Abstract

Out-of-school time (OST) STEM programs are well-positioned to strengthen family engagement, yet practical, theory-aligned tools remain limited. This early-stage mixed-methods study tests parent/caregiver (P/C) and staff (S) surveys based on Clover for Families developmental theory expressed through the CARE framework: Connect (welcoming climate, clear communication), Act (hands-on participation, at-home supports), Reflect (shared meaning-making, feedback), and Empower (family voice, decision-making). Nine OST STEM programs (eight U.S. states) co-designed/piloted CARE plans, activities, and surveys over six months. Quantitative data included baseline experiences (CARE practice frequency; n = 67 P/C, 42 S across nine programs), program-end reflection (retrospective perceptions of change; n = 26 P/C, 29 S), and forced-ranking (most/least important domains; n = 67 P/C, 42 S). Qualitative data from meetings, open responses, and interviews were analyzed to contextualize quantitative findings, which included strong internal consistency (P/C α = 0.83–0.95; S α = 0.77–0.95) and large retrospective gains in both groups across domains. Forced-ranking elevated Connect and Act over Reflect and Empower, highlighting a need to scaffold family involvement. Staff described CARE as useful and actionable. Findings show that CARE supports measurement and continuous improvement of STEM family engagement. Future work should test large-sample validity, link results to observed practice and youth outcomes, and refine Empowerment-related items for everyday agency.

1. Introduction

Across the United States, out-of-school-time (OST) science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) programs play a pivotal role in shaping children’s interests, skills, and confidence in STEM fields (Afterschool Alliance, 2015). These programs—including afterschool clubs, community-based initiatives, science centers, and summer camps—offer STEM learning experiences that complement and extend school-day instruction through hands-on, collaborative, inquiry-based activities (National Research Council [NRC], 2009, 2015). Yet one of the most powerful and underutilized drivers of STEM engagement lies outside program walls: families. Decades of research show that when parents and caregivers are involved in their children’s learning, youth exhibit higher academic achievement, stronger motivation, and more sustained interest in STEM pathways (Dabney et al., 2016; Dou et al., 2019, 2025; Perera, 2014; Shumow & Schmidt, 2014).

Despite this evidence, systematic approaches for supporting and measuring family engagement in STEM remain scarce, especially within OST programs that serve diverse communities (Traphagen et al., 2020). While national initiatives—from the U.S. Department of Education’s Family Engagement Learning Series (2023) to Cambiar Education’s Thrive Grants (2023)—reflect growing recognition that family engagement is essential for equitable participation in STEM learning and career pathways, the field continues to lack theory-based, context-specific evaluation tools. Most existing frameworks were developed in formal school settings (e.g., Epstein, 2008; Ishimaru et al., 2019; Mapp & Kuttner, 2013) and rarely account for the relational and community-centered features that define OST STEM environments (Rosenberg et al., 2014). As a result, there are few methods by which practitioners can assess their family-engagement capacity, monitor progress, or understand families’ perspectives on meaningful engagement in STEM.

The present study addresses this gap with two linked aims: to establish reliable, theory-aligned measurement tools for assessing family engagement in STEM, and to demonstrate how data from these tools function as catalysts for reflection and improvement of the family engagement practices they measure. Both aims are grounded in Clover for Families, a developmental theory of learning and resilience used to guide family engagement in STEM that we operationalize through CARE (Connect, Act, Reflect, Empower). First, we develop and provide initial reliability and validity evidence for a set of CARE surveys for parents/caregivers and staff. Second, we examine how data from these surveys, when embedded in a Community of Practice (CoP), can help OST STEM programs reflect on families’ experiences, identify needs, and strengthen equitable family-educator partnerships. This study shows that CARE surveys are more than measurement tools; they are vehicles for collaborative reflection and continuous improvement.

1.1. From Theory to Practice: The Clover Model and CARE Framework

Beginning in 2020, our research team partnered with OST STEM leaders and practitioners to co-develop a common approach for strengthening and assessing family engagement (Allen & Noam, 2021a, 2021b, 2023). This work is grounded in the research-based Developmental Domain and Process Theory (DDPT), also known as the Clover Model in educational practice (Noam & Triggs, 2018). Clover conceptualizes learning and resilience as the dynamic interplay of four domains: (1) Active Engagement (the physical self: physical connectivity between the self and the world), (2) Assertiveness (the volitional self: using voice and self-control to negotiate rules, roles, and boundaries), (3) Belonging (the relational self: positive relationships, empathy, and support), and (4) Reflection (the cognitive self: using experience, emotions and thoughts to create identity). Together, these domains describe how individuals learn, adapt, and thrive across time and settings (Noam & Triggs, 2018). Clover has informed several validated tools used nationally to assess and strengthen learning and resilience, including youth and educator measures of social-emotional resilience (Malti et al., 2018; Allen et al., 2022) and observation systems such as the Dimensions of Success (DoS) for OST STEM (Shah et al., 2018; Andrews et al., 2023). These tools translate Clover’s developmental principles into a shared language for defining and strengthening both resiliency skills in individuals and the quality of OST STEM learning environments (Andrews et al., 2023). With over a decade of national use, DoS has become a widely adopted framework for guiding professional learning and aligning research, practice, and policy across the STEM education ecosystem (Andrews et al., 2023).

Building on this lineage, the current work extends Clover’s developmental logic and DoS’s systems-based, continuous-improvement approach to the domain of family engagement—recognizing families as integral partners in the broader STEM ecosystem (Murphy, 2020). Clover and DoS are primarily used to understand individual youth development and educator-youth interactions. Family engagement, by contrast, is a collective, relational, and context-specific process. Extending Clover to this domain required reframing developmental theory around parents/caregivers’ roles, needs, and interactions with their children and the programs their children attend, rather than simply applying youth- or educator-focused constructs to a new population. For this reason, we adapted Clover to the family context through “Clover for Families,” which identifies practices that strengthen family engagement in OST STEM within and between families and organizations.

Clover for Families was created through decades of empirical and theoretical scholarship in family engagement and family–school partnerships, expert consultation with family engagement leaders and OST STEM practitioners, and iterative co-design with practitioners to ensure contextual, cultural, and practical fit (Allen & Noam, 2021a, 2021b, 2023). This process identified the ideas and practices most critical for strengthening family engagement at home and in partnership with OST STEM organizations. Subsequent refinement of Clover for Families resulted in the practical heuristic known as CARE—Connect, Act, Reflect, Empower—and an accompanying STEM Family Engagement Planning Tool (see Figure 1, Allen & Noam, 2021b). Although CARE is designed for use by both families and staff, the framework primarily serves as a professional learning and program-design tool for educators. Staff use CARE to shape the structure, communication, and relational practices of family engagement experiences, whether activities occur on site or at home, so that families can meaningfully participate across all four domains.

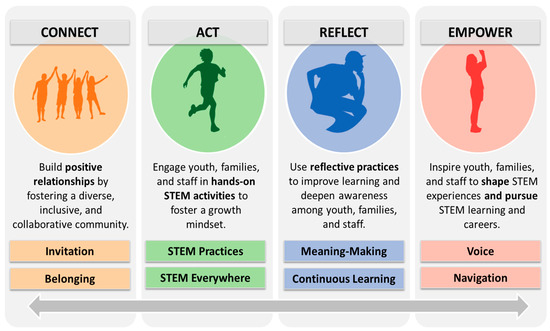

Figure 1.

Clover for Families: Connect, Act, Reflect, and Empower (CARE) practices for family engagement in STEM.

CARE maintains Clover’s holistic view of development but makes it actionable by organizing family engagement practices into four domains that programs can plan for, enact, measure, and reflect on as part of continuous improvement and partnership building with families. These domains include:

- Connect: Emphasizes trust, belonging, and inclusive communication between families, drawing on attachment theory (Ainsworth & Bowlby, 1991), STEM identity frameworks (Carlone & Johnson, 2007), and partnership theories highlighting collaboration between families and educators (Mapp & Kuttner, 2013).

- Act: Focuses on opportunities for families and children to engage together in hands-on STEM, building on experiential learning traditions such as constructionism (Papert, 1980) and Dewey’s (1938, 1959) learning theory, as well as Bandura’s (1977, 1986) social learning theory and Dweck’s (2006) growth-mindset framework.

- Reflect: Highlights shared meaning-making and dialog about STEM learning and futures, aligning with social constructivism (Vygotsky, 1962) and situated learning (Lave & Wenger, 1991), emphasizing shared meaning-making and dialog within and between families and educators (Dou et al., 2019, 2025).

- Empower: Centers family voice, decision-making, and navigation of STEM pathways, drawing on Bandura’s (2001) theory of human agency as well as self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 2000), emphasizing autonomy, advocacy, power sharing, and family voice in decision-making (Ishimaru et al., 2019).

Rather than presenting family engagement as a checklist of tasks, CARE conceptualizes it as a developmental process in which all four domains matter at every stage but are emphasized at different times. Families often are initially engaged through Connect and Act, which establish belonging and participation in STEM, whereas Reflect and Empower typically develop later, as trust grows, confidence increases, and programs scaffold shared meaning-making, voice, and leadership.

1.2. Measuring Family Engagement in Context

Although families are widely recognized as essential partners in children’s STEM learning (Murphy, 2020), systematic approaches to assessing family engagement, particularly within OST STEM programs, remain fragmented and uneven (Gülhan, 2023). This gap matters for both research and practice: without theory-aligned assessments, programs lack tools to understand families’ experiences or use data for continuous improvement. To inform the development of our Clover for Families-aligned CARE surveys and their use within a CoP, we drew on secondary analysis of a large systematic review of STEM and social-emotional development in OST programs (Allen & Noam, 2024, full reference list in Supplement A) as well as broader family engagement scholarship. Across the literature, there emerged several limitations in existing measurement approaches that we endeavored to address.

First, most tools were locally developed, low-burden tools with limited or no evidence of reliability or validity. Data collection typically occurred using a post-only design—an understandable approach given resource constraints but one that limits opportunities to examine change or growth over time. Quantitative measures typically emphasized attendance, communication frequency, or parents’ and caregivers’ attitudes toward STEM (e.g., Edwards et al., 2021), while qualitative approaches more often explored belonging, motivation, and families’ emotional connections to programs and to their children’s learning experiences (e.g., Guillen, 2018).

Second, multi-informant data collection is rare. Few studies collected concurrent data from both parents/caregivers and staff. Youth data often captured perceptions of family influence, such as encouragement or modeling (e.g., Clarke-Midura et al., 2019), whereas parent and caregiver measures tended to combine self-reports of attitudes and practices with proxy reports of their children’s confidence or interest in STEM (e.g., Ruiz-Gallardo et al., 2013). Educator and staff perspectives (e.g., Fleshman, 2012) and observations (e.g., Garip et al., 2021), though less common, provided valuable third-party insights into communication, inclusion, and partnership quality. Collectively, these approaches illustrate meaningful engagement across stakeholders but remain largely unidirectional (e.g., parent → youth or youth → parent) and miss the opportunity to use parallel data to support joint reflection or collaborative decision-making (Ishimaru et al., 2019; Mapp & Kuttner, 2013).

Third, measurement tended to concentrate on Connect- and Act-aligned constructs (e.g., communication, sense of welcome, event attendance, or at-home encouragement), while Reflect (shared meaning-making, dialog) and Empower (leadership, voice, co-design) appeared almost exclusively in qualitative accounts. Thus, much of the existing measurement work captures only the relational and participatory aspects of family engagement, overlooking the reflective and agency-based dimensions essential to deeper STEM learning and equitable family-program partnerships (Ishimaru et al., 2019; Kuttner et al., 2019; Mapp & Bergman, 2021).

Fourth, few tools were grounded in family engagement-specific theory. Studies that referenced theory tended to draw on general education or motivational models—such as activity theory (Hong et al., 2013) and expectancy-value theory (Blanchard et al., 2017)—which primarily explain individual motivations or behaviors rather than the relational, reciprocal, culturally situated, and equity-centered processes that underlie family-educator partnerships (e.g., Ishimaru et al., 2019; Mapp & Kuttner, 2013). A review of 153 empirical studies on family–school partnerships found that nearly half (46.4%) did not identify any family engagement framework (Yamauchi et al., 2017). Among those that did, four theories dominated: Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological model, social capital theory, Epstein’s overlapping spheres, and funds of knowledge. Theories were frequently mentioned only in introductions and not applied to construct development or interpretation.

Contemporary family engagement frameworks illustrate what these measures fail to capture. For example, the Dual Capacity-Building Framework (Mapp & Kuttner, 2013) foregrounds relational trust, collective learning, and shared capacity-building for educators and families. Likewise, equity-centered partnership approaches highlight co-construction, power-sharing, and attention to systemic inequities (Ishimaru et al., 2023). These dimensions are central to equitable family-educator relationships but largely absent from existing quantitative tools in OST STEM.

To address these limitations, the CARE surveys were designed around needs identified in the literature: (1) capture all four theory-informed domains of family engagement: CARE operationalizes the full Clover for Families framework, including Reflect and Empower, which are seldom quantified in existing measures (see Supplement B); (2) support reciprocal, multi-informant understanding: parallel surveys for parents/caregivers and staff provide the missing bi-directional, relational measurement and joint reflection; (3) enable continuous improvement: CARE was designed for use with professional learning communities, supporting iterative reflection and planning that integrate families’ lived experiences with program-level improvement cycles, ensuring that findings are interpreted collaboratively and translated into concrete practice adjustments.

1.3. Present Study

The STEM Family Partnership & Empowerment Project (PEP) was launched in 2024 with philanthropic support to test and refine the CARE framework and survey system in real-world settings. The project established a virtual national learning community of nine OST STEM programs across eight U.S. states, committed to strengthening family–practitioner partnerships through professional learning, coaching, and collaborative planning. Participating programs implemented CARE-aligned family-engagement events and collected parallel surveys from staff and parents/caregivers to capture their experiences, needs, and priorities related to family engagement in STEM.

This work is guided by the premise that family engagement bridges developmental and disciplinary learning—linking social-emotional processes that support youth growth (e.g., confidence, persistence, belonging) with disciplinary practices central to STEM (e.g., inquiry, reasoning, problem-solving). When parents/caregivers express positive attitudes toward STEM, provide related experiences, and model curiosity and persistence, youth develop stronger self-efficacy, belonging, and motivation (Berkowitz et al., 2015; Cian et al., 2022; Dou et al., 2019; Felton-Canfield, 2019; Shumow & Schmidt, 2014). With this developmental logic, we aimed to develop and test a theory-aligned STEM family engagement assessment system of CARE practices, and to examine how OST STEM programs interpret and use CARE-informed data.

This study addresses the following questions:

- What is the reliability, feasibility, and perceived usefulness of the CARE survey system in OST STEM settings?

- What patterns emerge in quantifiable CARE practices (baseline frequencies, perceived change, and forced-ranking priorities), and how do qualitative reflections explain those patterns and inform continuous improvement?

By embedding measurement within professional learning and reflection, PEP illustrates how theory-aligned tools bridge the research–practice divide, advancing equitable and sustainable family engagement in STEM learning.

2. Materials and Methods

This early-stage mixed-methods study assessed the feasibility, reliability, outcomes, and practical use of the CARE survey system in OST STEM programs participating in a six-month national Community of Practice (CoP) (Wenger, 1998; Wenger-Trayner & Wenger-Trayner, 2015). CoPs convene practitioners with shared goals to exchange knowledge, co-construct tools, and solve common challenges. Applied to family engagement, the model positions educators and families as co-learners who reflect on practice and adapt strategies collaboratively (Kekelis & Esho, 2022). Clover for Families and CARE were developed for OST STEM settings, and this study examines their use exclusively in those contexts, though both may hold promise for school-based STEM environments.

2.1. Overview

Over six months (January–June 2024), we convened the nine OST STEM programs virtually in both whole-cohort CoP sessions and small-group clinics/office hours. Cohort meetings included two trainings on the CARE Framework and the STEM Family Engagement Planning Tool, while clinics provided tailored consultation and implementation support. During this period, the CARE surveys were iteratively designed, practitioner-reviewed, and pilot-tested within the CoP; feedback from these sessions informed revisions to item wording, parallel parent/staff phrasing, survey format, and administration procedures.

Programs co-designed at least one CARE-focused family engagement event and participated in facilitated group interviews and two “data parties” to interpret results and plan improvements (Section 2.4 and Section 2.5). Surveys were administered at baseline (after the first CARE event) and after the final event. We embedded measurement design and testing within a CoP to narrow the research–practice gap and support iterative piloting of CARE-aligned strategies alongside data collection from staff and parents/caregivers. This approach aligns with the implementation science emphasis on adaptation, feedback, and sustainability (Ogden & Fixsen, 2014).

2.2. Participants

2.2.1. Program Sites

The nine participating OST STEM programs across eight U.S. states included community-based nonprofits, school-based programs, science centers, and one business-affiliated site (Table 1). Programs were located in the South (56%), Northeast (22%), Midwest (11%), and West (11%) of the United States. All offered year-round STEM or STEAM programming for K–12 youth and prioritized populations historically underrepresented in STEM. Across the cohort, programs served primarily lower-income families (89%) and racially/ethnically diverse participants, including Black/African American (78%), Hispanic/Latinx (78%), and multiracial (89%) families. Percentages for lower-income and underserved groups were reported by program directors using internal enrollment records (e.g., free/reduced lunch eligibility or local definitions of “underserved”).

Table 1.

Participating OST STEM program characteristics.

2.2.2. Staff

Twenty lead staff members (two to three per site) joined CoP activities, and an additional 22 participated indirectly (via internal program staff meetings and surveys). Across all staff, roles included directors, site coordinators, and STEM educators (~70% leadership/administration; ~30% frontline instruction). Most identified as female (81%) and had less than five years of experience in their current STEM role.

2.2.3. Parents/Caregivers

Sixty-seven parents/caregivers across nine programs completed baseline surveys, with an additional 26 responses collected following program events (reflective surveys). Participation varied across programs, from one-time attendance at large events to ongoing participation in workshops and roundtables. Most were biological parents (69%), with representation from grandparents, step-parents, and other caregivers. Roughly half (52%) self-identified as racially/ethnically diverse (30% Black/African American, 15% Hispanic/Latinx, 8% Asian/Asian American), and about one-quarter (27%) reported speaking a language other than English at home.

2.3. Survey Design and Development

CARE surveys were developed through a three-phase process combining evidence-informed item-drafting, practitioner review, and pilot testing.

In Phase 1, the research team translated CARE constructs into 4–5 items per domain using plain language (~7th-grade reading level) with internal review for coverage and clarity (see Table 2). In Phase 2, CoP participants provided feedback on clarity, relevance, and tone; revisions emphasized readability and community-aligned language. In Phase 3, small pilots with researchers and practitioners informed minor adjustments to item order, instructions, and digital layout.

Table 2.

Mapping CARE domains to example practices and survey items by respondent group.

Each survey included approximately 25 items plus demographics and an open-response prompt about needs for supporting children and families in STEM. Baseline surveys assessed the frequency of CARE-aligned practices using a 4-point scale (0 = Not at All, 3 = Almost Always) to avoid neutral midpoints and encourage directional responses. Retrospective self-change (RSC) surveys, administered at each program’s final CARE event, measured perceived change in CARE-related experiences using a 5-point scale (1 = Much Less Now, 3 = No Change, 5 = Much More Now), which provides a meaningful “no change” midpoint and supports reflection on shared practices and goals (Little et al., 2020). Baseline and RSC items were identical aside from instructions and response anchors. While parent/caregiver items began with “I …,” staff items began with “My program …” to reflect feedback that family engagement is supported by collaborative program practices (e.g., shared responsibilities, program-level policies) rather than the actions of any individual.

To ensure consistent data interpretation across all programs (many of which launched CARE at different times), respondents were instructed to anchor their reflection to the start of the academic semester (January). Using a common temporal anchor reduces timing-related bias, improves comparability, and enhances recall accuracy in reflective assessments. Retrospective formats have been shown to reduce pretest bias and practical burden in OST settings (Little et al., 2020). With one exception, baseline and RSC surveys used the same item stems, with changes applied only to instructions and response options to reflect frequency (baseline) or perceived change (RSC). On the baseline survey, four forced-ranking questions required participants to rank CARE domain-aligned statements from 1 (Most Important) to 4 (Least Important), with no ties permitted. Table 2 defines each CARE domain and provides example practices and survey items.

2.4. Data Parties

After survey analyses, each program participated in two researcher-facilitated, 60 min virtual “data parties,” a participatory sense-making process in which program staff collaboratively “dabble in the data” to interpret findings and plan improvements (Public Profit, 2016, 2024). Sessions used anonymized, aggregate CARE results (baseline frequency, change in practice) visualized in simple charts and tables. Facilitators guided program teams through a sequence of pattern scanning, consideration of plausible explanations and limitations, and action prioritization (e.g., quick wins vs. higher-effort items). Discussions focused on CARE patterns, equity-minded adjustments, and feasible, high-impact action steps. Families did not participate in these sessions; program staff reviewed parent/caregiver feedback and used it to inform planning.

2.5. Program Interviews

At the end of the project, semi-structured virtual interviews (45–60 min) were conducted with one to three staff per program. Two research team members attended each interview (facilitator; note-taker/timekeeper/tech support). The protocol covered: (a) intention/goals for family engagement; (b) usefulness of CARE for guiding practice; (c) information/resource needs surfaced with families; (d) use of parent/caregiver survey data; (e) perceived evidence of impact; and (f) satisfaction with project supports.

2.6. Procedures

Programs were selected via a competitive application process based on STEM focus, interest in strengthening family engagement, commitment to equity, and capacity to participate. The research team facilitated all professional learning and study activities. Surveys (baseline and RSC) were administered electronically via REDCap during each program’s first and last CARE-focused family event (mid-event or later). Across programs, the estimated duration between baseline and RSC surveys ranged from one to three months, with most programs completing the RSC surveys 60–100 days after baseline.

Program staff invited all families and STEM staff to participate in CARE events, where the surveys were offered. Participation in CARE surveys was voluntary and anonymous. To enhance accessibility, surveys were mobile-optimized, and programs were encouraged to offer bilingual administration using the Google Chrome built-in translation tool. No incentives were provided for survey completion, which may have contributed to lower RSC response rates. Staff also noted that families were experiencing survey fatigue due to multiple surveys administered across program and school settings.

Monthly staff reflections captured real-time experiences with CARE event planning and survey implementation. Within two weeks of survey completion, each program received a report (i.e., visual data dashboard) summarizing results, which anchored the data parties and interviews. Data parties and interview sessions were audio-recorded and transcribed with participant consent, and structured facilitator notes documented key themes.

2.7. Analytic Strategy

2.7.1. Quantitative Analyses

Analyses were conducted in SPSS (v28). Descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, and response distributions) were calculated for all items and subscales. Internal consistency was estimated with Cronbach’s α and McDonald’s ω for each CARE domain.

Forced-ranking (importance) indicators captured how participants ordered the CARE domains from Most Important (1) to Least Important (4). Figures display average percentages across respondents. For RSC scales, one-sample t-tests compared means to the scale midpoint (3 = “no change”); we report two-tailed α = 0.05 and effect sizes (Hedges’ g). Pre and RSC samples were treated independently as anonymity precluded individual matching, though some overlap was likely.

2.7.2. Qualitative Analyses

Using a quantitatively driven (QUAN → qual) mixed-methods design, qualitative analyses were used to explain and interpret quantitative patterns (Schoonenboom & Johnson, 2017). Data sources included CoP meeting notes, monthly staff reflections, interview transcripts, data party transcripts, and open-ended survey responses.

We analyzed interview transcripts and open-response prompts using hybrid inductive–deductive coding grounded in constructivist thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006, 2021) and guided by CARE domains and implementation outcomes (Proctor et al., 2011). CoP notes, staff reflections, and data party transcripts were analyzed using rapid synthesis methods to generate high-level summaries of practitioner insights (Suchman et al., 2023). Representative quotes are reported to contextualize quantitative results. Given the quantitative emphasis of this manuscript, we report only brief, explanatory themes here; a separate paper will provide full qualitative analysis.

3. Results

3.1. CARE Reliabilities

Across the nine programs, 42 staff and 67 parents/caregivers completed at least one CARE survey. Response rates averaged 82% for staff and 56% for parents/caregivers, with minimal missing data (<5%) and an average completion time under ten minutes. Internal consistency was excellent for both respondent groups and administrations: for parents/caregivers, Cronbach’s α = 0.83–0.95 and McDonald’s ω = 0.88–0.96; for staff, Cronbach’s α = 0.77–0.95 and McDonald’s ω = 0.86–0.96. Detailed reliability coefficients by CARE domain, respondent group, and administration (Baseline and RSC) are reported in Supplement C.

3.2. CARE Outcomes

Analyses focused on frequencies (baseline) and perceived change (RSC) in family engagement practices, priorities (importance rankings), and needs (open response). Item stems are abbreviated for item-level results.

3.2.1. Frequency of CARE Practices (Baseline)

At baseline, both groups reported moderate-to-high frequencies of CARE-aligned practices (Table 3). On average, parents/caregivers rated Connect and Reflect slightly higher (M = 2.47–2.53) than Act and Empower (M = 2.32–2.33). Staff showed the same pattern, with Connect and Reflect higher (M = 2.51–2.62) than Act and Empower (M = 2.41–2.51).

Table 3.

Mean (±SD) ratings of parents/caregivers’ and staff’s CARE experiences at baseline and project-end.

Parents/caregivers’ highest rated items were Connect (“feel welcomed,” M = 2.72, SD = 0.647) and Reflect (“think about the importance of STEM,” M = 2.51, SD = 0.742); lowest were Act (“info/materials for STEM at home,” M = 2.09, SD = 0.981) and Empower (“asked for input on child’s STEM learning,” M = 2.15, SD = 1.04). Staff’s highest items were Connect (“community feels welcomed,” M = 2.83, SD = 0.581) and Empower (“values parent/caregiver voices,” M = 2.71, SD = 0.673); lowest were Act (“info/materials for STEM at home,” M = 2.29, SD = 0.742) and Empower (“parents/caregivers learn STEM skills,” M = 2.26, SD = 0.885).

3.2.2. Perceived Change in CARE Practices (RSC)

At program end, both groups reported significant positive perceived change across all CARE domains (all p’s < 0.001; large effects: parents/caregivers g = 1.48–1.86; staff g = 1.71–2.05). On average, domain means were consistently above 4.0 (parents/caregivers, M = 4.26–4.33; staff, M = 4.17–4.29; Table 3). By domain, parents/caregivers reported the greatest perceived gains in Reflect (M = 4.33), followed by Connect (M = 4.32) and Act (M = 4.30), with Empower positive but lowest (M = 4.26). Staff showed a similar pattern with Connect highest (M = 4.29), closely followed by Reflect (M = 4.28) and Empower (M = 4.22), with Act lowest (M = 4.17).

At the item-level, parents/caregivers’ highest perceived gains were Connect (“feel welcomed,” M = 4.50, SD = 0.762), Reflect (“importance of STEM,” M = 4.46, SD = 0.706), and Act (“join hands-on STEM,” M = 4.46, SD = 0.706). Lowest—though still positive—were Act (“info/materials for STEM at home,” M = 4.12, SD = 0.864), Empower (“advise on STEM direction,” M = 4.12, SD = 0.816), and Connect (“easy-to-understand info,” M = 4.12, SD = 0.816). Staff’s highest RSC items were both in the Connect domain (“community feels welcomed,” M = 4.45, SD = 0.632; “builds family community,” M = 4.38, SD = 0.728). The lowest were Act (“info/materials for STEM at home,” M = 4.03, SD = 0.778), Connect (“someone available to talk,” M = 4.17, SD = 0.759), and Reflect (“ideas for STEM conversations,” M = 4.17, SD = 0.759).

3.2.3. Priorities

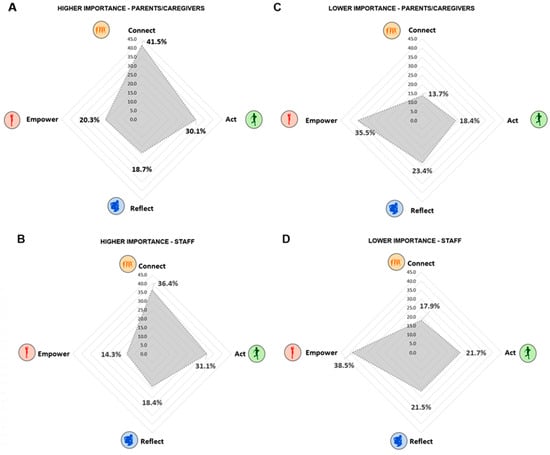

As shown in Figure 2A,B, both parents/caregivers and staff most frequently ranked Connect, followed by Act, as the “most important” relative to the other CARE domains. Empower was selected less often as “most important” (and more often as “least important”) when respondents were required to choose among the four CARE domains (see Figure 2C,D).

Figure 2.

Importance rankings for CARE domains by respondent group. Panels (A–D) display the percentage of respondents selecting each CARE domain—Connect, Act, Reflect, Empower—as the most (left; A,B) or least (right; C,D) important strategy across four forced-ranking prompts. Results are shown separately for parents/caregivers (top; A,C) and staff (bottom; B,D). Both groups most often prioritized Connect and Act, relative to Reflect and Empower, when ranking family engagement practices in STEM programs.

When comparing the percentage difference between “most” and “least” important ratings, Reflect showed only small descriptive gaps for both groups (Parents/Caregivers: Δ = 4.7 percentage points; Staff: Δ = 3.1 points). Larger differences emerged for Connect, which parents/caregivers prioritized as “most important” far more often than “least important” (Δ = 27.8 points) and staff showed a similar pattern (Δ = 18.5 points). By contrast, Empower showed the opposite pattern: parents/caregivers selected it as “least important” more frequently than “most important” (Δ = −15.2 points), and staff showed an even larger negative gap (Δ = −24.2 points). Differences for Act fell between these two domains, with moderate gaps for parents/caregivers (Δ = 11.7 points) and staff (Δ = 9.4 points).

At the item level, parents/caregivers most frequently prioritized practices related to creating a welcoming STEM environment (65.7%) and strengthening bonds with their child through STEM activities (53.1%) within Connect. For Act, families most often selected knowing which STEM skills to support at home (43.1%) and doing STEM challenges together (35.3%). Reflect items showed a more even distribution (range: 11.6–24.5%); the highest-ranked item involved sharing their family’s STEM interests, preferences, and needs with staff (24.5%). Within Empower, families most often prioritized having influence over decisions that affect their child’s STEM learning, such as advocating for needed resources or supports (33.1%) and participating in program decision-making (40.0%), while structured advisory meetings (7.1%) or formal feedback sessions (0%) were least frequently selected.

To explore whether event structure influenced how parents/caregivers prioritized CARE domains, we compared “most important” ratings across two program formats. Dialog-rich, multi-component engagement models (Programs B, D, E, F, G; n = 37) provided coordinated opportunities for “hands-on” and “minds-on” STEM activities, structured discussion, and parent–staff dialog. Activity-based, stand-alone events (Programs A, C, H, I; n = 30) were typically single-session or episodic formats centered on exploration or information-sharing without extended dialog or iterative engagement.

Across the dialog-rich programs, parents/caregivers reported a more balanced distribution of priorities (Connect: M = 37.4%, Reflect: M = 21.8%, Act: M = 29.9%, Empower: M = 26.7%). In contrast, activity-based, stand-alone events produced a more polarized profile: Connect was prioritized most frequently (M = 48.8%), Empower least frequently (M = 14.1%), and Act remained moderate (M = 26.3%). Reflect was also less frequently prioritized in stand-alone events (M = 16.2%).

When comparing program formats, Connect was prioritized by nearly half of parents/caregivers at stand-alone events (M = 48.8%, range = 32.5–65.0%) compared with about one-third in dialog-rich models (M = 37.4%, 21.1–60.0%), while Empower was prioritized almost twice as often in dialog-rich formats (M = 26.7%, range = 16.7–37.5%) compared with stand-alone events (M = 14.08%, range = 5.0–19.0%).

3.2.4. Connecting Parent/Caregiver Feedback and Needs to CARE Results

Across all responding parents/caregivers, the most requested supports were expanded STEM opportunities for their children (23.3%), hands-on STEM resources (16.3%), and greater community collaboration (16.3%). These needs reflect a desire for more frequent, accessible, and sustained engagement with STEM inside and outside program settings. When the qualitative open-response feedback was examined alongside CARE frequency ratings, two contrasting engagement patterns emerged (Table 4).

Table 4.

Representative Parent/Caregiver Feedback by CARE Domain and Baseline Frequency Level.

Parents/caregivers with higher baseline frequencies for CARE practices (≥2, Often or Almost Always) typically described their children’s STEM programs as welcoming, well-organized, and engaging. Their suggestions tended to focus on enhancing already positive experiences (e.g., more hands-on activities, additional classes, or building community partnerships). These requests align closely with stronger Connect and Act experiences.

In contrast, parents/caregivers with lower baseline frequencies (<2, Not at All or Sometimes) more often emphasized barriers related to communication, relevance, and navigation. These patterns are consistent with relatively weaker Connect, Reflect, and Empower experiences (Table 4). Their needs reflected these challenges, including requests for clearer communication and information, guidance for at-home STEM activities, materials in multiple languages, and support for navigating STEM pathways.

3.2.5. Connecting Staff Feedback and Needs to CARE Results

Staff discussions during the data parties provided important context for interpreting parent/caregiver ratings of the CARE domains. Staff noted that higher prioritization of Connect and Act reflects the early-stage engagement patterns they observed in practice: families readily attend and participate in hands-on STEM experiences, whereas deeper forms of engagement (e.g., offering feedback, assuming leadership roles) take longer to develop. As one educator explained, “Families are fine showing up and doing the hands-on stuff … but giving feedback or taking the mic takes time. They need to feel comfortable first.”

Staff described how Reflect and Empower tend to emerge only after a foundation of trust and consistent relationships has been established. They attributed parents/caregivers’ lower prioritization of Empower to confidence gaps (e.g., “I’m not a STEM person”) rather than disinterest, as well as unclear expectations and the need for program-provided structure. As one educator framed it, “We’re asking them to lead, but we haven’t given them the tools yet. Empowerment has to be scaffolded.”

Programs serving younger children highlighted the importance of modeling and coaching to help parents/caregivers translate everyday activities into STEM-rich conversations and gradually share decision-making power. Staff also pointed to the need for greater coordination across OST programs, schools, and industry partners to support long-term navigation and make STEM pathways more visible: “Families need to see a clear pipeline to STEM careers.”

Program needs identified by staff in their open-response survey comments were consistent with these discussion-based insights. The three most common were: professional learning/career development (34.4%), practical STEM materials and curricula (25.0%), and strategies for engaging families (15.6%). Staff viewed these as essential for helping families progress toward deeper Reflect and Empower practices over time. As a group, staff converged on the view that families’ CARE priorities reflect their stage of engagement within the program, with deeper forms of Reflect and Empower emerging only when relational foundations are strong and necessary structural supports are provided.

3.3. Staff Reflections on Implementation

Across data party discussions and interviews, staff described CARE’s relevance to key implementation outcomes: utility, feasibility, acceptability, appropriateness, adoption, and sustainability (Proctor et al., 2011). These reflections confirmed that CARE data are useful and practical, bringing family perspectives to continuous improvement efforts.

3.3.1. Perceived Utility of CARE

Staff reported that CARE elicited specific, actionable feedback and supported transparent communication with families and colleagues: “It helped us get beyond ‘great event’ … now we ask why.” Responsiveness to family input was linked to greater participation: “If parents see we act on their input, more get involved.” Practical tactics included brief on-site QR polls (“They can pull it up on their phone right there”) and quick-share snapshots to spark dialog. Several teams described a shift from anecdotes to evidence, using CARE to make participation visible and trackable, and planning “a more systematic data collection system… to add some rigor.” Staff also described CARE as both a mirror (revealing gaps) and a map (prioritizing actions), prompting concrete adjustments such as shifting event times, simplifying and translating communications, and sharing results back via concise, visual summaries. Teams emphasized closing the loop so families “see that policies change because of their voices,” leading to higher participation.

3.3.2. Feasibility and Acceptability

Implementation was viewed as manageable and non-stigmatizing (“It didn’t take long … it made sense for staff and families”; “It wasn’t judgmental … it made us think”). While parent/caregiver participation in surveys was cited as challenging in general, programs addressed barriers to the CARE survey with creative solutions like in-person administration, on-site QR codes, brief prompts, pairing surveys with take-home kits, and leveraging trusted staff. Pain points included platform tone (i.e., REDCap felt “clinical”), cognitive load for ranking items, and digital/language hurdles. Recommendations included previewing or even revising instruments with community members, shorter forms, and more user-friendly, multilingual options.

3.3.3. Appropriateness

Participants affirmed the fit of the domains with everyday practice: “The questions fit what we do … communication, activities, getting parents involved.” Emphasis on Connect and Act is aligned with family readiness. To balance standardization and local relevance, a few programs added 1–2 local items (e.g., preferred times, topics) and used brief exit polls. One leader described CARE as “a true north … keeping us grounded on what’s important,” while noting that deeper reflection required more time and facilitation, and that human-centered, strengths-based wording increased trust and completion. Findings also challenged assumptions that high-profile events were most valued; families prioritized dependable opportunities and clear, timely information, reinforcing the appropriateness of CARE’s emphasis on Connect and Act for day-to-day practice.

3.3.4. Adoption and Sustainability

Most programs planned cyclical reuse of CARE and regular data discussions: “We’ll keep doing this … it gives us something to look at every year, not just a one-off.” Visible follow-through was emphasized for “instant buy-in.” Next steps included light-touch technical assistance between cycles, reuse of items for grant reporting with follow-ups to close feedback loops, and integration into professional learning and multi-site events. Several teams reported a broader shift toward systematic, iterative data use for family engagement. Programs noted that reuse of surveys, routine share-backs of results, and explicit “we decided because [survey evidence] …” summaries build buy-in and will sustain family participation over time.

4. Discussion

The STEM Family Partnership & Empowerment Project (PEP) sought to advance both the practice and study of family engagement in STEM by introducing Clover for Families and its practical and flexible heuristic, CARE—Connect, Act, Reflect, Empower—to guide programs in building relational, participatory, and culturally grounded engagement with families, with data to support reflection, decision-making, and continuous improvement. Across nine community- and school-based programs, staff implemented CARE strategies and administered parent/caregiver and staff surveys to examine how engagement develops when families and educators are supported to collaborate around children’s STEM learning. This initial study highlights both the promise of the CARE surveys as theoretically coherent instruments and their practical value as reflective tools to help programs better understand families’ experiences and take more intentional steps toward inclusive and responsive partnerships between families and educators in STEM learning contexts (Ishimaru et al., 2019; Mapp & Bergman, 2021).

By translating a developmental theory of resilience into a practical framework for OST STEM settings, this study contributes to the field in three ways. First, it bridges social-emotional development and STEM education research by adapting the Clover Model into Clover for Families and creating the CARE framework. Second, it introduces empirically supported, practitioner-friendly tools for evaluating and improving family engagement in OST STEM programs. Third, it demonstrates how collaborative reflection and continuous learning processes can advance both implementation science and equitable participation in STEM.

4.1. Integrating Theory, Practice, and Evidence

The CARE framework is grounded in Clover for Families, a developmental theory that conceptualizes engagement as an evolving process rather than a fixed state (Noam & Triggs, 2018). Consistent with learning ecologies perspectives (Barron et al., 2009), CARE frames family engagement as distributed across relationships, roles, and contexts connecting home, school, and community. Its relational focus reflects the central role of trust (Bryk & Schneider, 2002), or the belief that respect and shared purpose underpin effective partnerships, and extends Ishimaru et al.’s (2019) call for co-design approaches that position families as active agents. CARE offers a developmental progression from connection and participation to reflection and shared decision-making, translating social–emotional principles into accessible, practice-aligned domains (Allen & Noam, 2021a; Darling-Hammond et al., 2020).

Internal consistency results were strong for both surveys. While aggregate analyses of CARE ratings (frequency and perceived change) suggested uniformly high ratings on average, closer inspection revealed meaningful variation across programs, suggesting that contextual factors such as program structure, duration, level of family engagement planning, and amount of facilitation may influence engagement experiences. Program partners noticed that patterns diverged across programs, underscoring that important differences can be masked in aggregate data. Qualitative findings further validated this distinction: higher CARE ratings were associated with positive, strength-focused comments, while lower ratings aligned with descriptions of challenges or unmet needs. This convergence of quantitative and qualitative evidence provides early evidence that CARE items meaningfully distinguish between higher- and lower-engagement family experiences. To underscore the priorities of families and staff, forced-ranking items provided greater discrimination, consistently elevating Connect and Act over Reflect and Empower. This methodological contrast suggests rankings can surface relative priorities even when perceptions of practice are high, and can be used to structure planning conversations among families and staff.

4.2. Developmental Patterns of Engagement

Across programs, Connect and Act (domains emphasizing belonging, communication, and hands-on participation) were viewed as most important by both parents/caregivers and staff. This pattern aligns with findings that these practices serve as gateway conditions for sustained partnership in STEM engagement (Barron et al., 2009; Mapp & Bergman, 2021). Reflect was prioritized more often than Empower, but the differences between its “most” versus” least” important ratings were small, indicating more moderate and variable endorsement than Connect and Act. Staff narratives indicated that reflective practices require additional time, resources, and structured facilitation to develop and enact, particularly in programs where family interactions occur episodically rather than continuously. This suggests that joint sense-making requires sustained, well-supported professional learning opportunities to support meaningful staff-family dialog (Kekelis, 2023).

By contrast, Empower was more often ranked lowest in importance and experience. It also showed the largest difference between “most” and “least” important rankings for both parents/caregivers and staff. Staff reflections suggest this pattern is developmental rather than indicative of disinterest (Ishimaru et al., 2019). Empowerment depends on relational security, self-efficacy, and organizational openness to sharing power (Bryk & Schneider, 2002). Staff endorsed “valuing parent/caregiver voice” highly at baseline, while families ranked Empower lowest on ranking items, suggesting a perception-experience gap that programs can address by providing more frequent, decision-linked opportunities for influence (Bang et al., 2016). Item-level patterns (i.e., different practices mapping to Empower) further indicate that families tend to favor advocacy for resources their children need and immediate, conversational forms of voice (e.g., giving input to staff about their child’s STEM learning) over formal interactions (e.g., advisory councils or standing meetings to collect feedback). This pattern aligns with research on equity-oriented partnership models in which participation evolves from consultation to co-creation as relationships deepen and trust is established (Ishimaru et al., 2019).

Exploratory comparisons of program format suggested that smaller, dialog-rich events (e.g., family roundtables or workshops) more often elevated Empower as a priority than larger, stand-alone, activity-based events (e.g., open-houses or tabling). Although these differences are descriptive and should be interpreted cautiously, programs that created structured opportunities for small-group dialog, co-planning, or shared decision-making tended to be associated with higher endorsement of empowerment-oriented practices. In contrast, diffuse or high-traffic event formats tended to be less associated with Empower but more often elevated Connect. Because programs varied on multiple unmeasured features (e.g., community composition, facilitation style, event frequency, group size), these patterns are hypothesis-generating rather than causal.

Together, these CARE patterns align with Clover for Families’ developmental theory, in which belonging and engagement pave the way for deeper reflection and shared leadership (Bryk & Schneider, 2002; Gutiérrez et al., 2019). These findings have design implications. Empowerment requires infrastructure that enables families to reflect with staff on options and influence decisions (Bang et al., 2016). To elevate Empower, programs can (a) scaffold decision-linked activities rather than holding meetings; (b) build repeat, low-barrier feedback loops that normalize voice across settings; and (c) measure everyday agency to capture leadership beyond formal committees. These strategies align with learning ecologies and organizing/co-design scholarship underscoring cross-setting participation, consequential roles, and equity-centered collaboration (Bang et al., 2016; Barron et al., 2009; Gutiérrez et al., 2019). Additionally, they are measurable within CARE, enabling iterative improvement cycles.

4.3. Practitioner Reflections and Implementation Insights

Staff reflections indicated that they found CARE feasible, relevant, and sustainable. Its brevity and clarity made it accessible to families, and its dual design promoted reflection across roles. Educators described CARE as supporting meaningful dialog rather than delivering an evaluative mandate. Program teams were surprised that most families did not prioritize agency and leadership (Empower) relative to other CARE domains. Some attributed these epiphanies to CARE being a mirror—revealing relational blind spots—and a map—offering a shared language for growth. Staff described Connect and Act as “entry points,” especially for families facing linguistic and logistical barriers, creating psychological safety for later Reflect and Empower stages, echoing sociocultural views of agency emerging through guided participation (Rogoff, 2003; Vygotsky, 1978). CARE was viewed as useful for eliciting actionable feedback and transparent share-backs, feasible with light-touch adaptations, appropriate to core practice, and likely to be adopted cyclically with modest support.

Programs used CARE in “data parties” to align intentions with experiences, an example of practice-linked professional learning (Coburn & Penuel, 2016; Wenger-Trayner & Wenger-Trayner, 2015). Sharing results with families using accessible communications (e.g., bilingual infographics) reinforced transparency and trust (Darling-Hammond et al., 2020). Programs embed data collection naturally within events, demonstrating that assessment can be relationship-building (Ishimaru et al., 2019; Yohalem & Wilson-Ahlstrom, 2010). Requested refinements (e.g., shorter items, friendlier platforms, multilingual options) reflect a broader shift toward human-centered measurement (Ishimaru et al., 2019). Several teams planned to institutionalize CARE in annual planning, signaling potential for scaling across OST systems.

4.4. Cultural Responsiveness and Equity Considerations

Because we intentionally partnered with OST STEM programs serving culturally and linguistically diverse communities, including multilingual families, recent immigrants, and racially diverse populations, cultural responsiveness was an essential consideration in how CARE was shared, interpreted and enacted. Programs were selected, in part, for explicit commitments to equity in STEM and for serving communities historically marginalized in STEM pathways. Although cultural responsiveness was not directly assessed in this study, these contextual conditions shaped how staff engaged with CARE’s domains and how families experienced events.

Across programs, staff used CARE to design engagement strategies that honor families’ cultural identities and reduce linguistic or structural barriers. Examples included bilingual communication and facilitation; integrating family storytelling into STEM activities; connecting engineering or science activities to local communities’ identity and culture; and inviting STEM role models whose racial and linguistic identities reflected the program community. Several programs also created informal opportunities for families to influence programming, such as shaping event pacing or suggesting STEM themes. These practices align with research on culturally responsive partnership building (Mapp & Bergman, 2021; Ishimaru et al., 2019), learning ecologies that emphasize culturally grounded forms of participation (Barron et al., 2009), and equity-oriented design models in which participation evolves from consultation to co-creation as trust deepens (Ishimaru et al., 2019; Bang et al., 2016).

These examples underscore the need for future research that directly examines cultural responsiveness within the CARE system. This study did not have sufficient capacity to assess whether CARE items function similarly across cultural or linguistic groups, or how cultural norms shape families’ priorities. Future work should include culturally grounded item refinement, collaborative translation and adaptation, and tests of measurement invariance, ideally through family-led co-design (Ishimaru et al., 2019). Such efforts are essential to ensure that CARE functions equitably across diverse communities and supports culturally sustaining family–educator partnerships in STEM.

4.5. Limitations

Although this study provides early evidence for the feasibility and utility of the CARE surveys, it is exploratory and subject to several limitations. First, the modest, nonprobability sample nested within nine programs constrains psychometric inference and generalizability. Internal consistencies were strong, but factor analyses and more nuanced subgroup or cross-program comparisons (e.g., significance testing by engagement format, race/ethnicity, home language, income) were not possible due to sample size, small cell counts per site, and heterogenous implementation contexts. Second, self-report surveys reflect perceived rather than observed engagement; we did not directly verify what families did at home. Third, anonymity and variable attendance impeded matched-pairs analyses, which prevented within-person change estimates. Attendance at final CARE events was also lower and more variable than at baseline, reflecting both expected attrition and logistical challenges. Fourth, selection and social-desirability bias are possible: families more connected to programs may have been more likely to respond, and staff may have endorsed desirable practices. Fifth, measurement, mode, and implementation factors may have influenced responses. The “clinical” tone of the REDCap platform cited by some programs, the cognitive load for ranking items, and the use of browser-based language translation may have shaped how respondents engaged with or understood the surveys (e.g., potential loss of nuance, lack of cultural adaptation, translation errors). At the survey-level, design compromises, such as wording staff items at the program level (“My program …”) and parent/caregiver items at the individual level (“I …”) limit parallelism across informants when comparing CARE results. Additionally, the program end survey used a retrospective format, which can introduce memory distortions, social desirability, and other response biases; we judged this approach appropriate because it can reduce pretest bias for noncognitive constructs and minimize practical burdens in OST settings (Little et al., 2020). Sixth, our exploratory cross-program analyses of CARE priorities and program features were descriptive and hypothesis-generating rather than confirmatory. Finally, many OST settings that could benefit from the CARE survey system (e.g., highly flexible, drop-in, or short-term programs) face structural barriers to longitudinal or matched pre-post designs. These constraints do not diminish CARE’s utility; rather, they underscore the need for flexible, low-burden tools that provide meaningful feedback in contexts where more traditional data-driven approaches are not feasible.

4.6. Recommendations and Future Directions

Our findings led to the following recommendations for programs, researchers, and practitioners seeking to strengthen family engagement in STEM through Clover for Families and the CARE continuous learning system. Some recommendations are foundational, reflecting practices that enable programs to build and sustain the relational, cultural, and structural conditions necessary to enact all domains of CARE. Others represent more advanced directions appropriate for programs that are ready to deepen co-design, expand leadership opportunities, or examine CARE’s links to youth outcomes.

Foundational recommendations use CARE as a reflective tool to understand families’ starting points and guide responsive program design. First, programs can administer CARE surveys as a baseline or periodic “pulse check” to identify how frequently families and staff experience, or how they prioritize, Connect, Act, Reflect, and Empower practices, and use these data to guide early action steps. Second, programs can use CARE to be more culturally responsive, ensuring that all families are invited and included, and that communications, activities, and leadership opportunities resonate with culturally and linguistically diverse families and communities (Bang et al., 2016; Ishimaru et al., 2019). As part of this work, future implementation of CARE should explore whether patterns of engagement vary across demographic and linguistic groups, cultures/communities, and levels of participation. Third, CARE can help programs reframe family engagement as a developmental trajectory, in which empowerment emerges gradually through cycles of connecting, participating, and reflecting. In these ways, CARE can help programs build trust, reduce barriers to participation, and create shared reference points with families (Mapp & Bergman, 2021).

Building on these foundations, several advanced recommendations can deepen CARE’s role within continuous improvement systems. One priority is to broaden co-design by partnering with parents/caregivers, youth, and community members to refine CARE tools and associated programming, ensuring conceptual clarity, cultural and contextual relevance, and accessibility in survey items and engagement practices (Ishimaru et al., 2019). In addition, larger organizations and multi-site networks may embed CARE within CoPs to sustain reflection, collaboratively problem-solve, build shared understanding, and bridge research–practice divides (Coburn & Penuel, 2016; Darling-Hammond et al., 2020; Kekelis & Esho, 2022; Wenger-Trayner & Wenger-Trayner, 2015). Programs can also build capacity by partnering with peer organizations to combine resources and expertise, or with system-building groups, such as Statewide Afterschool Networks and STEM Learning Ecosystems, to leverage their convening power and funds to provide CoP support or seed grants (Traphagen et al., 2020). As programs mature in their use of data, CARE can also guide systems-level improvement, supporting network-wide learning cycles and informing cross-site coordination around family engagement priorities (Traphagen et al., 2020).

Finally, we offer advanced recommendations to strengthen CARE as a research and evaluation tool. After receiving program feedback about limitations of current survey and translation platforms, we now prioritize more intuitive, family-friendly digital tools for collecting CARE data, to be developed in partnership with families and user-experience designers. Such improvements could reduce burden, increase accessibility, and help ensure that families experience the CARE process as welcoming, responsive, and empowering. At the measurement level, future work should refine CARE survey items in partnership with families and practitioners, including more precisely differentiating forms of empowerment, as current items may not fully capture the everyday agency that parents/caregivers enact (Barron et al., 2009; Gutiérrez et al., 2019). In addition, rigorous testing of the CARE survey’s psychometric properties will require replication with larger and more diverse longitudinal samples, the use of factor-analytic methods, and tests of measurement invariance across respondent groups and contexts, including in-school settings. Methodological advances will also require linking perceived change to observed practice (in-program and at home), implementing matched designs that preserve anonymity (e.g., participant-generated IDs), and triangulating CARE survey findings with consequential outcomes such as participation patterns, program persistence, and progression along STEM pathways. These efforts will build a stronger validity argument for CARE and expand its utility for continuous improvement and research.

Together, these recommendations offer a roadmap for strengthening CARE as both a reflective practice tool and a research and evaluation instrument, helping programs translate Clover for Families theory into developmentally grounded, culturally responsive action through the CARE framework.

5. Conclusions

This study offers early validity and implementation evidence for CARE as a practical tool for strengthening family engagement in OST STEM programs. By translating Clover for Families into accessible domains—Connect, Act, Reflect, Empower—CARE bridges developmental theory and equitable practice. Findings indicate that family engagement is a relational process that cannot be achieved by simply completing a list of activities. Empowerment arises from sustained cycles of belonging, participation, and reflection within trusting relationships. CARE’s coherence, feasibility, and practitioner uptake demonstrate its potential as both a measurement system and a professional learning framework. Viewed through this developmental lens, CARE helps programs move beyond valuing families simply for “showing up” by understanding the conditions that enable families to “take the mic,” meaning to reflect, contribute, and shape STEM learning alongside educators. This shift strengthens family engagement and, in turn, supports stronger youth participation in STEM. Future work will refine the CARE tools through collaborative co-design with family and community partners, extend validation longitudinally, and link CARE to youth outcomes. When families and educators are true partners, family engagement becomes not just measurable but transformative—embedding equity and resilience at the heart of STEM learning ecosystems.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/educsci15121669/s1, Supplement A: Systematic Review References Supporting CARE Development; Supplement B: CARE Domain–Item Crosswalk; Supplement C: CARE Survey Reliability Tables.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.J.A. and G.G.N.; methodology, P.J.A. and G.G.N.; formal analysis, P.J.A.; investigation, P.J.A.; resources, P.J.A. and G.G.N.; data curation, P.J.A.; writing—original draft preparation, P.J.A.; writing—review and editing, P.J.A. and G.G.N.; visualization, P.J.A.; supervision, G.G.N.; project administration, P.J.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a Cambiar Thrive grant from Cambiar Education.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was reviewed by the Mass General Brigham Institutional Review Board (Protocol #1179; 16 November 2023) and deemed exempt as it did not meet the criteria for human subjects research under 45 CFR 46.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to restrictions (e.g., privacy, legal or ethical reasons). Permission is needed from participating programs.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the nine participating program partners for their commitment to this study and their openness in sharing plans, successes, and challenges to support collective learning. We are also grateful to the ISRY team—especially Sara Hoots, Sabie Marcellus, and Victoria Oliveira—the Cambiar Thrive team—especially Taryn Campbell and Derwin Sisnett—and the broader Cambiar Thrive learning community for their engagement throughout the project. Appreciation is extended to the STEM Next Opportunity Fund for supporting the continued development of the CARE/Planning Tool and assisting with project recruitment. The collective contributions of funders, partners, educators, and families were integral to advancing equitable and collaborative approaches to STEM family engagement.

Conflicts of Interest

Author P.J.A. declares no conflict of interest. Author G.G.N. serves on the board of PEAR, Inc., an organization that may be affected by this research. The funder had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CARE | Connect, Act, Reflect, Empower |

| CoP | Community of Practice |

| DoS | Dimensions of Success |

| OST | Out-of-school time |

| P/C | Parent/caregiver |

| PEP | Partnership & Empowerment Project |

| S | Staff |

| RSC | Retrospective self-change |

| STEM | Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics |

References

- Afterschool Alliance. (2015). Full STEM ahead: Afterschool programs step up as key partners in STEM education. Afterschool Alliance. Available online: http://www.afterschoolalliance.org/AA3PM/STEM.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2017).

- Ainsworth, M. S., & Bowlby, J. (1991). An ethological approach to personality development. American Psychologist, 46(4), 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, P. J., Bergès, I., Joiner, R., & Noam, G. (2022). Supporting every teacher: Using the Holistic Teacher Assessment (HTA) to measure social-emotional experiences of educators. Teaching and Teacher Education, 119, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, P. J., & Noam, G. G. (2021a). Impactful family engagement requires strategic visioning and planning: Lessons from the STEM Family Engagement Planning Tool Pilot. In NSF INCLUDES Coordination Hub (Ed.), Centering inclusivity and equity within family engagement in STEM (Research Brief No. 7). Cambridge Core. Available online: https://acrobat.adobe.com/link/track?uri=urn%3Aaaid%3Ascds%3AUS%3Aeec74c02-e488-4808-84b3-da5d94ab891e (accessed on 12 November 2021).

- Allen, P. J., & Noam, G. G. (2021b). STEM family engagement: A planning tool. Institute for the Study of Resilience in Youth (ISRY). Available online: https://www.isry.org/familyengagementtool (accessed on 23 December 2021).

- Allen, P. J., & Noam, G. G. (2023). Building consensus for integrated STEM and social-emotional development: From convening to implementation. Connected Science Learning, 5(3), 12288875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, P. J., & Noam, G. G. (2024). A Systematic review of STEM and social-emotional development in out-of-school time programs: Executive Summary. Institute for the Study of Resilience in Youth (ISRY). Available online: https://informalscience.org/research/executive-summary-a-systematic-review-of-stem-learning-and-social-emotional-development-in-out-of-school-time/ (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Andrews, V., Oliveira, V., Allen, P. J., Gitomer, D. H., & Noam, G. G. (2023). Reflecting on STEM Classroom Experiences: The Power of an Observation Tool with an Integrated STEM/SED Lens. Connected Science Learning, 5(3), 12288876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1986). The explanatory and predictive scope of self-efficacy theory. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 4(3), 359–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (2001). Social Cognitive Theory: An Agentic Perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bang, M., Faber, L., Gurneau, J., Marin, A., & Soto, C. (2016). Community-based design research: Learning across generations and strategic transformations of institutional relations toward axiological innovations. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 23(1), 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, B., Martin, C. K., Takeuchi, L., & Fithian, R. (2009). Parents as learning partners in the development of technological fluency. International Journal of Learning and Media, 1(2), 55–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, T., Schaeffer, M. W., Maloney, E. A., Peterson, L., Gregor, C., Levine, S. C., & Beilock, S. L. (2015). Math at home adds up to achievement in school. Science, 350(6257), 196–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, M. R., Gutierrez, K., Hoyle, K. J., Harper, L. A., Painter, J. L., & Ragan, S. (2017, April 27–May 1). Motivational factors underlying rural, underrepresented students’ achievement and STEM perceptions in after-school STEM clubs [AERA Online Paper Repository]. Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, San-Antonio, TX, USA. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED608861 (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 328–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryk, A. S., & Schneider, B. (2002). Trust in schools: A Core resource for improvement. Russell Sage Foundation. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7758/9781610440967 (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Carlone, H. B., & Johnson, A. (2007). Understanding the science experiences of successful women of color: Science identity as an analytic lens. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 44(8), 1187–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cian, H., Dou, R., Castro, S., Palma-D’souza, E., & Martinez, A. (2022). Facilitating marginalized youths’ identification with STEM through everyday science talk: The critical role of parental caregivers. Science Education, 106(1), 57–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke-Midura, J., Sun, C., Pantic, K., Poole, F. J., & Allan, V. (2019). Using informed design in informal computer science programs to increase youths’ interest, self-efficacy, and perceptions of parental support. Association for Computing Machinery Transactions on Computing Education, 19(4), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coburn, C. E., & Penuel, W. R. (2016). Research–practice partnerships in education: Outcomes, dynamics, and open questions. Educational Researcher, 45(1), 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabney, K. P., Tai, R. H., & Scott, M. R. (2016). Informal science: Family education, experiences, and initial interest in science. International Journal of Science Education, Part B, 6(3), 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling-Hammond, L., Flook, L., Cook-Harvey, C., Barron, B., & Osher, D. (2020). Implications for educational practice of the science of learning and development. Applied Developmental Science, 24(2), 97–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. Macmillan Company. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J. (1959). Experience and education. Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Dou, R., Hazari, Z., Dabney, K., Sonnert, G., & Sadler, P. (2019). Early informal STEM experiences and STEM identity: The importance of talking science. Science Education, 103(3), 623–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, R., Villa, N., Cian, H., Sunbury, S., Sadler, P. M., & Sonnert, G. (2025). Unlocking STEM identities through family conversations about topics in and beyond STEM: The contributions of family communication patterns. Behavioral Sciences, 15(2), 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2006-08575-000 (accessed on 21 October 2020).

- Edwards, C. D., Lee, W. C., Knight, D. B., Fletcher, T., Reid, K., & Lewis, R. (2021). Outreach at scale: Developing a logic model to explore the organizational components of the summer engineering experience for kids program. Advances in Engineering Education, 9(2), n2. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1309229.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Epstein, J. L. (2008). Improving family and community involvement in secondary schools. The Education Digest, 73, 9–12. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/88769cf455df6bb8df633db0addee77c/1.pdf?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=25066 (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Felton-Canfield, K. J. (2019). The impacts on rural families when engaging in STEM education [Master’s thesis, University of Nebraska-Lincoln]. Available online: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/teachlearnstudent/105/ (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Fleshman, P. J. (2012). Beyond the scores: Mathematics identities of African American and Hispanic fifth graders in an urban elementary community school [Ph.D. dissertation, The City University of New York]. Available online: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2222/ (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Garip, G., Richardson, M., Tinkler, A., Glover, S., & Rees, A. (2021). Development and implementation of evaluation resources for a green outdoor educational program. The Journal of Environmental Education, 52(1), 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillen, A. (2018). The development of the academic identity of the Mexican-American bilingual elementary learner through educational robotics [Ph.D. dissertation, University of Texas at San Antonio]. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/docview/2046279980 (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Gutiérrez, K. D., Higgs, J., Lizárraga, J. R., & Rivero, E. (2019). Learning as movement in social design-based experiments: Play as a leading activity. Human Development, 62(1–2), 66–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülhan, F. (2023). Parental involvement in STEM education: A systematic literature review. European Journal of STEM Education, 8(1), 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]