Abstract

Simultaneous detection of multiple neurochemicals and toxic metal ions in real time remains a major analytical challenge in neurochemistry and environmental sensing. In this study, we present a novel, biocompatible, laser-trimmed four-bore carbon fiber microelectrode (CFM) platform capable of ultra-fast, multi-analyte detection using fast-scan cyclic voltammetry (FSCV). Each of the four carbon fibers, spaced nanometers apart within a glass housing, was independently functionalized and addressed with a distinct waveform, allowing the selective and concurrent detection of four analytes without electrical crosstalk. To validate the system, we developed two electrochemical detection paradigms: (1) selective electrodeposition of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) on one fiber for enhanced detection of cadmium (Cd2+), alongside dopamine (DA), arsenic (As3+), and copper (Cu2+); and (2) Nafion-modification of two diagonally opposing fibers for discriminating DA and serotonin (5-HT) from their interferents, ascorbic acid (AA) and 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA), respectively. Scanning electron microscopy and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy analysis confirmed surface modifications and the spatial localization of electrodeposited materials. Electrochemical characterization in tris buffer, which mimics artificial cerebrospinal fluid, demonstrated enhanced analytical performance. Compared to single-bore CFMs, the four-bore design yielded a 28% increase in sensitivity for Cd2+ (147.62 to 190.02 nA µM−1), 12% increase for DA (10.785 to 12.767 nA µM−1), and enabled detection of As3+ with a sensitivity of 0.844 nA µM−1, which was not possible with single-bore electrodes within the mixture of analytes. Limits of detection improved twofold for both DA (0.025 µM) and Cd2+ (0.005 µM), while As3+ was detectable down to 0.1 µM. In neurotransmitter-interference studies, sensitivity increased by 39% for DA and 33% for 5-HT with four-bore CFMs compared to single-bore CFMs, despite modest Nafion diffusion onto adjacent fibers. Overall, our four-bore CFM system enables rapid, selective, and multiplexed detection of chemically diverse analytes in a single scan, providing a highly promising platform for real-time neurochemical monitoring, environmental toxicology, and future integration with AI-based in vivo calibration models.

1. Introduction

The increasing global burden of neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s disease has sparked significant concern in recent years. The number of individuals affected by these disorders has nearly doubled over the past 25 years, and the World Health Organization anticipates that neurodegenerative conditions will become the second leading cause of death worldwide by 2040, surpassing cancer [1,2]. This anticipated rise calls for a deeper understanding of the biological and environmental contributors to disease progression and the development of precise tools to monitor neurochemical changes in real time.

Central to this pathology are neurotransmitters like dopamine (DA) and serotonin (5-HT, or 5-hydroxytryptamine), which are essential for regulating mood, cognition, and motor function [3,4,5,6]. Disruptions in their signaling pathways can severely impair neural communication, contributing to disease progression. Compounding this complexity, recent experimental and theoretical evidence suggests that environmental neurotoxins, particularly toxic heavy metals such as Cd2+, Cu2+, and As3+, can accumulate in brain tissue [5,7,8]. These metals interfere with cellular homeostasis, promote oxidative stress, and accelerate the deterioration of neuronal networks, yet their real-time interplay with neurotransmitters remains poorly understood due to the lack of appropriate sensing tools.

While advances in neurochemical sensing have improved our ability to monitor certain neurotransmitters, capturing rapid, real-time changes under physiologically relevant and dynamic conditions continues to be a challenge. Non-electrochemical techniques such as optogenetics [9] have provided powerful tools for probing neural circuits through targeted stimulation, yet they fall short of offering direct chemical insight and often lack the temporal resolution necessary to track rapid biochemical events. Fast-scan cyclic voltammetry (FSCV) has emerged as a leading method for real-time, in vivo neurotransmitter detection due to its exceptional temporal resolution and sensitivity. Moreover, because of the fast scan rates, FSCV is primarily adsorption-driven [10,11] compared to traditional slow-scan cyclic voltammetry. When coupled with carbon fiber microelectrodes (CFMs), which are ultra-small (5–7 µm), highly conductive, and biocompatible, FSCV allows for minimally invasive measurements within brain tissue [10,12]. In addition to these analytical advantages, CFMs align strongly with the principles of green chemistry. Carbon fibers can be derived from renewable and biodegradable precursors such as lignin and cellulose, reducing dependence on petroleum-based materials [13]. Their fabrication processes often minimize the use of toxic reagents by employing aqueous-based or solvent-free synthesis routes [14]. Moreover, laser trimming and micro-machining techniques allow for precise shaping without generating chemical waste, further lowering the environmental footprint [15]. The electrodes are reusable, require only microliter-scale analyte volumes, and generate negligible chemical waste during operation. Taken together, these features position CFMs as sustainable and environmentally friendly sensing platforms, consistent with the broader goals of green analytical chemistry. However, most FSCV studies to date have been limited to single-analyte detection, which constrains our understanding of how multiple neurochemicals interact during disease progression [16,17,18].

Although some progress has been made toward multi-analyte detection, existing systems often involve fabrication methods that are complex, time-consuming, or inaccessible for routine use [19]. For instance, Rafi and Zestos demonstrated simultaneous detection of DA, 5-HT, and adenosine using a microelectrode array (MEA), but their MEAs required laser ablation [20] and intricate assembly. Similarly, Castagnola et al. developed a glassy carbon-based electrode for DA and 5-HT detection, yet their six-step fabrication protocol [21] poses barriers to widespread adoption. In contrast, our group recently introduced a simple and reproducible method to fabricate double- bore CFMs that allowed simultaneous detection of two analytes, laying the groundwork for more advanced multi-channel sensors [22].

Surface modification has long played a pivotal role in enhancing the sensitivity and selectivity of CFMs. A notable example comes from Hashemi et al., who successfully employed Nafion [23], a cation exchange polymer, to coat single-bore CFMs. This strategy enabled selective 5-HT detection in the presence of its major metabolite, 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA), which shares a nearly identical oxidation potential but exists in significantly higher concentrations. Nafion coatings also help reduce interference from anionic species like ascorbic acid (AA), thereby enhancing selectivity for DA. Despite these successes, multi-analyte detection platforms have largely failed to integrate selective surface modifications, an essential feature for resolving overlapping electrochemical signals in complex biological environments.

In this study, we introduce a next-generation electrochemical sensor: a laser-trimmed, four-bore CFM platform capable of simultaneously detecting four distinct analytes with high temporal resolution using FSCV. Our fabrication approach is both cost-effective and straightforward compared to previously reported methods [24,25], as the laser used in this study is a simple wood-engraving laser, ensuring reproducibility and accessibility without compromising performance. Each bore can be independently surface-modified to target specific analytes, enabling selective detection of 5-HT in the presence of its metabolite 5-HIAA, DA in the presence of AA, and the simultaneous detection of toxic metal ions such as Cu2+, Cd2+, and As3+ alongside neurotransmitters. We validated the structural and chemical modifications of the electrodes using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX), confirming the success of our surface treatments. The sensor’s performance was characterized through a series of in vitro experiments using two distinct analyte mixtures: one composed of DA and three toxic metal ions (Cu2+, Cd2+, and As3+), and the other composed of neurotransmitters (DA, AA, 5-HT, and 5-HIAA). To benchmark our platform, we performed controlled experiments using conventional single-bore CFMs for comparison. Compared to single-bore electrodes, our four-bore CFMs demonstrated enhanced sensitivity, improved signal resolution, and superior selectivity. These findings position our platform as a strong candidate for the next phase of development, an implantable in vivo sensor for real-time neurochemical monitoring in mouse models. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a laser-trimmed, selectively surface-modified four-bore CFM capable of detecting four analytes simultaneously using FSCV at a temporal resolution of 100 milliseconds. This work represents a significant advancement in real-time, multi-analyte neurochemical sensing and lays the groundwork for future applications in studying the molecular mechanisms underlying neurodegenerative diseases.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) unless specified otherwise and used without further purification. L-ascorbic acid was obtained from Fisher Chemical (Pittsburgh, PA, USA) for preparing AA solutions. Dopamine hydrochloride was purchased from Alfa Aesar (Tewksbury, MA, USA), and serotonin hydrochloride from Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan), 5-hydroxyindole-3-acetic acid (99%) was sourced from Thermo Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). Liquion™ Solution LQ-1105 (Ion Power, Inc., New Castle, DE, USA) was used for Nafion electrodeposition. Cupric sulfate was purchased from Fisher Scientific (Hampton, NH, USA) as the Cu2+ source. Sodium meta-arsenite and cadmium chloride were obtained from Alfa Aesar (Ward Hill, MA, USA) as the As3+ and Cd2+ sources, respectively. 1% AuCl3 (Salt Lake Metals, Nephi, UT, USA) was used for gold nanoparticle electrodeposition. All analyte solutions were prepared in tris buffer consisting of 15 mM tris hydrochloride, 140 mM NaCl, 3.25 mM KCl, 1.2 mM CaCl2, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 1.2 mM MgCl2, and 2.0 mM Na2SO4, adjusted to pH 7.4 or 6.5 depending on the experiment.

2.2. Fabrication of Laser-Trimmed Four-Bore CFMs

Four-bore CFMs were fabricated by inserting four individual carbon fibers (diameter: 7 µm; Goodfellow, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) into a glass capillary containing four bores (individual bore diameter: 0.015″; outer diameter: 0.105″; Friedrich and Dimmock, Millville, NJ, USA). The fiber-filled capillaries were then pulled under gravity using a vertical puller (PE-100, Narishige Group, Setagaya-Ku, Tokyo, Japan), resulting in two glass-encapsulated, carbon-sealed microelectrodes. Following the pulling process, the protruding carbon fibers were trimmed to ~30–40 µm in length using a 450 nm optical laser (LASER TREE, Shenzhen, China) operating at 4 watts and with a focal length of 5–10 cm. The total trimming time for all four fibers was ~10–20 s. Electrical connections were established by filling each bore with a small amount of mercury, which provided contact with a connecting wire (see Figure 1A).

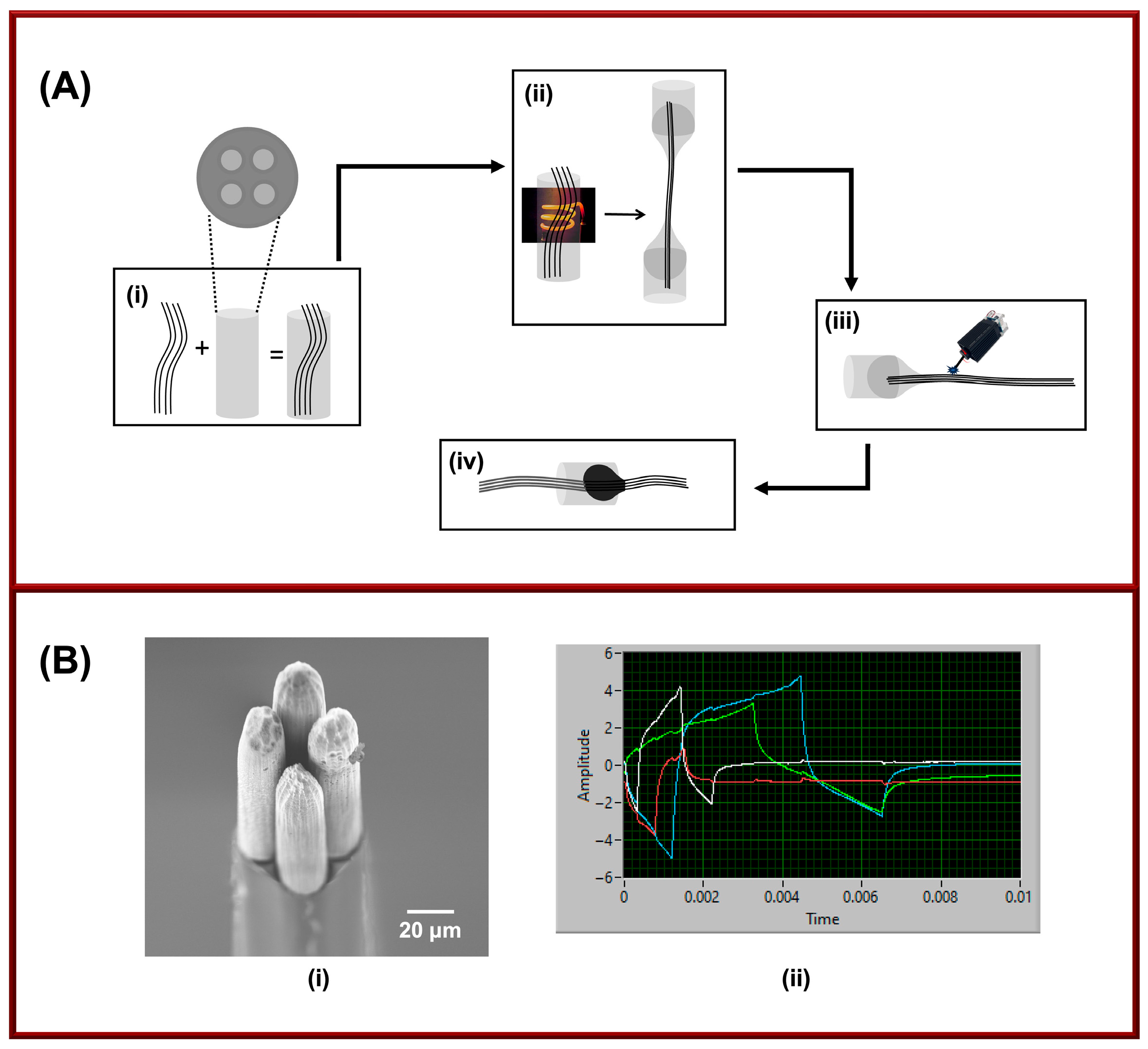

Figure 1.

(A) Fabrication of four-bore CFMs: (i) insertion of four carbon fibers into a four-channel glass capillary, (ii) pulling the capillary under heat and gravity, (iii) laser trimming each fiber to ~30–50 µm under an optical microscope, and (iv) filling bores with mercury to establish electrical contact. (B) Characterization: (i) SEM image showing trimmed fibers with intact carbon-glass seals, (ii) oscilloscope output of four applied waveforms, and waveform overlay, white: 5-HT (−0.1 V to +1.0 V at 1000 V/s), red: Cd2+ (−0.8 V to −1.4 V at 400 V/s with AuNPs), green: DA (−0.6 V to +1.2 V at 400 V/s), and blue: Cu2+ (−0.7 V to +1.2 V at 400 V/s).

2.3. Surface Modification with Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs)

Surface modification of the four-bore CFM with AuNPs was performed to enable selective detection of Cd2+, following the method reported by the Zestos group [26] with minor modifications. One of the carbon fibers was selectively electrodeposited with AuNPs by immersing the electrode in a solution containing 2.94 ppm of 1% AuCl3 and 0.1 M KCl. A potential range from +0.2 V to −1.0 V was applied at a scan rate of 50 mV/s for 20 cycles. The electrochemical setup consisted of a three-electrode system: an in-house fabricated Ag/AgCl reference electrode, a platinum wire counter electrode, and a CHI660E potentiostat (CH Instruments, Austin, TX, USA).

2.4. Surface Modification with Nafion

Nafion electrodeposition was carried out following the protocol established by Hashemi et al. [23]. Two diagonally positioned carbon fibers within the four-bore CFM were electrically connected for selective surface modification. The electrode was immersed in a 5% Nafion solution, and a constant potential of +1 V was applied for 15–20 s. After deposition, the electrode was air-dried for 15 s and then heat-cured at 70 °C for 10 min. A two-electrode system was employed, consisting of a custom-built Ag/AgCl reference electrode. Electrodeposition was performed using the Quad-UEI system (Electronics Design Facility, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA).

2.5. Electrochemical Measurements

All electrochemical measurements were carried out using a two-electrode system, with CFMs serving as the working electrodes and an in-house-built Ag/AgCl electrode as the reference. FSCV experiments, including data acquisition, and analysis were conducted using the Quad-UEI system (Electronics Design Facility, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA). Each electrochemical experiment was performed using multiple CFMs with several replicates per condition. Results are reported as the mean of all replicate measurements, with error bars representing the standard error of the mean.

2.6. Imaging and Elemental Analysis

Surface analysis of the four-bore CFMs was performed via SEM and EDX spectroscopy. Images and elemental data were acquired with a field emission SEM (JSM-IT710HR, JEOL USA, Inc., Peabody, MA, USA) at the High-Resolution Microscopy and Advanced Imaging Center, Florida Institute of Technology.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Laser-Trimmed Four-Bores

In efforts to better understand the complex causes of neurodegeneration, it is critically important to develop analytical systems capable of capturing ultrafast neurochemical events with high selectivity and sensitivity. Moreover, these systems must be made accessible globally, particularly in economically challenged regions, where access to quality healthcare remains limited. For multi-analyte detection tools, especially those intended for in vivo applications, several design considerations are essential. The sensor material must be biocompatible and cause minimal tissue damage upon implantation, necessitating an ultra-small electrode size. However, as the electrode size decreases, the sensitivity must not be compromised, since detecting ultra-low concentrations of neurotransmitters and other analytes is essential. Temporal resolution must also remain high to capture rapid neurochemical fluctuations occurring in the brain or in the body fluids. Meeting all these criteria simultaneously is technically demanding, and this complexity is a major reason why such advanced sensing systems are not yet widely available in clinical settings.

Although promising FSCV based multi-analyte sensing systems have been reported [27,28], most are limited to detecting only two or three analytes and typically require intricate, time-consuming fabrication steps involving highly specialized laboratory environments. These factors make such systems less accessible in resource-limited settings. To address these challenges, we developed a four-bore CFM using a straightforward, cost-effective fabrication process (Figure 1A). Building on our previously published work with double-bore CFMs, we determined that a minimum inter bore spacing of ~485 µm is critical for maintaining proper separation between carbon fibers, especially during high scan rate cycling. Based on this, we selected, customized four-bore glass capillaries with inter-bore gaps of ~485 µm. Individual carbon fibers were inserted into each bore, and the filled glass capillary was pulled into two halves using a vertical puller, allowing gravity to assist the separation while melting the glass to form a seal. Although inserting four carbon fibers may appear to be a straightforward extension of the two-fiber process, this step is quite challenging, as the fibers naturally attract and tend to tangle with one another. Therefore, special care was required to ensure that all four fibers remained properly separated throughout the process.

Initially, we attempted to trim all four fibers manually using a scalpel under a microscope. While some success was achieved, the overall success rate was below 50 percent, and most attempts led to breakage of the glass seal. Manual trimming works well for single- and double-bore CFMs, where fibers can be cut against the glass to preserve the seal. However, in the four-bore configuration, the spatial arrangement of the fibers makes this method unreliable, as not all fibers can be simultaneously positioned against the glass for trimming. We also tried spark trimming, previously applied to single-bore CFMs [29], but it failed to yield fibers of the desired length and often melted the glass due to high voltage.

Ultimately, we found success using a simple optical laser system under the microscope. Although the laser setup lacked advanced controls, we optimized the working distance and orientation to trim all four fibers to a consistent length of ~30 to 40 µm, without damaging the glass seal. The entire trimming process takes only 10 to 20 s. While Amemiya’s group has demonstrated laser milling for CFMs using a highly focused ion beam system [30] with a gallium source, their method, though capable of producing smooth, uniform electrode surfaces, is expensive and labor-intensive, making it less suitable for laboratories with limited resources. In contrast, our approach is both economical and efficient.

SEM images confirmed that our laser-trimmed four-bore CFMs maintained intact carbon glass seals and consistent fiber lengths. Interestingly, the laser created micro-holes on the carbon fibers (Figure 1(Bi)), thereby increasing the surface area, an effect that has previously been achieved using chemical treatments such as potassium hydroxide etching [31]. This increase in surface area is expected to enhance analyte sensitivity, which is advantageous for real-time multi-analyte detection relevant to neurodegenerative disease research. Furthermore, when we applied four different waveforms to the four individual carbon fibers in tris buffer, the electrodes retained a stable gap and showed no signal interference, further confirming the mechanical and electrochemical stability of our design (Figure 1(Bii)).

3.2. Analysis of Metal Ion Mixtures

One of the central objectives of our research group is to investigate the fate and neurotoxicity of heavy metals in biological systems, particularly their role in the onset and progression of neurodegenerative disorders. Toxic metals such as As3+, Cd2+, and Cu2+ have been consistently associated with harmful health outcomes, including damage to vital organs and the central nervous system [32,33]. With the rising use of these metals in industrial applications, electronic manufacturing, and agricultural pesticides, their environmental concentrations have significantly increased. This, in turn, elevates the risk of human exposure through air, water, and food sources. Given their potential to accumulate in neural tissue and disrupt neurochemical homeostasis, it is essential to develop sensitive and selective analytical tools capable of detecting these ions in real-time and under physiologically relevant conditions for future in vivo investigations.

After verifying the structural stability and functional integrity of our newly developed four-bore CFMs, especially their ability to sustain separate potential windows while maintaining spatial separation between fibers, we proceeded to assess their electrochemical performance in detecting toxic metal ion mixtures. To date, FSCV waveform parameters have been optimized for four specific metal ions: Cu2+ [34], Pb2+ [35], Cd2+ [36], and As3+ [37]. Among these, Hashemi’s group previously demonstrated that Pb2+ detection in tris buffer, commonly used as an analog for artificial cerebrospinal fluid, was ineffective [35]. Their work required the formulation of a specialized buffer system to support Pb2+ measurements, which complicates standardization for broader use. Considering the objective of developing a method that is both reproducible and compatible with physiologically relevant buffers, we excluded Pb2+ from our analysis and focused instead on Cu2+, As3+, and Cd2+ as our model analytes. Additionally, DA was included as a fourth analyte to be detected with the remaining carbon fiber, enabling us to investigate possible interactions between DA and these toxic metal ions. Since the detection of As3+ requires mildly acidic conditions [37] for optimal electrochemical response, the pH of tris buffer was adjusted to 6.5 for all experiments in this study.

Achieving high analyte selectivity during simultaneous multi-analyte detection, especially in complex biological matrices, presents a significant challenge. Selectivity can be enhanced by applying distinct waveforms for each analyte or through electrode surface modification strategies that enhance sensitivity toward target molecules. In this study, the detection of Cd2+ necessitated modifying the electrode surface with AuNPs [36], a method shown to enhance Cd2+ sensitivity through catalytic effects. Following a procedure reported by the Zestos group [28], we selectively electrodeposited AuNPs onto one of the four carbon fibers, while leaving the remaining three electrodes unmodified.

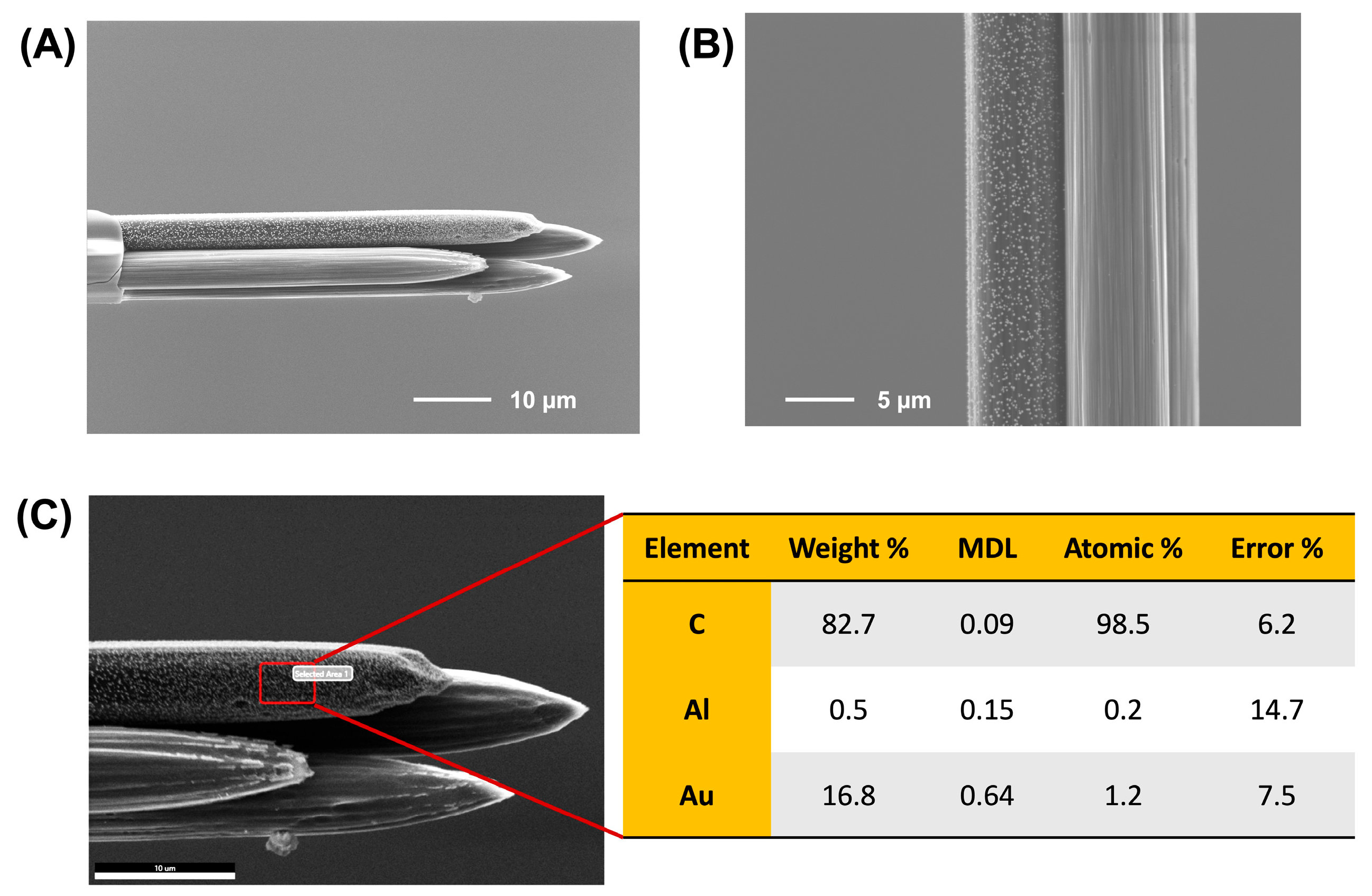

To confirm successful surface modification, we employed SEM, which clearly revealed a distinct layer of AuNPs deposited on the modified electrode. The other three electrodes retained their native striated morphology characteristic of bare CFMs (Figure 2A). EDX analysis was also performed to quantify the elemental composition of each electrode. As shown in Figure 2B and Figure S1, the AuNP-modified electrode displayed a significant gold signal, with a weight percentage of ~16.8%. In contrast, the remaining three electrodes showed no detectable gold, confirming the absence of AuNPs on those surfaces. These findings are significant as they not only demonstrate the successful fabrication of a four-bore CFM system but also validate our ability to achieve precise, selective surface modification of individual electrodes spaced only ~600 nm apart. This level of control is crucial for enabling targeted analyte detection in complex environments and represents a major step forward in developing advanced, real-time electrochemical sensors for neurotoxicology applications.

Figure 2.

SEM images of a laser-trimmed four-bore CFM following selective electrodeposition of AuNPs on one fiber, acquired using a 10 kV electron beam at (A) 2300× and (B) 6500× magnifications. AuNPs are clearly visible on the modified electrode, while characteristic striations are observed on the remaining unmodified carbon fibers. (C) EDX analysis of the AuNP-modified electrode showing elemental composition (C, Al, Au), including weight percentage, minimum detection limit (MDL), atomic percentage, and error values. The presence of 16.8% Au by weight confirms successful and selective surface modification.

After confirming the successful surface modification required for Cd2+ detection, we proceeded to evaluate the performance of our four-bore CFM in detecting complex mixtures of neurotransmitters and toxic metal ions. Specifically, we prepared solutions in tris buffer containing various concentration ratios of Cu2+, As3+, Cd2+, and DA and applied optimized, distinct FSCV waveforms to each of the four electrodes for simultaneous detection. In FSCV, the forward scan is typically used for both qualitative identification and quantitative analysis, as it often contains the most distinguishable redox signals for target analytes. This is primarily because during the forward scan the electrode surface is cleaner, allowing the analyte to undergo oxidation or reduction more effectively, whereas on the backward scan, the analyte interacts with an already contaminated surface. Therefore, in our experiments, we focused on the reduction peaks of Cu2+ and Cd2+ that appear during the forward scan, and the oxidation peaks of DA and As3+ that also manifest during the forward sweep. Due to the complexity of the mixture and the similarity in redox potentials of some of these species, we anticipated potential signal overlap on the resulting cyclic voltammograms (CVs).

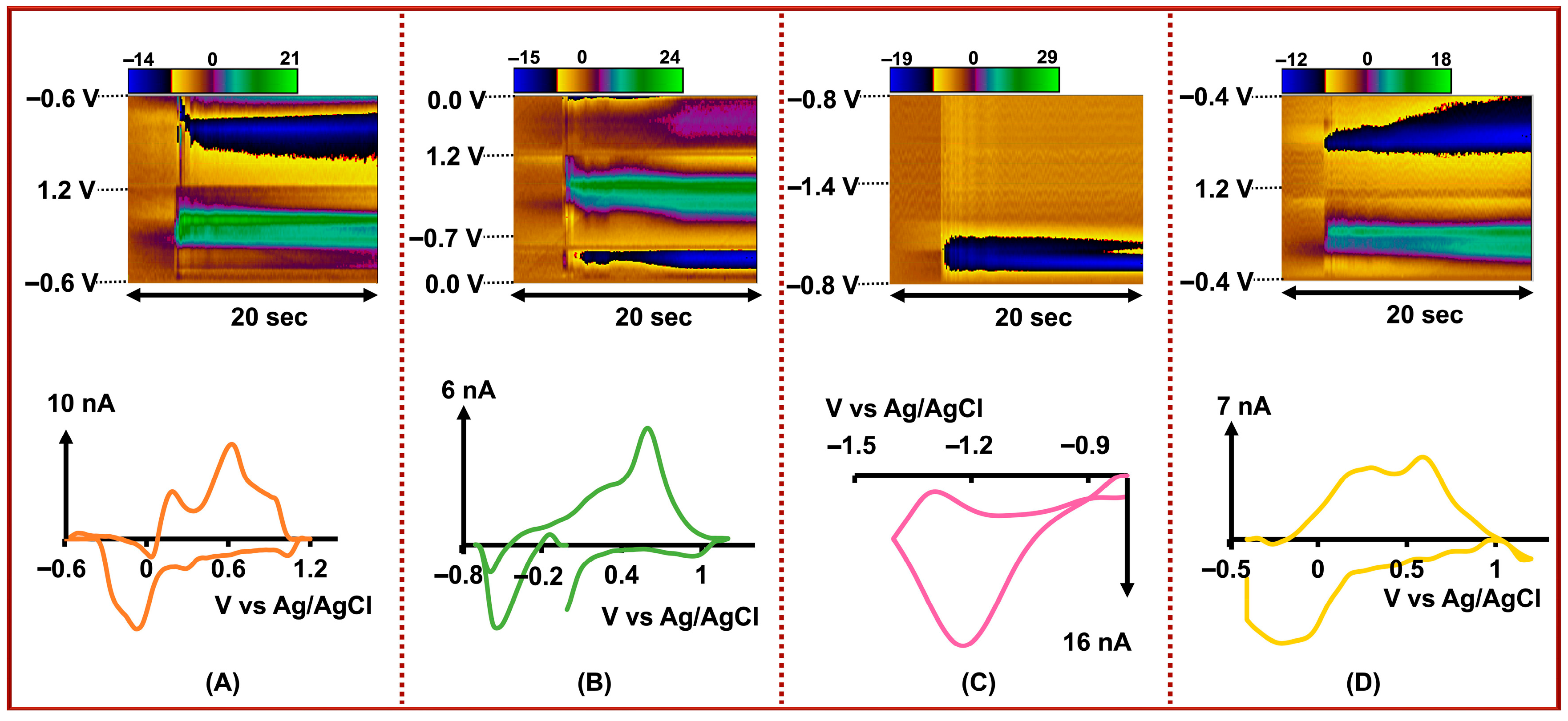

As shown in Figure 3, the CV for Cd2+ exhibited a sharp and distinct reduction peak around −1.2 V, attributed to the reduction of Cd2+ to Cd0, consistent with our previous observations using single CFMs [36]. This consistency demonstrates that our selective surface modification with AuNPs not only maintained but enhanced the electrode’s ability to detect Cd2+, likely due to improved electron transfer kinetics and increased electroactive surface area. Moreover, the waveform used for Cd2+ detection is notably different from those used for the other analytes, which helps to minimize crosstalk or interference between adjacent channels. Similarly, a reduction peak corresponding to the conversion of Cu2+ to Cu0 was observed on the forward scan around −0.5 V, although some overlapping oxidation signals were present on the reverse scan. These secondary features may be attributed to the oxidation of DA and As3+; however, since Cu2+ quantification relies solely on the reduction peak in the forward scan, these overlapping signals do not interfere with our analytical interpretation.

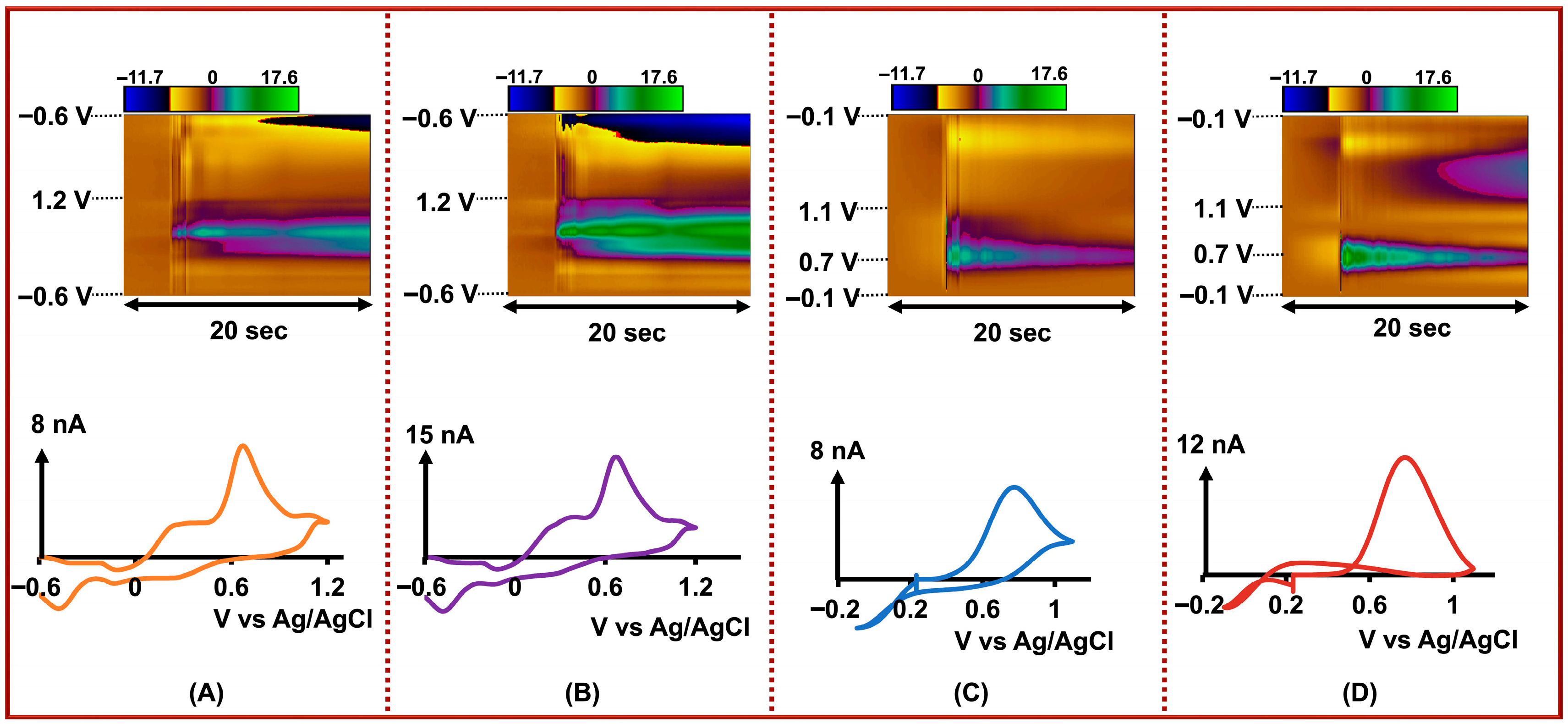

Figure 3.

Top row: Representative color plots showing the simultaneous detection of (A) DA, 0.5 µM, (B) Cu2+, 2.0 µM, (C) Cd2+, 0.01 µM, and (D) As3+, 1.0 µM. Bottom row: Corresponding CVs for each analyte extracted from the color plots. All measurements were obtained simultaneously using our four-bore CFM system with individually applied, optimized FSCV waveforms for each analyte.

In the case of DA, we consistently observed a primary oxidation peak near +0.6 V, corresponding to the oxidation of DA to dopamine-o-quinone, accompanied by a secondary peak around +0.25 V at lower concentrations. We attribute this pre-peak to the oxidation of As3+ to As5+, which shares some similarities in electrochemical behavior with DA under the applied conditions. A similar dual-peak pattern was observed when using the waveform specific to As3+, reinforcing the hypothesis that the overlapping peaks result from close waveform characteristics and similar oxidation potentials. Interestingly, the peak currents corresponding to both DA and As3+ increased proportionally with increasing analyte concentrations up to 1 μM for DA and 5 μM for As3+. However, beyond these concentrations, the oxidation peak for As3+ diminished, and the CVs were dominated by the DA signal alone, as shown in Figure S2. This disappearance of the As3+ peak at higher concentrations may be attributed to competitive adsorption at the carbon fiber surface. Since DA is known to strongly adsorb to carbon-based electrodes, it likely outcompetes As3+ for the limited active sites on the CFM, effectively suppressing the As3+ signal. This phenomenon highlights the importance of surface interactions in multi-analyte detection systems and the necessity for precise surface tuning when working in complex matrices. Furthermore, the inability to detect As3+ at higher concentrations is not a major limitation in our context, as the primary objective of this work is to develop a sensor capable of detecting low concentrations of these analytes under physiologically relevant in vivo conditions.

When the same analyte mixtures were tested using single-bore CFMs, with each waveform applied sequentially, CVs were observed only for DA, Cu2+, and Cd2+. Notably, no clear or distinguishable CV was obtained for As3+, and the signal obtained for Cd2+ appeared highly distorted (Figure S3); no reproducible and stable CVs were observed for Cd2+ at higher concentrations. These observations highlight several limitations of traditional single-bore CFMs in complex multi-analyte systems. In particular, the lack of resolution for As3+ suggests significant signal suppression, likely due to interference from coexisting analytes or overlapping electrochemical windows. Additionally, the distorted Cd2+ signal may result from adsorption competition, or poor electrode surface compatibility when analytes are detected sequentially using a single waveform.

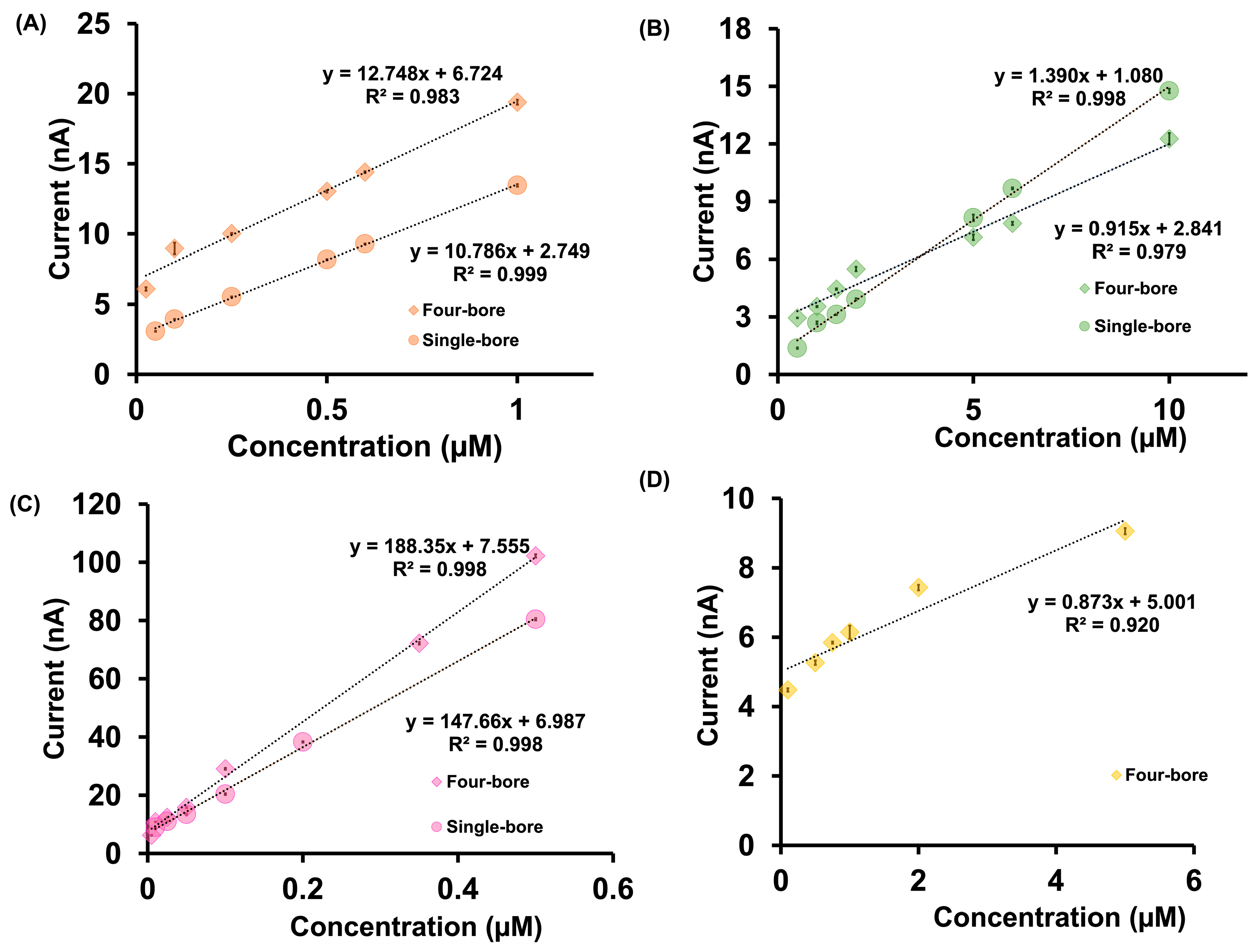

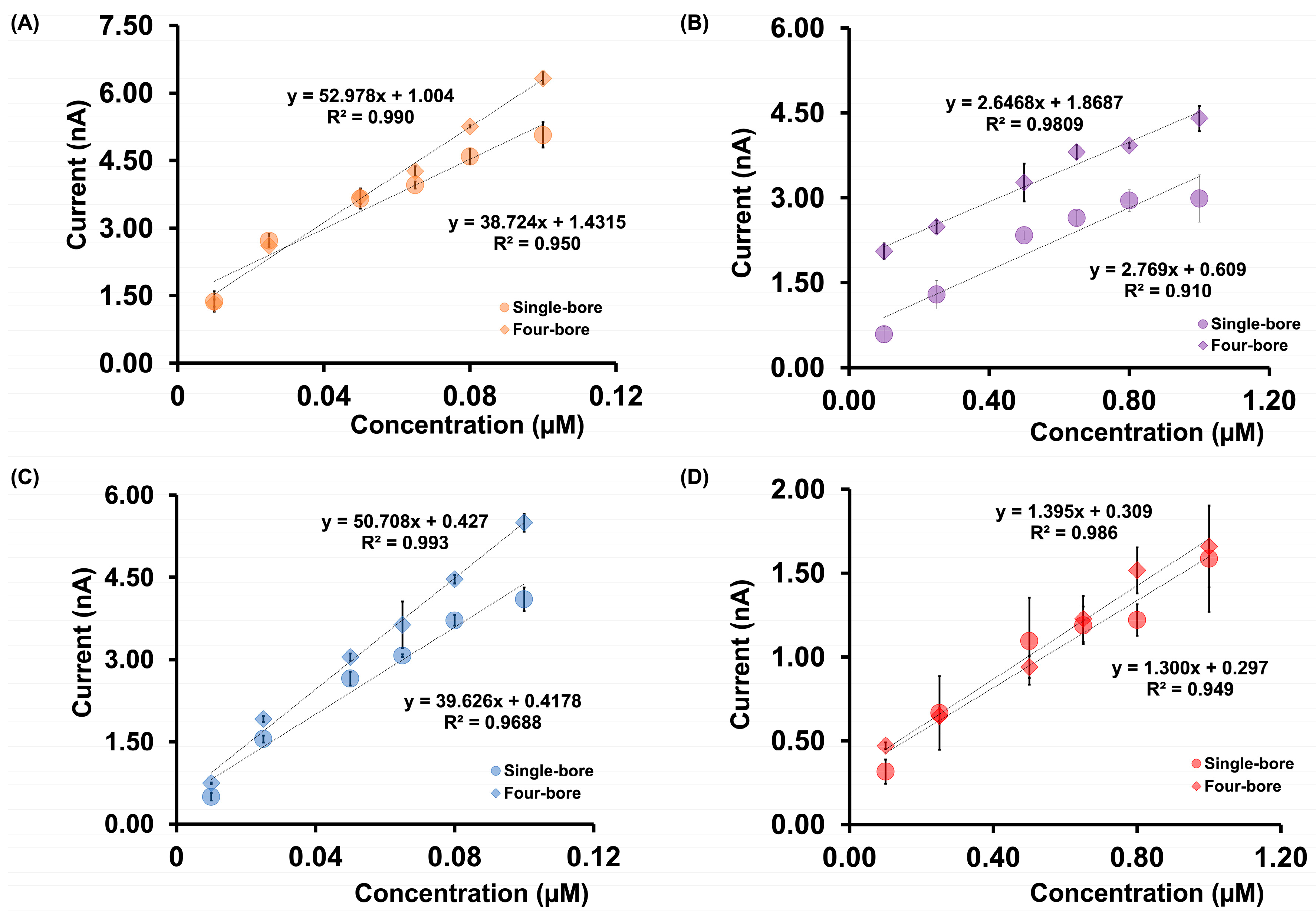

Figure 4 compares the linear calibration ranges obtained for DA, Cu2+, Cd2+, and As3+ using both four-bore and single-bore CFMs. Full calibration plots are provided in Figures S4 and S5. One of the most notable observations is the improved detection of As3+ using the four-bore configuration. When using single-bore CFMs, it was not possible to generate a reliable linear calibration curve for As3+ in mixed-analyte solutions due to the absence of distinguishable electrochemical signals attributable to As3+. This is likely due to signal suppression or peak overlap arising from coexisting analytes in the mixture. In contrast, the four-bore CFMs produced a well-defined and reproducible linear calibration curve for As3+ in the range of 0.1 µM to 5.0 µM, with a sensitivity of 0.873 nA µM−1. This enhanced performance is attributed to the spatial separation of the electrodes and the ability to apply individualized waveforms, which minimizes interference and competitive adsorption, especially for analytes with inherently weak redox activity or overlapping potential windows. In addition to As3+, notable sensitivity improvements were observed for other analytes as well. As shown in Table S1, the normalized sensitivity for DA increased by ~12%, from 10.786 to 12.748 nA µM−1, while Cd2+ demonstrated a 28% increase in sensitivity (from 147.660 to 188.350 nA µM−1). These improvements are likely the result of enhanced electrode surface utilization due to the laser-trimming process and the capability of the four-bore configuration to perform waveform multiplexing. Although the raw currents were lower due to shorter electrode lengths, normalizing current by length highlighted the true electrochemical advantage offered by the four-bore design. Interestingly, Cu2+ showed a 32% decrease in sensitivity (from 1.390 to 0.915 nA µM−1). This reduction may be explained by Cu2+’s propensity to form complexes with DA in solution, leading to a reduced concentration of free Cu2+ available for redox reactions at the electrode surface.

Figure 4.

Comparison of calibration curves for mixtures of (A) DA, (B) Cu2+, (C) Cd2+, and (D) As3+ in tris buffer using four-bore CFMs (diamonds) and single-bore CFMs (circles). Due to the absence of a clear response from As3+ with single-bore CFMs, only the calibration curve obtained with the four-bore configuration is shown.

The LOD values further validate the analytical strength of the four-bore CFM platform. While Cu2+ showed no significant improvement in LOD, both DA and Cd2+ exhibited twofold reductions in their detection limits, from 0.05 µM to 0.025 µM for DA and from 0.01 µM to 0.005 µM for Cd2+. Notably, the four-bore CFMs uniquely enabled the quantification of As3+ in complex mixtures with an LOD of 0.1 µM, an achievement that was not feasible with single-bore CFMs under identical experimental conditions. Together, these findings demonstrate that the four-bore CFM architecture provides superior analytical performance compared to traditional single-bore CFMs. The ability to simultaneously and selectively detect multiple analytes, even those prone to signal overlap or suppression, marks a significant advancement in electrochemical sensing, especially in complex biological and environmental matrices.

3.3. Analysis of Neurotransmitter Mixtures

Next, we evaluated the performance of our four-bore CFM system for simultaneous detection of DA, AA, 5-HT, and 5-HIAA in tris buffer (pH 7.4). DA and 5-HT play critical roles as neurotransmitters, while AA and 5-HIAA are commonly encountered interferents in electrochemical detection due to their similar oxidation potentials [38,39]. In particular, the oxidation peak of AA closely overlaps with that of DA (~+0.6–0.7 V), and 5-HIAA exhibits an oxidation potential very similar to that of 5-HT (~+0.8 V) [23,40]. Compounding this challenge, AA and 5-HIAA are typically present in significantly higher concentrations than DA and 5-HT in biological systems, which can easily mask the signal of the neurotransmitters of interest. To address this, previous studies, notably Hashemi et al., have demonstrated that modifying CFMs with Nafion [23], a sulfonated tetrafluoroethylene-based fluoropolymer, can greatly enhance selectivity. Nafion acts as a cation-exchange membrane: since 5-HIAA and AA are negatively charged under physiological pH, the Nafion layer effectively repels them while allowing positively charged neurotransmitters like 5-HT and DA to reach the electrode surface. This selectivity dramatically reduces signal interference, enabling clearer and more reliable detection of the target analytes. Building upon this approach, we aimed to investigate whether Nafion could be selectively electrodeposited onto two of the four electrodes within our four-bore CFM to enable electrochemical discrimination of DA from AA and 5-HT from 5-HIAA.

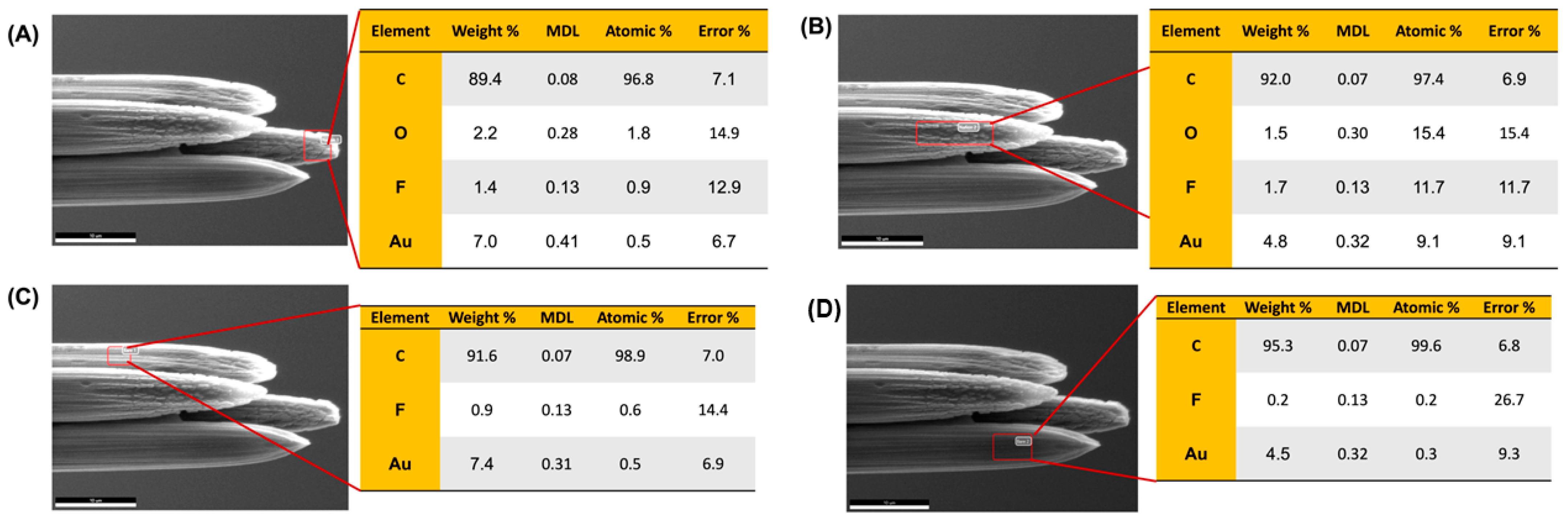

Following a previously reported protocol by the Hashemi group [23], Nafion was electrodeposited on two diagonally positioned carbon fibers within the four-bore assembly. We initially anticipated that Nafion would be deposited exclusively on these two targeted electrodes. However, subsequent surface characterization revealed partial cross-contamination. SEM images (Figure 5) showed that three of the four carbon fibers exhibited a thin Nafion film, while the fourth electrode displayed the typical bare striations characteristic of unmodified CFMs. This was further confirmed by EDX spectroscopy. The EDX analysis identified high fluorine (F) and oxygen (O) signals, hallmarks of Nafion on the two electrodes that were intentionally modified, as expected. However, a relatively smaller F signal was also detected on one of the adjacent unmodified electrodes, suggesting limited diffusion or splash-over of Nafion during the electrodeposition process. Importantly, unlike in our previous AuNP surface modification study, the current set of electrodes was gold-sputtered prior to SEM imaging to enhance surface resolution. Consequently, elemental Au was also detected in all four electrodes, as expected, and was not associated with surface functionalization in this case. Although the Nafion coating was not as spatially selective as our prior modification with AuNPs, the differences in surface coverage were still sufficient to proceed with electrochemical characterization. The varying Nafion distribution, as evidenced by the differing F and O signals across electrodes, suggested a gradient in surface properties that could still allow us to explore the sensor’s capability to resolve DA from AA and 5-HT from 5-HIAA in a simultaneous detection format. Therefore, we advanced to functional testing to assess the electrochemical performance of the partially modified four-bore CFM in a complex multi-analyte system.

Figure 5.

SEM images of a laser-trimmed four-bore CFM following selective electrodeposition of Nafion onto two carbon fibers. Panels (A,B) show EDX analysis of the two intended Nafion-coated electrodes, while (C,D) correspond to the unmodified, bare electrodes. Although Nafion was expected to be confined to only two fibers, SEM imaging reveals coating on three electrodes. Elemental analysis confirms the presence of F and O primarily on the intentionally modified electrodes. Au signals observed in all panels originate from gold sputtering performed prior to imaging for improved resolution.

Here, we conducted FSCV experiments using mixtures of DA, AA, 5-HT, and 5-HIAA prepared in the tris buffer (pH 7.4). To assess the selectivity of our four-bore CFMs, we strategically applied the DA waveform to two electrodes, one modified with Nafion and one left unmodified. Based on the charge-selective nature of Nafion, which repels negatively charged interferents, we expected only DA to be detected on the Nafion-coated electrode, while both DA and AA would be detected on the bare carbon fiber. Similarly, the 5-HT waveform was applied to the other two electrodes, with the expectation that 5-HT would be selectively detected on the Nafion-modified electrode and both 5-HT and 5-HIAA would be detected on the uncoated electrode.

As shown in Figure 6, CVs obtained from the four-bore CFM confirmed our predictions. The DA CV recorded from the Nafion-coated electrode closely matched the expected shape and oxidation peak, while the CV from the bare electrode showed the combined oxidation responses of DA and AA, which are known to have closely overlapping potentials. Similarly, the 5-HT waveform produced clean, well-resolved CVs from the Nafion-coated electrode, and the corresponding electrode without Nafion coating exhibited overlapping signals from both 5-HT and its common metabolite, 5-HIAA. These results clearly demonstrate the benefit of Nafion modification in enhancing the selectivity for positively charged neurotransmitters in the presence of common negatively charged interferents. For comparison, we performed the same experiment using single-bore CFMs, one modified with Nafion and one bare. As illustrated in Figure S6, while the CV for DA obtained using the Nafion-modified single-bore electrode was consistent with expectations, the remaining three CVs were distorted with extra peaks. These distorted responses likely result from signal interference and the lack of spatial separation, which limit the performance of single-channel systems.

Figure 6.

Simultaneous detection of DA, AA, 5-HT, and 5-HIAA using a four-bore CFM. Top row: Representative color plots showing electrochemical responses of (A) DA (0.1 µM) detected on a Nafion-coated electrode, (B) DA + AA (AA, 1.0 µM) on a bare electrode, (C) 5-HT (0.1 µM) on a Nafion-coated electrode, and (D) 5-HT + 5-HIAA (5-HIAA, 1.0 µM) on a bare electrode. Bottom row: Corresponding CVs for (A) DA, (B) DA + AA, (C) 5-HT, and (D) 5-HT + 5-HIAA, obtained by simultaneously applying the DA and 5-HT waveforms across the four electrodes for multi-analyte detection.

Figure 7 depicts the calibration data, specifically, the linear ranges obtained using our four-bore CFMs with those collected from the single-bore CFMs. Full calibration plots for both electrode types are provided in Figures S8 and S9. Although no significant differences were observed in the LOD or the linear dynamic ranges, a notable enhancement in sensitivity was seen for DA and serotonin 5-HT when using the four-bore configuration. Specifically, the sensitivity for DA increased by ~37%, from 38.724 to 52.978 nA µM−1, and for 5-HT by about 28%, from 39.626 to 50.708 nA µM−1. This improvement in sensitivity can likely be attributed to Nafion surface modification. Nafion, a cation-exchange polymer, repels negatively charged species such as AA and 5-HIAA, thereby enhancing the availability of electroactive surface sites for positively charged analytes like DA and 5-HT. Interestingly, the sensitivities for AA and 5-HIAA remained largely unchanged between the single-bore and four-bore systems. It is also important to note that the spatial selectivity of Nafion deposition in our four-bore CFM was not as precise as initially intended. SEM and EDX analysis revealed trace Nafion presence on fibers that were not targeted for modification. This unintended polymer deposition may have partially inhibited the adsorption of negatively charged analytes on the supposedly unmodified fibers, potentially diminishing their current response. Despite these limitations, the observed improvements in DA and 5-HT sensitivity highlight the advantages of the four-bore CFM architecture. Its ability to incorporate targeted surface modifications and apply distinct waveforms enables enhanced multi-analyte detection in complex matrices, where signal separation and electrode specificity are essential.

Figure 7.

Comparison of calibration curves for mixtures of (A) DA, (B) AA, (C) 5-HT, and (D) 5-HIAA in tris buffer using four-bore CFMs (diamonds) and single-bore CFMs (circles). The current response for AA was obtained by subtracting the DA-only signal (measured on a Nafion-coated fiber) from the combined DA + AA signal (measured on a bare carbon fiber). Similarly, the 5-HIAA response was derived by subtracting the 5-HT-only signal (measured on a Nafion-coated fiber) from the combined 5-HT + 5-HIAA signal (measured on a bare fiber).

4. Conclusions

Understanding real-time dynamic changes in neurotransmission, particularly the interplay between neurotransmitters and external agents such as toxic metal ions, is essential for uncovering the mechanisms underlying neurodegenerative diseases and for guiding the development of more effective therapeutics. To meet this need, it is critical to design analytical tools that are not only ultrafast and sensitive but also robust, cost-effective, and scalable for use across global healthcare systems.

In this study, we report the development of a novel, biocompatible, ultrafast electrochemical sensing platform: a laser-trimmed, four-bore CFM that enables the simultaneous detection of four distinct analytes using FSCV. Each carbon fiber, separated by nanometer-scale distances within the same glass capillary, was independently addressed with distinct FSCV waveforms, allowing for high spatial and electrochemical resolution without electrical crosstalk, a key advancement not previously reported in the literature to our knowledge. We characterized our system using the tris buffer, which closely mimics artificial cerebrospinal fluid, ensuring the potential for future translation to in vivo applications. Two types of chemically distinct multi-analyte mixtures were examined. For the detection of DA, Cu2+, Cd2+, and As3+, we selectively electrodeposited AuNPs onto one fiber to enhance sensitivity and selectivity. For a second application, we functionalized two electrodes with Nafion, a cation-exchange polymer, to separate electroactive neurotransmitters (DA and 5-HT) from common interferences (AA and 5-HIAA). SEM and EDX confirmed successful surface modifications and enabled topographical and elemental validation. Electrochemical performance was benchmarked against conventional single-bore CFMs. Our four-bore configuration demonstrated significant advantages, including enhanced sensitivity for multiple analytes, lower LODs, and improved linear dynamic ranges in some cases. Importantly, the ability to apply multiple waveforms simultaneously to surface-modified electrodes without electrical interference represents a significant technological leap, opening new avenues for complex sample analysis.

While the Nafion coating process was not as spatially selective as intended, highlighting an area for further optimization, our results nonetheless illustrate the strong potential of this multi-electrode platform. Beyond neurochemical applications, this sensor architecture could be adapted for rapid, multiplexed analysis in various fields, including environmental monitoring (e.g., detecting heavy metals in water systems), food safety (e.g., identifying contaminants or spoilage indicators), and biomedical diagnostics (e.g., monitoring metabolic or disease biomarkers in biological fluids). The next phase of this study will involve testing these electrodes in real biological samples, such as blood and urine, to assess potential interferences arising from complex biological matrices before moving into in vivo studies. Furthermore, looking ahead, integrating this four-bore CFM platform with machine learning or artificial intelligence could significantly enhance its utility by reducing or eliminating the need for extensive in vitro calibration and enabling real-time prediction of in vivo concentrations. Together, these innovations establish a strong foundation for the next generation of fast, reliable, eco-friendly, and customizable multi-analyte electrochemical sensors.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/chemosensors13120423/s1. Figure S1: Selective Electrodeposition of Gold Nanoparticles on a Single Fiber of a Four-Bore Carbon Fiber Microelectrode; Figure S2: Concentration-Dependent Peak Shifts in DA and As3+ Mixtures Indicate Competitive Adsorption; Figure S3: Limitations of Single-Bore CFMs for Detecting As3+ in Multi-Analyte Mixtures; Figure S4: Full Calibration of Four-Bore CFMs for DA, Cu2+, Cd2+ and As3+ in Multi-Analyte Mixtures; Figure S5: Full Calibration of Single-Bore CFMS for DA, Cu2+, and Cd2+ Detection in Multi-Analyte Mixtures; Figure S6: Detection of DA, AA, 5-HT, and 5-HIAA Using Nafion-Modified and Bare Single-Bore CFMs; Figure S7: Full Calibration of Four-Bore CFMs for DA, AA, 5-HT and 5-HIAA in Multi-Analyte Mixtures; Figure S8: Full Calibration of Single-Bore CFMs for DA, AA, 5-HT and 5-HIAA in Multi-Analyte Mixtures; Table S1: Comparison of Analytical Performance

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.P., N.U., A.D. and N.M.; Data curation, N.U. and A.D.; Formal analysis, P.P., N.U. and A.D.; Funding acquisition, P.P.; Investigation, P.P., N.M., N.U. and A.D.; Methodology, P.P., N.M., N.U., A.D. and G.K.; Project administration, P.P.; Software, N.U., A.D., N.M., V.G. and G.K.; Supervision, P.P.; Validation, N.U. and A.D.; Writing—original draft, N.U., A.D. and V.G.; Writing—review and editing, P.P., N.U. and A.D., All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Science Foundation (award number 2301577).

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this article have been included as part of the Supplementary Information.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Tatiana Karpova for her assistance and support. The authors also gratefully acknowledge the use of the Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscope acquired through the NSF-MRI program under award number CBET-2408574, titled “Acquisition of a Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscope for Engineering and Science Research at Florida Institute of Technology.” SEM imaging and related elemental analysis were conducted at the High-Resolution Microscopy and Advanced Imaging Center at Florida Institute of Technology.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Su, D.; Cui, Y.; He, C.; Yin, P.; Bai, R.; Zhu, J.; Lam, J.S.T.; Zhang, J.; Yan, R.; Zheng, X.; et al. Projections for Prevalence of Parkinson’s Disease and Its Driving Factors in 195 Countries and Territories to 2050: Modelling Study of Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. BMJ 2025, 388, e080952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gammon, K. Neurodegenerative Disease: Brain Windfall. Nature 2014, 515, 299–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, R.C.; Lockwood, A.H.; Sonawane, B.R. Neurodegenerative Diseases: An Overview of Environmental Risk Factors. Environ. Health Perspect. 2005, 113, 1250–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wareham, L.K.; Liddelow, S.A.; Temple, S.; Benowitz, L.I.; Di Polo, A.; Wellington, C.; Goldberg, J.L.; He, Z.; Duan, X.; Bu, G.; et al. Solving Neurodegeneration: Common Mechanisms and Strategies for New Treatments. Mol. Neurodegener. 2022, 17, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chin-Chan, M.; Navarro-Yepes, J.; Quintanilla-Vega, B. Environmental Pollutants as Risk Factors for Neuro-Degenerative Disorders: Alzheimer and Parkinson Diseases. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, K.R.; Martinez-Martin, P.; Schapira, A.H.V.; Stocchi, F.; Sethi, K.; Odin, P.; Brown, R.G.; Koller, W.; Barone, P.; MacPhee, G.; et al. International Multicenter Pilot Study of the First Comprehensive Self-Completed Nonmotor Symptoms Questionnaire for Parkinson’s Disease: The NMSQuest Study. Mov. Disord. 2006, 21, 916–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, S.; Chakraborty, A.J.; Tareq, A.M.; Emran, T.B.; Nainu, F.; Khusro, A.; Idris, A.M.; Khandaker, M.U.; Osman, H.; Alhumaydhi, F.A.; et al. Impact of Heavy Metals on the Environment and Human Health: Novel Therapeutic Insights to Counter the Toxicity. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2022, 34, 101865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podgorski, J.; Berg, M. Global Threat of Arsenic in Groundwater. Science 2020, 368, 845–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdala, A.P.; Paton, J.F.R.; Smith, J.C. Defining Inhibitory Neurone Function in Respiratory Circuits: Opportunities with Optogenetics? J. Physiol. 2015, 593, 3033–3046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venton, B.J.; Cao, Q. Fundamentals of Fast-Scan Cyclic Voltammetry for Dopamine Detection. Analyst 2020, 145, 1158–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathirathna, P.; Samaranayake, S.; Atcherley, C.W.; Parent, K.L.; Heien, M.L.; McElmurry, S.P.; Hashemi, P. Fast Voltammetry of Metals at Carbon-Fiber Microelectrodes: Copper Adsorption onto Activated Carbon Aids Rapid Electrochemical Analysis. Analyst 2014, 139, 4673–4680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Si, B.; Song, E. Recent Advances in the Detection of Neurotransmitters. Chemosensors 2018, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Shah, F.U.; Johansson Carne, L.; Geng, S.; Antzutkin, O.N.; Sain, M.; Oksman, K. Oriented Carbon Fiber Networks by Design from Renewables for Electrochemical Applications. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 12142–12154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Lü, L.; Shi, L. Surface Functionalization and Shape Tuning of Carbon Fiber Monofilament via Direct Microplasma Scanning for Ultramicroelectrode Application. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 531, 147414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcoswki, P.C.; Saraiva, D.P.M.; Ishiki, N.A.; Ticianelli, E.A.; Bertotti, M. A Dual-Barrel Carbon Fiber Microelectrode for Generator–Collector Experiments. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 36550–36558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Bian, S.; Sawan, M. Real-Time In Vivo Detection Techniques for Neurotransmitters: A Review. Analyst 2020, 145, 6193–6210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafi, H.; Zestos, A.G. Review—Recent Advances in FSCV Detection of Neurochemicals via Waveform and Carbon Microelectrode Modification. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2021, 168, 057520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huffman, M.L.; Venton, B.J. Carbon-Fiber Microelectrodes for In Vivo Applications. Analyst 2009, 134, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.R.; Popov, P.; Caldwell, C.M.; Welle, E.J.; Egert, D.; Pettibone, J.R.; Roossien, D.H.; Becker, J.B.; Berke, J.D.; Chestek, C.A.; et al. High Density Carbon Fiber Arrays for Chronic Electrophysiology, Fast Scan Cyclic Voltammetry, and Correlative Anatomy. J. Neural Eng. 2020, 17, 056029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafi, H.; Zestos, A.G. Multiplexing Neurochemical Detection with Carbon Fiber Multielectrode Arrays Using Fast-Scan Cyclic Voltammetry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2021, 413, 6715–6726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castagnola, E.; Cao, Q.; Robbins, E.; Wu, B.; Pwint, M.Y.; Siwakoti, U.; Cui, X.T. Glassy Carbon Fiber-Like Multielectrode Arrays for Neurochemical Sensing and Electrophysiology Recording. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2025, 10, 2400863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manring, N.; Strini, M.; Smeltz, J.L.; Pathirathna, P. Simultaneous Detection of Neurotransmitters and Cu2+ Using Double-Bore Carbon Fiber Microelectrodes via Fast-Scan Cyclic Voltammetry. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 33844–33851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashemi, P.; Dankoski, E.C.; Petrovic, J.; Keithley, R.B.; Wightman, R.M. Voltammetric Detection of 5-Hydroxytryptamine Release in the Rat Brain. Anal. Chem. 2009, 81, 9462–9471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Trikantzopoulos, E.; Nguyen, M.D.; Jacobs, C.B.; Wang, Y.; Mahjouri-Samani, M.; Ivanov, I.N.; Venton, B.J. Laser Treated Carbon Nanotube Yarn Microelectrodes for Rapid and Sensitive Detection of Dopamine In Vivo. ACS Sens. 2016, 1, 508–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, T.; Chen, L.; Shih, A. Laser Sharpening of Carbon Fiber Microelectrode Arrays for Brain Recording. J. Micro Nano-Manuf. 2020, 8, 041013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanaraj, S.; Wonnenberg, P.; Cohen, B.; Zhao, H.; Hartings, M.R.; Zou, S.; Fox, D.M.; Zestos, A.G. Gold Nanoparticle Modified Carbon Fiber Microelectrodes for Enhanced Neurochemical Detection. J. Vis. Exp. 2019, e59552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Robbins, E.M.; Wu, B.; Cui, X.T. Recent Advances in In Vivo Neurochemical Monitoring. Micromachines 2021, 12, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zestos, A.G. Carbon Nanoelectrodes for the Electrochemical Detection of Neurotransmitters. Int. J. Electrochem. 2018, 2018, 3679627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong-James, M.; Millar, J. Carbon Fibre Microelectrodes. J. Neurosci. Methods 1979, 1, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathirathna, P.; Balla, R.J.; Amemiya, S. Nanogap-Based Electrochemical Measurements at Double-Carbon-Fiber Ultramicroelectrodes. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90, 11746–11750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Lucktong, J.; Shao, Z.; Chang, Y.; Venton, B.J. Electrochemical Treatment in KOH Renews and Activates Carbon Fiber Microelectrode Surfaces. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2021, 413, 6737–6746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqubal, A.; Ahmed, M.; Ahmad, S.; Ranjan Sahoo, C.; Kashif Iqubal, M.; Ehtaishamul Haque, S. Environmental Neurotoxic Pollutants: Review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 27, 41175–41198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giacoppo, S.; Galuppo, M.; Calabrò, R.S.; D’Aleo, G.; Marra, A.; Sessa, E.; Bua, D.G.; Potortì, A.G.; Dugo, G.; Bramanti, P.; et al. Heavy Metals and Neurodegenerative Diseases: An Observational Study. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2014, 161, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manring, N.; Ahmed, M.M.N.; Smeltz, J.L.; Pathirathna, P. Electrodeposition of Dopamine onto Carbon Fiber Microelectrodes to Enhance the Detection of Cu2+ via Fast-Scan Cyclic Voltammetry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2023, 415, 4289–4296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Pathirathna, P.; Siriwardhane, T.; McElmurry, S.P.; Hashemi, P. Real-Time Subsecond Voltammetric Analysis of Pb in Aqueous Environmental Samples. Anal. Chem. 2013, 85, 7535–7541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manring, N.; Strini, M.; Koifman, G.; Smeltz, J.L.; Pathirathna, P. Gold Nanoparticle-Modified Carbon-Fiber Microelectrodes for the Electrochemical Detection of Cd2+ via Fast-Scan Cyclic Voltammetry. Micromachines 2024, 15, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manring, N.; Strini, M.; Koifman, G.; Xavier, J.; Smeltz, J.L.; Pathirathna, P. Ultrafast Detection of Arsenic Using Carbon-Fiber Microelectrodes and Fast-Scan Cyclic Voltammetry. Micromachines 2024, 15, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, B.P.; Dietz, S.M.; Wightman, R.M. Fast-Scan Cyclic Voltammetry of 5-Hydroxytryptamine at Conventional Scan Rates: Formation of an Insulating Film. Anal. Chem. 1995, 67, 1115–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, A.; Atcherley, C.W.; Pathirathna, P.; Samaranayake, S.; Qiang, B.; Peña, E.; Morgan, S.L.; Heien, M.L.; Hashemi, P. In Vivo Ambient Serotonin Measurements at Carbon-Fiber Microelectrodes. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 9703–9711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, W.; Liu, F.; Hendrix, A.; McCray, B.; Asrat, T.; Connaughton, V.; Zestos, A.G. Timed Electrodeposition of PEDOT:Nafion onto Carbon Fiber Microelectrodes Enhances Dopamine Detection in Zebrafish Retina. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2020, 167, 115501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).