Abstract

Molecularly Imprinted Polymer (MIP)-based sensors have gained increasing attention in the field of food safety analysis due to their unique ability to selectively recognize and quantify chemical contaminants and allergens with interesting sensitivity. These synthetic receptors, often referred to as “plastic antibodies,” offer several advantages over conventional analytical methods, including high stability, cost-effectiveness, reusability, and compatibility with miniaturized sensor platforms. This review provides a comprehensive overview of recent advances in the design, fabrication, and application of MIP-based sensors for the detection of a broad range of food contaminants, including pesticides, antibiotics, mycotoxins, heavy metals, acrylamide, heterocyclic amines, allergens, viruses, and bacteria. Various transduction mechanisms—electrochemical, optical, thermal, and mass-sensitive—are discussed in relation to their integration with MIP recognition elements. The review also highlights the advantages and limitations of MIPs in comparison with traditional techniques such as ELISA and HPLC. Finally, we explore current challenges and emerging trends, including nanomaterial integration, multiplexed detection, and smartphone-based platforms, which are expected to drive future developments toward real-time, point-of-need, and regulatory-compliant food safety monitoring tools.

1. Introduction

Food safety is a global concern of critical importance, affecting public health, international trade, and consumer confidence. With the increasing globalization of the food supply chain, the risk of contamination by chemical residues [1], environmental pollutants [2], and biological hazards [3] has risen significantly. Contaminants such as pesticides, veterinary antibiotics, mycotoxins, heavy metals, and processing-induced chemicals like acrylamide are commonly found in various food products, often at trace levels that can still pose significant health risks over prolonged exposure [4]. In parallel, food allergens, particularly proteins from milk, eggs, peanuts, soy, wheat (gluten), and tree nuts, can trigger severe immunological responses in sensitive individuals, ranging from mild symptoms to life-threatening anaphylaxis [5]. The problem of foodborne illness and allergen-related incidents has placed pressure on food producers and regulatory bodies to implement strict safety monitoring practices.

To protect public health, regulatory agencies such as the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the Codex Alimentarius Commission have established maximum residue limits (MRLs) and labeling requirements for a broad range of food contaminants and allergens. Compliance with these regulations requires the deployment of accurate, sensitive, and high-throughput analytical methods capable of detecting low levels of target analytes in complex food matrices [6]. Traditionally, chromatographic techniques, such as high-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS) [7], gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) [8], and capillary electrophoresis [9], are used for the quantification of chemical residues. Likewise, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) are widely used for protein and DNA-based detection. Despite their analytical performance, these conventional methods are time-consuming, expensive, and often require centralized laboratory facilities and trained personnel [10,11].

In response to the need for faster, more accessible alternatives, researchers have turned to sensor-based technologies, particularly MIP-based sensors, which offer a promising route toward miniaturized, cost-effective, and field-deployable detection platforms [12]. MIPs are synthetic recognition elements formed by polymerizing functional monomers in the presence of a target molecule (template), which is later removed to leave behind selective binding cavities. These “plastic antibodies” exhibit high affinity and specificity for their target, along with superior thermal and chemical stability [13], long shelf life, and compatibility with a wide range of transduction systems [14]. Their performance in harsh conditions and ability to operate without refrigeration or biological reagents make them especially attractive for food quality control in both industrial and low-resource settings [15].

Recent years have seen significant progress in the design and application of MIP-based sensors for food analysis. Innovations in nano-MIP synthesis [16], electropolymerization techniques [17], and integration with nanomaterials such as carbon nanotubes [18], graphene [19], and metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) [20] have greatly enhanced their sensitivity, selectivity, and response time. These sensors have been successfully applied to detect a wide array of food hazards from small molecules like pesticides and antibiotics to large biomolecules such as allergens, viruses, and bacterial pathogens. Furthermore, MIPs have been increasingly incorporated into smart sensing platforms linked to mobile devices and cloud systems, paving the way for real-time, decentralized monitoring solutions [21,22].

This review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of recent developments in MIP-based sensor technologies for food contaminants and allergen detection. It begins with the fundamental principles of MIP synthesis and sensor design, followed by an in-depth examination of the different transduction mechanisms and their analytical performance. The review then explores various application areas, including pesticides, antibiotics, mycotoxins, heavy metals, processing-induced toxins, food allergens, viruses, and bacteria, highlighting both advantages and current limitations. Finally, we discuss the comparison between MIP sensors and conventional analytical methods, and present emerging trends and future perspectives that are shaping the next generation of MIP-based food monitoring systems.

Although numerous reviews on MIP sensors have been published in recent years, they remain highly segmented in scope. Most existing reviews focus either on a single transduction method, such as electrochemical, optical, thermal, or mass-sensitive platforms, or on specific application fields, including environmental monitoring, biomedical diagnostics, or pharmaceutical analysis. However, no recent review provides a comprehensive overview of MIP-based sensors specifically dedicated to the detection of food contaminants, despite the wide molecular diversity and strict regulatory limits associated with chemical and microbiological hazards in foods.

2. Principles of Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs)

MIPs are synthetic polymeric materials designed to possess highly selective recognition sites for a target molecule, often referred to as the “template.” These sites are created through a molecular imprinting process in which functional monomers most often form reversible interactions with the template before polymerization. Once the polymerization is complete and the template is removed, the resulting material retains three-dimensional cavities that are complementary in shape, size, and chemical functionality to the original target molecule. This mechanism allows MIPs to function as “plastic antibodies” capable of selectively rebinding the target analyte even in complex matrices.

2.1. Preparation Strategies

The synthesis of MIPs can be performed through several distinct approaches, each offering specific advantages depending on the nature of the analyte and the intended application.

2.1.1. Bulk Imprinting

One of the earliest and simplest imprinting methods, where polymerization occurs in a single phase, followed by grinding and sieving of the bulk polymer. While cost-effective and straightforward, it often produces irregular particles and can limit accessibility to recognition sites due to their location within the polymer matrix [23].

2.1.2. Surface Imprinting

In this method, the template is anchored onto a substrate surface, and a thin imprinted polymer layer is formed around it. This results in improved accessibility to binding sites and faster kinetics, making surface-imprinted MIPs suitable for large biomolecules like proteins [24], allergens [25], and even viruses [26].

2.1.3. NanoMIPs/Solid-Phase Synthesis

A highly advanced strategy where the template is immobilized on a solid support, and only high-affinity nanoparticles are retained after washing. This method yields uniform nanostructured MIPs, often referred to as nanoMIPs, with superior binding affinity, reproducibility, and scalability for commercial sensor development [27].

2.1.4. Electropolymerization

Widely used in the development of MIP-based electrochemical sensors, this technique allows the precise deposition of the polymer directly onto conductive substrates (e.g., glassy carbon, gold, indium tin oxide (ITO)). It enables fine control over film thickness, morphology, and binding site orientation [17].

2.1.5. Sol–Gel Polymerization

A hybrid organic-inorganic technique where silane monomers are hydrolyzed and condensed under mild conditions to form silica-based matrices. This approach is especially useful for optical sensors and allows the integration of MIPs onto glass, quartz, and metal oxide surfaces [28].

The advantages and disadvantages of each imprinting method are gathered in Table 1.

Table 1.

Advantages and disadvantages of the main molecular imprinting methods.

Importantly, each imprinting strategy shows differential suitability depending on the physicochemical nature of the target analyte. Bulk or sol–gel imprinting is most appropriate for small, rigid molecules such as pesticides, acrylamide, heterocyclic amines, or mycotoxins, for which the creation of well-defined molecular cavities is straightforward. In contrast, surface imprinting and electropolymerization offer clear advantages for macromolecular targets (allergens, enzymes, bacteria, viruses), since steric accessibility, fast mass transfer, and orientation of binding sites are critical to achieve efficient rebinding. Solid-phase synthesis and nanoMIPs provide superior affinity and reproducibility for fragile analytes (allergens, viral epitopes) thanks to controlled templating under mild conditions. These distinctions justify why specific imprinting methods tend to be consistently selected for particular contaminant families in food analysis.

2.2. Functional Monomers and Cross-Linkers

The functionality and performance of MIPs are heavily influenced by the choice of monomers and cross-linking agents. These components determine the strength and specificity of interactions with the target molecule, as well as the physical properties of the resulting polymer.

2.2.1. Functional Monomers

- Methacrylic acid (MAA): The most used monomer in non-covalent imprinting, thanks to its ability to form hydrogen bonds and ionic interactions with a wide range of analytes.

- Acrylamide and its derivatives: Suitable for imprinting in aqueous environments due to their hydrophilic nature and good solubility in water.

- Pyrrole and Aniline: Often used in electropolymerization for their conductivity and ease of oxidative polymerization. They allow direct integration into electrochemical sensors.

- Dopamine: Forms robust polydopamine films through self-polymerization under alkaline conditions. Frequently used in biocompatible and surface-imprinted systems, especially for proteins and allergens.

- 3-Aminopropyltrimethoxysilane (APTMS): A silane-based monomer frequently employed in sol–gel imprinting. It offers covalent anchoring to inorganic substrates such as silica or gold nanoparticles and contributes to the formation of highly stable, functionalized surfaces.

2.2.2. Cross-Linkers

- Ethylene glycol dimethacrylate (EGDMA) and Divinylbenzene (DVB): Commonly used in free-radical polymerization, these cross-linkers provide structural integrity and rigidity to the MIP, preserving the shape and functionality of the recognition sites.

- Tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS): A key cross-linker in sol–gel chemistry, TEOS undergoes hydrolysis and condensation reactions to form a siloxane (Si–O–Si) network. When combined with functional monomers such as APTMS, TEOS contributes to the formation of a porous and chemically robust hybrid polymer matrix. This is particularly advantageous for applications involving high temperature, humidity, or exposure to solvents.

2.3. Key Properties of MIPs

MIPs exhibit a set of desirable physicochemical and functional properties that make them highly attractive for use in sensor development: (i) High selectivity: Thanks to template-shaped cavities that are chemically and spatially complementary to the target analyte [29]; (ii) Chemical and thermal stability: MIPs can maintain performance under harsh environmental conditions, unlike biological recognition elements such as antibodies or enzymes [13]; (iii) Reusability: The robustness of the polymer matrix allows multiple binding and regeneration cycles without significant loss of performance [30]; (iv) Compatibility with diverse transducers: MIPs can be interfaced with various signal transduction platforms, including electrochemical [31], optical [32], gravimetric [33], and thermal systems [34]; (v) Adaptability to various formats: MIPs can be fabricated as films [35], particles [36], fibers [37], or nanocomposites [38], enabling their use in microfluidics [39], paper-based devices [40], wearable sensors [41], and smartphone-integrated systems [21].

The rational design of MIPs through appropriate selection of monomers, cross-linkers, imprinting strategy, and polymerization technique allows for the development of highly tailored synthetic receptors. These receptors are particularly well-suited for the selective, sensitive, and cost-effective detection of food contaminants and allergens, even in complex and dynamic environments.

2.4. Role of Porosity and Porogens in MIP Performance

The porosity of the polymer matrix, defined by pore volume, pore-size distribution, and cross-linking density, critically governs the accessibility and diffusion of target analytes into the imprinted cavities. Porogens play a fundamental role during polymerization: their polarity, solubility, and evaporation behavior determine the micro- and mesoporous structure of the final material. Low-polarity porogens (e.g., toluene, chloroform) generally favor large, open pores suitable for hydrophobic or bulky contaminants, whereas polar porogen mixtures (e.g., ACN/methanol) enable the formation of more compact and hydrogen bond-stabilized MIP networks for polar molecules such as antibiotics or mycotoxins. Tailoring porosity is particularly crucial in food analysis, where complex matrices require fast mass transfer, non-fouling surfaces, and readily accessible binding sites. The reviewed studies consistently show that sensors with optimized porogen selection achieve higher sensitivity, improved selectivity, and faster binding kinetics.

3. Transduction Mechanisms in MIP-Based Sensors

The successful application of MIPs in sensor technology depends not only on the selectivity of the imprinted cavities but also on the effectiveness of the signal transduction mechanism. Upon rebinding of the target analyte to the MIP recognition site, a physicochemical change is induced that must be converted into a measurable output by the sensor. Several transduction strategies have been developed, each offering unique advantages depending on the nature of the analyte, matrix complexity, and required sensitivity.

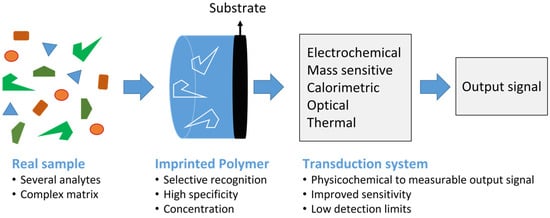

The general principle of MIPs-based sensors for selective extraction, preconcentration, and detection of target analytes is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

General principle of MIPs-based sensors for selective extraction, preconcentration, and detection of target analytes. MIPs selectively capture an analyte through template-specific cavities, enabling efficient removal of matrix interferents and analyte preconcentration. The captured analyte can then be detected using different transduction techniques to improve sensitivity and to lower detection limits across food analysis applications.

3.1. Electrochemical Transduction

Electrochemical MIP sensors are among the most widely used platforms for food contaminants and allergen detection due to their high sensitivity, ease of miniaturization, and low-cost instrumentation [42].

The binding of the target analyte to the MIP layer affects the electron transfer characteristics at the electrode surface. This can result in changes in current for amperometric or voltammetric sensors, in potential for potentiometric sensors, in impedance for impedimetric sensors, or in capacitance for capacitive sensors.

The advantages of electrochemical transduction are excellent sensitivity, often in the picomolar range, a low sample volume requirement, and flexibility of integration with portable and disposable formats (e.g., screen-printed electrodes) [43].

Electrochemical sensors may suffer from electrode fouling, signal drift, or reduced sensitivity when targeting non-electroactive analytes.

Integration with nanomaterials like carbon nanotubes (CNTs) [44], graphene oxide (GO) [45], or gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) [46] significantly enhances electron transfer and increases surface area, thereby improving both sensitivity and stability.

3.2. Optical Transduction

Optical MIP sensors rely on measurable changes in light properties upon target binding, making them ideal for label-free detection and real-time monitoring. The mechanisms include Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR), where the binding of the analyte alters the refractive index at a metal-MIP interface [47], fluorescence, where fluorophore-labeled MIPs change emission intensity or wavelength upon analyte interaction [48], and colorimetry, where visual color changes (often using nanoparticles or photonic structures) provide qualitative or semi-quantitative results [49].

The advantages of optical transduction are label-free and real-time detection (especially for SPR), high specificity and compatibility with transparent substrates, and the potential for multiplexed analysis using different fluorophores or photonic patterns.

Optical methods such as SPR or fluorescence can be affected by turbidity, refractive-index fluctuations, or quenching effects from pigments naturally present in foods.

Portable implementations of optical MIP sensors, such as smartphone-assisted colorimetric test strips, are gaining prominence for rapid, on-site screening of food contaminants [21,50].

Fluorescence-based MIP sensors can also benefit from strong signal amplification through the integration of quantum dots, whose high quantum yield and tunable emission significantly enhance sensitivity and enable ultra-trace detection of food contaminants [51,52].

3.3. Mass-Sensitive Transduction

Mass-sensitive sensors measure changes in mass at the surface of the MIP layer, typically using Quartz Crystal Microbalance (QCM) [53] or Surface Acoustic Wave (SAW) devices [54]. The binding of target molecules increases the mass on the sensor surface, resulting in a shift in resonant frequency of a quartz crystal or acoustic wave propagating through the material.

The advantages of mass-sensitive transduction are label-free detection with real-time response, high selectivity and sensitivity, and its use for large biomolecules such as allergens [55] or whole bacteria [56].

In terms of limitations, these sensors are more sensitive to environmental fluctuations (e.g., temperature, humidity) and often require controlled conditions for accurate measurement [57,58].

3.4. Thermal and Calorimetric Transduction

Thermal transduction, particularly Heat Transfer Method (HTM), is a newer approach where the thermal resistance at the solid–liquid interface changes upon analyte binding. When an analyte binds to the MIP layer, it alters the heat flow from the sensor to the surrounding medium. This change can be correlated to the analyte concentration [27].

In terms of advantages, thermal heat transduction does not require optical or electrical labels, is highly suitable for low-resource settings, and can be implemented on flexible substrates for wearable or portable applications.

Thermal transduction methods generally display lower sensitivity and demand controlled thermal conditions for reliable measurements.

In terms of future developments, calorimetric MIP sensors may also be integrated with microfluidics to enable ultra-compact devices for on-site screening.

3.5. Hybrid and Multi-Mode Transduction Systems

To enhance performance, multi-transduction MIP sensors are being developed, combining two or more signal outputs (e.g., electrochemical + optical, electrochemical + thermal, thermal + optical) [59,60,61]. These systems allow cross-validation of results (increased reliability), enhanced sensitivity through signal amplification, and adaptation to diverse detection environments.

The following table (Table 2) summarizes the MIP transduction types, the signal types, the common targets, and the key advantages.

Table 2.

MIP transduction types, signal types, sensitivity range, common targets, and key advantages.

Table 2.

MIP transduction types, signal types, sensitivity range, common targets, and key advantages.

| Transduction Type | Signal Type | Sensitivity | Common Targets | Key Advantages | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrochemical | Current, Voltage, Impedance | pM–nM | Pesticides, antibiotics, heavy metals, allergens | Fast, portable, low-cost | [62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69] |

| Optical | Refractive index, Fluorescence, Colorimetry, Surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) | fM–nM | Mycotoxins, allergens | Label-free, real-time, suitable for multiplexing | [70,71,72] |

| Mass-sensitive | Frequency shift (QCM, SAW) | fM–pM | Viruses, bacteria | Direct mass detection, high selectivity | [73] |

| Thermal/HTM | Heat flow/resistance | nM–µM | Antibiotics, hormones | Simple setup, no labeling or complex equipment | [61,74] |

| Hybrid Systems | Multi-signal (e.g., electrochemical + optical) | fM–pM | Multi-contaminant panels | Redundant signals, improved accuracy, and robustness | [71] |

The choice of transduction mechanism is also strongly dictated by the physicochemical behavior of each contaminant class. Electrochemical sensors are particularly suited for redox-active or charge-modifying analytes, such as heavy metals, antibiotics, allergens, or pesticides, which induce measurable current, potential, or impedance changes at the MIP-modified interface. Optical platforms (SPR, fluorescence, colorimetry) are advantageous for mycotoxins whose binding significantly alters refractive index or optical absorption/emission. Mass-sensitive systems (QCM, SAW) are intrinsically compatible with high-molecular-weight targets, including viruses and bacteria, where mass loading directly translates into high signal-to-noise ratios. Thermal methods excel for small molecules that induce strong modifications in the interfacial heat-transfer coefficient. These mechanistic considerations explain why different contaminant families consistently align with specific transduction strategies in the reviewed literature.

4. Applications of MIP Sensors in Food Contaminant Detection

This section explores recent innovations in MIP-based sensor technology, focusing on the strategies used for their design, fabrication, and implementation in food safety analysis. It covers a broad range of contaminants, including pesticides, antibiotics, mycotoxins, heavy metals, acrylamide, heterocyclic amines, allergens, viruses, and bacteria.

A summary table has been constructed for each analyte, compiling up to ten recent and representative studies, with a primary focus on work published between 2020 and 2025. In contaminant classes where fewer recent reports were available, a small number of earlier but influential studies (2015–2019) were included to ensure sufficient coverage. Each table details key parameters, including the transduction technique, MIP deposition strategy, detection limit, functional monomer employed, and the real-world sample matrix tested.

The purpose of the following subsections is not to provide a generic overview of MIP fabrication or transduction, but to show how these technological choices are driven by the analytical requirements specific to food contaminants (e.g., complex matrices, low regulatory limits, structural diversity of analytes, need for portable or on-site detection).

4.1. Pesticides

Pesticides are small, rigid, and often electroactive molecules, which explains the predominance of bulk or suspension imprinting and electropolymerization, combined with electrochemical transduction. Their low molecular weight and well-defined structure favor the formation of high-fidelity cavities, while their redox or charge-transfer behavior makes them ideal candidates for voltammetric or impedimetric detection.

The reviewed studies (Table 3) collectively demonstrate major progress in the development of MIP-based sensors for the detection of pesticide residues in food and environmental samples. These sensors exhibit high selectivity and sensitivity, with detection limits reaching as low as picogram or nanomolar levels for various pesticides such as diazinon (LOD = 7.9 × 10−10 M) [62], methyl parathion (4.64 × 10−12 M) [63], malathion (1.82 × 10−13 M) [64], metribuzin (4.67 × 10−13 M) [65], and deltamethrin (1.53 × 10−9 M) [75]. The studies applied diverse transduction techniques, including electrochemical voltammetry, electrochromic signaling, and luminescence or fluorescence-based optical sensing. MIP fabrication strategies ranged from bulk and suspension polymerization to magnetic core–shell synthesis and surface imprinting via electropolymerization. These methods were successful in detecting a broad range of pesticides, including organophosphates, pyrethroids, and triazinones, in complex food matrices like olive oil, honey, fish, apples, and tomatoes. The integration of MIPs with nanomaterials and innovative platforms such as micro-needle sensors and paper-based devices further enhanced sensor performance, stability, and portability. Moreover, review articles by Parihar et al. (2024) [76] and Kumar et al. (2022) [77] underscore the transformative potential of IoT-enabled and luminescent MIP sensors, respectively, for on-site and real-time monitoring of pesticide residues in food and environmental contexts. These findings highlight the versatility and promise of MIP-based technologies in advancing food safety and environmental health.

Table 3.

Recent examples of MIP-based sensors for the detection of pesticides in food matrices and in water.

Overall, the MIP-based sensors reported in Table 3 exhibit excellent analytical performance for pesticide detection, with LOD values often in the ng·L−1 to µg·L−1 range, depending on the transduction method used. Electrochemical platforms generally provide the lowest LODs due to their high intrinsic sensitivity, followed by optical and mass-sensitive approaches. Repeatability was reported for most studies, typically with RSD values below 5–10%, and several sensors demonstrated good reusability over multiple regeneration cycles. Importantly, the majority of LODs listed in Table 3 are well below the default maximum residue level (MRL) of 0.01 mg·kg−1 established in the EU when no specific pesticide-commodity MRL is available. This indicates that most of the proposed MIP-based sensors possess sufficient sensitivity to detect pesticide residues at concentrations relevant for regulatory monitoring in food products.

4.2. Antibiotics

Antibiotics possess ionisable groups and often display electroactive or fluorescent properties. Accordingly, MIPs targeting antibiotics commonly rely on electropolymerization or sol–gel films integrated into electrochemical, fluorescence, or thermal sensors. Their charge-transfer ability and polar functional groups enhance measurable changes in current, impedance, or fluorescence quenching.

The reviewed articles (Table 4) highlight significant advances in the development of MIP-based sensors for the detection of various antibiotic residues in food matrices. These studies demonstrate that MIPs offer a highly selective and sensitive approach for monitoring antibiotic contamination, thereby addressing concerns related to food safety and antimicrobial resistance. The target antibiotics include fluoroquinolones like ciprofloxacin, moxifloxacin, and ofloxacin [81], sulfonamides such as sulfadiazine [51] and sulfamethoxazole [74], aminoglycosides like tobramycin [82], lincosamides such as lincomycin [83], and fluoroquinolone norfloxacin [84]. These MIP-based platforms employed a diverse range of transduction techniques, including electrochemical (DPV, EIS) [83], fluorescence using carbon dots or quantum dots [51], thermal sensing via heat transfer [74], SPR [81], and SERS. The fabrication methods ranged from electropolymerization on modified electrodes to nanoparticle-assisted surface imprinting, with reported limits of detection reaching as low as the picomolar or even sub-picomolar range, such as 2.5 × 10−11 M for norfloxacin [84] and 2.61 × 10−10 M for sulfamethoxazole [74]. Real sample analysis was successfully performed on milk, fruit juices, tap water, and other food matrices, confirming the practical applicability of these MIP sensors. Overall, these findings underscore the potential of MIP-based biosensors as reliable, cost-effective, and eco-friendly alternatives to conventional chromatographic or immunological methods for routine antibiotic residue monitoring.

Table 4.

Recent examples of MIP-based sensors for the detection of antibiotics in food matrices and in water.

4.3. Acrylamide and Heterocyclic Amine

Acrylamide (AM) and Heterocyclic Amines (HAAs) are small polar molecules requiring sensitive, low-noise detection, which explains the use of sol–gel MIPs, electropolymerized films, and photoelectrochemical or QCM platforms. Their small size enables accurate templating, while their interaction with the MIP layer induces detectable electrochemical, optical, or mass-sensitive responses.

Across the reviewed articles (Table 5), MIPs were developed as highly selective recognition elements for detecting hazardous food contaminants, notably AM, HAAs, and histamine, in various food matrices. For AM detection, diverse transduction platforms, including electrochemical sensors, fluorescence probes, photoelectrochemical devices, QCM systems, and SPR chips, were integrated with MIPs prepared via sol–gel processing, electropolymerization, surface polymerization, and UV-initiated polymerization. These approaches achieved remarkable sensitivities, with limits of detection ranging from picomolar to nanomolar levels, and demonstrated robust selectivity and reproducibility in real food samples such as potato chips, biscuits, bread, and fried potatoes [52,86,87,88,89,90]. Beyond acrylamide, MIP-based sensors using nucleobase-functionalized monomers have enabled impedimetric and capacitive detection of HAAs like 7,8-DiMeIQx in meat extracts [91,92], while a polypyrrole-MIP on a Au@Fe-BDC/N,S-GQD nanohybrid has facilitated ultra-trace voltammetric quantification of histamine in canned tuna and human serum [93]. Finally, an MIP hydrogel-modified electrode was reported to achieve sub-nanogram per milliliter detection of 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenyl-imidazo [4,5-b] pyridine (PhIP) in grilled chicken and roast duck [94]. Collectively, these works highlight that tailoring MIP composition, morphology, and the sensing interface can produce rapid, portable, and food-compatible detection systems that rival conventional chromatographic and immunoassay methods in sensitivity and selectivity while enabling on-site monitoring of food safety risks.

Table 5.

Recent examples of MIP-based sensors for the detection of acrylamide and heterocyclic amine in food matrices and in water.

4.4. Mycotoxins

Mycotoxins are relatively small but structurally complex molecules with strong UV/fluorescent signatures and moderate molecular mass. These features explain the wide use of optical transduction (fluorescence, SPR, colorimetry) and electrochemical readout, often coupled with sol–gel imprinting or surface MIPs to ensure accessible binding sites.

The reviewed articles (Table 6) highlight significant advances in the use of MIPs for the sensitive, selective, and rapid detection of mycotoxins in diverse food matrices. Electrochemical sensing platforms achieved high performance for single targets such as ochratoxin A (OTA) via Nb2C-MWCNT-enhanced MIP films with a 3.6 × 10−9 M LOD [95] and zearalenone (ZEN) using pyrrole-based electropolymerization with sub-ng L−1 sensitivity [96]. Optical and hybrid methods further broadened their applicability: Ce-MOF@MIP colorimetric sensors enabled visual aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) detection at 8.0 × 10−10 M in peanuts, corn, and feed [70], while a bulk MAA-based MIP in carbon-paste electrodes provided 7.40 × 10−12 M detection in corn and wheat [97]. Dual-mode fluorescence/colorimetry with aptamer-MIP sandwiches reached picogram-level LODs for AFB1 in edible oils [71], and ECL sensing with MXene/BiVO4 heterojunctions quantified deoxynivalenol (DON) down to 5.4 × 10−13 M in corn flour [98]. Novel strategies included wireless bipolar electrochemistry with MIP-coated electrodes for ZEN [72], fluorescence quenching of carbon dots by magnetic MIP-captured ZEN with a 4.40 × 10−10 M LOD [99], and smartphone-based dual-colorimetric MIP-aptamer sensors for simultaneous AFB1 and OTA detection at sub-0.1 ng mL−1 levels in grains [100]. Together, these works demonstrate that integrating MIPs with advanced nanomaterials and optical/electrochemical transduction can deliver portable, low-cost, and regulatory-compliant mycotoxin detection tools for food safety monitoring.

Table 6.

Recent examples of MIP-based sensors for the detection of mycotoxins in food matrices.

The MIP-based sensors developed for mycotoxin detection exhibit high analytical sensitivity, with LODs typically falling in the pg·mL−1 to ng·mL−1 range depending on the transduction method employed. Optical platforms (fluorescence, SPR, colorimetric assays) generally achieve the lowest LODs due to strong signal amplification and the intrinsic optical activity of mycotoxins, while electrochemical approaches also provide competitive sensitivity with simple and low-cost instrumentation. Most studies report good repeatability, with RSD values often below 5–8%, and several platforms demonstrate reusability over multiple binding–regeneration cycles thanks to the chemical robustness of MIPs.

When compared with regulatory thresholds, these sensors show strong relevance: for many mycotoxins, maximum limits set by the EU or Codex Alimentarius (typically in the µg·kg−1 range, e.g., 2–5 µg·kg−1 for aflatoxin B1 in certain foods or 750–2000 µg·kg−1 for DON) are orders of magnitude above the LODs achieved by the majority of the reported MIP-based sensors. This indicates that the sensors summarized in Table 6 are more than sufficiently sensitive to monitor mycotoxin contamination at levels required by current regulations. A few early-stage studies performed in controlled laboratory matrices report higher LODs, but still within the range suitable for preliminary screening. Overall, these results confirm the strong potential of MIP-based sensors for regulatory-compliant and routine monitoring of mycotoxins in food products.

4.5. Heavy Metals

Heavy metal ions lack a defined molecular structure and require coordination chemistry-driven imprinting, which explains the dominance of ion-imprinted polymers (IIPs), chelating monomers, and electrochemical detection. Their charge and redox behavior make them extremely compatible with potentiometry, stripping voltammetry, and impedance-based sensing.

The reviewed articles (Table 7) demonstrate significant advances in the application of MIPs and ion-imprinted polymers (IIPs) for the selective and sensitive detection of heavy metals in food and water matrices. Targets ranged from single ions such as Hg2+[101] and As3+ [102] to multiple species like Pb2+/Hg2+ [103] and Cd2+/Hg2+ [104], with detection limits often reaching the picomolar level, as in the potentiometric Pb2+ sensor described by Ardalani et al. [66] and the nanoporous-gold-based As3+ sensor reported by Ma et al. [102]. Diverse transduction methods were employed, including voltammetric techniques such as SWV and DPV [67,105,106,107], potentiometry [66], and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy [102,108]. MIP deposition strategies ranged from in situ electropolymerization of monomers like pyrrole [101,105] and o-phenylenediamine [102,108] to the incorporation of biopolymers such as chitosan [103,106,107] and dopamine [104]. Functional monomers were often combined with specific chelating ligands (e.g., terpyridine in Ardalani et al. [66]; 2-(2-aminophenyl)-1H-benzimidazole in Dahaghin et al. [67]) to improve selectivity. Many sensors were successfully applied to complex real samples, including seafood [103,104], milk [107], fruit juice [67], and environmental waters [102,106,108], demonstrating their practical feasibility. Overall, the integration of nanomaterials, aptamers, and optimized imprinting chemistry has led to remarkable improvements in sensitivity, selectivity, and applicability of MIP-based electrochemical sensors for heavy-metal monitoring in food safety and environmental protection.

Table 7.

Recent examples of MIP-based sensors for the detection of heavy metals in food matrices and in water.

The MIP- and IIP-based sensors developed for heavy metal detection demonstrate strong analytical performance, with LODs typically reported in the low ng·L−1 to µg·L−1 range depending on the transduction method used. Electrochemical platforms, especially those based on stripping voltammetry or impedance measurements, generally provide the highest sensitivity due to efficient preconcentration at the polymer electrode interface. Mass-sensitive and optical systems also yield competitive detection limits, although they require more complex instrumentation. Across studies, repeatability is typically satisfactory (RSD < 5–10%), and several IIP/MIP films exhibit good operational stability and reusability over multiple measurement cycles.

From a regulatory perspective, maximum allowable concentrations for toxic metals in food and drinking water (e.g., lead, cadmium, mercury) usually fall within the µg·kg−1 or µg·L−1 range as defined by the WHO/FAO and EU regulations. The LODs obtained by most sensors in Table 7 are well below these regulatory thresholds, showing that the proposed MIP/IIP-based platforms can detect heavy metals at concentrations relevant for compliance monitoring. Overall, the results confirm the suitability of MIP- and IIP-based sensors for sensitive, selective, and regulation-aligned monitoring of heavy metal contaminants in food and water matrices.

4.6. Food Allergens

Food allergens are large proteins that cannot be imprinted via bulk imprinting. Surface imprinting, electropolymerization, or epitope imprinting are therefore required to ensure steric accessibility. Their large molecular mass and refractive index changes make them excellent targets for electrochemical, SPR, or mass-sensitive detection.

The reviewed articles (Table 8) showcase recent advances in MIP and ion-imprinted polymer-inspired platforms for highly selective allergen detection in food, combining nanomaterials, electropolymerization, and hybrid receptor strategies to achieve ultra-low detection limits. Reported targets include major allergens such as ovalbumin [68,69], soy markers like genistein [109] and soybean trypsin inhibitor [110], β-lactoglobulin [12], gluten/gliadin [111,112], hazelnut allergen Cor a 14 [113], and lysozyme [25,112]. Transduction relied mainly on electrochemical methods such as DPV, SWV, EIS, and amperometry, with some incorporating dual readouts like Surface Plasmon Resonance [113] or thermal heat-transfer sensing [114]. MIP deposition was most often achieved by in situ electropolymerization of functional monomers such as o-phenylenediamine [25,109,112], pyrrole [110,113], or dopamine [69], while others used magnetic MIPs [68,111] or nanoMIPs from solid-phase synthesis [114]. Detection limits spanned from the low-nanomolar [69] down to the sub-attogram level [110] and even femtomolar or lower [112,114], well below regulatory thresholds for allergen labeling. Many approaches demonstrated applicability in complex food matrices such as wine, beer, cookies, pasta, milk, gluten-free products, and processed meat, confirming their potential for real-world allergen monitoring in food safety control.

Table 8.

Recent examples of MIP-based sensors for the detection of food allergens.

MIP-based sensors for allergen detection show promising potential for commercial translation, mainly because MIPs offer several advantages over traditional antibody-based kits widely used in the food industry: they are cost-effective, stable at varying temperatures and pH, compatible with portable instrumentation, and reusable after simple regeneration steps. These properties make them attractive candidates for on-site allergen monitoring during food processing and quality control. However, commercialization requires robust validation and standardization. One key challenge remains sensor reproducibility, as small variations in template removal, film thickness, or electropolymerization conditions may influence binding performance. Recent approaches such as solid-phase synthesis of nanoMIPs, surface imprinting on standardized substrates, magnetic MIPs, and controlled electropolymerization significantly improve batch-to-batch reproducibility and operational stability. Together, these developments suggest that commercially viable MIP-based allergen sensors are feasible, provided that fabrication protocols and quality-control procedures continue to be harmonized.

4.7. Viruses

Viruses are large, fragile biological structures requiring mild imprinting conditions such as epitope imprinting or solid-phase nanoMIPs. Their size makes them particularly suitable for mass-sensitive (QCM) and optical transduction, although electrochemical methods are also effective when surface imprinting is used.

The reviewed studies (Table 9) demonstrate the growing potential of MIPs as robust, low-cost, and selective synthetic receptors for virus detection in food and environmental matrices. Bai and Spivak [116] developed a double-imprinted aptamer-hydrogel diffraction grating sensor enabling naked-eye detection of Apple Stem Pitting Virus (ASPV) at 10,000 pg/mL. Altintas et al. [117] reported the first SPR biosensor using MIP nanoparticles for the bacteriophage MS2, offering high specificity and regeneration capability for waterborne virus monitoring. Wankar et al. [118] fabricated polythiophene nanofilm-based fluorescence sensors with a 2.29 pg/mL LOD for Tobacco Necrosis Virus (TNV) in water. Singh et al. [119] produced a polypyrrole-based nanocavity sensor for rapid Bean Pod Mottle Virus (BPMV) detection in soybean leaves, achieving an LOD of 41 pg/mL and <2 min detection. Kaur et al. [120] created epitope-imprinted nanoMIPs for human norovirus, detecting virus-like particles in romaine lettuce via electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (3.4 pg/mL) and thermal sensing (6.5 pg/mL). Sehit et al. [73] present a portable piezoelectric biosensor combining computationally designed epitope-imprinted polymers (eIPs) with solid-phase synthesis to detect human adenovirus (HAdV). The epitope, selected from an accessible region of the viral capsid, is optimized through molecular dynamics simulations to guide smart monomer selection. The resulting synthetic receptors show outstanding performance, with a LOD of 102 PFU.mL−1 (Figure 2).

Table 9.

Recent examples of MIP-based sensors for the detection of viruses in food matrices and in water.

Figure 2.

Preparation of portable epitope-imprinted polymers (eIP)-QCM biosensor and piezoelectric-based adenovirus detection via a knob−cavity interaction (adapted from [73]). MUDA: 11-mercaptoundecanoic acid; EDC: 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide hydrochloride; NHS: N-hydroxysuccinimide.

Dann et al. [121] extended epitope-MIP technology to dual-strain norovirus detection (GI.1 and GII.4) in spinach with pg/mL-level sensitivity and 30 min analysis time. Collectively, these works highlight the versatility of MIPs across optical, electrochemical, and thermal transduction platforms, their capacity for rapid and sensitive detection without biological receptors, and their suitability for portable, on-site virus diagnostics in food safety and environmental surveillance.

4.8. Bacteria

Bacteria are large, micrometer-scale biological targets. Consequently, surface imprinting with electropolymerized films is the preferred strategy, combined with EIS or capacitance-based transduction. Their size and surface charge result in pronounced impedance changes upon binding, explaining the dominance of label-free electrochemical detection in this category.

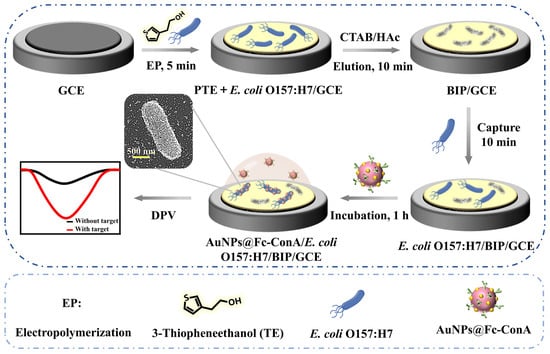

A review of recent developments in MIP-based sensors for bacterial detection in food (Table 10) reveals significant advances in sensitivity, selectivity, and practical applicability. The most targeted bacteria include Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus, with Salmonella species also receiving attention. The dominant transduction method employed is electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), valued for its label-free operation and high sensitivity [122,123,124]. Monomers such as poly(3-thiopheneacetic acid), 3-thiopheneethanol, pyrrole, and dopamine were frequently used due to their conductive properties and ability to form stable surface-imprinted layers [122,123,125]. Some studies introduced hybrid strategies combining MIPs with aptamers [126] or lectins such as concanavalin A (ConA) for enhanced specificity [127]. This study reports a sensitive sandwich-type electrochemical sensor for detecting E. coli O157:H7 using a dual-recognition approach that couples a bacteria-imprinted polymer (BIP) with ConA-functionalized, ferrocenyl-labeled gold nanoparticles. The BIP captures the target bacteria, while ConA binding triggers a measurable Fc oxidation signal proportional to bacterial concentration. The sensor achieves excellent performance, with a detection limit of 10 CFU mL−1, strong selectivity even against excess E. coli O6, and high accuracy in milk samples. This simple yet powerful strategy offers a promising tool for reliable food safety monitoring Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Schematic illustration for the fabrication process and operational principle of the electrochemical sensor for E. coli O157:H7 detection (adapted from [127]).

Limits of detection (LOD) across the studies ranged from as low as 2 CFU/mL for S. aureus [122] to 1000 CFU/mL for E. coli using thermal sensing [128], with most electrochemical methods achieving LODs below 25 CFU/mL. Real food matrices such as milk, pork, apple juice, shrimp, and lettuce were successfully tested, demonstrating the sensors’ robustness in complex samples [124,125,129]. The integration of MIPs into user-friendly platforms, including screen-printed electrodes and paper-based devices, highlights a shift toward rapid, on-site food pathogen monitoring technologies [125,129].

The development and validation of MIP-based sensors for viruses and bacteria in food matrices are intrinsically linked to biosafety constraints and selectivity challenges. Experiments involving pathogenic microorganisms must be conducted under appropriate biosafety levels (typically BSL-2 or higher), which often leads researchers to use inactivated particles, attenuated strains, or non-pathogenic surrogates (e.g., bacteriophages) as templates. While this approach improves safety and experimental feasibility, it may not fully reproduce the behavior of naturally contaminated food samples, especially in terms of matrix effects, aggregation, or interactions with native microbiota. In addition, cross-reactivity remains a major concern: closely related species and strains often share similar size, shape, and surface chemistry, which increases the risk of non-specific binding when whole cells or virions are imprinted. To mitigate these effects, several recent studies have explored epitope imprinting (using specific peptide fragments or capsid domains instead of whole particles), hybrid recognition architectures combining MIPs with aptamers or antibodies, and systematic selectivity testing against panels of non-target microorganisms present in food. Despite these advances, achieving robust biosafety compliance and stringent discrimination between target and non-target microorganisms remains a key challenge for the translation of virus- and bacteria-targeting MIP sensors into routine food safety monitoring.

Table 10.

Recent examples of MIP-based sensors for the detection of bacteria in food matrices and in water.

Table 10.

Recent examples of MIP-based sensors for the detection of bacteria in food matrices and in water.

| Target Bacteria | Transduction Method | MIP Deposition Method | LOD (CFU/mL) | Monomer Used | Real Sample Tested | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | Thermal (Heat Transfer Method) | Surface imprinting (polyurethane) | 1000 | Polyurethane | Milk | [128] |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) | In situ electropolymerization | 2 | Poly(3-thiopheneacetic acid) | Milk | [122] |

| Staphylococcus aureus | EIS | Electropolymerization (TE monomer) | 4 | 3-thiopheneethanol (TE) | Lettuce, Shrimp | [123] |

| Salmonella | EIS | Electropolymerization (MXene + PPy) | 23 | Pyrrole + MXene | Milk | [130] |

| E. coli O157:H7, S. aureus | EIS | Dual imprint via electropolymerization | 9 | o-Phenylenediamine | Apple juice | [124] |

| Escherichia coli | Colorimetric (Cu2+/OPD reaction) | Surface imprinting (dopamine on dPAD) | 25 | Dopamine | Drinking water, Juice, Milk | [129] |

| Salmonella typhimurium | Electrochemical (screen-printed) | Electropolymerization (dopamine) | ~10 | Dopamine | Milk, Pork | [125] |

| E. coli, S. aureus | Electrochemical Capacitance | Apta-MIP hybrid | 2 (E. coli), 4 (S. aureus) | (Aptamer + MIP based on dopamine) | Tap water | [126] |

| E. coli O157:H7 | Electrochemical (sandwich-type) | Surface imprinting + Au@Fc-ConA | 10 | 3-thiopheneethanol (TE) | Milk | [127] |

PPy: Polypyrrole; OPD: o-phenylenediamine; dPAD: distance-based paper analytical devices; Fc-ConA: 6-(ferrocenyl)hexanethiol-concanavalin A.

At the end of this section, we would like to focus on recent advances in food safety testing using MIP-based and microfluidic platforms. Recent advances in MIP-based sensors have significantly improved food safety testing. Maurya and Verma (2025) demonstrated a substrate-less MIP probe embedded with greenly synthesized nanoparticles for detecting formalin, a carcinogenic food preservative [131]. The probe exhibited high selectivity, a low limit of detection (1.55 × 10−5 M), and recovery of over 97% in real samples, highlighting the potential for low-cost, portable, and real-time monitoring of food adulteration within a linear detection range of 1.5 × 10−4–3 × 10−3 M. Similarly, Mahmodnezhad et al. (2025) developed an electrochemical MIP sensor combined with single-walled carbon nanotubes to detect the Zineb fungicide in various vegetables and fruits [132]. The sensor showed a linear detection range of 5 × 10−15–1 × 10−12 M, a low LOD of 1.6 × 10−15 M, and recovery of 98.85–102%, demonstrating its stability, selectivity, and applicability in real food samples. In addition, microfluidic platforms have enabled point-of-care testing for multiple contaminants simultaneously. Liu et al. (2024) reported a portable automated microfluidic system for detecting multiple mycotoxins in wine, integrating chemiluminescence imaging and microfluidic chips [133]. This platform allowed sensitive detection of zearalenone (3.14 × 10−9–1.01 × 10−7 M), aflatoxin B1 (6.4 × 10−10–2.05 × 10−8 M), and ochratoxin A (4.96 × 10−9–1.59 × 10−7 M), with recovery rates of 91–109%, emphasizing the potential of automated, rapid, and high-throughput food safety diagnostics, even in facilities lacking advanced laboratory infrastructure. Together, these studies illustrate how MIP sensors and microfluidic systems are transforming food safety testing by providing portable, cost-effective, and highly selective detection tools.

5. Comparison with Conventional Techniques

MIP-based sensors have gained significant traction in food analysis due to their ability to provide selective, stable, and portable detection [22]. However, their performance must be critically compared with conventional analytical methods that are widely used and trusted in regulatory and industrial settings. The advantages and limitations discussed in this section apply broadly to all MIP sensors beyond food contamination monitoring.

Conventional methods such as high-performance HPLC, GC, mass spectrometry (MS), ELISA, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) remain the gold standard for the detection of contaminants and allergens in food matrices. These methods are highly accurate and reproducible, but also come with limitations, including high cost, complex instrumentation, long turnaround times, and the need for skilled personnel.

In contrast, MIP-based sensors offer an attractive alternative for rapid screening, on-site detection, and decentralized food monitoring applications [134].

5.1. Advantages of MIP-Based Sensors

MIP sensors offer clear advantages for rapid, low-cost, and decentralized food testing [135]. Their reusability and robustness make them especially suitable for real-time, point-of-care, and in-field applications [136].

MIPs can be tailored to recognize specific target molecules with high fidelity, based on the “lock-and-key” principle. Unlike antibodies, they are resistant to denaturation and exhibit stable performance over a wide range of environmental conditions [137].

MIP sensors typically require minimal sample preparation and can deliver results in minutes, making them ideal for real-time or in-line quality control in food processing environments [134].

Once synthesized, MIPs are inexpensive to produce and can be reused multiple times without significant loss of sensitivity [138]. This significantly reduces the per-test cost compared to ELISA or LC-MS analyses.

MIP-based sensors can be integrated into compact platforms such as screen-printed electrodes [139], paper-based devices [140], or microfluidic chips, many of which are compatible with smartphone-based readout systems [141].

Unlike biological receptors, MIPs are resistant to temperature, pH fluctuations, organic solvents, and enzymatic degradation, which makes them ideal for use in harsh or variable food environments [142].

The following table (Table 11) compares MIP-based sensors to conventional methods in terms of selectivity, sensitivity, time-to-results, portability, cost, reusability, and matrix tolerance.

Table 11.

Comparison of MIP-based sensors with conventional methods.

MIP-based sensors offer several advantages over conventional analytical methods for food contaminants detection. Their molecularly tailored binding sites provide high selectivity comparable to antibody or primer-based assays, while achieving markedly superior sensitivity, often in the pico to femtomolar range. They also deliver results within minutes to under an hour, in contrast to chromatographic or immunoassay methods that typically require hours to days. Owing to the robustness and chemical stability of MIPs, these sensors are low-cost, reusable, and readily miniaturized for portable, on-site applications, whereas traditional methods rely on bulky, expensive laboratory instrumentation and single-use consumables. Moreover, MIP sensors exhibit strong tolerance to complex food matrices, reducing the need for extensive sample preparation that is usually required in conventional workflows. Collectively, these features make MIP-based sensors a powerful and practical alternative to classical laboratory-based approaches for rapid analyte monitoring in real matrices.

In terms of analytical figures of merit, conventional chromatographic techniques (LC-MS/MS, GC-MS) generally achieve the lowest LODs, often in the pg·mL−1 range for many food contaminants, but at the expense of long and multi-step workflows involving extraction, clean-up, separation, and data analysis, with total assay times typically of several hours per batch of samples. ELISA and PCR-based methods also offer very good sensitivity (low ng·mL−1 to pg·mL−1) but require multiple incubation/washing steps and specialized reagents, resulting in assay times of 1–4 h and relatively high per-test costs. In contrast, MIP-based sensors commonly reach LODs in the low nM to pM range (or ng·L−1 to pg·mL−1 when expressed in mass concentration) with measurement times on the order of minutes to less than one hour, particularly when integrated into electrochemical or optical point-of-need platforms. Once fabricated, the cost per analysis is typically low because the same MIP element can be reused multiple times after regeneration, and the instrumentation can be miniaturized. However, MIP sensors still face limitations related to batch-to-batch variability, incomplete standardization, and, at present, lower throughput than LC-MS/MS methods, which are able to quantify many analytes simultaneously in complex food matrices.

5.2. Limitations of MIP Sensors Compared to Traditional Techniques

Despite their advantages, MIP-based sensors are not without limitations.

- Template Leakage: Incomplete removal of the template during synthesis may result in background signals or false positives, especially at trace detection levels [143].

- Cross-reactivity: MIPs may sometimes bind to structurally similar non-target molecules if the imprinting conditions are not well optimized. This can compromise selectivity in complex food matrices [144].

- Reproducibility: Batch-to-batch variability in polymer morphology or binding site distribution can lead to inconsistent sensor performance, particularly in bulk polymerization methods [145].

- Lack of standardization: Most MIP-based sensors are still in the proof-of-concept or laboratory stage. They are not yet widely validated under standard regulatory frameworks (e.g., ISO, AOAC, EFSA), limiting their use in official quality control protocols.

- Lower throughput: While rapid, most MIP sensors are currently designed for single-analyte detection. In contrast, techniques like LC-MS/MS can analyze multiple contaminants simultaneously in a single run.

5.3. Practical Considerations and Complementarity

Rather than replacing conventional methods, MIP-based sensors are more likely to complement existing analytical workflows. For instance, MIPs can be used for on-site preliminary screening, reducing the number of samples that need to be analyzed via time-consuming laboratory techniques. In settings such as food trucks, farms, processing facilities, or import checkpoints, MIPs enable decentralized testing with minimal infrastructure. MIPs can be embedded into automated platforms, including lab-on-a-chip systems or IoT devices, for real-time monitoring and cloud-based decision support [76]. In developing regions or remote areas, MIP sensors provide a robust and affordable alternative where traditional laboratory equipment is unavailable.

6. Future Perspectives and Trends

MIP-based sensors have undergone remarkable progress over the past two decades, moving from proof-of-concept devices toward increasingly robust and application-ready technologies. As food safety challenges continue to evolve, driven by globalization, climate change, new contaminants, and shifting regulatory frameworks, MIPs are expected to play a central role in the development of next-generation sensing platforms. This section explores emerging trends and strategic directions that will shape the future landscape of MIP-based food contaminants and allergen detection.

One of the most impactful developments in recent years is the integration of MIPs with nanomaterials to enhance surface area, binding efficiency, signal amplification, and mechanical strength. Materials such as CNTs and graphene derivatives improve electron transfer in electrochemical sensors [44]. Metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) [146] and quantum dots offer optical sensitivity and surface tunability [147]. Magnetic nanoparticles (Fe3O4) facilitate easy separation and automation in sample preparation [148]. In hybrid systems, MIPs are combined with biological elements (e.g., aptamers or enzymes) to create apta-MIP [149] or enzymatic-MIP platforms, uniting the specificity of biomolecules with the robustness of polymers [150].

A major trend is the shift toward portable and user-friendly sensing platforms, particularly those that leverage smartphone integration. Miniaturized MIP-based sensors can be embedded into paper-based microfluidic devices (lab-on-paper) [151], wearable sensors for real-time exposure tracking [152], or plug-and-play formats compatible with USB or Bluetooth for smartphone readout [153]. Such devices enable point-of-need testing by non-expert users, farmers, food inspectors, and even consumers, facilitating real-time monitoring and immediate decision-making. This is especially valuable in remote or resource-limited regions where centralized lab access is restricted.

Traditional MIP sensors are often designed for single-analyte detection, which limits throughput. Recent advances are now enabling multiplexed MIP platforms, where multiple MIPs targeting different analytes are patterned or integrated on the same sensor surface. Microarray formats enable simultaneous detection of toxins on a single chip [100]. Barcode-based optical systems use colorimetric or fluorescent tags linked to specific imprinted layers [154]. Electrochemical arrays with individually addressable electrodes functionalized with different MIPs [155,156]. Such systems can dramatically increase the efficiency of screening for complex food matrices contaminated with diverse chemical and biological hazards.

The IoT is transforming food supply chains into interconnected smart systems. MIP-based sensors could be embedded in packaging materials (e.g., smart labels for spoilage detection) [157] or food processing lines (inline monitoring of contaminants) [158]. Combined with wireless data transmission, these sensors will enable real-time monitoring, automated alerts, and cloud-based analytics, ushering in the era of “smart food safety” systems.

As the complexity of food matrices increases, so does the need to interpret complex sensor data. Integration with machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) can significantly enhance MIP sensor performance by classifying signal patterns and identifying specific contaminants by compensating for matrix interference or environmental variability or by optimizing MIP design using computational modeling (e.g., monomer-template docking simulations). AI-powered platforms will likely enable adaptive, self-correcting sensors that improve with usage and accumulate knowledge over time. In parallel, 3D printing technologies have enabled the fabrication of highly structured MIP networks with enhanced adsorption and recognition capabilities. Rezanavaz et al. (2024) reported that 3D-printed MIPs achieved up to tenfold higher copper(II) ion adsorption compared to non-printed analogs, demonstrating precise control over morphology and porosity [159]. Collectively, these advances suggest that ML, AI, and additive manufacturing will play a pivotal role in the rational design, high-throughput optimization, and scalable production of MIPs, shaping the next generation of smart, selective, and efficient polymer-based sensors.

Sustainability is becoming a central concern in sensor development. MIP synthesis traditionally involves the use of organic solvents and cross-linkers that may not be environmentally benign. Emerging strategies include solvent-free or water-based polymerization [160], use of biodegradable monomers and templates [161], or recyclable or compostable sensor platforms [162]. Such innovations are essential to align food safety monitoring with environmental protection goals and circular economy principles.

While MIPs show impressive analytical performance, regulatory acceptance remains limited. Key steps toward standardization include Benchmarking against ISO/AOAC protocols, validation with certified reference materials, and long-term stability and reproducibility testing across multiple laboratories. Collaboration between academia, industry, and governmental agencies will be critical to establish standard operating procedures (SOPs) and accelerate the adoption of MIP-based sensors in regulated food safety monitoring programs.

The future of MIP-based sensing lies in the convergence of advanced materials, digital technologies, and data intelligence, all working together to create agile, accurate, and scalable solutions for food safety. These trends will not only enhance analytical capabilities but also democratize access to high-performance monitoring tools across the entire food supply chain.

7. Conclusions

MIP-based sensors have emerged as a powerful class of synthetic recognition tools in food safety analysis. Their inherent advantages, including high selectivity, robustness, cost-effectiveness, and compatibility with various transduction mechanisms, make them highly attractive alternatives or complements to conventional analytical methods.

This review has highlighted the diverse strategies for MIP synthesis, including bulk polymerization, surface imprinting, electropolymerization, and nanoMIP fabrication. We have discussed their successful integration into electrochemical, optical, thermal, and mass-sensitive sensing platforms. These systems have been effectively applied to detect a wide range of food contaminants, such as pesticides, antibiotics, heavy metals, mycotoxins, processing-induced hazards (e.g., acrylamide), allergens, viruses, and bacteria, with detection limits often reaching the picomolar or even femtomolar level.

Despite their considerable promise, MIP-based sensors still face several challenges, including template leakage, limited scalability, and regulatory acceptance. However, recent innovations such as multiplexed platforms, nanomaterial integration, epitope imprinting, and IoT-enabled readouts suggest that these issues can be addressed through interdisciplinary research and technological development.

In the coming years, MIP-based sensors are expected to play a crucial role in decentralized food monitoring systems, particularly in portable, real-time, and point-of-need applications. Their combination with smart devices and sustainable manufacturing practices will further enhance their impact. By bridging the gap between high-performance analytical chemistry and practical food safety tools, MIPs represent a transformative advance in modern sensor technology.

Author Contributions

Both authors contributed equally. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No data was generated in this work.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the International College leadership team, Tobin Wait, Michael Caleb Earnest, Boualem Maizia, Malda Halawi, Adnan Barada, and Faten Jibai, for their continuous support during the preparation of this manuscript, as well as Linda El Hosry for her valuable insight.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Shaw, I.C. Chemical Residues, Food Additives and Natural Toxicants in Food—The Cocktail Effect. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 49, 2149–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, L.A.; Darwish, W.S. Environmental Chemical Contaminants in Food: Review of a Global Problem. J. Toxicol. 2019, 2019, 2345283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirone, M.; Visciano, P.; Tofalo, R.; Suzzi, G. Editorial: Biological Hazards in Food. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 7, 2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rather, I.A.; Koh, W.Y.; Paek, W.K.; Lim, J. The Sources of Chemical Contaminants in Food and Their Health Implications. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartha, I.; Almulhem, N.; Santos, A.F. Feast for Thought: A Comprehensive Review of Food Allergy 2021–2023. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2024, 153, 576–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsagkaris, A.S.; Pulkrabova, J.; Hajslova, J. Optical Screening Methods for Pesticide Residue Detection in Food Matrices: Advances and Emerging Analytical Trends. Foods 2021, 10, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Su, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, K.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Duan, L.; Shi, F. Determination of Cyflufenamid Residues in 12 Foodstuffs by QuEChERS-HPLC-MS/MS. Food Chem. 2021, 362, 130148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.-L.; Gao, Y.; Wang, X.; Han, X.X.; Zhao, B. Comprehensive Strategy for Sample Preparation for the Analysis of Food Contaminants and Residues by GC–MS/MS: A Review of Recent Research Trends. Foods 2021, 10, 2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Gong, Q.; Liu, W.; Tan, S.; Xiao, J.; Chen, C. Applications of Capillary Electrophoresis in the Fields of Environmental, Pharmaceutical, Clinical, and Food Analysis (2019–2021). J. Sep. Sci. 2022, 45, 1918–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosseini, S.; Vázquez-Villegas, P.; Rito-Palomares, M.; Martinez-Chapa, S.O. Advantages, Disadvantages and Modifications of Conventional ELISA. In Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA): From A to Z; Hosseini, S., Vázquez-Villegas, P., Rito-Palomares, M., Martinez-Chapa, S.O., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 67–115. ISBN 978-981-10-6766-2. [Google Scholar]

- Sergeevich, O.A.; Bachelor, L.N.; Erbolatovich, D.A.; Alikulov, Z.; Kairbekovich, M.Z. Real-Time PCR: Advantages and Limitations. In Reviews of Modern Science, Proceedings of the 6th International Scientific Conference, Zürich, Switzerland, 16–17 May 2024; Universität Luzern: Lucerne, Switzerland, 2024; p. 285. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Pagett, M.; Zhang, W. Molecularly Imprinted Polymer (MIP) Based Electrochemical Sensors and Their Recent Advances in Health Applications. Sens. Actuators Rep. 2023, 5, 100153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svenson, J.; Nicholls, I.A. On the Thermal and Chemical Stability of Molecularly Imprinted Polymers. Anal. Chim. Acta 2001, 435, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Ge, Y.; Piletsky, S.A.; Lunec, J. Molecularly Imprinted Sensors: Overview and Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; ISBN 978-0-444-56333-0. [Google Scholar]

- Arreguin-Campos, R.; Jiménez-Monroy, K.L.; Diliën, H.; Cleij, T.J.; van Grinsven, B.; Eersels, K. Imprinted Polymers as Synthetic Receptors in Sensors for Food Safety. Biosensors 2021, 11, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fresco-Cala, B.; Batista, A.D.; Cárdenas, S. Molecularly Imprinted Polymer Micro- and Nano-Particles: A Review. Molecules 2020, 25, 4740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ait Lahcen, A.; Saidi, K.; Amine, A. A Critical Review of Electrosynthesized Molecularly Imprinted Polymers in Electrochemical Sensing: Pros and Cons. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2025, 54, 101752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amatatongchai, M.; Sroysee, W.; Sodkrathok, P.; Kesangam, N.; Chairam, S.; Jarujamrus, P. Novel Three-Dimensional Molecularly Imprinted Polymer-Coated Carbon Nanotubes (3D-CNTs@MIP) for Selective Detection of Profenofos in Food. Anal. Chim. Acta 2019, 1076, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhong, L.; Yu, X.; Zhai, H. Preparation of Sulfamethoxazole Molecularly Imprinted Polymers Based on Magnetic Metal–Organic Frameworks/Graphene Oxide Composites for the Selective Extraction of Sulfonamides in Food Samples. Microchem. J. 2022, 177, 107259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wu, Y.; Ma, X.; Pang, C.; Wang, M.; Xu, Z.; Li, B. Monitoring Levamisole in Food and the Environment with High Selectivity Using an Electrochemical Chiral Sensor Comprising an MOF and Molecularly Imprinted Polymer. Food Chem. 2024, 430, 137105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Meng, C.; Liu, H.; Sun, B. Progress in Research on Smartphone-Assisted MIP Optosensors for the on-Site Detection of Food Hazard Factors. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2024, 170, 117459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Ansari, A.; Li, Z.; Mazumdar, H.; Siddiqui, M.A.; Khan, A.; Ranjan, P.; Kaushik, A.; Vinu, A.; Kumar, P. Point-of-Care Health Diagnostics and Food Quality Monitoring by Molecularly Imprinted Polymers-Based Histamine Sensors. Adv. Sens. Res. 2025, 4, 2400132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosbach, K.; Ramström, O. The Emerging Technique of Molecular Imprinting and Its Future Impact on Biotechnology. Nat. Biotechnol. 1996, 14, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menaker, A.; Syritski, V.; Reut, J.; Öpik, A.; Horváth, V.; Gyurcsányi, R.E. Electrosynthesized Surface-Imprinted Conducting Polymer Microrods for Selective Protein Recognition. Adv. Mater. 2009, 21, 2271–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdoğan, N.Ö.; Uslu, B.; Aydoğdu Tığ, G. Development of an Electrochemical Biosensor Utilizing a Combined Aptamer and MIP Strategy for the Detection of the Food Allergen Lysozyme. Microchim. Acta 2023, 190, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.A.; Nantasenamat, C.; Piacham, T. Molecularly Imprinted Polymer for Human Viral Pathogen Detection. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 77, 1341–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canfarotta, F.; Czulak, J.; Betlem, K.; Sachdeva, A.; Eersels, K.; van Grinsven, B.; Cleij, T.J.; Peeters, M. A Novel Thermal Detection Method Based on Molecularly Imprinted Nanoparticles as Recognition Elements. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 2081–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motaharian, A.; Hajebrahimi, M.; Hosseini, M.R.M.; Khosrokhavar, R. Molecularly Imprinted Sol-Gel Sensing Film-Based Optical Sensor for Determination of Sulfasalazine Antibiotic. ChemistrySelect 2020, 5, 13191–13197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horemans, F.; Alenus, J.; Bongaers, E.; Weustenraed, A.; Thoelen, R.; Duchateau, J.; Lutsen, L.; Vanderzande, D.; Wagner, P.; Cleij, T.J. MIP-Based Sensor Platforms for the Detection of Histamine in the Nano- and Micromolar Range in Aqueous Media. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2010, 148, 392–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manickam, P.; Pasha, S.K.; Snipes, S.A.; Bhansali, S. A Reusable Electrochemical Biosensor for Monitoring of Small Molecules (Cortisol) Using Molecularly Imprinted Polymers. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2016, 164, B54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhachem, M.; Cayot, P.; Lerbret, A.; Bezverkhyy, I.; Karbowiak, T.; Abboud, M.; Maroun, R.G.; Bou-Maroun, E. Molecularly Imprinted Electrochemical Sensor for Fast and Direct Determination of Caffeic Acid in Wine. Microchem. J. 2025, 217, 114924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carballido, L.; Bou-Maroun, E.; Weber, G.; Bezverkhyy, I.; Karbowiak, T. A New Sol-Gel Fluorescent Sensor to Track Carbonyl Compounds. Talanta 2024, 279, 126569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazouz, Z.; Rahali, S.; Fourati, N.; Zerrouki, C.; Aloui, N.; Seydou, M.; Yaakoubi, N.; Chehimi, M.M.; Othmane, A.; Kalfat, R. Highly Selective Polypyrrole MIP-Based Gravimetric and Electrochemical Sensors for Picomolar Detection of Glyphosate. Sensors 2017, 17, 2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldara, M.; Lowdon, J.W.; Royakkers, J.; Peeters, M.; Cleij, T.J.; Diliën, H.; Eersels, K.; van Grinsven, B. A Molecularly Imprinted Polymer-Based Thermal Sensor for the Selective Detection of Melamine in Milk Samples. Foods 2022, 11, 2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacob, B.-C.; Bodoki, E.; Farcau, C.; Barbu-Tudoran, L.; Oprean, R. Study of the Molecular Recognition Mechanism of an Ultrathin MIP Film-Based Chiral Electrochemical Sensor. Electrochim. Acta 2016, 217, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, W.; Biyikal, M.; Wagner, R.; Sellergren, B.; Rurack, K. Fluorescent Sensory Microparticles That “Light-up” Consisting of a Silica Core and a Molecularly Imprinted Polymer (MIP) Shell. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 7023–7027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Ma, Y.; Sun, H.; Huang, C.; Shen, X. Molecularly Imprinted Polymers Based Optical Fiber Sensors: A Review. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2022, 152, 116608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.; Griffete, N.; Lamouri, A.; Felidj, N.; Chehimi, M.M.; Mangeney, C. Nanocomposites of Gold Nanoparticles@Molecularly Imprinted Polymers: Chemistry, Processing, and Applications in Sensors. Chem. Mater. 2015, 27, 5464–5478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, M.Z.; Li, S.; Roopesh, M.S.; Lu, X. Development of a Microfluidic Device to Enrich and Detect Zearalenone in Food Using Quantum Dot-Embedded Molecularly Imprinted Polymers. Lab Chip 2024, 24, 2700–2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Qiu, J.; Zhu, C.; Hua, Y.; Yu, J.; Jia, L.; Xu, J.; Li, J.; Li, Q. A Fluorescent Molecularly Imprinted Polymer-Coated Paper Sensor for On-Site and Rapid Detection of Glyphosate. Molecules 2023, 28, 2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, S.; Kim, S.H.; Heo, G.; Heo, H.J.; Chae, S.Y.; Kwon, Y.W.; Lee, S.-K.; Han, D.-W.; Kim, H.-J.; Kim, Y.H.; et al. A Wearable Electrochemical Biosensor for Salivary Detection of Periodontal Inflammation Biomarkers: Molecularly Imprinted Polymer Sensor with Deep Learning Integration. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e09658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayerdurai, V.; Cieplak, M.; Kutner, W. Molecularly Imprinted Polymer-Based Electrochemical Sensors for Food Contaminants Determination. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2023, 158, 116830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamalasekaran, K.; Sundramoorthy, A.K. Applications of Chemically Modified Screen-Printed Electrodes in Food Analysis and Quality Monitoring: A Review. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 27957–27971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Z.; Shi, Y.; Liu, S.; Lv, Y.; Wang, S. DFT-Assisted Design of a Electrochemical Sensor Based on MIP/CNT/MoS2-CoNi for the Detection of Sulfamethazine in Meat. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2025, 140, 107261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]