Abstract

Ultrasonic-assisted maceration and supplementation with glutathione-enriched inactive dry yeast (g-IDY) represent promising strategies to optimize the quality of fermented fruit wines. This study systematically investigated the synergistic effects of combined ultrasonic treatment and g-IDY addition on the metabolomics, flavoromics, and antioxidant properties of kiwifruit wine (KW), using integrated 1H-NMR, GC-MS, gas chromatography–ion mobility spectrometry (GC-IMS), and radical scavenging assays. 1H-NMR analyses revealed that both individual and combined treatments significantly altered the KW metabolome, influencing the levels of amino acids, organic acids, and carbohydrates. GC-MS and GC-IMS analyses characterized numerous volatile compounds, demonstrating that the combined treatments (USL + GSH, USM + GSH, USH + GSH) particularly enhanced the concentrations of desirable fruity esters (e.g., ethyl isobutyrate) and reduced off-flavor compounds (e.g., hexanoic acid), exhibiting a clear synergistic effect beyond individual applications. Furthermore, the combined treatment significantly enhanced the antioxidant capacity of KW, as evidenced by the significantly higher scavenging activities against DPPH, hydroxyl, and superoxide anion radicals, compared to individual applications. Overall, this study sheds light on applying the synergistic treatment of ultrasonics and g-IDY as a novel technique to comprehensively enhance the flavor and functional quality of KW.

1. Introduction

Kiwi wine (KW), which is produced through the fermentation of fresh kiwifruit (Actinidia spp.), has attained considerable commercial popularity owing to its appealing sensory profile—characterized by freshness, well-balanced sweetness, and a delicate vinous aroma—as well as its bioactive [1]. As key factors in quality optimization, enhancing flavor and antioxidant properties of KW not only facilitate KW producers, but also favorite by consumers.

Glutathione-enriched inactive dry yeast IDY (g-IDY) has been proved that can either release GSH directly into wine and/or provide precursors for GSH synthesis, thereby increasing GSH content in the wine [2]. Glutathione (GSH)—a tripeptide consisting of L-glutamate, L-cysteine, and glycine—contributes to the preservation of desirable aromatic compounds, suppresses the development of off-flavors, and inhibits the formation of browning pigments [3,4,5]. Additionally, g-IDY has been observed to release complex nitrogen-containing volatile compounds into wine, influencing its aroma profile [6]. In our previous study, the addition of g-IDY was shown to significantly reduce the concentration of hexyl acetate while increasing the levels of 1-hexanol-M and pentanal in KW produced from both green- and yellow-fleshed kiwifruit [7].

As a maceration technology, ultrasonic-assisted maceration offering reduced energy consumption and minimized solvent usage, while maintaining extraction efficacy [8]. Till now, ultrasonic-assisted maceration has been widely applied to grape wine production, by improving the speed of phenolic compounds transfer from grape pomace tissues to wine [9,10,11]. Meanwhile, Yang et al., has found that increasing both ultrasonic power (at a fixed 40 min duration) and treatment time (at a fixed 240 W power) significantly lowers the epicatechin level in KW, thereby improving its taste and mouthfeel [7].

Based on these findings, we hypothesized that the combination of ultrasonic maceration and g-IDY supplementation would exert a synergistic effect, not only by improving the extraction efficiency of beneficial compounds but also by modulating yeast metabolic activity during fermentation, thereby comprehensively enhancing the flavor and functional properties of KW. To fulfill the above gaps, this study aims to investigate the combined application of g-IDY and ultrasound technology in KW processing, evaluating its impact on the flavor profile and antioxidant properties, with the goal of providing a novel approach for quality enhancement in KW production. Owing to the complexity of KW flavor profile, GC-MS and GC-IMS were applied, attributing to their extensive spectral libraries for identification and excellent trace-level sensitivity, respectively.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials and Fermentation Protocol

All kiwifruits used in this study were transported to the laboratory immediately after harvest. Upon arrival, they were subjected to pretreatment, which involved cleaning, peeling, and crushing. Enzymatic digestion was then performed using pectinase (0.02 g/L, 100,000 U/g, SAS SOFRALAB, Magenta, France) for 2 h. The enzyme digestion temperature was con-trolled at 40 °C by an HH-8 thermostatic water bath (GUOHUA INSTRUMENT MANU-FACTURING Co., Ltd., Changzhou, China). Subsequently, potassium metabisulfite (70 mg/L, Shanghai Yuanye Bio-Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) was added to prevent browning, and sucrose was incorporated to adjust the initial sugar content to 23 °Brix. The addition rate of Saccharomyces cerevisiae RW (Angel Yeast Co., Ltd., Wuhan, Hubei, China) was 0.2 g/L. Group settings are as follows:

- (1)

- CON: Control group, without ultrasonic treatment and g-IDY addition;

- (2)

- GSH: g-IDY (0.25 g/L) added before fermentation;

- (3)

- USL: 240 W ultrasonic treatment 40 min before fermentation;

- (4)

- USL + GSH: 240 W ultrasonic treatment 40 min and g-IDY addition before fermentation;

- (5)

- USM + GSH: 360 W ultrasonic treatment 40 min and g-IDY addition before fermentation;

- (6)

- USH + GSH: 480 W ultrasonic treatment 40 min and g-IDY addition before fermentation.

Fermentation was carried out in a total volume of 200 mL at 25 ± 1 °C for 30 days, employing a DHP-9162D thermostat (Keelrein Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). Subsequently, the KW samples were filtered through three layers of sterile gauze and stored at −80 °C pending further analysis.

2.2. GC-IMS Analysis

Gas chromatography–ion mobility spectrometry (GC-IMS) instrument (Flavourspe®, G.A.S. Dortmund Company, Dortmund, Germany) was conducted a Restek MXT-5 column (30 m × 0.53 mm × 1 μm) was employed in GC, with the column and IMS temperatures set at 60 °C and 45 °C, respectively. Sample preparation involved transferring 1.5 mL aliquots into a 20 mL headspace glass sampling vial, spiked with 10 μL 2-octanol as internal standard (1 μg/mL in ethanol, chromatographic grade; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) for semi-quantitative analysis. The program settings are referred to Zhang et al. [12]. Compound identification was performed by matching the acquired mass spectra against the NIST 2020 library and aligning the ion mobility separation (IMS) migration times. Quantitative analysis was conducted using normalized peak area ratios relative to the internal standard. All analyses were conducted in triplicate (n = 3).

2.3. GC-MS Analysis

A 5 mL aliquot of each KW sample was transferred in a headspace vial with a volume of 20 mL. For semi-quantitative assessment of the aroma profile, 2-octanol (1 μg/mL in chromatographic-grade ethanol; Solarbio, Beijing, China) served as the internal standard. Volatile compounds were examined using a Thermo ISQ™ 7610 GC–MS system (Thermo Fisher Co., Ltd., Waltham, MA, USA) equipped with an autosampler. Headspace extraction was carried out with a DVB/CAR/PDMS (50/30 µm) SPME fiber. Prior to use, the fiber was reconditioned at 250 °C for 10 min. Samples were equilibrated at 50 °C for 15 min, after which the fiber was exposed to the vial headspace to adsorb volatile analytes. Extraction proceeded for 30 min under agitation at 300 rpm. The captured volatiles were then introduced into the system for analysis.

The chromatographic column used for GC–MS was a TG-WAXMSB (30 m × 0.25 mm, 0.25 µm). The program settings refer to previous studies [13]. Volatile compounds were qualified by comparing the experimental mass spectra with the NIST 14 mass spectral library. Volatile compounds were quantified using the ratio of peak area of the volatile compound to the peak area of the 2-octanol internal standard. Each group underwent three replicates.

2.4. 1H-NMR Analysis

Proton NMR (1H-NMR) measurements were performed according to a previously reported method, with slight adjustments [14]. Briefly, 0.5 mL of each KW sample was centrifuged at 18,630× g for 15 min at 4 °C. The resulting supernatant (0.35 mL) was then combined with an equal volume of bi-distilled water (0.35 mL) and 200 μL of a 10 mM TSP solution (3-trimethylsilyl propionic-2,2,3,3-d4 acid sodium salt). The mixture was subjected to a second centrifugation using the same parameters.

1H-NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker AVANCE III spectrometer (600.13 MHz; Wuhan, China) at 298 K. Data acquisition used a CPMG pulse sequence with solvent-signal suppression. The instrumental settings included a 32 k FID size, a spectral window of 12 ppm, 16 dummy scans, an acquisition time of 2.28 s, and a relaxation delay (d1) of 5 s.

Pre-processing and phase correction of the NMR spectra were carried out using Topspin 3.1, with TSP used both as the internal quantitative reference and for spectral calibration. Metabolite concentrations were obtained from the integrated areas of their respective resonances, which were extracted through global spectral deconvolution performed with MestReNova (version 14.2.0-26256; Mestrelab Research S.L., Santiago de Compostela, Spain). During processing, a line-broadening factor of 0.3 was applied, and baseline correction was executed using the Whittaker Smoother algorithm. Metabolite identification was achieved by matching chemical shifts and signal multiplicities against the reference spectra included in the Chenomx library (version 8.3, Chenomx Inc., Edmonton, AB, Canada). Signal integration for each metabolite was done using rectangular integration. To correct for dilution effects and improve comparability across samples, probabilistic quotient normalization (PQN) was applied to the spectral data.

2.5. Antioxidant Activity Analysis

The antioxidant activity of KW was determined with DPPH radical scavenging activity, hydroxyl radical scavenging activity, and superoxide anion radical (O2•) scavenging activity, reference to the methods used in previous studies [15].

2.6. Statistical Analysis

All computational procedures and principal component analysis (PCA) modeling were implemented in R (version 4.4.2, R Core Team). Prior to univariate analyses, data distributions were transformed for normality using Box and Cox methods [16]. T-test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey HSD post hoc test (p < 0.05) was used to determine significant differences among groups. Radar charts were generated through the online platform Chiplot (version 2.3.2, https://www.chiplot.online/ (accessed on 12 August 2025)).

3. Results

3.1. Metabolomic and Flavor Profiles of KW

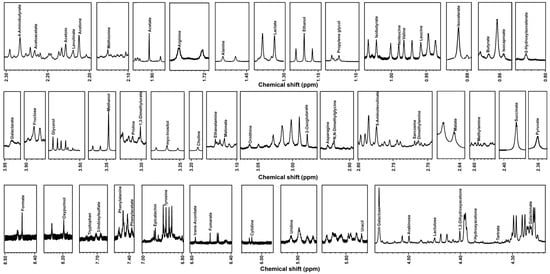

As shown in Figure 1, a total of 61 water soluble molecules were detected by 1H-NMR, including alcohols and polyols (5), amino acids, peptides, and analogues (15), carbohydrates and carbohydrate conjugates (4), organic acids and derivatives (21), and miscellaneous (16), as shown in Table S1.

Figure 1.

The represented portions of 1H-NMR spectrum of KW samples.

In terms of volatile compounds, 27 VOCs were present in the samples detected by GC-IMS, including esters (21), alcohols (6), aldehydes (1), acids (2), and others (2), as shown in Table S2. Moreover, 27 VOCs were present in the samples detected by GC-MS, including esters (10), alcohols (9), aldehydes (1), acids (4), and others (3), as shown in Table S3.

3.2. Effect of g-IDY Addition on Metabolomic and Volatile Profiles of KW

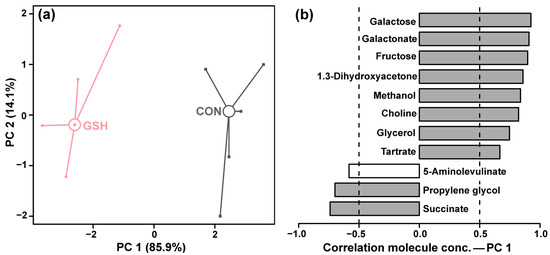

PCA of the 1H-NMR metabolomic profiles revealed a distinct separation between CON and GSH along the first principal component (PC1). As shown in Figure 2a, PC1, which accounted for 85.9% of the total explained variance, clearly discriminated between the two groups. The loadings plot for PC1 (Figure 2b) was analyzed to identify the metabolites responsible for this pronounced separation. The plot indicates that compounds such as galactose, galactonate, fructose, 1,3-dihydroxyacetone, methanol, choline, glycerol, and tartrate were positively correlated with PC1, suggesting their relative abundance was higher in the GSH group. Conversely, metabolites including 5-aminolevulinate, propylene glycol, and succinate showed a strong negative correlation with PC1, indicating their concentrations were higher in CON group.

Figure 2.

PCA model based on the molecules showing significant differences between GSH and CON. In the score plot (a), the two groups of samples are represented by squares (CON), circles (GSH). Wide, empty circles represent the median for each group. The loadings plot (b) shows the importance of each molecule in determining the position of the samples in the score plot. Gray bars indicate significant correlations (p < 0.05) between the molecule’s concentrations and their importance over PC 1.

A clear and significant separation between CON group and GSH group was observed along PC1 in the scores plot (Figure 3a). PC1 captured a dominant 94.8% of the total variance, indicating that the addition of g-IDY alone induced a profound and comprehensive shift in the volatile composition of KW. PC2 accounted for a minor portion (5.2%) of the variance. The loadings plot for PC1 (Figure 3b) revealed the specific aroma-active compounds driving this separation.

Figure 3.

PCA model based on flavor profiles detected in KW using GC-MS and GC-IMS. Score plot (a). Loadings plot (b).

3.3. Effect of Ultrasonic Treatments on Metabolomic Profile in KW

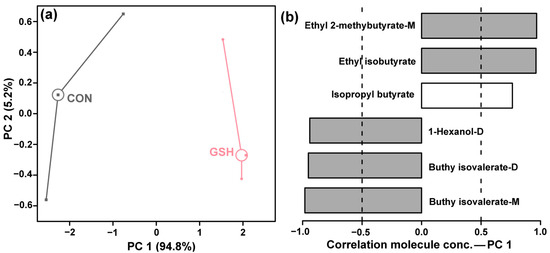

PCA was similarly employed to evaluate the metabolic impact of ultrasonic treatment alone compared to the control group. A pronounced separation between CON and USL groups was observed along PC1 in Figure 4a. PC1 captured a dominant 93.1% of the total metabolic variance, indicating a very strong effect of ultrasonic maceration on the wine’s metabolome. PC2 explained a minor portion of the variance (6.9%).

Figure 4.

PCA model based on the molecules showing significant differences between USL and CON. In the score plot (a), the two groups of samples are represented by squares (CON), circles (USL). Wide, empty circles represent the median for each group. The loadings plot (b) shows the importance of each molecule in determining the position of the samples in the score plot. Gray bars indicate significant correlations (p < 0.05) between the molecule’s concentrations and their importance over PC 1.

The loadings analysis for PC1 (Figure 4b) revealed the specific metabolites driving this separation. The concentrations of phenylalanine, tyrosine, leucine, choline, oxypurinol, uridine, and lactulose were positively correlated with PC1, showing a notable increase in the USL group. In contrast, the level of 5-aminolevulinate was negatively correlated with PC1, indicating its relative decrease following ultrasonic treatment. Acetone also exhibited a negative correlation, though to a lesser extent.

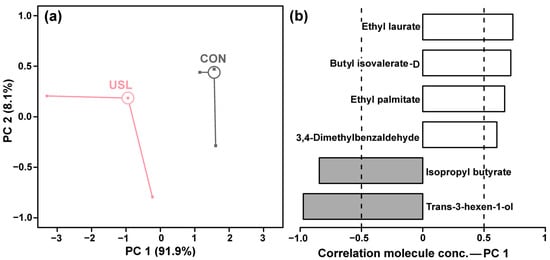

GC-MS and GC-IMS confirmed the substantial impact of ultrasonic maceration on the volatile composition of KW. PCA revealed a clear separation between CON and USL groups along PC1, which accounted for 91.9% of the total variance (Figure 5a). PC2 explained an additional 8.1% of the variance.

Figure 5.

PCA model based on VOCs detected in KW using GC-MS and GC-IMS. Score plot (a). Loadings plot (b).

The loadings plot for PC1 (Figure 5b) identified specific volatile compounds responsible for this separation. Several esters showed strong positive correlation with PC1, including ethyl laurate, butyl isovalerate-D, ethyl palmitate, and isopropyl butyrate, indicating significantly increased concentrations of these compounds in the ultrasonically treated wines. Additionally, 3,4-dimethylbenzaldehyde also exhibited positive correlation with PC1. In contrast, trans-3-hexen-1-ol showed a strong negative correlation with PC1, suggesting decreased levels of this compound following ultrasonic treatment.

3.4. Effect of Different Ultrasonics Powers on the Metabolomic and Flavor Profiles in KW

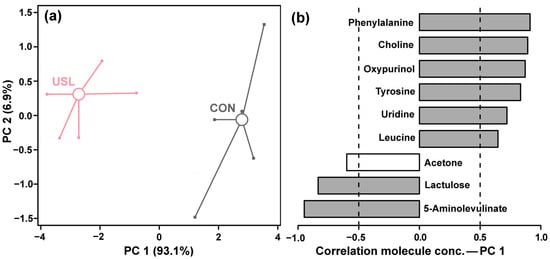

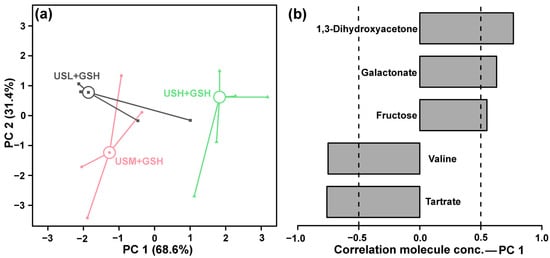

To investigate the synergistic effect of g-IDY and ultrasonic maceration, the metabolic profiles of KW produced with a combination of both treatments under different power levels (240, 360, and 480 W) were analyzed. PCA revealed a clear separation among the three treatment groups primarily along PC1, which explained 68.6% of the total metabolic variance (Figure 6a). PC2, accounting for 31.4% of the variance, further resolved the differences, particularly for the group treated at 480 W (USH + GSH), suggesting a dose-dependent effect of ultrasonic power on the metabolome when combined with g-IDY.

Figure 6.

PCA analysis of KW metabolome produced under g-IDY addition synergized with ultrasonic maceration. Score plot (a). Loadings plot (b).

The loadings plot for PC1 (Figure 6b) was examined to identify the key metabolites driving this separation. Compounds such as 1,3-dihydroxyacetone, galactonate, fructose, exhibited a strong positive correlation with PC1. In contrast, valine and tartrate showed a significant negative correlation.

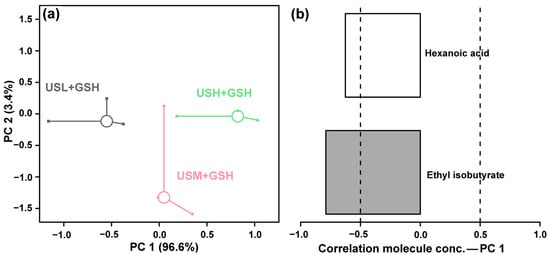

To elucidate the synergistic effect of ultrasonic maceration and g-IDY addition on the flavor profile, the volatile compounds of KW produced under three different ultrasonic power levels (240, 360, and 480 W), all with g-IDY addition, were analyzed by GC–MS and GC-IMS. PCA revealed a clear dose-dependent separation along PC1 among the three treatment groups (Figure 7a). PC1 captured an overwhelming 96.6% of the total variance in the volatile dataset, highlighting that ultrasonic power is a decisive factor in shaping the aroma profile even when g-IDY is present. PC2 accounted for a minor 3.4% of the variance.

Figure 7.

PCA analysis of KW flavor produced under g-IDY addition synergized with ultrasonic maceration. Score plot (a). Loadings plot (b).

The loadings plot for PC1 (Figure 7b) was critical for identifying the key aroma-active compounds driving this separation. The analysis indicated that the concentrations of ethyl isobutyrate and hexanoic acid were negatively correlated with increasing ultrasonic power in the presence of g-IDY.

3.5. Antioxidant Profiles

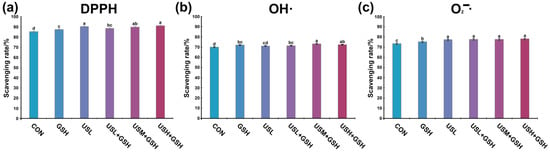

Evaluation of the antioxidant capacity through three distinct radical scavenging assays revealed significant differences among the treatment groups (Figure 8). The CON group consistently demonstrated the lowest radical scavenging activity across all three assays.

Figure 8.

Antioxidant capacity of kiwifruit wines under different treatments. (a) DPPH radical scavenging activity. (b) Hydroxyl radical (OH•) scavenging activity. (c) Superoxide anion radical (O2−•) scavenging activity. Different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) among groups.

For the DPPH radical scavenging rate, the individual treatments significantly enhanced DPPH scavenging capacity compared to CON (p < 0.05). The activity increased with ultrasonic power, yielding the order USH > USM > USL. The synergistic treatment by ultrasonics and g-IDY achieved the highest scavenging rate, which was significantly greater than all other groups (p < 0.05).

For the hydroxyl radical (OH•) scavenging activity, a similar trend was observed for •DH scavenging. All treated wines showed significantly higher activity than CON. The GSH group also showed markedly improved scavenging. In the group treated with ultrasonication and g-IDY in combination, the USM + GSH group exhibited the highest activity. Notably, the synergistic treatment by ultrasonics and g-IDY again resulted in the most potent effect, significantly outperforming even the highest single treatments.

For the superoxide anion radical (O2•−) scavenging activity, the capacity to scavenge O2•− was also significantly enhanced by the treatments. Ultrasonic processing again showed a power-dependent effect (USH > USM > USL > CON). Nevertheless, in the group synergistically treated with ultrasound and g-IDY, the superoxide anion scavenging activity did not exhibit significant differences with increasing ultrasound frequency.

The significantly improved antioxidant capacity across all three assays confirms that both ultrasonic maceration and g-IDY supplementation are effective strategies for enhancing the bioactive quality of KW. More importantly, the consistent superiority of the combined treatment demonstrates a clear synergistic interaction between physical processing technology and biochemical supplements.

The enhancement from ultrasonic treatment alone, which exhibited a power-dependent effect, can be primarily attributed to improved extraction efficiency. The cavitation effects disrupt plant cell walls more thoroughly at higher power levels, facilitating the release of bound phenolic compounds, flavonoids, and other native antioxidants from the kiwifruit pulp into the wine. This physical mechanism aligns with our earlier 1H-NMR findings, which showed altered levels of various metabolites, indicating enhanced extraction.

The efficacy of the g-IDY (GSH) treatment stems from the direct contribution of glutathione, a potent intracellular antioxidant, and its role in sustaining redox stability during fermentation. g-IDY may also supply peptides and amino acids that act as antioxidant precursors or synergists.

4. Discussion

The aims of the study were to test our hypothesis, which is the combination of ultrasonic maceration and g-IDY supplementation would exert a synergistic effect, not only by improving the extraction efficiency of beneficial compounds but also by modulating yeast metabolic activity during fermentation, thereby comprehensively enhancing the flavor and functional properties of KW.

Amino acids, commonly present in KW, significantly influence their taste profile [17]. According to 1H-NMR results, ultrasonic treatment alone (USL) markedly elevated the concentrations of amino acids including phenylalanine, tyrosine, and leucine. This increase may further promote the formation of related aldehydes, higher alcohols, and volatile fatty acids. In contrast, under combined treatments (USL + GSH, USM + GSH, USH + GSH), the content of certain amino acids such as valine decreased. Branched-chain amino acids such as valine and leucine contribute to bitterness and act as key precursors for the synthesis of volatile aroma compounds by yeast during alcoholic fermentation [18]. Specifically, valine can be transformed into isobutyraldehyde, isobutanol, and isobutyric acid via the Ehrlich pathway. The decline in valine under combined treatments is likely due to enhanced conversion into volatile compounds, thereby mitigating undesirable flavors in kiwifruit wine.

Sugars represent a critically studied class of compounds in KW systems [19]. They function not only as the primary substrate for yeast alcoholic fermentation—directly influencing fermentation kinetics and ethanol yield—but also fundamentally define the KW wine’s sensory character by establishing the sweet baseline and interacting with acidity, tannins, and aroma-active compounds to shape overall flavor balance. 1H-NMR analysis revealed that the GSH group increased the levels of fructose, galactose, and 1,3-dihydroxyacetone. This suggests that g-IDY, as inactivated yeast, contributes residual sugars and glycolytic intermediates in addition to glutathione. 1,3-dihydroxyacetone, an intermediate in glycolysis, reflects modulated sugar metabolism activity in yeast. These carbohydrates may also serve as substrates for secondary reactions, such as esterification.

Organic acids are fundamental to KW wine acidity, pH, and sensory structure [20]. Using 1H-NMR, 21 organic acids and derivatives were identified, with notable variations among treatments. the GSH group reduced succinic acid content. As one of the principal acids generated by yeast metabolism, succinic acid imparts sour, salty, and bitter notes and has a low sensory threshold (~35 mg/L) [21]. Elevated levels can adversely affect wine quality. The glutathione in g-IDY may exert antioxidant effects that redirect yeast metabolism, suppressing succinate accumulation [22]. The combined application of ultrasound and g-IDY led to a reduction in tartaric acid content. Tartaric acid, the most stable acid in wine and a major contributor to perceived acidity, is resistant to microbial degradation [23]. Overall, the combined treatments (USL + GSH, USM + GSH, USH + GSH) optimized the organic acid profile by adjusting the ratios of key acids such as succinic and tartaric acid, thereby improving acidity balance, reducing potential bitterness, and enhancing freshness.

Alcohols, largely derived from yeast metabolism during fermentation, are crucial for wine aroma and ester formation [24]. Higher alcohols—volatile compounds with more than two carbon atoms—are particularly influential. Their concentrations depend on yeast activity, wine style, and chemical makeup [25]. GC-IMS analysis detected multiple alcohols whose variations significantly affected the aromatic profile. The USL group alone reduced the content of trans-3-hexen-1-ol, a compound with a grassy character. Its decrease favored a shift toward ripe fruit notes, improving overall aroma appeal.

Esters are key determinants of fruity aroma in fruit wines and serve as important markers of flavor quality [26]. Formed mainly through yeast enzymatic activity and bacterial metabolism during fermentation, they define the aromatic signature. Esters were the dominant volatile class in KW samples [27]. The USL group significantly enhanced several esters, including ethyl laurate (sweet) and butyl isovalerate (fruity), likely by improving the release and reactivity of esterification precursors—organic acids and alcohols.

The most pronounced positive effects were observed in combined treatments (USL + GSH, USM + GSH, USH + GSH). Ethyl isobutyrate, which exhibits intense fruitiness [28], increased notably with ultrasonic power. This correlation suggests that higher ultrasound intensities enhance esterification efficiency or potentiate g-IDY-driven enzymatic processes, leading to elevated synthesis of desirable fruit esters [7]. These findings align with ultrasound’s known role in intensifying reaction kinetics and precursor mobilization.

Thus, the integration of physical extraction (US) and biochemical modulation (g-IDY) creates a synergistic regime: ultrasound enriches precursor availability, while g-IDY likely supports yeast ester synthesis via cofactor supply or redox stabilization, collectively yielding a more complex and intense fruity aroma.

A notable functional outcome of this study is the enhancement of antioxidant capacity. Ultrasound facilitates the extraction of native kiwifruit antioxidants, such as polyphenols and flavonoids, via cell disruption [29]. Meanwhile, g-IDY directly introduces glutathione—a potent endogenous antioxidant—and helps sustain redox homeostasis during fermentation, minimizing oxidative degradation of bioactive compounds [6]. The combined treatments exhibited clear synergy, demonstrating superior radical scavenging activity in DPPH, hydroxyl radical, and superoxide anion assays compared to individual treatments. This confirms that the joint application of ultrasound (physical) and g-IDY (biochemical) yields a synergistic improvement in the health-promoting properties of KW.

The strong negative loading for hexanoic acid is particularly significant for quality optimization. This compound can contribute to undesirable sensory attributes at elevated concentrations [30]. Its reduction suggests that the combined treatment, especially at higher power levels, may suppress the metabolic pathways leading to its formation or promote its conversion into other compounds, such as ethyl esters, thereby mitigating potential off-flavors and refining the overall aroma balance.

This powerful synergy indicates that ultrasonic power can be precisely calibrated alongside g-IDY addition to steer the fermentation and extraction processes toward a targeted flavor profile. Optimizing this combination is therefore a highly promising strategy for enhancing the sensory quality of KW, effectively increasing the complexity and pleasantness of its aroma while reducing the risk of off-flavor development.

5. Conclusions

The synergistic treatment of ultrasonic maceration and g-IDY supplementation significantly modulated the flavor profile and antioxidant properties of KW. This combined approach enhanced the extraction and biotransformation of volatile and non-volatile compounds, leading to a marked increase in desirable fruity esters and a decrease in potential off-flavor compounds, as revealed by GC-MS, GC-IMS, and 1H-NMR analyses. Furthermore, the combined treatment exhibited a significant synergistic effect in enhancing the antioxidant capacity of KW, as demonstrated by superior radical scavenging activities across all assays (DPPH, OH•, and O2−•). The dose-dependent effect of ultrasonic power level in the presence of g-IDY highlights the potential for precise process optimization. This study establishes that the combination of physical (ultrasound) and biochemical (g-IDY) strategies is a highly effective method for the quality enhancement of KW. Future research should focus on optimizing the treatment parameters and improving the quantification methods for a more comprehensive understanding of flavor component evolution.

Supplementary Materials

The following Supporting Information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/chemosensors13120424/s1, Table S1: The concentrations of molecules (Mean ± sd) characterized by 1H-NMR; Table S2: The concentrations of molecules (Mean ± sd) characterized by GC-IMS.; Table S3: The concentrations of molecules (Mean ± sd) characterized by GC-MS.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.Z. and G.P.; methodology, C.Z. and L.L. (Luca Laghi); formal analysis, X.L. and L.L. (Lu Lin); investigation, X.L. and L.L. (Lu Lin); data curation, C.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, X.L., L.L. (Luca Laghi) and C.Z.; writing—review and editing, X.L., L.L. (Lu Lin), G.P., C.Z. and L.L. (Luca Laghi); supervision, C.Z. and G.P.; project administration, C.Z.; funding acquisition, X.L. and C.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Sichuan Province, grant number 2024NSFSC0364 and the National College Students’ Innovative Entrepreneurial Training Program, grant number S202510656118.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the study findings are available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhou, Y.; Fei, G.; Faridul Hasan, K.M.; Kang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Li, H.; Zhou, S. Cultivar Difference Characterization of Kiwifruit Wines on Phenolic Profiles, Volatiles and Antioxidant Activity. Food Chem. X 2023, 18, 100691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kritzinger, E.C.; Stander, M.A.; Du Toit, W.J. Assessment of Glutathione Levels in Model Solution and Grape Ferments Supplemented with Glutathione-Enriched Inactive Dry Yeast Preparations Using a Novel UPLC-MS/MS Method. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2013, 30, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonni, F.; Clark, A.C.; Prenzler, P.D.; Riponi, C.; Scollary, G.R. Antioxidant Action of Glutathione and the Ascorbic Acid/Glutathione Pair in a Model White Wine. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 3940–3949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomašević, M.; Gracin, L.; Ćurko, N.; Kovačević Ganić, K. Impact of Pre-Fermentative Maceration and Yeast Strain along with Glutathione and SO2 Additions on the Aroma of Vitis Vinifera L. Pošip Wine and Its Evaluation during Bottle Aging. LWT 2017, 81, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binati, R.L.; Larini, I.; Salvetti, E.; Torriani, S. Glutathione Production by Non-Saccharomyces Yeasts and Its Impact on Winemaking: A Review. Food Res. Int. 2022, 156, 111333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, L.; Yu, K.; Xiao, X.; Wei, Z.; Xiong, R.; Du, Y.; Li, Y.; Ma, Y. Study on the Kinetic Model of Mixed Fermentation by Adding Glutathione-Enriched Inactive Dry Yeast. Fermentation 2024, 10, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Liu, X.; Song, C.; Hu, B.; Tang, J.; Zhang, S.; Ao, Z.; Zhu, C.; Laghi, L. Effects of Ultrasonic-Assisted Maceration on Flavor, Metabolites and Antioxidant Properties of Kiwi Wine. LWT 2025, 227, 118002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puzovic, A.; Mikulic-Petkovsek, M. Comparative Evaluation of Conventional and Emerging Maceration Techniques for Enhancing Bioactive Compounds in Aronia Juice. Foods 2024, 13, 3255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavahian, M.; Manyatsi, T.S.; Morata, A.; Tiwari, B.K. Ultrasound-Assisted Production of Alcoholic Beverages: From Fermentation and Sterilization to Extraction and Aging. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 5243–5271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Bai, Y.; Chen, Q.; Wang, X.; Duan, C.; Hu, G.; Wang, J.; Bai, L.; Du, J.; Han, F.; et al. Effect of Ultrasonic Treatment during Fermentation on the Quality of Fortified Sweet Wine. Ultrason. Sonochem 2024, 105, 106872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; García, J.F.; Sun, D.W. Advances in Wine Aging Technologies for Enhancing Wine Quality and Accelerating Wine Aging Process. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014, 54, 817–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Ma, J.; Yang, Y.; Deng, J.; Zhu, K.; Yi, Y.; Tang, J.; Jiang, X.; Zhu, C.; Laghi, L. Effects of S. Cerevisiae Strains on the Sensory Characteristics and Flavor Profile of Kiwi Wine Based on E-Tongue, GC-IMS and 1H-NMR. LWT 2023, 185, 115193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Liu, X.; Lan, Q.; Wan, F.; Yang, Z.; Nie, X.; Cai, Z.; Hu, B.; Tang, J.; Zhu, C.; et al. Comparison of Aroma and Taste Profiles of Kiwi Wine Fermented with/without Peel by Combining Intelligent Sensory, Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry, and Proton Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. Foods 2024, 13, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Lan, Q.; Liu, X.; Cai, Z.; Zeng, R.; Tang, J.; Jiang, X.; Zhu, C.; Hu, B.; Laghi, L. Effects of Pretreatment Methods on the Flavor Profile and Sensory Characteristics of Kiwi Wine Based on 1H NMR, GC-IMS and E-Tongue. LWT 2024, 203, 116375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Li, P.; Ma, Y.; Liang, L.; Jia, F.; Wang, Y.; Yu, L.; Huang, W. Extraction of Flavonoids from Black Mulberry Wine Residues and Their Antioxidant and Anticancer Activity in Vitro. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Box, G.E.P.; Cox, D.R. An Analysis of Transformations. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Methodol.) 1964, 26, 211–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, L.; Serratosa, M.P.; Godoy, A.; Fariña, L.; Dellacassa, E.; Moyano, L. Comparison of Physicochemical Properties, Amino Acids, Mineral Elements, Total Phenolic Compounds, and Antioxidant Capacity of Cuban Fruit and Rice Wines. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 9, 3673–3682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xia, Y.; Wang, G.; Tao, L.; Yu, J.; Ai, L. Effects of Boiling, Ultra-High Temperature and High Hydrostatic Pressure on Free Amino Acids, Flavor Characteristics and Sensory Profiles in Chinese Rice Wine. Food Chem. 2019, 275, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyitrainé Sárdy, D.; Kellner, N.; Magyar, I.; Oláhné Horváth, B. Effects of High Sugar Content on Fermentation Dynamics and Some Metabolites of Wine-Related Yeast Species Saccharomyces cerevisiae, S. uvarum and Starmerella bacillaris. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2020, 58, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payan, C.; Gancel, A.-L.; Jourdes, M.; Christmann, M.; Teissedre, P.-L. Wine Acidification Methods: A Review. OENO One 2023, 57, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Pu, D.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, Y. Recent Progress in the Study of Taste Characteristics and the Nutrition and Health Properties of Organic Acids in Foods. Foods 2022, 11, 3408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, M.N.; Aslankoohi, E.; Verstrepen, K.J.; Courtin, C.M. Contribution of the Tricarboxylic Acid (TCA) Cycle and the Glyoxylate Shunt in Saccharomyces cerevisiae to Succinic Acid Production during Dough Fermentation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2015, 204, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.; Zou, M.; Tang, C.; Ao, H.; He, L.; Qiu, S.; Li, C. The Insights into Sour Flavor and Organic Acids in Alcoholic Beverages. Food Chem. 2024, 460, 140676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirst, M.B.; Richter, C.L. Review of Aroma Formation through Metabolic Pathways of Saccharomyces cerevisiae in Beverage Fermentations. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2016, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swiegers, J.H.; Bartowsky, E.J.; Henschke, P.A.; Pretorius, I.S. Yeast and Bacterial Modulation of Wine Aroma and Flavour. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2005, 11, 139–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Styger, G.; Prior, B.; Bauer, F.F. Wine Flavor and Aroma. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 38, 1145–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Ma, Y.; Wan, F.; Cai, Z.; Zeng, R.; Tang, J.; Nie, X.; Jiang, X.; Zhu, C.; Laghi, L. Comprehensive Comparison of Flavor and Metabolomic Profiles in Kiwi Wine Fermented by Kiwifruit Flesh with Different Colors. LWT 2024, 208, 116719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, C.; Kyratzis, A.C.; Soteriou, G.A.; Rouphael, Y.; Kyriacou, M.C. Configuration of the Volatile Aromatic Profile of Carob Powder Milled From Pods of Genetic Variants Harvested at Progressive Stages of Ripening From High and Low Altitudes. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 789169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Vanga, S.K.; Raghavan, V. High-Intensity Ultrasound Processing of Kiwifruit Juice: Effects on the Ascorbic Acid, Total Phenolics, Flavonoids and Antioxidant Capacity. LWT 2019, 107, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittari, E.; Moio, L.; Piombino, P. Interactions between Polyphenols and Volatile Compounds in Wine: A Literature Review on Physicochemical and Sensory Insights. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).