benzophenone derivatives from the plant endophytic fungus, Pestalotiopsis sp. Phytochem. Lett. 2017, 22, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajilogba, C.F.; Babalola, O.O. GC–MS analysis of volatile organic compounds from Bambara groundnut rhizobacteria and their antibacterial properties. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 35, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radić, N.; Strukelj, B. Endophytic fungi: The treasure chest of antibacterial substances. Phytomedicine 2012, 19, 1270–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varsha, K.K.; Devendra, L.; Shilpa, G.; Priya, S.; Pandey, A.; Nampoothiri, K.M. 2,4-Di-tert-butyl phenol as the antifungal, antioxidant bioactive purified from a newly isolated Lactococcus sp. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2015, 211, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alufasi, R.; Chingwaru, W.; Zvidzai, C.J.; Musili, N.; Chakauya, E.; Lebea, P.; Goredema, M.; Zhou, R.; Stefanakis, A.I.; Parawira, W. Bioremediation of Bacteria in Constructed Wetlands: Role of Endophytic and Rhizosphere Fungi. Water 2025, 17, 2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundar, R.D.V.; Arunachalam, S. 2,4-Di-tert-butylphenol from Endophytic Fungi Fusarium oxysporum attenuates the growth of multidrug-resistant pathogens. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1575021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehabeldine, A.M.; Abdelaziz, A.M.; Abdel-Maksoud, M.A.; El-Tayeb, M.A.; Kiani, B.H.; Hussein, A.S. Antimicrobial characteristics of endophytic Aspergillus terreus and acute oral toxicity analysis. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 2024, 72, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manganyi, M.C.; Tchatchouang, C.K.; Regnier, T.; Bezuidenhout, C.C.; Ateba, C.N. Bioactive Compound Produced by Endophytic Fungi Isolated from Pelargonium sidoides Against Selected Bacteria of Clinical Importance. Mycobiology 2019, 47, 335–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).