Abstract

Zinc sulfide nanomaterials (ZnS NMs) are widely used in many important technological applications, and the performance efficiency is determined by the nanostructure, size, and shape. This indicates that achieving a desirable surface architecture is pivotal for any application. One of the efficient and cost-effective techniques, the hydrothermal method, offers uniform size, specific shape, and bulk synthesis capability. This research deals with the preparation of ZnS NMs exhibiting unique surface structures such as spherical, nano-pentagon, and nano-hexagon shapes through employing different zinc precursors and surfactants. The obtained material’s crystal structure was classified as cubic sphalerite and exhibited high purity, as analyzed by XRD, SEM-EDX, TEM, and XPS. Furthermore, the synthesized ZnS NMs were tested for their shape-dependent biosensing application, such as specific antibacterial tests against routine human pathogens such as E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and S. aureus. Several antibacterial methods, such as bacterial colony plate count, growth inhibition analysis, and minimum inhibition concentration (MIC) measurements were carried out. The results confirmed that the antibacterial action in the method employed was dependent on three factors: the NM shape, concentration, and type/nature of bacteria. Especially, the prepared ZnS NMs exhibited excellent antibacterial sensing characteristics, as observed from the lower MIC values in the range of 15.6~250 µg/mL.

1. Introduction

Zinc sulfide (ZnS) is a group II–VI wide direct bandgap semiconducting material that finds many potential applications, such as in electronics as light-emitting diode materials [1,2], in chemical industries as visible-light photocatalysts for dye degradation [3,4], as quantum dot luminescent materials for medical bio-imaging [5], and as additives in polymer membranes for improved antifouling and porosity (on account of high mechanical and chemical stability) [6]. The stable room temperature formation of cubic zinc blende sphalerite crystal structures of ZnS (below 1020 °C) was reported to show a band gap of 3.72 eV, a high refractive index of 2.27 at 1 µm, and high mean surface energy [7]. All of these beneficial physicochemical characteristics facilitate wide usage of ZnS NMs. The size and shape of ZnS NMs are important parameters (which decide charge migration, functionalization possibility, dispersion, mobility, etc.) for the above, and future technical applications and can be controlled by specific routes of synthesis. For example, the hydrothermal method is a good choice for dimensional control of NMs, usually producing high yield, reproducible results, and being generally cost-effective. The type of precursor, reaction duration, concentration, and temperature are some of the factors that determine the product surface morphology [8]. In addition, materials produced using this approach routinely exhibit high-temperature stability because they are prepared under high-pressure conditions.

To enhance further stability (structural and chemical) and non-aggregation in the morphology of the product, organic materials [9] such as polyethylene glycol (PEG), polyvinylpyrollidone (PVP), docylamine, hydrazine, etc., can be used and later eliminated by purification and heat treatment. These surfactant materials also act as template or structure or growth-directing agents which facilitate the base structure, coordinate with metal precursors [10] and result in different morphological features. The surfactants confine materials’ growth in the nanometer regime and control the morphology and size by selective adsorption on the specific surface of the crystal [11,12]. In the case of ZnS NMs, some selected structures such as microspheres, nanobelts, nanosheets, and flower-like features were observed routinely by employing different routes of preparation and surfactants [13], but to our knowledge, nano-pentagon and hexagon-type unique features were not found. In this research, different concentrations of zinc source and surfactant materials were used to prepare spherical, unique nano-pentagon, and nano-hexagon-like ZnS NMs by employing hydrothermal approach. Some selective combinations yielding good surface morphology are discussed. Furthermore, the prepared NMs are used to test their biosensing capability by following antibacterial activity against selected human pathogens.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Synthesis Procedure

Zinc nitrate hexahydrate (N2O6Zn·6H2O, M.W. 297.49 g·mol−1), zinc chloride (ZnCl2, M.W. 136.28 g·mol−1), and sodium sulfide (Na2S, M.W. 78.04 g·mol−1) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemie, Gmbh, Taufkirchen, Germany, and zinc sulfate heptahydrate (ZnSO4·7H2O, M.W. 287.56 g·mol−1, Junsei Chemical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) was used as received. The zinc precursors, Na2S solutions, and surfactants (PEG, M.W. 20,000 g·mol−1 and PVP, M.W. 40,000 g·mol−1, Sigma Aldrich Chemie, Gmbh, Germany) were prepared in the concentration mentioned in Table 1 (combinations were selected after optimization). The combination of solutions (15 mL each) was stirred for 10 min and then transferred to the 100 mL hydrothermal reactor and kept inside the furnace maintained at 175 °C (with a ramping rate of 5 °C min−1) for 30 h. At the end of the reaction, the precipitate was collected, purified many times with deionized water and ethanol, and then dried. The dried powders were again heat-treated at 300 °C for 6 h and further used for physicochemical characterization and biosensing application.

Table 1.

Concentration of precursors versus observed surface morphology of 4 different shapes of ZnS NMs.

2.2. Materials Characterization

A field emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM, JEM 1200 EX II, JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) fitted with EDX was employed to observe the particles’ surface morphology and elements presented. A transmission electron microscope (TEM) was also used for the analysis of nanoparticle morphology (JEM 2100F, JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) which operated with an accelerating voltage of 200 kV and beam value emission of 110 µA. The crystallinity of ZnS NMs was analyzed using an X-ray diffractometer (D/Max Ultima III, Rigaku corporation, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with monochromatic copper Kα radiation (λ = 0.154 nm) operating at 30 mA and an accelerating voltage of 40 kV. The surface chemical composition was investigated by an X-ray photoelectron spectrometer (ESCA 2000, VG Microtech, East Grinstead, UK) with monochromatic Mg Kα (1253.6 eV) radiation operating at 13 kV and 15 mA X-ray excitation source. The pass energy was 50 eV wide and the C1s (284.6 eV) was taken as a reference.

2.3. Antibacterial Activity Assay

The hydrothermally prepared ZnS NMs exhibiting different shapes were tested for their antibacterial properties against E. coli, K. pneumonia, and S. aureus human pathogenic bacterial strains using methods such as growth kinetics study, spreading plate count technique, and minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) determination. Firstly, the bacteria were sub-cultured in Luria–Bertani (LB) broth medium from the pure culture and then incubated overnight (at 37 °C) in a shaking incubator at 200 rpm to reach the colony-forming unit (CFU) of 1.0 × 106 per mL. The growth curve analysis from 0 to 24 h was carried out by optical density (OD 600) measurements. The ZnS NMs were diluted to 0.25, 0.5, and 1.0 mg/mL, added to the overnight-grown culture, and then OD was measured. Wells containing 96-well plates were used for the determination of 0~24 h incubated ZnS NM samples using a microplate reader. Secondly, for the spreading plate count method, LB agar plates were prepared, and then the strains with NM solutions were spread, and the plates were incubated for 24 h at 37 °C.

Finally, the broth micro-dilution method was performed to determine the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) [14]. In short, overnight-grown strains were diluted with LB broth to a final density of 1.0 × 106 per mL. Then the NMs were suspended in 0.9% sterile NaCl to a concentration of 8 mg/mL. The 100 μL of morphologically different ZnS NM solutions were serially diluted in a 96-well plate with 100 μL of LB broth against different bacterial strains. Positive bacterial control contains all reaction additives without any NMs, and only broth was added to the negative controls. Then, the plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h, and subsequently, a solubility agent (Alamar Blue) was added and incubated for 2 h. The wells showing metabolically active bacterial cells undergo a color change from blue to pink. The color changes corresponding to microbial growth and each bacterial strain’s MIC endpoint were noted. All the experiments were performed in triplicate; the mean and standard error (SE) were calculated. In this study, the inoculum size of 1.0 × 106 CFU/mL was intentionally selected because it is the inoculum level routinely used in our laboratory’s established protocol. Therefore, the MIC assay performed in this work did not strictly follow the CLSI or EUCAST standard, but rather followed a laboratory-validated in-house method that has been consistently used in our previous experiments. Regarding the use of Alamar Blue, the MIC was determined by visually assessing the color change (from blue to pink), which is a commonly used qualitative approach widely used in many microbiology laboratories.

2.4. Statistical Analysis Method

Statistical comparisons were performed using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test for comparing treatment groups with controls. All experiments were conducted with three independent replicates, and data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. This methodological transparency is used to reproduce the results.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Surface Morphological Study

3.1.1. The Surface Morphological Analysis Using FESEM

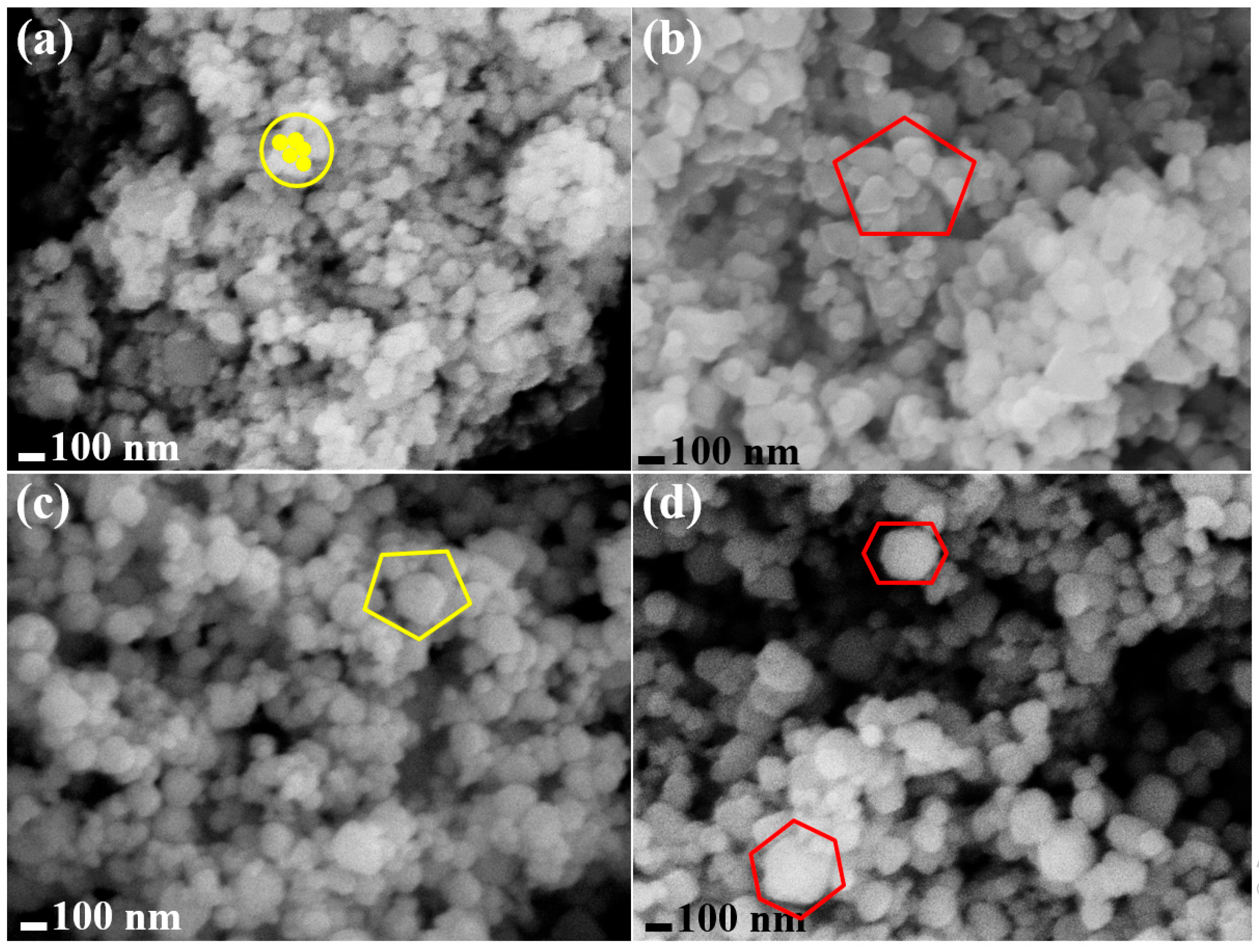

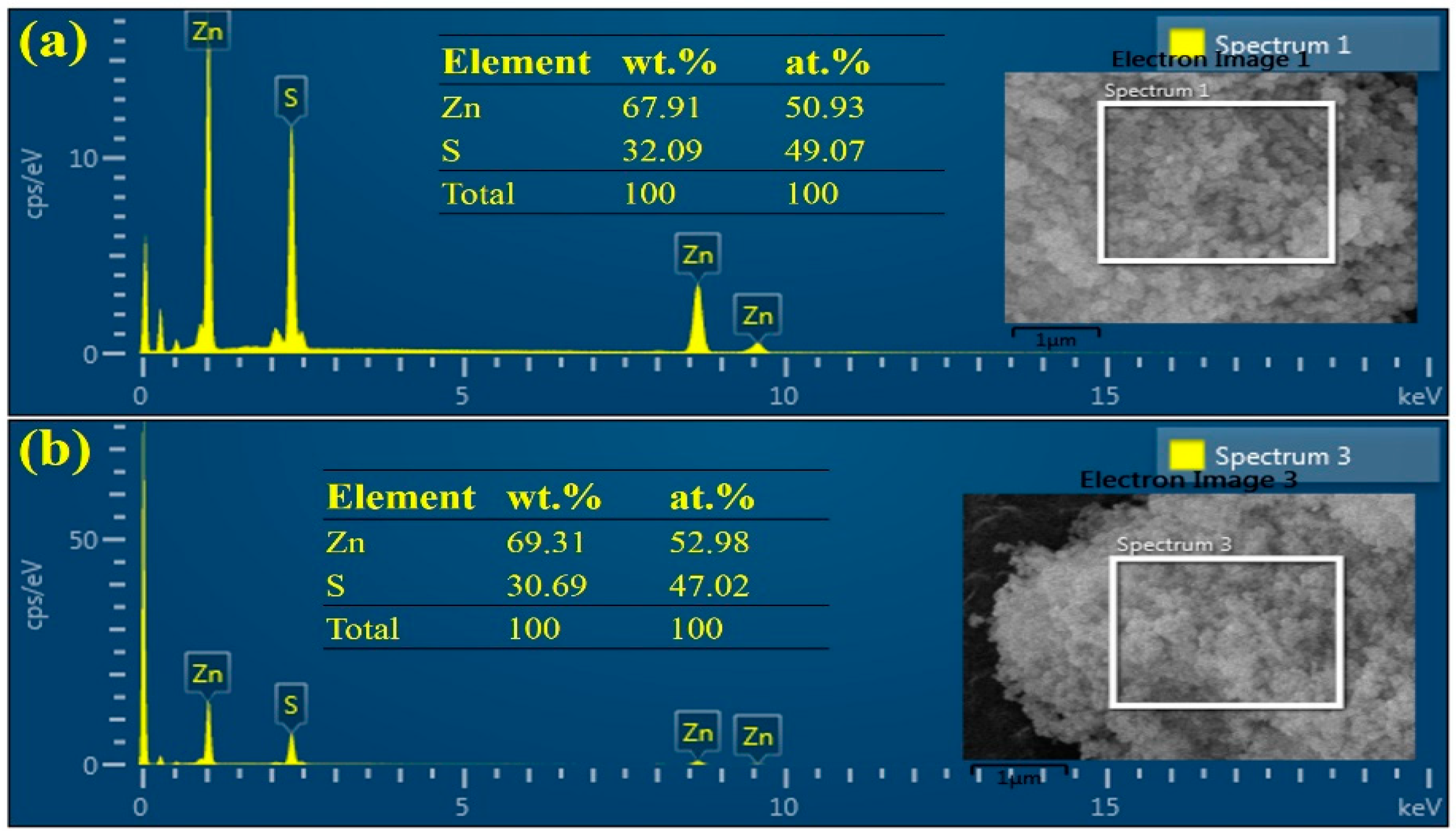

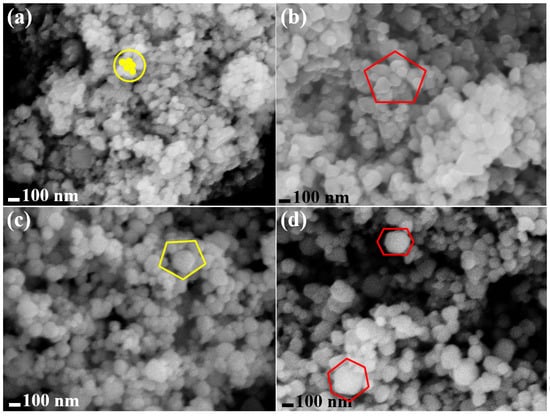

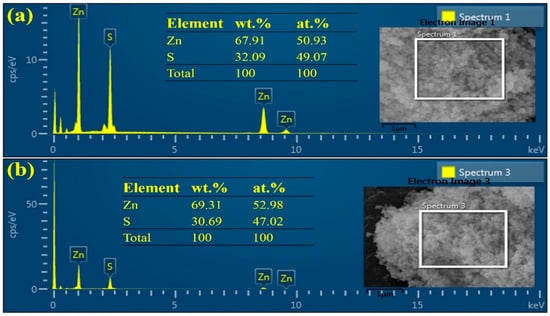

The FE-SEM surface morphological images of the prepared ZnS NMs are given in Figure 1. The ZnS NMs exhibited unique surface architectures such as spherical aggregates (see Figure 1a), layered pentagons, three-dimensional (3D) pentagons, and nano-hexagon shapes [see also Figure 1b–d]. The SPA ZnS showed less than 100 nm size, whereas other features exhibited between 50 and 250 nm in other dimensions but still within the nanometer regime. The LPEN ZnS looks like two dimensional (2D) flat pentagons, whereas 3DPEN and NHEX ZnS NMs seem to be 3D layered particles. The specific shapes are marked inside the images in Figure 1. The product exhibited excellent purity as measured by EDX spectra shown in Figure 2. Specifically, the SPA ZnS (Figure 2a) showed 67.91 and 32.09 wt.% of Zn and S, respectively, whereas NHEX ZnS (Figure 2b) showed 69.31 and 30.69 wt.%.

Figure 1.

The FE-SEM surface morphological images of the spherical aggregates (a), Layered pentagon (b), three dimensional pentagons (c), and nano-hexagon (d) shapes of ZnS NMs are shown. All images were taken at 50,000× magnification and 15.0 and 20.0 kV acceleration voltages.

Figure 2.

The energy dispersive X-ray spectra (EDX) of the samples [(a) SPA and (b) NHEX ZnS NMs] are given with their elemental composition. In Figure S2, the elemental composition, including the presence of oxygen, is shown.

3.1.2. The ZnS NMs Growth Mechanism in Hydrothermal Method

In general, the formation of NMs in the hydrothermal method occurs through hydrolysis and condensation reactions. The growth of NMs under supersaturation conditions involves four steps [15]: (i) transport of growth units through solution, (ii) attachment of them on the growth surface (reactor bottom or side surface if no templates are used), (iii) movement of growth units on the surface, and (iv) growth site attachment of the moving units. In the hydrothermal method, the morphological stability of NMs is predicted by the negative surface free energy and positive bulk free energy combination which depend on temperature, pH, and ion concentration. In other words, it depends on the growth rate, stoichiometry, and adsorbed species’ mobility. The free energy change increases when the temperature is lower than phase transition which promotes smaller nucleation barrier and critical cluster radius [16]. The liquid–solid mechanism states that the surfactants increase the sulfur-free radical concentration during the hydrothermal heating, and these radicals combine with Zn2+, resulting in high stability and a well-defined ZnS structure (Zn2+ + S· + e− → ZnS) [17]. The oriented attachment growth mechanism explains that the bonding takes place between particles by decreasing or removing the surface energy of unsatisfied bonds. The particles attain the lowest surface energy configurations and share the central crystallographic orientation [18]. It was stated that the mineralizer (in this case Na2S) and polymer additives act as structure directing agents. When only the mineralizer is used, the concentration will decide the morphology. If additives are used in addition to the same concentration of mineralizer, it controls the morphology by increasing the release of ions [Figure 1b–d], and in this situation, the crystal growth mechanism is ambiguous [12] or follows competitive growth towards different directions [19]. It further depends on the acid–base characteristics of the reacting species [20].

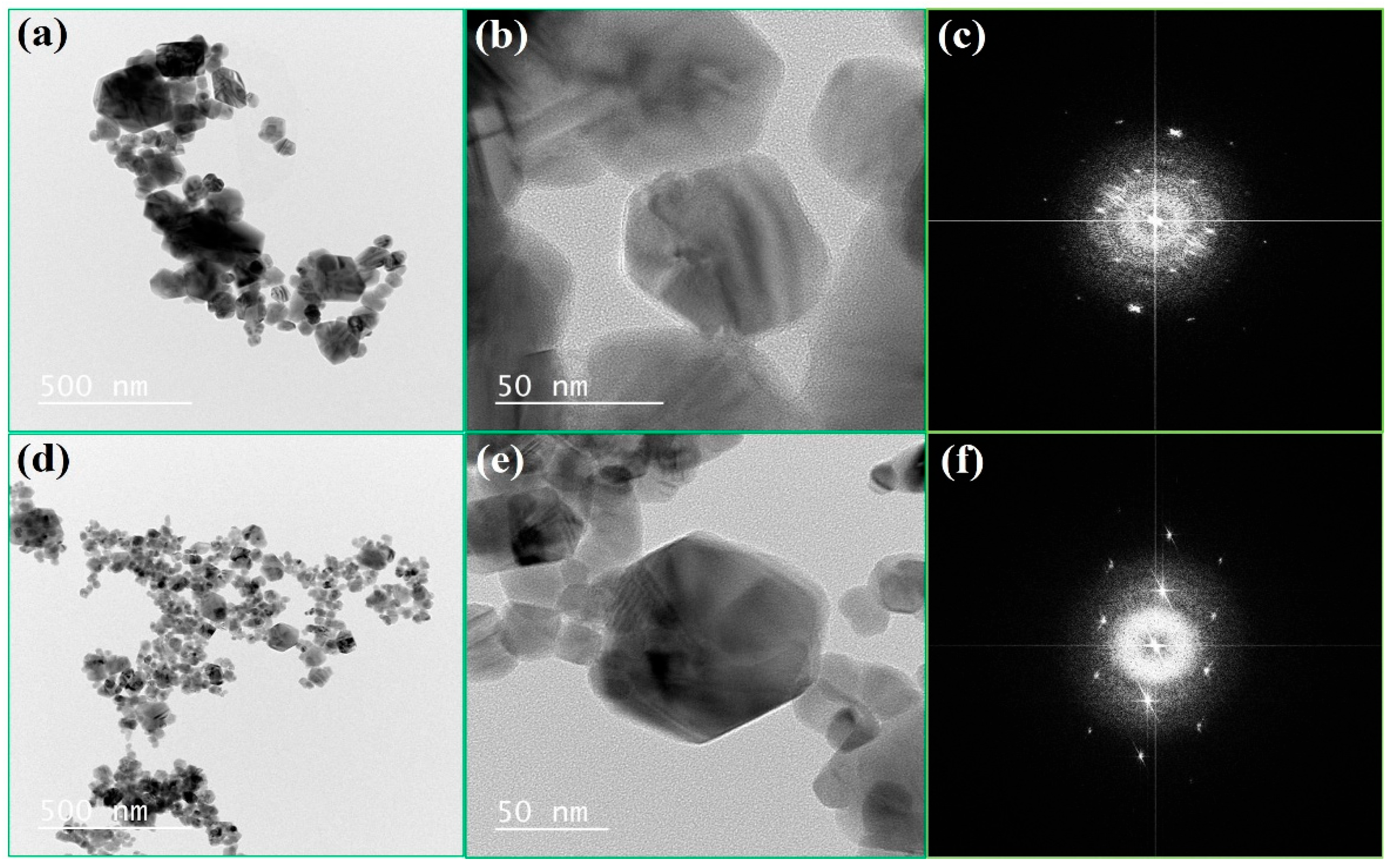

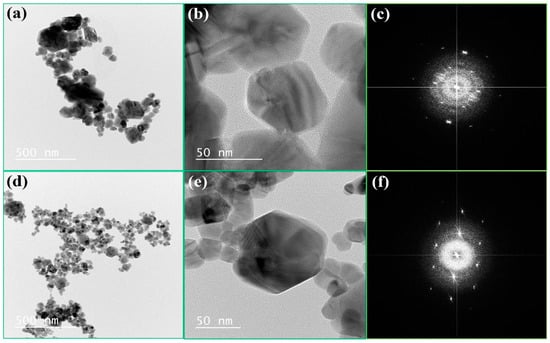

3.1.3. The Surface Morphological Analysis Using TEM

The typical TEM analysis observations for LPEN and NHEX ZnS NM samples are given in Figure 3. As we can see in Figure 3a,b, the LPEN ZnS confirmed the presence of pentagon-like surface features, mostly observed by FE-SEM, and some hexagonal shapes were also present here and there. It exhibited a mixture but based on the predominant shape, it can be referred to as nano-pentagons. The size range of LPEN ZnS varies between 50 and 250 nm (Figure 3a,b). In the case of NHEX ZnS, which showed (in the 2D projection of the 3D particles in TEM) major portions of hexagon-like surface structures with a narrow size distribution between 50 and 100 nm (Figure 3d,e). Figure 3c,f show the fast Fourier transform images (a modified form of selected area electron diffraction) of the LPEN and NHEX ZnS NMs. Comparing Figure 3c,f, we can see that the crystalline quality of the NHEX ZnS is better than that of the LPEN ZnS, suggest better sensing or higher antibacterial effect if it is used further.

Figure 3.

The typical TEM images observed for LPEN (a,b) and NHEX (d,e) samples and their fast Fourier transform images (c,f) are shown. Additional images are given in Figure S1.

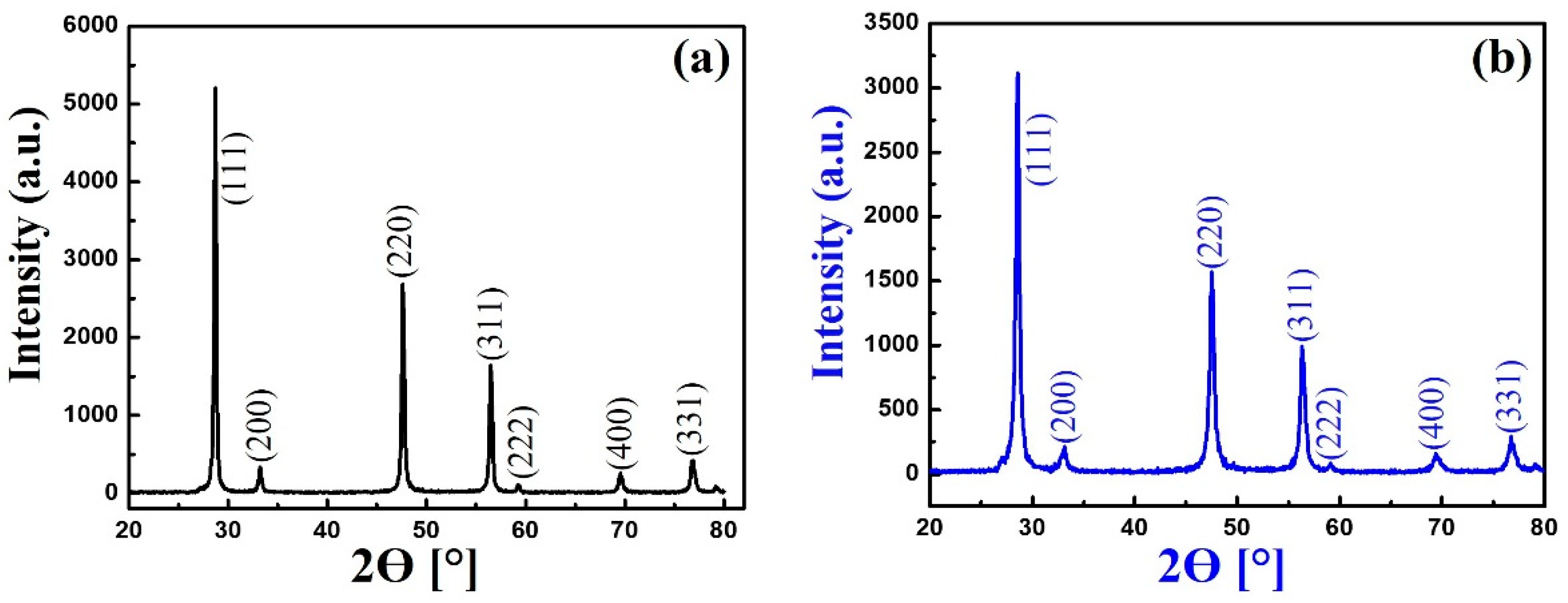

3.2. The X-Ray Diffraction Analysis

Figure 4 shows the X-ray diffraction spectra of SPA and NHEX, respectively. The prominent diffraction peaks observed at the scattering angle (2θ) 28.62, 33.18, 47.61, 56.54, 59.25, 69.52 and 76.88° correspond to (111), (200), (220), (311), (222), (400) and (331) planes, respectively, which is a face-centered cubic sphalerite (zinc blende) crystal structure of ZnS (Figure 4a) [21]. The crystallite size calculated using the Scherrer’s equation showed that it varied between 5.3865 and 5.4006 Å for SPA ZnS NMs (Table S1). The NHEX also exhibited a similar diffraction spectrum, but its crystallinity intensity is lower compared to SPA (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

X-ray diffraction patterns of SPA (a) and NHEX (b) ZnS NMs.

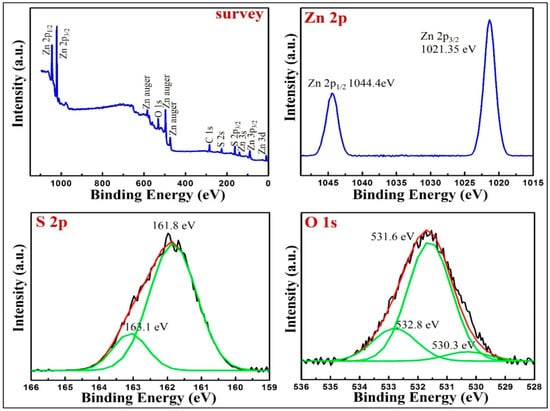

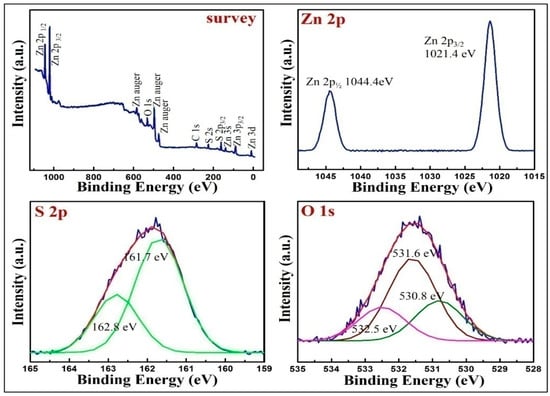

3.3. The Surface Chemical Analysis

Figure 5 shows the XPS surface chemical analysis results of SPA ZnS. The survey spectrum, core level high resolution spectra observed for Zn 2p, S 2p and O 1s are given in Figure 5. The survey spectrum showed the presence of Zn, S, O, and adventitious carbon signal and exhibited overall high purity of the product. The Zn 2p spectrum shows two peaks at the binding energy (B.E.) values 1021.35 and 1044.4 eV, corresponding to the Zn 2p3/2 and Zn 2p1/2 spin-orbital splitting of Zn2+ ions. The observed positions of the peaks suggest the presence of several S vacancies, showing a similar observation of the peaks at 1021.5 and 1044.5 eV [22] (see also Figure 6). The sulfur spectrum shows two Gauss–Lorentian de-convoluted peaks at the B.E. 161.8 and 163.1 eV, referring to the S 2p3/2 and S 2p1/2 of S2− in the ZnS phase [23,24]. The O 1s spectra exhibited three B.E. peaks at 530.3, 531.6, and 532.8 eV, corresponding to oxygen in three environments. The presence of oxygen is the result of surface hydroxyl, chemisorbed oxygen, and the lattice oxygen [25], which form surface Zn-O and Zn-OH [26], since ZnS can absorb moisture and undergo surface oxidation in an air atmosphere [27]. In addition, during the drying and heat treatments in the muffle furnace, the interaction of oxygen with ZnS was possible and varied between 4 and 6 wt.% formation (Figure S2). The XPS analysis results of NHEX ZnS are also given in Figure 6, showing a similar chemical composition as the one observed for SPA ZnS.

Figure 5.

The XPS survey spectra obtained for SPA ZnS. The core-level high-resolution spectra observed for Zn 2p, S 2p, and O 1s are shown.

Figure 6.

The XPS survey spectra obtained for NHEX ZnS. The core-level high-resolution spectra observed for Zn 2p, S 2p, and O 1s are shown.

3.4. Antibacterial Biosensing Studies of the ZnS NMs

The typical antibacterial activities of LPEN and 3DPEN ZnS NMs were studied against E. coli, S. aureus, and K. pneumoniae bacteria, and their growth kinetic curves are given in Figure 7. For the control sample, no NMs were added, and thus the bacterial density was very high, as observed from the absorbance value. All the NMs showed a significant growth inhibition (p < 0.05) against all the tested bacterial strains compared to the control. When using a low concentration of 0.25 mg/mL, the bacterial density initially decreased but increased over time. The highest growth inhibition was observed in 1.0 mg/mL ZnS NMs in all the samples, which showed the concentration dependence of the inhibition effect. When comparing the bacteria, the inhibitory effect of ZnS NMs was the highest against S. aureus, followed by K. Pneumonia and E.coli, as shown in Figure 7. In addition, the 3DPEN ZnS NMs show a slightly higher inhibition compared to LPEN (see Figure 7b,d,f).

Figure 7.

The growth kinetic curves observed for E. coli, S. aureus, and K. pneumoniae bacteria in the presence of LPEN (a,c,e) and 3DPEN (b,d,f) ZnS NMs. (The concentrations taken were varied between 0.25–1.0 mg/mL; The X-axis represents incubation time in hours (h or hr) and Y-axis represents optical density values).

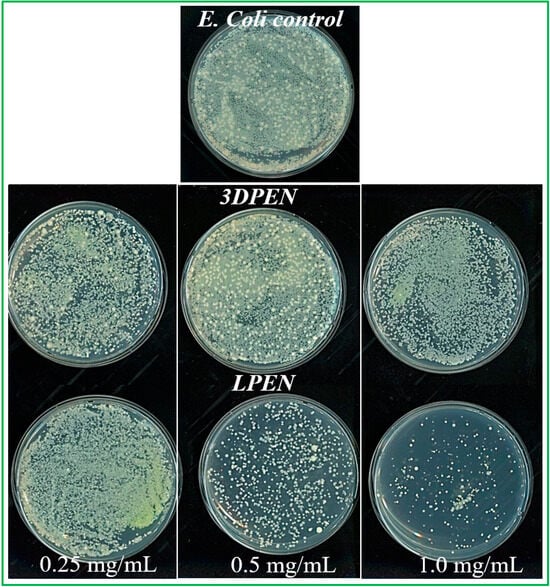

The effect of ZnS NMs (LPEN and 3DPEN) on the reduction of bacterial colony was evaluated in agar plates by the spreading method, and a representative image tested against E. coli is given in Figure 8. For the tested bacterial strains, ZnS NMs resulted in a considerable reduction in the colony numbers, and the highest reduction was noted for the 1.0 mg/mL concentration. At the same time, LPEN ZnS demonstrated higher bacterial colony reduction compared to 3DPEN ZnS in all concentration ranges such as from 0.25 to 1.0 mg/mL. The way NMs interact with bacteria might have given such results when compared with growth kinetics analysis. Conclusively, Figure 7 (growth kinetics) suggests that 3DPEN shows higher antibacterial effects than LPEN, while Figure 8 (the plate count method) indicates that LPEN demonstrates greater colony reduction than 3DPEN.

Figure 8.

The effect of different concentrations of ZnS NMs (LPEN and 3DPEN) on the E. coli bacterial colony is shown.

The observed results are obtained using antibacterial tests. The growth kinetics test is considered an interaction between ZnS NMs and the bacteria in liquid media. The NMs physically damage the cell wall and the subsequent release of zinc ions oxidatively damages the cell organelle, resulting in cell death. For achieving physical damage, the edges of NMs should be sharper. This is clear from the fact that the 3DPEN has sharper edges throughout its structure, which can damage the cell wall. Thus, a higher bactericidal effect was observed when the interaction took place in liquid media. In the case of plate count, it is considered as a solid–liquid interaction (NM mobility is lower compared to the 96-well method). As can be seen from the FESEM images in Figure 1, The LPEN and 3DPEN show similar size ranges topologically. But the LPEN exhibits clear flatness and small thickness, which means it can render a higher surface area-to-volume ratio compared to the 3DPEN. It further increases the reactivity of the NMs at the nanoscale, resulting in higher antibacterial activity.

The MIC Determination

The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values determined using the broth micro dilution method using SPA, LPEN, 3DPEN, and NHEX against the tested bacterial strains are listed in Table 2. The NM concentrations at which no or the least visible bacterial growth was observed were chosen as the MIC values. Table 2 shows the concentration ranges for which the bacteria showed no growth, and the values depended on the bacterial strains. The NHEX MIC was better than SPA compared to others, and LPEN and 3DPEN showed similar values. From the table it could be understood that the ZnS NMs prepared using the hydrothermal method are effective, showing broad-spectrum activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, though strain-specific. The obtained MIC values shown in Table 2 are lower (µg/mL range) than our previously reported values (see Supplementary Information, Table S2), which were in the mg/mL units.

Table 2.

The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values of the ZnS NMs determined against the tested bacterial strains.

From the above results, it can be seen that the antibacterial activity of ZnS NMs is dependent on the factors such as (a) concentration of the NMs used, (b) structure (shape), and (c) interaction method. The layered NMs (e.g., LPEN) could potentially damage the bacterial body structure by rupture in solution state, and its damage leads to the bacterial cell wall destruction, which is commonly known as the direct contact mechanism. The literature suggests that the formation of metal ions from the dissolution of ZnS NMs may adsorb on the bacterial surface and penetrate the cell membrane protein through the thiol group and disrupt biochemical pathways [28,29]. The release of metal ions was previously confirmed in our studies and found to vary between 3 and 60 ppm using the ZnS concentration ranges of 0.25~1.0 mg/mL [30]. In addition, it promotes oxidative damage (due to the formation of biologically active reactive oxygen species and radicals such as OH•, , and H2O2) by creating holes and thus the release of bacterial organelles, leading to death of bacterial cells [31].

4. Conclusions

The hydrothermal synthesis of ZnS NMs exhibited unique surface morphological features such as spherical, flat sheet-like pentagons, three-dimensional pentagons, and nano-hexagons by employing different zinc sources and the addition of PEG and PVP polymer surfactants. The available mechanisms of ZnS nanomaterial formation involving the role of surfactants, such as increasing the precursor ions, liquid-solid, and oriented growth mechanisms, were discussed. The synthesized NMs exhibited zinc blende crystal structures and high purity, as analyzed from the physicochemical characterization studies. The prepared ZnS NMs exhibiting different surface morphology were tested for their antibacterial properties against E. coli, S. aureus and K. pneumoniae using growth kinetics analysis, spreading plate count and MIC determination. The antibacterial activity was found to be dependent on the shape, concentration, and method of analysis (which indicated the way of interaction). Specifically, the ZnS NMs exhibited excellent antibacterial property as observed from the lower MIC values in the range of 15.6~250 µg/mL depending on the nature of bacteria. Among the three tested bacteria, the lowest MIC values were observed for the K. pneumoniae bacteria. In addition, the biosensing of antibacterial tests showed the broad-spectrum activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, although strain-specific variations were found.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/chemosensors13120419/s1. Figure S1: The TEM images of the ZnS NMs exhibiting LPEN (a–c) and NHEX (d–f) shapes, respectively. Figure S2: The energy dispersive X-ray spectra (EDX) of the samples (a) SPA and (b) NHEX ZnS NMs with its observed elemental compositions are shown. Table S1: The d-spacing and crystallite size of SPA ZnS NMs. Table S2: The MIC values of the ZnS NMs determined against the bacterial strains.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A. and I.H.; methodology, A.A. and I.H.; validation, A.A. and I.H.; formal analysis, A.A. and I.H.; investigation, A.A. and I.H.; resources, E.H.C. and J.-H.B.; data curation, A.A. and I.H.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.; writing—review and editing, I.H. and J.-H.B.; visualization, A.A.; supervision, E.H.C. and J.-H.B.; project administration, E.H.C. and J.-H.B.; funding acquisition, J.-H.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the NRF funded by the Ministry of Science & ICT (No. NRF-2019R1A6A1A10073079), Republic of Korea.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed at the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Suyver, J.F.; Wuister, S.F.; Kelly, J.J.; Meijerink, A. Synthesis and Photoluminescence of Nanocrystalline ZnS: Mn2+. Nano Lett. 2001, 1, 429–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Saleem, S.; Salman, M.; Khan, M. Synthesis, structural and optical properties of ZnS–ZnO nanocomposites. Chem. Phys. 2020, 248, 122900–122908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Huang, F.; Ren, G.; Li, D.; Zheng, M.; Wang, Y.; Lin, Z. ZnS nano-architectures: Photocatalysis, deactivation and regeneration. Nanoscale 2010, 2, 2062–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Yin, M.; Yao, Y. Synthesis of sphere-like ZnS architectures via a solvothermal method and their visible-light catalytic properties. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2017, 28, 17827–17832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hamidy, S.M. The optical behavior of multi-emission quantum dots based on Tb-doped ZnS developed via solvothermalroute for bio imaging applications. Optik-Inter. J. Light Elect. Optics 2020, 207, 163868–163873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Khan, S.; Cho, S.-H.; Kim, J. ZnS nanoparticles as new additive for polyethersulfone membrane in humic acid filtration. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2019, 79, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Porta, F.A.; Ferrer, M.M.; de Santana, Y.V.B.; Raubach, C.W.; Longo, V.M.; Sambrano, J.R.; Longo, E.; Andres, J.; Li, M.S.; Varela, J.A. Synthesis of wurtzite ZnS nanoparticles using the microwave assisted solvothermal method. J. Alloys. Compd. 2013, 556, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabaghi, V.; Davar, F.; Fereshteh, Z. ZnS nanoparticles prepared via simple reflux and hydrothermal method: Optical and photocatalytic properties. Ceram. Inter. 2018, 44, 7545–7556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yin, R.-H.; Wu, Q.-S. Solvothermal Synthesis of Well-Disperse ZnS Nanorods with Efficient Photocatalytic Properties. J. Nanomater. 2012, 2012, 560310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, L.; Du, J.; Xiong, S.; Li, H.; Zhu, Y.; Qian, Y. Synthesis of Wurtzite ZnS Nanowire Bundles Using a Solvothermal Technique. J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111, 12658–12662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananth, A.; Gregory, D.H.; Mok, Y.S. Synthesis, Characterization and Shape-Dependent Catalytic CO Oxidation Performance of Ruthenium Oxide Nanomaterials: Influence of Polymer Surfactant. Appl. Sci. 2015, 5, 344–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Yang, S.; Zhang, G.; Sun, Y.; Gao, D.; Sun, Y. Uniform hematite α-Fe2O3 nanoparticles: Morphology, size-controlled hydrothermal synthesis and formation mechanism. Mater. Lett. 2011, 65, 1911–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.-J.; Wu, J.J. Recent developments in ZnS photocatalysts from synthesis to photocatalytic applications—A review. Powder Technol. 2017, 318, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bayati, F.A. Synergistic antibacterial activity between Thymus vulgaris and Pimpinellaanisum essential oils and methanol extracts. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 116, 403–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, Q.; Wu, J. Synthesis of Nanoparticles via Solvothermal and Hydrothermal Methods. In Handbook of Nanoparticles; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 295–328. [Google Scholar]

- Rak, Z.; Brenner, D.W. Negative Surface Energies of Nickel Ferrite Nanoparticles under Hydrothermal Conditions. J. Nanomater. 2019, 2019, 5268415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibupoto, Z.H.; Khun, K.; Liu, X.; Willander, M. Hydrothermal Synthesis of Nanoclusters of ZnS Comprised on Nanowires. Nanomaterials 2013, 3, 564–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Zhang, S.; Xu, Z.; Ma, J.; Shen, X. Ultrathin ZnS Single Crystal Nanowires: Controlled Synthesis and Room-Temperature Ferromagnetism Properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 15605–15612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, G.H.; Yan, P.X.; Yan, D.; Fan, X.Y.; Wang, M.X.; Qu, D.X.; Liu, J.Z. Hydrothermal synthesis of single-crystal ZnS nanowires. Appl. Phys. A 2006, 84, 409–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Fang, P.; Wang, S. Synthesis of ZnS nanorod arrays by an aqua-solution hydrothermal process on pulse-plating Zn nanocrystallines. J. Mater. Res. 2009, 24, 2821–2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solatani, N.; Saion, E.; Hussein, M.Z.; Erfani, M.; Abedini, A.; Bahmanrokh, G.; Navasery, M.; Vaziri, P. Visible Light-Induced Degradation of Methylene Blue in the Presence of Photocatalytic ZnS and CdS Nanoparticles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 12242–12258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Huang, B.; Li, Z.; Lou, Z.; Wang, Z.; Dai, Y.; Whangbo, M.-H. Synthesis and characterization of ZnS with controlled amount of S vacancies for photocatalytic H2 production under visible light. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 8544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhu, B.; Wang, J.; Lan, H.; Chen, X. Synthesis of porous ZnS, ZnO and ZnS/ZnO nanosheets and their photocatalytic properties. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 30956–30962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, M.; Jiang, L.; Wu, L.; Zhang, M.; Wang, T. The structure control of ZnS/graphene composites and their excellent properties for lithium-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 13384–13389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hu, J.C.; Ngo, C.; Prikhodko, S.; Kodambaka, S.; Li, J.L.; Richards, R. Gram-scale wet chemical synthesis of wurtzite-8H nanoporous ZnS spheres with high photocatalytic activity. Appl. Catal. B 2011, 106, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyiriuka, E.C. Zinc phosphate glass surfaces studied by XPS. J. Non Cryst. Solid 1993, 163, 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertl, W. Surface Chemical Properties of Zinc Sulfide. Langmuir 1988, 4, 594–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mofokeng, T.P.; Moloto, M.J.; Shumbula, P.M.; Nyamukamba, P.K.; Takaidza, S.; Marais, L. Antimicrobial Activity of Amino Acid-Capped Zinc and Copper Sulphide Nanoparticles. J. Nanotechnol. 2018, 2018, 4902675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaliha, C.; Nath, B.K.; Verma, P.K.; Kalita, E. Synthesis of functionalized Cu:ZnS nano systems and its antibacterial potential. Arab. J. Chem. 2019, 12, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananth, A.; Han, I.; Akter, M.; Boo, J.-H.; Choi, E.H. Handy Soft Jet Plasma as an Effective Technique for Tailored Preparation of ZnS Nanomaterials and Shape Dependent Antibacterial Performance of ZnS. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2020, 90, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananth, A.; Dharaneedharan, S.; Heo, M.-S.; Mok, Y.S. Copper oxide nanomaterials: Synthesis, characterization and structure-specific antibacterial performance. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 262, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).