Abstract

Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are emerging contaminants of global concern, requiring sensitive and highly selective detection methods. Stringent demands imposed by the Environmental Protection Agency, with maximum contaminant levels set at 4.0 parts per trillion for PFAS individually in drinking water, are the primary driving force behind the development of novel sensors for PFAS. Pushing towards these ultra-low concentrations, however, reaches the limit of what can be reliably detected by field sensors, with PFAS optical and electrochemical inactivity, making it nearly impossible. Molecularly imprinted polymers and immunoassays offer the best chance of developing such sensors as they interact specifically with the active site, changing the optical or electrochemical response (fluorescence, impedance, voltage). Nanoparticulate metal oxides, carbon materials, including carbon dots, polymer coating, and MXenes have been put forward; however, several of these approaches have failed to achieve either the desired limit of detection, sensitivity, or selectivity. Here, we provide an overview of recent progress in nanomaterial-based PFAS sensors, with particular emphasis on strategies to enhance sensitivity, selectivity, and reliability in complex matrices. Finally, we outline key challenges and future perspectives toward robust, field-deployable PFAS sensing technologies.

1. Introduction

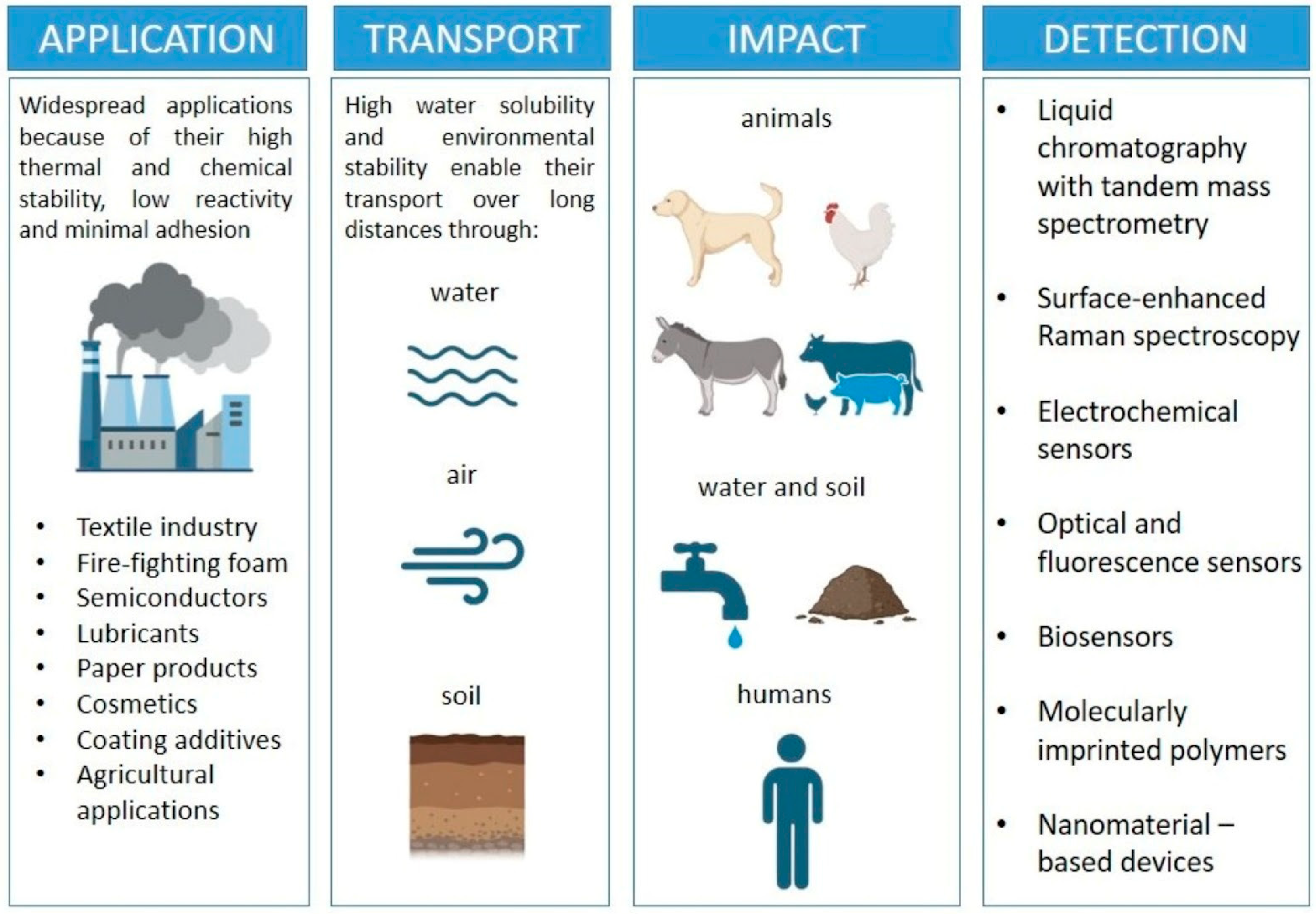

Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) comprise a class of synthetic compounds characterized by fully or partially fluorinated carbon chains. These molecules may possess terminal functional groups, such as carboxylic or sulfonic acids, which confer both hydrophobic and hydrophilic characteristics [1]. Their physicochemical behavior is largely determined by the chain length and the type of functional group, as well as by the unique properties of the fluorine atom and the strength of the carbon-fluorine bond [2]. PFASs exhibit high thermal and chemical stability, low reactivity, and minimal adhesion, traits that have driven their widespread application across numerous industrial sectors and in various consumer products [3]. Perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), the subgroup of PFASs known as perfluoroalkyl acids (PFAAs) (specifically perfluorosulfonic acids and perfluorocarboxylic acids, respectively) are the most widely studied of the PFAS chemicals. Yet, there are nearly five thousand PFAS identified by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and registered in the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) CompTox database [4].

PFASs are highly persistent; even when partial degradation occurs, they ultimately transform into mainly stable end products, collectively known as perfluoroalkyl and perfluoroalkyl (poly) ether acids. Certain PFASs can ionize in aqueous solution depending on pH. Based on their functional groups, PFASs are classified as: anionic (carboxylic or sulfonic groups), cationic (amines), zwitterionic (anionic- and cationic-forming groups), or nonionic (non-ionizable groups). Anionic per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) have been widely studied over the past two decades. However, recent research is increasingly focusing on cationic and zwitterionic PFASs, particularly in relation to treatment methods, due to their widespread presence in aquatic environments and their toxicity, which is comparable to that of anionic PFAS. The structural differences between these emerging PFAS and traditional anionic PFAS result in distinct removal behaviors [5,6].

Their high solubility in water medium and environmental stability enable their transport over long distances through water currents and aerosol deposition, resulting in widespread contamination of soil, water, wildlife, and humans [7]. The environmental persistence of PFAAs leads to long-term exposure that is difficult to reverse, even in groundwater, although electrochemical degradation may lead to their significant removal [8]. Their ionic nature and protein-binding [9] complicate bioaccumulation assessments, since elimination rates differ between species. For example, PFOA is rapidly cleared in fish but can persist in humans for years, emphasizing the need for chemical-specific evaluations of bioaccumulation and exposure [2]. Human exposure to PFASs poses potential risks to the immune, endocrine, and reproductive systems. Epidemiological studies have identified significant associations between PFAS exposure and adverse immune outcomes in children, while dyslipidemia appears as the most consistent metabolic effect. Evidence linking PFAS exposure to cancer is restricted to locations with extremely high occupational exposures, and data on neurodevelopmental impacts remain insufficient [10]. Exposure can occur through inhalation of dust or volatile compounds, dermal contact with cleaning agents or personal care products, and ingestion from food packaging; however, the primary route is the consumption of contaminated food or drinking water. Plants can absorb PFAS from contaminated soil, water, and biosolids, with short-chain PFAS more readily translocated to edible plant parts, representing a potential pathway for these pollutants to enter the food chain [11,12]. PFASs can also enter the animal food chain when farm animals ingest contaminated feed, water, or soil, leading to residues in products such as milk, eggs, and meat [12,13,14].

Growing concern about the environmental and toxicological impacts of PFAS has led the European Commission to propose a 2026 ban on all fluorinated substances containing at least one fully fluorinated methyl or methylene carbon, based on the OECD’s (2021) definition of PFAS. This restriction would affect over 9000 synthetic chemicals, including many essential pharmaceuticals, making implementation challenging. For this reason, IUPAC launched a project in 2024, which is currently ongoing, with the intention of standardizing PFAS terminology, classification, and nomenclature, thereby facilitating communication among researchers, industry, and regulatory agencies [15].

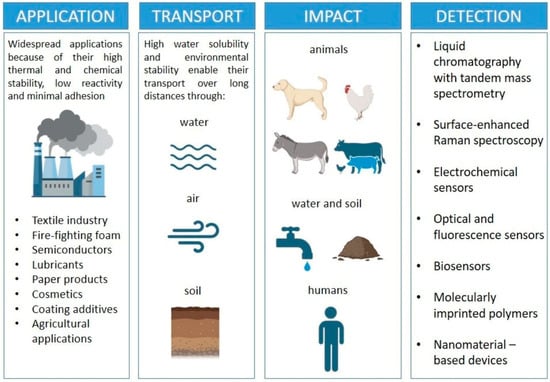

The detection of PFASs remains a major analytical challenge and the first step in propositions for their containment and removal (Figure 1). The current gold standard is liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) [16], which provides excellent sensitivity and selectivity, but relies on expensive instrumentation, trained personnel, and centralized laboratories. To overcome these limitations, a wide range of alternative sensing technologies is being developed. Electrochemical sensors, molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs), and nanomaterial-based devices (graphene, carbon nanotubes, gold nanoparticles, or metal–organic frameworks) have shown promising results, enabling higher sensitivity and improved selectivity [17]. Optical and biosensors, including fluorescence, aptamer-and antibody-based detection, as well as surface plasmon resonance, are also being explored to provide rapid and mobile detection [18]. Research is shifting toward portable and field-deployable devices capable of real-time monitoring, complementing laboratory-based analyses. Integration with digital technologies, such as smartphone apps, microfluidic chips, and wireless data transmission, is trending [19].

Figure 1.

PFAS widespread applications in industry, types of transport, their impact and contamination of nature, and a wide range of detection technologies.

Despite these advances, significant challenges remain. PFAS are typically present at ultra-trace levels (ppt or lower) in environmental waters, which demands extremely sensitive detection. Complex sample matrices such as natural organic matter, salts, and co-existing pollutants introduce interference and reduce accuracy. Furthermore, the structural diversity of PFAS makes it challenging to design universal sensing platforms. Many novel sensors that perform well under laboratory conditions suffer from poor reproducibility, limited robustness, and insufficient stability in real-world applications.

Another significant challenge in detecting PFASs is their tendency to adsorb to plastic surfaces, such as sampling bottles, tubes, containers, and other laboratory materials. This interaction with plastics can lead to substantial analyte loss, especially at ultra-low concentrations, resulting in falsely low readings and reduced accuracy. Zenobio et al. [20] argue that the choice of container is a crucial, yet often overlooked, source of error when measuring PFAS in water and other samples. They highlight that high-density polyethylene (HDPE) and polypropylene may not be the best materials for studies conducted in water, particularly those involving PFAS with longer carbon chains. Sensitive detection of PFAS in water requires efficient sample extraction. Solid phase extraction (SPE) is the standard approach, enabling the selective extraction and concentration of PFAS with high retention and compatibility with LC-MS/MS [21]. Additionally, micro-SPE offers faster, automatable processing with reduced sample and solvent use while maintaining high recovery [22]. Other methods, such as a solid phase extraction method, so-called QuEChERS (“quick, easy, cheap, effective, rugged, and safe”) and liquid–liquid extraction, are less commonly used in PFAS analysis due to their lower selectivity and matrix interferences.

There is also a growing effort to develop multiplexed sensors that can simultaneously target several PFAS classes. Ultimately, the development of cost-effective, reliable, and validated sensing technologies is critical for enabling widespread monitoring and effective environmental regulation of PFAS.

Nanomaterials may emerge as essential platforms in PFAS sensing, offering strategies to significantly enhance sensitivity, selectivity, and detection reliability [23]. By exploiting unique properties such as high surface area, tunable surface chemistry, and tailored electronic or optical responses, nanomaterial-based platforms may enable more robust and portable detection. Compared to conventional treatments, nanomaterials offer benefits including smaller size, higher specific surface area, and greater dispersibility in water. In PFAS sensing, nanomaterials are often integrated with polymers, biomolecules, or metal–organic frameworks to overcome limitations of single-component systems. Such hybrid architectures combine the textural properties and conductivity of nanostructures with the capabilities of functional coatings, enhanced sensitivity, selectivity, and reliability.

Several reviews have summarized PFAS detection methods and sensor technologies [23,24,25]. The majority of the available review literature classifies sensors by detection principle or device type. Here, the idea is to extend the insight into how the intrinsic properties of nanomaterials affect PFAS recognition and analytical performance. This review presents a materials chemistry-centered, critical approach, focusing on the role of material design, surface chemistry, and structure in sensing operations. Further, we address analytical merit, real-sample validation, and challenges that constrain practical PFAS detection with propositions on how to increase sensitivity, selectivity, and reliability. The present review offers an overview of the current progress in employing nanomaterials as platforms for PFAS detection, with a focus on recent advancements in the field over the past five years.

2. Nanomaterials in Sensing Technologies

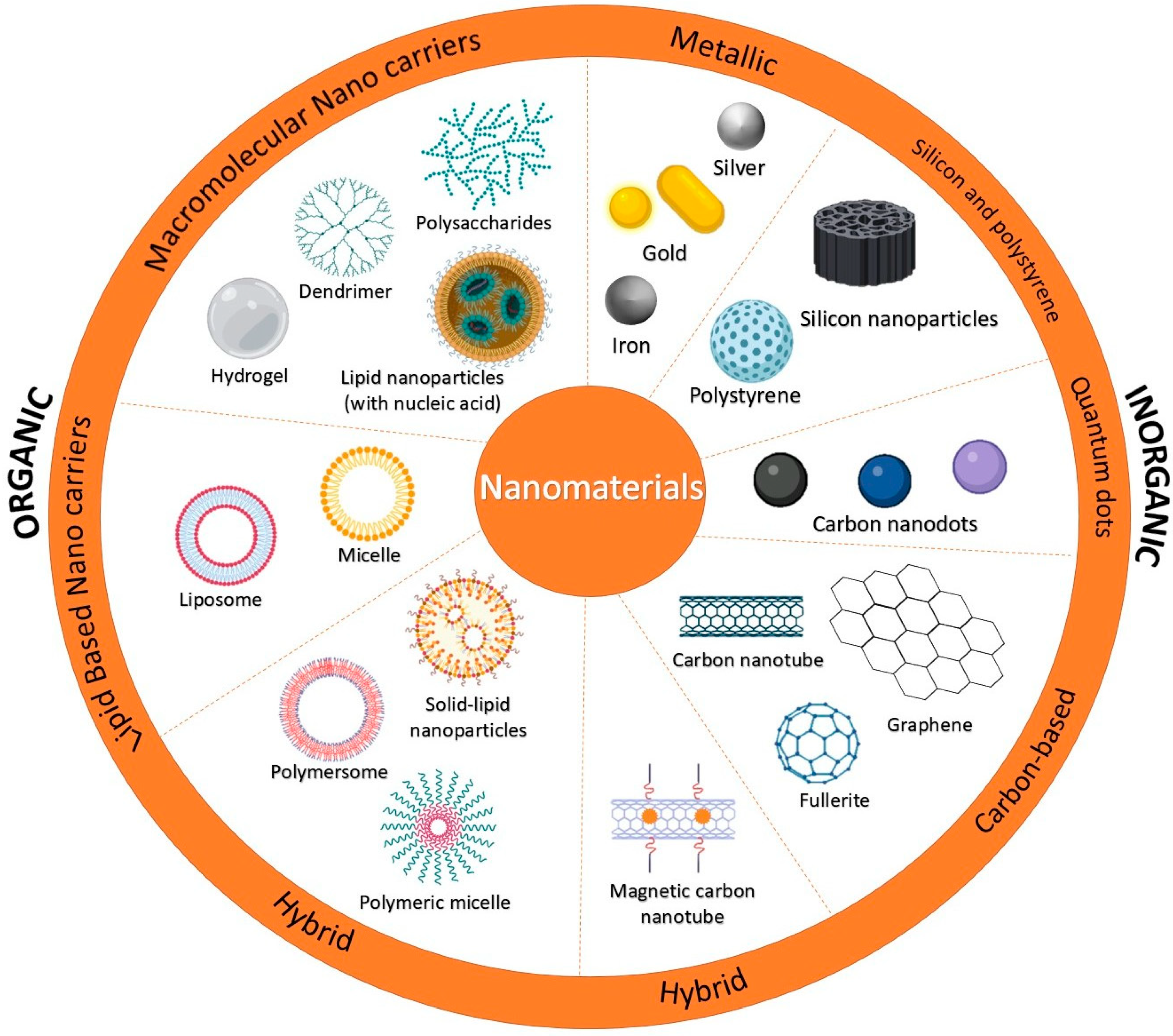

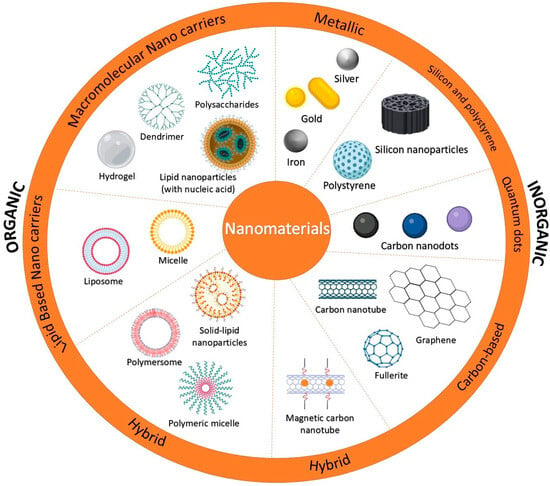

The rapid progress of nanotechnology has enabled the development of advanced nanosensors (Figure 2), significantly improving their design, fabrication, and applications. Due to extremely small particle size and high sensitivity, nanosensors have become essential tools across various fields, including healthcare [26], environmental monitoring, industrial processes [27,28], and security systems [29]. Innovative nanomaterials critically influence their performance, selectivity, and responsiveness. Research has focused on designing novel nanomaterials to sustain the recognition process and transduce signals with precision and sensitivity. A wide variety of nanomaterials, including carbon-based nanostructures (such as nanotubes and graphene), metal and metal oxide nanoparticles, quantum dots, and nanowires, have been explored as key components for the next generation of nanosensors [30].

Figure 2.

Nanomaterials used in sensors.

Nanoparticles have been utilized to detect and remediate various contaminants in different matrices, thanks to their miniaturization, portability, and rapid response. Nanomaterial-based sensors are being engineered for high efficiency, versatility, and the ability to detect multiple pollutants simultaneously. Beyond monitoring, nanomaterials can also aid in pollutant capture and degradation.

3. Nanomaterials Used for PFAS Detection

Many regulatory institutions, such as the U.S. EPA, continually monitor and maintain PFAS levels in environmental water tables [31]. The EPA has established enforceable maximum contaminant levels (MCLs) of 4 ppt for both PFOA and PFOS in drinking water, representing the strictest standards to date for PFAS regulation [32]. This effort requires the development of sensor technology to detect, monitor, and degrade these “forever” pollutants. Recent progress in nanotechnology has overcome the limitations of traditional approaches for detecting and removing PFAS from water. The increasing demand to remove even low levels of PFAS from drinking water has driven the development of various remediation strategies. However, the exceptionally strong C-F bond in PFAS makes complete degradation challenging, and conventional destruction methods, such as thermal treatment, have limited effectiveness. Therefore, novel nanosensor technology is needed to detect, monitor, and degrade pollutants, ensuring the safe, efficient, and cost-effective elimination of PFAS [33]. In novel routes, electrochemical degradation methods are especially addressed [34,35,36,37].

The classification of PFAS sensors is closely related to their working mechanisms, the materials employed, and the type of output signal. Major types include optical sensors, electrochemical sensors, and biosensors [38]. The design of optical nanosensors encompasses methodologies such as colorimetry, fluorescence, plasmonics, and surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS). Electrochemical nanosensors work by detecting the electric current generated during redox reactions at the electrode surface. The conductive electrode is usually modified with a selective chemical receptor that interacts specifically with the target analyte. There are several types of electrochemical sensors, including conductometric, impedimetric, potentiometric, and voltammetric sensors. For PFAS detection, however, voltammetric and potentiometric sensors are the most commonly used. Biosensors based on antibodies and aptamers are currently the most developed and reliable approaches for PFAS detection. Immunonanosensors use the specific binding between antibodies and PFAS to detect these molecules. Attaching antibodies to nanomaterials increases the sensor surface area and binding capacity. Aptamer-based PFAS nanosensors use single-stranded DNA or RNA molecules designed to bind specifically to PFAS [38]. The materials used in nanosensors often fall into multiple categories simultaneously.

Plasmonic nanomaterials, such as gold and silver nanoparticles, are widely used because their free electrons collectively oscillate in response to light, which provides distinctive optical properties. Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) are among the most stable nanomaterials, characterized by a large surface area, strong adsorption capacity, and high stability, which make them easily tunable for selective sensing. Their nanoscale dimensions allow modifications to be performed almost at the molecular level, enabling ultrasensitive detection. Additionally, a unique morphology, size-dependent optical behavior, and efficient fluorescence quenching, and the ability to enhance Raman scattering (SERS) [39]. Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) exhibit stronger plasmonic properties than gold due to their favorable dielectric function, giving intense, tunable surface plasmon resonance across the visible range. Their high abundance, strong scattering, and sensitivity to environmental changes make them superior for sensing, SERS, catalysis, and various optical and biomedical applications [40].

Magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (IONPs) are applied in optical sensors, where their magnetic properties facilitate analyte concentration and enhance the optical signal for PFAS detection. Although several iron oxide phases are reported in the literature, only the maghemite (γ-Fe2O3) and magnetite (Fe3O4), with ferrimagnetic properties, and hematite (α-Fe2O3), with weak ferromagnetic characteristics, are commonly used [41,42]. In principle, IONPs must first be functionalized with ligands to enhance their binding affinity to target PFAS molecules. For this purpose, polydopamine, crown ether, cyclodextrin, calixarene, etc., can be used. Another approach is to create a deep eutectic solvent that is carefully designed to balance anion exchange and hydrogen-bond interactions. The synergistic interaction between halogen and hydrogen bonds led to the enrichment of PFASs, enabling successful detection. Also, amino-functionalized magnetic covalent organic frameworks nanocomposites, due to the hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions between these nanocomposites and PFAS, exhibit excellent adsorption for PFAS detection [43]. Modification and functionalization of IONP are also needed because they tend to lose magnetism. However, most modified magnetic nanoparticles are difficult to prepare and cannot be reused multiple times [44].

Carbon dots (CDs) are carbon-based nanoparticles that are highly luminescent, affordable, easy to obtain, water soluble, (photo)stable, and safe to use [45]. The complex structure is highly dependent on the precursors and synthetic conditions. CDs are typically sized between 1 and 10 nm and present a spherical or quasi-spherical shape. The oxygen functionals, such as -OH, -COOH, CHO, are present on their surface. The cores of CDs are mainly composed of sp2 carbon or graphene/graphene oxide sheets connected by sp3 carbon atoms in between, making a diamond-like array. Similarly to other types of nanoparticles, CDs can be used as fluorescent sensors for PFAS detection. For example, the quenching phenomenon can be attributed to the formation of an excited-state complex between the co-doped CDs and PFOA, with the reduction in emission intensity resulting from internal electron transfers within the complex [46]. CD has a high affinity towards PFASs, which was also confirmed by Lewis et al., who revealed that positively charged polyethyleneimine-based CDs interact with PFOA via electrostatic interactions. Due to interaction with PFOA, the CDs size increased, and their surface charge decreased, as revealed by 19F NMR spectral analysis. A slow-to-intermediate chemical exchange between the CDs and PFOA was detected, indicating a high-affinity interaction, suitable for PFAS sensors [47].

Molecular imprinting is a process where a polymer is made in the presence of a target molecule, so that the polymer forms tiny recognition sites shaped exactly for that molecule. These molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) are attractive because they are cheap, easy to make, stable, and can act like artificial receptors, similar to antibodies but more durable [25]. Most MIP-based sensors detect target binding through a measurable optical or electrochemical signal. The sensitivity of MIP-based sensors can be improved by compositing with nanomaterials like graphene oxide, carbon nanotubes, or nanoparticles [48]. Several groups have investigated the use of MIPs for the electrochemical recognition and detection of PFAS. Voltammetry is a widely used and versatile technique for this purpose. However, since PFAS are electrochemically inactive, indirect voltammetric approaches are typically used for their detection. A key part of indirect voltammetric PFAS detection is the addition of a recognition layer, usually made of MIP, to the working electrode. This layer lets the redox probe pass freely but can be blocked by PFAS. Besides voltammetry, PFAS detection is also commonly performed using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS). This technique monitors changes in the electrode’s impedance when PFAS molecules bind to surface recognition layers such as MIPs, which allow redox molecules to move but are blocked by PFAS [49].

Metal–organic frameworks (MOFs), thanks to their high porosity, tunable surface chemistry, and selective binding interactions, enable efficient PFAS capture through electrostatic, hydrogen bonding, and fluorophilic interactions, offering innovative approaches for PFAS sensing [50,51].

MXenes are a class of two-dimensional materials composed of transition metal carbides, nitrides, and carbonitrides. They are made of stacked Mn+1Xn layers, with the general formula Mn+1XnTx (n = 1–4), where M is a transition metal, X is carbon and/or nitrogen, and Tx represents surface terminations. The value of n indicates the number of transition metal layers. MXenes are typically synthesized from MAX phase precursors. To date, more than 50 stoichiometric MXene compositions have been reported, with ongoing research expanding this material family. Due to their combination of structural and chemical properties, MXenes have been applied in various fields. In particular, MXene-based polymeric membranes have demonstrated effective removal of various PFAS molecules from water. Incorporating MXenes into polymeric membranes enhances PFAS removal, but challenges remain, including scalable implementation, efficient synthesis, understanding PFAS-membrane interactions, and techno-economic evaluation [52].

A way to functionalize nanomaterials for selective biosensing is the incorporation of aptamers, short single-stranded DNA or RNA sequences that fold into specific three-dimensional structures and bind selectively to target molecules. They are obtained in vitro using a selection method that allows the identification of high-affinity binding sequences from large libraries of randomly synthesized oligonucleotides. The designed aptamers can bind to target molecules through different mechanisms, including induced fit, structural complementarity, electrostatic interactions, and hydrogen bonding [38]. Due to their chemical stability, low production costs, and ease of modification, aptamers are increasingly being explored as alternatives to antibodies in biosensor development. Wang et al. discuss the potential of aptamers to serve as effective recognition elements in biosensors for environmental monitoring, particularly for low molecular weight pollutants in water sources [53]. Therefore, aptasensors hold potential for PFAS screening in water; however, to date, and to the best of our knowledge, there is very limited literature on PFAS-sensitive aptamers compared to other detection approaches [54].

4. New Strategies to Enhance Sensitivity, Selectivity, and Reliability

4.1. Metal Nanoparticle

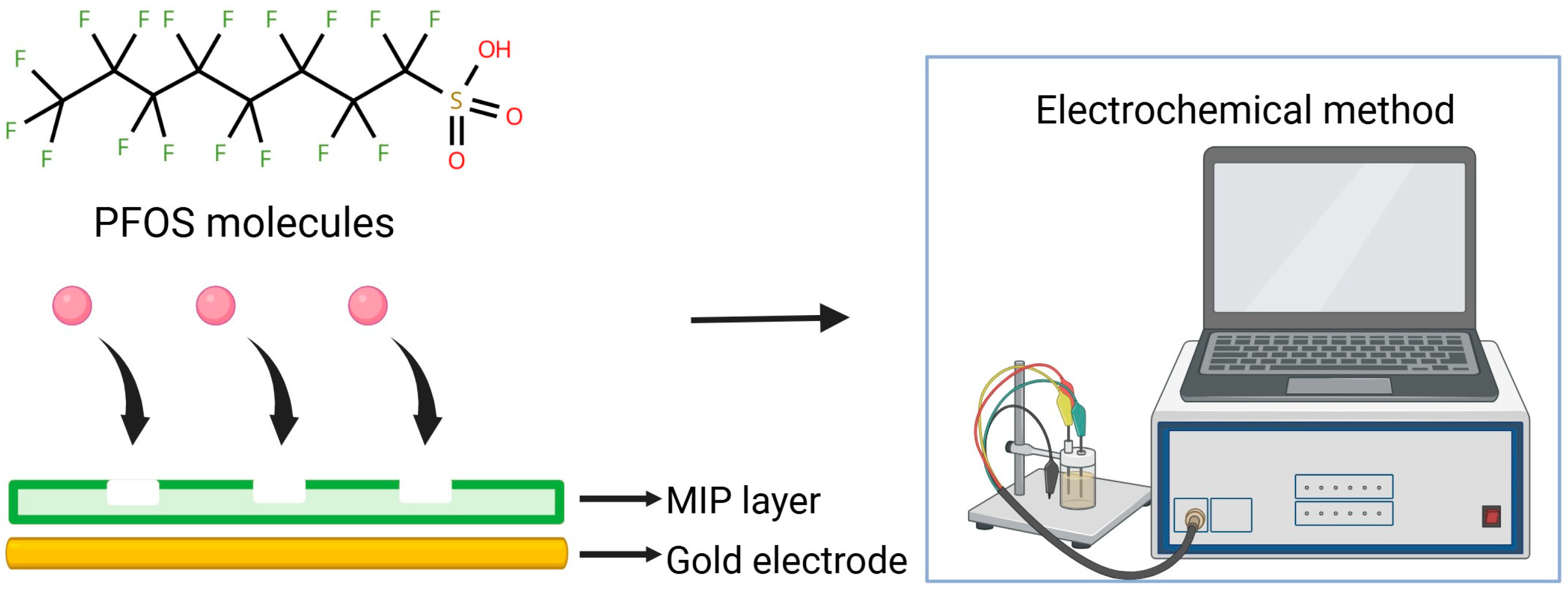

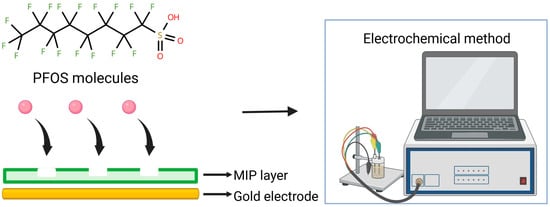

An effective strategy for improving the selectivity and stability of PFAS sensors involves coupling metal nanoparticles with molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs), which provide specific recognition sites tailored for PFAS molecules (Figure 3). Based on the work of Karimian et al. (2018) [55], where PFOS was detected using MIP through competition with an electroactive reporter probe, subsequent studies have advanced this concept. The sensor developed by Karimian et al. was based on a gold electrode modified with a thin MIP coating. Subsequent studies have proposed two main directions for improvement: (i) increasing the electroactive surface area of electrodes through the incorporation of porous or nanoscale materials, and (ii) stabilizing the MIP structure while enhancing its adsorption capacity. For instance, Lu et al. reported the development of an MIP-based sensor using a glassy carbon electrode modified with a thin layer of gold nanostars (AuNS). The AuNS layer amplified the voltammetric signal associated with Fe2+ oxidation of the ferrocenecarboxylic acid (FcCOOH) redox probe, while statistical optimization of the MIP layer led to a more pronounced peak response. The sensor achieved a limit of detection (LOD) of 7.5 ppt and a limit of quantification (LOQ) of 20.5 ppt for PFOS. Interference studies showed approximately 10% underestimation when equimolar perfluorobutanoic acid (PFBA) or perfluorobutanesulfonic acid (PFBS) was present. In contrast, typical constituents of drinking water, such as humic acid and chloride ions, had a negligible influence on the accuracy and reproducibility of the voltammetric measurements [56]. Stabilizing the structure and enhancing the adsorption capacity of MIPs are important steps for reproducibility and sensitivity in PFAS detection. In this context, studies have explored how fabrication parameters (i.e., potential window, scan rate, and molar ratio) can affect the mechanical properties and sensing reliability. Recent advances by Cheng et al. have documented that MIPs containing dual-functional monomers (DMs) offer improved sensitivity for detecting PFOA compared to those made with monofunctional monomers. This enhancement is likely due to stronger complementary interactions with the target molecules [57]. The study by Malloy et al. provided a deeper insight into sensor characteristics, i.e., irreversibility in the sensing signal over multiple cycles [58].

Figure 3.

Schematic illustration of PFOS molecules binding to MIP layer on gold electrode, later detected with different electrochemical methods.

A recent study explored an innovative solution involving MIPs created by near-field photopolymerization and subsequently grafted onto a gold-coated plastic optical fiber (POF). This process was enhanced by near-field light through surface plasmon resonance (SPR). The nanoscale functionalization of POFs with MIPs enhances access to specific binding sites and optimizes interactions with surface plasmons. By changing the thickness of the MIPs through controlled light exposure, the researchers achieved remarkably low LODs ranging from 2.2 × 10−8 ppt to 2.6 ppt. The selectivity of the POF@MIP sensors tested in the study is outstanding, showing no response to two analogs, even at concentrations 100 times higher than PFOA. This PFAS sensor, utilizing SPR, is the first to achieve a limit of detection LOD in the attomolar range, allowing it to meet future, even more demanding requirements [59].

In the study conducted by Amin et al., a MIP on a gold interdigitated microelectrode chip serves as a recognition element for selective capture of PFOS. A system is designed to work with a predetermined AC signal applied to a sensor, which accelerates PFOS molecules toward the sensing surface for binding. At the same time, the system monitors changes in interfacial capacitance during this process, allowing for real-time detection with extremely high sensitivity. The analytical parameters of this sensing system include a limit of LOD of 5 × 10−7 ppt within 10 s, a linear detection range from 5 × 10−7 to 5 × 10−4 ppt, and high selectivity in phosphate-buffered saline, even in the presence of other PFAS compounds, including PFOA [60].

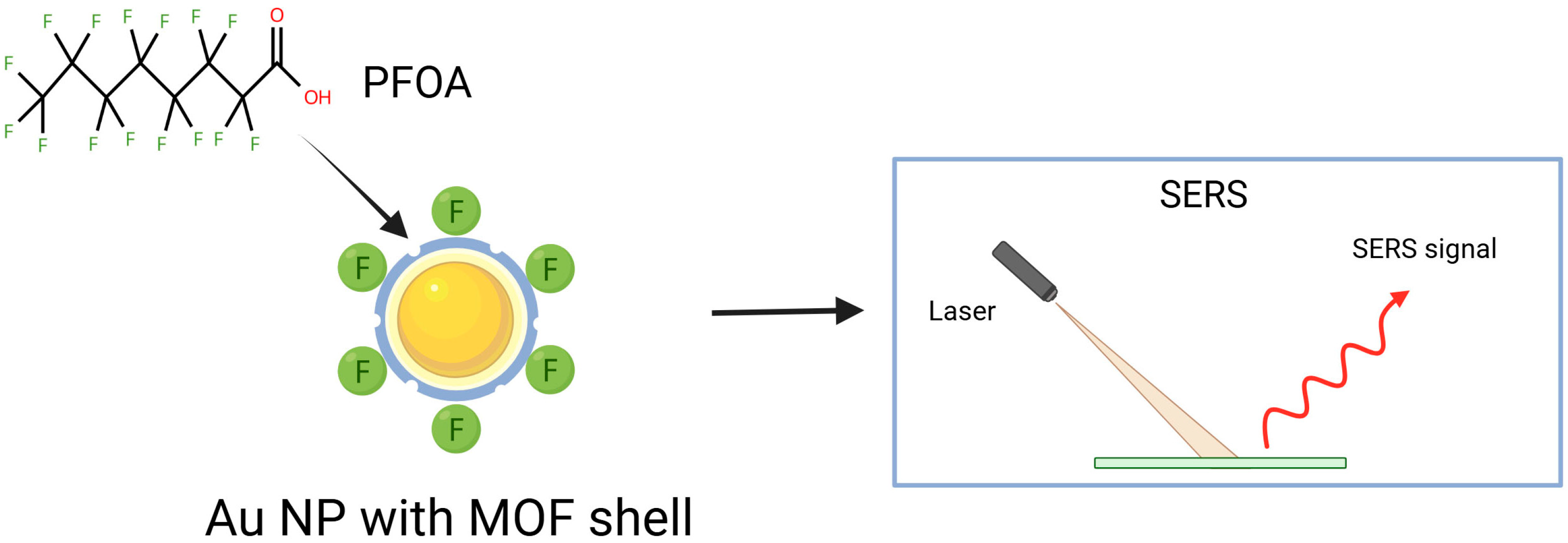

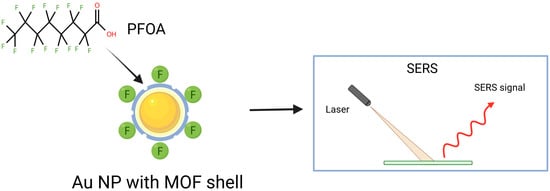

Another example demonstrating how gold nanoparticles enhance the reproducibility and stability in PFAS detection is Au@MIL-4F. This SERS material was prepared by functionalizing Au nanoparticles (AuNPs) with a fluorinated MOF (F-MOF) shell through thioglycolic acid ligands [61].

Generally, SERS-based PFAS detection (Figure 4) faces three key problems: (i) the need for highly enhancing substrates to achieve low detection limits, (ii) weak and variable PFAS affinity toward different SERS surfaces, and (iii) the difficulty of distinguishing spectra of PFAS compounds with very similar molecular structures. The proposed approach produced a hydrophobic, porous shell structure capable of selectively adsorbing and detecting PFOA. Besides highly sensitive SERS detection with LOD of 15.7 ppt for PFOA, excellent reproducibility and stability are achieved. This system also exhibits efficient adsorption of PFOA, with a maximum adsorption capacity of 254 mg/g on Au@MIL-4F. The Au@MIL-4F material adsorbs PFOA due to its hydrophobic nature, electrostatic interactions, and the large specific surface area provided by the MOF structure. The developed system offers precise and sustainable environmental remediation of PFOA [61]. Recently, combining Raman and SERS using silver nanorod (AgNR) substrates with machine learning gives a novel strategy for PFAS detection [62,63]. Raman spectra enable the identification of individual PFAS, whereas SERS, without clear resolution of PFAS bands, detects spectral changes upon PFAS adsorption. Spectral changes and vector-based models enable the sensitive differentiation and quantification of PFAS, with detection limits of approximately one ppt for PFOA and about four ppt for PFOS. Integration of machine learning techniques, differentiation and quantification of PFOA in water by using SERS can also be helpful [63]. Surface modification of the AgNR substrates with various alkanethiols improved discrimination, despite the dominance of alkanethiol signals. This approach may be a route for the preparation of portable, field-deployable PFAS sensors [63].

Figure 4.

Schematic illustration of PFOA binding to AuNP with a fluorinated MOF shell, detected via SERS.

PFOA can be detected using an electrochemical sensor constructed from a self-assembled monolayer of 1H,1H,2H,2H-perfluorodecanethiol (PFDT) on gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) electrodeposited onto a glassy carbon electrode (GCE). The AuNPs coating the GCE had an average particle size of approximately 16 nm and covered 39% of the electrode surface. Quantification of PFOA was carried out using square wave adsorptive cathodic stripping voltammetry. PFOA concentration showed a linear correlation with the stripping current over the range of 100 to 5000 ppt, with a LOD of 24 ppt and a LOQ of 80 ppt. Testing in tap and brackish water samples, spiked with known PFOA concentrations, demonstrated precision and accuracy exceeding 95%. The nano-enabled electrode remained stable for at least 200 cycles and was successfully applied to measure PFOA in both tap and brackish water. A key advantage of this sensor is its selectivity, which enables accurate PFOA determination even in the presence of other perfluoroalkyl substances, with recoveries ranging from 90 to 110% [64].

A special feature of advanced PFAS detection methods is the sensor ability to identify and respond to multiple PFAS types, including perfluorocarboxylates of different chain lengths (PFHxA, PFOA, PFNA, PFDA), perfluorooctanesulfonate (PFOS), and perfluorooctyl phosphonate (PFOPA). Jung et al. developed a colorimetric sensor using citrate-coated gold nanoparticles (Citrate-AuNPs) functionalized with a perfluoroalkyl receptor. Fluorous interactions between PFAS and the receptor on Citrate–Au NPs caused changes in nanoparticle dispersion and solution color, enabling detection. By adjusting the citrate-to-gold molar ratio, Citrate–Au NPs with sizes from 29 to 109 nm were produced, with 78 nm particles showing the highest sensitivity to PFOA, allowing detection down to 2.06 × 106 ppt. Sensitivity increased with longer perfluoroalkyl chains and when the functional group was sulfonate rather than carboxylate or phosphonate [65].

Bimetallic nanoparticles have also been used in PFAS sensors. The Au–Pt bimetallic system shows enhanced electrocatalytic performance due to synergistic electronic and structural effects. Gold domains improve electron transport, while interfacial interactions modify Pt sites, reducing charge-transfer resistance. Incorporating these bimetallic nanoparticles into carbon-based materials further boosts electrochemical signals [66]. Wan et al. developed a molecularly imprinted electrochemical sensor (MIECS) integrating nitrogen-doped graphene oxide nanoribbons (N-GONRs) with gold-platinum bimetallic nanoparticles (Au–Pt NPs), achieving a LOD of 0.96 ppt for PFOS and demonstrating good recoveries in various real sample matrices. The highly conductive N-GONRs offered a large surface area and numerous active sites, promoting PFOS adsorption and supporting the formation of densely packed imprinted cavities. When integrated with Au–Pt nanoparticles, the hybrid interface further improved electrochemical signal transduction by enhancing interfacial electron transfer. This sensor design enabled a wide detection range of 1–106 ppt and an extremely low LOD of 0.385 ppt, which is below the USEPA regulatory limit for PFOS in drinking water [66].

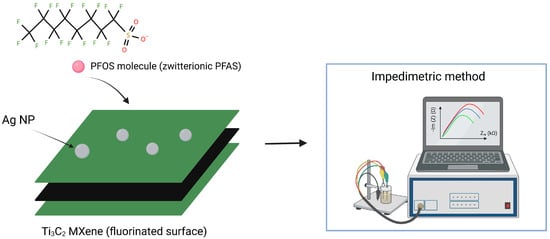

4.2. MXenes

MXenes (Ti3C2) have emerged as a highly promising material for the interaction with zwitterionic PFAS in contaminated water, at near-neutral pH (~7) [67]. Based on MXene, Khan et al. developed a low-cost sensor capable of detecting PFOS at parts-per-quadrillion (ppq) levels within 5 min. The method relies on PFOS binding to silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) embedded in a fluorine-rich Ti3C2 MXene, which provides a large surface area and accessible binding sites for direct impedimetric detection [62].

Generally, fluorine⋯fluorine (F⋯F) contacts lead to pronounced dipole–dipole interactions with PFAS, which are critical for its removal from water using fluorosorbents. Additionally, certain sorption mechanisms enhance both the selectivity and capacity for PFAS adsorption. For instance, electrostatic interactions occur between the charged regions of the sorbent and the anionic or cationic moieties of PFAS molecules. Integrating electrostatic interactions with F⋯F interactions can overcome their limitations, such as a narrow operational range and reduced effectiveness at low PFAS concentrations. In this combined mechanism, electrostatic forces first attract anionic PFAS molecules toward the positively charged sites on the fluorosorbent, orienting their fluorinated chains favorably toward the fluorinated surfaces. Subsequently, these fluorinated segments form strong F⋯F interactions with the sorbent, resulting in enhanced and more selective sorption [67].

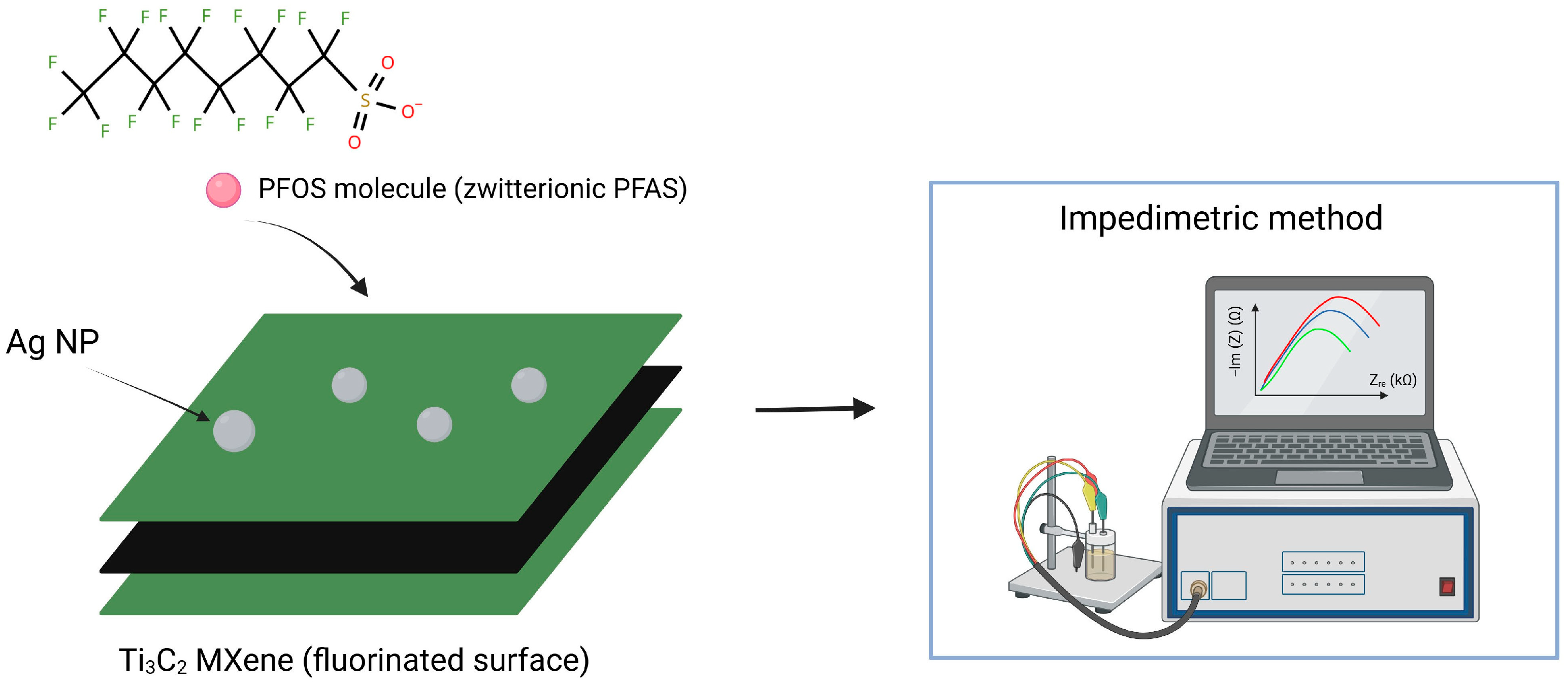

The MXene-AgNPs system binds PFOS and other long-chain PFAS through a synergistic combination of electrostatic and F⋯F interactions (Figure 5). This binding induces concentration-dependent changes in charge-transfer resistance, allowing rapid, direct quantification with extremely high sensitivity and minimal interference. The sensor exhibits a linear range from 50 ppq to 1.6 ppt, with a LOD of 33 ppq and a LOQ of 99 ppq, making it a promising candidate for low-cost, straightforward screening of PFAS in water samples [62].

Figure 5.

Schematic illustration of Ti3C2 MXene capturing PFOS molecules and the detection method.

A carbon paste electrode modified with MAXphase, Mo2Ti2AlC3, has been designed for PFOS electrochemical detection under acidic conditions. Owing to the specific properties of the MAX phase, such as high electrical conductivity, chemical stability, and large surface area for adsorption, the developed sensor enables rapid, precise, and selective determination of PFOS in complex matrices. EIS analysis revealed a significant increase in charge transfer resistance (Rct) in the presence of PFOS, indicating an adsorption-controlled process, while cyclic voltammetry at various scan rates confirmed that the oxidation mechanism of PFOS involves both diffusion and adsorption. At higher scan rates, shifts in peak potentials and increased oxidation currents were observed, which are characteristic of irreversible, kinetically controlled reactions involving radical intermediates. Additionally, the surface coverage and the number of transferred electrons further confirm the efficiency and charge transfer mechanism at the modified electrode surface. Quantification of PFOS through the amperometric method demonstrated two linear concentration ranges: 500–4.5 × 104 ppt and 4.55 × 105–2.59 × 107 ppt, with a LOD of 16.6 ppt, indicating the sensor’s high sensitivity and suitability for detecting both trace and elevated PFOS levels [68].

Well-established regulatory rules for hydrophobic, long-chain PFAS have led to their decline in the environment over time. However, trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and other ultra-short-chain PFAS, due to their acidity and hydrophilicity, have a tendency to accumulate in water, so their quantification and removal represent a challenge and necessity nowadays. For the detection purpose of TFA, Lu et al. developed a sensor based on UiO-66-F4/MIP@Ti3C2Tx, which plays as a triple action system: UiO-66-F4 thanks to F⋯F interactions caused TFA enrichment; MIPs prevent interferences exclusion, and Ti3C2Tx MXene multiple charge transfer. The analytical parameters of the created sensing platform, such as a TFA detection limit of 6.94 ppm with a linear range of 0.01 to 100 ppb in environmental water samples, exhibit superior performance compared to previously reported sensors and even to GC-MS, which is the recommended method [69].

4.3. MOF

Chang et al. recently used the mesoporous MOF, Cr-MIL-101 as a probe for targeted PFOS capture, taking advantage of the chromium center affinity for both the fluorine tail and the sulfonate groups. This study presents an affinity-based electrochemical sensor, achieving very high sensitivity, as low as 0.5 ppt, through a combination of receptor probes, electrode configuration, and integration within a lab-on-a-chip platform [51].

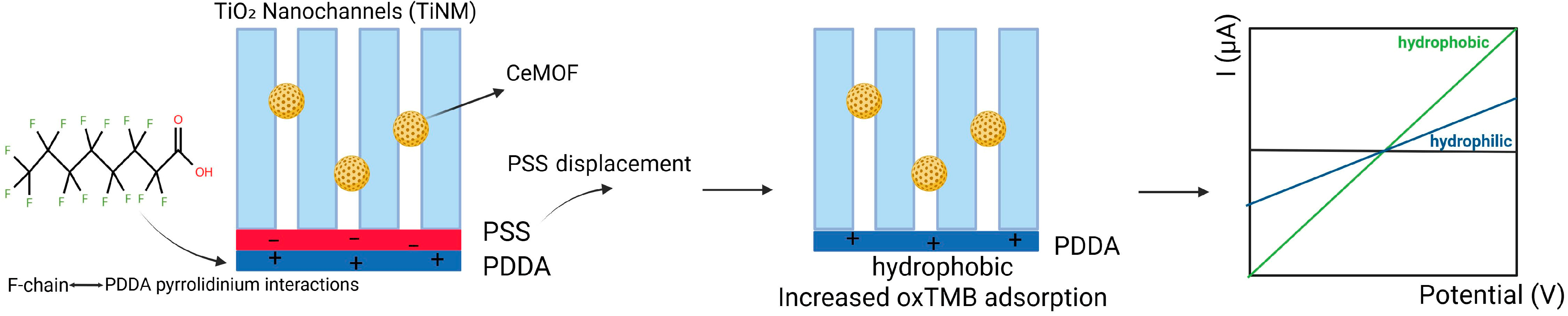

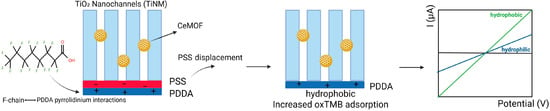

A study by Su et al. reports an electrochemical sensor for detecting PFOA based on the changes in the activity of nanozyme in TiO2 nanochannels. Besides the sensitivity and short response time in PFOA detection, the system enables distinction between different carbon chain lengths of PFAS. The sensing platform is designed as follows: a peroxidase-like active Ce-based MOF (CeMOF), developed on nanochannel membranes made of TiO2 (TiNM), serving as the catalytic center. A film composed of poly (diallyldimethylammonium) (PDDA) and poly (styrenesulfonate) (PSS) layers adjusts the surface of nanochannels, creating a responsive polyelectrolyte-functionalized TiO2 nanochannels membrane (Figure 6). The intricate interactions between the fluorinated chains of PFOA and the pyrrolidinium rings embedded within the PDDA framework result in the displacement of the PSS layer. This displacement transforms the nanochannels into a hydrophobic environment, significantly enhancing the adsorption of oxidized tetramethylbenzidine. This subsequently impairs the catalytic activity of CeMOF, underscoring the complex interplay between these molecular components. This creative platform achieves a detection limit of 32.3 ppt and a wide linear range between 103.5 and 414.1 × 106 ppt. This portable sensor enables field measurements of PFAS levels [70].

Figure 6.

Schematic illustration of peroxidase-like active Ce-based MOF in TiO2 nanochannels, with PSS and PDDA on the surface of nanochannels; transformation of nanochannels into a hydrophobic environment, and the potentiometric signal of the hydrophilic and hydrophobic surface.

4.4. Magnetic Nanoparticles

A recent study reported the design of an optical sensing and removal platform (EB@Fe3O4) for PFOS detection. The system employed Erythrosin B (EB) as the probe, incorporated into a Fe3O4-silica core–shell carrier. The sensing mechanism was based on the photophysical response of EB to PFOS, including changes in absorption, emission spectra, and quantum yield. In the presence of CTAB, an emission turn-on effect was observed due to the interaction of EB:CTAB micelles with PFOS. The platform demonstrated a linear fluorescence response in the 0–7.0 × 106 ppt PFOS range, achieving a LOD of 1.20 × 105 ppt and high selectivity (except against PFOA). Additionally, EB@Fe3O4 exhibited PFOS removal capability with an adsorption capacity of 0.115 mg/g [71].

Similarly, a Fe3O4@MCM-41/EY composite demonstrated dual functionality with a linear fluorescence response (LOD 1.35 × 105 ppt) and a PFOS adsorption capacity of 0.126 mg/g. A synthesized composite consists of Eosin Y and cetyltrimethylammonium bromide serving as the detection probe, featuring Fe3O4 nanoparticles as the central component, along with an MCM-41 silica shell. This design facilitates simultaneous sensing and adsorption, effectively contributing to the removal of PFOS [72].

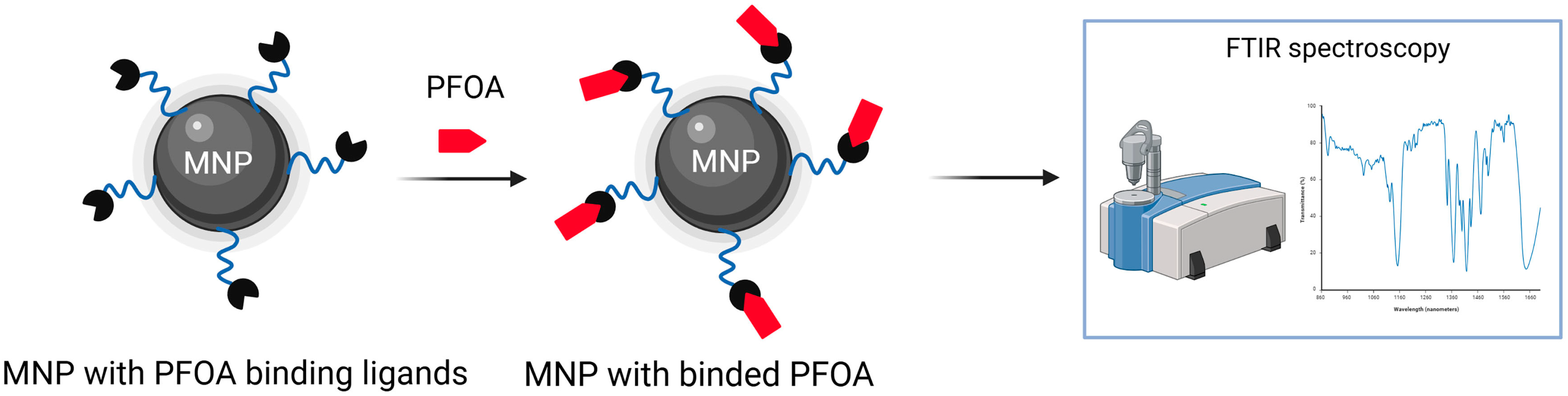

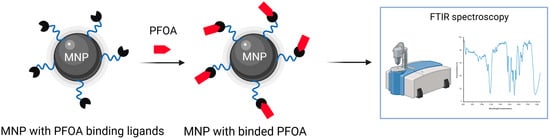

Zhang et al. proposed a sensing system utilizing Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticles modified with three different ligand systems (poly (ethylene glycol) (PEG), β-cyclodextrin (βCD), or dopamine (DA)), engineered for recognition and detection of water-soluble PFOA, Figure 7. These functionalized nanoparticles can be efficiently reused, retaining more than 90% of their activity after several operations. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy within platform enables identification of PFOA down to concentrations of 125 µg/mL (1.25 × 108 ppt). Furthermore, the inclusion of PEG ligands on the nanoparticle surface considerably strengthens their interaction with PFOA molecules, achieving over 90% removal efficiency even at concentrations as high as 10 µg/mL (1.0 × 107 ppt). The PEG structure enables intramolecular forces, dipole–dipole, and hydrogen bonding with both the hydrophobic and polar parts of the PFOA molecule. In comparison, DA functionalized magnetic nanoparticles interact through electrostatic attraction and hydrogen bonding, while βCD modification leads to lower efficiency, due to steric hindrance and poor compatibility between the βCD cavity and the structure of the PFOA molecule. The proposed sensor configuration has not yet been refined for detecting ultra-trace levels of PFOA [73].

Figure 7.

Schematic illustration of MNP with PFOA binding ligands, binding of PFOA and the FTIR method used to detect PFOA.

Chen et al. developed a conjugated polymer material combined with a magnetic adsorbent for the sensitive detection and magnetic removal of PFOA and PFOS. Surface-modified iron oxide nanoparticles, Fe3O4@NH2&F13, which possess structural features resembling those of PFOS and PFOA, were used as an effective adsorbent together with a donor-acceptor conjugated polymer, enabling instantaneous and robust magnetic removal of PFAS. This ratiometric fluorescent probe allows selective visual detection of PFOA and PFOS, achieving ultra-low detection limits of 2.53 ppt and 7.15 ppt, respectively. The addition of PFOA or PFOS induces a color change in the polymer solution from blue to magenta, enabling even naked-eye ratiometric detection of these contaminants. This phenomenon formed the basis for a portable detection system using a handheld smartphone device for rapid field estimation of PFOA and PFOS [74].

4.5. Carbon Nanostructures

Besides gold nanoparticles, it has been discovered that diamond-rich carbon nanostructures can produce a specific profile of binding sites in the MIPs, leading to an expressed affinity for PFOS. The improved selectivity and sensitivity of such a designed PFOS sensor enable a low LOD (1200 ppt), with satisfactory selectivity and stability. The molecular interactions between diamond-rich carbon surfaces, electropolymerized MIP, and PFOS are essential for predicting the final characteristics of a possible in situ PFOS monitoring. The sp2-carbon-rich B/N-doped carbon nanowalls substrate provides a larger effective adsorption area owing to its taller structures, which benefits the formation of the MIP layer. Its highly developed porosity does not interfere with the electropolymerization process. Even at a substantial thickness below 4 µm, the coating is deposited uniformly, as confirmed by the correlation between the baseline current (measured without PFOS) and the current limit associated with the number of binding sites [75].

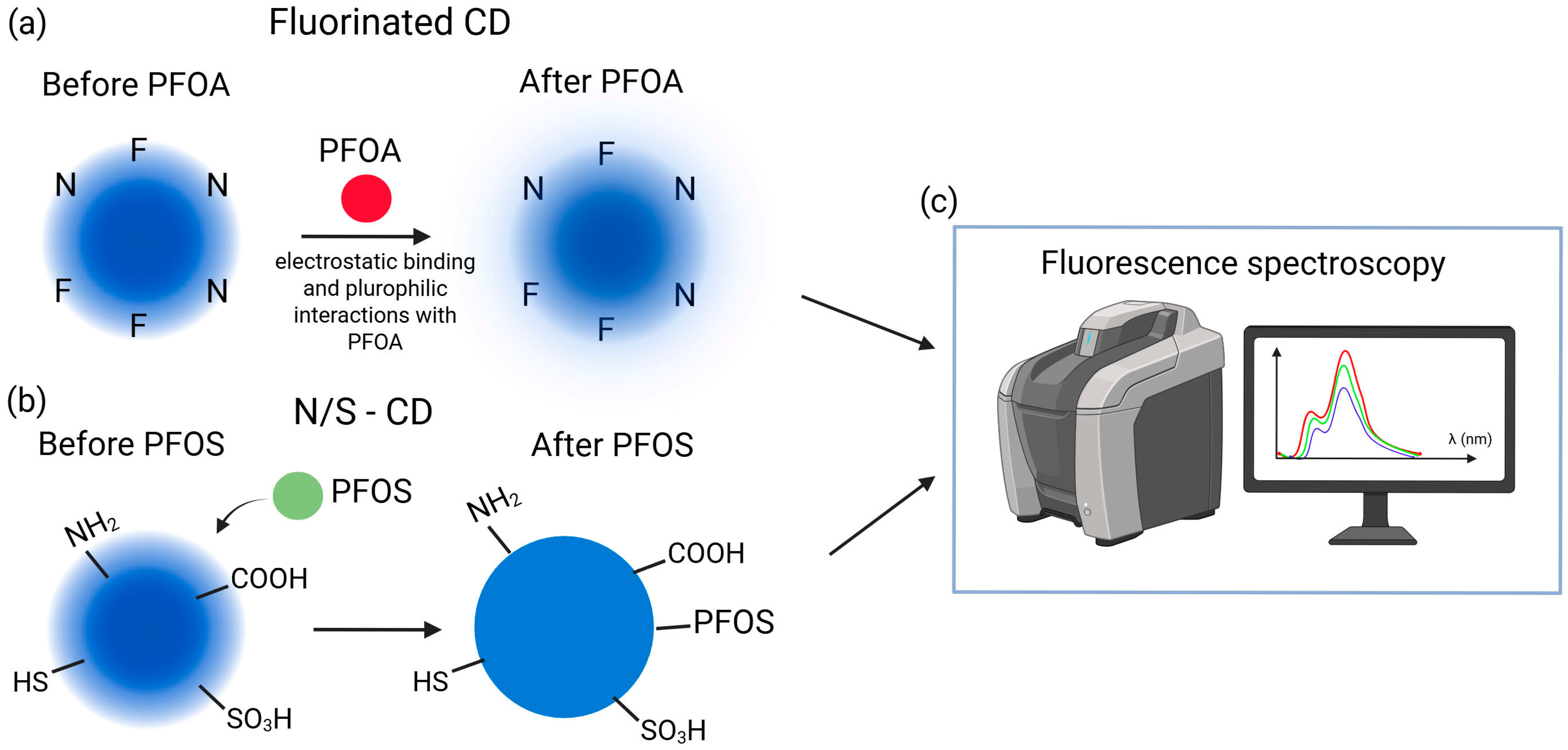

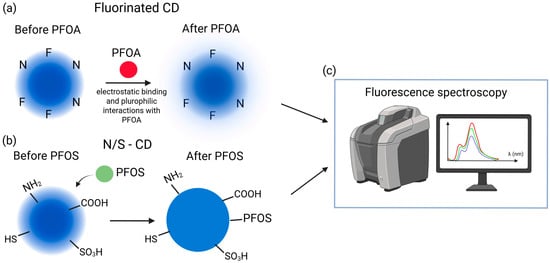

A fluorescence probe based on fluorinated carbon dots (F-CDs) was designed for PFAS detection in water, with PFOA as the target marker (Figure 8a). The optimized N/F ratio yielded positively charged F-CDs (~4.2 nm), where electrostatic and fluorophilic interactions enabled highly sensitive detection (10–1660 ppt, LOD 3 ppt). The method proved selective among multiple PFAS, effective in groundwater samples, and was noted for its simplicity, low cost, and potential for further enhancement via DFT studies and hybrid nanostructures [76]. Similarly, nitrogen and sulfur co-doped carbon dots (N/S-CDs) synthesized via a simple, eco-friendly hydrothermal method using L-cysteine exhibited heteroatom-functionalized surfaces (amine, carboxyl, thiol, sulfonic acid) and nanoscale dimensions (1–8 nm, average 2.6 nm), Figure 8b. The N/S-CDs displayed intense blue fluorescence with excitation-dependent emission (Figure 8c) and enabled concentration-dependent detection of PFOS with a linear range of 1.67 × 106–1 × 107 ppt and LOD of 1 × 106 ppt. Spectroscopic analyses indicated that non-covalent interactions, primarily electrostatic and hydrophobic forces, governed the sensing mechanism [77].

Figure 8.

(a) Schematic illustration of fluorinated CD before and after the binding of PFOA [67]; (b) Schematic illustration of N/S-CD before and after PFOS influence; (c) Fluorescence spectroscopy as a detection method of PFOA and PFOS.

4.6. Nanomaterials Functionalized with Aptamers

Through aptamer functionalization, Nie et al. developed a portable and intelligent device for real-time onsite analysis of atmospheric PFOA [78]. The sensor utilizes PtCo nanoparticles supported on graphitic carbon nitride (PtCoNPs@g-C3N4) with oxidase-like activity, which is regulated by a PFOA-specific DNA aptamer. The binding of PFOA causes dissociation of the aptamer from the nanozyme surface, restoring its oxidase-like function to oxidize o-phenylenediamine (OPD) into a fluorescent and colorimetric product, enabling dual-mode detection. A hydrogel-based sensing system combining Apt-PtCoNPs@g-C3N4 and OPD integrated into a portable device, which automatically processes colorimetric and fluorescence signals using custom software. This approach enables sensitive, real-time monitoring of atmospheric PFOA near fluorochemical plants, offering a foundation for developing onsite detection systems for various airborne pollutants.

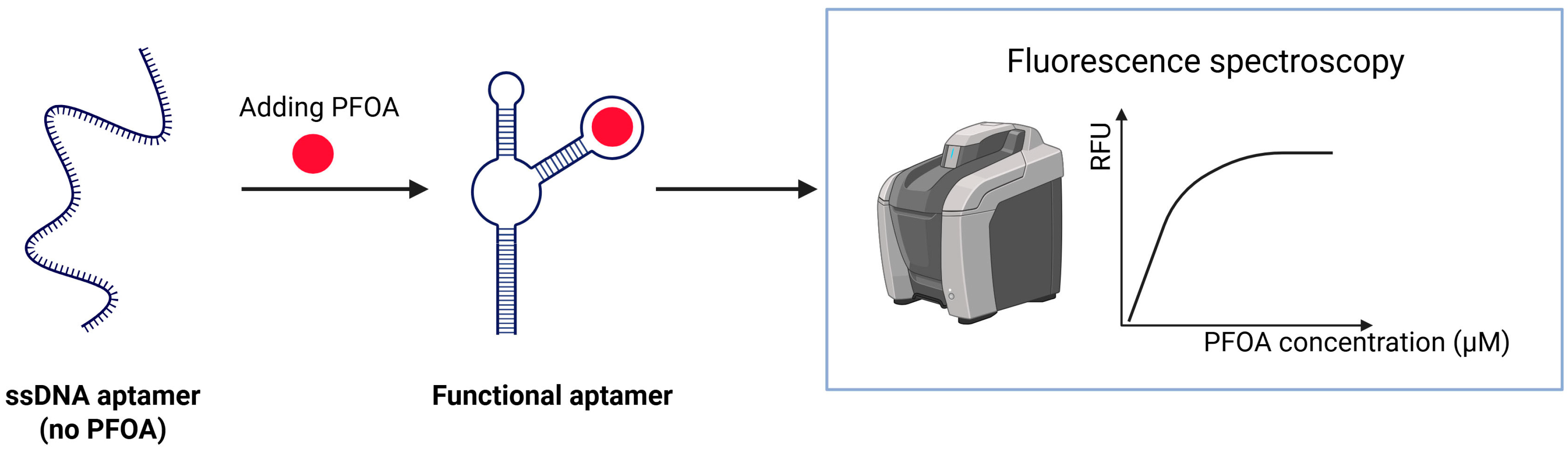

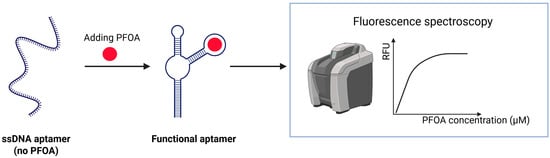

Park et al. reported the first successful isolation of single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) aptamers that selectively bind PFAS, showing strong affinity for PFOA (dissociation constant = 5.5 μM) and related compounds. Fluorescence-based aptasensor capable of detecting PFOA in water, with a detection limit of 7.04 × 104 ppt. The aptamer undergoes a conformational change upon binding to PFOA, which affects the fluorescence and enables measurement. Binding was more strongly influenced by the length of the fluorinated carbon chain than by functional groups. The sensor (Figure 9) demonstrated strong specificity and selective binding to PFAS with long alkyl chains, and minimal interference from common ions or organic matter, and stable performance in real wastewater [79].

Figure 9.

Schematic illustration of an ssDNA aptamer developed for PFAS detection.

In a more recent study, Park et al. used molecular dynamics simulations and sequence truncation analyses to show that the structural features responsible for selective recognition are the length of the perfluorinated carbon chain and the sulfonate group. PFOS uniquely forms specific interactions, such as a hydrogen bond and a π-sulfur bond, with the aptamer, which are not observed in shorter-chain or hydrocarbon analogs. These insights indicate that both the fluorocarbon backbone and sulfonate moiety act as critical epitopes for high affinity and specificity. The authors used gold nanoparticles coated with a synthesized PFOS_JYP_6 aptamer for quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) quantification of PFAS. A dissociation constant for PFOS of 6.78 μM, indicating moderate affinity. Selectivity tests have demonstrated that these aptamers do not bind significantly to other PFAS compounds, confirming their high specificity. The aptamer-based qPCR assay exhibits high sensitivity for PFOS detection, with a LOD of 5.8 pM (2.9 ppt), facilitating ultra-trace analysis. This may be an advanced option for PFAS detection in real water samples without complex sample preparation [80].

Li et al. developed a novel aptamer-functionalized sensor system known as an aptapipette, designed for highly sensitive detection of PFOA [81]. The sensor uses a glass nanopipette modified with silica nanowires, then aminated and functionalized with a PFOA-specific DNA aptamer for selective binding. Detection is achieved by measuring changes in ion transport through the nanopipette tip upon PFOA binding, using linear sweep voltammetry to record electrical signals. The system demonstrated a broad linear detection range 1–104 ppt, with a LOD as low as 0.35 ppt. Compared to conventional analytical techniques such as LC-MS/MS, the aptapipette offers a significantly simpler and faster alternative for PFOA detection in environmental monitoring.

4.7. Other Nanostructures

A SERS sensor for PFOA was reported using self-assembled p-phenylenediamine nanoparticles on a silver nanograss SERS substrate. Interaction with PFOA caused a decrease in SERS signal, which was further amplified by the Ag substrate, enabling ultra-sensitive detection down to 0.53 ppt pM in distilled water [82].

Finding low-cost SERS substrates for high-throughput methods to detect environmental contaminants is another challenge that scientists have to address in PFAS optical sensors based on SERS spectra. The addition of graphene to SERS-based substrates, created through the aerosol jet printing of silver nanoparticles and graphene inks on Kapton films, greatly enhanced the SERS intensity of PFOA and PFOS molecules at a pH of 9 [83]. SERS spectra from nano- and picomolar (~0.4 ppt) concentrations of PFOA and PFOS, respectively, suggest that the designed substrate is suitable for the ultrasensitive detection of PFAS in the environment. Another important characteristic of the proposed aerosol jet printed SERS substrate is prolonged shelf life, with little reduction in fluorescein intensities, as a standard dye for SERS spectra testing, even after 9 months.

An example of a fluorescent sensor for PFAS with a very low LOD value for PFOS (1.4 ppb) was reported with perylene diimide-based sensors modified with cationic side groups at both imide positions [84]. The sensor operates in a fluorescence quenching mode, caused by molecular aggregation that occurs when a supramolecular complex forms between the fluorophore and PFOS.

Law et al. developed nanoporous anodic alumina (NAA) interferometers functionalized with perfluorosilanes of different chain lengths for real-time reflectometric detection of PFOA. Changes in effective optical thickness allowed quantification of PFOA binding, with perfluorooctyltriethoxysilane-modified NAA showing higher sensitivity (4.9 nm (µg mL−1)−1) and lower LOD (0.53 × 108 ppt) than perfluorodecyltriethoxysilane analogs. Adsorption was described using the Freundlich isotherm, indicating multilayer sorption via fluorous interactions and hemi-micelle formation. The sensor performed well in spiked ultrapure, tap, and river waters [85].

Recent developments in nanostructured PFAS sensors show improvements over earlier approaches. Nanomaterials are essential for PFAS sensing due to high surface area, tunable surface chemistry, and enhanced electronic/optical properties, which improve adsorption, recognition, and signal transduction. Nanomaterial-based sensors enable ultrasensitive and selective detection at ultra-trace levels, increase reproducibility and stability, and allow real-time or field-deployable measurements. Compared to earlier single-component sensors, nanomaterial-based platforms facilitate multifunctional capabilities, including simultaneous PFAS detection (and hopefully removal), marking a clear advancement toward practical and reliable environmental monitoring.

Although many PFAS sensors based on nanomaterials show excellent detection limits in laboratory conditions, there are certain systemic weaknesses that hinder application in real samples. Most studies rely on ultrapure water to which only a few PFAS molecules are added, which are used as model substances (usually PFOA and PFOS). Such practice overestimates sensor performance because complex matrices introduce competing adsorption, contamination, and optical/electrochemical interferences that can rarely be fully quantified. Additionally, given the complicated syntheses of nanomaterials, reproducibility is rarely tested, and variability in material preparation is to be expected. It is recommended that future studies focus on environmental samples, multiple types of PFAS molecules (taking into account chain length and charge), broad interference analysis (salinity, dissolved organic compounds), and stability testing. Only by adopting these practices can the reported ultra-low detection limits be reliably translated into field-useable sensor solutions.

An overview of nanomaterials applied in PFAS detection is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of nanomaterials applied in PFAS detection: formats, methods, targets, advantages, and challenges.

Different nanomaterials offer particular advantages/limitations for PFAS detection. Plasmonic nanostructures (e.g., Au and Ag NP) and MXene composites display excellent sensitivity due to strong surface-analyte interactions and signal amplification, resulting in the lowest reported LODs. MIPs and magnetic nanocomposites show exceptional selectivity and reusability, allowing targeted recognition and efficient separation of PFAS molecules from complex matrices. Nanocarbons make affordable, stable, and luminescent sensing platforms, although their performance can be influenced by matrix effects. Having in mind all advances in this field, reproducibility, stability, and validation in real environmental samples present major challenges.

5. Challenges and Perspectives

Nanomaterials offer a versatile platform for PFAS sensing, combining high surface area, strong adsorption capacity, and diverse detection modes such as electrochemical, optical, and magnetic approaches. Their advantages, ranging from high sensitivity and affordability (carbon nanomaterials) to easy separation and reusability (magnetic nanoparticles), make them promising candidates for rapid and portable detection of PFAS.

However, current challenges highlight the need for further innovation. Many nanomaterials still exhibit limited PFAS coverage, matrix interferences, and stability issues (e.g., fluorescence background in SERS or reproducibility in polymer-coated systems). Magnetic nanoparticles require improved functionalization to enhance selectivity, while metal oxides demand sorbents with tunable binding sites to detect a broader range of PFAS beyond PFOA/PFOS. There are still insufficient standardized protocols for comparing the performance of different sensors.

We can envision achievement of broader selectivity and lower detection limits in PFAS quantification through rational design of multifunctional nanomaterials that integrate two different, albeit concurrent, mechanisms of recognition and signal enhancement. Hybrid solutions, combining plasmonic and electroactive nanostructures can possibly provide synergies needed for improved selectivity, while molecularly imprinted and aptamer-based sensor systems can give tunability in detection of similar PFAS species. Among systems currently under study MX-ene and plasmonic based composites show the greatest promise for ultrasensitive detection, while MIPs and magnetic nanocomposites shine when selective extraction and reusability are needed. However, successful integration of these materials into advanced practical monitoring devices requires improvement of their reproducibility, stability, and validation in real environmental samples.

Future efforts should focus on designing hybrid nanomaterials that combine complementary properties, such as magnetic separation with high-affinity binding layers, to achieve broader selectivity and lower detection limits. Advanced surface engineering, machine-learning-guided sensor optimization, and scalable fabrication techniques will be critical to overcome reproducibility and matrix effects. Integrating these nanomaterials into miniaturized, field-deployable sensing devices will enable real-time PFAS monitoring in complex environmental samples, accelerating their transition from laboratory research to practical environmental surveillance and remediation.

6. Conclusions

A predominance of review articles over original research papers characterizes the current literature on PFAS sensing. This trend reflects the complexity of PFAS structures, the variety of this class, and the difficulty in their detection. Driven by new knowledge about the health toxicity of PFAS, regulatory requirements are becoming more stringent in terms of lowering acceptable limits for the presence of PFAS, making this interdisciplinary field more challenging. The importance of ultrasensitive sensors is also reflected in the assessment of the efficiency of removing PFAS from the environment. Nanomaterials, due to their properties, may serve not only for PFAS removal, as often investigated, but also as sophisticated sensing platforms for their detection. High experimental complexity, regulatory considerations, and the availability of expensive instrumentation pose challenges to rapid experimental progress in PFAS detection. Higher selectivity must be sought through integration of several PFAS sensing materials into one sensing element whose signal will be statistically or AI processed to obtain reliable and repeatable results on the ppt scale. Concurrent sensing will further decrease interference and noise, driving the sensitivity to the desired limits. Synthesizing existing findings must be coupled with advancements in state-of-the-art nanomaterials preparation and sensor development to meet current environmental needs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.B.-B. and S.U.-M.; methodology, A.G.; software, B.N.V.; validation, N.G. and D.B.-B.; formal analysis, A.G., A.J.L. and S.U.-M.; investigation, A.G., A.J.L. and N.G.; data curation, D.B.-B. and A.G.; writing—original draft preparation, D.B.-B., A.G. and M.M.-R.; writing—review and editing, N.G., M.M.-R. and D.B.-B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia (grant numbers 451-03-137/2025-03/200146, 451-03-136/2025-03/200146, 451-03-137/2025-03/200161, and 451-03-136/2025-03/200026) and supported by the Science Fund of the Republic of Serbia, GRANT No 17990, Advanced electrochemical treatment of PFAS contaminated water: Novel Materials and Mechanisms–ALTER.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used BioRender.com for the preparation of graphics. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Buck, R.C.; Franklin, J.; Berger, U.; Conder, J.M.; Cousins, I.T.; de Voogt, P.; Jensen, A.A.; Kannan, K.; Mabury, S.A.; van Leeuwen, S.P. Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in the Environment: Terminology, Classification, and Origins. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2011, 7, 513–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; DeWitt, J.C.; Higgins, C.P.; Cousins, I.T. A Never-Ending Story of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs)? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 2508–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glüge, J.; Scheringer, M.; Cousins, I.T.; DeWitt, J.C.; Goldenman, G.; Herzke, D.; Lohmann, R.; Ng, C.A.; Trier, X.; Wang, Z. An Overview of the Uses of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS). Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2020, 22, 2345–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megson, D.; Bruce-Vanderpuije, P.; Idowu, I.G.; Ekpe, O.D.; Sandau, C.D. A Systematic Review for Non-Targeted Analysis of per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS). Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 960, 178240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, L.; Cao, R.; Huang, Z.; Jin, J.; Du, Z.; Li, H. Efficiencies and Mechanisms of Remediation Techniques for Cationic and Zwitterionic Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) from Aqueous Environments: A Review. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 502, 158161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz, G.; Taxil-Paloc, A.; Desrosiers, M.; Vo Duy, S.; Liu, M.; Houde, M.; Liu, J.; Sauvé, S. Zwitterionic, Cationic, and Anionic PFAS in Freshwater Sediments from AFFF-Impacted and Non-Impacted Sites of Eastern Canada. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 484, 136634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, A.; Balan, S.A.; Scheringer, M.; Trier, X.; Goldenman, G.; Cousins, I.T.; Diamond, M.; Fletcher, T.; Higgins, C.; Lindeman, A.E.; et al. The Madrid Statement on Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs). Environ. Health Perspect. 2015, 123, A107–A111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vojnović, V.; Ranković, M.; Jevremović, A.; Mijailović, N.R.; Nedić Vasiljević, B.; Milojević-Rakić, M.; Bajuk-Bogdanović, D.; Gavrilov, N. Doping of Magnéli Phase—New Direction in Pollutant Degradation and Electrochemistry. Molecules 2025, 30, 4282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Teng, M.; Zhao, X.; Li, Y.; Sun, J.; Zhao, W.; Ruan, Y.; Leung, K.M.Y.; Wu, F. Insight into the Binding Model of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances to Proteins and Membranes. Environ. Int. 2023, 175, 107951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunderland, E.M.; Hu, X.C.; Dassuncao, C.; Tokranov, A.K.; Wagner, C.C.; Allen, J.G. A Review of the Pathways of Human Exposure to Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) and Present Understanding of Health Effects. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2019, 29, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Qiu, W.; Du, J.; Wan, Z.; Zhou, J.L.; Chen, H.; Liu, R.; Magnuson, J.T.; Zheng, C. Translocation, Bioaccumulation, and Distribution of Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) in Plants. iScience 2022, 25, 104061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasters, R.; Groffen, T.; Eens, M.; Bervoets, L. Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in Homegrown Crops: Accumulation and Human Risk Assessment. Chemosphere 2024, 364, 143208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLuca, N.M.; Minucci, J.M.; Mullikin, A.; Slover, R.; Cohen Hubal, E.A. Human Exposure Pathways to Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) from Indoor Media: A Systematic Review. Environ. Int. 2022, 162, 107149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wee, S.Y.; Aris, A.Z. Environmental Impacts, Exposure Pathways, and Health Effects of PFOA and PFOS. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 267, 115663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUPAC Terminology and Classification of Per- and Poly-Fluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS). Available online: https://iupac.org/project/2024-006-3-100 (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Stecconi, T.; Tavoloni, T.; Stramenga, A.; Bacchiocchi, S.; Barola, C.; Dubbini, A.; Galarini, R.; Moretti, S.; Sagratini, G.; Piersanti, A. A LC-MS/MS Procedure for the Analysis of 19 Perfluoroalkyl Substances in Food Fulfilling Recent EU Regulations Requests. Talanta 2024, 266, 125054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dube, A.; Malode, S.J.; Akhdar, H.; Alodhayb, A.N.; Shetti, N.P. Electrochemical Detection of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances: A Review. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2025, 252, 114653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, K.L.; Hwang, J.-H.; Esfahani, A.R.; Sadmani, A.H.M.A.; Lee, W.H. Recent Developments of PFAS-Detecting Sensors and Future Direction: A Review. Micromachines 2020, 11, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gondhiya, N.; Rehman, A.U.; Andreescu, D.; Andreescu, S. Portable Electrochemical Sensors for Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances: Design, Challenges, and Opportunities for Field Deployment. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2025, 53, 101725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenobio, J.E.; Salawu, O.A.; Han, Z.; Adeleye, A.S. Adsorption of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) to Containers. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2022, 7, 100130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannone, A.; Carriera, F.; Di Fiore, C.; Avino, P. Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substance (PFAS) Analysis in Environmental Matrices: An Overview of the Extraction and Chromatographic Detection Methods. Analytica 2024, 5, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, T.E.; Talebi, M.; Minett, A.; Mills, S.; Doble, P.A.; Bishop, D.P. Micro Solid-Phase Extraction for the Analysis of per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in Environmental Waters. J. Chromatogr. A 2019, 1604, 460495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, T.; Sarkar, D.; Andreescu, S.; Du, H. Advances in Nanosensor Technologies for PFAS Detection: A Review. IEEE Sens. Rev. 2025, 2, 498–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, D.; Zolfigol, N.; Xia, Z.; Lei, Y. Recent Progress in Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) Sensing: A Critical Mini-Review. Sens. Actuators Rep. 2024, 7, 100189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menger, R.F.; Funk, E.; Henry, C.S.; Borch, T. Sensors for Detecting Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS): A Critical Review of Development Challenges, Current Sensors, and Commercialization Obstacles. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 417, 129133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Hosamo, H.; Ying, C.; Nie, R. A Comprehensive Review and Analysis of Nanosensors for Structural Health Monitoring in Bridge Maintenance: Innovations, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 11149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiruvengadam, M.; Chi, H.-Y.; Choi, H.-J.; Jung, B.-S.; Lee, S.-B.; Park, Y.; Jeon, D.; Ciftci, F.; Shariati, M.A.; Kim, S.-H. Sustainable and Smart Nano-Biosensors: Integrated Solutions for Healthcare, Environmental Monitoring, Agriculture, and Food Safety. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 233, 121337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exbrayat, L.; Salaluk, S.; Uebel, M.; Jenjob, R.; Rameau, B.; Koynov, K.; Landfester, K.; Rohwerder, M.; Crespy, D. Nanosensors for Monitoring Early Stages of Metallic Corrosion. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2019, 2, 812–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzat, A.K.; Asmatulu, R. Nanotechnology Safety in Sensors and Security Industries. In Nanotechnology Safety; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; pp. 251–281. [Google Scholar]

- Darwish, M.A.; Abd-Elaziem, W.; Elsheikh, A.; Zayed, A.A. Advancements in Nanomaterials for Nanosensors: A Comprehensive Review. Nanoscale Adv. 2024, 6, 4015–4046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brase, R.A.; Mullin, E.J.; Spink, D.C. Legacy and Emerging Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances: Analytical Techniques, Environmental Fate, and Health Effects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US EPA. Final PFAS National Primary Drinking Water Regulation. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/sdwa/and-polyfluoroalkyl-substances-pfas (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- US EPA. Developing and Demonstrating Nanosensor Technology to Detect, Monitor, and Degrade Pollutants Request for Applications (RFA). Available online: https://www.epa.gov/research-grants/developing-and-demonstrating-nanosensor-technology-detect-monitor-and-degrade-1 (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Radjenovic, J.; Duinslaeger, N.; Avval, S.S.; Chaplin, B.P. Facing the Challenge of Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances in Water: Is Electrochemical Oxidation the Answer? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 14815–14829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codina, A.S.; Lumbaque, E.C.; Radjenovic, J. Electrochemical Removal of Contaminants of Emerging Concern with Manganese Oxide-Functionalized Graphene Sponge Electrode. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 508, 160940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumbaque, E.C.; Radjenovic, J. Electro-Oxidation of Persistent Organic Contaminants at Graphene Sponge Electrodes Using Intermittent Current. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 476, 146910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jevremović, A.; Ranković, M.; Janošević Ležajić, A.; Uskoković-Marković, S.; Nedić Vasiljević, B.; Gavrilov, N.; Bajuk-Bogdanović, D.; Milojević-Rakić, M. Regeneration or Repurposing of Spent Pollutant Adsorbents in Energy-Related Applications: A Sustainable Choice? Sustain. Chem. 2025, 6, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manayil Parambil, A.; Priyadarshini, E.; Paul, S.; Bakandritsos, A.; Sharma, V.K.; Zbořil, R. Emerging Nanomaterials for the Detection of Per- and Poly-Fluorinated Substances. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. 2025, 13, 8246–8281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Dharmarajan, R.; Megharaj, M.; Naidu, R. Gold Nanoparticle-Based Optical Sensors for Selected Anionic Contaminants. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2017, 86, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouyban, A.; Rahimpour, E. Optical Sensors Based on Silver Nanoparticles for Determination of Pharmaceuticals: An Overview of Advances in the Last Decade. Talanta 2020, 217, 121071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Jiang, C.Z.; Roy, V.A.L. Designed Synthesis and Surface Engineering Strategies of Magnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles for Biomedical Applications. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 19421–19474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshta, B.E.; Gemeay, A.H.; Kumar Sinha, D.; Elsharkawy, S.; Hassan, F.; Rai, N.; Arora, C. State of the Art on the Magnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Functionalization, and Applications in Wastewater Treatment. Results Chem. 2024, 7, 101388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, K.H.; Saifuddin, M.; Chon, K.; Bae, S.; Kim, Y.M. Recent Advances in the Application of Magnetic Materials for the Management of Perfluoroalkyl Substances in Aqueous Phases. Chemosphere 2024, 352, 141522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Song, X.; Liu, M.; Chen, M.; Li, J.; Han, J. Review on the Use of Magnetic Nanoparticles in the Detection of Environmental Pollutants. Water 2023, 15, 3077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendão, R.M.S.; Esteves da Silva, J.C.G.; Pinto da Silva, L. Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) Detection Via Carbon Dots: A Review. Sustain. Chem. 2023, 4, 339–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walekar, L.S.; Zheng, M.; Zheng, L.; Long, M. Selenium and Nitrogen Co-Doped Carbon Quantum Dots as a Fluorescent Probe for Perfluorooctanoic Acid. Microchim. Acta 2019, 186, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crista, D.M.A.; Esteves da Silva, J.C.G.; Pinto da Silva, L. Evaluation of Different Bottom-up Routes for the Fabrication of Carbon Dots. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, O.S.; Bedwell, T.S.; Esen, C.; Garcia-Cruz, A.; Piletsky, S.A. Molecularly Imprinted Polymers in Electrochemical and Optical Sensors. Trends Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 294–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBarron, C.T.; Pavithra; Hosseini, S. Recent Insights into Electrochemical Sensing of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances. ECS Sens. Plus 2025, 4, 033601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, M.L.; Patel, R.; Chaudhary, K.J.; Gupta, R.K. Metal–Organic Frameworks for PFAS Remediation and Sensing: From Molecular Design to Real-World Implementation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2025, 64, 13536–13556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.H.; Barpaga, D.; Soltis, J.A.; Shutthanandan, V.; Kargupta, R.; Han, K.S.; McGrail, B.P.; Motkuri, R.K.; Basuray, S.; Chatterjee, S. Metal–Organic Framework-Based Microfluidic Impedance Sensor Platform for Ultrasensitive Detection of Perfluorooctanesulfonate. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 10503–10514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ihsanullah, I. Targeted PFAS Removal Using MXene-Based Polymeric Membranes: Toward Cleaner Water Solutions. Chem. Asian J. 2025, 20, e00822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; He, Y.; He, S.; Deng, L.; Wang, H.; Cao, Z.; Feng, Z.; Xiong, B.; Yin, Y. A Brief Review of Aptamer-Based Biosensors in Recent Years. Biosensors 2025, 15, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi Tabar, F.; Lowdon, J.W.; Bakhshi Sichani, S.; Khorshid, M.; Cleij, T.J.; Diliën, H.; Eersels, K.; Wagner, P.; van Grinsven, B. An Overview on Recent Advances in Biomimetic Sensors for the Detection of Perfluoroalkyl Substances. Sensors 2023, 24, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimian, N.; Stortini, A.M.; Moretto, L.M.; Costantino, C.; Bogialli, S.; Ugo, P. Electrochemosensor for Trace Analysis of Perfluorooctanesulfonate in Water Based on a Molecularly Imprinted Poly(o-Phenylenediamine) Polymer. ACS Sens. 2018, 3, 1291–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Zhu, D.Z.; Gan, H.; Yao, Z.; Luo, J.; Yu, S.; Kurup, P. An Ultra-Sensitive Molecularly Imprinted Polymer (MIP) and Gold Nanostars (AuNS) Modified Voltammetric Sensor for Facile Detection of Perfluorooctance Sulfonate (PFOS) in Drinking Water. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2022, 352, 131055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Tang, J.; Chen, Y.; Bai, X.; Liao, Y.; Ouyang, X.; Wang, Y.; Tang, L. A Stable Dual-Functional Monomer Imprinted Polymer Platform for Electrochemical Sensitive Detection of PFAS. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 493, 138422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malloy, C.S.; Danley, M.J.; Bellido-Aguilar, D.A.; Partida, L.; Castrejón-Miranda, R.; Savagatrup, S. Effects of Fabrication Parameters on the Mechanical and Sensing Properties of Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) for the Detection of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS). ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2024, 6, 9914–9921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khitous, A.; Arcadio, F.; Zeni, L.; Cennamo, N.; Soppera, O. In Situ Synthesis of Molecularly Imprinted Polymers by Near-Field Photopolymerization for Ultrasensitive PFOA Plasmonic Plastic Fiber Optic Sensors. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2025, 442, 137992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, N.; Chen, J.; He, Q.; Schwartz, J.S.; Wu, J.J. Ultra-Sensitive and Rapid Detection of Perfluorooctanesulfonic Acid by a Capacitive Molecularly-Imprinted-Polymer Sensor Integrated with AC Electrokinetic Acceleration. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2024, 420, 136464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, W.; Chen, X.; Cai, Z. Hydrophobic SERS Substrate for PFOA Sensing and Cooperative Adsorption. Talanta 2025, 294, 128244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.; Uygun, Z.O.; Andreescu, D.; Andreescu, S. Sensitive Detection of Perfluoroalkyl Substances Using MXene–AgNP-Based Electrochemical Sensors. ACS Sens. 2024, 9, 3403–3412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothstein, J.C.; Cui, J.; Yang, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhao, Y. Ultra-Sensitive Detection of PFASs Using Surface Enhanced Raman Scattering and Machine Learning: A Promising Approach for Environmental Analysis. Sens. Diagn. 2024, 3, 1272–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvillo Solís, J.J.; Yin, S.; Galicia, M.; Ersan, M.S.; Westerhoff, P.; Villagrán, D. “Forever Chemicals” Detection: A Selective Nano-Enabled Electrochemical Sensing Approach for Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA). Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 491, 151821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Park, J.; Choe, J.K.; Choi, Y. Perfluoroalkyl Functionalized-Au Nanoparticle Sensor: Employing Rate of Spectrum Shifting for Highly Selective and Sensitive Detection of per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) in Aqueous Environments. Water Res. X 2024, 24, 100239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, W.; Zhao, H.; Qian, B.; Lan, M. A Molecularly Imprinted Electrochemical Sensor Based on Nitrogen-Doped Graphene Oxide Nanoribbons and Au-Pt Bimetallic Nanoparticles for Ultrasensitive Detection of Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) in Aqueous Medium. Microchem. J. 2025, 215, 114256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, F.; Munoz, G.; Mirzaei, M.; Barbeau, B.; Liu, J.; Duy, S.V.; Sauvé, S.; Kandasubramanian, B.; Mohseni, M. Removal of Zwitterionic PFAS by MXenes: Comparisons with Anionic, Nonionic, and PFAS-Specific Resins. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 6212–6222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashtbari, S.; Dehghan, G.; Khataee, A.; Khataee, S.; Orooji, Y. A Sensitive and Selective Amperometric Determination of Perfluorooctanesulfonic Acid on Mo2Ti2AlC3 MXene Precursor-Modified Electrode. Chemosphere 2025, 370, 144012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.; Xiao, J.; Bu, L.; Ao, J.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, S. F⋯F Interaction-Boosted Molecular Imprinting on MOF/MXene Heterostructure: Field-Deployable Sensor for Ultrashort-Chain PFAS at Trace Levels. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2026, 448, 139031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, T.; Kong, F.; Guo, J.; Wang, S.; Li, J.; Song, Y.-Y.; Gao, Z.; Zhao, C. Signal Amplification via MOF-Nanozyme Microenvironment Modulation in Nanochannels for PFOA Detection. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 521, 166891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, R.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Li, W.; Qiu, J. On a Nanocontainer Having a Magnetic Core and a Porous Shell Loaded with Erythrosin B for the Optical Sensing and Adsorption of Perfluorooctane Sulfonate. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2025, 469, 116604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Li, J.; Wu, F. The Characterization and Performance of a Core–Shell Structured Nanoplatform for Fluorescence Turn-on Sensing and Selective Removal of Perfluorooctane Substance. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2025, 340, 126356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Ortiz, J.; He, S.; Li, X.; Kaur, B.; Cao, B.; Seiden, Z.; Wu, S.; Wei, H. Magnetically Retrievable Nanoparticles with Tailored Surface Ligands for Investigating the Interaction and Removal of Water-Soluble PFASs in Natural Water Matrices. Sensors 2025, 25, 4353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Hussain, S.; Tang, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Gao, R.; Wang, S.; Hao, Y. Two-in-One Platform Based on Conjugated Polymer for Ultrasensitive Ratiometric Detection and Efficient Removal of Perfluoroalkyl Substances from Environmental Water. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 860, 160467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierpaoli, M.; Szopińska, M.; Olejnik, A.; Ryl, J.; Fudala-Ksiażek, S.; Łuczkiewicz, A.; Bogdanowicz, R. Engineering Boron and Nitrogen Codoped Carbon Nanoarchitectures to Tailor Molecularly Imprinted Polymers for PFOS Determination. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 458, 131873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]