Abstract

The market for bioactive compounds of natural origin has expanded greatly over the past few years. These compounds can be found as individual supplements or food additives. Due to the importance of this market, incorrect data on their composition can often be found. Therefore, monitoring their concentration is of great importance. Although there are various methods for their selective and sensitive determination, electrochemical sensors represent an important tool in this field. With the development of nanotechnology, additional importance has been given to these sensors. Strictly controlled synthesis procedures can yield nanomaterials with unique morphological properties and significantly improved electrocatalytic capabilities. The integration of two or more nanomaterials in the form of a nanocomposite and/or nanohybrids allows for the synergistic effect of each of the components. Thus, excellent final characteristics are obtained in the field of electrochemical sensors, such as improved sensor stability, selectivity, and lower detection limits. In recent years, various forms of carbon nanomaterials, polymer films, metal and metal oxide nanoparticles (or simply metal/metal oxide nanoparticles), MOFs, porous nanomaterials, MXenes, and others with clearly defined characteristics represent an important step forward in this field. Carefully prepared, these materials achieve strong interactions with selected analytes, which results in significant progress in analytical methods for monitoring biologically active compounds. Therefore, this review summarizes the latest trends in this field, focusing on the method of material preparation, final morphology and electrocatalytic properties, selectivity, and sensitivity. Conclusions and expected future directions in this field are also given in order to improve current analytical performance.

1. Introduction

Bioactive compounds are substances that have the ability to affect living organisms, including humans, and alter their biological functions. These compounds can be of plant origin (polyphenols, alkaloids, terpenes, saponins) or found in animals (hormones, neurotransmitters, peptides), while some of them originate from microorganisms (antibiotics, toxins, secondary metabolites), but can also be ingested with food (flavonoids, omega-3 fatty acids, caffeine, probiotics) [1]. Table 1 shows their classification based on their chemical nature and structure. Bioactive compounds are not essential for maintaining vital functions, but, even in low concentrations, they act specifically on the body with their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antitumor, neuroprotective, and/or immunomodulatory effects [2]. These substances can also be used in the prevention and treatment of many diseases (cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, etc.) [3], and have recently become promising as incorporated additives to food products, despite many challenges [4,5]. In addition to the beneficial effect, biologically active compounds can be harmful and even lethal, depending on the method of use and the dose (e.g., nicotine, morphine, botulinum protein, snake venoms, toxic alkaloids from plants such as atropine, strychnine etc.) [6]. Hence, the analytical monitoring of bioactive compounds in real samples in which these compounds are found is of paramount importance for ecosystems in nature [7]. Their accurate dosage and checking in food are also important. Bearing in mind the health of people and animals, it is extremely important to control the effectiveness of bioactive substances, their possible toxicity, and their misuse by monitoring these compounds or their metabolites, above all in the body fluids of the organisms [8].

Table 1.

Classification according to chemical nature and structure.

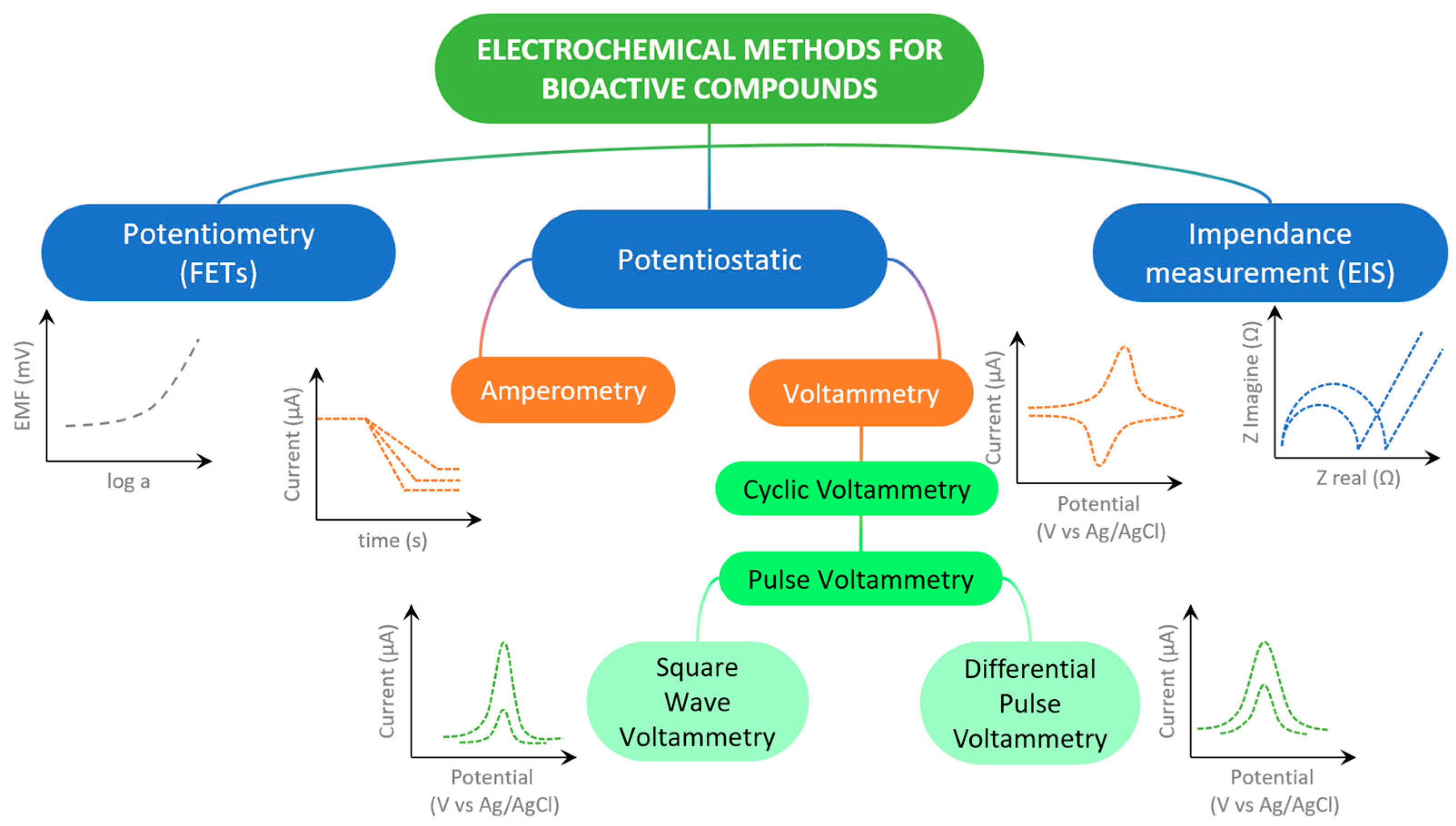

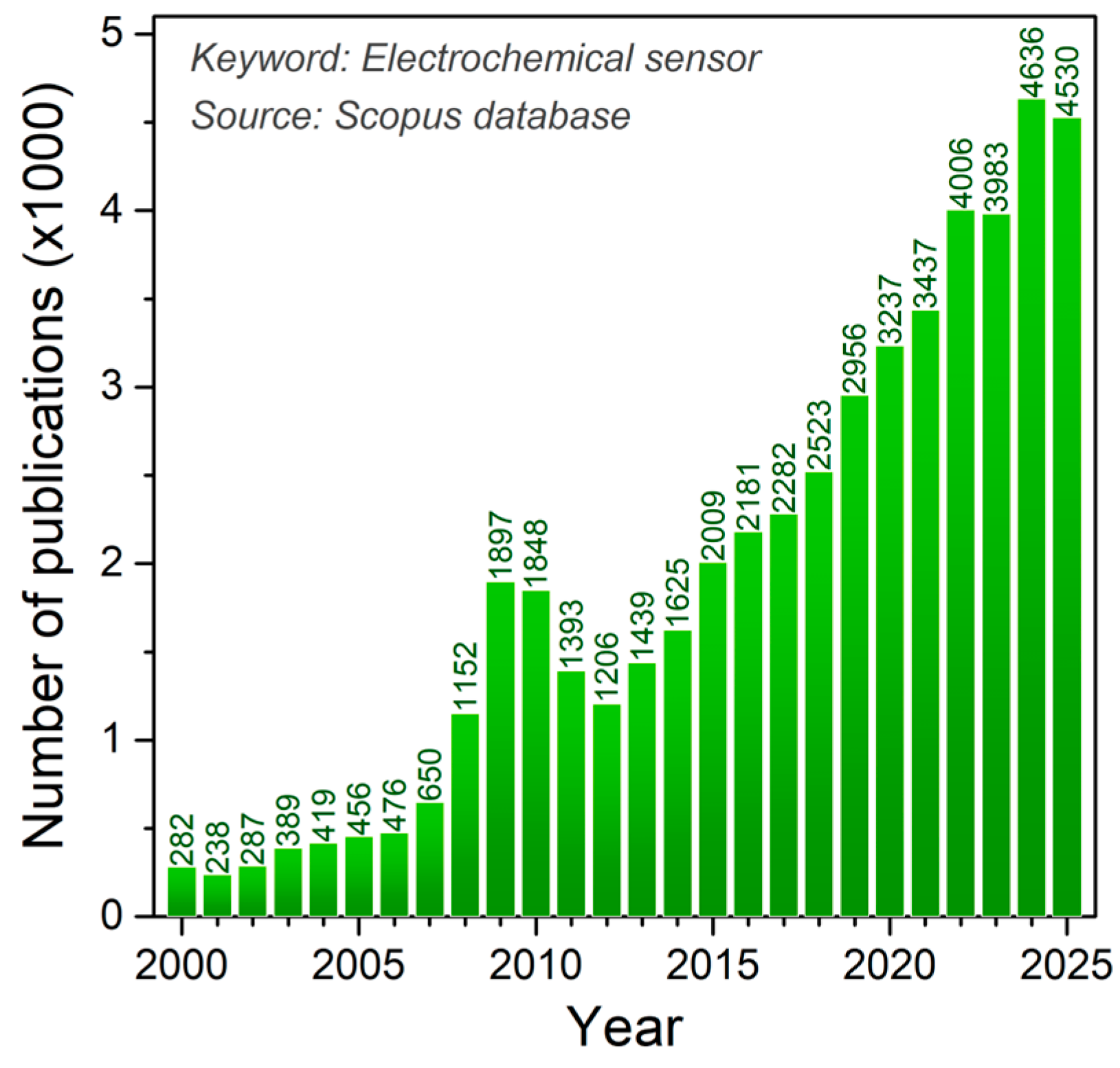

The determination of bioactive substances is preceded by sample preparation with the isolation and extraction of the targeted chemical species. The methods of quantification and identification of bioactive compounds can be different [9], and the first of these methods involves the use of techniques such as HPLC and MS, with their combination and some hybrid techniques, while spectrophotometric methods are used for the determination of total polyphenolic content (TPC) using Folin–Ciocalteu reagent, usually expressed by gallic acid equivalents [10], and the determination of antioxidant activity is achieved with different radical reagents (DPPH, ABTS, ORAC, FRAP, and TEAC assays) [11]. Electrochemical sensors and the electrochemical techniques used (Figure 1) offer a promising alternative to the aforementioned expensive and sophisticated analytical systems for determining biologically active substances, as this approach is significantly cheaper to produce and apply, uses only small amounts of analytes and samples, and simple samples may be used directly, but complex matrices such as serum, urine, and food typically require clean-up or extraction to preserve selectivity and avoid electrode fouling [12]. Electrochemical sensors do not have to be tied to laboratories because these devices are portable and easy to handle, thus enabling real-time analysis and point-of-care diagnostics [13]. It is of particular importance that electrochemical sensors can be specifically designed, like, for example, in the form of replaceable screen-printed electrodes (SPEs) and disposable inject-printed electrodes, modified by various mechanisms [14], and applied in the detection of biomarkers [15], important substances in food products [16], or flexible strips in clinical analyses [17]. During the development of electrochemical sensors, the possibility of electrode modification with various materials and chemical and biological components in order to selectively and even specifically determine the target bioactive analyte in real samples is outstanding [18,19]. It should be noted that these miniature devices are a rapidly developing technologically because they support the trend of biomimetic function, sustainable development, and eco-friendly approach through the use of “green” materials and technologies [20]. The literature concerning sensor preparation for diverse applications is vast and constantly expanding, with electrochemical sensors representing a particularly prominent area of study (Figure 2).

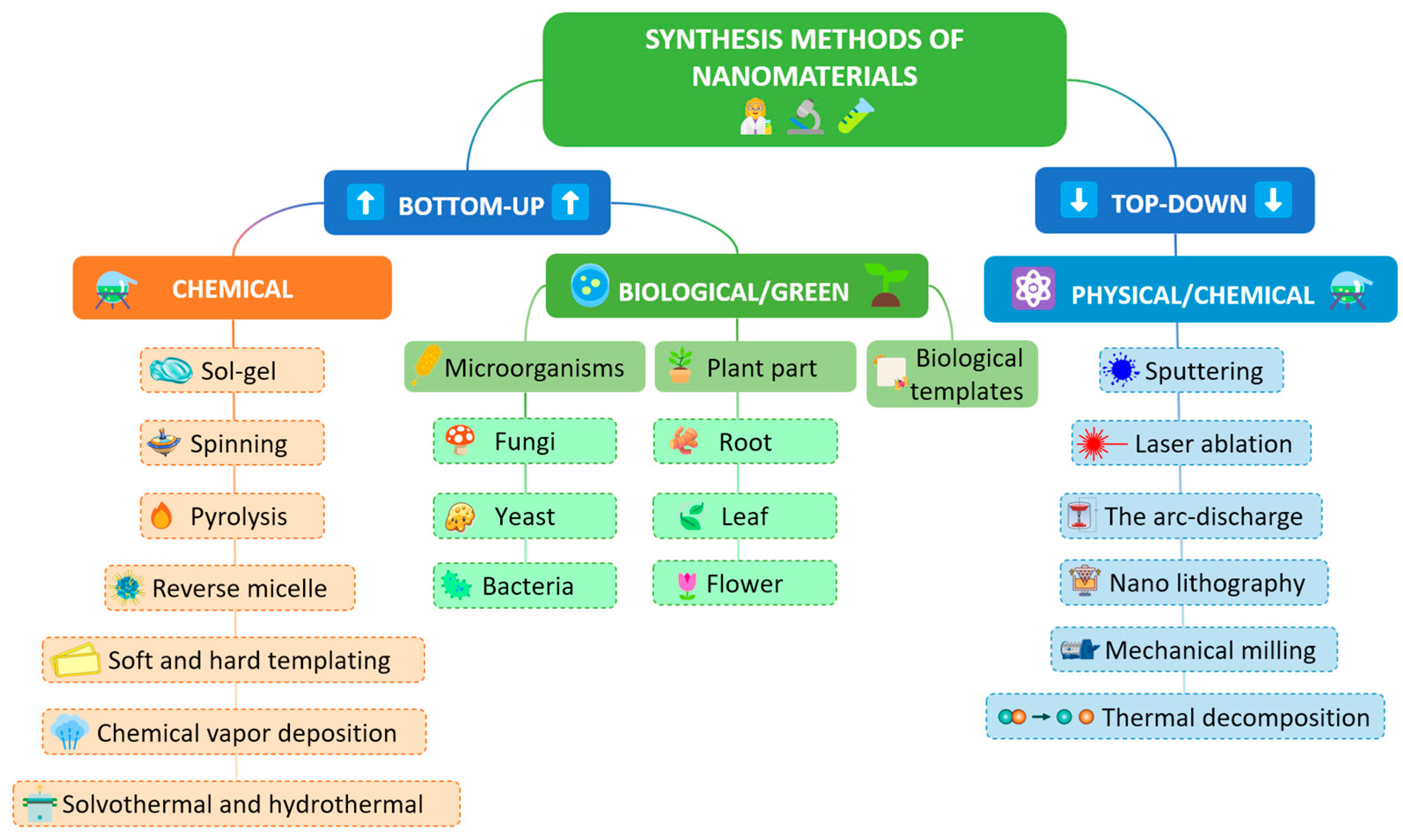

Figure 1.

Scheme of most used electrochemical techniques in determining of bioactive compounds.

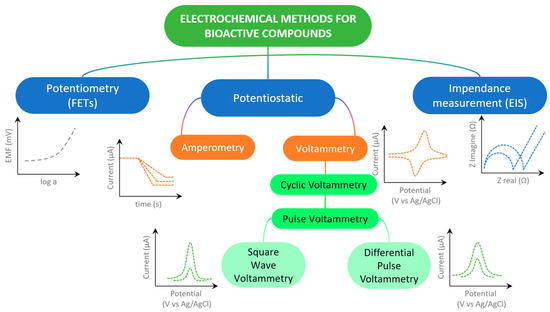

Figure 2.

Number of publications per year using Electrochemical sensor as a keyword (Source Scopus).

The electrochemical sensors considered in this review paper typically monitor the concentration of the target chemical species through the oxidation or reduction in the analyte at the electrode surface, employing amperometric or voltammetric techniques. In biosensors and sensors based on molecularly imprinted polymers, the electrode surface is functionalized with biological or synthetic receptors, which undergo changes in their electrical properties upon analyte binding; these changes are then detected using appropriate techniques, such as electrochemical impedance spectroscopy, which measures charge transfer resistance. Variations in ion equilibrium within a membrane are monitored using ion-selective electrodes, corresponding to potentiometric sensors. Nanomaterials used in the aforementioned electrochemical sensors act as signal amplifiers and catalysts for analyte–electrode interactions, and also enhance the sensitivity, selectivity, reaction rate, and stability of those analytical devices. This paper focuses on the application of various nanomaterials for the modification of electrode surfaces and the strategies of electrode modifier preparation for determinations of bioactive compounds in the last five years, that have exceptional importance in the improvement of the scientific field of electrochemical sensors. The authors’ goal is to systematically present and compare the achievements so far through selected scientific articles, as well as to highlight the advantages and also to point to the disadvantages and limitations of the application of various nanomaterials and electrode modification methods. In this review, we selected recently published, highly cited, high-quality papers that deal with nanomaterials as electrode modifiers for designing electrochemical sensors. These works were also chosen to illustrate how individual materials and sensor-development strategies (described in detail in the respective chapters) contribute to improving the performance of sensors designed for biologically active molecules in complex analytical environments. We hope that the analysis of the achieved performance of the sensors can indicate the recognition of potential application in clinical, pharmaceutical, and bioanalytical practice, but also point to the directions of future research.

2. Classes of Nanomaterials for Electrochemical Sensing

2.1. Carbon-Based Materials

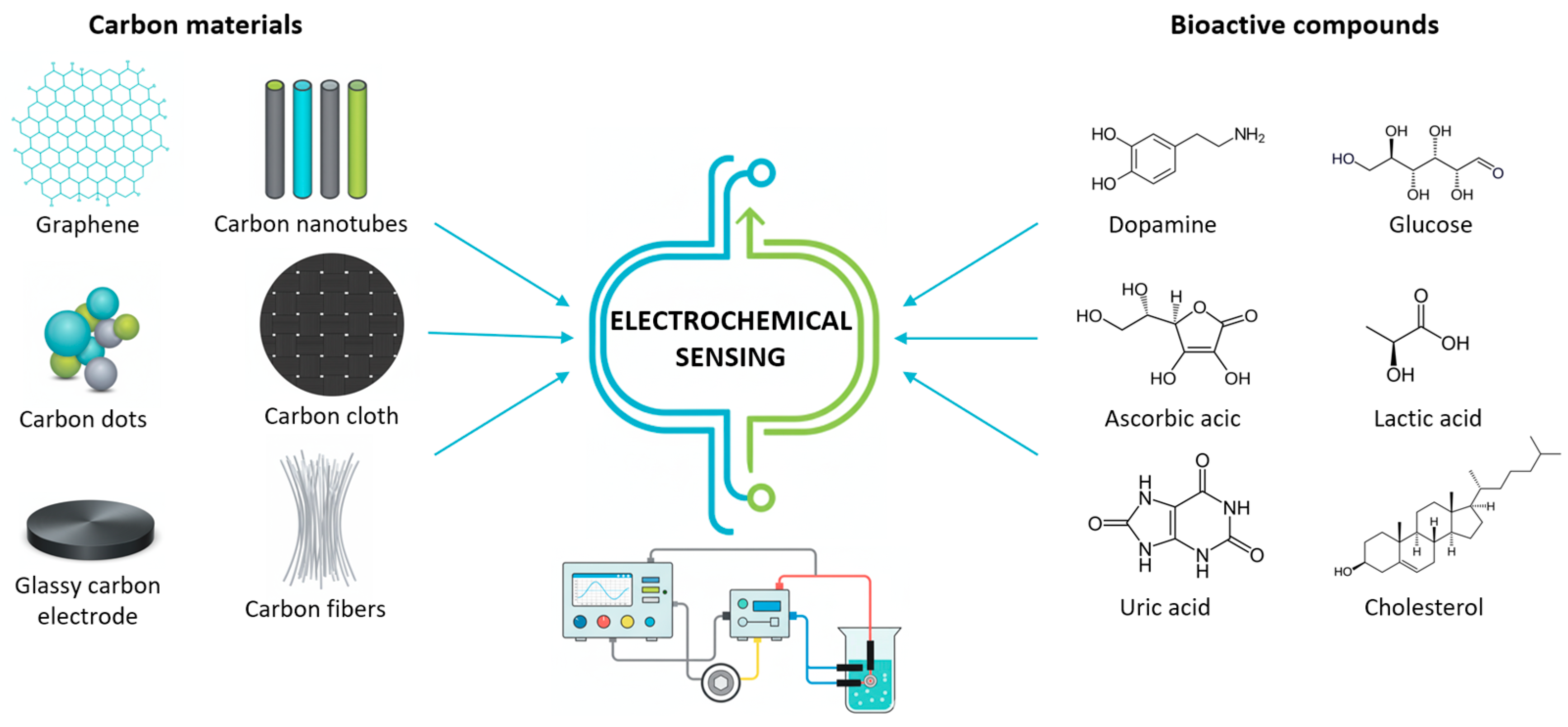

In recent times, several types of different carbon nanomaterials (shown in Figure 3) have been developed with favorable properties for use in the production/modification of electrochemical sensors.

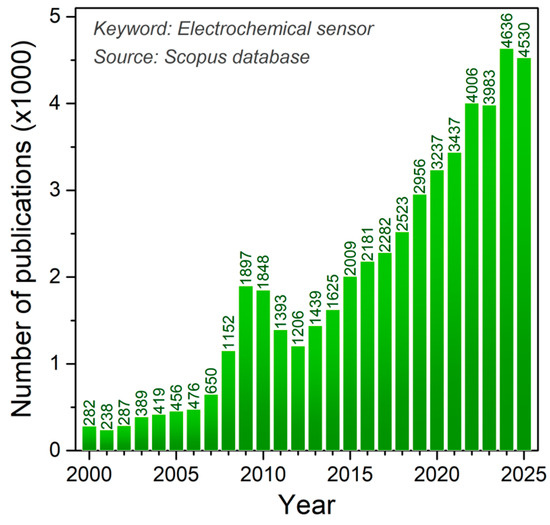

Figure 3.

Schematic expression of various carbon materials used for electrochemical sensing of bioactive compounds.

First of all, carbon-based materials are characterized by a significantly large specific surface, which increases the sensitivity of the sensor to many biologically active small and large molecules. Catalytic properties and efficient electron transfer enable a fast and more selective sensor response, with a pronounced signal. Due to their stability, biocompatibility, and functionalization options that improve selectivity, carbon-based materials are suitable for various sensor constructions in biological samples and in vitro systems, providing a significant advantage over many other materials [21,22]. Table 2 summarizes the main advantages and limitations of these materials used as electrode modifiers in electrochemical sensing.

Table 2.

Comparison of carbon-based nanomaterials applied in electrochemical sensors.

In the last few years, the aforementioned carbon materials have been used in the modification of electrodes, dominantly in combination with each other or with other materials of a different nature in a physically homogeneous structure, making typical composite electrodes. Various low-cost simple domestic manufactured electrodes of different constructions were prepared and used for the amperometric determination of dopamine directly, and a biomarker IL-6 with an enzyme-tagged ELISA format, indirectly. As these carbon paste electrode (CPE) chips were not able to show a clear electrochemical signal for low abundance concentrations of 100 pg/mL, the authors nevertheless suggested its use for the purposes of clinical YES/NO diagnostics [23]. In the construction of these sensors with a CPE substrate, paraffin stabilizes the electrochemical signal, while graphite provides abundant electrocatalytic sites, enhancing the redox current. Hsieh et al. modified GCE with a biocomposite consisting of two carbon materials, graphene and multiwalled carbon nanotube (GR-MWCNT), for the simultaneous detection of ascorbic acid (AA), dopamine (DA), and uric acid (UA) by using differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) with sensitivities of 0.076, 1.38, and 0.181 μA μM–1 and detection limits (LODs) of 6.71, 0.58, and 7.30 μM, respectively [24].

The combination of carbon materials in this study clearly represents an advancement in the design of electrochemical sensors for the simultaneous detection of multiple bioactive analytes. Graphene contributes a large surface area and planar conductive channels, while MWCNTs act as “corridors” for electron transfer and provide additional interaction sites. The synergy between graphene and MWCNTs significantly enhances the sensitivity and selectivity for the detection of the three bioactive compounds (AA, DA, and UA), which often have overlapping signals, while also reducing electron transfer resistance and expanding the functional advantages of the sensor. The sensor was successfully tested in serum and urine samples. Reanpang et al. reported a highly sensitive flow injection amperometric sensor-based nanocomposite, also from two carbon materials—carbon black (CB) and graphene oxide (GO) modification of scrin-printed carbon electrode. CB/GO/SPCE possessed a linear range of 0.05 to 2000 µM of uric acid with a limit of detection (LOD) of 0.01 µM. The sensor was successfully tested and the results were comparable to the hospital laboratory [25]. In the proposed sensor, carbon black provides high surface area and sp2 defect sites, while graphene oxide adds functional groups for uric acid interaction. Their synergy offers an efficient, cost-effective strategy for sensing small electroactive bioactive molecules. Graphene quantum dots (GQDs), carbon quantum dots (CQDs), and carbon nanodots (CNDs) were used in the work of Mileina and other authors [26] as electrode modifiers for the determination of the opium alkaloid codeine in saliva, urine, and in soft drinks with a small sample preparation protocol. The best results were obtained by electrodes modified with GQDs, with a LOD and LOQ (limit of quantification) of 0.21 and 0.73 µM, respectively. GQDs enhance sensor signals for bioactive molecules like alkaloids, vitamins, and hormones more effectively than graphene or carbon nanotubes due to their high density of redox-active sites. These examples show that, even without additional materials, carbon materials can enable high sensitivity and selectivity in the detection of bioactive compounds. But, as demonstrated by Alsharabi et al. [27], reduced graphene oxide as a material with excellent conductivity was mixed with a material of a different nature—Ni foam (rGO/NiF)—as a substrate with high porosity, to produce a nanocomposite capable of adopting GLDH enzyme molecules for targeted brain neurotransmitter glutamate. This sensor exhibited high sensitivity with a LOD of about 0.1 µM [27]. rGO, which possesses higher conductivity than GO and retains sufficient functional groups, and also prevents the oxidation and passivation of the Ni foam (3D substrate). Furthermore, rGO enhances glutamate chemisorption, enabling the sensitive detection of this compound. Zhang et al. obtained carbide coordination polymer with a 2D network structure from the carbonization of a co-polymer based on 4,4′-bis(1H-benzo[d]imidazol-1-yl)-1,1′-biphenyl (BMB) [28]. A composite electrode modifier, C-CoCP@GO, was then prepared by binding this material with GO and successfully applying it to determine polyphenolic isomers hydroquinone (HQ) and catechol (CC) in a wide liner range of 3–600 μM and 3–1750 μM, respectively, and LODs of 0.46 μM and 0.27 μM. N-doped porous carbon material, obtained in this way, exhibits enhanced electrocatalytic activity and creates defect sites with a high affinity for the phenolic/hydroxyl groups of the analytes. Its high porosity facilitates mass transport. All three polyphenolic isomers produce well-resolved peaks, resulting in excellent selectivity. Singh et al. employed photolithographically patterned gold microelectrode arrays on a glass substrate as a platform for low-temperature in situ synthesis of carbon nanotubes [29]. The resulting CNT architectures exhibited an excellent enzyme immobilization capability. Glucose oxidase (GOx) was homogeneously distributed within a poly(paraphenylenediamine) matrix deposited on the CNTs/Au MEA surface. The GOx/poly(p-PDA)/CNTs/Au MEA biosensing interface enabled the impedimetric quantification of glucose within the 0.2–27.5 µM range, delivering a sensitivity of 168.03 kΩ−1 M−1 and a detection limit of 0.2 ± 0.0014 µM.

Bearing in mind previous carbon-based electrode modifiers, it can be concluded that, for high-sensitivity applications requiring fast electron transfer, such as biomolecule or glucose detection, rGO + CNT composites or pure graphene are preferred due to their excellent conductivity and large surface area. Carbon black can be ideal for low-cost, mass-producible sensors like disposable or screening devices. For biosensors that require functionalization for enzyme, antigen, or DNA immobilization, GQDs or CQDs are particularly advantageous thanks to their abundant edges and functional groups. Hollow nanorods offer enhanced analyte transport for specialized porous or enzyme sensors, though their synthesis is more complex.

2.2. Metal and Metal Oxide Nanoparticles

Metal and metal oxide nanoparticles are extremely important in the development of electrochemical sensors due to their unique physicochemical properties that significantly improve sensor performance—especially when used for the detection of biologically active substances (Table 3).

Gold nanoparticles lead to an improvement in the sensor’s conductivity and act catalytically, and it is significant that AuNPs represent a biocompatible material. The uniform distribution of AuNPs directly on the SPE leads to the development of a DPV sensor that can rapidly and sensitively determine nanomolar amounts of mycotoxin Fumonisin B1 (FB1) is naturally present in meat food [30]. The functionalization of gold nanoparticles is easy, especially with thiol groups of biomolecules (as in DNA and enzymes), which enables the stable immobilization in immunosensors. Thiol groups are prone to binding easily to gold substrates because of the strong Au–S interaction, which has both a covalent and partial coordination character, making it thermodynamically favorable, selective, and durable, and not easily displaced by other species. Often, gold nanoparticles can functionalize carbon materials, like in the work of Rashid et al. [31], where SPE is modified with AuNP-functionalized rGO and successfully used for the sensitive determination of pyocyanin, a biomarker of P. aeruginosa infections, in samples of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), human saliva, and urine with LODs of 0.27 μM, 1.34 μM, and 2.3 μM, respectively. Musa et al. [32] modified SPE with complex composite material where rGO-AuNP serves as a dispersant for the carbon nanotubes to produce an electrochemical sensor for the natural estrogen hormone estradiol. In addition to the low detection limit of 3 nM, the advantages of this sensor were the green synthesis of AuNPs and significantly improved sensor performances, like a reproducibility of 2.58% and a recovery of 92%, for the analysis of drinking water samples. A C-reactive protein impedimetric sensor developed by Grammoustianou et al. was constructed on a gold surface covered with a neutravidin layer, and immobilized with the biotin-CRP antibody [33]. This proposed sensor for the inflammation biomarker represented the real-time, fast, specific, sensitive, and label-free detection of CRP in the interstitial fluid that can be accessed with minimally invasive microneedle arrays. The sensor detected CRP down to 0.7 μg/mL in buffer and 0.8 μg/mL in ISF-like solution, with a linear response up to 10 μg/mL, using only 5 μL of sample and a 100 s response time.

Silver nanoparticles were known due to their antimicrobial properties, but in electrochemical sensors, AgNPs also show strong redox activity because the Ag+ ion acts as an electrochemical signal amplifier. These nanoparticles are very suitable for the construction of non-enzymatic electrodes and, in combination with carbon multiwall nanotubes applied to GCE, showed a fast and stable response to H2O2, with a wide linear range of 1 to 1000 μM and an LOD of 0.38 μM. H2O2 is a side product of oxidase metabolism and a marker of oxidative stress; hence, it was determined with the described method in spiked human blood serum samples [34]. The estriol hormone molecule was determined based on its oxidation at +0.45 V, by the DPV method on rGO-AgNPs modified GCE. An LOD of 21.0 nmol L−1 was achieved and the sensor was successfully applied in human urine samples [35]. Barreto et al. combined reduced graphene oxide with copper nanoparticles to create a composite sensing platform for quantifying estriol at micromolar levels and a neutral pH, ideal for analyzing water samples after bioremediation [36].

Metal oxides are semiconductors and isolators, with a relatively passive and more ordered (crystalline) structure, which significantly slows down the flow of electrons through the electrode. These compounds generally have lower catalytic properties compared to elementary metal nanoparticles, but they still possess a number of advantages compared to pure metals. Metal oxides are often used in combination with carbon materials to improve the conductivity of the electrode modifier material as a whole. Selected polyphenoles (sinapic acid, syringic acid, and rutin) were determined in wine samples by using low-cost Fe3O4 NPs modified CPE, with good catalytic properties, other sensor performances, and LODs at 10−7 M levels [37]. The results were comparable with gold SPE and the determination of syringic acid was for the first time reported in this work, bearing in mind electrochemical sensors. A combination of iron and tungsten was also interesting for studying. By increasing the tungsten concentration in iron tungstate in our laboratory, we produced a selective sensor for the determination of natural alkaloid morphine [38], which demonstrated excellent repeatability. As TiO2 is known as a chemically stable and photocatalytic material, often used as receptor or enzyme carrier in electrodes, in the work of Guerrero and et al. [39], it was combined with MWCNT, in one case using Prussian blue (PB) to improve electrocatalysis, and in the other, TiO2/MWCNT was functionalized with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) to obtain electrodes for H2O2 quantification. TiO2 was found to significantly improve the stability of the electrode, demonstrating a highly operational electrochemical sensor that also represents an excellent matrix for enzyme immobilization. ZnO nanoparticles have semiconducting properties and are biocompatible, so, with appropriate functionalization to avoid agglomeration and improve chemical stability, these nanoparticles can provide an excellent electrode modifier, as is the case in the work of Saritha et al. [40]. To prepare the working electrode, Zinc oxide nanoparticles were dispersed uniformly into the carbon nanosheet and embedded in CPE to determine one of the most biologically active flavanols, quercetin, with a superior electrochemical response (the LOD and LOQ were 0.04 and 0.13 µmol L−1, respectively). A hybrid material from NiO in the cubic and ZnO in the hexagonal phase, formed in clusters, exhibited highly catalytic properties in the oxidation of brain neurotransmitter dopamine in the work of Naz and coauthors [41]. Despite its favorable catalytic properties and chemical stability, it often requires additional functionalization to enhance its relatively low selectivity. It is also significant that this composite can be obtained in the fruit juice environment, potentially for further diverse applications. However, Mutić and colleagues [42] managed to achieve a selective and sensitive analysis of gallic acid in different plant samples at only NiO support at CPE. In contrast to other oxides, such as ZnO, SnO2, and TiO2, NiO is a p-type semiconductor, which makes it suitable for the formation of p–n heterojunctions. Bi2O3 is a promising material for electrochemical sensors, but its performance is significantly enhanced when combined with other materials, like with SWCNT in modified CPE, where it was used for the submicromolar quantification of neolignane honokiol [43]. Although slightly more toxic than environmentally friendly Bi2O3, bismuth oxychloride (BiOCl), owing to its unique tetragonal layered structure, is particularly suited for photoelectrochemical sensing applications. In our study [44], however, it was employed to modify a carbon paste electrode for the detection of the alkaloid quinine (QN) in beverage samples, yielding results comparable to those obtained by the UV–Vis spectrophotometric method. Despite not being a typical choice due to its insulating nature, MgO nanoparticles were incorporated into a carbon paste by Chetankumar et al., resulting in an efficient electrode for the quantitative analysis of essential purine bases guanine (GA), adenine (AD), and neurotransmitter and hormone epinephrine (EP) [45]. However, the properties of CeO2 nanorods, such as the easy electron transfer between Ce3+ and Ce4+, the advantages of oxygen vacancies, the exceptional stability under high temperatures and various chemical conditions, and their biocompatibility, are the main reasons why these nanoparticles are desirable for the modification of electrochemical sensors. Being incorporated in graphite sensor CeO2 proved them to be extremely sensitive to low concentrations of 17β-estradiol and diethylstilbestrol (DES) (natural and synthetic estrogen) in a working range of 10–100 nM [46]. When CeO2 is combined with other materials, a synergistic effect can be achieved and the performance of electrochemical sensors for bioactive substances can be further improved. Shang et al. [47] synthesized ZnO-CeO2 hollow nanospheres, where CeO2 was used to suppress ZnO agglomeration. The proposed ZnO-CeO2/GCE exhibited a highly sensitive electrochemical response to dopamine and uric acid in a wide liner range of 5–800 μM for DA, and 10–1000 μM for UA and low LOD.

2.3. Two-Dimensional Noncarbon Materials

Two-dimensional noncarbon materials play an important role in the development of new electrochemical sensors for different kinds of analytes and their application is expanding into the field of bioactive compounds as well (Table 3). These materials usually include transition metal dichalcogenides (MX2), among which MoS2 in its nanoscale form is the most commonly used in electrochemical sensors. As an n-type semiconductor, MoS2 exhibits relatively low electrical conductivity, and a particular issue is its gradual degradation upon exposure to air. Edge sites in MoS2 facilitate electron transfer by providing metallic electronic states, high densities of unsaturated atoms for analyte adsorption, lower activation energy for redox reactions, and increased charge transfer kinetics through enhanced local electric fields and Mo redox cycling. However, the functionalization of this 2D material with metal nanoparticles or metal oxides can stabilize the material and make it suitable for the detection of bioactive compounds. In the work of Mahanta et al., MoS2 was successfully functionalized with rGO and doped with Ag NPs to design an ultrasensitive electrochemical sensor for the simultaneous determination of dopamine, ascorbic acid, and uric acid. This electrode material with MoS2 demonstrated extremely improved stability by 500 repetitive cycles CV [48]. Soltani-Nejad et al. created an effective sensing platform for the determination ascorbic acid in the presence of vitamin B6 by modifying CPE with MoS2 nanosheets and ionic liquid, which promote election transfer [49]. The sensor possesses a wide working range of 1.0 to 1000.0 μM and an LOD of 0.2 μM.

Tungsten disulfide (WS2) has proven to be an excellent platform for developing electrochemical sensors due to its outstanding properties: a large surface area and active edges that enable the efficient adsorption and redox reactions of bioactive molecules, chemical stability, biocompatibility, and ease of combination with carbon nanomaterials or polymers, which enhances conductivity and sensor selectivity. Zribi et al. modified SPE with WS2 deposited on CNTs by atomic layer deposition (ALD), forming a CNTs-WS2 core–shell heterostructure, to obtain a superior electrochemical sensor for the quantification of vitamin B2 with an LOD of 1.24 µM [50]. Singh and coauthors also modified SPE with hydrothermally synthesized WS2 nanosheets in combination with chitosan (CS) biopolymer applied for nonenzymatic histamine determination [51]. This inorganic–organic composite was able to perform measurements within a linear coverage of 1–100 μM, with a limit of detection of 0.0844 μM and a sensitivity of 1.44 × 10−4 mA/μM cm2. WS2/CS/SPE was employed for the accurate detection of the histamine levels in packed food items like fermented food samples (cheese, tomato sauce, tomato ketchup, and soy sauce).

MXenes (with the general formula Mn+1XnTx, where M is an early transition metal, X is C or N, Tx represents surface terminations) have been extensively studied in recent years, and an increasing number of electrochemical sensors are being developed based on them, owing to their high metal-like conductivity, hydrophilicity, and diverse surface chemistry, which led to excellent selectivity. However, challenges related to their stability, such as partial oxidation, loss of surface functional groups, and reduced water stability, must be overcome to fully exploit their potential when these materials are used in the sensing of biocompounds. MXenes are often used in the construction of enzymatic sensors, but are also extremely suitable for non-enzymatic sensors, above all, glucose sensors, because they promote electron transfer and have a lot of active surface sites for glucose oxidation. Co, Mn, or Ni can be introduced in this material to prevent agglomeration, which greatly improves the performances of the sensor. Feng and coauthors specifically exploited this effect by incorporating CuxO into the MXene material. These researchers prepared a Ti3C2Tx MXene/CuxO-based electrochemical glucose sensor with an extremely large working range of 1 µM to 4.655 mM and a low LOD of 0.065 µM. Furthermore, this composite used as an electrode modifier was resistant to the oxidative interference of other, stronger-nature antioxidants, such as ascorbic acid, dopamine, and uric acid [52]. Also interesting was the approach of Zhang et al., which combined multilayer and single-layer Ti3C2Tx MXene (M−MXene and S−MXene) with holey graphene (HL) to obtain 3D porous networks for the quantitation of dopamine. S-MXene showed itself to be favorable compared to M−MXene, bearing in mind conductivity, surface hydrophilicity, and enhanced biofouling resistance. It also possessed better analytical performances for sensing dopamine in complex fluids [53].

2.4. Polymer-Based Materials and Crystal Frameworks

Polymers offer numerous advantages that significantly improve the selectivity, stability, and sensitivity of electrochemical sensors, which are essential for the detection of bioactive compounds in complex sample matrices. Different types of polymers can be utilized, each contributing uniquely to sensor performance. Some of them exhibit biocompatibility, such as chitosan and polydopamine, and these polymers are suitable for direct application in biological sample analysis (quercetin sensor [54], guanine sensor [55], and others [56]). Typically, polymers form porous, three-dimensional films on the electrode surface, increasing the active surface area available for analyte interaction. Polymer coatings also protect the electrode from chemical degradation, enhancing sensor stability and enabling repeated use. Certain polymers, including polypyrrole (PPy), polyaniline (PANI), and poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT), are electroconductive, facilitating efficient electron transfer. Polymers can be readily functionalized with various materials such as carbon-based nanomaterials and metal and metal oxide nanoparticles, like in the work of Alahmadi et al. [57]. This work describes the application of an indium tin oxide (ITO) electrode modified with MoO3 nanoparticles and electrochemically coated with polypyrrole in order to improve conductivity. Electrochemical polymerization allows direct deposition of the polymer layer from monomer pyrrole onto this electrode. The proposed sensor was employed for the square wave voltammetry (SWV) determination of dopamine at nanomolar concentrations, and it demonstrated a limit of detection of 2.2 nmol L−1. A polymeric PVC membrane was used to create matrices activated with [Cu2tpmc](ClO4)4 (N,N′,N″,N‴-tetrakis(2-pyridylmethyl)-1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane (tpmc)) and the final modification of glassy carbon and graphite rod electrodes [58]. The electrodes thus enabled the detection of gallic acid in nitric acid as a supporting electrolyte at pH 2. Both electrodes showed linear dependence in the concentration range from 2.5 × 10−7 to 1.0 × 10−4 M, with a slightly lower LOD of 1.48 × 10−7 M obtained in the GC electrode, in contrast to the graphite rod electrode, where this value was 4.6 × 10−6 M. When determining the antioxidant capacity of red wine samples, both electrodes showed excellent agreement of results. Very little influence of interfering substances was observed in either case. A work of Tesfaye and coauthors [59] developed a low-cost and efficient vitamin B2 sensor based on poly (glutamic acid) and ZnO NPs applied for the determination of this vitamin in non-alcoholic beverage and milk samples. The sensor possessed a high sensitivity of 21.53 µA/µM and worked in a range of low concentration of 0.005–10 µM with an LOD of 0.0007 ± 0.00001 µM. The study of Sarkar and coauthors represents a good example of modern electrochemical biosensing for a hormone/biomarker cortisol: it demonstrates that it is possible to obtain a sensitive, selective, and relatively robust sensor based on graphene and polyaniline (G-PANI ink), with antibody immobilization, which works even in serum. Cortisol detection was performed electrochemically using cyclic voltammetry (CV), DPV, chronoamperometry, and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), with a working dynamic range of 100 ng/mL to 100 µg/mL of cortisol and an LOD of approximately 0.0577 µg/mL [60].

Nowadays, molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) are among the most widely used polymers for electrode surface modification in electrochemical sensors due to their high selectivity or even their specificity towards target biological molecules. Their ability to recognize target molecules at the molecular level makes them particularly well-suited for the detection of low concentrations of bioactive compounds in complex sample matrices. Jiang et al. used imprinting technology to develop an electrochemical sensor for the detection of elemene, a natural bioactive compound with various pharmacological activities [61]. The sensor exhibited two linear ranges of 10 μM to 0.1 mM and 50 nM to 10 μM, with an LOD of 2.7 nM of elemene. The potential for the integration of this analytical platform into portable and miniaturized devices for real-word applications was especially emphasized. Hurkul et al. [62] fabricated MIP from N-methacryloyl-L-aspartic acid as a monomer and applied it for the detection of picomolar levels of rutin, a natural flavonoid with strong antioxidant properties. This sensor was operating in a range of 1–10 pM and with an exceptional LOD of 0.269 pM.

Nunes da Silva and Pereira used a combination of MIP and carbon black as an electrode modifier sensitive to 17β-estradiol, the primary female sex hormone from the estrogen group [63], while Spychalska and coauthors detected the same hormone on an electrochemical platform without using MIP and made from immobilized horseradish peroxidase (HRP) covered with conducting polymer poly(4,7-bis(5-(3,4-ethylenedioxy thiophene)thiophen-2-yl)benzothiadiazole) [62]. HPR enzyme enabled the very sensitive and selective determination of E2 in a broad linear range of 0.1 to 200 mM, with a detection limit of 105 nM.

Graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) is a widely used electrode modifier that can be synthesized relatively easily and inexpensively, primarily via the thermal polymerization of low-cost nitrogen-rich precursors such as urea, melamine, and dicyandiamide. It is a two-dimensional, semiconducting polymeric material with a graphene-like structure, composed mostly of carbon and nitrogen atoms. In addition to its favorable electrical (and photoelectrical) properties, it exhibits high chemical stability and biocompatibility, and can be easily combined with other materials. Singh and coauthors [64] used a g-C3N4 network decorated with graphene-coated Ag NPs for sensing estradiol (also known as 17β-estradiol) with a low LOD of 0.002 μM. The advantage of this sensor was its high stability of fabricated electrodes which retained 91% of the signal for 21 days. Porosus g-C3N4 nanosheets and graphene oxide turned out to be a favorable combination for the simultaneous quantification of ascorbic acid, dopamine, and uric acid, tested in spiked urine samples [65]. These three bioactive compounds showed well-separated and defined peaks at the proposed electrochemical sensor around 0.15, 0.34, and 0.46 V for AA, DA, and UA, respectively. Özkahraman et al. presented an impedimetric sensor for the determination of glucose due to the Black Phosphorus/Graphitic Carbon Nitride (BP/g-CN) heterostructure designed to exploit interactions between phosphorus and nitrogen, enhancing its electrochemical activity for glucose oxidation [66]. In comparison with pure g-CN, the heterostructure exhibits a considerably larger electrochemical surface area and almost halves the charge transfer resistance, resulting in an excellent glucose sensitivity of 1.1 µA·mM−1·cm−2 under physiological pH conditions. The BP-gCN sensor is incorporated into a wearable skin patch with microfluidics and an NFC chip for real-time glucose monitoring in sweat.

Covalent organic frameworks (COFs) and metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) are porous crystalline materials with high surface activity, in which organic structural units are connected by covalent bonds either to each other (in COFs) or to metal ions (in MOFs). The advantages of these frameworks lie in the ability to design and modify their structures, which enables the selective detection of various bio-analytes. Additionally, COFs and MOFs can be integrated with other materials into hybrid systems with enhanced performance. These frameworks are mainly used for gas storage but also possess sensing capabilities. However, their poor water stability in some cases frequently limits their practical applications. Zhou et al. [67] reported an electrochemical sensor based on a COF-modified carbon fiber microelectrode for the detection of dopamine, a biomarker relevant to Parkinson’s disease diagnostics. The real-time analysis of dopamine directly in the mouse brain was made possible due to the antibiofouling and anti-chemical fouling properties of the COF electrode material, which inhibited dopamine polymerization at the electrode surface and enabled the sensitive detection of low concentrations of this compound in real samples. Dey and coauthors [68] prepared a sensor based on manganese cobalt (2-methylimodazole)–metal–organic frameworks, also on carbon nanofibers, as an efficient and sable electrochemical platform for the determination of histamine in bananas and for testing fish freshness. A sensitive sensor exhibited a wide working range from 10 to 1500 µM, and an LOD of 89.6 nM. Cu-MOF was used as a CPE modifier for the determination of quercetin in apple and grape juice in the study by Özyurt [69]. A significant enhancement of the electrochemical signal was observed, with the response being approximately three times higher than that obtained with the bare electrode.

2.5. Thermolysis-Derived Electrode Modifiers

Thermal approaches such as calcination (in the presence of air) and pyrolysis (in the absence of oxygen) are becoming increasingly important strategies for the creation of new nanostructured materials, offering significant advantages in the fabrication of advanced materials in the sensing of bioactive compounds. Depending on precursors, these processes can yield a wide variety of electrode modifiers—ranging from porous carbon structures, to those doped with non-metal heteroatoms, or incorporating metal or metal oxide nanoparticles (Table 3).

It is well-known that certain polymers, such as phenol-formaldehyde resins, can be transformed through specialized processes into exceptional electrode materials such as glassy carbon. In our laboratory, we produced efficient and conductive electrode modifier (SynFe + Ti/UF-TP) for the determination of caffeic acid by the thermolysis of two metal compounds (Fe(NO3)3·9H2O and nano-TiO2) synthesized in situ with urea formaldehyde resin (UF) [70]. Highly porous carbon-based material was prepared by the thermal decomposition of Novolac phenol-formaldehyde resin and cerium nitrate or cobalt nitrate with an additional small amount of carbon nanotubes, both giving an exceptional electrochemical response to prominent bioactive compounds [71,72]. A low content of CeO2 nanoparticles (no more than 2%) in carbon material obtained after thermolysis was decorated with multi-wall carbon nanotubes to produce electrode material sensitive to dopamine and selective to other bioactive compounds (vitamins C, B2 and B6, uric acid). On the other hand, the same group of authors reported an electrode modifier, obtained by thermal decomposition of the same Novolac resins with cobalt salt. Carbon-based material with embedded Co3O4 and mixed with a small amount of single-wall nanotubes gave an excellent electrochemical sensor for a “universal” antioxidant, α-lipoic acid (LA), soluble in water and fat [71]. LA was determined in a working range of 2 to 100 µM in dietary supplements [72].

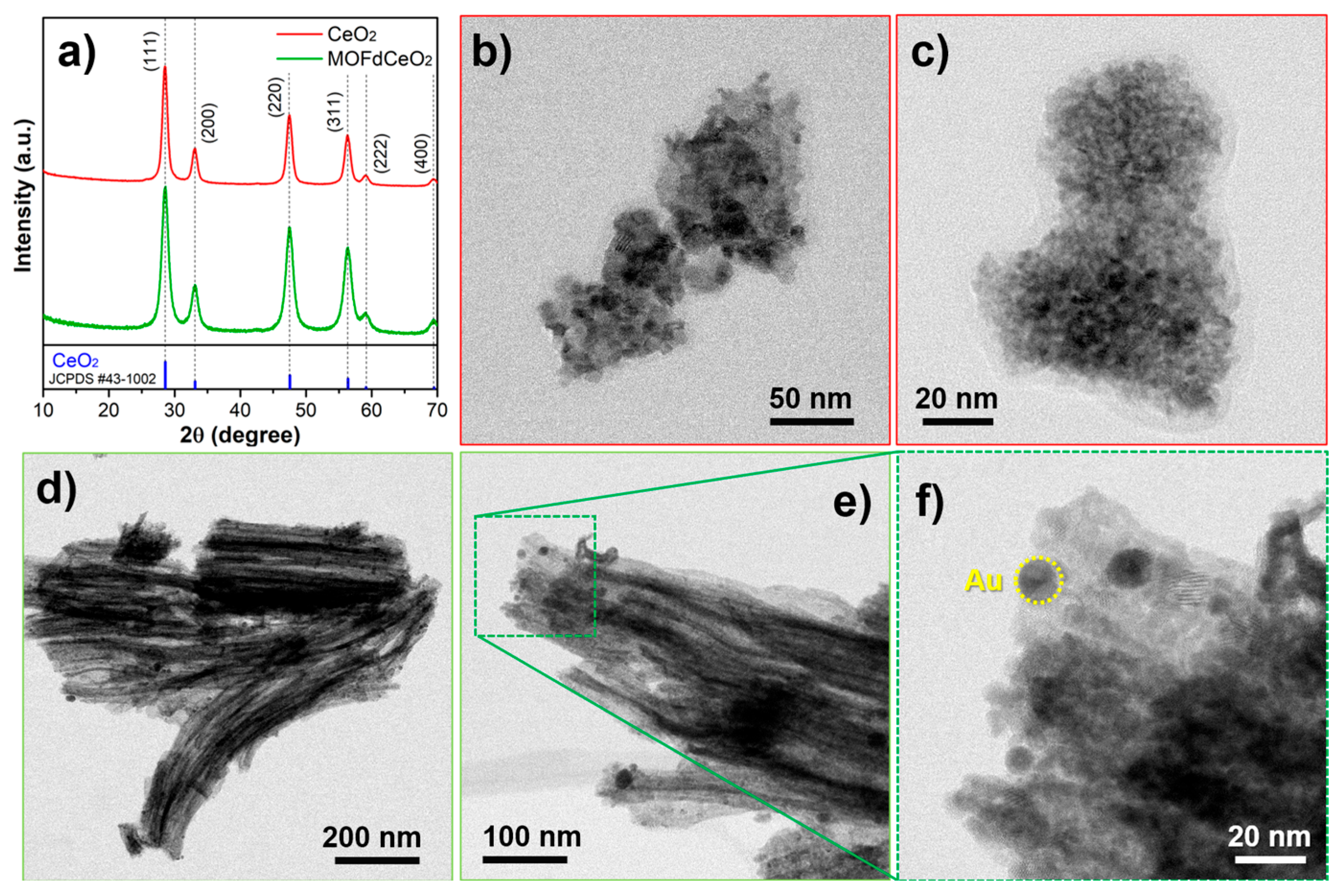

MOFs are highly attractive precursors for the development of efficient electrode modifiers due to their unique structure, composition, and excellent sensing properties. Through the thermolytic decomposition of metal clusters coordinated with organic ligands, it is possible to obtain highly porous, crystalline materials with large specific surface areas and well-defined active sites. During pyrolysis, the organic components carbonize into a conductive carbon matrix, which can also incorporate heteroatoms such as nitrogen or sulfur, further enhancing the material’s electronic and catalytic properties. The regular arrangement of metal centers in the original MOF structure ensures the uniform dispersion of metal or metal oxide nanoparticles within the carbon framework. Additionally, the accessibility of gases during thermal treatment helps suppress nanoparticle agglomeration. In the case of calcination, MOFs can yield hierarchical nanostructures of metal oxides, making them highly suitable for the non-enzymatic electrochemical sensing of bioactive compounds. Zhao et al. [73] synthesized a core–shell CuO/C material by the calcination at 400 °C, where amorphous carbon uniformly encapsulated CuO nanoparticles. The resulting structure featured an increased content of oxygen vacancies, enhancing its electrochemical activity and making it highly sensitive to glucose detection. Oxygen vacancies in CeO2 facilitate electron transfer by creating Ce3+/Ce4+ redox centers, introducing defect electronic states, enhancing analyte adsorption, and lowering the energy barrier for interfacial charge transfer. This glucose sensor also exhibited a remarkably wide linear range, from 5.0 μM to 25.325 mM, with an LOD of 1 μM. CeO2 nanoparticles, among MOF-derived metal oxides, are particularly prominent in the detection of biologically active compounds due to their enzyme-like behavior, which has led to their designation as “nano-peroxidase”. CeO2 NPs also show catalytic activity toward other biologically active natural substances. Ge et al. [74] developed a two-dimensional sensing network by combining MOF-derived CeO2 (via pyrolysis) with siloxane and deamination dopamine in micromolar levels. Siloxene was found to be a more suitable composite electrode material, in this case, than g-C3N4, owing to its basal plane oxygen and hydroxyl groups in the structure.

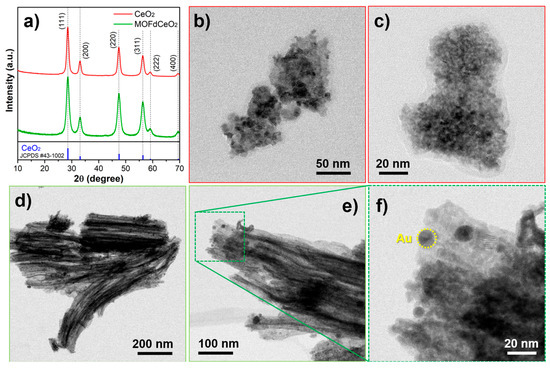

The same compound was detected using a sensor based on an electrode modifier, which was prepared by pyrolyzing ZIF-67 at 350 °C, followed by the hydrothermal incorporation of CeO2 into the resulting carbon/Co3O4 skeleton [75]. By the modification of GCE, dopamine was determined in a range of 0.13–60 μM with an LOD of 0.13 μM. In our laboratory, CeO2 nanoparticles were synthesized from a CeBTC MOF precursor via calcination at 400 °C for 4 h. The resulting nanoceria exhibited an urchin-like morphology, which offers superior catalytic performance compared to more commonly observed CeO2 morphologies, owing to its highly dispersed structure and abundant oxygen vacancies. In the composite decorated with gold nanospheres, this electrode modifier was capable of detecting uric acid in the ranges of 0.05–1 μM and 1–50 μM, with an LOD of 0.011 μM [76] (Figure 4). Since uric acid can help protect milk from rapid microbiological spoilage, the sensor was successfully applied for the analysis of milk samples following a brief sample preparation procedure. The same MOF-derived nanoceria was combined with g-C3N4 to fabricate a guanine sensor by incorporating the resulting bicomposite into a carbon paste electrode [77]. Interestingly, nanoceria was the dominant component in this composite, and the sensor exhibited a diffusion-controlled response to guanine-a behavior that is rarely observed with modified or carbon-based electrodes, according to the available literature. This and related studies in recent periods demonstrate the strong potential of using MOF-derived materials to produce metal oxide nanoparticles and metal/carbon frameworks as a favorable and efficient sensing platform in the quantification of bioactive compounds.

Figure 4.

(a) XRPD diffractograms of solvothermal-prepared CeO2 and MOFdCeO2. Standard diffraction pattern of CeO2 JCPDS #43-1002 was given as a reference; (b–c) TEM micrographs of solvothermal prepared CeO2; (d–f) TEM micrographs of MOFdCeO2/AuNPs nanocomposite [76].

Table 3.

Comparative analytical performance (LOD, linear range, sensitivity, reproducibility) of nanomaterial-based electrochemical sensors.

Table 3.

Comparative analytical performance (LOD, linear range, sensitivity, reproducibility) of nanomaterial-based electrochemical sensors.

| Synthesis Method | Modified Electrode | Analyte | Method | LOD (μM) | Linear Range (µM) | Sensitivity (μA μM–1) | Reproducibility (%) | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon-based materials | - | graphite powder/paraffin wax paste | DA IL-6 | Amp. | 62.5 75 pg | - | - | - | [23] |

| - | GR-MWCNT/GCE | AA DA UA | DPV | 6.71 0.58 7.30 | 100–1000 5–50 50–500 | 0.076 1.38 0.181 | 1.83 1.92 2.17 | [24] | |

| Chemical oxidation | CB-GO/SPCE | UA | FI-Amp. | 0.01 | 0.05–2000 | 0.0191 | 3.10 | [25] | |

| Thermal decomposition | GQD/SPCE | Codeine | CV/DP | 0.21 | 0.73–12 | - | 3.9 | [26] | |

| Electrochemical exfoliation | GLDH/rGO/NiF | Glutamate | CV/DPV | 0.1 | 5–300 | 4.8 µA/(µM·cm2) | 3 | [27] | |

| Solvothermal | C-CoCP@GO/GCE | HQ CC | DPV | 0.46 0.27 | 3–600 3–1750 | - | - 2.3 | [28] | |

| - | CNTs/Au MEA | Glucose | EIS | 0.2 | 0.2–27.5 | 168.03 kΩ−1 M−1 | 1.28 | [29] | |

| Metal and metal oxide nanoparticles | - | AuNPs/SPE | B1 | DPV | 0.08 ng L−1 | 1 ng L−1–1 mg L−1 | - | 3.8 | [30] |

| - | AuNPs/rGO/SPE | Pyocyanin | DPV | 0.27 (PBS) | 1–100 | - | - | [31] | |

| Bioreduction | rGO-AuNPs/CNT/SPE | Estradiol | DPV | 0.003 | 0.05–1.0 | - | 5.3 | [32] | |

| Surface functionalization | Au-surface | CRP | EIS | 0.7 Μg mL−1 | 0.7–10 Μg mL−1 | - | - | [33] | |

| Two-step chemical synthesis | AgNPs-MWCNT/GCE | H2O2 | Amp. | 0.38 | 1–1000 | 2556 µA/(µM·cm2) | 1.2 | [34] | |

| Chemical reduction | rGO-AgNPs/GCE | Estriol | DPV | 0.021 | 0.1–3 | - | 1.5 | [35] | |

| Two-step chemical reduction | GC/rGO-CuNPs | Estriol | DPV | 0.17 | 0.5–3.0 | - | - | [36] | |

| - | CPE/Fe3O4 NPs | sinapic acid syringic acid rutin | DPV | 0.22 0.26 0.08 | 0.9–8 1–9.1 0.3–3 | - | 4.2 3.6 4.6 | [37] | |

| Hydrothermal | FeWO4/CPE | Morphine | SWV | 0.58 | 5–85 | - | 2.56 | [38] | |

| Sol–gel | PB–fCNT/GC HRP–TiO2/fCNT/GC | H2O2 | Chronoamp. | 0.015 0.81 | 0.05–0.8 0.5–7.5 | 163.01 963 | - | [39] | |

| Hydrothermal | ZnO/CNS/MCPE | Quercetin | DPV | 0.04 | 0.166–3.63 | - | 1.76 | [40] | |

| Hydrothermal | NiO/ZnO/GCE | Dopamine | LSV | 0.036 | 0.01–4 | - | 3 | [41] | |

| Co-precipitation | NiO nano/CPE | GA | SWV | 0.04 | 0.2–100, 100–200 | - | 3.1 | [42] | |

| Solution combustion | Bi2O3(n)@SWCNT/CP | Honokiol | SWV | 0.17 | 0.1–50 | 4.96 | [43] | ||

| Hydrothermal | BiOCl/CPE | Quinine | DPV | 0.14 | 10–140 | 1.995 | 5.7 | [44] | |

| Mechanochemical | MgO-MWCNTs-MCPE | Guanine Adenine Epinephrine | CV | 0.92 1.49 0.83 | 10–80 | - | 6.23 7.28 8.32 | [45] | |

| - | CeO2 NPs/CPE | Diethylstilbestrol 17β-estradiol | SWV | 1.3 12.1 | 10–100 100–1200 | - | <4 <3 | [46] | |

| Hard-templating | ZnO-CeO2/GCE | DA UA | DPV | 0.39 0.49 | 5–800 10–1000 | 1122.86 908.53 | 6.2 | [47] | |

| Two-dimensional noncarbonmaterials | Green synthesis | MoS2/rGO/Ag/GCE | AA DA UA | CV | 10.41 0.009 5.94 | 0.75–75 2.5–12.5 0.125–12.5 | - | - | [48] |

| Hydrothermal | MoS2/ILCPE | AA | DPV | 0.2 | 1–1000 | 0.1011 | - | [49] | |

| Atomic layer deposition | CNTs-WS2/SPCE | B2 | DPV | 1.24 | 0–45 | 9 μA μM−1 cm−2 | - | [50] | |

| Hydrothermal | WS2/CS/SPE | Histamine | DPV | 0.0844 | 1–100 | 1.44 × 10–4 mA/μM cm2 | 6.03 | [51] | |

| Etching and stirred electrolysis | Ti3C2Tx MXene/CuxO/CFP | Glucose | Chronoamp. | 0.065 | 0.001–4.655, 5.155–16.155 | 361, 133 mA/μM cm2 | 4% | [52] | |

| Etching | S-MXene/HG/GCE | DA | Chronoamp. | 0.058 | 0.1–255 | - | 2.08 | [53] | |

| Polymer-based materials | Polymerization | Chitosan-modified CMWCNT | Quercetin | - | 0.23 | 1–245.5 245.5–630.5 | - | - | [54] |

| Polymerization | poly(cytosine)/GCE | Guanine | SWV | 0.0061 | 0.1–200 | - | 3.4 | [55] | |

| Solvothermal | Ppy/MoO3/ITO | DA | SWV | 0.0022 | 0.005–0.25 | - | - | [57] | |

| - | [Cu2tpmc](ClO4)4/PVC/GCE | GA | DPV | 0.148 | 0.25–1 5–100 | - | - | [58] | |

| Co-precipitation electropolymerization | poly (glutamic acid)/ZnO NPs/CPE | B2 | SWV | 0.0007 | 0.005–10 | 21.53 | 1.2 | [59] | |

| Polymerization | LIG/G-PANI | Cortisol | CV EIS Chronoamp. | 0.0813 0.0577 0.105 | 0.1–100 0.1–100 0.25–100 | - | 5.85 | [60] | |

| Solution-phase assembly | GN@Ag/g-C3N4/GCE | Estradiol | CV | 0.002 | 0.005–8.0 | 0.07699 | 0.96 | [64] | |

| Thermal polymerization followed by thermal oxidation etching | C3N4–GO/GCE | AA DA UA | DPV | 3.7 0.07 0.43 | 30–3000 0.25–320 2.5–1100 | 0.038 0.46 0.049 μA μM−1 cm−2 | 2.94 1.83 2.65 | [65] | |

| Thermal polycondensation | BP-gCN/SPCE | Glucose | DPV | - | 0.2–1 | 1.1 µA mM−1 cm−2 | - | [66] | |

| In situ growth | COF/cCFE | DA | DPV | 0.0082 | 0–20 | 0.00076 | - | [67] | |

| Electrospinning Stabilization Carbonization | Mn-Co(2-MeIm)MOF@CNF//GCE | Histamine | DPV | 0.0896 | 10–1500 | 107.3 µA mM−1 cm−2 | 3.63 | [68] | |

| Solvothermal | Cu-MOF/CPE | Quercetin | DPV | 0.043 0.008 | 0.01–1 1–70 | - | 0.8743 | [69] | |

| - | SynFe + Ti/UF-TP@CPE | Caffeic acids | DPV | 0.046 | 0.5–100 | - | 2.8–3.4 | [70] | |

| Solid-state thermal decomposition | TPCeO2&MWCNT@CPE | DA | SWV | 0.14 | 0.5–100 | - | - | [71] | |

| Thermolysis-derived modifiers | Thermolysis | TPCo3O4&SWCNT@CPE | α-lipoic acid | SWV | 0.37 | 2–100 | - | - | [72] |

| Thermal decomposition in air | CuO/C-400 °C | Glucose | Amp. | 1.0 | 5.0–25.325 | 244.71 µA mM− 1 cm− 2 | - | [73] | |

| Pyrolisis | CeO2/siloxene/GCE | DA | DPV | 0.292 | 0.292–7.8 | - | - | [74] | |

| Hydrothermal decomposition | CeO2/Co3O4–4 | DA | DPV | 0.13 | 0.13–15 15–60 | 2.632 0.728 µA mM− 1 cm− 2 | - | [75] | |

| Thermolysis | MOFdNC/AuNPs&CPE | UA | SWV | 0.011 | 0.05–1 1–50 | - | 4.4 | [76] | |

| Thermolysis | MOFdCeO2/g-C3N4/CPE | GU | SWV | 0.12 | 0.5–100 | - | 1.6 | [77] |

3. Strategies for the Development of Nanostructures for Electrochemical Sensing

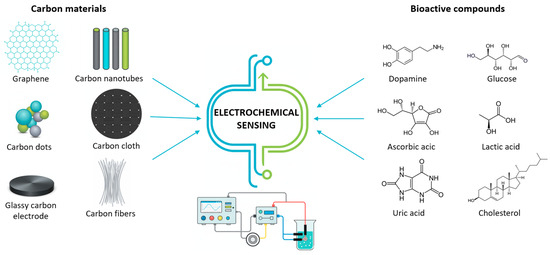

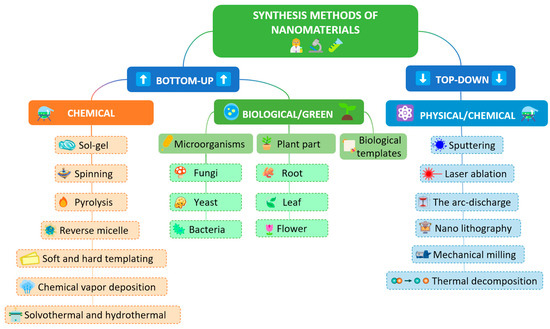

Selectivity and sensitivity play a crucial role in the preparation and potential application of electrochemical sensors. In order to achieve satisfactory results in these parameters, the electrocatalytic properties of the material must be superior. However, it is important to note that the basis of each modification is based on commercially available electrodes, such as glassy carbon electrode (GCE), graphite rod electrode, graphite pencil electrode, screen-printed electrode (SPE), and carbon paste electrode (CPE). These electrodes have their own characteristics that can vary depending on the electrode chosen. Their main advantages are high electrochemical stability, high surface activity, easy modification process (CPEs allow both surface and volume modification), and their availability. The choice of these specific electrodes is based on their unique characteristics that enhance the performance of electrochemical sensors, making them key tools in the analysis of bioactive compounds. The method of preparation of nanomaterials plays the most important role in materials science and nanotechnology. In order to properly select and control the synthesis of nanomaterials, the most important parameters are type, shape, structure, composition, size, etc. The most commonly used synthesis methods to obtain the desired material characteristics are the hydrothermal method, the coprecipitation method, the electrochemical deposition of nanomaterials, the Sol–gel method, spray pyrolysis, microwave-assisted synthesis, thermal decomposition, and synthesis by ultrasonication, as well as syntheses using templates (Figure 5). In addition, classical synthesis methods, or a combination of several of the above methods, are also very often used [78,79,80,81,82].

Figure 5.

The synthesis of nanomaterials using bottom-up and top-down approach.

An excellent example is the synthesis of the COF–AgNP composite and its application for the detection of hydrogen peroxide and rutin and the application of methods for their monitoring in milk samples (hydrogen peroxide) and various fruits (rutin) by Nandhini et al. [83]. After a 72 h treatment at 180 °C in an inert atmosphere, a covalent organic framework was obtained from melamine and terephthalaldehyde, in the form of a sheet-like structure, with weaker crystallinity. On the other hand, in the same solution with the obtained COF, spherical Ag nanoparticles were obtained by simple precipitation, excellently dispersed and incorporated into the initial material. The thus-obtained nanocomposite material showed impressive electroanalytical characteristics with subnanomolar detection limits for both hydrogen peroxide and rutin.

A similar synthesis example was used by Yang et al. to prepare polypyrrole-derived porous carbon nanosheets integrated with Fe3O4 nanoparticles and to construct a sensor for the detection of catechins in commercially available sun-dried Agrocybe aegerita, green tea, and oolong tea beverages [84]. In the first step, a mesoporous nitrogen-doped carbon product was synthesized from a multi-step classical synthesis, with a final thermal treatment at 800 °C for 2 h. The resulting material was mixed with FeCl3·6H2O and treated with stirring for 6 h at 60 °C. The final composite, magnetic nitrogen-doped porous carbon/Fe3O4, was obtained by thermal treatment at 800 °C for 2 h with a heating rate of 5 °C/min. Morphological characterization confirmed the successful synthesis of irregular Fe3O4 nanoparticles with an average particle size of ~70 nm, as well as the porous flake-like morphology of the carbon component. The final sensor also had a subnanomolar detection limit for catechin with successful implementation in real samples. Sulfide-based nanomaterials have recently played a very important role in electrocatalysis and electroanalytical chemistry. Excellent analytical results in the detection of rutin hydrate with a detection limit of 7 nM were obtained with a coral-like material based on nickel manganese cobalt sulfide obtained by two-step hydrothermal synthesis by Ragumoorthy et al. [85]. The formation of a composite with reduced graphene oxide and the modification of the glassy carbon electrode enabled high sensitivity and selectivity of the method in the detection of rutin hydrate in diverse real samples, encompassing environmental fluids (river water, pond water, artificial saliva, and human urine) and consumable products (black tea, red wine, lime, apples, onions, and oranges), requiring minimal sample preparation. In the first step of the synthesis, the nanomaterial was prepared from acetic salts of nickel, manganese, and cobalt, but, for homogeneous nucleation and control of the precipitation process, a urea solution was used. In the second step, a sodium sulfide solution was used as a sulfur source. Hydrothermal treatment at 80 °C for 6 h successfully sulfidized the nanomaterial, and this step facilitated the self-assembly of hierarchical nanostructures, ultimately yielding a coral-like NMC-S morphology.

A recent study by Qi et al. demonstrated a very stealthy approach to the synthesis of high-accessibility Fe single atoms via a directional anchoring strategy and detection of hydrogen peroxide in milk samples [86]. The multi-step synthesis was performed using a hard template to achieve the directional anchoring of Fe single atoms on the inner surface of nitrogen-doped carbon materials (In-Fe SAs/NC) and the outer surface of nitrogen-doped carbon materials (Out-Fe SAs/NC) through four synthesis steps, which included the following processes: a synthesis of PDA-dopamine solution was added to a mixed solution containing ammonia, water, and ethanol, and stirred for 30 h; a synthesis of NC-PDA was pyrolyzed at 400 °C and then at 800 °C under a N2 atmosphere; a synthesis of In-Fe SAs/NC: Fe3O4@C was treated with concentrated HCl to dissolve the Fe3O4 core, leaving behind Fe single atoms anchored on the inner surface of NC; and a synthesis of Out-Fe SAs/NC: PDA nanospheres was coated with a SiO2 shell, then combined with FeCl3 and pyrolyzed. The SiO2 shell was then etched away, leaving Fe single atoms anchored on the outer surface of the NC; the final material showed a very wide working concentration range of 0.002 to 3.2 mM with a detection limit of 0.001 mM. Interestingly, this synthesis achieved a sensor sensitivity of 582.43 µA cm−2 mM−1, which is significantly higher than what can be found in the recent literature. Guo and co-authors prepared a multifunctional material by a simple ultrasound-assisted synthesis method based on mesoporous silica nanoparticles decorated single-wall carbon nanotubes for the detection of gallic acid [87]. The synthesis procedure was based on the ultrasonic treatment of the components in a DMF solution for two hours. The resulting suspension was used to modify a glassy carbon electrode after drying. The developed sensor showed a linear range of 0.03–30 μM, and a limit of detection of 3.806 nM. The satisfactory selectivity of the method was used for practical application in tea samples, which after sample splicing showed a reproducibility in the range of 97.14–101.2% and RSD values of 1.05–4.40%. dos Santos et al. used a sustainable green synthesis to prepare gold nanoparticles and to prepare composites with graphene, for the development of a sensor for the detection of caffeic acid [88]. Gold nanoparticles were synthesized through four steps that included the preparation of banana pulp (Musa sapientum) extract and its application. The resulting nanoparticles had a spherical shape with an average particle size of 14.4 ± 2.5 nm as well as a characteristic reddish color. Also, UV–Vis characterization showed a characteristic band at 533 nm. The composite material was obtained by a simple ultrasonic treatment of the mixture of components until homogeneity was achieved. Using SWV as an analytical method for the detection of caffeic acid, the detection and quantification limits at the nanomolar level of 16 and 52 nmol L−1, respectively, were achieved, while the linear range was in the range of 0.05 to 10 μmol L−1. Finally, the method was applied to the determination of caffeic acid in various coffee samples and compared with the standard UV–Vis method. The excellent agreement of the results demonstrated the significant potential of the developed method in commercial use. Carboxylated multi-walled carbon nanotubes, obtained by treating for 18 h in a solution of 4.0 mol/L HNO3 and 10.0 mol/L H2SO4 mixed in a ratio of 1:3, were used for the in situ growth of Ce-metal–organic frameworks by Chen et al. [89]. In a typical synthesis of Ce-MOF, sulfanilic acid was dispersed in warm water under ultrasound, then Ce(NO3)3·6H2O was dissolved into this mixture. Separately, trimesic acid was dissolved in ethanol and slowly added to the cerium solution, which was stirred at 60 °C for 1 h. The product was collected by centrifugation, washed several times with fresh ethanol, and vacuum-dried at 60 °C. A suspension of MWCNTs-COOH and 4 mL formic acid was used for the in situ growth of Ce-MOFs. Both the classically synthesized MOF and the in situ grown MOF had a rod structure, while the presence of functional groups was confirmed by the FT-IR method. The high crystallinity of the material showed enviable electrocatalytic properties with the final analytical parameters: linearity range 1.5–200 μM and detection limit of 0.14 μm. Recovery results in green tea samples ranging from 97.6 to 103.5% demonstrated the excellent precision and accuracy of the method. By functionalizing carbon nanofibers in HNO3 and H2SO4 solutions, –OH, –C=O, and –COOH functional groups were introduced into the base material and this material was used to create composites with Bi2S3 and finally for the detection of caffeic acid in food beverages [90]. Bi2S3 nanomaterial was prepared by a simple hydrothermal method, during overnight treatment at 180 °C. The composite material was synthesized by ultrasonic treatment for 30 min. In this way, materials with high crystallinity were obtained and no other crystalline phases were transferred, which demonstrated high sample purity. The average particle sizes of Bi2S3, carbon nanofibers (CNFs), and Bi2S3/CNF nanocomposites were 30.1 nm, 35 nm, and 23.05 nm, respectively. Morphological analysis showed the irregular shape of the Bi2S3 nanoparticles and their regular distribution over CNFs. BET analysis showed that the Bi2S3/CNF nanocomposite exhibited a specific surface area, pore volume, and pore diameter of 170.48 m2 g−1, 0.2852 cc g−1, and 5.4875 nm, respectively. Final analytical characteristics, linearity range of 0.1–500 μM, and detection limit of 108 nM, as well as excellent selectivity were used for the determination of caffeic acid in grape juice and apple juice with recovery values in the range of 84.8 to 97.5%. A very interesting example of a top-down method of nanoparticle synthesis is the synthesis of AgNPs by laser ablation by Ognjanović et al. [91]. In the synthesis method, the Ag plate was ablated using a 15 mJ Nd:YAG picosecond laser beam (FWHM = 150 ps, EKSPLA SL212, EKSPLA, Vilnius, Lithuania) operating at a fundamental wavelength of 1064 nm with a repetition rate of 10 Hz. The incident angle of the laser beam was ~90° and the silver plate was irradiated with the defocused laser beam. The glass container with the silver plate and organic solution was placed on the xy stage in order to achieve this; with each laser impulse, a fresh area of the plate was treated. Using the dynamic light scattering (DLS) method, it was shown that the average size of the nanoparticles was 220 ± 51 nm, and the UV–Vis method showed a characteristic peak at 400 nm. The thus-synthesized material was used for the determination of gallic acid, by the drop-casting modification of printed electrodes. The obtained analytical parameters of the method, the detection range of 0.50 µM to 10 µM, with an LOD of 0.16 µM and an LOQ of 0.50 µM, as well as its successful application in the analysis of honey, wine, and juice samples, showed almost no matrix effect on this sensor and great practical possibilities.

4. Challenges and Future Perspectives

The synthesis of nanomaterials can be carried out through two basic directions: bottom-up and top-down methods. Both directions have their advantages and disadvantages, and it is not possible to say which is the best synthesis direction to choose. The top-down method is a destructive method that decomposes the starting material into smaller components and then into nanoparticles. The bottom-up method is a constructive method, and it creates nanomaterials from atoms through the formation of clusters. Taking into account the above literature data on developed sensors for the detection of biologically active compounds, the greatest challenge in future research can be considered the selection of the material and the method of its preparation. Very often, the response of nanomaterials cannot be predicted through the method of interaction with the target analyte, but structural and morphological characteristics play a very important role in the final parameters of the electroanalytical method. In order to obtain the desired characteristics of the material (large effective surface area, excellent conductivity, stability, etc.) a combination of synthesis methods or multi-step synthesis is required. Another approach may be through the formation of multicomponent materials, nanocomposites, and nanohybrids, which, through the proper selection of components, can provide two key properties of nanomaterials for electrochemical sensors: conductivity and strong interaction with the target analyte. Given the importance of this field of research and the large number of research groups dealing with this topic, a significant increase in publications on this topic is expected in the future, as well as the possible transfer of technology from laboratory work to commercialization.

There are key factors in the development of the field of nanotechnology and its connection with electrochemical sensors that require close attention in the future. They can be summarized as follows: (i) Stability and Fouling: The long-term stability of electrochemical sensors in real biological matrices is one of the main challenges. The main problem that prevents the reuse of electrochemical sensors is the increased interaction with other components of complex matrices. To prevent this, it is necessary to develop strategies to reduce biofouling, through the selection and use of different surface coatings or the selection of nanostructured materials that could reduce the interaction with other molecules present in the samples. Good results in the long-term performance of sensors can play a key role in their practical application; (ii) Reproducibility and Scalability: The production of nanomaterials and modified electrodes in serial production often encounters problems of consistency between different batches. These reproducibility issues could be addressed by standardizing the synthesis process, controlling all the important parameters of nanomaterial production and applying new technologies such as 3D printing or microfluidic platforms that enable the precise dosing of components and uniform conditions throughout the entire process of nanomaterial preparation; (iii) Disposable vs. Regenerable Sensors: This work shows that there is a significant difference between the disposable and regenerable approaches in the development of electrochemical sensors based on nanomaterials. While disposable sensors offer the advantage of simplicity and the reduced risk of contamination, thus preventing fouling and ensuring a stable and uniform signal, regenerable sensors offer the possibility of reuse and lower costs in long-term applications. Therefore, it can be considered crucial to properly recognize the specific application for each of these sensor types and develop efficient protocols for their use; (iv) Multiplexing: With the increasing need for the simultaneous detection of multiple bioactive compounds, exploring the possibilities of multiplexing becomes crucial. This involves the development of sensors that can simultaneously measure several analytes, which requires innovative approaches in the design and modification of nanomaterials in order to achieve high selectivity and precision for each of the analytes tested. The possibility of achieving multi-analyte monitoring can be reflected in the preparation of complex composite structures and multi-component nanomaterials. A major problem in this direction can be seen in the difficulty of achieving the uniformity of nanomaterial systems; (v) Machine Learning/AI: Machine learning and artificial intelligence are becoming key unavoidable components of various scientific fields. Therefore, the greater role of machine learning and artificial intelligence techniques can significantly improve the performance of electrochemical sensors. These technologies can help in the analysis of complex data from real samples, which results in better pattern recognition and thus sensor selectivity. In the future, the integration of these technologies can enable faster and more accurate diagnostic tools.

5. Conclusions

There is a large amount of literature on the preparation of sensors for various applications where electrochemical sensors play a dominant role. The number of articles in this area has a constant growth trend. Electrochemical sensors are characterized by a fast response, simple preparation approach, wide operating range, low detection limits, and great potential for miniaturization. This study summarizes recent approaches in the development of electrochemical sensors based on nanomaterials. Different types of nanomaterials represent the basis of modern electroanalytical chemistry. The general principles of using nanoparticles are based on increasing the conductivity of the electrode surface by introducing these materials as well as increasing the interaction of the analyte with the electrode. Finally, these phenomena result in improving the analytical characteristics of the developed methods.

Advances in nanotechnology and the precise engineering of recognition elements enhanced the development of electrochemical sensors. Thanks to materials with controlled nanostructures, the electrode surface area and conductivity are increased, enabling more efficient transduction of chemical changes into measurable signals. At the same time, these nanostructures often contribute directly to signal generation, resulting in systems with increased sensitivity and high specificity. The synergy of multifunctional materials, recognition elements, and electrochemical techniques further results in better selectivity, stability, and reproducibility.

Among the many new electrode modifiers, nanocomposites based on carbon nanostructures remain the most prevalent, but a growing array of metallic, transition-metal, and metal-oxide nanoparticles of various shapes has also been very important. Combining these nanomaterials with porous substrates enhances analyte adsorption capacity and therefore method sensitivity. In parallel, there is an increasing interest in “green” technologies: paper-based sensors, alternative media as a replacement for organic solvents, and nanomaterials and nanocomposites obtained from renewable and sustainable sources. Because electrochemical devices do not require additional components to detect the signal and can be directly integrated and applied, the combination with portable instruments and disposable parts paves the way today. The growing demand for real-time, cost-effective food screening is driving the development of practical devices for everyday use. Although the methods discussed have been validated on real samples against reference techniques, a lot of promising approaches remain in the literature. Many of these are poised for implementation in the coming years.

In summary, based on the literature review, it can be concluded that the determination of analytes that have “good” electroactivity and known redox behavior can be focused on metal and metal-oxide nanoparticles, where the electrocatalytic contribution of such nanomaterials is key to achieving the favorable sensitivity of the developed method as well as improved selectivity. In contrast, analytes whose electrode reaction is limited by the electron transfer rate and only by interaction with the electrode surface require complex nanomaterial structures, predominantly based on carbon nanomaterials and composites with metal and metal-oxide nanoparticles. Materials based on MOFs and COFs stand out as an excellent class of nanomaterials for this application, where both effects can be achieved in a single structure.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.B.P., M.O. and D.M.S.; methodology, B.B.P., M.O. and D.M.S.; software, M.O.; validation, B.B.P., M.O. and D.M.S.; formal analysis, B.B.P., M.O. and D.M.S.; resources, D.M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, B.B.P., M.O. and D.M.S.; writing—review and editing, B.B.P., M.O. and D.M.S.; visualization, M.O.; project administration, D.M.S.; funding acquisition, D.M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors acknowledge the financial support from the Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia (contract Nos. 451-03-66/2025-03/200168; 451-03-136/2025-03/200017), the Faculty of Sciences and Mathematics, University of Priština in Kosovska Mitrovica, Project Number IJ-2301, and EUREKA CAT-TECH project No. 23218.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article material. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Generalić Mekinić, I.; Šimat, V. Bioactive Compounds in Foods: New and Novel Sources, Characterization, Strategies, and Applications. Foods 2025, 14, 1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robotics, O. Bioactive Compounds: Types, Biological Activities and Health Effects; Nova Science Publishers: Hauppauge, NK, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Leite, J.I. The Role of Bioactive Compounds in Human Health and Disease. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahfoudhi, N.; Ksouri, R.; Hamdi, S. Nanoemulsions as Potential Delivery Systems for Bioactive Compounds in Food Systems: Preparation, Characterization, and Applications in Food Industry. In Emulsions; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 365–403. ISBN 978-0-12-804306-6. [Google Scholar]

- Pai, S.; Hebbar, A.; Selvaraj, S. A Critical Look at Challenges and Future Scopes of Bioactive Compounds and Their Incorporations in the Food, Energy, and Pharmaceutical Sector. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 35518–35541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okechukwu Ohiagu, F.; Chikezie, P.C.; Chikezie, C.M. Toxicological Significance of Bioactive Compounds of Plant Origin. Pharmacogn. Commun. 2021, 11, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba-Ostria, C.; Carrera-Pacheco, S.E.; Gonzalez-Pastor, R.; Heredia-Moya, J.; Mayorga-Ramos, A.; Rodríguez-Pólit, C.; Zúñiga-Miranda, J.; Arias-Almeida, B.; Guamán, L.P. Evaluation of Biological Activity of Natural Compounds: Current Trends and Methods. Molecules 2022, 27, 4490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madej, K.; Piekoszewski, W. Modern Approaches to Preparation of Body Fluids for Determination of Bioactive Compounds. Separations 2019, 6, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeszka-Skowron, M.; Zgoła-Grześkowiak, A.; Grześkowiak, T.; Ramakrishna, A. (Eds.) Analytical Methods in the Determination of Bioactive Compounds and Elements in Food; Food Bioactive Ingredients; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; ISBN 978-3-030-61878-0. [Google Scholar]

- Apak, R.; Çapanoğlu, E.; Shahidi, F. (Eds.) Measurement of Antioxidant Activity and Capacity: Recent Trends and Applications, 1st ed.; Functional Food Science and Technology Series; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-1-119-13538-8. [Google Scholar]

- Munteanu, I.G.; Apetrei, C. Analytical Methods Used in Determining Antioxidant Activity: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranwal, J.; Barse, B.; Gatto, G.; Broncova, G.; Kumar, A. Electrochemical Sensors and Their Applications: A Review. Chemosensors 2022, 10, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Gupta, R.; Bansal, D.; Bhateria, R.; Sharma, M. A Review on Recent Trends and Future Developments in Electrochemical Sensing. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 7336–7356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antuña-Jiménez, D.; González-García, M.B.; Hernández-Santos, D.; Fanjul-Bolado, P. Screen-Printed Electrodes Modified with Metal Nanoparticles for Small Molecule Sensing. Biosensors 2020, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crapnell, R.D.; Garcia-Miranda Ferrari, A.; Dempsey, N.C.; Banks, C.E. Electroanalytical Overview: Screen-Printed Electrochemical Sensing Platforms for the Detection of Vital Cardiac, Cancer and Inflammatory Biomarkers. Sens. Diagn. 2022, 1, 405–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamalasekaran, K.; Sundramoorthy, A.K. Applications of Chemically Modified Screen-Printed Electrodes in Food Analysis and Quality Monitoring: A Review. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 27957–27971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yáñez-Sedeño, P.; Campuzano, S.; Pingarrón, J.M. Screen-Printed Electrodes: Promising Paper and Wearable Transducers for (Bio)Sensing. Biosensors 2020, 10, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.M.; Da Silva, A.D.; Camargo, J.R.; De Castro, B.S.; Meireles, L.M.; Silva, P.S.; Janegitz, B.C.; Silva, T.A. Carbon Nanomaterials-Based Screen-Printed Electrodes for Sensing Applications. Biosensors 2023, 13, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harun-Ur-Rashid, M.; Imran, A.B.; Foyez, T. Voltammetric Sensors Modified with Nanomaterials: Applications in Rapid Detection of Bioactive Compounds for Health and Safety Monitoring. Discov. Electrochem. 2025, 2, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkel, C.; Özbek, O. Green Electrochemical Sensors, Their Applications and Greenness Metrics Used: A Review. Electroanalysis 2024, 36, e202400286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, B.-R.; Govindhan, M.; Chen, A. Carbon Nanomaterials Based Electrochemical Sensors/Biosensors for the Sensitive Detection of Pharmaceutical and Biological Compounds. Sensors 2015, 15, 22490–22508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, R.R.; Chusuei, C.C. Carbon Nanotubes, Graphene, and Carbon Dots as Electrochemical Biosensing Composites. Molecules 2021, 26, 6674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milne, S.A.; Lasserre, P.; Corrigan, D.K. Fabrication of a Graphite-Paraffin Carbon Paste Electrode and Demonstration of Its Use in Electrochemical Detection Strategies. Analyst 2024, 149, 4736–4746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]