Abstract

Organic electrochemical transistors (OECTs) are compelling artificial synapses because mixed ionic–electronic coupling and transport enables low-voltage, analog weight updates that mirror biological plasticity. Here, we engineered solid-state, polymer electrolyte-gated vertical OECTs (vOECTs) and elucidate how electrolyte molecular weight influences synaptic dynamics. Using Pg2T-T as the redox-active channel and pDADMAC polymer electrolytes spanning low- (~100 k), medium- (~300 k), and high- (~500 k) molecular weights, cyclic voltammetry reveals reversible Pg2T-T redox, while peak separation and current density systematically track ion transport kinetics. Increasing electrolyte molecular weight enlarges the transfer curve hysteresis (memory window ΔV_mem from ~0.15 V to ~0.50 V) but suppresses on-current, consistent with slower, more confining ion motion and stabilized partially doped states. Devices exhibit rich short- and long-term plasticity: paired-pulse facilitation (A2/A1 ≈ 1.75 at Δt = 50 ms), frequency-dependent EPSCs (low-pass accumulation), cumulative potentiation, and reversible LTP/LTD. A device-aware CrossSim framework built from continuous write/erase cycles (probabilistic LUT) supports Fashion-MNIST inference with high accuracy and bounded update errors (mean −0.02; asymmetry 0.198), validating that measured nonidealities remain algorithm-compatible. These results provide a materials-level handle on polymer–ion coupling to deterministically tailor temporal learning in compact, robust neuromorphic hardware.

1. Introduction

The human brain, with its unparalleled capacity for parallel, low-power, and adaptive computation, has long served as a paradigm for next-generation artificial intelligence hardware [1,2,3]. Unlike conventional von Neumann architectures that physically separate memory and processing units, biological neural networks seamlessly integrate information storage and computation, enabling massively parallel signal processing with minimal energy consumption. Emulating such efficiency demands a new class of materials and devices capable of reproducing key neural functions, mimicking synaptic plasticity, integrating multimodal sensory inputs, and dynamically adapting to external stimuli [4,5]. Among emerging device platforms, organic electrochemical transistors (OECTs) have gained prominence as highly versatile neuromorphic building blocks [6,7,8,9]. Their intrinsic mixed ionic–electronic conduction, biocompatibility, and low-voltage operation in aqueous environments endow them with the unique ability to bridge electronic and biological domains [10,11]. In OECTs, modulation of channel conductivity arises from electrochemical doping and dedoping processes driven by ionic flux between the electrolyte and the organic mixed ionic–electronic conductor (OMIEC) channel [12,13]. When a gate bias is applied, mobile ions penetrate the OMIEC, altering its oxidation state and consequently modulating the drain current. These mechanisms enable OECTs to emulate synaptic behaviors with high fidelity and energy efficiency, making them ideal candidates for bioinspired computation and bioelectronic interfacing [14,15].

Despite these advances, OECTs based on liquid electrolytes or ionic gels still face fundamental challenges in stability, controllability, and large-scale integration [16,17,18]. The volatility and leakage of liquid electrolytes, together with uncontrolled ionic distributions, compromise device reproducibility and system reliability. Moreover, the difficulty in tailoring ionic transport pathways and relaxation times restricts precise control over synaptic temporal dynamics, such as paired-pulse facilitation, spike rate-dependent plasticity, and long-term potentiation/depression, thereby limiting the implementation of robust learning rules in solid-state neuromorphic architectures [19,20,21]. Achieving reliable bioinspired computation therefore requires precise regulation of ionic transport to deterministically control charge-carrier injection and synaptic weight evolution [22,23]. Polymer electrolytes have recently emerged as an effective route to address these issues. By immobilizing mobile ions within a polymeric host matrix, they create a mechanically robust, leakage-free, and tunable ionic environment while maintaining adequate ionic conductivity for efficient electrochemical gating [24]. The molecular attributes of the polymeric host matrix, such as molecular weight, chain entanglement, and segmental mobility, govern ion diffusion kinetics, doping capacity, and charge retention, all of which critically define synaptic response dynamics [25,26,27,28]. However, most existing studies modulate electrolyte composition or blending ratio to tune device performance, whereas the direct correlation between single-component polymer electrolyte molecular weight and OECT behavior, particularly its impact on neuromorphic synaptic functions, remains largely unexplored.

In this work, we engineered solid-state polymer electrolyte-gated vertical OECTs (vOECTs) that leverage molecular weight-tuned poly(diallyldimethylammonium chloride) (pDADMAC) electrolytes interfaced with Pg2T-T channels. The vertical geometry minimizes ion transport distance and enables compact integration, while molecular weight variation systematically tunes ionic mobility. Through combined electrochemical characterization and synaptic behavior analysis, we reveal how high-molecular weight electrolytes expand memory windows and stabilize partial doping states, whereas higher-molecular weight counterparts enable slow, nonvolatile conductance updates. Device-level plasticity is validated through paired-pulse, frequency-dependent, and long-term learning tests, and system-level performance is simulated using CrossSim-based probabilistic look-up tables. Together, these findings establish molecular weight engineering of polymer electrolytes as a powerful materials-level strategy for temporal learning dynamics in solid-state neuromorphic systems.

2. Materials and Methods

Materials and chemicals: The organic mixed ionic–electronic conductor (OMIEC) Pg2T-T used as the transistor channel material was purchased from Derthon Optoelectronics Materials Science Technology Co., Ltd. (Shenzhen, China). The crosslinker DtFDA was synthesized following previously reported procedures. Poly(diallyldimethylammonium chloride) (pDADMAC) electrolytes with different average molecular weights (~100,000, ~300,000, and ~500,000) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). The Ag/AgCl paste used for gate electrodes was also sourced from Sigma-Aldrich. All solvents, including chloroform, acetone, and isopropanol, were of analytical grade and purchased from Sigma-Aldrich unless otherwise specified.

Device fabrication: To fabricate the OECT devices, Si/SiO2 substrates were first ultrasonically cleaned in isopropanol (IPA) for 15 min and then dried with a nitrogen gun. Subsequently, bottom source electrodes (30 μm × 30 μm channel footprint) were deposited by thermal evaporation of Cr (3 nm) and Au (100 nm) at rates of 0.1 Å s−1 and 1 Å s−1, respectively. The substrates were then treated with oxygen plasma to enhance surface wettability. A semiconductor precursor solution of Pg2T-T (10 mg mL−1) and DtFDA (20 mg mL−1) was prepared and mixed at a mass ratio of 5:1. The mixed solution was spin-coated onto the treated substrates at 3000 rpm for 20 s (vertical channel length ~100 nm), followed by UV exposure (365 nm) for 3 min to initiate photocrosslinking. The unexposed regions were developed using chloroform, leaving the patterned semiconductor film intact. Next, top drain electrodes (Au, 100 nm) were deposited through a shadow mask. The gate electrodes were fabricated by screen-printing commercial Ag/AgCl paste (500 μm × 500 μm). Finally, polymer electrolytes (pDADMACs) with different molecular weights were drop-cast onto the channel/gate region and gently dried, completing the solid-state OECT fabrication process.

Film and device characterization: Electrical performance of the OECTs was measured using an Agilent B1500 semiconductor parameter analyzer (Santa Rosa, CA, USA). Synaptic behaviors were evaluated by applying voltage pulse trains and recording real-time drain current with a source meter (NI S8842, Shanghai, China), enabling precise timing control of stimulation and readout. Cyclic voltammetry (CV) was performed on a CHI660E electrochemical workstation (Austin, TX, USA) to assess ionic transport characteristics and probe film redox processes.

Simulation of neuromorphic computing: Device-level neuromorphic behavior was modeled using CrossSim (Sandia National Laboratories, Albuquerque, NM, USA). Conductance trajectories of the OECT synapses were experimentally acquired under successive potentiation and depression pulses and used to construct an empirical look-up table (LUT). Conductance values were discretized into uniform bins, and state-dependent probability distributions of conductance change (ΔG) were derived via statistical sampling. During inference, CrossSim updates synaptic weights by stochastically sampling ΔG from the distribution associated with the current conductance bin in the experimentally derived LUT, thereby capturing the intrinsic nonlinearity and stochasticity of the devices. The Fashion-MNIST dataset (Zalando, Berlin, Germany) was used as the training set for backpropagation prior to LUT-based inference.

3. Results and Discussions

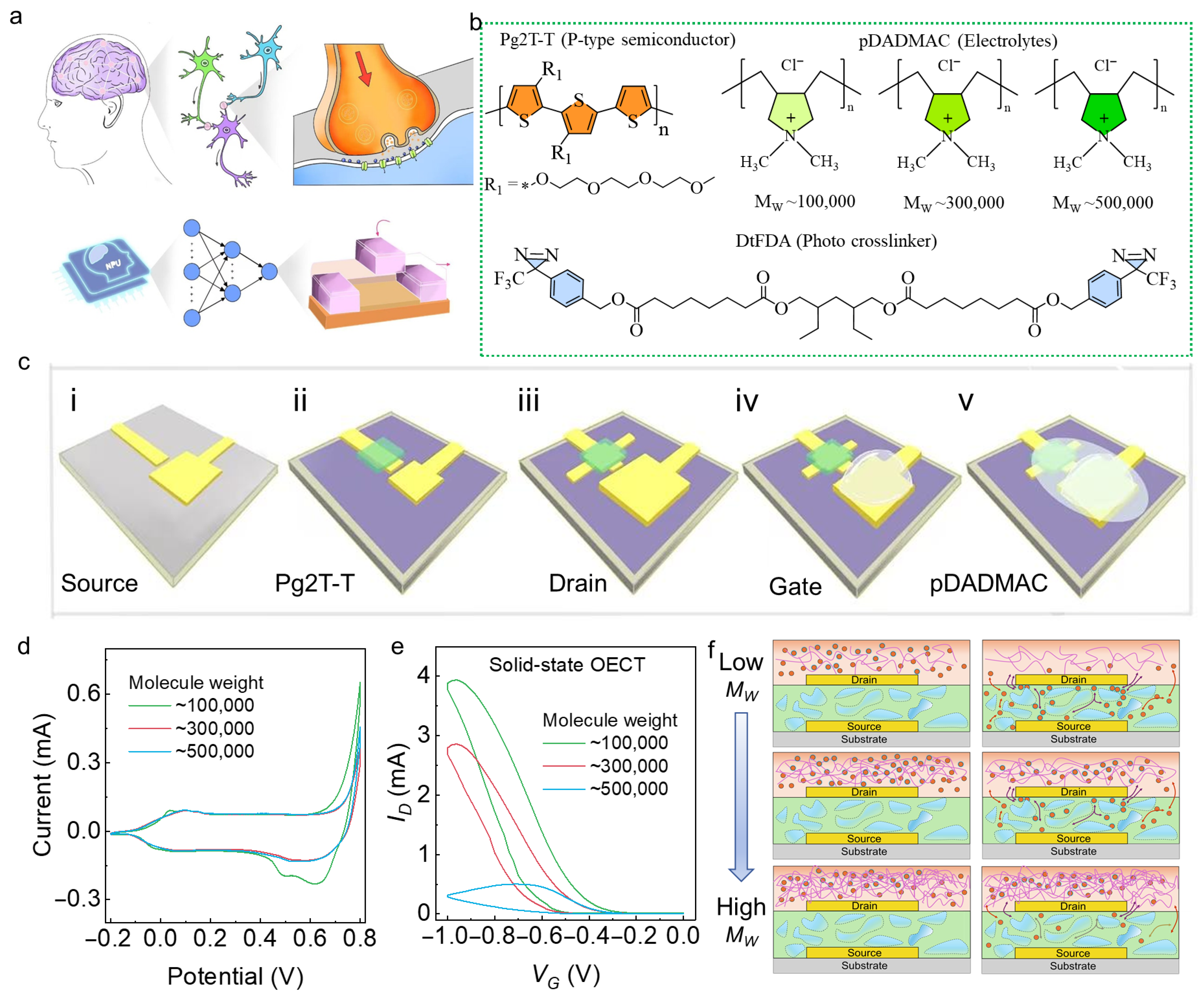

Inspired by the structural and functional correspondence between biological synapses and transistors, we use a vertical organic electrochemical transistor (vOECT) platform capable of emulating neuromorphic plasticity. In biological synapses, neurotransmitter diffusion dynamically modulates the synaptic weight to control neural signal transmission (Figure 1a). Analogously, in OECTs, ion migration within an electrolyte governs charge doping in the organic semiconductor, allowing electrical modulation of conductance. This analogy guided the design of a vOECT architecture that integrates an ionically active solid polymer electrolyte pDADMAC with a redox-active organic semiconductor (Pg2T-T), whose chemical structures are shown in Figure 1b. Unlike conventional planar geometries, the vertical stacking shortens the ionic pathway and spatially confines ion flow. Since ionic mobility, coordination strength, and electrochemical stability in solid pDADMAC electrolytes are highly dependent on polymer chain length, we systematically tuned the molecular weight (MW) of the pDADMAC (low-MW ~100,000, medium-MW ~300,000, and high-MW ~500,000) while keeping the semiconductor and crosslinker constant. The molecular-scale schematic (top right) illustrates that increasing MW leads to longer chain entanglement, decreased free volume, and tighter ion coordination, parameters that critically determine ionic diffusion kinetics and state retention in the device. The fabrication sequence (Figure 1c) involved stepwise deposition of the bottom source, patterning of the Pg2T-T channel, definition of the top drain, and final deposition of the Ag/AgCl gate and the different molecular weight pDADMAC electrolytes. This multilayer structure ensures well-controlled ionic access while suppressing lateral leakage, providing a robust platform for comparative evaluation of different electrolytes. Cyclic voltammetry (CV) measurements on Au/Pg2T-T films coated with pDADMAC of varying MW reveal distinct redox kinetics. All samples exhibit reversible oxidation and reduction processes characteristic of Pg2T-T, with oxidation peaks centered at ~0.35–0.45 V and reduction peaks near ~0.10 V (Figure 1d). The current density decreases systematically with increasing MW, reflecting slower ion mobility and reduced ionic conductivity in entangled networks. Concurrently, the anodic–cathodic separation widens from ~0.25 V (low-MW) to ~0.45 V (high-MW), confirming the transition from fast, diffusion-limited to kinetically hindered charge compensation. To assess the charge transport kinetics, we further performed scan rate-dependent CV measurements over the range 20–100 mV s−1 (Figure S1). The peak currents scale linearly with the square root of the scan rate, indicating that the redox process is predominantly diffusion-limited rather than surface-confined. This diffusion-controlled behavior is consistent with ion transport within the polymer matrix during device operation. Next, the transfer characteristics of vOECTs exhibit pronounced gate voltage hysteresis corresponding to ion-limited behavior (Figure 1e). Under our standard electric readout conditions, the OECTs with low-, medium-, and high-molecular weight electrolytes exhibit maximum drain currents of 3.94 mA, 2.87 mA, and 0.48 mA, respectively; turn-on voltages of −0.18 V, −0.19 V, and −0.22 V; and On/Off ratios of 397, 715, and 103. The memory window (ΔV_mem) increases with polymer MW, rising from ~0.15 V for low-MW to ~0.50 V for high-MW electrolytes, while the on-state drain current decreases due to restricted volumetric doping. The gate voltage hysteresis originates from the restricted ion transport in the high-molecular weight electrolyte. As the molecular weight of pDADMAC increases, the polymer chains become more entangled and form a denser, more tortuous ionic pathway. This significantly slows ion migration into and out of the Pg2T-T channel. During the forward sweep, ions can still gradually enter the semiconductor and induce polaron formation, but during the reverse sweep their extraction is much slower because many ions remain confined within these restricted domains. This inverse correlation indicates that high-MW electrolytes suppress ion diffusion, stabilizing trapped charge states and enabling nonvolatile modulation. The schematic illustration elucidates the following physical mechanism (Figure 1f): Low-MW pDADMAC allows rapid ion migration through loosely entangled chains, generating high conductance (Top). Medium-MW pDADMAC introduce moderate tortuosity, achieving balanced performance (Middle). High-MW pDADMAC form dense ion-confining matrices that hinder doping at the semiconductor bulk, thus amplifying hysteresis (Bottom). Notably, the high-MW electrolyte yields the widest memory window, enabling robust nonvolatile conductance modulation. Although the drain current is lower, this is not detrimental for neuromorphic operation; in fact, reduced current directly translates to lower energy consumption. Thus, the combination of an enlarged memory window and low steady-state current in the high-MW device facilitates energy-efficient, multilevel conductance modulation, an essential requirement for synaptic function emulation.

Figure 1.

Bioinspired design and fabrication of polymer electrolyte-gated OECTs. (a) Conceptual schematic illustrating the analogy between biological synapses and electrochemical transistors. (b) Molecular structures of the study, highlighting the redox-active Pg2T-T semiconductor and polyelectrolyte pDADMAC as electrolyte that mediates electrochemical doping/dedoping. (c) Stepwise fabrication process of the OECT: (i) source deposition, (ii) Pg2T-T active layer coating, (iii) drain formation, (iv) gate definition, and (v) solid pDADMAC electrolyte deposition. (d) CV curves of Pg2T-T films gated by electrolytes of different molecular weights, revealing distinct oxidation/reduction associated with ion injection dynamics. (e) Transfer curves of OECT with variable pDADMAC electrolytes. (f) Schematic illustration of the molecular weight-dependent ion transport and electrochemical modulation process.

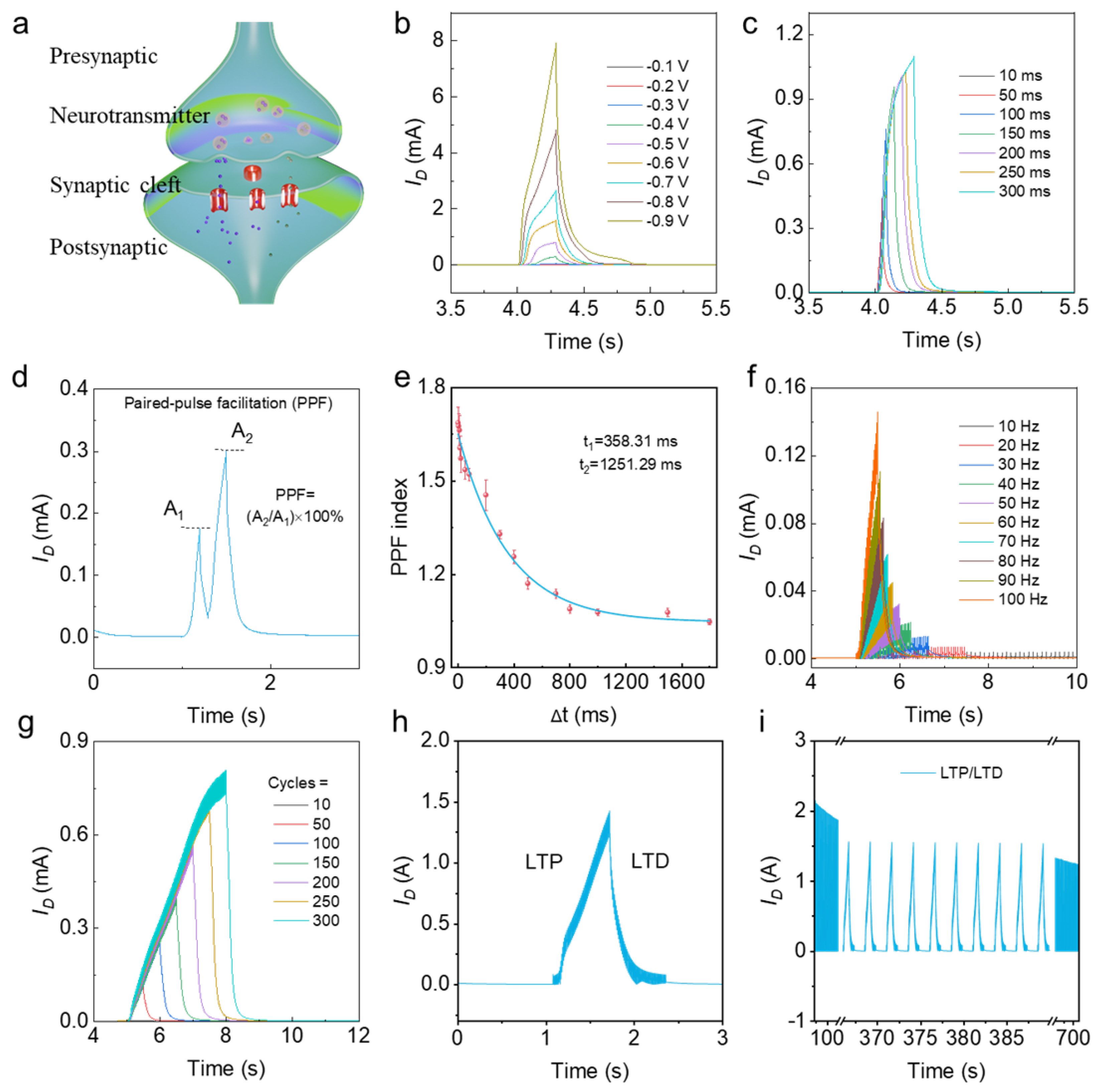

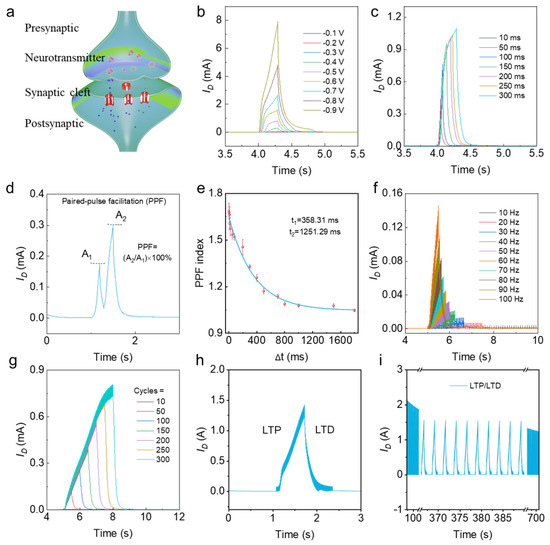

Next, OECTs gated by high-molecular weight pDADMAC for synaptic performance were investigated. The high chain entanglement and reduced segmental mobility of this polymer slow down ion migration, thereby stabilizing local doping profiles and yielding pronounced hysteresis in electrical characteristics. Figure 2a schematically depicts the OECT-based artificial synaptic junction, where the gate bias drives mobile ions through the polymer electrolyte into the OMIEC channel, emulating neurotransmitter-mediated charge transfer across a biological synaptic cleft. As shown in Figure 2b, the transient drain current (ID) exhibits a clear dependence on the applied gate voltage (−0.1 V → −0.9 V). Increasing gate amplitude enhances the degree of ionic injection into the semiconductor, directly modulating the channel conductance in an analog manner. Furthermore, varying the pulse width from 10 ms to 300 ms (under a constant gate bias, Figure 2c) also effectively controls the current amplitude: broader pulses induce stronger and more sustained channel doping due to the intrinsically slow ionic mobility within the entangled polymer network. Thus, the observed current retention confirms the emergence of nonvolatile, history-dependent synaptic behavior, highlighting that the high-molecular weight polymer electrolyte confers bio-realistic temporal characteristics to the OECT. Paired-pulse facilitation (PPF) measurement (Figure 2d) reveals strong temporal correlation between consecutive presynaptic stimuli, demonstrating short-term synaptic plasticity in the solid-state OECT. When two identical voltage pulses (−0.7 V, 100 ms) are applied with an inter-pulse interval (Δt = 50 ms), the amplitude of the second excitatory postsynaptic current (A2) significantly exceeds that of the first (A1), yielding a facilitation ratio A2/A1 ≈ 1.75. This enhancement originates from the incomplete relaxation of mobile ions remaining within the OMIEC bulk after the first stimulus, which promotes additional doping upon the arrival of the second pulse. As summarized in Figure 2e, the facilitation ratio gradually decays with increasing Δt, the fitted time constants for the solid-state OECT are τ1 = 358.3 ms (fast component) and τ2 = 1251.3 ms (slow component), providing a physical foundation for mimicking multiscale temporal plasticity. To evaluate dynamic information processing capabilities, frequency-dependent EPSC responses were examined (Figure 2f). Under periodic spiking from 10 Hz to 100 Hz, the OECT exhibits a progressive transition from discrete, well-separated EPSCs at low frequency to a continuous baseline elevation and eventual saturation at high frequency. This transition signifies the accumulation of residual ions between successive spikes, resulting in an intrinsic low-pass filtering effect. Beyond transient learning, repeated identical stimuli reveal cumulative conductance modulation characteristic of short-term learning (Figure 2g). The EPSC amplitude increases quasi-linearly with spike number (10–300 pulses) before gradually approaching saturation as the channel nears its maximum doping limit. This nonlinear learning curve is analogous to synaptic weight evolution observed in biological neurons, where repetition strengthens synaptic efficacy up to a threshold. The learning rate and saturation behavior can be finely tuned through the amplitude, width, and frequency of applied spikes, offering a controllable mechanism for memory strength and duration. Moreover, Figure 2h,i capture long-term synaptic modulation, analogous to biological long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD). Repeated high-amplitude presynaptic spikes induce a persistent enhancement of the channel conductance, i.e., LTP. The EPSC baseline and peak both increase progressively and remain elevated even after stimulation ceases, signifying the establishment of a long-lived conductive state. Conversely, where continuous low-amplitude or negative-polarity pulses gradually reduce the EPSC amplitude. The symmetric and reversible transition between potentiation and depression underscores the OECT’s capability for bidirectional long-term weight adaptation. This multiscale emulation, from transient to enduring plasticity, demonstrates that polymer electrolyte OECTs can serve as unified neuromorphic primitives capable of real-time learning, memory formation, and adaptive computation at the edge, bridging the timescales and functionalities of biological and electronic intelligence.

Figure 2.

Polymer electrolyte-gated OECT as an artificial synapse and its functions. (a) Schematic of the biological synapse used as the bioinspired reference, highlighting ion shuttling across the cleft and receptor-mediated conductance modulation. (b) Excitatory postsynaptic current (EPSC) of the solid-state OECT recorded under single gate pulses with different amplitudes. (c) EPSC traces measured at fixed amplitude but varied pulse widths, showing time-integrative ion injection. (d) Paired-pulse facilitation (PPF), two closely spaced pulses produce a larger second EPSC because of residual ionic population, emulating short-term synaptic plasticity. (e) PPF index (A2/A1) versus inter-pulse interval (Δt) fitted with a decaying exponential. (f) Frequency-dependent EPSC under spike trains with different repetition rates. (g) Cumulative conductance potentiation under repeated identical pulses (number-of-pulse dependence). (h) LTP/LTD invoked by a train of potentiating/depression pulses. (i) Long-term LTP/LTD response.

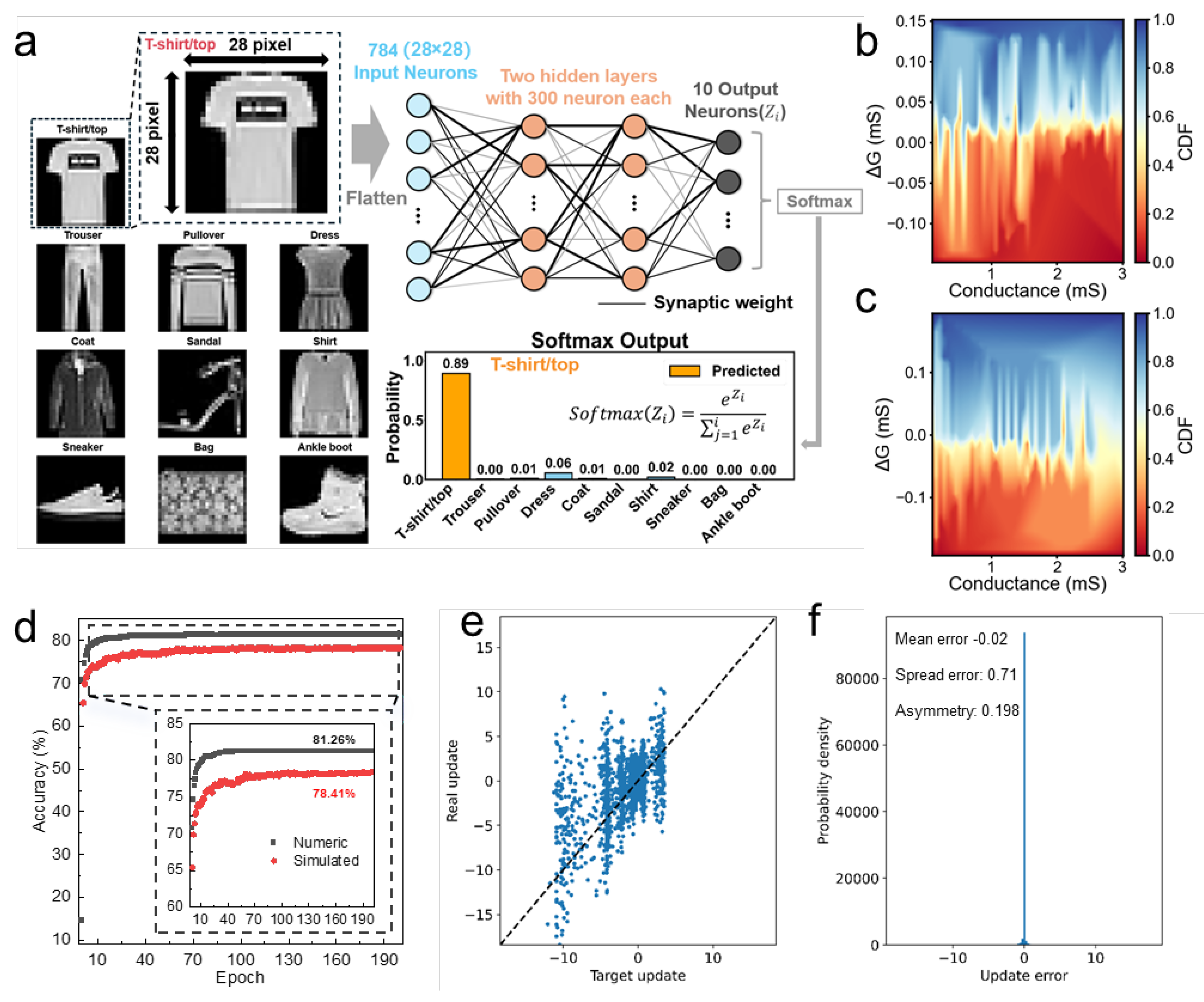

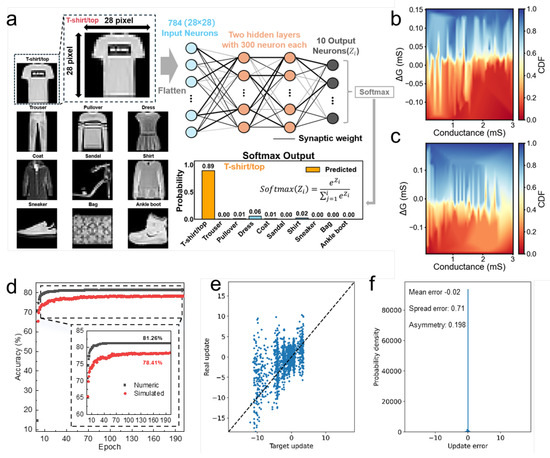

To quantitatively assess the neuromorphic learning capability of the fabricated solid-state synaptic OECTs gated by high-molecular weight polymer electrolytes (Mw ≈ 500,000), we implemented a deep-learning simulation framework using the CrossSim V2.0 platform. As illustrated in Figure 3a, the Fashion-MNIST dataset was adopted as a task owing to its well-established complexity for pattern classification. Each input image (28 × 28 pixels) was represented by 784 input neurons, followed by two fully connected hidden layers of 300 neurons each and a 10-node output layer corresponding to distinct clothing categories. All synapses are implemented by the experimentally measured OECT conductance states, and inference used a softmax readout. The exemplar output shows confident categorization of a T-shirt/top, evidencing separability of classes with the device-constrained weight dynamics. Next, we built a state-dependent look-up table (LUT) from repeated write/erase cycling and used it to stochastically update weights during training.

Figure 3.

Neuromorphic learning with solid-state synaptic OECTs. (a) CrossSim workflow and network used for Fashion-MNIST classification. (b,c) State-dependent plasticity extracted from 50 write and 50 erase cycles and compiled into a probabilistic look-up table (LUT). Color maps show the cumulative distribution function (CDF) of conductance change (ΔG) as a function of absolute conductance (G) for potentiation (b) and depression (c). (d) Learning curves comparing an idealized software baseline (gray) using continuous, symmetric updates with device-aware training (red) that samples ΔG from the LUT; inset shows early-epoch performance. (e) Hardware–algorithm agreement, scatter of realized versus target synaptic updates. (f) Update–error distribution.

The empirical potentiation and depression statistics (Figure 3b,c) reveal two key properties of the OECT synapse. First, updates are history-dependent: the distribution of conductance change (ΔG) narrows as the absolute conductance increases, indicating reduced plasticity near high-G states (i.e., update saturation). Second, updates are asymmetric: the cumulative distributions of positive and negative ΔG are not mirror images, implying different effective learning rates for potentiation and depression. These nonideal features, well captured by the LUT, are characteristic of electrochemical doping/dedoping governed by ion transport and local redox kinetics, as positive pulses drive ions efficiently into the semiconductor, producing strong conductance increases. In contrast, ion extraction during LTD is slower and partially hindered by confined regions and trap states in high-MW, so only part of the doped volume can be fully dedoped. Training with the device-aware LUT converges smoothly (Figure 3d, red), approaching the idealized software baseline (gray). Early-epoch performance already exceeds chance by a wide margin (inset accuracy ≈ 78.4%), demonstrating that the measured plasticity is sufficiently monotonic and reproducible to support gradient-free learning. Moreover, a granular comparison of target versus realized updates (Figure 3e) further quantifies hardware–algorithm mismatch. Points cluster around the unity line with bounded scatter, confirming that the LUT’s stochastic sampler reproduces the intended directionality of weight changes. The update–error histogram (Figure 3f) is sharply peaked near zero, with mean error = −0.02, spread = 0.71, positive update spread = 0.702, negative update spread = 0.901, and asymmetry = 0.198. The small bias indicates negligible systematic drift, while the modest but nonzero asymmetry reflects the device’s stronger constraint on erasure than on potentiation, an effect expected for ion doping/dedoping. Therefore, these results establish the feasibility of our solid-state OECT synapses as fundamental building blocks for energy-efficient, hardware-level neuromorphic processors capable of real-world pattern recognition and adaptive learning.

4. Conclusions

We have demonstrated that controlling polymer electrolyte molecular weight provides a direct and practical lever to co-design ionic kinetics and synaptic function in solid-state vOECTs. High-MW pDADMAC establishes dense, entangled ion pathways that slow migration, expanding the nonvolatile memory window and enabling robust synaptic responses. This ion-confinement/retention trade-off quantitatively connects electrochemical descriptors (redox peak spacing, current density) to system-level plasticity (PPF with τ1/τ2 on sub- and supra-second scales, low-pass EPSC accumulation, and stable LTP/LTD), offering a unifying framework to map molecular attributes onto learning rules. Importantly, device-calibrated probabilistic LUT training shows that intrinsic asymmetry and state-dependent update statistics do not preclude accurate inference; rather, they can be incorporated into algorithms with minimal accuracy penalties. Future efforts should integrate scalable microfabrication, endurance testing, and in-sensor learning tasks, and explore electrolyte chemistries that decouple ion mobility from mechanical robustness. By codifying electrolyte–semiconductor interactions into tunable temporal kernels, this work advances deterministic, energy-efficient, and integrable neuromorphic electronics.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/chemosensors13120428/s1, Figure S1: Scan-rate-dependent cyclic voltammograms of Pg2T-T channels gated with (left) low-MW, (middle) medium-MW, and (right) high-MW polymer electrolytes. For each film, CVs were recorded within the operating potential window in a three-electrode configuration, at progressively increasing scan rates as indicated by the color legend. The systematic increase in peak current and broadening of the redox features with scan rate confirms the diffusion-controlled nature of the electrochemical process in the polymer–electrolyte matrix.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.W. and J.Y.; methodology, L.G.; software, C.X.; validation, Y.P., C.L. and H.G.; formal analysis, B.W.; investigation, B.W.; resources, L.G.; data curation, Y.P.; writing—original draft preparation, B.W.; writing—review and editing, J.Y.; visualization, Y.P.; supervision, J.Y.; project administration, Y.H.; funding acquisition, Y.H. and J.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the Sichuan Science and Technology Program (No. 2023ZYD0161), the Sichuan Provincial Project under the Central Government-Guided Local Science and Technology Development Program (2024ZYD0097), and the Sichuan Province Key Laboratory of Display Science and Technology.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Farmakidis, N.; Dong, B.; Bhaskaran, H. Integrated photonic neuromorphic computing: Opportunities and challenges. Nat. Rev. Electr. Eng. 2024, 1, 358–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudithipudi, D.; Schuman, C.; Vineyard, C.M.; Pandit, T.; Merkel, C.; Kubendran, R.; Aimone, J.B.; Orchard, G.; Mayr, C.; Benosman, R. Neuromorphic computing at scale. Nature 2025, 637, 801–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Chen, P.; Zhu, H.; He, E.; Zhao, J.; Huo, W.; Jin, X.; Zhang, X. Bio-plausible reconfigurable spiking neuron for neuromorphic computing. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadr6733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuman, C.D.; Kulkarni, S.R.; Parsa, M.; Mitchell, J.P.; Date, P.; Kay, B. Opportunities for neuromorphic computing algorithms and applications. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2022, 2, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Wang, X.; Strachan, J.P.; Yang, Y.; Lu, W.D. Dynamical memristors for higher-complexity neuromorphic computing. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2022, 7, 575–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Wu, M.; Yu, X.; Yu, J. Device design principles and bioelectronic applications for flexible organic electrochemical transistors. Int. J. Extrem. Manuf. 2023, 6, 012005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohayon, D.; Druet, V.; Inal, S. A guide for the characterization of organic electrochemical transistors and channel materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2023, 52, 1001–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravariu, C. From enzymatic dopamine biosensors to OECT biosensors of dopamine. Biosensors 2023, 13, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wustoni, S.; Surgailis, J.; Zhong, Y.; Koklu, A.; Inal, S. Designing organic mixed conductors for electrochemical transistor applications. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2024, 9, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Chen, H.; Zhang, P.; Hartel, M.C.; Cao, X.; Diltemiz, S.E.; Zhang, Q.; Iqbal, J.; de Barros, N.R.; Liu, L. OFET and OECT, two types of Organic Thin-Film Transistor used in glucose and DNA biosensors: A Review. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 22, 11405–11414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, A.; Griggs, S.; Gasparini, N.; Moser, M. Organic electrochemical transistors: An emerging technology for biosensing. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 9, 2102039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Zhang, Q.; Lai, Y.; Xie, M.; Liu, C.; Zhang, D.; Peng, Y.; Bai, L.; Wu, M.; Feng, L.-W. High-loading homogeneous crosslinking enabled ultra-stable vertical organic electrochemical transistors for implantable neural interfaces. Nano Energy 2024, 129, 110062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.; Gao, L.; Yao, Y.; Kim, J.; Zhang, D.; Forti, G.; Duplessis, I.; Wang, Y.; Pankow, R.M.; Ji, X. Small-Molecule Mixed Ionic-Electronic Conductors for Efficient N-Type Electrochemical Transistors: Structure-Function Correlations. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202414180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleh, A.; Koklu, A.; Uguz, I.; Pappa, A.-M.; Inal, S. Bioelectronic interfaces of organic electrochemical transistors. Nat. Rev. Bioeng. 2024, 2, 559–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkoupidenis, P.; Zhang, Y.; Kleemann, H.; Ling, H.; Santoro, F.; Fabiano, S.; Salleo, A.; Van De Burgt, Y. Organic mixed conductors for bioinspired electronics. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2024, 9, 134–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Gao, L.; Liu, C.; Guo, H.; Huang, W.; Zheng, D. Gel-Based Electrolytes for Organic Electrochemical Transistors: Mechanisms, Applications, and Perspectives. Small 2025, 21, 2409384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Chen, H. Solid-state organic electrochemical transistors (OECTs) based on gel electrolytes for biosensors and bioelectronics. J. Mater. Chem. A 2025, 13, 136–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, B.; Xi, X.; Wu, Y.; Wu, D.; Jiang, B.; Shen, C.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, F.; Su, Y.; Liu, R. Organic electrochemical transistors for monitoring dissolved oxygen in aqueous electrolytes of zinc ion batteries. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2024, 409, 135601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Dang, T.; Harrison, K.; Lill, A.; Dixon, A.; Lewis, E.; Vollbrecht, J.; Hachisu, T.; Biswas, S.; Visell, Y.; Nguyen, T.Q. Biomaterial-based solid-electrolyte organic electrochemical transistors for electronic and neuromorphic applications. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2021, 7, 2100519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, M.; Yang, C.Y.; Ji, J.; Caravaca, A.S.; Guo, Q.; Li, Q.; Donahue, M.J.; Gao, D.; Wu, H.Y.; Marks, A. A Photo-Patternable Solid-State Electrolyte for High-Performance, Miniaturized, and Implantable Organic Electrochemical Transistor-Based Circuits. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, e09314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Qu, Z.; Si, J.; Lee, Y.; Bandari, V.K.; Schmidt, O.G. Monolithically integrated solid-state vertical organic electrochemical transistors switching between neuromorphic and logic functions. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadt5186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krauhausen, I.; Coen, C.T.; Spolaor, S.; Gkoupidenis, P.; van de Burgt, Y. Brain-inspired organic electronics: Merging neuromorphic computing and bioelectronics using conductive polymers. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2307729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucchi, M.; Gruener, C.; Petrauskas, L.; Steiner, P.; Tseng, H.; Fischer, A.; Penkovsky, B.; Matthus, C.; Birkholz, P.; Kleemann, H. Reservoir computing with biocompatible organic electrochemical networks for brain-inspired biosignal classification. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabh0693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Lee, S.; Yokota, T.; Someya, T. Gas-permeable organic electrochemical transistor embedded with a porous solid-state polymer electrolyte as an on-skin active electrode for electrophysiological signal acquisition. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2200458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Lee, S.; Lee, W.; Yokota, T.; Fukuda, K.; Someya, T. Ultrathin organic electrochemical transistor with nonvolatile and thin gel electrolyte for long-term electrophysiological monitoring. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1906982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majak, D.; Fan, J.; Gupta, M. Fully 3D printed OECT based logic gate for detection of cation type and concentration. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2019, 286, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.D.; Trung, T.Q.; Lee, Y.; Lee, N.-E. Stretchable and stable electrolyte-gated organic electrochemical transistor synapse with a nafion membrane for enhanced synaptic properties. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2022, 24, 2100918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yin, X.; Cheng, H.; Liu, C.; Han, S.; Xie, W.; Chen, C. Improving Nonvolatile Properties of Solid-Electrolyte-Based Artificial Synapses via Ion Dynamics Modulation in Organic Electrochemical Transistors. SmartMat 2025, 6, e70025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).