Abstract

Latinas have graduated from college at an increasing rate over the last decade, but they are still underrepresented in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) degree programs and careers. One method to tackle challenges that can affect the persistence of Latinas in STEM programs is mentorship. The mentorship program in the following study was part of a larger project focused on studying Latinas in STEM undergraduate success, which utilized a Latina/o resilience model as its conceptual framework. Through the use of focus groups and written reflections, we were guided by the following research question: What types of successful peer mentoring strategies do Latinas develop in their pursuit of a college STEM degree at a Hispanic Serving Institution in Texas? Three strategies emerged from the data: (a) connection through shared cultural experiences, (b) seeking other Latinas in STEM, and (c) moving from mentorship into friendship. We identified that mentorship rooted in shared cultural identity, peer support, and emotional connection served as key mechanisms of resilience and persistence. Resilience, through shared culture and context, was brought to the forefront during this mentorship experience.

1. Introduction

With the population of Latinas in the United States making up 17% of all adult women, this demographic accounted for the largest numeric increase in any major female racial/ethnic group from 2010 to 2022 (). Although Latinas are also graduating from college at higher rates than ever before, they are still underrepresented in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) degree programs and in STEM careers (). In fact, although Latinas are more likely to be “A” students, they are less likely than their Latino peers to have a favorite STEM subject or score high on STEM confidence scales (). This ultimately is reflected in the underrepresentation of Latinas both enrolled at Hispanic-serving institutions and among STEM degree recipients ().

To begin closing the gap for Latinas in STEM, we must examine their undergraduate experiences and identify the factors that influence their persistence in these fields. There are several assets and strengths that Latinas bring into their college experiences. Latinas can enter their programs already possessing passion for their respective STEM fields and having already started forming identities as STEM people through their own self-recognition and recognition from peers and teachers (). Latinas can also enter their undergraduate years having been positively influenced and encouraged to pursue STEM degrees by their families which can lead to confidence in their academic performance abilities and persistence within their programs (; ; ). Beyond assets, Latinas can face several challenges as they pursue their STEM degrees, such as sexism, racism, dealing with microaggressions in the classroom, and a lack of a STEM identity (; ; ). One method to tackle challenges that can affect the persistence of undergraduate Latinas in STEM programs is mentorship.

Mentors serve an important role in the socialization of undergraduate students into STEM communities and allow them to form strong identities as scientists (). Peer mentors can smooth the transition into college environments, especially into challenging disciplines and programs, increase a sense of belonging and self-efficacy, and expand their mentee’s network, all of which can lead to retention and persistence within STEM programs (; ; ). These benefits can also come from forming deeper connections with peers who share similar identities and characteristics. These experiences can give these students the ability to form community. For example, students form positive connections to a STEM identity when given the chance to speak with peers who also understand their passion for STEM and the path it takes to be successful in STEM fields (). Keeping this in mind, this study focused on how peer mentorship can serve as a pathway for activating the resilience processes outlined in the Latina/o resilience model (). We follow a peer mentorship program to conduct focus groups and analyzed the resulting data guided by the research question: What types of successful peer mentoring strategies do Latinas develop in their pursuit of a college STEM degree at an HSI in Texas?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Latine/Hispanic Experiences in Higher Education

In 2021, Latines/Hispanics made up 19% of the total population in the United States, with future projections showing that this number will grow to about 51% by 2050 (; ). With this demographic making up such a large percentage of the population, Latines/Hispanics still lag behind other racial/ethnic groups in education (). However, this demographic continues to make significant impacts at every education level as Latines/Hispanics are graduating high school at rates higher than all Americans and are making strides in bachelor’s degree completion (). This also applied to the number of Latine/Hispanic students graduating with a STEM degree, with completion rates up from 10.4% in 2012 to 15.6% in 2022 ().

Various factors can affect the experiences of Latine/Hispanic students at colleges and universities, such as attending a Hispanic-Serving Institution (HSI). Attending an HSI can have an impact on the experiences Latinas have in their undergraduate years. Hispanic-Serving Institutions (HSIs) are colleges and universities that have earned the designation by enrolling at least 25 percent Latine students (; ; ). These institutions have been growing each year as the number of Latina/o/e students rises in the United States; with the rising number of HSIs comes the increase in attention and research to truly figure out what it means to be a Hispanic “serving” institution (; ). HSIs are typically located in areas with high Latina/o/e population rates, which can influence students’ choices, as many may opt to live at home with their families if the institution is nearby (; ). Additionally, the possibility of a higher number of Latina/o/e students in courses can enable students to connect with peers and share support and meaningful college experiences, which aids in the retention of these students (; ). These findings suggest that HSIs may provide cultural familiarity and opportunities for peer connections, but they may not adequately address gendered and cultural barriers to academic success that Latine students may face.

The experiences of students in their undergraduate careers are also heavily influenced by the majors they choose and their gender. Students may have different reasons for choosing a STEM major, but there is a significant gender gap when it comes to men and women enrolling in these degrees and pursuing STEM careers after graduation (). Gender stereotypes significantly influence the degree programs women choose, often shaping beliefs from childhood that they do not belong in STEM fields that are more math-intensive, like computer science and engineering (; ). () also found that STEM college learning environments “clearly replicated hegemonic masculinity and heteronormativity,” fostering a masculine “dude culture” that made STEM disciplines unwelcoming, and often hostile, for students with minoritized sexual and/or gender identities. This early socialization and implicit and explicit associations with the STEM field contribute to persistent gender disparities in pursuing these majors and careers (; ; ). Thus, even as overall enrollment of female students increases, gendered dynamics within STEM may reinforce exclusion, raising the question of what can be done in addition to institutional representation to aid Latina persistence and resilience in their STEM programs.

Looking beyond gender differences, Latina students often bring cultural values and traditions that profoundly shape their college experiences. Family is a central pillar of Latine culture, commonly expressed through familismo, which emphasizes strong family bonds, shared responsibility, and prioritizing the needs of the family over those of the individual (; ; ). While familismo can be a powerful motivator, driving students to succeed for the benefit and well-being of their families, it may also conflict with the dominant culture of STEM education, which tends to prioritize competition, self-promotion, and individual achievement (; ). This cultural mismatch can create tension as students balance rigorous academic demands with family obligations and priorities.

The underrepresentation of Latine students in STEM reflects a broader disparity in the workforce. In 2021, Latine workers comprised 17% of all U.S. employees but only 8% of STEM professionals (). Employment patterns further reveal that Latino men are most often found in construction and extraction, production, and management roles, while Latinas tend to work in office and administrative support, sales, and food preparation and serving positions (). Many Latine Americans attribute these disparities to a lack of visible role models, such as Latine STEM university students, teachers, and professionals, as well as negative educational experiences, including being treated as if they are unable to understand STEM subjects (; ). () found that Latines/Hispanics have a negative perception of STEM careers, noting that they do not find it to be very open or welcoming to Latines/Hispanics, which further leads to the underrepresentation in this field. To increase the representation and visibility of Latines/Hispanics in STEM, mentorship can play a crucial role.

2.2. Mentorship for Undergraduates in STEM

Mentorship, particularly one-on-one mentoring, can be an important contributor to the academic success and identity development of an undergraduate student. When students have positive experiences with mentoring, there can be increases in social integration at their institutions, retention in their majors, degree attainment, and in career satisfaction and commitment (; ). () found that a few key components of an effective mentoring relationship included mutual respect and trust, role modeling, exchange of knowledge, and a caring, personal relationship. Overall, both mentors and mentees typically seek relationships characterized by open communication and accessibility, where mentees receive supportive feedback and advice, while mentors have the opportunity to refine their knowledge and receive constructive input ().

Mentoring relationships have evolved from being solely beneficial to mentees into collaborative partnerships, where both mentors and mentees engage in reciprocal activities like reflection and problem-solving, resulting in mutual benefits for all participants (). In higher education, typical mentorship relationships are more commonly conceptualized as a formal academic faculty-to-undergraduate relationship, often occurring within structured mentoring programs or stemming from teaching or research supervision (). This perception reinforces mentorship as a heirarchial structure where a junior being mentored by someone more senior and experienced; however, mentors can also be peers who are closer in age and position to the mentees (; ). Upperclassmen undergraduate peer mentors can be especially insightful as they have worked to overcome some societal and institutional barriers and can advise underclassmen on how to be successful (). Peer mentors can more readily recall relatable experiences, having faced them themselves more recently, and mentees can feel more comfortable approaching a peer rather than someone like a supervisor or faculty member who can be seen as more intimidating (; ). These relationships are also often mutually beneficial as mentees gain knowledge of success strategies, emotional support, and self-confidence, while mentors, who are students themselves, develop greater awareness of their own skills and knowledge and the opportunity to view mentoring as valuable leadership and professional development experience for their future careers (; ). Despite these advantages, peer mentorship, particularly for students from marginalized backgrounds, remains comparatively underexamined within higher education research ().

Undergraduate students also often gravitate toward mentors of the same race and gender, as they may share common life experiences and can foster connections that feel like safe spaces for discussing their identities and interests (). This can be beneficial for the students who may be underrepresented in their majors, institutions, or career fields. For example, women in STEM frequently face challenges in finding mentors, a struggle less commonly experienced by their male counterparts. This inequity can stem from several barriers, including enduring gender stereotypes about intelligence and gendered biases within the workplace (). For Latinas in STEM programs, having the opportunity to have mentors that share similar identities also allows for more culturally responsive mentorship, which can enhance their psychosocial support and sense of safety and validation within their programs and institutions (). These implications may reflect that mentorship can serve not only for academic guidance but also identity validation, particularly for students who rarely see themselves reflected in their disciplines or institutions.

First-generation college students, who are often from lower-income backgrounds and disproportionately Black or Hispanic, face distinct identity-based challenges that can be mitigated through mentorship (). It can be difficult to find mentors from underrepresented backgrounds in STEM fields. Latinas can utilize different methods to find mentors, from formal programs to looking for Latina faculty members outside of their programs to informal mentoring from peers in race/ethnicity-specific student organizations (). Peer mentors for underrepresented students in STEM can offer crucial representation and foster a sense of community, helping students develop a strong science identity by providing role models who reflect their own backgrounds (; ).

3. Theoretical Framework

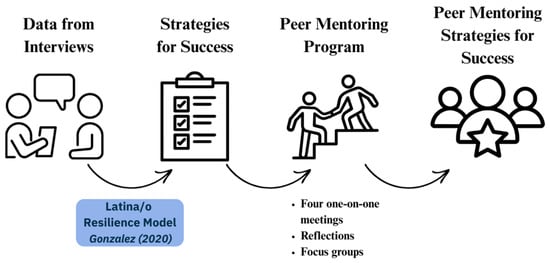

As part of a larger study focused on studying Latinas in STEM undergraduate success, we utilized the findings from interviews completed within the same institution to develop the peer mentorship program (Figure 1). The interview findings consisted of experiences and success strategies gathered from Latina undergraduate STEM majors, which were conceptually framed by a model of Latina/o resilience as its theoretical framework (), a model that takes community cultural wealth (CCW) by () as a foundation. These success strategies were then used to develop a peer mentoring one-on-one program, of which the following data is based on (see Figure 1). Specifically, success strategy themes identified from interviews were utilized as topics of discussion and reflection for mentors and mentees.

Figure 1.

Development and process of the Embracing Latina Learners’ Assets in STEM (ELLAS) Peer Mentorship Program. The Latina/o Resilience model () was utilized.

During a time when most theories of cultural capital centered around socioeconomic status and education levels, Tara Yosso created ’s () model of CCW highlights six forms of capital that students of color can leverage as they navigate college environments: aspirational capital; familial capital; social capital; linguistic capital; resistant capital; navigational capital. The CCW model is focused on the strengths that these students possess to better understand their college experiences; it describes ways for students from communities of color to leverage their identities and backgrounds as valuable assets in pursuing their goals and pushing back against the deficient perspective often taken against the experiences of communities of color ().

The Latina/o/e resilience model expands on ’s () model to introduce an asset-based approach of recognizing a resilience element among Latines, and to examine how the values, behaviors, and knowledge of the Latine culture influence cultural wealth for students in college and after their graduation (). For example, Latinas who come to college with a strong sense of the cultural value of familismo, or a strong identification and attachment to family, were more likely to be academically successful and adjusted better to higher education environments (; ). The Latina/o resilience model used in this research study recognizes that these students enter higher education equipped with diverse forms of capital and integrates this knowledge with an appreciation for the resilience cultivated through their unique cultural backgrounds. By doing so, the model empowers students to become fully aware of their strengths and potential, fostering a sense of agency and efficacy not only throughout their college journey but also as they transition into the workforce (). There are five contexts involved in this model—home, school, college, community, and workplace—that provide linear and nonlinear models of how culture influences resilience as Latina/os navigate multiple new environments (). In this study, we position peer mentorship as a mechanism for recognizing the resilience processes outlined in the Latina/o resilience model (), enabling students to draw on cultural values, community ties, and learned strategies to navigate challenges in STEM and persist toward their degrees.

4. Methods

As previously mentioned, this study was a part of a larger multiple-case qualitative research study, specifically a replicated case study that is constitued by each of two public R1 Hispanic-Serving Institutions in Texas that are part of this study. This study focused in the success of Latinas in STEM through an informal peer mentorship program built on the successful strategies collected from senior Latinas in STEM, strategies that considered their particular family, social, and cultural background of these students under a resilience framework. The aim was to study a phenomenon within a real-world context to understand how our participants’ perceptions and experiences were impacted by the people, programs, policies, and institutional environments around them (; ). The following case study consisted of a group of participants attending an urban, public R1 institution with a high enrollment of underrepresented students, including approximately one-third Latine student population. The “bounds” of the case study were the institution itself and the mentorship program, whereby participants who were freshman or sophomores were paired with a junior or senior and met four times during an academic year.

As a reference point, an operational definition of mentorship from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine was adopted: “Mentorship is a professional, working alliance in which individuals work together over time to support the personal and professional growth, development, and success of the relational partners through the provision of career and psychosocial support,” (). Mentors and mentees were provided with this definition along with other terms (such as sense of belonging) and tips or guidelines (such as building trust) to guide the mentoring process. The aim of the program was to cultivate resilience in a supportive social climate, thus supporting the success, and ultimately the retention, of Latinas in STEM.

Throughout one academic year, mentors and mentees met four times in pairs and a wrote a short reflection after each meeting. To guide one-on-one meetings, four topics for reflection were provided: peer networks, family influence and support, self-efficacy and perseverance, and sense of belonging considering women of color in STEM. These topics were key themes identified from individual interviews of successsful Latinas in STEM (Figure 1). Finally, we utilized a focus group method as a final interview with our mentors and mentee groups. We wanted to generate a rich understanding of the insights and experiences of our participants in an informal group setting that would encourage a sense of belonging within the group and allow them to feel comfortable sharing information (; ). The focus groups were semi-structured interviews that utilized specific yet open-ended questions to prioritize the topics needing to be explored while allowing space and attention for the interviewer and interviewees to deviate to explore ideas or responses with more detail (). Utilizing this focus group method allowed for a focus on our research question while also allowing the participants to make comparisons and form opinions on others’ experiences within the same mentorship program to produce valuable insights ().

4.1. Participants

The written reflection data consisted of 14 undergraduate participants, with seven being mentors (juniors or seniors) and seven mentees (sophomores or freshmen) reflecting on their one-on-one meetings (Table 1). Focus group data consisted of four mentors and five mentees. (Not all 14 participants were able to attend/complete the focus group.) These students all identified as female, as Latina, and were enrolled in STEM degree programs. Participants were all attending the same university, a public R1 Hispanic-Serving Institution in Texas. Of the focus group participants, all mentees and four of the five mentors identified as first-generation college students. The rest of the participants’ statuses for this are unknown.

Table 1.

Mentors and Mentees Classifications and Majors.

4.2. Data Collection

This study consisted of a peer mentorship program, in which Latina undergraduate students entering their junior and senior years in a STEM program were paired with freshmen or sophomore Latina undergraduate students within similar majors. Mentors for the mentorship program were recruited through previous research conducted by the team. To recruit participants to serve as mentees for the mentorship program, we compiled a list of all STEM-focused student organizations on campus and included the authors’ faculty contacts to utilize that network for student recommendations. The research team also attended a Latine-focused networking mixer social event to recruit participants. We contacted interested participants through email and a flyer; these students were asked to complete an online interest form that included questions about their undergraduate classification, scheduling preferences, and STEM major. Latina students were then paired one-to-one and met four times throughout one academic year of a fall and spring semester.

The mentors and mentees wrote four reflections, two in the fall semester and two in the spring semester, after each formal meeting. The reflections for both the mentees and mentors contained similar questions about their meetings and the responses to the different topics that each meeting was supposed to cover. For example, for the second reflection, mentees were asked, “What did you learn and/or discuss regarding the role of family (particularly parents) in persisting from high school to/through college?” and mentors were asked, “What did you discuss (and/or learn) regarding the role of family (e.g., parents) in persisting from high school to/through college?” Each person was also asked how they benefited from their meetings during each reflection.

At the end of the academic year in May 2023, the two groups, the mentors and the mentees, completed separate focus groups in person with three members of the research team. Each focus group interview lasted around 60 min and included five semi-structured questions focused on their experience participating in the mentorship program and their identities as Latinas in STEM. This allowed the participants an opportunity to reflect on their time with their partners and hear about how the mentorship experience unfolded for other pairs.

4.3. Data Analysis

The reflections were each written individually and independently after each meeting. These reflections were submitted to the research team, where one member then reviewed and coded each written reflection. After data collection for the focus groups, both interviews were transcribed by an outside contracted source to ensure trustworthiness and were then checked for errors and accuracy by the research team (). Both interviews were coded by a second member of the research team. Based on codes created during the analysis of the reflections, a mix of deductive and inductive coding was utilized during the analysis of the focus group interview data. Using a ‘start list’ of codes derived from the reflections leading up to the focus groups, the researcher analyzing the data could build on prior findings, refining existing codes and developing new ones based on insights from the focus group discussions ().

With the knowledge that we as researchers come into this study with our own perspectives and biases and as active contributors to the social world we study, there were several reflexivity exercises applied throughout the research study (). As the researchers began analyzing data, questions and comments based on the data were written in memos throughout the analysis process to allow further reflection and discussion of the data as a research team (). Since coding is an interpretive act that is based on personal knowledge and experience, members of the research team would meet to review and revise the codes (). Debriefing sessions served to review memos and questions, critically analyze findings, and link the results to the research question ().

4.4. Researcher Positionalities

Given the nature of this work, we briefly reflect on our positionalities as researchers to provide greater transparency and acknowledge how our identities shape our analysis in this study (). All authors of this paper identify as Latina women. The first author is a child of Mexican immigrants, a wife, a mother, and a Latine scholar. She is a current doctoral student whose research centers on the lived experiences of Latine students, faculty, and administrative staff and on Hispanic Serving Institutions (HSIs). The second author is a child of Latine immigrants. Her educational background is in STEM with a terminal degree in the life sciences and postdoctoral experience in higher education research. She currently works in university administration, and her interests include marginalized populations in STEM, cultural influences in STEM pathways, and promoting the success of students in need. The third author was born and raised in Mexico but has lived and worked in the U.S. for over two decades. She is a faculty member at a large R1 university and focuses on access, retention, graduation, workforce, and success of students, particularly in STEM. She additionally holds a leadership role within the university’s provost office. The fourth author was born in Mexico and came to the United States at the age of four. Her educational background is in education and psychology, and her research interests are focused on supporting STEM Latina and military students in their academic and professional pursuits. Her goal is to pursue a doctoral degree and advocate for immigrant students’ mental health.

5. Findings

Three peer mentorship strategies emerged from the data related to the research question: (a) connection through shared cultural experiences, (b) seeking other Latinas in STEM, and (c) moving from mentorship into friendship.

5.1. Connection Through Shared Cultural Experiences

The findings of this study revealed that students could form fast mentoring connections due to their shared identities as Latinas and the cultural backgrounds they brought into their college experiences. The participants mentioned being able to connect with one another based on sharing similar experiences growing up in homes with similar cultures and experiencing college through similar perspectives. Many of the pairs spoke in depth about their parents, especially, and how their relationships have been affected by attending university. Oftentimes, many of the participants would speak about how they felt like their families did not understand what they were going through and how they appreciated the ability to connect with other women from similar cultures who have also navigated these familial relationships. The mentee from pair 2 mentioned how it was “nice to be seen by somebody else who is kind of going through the same thing.” Another mentor described the comparison of upbringings and the shared experiences as a bonding experience.

Within the Latine/Hispanic family, there can often be a sense of responsibility felt by the daughters to remain available for their families and to work hard to make their families proud (). The mentorship pairs identified this mindset as a significant source of motivation to excel in their courses and graduate with a STEM degree. Despite facing pressure from their families and barriers within society, they found strength and resilience, particularly when they could connect and build community with other Latinas. The mentee from pair 1 said:

“One of the inspiring things she reminded me of is that I’m not alone in my struggles. She reminded me that mostly everyone is struggling and figuring out their own matters even similar to mine, and I felt less alone. …With fewer resources and prejudices, it can lead to us feeling like we are not fitted for college or career success. While this reality sucks, at the very least, we can help each other.”

The students found that they could also connect due to shared cultural phrases and language. The participants spoke Spanish, which gave them another tie to their culture, and as they opened up to one another, the shared language acted as another form of connection to each other. Throughout the focus group sessions, participants would say specific phrases in Spanish that meant something to them, only for another participant to share a similar understanding. One mentee described feeling like choosing a different career path, only to tell herself, “Si se puede,” and another mentee shared how her mentor had a motto that she shared with her: “Todo pasa por algo.” As the participants spoke about their families, they would share what family members would say to them as they tried to explain what they were studying or what their end goals were. They brought in experiences they had shared within their families and communities that had huge ties to the language they all shared: Spanish. The mentee from pair 3 said:

“She could relate because she’s done that before. If I say, “Oh, I’m studying for midterms,” she knows exactly what that is. Compared to my family, it’s like, “Oh, tienes un exam? Well, pues échale ganas!” [“Oh, you have an exam? Well, then go for it!”]”

Therefore, the mentorship was strong due to shared values, behaviors, and knowledge or culture (the center of the resilience model; ), and thus shared resilience, which was brought to the surface for mentees as they saw and connected with their mentors persisting in STEM.

5.2. Seeking Other Latinas in STEM

A second finding focused on the desire that the mentors and mentees had to find other Latinas within their programs to befriend, create mentorship relationships with, and expand their own networks. The participants’ experiences as Latinas within STEM programs and the challenges they faced being one of the few Latinas in their programs were shared between the mentors and mentees. The mentors spoke about their experiences inside of the classroom and being one of the few women and Latinas in their classrooms. Many participants spoke about not having many Latina faculty members and struggling to find and connect with other women, and specifically Latinas in STEM, in their classes and within their majors. The mentors would also provide encouragement to the mentees and would serve as examples of other women persisting in spaces where they were not equally represented. The mentee from pair 2 noted the importance of feeling a connection with other Latinas after the mentorship program due to shared experiences within their majors:

“For example, in most of my classes, also White dudes, like very CIS White male, the whole space is. So, you know how guys talk over you? You don’t really feel seen or heard as much. Then, you come into a space like this, and you go, “Wow, these people all know what it feels like, what I’m going through. They’re all going through and achieving more, and it’s possible to just do that and be better,”— because you see yourself in them.”

Being in STEM fields, the participants also shared experiences struggling in coursework and in struggling to feel like they belonged in STEM. A few mentees mentioned feeling a strong sense to switch majors during particularly difficult semesters. During those moments, the participants would recall how seeing other Latinas in STEM provided them with motivation. However, the mentee from pair 2 spoke about how finding a mentor within their STEM major made a difference in their mindset:

“I considered switching out of my STEM major. I was still going to be in STEM but I did consider switching my major from biochemistry to bio because there was a period where it was really hard and I was like “I don’t know if I can do this. I don’t know if I can do this.” Then, I got my mentor who has the same major as me and I was like “I think I can keep going. I think I can do it.”

In support of the findings on Connection through Shared Cultural Experiences, mentees found resilience dependent on context. In this case, being surrounded by other Latinas within the college context (resilience model; ) promoted their resilience.

5.3. Moving from Mentorship into Friendship

Beyond academics, many of the participants recalled being able to discuss different life experiences and personal stories during their meetings. As they became more familiar with each other, conversations naturally expanded to include childhood memories, current relationships, and life advice. This ability to quickly build rapport strengthened the trust between mentees and mentors, enabling them to openly discuss their challenges and explore ways to support one another. Participants often described their relationships as evolving into genuine friendships.

The participants felt like they were building friendships in their mentor/mentee relationships, with a mentor even mentioning a sisterly/familial bond being made between her and her mentee. One mentee described her mentor as an “older sister” whom they felt like they could call to talk about their shared college experiences. Many participants reflected on how their initial, formal mentor/mentee relationship grew into a close, enduring friendship that extended beyond the bounds of the mentorship program. The mentor from pair 1 described her experience:

“She’s my friend. I love her, queen. I feel like it’s just going to be a connection of a lifetime. It’s not like we’re super best friends and we text all the time, but I try to reach out as many times as I can, and it was really sad when we had our last lunch. So, I feel like I did help her a lot because she continues to look for me.”

After peer mentors and their mentees established initial connections rooted in shared experiences and identities, their relationships deepened into meaningful friendships. Through ongoing conversations about their home lives, college experiences, and community contexts (resilience model; ), they continued to strengthen these bonds, which in turn supported their resilience in their STEM programs.

6. Discussion

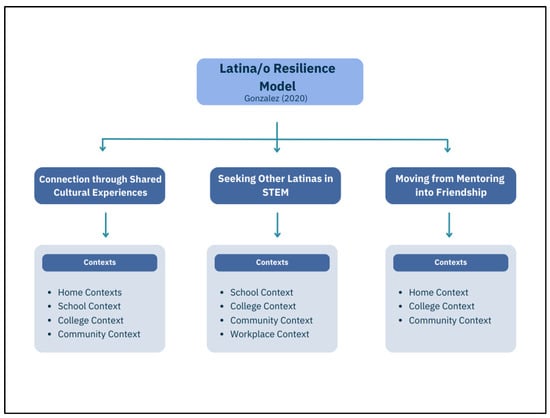

The present study was guided by the following research question: What successful peer mentoring strategies do Latinas develop in their pursuit of a college STEM degree at an HSI in Texas? Analysis of the collected data revealed that Latinas participating in formal mentorship programs intentionally sought to build meaningful relationships, connections they might not otherwise find as women and Latinas in STEM. According to the Latina participants, three key peer mentoring strategies were identified: connection through shared cultural experiences, seeking Latinas in STEM, and transforming mentorship into friendship. These strategies were also seen in various contexts of these women’s lives (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Findings displayed through a Conceptual Model Map. The Latina/o Resilience model () was utilized.

When forming connections through shared cultural experiences, participants frequently shared stories about their home lives, community moments, and academic journeys. Their Latina identity permeated nearly every aspect of their lives, shaping how they experienced the world. Finding others with similar backgrounds and common experiences fostered a sense of extended community and support. Through shared experiences, these Latinas combined their desire for connection with their resilience, reinforcing their persistence in STEM programs (). With Hispanic/Latina women comprising a small percentage of all STEM-related jobs, Latinas in undergraduate STEM programs actively sought mentorship, representation, and community (). Aware of their underrepresentation, they navigated a ‘borderland’ space where their identities as women, Latinas, and members of a male-dominated field intersected (). In their search for connection and support, they sought out fellow Latinas across academic and professional settings, fostering a sense of belonging throughout their educational and career journeys.

By seeking out Latinas with shared experiences, particularly in STEM fields, these women forged bonds that often evolved from mentorship into friendship. These peer mentoring relationships appear to counteract the effects of the gendered and exclusionary STEM field described by (), providing Latinas with both social and emotional support that lessens the isolating ‘dude culture’ in many STEM environments. Their relationships, rooted in a strong sense of community, underscored the cultural and communal assets that shaped their experiences at home, in college, and beyond. They viewed their values, experiences, and knowledge as strengths that fostered meaningful friendships. In other words, resilience, through shared culture and context, was brought to the forefront during this mentorship experience. Ultimately, this aligns with ’ () findings that these women actively demonstrated resilience, shaped by their Hispanic/Latine cultural upbringing, family and community experiences, and higher education journeys. By drawing on cultural elements, ranging from cultural expressions to shared identities, they continuously built resilience within the framing of the strengths of their Latine culture to navigate the challenges of being Latinas in STEM (). When Latinas find mentors who share their language, family values, and lived experiences, mentorship becomes more than academic guidance; it becomes a source of identity affirmation, community, resilience, and resistance against isolation.

6.1. Limitations

Despite the valuable insights gained from this study, a couple of limitations should be acknowledged. Demographic data of mentorship participants was not collected, including whether parents or siblings completed a college degree. However, we learned through the focus groups that several participants were first-generation college students. Another limitation was that HSI context was not directly addressed in the data collection, for example, utilizing HSI-specific questions during the focus groups.

6.2. Future Directions

Based on the results of this study, future research could explore the HSI context further. Though the data for this study was collected in an institution that has been a diverse HSI for over a decade, directly asking questions about the “serving” aspect of being an HSI could offer key insights on how HSI status influences student experiences. Nonetheless, the lack of focus on HSI status at this point promotes future research on peer mentoring experiences and participants’ background in any type of higher education instituion.

Therefore, most importantly, this program demonstrated the value and significance of pairing mentors and mentees by shared characteristics, resulting in a culturally responsive and welcoming environment. For successful replication, practitioners at other institutions should consider pairing mentors and mentees by similar backgrounds, including STEM major and other factors, such as income status. This can be encouraged in HSIs and non-HSIs alike.

7. Conclusions

As scholars and practitioners of higher education, it is critical that we engage in research surrounding the experiences of Latinas, particularly those in STEM fields. This study explored the peer mentoring strategies that Latinas develop in pursuit of STEM degrees at an HSI. Through focus group interviews and written reflections, we identified three peer mentorship success strategies that served as key mechanisms of resilience and thus persistence in STEM: (1) mentorship is rooted in shared cultural identity (connection through shared culture), (2) peer support with those of similar backgrounds is key (seeking other Latinas in STEM), and (3) emotional connection enhances the peer mentorship (transforming mentorship into friendship). These relationships offered a sense of belonging and cultural affirmation. Shared language, familial values, and academic challenges became points of connection that helped mentors and mentees form meaningful bonds.

These findings align with and expand the Latina/o resilience model (), demonstrating how Latinas actively draw from their community cultural wealth to succeed in fields where they are often underrepresented. Addressing the underrepresentation of Latinas in STEM could have far-reaching benefits, including expanding a larger pool of candidates for important emerging STEM roles, fostering a more diverse workforce, and strengthening the U.S. economy through innovation in STEM industries. Despite their underrepresentation in research on STEM degree retention and attainment, Latina students bring unique assets to their undergraduate experiences. For higher education practitioners, this highlights the importance of designing mentorship programs that intentionally connect students through shared background and cultural context, not only to improve retention but also to strengthen a sense of belonging, creating a space of mentoring and support. By understanding both the challenges they face and the strengths they contribute, universities can develop more effective strategies to support the success of Latina students in completing their degrees, helping them thrive in STEM careers after graduation, and move closer to building inclusive academic and workforce environments where all students can excel ().

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.A.W.; methodology, J.A.W., J.C., E.M.G. and E.C.P.; formal analysis, J.A.W., J.C. and E.C.P.; investigation, J.A.W., J.C. and E.C.P.; resources, E.M.G.; data curation, J.C. and J.A.W.; writing—original draft preparation, J.A.W.; writing—review and editing, J.A.W., E.C.P. and E.M.G.; supervision, E.M.G.; project administration, E.C.P. and E.M.G.; funding acquisition, E.M.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Science Foundation, award numbers 2045802 and 2343939.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Institutional Review Board at the University of Houston reviewed and approved the study before research began; the IRB identification number was STUDY00000985 and the approval date was 16 May 2018. Due to a transition to new institution in the midst of research activities, the IRB at Texas A&M University also reviewed and approved the study before research began post-transition; the IRB identification number was IRB2023-1016 with approval date 28 November 2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects (student participants) involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to confidentiality restrictions. Raw data sets are interview transcripts which contain potentially identifiable information and thus are protected, as guaranteed to participants. The authors are open to discussing the data further if contacted via email.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Abraído-Lanza, A. F., Echeverria, S. E., Flórez, K. R., & Mendoza-Grey, S. (2022). Latina women in academia: Challenges and opportunities. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 876161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre, H. C. C., & Banda, R. M. (2019). Importance of mentoring for Latina college students pursuing STEM degrees at HSIs. In Crossing borders/crossing boundaries (pp. 111–127). Texas A&M University–Corpus Christi. [Google Scholar]

- Byars-Winston, A., & Dahlberg, M. L. (Eds.). (2019). The science of effective mentorship in STEMM. The National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- Contreras Aguirre, H. C., Gonzalez, E., & Banda, R. M. (2020). Latina college students’ experiences in STEM at Hispanic-serving institutions: Framed within Latino critical race theory. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 33(8), 810–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuellar, M. (2014). The impact of Hispanic-Serving Institutions (HSIs), emerging HSIs, and Non-HSIs on latina/o academic self-concept. Review of Higher Education, 37(4), 499–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, C. (2009). Transcription: Imperatives for qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 8(2), 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayton, B., Gonzalez-Vasquez, N., Martinez, C. R., & Plum, C. (2004). Hispanic-serving institutions through the eyes of students and administrators. New Directions for Student Services, 2004(105), 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennehy, T. C., & Dasgupta, N. (2017). Female peer mentors early in college increase women’s positive academic experiences and retention in engineering. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(23), 5964–5969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desmond, M., & Turley, R. N. L. (2009). The role of familism in explaining the Hispanic-White College application gap. Social Problems, 56(2), 311–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglass, A. G., Smith, D. L., & Smith, L. J. (2013). An exploration of the characteristics of effective undergraduate peer-mentoring relationships. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 21(2), 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, S. T., & Barth, J. M. (2023). Career identities and gender-STEM stereotypes: When and why implicit gender-STEM associations emerge and how they affect women’s college major choice. Sex Roles, 89(1/2), 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eller, L. S., Lev, E. L., & Feurer, A. (2014). Key components of an effective mentoring relationship: A qualitative study. Nurse Education Today, 34(5), 815–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, R. (2010). The good daughter dilemma: Latinas managing family and school demands. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 9(4), 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, J., & Evans-Winters, V. E. (2022). Introduction to intersectional qualitative research. SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Estrada, M., Hernandez, P. R., & Schultz, P. W. (2018). A longitudinal study of how quality mentorship and research experience integrate underrepresented minorities into STEM careers. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 17(1), ar9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, A., Monarrez, A., & Morales, D. X. (2024). Strategic familismo: How Hispanic/Latine students negotiate family values and their stem careers. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 38(2), 180–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, R., Kennedy, B., & Funk, C. (2021). Stem jobs see uneven progress in increasing gender, racial and ethnic diversity report. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2021/04/01/stem-jobs-see-uneven-progress-in-increasing-gender-racial-and-ethnic-diversity/ (accessed on 20 July 2024).

- Funk, C., & Lopez, M. H. (2022). 5. Many Hispanic Americans see more representation, visibility as helpful for increasing diversity in science. Hispanic Americans’ Trust in and Engagement with Science. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2022/06/14/many-hispanic-americans-see-more-representation-visibility-as-helpful-for-increasing-diversity-in-science/ (accessed on 20 July 2024).

- Garcia, G. A. (2016). Exploring student affairs professionals’ experiences with the campus racial climate at a Hispanic Serving Institution (HSI). Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 9(1), 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, P., Stewart, K., Treasure, E., & Chadwick, B. (2008). Methods of data collection in qualitative research: Interviews and focus groups. British Dental Journal, 204(6), 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez Cervantes, A. (2010). Breaking stereotypes by obtaining a higher education: Latinas’ family values and tradition on the school institution. McNair Scholars Journal, 14(1), 23–54. Available online: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/mcnair/vol14/iss1/4 (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Gonzalez, E. (2020). Foreword: Understanding Latina/o resilience. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 33(8), 791–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, E., Aguirre, C. C., & Myers, J. (2022). Persistence of Latinas in STEM at an R1 higher education institution in Texas. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 21(2), 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, E., Ortega, G., Molina, M., & Lizalde, G. (2020). What does it mean to be a Hispanic-serving institution? Listening to the Latina/o/x voices of students. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 33(8), 796–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, E., Perez, E. C., Sanchez Hernandez, I., Deis, C., & Corral, J. (in press). Embracing Latina Learners’ Assets in STEM (ELLAS) at a Hispanic serving institution. Journal of Women and Minorities in Science and Engineering.

- Gonzalez, E. M., & Perez, E. C. (2024). Latina resilience in engineering: Strategies of success in a Hispanic Serving Institution. In L. Perez-Felkner, S. L. Rodriguez, & C. Fluker (Eds.), Latin* students in engineering: An intentional focus on a growing population (pp. 213–234). Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hardway, C., & Fuligni, A. J. (2006). Dimensions of family connectedness among adolescents with Mexican, Chinese, and European backgrounds. Developmental Psychology, 42(6), 1246–1258. Available online: https://content.apa.org/journals/dev/42/6/1246 (accessed on 5 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Hispanic Heritage Foundation & Student Research Foundation. (2020). Hispanics & STEM: Hispanics are underrepresented in STEM today, but Gen Z’s interest can change the future. Available online: https://hispanicheritage.org/national-survey-highlights-troubling-gaps-and-big-opportunities-to-strengthen-hispanic-stem-pipeline/ (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Holland, J. M., Major, D. A., & Orvis, K. A. (2012). Understanding how peer mentoring and capitalization link STEM students to their majors. The Career Development Quarterly, 60(4), 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalpokaite, N., & Radivojevic, I. (2019). Demystifying qualitative data analysis for novice qualitative researchers. The Qualitative Report, 24(13), 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, E. (2024). Most Hispanic Americans say increased representation would help attract more young Hispanics to stem. Short Reads. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2024/10/15/most-hispanic-americans-say-increased-representation-would-help-attract-more-young-hispanics-to-stem/ (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Korhonen, V. (2024). U.S. Hispanic population by occupation 2021. Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/259818/hispanic-population-of-the-us-by-occupation/ (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Lisberg, A., & Woods, B. (2018). Mentorship, mindset and learning strategies: An integrative approach to increasing underrepresented minority student retention in a STEM undergraduate program. Journal of STEM Education, 19(3), 14–20. Available online: https://www.jstem.org/jstem/index.php/JSTEM/article/view/2280 (accessed on 20 July 2024).

- Lopez, E. J., Basile, V., Landa-Posas, M., Ortega, K., & Ramirez, A. (2019). Latinx students’ sense of familismo in undergraduate science and engineering. Review of Higher Education, 43(1), 85–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, M., Dobbs-Oates, J., Kunberger, T., & Greene, J. (2021). The peer mentor experience: Benefits and challenges in undergraduate programs. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 29(1), 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Master, A., Meltzoff, A. N., & Cheryan, S. (2021). Gender stereotypes about interests start early and cause gender disparities in computer science and engineering. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(48), e2100030118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKinsey, E. (2016). Faculty mentoring undergraduates: The nature, development, and benefits of mentoring relationships. Teaching and Learning Inquiry, 4(1), 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, S. A., & Winch, P. J. (2018). Systematic debriefing after qualitative encounters: An essential analysis step in applied qualitative research. BMJ Global Health, 3(5), e000837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R. A., Vaccaro, A., Kimball, E. W., & Forester, R. (2021). “It’s dude culture”: Students with minoritized identities of sexuality and/or gender navigating STEM majors. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 14(3), 340–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, D. L. (1997). Focus groups as qualitative research (2nd ed.). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Moschetti, R. V., Plunkett, S. W., Efrat, R., & Yomtov, D. (2017). Peer mentoring as social capital for Latina/o college students at a Hispanic-Serving Institution. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 17(4), 375–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moslimani, M., & Mukherjee, S. (2024). Half of Latinas say Hispanic women’s situation has improved in the past decade and expect more gains. Hispanics/Latinos & Education. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/race-and-ethnicity/2024/05/15/half-of-latinas-say-hispanic-womens-situation-has-improved-in-the-past-decade-and-expect-more-gains/#:~:text=At%2022.2%20million%2C%20Latinas%20account,female%20racial%20or%20ethnic%20group (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Moslimani, M., & Noe-Bustamante, L. (2023). Facts on Latinos in the U.S. fact sheet. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/race-and-ethnicity/fact-sheet/latinos-in-the-us-fact-sheet/#:~:text=There%20were%2062.5%20million%20Latinos,origin%20groups%20in%20the%20U.S.%E2%80%9D (accessed on 20 July 2024).

- National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). (2022). Digest of education statistics, 2022: Table 318.45. Number and percentage distribution of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) degrees/certificates conferred by postsecondary institutions, by race/ethnicity, level of degree/certificate, and sex of student: Academic years 2011–2012 through 2020–2021. U.S. Department of Education. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d22/tables/dt22_318.45.asp (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Nora, A., & Crisp, G. (2009). Hispanics and higher education: An overview of research, theory, and practice. In Higher education: Handbook of theory and research (pp. 317–353). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwuegbuzie, A. J., Dickinson, W. B., Leech, N. L., & Zoran, A. G. (2009). A qualitative framework for collecting and analyzing data in focus group research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 8(3), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaganas, E. C., Sanchez, M. C., Molintas, M. P., & Caricativo, R. D. (2017). Reflexivity in qualitative research: A journey of learning. The Qualitative Report, 22(2), 426–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peralta, C., Caspary, M., & Boothe, D. (2013). Success factors impacting Latina/o persistence in higher education leading to STEM opportunities. Cultural Studies of Science Education, 8(4), 905–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, E. C., Gonzalez, E. M., White, J. A., Deis, C., Pacheco, H., & Corral, J. (2024). Servingness in action: Peer mentoring among Latinas in STEM. In Student success and intersectionality at Hispanic-Serving Institutions: Policy and practice (pp. 65–75). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rincón, B. E., Fernández, É., & Dueñas, M. C. (2020). Anchoring comunidad: How first- and continuing-generation Latinx students in STEM engage community cultural wealth. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 33(8), 840–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rincón, B. E., & Rodriguez, S. (2020). Latinx students charting their own STEM pathways: How community cultural wealth informs their STEM identities. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 20(2), 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, S., Cunningham, K., & Jordan, A. (2019). STEM identity development for Latinas: The role of self- and outside recognition. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 18(3), 254–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saffie-Robertson, M. C. (2020). It’s not you, it’s me: An exploration of mentoring experiences for women in STEM. Sex Roles, 83(9), 566–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña, J. (2021). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. SAGE Publications Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Santiago, D., Arroyo, C., & Cuellarsola, L. (2024). Latinos in higher education: 2024 compilation of fast facts. Excelencia in Education. [Google Scholar]

- Shaju, A., Jomy, C. R., Jaheer Mukthar, K. P., & Alhashimi, R. (2024). Empowering women in STEM: Addressing challenges, strategies, and the gender gap. In Business development via AI and digitalization: Volume 2 (pp. 1103–1112). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods (3rd ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Yosso, T. J. (2005). Whose culture has capital? A critical race theory discussion of community cultural wealth. Race Ethnicity and Education, 8(1), 69–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).