Abstract

Based on the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), this is the first study that integrates Entrepreneurial Policy (EPL) and Entrepreneurial Network Relations (ENR) to examine the direct and indirect effects on entrepreneurial intention (INT) in Thailand. The quantitative method employs a structural equation model (SEM) to analyze 420 valid samples from eight universities. Model fix with χ2 = 183.31, df = 224 p = 0.98 GFI = 0.97 AGFI = 0.95 RMR = 0.031 RMSEA = 0.000. The results showed EPL has the most direct influence on (INT) β = 0.38, like ENR, which indirectly shapes (INT) through attitude and self-efficacy. The model’s R2 of 0.69 highlights the significance of policy support and social networks in (INT). The findings provide theoretical contributions and practical implications. Theoretically, expanding TPB by incorporating policy and social network dimensions offers a comprehensive understanding of entrepreneurial behavior. Universities integrate entrepreneurship education and innovation into engineering curricula and implement these concepts in other faculties or institutions. Government agencies support startup policy funds, tax incentives, and innovation hubs. Industries can establish a mentorship network to promote entrepreneurial intention and reduce graduate unemployment. Support both the ecosystem and innovative commercialization.

1. Introduction

Education serves as the most critical foundation for human and national development, especially entrepreneurship education for engineering students. This becomes increasingly vital in an era driven by technology and innovation. As the world transitions toward a knowledge-based and innovation-led economy, the role of engineers as potential entrepreneurs has gained greater significance. The combination of technical expertise with entrepreneurial competencies not only fosters the creation of high-impact innovations but also acts as a key driver of sustainable economic growth, especially in developing countries such as Thailand.

This perspective is comparable to the work of Nambisan (2017), Abdelmagid et al. (2025), and Silva León et al. (2025), who emphasized that advances in digital and green technologies accelerate entrepreneurial actions and lead to the emergence of new innovation-driven ecosystems, such as digital platforms and the green digital economy. Alike, Audretsch and Belitski (2021), Diepolder et al. (2024), and Dote-Pardo et al. (2025) have recognized entrepreneurship as a crucial mechanism for economic dynamism to generate new business opportunities, increase employment, and stimulate innovation.

In the context of developing nations like Thailand, recent statistics from the Office of the Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Higher Education, Science, Research, and Innovation (MHESI, 2024) reported that among 333,418 graduates in 2024, approximately 191,300 or 57% were unemployed. Only 8.4% engaged in entrepreneurial activities, compared with 20–30% in developed economies such as Europe and the United States (National Statistical Office of Thailand, 2024, August 18). This gap emphasizes the urgent need to investigate factors predicting INT among Thai engineering students.

Such an inquiry is meaningful for several reasons. First, engineering students possess high potential for creative thinking, information seeking, product development, and problem-solving, which are skills that directly contribute to entrepreneurship. This is supported by Ayalew and Zeleke (2018), whose findings indicated that entrepreneurial education and attitudes significantly predict students’ self-employment intentions. Likewise, Vodă and Florea (2019) found that opportunity seeking, creativity, problem-solving skills, and achievement motivation are strong predictors of students’ entrepreneurial intention.

Second, promoting entrepreneurship among engineering graduates can help generate new business ventures, reduce unemployment, and alleviate job placement pressure on both the government and universities. This is comparable to Otache et al. (2020) and Hanandeh et al. (2021), who emphasized entrepreneurship as a viable alternative to traditional employment and a means to mitigate economic challenges. Similarly, Wang et al. (2023) noted that university students tend to exhibit autonomous learning behaviors and openness to new experiences, making them more likely to engage in entrepreneurial intention.

Third, entrepreneurship education in engineering requires experiential learning through project-based and problem-based approaches. Students must engage with real-world challenges that demand persistence and time. Consistent with Gutierrez-Berraondo et al. (2025), implementation of problem- and project-based learning (P2BL) enables students to apply core engineering competencies to solve complex problems while deepening their conceptual understanding across related disciplines. Their findings also revealed that the development and application of engineering skills are gradual processes that evolve through continuous learning and practice.

Thus, research on entrepreneurial Intention (INT) using TPB has primarily focused on three key constructs: Attitude toward Behavior (ATD), self-efficacy (SEF), and social norms (SCN). Scholars across both developed and developing countries have shown considerable interest in this area, examining it from multiple disciplinary perspectives. For instance, Liñán and Chen (2009) explored cross-cultural differences in entrepreneurial attitudes and perceived capabilities between Spain and Taiwan, while Tessema Gerba (2012) investigated the impact of entrepreneurship education on the intentions of business and engineering students in Ethiopia.

Past studies, like Bae et al. (2014), explored the roles of perceived feasibility and desirability in shaping entrepreneurial behavior. Fayolle and Gailly (2015) examined how entrepreneurship education programs influence students’ attitudes and intentions, finding that program effectiveness varied significantly based on students’ prior entrepreneurial experiences. The concept of Guerrero and Urbano (2012) holds that a meso-level analysis bridges macro- and micro-behavioral outcomes, emphasizing the critical roles of both formal institutional arrangements and informal cultural elements in shaping entrepreneurial university development. Similarly, Krueger (2017) emphasized that understanding the complex cognitive processes driving INT is more important than merely studying new business creation. Nabi et al. (2017) further highlighted the importance of social learning processes and networking in fostering entrepreneurial behavior, particularly by encouraging creativity, innovation, and opportunity recognition.

Subsequent studies continued to encourage the importance of TPB constructs in INT. Alam et al. (2019) found that both attitude and perceived behavioral control positively influence INT, and entrepreneurial motivation significantly strengthens the link between intention and behavior, representing a meaningful extension of the TPB framework. In contrast, Niu et al. (2022) reported that self-efficacy is the strongest antecedent of entrepreneurial intention, with social support exerting a direct and significant effect, while the direct influence of creativity on intention appeared marginal.

Context-specific differences have also been documented. Wang et al. (2023) observed significant gender-based differences in INT among Chinese college students, as well as differences based on family business experience. Tiberius and Weyland (2023) examined the impact of digital technologies on 21st-century INT, highlighting the evolving role of technological competence in shaping entrepreneurial behavior. Coherent with Wright and colleagues’ conceptualization, their work emphasizes the diverse mechanisms that commercialize knowledge and foster entrepreneurial behavior among faculty and students (Siegel & Wright, 2015). Meanwhile, Kurata et al. (2025) investigated INT among engineering students in Japan, indicating that attitude and self-efficacy exert a strong influence, with notable differences between second- and fourth-year students. Their findings suggest that combining project-based and theory-based learning approaches is essential to comprehensively nurture the knowledge, skills, and mindset required for entrepreneurial intention. Most recently, Xanthopoulou and Sahinidis (2024) found that experiential learning and team-based activities significantly enhanced students’ knowledge of and enthusiasm for social entrepreneurship, indicating that practical, collaborative methods can effectively stimulate both entrepreneurial competence and motivation.

Based on the literature review, previous theories and empirical studies over the years reveal that (INT) is a complex, multidisciplinary phenomenon influenced by educational, socio-cultural, psychological, and technological factors. Consequently, it is necessary to explore additional dimensions that may extend the basic (TPB) framework, such as (ENR) and (EPL), particularly within the Thai cultural context. These factors can provide insights into the drivers of entrepreneurial intention among engineering students.

This approach is comparable to the strategies of King Mongkut’s University, which has implemented technology-based business incubation programs to cultivate entrepreneurial skills and foster the Sustainable Entrepreneurial University (Business Incubation Center (BIC) KMUTT, 2022). It is consistent with the concept of the Triple Helix Model proposed by Etzkowitz and Leydesdorff, which explains innovation dynamics through interactive collaboration among universities, industry, and government. Institutional roles increasingly overlap to support knowledge-driven development. Within this framework, the university evolves into an entrepreneurial university and an innovative ecosystem (Etzkowitz, 2003), in line with Thailand’s 13th National Economic and Social Development Plan from year 2023 to 2027, which emphasizes technology- and innovation-based economic growth, as well as initiatives to promote student startups (Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council, 2022).

Despite these developments, research on INT among Thai engineering students integrating TPB with ENR and EPL by SEM is still new. Also, it remains limited and incomplete. Such an investigation could offer valuable benefits to both government agencies and universities by elucidating behavioral factors that influence students’ entrepreneurial intentions after graduation. This understanding can enhance the effectiveness of entrepreneurship training programs, modernize curricula, guide policymakers to support funding, tax incentives, and entrepreneurship-related knowledge, and ultimately reduce unemployment and social inequality. Moreover, fostering an ethical entrepreneurial environment and education system can develop both sustainable economic growth and strengthen Thailand’s economic innovation.

Based on the above discussion, this study asks the following research questions and objectives:

1.1. Research Questions

- To what extent do (ATD), (SEF), and (EPL) directly influence (INT) among Thai engineering students?

- To what extent do (SCN) and (ENR) indirectly influence (INT) through mediators such as ATD and SEF?

- Which factors exert the most significant influence on (INT) among Thai engineering students, as analyzed using (SEM)?

1.2. Research Objectives

- Identify the direct effects of (ATD), (SEF), and (EPL) on (INT) among Thai engineering undergraduate students.

- Analyze the indirect effects of (SCN) and (ENR) on (INT), mediated by (ATD) and (SEF).

- Examine the factors that exert the most significant influence on (INT) among Thai engineering undergraduate students using (SEM).

This study’s structure is as follows: Section 2, Literature Review and Hypothesis Development; Section 3, The Conceptual Framework. Research Methodology and Results are described in Section 4 and Section 5, while Section 6 present the Discussion, including limitations and recommendations for future research. Finally, the Conclusion for Section 7.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Theoretical Foundation: TPB and Hypotheses Development

TPB has proven to be a deep framework for predicting entrepreneurial intentions and understanding the psychological factors that drive individuals to engage in entrepreneurial activities. According to Bird (1988), personal factors, perceived capabilities, and environmental influences collectively shape an individual’s entrepreneurial decision-making process. Moreover, entrepreneurial intention reveals a person’s internal commitment toward starting a new business. Building on this, Ajzen (1991) developed the TPB, which posits that an individual’s intention to perform a specific behavior can be accurately predicted by three key components: attitude toward the behavior (ATD), social norms (SCN), and perceived self-efficacy (SEF). Attitude reflects an individual’s positive or negative evaluation of performing a behavior. Social norms capture the influence of others or reference groups on the individual’s belief about whether to engage in the behavior. Self-efficacy represents the perceived ease of the difficulty of performing the behavior and the confidence in one’s ability to succeed.

Prior studies have supported TPB as a strong framework for investigating entrepreneurial intention across diverse contexts. Liñán and Chen (2009), Fayolle et al. (2014), and Krueger (2017) highlighted research gaps in the intention–behavior link, particularly concerning cross-cultural differences in attitudes and perceived capabilities that influence entrepreneurial intention. Similarly, recent studies by Tiberius and Weyland (2023) and Rosário and Raimundo (2024) confirmed the varied applicability of TPB across various professional disciplines, demonstrating its relevance for contemporary entrepreneurship research in the context of a dynamic and sustainable economy. Further, Vasilescu et al. (2025) and Csákné Filep et al. (2025) emphasized that TPB continues to be a highly influential and challenging model for studies in both developed and developing countries. As a result, from the above research framework, this study was required to investigate TPB constructs in the context of engineering students in Thailand.

Within TPB, the concept of (ATD) refers to an individual’s positive or negative evaluation of engaging in entrepreneurial behavior. This includes beliefs, thoughts, and judgments regarding the desirability and appropriateness of entrepreneurship or business ownership. Initially developed by Fishbein and Ajzen (1975). Attitude is influenced by personal beliefs and the encouragement of others, rooted in social psychology. Ajzen (1991) and Ajzen and Fishbein (2000) applied this concept to entrepreneurship, highlighting that attitudes toward entrepreneurship reflect beliefs about potential outcomes, such as wealth, autonomy, and risk, as well as the perceived value of these outcomes in guiding behavior. Krueger et al. (2000) systematically applied TPB to INT, providing empirical support for the relationship between attitude and entrepreneurial behavior.

More recent research confirms that entrepreneurial education positively influences both attitude and INT. Studies by Fayolle and Gailly (2015), Tiberius and Weyland (2023), and Csákné Filep et al. (2025) demonstrated that structured entrepreneurship education programs enhance participants’ attitudes toward entrepreneurship, strengthen intentions to engage in entrepreneurial activities, and positively shape past entrepreneurial experiences. Based on these studies, the first hypothesis (H1) is proposed:

H1.

(ATD) has a direct influence on (INT).

With the TPB framework, self-efficacy (SEF) refers to an individual’s confidence in their ability to perform tasks successfully to achieve specific goals under certain circumstances. Levels of (SEF) vary depending on the behavior or intention being considered. Bandura (1997) first introduced and developed the concept of SEF as an individual’s assessment of their capability to plan and execute actions to accomplish a particular objective. Bandura also noted that entrepreneurship education enhances perceived self-efficacy, providing individuals with a greater likelihood of engaging in entrepreneurial activities.

However, Adeniyi (2023) found that while entrepreneurship education is associated with SEF, only some aspects of education mediate the relationship between entrepreneurial training and readiness for business startups. Similarly, a study by Ferreira-Neto et al. (2023) demonstrated that self-efficacy in management roles significantly influences entrepreneurial passion and creativity in developing entrepreneurial competencies. Wang et al. (2023) highlighted that perceived entrepreneurial self-efficacy plays a fully mediating role in fostering entrepreneurial intention. Consistent with Martín-Gutiérrez et al. (2023), entrepreneurship education is considered a critical value in 21st-century society, as it facilitates the development and growth of young populations. Their model emphasizes enhancing self-efficacy and personal initiative as key precursors to entrepreneurial behavior.

Furthermore, Anjum et al. (2021) and Ye and Kang (2025) examined relationships among entrepreneurial skills (ES), entrepreneurial attitude (EA), and entrepreneurial self-efficacy (ESE) as psychological predictors of INT. Their structural equation modeling results revealed that both ES and ESE positively affect INT, with ESE exerting the strongest influence among the variables. Additionally, ESE significantly influenced EA only in groups without formal entrepreneurship education (EE). Based on the above discussion, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2.

(SEF) has a significant positive direct effect on (INT).

Within the TPB framework, social norms (SCN) refer to an individual’s perception of the expectations of significant others regarding whether they should or should not perform a specific behavior. It reflects how family, friends, teachers, or the surrounding social environment view an individual’s intention to engage in entrepreneurial activities. Ajzen (1991) suggested that the relationship between social norms and entrepreneurial attitude varies across cultures, and differing SCN can influence attitudes toward entrepreneurship (ATD).

However, Liñán and Chen (2009) and Fayolle et al. (2014) found that attitude (ATD) is a more significant predictor of entrepreneurial intention (INT) than social norms alone. Nonetheless, research indicates that (SCN) can exert indirect effects on entrepreneurial intention through mediators such as ATD and self-efficacy (SEF). For example, Mgueraman (2025) found that entrepreneurship education indirectly influences INT among engineering students through attitude (ATD), subjective norms (SCN), and perceived behavioral control (PBC), with significant positive effects. Similarly, Xu and Lee (2025) reported that (SCN) indirectly affects (INT) through (ATD), especially when shaped by entrepreneurship education in the service sector. This is comparable to Chaudhary and Biswas (2024), who confirmed that while SCN does not have a direct effect on INT, it enhances INT indirectly via ATD, increasing students’ entrepreneurial intentions. From these findings, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H3.

(SCN) has a direct effect on (ATD).

H4.

(SCN) has a direct effect on (SEF).

H5.

(SCN) has an indirect effect on (INT) through (ATD) and (SEF).

Overall, numerous studies emphasize that TPB is a suitable framework for analyzing human behavior to predict whether individuals will engage in a specific action, based on attitudes (ATD), self-efficacy (SEF), and social norms (SCN) perceived from significant others, which collectively influence behavioral intention (Ajzen, 1991). TPB has been widely recognized as more suitable than Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) (Bandura, 1997) and the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975) for studying entrepreneurial intention and has been applied in both developed and developing countries, including Thailand (Krueger et al., 2000; Schlaegel & Koenig, 2014).

Consequently, from the above discussion, this study extends the TPB framework by incorporating (ENR) and (EPL) as additional factors influencing the INT of Thai engineering students, as detailed in the following sections.

2.2. Extensions: (ENR) and (EPL) Direct and Indirect Effects on INT and Hypotheses Development

Entrepreneurial Network Relations (ENR) refer to networks of colleagues, organizations, and business connections that play a crucial role in promoting entrepreneurial intentions. Zimmer (1986) highlighted that ENR consists of social relationships and linkages among individuals that allow entrepreneurs to access resources, information, opportunities, and support necessary for starting and running a business.

Consistent with Farooq et al. (2018), research on the relationship between perceived social support (SS) from social networks and entrepreneurial intention (EI) found that the effects of mediation through other TPB constructs, such as attitude toward entrepreneurship (ATD), subjective norms (SN), and perceived behavioral control (PBC), are significant predictors of INT. Similarly, Chen et al. (2024) reported that SEM analysis showed online social network relationships significantly affect sustainable entrepreneurial capital. Their study provides new insights into how entrepreneurs can leverage online social network connections to achieve entrepreneurial success. However, Wasim et al. (2024) found that social networks are crucial in promoting entrepreneurial learning, but in contexts where networks act as learning mechanisms, these elements are often overlooked in traditional entrepreneurship education approaches.

Based on this literature, this study aims to extend the TPB model by examining the direct effects of ENR on attitude (ATD) and self-efficacy (SEF), as well as the indirect effect of ENR on entrepreneurial intention (INT) through ATD and SEF among Thai engineering students. From these studies, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H6.

(ENR) has a direct effect on (ATD).

H7.

(ENR) has a direct effect on (SEF).

H8.

(ENR) has an indirect effect on (INT) through (ATD) and (SEF).

Entrepreneurship Policy (EPL) refers to policies that have a direct effect on entrepreneurial intention (INT). EPL encompasses government measures, guidelines, and actions aimed at promoting, supporting, and stimulating entrepreneurship and the growth of new businesses in the country. This includes creating environments and opportunities conducive to entrepreneurship. Lundström and Stevenson (2005) stated that public policies established by governments or organizations support the creation and growth of entrepreneurs, covering education, regulations, innovation infrastructure, and the business environment.

Furthermore, Braunerhjelm and Henrekson (2023) highlighted that innovation and entrepreneurship policies should focus on general measures to establish a foundation for creating environments that facilitate the development of innovative, high-growth companies. Innovation and entrepreneurship policies help unlock the innovative potential of society. Recent research by Ríos Yovera et al. (2025) indicated that these findings provide theoretical insights and practical recommendations for policymakers and university administrators, aiming to enhance the design and implementation of effective entrepreneurial ecosystems. This study contributes to a deeper understanding of mechanisms and strategies that enable universities to act as catalysts for innovation and sustainable economic growth.

Additionally, taxation and funding policies are key motivators for investing in business creation. Consistent with the Board of Investment Thailand (Board of Investment (BOI), 2024), investment promotion policies provide tax exemptions for startups by students with innovative, commercially applicable inventions. Based on the literature above, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H9.

(EPL) has a direct effect on (INT).

3. Conceptual Framework

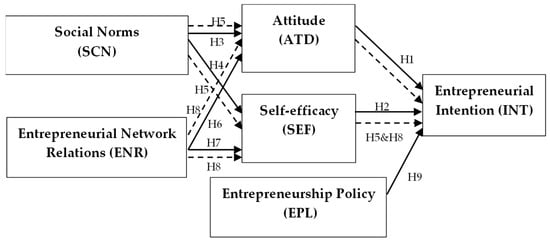

The conceptual framework is adapted from the TPB. It uses SEM to analyze the variables of attitude (ATD), self-efficacy (SEF), and Entrepreneurship Policy (EPL), which have a direct effect on entrepreneurial intention (INT), and to study the indirect variables of social norms (SCN) and Entrepreneurial Network Relations (ENR), which influence INT through ATD and SEF of Thai engineering students.

This framework is based on Ajzen (1991), Liñán and Chen (2009), Schlaegel and Koenig (2014), Wasim et al. (2024), Braunerhjelm and Henrekson (2023). The conceptual framework is presented in detail in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework based on the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1991; Liñán & Chen, 2009; Schlaegel & Koenig, 2014).

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Population

The population for this study comprised fourth-year undergraduate students enrolled in engineering and technology programs during the first semester of the 2024 academic year at eight universities in Thailand, including both public and private institutions. The selected universities were Burapha University, Kasem Bundit University, Assumption University (ABAC), King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi (Bangmod and Bangkhuntien campuses), Chulalongkorn University, King Mongkut’s Institute of Technology Ladkrabang (KMITL), and Rajamangala University of Technology Thanyaburi.

4.2. Sample Group

The sample consisted of 420 volunteer final-year undergraduate students from engineering and technology programs. Convenience sampling was employed online due to practical constraints in accessing multiple campuses, and this method is also a regular research approach worldwide. After the Dean approved the request letter, we sent it to the engineering classroom teachers at various universities, whom we had previously trained to explain the purpose of the research and questionnaire. Then, request assistance in collecting data from students, which was voluntary, and completed from June 28 to 31 August 2024. The sample size met the minimum requirement for SEM analysis, calculated as 15 participants per observed variable (28 × 15 = 420), ensuring adequate statistical significance by Hair et al. (2010).

4.3. Research Instrument

Data was collected using a self-administered questionnaire distributed via Google Forms. The questionnaire provides 28 observed variables, and each measurement is on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The measurement items were adapted from validated instruments. (ATD) was measured using five questions by Ajzen (1991). (SEF) with five questions with Bandura (1997). (SCN) by four questions for Krueger (2017). (INT) with six questions by Liñán and Chen (2009). (ENR) with four questions by Farooq et al. (2018). And (EPL) with four questions by Lv et al. (2021) and Lundström and Stevenson (2005). Content validity was assessed using the Item-Objective Congruence (IOC) index, with all items exceeding 0.60. The average IOC in this study was 0.864, indicating that the questionnaire had high reliability and was suitable for the research.

4.4. Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of (KMUTT-IRB-COE-2024-144) on 30 May 2024. Participation was voluntary, and all respondents completed the questionnaire online. All participants’ information was deidentified; no participant consent was required. Moreover, all data was not shared with third parties.

4.5. Data Analysis

The data collected were analyzed using LISREL Version 8.72. Examination included Pearson’s correlation coefficient, Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity, Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure, factor loadings, model fit indices, and reliability analysis. Hypotheses were tested using standardized path coefficients (β) to evaluate direct, indirect, and total effects. structural equation modeling (SEM) was employed to determine the relationships between all variables.

5. Results

A. Study of factors influencing entrepreneurial intention for Thai engineering students using SEM. The study is presented in two parts as follows:

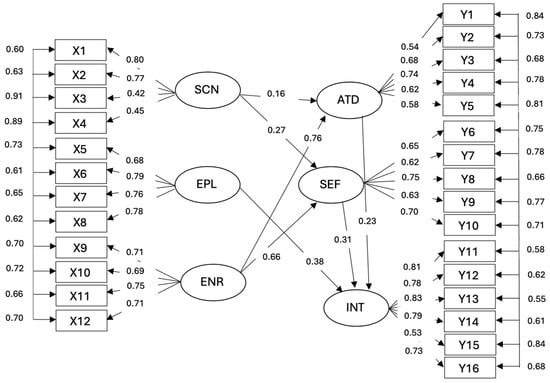

- The factors influencing (INT) among engineering students in Thailand consist of six components with a total of 28 indicators. Component 1 (ATD) includes five indicators: perceived value (Y1), motivation (Y2), challenge (Y3), enjoyment (Y4), and sense of ownership (Y5). Component 2 (SEF) includes five indicators: effort (Y6), perseverance (Y7), ability (Y8), confidence (Y9), and opportunity creation (Y10). Component 3 (INT) includes six indicators: readiness (Y11), goals (Y12), planning (Y13), commitment (Y14), business expansion (Y15), and experience (Y16) for starting a new business. Component 4 (SCN) includes four indicators: personal expectation (X1), positive attitude (X2), social expectation (X3), and social advice (X4). Component 5 (EPL) includes four indicators: generating interest (X5), funding support (X6), training (X7), and continuous assistance (X8). Component 6 (ENR) includes four indicators: entrepreneur network (X9), network confidence (X10), opportunity creation (X11), and business risk (X12).

- The model fit of the causal factors influencing entrepreneurial intention among engineering students in Thailand shows that most observed variables are correlated, with correlation coefficients ranging from 0.100 to 0.687. Considering Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity, which tests whether the correlation matrix is an identity matrix, the result was 6430.757 (p = 0.000), indicating that the correlation matrix of the observed variables significantly differs from an identity matrix at the 0.01 level. This is comparable to the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy (KMO), which Nkansah (2018) reported as 0.947, close to 1, suggesting that the variables in this dataset are highly correlated and suitable for factor analysis.

From Table 1, the analysis of correlation coefficients among the observed variables shows that most variables are correlated, with coefficients ranging from 0.100 to 0.687. Considering Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity, which tests the hypothesis that the correlation matrix is an identity matrix, the statistic equals 6430.757 (p = 0.000). This indicates that the correlation matrix of the observed variables is significantly different from an identity matrix at the 0.01 significance level. This result is consistent with the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy (KMO) (Nkansah, 2018), which equals 0.947, approaching a value of 1.0. This shows that the variables in this dataset are highly correlated and suitable for analysis, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Pearson correlation coefficients of variables in causal models of factors influencing entrepreneurial intention for engineering students in Thailand.

B. Analyze the Causal Model Fit Influencing INT of Engineering Students in Thailand

According to Table 2, the results of the causal model fit assessment indicate a very good fit with the empirical data. This can be seen from the chi-square value (χ2 = 183.31, df = 224, p = 0.98), which has a probability greater than 0.05, indicating that the null hypothesis is not rejected, and that the theoretically developed model is consistent with the empirical data. The Goodness-of-Fit Index (GFI) is 0.97, and the Adjusted Goodness-of-Fit Index (AGFI) is 0.95, values that are 1 or close to 1. The Root Mean Square Residual (RMR) is 0.031, and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) is 0.000, a value close to zero. The details are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

The result of the causal model fit with influencing entrepreneurial intention of engineering students in Thailand.

From Table 3, the results of the analysis of the effect sizes between variables and the testing of hypotheses are presented as follows:

Table 3.

The analysis results of the direct and indirect effect sizes among variables and their consistency with the proposed hypotheses.

(ATD) had a direct effect on (INT), with an effect size of 0.23, which was statistically significant at the 0.05 level. This finding indicates that students with a higher level of attitude toward entrepreneurship tend to have a stronger intention to become entrepreneurs. The analysis result is consistent with Hypothesis H1.

(SEF) had a direct effect on (INT), with an effect size of 0.31, which was statistically significant at the 0.05 level. This demonstrates that students who possess higher levels of perceived self-efficacy tend to have a greater intention to become entrepreneurs. The analysis result is consistent with Hypothesis H2.

(SCN) had a direct effect on (ATD), with an effect size of 0.16, indicating that students with stronger social norms tend to have more positive attitudes toward entrepreneurship. In addition, SCN had a direct effect on SEF, with an effect size of 0.27, which was statistically significant at the 0.05 level. This result shows that students with higher levels of social norms tend to perceive themselves as having greater ability or confidence in their entrepreneurial capabilities. The analysis result is consistent with Hypotheses H3 and H4.

(SCN) had an indirect effect on (INT) through the mediating variables ATD and SEF, with an indirect effect size of 0.12, which was statistically significant at the 0.05 level. This means that students with higher levels of social norms tend to have higher attitudes and greater self-efficacy. When ATD and SEF increase, students’ entrepreneurial intentions also increase accordingly. The analysis result is consistent with Hypothesis H5.

(ENR) had a direct effect on (ATD) toward entrepreneurship, with an effect size of 0.76, which was statistically significant at the 0.05 level. This finding indicates that students with stronger entrepreneurial networks tend to develop more positive attitudes toward entrepreneurship. Furthermore, (ENR) had a direct effect on SEF, with an effect size of 0.66, showing that students with stronger entrepreneurial network relationships tend to have higher levels of self-efficacy toward entrepreneurship. The analysis result is consistent with Hypotheses H6 and H7.

(ENR) had an indirect effect on (INT) through the mediating variables ATD and SEF, with an indirect effect size of 0.38, which was statistically significant at the 0.05 level. This demonstrates that students with stronger entrepreneurial network relationships tend to have higher attitudes and greater self-efficacy, which in turn lead to a higher intention to become entrepreneurs. The analysis result is consistent with Hypothesis H8.

(EPL) had a direct effect on (INT), with an effect size of 0.38, which was statistically significant at the 0.05 level. This indicates that students with higher perceptions or awareness of entrepreneurial policies tend to have a stronger intention to become entrepreneurs. The analysis result is consistent with Hypothesis H9.

Therefore, the overall findings revealed that all hypotheses (H1–H9) were statistically supported. Complete details are presented in Table 3.

From Table 4, when considering the reliability values of the observed variables, it was found that most of the observed variables demonstrated acceptable reliability levels, ranging from 0.17 to 0.70. When examining the coefficient of determination (R2) of the structural equation model for the endogenous and mediating variables, namely ATD (R2 = 0.78), SEF (R2 = 0.77), and INT (R2 = 0.69), it was revealed that the predictor or causal factors—(SCN) and (ENR) which jointly explained 78 percent of the variance in attitude toward entrepreneurship (ATD). Similarly, the predictor or causal factors SCN and ENR together explained 77 percent of the variance in self-efficacy (SEF). Furthermore, the predictors or causal factors, namely (ATD) and (SEF), jointly explained 69 percent of the variance in entrepreneurial intention (INT). Details are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Reliability values and coefficients of determination (R2) of the structural equation model (SEM).

From Table 5, when examining the correlation matrix among the six latent variables, it was found that the correlations ranged from 0.66 to 0.87. The pair with the highest correlation (ATD) and (ENR), with a correlation coefficient of 0.87. The second highest correlation between ENR and SEF, with a coefficient of 0.85, followed by the correlation between ENR and EPL, with a coefficient of 0.77, respectively. Details are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Correlation matrix among the six latent variables.

From Figure 2, when considering the magnitude of the effects of variables influencing entrepreneurial intention, the results can be ranked from the highest to the lowest as follows. (EPL) had the strongest direct effect on (INT), with an effect size of 0.38. Entrepreneurial network relationships (ENR) had an indirect effect on INT through the mediating variables (ATD) and (SEF), with an indirect effect size of 0.38. Following this, self-efficacy (SEF) had a direct effect on entrepreneurial intention, with an effect size of 0.31. (ATD) had a direct effect on entrepreneurial intention, with an effect size of 0.23. Lastly, social norms (SCN) had an indirect effect on entrepreneurial intention through ATD and SEF, with an indirect effect size of 0.12, respectively. Details are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The causal model of factors influencing entrepreneurial intention among engineering students in Thailand (p < 0.05).

6. Discussion

This is the first study to extend the TPB by incorporating two additional factors, (ENR) and (EPL), by SEM to examine their direct and indirect influences on the enhancement of INT among Thai engineering students. It makes four key contributions to the literature on INT.

First, analysis of SEM shows that all hypotheses (H1–H9) were statistically supported and consistent with the empirical data. The findings reveal that all five factors had statistically significant effects on INT at the 0.05 level (p < 0.05). The variables influencing INT from the highest to the lowest effect are as follows: EPL had the strongest direct effect on INT with β = 0.38; ENR exerted an indirect effect on INT through the mediating variables (ATD) and (SEF), with β = 0.38; SEF had a direct effect on INT with β = 0.31; ATD had a direct effect on INT with β = 0.23; and SCN had an indirect effect on INT through ATD SEF, with β = 0.12, respectively. These findings are consistent with the TPB, which posits that (ATD), (SEF), and (SCN) are key determinants that directly influence INT. The results match with previous studies by Ajzen (1991), Liñán and Chen (2009), and Schlaegel and Koenig (2014), also in agreement with other research emphasizing that attitude, social norms, and self-efficacy have significant positive effects on INT. (Bae et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2023; Tiberius & Weyland, 2023). Furthermore, this study contributes to research by demonstrating that the contextual factors, EPL and ENR, with β = 0.38, suggest that perceptions of policy support and access to ENR can more effectively predict INT, particularly within the context of entrepreneurship education for Thai engineering students. These findings challenge the traditional application of TPB, which often treats psychologically perceived internal factors as objective situational moderators to promote INT rather than external factors. This approach differs from previous studies in Western economies (Bae et al., 2014; Nabi et al., 2017), which found that research on the effects of entrepreneurship education often focused on short-term outcomes and subjective self-assessments that could not be directly measured or observed externally, like EPL and ENR. Those studies also reported that the relationship between entrepreneurship education and post-education entrepreneurial intention was statistically insignificant.

Second, some of the results of this study are consistent with previous research indicating that (ENR) has a significant indirect effect on (INT) through (ATD) and (SEF), with β = 0.38. This reflects strong entrepreneurial networks that provide students not only with opportunities but also with confidence, courage, and emotional reinforcement. Engineering students with higher levels of ENR tend to develop more positive attitudes and higher self-efficacy toward entrepreneurship. Comparable the idea that ENR enables students to access business opportunities and better handle entrepreneurial challenges (Zimmer, 1986). These findings are also consistent with Farooq et al. (2018), who found that perceived social support positively influences INT, and that this relationship is fully mediated by attitude toward entrepreneurship, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. In other words, social support shapes INT indirectly through the key psychological constructs emphasized in TPB. Similarly, Baron and Markman (2003) highlighted that aspects of social competence, such as accuracy in perceiving others, were positively related to financial success for entrepreneurs. These results are consistent with Anwar and Saleem (2021), who reported that TPB traits and underlying factors have a direct and positive relationship with INT. Entrepreneurial traits were found to significantly affect ATD and SEF directly, while also having a significant indirect effect on INT through these mediators. Furthermore, the findings match those of Murad et al. (2025), who reported that ENR significantly influences scientists’ academic INT. Overall, this study confirms that ENR plays a crucial role in enhancing INT, both directly by shaping students’ perceptions and indirectly through its influence on ATD and SEF, supporting and extending previous empirical findings in the field.

Third, the study indicates that (EPL) is the factor with the strongest direct effect on (INT), with β = 0.38. This suggests that supportive policies, funding, continuous assistance for technological innovations, and business mentoring programs can effectively stimulate engineering students’ INT. These findings are consistent with prior research by Li et al. (2025), which demonstrated that entrepreneurship education and government policies are the core elements driving business model innovation. The results also match with Guo et al. (2022), who found that (EPL) support significantly moderates the mediated relationship between improvisation and INT through (SEF). Similarly, Huang et al. (2021) reported significant positive relationships between (EPL) and INT. Furthermore, this study corresponds with strategies implemented by King Mongkut’s University, which launched a technology business incubation program to advance the concept of a Sustainable Entrepreneurial University, fostering entrepreneurial skills and intentions among students (Business Incubation Center (BIC) KMUTT, 2022) The findings also support governmental policies and infrastructure that promote entrepreneurship, particularly startup initiatives for engineering students, including tax incentives and long-term funding support by startup promotion plan for Thai student (Board of Investment (BOI), 2024). Overall, the results underscore the importance of learning, which is the key to growth and success, therefore supporting the strengthening of students’ INT. Emphasizing both the educational and policy implications for promoting sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystems in higher education is most necessary.

Lastly, the study’s integration of (EPL) and (ENR) into the TPB framework provides both theoretical and practical significance in understanding the factors that influence INT among Thai engineering students. Therefore, this study’s conclusions highlight (1) Human Development Dimensions: developing students’ foundational skills and entrepreneurial competencies through experiential learning. Universities should establish business simulation centers (Damme Company) to enhance students’ leadership, communication, motivation, strategic planning, opportunity recognition, and problem-solving abilities, while instilling a sense of social network value creation. Entrepreneurial education curricula should be continuously improved for engineering students and faculty. Recommended to establish Entrepreneurial Education Clubs focused on developing entrepreneurial skills and mentorship programs that emphasize real startup ventures. (2) Policymakers: simplify complex business registration processes, provide training to support students in understanding government-supported policies, including funding opportunities, tax incentives, and establish innovation centers for commercializing engineering technologies (Entrepreneurial Engineering Innovation for Commercialization). (3) Industry and Community Engagement: develop social learning hubs and networking platforms connecting students, faculty, entrepreneurs, and investors. Supporting business networking activities, problem-solving workshops, and creating ecosystems that enable students to initiate real business ventures. This approach promotes sustainable economic development, reduces corruption, and fosters ethical entrepreneurial practices in Thailand.

Limitations

The study focuses exclusively on Thai graduate students, limiting cross-cultural generalizability. It is restricted to engineering faculty only, who may not be representative of all graduate students nationwide.

Future Research

Future research should investigate (1) cross-cultural validation of the extended TPB model across other faculties and universities. (2). Conduct cross-country comparisons within ASEAN.

7. Conclusions

This study found that EPL is the factor with the strongest direct effect on INT. Therefore, universities should focus on “enhancing psychological readiness and skills” by establishing programs such as an Entrepreneur Clinic for engineering students. This program could include coaching and workshop sessions, inviting successful young entrepreneurs as role models to foster risk-taking and build confidence. It would also grant training in essential entrepreneurial skills and conduct real business simulation exercises to prepare engineering students to become entrepreneurs. For the government, policies promoting entrepreneurship should be made tangible and easily accessible by supporting an “entrepreneurial ecosystem.” Examples include establishing a Startup Entrepreneurship Hub to facilitate co-creation between students and business professionals, organizing Startup Fairs in collaboration with governmental agencies such as NIA and DEPA (Digital Economy Promotion Agency (DEPA), 2023), and developing digital dashboards to display business opportunities and funding resources for pursuing entrepreneurship, consistent with practices in several developed countries, including Finland, Germany, and Singapore, which emphasize emotional and self-regulation dimensions in entrepreneurship education. For example, Aalto University in Finland trains students in risk-taking, adaptability, and an entrepreneurial mindset from early undergraduate years. Institutions in Germany and Singapore provide structured mentorship and incubation systems to familiarize students with policies and funding resources. Compared with Asian countries such as China and Korea, the findings confirm that entrepreneurship education is a key determinant of entrepreneurial performance. It not only directly enhances entrepreneurial performance, but it also, in conjunction with government policies, indirectly influences it through the mediating variable of business model innovation in China (Li et al., 2025). Meanwhile, Byun et al. (2018) noted that improvements of entrepreneurship programs are based on evaluations by students and graduates. It emphasizes developing programs with post-graduation support and continuous field research to advance the entrepreneurship curriculum in Korea. The current study, similar to Farooq et al. (2018), Anwar and Saleem (2021), and Xu and Lee (2025), revealed that social support, traits, and underlying factors contribute to TPB, which has a direct and positive relationship to INT. It is recommended that promoting entrepreneurial education and skills for students is significant and relevant for supporting emerging economies in developing countries.

Finally, these measures are essential to strengthen the entrepreneurial ecosystem and the intention of Thai engineering students. This phenomenon is not only an educational development but also a critical mechanism for driving growth across multiple dimensions. Systematic understanding and support of this phenomenon will generate sustainable benefits for human development, society, and the nation. Those will build an ecosystem conducive to promoting entrepreneurial intention, especially innovation and technology commercialization for engineering students. It will also foster the growth of new generation entrepreneurs, reduce unemployment, and drive the national economy forward.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.W. and M.N.; Methodology, P.W. and T.T.; Software, P.W. and S.S.; Validation, P.W. and M.N.; Formal analysis, P.W. and T.T.; Investigation, P.W. and M.N.; Resources, P.W. and T.T.; Data curation, P.W. and T.T.; Writing-original draft preparation, P.W.; writing—review and editing, P.W., T.T. and M.N. Visualization, P.W. and S.S. Supervision, P.W. and T.T.; Project administration, P.W. and T.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by Human Research Ethics Committee of King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi (KMUTT-IRB-COE-2024-144).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data is not publicly available due to privacy or ethical reasons.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abdelmagid, A. S., Jabli, N. M., Al-Mohaya, A. Y., & Teleb, A. A. (2025). Integrating interactive metaverse environments and generative artificial intelligence to promote the green digital economy and e-entrepreneurship in higher education. Sustainability, 17(12), 5594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeniyi, A. O. (2023). The mediating effects of entrepreneurial self-efficacy in the relationship between entrepreneurship education and start-up readiness. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 10(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (2000). Attitudes and the attitude–behavior relation: Reasoned and automatic processes. European Review of Social Psychology, 11(1), 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M. Z., Kousar, S., & Rehman, C. A. (2019). Role of entrepreneurial motivation on entrepreneurial intentions and behaviour: Theory of planned behaviour extension on engineering students in Pakistan. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 9(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, T., Heidler, P., Amoozegar, A., & Anees, R. T. (2021). The impact of entrepreneurial passion on the entrepreneurial intention: Moderating impact of perception of university support. Administrative Sciences, 11(2), 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, I., & Saleem, I. (2021). Traits and entrepreneurial intention: Testing the mediating role of entrepreneurial attitude and self-efficacy. Journal for International Business and Entrepreneurship Development, 13(1), 40–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D. B., & Belitski, M. (2021). Three-ring entrepreneurial university: In search of a new business model. Studies in Higher Education, 46(11), 2380–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayalew, M. M., & Zeleke, S. A. (2018). Modeling the impact of entrepreneurial attitude on self-employment intention among engineering students in Ethiopia. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 7(1), 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, T. J., Qian, S., Miao, C., & Fiet, J. O. (2014). The relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions: A meta-analytic review. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(2), 217–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W. H. Freeman. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1997-08589-000 (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Baron, R. A., & Markman, G. D. (2003). Beyond social capital: The role of entrepreneurs’ social competence in their financial success. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(1), 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, B. (1988). Implementing entrepreneurial ideas: The case for intention. Academy of Management Review, 13(3), 442–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Board of Investment (BOI). (2024). Thailand investment promotion policy handbook 2023. Thailand Board of Investment. Available online: https://www.boi.go.th (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Braunerhjelm, P., & Henrekson, M. (2023). Tax policy to stimulate innovation and entrepreneurship. In Unleashing society’s innovative capacity: An integrated policy framework (pp. 145–165). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Business Incubation Center (BIC) KMUTT. (2022). Annual report on technology business incubation programs 2023. King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi. Available online: https://www.smeone.info/public/index.php/service-center-lists/34/157 (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- Byun, C. G., Sung, C. S., Park, J. Y., & Choi, D. S. (2018). A study on the effectiveness of entrepreneurship education programs in higher education institutions: A case study of Korean graduate programs. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 4(3), 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, M., & Biswas, A. (2024). Igniting the flames of entrepreneurial intentions: Unravelling the dynamics of perceived business feasibility, self-perceived altruism, innovativeness and uncertainty among university students. Global Business Review. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., Ma, Y., & Xie, Y. (2024). The influence mechanism of online social network relationships on sustainable entrepreneurial success. Sustainability, 16(9), 3755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csákné Filep, J., Timár, G., & Szennay, Á. (2025). Analysing the impact of entrepreneurship education on early-stage entrepreneurship—Focusing on the transitional countries of Central and Eastern Europe. Administrative Sciences, 15(2), 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diepolder, C. S., Weitzel, H., & Huwer, J. (2024). Exploring the impact of sustainable entrepreneurial role models on students’ opportunity recognition for sustainable development in sustainable entrepreneurship education. Sustainability, 16(4), 1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digital Economy Promotion Agency (DEPA). (2023). Student startup promotion report 2023. DEPA Thailand. Available online: https://www.depa.or.th/en/student-startup (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Dote-Pardo, J., Ortiz-Cea, V., Peña-Acuña, V., Severino-González, P., Contreras-Henríquez, J. M., & Ramírez-Molina, R. I. (2025). Innovative entrepreneurship and sustainability: A bibliometric analysis in emerging countries. Sustainability, 17(2), 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzkowitz, H. (2003). Innovation in innovation: The Triple Helix of university–industry–government relations. Social Science Information, 42(3), 293–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M. S., Salam, M., ur Rehman, S., Fayolle, A., Jaafar, N., & Ayupp, K. (2018). Impact of support from social network on entrepreneurial intention of fresh business graduates: A structural equation modelling approach. Education + Training, 60(4), 335–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayolle, A., & Gailly, B. (2015). The impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial attitudes and intention: Hysteresis and persistence. Journal of Small Business Management, 53(1), 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayolle, A., Liñán, F., & Moriano, J. A. (2014). Beyond entrepreneurial intentions: Values and motivations in entrepreneurship. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 10(4), 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira-Neto, M. N., de Carvalho Castro, J. L., de Sousa-Filho, J. M., & de Souza Lessa, B. (2023). The role of self-efficacy, entrepreneurial passion, and creativity in developing entrepreneurial intentions. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1134618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero, M., & Urbano, D. (2012). The development of an entrepreneurial university. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 37(1), 43–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R., Yin, H., & Lv, X. (2022). Improvisation and university students’ entrepreneurial intention in China: The roles of entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial policy support. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 930682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Berraondo, J., Iturbe-Zabalo, E., Arregi, N., & Guisasola, J. (2025). Influence on students’ learning in a problem- and project-based approach to implement STEM projects in engineering curriculum. Education Sciences, 15(5), 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Pearson Education. ISBN 978-0-13-813263-7. [Google Scholar]

- Hanandeh, R., Alnajdawi, S. M., Almansour, A., & Elrehail, H. (2021). The impact of entrepreneurship education on innovative start-up intention: The mediating role of entrepreneurial mind-sets. World Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development, 17(4), 856–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y., An, L., Wang, J., Chen, Y., Wang, S., & Wang, P. (2021). The role of entrepreneurship policy in college students’ entrepreneurial intention: The intermediary role of entrepreneurial practice and entrepreneurial spirit. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 585698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N. F. (2017). Entrepreneurial intentions are dead: Long live entrepreneurial intentions. In Revisiting the entrepreneurial mind: Inside the black box (pp. 13–34). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N. F., Reilly, M. D., & Carsrud, A. L. (2000). Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(5–6), 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurata, K., Kodama, K., Kageyama, I., Kobayashi, Y., & Lim, Y. (2025). Entrepreneurial intention among engineering students: The moderating role of entrepreneurship education in Japan. Behavioral Sciences, 15(5), 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z., Jintana, S., & Jotaworn, S. (2025). Empowering the next generation of entrepreneurs: Intersections of education, policy, and business model innovation. Cogent Education, 12(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F., & Chen, Y. (2009). Development and cross-cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3), 593–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundström, A., & Stevenson, L. A. (2005). Entrepreneurship policy: Theory and practice. Springer US. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y., Chen, Y., Sha, Y., Wang, J., An, L., Chen, T., Huang, X., Huang, Y., & Huang, L. (2021). How entrepreneurship education at universities influences entrepreneurial intention: Mediating effect based on entrepreneurial competence. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 655868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín-Gutiérrez, Á., Montoro-Fernández, E., & Dominguez-Quintero, A. (2023). Towards quality education: An entrepreneurship education program for the improvement of self-efficacy and personal initiative of adolescents. Social Sciences, 13(1), 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mgueraman, A. (2025). Entrepreneurship education’s main effects on engineering students’ entrepreneurial intentions in higher education institutions in Morocco. On the Horizon: The International Journal of Learning Futures, 33(3), 301–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murad, M., Zhao, J., Rasheed, M., Shah, S. H. A., Johri, A., & Islam, M. U. (2025). Bridging entrepreneurial networks and academic entrepreneurial behavior: Applying theory of planned behavior. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 21(1), 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, G., Liñán, F., Fayolle, A., Krueger, N., & Walmsley, A. (2017). The impact of entrepreneurship education in higher education: A systematic review and research agenda. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 16(2), 277–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambisan, S. (2017). Digital entrepreneurship: Toward a digital technology perspective of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41(6), 1029–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Statistical Office of Thailand. (2024). Available online: https://www.nso.go.th/ (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Niu, X., Niu, Z., Wang, M., & Wu, X. (2022). What are the key drivers to promote the entrepreneurial intention of vocational college students? An empirical study based on structural equation modeling. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1021969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkansah, B. K. (2018). On the Kaiser-Meier-Olkin’s measure of sampling adequacy. Mathematical Theory and Modeling, 8(7), 52–76. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/outputs/234680607/?source=oai (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council. (2022). The 13th national economic and social development plan (2023–2027). NESDC. Available online: https://www.nesdc.go.th/ewt_dl_link.php?nid=13412 (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Office of the Permanent Secretary for Higher Education, Science, Research and Innovation (MHESI). (2024). Available online: https://info.mhesi.go.th/#services (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Otache, I., Oluwade, D. O., & Idoko, E. O. J. (2020). Entrepreneurship education and undergraduate students’ self-employment intentions: Do paid employment intentions matter? Education + Training, 62(7/8), 741–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos Yovera, V. R., Ramos Farroñán, E. V., Arbulú Ballesteros, M. A., Vera Calmet, V. G., Aguilar Armas, H. M., Soto Deza, J. M., Redolfo, R. L., Acosta, R. M., & Reyes-Pérez, M. D. (2025). Academic entrepreneurship evolution: A systematic review of university incubators and startup development (2018–2024). Sustainability, 17(12), 5365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosário, A. T., & Raimundo, R. (2024). Sustainable entrepreneurship education: A systematic bibliometric literature review. Sustainability, 16(2), 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlaegel, C., & Koenig, M. (2014). Determinants of entrepreneurial intent: A meta-analytic test and integration of competing models. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(2), 291–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, D. S., & Wright, M. (2015). Academic entrepreneurship: Time for a rethink? British Journal of Management, 26(4), 582–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva León, P. M., Cruz Salinas, L. E., Farfán Chilicaus, G. C., Castro Ijiri, G. L., Chuquitucto Cotrina, L. K., Heredia Llatas, F. D., Farroñán, E. V. R., & Pérez Nájera, C. (2025). Digital technologies for young entrepreneurs in Latin America: A systematic review of educational innovations (2018–2024). Social Sciences, 14(9), 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessema Gerba, D. (2012). Impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intentions of business and engineering students in Ethiopia. African Journal of Economic and Management Studies, 3(2), 258–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiberius, V., & Weyland, M. (2023). Entrepreneurship education or entrepreneurship education? A bibliometric analysis. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 47(1), 134–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilescu, M. D., Crivoi, E. S., & Munteanu, A. M. (2025). Exploring entrepreneurial intention among European Union youth by education and employment status. PLoS ONE, 20(1), e0318001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vodă, A. I., & Florea, N. (2019). Impact of personality traits and entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intentions of business and engineering students. Sustainability, 11(4), 1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. H., You, X., Wang, H. P., Wang, B., Lai, W. Y., & Su, N. (2023). The effect of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intention: Mediation of entrepreneurial self-efficacy and moderating model of psychological capital. Sustainability, 15(3), 2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasim, J., Youssef, M. H., Christodoulou, I., & Reinhardt, R. (2024). The path to entrepreneurship: The role of social networks in driving entrepreneurial learning and education. Journal of Management Education, 48(3), 459–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, P., & Sahinidis, A. (2024). Exploring the impact of entrepreneurship education on social entrepreneurial intentions: A diary study of tourism students. Administrative Sciences, 15(3), 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D., & Lee, C. (2025). Mechanisms linking restaurant entrepreneurship education to graduating hospitality students’ entrepreneurial intentions: Validating the theory of planned behavior. SAGE Open, 15(1), 21582440251319957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z. M., & Kang, K. W. (2025). The impact of entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurship on entrepreneurial intention: Entrepreneurial attitude as a mediator and entrepreneurship education having a moderate effect. Sustainability, 17(10), 4733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, C. (1986). Entrepreneurship through social networks. In The art and science of entrepreneurship (pp. 3–23). Ballinger Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).