Abstract

Teaching is among the most fulfilling yet psychologically demanding professions. Expanding administrative responsibilities, technological adaptation, and increasingly diverse student needs have intensified workloads and contributed to widespread burnout and attrition. For arts educators, these pressures are compounded by the challenge of sustaining multiple professional identities as an educator, researcher, and artist (ERA) within institutional systems. Grounded in Structural Symbolic Interactionism and Social Identity Theory, this autoethnographic inquiry examines how integrating these identities within a portfolio career can enhance professional efficacy and personal well-being. Using reflective narrative analysis framed through the perspective of the educator–researcher–artist, this study emphasizes identity security as central to sustaining creativity, engagement, and career longevity. Findings suggest that balanced engagement across artistic, pedagogical, and scholarly domains mitigates identity fragmentation and reduces the risk of vocational burnout. The article concludes with a call for institutional frameworks that legitimize creative and research activity as integral to educational practice. Supporting such multidimensional engagement enables educators to maintain authenticity, motivation, and resilience in contemporary learning environments.

1. Introduction

While rewarding, the education profession can be demanding (Ma, 2022), leaving teachers prone to increased risk of stress-related illnesses and burnout (Cho et al., 2023; De Carlo et al., 2019; Dreer, 2023; Seibt & Kreuzfeld, 2021), which may be characterized by “feelings of exhaustion, depersonalization, and meaninglessness of work” (Dworkin, 1986, p. 68). The importance of a sustainable work–life balance has been well documented, with studies acknowledging the benefits of engaging in meaningful and enjoyable activities within community contexts, thereby fostering an identity grounded in a sense of belonging. For individuals who maintain multiple professional identities as educators, researchers, and artists, membership in each community through active participation is central to belonging and, therefore, well-being. A portfolio career, that is, a vocational arrangement encompassing two or more domains (Boyle, 2021), is a common occupational pathway for artists who may balance the pursuit of creativity with teaching and research. A portfolio career may encompass elements that not only complement one another but also significantly contribute to the development of overall professional expertise. For instance, an individual who simultaneously engages as an artist, teacher, and researcher may enhance their skill set by practicing their craft at a professional level while researching to deepen their understanding. Here, we see how the educator’s knowledge is broadened by the facilitation of professional growth, enabling them to transfer their new knowledge to students from an informed position of expertise.

At odds with the rationale for educators bringing knowledge acquired through artistic or research activities into their practice is a reluctance among some institutions to allow their staff to engage in activities other than those directly associated with employment duties. Primary and secondary educational institutions may be averse to supporting participation in activities beyond their designated scope, irrespective of their professional significance, and may even explicitly restrict such involvement through contractual stipulations (for elaboration, see the Section 5). Such mandates can come at the expense of an educator’s artistic and/or scholarly self, threatening overall well-being, connection to communities associated with their portfolio career, and professional sustainability.

While there is little research on how educational institutions may obfuscate the professional, research, and creative pursuits of their teachers, it is well documented that educators balance a wide range of tasks while responding to moving goalposts and the intensification of responsibilities (Ballet & Kelchtermans, 2009; Creagh et al., 2023; Hargreaves, 1992; Turner & Garvis, 2023; Van Droogenbroeck et al., 2014). Increasing awareness of diverse learning approaches and essential research has led to multifaceted responsibilities, including meaningfully supporting the growing number of students with neurodivergent learning profiles (Song et al., 2021).

Demands within the school environment can result in “time poverty” (Creagh et al., 2023) and blurred boundaries between work and personal life (Blazhevska Stoilkovska & Frichand, 2023), with many duties and accountabilities for educators limiting educators’ free time for personal pursuits (De Carlo et al., 2019; Dreer, 2023; Lemon & Turner, 2024). As free time diminishes, work–family conflict (De Carlo et al., 2019) and work–leisure conflict (Cho et al., 2023; Tsaur et al., 2012) arise, which can distort the sense of self toward an overly work-centric identity. An investigation of the recent grey literature reveals imbalances in education alongside alarming rates of teacher burnout and attrition (Department of Education, 2022; Education Support UK, 2023; Henebery, 2023), with professional pressures frequently resulting in diminished perceptions of self-efficacy (cite). Teachers are often the primary point of contact for students seeking help, or, as Offner (2022) puts it, the “first responders” in times of crisis.

Amid these pressures on educators, there is an imperative to attend to self-improvement, both professionally (Krolak-Schwerdt et al., 2014) and personally. Professional development, regarded to be foundational in improving teaching standards (Cohen & Hill, 2001; Creemers et al., 2013; Darling-Hammond & McLaughlin, 1995; Smith & O’Day, 1991), is prioritized by stakeholders who are cognizant of the message “demand for improved quality of teaching and learning and for increased accountability and higher academic standards” (Creemers et al., 2013, p. 3). However, the kinds of professional development mandated by institutions are often a one-size-fits-all approach, which does not necessarily ensure satisfaction and competency for educators or take into account what a teacher already does or does not know (Morris, 2019).

To address the challenges faced by arts educators when balancing the intersecting roles of artist, teacher, and researcher, this study asked the following questions:

- How do ERAs experience the integration and negotiation of multiple professional identities within institutional contexts that may privilege teaching over artistry or scholarship?

- In what ways does sustaining a balanced portfolio career contribute to educators’ professional currency and psychological well-being?

- What are the tensions and synergies between artistic, pedagogical, and scholarly identities in contemporary educational environments?

This article aims to highlight the unique positioning of the educator–researcher–artist and to illuminate connections between well-being and identity security, and the affordance of continual development in research and creative endeavors. While this study contributes to the emerging research on educator identity by positioning the importance and pedagogical relevance of supportive institutional environments, further research is recommended. By encompassing a broader set of perspectives on the need to fulfill professional development and creative expression outside school environments, we may be better positioned to understand the complexities of juggling identities as an educator–researcher–artist.

2. Theoretical Frameworks

Central to this paper are three theoretical frameworks: the autoethnographic inquiry as methodology, using Anderson’s (2006) framework for analytic autoethnography; social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1986); and structural symbolic interactionism (Stryker, 1980, 1987). The autoethnographic nature of this study allowed for the exploration of identity as an educator–researcher–artist (ERA), positioning my own reflections as “self-experience as a social phenomenon valuable and worthy of examination” (Edwards, 2021, p. 1).

Founders of social identity theory (SIT), Tajfel and Turner (1986), posited that people identify themselves and others with social groups, and that these affiliations play a vital role in shaping self-identity. Grounded in perceptions of efficacy within an assigned role, a work-centric identity encompasses low boundary control (Kossek & Lautsch, 2012), in which work is permitted to intrude on non-work domains, such as family time or personal activities. Work-centric identities are adjacent to role identities, which relate to a group or organization, providing structure and order to the identity profile (Burke & Stets, 2023). As work is already a central component of many people’s identities, boundary distinctions may blur, leading to the investment of one’s entire sense of well-being in work-related activities, a sense of belonging, and identity formation (Porter, 2010).

A broader social context of identity formation is evident in Stryker’s (1980) assertion of a reciprocal relationship between the self and society in his theory of structural symbolic interactionism (SSI). Stryker elaborates on symbolic interactionism (Cooley, 1902, 1911; Mead, 1934), a sociological theory that argues humans utilize a shared language to create common symbols and meanings, aiding both self-reflection and communication with others. Stryker emphasizes a reciprocal relationship between an individual’s self-concept and the social structure, with society providing the organized context and meanings from which the self develops, and, in return, the individual shapes social behavior. Moreover, Stryker conceptualizes the self not as a singular entity but as an assemblage of distinct “identities” organized hierarchically, with some identities being more significant or “salient” than others. Role identity through social designations, identity salience as dependent on social networks and situations, identity commitment, the situating of identity in preexisting social structures, and behavior as the product of identity all converge as elements of the greater development of identity in structural symbolic interactionism (Stryker, 1980). Stets and Serpe (2013) expand on this, positing that identity is defined by commonly held beliefs or understandings regarding (a) how individuals may inhabit various roles in society (e.g., mother, teacher, worker, or spouse), (b) how an individual participates in group membership (e.g., basketball team, union member, or church member), and (c) what characteristics a person may possess to signal their uniqueness (e.g., athletic skills, being a speaker of many languages, or being a musician). When examined through the lens of these theoretical concepts, balancing responsibilities may impact perceptions of the self between the role of teacher and relationships to social and group memberships in the school community, leaving little time to explore the characteristics that define one’s uniqueness.

A historical literature review spanning articles published between 1988 and 2008 by Akkerman and Meijer (2009) identified three themes in the teacher identity literature that point to the complexity of understanding the phenomenon of self: multiplicity of identity, discontinuity of identity, and the social nature of identity (p. 308). Highlighting the fluctuating nature of self-concept that “shifts with time and context” (p. 309), the authors contrast this widely accepted delineation of identity development with the previously held view that it is a fixed form. More recent literature echoes this sentiment… (MORE HERE).

Given that people possess multiple identity profiles because they participate in a range of roles, occupational circumstances, and social categories (Burke & Stets, 2023), music teachers engaged in a portfolio career must attend to the various expressions and developments of their numerous professional identities, as well as their personal and social memberships.

3. Materials and Methods

This study adopted an autoethnographic approach (Ellis, 1991, 1995, 2004; Ellis & Bochner, 2000; Bochner & Ellis, 2001), positioning the author’s experience as both subject and analytic lens. Autoethnography was selected as a methodology for its capacity to bridge personal narrative and cultural critique, offering insight into the systemic conditions that underpin the identity of the artist–teacher–researcher. To position the lived experience of narrative inquiry within the lens of existing literature, an analytic autoethnographic approach was undertaken (Anderson, 2006). This approach differentiated the study from an “evocative or emotional autoethnography” (Ellis, 1997, 2004), which prioritizes “narrative fidelity only to the researcher’s subjective experience” (Anderson, 2006, p. 386) toward an investigation that extends beyond the self-experience. To satisfy the requirements of Anderson’s framework for an analytic autoethnography (Anderson, 2006), I addressed the following five key features of this methodology: “complete member research (CMR) status; analytic reflexivity; narrative visibility of the researcher’s self; dialog with informants beyond the self; and commitment to the theoretical analysis” (Anderson, 2006, p. 378).

The primary data source was a series of personal reflections on identity formation spanning instrumental teaching, musical performance, and research engagement. Written over approximately 18 months, these reflections were structured as vignettes—episodic narratives that retell key moments in one’s life (Anderson & Glass-Coffin, 2013). The lengthy period of time taken to write the vignettes before the analysis phase of this study allowed for reflexive inquiry, or “describing and reflecting on oneself and experience at different points in time” (Anderson & Glass-Coffin, 2013, p. 73).

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Results: Structuring the Dataset from the Vignettes

Over 18 months, six vignettes were produced that offered considered reflections on salient experiences in the formation of identity as an educator–researcher–artist (ERA). Drawing on the content of the vignettes to determine themes related to the formation and subsequent balancing of ERA identities, textual data were entered as lines in a Microsoft Word Excel spreadsheet. Each line contained an average of 17.55 words, totaling 117 lines in the dataset. Table 1 details the organization of data as found in the vignettes.

Table 1.

Organization of Data: Vignettes.

To differentiate this study from emotive or evocative autoethnographies (Ellis, 1997, 2004), the formation of the vignettes was grounded in Anderson’s (2006) framework for analytic autoethnography. The first element, complete member research status (CMR), was satisfied by an authentic inhabitation of the social worlds under study, that is, the communities of educators, researchers, and artists. The retrospective composition of the vignettes ensured a retelling of foundational events in my identity formation as an ERA arising from an “opportunistic” paradigm (Adler & Adler, 1987), that is, a CMR driven by lifestyle and chance circumstance as opposed to a “convert” membership where the researcher is initially engaged in pure research as a non-CMR before being “converted” to the social world under study (Anderson, 2006). My immersion in these three worlds as a CMR is evidenced by approximately 30 years of practice as a musician and educator and approximately 5 years as a researcher.

The second element of Anderson’s framework, analytic reflexivity, requires “self-conscious introspection guided by a desire to better understand both self and others through examining one’s actions and perceptions in reference to and dialog with those of others” (Anderson, 2006, p. 382). Within the vignettes, strong themes of community membership prevail, demonstrating a historical reciprocity between me and community members over my years of practice. This reciprocity has influenced my ERA identity formation through experiences and episodes related to teaching, music-making, and research.

Anderson (2006) prefaces his third framework element, narrative visibility of the researcher’s self, by acknowledging the criticism that, traditionally, ethnographers are largely “invisible”. The contrast with autoethnography is that the perceptions of the researcher, along with feelings and one’s own experiences, are considered “vital data for understanding the social world being explored” (Anderson, 2006, p. 385). The vignettes meet this requirement through direct first-person storytelling, thereby situating myself as both a researcher and an inhabitant of the contexts investigated in the study.

The fourth framework dimension, dialog with informants beyond the self, serves as a mediator between engagement in self-absorbed indulgence and maintaining an awareness of a broader social context. The imperative of situating autoethnographic research as a small part of a larger inquiry, supported by data that engages others in the field, may help avoid solipsism and the overrepresentation of the author’s voice. To this end, the data presented in this study may, at first glance, disqualify inclusion in Anderson’s framework. However, a closer look reveals more than a single perspective being presented as data. The inclusion of a substantive literature review investigating phenomena associated with ERA identities is linked to social identity theory (SIT) (Tajfel & Turner, 1986) and structural symbolic interactionism (SSI) (Stryker, 1980). By integrating theoretical frameworks and a literature investigation, the risk of an introspective study devoid of social context is ameliorated.

Outlining a connection to analytic social science, Anderson (2006) states that the purpose of the fifth and final component of the framework, commitment to the theoretical analysis, is “to use empirical data to gain insight into some broader set of social phenomena than those provided by the data themselves” (p. 387). To adhere to this criterion, the data collated for this study were organized to allow empirical analysis. Through this analysis, it was possible to identify themes and situate them in the context of balancing identities as an ERA.

4.2. Analysis

The procedure for analysis first involved devising a structured line-by-line analysis. For each line, emergent themes were identified and documented. Iterative analysis streamlined the themes, yielding a more focused set that reduced topic duplication. From here, codes were assigned to the themes before further analysis illuminated patterns in role development, identity formation, and membership within each of the educator–researcher–artist communities. A total of 22 themes were identified and coded. Table 2 shows the frequency of the codes in the vignettes and their relationship to the mean.

Table 2.

Thematic Frequency.

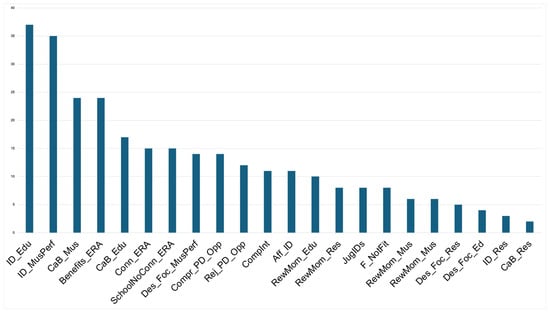

When arranged by thematic frequency from highest to lowest (see Figure 1), we see that the most represented topic is the discovery of identity as an educator (ID_Edu), followed closely by identity relationships in music performance (ID_MusPerf). The lowest occurring theme is community and belonging as a researcher (CaB_Res).

Figure 1.

Thematic frequency: Highest to lowest.

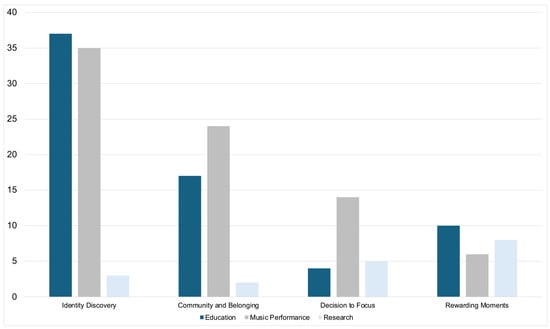

A more focused analysis of the results, examining overarching themes within the vignettes, enables a detailed comparison of each ERA identity. Figure 2 shows the thematic frequency, displayed in a clustered group view, organized into three categories: education, music performance, and research. This view helps to unpack the contrast between the different experiences when inhabiting the ERA identity.

Figure 2.

Thematic frequency is organized in the categories of Education, Music Performance, and Research.

Here, we see that research has a low frequency rate for identity discovery and community and belonging. However, the rewarding moments for research are similar to those of education and music performance. Education yields the highest level of identity discovery, followed very closely by music performance. The theme of community and belonging is most strongly represented by music performance here; this is echoed in the theme “decision to focus”, which describes episodes where I prioritized work or experiences associated with a single ERA identity.

5. Discussion

When the data is examined through the lens of social identity theory (SIT) (Tajfel & Turner), the sense of belonging to the social groups of educators and musicians is evident. Stryker’s (1980) structural symbolic interactionism (SSI) framework further substantiates this: a common linguistic framework, shared experiences, symbols, and meanings facilitated both self-reflection and communication with others throughout my life. The reciprocal relationship between my own self-concept and the social structure I have inhabited as a musician and educator has provided context and meaning from which the self emerges, thereby influencing social behavior. Accounting for the low representation in the categories of identity discovery and community and belonging from research membership is my late-stage entry into the world of academia. In both categories, research is seldom mentioned in the vignettes, suggesting a proportionate balance between time spent and the experience of inhabiting an ERA identity. Another factor may be that the identity formation of early career researchers can be challenged by insecurities of academic life and a perceived need to develop protective responses to precarious contexts (Callagher et al., 2021).

Social identity theory describes the development of self-concept as linked to group membership in social settings (Tajfel & Turner, 1986), with music often credited as an important means of expressing group belonging, particularly among adolescents (Clark & Lonsdale, 2023; Frith, 1983). Furthermore, the shaping of music preferences is heavily influenced by social group membership (Clark & Lonsdale, 2023; Lonsdale & North, 2017; North & Hargreaves, 1999), with Clark and Lonsdale (2023) finding associations among musical preferences, self-esteem, gender, age, and personality. Parental influences and upbringing are often foundational to a musician’s identity development, along with early opportunities to engage with music. It is the development of an ability that, while nurtured in a supportive environment, is attributed to personal practice and commitment (Boyle, 2021). The vignettes revealed an association of familial belonging and connection, seen here with the following excerpt:

Growing up, my father introduced me to a wide variety of artists, and so from a young age, I listened to Widor, Saint-Saëns, and Messiaen, but also ABBA, Kate Bush, and The Beatles.

The theme of connection continues with an acknowledgement of musical taste in part formed as a result of membership within the music performance community:

My bandmates and I listened to King Crimson, Mr. Bungle, John Zorn, and Deftones. At the same time, at university, I played and listened to the usual classical repertoire of a clarinet student; I particularly loved Weber and was beginning to explore the works of Stockhausen.

This vignette continues to highlight tensions of belonging to different communities within the music scene, with points of difference noted in genre representation:

When I was with friends or acquaintances from the rock community, I felt like I didn’t quite fit in, that I was “too classical”; this was also true when I was in the company of my fellow music major undergraduates, that I was “too rock”. Although there was plenty of excitement around performing, writing, recording, and learning a wide range of repertoire, I was not able to grasp my musical identity as a fixed form yet. I felt inauthentic when my “classical self” was presented in the rock environment, and vice versa.

It has been observed that the identity of a musician is often intrinsic rather than a professional overlay to an individual’s primary sense of self. Hallam (1998) found that it was difficult for young musicians to separate their “developing self-perception from that of being a musician” (p. 139), and several case studies show that there is an inseparability between the musician identity and playing an instrument (Boyle, 2021). Furthermore, it appears that the tension of pursuing career stability in the arts has little impact on musician identity (Beech et al., 2016), even though there may be competing demands between business interests and “art for art’s sake” (Coulson, 2012, p. 247). Musicians commonly take on teaching roles while maintaining their primary identity as musicians (Boyle, 2021; Coulson, 2012). Making a living from music often involves earning income through music-related activities, such as teaching. Research on career paths following music conservatory training has consistently highlighted the need for music conservatories to recognize the diverse income streams beyond performance (Bennett, 2009; Gonzalez, 2012).

Research Questions as a Basis for Understanding

In considering the research questions for this study, the results begin to construct a broader picture of ERA identity formation. The first research question addressed the integration and negotiation of multiple professional identities within institutional contexts, and how these were approached within environments that prioritized teaching over artistry or scholarship. Textual data found in the vignettes highlight a tension between prioritizing different components of the ERA portfolio career. This is reasonable given that the construction of identity is prone to change and development (Castelló et al., 2021; Erikson, 1950), and in some cases, involves an active and conscious pursuit of change and development (Bracher, 2006):

At one point, [when I was 16], I was asked to conduct the junior community concert band… I took on the role with enthusiasm and seriousness. I considered it to be of extreme importance to make music together… As a very young teacher/conductor, I celebrated the successes with my students and community band members and, admittedly, took it personally when things did not go according to plan. I found teaching and conducting to be fulfilling and was exceptionally proud of my work.

While in high school and in the first few years of higher education, I had formed the perception that I did not have a viable future as a career musician. Nonetheless, my love of music was deep, and this drove me to contribute to the art through initially focusing on becoming a teacher:

I enjoyed playing the clarinet immensely but was convinced that I had started learning too late to be a serious contender in the world of professional music performance. As I saw it, teaching was a meaningful and purposeful way to continue my musical journey.

As I progressed through my studies at university, my focus had shifted, bringing into focus the need to negotiate multiple professional identities within the institutional context of schools:

I had become far more serious about performing clarinet and was practicing or playing many hours most days, resulting in competing interests between performance and teaching.

The second research question explored how sustaining a balanced portfolio career could contribute to educators’ professional currency and psychological well-being. Here, the vignettes reveal themes that categorically demonstrate a propensity toward finding connections within community paradigms:

I was seeking a sense of belonging as a researcher–educator–musician in a new, transformative environment by presenting at an international music educators’ conference for the first time. After identifying as a musician–teacher for 27 years, finding my place in the research community, a new community, really mattered to me.

The third research question sought to examine the tensions and synergies among artistic, pedagogical, and scholarly identities in contemporary educational environments. Tensions are identified with episodes relating to school leadership, demonstrating a lack of support for opportunities in performance:

Upon accepting the position, I informed the school that I would require two days off for a previously booked performance. I was producing a concert at a high-profile venue in Melbourne with international guest artists and would also be performing. I was summoned to the assistant principal’s office, who asked for an explanation. I stated my case as clearly as seemed necessary, oblivious to the concept that this previously booked event would be an issue. The assistant principal expressed exasperation as he declared he would “allow” me to perform this one time, but it couldn’t happen again. He also pointed out that in my contract there was a clause that disallowed any outside work to be entered into. This meant that I was forbidden from performances; my recollection is that this extended to work outside of school hours.

The issue of music teachers being forbidden to perform is one of professional and knowledge-based currency. At the time, my assessment of this situation was that disallowing music engagement outside the school environment would be detrimental to my craft as a musician. Later, while undertaking my doctorate in music education, obfuscation to my pursuit of academic activity was also encountered:

When I received an opportunity to present at a major international music educators’ conference, I was excited; however, my place of employment was not, and rejected my application for leave. I felt that this opportunity was far too important not to take up, so I appealed the decision… It was also imputed that the music education conference was not sufficiently relevant for my professional development. As a music educator, I found this statement to be a source of cognitive dissonance.

My perception of the connectedness that exists between the different identities of an ERA is clearly outlined in the following excerpt, which speaks to the overarching benefits of inhabiting each of the three communities:

I carry with me a deep affection for each of the three worlds of performance, teaching, and research, and as time goes by, the more intertwined these worlds become. For me, there is a profound clarity in how teaching music informs my communication skills, which in turn transfers to communication in performance. My experience on stage has supplied me with knowledge and authority on music craft, from practice and performance strategies right through to managing performance anxiety. Additionally, my doctoral research on memory and cognition for instrumental music learning has opened a whole new world of understanding my students; I put into practice the new knowledge I have acquired in every lesson I teach. The doctoral coursework has shown me new theories of learning, illuminated compassionate teaching practices, and refocused my lens of instruction toward that of service as opposed to facilitator of virtuosic music making.

The value of nourishing each ERA identity with opportunities to develop knowledge and skills is evident in this series of narrative reflections. My development as a person and identity as a whole, situated in the context of an ERA, can be attributed to my membership in communities operating in music performance, education, and, later, academia. Connections and feelings of belonging provided me with the impetus to improve my competencies, driving a deepening of curiosity about music, teaching, and research. From this perspective, educational institutions would benefit in the long term by supporting their teachers in all pursuits related to the development of subjects that form the basis of their teaching practice. Furthermore, the experiences in this autoethnographic inquiry illustrate the need for growth, exploration, and self-expression as central components of well-being.

6. Conclusions

Using autoethnography as a methodology, this study explored the formation of identity. By conceptualizing the portfolio career of educator–researcher–artist (ERA) as an integrative model for sustaining motivation and professional longevity, this inquiry comprised personal reflections and the merging of other voices through a literature review to compile insights into sustainable practice. Substantiated by reflexive narrative data and research on ERA identity, I argue that recognizing and supporting educators’ multidimensional identities enhances both individual resilience and the broader creative and pedagogical value of educational institutions. This perspective is in opposition to how some institutional cultures privilege teaching output over artistic and/or research pursuits, risking the erosion of creative engagement and authentic self-expression. The danger of diminishing these qualities in an ERA is that doing so may alienate individuals from community membership. This, in turn, may contribute to stress levels, undermine well-being, and overemphasize the social bond within a school institution, blurring the boundaries necessary for achieving a work/life balance. Blurred boundaries may result in greater work hours, leading to burnout. Studies across various European regions reported burnout as the final stage before leaving the teaching profession (Van Droogenbroeck et al., 2021). Globally, a lack of work–life balance is often central to dissatisfaction and overwhelm for educators working in all areas from early childhood, primary and secondary schooling to tertiary-level education (Griffin, 2022; Iriarte Redín & Erro-Garcés, 2020).

Although this investigation into identity formation yielded essential insights into sustainable practice within the portfolio career paradigm, it is important to acknowledge some of the limitations encountered in this research. Primarily, the volume of narrative reflective data, though intentional and quality-driven, could have been more extensive. Secondly, a deeper engagement with other voices beyond those documented in the literature might have added further value to this inquiry; however, such a scenario might have changed the nature of this study toward a case study methodology. Future research exploring identity formation and the social worlds of ERAs from other members of the educator, researcher, and artist communities is recommended to broaden the perspectives beyond those offered in this paper.

Inhabiting the three different domains of education, research, and artistic practice requires adopting multiple role identities. While it is common practice to accommodate personal, professional, and institutional contexts through delineated identities, a portfolio career, as seen in ERAs, complicates the situation by requiring the maintenance of a greater number of identities in professional spaces (Boyle, 2021). To fully address the crucial need for a sense of belonging within social environments and ensure psychological well-being for ERAs, educational institutions should encourage the pursuit of development across three domains. Not only is the ERA richer for having nourished their creative and research identities, but new knowledge brought into the teaching practice stands to benefit students and other staff members in their immediate teaching community.

This study contributes to a growing body of scholarship that positions identity not as a stable or fixed construct, but as an emergent and relational process shaped through ongoing negotiation between personal meaning-making and institutional discourses. From this perspective, the ERA identity may be understood as a dynamic force in which individuals continually reconcile competing expectations, values, and temporal demands across domains of practice. The capacity to sustain such an identity is, therefore, contingent not only on individual resilience but on the structural conditions that legitimize multiplicity and hybridity within professional roles. Without institutional recognition of these hybrid identities, ERAs remain vulnerable to symbolic marginalization that quietly erodes professional agency, creative risk-taking, and long-term vocational commitment.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board the university of Melbourne (protocol code 34347, date of approval 29 October 2025) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available as transcriptions with associated coding. To obtain a copy, inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CMR | Complete Member Researcher |

| ERA | Educator–Researcher–Artist |

| SIT | Social Identity Theory |

| SSI | Structural Symbolic Interactionism |

References

- Adler, P. A., & Adler, P. (1987). Membership roles in field research. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Akkerman, S. F., & Meijer, P. C. (2009). A dialogical approach to conceptualizing teacher identity. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L. (2006). Analytic autoethnography. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 35(4), 373–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L., & Glass-Coffin, B. (2013). I learn by going: Autoethnographic modes of inquiry. In S. Holman Jones, T. E. Adams, & C. Ellis (Eds.), Handbook of autoethnography (pp. 57–83). Left Coast Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ballet, K., & Kelchtermans, G. (2009). Struggling with workload: Primary teachers’ experience of intensification. Teaching and Teacher Education, 25(8), 1150–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beech, N., Gilmore, C., Hibbert., P., & Ybema, S. (2016). Identity-in-the-work and musicians’ struggles: The production of self-questioning identity work. Work, Employment, and Society, 30(3), 506–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, D. (2009). Academy and the real world: Developing realistic notions of career in the performing arts. Arts and Humanities in Higher Education, 8(3), 309–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazhevska Stoilkovska, B., & Frichand, A. (2023). Identification of work-family boundary management styles: Two-step cluster analysis among teachers in primary, secondary and university education. Annual of the Faculty of Philosophy in Skopje, 76(1), 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochner, A. P., & Ellis, C. (2001). Ethnographically speaking: Autoethnography, literature, and aesthetics. AltaMira Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle, K. (2021). The instrumental music teacher: Autonomy, identity, and the portfolio career in music. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bracher, M. (2006). Radical pedagogy: Identity, generativity, and social transformation. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, P. J., & Stets, J. E. (2023). Identity theory: Revised and expanded (2nd ed.). Oxford Academic. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callagher, L. J., Elsahn, Z., Hibbert, P., Korber, S., & Siedlok, F. (2021). Early career researchers’ identity threats in the field: The shelter and shadow of collective support. Management Learning, 52(4), 442–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelló, M., McAlpine, L., Sala-Bubaré, A., Inouye, K., & Skakni, I. (2021). What perspectives underlie ‘researcher identity’? A review of two decades of empirical studies. Higher Education, 81, 567–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H., Pyun, D. Y., & Wang, C. K. J. (2023). Teachers’ work-life balance: The effect of work-leisure conflict on work-related outcomes. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 45, 1097–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A. B., & Lonsdale, A. J. (2023). Music preference, social identity, and collective self-esteem. Psychology of Music, 51(4), 1119–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, D. K., & Hill, H. C. (2001). Learning policy. Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cooley, C. H. (1902). Human nature and the social order. Charles Scribner’s Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Cooley, C. H. (1911). Social organization: A study of the larger mind. Charles Scribner’s Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Coulson, S. (2012). Collaborating in a competitive world: Musicians’ working lives and understandings of entrepreneurship. Work, Employment and Society, 26(2), 246–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creagh, S., Thompson, G., Mockler, N., Stacey, M., & Hogan, A. (2023). Workload, work intensification and time poverty for teachers and school leaders: A systematic research synthesis. Educational Review, 77, 661–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creemers, B., Kyriakides, L., & Antoniou, P. (2013). Teacher professional development for improving quality of teaching. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling-Hammond, L., & McLaughlin, M. W. (1995). Policies that support professional development in an era of reform. Phi Delta Kappan, 76(8), 597–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carlo, A., Girardi, D., Falco, A., Dal Corso, L., & Di Sipio, A. (2019). When does work interfere with teachers’ private life? An application of the Job Demands-Resources Model. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Education. (2022). National teacher workforce action plan: Keeping the teachers we have. Australian Government. Available online: https://www.education.gov.au/national-teacher-workforce-action-plan/priority-area-3-keeping-teachers-we-have (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Dreer, B. (2023). On the outcomes of teacher wellbeing: A systematic review of research. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1205179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dworkin, G. A. (1986). Teacher burnout in public schools: Structural causes and consequences for children. State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Education Support UK. (2023). Teacher wellbeing index 2023. Available online: https://www.educationsupport.org.uk/media/0h4jd5pt/twix_2023.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Edwards, J. (2021). Ethical autoethnography: Is it possible? International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 20, 160940692199530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, C. (1991). Sociological introspection and emotional experience. Symbolic Interaction, 14, 23–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, C. (1995). Final negotiations: A story of love, loss, and chronic illness. Temple University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, C. (1997). Evocative autoethnography: Writing emotionally about our lives. In W. G. Tierney, & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Representation and the text: Re-framing the narrative voice (pp. 115–142). State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, C. (2004). The ethnographic I: A methodological novel about autoethnography. AltaMira Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, C., & Bochner, A. P. (2000). Autoethnography, personal narrative, reflexivity: Researcher as subject. In N. K. Denzin, & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed., pp. 733–768). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and society. W. W. Norton & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Frith, S. (1983). Sound effects: Youth, leisure and the politics of rock‘n’roll. Constable. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, M. J. F. (2012). How students learn to teach? A case study of instrumental lessons given by latvian undergraduate performer students without prior teacher training. Music Education Research, 14(2), 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, G. (2022). The ‘Work-Work Balance’ in higher education: Between over-work, falling short and the pleasures of multiplicity. Studies in Higher Education, 47(11), 2190–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallam, S. (1998). Instrumental teaching. Heinemann Educational Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves, A. (1992). Time and teachers’ work: An analysis of the intensification thesis. Teachers College Record, 94(1), 87–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henebery, B. (2023, February 20). How teacher burnout is exacerbating Australia’s school workforce crisis. The Educator Australia. Available online: https://www.theeducatoronline.com/k12/news/how-teacher-burnout-is-exacerbating-australias-school-workforce-crisis/281966 (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Iriarte Redín, C., & Erro-Garcés, A. (2020). Stress in teaching professionals across Europe. International Journal of Educational Research, 103, 101623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossek, E., & Lautsch, B. (2012). Work-family boundary management styles in organizations: A cross-level model. Organizational Psychology Review, 2, 152–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krolak-Schwerdt, S., Glock, S., & Böhmer, M. (2014). Teachers’ professional development: Assessment, training, and learning (Vol. 3). Sense Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Lemon, N., & Turner, K. (2024). Unravelling the wellbeing needs of Australian teachers: A qualitative inquiry. The Australian Educational Researcher, 51, 2161–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonsdale, A. J., & North, A. C. (2017). Self-to-stereotype matching and musical taste: Is there a link between self-to-stereotype similarity and self-rated music-genre preferences? Psychology of Music, 45(3), 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D. (2022). The role of motivation and commitment in teachers’ professional identity. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 910747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mead, G. H. (1934). Mind, self & society. The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, D. (2019). Student voice and teacher professional development: Knowledge exchange and transformational learning. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- North, A. C., & Hargreaves, D. J. (1999). Music and adolescent identity. Music Education Research, 1(1), 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Offner, D. (2022). Educators as first responders: A teacher’s guide to adolescent development and mental health, grades 6–12. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, G. (2010). Work ethic and ethical work: Distortions in the American dream. Journal of Business Ethics, 96, 535–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibt, R., & Kreuzfeld, S. (2021). Influence of work-related and personal characteristics on the burnout risk among full and part time teachers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18, 1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M. S., & O’Day, J. (1991). Systemic school reform. In S. Fuhrman, & B. Malen (Eds.), The politics of curriculum and testing (pp. 233–268). Falmer Press. [Google Scholar]

- Song, P., Zha, M., Yang, Q., Zhang, Y., Li, X., & Rudan, I. (2021). The prevalence of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Global Health, 11, 04009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stets, J. E., & Serpe, R. T. (2013). Handbook of social psychology, handbooks of sociology and social research (J. DeLamater, & A. Ward, Eds.; Vol. 31). Springer Science and Business Media. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stryker, S. (1980). Symbolic interactionism: A social structural version. Benjamin/Cummings Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Stryker, S. (1987). The vitalization of symbolic interactionism. Social Psychology Quarterly, 50(1), 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In S. Worchel, & W. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 7–24). Nelson-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Tsaur, S. H., Liang, Y. W., & Hsu, H. J. (2012). A multidimensional measurement of work-leisure conflict. Leisure Sciences, 34, 395–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, K., & Garvis, S. (2023). Teacher educator wellbeing, stress and burnout: A scoping review. Education Sciences, 13, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Droogenbroeck, F., Spruyt, B., Quittre, V., & Lafontaine, D. (2021). Does the school context really matter for teacher burnout? Review of existing multilevel teacher burnout research and results from the Teaching and Learning International Survey 2018 in the Flemish- and French-speaking communities of Belgium. Educational Researcher, 50(5), 290–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Droogenbroeck, F., Spruyt, B., & Vanroelen, C. (2014). Burnout among senior teachers: Investigating the role of workload and interpersonal relationships at work. Teaching and Teacher Education, 43(2014), 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).