Abstract

This study investigates how natural language processing (NLP) can support the assessment and learning of science vocabulary among multilingual and multicultural learners, drawing on data from two federally funded studies in the United States. Students define and use target vocabulary in a sentence, with responses transcribed and scored using NLP tools. Employing a mixed-methods design and guided by established socioecological theoretical frameworks, we examine how students’ sociocultural contexts and background knowledge influence their understanding of science word knowledge and applicability. Our findings highlight both the potential and challenges of using AI tools in equitable and culturally responsive ways, offering insights to improve NPL-based assessment tools that support literacy teaching and learning in diverse student populations.

1. Using Natural Language Processing Within a Sociocultural Context to Measure Student Science Word Knowledge

Technology is becoming an increasingly ubiquitous part of our everyday lives, including within education. For a long time, attention was given to ensuring students and teachers had access to hardware to gain experience navigating these technologies (e.g., turning the machines on, playing repetitive games, or practicing typing). However, in a post-COVID-19 world, our students and teachers have more access to technology than ever before. Now, educators need to focus on what to use and how they can leverage these new tools to support student learning (Williamson et al., 2021).

In this exploratory study, we focus on the potential of a specific technological advancement, natural language processing (NLP), to reconceptualize the next generation of formative student assessment. NLP is a branch of artificial intelligence that gives computers the ability to engage with human language—including both written and spoken inputs. This brings new possibilities for assessments with constructed-response item formats (i.e., open-ended items), as NLP has the ability to assign scores and label values in responses (Botelho et al., 2023; Lottridge et al., 2023). This technology has been adapted to score essays, short answer responses, and speech across a variety of fields (Hirschberg & Manning, 2015). It is a scalable technology that can provide quick feedback, cheaper costs, and reliable scoring, which can be used to inform instruction (Hutson & Plate, 2023; Lottridge et al., 2023).

We report findings from the analysis of vocabulary outcomes in a formative assessment of two Institute of Education Sciences (IES) funded projects that examined NLP’s role in formative assessment of science vocabulary, particularly among elementary multilingual learners in the southern United States. In this study we include scores from all students, including multilingual learners, who participated in the projects. Formative assessments are designed to monitor student progress and guide instructional decisions (Heritage, 2007). Our study investigated how NLP can be used not only to score student responses but also to recognize and leverage students’ linguistic and cultural background knowledge as assets in understanding science concepts.

Our exploratory study emerged from our initial analysis of students’ open-ended vocabulary responses, which showed that they often drew on their linguistic and cultural assets to make sense of content and terminology. For example, while the word direction in English generally means a route or instruction, its Spanish translation (dirección) can also mean address. Traditionally, assessment development aims to minimize or remove factors such as these that are not directly related to the construct being measured, treating them as construct-irrelevant or a source of bias and would count the Spanish definition as incorrect. In contrast, we intend to capture these socioecological factors and use them as meaningful sources of information, utilizing NLPs to better understand how students, and particularly multilingual students interpret items, draw on their experiences, and apply academic language and concepts.

By combining the analytical power and recent advances in NLP with a framework that captures sociocultural factors in student responses, we aim to develop a more responsive, contextually informed assessment framework. This integrated approach enhances precision, scalability, timely feedback, and relevance to better reflect students’ lived experiences and knowledge.

2. Theoretical Framework

As we consider how to systematically incorporate the background knowledge and experiences students bring to assessments, we conceptualize a new socioecological assessment framework guided by well-established developmental and learning theories. These include Ecological Systems Theory (Bronfenbrenner, 2005) and Sociocultural Theory of Cognitive Development (Vygotsky, 1978).

2.1. Ecological Systems Theory

Using Ecological Systems Theory (Bronfenbrenner, 2005), learning is understood to occur within nested systems—microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, and macrosystem—that interact with one another. Drawing from this framework, we see students’ science vocabulary development is shaped by the interplay of these systems. Influences from the home, classroom, community, and broader cultural or policy contexts influence how students understand specific concepts. Our framework emphasizes the nested, multifaceted, and dynamic nature of these interactions. Currently, many assessments do not take individual backgrounds into account (American Educational Research Association et al., 2014). Using a socioecological model of assessment, it flips the script and makes these data essential to understand better how students make sense of words.

2.2. Sociocultural Theory of Cognitive Development

Drawing on Sociocultural Theory of Cognitive Development (Vygotsky, 1978), knowledge is viewed as co-constructed through social interaction and language use. Similarly, we see science learning as a social and collaborative process. This is essential for students to build knowledge and skills of scientific practices, which are a key focus of today’s science education (NGSS Lead States, 2013). For example, multilingual learners build understanding by using their cultural and linguistic resources, such as translanguaging, to make meaning in science contexts (García & Wei, 2014; Suárez, 2020).

3. Natural Language Processing

NLP models are artificial intelligence systems designed to process and generate human language by analyzing structural, semantic, and contextual patterns in language (Hirschberg & Manning, 2015). These models can analyze written or spoken language at a large scale, enabling the categorization of content, scoring text, and producing contextualized feedback efficiently and consistently (Hirschberg & Manning, 2015). In educational assessment, NLP is increasingly being used to analyze and score open-ended responses, such as defining key terminology and using it correctly within science contexts (Lottridge et al., 2023). NLP supports automated scoring, improves efficiency and reliability, and provides deeper insight into student thinking (Botelho et al., 2023; Somers et al., 2021). In addition to linguistic features such as syntax, semantics, and lexical complexity, NLP can be integrated with a socioecological scoring rubric to capture the contextual and sociocultural factors that influence students’ formation and understanding of science knowledge.

4. Socioecological Framework and Natural Language Processing

Aligning NLP with a socioecological framework can strengthen its utility for the next generation of formative assessments by leveraging its automated analytical capability within the broader contexts that shape student learning. While NLP holds promise for enabling culturally responsive assessments, it also raises important questions of equity, bias, and interpretation that must be addressed to ensure fair and meaningful use. By incorporating ecological systems and sociocultural theories, we position NLP not simply as an automated scoring mechanism for science knowledge but as an assessment tool responsive to students’ unique learning experiences that can more effectively inform teaching and learning and broader educational systems of equity, pedagogy, and policy. This research contributes to a growing body of literature that explores NLP as an assessment tool to support science literacy among multilingual and multicultural learners.

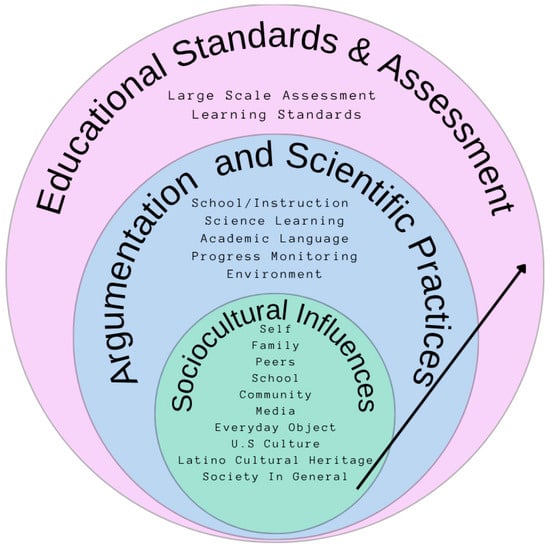

We represent these interrelated factors in Figure 1, adapting ideas from both Bronfenbrenner (2005) and Vygotsky (1978) to inform our approach to assessment. At the center of this work are our students, who come into assessments with unique backgrounds, cultures, and experiences that influence the way they make sense of the world. These experiences and background knowledge help shape how students learn to argue and discuss science phenomena using scientific practices learned at school. Finally, it is the combination of student socioecological influences and scientific practices that shape their opportunities to meet learning standards, inform testing standards, and validity frameworks. When aligned with this approach, NLP can capture these patterns in students’ responses, score them in more equitable ways that reflect their linguistic, cultural, and contextual reasoning, and report assessment data that better represents the socioecological and scientific practices in learning. Thus, to support student learning and ensure that they reach the learning standards, assessments need to take into account students’ backgrounds and experiences listed in the Sociocultural Influences and the Argumentation and Scientific Practices factors shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Socioecological Model for Assessment, Adapted from Bronfenbrenner (2005) and Vygotsky (1978).

5. Use of Natural Language Processing Tools in Assessment

Literature has begun exploring the use of NLP in educational settings, such as assessments and interventions—a shift from its traditional applications in technology and business sectors. This study utilizes an NLP as a cost-efficient tool to capture large quantities of student data to inform educators, school administrators, and education researchers about student progress. Rodriguez-Ruiz et al. (2021) explored NLP to assess students’ digital literacy skills, finding that it to be a valuable tool to limit teacher bias and provide helpful feedback for follow-up instruction. Somers et al. (2021) used NLP to explore students’ written responses, looking for students’ reasoning and confidence level within responses to compliment other data (i.e., multiple-choice answers and whether students mentioned key concepts). As another example, Li (2025) explored the use of NLP as a thought buddy in a written science assessment with middle school students, highlighting that interaction with the tool helped students expand their ideas when responding to science stories. However, these examples look at content knowledge as separate from students’ socioecological knowledge.

We argue that excluding students’ linguistic and cultural backgrounds severely limits our understanding of what students know and are ready to learn (Caldas, 2013; Huddleston, 2014; Noble et al., 2023; Sims, 2013). In this paper, socioecological factors are part of the validity argument. Recognizing them is essential within assessment design, teaching and learning strategies, and NLP development (Baker et al., 2021, 2025). Our goal is to propose a new formative assessment framework that integrates NLP to explore open-ended responses and identify culturally relevant content. This type of assessment allows students to draw on their background knowledge and full linguistic repertoire to demonstrate understanding while also providing teachers key information to enhance instruction.

Open-Ended Responses Capture Socioecological Knowledge

Understanding the role of culture, diversity, and context in assessment is relatively new, highlighting the importance of such factors and how they shape how students learn, think, and engage with assessments (e.g., del Rosario Basterra et al., 2011; Bennett et al., 2025). One way to incorporate this information is through the use of open-ended responses. Open-ended items or tasks require students to communicate their own understanding of concepts, rather than selecting from a series of options (e.g., multiple-choice items). These responses are subsequently scored by a human or an automated system using a defined rubric (Haladyna & Rodriguez, 2013).

Compared to multiple-choice items, open-ended formats are more suitable for assessing complex skills, capturing deeper conceptual understanding, and can provide richer feedback, and strong alignment with contemporary learning standards (real-world, standards-driven tasks such as those from NGSS; Haladyna & Rodriguez, 2013; Livingston, 2009; Noble et al., 2023). Recent advances in NLP have made automated scoring of open-ended responses increasingly possible (e.g., Baker, 2020–2025; Morris et al., 2025). However, open-ended response formats still face important challenges and questions with respect to efficiency in development and administration, scoring reliability, fairness, construct representation and cognitive demands across diverse populations (Haladyna & Rodriguez, 2013; Morris et al., 2025; Noble et al., 2023). This paper explores the potential of NLP to capture sociocultural influences in student open-ended responses to science and literacy vocabulary questions.

6. Science and Literacy

Literacy is an essential skill that is a focus across subjects, but it has received new emphasis in science within the last decade (O. Lee & Grapin, 2024; National Research Council (U.S.) et al., 2012). Science literacy encompasses a variety of skills within the field, including asking questions, reading and interpreting data, and using content-specific terminology to effectively communicate ideas both orally and in writing (Holbrook & Rannikmae, 2009; Kowalkowski et al., 2025; NGSS Lead States, 2013). This literacy is essential to understand our position within the world, collaborate to solve today’s problems, and promote social innovation (DeBoer, 1991)

Recognizing the need for increased science literacy in our communities, many countries have revisited the way they approach science education to call for more focus on the practice of science rather than rote memorization of content (NGSS Lead States, 2013). Students should not just understand the ways others have engaged in scientific inquiry or be able to recall facts, but should instead engage in science themselves. This includes an increased wave of attention to the ways that language plays a role in science education. As Yore et al. (2003) observe,

Language is an integral part of science and science literacy—language is a means to doing science and to constructing science understandings; language is also an end in that it is used to communicate about inquiries, procedures, and science understandings to other people so that they can make informed decisions and take informed actions.(p. 691)

While this change in focus may cause instructional shifts for all students, one important group to consider are multilingual learners. Multilingual students have a wealth of science funds of knowledge yet frequently face challenges such as curriculum that does not align to community practices and language of instruction. With these challenges, amongst other systemic factors such as deficit language ideologies and tracking, Latinx and multilingual students continue to be underrepresented in many STEM classes and careers (Callahan & Shifrer, 2016; National Science Board & National Science Foundation, 2023). We focus on this group within our work, recognizing the potential of formative, open-ended NLP assessments to capture these students’ diverse background knowledge (Noble et al., 2020).

7. Context & Study Background

Today, one in 10 students in United States schools speak a language other than English at home (National Center for Education Statistics, 2024). While these students come from a variety of cultural and linguistic backgrounds, the largest portion identify as Latinx (78%) and the most prevalent home language is Spanish (76%; National Center for Education Statistics, 2024). However, this population tends to perform lower on standardized assessments, including within science and literacy (Abedi, 2002; Callahan & Shifrer, 2016). To help shrink this gap, instruction that takes into account the diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds is an important avenue. Addressing this issue, two IES funded projects worked to integrate NLP into science curriculum and assessments to provide formative feedback to enhance instruction.

The English Learner Vocabulary Acquisition (ELVA) Project (R305A140471) developed an intelligent tutoring system (ITS) that supported vocabulary knowledge, text comprehension and English language proficiency of Spanish-speaking English Learners (Baker et al., 2021). As a part of the tutoring system, students orally responded to prompts to define key vocabulary terms in science and social studies. This is unique in that the program allows for open-ended oral responses. Researchers found that use of the ITS significantly improved students’ vocabulary knowledge and that students and teachers viewed the system as fun and easy to navigate (Baker et al., 2021).

While ELVA was an intelligent tutoring system that focused on an intervention to build student vocabulary in science and social studies, the Measuring the Language and Vocabulary Acquisition in Science of Latinx Students (MELVA-S) Project (R305A200521) aimed to create a formative assessment that could help support students’ science vocabulary growth. It focused on the potential of NLP to score and provide information about students’ vocabulary knowledge for teachers. Students responded to definition tasks (i.e., What is evaporation?) and sentence tasks (i.e., Now, based on the picture you see, use evaporation in a sentence). We developed an NLP algorithm that was comparable in scoring with human raters to provide quick and cost-efficient classroom data that teachers could use to progress monitor students and provide differentiated support in a Response to Intervention (RTI) framework. RTI is a framework used by schools to assess students, progress monitor those who are in need of additional support, provide evidence-based instruction that supports student success (Esparza Brown & Sanford, 2011). We used the data from ELVA to develop and test the algorithm in MELVA-S.

The current work summarizes findings across both projects related to the potential of AI and new technologies in science and literacy instruction, specifically with regards to using sociocultural background knowledge in assessment and instruction. As researchers reviewed project data, it became clear that students were drawing on their linguistic and cultural assets to make sense of content and terminology. While the existing paradigm in assessment calls for un-biased testing that often seeks to exclude sociocultural influences in responses (American Educational Research Association et al., 2014; Noble et al., 2020), there is an increasing call within the testing community to develop more culturally responsive approaches to acknowledge the diverse ways in which students learn (C. D. Lee, 2025). We recognize that NLP offers a new opportunity to shift and apply at a large scale how we use assessments to better understand what students know about a specific content, how they understand content, and what they use to make sense of content.

To accomplish this, we decided to look deeper into student responses to our science items by using Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory and a rubric that can eventually be integrated into our original NLP to improve our automated scoring system. Specifically, our research questions are:

- In what ways can NLP inform the assessment and learning of science vocabulary among multilingual and multicultural learners?

- What are the socioecological factors that influence student responses? And how can they provide additional information about student knowledge and interpretation of the item?

- What are the challenges of using NLP to incorporate a socioecological perspective in assessing and teaching science concepts?

We present here a new way of thinking about assessments that takes into account student’s full repertoire of knowledge. This section of our project is still under development and represents the challenges as well as the potential of automated scoring to combine all sociocultural, linguistic, scientific, and vocabulary knowledge of multilingual students.

8. Method

8.1. Participants

As shown in Table 1, both ELVA and MELVA-S projects recruited schools serving diverse student populations in 2nd and 3rd grade (typically, 7–9 years old). Across the two projects, this included 25 public and charter schools across the southern United States, representing urban, suburban, and rural communities. More specifically, data for ELVA were collected over a one-year period (2017–2018) across 7 schools through a cluster randomized design (Baker et al., 2021). The MELVA-S project involved a four-year data collection effort across six Texas school districts and 34 schools with the majority being Latino students. For the purposes of the current study, we analyzed data from participants enrolled during the first two years of MELVA-S (2022–2023, 2023–2024).

Table 1.

Student Demographics.

8.2. NLP Vocabulary Scoring

To build an NLP model that could provide formative data about students’ depth of vocabulary knowledge, student responses to definition and sentence tasks were automatically transcribed using Amazon Web Services (AWS) and reviewed by human coders. These coders both provided feedback on the transcription and used a rubric to score students’ open-ended responses from 0–2 (Appendix A). In both definition and sentence tasks, a score of 0 indicated that students had no or little background knowledge about a word while a score of 2 indicated that they were proficient with the terminology. Human coders received multiple rounds of training and reviewed responses together until they achieved an inter-rater reliability with a quadratic weighted kappa (QWK) value greater than 0.9 for definition tasks, and about 0.8 for sentence tasks (Wu et al., 2023). Raw scores were subsequently scaled using the Partial Credit Model (PCM; Masters, 1982) to link student performance across forms.

To train the model, the algorithm applied what it had learned from the human-scored training set to score new responses. Specifically, fine tuning of a pre-trained language model was carried out on the scoring task. In this way, a foundational language model was leveraged for its general ability to process language and then adapted to better mirror the scoring from human coders. Reliability between human raters and the model, calculated using QWK, reached up to 0.78 for definition tasks and 0.68 for sentence tasks, which is considered substantial agreement (Doewes et al., 2023). To develop the algorithm we used data from ELVA and MELVA-S.

8.3. Socioecological Coding

Socioecological coding for this study occurred in two iterations across the ELVA and MELVA-S projects. During ELVA, the coding rubric was developed, and the data were reviewed by a team of three coders: two graduate students and one postdoctoral researcher. In MELVA-S, the coding rubric was reviewed and refined by a team consisting of three undergraduate researchers, one graduate researcher, and one postdoctoral researcher. Table 2 presents a summary of codes identified across projects.

Table 2.

Socioecological Codes.

The coders brought diverse experiences working with varied populations, including backgrounds such as growing up as transnational citizens, learning a second language, and/or serving as bilingual educators. In both projects, coders received training on the use of the rubric and coded a sample of responses to obtain an 85% or above coding agreement for the sentence production task, before reviewing the rest of the codes independently. Across all responses there was 85.75% coding agreement for ELVA and 97.07% for MELVA-S. Mismatch in coding (i.e., 14.25% for ELVA and 2.93% for MELVA-S) was resolved through consensus by two researchers.

Codes remained relatively stable from the ELVA to MELVA-S, highlighting that the same socioecological factors are influencing students’ understanding of content across years and projects. This suggests that regardless of the context (i.e., the assessment), background information about language and content are essential to measure student understanding.

8.4. Data Analysis

Both ELVA and MELVA-S formative assessments of student science knowledge allowed students to orally respond in English and/or Spanish. These data were then transcribed using automatic speech recognition [ASR], which resulted in transcripts that could be textually analyzed using NLP. Student responses led researchers to start exploring at a deeper level what background knowledge (e.g., individual experiences, family, community and social media) students used to respond to science items. These components of background knowledge are not mutually exclusive and often are referenced in combination throughout students’ responses. This knowledge is important because (a) it allows all students to draw from their experiences and environment, (b) it allows teachers to have a better understanding of how students understand and use words. This understanding would not be possible in a receptive multiple-choice assessment or an assessment where words that could be biased are removed from the assessment.

9. Results

Summarizing results across both projects, we report findings related to our two research questions below. We begin by highlighting both the benefits of NLP to capture students’ science vocabulary knowledge through formative assessment, as well as challenges that emerged throughout our work. Second, we explore ways in which socioecological data appeared within students’ data. Finally, we zoom into the potential of NLP models to incorporate a socioecological framework, and how this information could inform both content and language instruction.

9.1. Research Question 1: In What Ways Can NLP Inform the Assessment and Learning of Science Vocabulary Among Multilingual and Multicultural Learners?

9.1.1. NLP Accurately Score Students’ Open-Ended Responses

The primary way that NLP was used in ELVA and MELVA-S was to provide transcriptions of student utterances and automatic scoring of what students said. As the NLP model was trained with responses from human raters using a rubric, NLP was able to accurately apply what it had learned to score students’ responses from 0–2 (Wu et al., 2023). The rubric included recognizing alterative definitions, whether students were using examples and details, and accuracy of use. The NLP model had a high level of agreement with human raters, indicating that it is able to accurately score students’ open-ended responses. However, it is notable that human-human agreement is still higher than human-machine agreement. A significant reason for this gap is the quality of ASR used by the model, which struggled to reliably transcribe student responses in a classroom setting.

Through the NLP model, feedback on students’ depth of vocabulary knowledge could be quickly generated and shared with teachers. When referring to the rubric, this feedback could give information about which words needed to be reviewed most as a class, and which students might benefit from more structured literacy/vocabulary support in science through a RTI framework. As one teacher commented when reviewing student data:

“Being able to see what is the vocabulary that the students are having trouble with is great information to have and help us to design teaching strategies.”

As this teacher indicates, NLP data about both individual and class-wide knowledge of science vocabulary allow teachers to meet students where they are. Incorporating these data into instruction, teachers can then support science literacy through both language and content support.

9.1.2. Challenges Capturing Student Speech

For both projects, students’ oral and open-ended responses were recorded before being transcribed by an ASR system. Yet, the ASR frequently had trouble fully capturing students’ full oral responses for sentence or definition tasks. Human-scorers listened to a percentage of responses to accurately write down the transcription for data analysis. Therefore, both anecdotal evidence from human-scores who often corrected these transcriptions, as well as an analysis between ASR and human interpretation, highlight that ASR struggles to accurately capture students’ responses. The reasoning for this struggle comes from three sources: Students are responding to prompts in settings with a variety of background noises (i.e., peers talking, teachers supporting); have unique speech characteristics (i.e., fillers, singing, phrasing); and differ dramatically from the adult speech that most ASR systems are trained.

Table 3 provides an example of the ASR system transcription error vs. a human scorer correction. The discrepancies between these transcriptions are substantial, which could lead to errors in the NLP model’s scoring. It is notable that human agreement on transcripts was also challenging, with raters dictating different parts of speech differently. Analysis of the transcriptions reveals that approximately 38% of the words from the ASR are transcribed incorrectly. Practically, this means the NLP scoring model is tasked with using noisy input transcriptions and mapping to the sentence and definition tasks.

Table 3.

Comparison of ASR and Human Scoring Outputs for a Student Response.

Discrepancies are exacerbated for multilingual students. Transcriptions from second language learners and different languages have a lower agreement between raters and ASR systems (Cumbal et al., 2024; Kuhn et al., 2024). This is both due to smaller sizes of training materials, differences in vocabulary and pronunciation, and differences across speakers. This can lead to inaccurate transcriptions, producing unreliable inputs for NLP programs to score. This may further be complicated by translanguaging, or the use of multiple languages to communicate ideas, although research highlights it as an important strategy to fully understand what students know (García & Wei, 2014).

In summary, the transcription system we used still appeared to have difficulty recognizing student responses. However, the scoring system was able to score accurately student responses. This system, however, did not include the sociocultural scoring of student responses yet.

9.2. Research Question 2: What Are the Socioecological Factors That Influence Student Responses?

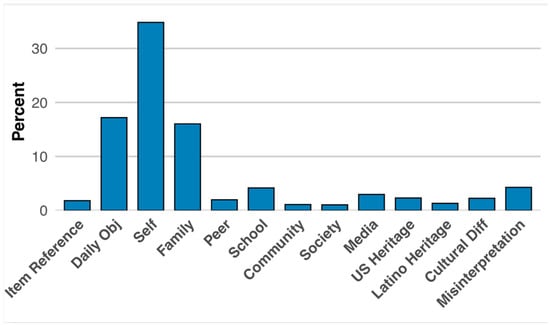

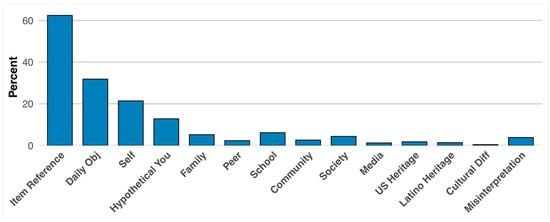

To respond to this question we will use the coding and scoring from our human scorers. Findings indicated clearly that culture and language need to be taken into account when examining student expressive language. Culture and language, however, are very large concepts that need to be deconstructed. Based on human coding shown in Table 2, we coded responses into 10 categories in the socioecological rubric, with approximately 63.7% in English and 36.3% in Spanish in the ELVA project. Furthermore, 55.9% of student responses contained at least one socioecological component specified in the rubric for the ELVA measure and 66.5% for the MELVA-S measure. Figure 2 shows the percentage of students referencing this information in the ELVA project, while Figure 3 shows the frequency that socioecological factors were referenced within MELVA-S.

Figure 2.

ELVA Socioecological Factors in Student’s Science Responses.

Figure 3.

MELVA-S Socioecological Factors in Student’s Science Responses.

As we can see, the presence of socioecological factors remained strong across projects, indicating that these constructs are what students draw on to inform their learning, regardless of context. As they were asked to use terminology in their sentences, they frequently referenced themselves, their family, their community, familiar objects or activities, and other socioecological factors to convey their understanding. To exemplify this, we include 3 examples of how students described a picture for the word support in MELVA-S in Table 4.

Table 4.

Examples of Student Responses to the Target Word “Support” in the MELVA-S Assessment.

While all three students saw the same image (a girl supporting her work on the board, aimed to guide students to use support to illustrate the definition to provide proof or facts for what you say), students often continued to try to use support in the more common contexts such as to provide emotional care and assistance and to physically hold something in place. This knowledge was also frequently tied to students’ home lives—as we see both Student 1 and 3 referencing family to illustrate the word. Using the sentence rubric (Appendix A), Student 2 would get full credit for this response (a score of 2) because although the student is using an alternative definition, they are still using it in the context of the picture. However, Students 1 and 3 would only get partial credit for their responses (a score of 1). While they correctly use an alternative definition, they did not link their sentences to describe the picture. These scores provide useful information for teachers; however, they also omit key socioecological information that could be helpful to enhance instruction.

Using ELVA data, we also examined student responses conditioning on ability. Students scoring one standard deviation above the mean were significantly more likely to use a school context (23.4%) than those one standard deviation below the mean (7.5%), p < 0.05 level. Similarly, statistically significant differences were found in references to family, with a higher proportion occurring in Spanish (24.7%) compared to English (13.3%).

In summary, the factors identified in this study and used to construct the socioecological rubric appear to be relevant and useful to better understand how students are answering science questions, and most importantly, how they are making sense of these words and what they are learning. We address these findings in more detail in the implications section.

9.3. Research Question 3: How Can NLPs Be Leveraged to Capture Socioecological Details from Student Open-Ended Responses?

As our findings for RQ1 indicate, NLPs trained on rubrics can identify key features of students’ responses (i.e., are they providing examples, using details, etc.). With this logic, NLPs then should also have the ability to use a socioecological rubric to capture students’ linguistic and cultural knowledge that are embedded within open-ended responses. While this rubric has been leveraged by human coders to find socioecological factors within student’s responses with success, it now needs to be used to train a new NLP algorithm. Through this process, NLP will be able to provide reports about how students are understanding these concepts at a scalable level. For example, reviewing this information revealed key instructional insights for a variety of terms, which we categorized into auditory data, cross-linguistic data, and cultural context.

9.3.1. Auditory Information

By recognizing whether students were using target words, we noted that several students were misinterpreting key words for other similar-sounding proxies. For example, when one student heard the word influence, they provided the following definition: “Influence means when somebody is sick and a kid touches him and gets sick.” [influenza]. As both influence and influenza have several similar phonological features, a closer analysis of the words and how they differ could benefit students’ understanding. Other similar examples were when students interpreted erupt as interrupt and inventor as adventure.

9.3.2. Cross-Linguistic Transfer

Multilingual students often also pulled on their linguistic repertoires in their first language to understand key terminology in English. For example, in an ELVA response, one student used the word lawyer (abogado in Spanish) in the following sentence: “Estoy abogado porque tome mucha agua. [I’m a lawyer because I drink a lot of water].” In this sentence, the rater needed knowledge of Spanish to recognize that they were switching abogado for ahogado, which means drowning or choking. In another example with MELVA-S, students frequently applied Spanish definitions for words (i.e., masa [dough] for masa [mass] and patrón [boss] for patrón [pattern]. As these examples show, definitions of words do not always exactly translate across languages. Additionally, it is important to be aware of how students might be applying their knowledge of their home languages’ phonology and vocabulary to make sense of new words. By recognizing this, the NLP can provide teachers with cross-linguistic knowledge to enhance instruction.

Allowing children to respond in their language of preference gives them autonomy and control, enabling them to draw on their existing knowledge during assessment. This approach also provides valuable insights into cross-linguistic transfer and how students interpret words. For example, some responses reflect phonological similarity rather than semantic accuracy, such as confusing ahogado (drowned) with abogado (lawyer). While incorrect, these instances are informative because they reveal how students rely on the closest-sounding word to construct meaning. Returning to our theoretical framework, children’s socioecological responses are influenced by factors at the exosystem and macrosystem levels. This giving all educators and researchers further understanding of how cultural ideologies such as students background, cultural content and lived experience play a critical role on how they interpret information and bring it to assessments.

9.3.3. Cultural Context

In addition to these examples, NLP could recognize which contextual factors (i.e., family, peers, self, community) are shaping students’ understanding of words. For example, in ELVA coders realized that several students were defining inventor as a person who makes up stories (mi mamá inventa), which is a meaning that is unique in Spanish. Recognizing cultural context, teachers could then use this information to plan a lesson on metalinguistic awareness and compare use of the word across languages. In MELVA-S, coders found a unique pattern in how students were defining and using temperature. As these data were collected in 2022–2023, many students responded to definitions of temperature with answers similar to this: “The temperature is like when you sit and you use a thermometer to put in your mouth.” When reviewing the socioecological influences on these answers, we realized that students were frequently confusing temperature with being sick. This is likely a result of the context they had been living through, with a world-wide pandemic. Teachers could use this data to enhance instruction of the term, discussing how temperature is used in a variety of contexts.

A report generated with NLP findings could highlight these elements of students’ responses. As a result, rather than listening to 20 students use vocabulary in short-answer responses and pulling these data themselves, teachers could save time and use the NLP data to address misconceptions and build on prior knowledge within instruction more efficiently. Less time will be spent assessing, and more time can be spent teaching.

10. Discussion

Findings across both projects demonstrate that NLP can be a powerful tool to enhance formative assessment, especially when combined with a socioecological framework. We observed that students consistently drew on background knowledge related to personal, family, and community experiences to make sense of science terms and concepts. By drawing on both Bronfenbrenner’s (2005) ecological systems theory and Vygotsky’s (1978) sociocultural theory, our socioecological framework shows that science and language is embedded within systems and that our interaction with the world around us informs the way we learn. Designing new formative assessments from this lens will allow us to identify key sources of student knowledge, which have traditionally been ignored in assessments, to enhance instruction.

However, while NLP provides new opportunities, it also presents challenges—especially when working with a multilingual student population. ASR systems struggled to accurately transcribe student speech, particularly among multilingual learners, which affected scoring reliability. This highlights the need for continued refinement of NLP tools and the importance of human oversight in educational AI applications. Nevertheless, with continued attention to socioecological elements and technological advancements, we see tools such as NLP as essential to reimagining our instructional practices.

10.1. Implications for Practice

By situating NLP within an ecological framework, we propose a shift in how formative assessments are designed, interpreted, and acted upon—one that centers student context, language, and lived experience as assets that can be leveraged to support learning for all students.

10.1.1. NLP Provides New Assessment Opportunities

NLP models can provide quick and accurate information about students’ responses to open-ended tasks to teachers about their students’ progress (Hutson & Plate, 2023). This is especially promising for formative assessments, as it allows students to expand on their knowledge in ways that traditional assessments might not capture. While a multiple-choice quiz might provide a quick check on students’ understanding, encouraging them to explain concepts verbally tests new skills and aligns more with shifts in science and literacy practices (NGSS Lead States, 2013).

Within a formative assessment framework, these data can then be used to modify instruction. By identifying key terminology and students that might need extra instructional support, teachers can then make instructional decisions to ensure all students meet learning targets. For example, for key words that are identified as challenging, they can provide whole-class instruction with strategies such as providing clear student-friendly definitions, exploring multiple examples, and having opportunities to use vocabulary in new ways (Baker et al., 2015; Kowalkowski et al., 2025). For specific students who need support, the teacher could provide targeted intervention groups with more intensive vocabulary instruction. By addressing vocabulary using NLP, these teachers are also supporting students’ science content learning and language within their classroom (Baker et al., 2025). With this information, teachers will be able to address potential disparities more quickly and equitably, enhancing learning for all.

10.1.2. Recognizing Culture and Language in Assessment

Students consistently drew upon their linguistic and cultural background knowledge to make sense of new terminology. Traditional assessments do not pay attention to these type of data, which omits a huge wealth of information that can be used to support students’ growth. If teachers dismiss students’ definitions of masa [mass] as dough, even though it is an accurate definition in their home language, they are also missing the opportunity to lift up students’ experiences and explore cross-linguistic connections together. With this knowledge, teachers can integrate translanguaging pedagogies that recognize students’ full linguistic repertoires and build on their background knowledge to explore terms and concepts in different contexts (García & Wei, 2014).

10.1.3. The Importance of the Teacher in AI Education Spaces

While AI such as NLP offers new and exciting opportunities for assessments and education, the continued importance of the teacher cannot be overstated. In formative assessments, such as MELVA-S, data should be used by educators to inform instruction. It is not a static data point, but a place to begin building language and content knowledge. Ensuring that socioecological data are also integrated to support instruction also falls on instructors. However, NLP can provide educators with the opportunity to spend less time grading, which can make space for more time teaching.

10.2. Limitations

While NLP currently provides us with a score that represents students’ depth of knowledge on science vocabulary tasks, more work is needed to expand the algorithm to capture students’ background knowledge. Palma et al. (in preparation) have argued for the utility of the socioecological rubrics mentioned above, providing evidence using ELVA and MELVA-S data that students are using prior experiences to make sense of science content. Now, work needs to be done to integrate these rubrics within the NLP programs and design a way to meaningfully communicate results for teachers.

The automated transcription system we have developed does still not capture students’ responses with high accuracy. However, advances in speech recognition systems will only increase and become more accurate. Thus, the continuation of this work is essential to capture student responses accurately helping them and their teachers use the information to improve their understanding of science concepts.

11. Future Directions and Conclusions

Integrating the linguistic and cultural experiences behind student knowledge is an evidence-based practice to enhance students’ performance across content areas. By providing snapshots that not only capture depth of knowledge for vocabulary, but also sources of prior knowledge, NLP programs can build new systems to support literacy. Through these technological enhancements, teachers will both have more instructional time and new data points to support learning across content areas. This exploratory study provides new directions in a currently unexplored area, aiming to incorporate assets that multilingual students bring into assessment and learning.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.P., D.L.B., H.P.K. and C.B.H.; Methodology, J.P., Z.W. and E.C.L.; Software, Z.W. and E.C.L.; Validation, J.P. and C.B.H.; Formal Analysis, J.P.; Investigation, H.P.K.; Resources, D.L.B.; Data Curation, J.P.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, H.P.K. and C.B.H.; Writing—Review & Editing, H.P.K., C.B.H. and D.L.B.; Visualization, C.B.H., H.P.K. and J.P.; Supervision, H.P.K., D.L.B. and J.P.; Project Administration, H.P.K. and D.L.B.; Funding Acquisition, D.L.B. and E.C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Institute of Education Sciences (IES) grant numbers R305A20052 and R305A140471 to Dr. Doris Luft Baker, University of Texas at Austin. The views expressed within this article are those of the authors and do not represent the views of the U.S. Department of Education or the Institute of Education Sciences. The article processing charge (APC) was funded by Texas A&M University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the University of Texas at Austin Institutional Review Board (protocol code STUDY00000152 and date of approval: 11 May 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because of the ongoing nature of this study. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

MELVA-S Definition and Sentence Rubrics

Responses are scored on a scale from 0 to 2.

| Definitions | |

| Score | Score Criteria |

| 0 | Needs support

|

Examples:

| |

| 1 | Developing

|

Examples:

| |

| 2 | Mastery

|

Examples:

| |

| Sentences | |

| Score | Score Criteria |

| 0 | Needs support

|

Examples:

| |

| 1 | Developing

|

Examples:

| |

| 2 | Mastery

|

Examples:

| |

References

- Abedi, J. (2002). Standardized achievement tests and English language learners: Psychometrics issues. Educational Assessment, 8(3), 231–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, National Council on Measurement in Education & Joint Committee on Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing (U.S.). (2014). Standards for educational and psychological testing. AERA. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, D. L. (2020–2025). Measuring the English language vocabulary acquisition of Latinx bilingual students (Project No. R305A200521). [Grant]. Institute of Education Sciences.

- Baker, D. L., Ma, H., Polanco, P., Conry, J. M., Kamata, A., Al Otaiba, S., Ward, W., & Cole, R. (2021). Development and promise of a vocabulary intelligent tutoring system for second-grade latinx English learners. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 53(2), 223–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D. L., Moradibavi, S., Liu, Y., Huang, Y., & Sha, H. (2025). Effects of interventions on science vocabulary and content knowledge: A meta-analysis. Research in Science Education, 55, 1517–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D. L., Santoro, L., Ware, S., Cuéllar, D., Oldham, A., Cuticelli, M., Coyne, M. D., Loftus-Rattan, S., & McCoach, B. (2015). Understanding and implementing the common core vocabulary standards in kindergarten. Teaching Exceptional Children, 47(5), 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, R. E., Darling-Hammond, L., & Badrinarayan, A. (Eds.). (2025). Socioculturally responsive assessment: Implications for theory, measurement, and systems-level policy (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botelho, A., Baral, S., Erickson, J. A., Benachamardi, P., & Heffernan, N. T. (2023). Leveraging natural language processing to support automated assessment and feedback for student open responses in mathematics. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 39(3), 823–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (2005). Ecological systems theory (1992). In U. Bronfenbrenner (Ed.), Making human beings human: Bioecological perspectives on human development (pp. 106–173). Sage Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Caldas, S. J. (2013). Assessment of academic performance: The impact of No Child Left Behind policies on bilingual education: A ten year retrospective. In V. C. Mueller Gathercole (Ed.), Issues in the assessment of bilinguals (pp. 205–231). De Gruyter. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, R. M., & Shifrer, D. (2016). Equitable access for secondary English learner students: Course taking as evidence of EL program effectiveness. Educational Administration Quarterly, 52(3), 463–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumbal, R., Moell, B., Lopes, J., & Engwall, O. (2024). You don’t understand me!: Comparing ASR results for L1 and L2 speakers of Swedish. arXiv, arXiv:2405.13379. [Google Scholar]

- DeBoer, G. E. (1991). A history of ideas in science education: Implications for practice/George E. DeBoer. Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- del Rosario Basterra, M., Trumbull, E., & Solano Flores, G. (2011). Cultural validity in assessment: Addressing linguistic and cultural diversity (E. Trumbull, G. Solano-Flores, & M. del R. Basterra, Eds.; 1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doewes, A., Kurdhi, N., & Saxena, A. (2023). Evaluating quadratic weighted kappa as the standard performance metric for automated essay scoring. In M. Feng, T. Käser, & P. Talukdar (Eds.), Proceedings of the 16th international conference on educational data mining (pp. 103–113). International Educational Data Mining Society (IEDMS). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esparza Brown, J. E., & Sanford, A. K. (2011). RTI for English language learners: Appropriately using screening and progress monitoring tools to improve instructional outcomes. U.S. Department of Education, Office of Special Education Programs, National Center on Response to Intervention.

- García, O., & Wei, L. (2014). Translanguaging: Language, bilingualism and education. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Haladyna, T. M., & Rodriguez, M. C. (2013). Developing and validating test items (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heritage, M. (2007). Formative assessment: What do teachers need to know and do? Phi Delta Kappan, 89(2), 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschberg, J., & Manning, C. D. (2015). Advances in natural language processing. Science, 349(6245), 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, J., & Rannikmae, M. (2009). The meaning of scientific literacy. International Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 4(3), 275–288. [Google Scholar]

- Huddleston, A. P. (2014). Achievement at whose expense? A literature review of test based grade retention policies in US schools. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 22, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutson, J., & Plate, D. (2023). Enhancing institutional assessment and reporting through conversational technologies: Exploring the potential of AI-powered tools and natural language processing. Journal of Artificial Intelligence and Robotics, 1(1), 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalkowski, H., Sha, H., Moradibavi, S., & Luft Baker, D. (2025). Navigating the science education landscape: Teacher beliefs about supporting multilingual students. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, K., Kersken, V., Reuter, B., Egger, N., & Zimmermann, G. (2024). Measuring the accuracy of automatic speech recognition solutions. ACM Transactions on Accessible Computing, 16(4), 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C. D. (2025). Implications of the science of learning and development (SoLD) for assessments in education. In Socioculturally responsive assessment (pp. 29–49). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, O., & Grapin, S. (2024). English language proficiency standards aligned with content standards: How the next generation science standards and WIDA 2020 reflect each other. Science Education, 108(2), 637–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W. (2025). Applying natural language processing adaptive dialogs to promote knowledge integration during instruction. Education Sciences, 15(2), 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, S. A. (2009). Constructed-response test questions: Why we use them. How we score them. Available online: https://www.ets.org/Media/Research/pdf/RD_Connections11.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Lottridge, S., Ormerod, C., & Jafari, A. (2023). Psychometric considerations when using deep learning for automated scoring. In M. von Davier, & V. Yaneva (Eds.), Advancing natural language processing in educational assessment (1st ed., pp. 15–30). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masters, G. N. (1982). A Rasch model for partial credit scoring. Psychometrika, 47(2), 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, W., Holmes, L., Choi, J. S., & Crossley, S. (2025). Automated scoring of constructed response items in math assessment using large language models. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 35(2), 559–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Education Statistics. (2024). English learners in public schools. Condition of education. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/cgf (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- National Research Council (U.S.), Committee on a Conceptual Framework for New K-12 Science Education Standards, B. on S. E., National Research Council (U.S.), Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education & National Research Council of the National Academies. (2012). A framework for K-12 science education: Practices, crosscutting concepts, and core ideas (1st ed.). National Academies Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Science Board & National Science Foundation. (2023). Elementary and secondary STEM education. Science and engineering indicators 2024. NSB-2023-31. National Science Board (NSB). Available online: https://ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/nsb202331/ (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- NGSS Lead States. (2013). Next generation science standards: For states, by states. The National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- Noble, T., Sireci, S. G., Wells, C. S., Kachchaf, R. R., Rosebery, A. S., & Wang, Y. C. (2020). Targeted linguistic simplification of science test items for English learners. American Educational Research Journal, 57(5), 0002831220905562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, T., Wells, C. S., & Rosebery, A. S. (2023). English learners and constructed-response science test items challenges and opportunities. Educational Assessment, 28(4), 246–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Ruiz, J., Alvarez-Delgado, A., & Caratozzolo, P. (2021, December 15–17). Use of natural language processing (NLP) tools to assess digital literacy skills. 2021 Machine Learning-Driven Digital Technologies for Educational Innovation Workshop (pp. 1–8), Monterrey, Mexico. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, D. P. (2013). Can failure succeed? Using racial subgroup rules to analyze the effect of school accountability failure on student performance. Economics of Education Review, 32(1), 262–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somers, R., Cunningham-Nelson, S., & Boles, W. (2021). Applying natural language processing to automatically assess student conceptual understanding from textual responses. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 37(5), 98–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez, E. (2020). “Estoy explorando science”: Emergent bilingual students problematizing electrical phenomena through translanguaging. Science Education, 104(5), 791–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, B., Macgilchrist, F., & Potter, J. (2021). COVID-19 controversies and critical research in digital education. Learning, Media and Technology, 46(2), 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z., Larson, E., Sano, M., Baker, D., Gage, N., & Kamata, A. (2023). Towards scalable vocabulary acquisition assessment with BERT. In Proceedings of the tenth ACM conference on learning@ Scale (pp. 272–276). Association for Computing Machinery. [Google Scholar]

- Yore, L., Bisanz, G. L., & Hand, B. M. (2003). Examining the literacy component of science literacy: 25 years of language arts and science research. International Journal of Science Education, 25(6), 689–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).