Early Career Teacher Preparedness to Respond to Student Mental Health

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Child and Adolescent Mental Health

1.2. The Context of Early Career Teaching

1.3. Initial Teacher Education

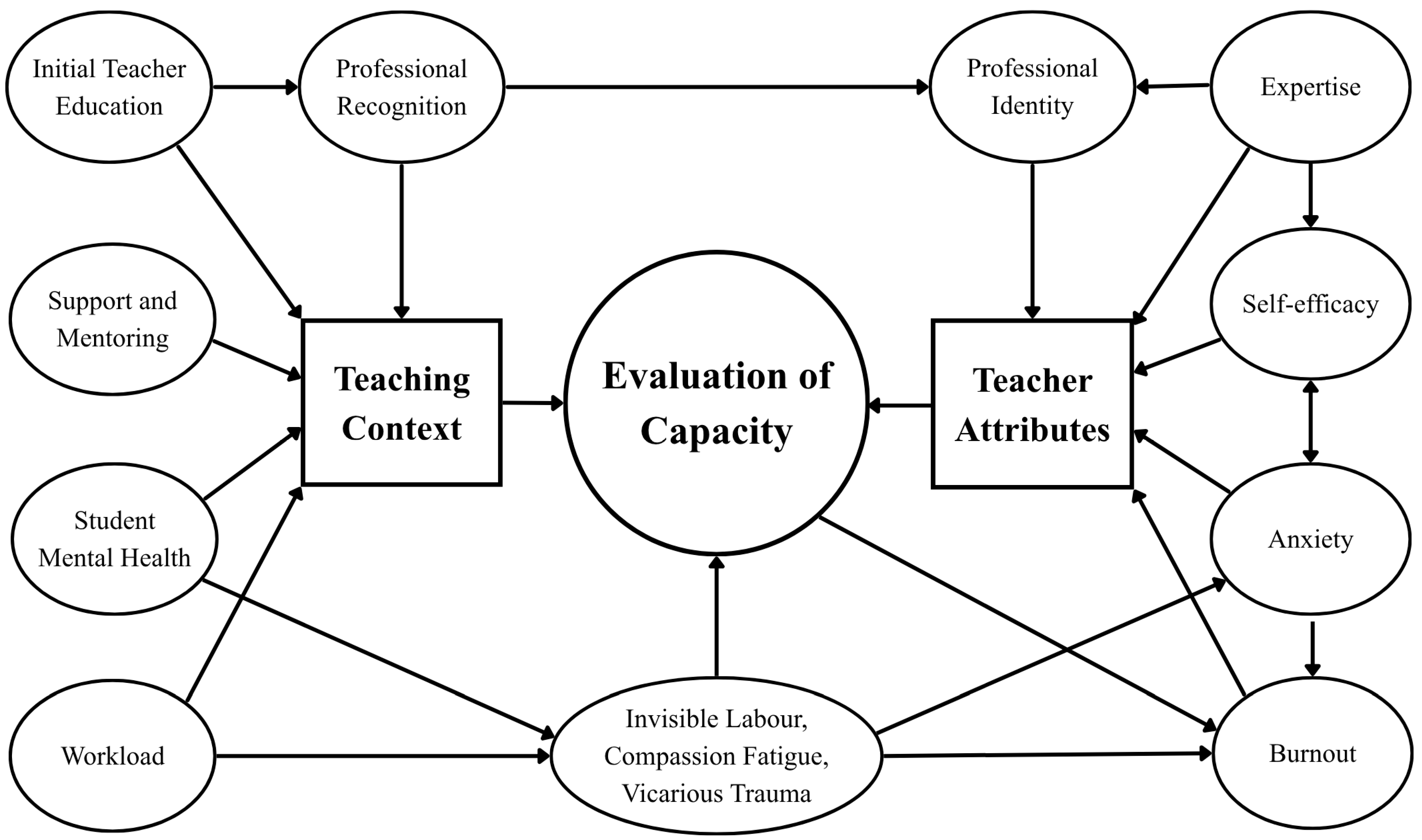

1.4. Theoretical Framework

- RQ1

- To what extent do preservice teachers demonstrate dispositional profiles that are likely to be adaptive in their future management of mental health?

- RQ2

- To what extent do ECT report a sense of preparedness to support students with potential mental health challenges?

- RQ3

- To what extent do ECT report that student mental health is part of their role and/or impacts their teaching practice?

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Study 1

3.1.1. Study 1 Method

3.1.2. Study 1 Results

3.1.3. Study 1 Findings

3.2. Study 2

3.2.1. Study 2 Method

3.2.2. Study 2 Results

Survey Results

Interview Results

3.2.3. Study 2 Findings

4. Discussion and Implications

- 1.

- School-based mental health screening

- 2.

- Acknowledge classroom complexities

- 3.

- Acknowledgment of vicarious trauma

- 4.

- Provision of targeted professional development

- 5.

- Formally recognise the role of the teacher

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACARA | Australian Curriculum and Regulation Authority |

| AITSL | Australian Institute for Teaching School Leadership |

| ECT | Early career teachers |

| NESA | New South Wales Education Standards Authority |

| SMH | Student mental health |

Appendix A

Overview of Instruments Included in Dispositional Survey. All Items Were Rated on a Six-Point Scale of Agreement

| Instrument | Sub-Scales Selected | Original Number of Items | Items Included | Example Item | Cronbach’s α |

| Self-efficacy Adapted from Schwarzer and Jerusalem (1995) | (Single scale) | 10 | 6 | I am certain that I can accomplish my academic goals | 0.834 |

| Need for cognition * Adapted from Cacioppo et al. (1984) | (Single scale) | 10 | 6 | I only think as hard as I have to | 0.812 |

| Metacognitive awareness Adapted from Schraw and Dennison (1994) | (Utilised as a single scale) | 18 | 8 | I understand my intellectual strengths and weaknesses | 0.832 |

| Tolerance of Uncertainty Adapted from Carleton et al. (2007) | Prospective anxiety | 7 | 4 | One should always look ahead so as to avoid surprises | 0.724 |

| Inhibitory anxiety | 5 | 4 | The smallest doubt can stop me from acting | 0.875 | |

| Fear of Failure Adapted from Choi (2021) | Feelings of shame | 9 | 3 | I’m embarrassed when I’m wrong | 0.902 |

| Performance avoidance | 7 | 3 | I avoid attempting to do something when I feel uncertain | 0.908 | |

| Reactions to Daily Events Adapted from Greenglass et al. (1999) | Proactive coping | 14 | 5 | I turn obstacles into positive experiences and achievements | 0.808 |

| Reflective coping | 11 | 5 | I tackle a problem by thinking about realistic alternatives | 0.748 | |

| Epistemic Beliefs Adapted from Bendixen et al. (1998), as per Spray (2018) | Structure of knowledge | 8 | 5 | Lecturers should focus on facts instead of theories | 0.655 |

| Acquisition of knowledge | 11 | 5 | If you don’t learn something quickly, you won’t ever learn it | 0.807 | |

| Epistemic emotions Pekrun et al. (2017) | Positive epistemic emotion | 3 | 3 | When I am learning I often feel curious | 0.672 |

| Negative epistemic emotion | 4 | 4 | When I am learning I often feel frustrated | 0.740 | |

| * reverse scored. | |||||

Appendix B

Overview of ECT Interview Participants’ Age, Gender and School Type

| Pseudonym | Age | Gender | Teaching Experience | School Type | Geographical Context | Employment Type |

| Henry | 25–34 | Male | 0–5 years | Government | Urban | Temporary |

| Ira | 25–34 | Female | 0–5 years | Government | Rural | Full-time (Permanent) |

| Jamie | 25–34 | Male | 0–5 years | Government | Urban | Temporary |

| Lola | 25–34 | Female | 0–5 years | Government | Rural | Temporary |

| Noah | 25–34 | Male | 0–5 years | Independent | Urban | Full-time (Permanent) |

| Piper | 25–34 | Female | 0–5 years | Government | Urban | Temporary |

| Roy | 35–44 | Male | 0–5 years | Catholic | Urban | Temporary |

| Sophia | 18–24 | Female | 0–5 years | Government | Urban | Temporary |

| 1 | 80 for undergraduate ITE programmes and 60 for postgraduate ITE programmes. |

| 2 | The development and validation of this instrument is being written up separately for publication. |

References

- Ancarani, F., Garijo Añaños, P., Gutiérrez, B., Pérez-Nievas, J., Vicente-Rodríguez, G., & Gimeno Marco, F. (2025). The effectiveness of debriefing on the mental health of rescue teams: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(4), 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angermeyer, M., Schindler, S., Matschinger, H., Baumann, E., & Schomerus, G. (2023). The rise in acceptance of mental health professionals: Help-seeking recommendations of the German public 1990–2020. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 32(11), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). (2008). National survey of mental health and wellbeing: Summary of results. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/mental-health/national-study-mental-health-and-wellbeing/2007 (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). (2022). National study of mental health and wellbeing. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/mental-health/national-study-mental-health-and-wellbeing/latest-release (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Australian Council of Social Services. (2024). Budget priorities statement 2025-6: Submission to the treasurer. Available online: https://www.acoss.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/ACOSS_Budget-Priorities-Statement-2025-26-FINAL-14.1.2025.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership. (2025a). ATWD national trends: Teacher workforce (June 2025 ed., 2019–2023). Available online: https://www.aitsl.edu.au/research/australian-teacher-workforce-data/atwd-reports/national-trends-teacher-workforce-jun2025 (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership. (2025b). Spotlight: Highly accomplished and lead teachers. Available online: https://www.aitsl.edu.au/docs/default-source/research-evidence/spotlight/halt.pdf (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL). (n.d.). Australian professional standards for teachers. Available online: https://www.aitsl.edu.au/standards (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL). (2024). Framework for teacher registration in Australia. Available online: https://www.aitsl.edu.au/teach/national-review-of-teacher-registration/framework-for-teacher-registration-in-australia (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). (2025). General practice, allied health and other primary care services. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/primary-health-care/general-practice-allied-health-primary-care (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Baker, S., & Burke, R. (2023). Questioning care in higher education: Resisting definitions as radical. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, A., & de Vries, J. (2020). Job demands-resources theory and self-regulation: New explanations and remedies for job burnout. Anxiety, Stress and Coping, 43, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, F., & Freeman, T. (2025). Actions required to reduce rising health inequities in Australia. The Lancet Public Health, 10(7), 544–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendixen, L. D., Schraw, G., & Dunkle, M. E. (1998). Epistemic Beliefs Inventory (EBI) [Database record]. PsycTESTS. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, E., Reupert, A., Allen, K.-A., & Oades, L. G. (2022). A systematic review of the long-term benefits of school mental health and wellbeing interventions for students in Australia. Frontiers in Education, 7, 986391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, D., Hine, G., & Lavery, S. (2023). Exploring challenges faced by early career primary school teachers: A qualitative study. Australian Journal of Teacher Education (Online), 48(8), 1–20. Available online: https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.T2024110300002700706294193. [CrossRef]

- Brandenburg, R., Larsen, E., Simpson, A., Sallis, R., & Tran, D. (2024). ‘I left the teaching profession… and this is what I am doing now’: A national study of teacher attrition. The Australian Educational Researcher, 51, 2381–2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buehl, M., & Alexander, P. (2005). Motivation and performance differences in students’ domain-specific epistemological belief profiles. American Educational Research Journal, 42(4), 697–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppo, J. T., & Petty, R. (1982). The need for cognition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 42(1), 116–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppo, J. T., Petty, R. E., & Kao, C. F. (1984). The efficient assessment of need for cognition. Journal of Personality Assessment, 48(3), 306–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantwell, R., Bourke, G., Scevak, J., Holbrook, A., & Budd, J. (2017). Doctoral candidates as learners: A study of individual differences in responses to learning and its management. Studies in Higher Education, 42(1), 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carleton, R., Norton, M., & Asmundson, G. (2007). Fearing the unknown: A short version of the intolerance of uncertainty scale. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 21, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, B. (2021). I’m afraid of not succeeding in learning: Introducing an instrument to measure higher education students’ fear of failure in learning. Studies in Higher Education, 46(11), 2107–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuervo, H., & Vera-Toscano, E. (2025). Teacher retention and attrition: Understanding why teachers leave and their post-teaching pathways in Australia. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Education, Australian Government. (2022). National teacher workforce action plan. Available online: https://www.education.gov.au/national-teacher-workforce-action-plan (accessed on 22 November 2024).

- De Rubeis, V., Repchuck, R., Halladay, J., Cost, K., Thabane, L., & Georgiades, K. (2024). The association between teacher distress and student mental health outcomes: A cross-sectional study using data from the school mental health survey. BMC Psychology, 12, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibley, L., Dickerson, S., Duffy, M., & Vandermause, R. (2020). Doing hermeneutic phenomenological research: A practical guide. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Disney, G., Yang, Y., Summers, P., Devine, A., Dickinson, H., & Kavanagh, A. (2025). Social inequalities in eligibility rates and use of the Australian National Disability Insurance Scheme, 2016–2022: An administrative data analysis. The Medical Journal of Australia, 222(3), 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entwistle, N., & McCune, V. (2013). The disposition to understand for oneself at university: Integrating learning processes with motivation and metacognition. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 83(2), 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feuer, B. S. (2021). First responder peer support: An evidence-informed approach. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 36(3), 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foulkes, L., & Andrews, J. (2023). Are mental health awareness efforts contributing to the rise in reported mental health problems? A call to test the prevalence inflation hypothesis. New Ideas in Psychology, 69, 101010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, E., & Spray, E. (2024, April 11–13). Dispositions towards learning in higher education: The impacts of learning beliefs on academic achievement [Paper presentation]. Australasian Experimental Psychology Conference (EPC) 2024, Adelaide, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Gilham, C., Neville-MacLean, S., & Atkinson, E. (2021). Effect of online modules on pre-service teacher mental health literacy and efficacy toward inclusive practices. Canadian Journal of Education/Revue canadienne de l’éducation, 44(2), 559–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granziera, H., Collie, R. J., Roberts, A., Corkish, B., Tickell, A., Deady, M., O’Dea, B., & Tye, M. (2025). Teachers’ workload, turnover intentions, and mental health: Perspectives of Australian teachers. Social Psychology of Education, 28, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, C., Wilcox, G., & Nordstokke, D. (2017). Teacher mental health, school climate, inclusive education and student learning: A review. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 58(3), 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenglass, E., Schwarzer, R., Jakubiec, D., Fiskenbaum, L., & Taubert, S. (1999, July 12–14). The Proactive Coping Inventory: A multidimensional research instrument [Paper presentation]. International Conference of the Stress and Anxiety Research Society (STAR), Cracow, Poland. Available online: https://estherg.info.yorku.ca/files/2014/09/pci.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2024).

- Gunawardena, H., Leontini, R., Nair, S., Cross, S., & Hickie, I. (2024). Teachers as first responders: Classroom experiences and mental health training needs of Australian schoolteachers. BMC Public Health, 24(1), 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagermoser Sanetti, L. M., Boyle, A. M., & Magrath, E. (2021). Intervening to decrease teacher stress: A review of current research and new directions. Contemporary School Psychology, 25, 416–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, L., Disney, L., Bussey, K., & Geng, G. (2024). “Disregarded and undervalued”: Early childhood teacher’s experiences of stress and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic. Early Years, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepburn, S., Carroll, A., & McCuaig, L. (2021). A complementary intervention to promote wellbeing and stress management for early career teachers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(12), 6320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houdyshell, M., Kratt, D., & Greene, J. (2021). Student teachers with mental health conditions share barriers to success: A case study. The Qualitative Report, 26(1), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, N., & Wigelsworth, M. (2016). Making the case for universal school-based mental health screening. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties. EarlyView, 21, 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariou, A., Koutsimani, P., Montgomery, A., & Lainidi, O. (2021). Emotional labor and burnout among teachers: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(23), 12760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kearney, S. (2015). Reconceptualizing beginning teacher induction as organizational socialization: A situated learning model. Cogent Education, 2(1), 1028713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, C. M., Mithen, J. M., Fischer, J. A., Kitchener, B. A., Jorm, A. F., Lowe, A., & Scanlan, C. (2011). Youth mental health first aid: A description of the program and an initial evaluation. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 5(1), 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, N., Cespedes, M., Clarà, M., & Danaher, P. A. (2019). Early career teachers’ intentions to leave the profession: The complex relationships among preservice education, early career support, and job satisfaction. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 44(3), 93–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R. C., Berglund, P., Demler, O., Jin, R., Merikangas, K. R., & Walters, E. E. (2005). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 62(6), 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampert, J., McPherson, A., Casanueva Baptista, A., & Hawkins, A. (2025). The hidden work of incidental mentoring in the hardest-to-staff schools. Education Sciences, 15(7), 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, D., Johnson, S., Hafekost, J., Boterhoven De Haan, K., Sawyer, M., Ainley, J., & Zubrick, S. R. (2015). The mental health of children and adolescents. Report on the second Australian child and adolescent survey of mental health and wellbeing. Department of Health. [Google Scholar]

- Ledger, S., Ure, C., Burgess, M., & Morrison, C. (2020). Professional experience in Australian initial teacher education: An appraisal of policy and practice. Higher Education Studies, 10(4), 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonka, K., Ketonen, E., & Vermunt, J. (2021). University students’ epistemic profiles, conception of learning and academic performance. Higher Education, 81(3), 775–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, S., & Matas, C. P. (2015). Teacher attrition and retention research in Australia: Towards a new theoretical framework. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 40(11), 44–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, D., & Oancea, A. (2021). Teacher education research, policy and practice: Finding future research directions. Oxford Review of Education, 47(1), 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCallum, F., & Hazel, S. (2016). The experience is in the journey: An appreciative case study investigating early career teachers’ employment in rural schools. Australian and International Journal of Rural Education, 26(2), 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGorry, P., Mei, C., Dalal, N., Alvarez-Jiminez, M., Blakemore, S., Browne, V., Dooley, B., Hickie, I., Jones, P., McDaid, D., Mihalopolous, C., Wood, S., Azzouzi, F., Fazio, J., Gow, E., Hanjabam, S., Hayes, A., Morris, A., Pang, E., … Killackey, E. (2024). The Lancet Psychiatry Commission on youth mental health. The Lancet Psychiatry Commissions, 11(9), 731–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, J. J., Al-Hamzawi, A., Alonso, J., Altwaijri, Y., Andrade, L. H., Bromet, E. J., Bruffaerts, R., de Almeida, J. M. C., Chardoul, S., Chiu, W. T., Degenhardt, L., Demler, O. V., Ferry, F., Gureje, O., Haro, J. M., Karam, E. G., Karam, G., Khaled, S. M., Kovess-Masfety, V., … WHO World Mental Health Survey Collaborators. (2023). Age of onset and cumulative risk of mental disorders: A cross-national analysis of population surveys from 29 countries. Lancet Psychiatry, 10(9), 668–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLean, L., Abry, T., Taylor, M., & Connor, C. M. (2018). Associations among teachers’ depressive symptoms and students’ classroom instructional experiences in third grade. Journal of School Psychology, 69, 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, L., & Connor, C. M. (2015). Depressive symptoms in third-grade teachers: Relations to classroom quality and student achievement. Child Development, 86(3), 945–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLean, L., & Connor, C. M. (2018). Relations between third grade teachers’ depressive symptoms and their feedback to students, with implications for student mathematics achievement. School Psychology Quarterly, 33(2), 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mental Health Australia. (2025, June). National child and youth mental health priorities. Available online: https://www.mentalhealthaustralia.org.au/sites/default/files/docs/mental_health_australia_statement_-_national_child_and_youth_mental_health_priorities_-_june_2025_health_and_mental_health_ministers_meeting_.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2024).

- National Mental Health Commission. (2021). The national children’s mental health and wellbeing strategy: Full report. Available online: https://www.mentalhealthcommission.gov.au/sites/default/files/2024-03/national-children-s-mental-health-and-wellbeing-strategy---full-report.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2024).

- NSW Education Standards Authority (NESA). (2025). Content criteria: Student/Child mental health. Available online: https://c.educationstandards.nsw.edu.au/wps/wcm/connect/bd75d336-2f8c-40a5-9678-95bfd8e02856/content-criteria-student-child-mental-health-proficient-teacher.pdf?MOD=AJPERES (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- NSW Premier’s Department. (2024, November 19). Public schools—Teachers: People matter employee survey. NSW Government. Available online: https://www.nsw.gov.au/departments-and-agencies/premiers-department/pmes/education (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- NSW Teachers Federation. (2024, September 15). Kids the victims of teaching aid cuts. Available online: https://www.nswtf.org.au/news/2024/09/15/kids-the-victims-of-teaching-aid-cuts/ (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- Nygaard, M., Ormiston, H., Renshaw, T., Carlock, K., & Komer, J. (2024). School mental health care coordination practices: A mixed methods study. Children and Youth Services Review, 157, 107426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberg, G., Macmahon, S., & Carroll, A. (2025). Assessing the interplay: Teacher efficacy, compassion fatigue, and educator well-being in Australia. Australian Educational Researcher, 52, 1105–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberle, E., & Schonert-Reichl, K. A. (2016). Stress contagion in the classroom? The link between classroom teacher burnout and students’ physiological stress. Social Science & Medicine, 159, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2021). A new benchmark for mental health systems: Tackling the social and economic costs of mental ill-health. OECD Health Policy Studies, Issue. O. Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill, J., Hansen, S., & Lewis, E. (2014). Dispositions to teach: Review and synthesis of current components and applications and evidence of impact. Report to the Schooling Policy Group, Ministry of Education. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormiston, H. E., Nygaard, M. A., & Apgar, S. (2022). A Systematic Review of Secondary Traumatic Stress and Compassion Fatigue in Teachers. School Mental Health, 14, 802–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R., Vogl, E., Muis, K., & Sinatra, G. (2017). Measuring emotions during epistemic activities: The epistemically-related emotions scale. Cognition and Emotion, 31(6), 1268–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikić Jugović, I., Marušić, I., & Matić Bojić, J. (2025). Early career teachers’ social and emotional competencies, self-efficacy and burnout: A mediation model. BMC Psychology, 13(9), 1268–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, G., Wu, Y., Wang, W., Lei, R., Zhang, W., Jiang, S., Huang, Y., & Zhang, Z. (2023). Perceived stress and mental health literacy among Chinese preschool teachers: A moderated mediation model of anxiety and career resilience. Psychology Research and Behaviour Management, 16, 3777–3785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahmat, R., Bowshall-Freeman, L., Bissaker, K., Duan, S., Morrissey, C., Winslade, M., Plastow, K., Reid, C., & McLeod, A. (2025). Teaching while learning: Challenges and opportunities for pre-service teachers in addressing Australia’s teaching workforce shortage. Education Sciences, 15(4), 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, S. V. (2023). The Paperwinner’s model in academia and undervaluation of care work. Journal of Academic Ethics, 21, 407–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, R. A. (2021). Retaining women faculty: The problem of invisible labor. Political Science & Politics, 54(3), 504–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schraw, G., & Dennison, R. S. (1994). Assessing metacognitive awareness. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 19, 460–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuck, S., Aubusson, P., Buchanan, J., Varadharajan, M., & Burke, P. F. (2017). The experiences of early career teachers: New initiatives and old problems. Professional Development in Education, 44(2), 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, R., & Jerusalem, M. (1995). Generalized self-efficacy scale. In J. Weinman, S. Wright, & M. Johnston (Eds.), Measures in health psychology: A user’s portfolio. Causal and control beliefs (pp. 35–37). NFER-NELSON. [Google Scholar]

- Shields, R. (2025). Teaching the teacher? How content of Australian initial teacher education programs relates to professional satisfaction across the career. The Australian Educational Researcher, 52, 3731–3759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J., Flowers, P., & Larkin, M. (2009). Interpretative phenomenological analysis. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Spray, E. (2018). A Cross-cultural study of dispositions towards learning [Doctoral dissertation, University of Newcastle]. Open Research Newcastle. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/1959.13/1389330 (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Spray, E. (2022, November 27–December 4). Dispositions towards learning and their relationship to achievement [Paper presentation]. Australian Association of Research in Learning (AARE), University of South Australia. Adelaide, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Spray, E. (2024, December 1–5). Harnessing dispositions towards learning to promote engagement and development [Paper presentation. Australian Association of Research in Learning (AARE), Macquarie University; Sydney, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Spray, E., & Goulding, J. (2024, November 28–29). Leveraging dispositions towards learning: A data-driven intervention [Workshop]. Australasian Learning Analytics Summer Institute (ALASI), Deakin University, Melbourne, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Spray, E., Holbrook, A., Scevak, J., & Cantwell, R. (2023). Dispositions towards learning: The importance of epistemic attributes for postgraduate learners. Studies in Graduate and Postdoctoral Education, 14(3), 347–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subotic-Kerry, M., Borchard, T., Parker, B., Li, S. H., Choi, J., Long, E. V., Batterham, P. J., Whitton, A., Gockiert, A., Spencer, L., & O’Dea, B. (2025). While they wait: A crosssectional survey on wait times for mental health treatment for anxiety and depression for adolescents in Australia. BMJ Open, 15(3), e087342. Available online: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/15/3/e087342 (accessed on 21 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A. (2023). Why are less than 1% of Australian teachers accredited at the top levels of the profession? Available online: https://findanexpert.unimelb.edu.au/news/63137-why-are-less-than-1-of-australian-teachers-accredited-at-the-top-levels-of-the-profession%3F (accessed on 7 April 2024).

- Taylor, G. (2012). Understanding as metaphoric, not a fusion of horizons. In I. F. J. Mootz, & G. H. Taylor (Eds.), Gadamer and ricoeur: Critical horizons for contemporary hermeneutics. Bloomsbury Publishing PLC. [Google Scholar]

- Teach for Australia. (2025). Our programs: Undergraduate teaching program. Available online: https://teachforaustralia.org/our-programs/undergraduate-teaching-program/ (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- University of Sydney. (2021). New study on-the-job program for trainee teachers. Available online: https://www.sydney.edu.au/news-opinion/news/2021/12/16/new-study-on-the-job-program-for-trainee-teachers.html (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- van Manen, M. (2017). But is it phenomenology? Qualitative Health Research, 27(6), 775–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. (2013). Mental health action plan: 2013–2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241506021 (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- World Health Organisation. (2022). Mental disorders. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-disorders (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- World Health Organisation. (2024). Mental health of adolescents. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Wyatt, Z. (2024). Echoes of distress: Navigating the neurological impact of digital media on vicarious trauma and resilience. Medicine and Clinical Science, 6(1), 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment Providers | Mean Days Waited | Standard Deviation | Range (Days) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychologist | 100.1 | 77.25 | 10–365 |

| Psychiatrist | 127.5 | 78.8 | 18–341 |

| School Counsellor | 60.9 | 21 | 8–365 |

| Headspace | 107.6 | 89.44 | 14–365 |

| Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services | 71.6 | 65.52 | 14–304 |

| Paediatrician | 121.9 | 83.85 | 14–365 |

| Inpatient hospital stays | 82.5 | 70.14 | 10–272 |

| Study 1 | Study 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Cohort | Preservice teaching students | In-service and preservice teachers |

| Number of survey responses | 724 | 175 |

| Number of interviews | n/a | 19 |

| Largest age groups | 77% aged 18–21 96% aged 18–29 | 39% aged 25–34 |

| Gender | 73% female | 67% female Male: 31% Non-binary/gender diverse/agender: 1.2% Prefer not to say: 0.6% |

| Primary/Secondary | Primary and secondary | Secondary only |

| State | NSW | NSW |

| Scale | Items | Example Item | Cronbach’s α | Mean | s.d. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-efficacy | 6 | I am certain I can accomplish my academic goals | 0.834 | 4.59 | 0.656 |

| Need for cognition * | 6 | I only think as hard as I have to | 0.812 | 4.24 | 0.823 |

| Prospective anxiety | 4 | One should always look ahead so as to avoid surprises | 0.724 | 4.48 | 0.799 |

| Inhibitory anxiety | 4 | The smallest doubt can stop me from acting | 0.875 | 3.49 | 1.110 |

| Metacognitive awareness | 8 | I understand my intellectual strengths and weaknesses | 0.832 | 4.23 | 0.936 |

| Structure of knowledge | 5 | Lecturers should focus on facts instead of theories | 0.655 | 4.21 | 0.723 |

| Acquisition of knowledge | 5 | If you don’t learn something quickly, you won’t ever learn it | 0.807 | 4.95 | 0.754 |

| Positive epistemic emotion | 3 | When I am learning I often feel curious | 0.672 | 4.19 | 0.733 |

| Negative epistemic emotion | 4 | When I am learning I often feel frustrated | 0.740 | 3.60 | 0.881 |

| Proactive coping | 5 | I am a take charge kind of person | 0.808 | 4.00 | 0.812 |

| Reflective coping | 5 | I address a problem from various angles until I find the appropriate action | 0.748 | 4.31 | 0.747 |

| Feelings of shame | 3 | When I’m not doing well in learning I feel embarrassed | 0.902 | 4.29 | 1.184 |

| Performance avoidance | 3 | I avoid attempting to do something when I feel uncertain | 0.908 | 4.16 | 1.19 |

| Factor 1 Agentic Beliefs | Factor 2 Affective Beliefs | Factor 3 Epistemic Beliefs | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metacognitive awareness | 0.825 | ||

| Reflective coping | 0.799 | ||

| Proactive coping | 0.798 | ||

| Self-efficacy | 0.621 | −0.460 | |

| Feelings of shame | 0.837 | ||

| Performance avoidance | 0.800 | ||

| Inhibitory anxiety | 0.776 | ||

| Negative epistemic emotions | 0.614 | ||

| Prospective anxiety | 0.405 | 0.515 | |

| Structure of knowledge | 0.820 | ||

| Need for cognition | 0.421 | 0.624 | |

| Acquisition of knowledge | 0.565 | ||

| Positive epistemic emotions | 0.438 | 0.533 |

| Cluster 1 40.2% (n = 278) | Cluster 2 30.8% (n = 213) | Cluster 3 29% (n = 201) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 Agentic | 0.24 | −0.18 | −0.14 |

| Factor 2 Affective | 0.17 | −1.02 | 0.84 |

| Factor 3 Epistemic | 0.84 | −0.41 | −0.72 |

| Scale | Items | Example Item | Cronbach’s α (n = 175) | Mean ECT (n = 66) | s.d. | Mean Experienced Teachers (n = 91) | s.d. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identification | 5 | I can confidently identify students who are experiencing poor mental health. | 0.896 | 4.31 | 0.933 | 4.54 | 0.962 |

| Conversation | 5 | I am confident in my ability to initiate a conversation with a student about their mental health. | 0.926 | 4.44 | 1.044 | 4.71 | 1.081 |

| Referral | 5 | I am confident that I can refer students to the relevant internal supports for their mental health | 0.908 | 4.63 | 1.223 | 4.79 | 1.085 |

| Ongoing support | 5 | I am confident that I can provide appropriate ongoing support in my classroom to students who are experiencing mental health issues | 0.880 | 4.23 | 1.032 | 4.34 | 1.088 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Spray, E.; Smith, A.; Shaw, E.; Burke, R. Early Career Teacher Preparedness to Respond to Student Mental Health. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1505. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111505

Spray E, Smith A, Shaw E, Burke R. Early Career Teacher Preparedness to Respond to Student Mental Health. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1505. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111505

Chicago/Turabian StyleSpray, Erika, Abbie Smith, Emma Shaw, and Rachel Burke. 2025. "Early Career Teacher Preparedness to Respond to Student Mental Health" Education Sciences 15, no. 11: 1505. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111505

APA StyleSpray, E., Smith, A., Shaw, E., & Burke, R. (2025). Early Career Teacher Preparedness to Respond to Student Mental Health. Education Sciences, 15(11), 1505. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111505