Abstract

The rapid emergence of novel psychoactive substances (NPSs) after 2020 has created one of the most dynamic analytical challenges in modern forensic science. Hundreds of new synthetic cannabinoids, synthetic cathinones, synthetic opioids, hallucinogens, and dissociatives, appearing as hybrid or structurally modified analogues of conventional drugs, have entered the illicit market, frequently found in complex polydrug mixtures. This review summarizes recent advances in gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) for their detection, structural elucidation, and differentiation between 2020 and 2025 based on the ScienceDirect and Google Scholar databases. Due to its reproducible electron-ionization spectra, established reference libraries, and robustness toward complex matrices, GC-MS remains the primary tool for the separation and identification of emerging NPS. The current literature highlights significant improvements in extraction and pre-concentration procedures, derivatization strategies for thermally unstable analogues, and chromatographic optimization that enable discrimination between positional and stereoisomers. This review covers a wide range of matrices, including powders, herbal materials, vaping liquids, and infused papers, as well as biological specimens such as blood, urine, and hair. Chemometric interpretation of GC-MS data now supports automated classification and prediction of fragmentation pathways, while coupling with complementary spectroscopic techniques strengthens compound confirmation. The review emphasizes how continuous innovation in GC-MS methodology has paralleled the rapid evolution of the NPS landscape, ensuring its enduring role as a reliable, adaptable, and cost-effective platform for monitoring emerging psychoactive substances in seized materials.

1. Introduction

Recent decades have been marked by the appearance of new psychoactive substances (NPS) and illicit drugs. By definition, NPSs are synthetic compounds engineered to reproduce the effects of conventional illegal drugs, yet remain outside existing legal frameworks, thereby representing a significant international public health issue [1]. In the beginning, the term “new” or “novel” mainly signified their recent appearance on the illicit market, whereas the synthesis procedures had been available in the scientific literature for a longer time. Today, it is not uncommon to identify entirely new compounds among the hundreds present in seized samples [2]. A high number of substances, the lack of certified standards for the parent molecule and its metabolites, and limited data on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamic profiles in biological fluids make the detection and identification of NPSs a very challenging task for forensic toxicologists [3].

In the years following the COVID-19 pandemic, the dynamics of drug distribution, synthesis, and consumption changed markedly, with online marketplaces, local synthesis routes, and unconventional formulations becoming dominant [4,5,6]. The European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) issued a warning in April 2020 focusing on the potential effects of the pandemic on the growing drug market [7]. At the same time, traditional plant-based (cannabis, cocaine), synthetic (amphetamine, MDMA) substances and pharmaceuticals (antihypertensives, antidepressants, psychiatric drugs, and ibuprofen) have shown increasing trends and remained the most-consumed [8,9]. NPSs can also be found as adulterants in mixtures with other psychoactive compounds [1,10]. Therefore, it is of utmost interest to monitor these compounds as there is limited knowledge of the health harms, interactions with other drugs, and specific effects.

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) is conducting an Early Warning Advisory (EWA) program that lists NPSs identified by international drug enforcement, intelligence, health, and toxicology agencies. In the last update, more than 1396 NPS were reported in 153 countries and territories. Within this framework, the classification includes stimulants, synthetic cannabinoids, classic hallucinogens, synthetic opioids, sedatives/hypnotics, dissociatives, and unassigned compounds [11]. In the post-COVID-19 era, the highest number of NPS was recorded in 2024 (688) and the lowest in 2023 (540). It should be emphasized that these numbers present the unique compounds that were identified each year, but the number of newly described NPS was 101 (2024), 44 (2023), 44 (2022), 87 (2021), and 46 (2020) [12]. Out of the total number of compounds in 2024, the most common were stimulants (33%), synthetic cannabinoids (24%), and classic hallucinogens (14%). The percentage of appearance is similar over the time period from 2020 to 2025.

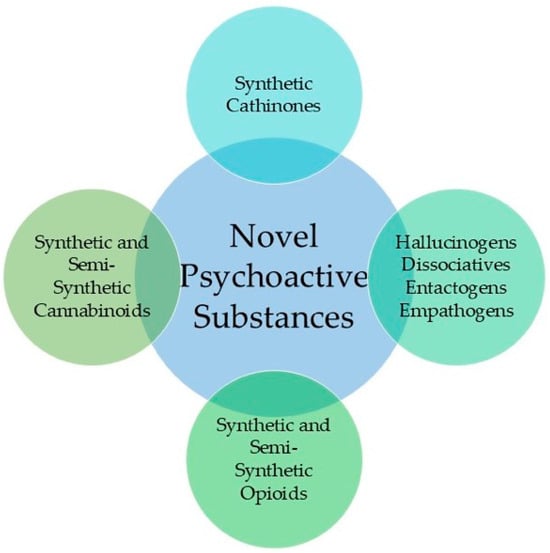

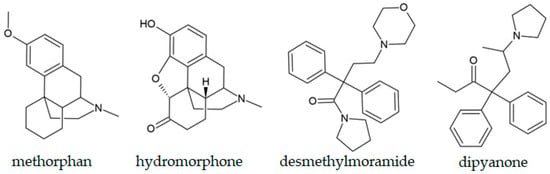

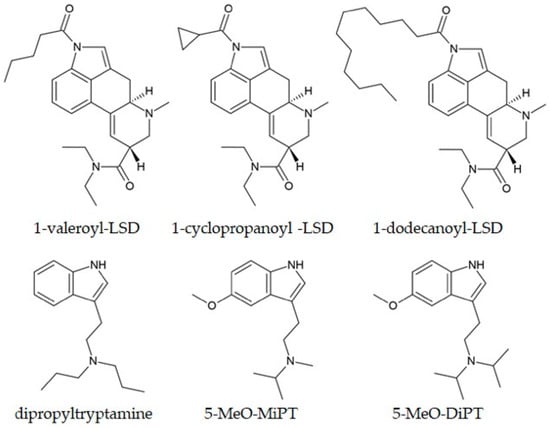

In this review, a simplified classification was adopted, with NPSs separated into four groups: synthetic and semi-synthetic cannabinoids; synthetic cathinones; synthetic and semi-synthetic opioids; and hallucinogens, dissociatives, entactogens, and empathogens (Figure 1). These four groups represent the most frequently identified NPS families between 2020 and 2025 and form the structural basis for the organization of the subsequent sections. Synthetic and semi-synthetic cannabinoids constitute one of the largest and most chemically diverse groups, comprising indole-, indazole-, and cyclohexyl-derived receptor agonists, as well as emerging semi-synthetic products such as hexahydrocannabinol (HHC) and tetrahydrocannabiphorol (THCP). Synthetic cathinones form the second major class and include β-keto analogues of amphetamine with extensive structural variation through aromatic substitution, alkyl-chain extension, and N-functionalization. Synthetic and semi-synthetic opioids, ranging from fentanyl analogues to benzimidazole derivatives and modified pharmaceutical opioids, represent a smaller but disproportionately high-risk group due to their potency and frequent implication in fatal intoxications. Finally, a heterogeneous category of hallucinogens, dissociatives, entactogens, and empathogens encompasses novel tryptamines, phenethylamines, arylcyclohexylamines, and MDMA-like substances, many of which appear only sporadically yet require analytical workflows capable of distinguishing closely related positional or stereochemical isomers.

Figure 1.

The classes of Novel Psychoactive Substances covered in this review are for the period between 2020 and 2025.

Several factors further complicate the work of law enforcement and analytical laboratories. Among the most critical are: (i) the chemical and structural diversity of NPSs and their often ambiguous or non-uniform legal status; (ii) the rapid turnover and transient availability of new compounds on the illicit market; (iii) the frequent presence of NPSs in complex mixtures or disguised formulations; and (iv) their distribution in small, inconspicuous quantities via online trade and postal systems. These characteristics make timely recognition and forensic identification increasingly difficult. Moreover, significant heterogeneity exists in national and regional legal responses [6]. While some countries adopt generic or analogue-based legislative frameworks that simultaneously prohibit entire structural families, others continue to rely on substance-specific scheduling, leaving room for rapid structural modification and legal circumvention [13].

An innovative way for identifying NPSs is through social media, which presents platforms for discussion regarding purity, dosage, pharmacological and toxicological effects, ways of administration, and comparison with common drugs [14]. This so-called “social media listening” proved effective for different public health concerns [15]. NPSfinder® is a web crawler that helps with the identification and categorization of NPSs through discussion, websites/fora, and comparison with registry databases by EMCDDA and UNODC [16]. Catalani and coworkers identified 18 NPSs (six cathinones, six opioids, two synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonists, two phenylcyclohexylpiperidine (PCP)-like molecules, and two psychedelics) for the period between January and August 2020, 10 of which were not previously enlisted by law enforcement agencies [14].

Studies have shown that people of different socio-economic characteristics and motivations abuse these substances for both recreational and therapeutic reasons. Popular festivals, bars, nightclubs, and special events are prevalent occasions in which the use of psychoactive substances is exceptionally high [1,17] and associated with high alcohol consumption [18]. Compounds now appear in vaping liquids, herbal mixtures, edibles, and impregnated papers, often labeled as harmless alternatives to controlled drugs (“legal highs”, “bath salts”, “research chemicals”, “plant food”, “plant fertilizer”, “smokable herbal mixtures”, etc.) [19,20,21,22]. Vincenti and coworkers reported that NPSs were detected in 92.6% of the samples collected by the Italian police between May and October 2020 in postal parcels [2]. Examined samples were not reacting with the standard field kits for common drugs; therefore, it was suspected that NPSs were present. More than 200 cases of intoxication by NPSs were reported between January 2020 and March 2022, with more than 30% of cases involving the combined consumption of several substances [23]. This expansion in chemical and matrix diversity has made the reliable identification and quantification of NPSs one of the most demanding analytical tasks in contemporary forensic science.

Various analytical techniques are used to identify compounds in seized materials, such as nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR), gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS), thin-layer chromatography, liquid chromatography with high-resolution mass spectrometry, infrared, and Raman spectroscopy, etc. [24,25,26,27,28,29]. Among the available instrumental techniques, GC-MS has maintained its role as the principal method, or the gold standard, for detection and confirmation [30,31,32]. Its strength lies in reproducible electron-ionization spectra and extensive reference libraries that facilitate inter-laboratory comparison. It should be noted that due to rapid market changes, many of the seized compounds are absent from spectral libraries, although comparisons with spectra of known compounds can be helpful [33,34]. Despite the development of liquid chromatography-high-resolution and tandem mass spectrometric systems, GC-MS remains indispensable because of its robustness, cost efficiency, and ability to provide both targeted and untargeted profiles from complex mixtures [35]. Compared to LC, GC is less susceptible to matrix effect and contamination, especially when highly concentrated biological samples are examined [36]. Also, lower maintenance and analysis costs are advantages of GC that make it a technique of choice in developing countries [37,38]. Several references emphasize the use of GC-MS for the metabolism study of these compounds [39,40,41]. Nevertheless, the importance of orthogonal techniques in NPS examination was suggested by several authors [31,42,43,44]. GC-MS is also widely used as a benchmark for the development of on-site and hyphenated techniques [35].

The post-pandemic environment posed analytical challenges that required adapting GC-MS workflows. Restrictions in precursor availability and disruptions in global supply chains resulted in numerous low-purity and chemically unstable analogues, frequently mixed with adulterants intended to alter volatility or mimic pharmacological effects [45,46]. Simultaneously, biological, herbal, beverage, and environmental matrices diversified, requiring optimized extraction and pre-concentration steps [47,48,49,50,51,52]. Techniques such as solid-phase extraction (SPE), liquid–liquid extraction (LLE), dispersive liquid–liquid microextraction (DLLME), dummy molecularly imprinted polymers (DMIP), and magnetic solid-phase extraction (MSPE) have become integral to GC-MS protocols, providing higher enrichment factors and cleaner chromatograms even at trace levels [21,47,48,53]. These advances underline the method’s flexibility and its ability to evolve alongside the illicit drug market.

Recent literature demonstrates that GC-MS is not confined to classical volatile analytes but can accommodate semi-volatile, thermally labile, or derivatized species that are characterized by complex mass fragmentation patterns [54,55]. The refinement of stationary phases, temperature programs, and chemical ionization has improved the separation of structural and positional isomers, while chemometric evaluation of electron-ionization spectra supports differentiation among closely related analogues [56,57]. Such approaches are particularly valuable for rapidly expanding compound families whose legal status depends on minute structural differences. Fragmentation mechanisms of various NPS classes, as related to different MS techniques, are also crucial for predicting the structural features of newly seized compounds [31,58]. In addition, GC-MS data increasingly serve as training input for pattern-recognition algorithms and chemometric models designed to automate classification and source attribution of seized materials [30,59,60].

This review is intended primarily for forensic toxicologists, forensic chemists, and analytical chemists who rely on GC-MS for the detection and characterization of emerging NPSs. It is also designed to serve as a comprehensive, accessible resource for graduate students and junior researchers entering the field. Accordingly, the review summarizes the methodological developments in the GC-MS analysis of novel psychoactive substances reported between 2020 and 2025, emphasizing new sample types, extraction and derivatization strategies, and combined approaches with complementary spectroscopic techniques. The primary search engines were Google Scholar and ScienceDirect, with the publication dates set from 2020. Some older references were included in the review when it was necessary to provide a general overview of a specific class or to mention notable examples. For analytical procedures, only references published after 2020 were included. The search terms included “GC-MS” AND one of the following groups: “synthetic cannabinoids”, “synthetic cathinones”, “designer benzodiazepines”, “fentanyls”, “hallucinogens”, “synthetic opioids”, and “polydrug NPS”. The discussion highlights how innovations in microextraction, column technology, and spectral interpretation have enhanced the relevance of GC-MS in the post-COVID analytical testing of NPSs. A special part of the review is devoted to the examination of polydrug mixtures and the application of advanced statistical methods in GC-MS analysis. The compounds are mentioned by their common names in the text, while the appropriate nomenclature is presented in the Abbreviations.

2. Analytical Challenges in GC-MS Analysis of NPS

The rapid evolution of the NPS market during the 2020–2025 period has required forensic chemists to rethink the way GC-MS workflows are conceptualized. Although the following sections of this review present detailed examples for specific substance families, several methodological principles apply across all classes of cannabinoids, cathinones, opioids, and hallucinogens. A unified overview is therefore necessary to understand why GC-MS remains effective despite the chemical heterogeneity and instability of many emerging compounds.

A central analytical challenge lies in the diversity of matrices and formulations encountered after 2020. NPSs now appear not only in powders and herbal materials but also in low-THC cannabis, disposable vapes, e-liquids, impregnated papers, counterfeit pharmaceutical tablets, biological samples, and even environmental matrices [61,62,63,64]. These heterogeneous substrates often contain pigments, excipients, stabilizers, plant resins, cutting agents, or polymeric residues, which can complicate chromatographic behavior. As a result, GC-MS workflows increasingly rely on matrix-specific extraction strategies rather than on a single universal protocol. Solid-phase extraction, liquid–liquid extraction, and modern microextraction approaches (DLLME, MSPE, DMIP) are used not because of their novelty but because they provide different selectivity windows, allowing laboratories to tailor cleanup to the physicochemical properties of each NPS class [40,48,65]. Extractive strategies further serve an interpretive purpose: cleaner chromatograms allow the analyst to differentiate true molecular features from thermally induced degradation products or polymer fragments originating from the sample matrix.

The thermal and structural stability of emerging NPS represents another shared analytical concern. Many post-2020 cannabinoids, cathinones, and benzimidazole opioids degrade, rearrange, or undergo side reactions in the GC injector. Derivatization, therefore, plays a dual role. Beyond reducing volatility, derivatization can suppress unwanted decomposition pathways, stabilize labile functional groups, or enhance diagnostic fragments that aid structural differentiation [66]. In contrast, for certain compound families, such as indazole-3-carboxamides and α-pyrrolidinophenones, derivatization may obscure class-specific fragments, making non-derivatized analysis preferable. The enantiometric purity of compounds can also be determined using appropriate derivatization [67]. The analyst must therefore balance increased chromatographic performance against the risk of generating artificially simplified or misleading mass spectra. This trade-off is increasingly important as clandestine laboratories introduce analogues with minimal structural changes intended to circumvent generic scheduling.

A third cross-cutting issue concerns chromatographic separation of closely related analogues. Many NPS families now include positional, constitutional, and stereochemical isomers with nearly identical EI-MS fragmentation profiles [68,69]. The separation of these analogues is challenging, particularly when analytes differ only by halogen placement (e.g., chlorocathinones), alkyl chain branching, or heterocyclic substitution. Adjustments in stationary-phase polarity, oven-temperature programs, and carrier-gas linear velocity often have a greater effect on discrimination than changes in the mass spectrometer settings. Recent work has demonstrated that column selectivity, rather than mass-spectral uniqueness, is now the primary factor determining whether two isomers can be differentiated in routine casework. This shift explains why laboratories are increasingly evaluating mid-polar or tailored stationary phases for NPS screening, especially when working with emerging semi-synthetic cannabinoids and benzimidazole opioids.

Despite these improvements, EI mass spectra remain the interpretive backbone of GC-MS-based NPS identification. Although fragmentation pathways differ among chemical classes, certain recurring patterns, for example, α-cleavage in cathinones, loss of tert-butyl esters in synthetic cannabinoids, and piperidine-ring fragmentation in fentanyls, serve as anchors for preliminary structural hypotheses [70,71]. The interpretive challenge arises when multiple structural analogues share the same diagnostic fragments, producing spectra that are highly similar yet evidence different pharmacological and legal implications [72]. In such cases, analysts increasingly rely on relative ion abundances, fragment–intensity ratios, and retention-time ordering rather than on the presence of any specific ion. Pattern recognition based solely on library matching is becoming insufficient for newly emerging analogues, many of which are absent from official reference databases.

The identification of many compounds within one NPS group has encouraged the development of chemometric and statistical tools such as PCA, hierarchical clustering, canonical discriminant analysis, and automated spectral-similarity metrics [30,73]. These approaches do not replace human interpretation but rather translate subtle spectral features into reproducible classifications [60]. Importantly, chemometrics also provides an orthogonal layer of evidence when chromatographic separation is incomplete, but the analyst must still determine the most plausible structural class [66]. As more laboratories perform these analyses, data standardization is emerging as a methodological priority, especially for sharing cross-border early warning signals about newly detected analogues.

3. Synthetic and Semi-Synthetic Cannabinoids

Synthetic cannabinoids (SCs) remain the most prevalent group of new psychoactive substances and continue to dominate forensic seizures worldwide. The term “cannabinoids” was initially used for the typical terpenophenolic C21 compounds in the cannabis plant, but the extended classification includes a large number of endocannabinoids, phytocannabinoids, and synthetic cannabinoids [74,75]. SCs first appeared around 2000, but were first detected in herbal products in 2008 by forensic scientists in Austria and Germany. Since then, the number of SCs in the market has steadily increased [76]. Out of 950 NPSs recorded by the EMCDDA, 254 are classified as SCs [77]. These compounds exhibit greater activity at cannabinoid receptors (CB1 and/or CB2) than ∆9-tetrahydrocannabinol (∆9-THC), resulting in more intense and short-lived effects [78,79]. SCs are often sold as solutions in organic solvents, sprinkled onto plant-based materials, and marketed online under names like “Spice” and “K2”. An overview of the pharmacological and toxicological properties of SCs is discussed in detail in the review by Roque-Bravo et al. [78]. Currently, 14 chemical families of SCs are recognized, some of which are not officially included in the banning laws [80]. Due to the complex structure and the plethora of functional groups in the core, tail, linker, and linked groups, several nomenclature systems are in use [81]. Their widespread distribution in herbal mixtures, e-liquids, disposable vapes, and even impregnated papers has created significant analytical challenges. Because of the lack of quality control of samples marketed as “synthetic marijuana”, the toxicity of SCs is unknown, as the individual compounds differ in potency, efficacy, and modes of action [82]. GC-MS has consistently been the frontline method for their detection, providing both targeted compound identification and non-targeted fingerprinting of complex mixtures. GC-MS remains particularly valuable because EI fragmentation generates highly class-diagnostic ions that facilitate the differentiation of indole-, indazole-, and cyclohexyl-derived scaffolds, even when reference standards are unavailable. However, many modern semi-synthetic cannabinoids are thermally labile and may partially degrade in the GC injector, making LC-MS or LC-HRMS more suitable for confirmatory analysis. In practice, GC-MS is most effective for rapid screening of herbal products, infused papers, and vaping materials, whereas LC-HRMS is required when resolving structural isomers or low-abundance metabolites. The study by Hubner et al. showed that available GC-MS spectral libraries are often insufficient to identify all tested samples purchased online [83].

3.1. Synthetic Cannabinoids in Powder and Herbal Mixtures

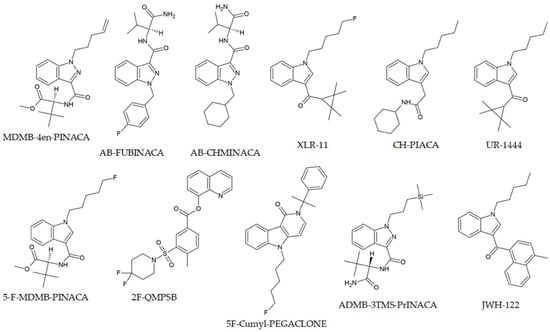

Recent studies have emphasized the diversity of SC formulations and matrices, such as paper, fabrics, and herb materials [84]. Low-THC cannabis or “CBD weed” is an industrially grown hemp. Most EU countries have an upper limit of allowed THC in these products of 0.2%. Several alerts have been issued in EU countries for the presence of synthetic cannabinoid MDMB-4en-PINACA (Figure 2) in low-THC products [85]. Out of 1142 examined in the article by Oomen and coworkers, 270 were found to contain this compound by GC-MS, and further proven by UPLC-QTOF [86]. Al-Eitan et al. investigated seized herbal blends from the Jordanian market, successfully quantifying AB-FUBINACA, AB-CHMINACA, and XLR-11 (all of which are presented in Figure 2) using GC-MS following liquid–liquid extraction, and highlighting wide variability in concentrations across samples [87] (Table 1). Similar findings were reported in Europe, where Pasin and colleagues identified CH-PIACA, a newly emerged indole-3-acetamide cannabinoid, in seized powders using combined GC-MS and high-resolution MS [88].

Figure 2.

Chemical structures of selected synthetic cannabinoids.

In 2021, a new NPS belonging to the synthetic cannabinoid class, 2F-QMPSB, depicted in Figure 2, was identified in three samples of herbal material by Tsochatzis et al. [89] during a screening by GC-MS. Along with 2F-QMPSB, the same study reported the spectral and chromatographic analysis of the acid precursor, 2F-MPSBA. The presence of the precursor was evident in the methanolic extract, suggesting that a transesterification reaction occurred, whereas the compound was absent from the chloroform extract. The choice of the stationary column (DB5-MS) used for the chloroform solution was not suitable for the analysis of acids [89].

Only the tentative identification of SCs by GC-MS was outlined by Al-Matrouk and Orabi, based on the investigation of samples seized in Kuwait [90]. Liu and coworkers reported the identification and quantification of 10 indole/indazole carboxamide synthetic cannabinoids in 36 herbal blends by GC-MS and NMR [91]. The concentration ranges of compounds determined by these methods were comparable (1.9–50.6 mg/g for GC-MS and 1.5–49.0 mg/g for NMR). The authors stated that GC-MS is more applicable for analyzing multicomponent mixtures when reference materials are available, as they enable quantification based on the molecular ion intensity. The linearity range was 0.05–2.5 mg/mL. The advantages of NMR were noted in the absence of reference materials. The presence of adulterants and preservatives masks the active compounds in herbal mixtures. Alves and coworkers reported the use of GC-MS, along with NMR, to characterize synthetic cannabinoids in nine different mixtures [92]. In addition to active compounds, the authors identified vitamin E, vitamin E acetate, and oleamide. Analysis of adulterants is important because these results can be used to link products to manufacturers [93,94]. These examples illustrate how clandestine laboratories continue to design novel scaffolds that challenge existing detection protocols.

3.2. Synthetic Cannabinoids in Infused Paper and Vapes

Alternative formulations of SCs have further complicated monitoring. Apirakkan et al. demonstrated that GC-MS, supported by complementary techniques, could identify AMB-FUBINACA and AB-CHMINACA not only in e-liquids but also in paper substrates intended for prison smuggling [62]. AMB-FUBINACA, a compound 85-fold more potent than THC, emerged in 2014 as a drug of abuse and is considered one of the most widely abused and seized [95,96]. In line with this, Abbott et al. confirmed the presence of multiple indazole-3-carboxamide SCs in impregnated letters intercepted in UK prisons, underlining the necessity of frequent spectral library updates [97]. Air monitoring approaches have also been explored; Paul et al. applied two-dimensional GC–TOFMS for airborne detection of SCs in prisons, though no direct confirmations were achieved, the study highlighted the potential of environmental monitoring as an early warning tool [98].

Beyond herbal and paper-based samples, vaping products have emerged as a key vector for SC delivery. Craft et al. recently reported that all seven illicit disposable vape pens submitted by a UK drug service contained only 5F-MDMB-PICA, at concentrations around 0.85 mg/mL, despite being sold as cannabis products [61]. Nguyen et al. described a validated GC-MS method for 5F-MDMB-PICA in the Vietnamese “American grass” market, achieving a detection limit as low as 0.06 µg/mL and quantifying an average content at 2.2% w/w in seized material [99]. These findings underscore the increasing shift toward vaping formulations and the importance of validated GC-MS methods for rapid, high-sensitivity detection.

A critical methodological development was presented by Sisco et al., who optimized a GC-MS protocol specifically for the discrimination of cannabinoids [100]. The method was validated on a panel of 50 compounds, encompassing both phytocannabinoids and a broad range of synthetic analogues. Using a DB-200 stationary phase and an isothermal oven program at 290 °C, the authors achieved reproducible retention times and improved separation between closely related analytes. Compound discrimination was further supported by automated spectral similarity testing, which allowed for differentiation even where the retention time overlap was minimal. Compared with a general confirmatory GC-MS method, the targeted protocol provided an order of magnitude higher sensitivity and markedly better retention time resolution. This study demonstrates that GC-MS can be adapted not only for screening but also for systematic classification of structurally related cannabinoids, a feature of considerable forensic value when large panels of emerging substances must be rapidly distinguished.

3.3. Synthetic Cannabinoids in Biological Samples

Clinical and toxicological monitoring also benefit from GC-MS. La Maida et al. developed a dual approach combining GC-MS screening and UHPLC-HRMS confirmation for oral fluid analysis after the controlled administration of JWH-122, JWH-210, and UR-144. They demonstrated sub-ng/mL detection, providing the first disposition data for these compounds in human oral fluid [101]. In the study by Pellegrini et al., the hydroxy metabolites of JWH-122, JWH-210, and UR-144 were identified in urine samples, along with the parent molecules, at sub-ng/mL concentrations using GC-MS. These were further confirmed by UHPLC-HRMS [41]. Urine is the most common biological fluid used in forensic examination of drug abuse, but due to the fast metabolism of SCs, parent molecules are rarely detected [102]. Due to the similar metabolic pathways, misidentification of compounds may occur [103]. The hydroxy metabolites are the primary metabolites of SCs, as determined in the other studies [104,105,106]. Other chemical modifications include hydroxylation and carboxylation on the alkyl site, hydroxylation on the indole group, defluorination, and glucuronidation in the second methanolic phase, where metabolites are present [107,108]. The mentioned study emphasized the need for other metabolites, such as glucuronidated metabolites, for the proper examination of compounds.

The presence of thermally unstable compounds and the need for derivatization limit the use of GC-MS compared to LC-MS [109,110]. Recently, Wang and coworkers identified ADB-4en-PINACA, MDMB-4en-PINACA, and ADB-BUTINACA in human hair for the first time using GC-MS/MS [111,112]. Hair samples offer many advantages over other samples, such as target stability, a long detection window, and a long-term history of abuse of different compounds, as hair grows around 1 cm per month [113,114,115]. The sample requires complex preparation, including washing in 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 0.1% detergent, distilled water, and acetone to remove exogenous contaminants. The samples are then cut into 2 cm sections, and methanol extraction is performed. The linear concentration range for ADB-4en-PINACA was 20–1000 pg/mg, while LLOQ and LOD were 20 and 10 pg/mg, respectively. Due to the low concentration and background noise, the single-stage GC-MS analysis was not sufficient. This study emphasizes that the derivatization of compounds was not needed.

Post-mortem GC-MS analysis of samples is also used to assess SC concentrations. In the article by Giorgetti et al., four cases of death involving 5F-Cumyl-PEGACLONE (Figure 2), a fluorinated analogue of Cumyl-PEGACLONE, the first cannabinoid with a γ-carbolinone core structure, are reported [116]. The concentration range was 0.09–0.45 ng/mL in femoral blood. The cases of death related to SCs are common in the literature, although the significance of toxicological results is often questionable [117]. For this purpose, the Toxicological Significance Score (TSS) is used, with values ranging from 1 (Low, alternative cause of death) to 3 (High, NPS is probably the cause of death, although other drugs may be present). In the study by Giorgetti, the cases were assigned TSSs of 1, 2, and 3, as in only one case, a contributory role of 5F-Cumyl-PEGACLONE was suggested, along with an acute heroin intoxication.

The extraction procedure for the GC-MS analysis of complex biological samples is another parameter to consider. Dispersive liquid–liquid microextraction (DLLME) involves the use of small amounts of immiscible organic solvents in water, which renders the technique very cheap and eco-friendly [118]. Mercieca et al. applied ultrasound-assisted DLLME for the rapid GC-MS detection of 29 selected cannabinoids and their metabolites in blood and urine samples [40]. The observed limits of detection (1–5 ng/mL), limits of quantification (5 ng/mL), and linearity were satisfactory.

Another improvement to the extraction method was described by Shokoohi Rad and coworkers, who applied magnetic solid-phase extraction (MSPE) with ortho-aminophenol-coated Fe3O4 nanoparticles coupled with DLLME for the trace analysis of 5F-ADB-PINACA and AB-FUNBINACA in human plasma samples (Figure 2) [65]. The linear ranges were much higher, ranging from 0.2 to 50 ng/mL, with enrichment factors of 213 and 437. MSPEs are used for other extraction procedures because they are fast and straightforward to synthesize, and their surfaces are easily modified [119,120,121]. Microextraction by packed sorbent (MEPS) is a simple, fast, and miniaturized extraction method that has shown promise for the analysis of NPS in liquid samples [122]. Sorribes-Soriano et al. concluded that semi-automated MEPS extraction on a C18-packed sorbent for third-generation cannabinoids yielded quantitative recovery and high sensitivity in subsequent GC-MS analysis, with LODs of 10–20 mg/mL in saliva samples [103].

Two interesting SC compounds containing silicon were examined by Zschiesche et al. [123] These compounds, ADMB-3TMS-PrINACA (Figure 2) and Cumyl-3TMS-PrINACA, have a trimethylsilyl propyl moiety connected to the tertiary indazole nitrogen. GC-MS was used to identify 34 and 38 metabolites of these compounds. The specificity of their biotransformation is the side-chain monohydroxylation (specific marker) and TMS-group cleavage, initiated by oxidative Si-demethylation. These biomarkers were later discovered in biological samples (blood, urine, and stomach content) of a deceased polydrug user. The carbon-silicon switch or “sila-substitution” in these compounds is performed to avoid legal restrictions and affect pharmacodynamics and metabolic stability [124,125]. Other silicone analogues of psychoactive compounds are described in the literature, such as 1S-LSD [126].

3.4. Semi-Synthetic Cannabinoids

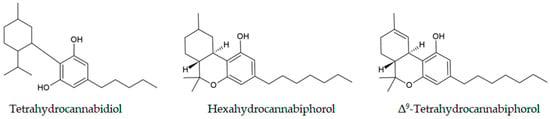

A special group of compounds, semi-synthetic cannabinoids (SSCs), is obtained by chemical modification of phytocannabinoids. The first SSC was (-)-trans-∆8-THC, discovered in the U.S. market in 2019 [127], produced from CBD through a ring closure reaction. Hexahydrocannabinol (HHC) is another SSC that was first reported to the EMCDDA in May 2022. By December 2022, it was found in almost all European countries [128]. These hexahydro derivatives of cannabinol are not scheduled under international drug conventions, which paves the way for their distribution in vape products and edibles [127]. HHC and cannabinol are the products of the thermal reduction and oxidation of tetrahydrocannabiphorol (Δ9-THCP) in e-cigarettes, as observed in the controlled conditions by GC-MS [64]. In the post-COVID-19 period, several other compounds have been determined by generic extraction in methanol and subsequent GC-MS analysis of the seized samples, including tetrahydrocannabidiol (H4-CBD), hexahydrocannabinol acetate (HHC-O-Acetate), hexahydrocannabiphorol (HHCP), and Δ9-THCP [129]. The structures of these compounds are shown in Figure 3. These were found in e-cigarette products (56%), hashish (20%), concentrates (17%), edibles (10%), and plant material (10%). ∆9 -THCP is a heptyl homolog of ∆9-THC, recently found in Cannabis sativa L. [130]. The low amounts in natural sources make it unprofitable for isolation, so it is usually produced by the chemical modification of CBD [131]. The manufacturers of this SSC claim it is derived from natural sources, but its legal status varies from country to country.

Figure 3.

Chemical structures of the cannabinoids identified in seized samples.

Schirmer et al. presented results of the GC-MS examination of a THCP vape liquid pen seized by Swiss customs [67]. Although the vape was labeled as having 90% THCP and 10% terpenes, the analysis showed the presence of enantiopure (6aR, 10aR)-∆9-THCP, along with isomeric compounds, derivatives, unreacted reactants, side products, and other chemical impurities. The results enabled the determination of the synthetic route, concluding that the compound was not isolated from natural sources. This provided authorities with the opportunity to control illegal production. Other studies in Japan and Germany also led to similar conclusions, as some of the samples did not contain THCP at all [67,132].

Table 1.

Selected GC-MS studies on synthetic cannabinoids (2020–2025).

Table 1.

Selected GC-MS studies on synthetic cannabinoids (2020–2025).

| Compound | Matrix/Sample Type | Notes/Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| AB-FUBINACA, AB-CHMINACA, XLR-11 | Seized herbal blends | First profiling of the Jordanian market; wide concentration variability. | Al-Eitan et al., 2020 [87] |

| AMB-FUBINACA, MMB-CHMICA, others | E-liquids, powders, blotting papers, and prison letters | Highlighted new formulations (e-liquids, impregnated papers) used for prison smuggling. | Apirakkan et al., 2020 [62] |

| JWH-122, JWH-210, UR-144 | Oral fluid of consumers | Validated oral fluid method; first disposition data after controlled administration. | La Maida et al., 2020 [101] |

| Δ8-THC, THC-O acetates, CBD-di-O-A | Commercial edibles & herbal products | First report of THC-O acetates and CBD-di-O A in consumer products. | Holt et al., 2022 [133] |

| CH-PIACA (indole-3-acetamide SC) | Seized powders | First identification of CH-PIACA in Europe, linked to class-wide legislative bans. | Pasin et al., 2022 [88] |

| 5F-MDMB-PICA | “American grass” is a herbal drug | Avg. content 2.2% w/w in seized samples; method fully ICH-validated. | Nguyen et al., 2023 [99] |

| 5F-MDMB-PICA, MMB-4en-PICA, 4F-MDMB-BUTINACA, MDMB-4en-PINACA | Prison mail (impregnated paper) | Library updates required for prison screening systems. | Abbott et al., 2023 [97] |

| SCs (not confirmed in samples) | Prison air (fixed + personal samplers) | First attempt to detect airborne SCs; no direct confirmation, but showed feasibility. | Paul et al., 2021 [98] |

| 5F-MDMB-PICA | Seven disposable illicit vapes | All vapes mis-sold as cannabis contained only SCs, highlighting high user risk. | Craft et al., 2024 [61] |

| Semi-synthetic cannabinoids (Δ8-THC, HHC, H4-CBD, HHC-O-Ac, HHCP, THCP) | Seized cannabis products | Reprocessed historical GC-MS data to quantify emergence: 15% (n = 216) of products positive for SSCs; HHC 10% most frequent. | Jørgensen et al., 2024 [129] |

| 21 synthetic cannabinoids (reference set) | NPS bought online (powders) and laced plant material | Built an NMR + GC-MS reference dataset; shows why GC-MS alone can mis-ID some SCs and how pairing with NMR resolves ambiguities. | Hübner et al., 2025 [83] |

| JWH-122, JWH 210, UR-144 and their hydroxylated metabolites | Urine samples of consumers | The hydroxylated metabolites and parent molecules were determined in sub-ng/mL concentrations. The samples underwent initial hydrolysis with β-glucuronidase. | Pellegrini et al., 2020 [41] |

| 2F-QMPSB and precursor 2F-MPSBA | Herbal samples | The new compounds, along with their precursors, were determined in the samples. | Tsochatzis et al., 2021 [89] |

| 50 cannabinoids (synthetic and phytocannabinoids) | Reference standard panel | Targeted GC-MS method differentiated 50 cannabinoids by retention time and spectral dissimilarity; supports systematic classification. | Sisco et al., 2021 [100] |

| 5F-Cumyl-PEGACLONE | Femoral blood | The femoral blood concentrations of 5F-Cumyl-PEGACLONE were used to determine the cause of death. | Giorgetti et al., 2020 [116] |

| 10 indole/indazole carboxamide SCs | Herbal blends | For quantifying multi-component mixtures, GC-MS was preferred when reference materials were unavailable; when they were available, NMR proved more useful. | Liu et al., 2021 [91] |

| 29 cannabinoids and their metabolites | Blood and urine samples | Ultrasound-assisted DLLME was a highly efficient microextraction technique for the quantification of 29 compounds in blood and urine samples. | Mercieca et al., 2020 [40] |

| 5F-ADB-PINACA and AB-FUBINACA | Human plasma samples | Magnetic solid-phase microextraction coupled with DLLME showed enrichment factors of 213 and 437. | Rad et al., 2020 [65] |

| ∆9 -Tetrahydrocannabiphorol | THCP vape pen | GC-MS analysis enabled discrimination between natural and synthetic THCP sources by identifying chemical impurities. | Schirmer et al., 2024 [67] |

| Synthetic cannabinoids | Herbal mixtures | GC-MS and NMR were employed to determine the active compounds together with adulterants and preservatives (vitamin E, vitamin E acetate, oleamide). | Alves et al., 2021 [92] |

| ADB-4en-PINACA | Human hair sample | The human hair sample underwent extraction, but derivatization was not required. | Wang et al., 2023 [111] |

4. Synthetic Cathinones

Synthetic cathinones are the second most common type of NPSs and the largest subclass of synthetic stimulants [134,135]. Their structural basis is cathinone, a natural alkaloid obtained from the Catha edulis plant [136]. The structure consists of a benzyl group, a keto group on the β-carbon, and an amine terminal group. These structural moieties led to the development of various derivatives, such as aromatic ring substitution, N-functionalization, and a change in α-chain length [137,138]. In the review paper by Nadal-Gratacós and coworkers, the effects of the structural changes on the activity were examined in great detail [139].

Cathinones are usually produced in clandestine laboratories using procedures described in the scientific literature or patents. Most synthetic cathinones act as stimulants by producing effects similar to cocaine and amphetamine (euphoria, tachycardia, aggressive behavior, etc.) [140]. The origin of their activity lies in their inhibitory effects on dopamine and noradrenaline transporters. They are usually found in crystal or powder form, which allows their oral or nasal administration [31]. These NPSs are usually sold on the internet as “bath salts”, “research chemicals”, and “plant food” [141]. The regulation of synthetic cathinones lags behind the substances sold on the illicit market, as their scheduling is carried out on a case-by-case basis [134]. Therefore, only slight structural modifications of existing compounds are needed to avoid legislative restrictions [134].

4.1. Separation of Structural Isomers

The standard method for the identification of synthetic cathinones is GC-MS, although due to their thermal lability and degradation, the interpretation of mass spectra can be complicated [54]. Tseng and coworkers concluded that the slower thermal gradient heat speed with prolonged analysis time improved the peak resolutions [142]. The choice of GC column and thermal gradients was the main factor affecting compound separation.

The enamine formation of cathinones is commonly observed in MS spectra, with a -2 Da mass shift of the base peak due to oxidative degradation [54]. Depending on the jurisdiction, there may be requirements to identify specific isomers, such as when one is legally controlled while the other is not. To overcome this challenge, Liliedahl and Davison applied the canonical discriminant analysis (CDA) to differentiate cathinones by GC-MS [30]. The method is based on relative ion abundances in the MS spectrum. When 15 peaks were used, the classification rates were higher than 90% for chloroethcathinone, methoxymethcathinone positional isomers, and several constitutional isomers.

Other multivariate methods for the differentiation of NPS isomers using GC-MS data are given in references [59,143,144]. The fragmentation mechanism of N-alkylated cathinones depends strongly on the mass spectrometry technique used, as shown in reference [31]. ESI and DART ion sources produced protonated molecular ions with very similar spectra, and the dominant pathway involved the loss of H2O for secondary amines and the formation of alkylphenones for tertiary amines. When EI is used, the most abundant peaks include acylium and iminium ions as the radical-directed cleavages occur. These findings are important for the structural elucidation of novel compounds and for predicting spectra based on available instrumentation.

Dhabbah presented a derivatization technique with menthyl chloroformate that could distinguish between S and R cathinone isomers in different parts of Catha edulis [57]. S-isomer, as the most psychoactive stereoisomer, had higher concentrations in stems, but lower in leaves. Another derivatization method involves N-methylimidazole-catalyzed acylation with acid anhydrides, which leads to the formation of highly stable compounds, with over six years of shelf life [66]. This methodology allows for the identification of positional isomers based on retention times, especially when reference samples are available. Derivatization also influenced the fragmentation routes, which are determined by the basicity of specific compounds.

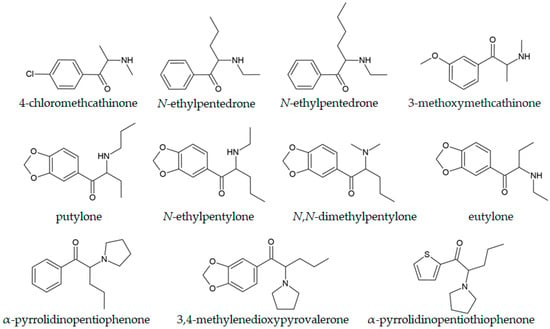

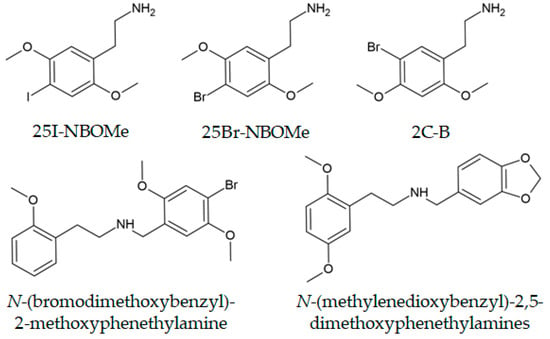

An interesting study by Nuñez-Montero and coworkers involved controlled administration of 4-chloromethcathinone, N-ethylpentedrone, and N-ethylhexedrone to consumers and GC-MS investigation of oral fluid and sweat [145] (Table 2). These compounds are depicted in Figure 4 to show their structural similarity. The ethyl acetate liquid–liquid extraction and derivatization with pentafluoropropionic anhydride (PFPA) provided the best compromise for sample preparation. The compounds administered intranasally were absorbed much more quickly than those administered orally, as indicated by the oral fluid analysis. Only 0.3% of the administered dose was determined in sweat. Although rare, this type of study is important for the precise examination of NPS metabolomic changes. Oral fluid is becoming a very popular alternative to other biological samples due to the relative ease of noninvasive collection and the potential for detecting parent molecules, although results are influenced by lipophilicity, matrix pH, and acid–base properties of compounds [146]. Other experimental studies with controlled administration of synthetic cathinones conducted in humans in the post-COVID-19 period are described in references [147,148,149,150,151,152,153].

Figure 4.

Chemical structures of selected cathinones.

4.2. Synthetic Cathinones with a 3,4-Methylenedioxy Moiety

The addition of the 3,4-methylenedioxy moiety to the cathinone core is the primary step in the preparation of 3,4-methylenedioxy-N-alkylcathinones, which are analogues of MDMA [154,155]. Depending on the number of carbon atoms in the aliphatic chain attached to the amino group, there are several notable compounds in this sub-family, which constitutes around 18% of synthetic cathinones. These include methylone, butylone, ethylone, eutylone, pentylone, and N-ethylpentylone with 1–6 carbon atoms.

Dixon et al. examined a new compound in this subfamily, putylone (Figure 4), an N-propyl-substituted synthetic cathinone analogue of butylone [156]. The routine quantification was achieved by GC-MS, with an LOD and LOQ of 0.09 and 0.26 µg/mL, respectively, and was successfully applied to the determination of the compound in seized tablets. An interesting case was described in reference [157], in which forensic experts suspected that N-ethylpentylone was present in a seized sample. Only after the examination of EI mass spectra and assignment of the peak at 71 m/z to (CH3)2N+=CH-CH2• was it possible to conclude that the compound was dipentylone. Liliedhal and coworkers proved that N-butyl pentylone isomers (N-isobutyl pentylone, two diastereoisomers of N-sec-butyl pentylone, and N-tert-butyl pentylone) could be differentiated by employing the GC-EI-MS technique, as verified by the NMR experiments [158]. The ratio between the abundance of fragment ions at 128 and 72 m/z was sufficient for this purpose. This ratio is a consequence of the methyl substituent’s position, which influences the fragmentation pattern, and is essential for predicting the MS spectra of structurally similar compounds. In the case of N-isopropylbutylone, the GC-MS technique did not give a definitive answer because of mass spectral similarities with N,N-dimethylpentylone, N-ethylpentylone, and putylone [159]. All of these compounds are shown in Figure 4. Only with the use of advanced NMR techniques (correlation spectroscopy (COSY), distortionless enhancement by polarization transfer (DEPT), heteronuclear multiple quantum coherence (HMQC), and heteronuclear multiple bond correlation (HMBC)) was the structure univocally determined.

Armenta et al. presented results of the examination of a sample that was sold on the Internet as ketamine, although it was proven to be 3′,4′-methylenedioxy-2,2-dibromobutyrophenone, a precursor in the synthesis of other cathinones (pentylone and methylenedioxy pyrovalerone) [34,160]. The GC-MS analysis yielded two peaks with the same chemical composition, probably due to the decomposition in the injector. The peak at 65 m/z corresponded to the fragment found in other brominated 3,4-methylendioxy derivatives. Mata-Pesquera and coworkers performed characterization of N-cyclohexyl butylone, a recently reported cathinone [161]. The retention time of this compound was 8.465 min, with the major peaks in the mass spectrum at 58.1, 41.1, 121.0, 831, and 232.1 m/z, which did not allow for the identification of the compound after comparison with the spectral libraries. The structure was determined based on the fragments, and it contained a 3,4-methylenedioxy moiety, present in MDMA. The experimental research was followed by the in silico predictions of the activity of the compound, and they found that the predicted effects were similar to MDMA, just without the hallucinogenic effect. These in silico approaches are a good starting point for predicting the biological activity of newly obtained compounds by comparing them with structurally similar substances. Other theoretical methods, in the first place, Density Functional Theory (DFT) proved important for the determination of the absolute configuration of newly obtained compounds [162]. Mayer, Black, and Copp identified and characterized a new substance, N-cyclohexylpentylone, in a seized sample in New Zealand. The major peak at 154.2 m/z, and minor peaks at 72.1, 55.1, 149.0, and 121.0 m/z could not be matched to any compound in the databases. Through NMR analysis and the presence of impurities, the structure of the unknown compound was determined. Other new synthetic cathinones were described with spectral and chromatographic data ready to be updated in respective databases in references [72].

4.3. α-Pyrrolidinophenone Derivatives

α-Pyrrolidinophenone derivatives are some of the most abused designer drugs [135]. Their most notable structural feature is the addition of a pyrrolidine ring to the generic cathinone structure [163]. Notable examples include α-pyrrolidinopentiophenone (α-PVP, “Flakka”, Figure 4), α-pyrrolidinobutiophenone (α-PBP), 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (3,4-MDPV), α-pyrrolidinoheptanophenone (α-PV8), α-pyrrolidinopentiothiophenone (α-PVT, Figure 4), and α-pyrrolidinopropiophenone (α-PPP) [20,164]. The activity of the mentioned compounds is higher due to their more potent inhibition of monoamine transporters, and they more easily pass the blood–brain barrier because of the lipophilicity of the pyrrolidine substituent [165,166].

Davidson and coworkers examined the fragmentation pattern of 22 α-pyrrolidinophenone derivatives by GC-EI-MS, LS-ESI-MS/MS, and DART-MS [167] (Table 2). ESI and DART mass spectra were almost indistinguishable with eleven protonated ions. Meanwhile, GC-EI-MS spectra were dominated by iminium and acylium ions because of high-energy deposition from 70 eV electron fragmentation, which reduced the likelihood of rearrangements [168], as previously discussed for N-alkylated cathinones. The fragmentation mechanism was unaffected by the substitutions, enabling rapid identification of compounds via shifts in the mass axis. The authors have noted that EI generally produces odd-electron ions, whereas ESI produces even-electron ions [58]. The chromatographic separation and electron ionization-quadrupole mass spectrometry identification of 5-PPDI, an indanyl analogue of α-PBP, and three of its regioisomers were reported by Ishii and coworkers [169]. The order of elution (1, 4, 2, 5-positional isomer) was the same on three columns, namely a nonpolar 100% dimethylpolysiloxane, a micropolar phenyl arylene polymer column, and a mid-polar column virtually equivalent to a (50%-phenyl)-methylpolysiloxane.

Segurado and coworkers proposed a novel method of extraction, a bar adsorptive microextraction followed by microliquid desorption, of α-PVT, α-PVP, and MDPV from oral fluids, followed by GC-MS analysis (BAµE-µLD/GC-MS) [170]. The N-vinylpyrrolidone sorbent phase used as a coating material for the mentioned compounds demonstrated good performance due to hydrogen bonding, π–π interactions, and hydrophobic interactions. The average recovery rate ranged from 43.1 to 52.3%, and good selectivity was also observed. Blood concentration determination of α-PVT was reported in the paper by Machado and coworkers, which included the SPE with GC-MS analysis in the single-ion monitoring mode [171]. The peak at 140 m/z was selected for quantification based on selectivity and abundance. The linearity correlation was observed over the concentration range of 10–1000 ng/mL.

4.4. Samples with Several Cathinones

The separation of polydrug samples containing several cathinones is a tedious task due to their structural similarity, the absence of a molecular ion under EI ionization, and the statistical parameters used to describe spectral similarity, as outlined in references [71,172]. Woźniak et al. developed a simple procedure for the simultaneous determination of 45 amphetamines and synthetic cathinones in whole blood samples with high recovery (83.2–106%), accuracy (89.0–108%), and precision [173]. The procedure included extraction and pentafluoropropionyl derivatization. Another methodology was proposed by Antunes and coworkers, which included SPE and derivatization with N-methyl-N-(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide (MSTFA) and trimethylchlorosilane (TMCS) for the accurate determination of four cathinones in whole blood samples [174]. The linearity range was 25–800 ng/mL, and efficiency was greater than 85%. Margalho et al. performed fast microwave derivatization of several cathinones with N-methyl-bis(trifluoroacetamide) (MBTFA) following SPE, a method that was successfully applied to 100 authentic blood samples [175]. The linearity range was similar to the previously mentioned derivatization procedure. The choice of derivatization agent depends on the structural features of the compounds, as concluded in reference [176]. For example, trimethylsilylation of chloromethcathinone isomers was needed for their complete separation [177]. Another standard biological sample containing synthetic cathinones is hair, which presents several effects that should be taken into account when discussing results, as reviewed by Bolcato and coworkers [52].

4.5. Synthetic Cathinones in Biological and Environmental Samples

GC-MS can also be used to quantify cathinones and their derivatives in plasma and brain tissue, as described by Bin Jardan and coworkers for methcathinone and its metabolite, ephedrine [47]. In complex matrices, the main advantage of GC-MS for synthetic cathinones lies in the consistent EI fragmentation pathways, as previously explained for α-cleavage and pyrrolidinyl-ring fragmentation, which support class confirmation and the identification of novel analogues. However, many halogenated or extended-chain cathinones are prone to thermal degradation or in-source rearrangement, reducing the reliability of GC-MS for trace-level quantification in biological matrices, where LC-MS/LC-HRMS provides superior sensitivity and stability. For this reason, GC-MS remains the method of choice for seized-drug screening and impurity profiling, while LC-MS is essential for metabolite analysis, stereoisomer resolution, and low-dose polydrug mixtures.

Hobbs and coworkers described the first case of fatal intoxication by 4-fluoro-3-methyl-α-PVP by analyzing body fluids [178]. The concentrations were calculated to be 26 ng/L in gray-top femoral blood and 20 ng/L in red-top vitreous humor using selected ion monitoring (SIM). Methcathinone is an analogue of methamphetamine, and it is already a controlled substance; therefore, it cannot be considered as NPS, but it is presented here as the representative of the synthetic cathinone class. This method was validated as sensitive and selective for the simultaneous quantification of both compounds, with a linearity range of 5–1000 ng/mg. SIM signals usually include the base peak and two qualifier ions chosen to achieve higher selectivity and sensitivity [176].

Weng and coworkers applied the previously mentioned MSPE procedure for the extraction of 16 cathinones from a urine sample [21]. When concentrations of these compounds in urine are concerned, an expected detection concentration should be less than 10 ng/mL. The sorbent consisted of Fe3O4 with amino-modified multi-walled carbon nanotubes (NH2-MWCNTs). The achieved linearity range was 0.005–5.00 µg/mL in complex matrices, with eco-friendly, fast detection that was also efficient and sensitive. Another novel designer drug, 3′,4′-methylenedioxy-α-pyrrolidinohexanophenone (MDPHP) and its metabolites were examined in urine samples of consumers, as GC-MS provided sufficient information for the prediction of metabolism in human samples [39]. The peak intensity of metabolites can be higher than that of a parent molecule, allowing their quantification in all biological samples, as shown for 4′-methyl-α-pyrrolidinohexanophenone (MPHP) and its 4′-carboxyl metabolite [179]. The prediction of the possible metabolites in urine can also be conducted using the online software (GLORYx), as shown in the reference [180].

The examination of the prevalence of NPSs in environmental samples is a common way to determine the scale of substance abuse. Wastewater-based epidemiology (WBE) has become a complementary tool for obtaining near-real-time information on drug consumption in a given area or during special occasions, such as music festivals, holidays, or sports events [181,182]. In this approach, both the aqueous fraction and the suspended particulate matter (SPM) can be examined. Langa and coworkers examined SPE in Portuguese wastewater for the presence of several amphetamine-like compounds, including several synthetic cathinones, by GC-MS [53]. They also performed enantiomeric profiling of compounds that were sorbed on SPM using the chiral agent (R)-(−)-α-methoxy-α-(trifluoromethyl)phenylacetyl chloride ((R)-MTPA-Cl). The highest concentrations were observed for (S)-amphetamine, while the concentrations of other substances were lower than in other European countries; however, the method proved reliable for the examination of WBE. Selective extraction of cathinone, methcathinone, mephedrone, methylone, and ethylone from wastewater was conducted by Han et al. on dummy molecularly imprinted polymers [48]. The extraction procedure took less than 5 min, and subsequent GC-MS analysis showed low LOD values (0.002–0.1 ng/mL), and the used sorbent demonstrated better cleanup ability.

GC-MS is also important as a confirmatory technique when new methodologies for detecting synthetic cathinones are developed. Yen et al. presented results of the detection of this class of compounds by hydrophobic carbon dot probes, and the results were confirmed by GC-MS [183]. Several cathinones, among which 4-chloromethcathinone (4-CMC), 4-chloroethcathinone (4-CEC), eutylone, and butylone were found mixed with instant coffee powder in a so-called “toxic caffe packets” that are popular in Taiwan [50].

Table 2.

Selected GC-MS studies on synthetic opioids (2020–2025).

Table 2.

Selected GC-MS studies on synthetic opioids (2020–2025).

| Compound | Matrix/Sample Type | Notes/Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| N-cyclohexyl butylone | Pills and crystal samples | Newly detected compound with MS spectra that did not match the libraries. | Mata-Pesquera et al., 2023 [161] |

| 3′,4′-methylenedioxy-2,2-dibromobutyrophenone | Powder | This precursor was identified through MS fragmentation in a sample that was sold as ketamine on the Internet. | Armenta et al., 2020 [34] |

| R and S-isomers of cathinone | Different parts of the Catha edulis plant | Derivatization with menthyl chloroformate and subsequent GC-MS analysis was successful for the quantification of different isomers in various parts of the plant. | Dhabbah, 2020 [57] |

| Five isomers of N-butyl pentylone | Pure compounds | The MS fragmentation pattern (the ratio of ion abundances at 128 and 72 m/z) can be used to distinguish isomers. | Liliedahl et al., 2023 [158] |

| Several amphetamine-like stimulants, including synthetic cathinones | Suspended particulate matter in wastewater | GC-MS technique with the derivatization agent efficiently determined concentrations of amphetamine isomers and other stimulants. | Langa et al., 2024 [53] |

| N-cyclohexyl pentylone | Pale brown powder | GC-MS fragmentation and NMR analysis were used to solve the structure of the newly encountered NPS | Mayer et al., 2024 [29] |

| Methcathinone and ephedrine | Plasma and brain tissues | The GC-MS method was developed for the simultaneous determination of both compounds with a high linearity range (5 to 1000 ng/mg). | Bin Jardan et al., 2021 [47] |

| cathinone, methcathinone, mephedrone, methylone, and ethylone | Wastewater | The selective sorption was done on dummy molecularly imprinted polymers; GC-MS analysis had LOD values between 0.002 and 0.1 ng/mL. | Han et al., 2022 [48] |

| 22 α-pyrrolidinophenone | Pure compounds | Fragmentation pathways were examined using different instruments: GC-EI-MS, LS-ESI-MS/MS, and DART-MS. GC-EI-MS fragmentation mechanism was not dependent on the substituents present. | Davidson et al., 2020 [167] |

| 5-PPDI and three regioisomers | Solution | The order of elution was the same for the three columns used, and compounds were differentiated by the second-generation product ion spectra in ESI-LIT-MS. | Ishii et al., 2022 [169] |

| putylone | Seized tablets | The proposed GC-MS method successfully quantified putylone in seized tablets. | Dixon et al., 2023 [156] |

| 4-CEC, α-PVP, 4-Cl-PVP, and MDPV | Whole blood samples | SPE and derivatization with MSTFA and TMCS, linearity range 5–800 ng/mL, extraction efficiency > 85%. | Antunes et al., 2021 [174] |

| 4-Fluoro-3-methyl-α-PVP | Femoral and heart blood, vitreous humor | Post-mortem analysis of body fluids by GC-MS helped identify this compound. | Hobbs et al., 2022 [178] |

| α-PVT, α-PVP, and MDPV | Oral fluid | BAµE-µLD/GC-MS of three components, with average recoveries between 43.1 and 52.3%, and good selectivity. | Segurado et al., 2022 [170] |

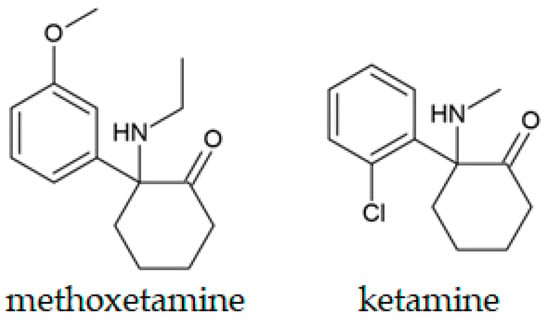

5. Semi-Synthetic and Synthetic Opioids

Synthetic and semi-synthetic opioids are agonists of different subclasses of the opioid receptors, offering analgesic and sedative effects [184]. Their standard structural features include a basic nitrogen atom (tertiary amine), an aromatic (heteroaromatic) ring, and polar groups, such as amide or phenolic/carbonylic. Opioids are polar compounds, and their structural characteristics allow for their analysis in a single chromatographic run. The pH of the solution dictates the solubility of a compound in organic and aqueous media. This is due to the presence of basic nitrogen, which allows liquid–liquid extraction (LLE) for their separation in various samples. Diversification of their structures and the introduction of new compounds led to the opioid epidemic, making it one of the significant public health concerns in North America [185]. Although newly detected opioids are smaller in number, synthetic opioids have a higher risk of fatal intoxication [186].

5.1. Semi-Synthetic Opioids

Semi-synthetic opioids (SSOs) include compounds obtained by chemical modification of naturally occurring compounds. Some representatives of this class include hydromorphone (Figure 5), oxycodone, and oxymorphone. Another rising issue is the pills sold as oxycodone, but counterfeited and illicitly manufactured to look similar to prescription pharmaceuticals, which contain harmful additives or irregular doses [187]. In the study by Nguyen and coworkers, 567 pills, most of which carried a “30M” imprint as 30 mg oxycodone tablets, were examined by GC-MS and GS-FID [188]. Out of this number, fentanyl was identified in 75.4%, while others contained benzodiazepines, other opioids, and their precursors. Usman and coworkers concluded that nanomaterial-based techniques now offer innovative tools for sensitive monitoring of classical opiates and their synthetic analogues, with lower LODs, on-site detection, and specific preliminary analyses, which have to be confirmed by standard chromatographic analysis [189]. Methorphan (Figure 5), a semi-synthetic morphine derivative, is commonly encountered in seized heroin samples. Its higher concentrations lead to effects similar to those of ketamine and phencyclidine. This compound is of particular interest, as its d-isomer is used as an antitussive. At the same time, the l-isomer is a potent narcotic opioid, raising questions about the low restrictions on specific isomers. The GC technique can be applied for the quantification of a particular isomer if a chiral derivatization agent is used, such as (-)-menthyl chloroformate [190]. Salerno et al. also presented the GC-MS examination of 45 heroin samples containing methorphan, and 24 out of 26 compounds in these samples were identified with similarities in the 85–97% without the need for derivatization [191]. The methorphan isomers were quantified by enantioselective HPLC-MS/MS.

Figure 5.

Chemical structures of selected semi-synthetic opioids.

In 2021, two opioids related to methadone, a commonly prescribed analgesic, appeared on the drug market. The first one is dipyanone (Figure 5), a compound investigated for the analgesic activity comparable to methadone in the mid-20th century [192]. It was first identified in seized samples in Germany, followed by Slovenia and the USA. Desmethylmoramide (Figure 5), a second compound, was also discovered in Germany. This compound is structurally related to moramide, a controlled opioid [193]. As both compounds are related to the prescription opioids, their harm potential as NPS is poorly understood. Vandeputte and coworkers performed GC-MS analysis of dipyanone without derivatization, with the molecular ion located at 335 m/z and the pyrrolidino ring mass fragment at 98 m/z [194].

5.2. Fentanyl and Its Analogues

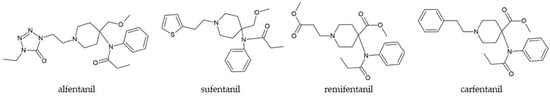

The increase in the consumption of fentanyl and its analogues created epidemic-level harm in some countries, as shown in references [195,196]. The constant increase in newly identified fentanyl-related opioids is evident, especially after 2009, when more than ten new compounds were reported each year [197]. Fentanyl, the most prominent synthetic opioid, has been synthesized and used since the 1960s. This compound is 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine. The structural features of fentanyl, based on the main chain of phenethyl piperidine, allow for different modifications, leading to a large group of compounds called “fentanyls” [197]. Unlike other groups of NPSs, fentanyl and some of its analogues are used in human and veterinary medicine for anesthesia, pain control in postoperative surgical procedures, and cancer, but there is also a long history of abuse [198,199]. Some of the examples of fentanyl derivatives are alfentanil, sufentanil, remifentanil, and carfentanil, and their structures are shown in Figure 6 [200]. So far, efforts by various government drug enforcement agencies to bring it under control have had limited success due to its availability and profitability [201]. The precursors for fentanyls are readily available, and the synthesis procedures are relatively straightforward [202]. Fentanyl is commonly encountered mixed with other natural and synthetic controlled substances, and even sold as “fake Norco” or MDMA [203,204].

Figure 6.

Chemical structures of selected fentanyl derivatives.

Several different methodologies have been developed for the identification and quantification of fentanyl and its analogues. Commonly used methods include GC-MS and LC-MS/MS for the analysis of these compounds in biological samples. GC-MS is used routinely [205] for the identification of compounds, their precursors, and metabolites with great success, as shown in the review by Valdez [197]. The preprocessing of fentanyls for GC-MS analysis, including derivatization, makes the examination cumbersome and limits rapid detection. The detection limits are relatively high, increasing the risk of false negatives. Therefore, the importance of LC-MS/MS instrumentation is rising, as the method allows for high sensitivity and precision, high turnaround time, and a wide detection range [206,207]. The main drawback is the large volume of organic solvents required for analysis, especially when samples, such as hair, are hydrolyzed. Often, the lack of drug matrix references lowers the reliability and traceability of the obtained results [208].

When GC-MS is selected for fentanyl analysis, the critical step is sample preparation, as very low quantities are typically present in complex matrices. SPE is usually chosen for purification from the matrix, while LLE in phosphate buffer at pH 5–8.4 is the most widely used method for fentanyls, as outlined in the review paper by Carelli and coworkers [184]. Standard extraction techniques, such as SPE and LLE, are time-consuming and require large volumes of organic solvents. Therefore, microextraction techniques are constantly being developed for the analysis of biological samples. Ares-Fuentes and coworkers presented results of the fabric-phase sorptive microextraction (FPSE) and GC-MS analysis of nine fentanyl analogues in oral fluid [196]. The LOD and LOQs for these compounds were 1–15 ng/mL and 5–50 ng/mL, respectively, with recovery rates ranging from 94.5% to 109.1%.

Camedda et al. developed the first GC-MS procedure for the quantification of fentanyl and butyryl fentanyl with an LOQ of 1 ng/mL in oral fluid [209]. Sisco and coworkers obtained results on the application of fentanyl-targeted GC-MS separation of 11 analogues [210]. They concluded that the targeted analysis was up to 25 times more sensitive, and the retention time differences were increased by a factor of two. Gilbert et al. applied PCA and hierarchical clustering to EI-MS data for fentanyls, achieving 91% accuracy. The compounds were grouped based on the positions of modifications and chemical groups introduced into the structure, highlighting the importance of statistical tools in NPS identification [144]. Gilbert and coworkers proved that presumptive tests based on Eosin Y have the potential to detect a wide range of fentanyl derivatives [211]. Their results were confirmed by the GC-MS analysis, which was able to discriminate between 18 fentanyl-derived synthetic opioids after their dissolution in methanol within 20 min. The LOD and LOQ values were 0.007–0.822 µg/mL and 0.023–2.742 µg/mL.

Forensic coursework often involves the examination of non-standard samples. Vladez et al. described a method for fentanyl, acetyl fentanyl, and their metabolites in soil by the GC-MS technique [212]. Examination of these SO and metabolites in environmental samples can link the site to the illicit production of these compounds [213]. Active compounds were extracted from the soil using ethyl acetate, then reacted with 2,2,2-trichloroethoxycarbonyl chloride (Troc-Cl) to generate the modified compounds. The LOQ values obtained in this study were expressed in nanograms per milliliter of sample. Additionally, fentanyl and related compounds were examined using the same method from silt, a complex matrix due to its high water content and chemical impurities that shield analytes from derivatization agents [95], and from clay [214]. Valdez et al. used the same derivatization agent for urine and plasma samples spiked with fentanyl and acetyl fentanyl. They concluded that 2-phenylethyl chloride was detectable only by GC-MS, and not by LC-MS [215]. This compound is important as the second reaction product, which is crucial for determining the original opioid [216]. It is important to mention that fentanyls undergo similar fragmentation in mass spectra, including piperidine ring degradation, dissociation of phenethyl and piperidine rings, and cleavage of the piperidine ring and amide moiety. However, some differences were observed depending on the ionization mode [217]. Although similar, the fragmentation pathways depend on the substituent position and enable the differentiation of compounds, as observed in the mass spectra of fentanyl and acetyl fentanyl [70]. This allows for the structural elucidation of features when new compounds are encountered. In the paper by Wei and Su, nine fentanyl drugs were examined in hair samples, extracted by sonication and centrifugation, with the linear range between 0.5 and 5.0 ng/mg, with the detection limits between 0.02 and 0.05 ng/mg [208]. Another advancement in the analysis of fentanyls was described in a paper by Leary and coworkers, which presented the capabilities of a GC-MS instrument [218]. Out of 250 compounds (210 of which were fentanyl analogues), 90% were successfully detected onboard. These results might have a significant impact on the field analysis of illicit drugs.

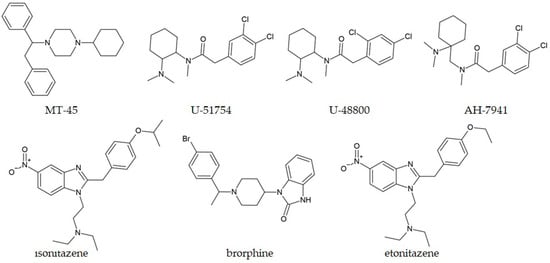

5.3. Non-Fentanyl Compounds

A special class of synthetic opioids includes non-fentanyl compounds, belonging to piperazines (MT-45) and benzamides (U-50488, U-47700, U-69593, and AH-7941) [219,220]. The structures of representative compounds are shown in Figure 7. Most of these compounds were synthesized as analgesics that did not enter clinical trials. “U-compounds”, such as U-50488 and U-47700, were developed by the Upjohn Company in the 1970s and 1980s for their therapeutic properties [221]. These compounds possess desirable opioid effects, for example, euphoria and pain relief [222] with activity that is ten times higher than that of morphine in laboratory animals. A detailed review by Baumann and coworkers covers the pharmacological and structural features of these compounds [221]. The second group of non-fentanyl compounds is labeled as “AH-compounds”, and they include N-substituted cyclohexylmethylbenzamides [223]. These compounds were also discarded during the drug development because of unsatisfying results of drug tests, mainly due to severe side effects or increased potency [224]. MT-45 emerged in 2013. It is chemically similar to fentanyl and has a high analgesic effect [225,226]. Low cost of production and presence on the Internet as a “legal opioid” make MT-45 attractive to the illicit market. There are reports of this compound being mixed with methylone and sold as “wow” [226].

Figure 7.

Chemical structures of selected non-fentanyl compounds.

Pereira et al. discussed that the GC-MS technique alone was not sufficient for a definitive answer for the characterization of an unknown substance, as two matches were found in the mass spectra library (U-51754 and U-48800) [227]. NMR spectra and molecular dynamics simulations were also performed to elucidate the structural features of the unknown substance (U-48800) (Table 3). They concluded that bioinformatic tools are valuable in forensic research, especially when reference materials are unavailable. Uchiyama and coworkers identified MT-45 together with other NPSs in chemical and herbal products bought via the Internet by GC-MS, and further examined by other techniques [228].

Benzimidazole synthetic opioids are a special class of synthetic opioids, with activity that often exceeds that of fentanyl [229]. These compounds were developed by the Swiss chemical company in the late 1950s, but they have never been used in clinical practice. In 2020, Verougstraete et al. reported, for the first time, intoxication by brorphine (Figure 7), a piperidine benzimidazolone derivative, and characterized its structure from a powder sample obtained from a patient seeking medical help [230]. This compound is outside the scope of generic legislation, although the opioid activity of this class of compounds was reported in 1967 [230]. Another benzimidazole derivative, isotonitazene (Figure 7), was identified by GC-MS in 2019 by Blanckaert and coworkers [231]. The compound was sold online as white powder and marketed as etonitazene (Figure 7), a compound with a reported potency of a hundred to a thousand times that of morphine [232]. Biological studies involving isotonitazene showed its high potency and efficacy, labeling it as a potent opioid. The identification of isonitazene from nitazene, a structural isomer and a member of the benzimidazole opioid family, was difficult in the electron ionization mass spectra upon separation by GC, as concluded by Kanamori et al. [233]. The characteristic fragmentation in LC-MS allowed these compounds to be distinguished from one another.

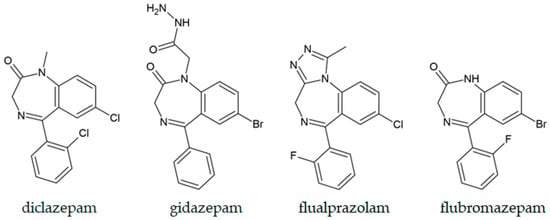

5.4. Benzodiazepines