Abstract

In this paper, we discuss the development of students’ systems thinking about the rock cycle as they interact with an instructional module that includes three interactive simulations and accompanying questioning. We present the reasoning of six students from a whole-class design experiment in a sixth-grade classroom to describe how students’ systems thinking may be constructed and reorganized through activity with our design. Our findings highlight a framework of students’ systems thinking about the rock cycle that builds and expands prior work to specific sub-components. We also discuss an emerging framework for supporting students’ systems thinking through careful design of simulation and questioning orchestrations. These two frameworks can be used to create other instructional modules that have the potential to develop students’ systems thinking in the context of earth science.

1. Introduction

Systems thinking describes the process of reasoning about simple and complex systems. A system is an “entity that maintains its existence and functions as a whole through the interaction of its parts” (O’Connor & McDermott, 1997, p. 2). For example, a plant is made up of many parts (roots, stem, leaves, flowers, fruit, seeds, etc.) that function together (e.g., the stem transports water and nutrients that the roots absorb from the ground to the leaves for photosynthesis) to form a living organism. This characteristic of a system distinguishes it from other collections of elements that do not work together to form a functioning whole, such as items in your garbage that you have thrown away. In other words, in systems “the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.” Accordingly, O’Connor and McDermott (1997) define systems thinking as looking “at the whole, and the parts, and the connections between the parts, studying the whole in order to understand the parts” (p. 2).

Systems thinking has been used to study human-made systems such as economics, engineering, and businesses, but is also prominent in the study of natural systems. This is particularly seen in the emergence of an Earth Systems Science perspective on the research and teaching of interrelated natural systems, such the water cycle (Ben-Zvi Assaraf & Orion, 2010), the rock cycle (Kali et al., 2003), and the carbon cycle (Clark et al., 2009). The study of the interconnected Earth Systems has been argued to be an approach for aiding students in developing a conceptual understanding of complex systems phenomena in science education (Jacobson & Wilensky, 2006) and abilities to navigate the challenges of environmental and social problems (Ben-Zvi Assaraf & Orion, 2010; Mayer, 1995). Despite its significance, many researchers (e.g., Bielik et al., 2023; Budak & Ceyhan, 2023; Jacobson & Wilensky, 2006) argue that the study of how students learn about complex systems remains relatively limited and call for more research on this area. For instance, Bielik et al. (2023) state that most of the existing studies focus on college students and that this research needs to be expanded to other populations. In pre-college education, attention to complex systems started emerging only recently within science education research such as the study by Gilissen et al. (2020) on 15–16-year-old students’ systems thinking in biology. Despite this increase in focus on systems thinking, Budak and Ceyhan (2023) argue that most studies focus on science education in general, biology education, or environmental education, with only a few studies conducted in earth science mainly before 2015 such as the study of Ben-Zvi Assaraf and Orion (2010) on water cycle and the study by Kali et al. (2003) on rock cycle. In their review of the literature on systems thinking studies, Budak and Ceyhan call for more research in understanding the use of systems thinking in science education, especially its characteristics, skills, and abilities.

The study described in this paper aims to address this gap by examining middle school students’ systems thinking in the earth science topic of the rock cycle. In Section 2, we begin by presenting a thorough review of the literature on systems thinking and the teaching and learning of the rock cycle. Then we discuss our research questions, which focused on examining the (a) the forms of systems thinking about the rock cycle that middle school students exhibited as they engage with our design, and (b) the elements of our design that provided opportunities for students’ systems thinking about the rock cycle. Our prior research focusing on students’ understanding of various Earth and Environmental phenomena (e.g., Panorkou & Germia, 2021) have shown the power of design for supporting and structuring students’ experiences and conceptualizations of scientific phenomena. Therefore, in Section 3, we describe how we build on literature on the teaching and learning of rock cycle as well as systems thinking to design learning environments in which students can experience and conceptualize the rock cycle as a dynamic system. We also describe the methods we used to answer our research questions. A whole-class design experiment was conducted in a sixth-grade classroom, where students engaged with three digital simulations as they explored the rock cycle. Our findings in Section 4 provide detailed accounts of the forms of students’ systems thinking of each component and the type of activity that might have supported those. Subsequently, Section 5 discusses the two frameworks emerging from our analysis: a framework that describes specific components and sub-components of systems thinking about the rock cycle that students may exhibit and a design framework for supporting students’ systems thinking of the rock cycle that includes suggestions for simulation and questioning orchestrations for each of the three components of systems thinking. We conclude in Section 6 by outlining the limitations of the study and discussing how the two emerging frameworks contribute to research on recognizing, interpreting, and supporting students’ systems thinking about the rock cycle.

2. Review of Literature

In this section, we present a review of the literature on systems thinking and the rock cycle. In the first sub-section, we review the prior research on systems thinking and explore how the teaching and learning of the rock cycle progressed over the years, outlining difficulties that students typically experience. The second sub-section describes the development of the theoretical framework of this study through the exploration of existing frameworks for studying students’ systems thinking in the context of Earth systems. The third sub-section presents how our research questions emerged from this literature review.

2.1. Systems Thinking and the Teaching and Learning of the Rock Cycle

The Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS; National Research Council, 2013) identify Systems and Systems Models as a crosscutting concept that spans K-12 science education. In middle school, students are expected to use models to represent systems and their interactions (including the flow of matter through processes of the system). The rock cycle is one of the Earth systems that students are formally introduced to in middle school. In particular, students are expected to model and describe the cycling of Earth’s materials and the physical and chemical changes that describe the rock cycle with an emphasis on “on the processes of melting, crystallization, weathering, deformation, and sedimentation, which act together to form minerals and rocks through the cycling of Earth’s materials” (MS-ESS2-1). Typically, three types of solid rock are considered to be part of the rock cycle: Metamorphic Rock, Igneous Rock, and Sedimentary rock. In addition, the molten rock (magma/lava) and sediment are considered to be materials that rocks are constructed from. These rock and non-rock materials undergo physical and chemical changes through a series of processes that typically include: heat and pressure, melting, cooling (crystallizing), weathering and erosion, and compacting and cementing. Table 1 presents these processes and materials in a way that shows the material formed as a result of a specific process.

Table 1.

Processes and Materials of the Rock Cycle.

Historically, the teaching and learning of the rock cycle has been a challenge due to its complexity (e.g., Vasconcelos et al., 2019). As a result, students form a variety of alternative conceptions about the phenomenon (Guffey & Slater, 2020). Research shows that most students classify rocks based on their physical properties such as color (Ault, 1982), shape (Ford, 2003), or weight (Happs, 1982). They also believe that rocks are formed due to catastrophic events (Kusnick, 2002) or only due to specific processes, such as believing that metamorphic and igneous rocks are formed through weather conditions (Stofflett, 1993) or that minerals are always formed through pressure (Oversby, 1996).

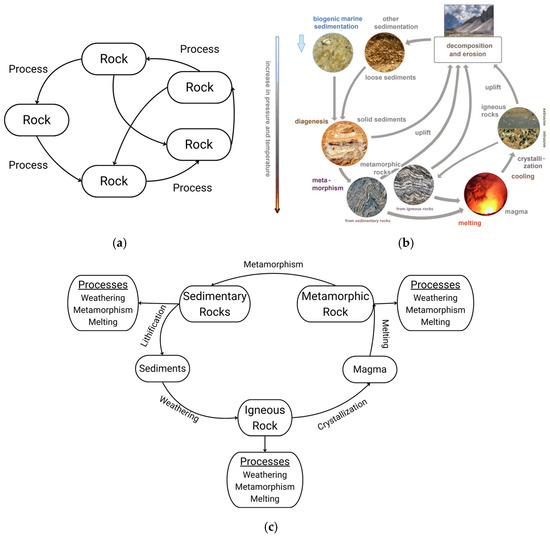

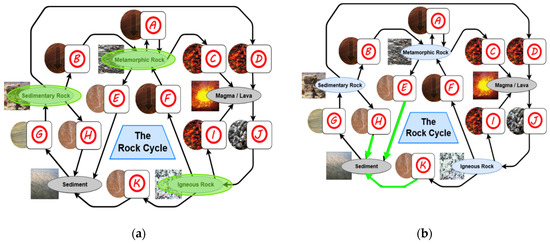

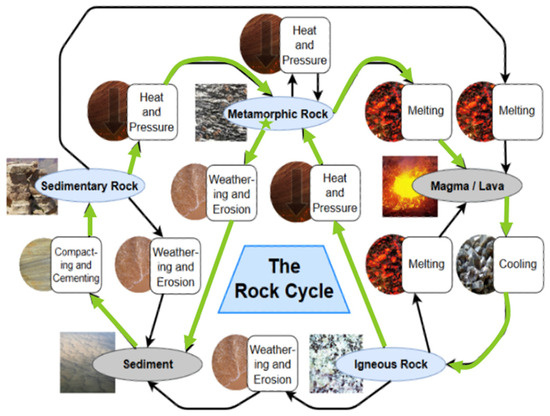

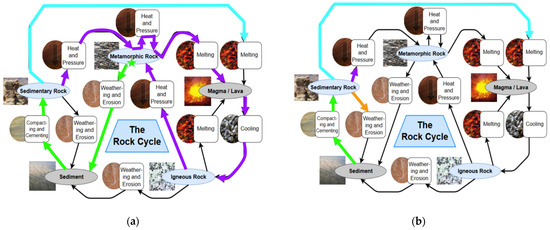

Because of these difficulties, over the years science educators have constructed models of the rock cycle in the form of diagrams to support students’ learning. Modern diagrams often still arrange these materials and processes similarly to the diagrams of the 1970s and 1980s without “significant variations in its essence” (Peloggia, 2018, p. 3). Peloggia identified two types of rock cycle diagrams; Type 1 diagrams consist of boxes and arrows showing the relationship between materials and processes that was dominant in both older texts (see Figure 1a for diagram similar to one used by Singh & Bushee, 1977) and in recent publications with graphic features (Figure 1b). Some of these diagrams illustrate multiple pathways through the cycle, allowing for sub-cycles to be identified. For instance, matter can flow through the sub-cycle of transformation from metamorphic rock to magma through melting, to igneous rock through cooling, and back to metamorphic rock through heat and pressure. Back in 1988, Eves and Davis reported that most textbooks treat rock cycle materials first and processes second. They also found that this separation of processes and materials leads to students failing to make connections about the relationships between the two. They proposed a modified diagram (see a similar diagram to the one used by Eves and Davis in Figure 1c) focusing on the materials and showing how the same processes can affect each of the types of rock. However, it is difficult to identify various sub-cycles in this new diagram the way Singh and Bushee’s does, as the possible processes are disconnected from the main cycle.

Figure 1.

Examples of Type 1 diagrams. (a) A diagram similar to one used in 1977 by Singh & Bushee. (b) Illustration by Sciencia58. Public Source and License: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cycle_of_rocks_2.png (accessed on 16 October 2025); (c) A rock cycle diagram similar to one by Eves and Davis (1988).

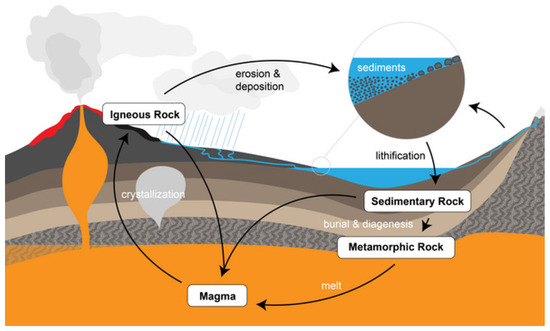

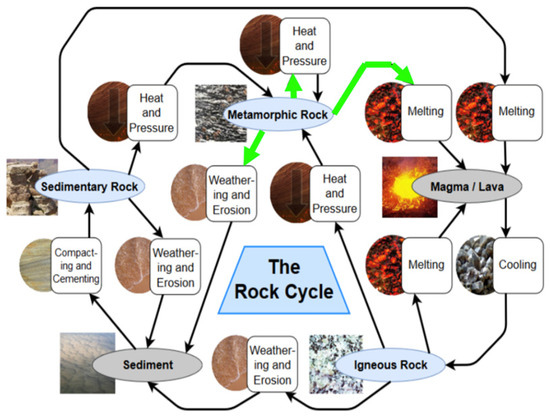

Type 2 diagrams are also used more recently and depict these concepts and arrows on top of physical locations as a context for the rock cycle (Figure 2). What is common among all these different types is that the rock cycle is presented to students in static diagrams within textbooks that students are often asked to memorize. Similarly to the diagram in Figure 1c, some of these rock cycle diagrams also show the system as a singular cycle, ignoring the multiple sub-cycle pathways that can exist for the flow of matter. As a result, students fail to view this phenomenon as a dynamic and cyclic system.

Figure 2.

Example of a Type 2 diagram. Rock Cycle Illustration by Carrie027. Public Source and License: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rock_Cycle_Illustration.png (accessed on 16 October 2025).

Kali et al. (2003) report on some alternative conceptions that students have that prevents them from seeing the rock cycle as a dynamic and cyclic system. To elaborate, students view each product of the rock cycle as an isolated material which cannot change or be transformed into any other rock. Kali and colleagues give the example of granite and sandstone that students believe that there is no chance that one formed the other. Another alternative conception that students have is that they view the rock cycle system as a collection of isolated pairs of product-process pieces without relating the pairs between them, failing to recognize the chain of processes and materials as well as the sub-cycles that the rock cycle entails. Others view the system as two separate types of processes, one occurring inside Earth and one on the surface, which are not connected. What is more, students often view the rock cycle as a one-way process, failing to conceptualize the dynamic and repeating nature of its sub-cycles.

What the literature continues to tell us is that there is a need to develop students’ systems thinking about the rock cycle and that the current approaches fail to support students in this regard. Consequently, it is necessary that we develop new approaches to support our students’ conceptualizations of the rock cycle as a dynamic cyclic system that includes a chain of processes and materials. The following section delves deeper into what systems thinking might entail in the context of the rock cycle and the characteristics of design that might support students’ systems thinking conceptualizations.

2.2. Studying the Rock Cycle from a Systems Thinking Lens

Building on the work of O’Connor and McDermott (1997) on systems thinking, Kali et al. (2003) defined three levels of understanding that systems thinking of the rock cycle entails: “(a) understanding the parts of a system, (b) understanding the connections among these parts, and (c) understanding the system as a whole” (p. 548). We interpret the first level as highlighting the identification of the processes and materials of the rock cycle including a distinction between rock and non-rock materials. The second level illustrates a focus on the relationships between the processes and the materials and the making of generalizations about how processes apply to rock or non-rock materials. For example, a student might reason that any rock undergoing weathering and erosion would transform into sediment. The third level describes the understanding of the rock cycle as a whole system of interconnected parts. For example, a student might reason about possible paths in the rock cycle: a metamorphic rock can melt into magma/lava, which can then cool to form igneous rock, and that igneous rock can later undergo heat and pressure to become metamorphic rock again.

In developing a theoretical framework for our study, we also considered more recent definitions of systems thinking in science education and compared them to Kali et al. (2003) in order to construct a more comprehensive framing that could capture the diversity in students’ conceptions. We first considered Ben-Zvi Assaraf and Orion’s (2005, 2010) work on systems thinking in the context of Earth Systems education, and particularly the water cycle, and their Systems Thinking Hierarchical (STH) model with eight characteristics. While most of their characteristics reflect the definition provided by Kali et al., Ben-Zvi Assaraf and Orion provide more information on what it means to understand the system as a whole (Kali et al.’s Component c). In particular, they added the ability to organize the system’s components and processes within a framework of relationships and the ability to understand the cyclic nature of systems. In the rock cycle context, the former emphasizes the conceptualization that matter flows through the rock cycle system through a chain of processes that change materials from one form to another while the latter highlights the conceptualization of the rock cycle as an endlessly repeating cycle that matter flows through. The literature in the previous section has shown both as difficulties that students face when they work with systems, therefore we added these two characteristics as sub-categories for understanding the system as a whole in our framework. Table 2 depicts our theoretical framework for studying students’ systems thinking by providing a description of each component from the rock cycle context.

Table 2.

Our systems thinking framework for the rock cycle adapted from prior research.

Prior studies also provided guidance on how we may design activities that might elicit and develop students’ systems thinking. To elaborate, Kali et al. (2003) distinguished between low and high systems thinking, where low systems thinking points to an identification of the parts of the system but not an understanding of the relations between them. In contrast, high systems thinking includes an understanding of the dynamics of the system that reflect the two more advanced components in Table 2. Kali et al. (2003) argued that only when students reason in high (dynamic) systems thinking are they developing “meaningful understanding of the rock cycle” (p. 563). To support students’ high systems thinking, they suggest that curricular activities include a gradual building of each of the system’s parts through an inquiry process that would progressively lead to a holistic conceptualization of the system. Consequently, in our design, we considered engaging students in a gradual exploration of the system by first focusing on its processes and materials, then shifting to relationships between them, and finally engaging them in activities that can support their conceptualization of the system as a whole.

In synthesizing the literature on students’ systems thinking in science education, Mambrey et al. (2020) noted that there is a consensus regarding the three most fundamental skills of systems thinking: (1) describing the organization of the system, (2) analyzing the behavior of the system, and (3) modeling the system. While the first two skills are included in our framework in Table 2, we found the idea of system modeling particularly interesting for our design. Mambrey et al. (2020) described system modeling as the ability to construct models of the system’s future states based on hypotheses. We considered that designing activities that prompt students to imagine hypothesized states of the system could elicit their understanding of the rock cycle as a chain of processes and materials and/or the rock cycle’s cyclic nature.

2.3. Research Questions

Every student constructs their knowledge through their own perceptual experience (von Glasersfeld, 1995), therefore the design of the learning experiences we provide to students for studying various scientific phenomena play a structuring factor on how students may think about those phenomena as systems. We consider the design of the learning experience to include both the teacher/researcher questioning and the artifacts that students interact with. Noss and Hoyles (1996) argue that by analyzing how students shift between different forms of thinking we can understand what students already know and how new forms of thinking are constructed and shaped by our designs. Shifting between different forms of systems thinking involves reorganizing (Piaget, 1977/2001), in the sense of making humble inferences about their reflections and projections of their systems thinking of the phenomenon of the rock cycle to a higher conceptual level where these initial forms become part of a more coherent whole. Considering the above, our study explored the following research questions:

- What forms of systems thinking about the rock cycle do middle school students exhibit as they engage with our design?

- What elements of our design provide opportunities for students’ construction and reorganization of systems thinking about the rock cycle?

3. Methods

In this paper, we report on the findings of the first iteration of a whole-class design experiment (DE) (Cobb et al., 2003) aiming to engineer students’ systems thinking about the rock cycle and study students’ forms of systems thinking within the activity in which they were elicited. The purpose of a DE is to build theories about student learning while examining the strategies that supported these forms of learning. Each experiment was guided by our conjectures as described below, and these conjectures were open for revision and refinement as the experiment unfolded.

3.1. Research Context, Participants, and Data Collection

The DE was conducted in 2019 in a sixth-grade classroom from a school district in northeastern U.S.A. with minority enrollment of 95%. The district has about 69% Hispanic and 19% African Americans students, and about 48% of students were classified as economically disadvantaged. Prior to the DE, we made some conjectures about students’ prior knowledge of the rock cycle and any scientific experiences of system thinking. Based on the NGSS (National Research Council, 2013), we expected that these students had some formal learning on the rock cycle through the study of patterns in rock formations and fossils in rock layers in fourth grade (4-ESS1-1). We expected that many of their rock cycle conceptions might reflect some of the common alternative conceptions presented in the literature (see The Teaching and Learning of the Rock Cycle). Students were also expected to have some prior knowledge on some of the processes, such as heating and cooling from their learning of matter and its interactions in fifth grade (5-PS1-2). In terms of systems thinking, students have studied systems before, specifically the water cycle (e.g., 5-ESS2-2) and other ecosystems (e.g., 2-LS2-1, 3-LS2-1).

In this paper, we focus on the reasoning of six students from the whole-class design experiment. Prior to the design experiment, the teacher was given a detailed instruction plan, explored the activities themselves, and discussed the lessons with the researchers. While the teacher took responsibility for the class instruction, three researchers sat with three pairs of students, respectively, aiming to create “a small-scale version of a learning ecology so that it can be studied in depth and detail” (Cobb et al., 2003, p. 9). These students were selected by the teacher with the criterion of being more verbally expressive, so they would be able to externalize and elaborate on their thinking. The teacher also grouped these students in pairs with whom they felt comfortable (usually with classmates that they have worked before). We hoped that the discussion with the researchers would provide a wider window into the students’ reasoning, allowing us to characterize their construction and reorganizations of their forms of systems thinking in more depth.

The activities presented in this paper were conducted over four sessions (45–60 min in length). The on-screen activity of all six students was video-recorded and multimodal transcriptions were produced that include descriptions of the students’ on-screen and gestural activity. These included both “verbal and non-verbal acts for every participant” (Chanier & Lamy, 2017), such as words, visual images of on-screen behavior, and kinesthetic actions (e.g., mouse movement, gestures). It is worth mentioning here that although the students were grouped in pairs, they worked most of the time independently probably due to the nature of the computer tasks. As a result, we analyzed each student independently. In this paper, we present the analysis of these six students (Michael, Laura, Noelle, James, Daniel, and Arianna) working with our Rock Cycle simulations.

3.2. Design and Conjectures

While most natural phenomena, like the rock cycle, are complex systems with multiple variables, we opted to design simplified models of the rock cycle using digital environments that could make systems learning more accessible to middle school students. We chose to design computer simulations because of their premise to represent simplified models of complex scientific phenomena (Perkins et al., 2006). Simulations show the dynamic nature of systems by going beyond static images of cause/effect relationships (Evagorou et al., 2009). Prior research illustrated the power of digital environments for developing students’ systems thinking about the rock cycle by providing experiences that illustrate the dynamic behavior and cyclic nature of the rock cycle (Kali, 2003).

The simulations also allow for multiple trials and immediate feedback, supporting an inquiry environment (Meadows & Caniglia, 2019) where students can make conjectures, test them out, and revise their thinking based on the feedback provided by the simulation. We designed three computer simulations with each having specific useful pedagogical features (Weintrop et al., 2016), namely Cooking Rocks, Bob’s Life, and George’s Life. We, the STEM education researchers, worked with Earth and Environmental scientists and Computer Scientists to negotiate these features and maintain the integrity of the model while also creating an accessible data set for middle school students to investigate in the simulation.

Each simulation offered specific affordances and constraints for exploration and presented a different perspective of the rock cycle phenomenon. We conjectured that this orchestration of designing and organizing the three different simulations could support a synergy (Mariotti & Montone, 2020) between these artifacts and would prompt students to create relationships between the forms of systems thinking emerging from their use. This which could result in “deepening and weaving the semiotic web” (p. 113) of their systems thinking.

We supplemented the simulations with targeted questioning that prompted students to explain the simulation behavior based on their actions, noticings, and wonderings. We then integrated these simulations into a series of lessons as part of an instructional module on Rock Cycle. While the Rock Cycle module also included other supportive activities, in this paper we briefly describe those and focus mainly only on students’ activity with the three simulations because it was during that simulation activity that students exhibited systems thinking. In the following paragraphs, we describe each simulation in more detail, present the type of questioning that accompanied them, and discuss our initial conjectures that led to those designs.

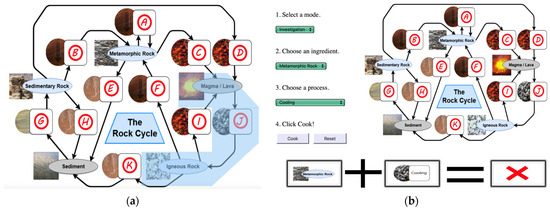

3.2.1. Simulation 1: Cooking Rocks

Prior to introducing any simulations, students were introduced to the essential question “What is the Earth made of?” that led them to express their prior knowledge on the composition of the Earth. Then, they engaged in a Globe Toss activity https://www.scseagrant.org/wp-content/uploads/globe-toss.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2025) where they tossed a ball around and recorded whether their hands touched water or land when they caught it. The goal of this activity was for students to begin thinking about the composition of the Earth and engage in a discussion around the affordances and limitations of models, such as the globe. Next, there was a whole-class discussion led by the teacher during which the Earth’s layers were introduced and the types of rocks and materials were mentioned. The first simulation was introduced after this discussion.

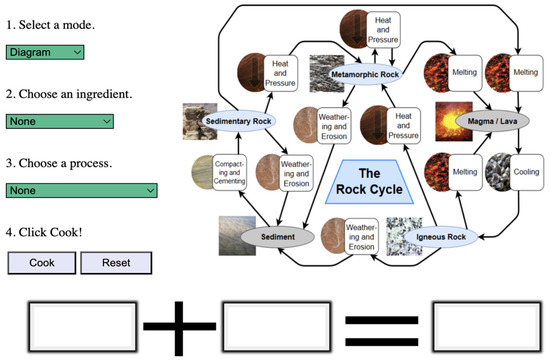

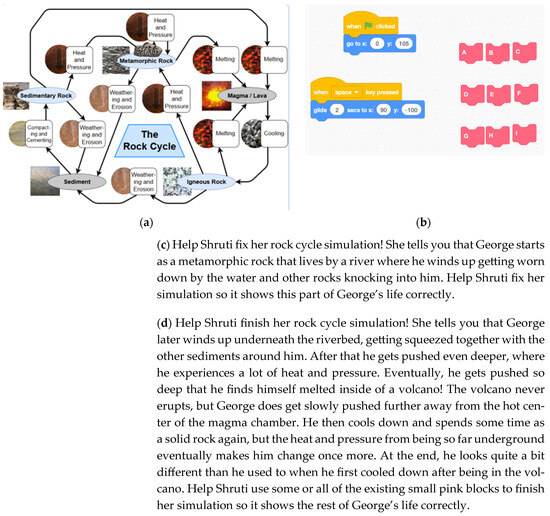

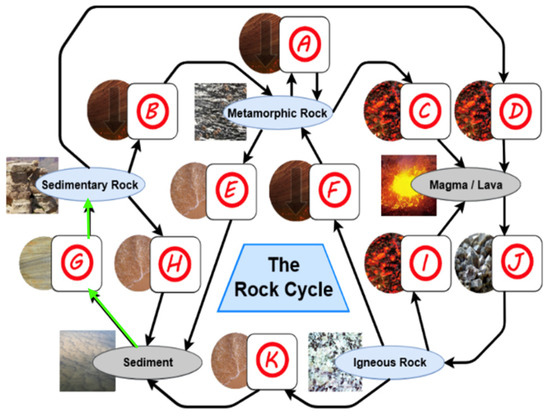

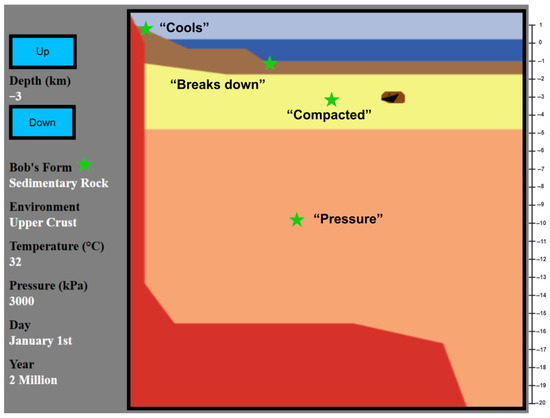

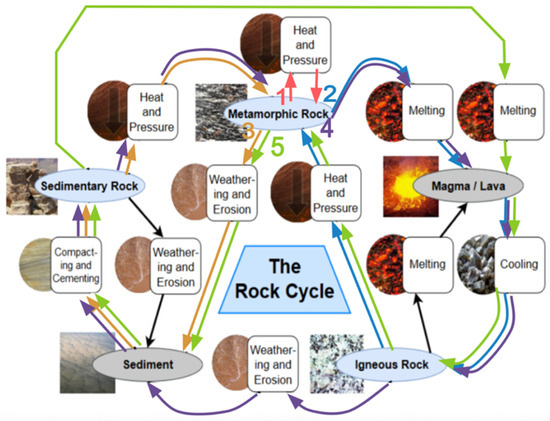

The Cooking Rocks simulation (https://acmes.online/htmls/cookingrocks/interface.html, accessed on 16 October 2025) was developed around a new rock cycle diagram with visual aids that distinguishes between process and materials and highlights the interconnections between them (Figure 3). The diagram uses a sediment image from Michael C. Rygel’s “Ripples” photo and other public domain images from Wikipedia (October 2018). The simulation presents a cyclical perspective of the rock cycle similar to Singh and Bushee’s (1977) diagram that shows multiple pathways through the sub-cycles of the system, but with more emphasis on how the processes are grouped together. For instance, all three of the weathering and erosion process boxes are grouped near the sediment oval to support students in noticing that the weathering and erosion process transforms any rock into sediment. The color of the ovals for the materials distinguishes between rocks (blue ovals) and other materials (gray ovals). Similarly to other diagrams (Eves & Davis, 1988; Singh & Bushee, 1977), we focus mainly on the transformations of the three types of rocks, therefore we do not include melting or cooling of other non-rock materials other than magma/lava.

Figure 3.

Cooking Rocks simulation in Diagram mode.

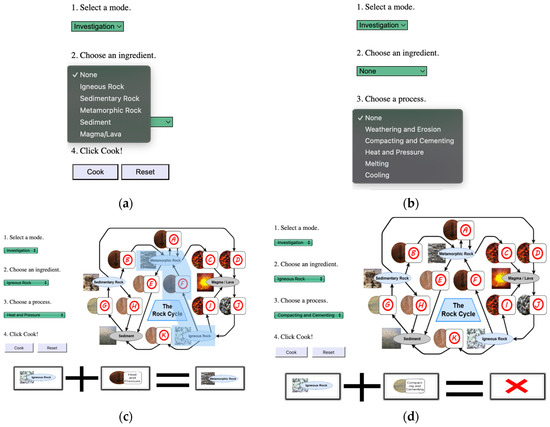

The simulation is based on the Earth analogy as a rock cooking machine that allows students to select a material (an “ingredient” in the simulation) and a process (Figure 4a,b) to create a recipe at the bottom of the screen. By clicking on the “Cook” button, students can receive feedback of whether their recipe was valid or not. The simulation has two modes: (a) the Diagram mode (Figure 3) and (b) the Investigation mode (Figure 4c), where the latter shows the same diagram but hides the name of the processes using letters. A valid recipe result is illustrated both in the recipe equation at the bottom of the screen and by the corresponding path being shaded in blue like in Figure 4c. An invalid recipe is illustrated by a red X in the result box in the equation like in Figure 4d. Our conjecture was that students will experiment with different recipes and reason about the different materials and processes and their relationships (Table 2, Components 1 & 2). Additionally, we conjectured that the cyclic nature of the diagram would support students to begin conceptualizing the cyclic nature of the rock cycle.

Figure 4.

Cooking Rocks in Investigation Mode. (a) Ingredient (material) list, (b) Process options, (c) Valid Recipe, and (d) Invalid Recipe.

We first allowed students some free time to explore the simulation and state what they notice and wonder. We then followed with specific questions that prompted them to identify variables in the simulation (e.g., What do you control in this simulation?), and questions that could lead them to classifying materials as rocks and non-rocks (e.g., Which ingredients aren’t considered to be types of rocks?). After identifying the materials and processes, we proceeded into questions focusing on an investigation of each of the processes, such as “What process turns igneous rock/metamorphic rock/sedimentary rock into sediment?” or each of the materials, such as “What materials can undergo compacting and cementing?”. We also prompted them to notice patterns and generalize (e.g., “Sediment is formed when any type of rock….”, “Does it work for all materials? Why/Why not?”).

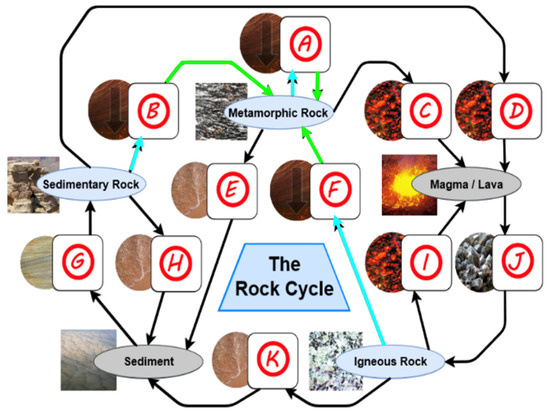

3.2.2. Simulation 2: Bob’s Life

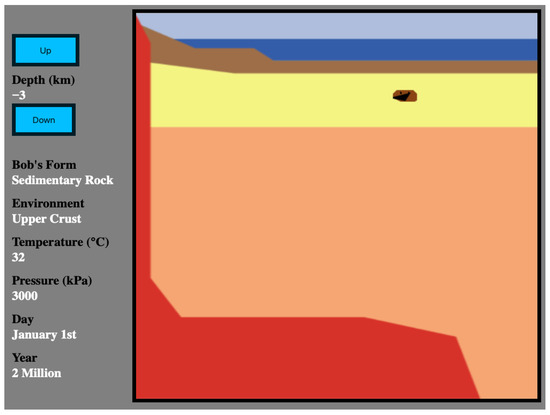

After exploring the Cooking Rocks simulation, students delved deeper into examining a hypothetical path of one rock moving around the rock cycle. The aim of this activity was to engage students in hypothetical systems modeling (Mambrey et al., 2020). The Bob’s Life simulation (https://acmes.online/htmls/bobslife/bobslife.html, accessed on 16 October 2025; Figure 5) presents students with a rock, named Bob, and a cross-sectional view of its environment on a volcanic Canary Island. Students can click the Up and Down buttons to change Bob’s depth and observe changes in multiple variables such as its form, its environment, its temperature (in °C), his pressure (in kPa), and the travel time. We conjectured that the Bob’s Life simulation can prompt students to explore the flow of energy in a sub-cycle of the rock cycle, highlighting the role of temperature and pressure, and that it would support them to reason about the rock cycle as a dynamic and cyclic system (Table 2, Component #3).

Figure 5.

Bob’s Life simulation.

Similarly to Cooking Rocks, we first allowed students to freely explore the simulation and state their noticings and wonderings (e.g., What have you noticed? What happens in this simulation? Can you describe to me what’s going on with Bob?). We then followed with specific questions asking them to identify the variables (e.g., What do you control in this simulation? What changes in the simulation?) and relationships between variables (e.g., What relationships do you notice between variables in the simulation?). Although not the focus of this paper, this simulation was also used for developing students’ covariational reasoning about depth, temperature, and pressure, which we describe in another paper (Panorkou & Provost, 2025).

3.2.3. Simulation 3: George’s Life

After students explored the Cooking Rocks simulation, they were introduced to the “broken” George’s Life simulation that they had to fix (https://acmes.online/simulation_link_details/13, accessed on 16 October 2025). This was an effort to introduce students to how simulations work through algorithms and engage them in computational thinking (Weintrop et al., 2016) through the process of debugging (Panorkou et al., 2024). At the same, we conjectured that asking them to fix a broken cycle of one rock would support them in reasoning about the rock cycle as a chain of processes and products (Table 2, Component #3) by engaging in systems modeling (Mambrey et al., 2020) similar to the Bob’s Life activity. The George’s Life simulation (Figure 6a) uses the same rock cycle diagram as the one in Cooking Rocks. At the beginning of the activity, students are asked to read about George’s Life story, in which George first needs to move from a metamorphic rock to sediment (Figure 6c). The story then continues to describe two connected sub-cycles (Figure 6d). The simulation is designed on Scratch programming, where students are asked to change the code in the simulation to fix George’s path, which initially has George move incorrectly from metamorphic rock through heat and pressure to igneous rock. We designed the code using lettered blocks each focusing on a specific process (Figure 6b). Students had to drag and drop those blocks in order so that George moves correctly around the cycle. Prior to this lesson, students had a lesson on algorithms and completed a Scratch tutorial. While we describe students’ development of debugging knowledge in another paper (Panorkou et al., 2024), here we focus on students’ systems thinking.

Figure 6.

(a) The George’s Life broken simulation, (b) the block code that students had to order George’s movement, and (c,d) the two parts of George’s Life story.

Similarly to the previous two simulations, we allowed time for students to explore the simulation and express what they notice and wonder. Then we asked questions prompting them to compare the story of George’s Life to the buggy behavior of the simulation (e.g., What should the simulation do to show George’s Life? What does George actually do?), and try to fix it (e.g., Fix this block so that George moves to the right place.).

3.3. Data Analysis

We draw on the retrospective analysis which occurred at the end of the DE aiming to capture the reflexive relation between students’ system thinking and the nature of design that supported those forms of systems thinking. In particular, our analysis is guided by orienting questions, such as “What forms of systems thinking about the rock cycle do the students exhibit?”, “What is the nature of students’ systems thinking in each simulation interaction?”, and “How did the simulations, the sequence of simulations, and forms of questioning afford students’ systems thinking?”

Three stages of retrospective analysis were conducted with the DE data. First, we analyzed the data chronologically to identify episodes of students’ reasoning that illustrated the components of systems thinking as described in Table 2. For example, Laura’s description that she can control “the processes and the ingredients to make a rock or sediment or magma” in the Cooking Rocks simulation was categorized as illustrating an identification of the parts of the system (systems thinking Component #1) and it was included in the pool of episodes for analysis. Similarly, while exploring the heat and pressure process in the same simulation, Arianna stated that when “most rocks” go under heat and pressure they become a metamorphic rock and this was also included as depicting evidence of systems thinking Component #2. To ensure triangulation, two members of the research team initially identified these excerpts independently and then negotiated boundary cases. A third member of the research team then re-analyzed the data set and discussed any differences with the research team until reaching agreement.

After identifying all the relevant episodes, in the second stage of analysis, we used thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) to examine patterns in the ways that students’ reasoning reflected particular components of systems thinking and distinguished those forms of reasoning based on similarities and differences. For example, we interpreted Ariana’s relationship above as most rocks + heat & pressure → metamorphic rock. In contrast, Michael reasoned for the same process as “When a rock gets heated up and experiences pressure, it turns in, it turns into metamorphic rock.” When asked about “any type of rock” he specifically listed “only igneous, sedimentary, and metamorphic,” illustrating a different relationship as any rock + heat & pressure → metamorphic rock. Similarly to Michael, James reasoned that “any rock you add heat and pressure to it will turn into a metamorphic rock” and was placed in the same category as Michael’s. Through multiple rounds of discussions between the three researchers, thematic categories (particular, partial, and holistic) were collectively established to capture the above relationships.

In the third stage of analysis, we identified the qualitatively different forms of students’ systems thinking across all students and examined the progression of their thinking and reorganizations in each simulation activity. The outcome of this analysis was a set of “succinct yet empirically grounded chronologies” (Cobb et al., 2001, p. 128) of students’ systems thinking and the nature of design that fostered those particular forms of systems thinking. The following section presents the outcome of this last stage of analysis with the six students.

4. Findings

During their interactions with the Cooking Rocks simulation and our questioning, students identified the parts of the system (Component 1) and the relationships between the materials and the processes (Component 2). As they interacted with the Bob’s Life and George’s Life simulations, the students used what they had learned about Components 1 and 2 to reason about the system as a whole (Component 3) in different hypothetical situations.

4.1. Component 1—Identifying the Parts of the System

As mentioned earlier, students were given a few minutes to freely explore the Cooking Rocks simulation and then were asked questions about what they notice and what they can control in the simulation. These questions prompted the students to articulate the variables they were working with, and all students identified the materials and processes of the system. For instance, James stated that he can control “which rocks and which process it will go through” and that the ingredient list showed “types of rocks.” Similarly, when asked what he can use to make rocks, Daniel used the simulation to point out the drop-down list of ingredients and the processes. Another student, Arianna, listed all five ingredients (“Igneous rock, sedimentary rock, metamorphic rock, sediment, magma/lava”) and mentioned specific processes, such as heat and pressure and compacting. In their responses, four students (Laura, Michael, Noelle, and James) also distinguished between rocks and non-rocks. For example, Laura described that she could control “the processes and the ingredients to make a rock or sediment or magma” showing a distinction between rocks and other materials. When asked how she would explain the simulation to someone else, Laura provided a detailed description:

So, the simulation, you have to choose an ingredient, you have to choose out of igneous rock, sedimentary rock, metamorphic rock, sediment and magma/lava. And you have to choose a process, you have to choose weathering and erosion, compacting and cementing, heat and pressure, melting and cooling. And then when you choose either one of those and you press Select and you Cook it, it gives you a process. It either, if you, if your process makes sense it gives you like a result, if it doesn’t it puts an X through it. And if it’s a process, it highlights it in this diagram and the diagrams are labeled with big red letters to show sort of like paths through the rock cycle.

Like Laura, other students identified how they could use parts of the system that they had identified in the simulation. As they used the simulation, they noticed relationships and patterns in the combinations of materials and processes. For instance, James summarized that he could, “see what would happen to different types of rocks when it goes through different types of processes.” Similarly, Noelle noted that “each rock has a different process to become other things” and “that some types of processes only work for a specific type of rock and don’t work for others. So they don’t work for all the rocks, they only work for some of them.” These statements show that the students were beginning to think beyond the individual materials and processes to how they work together.

Students also began giving explanations about why some recipes were valid or not and these provided further insights into their conceptualizations of materials in terms of their location and physical properties. For instance, Arianna said that she usually sees sediment “on land, like at beaches.” In describing melting with an input of magma/lava, she reasoned about the difference in location for lava and magma, “Obviously it doesn’t do anything. […] Magma is just like the cool version, the underground version actually of lava, and lava is above ground but they’re both already melted.” In exploring the same process, students also discussed the materials’ temperature. For example, James explained that magma/lava “is already heated”, Noelle stated that “magma already has heat in it”, and Michael elaborated that “because magma is already heat[sic] and if you just add to it just makes more like hotter magma and lava.” In their explanations, we observed that they often used temperature as both a physical property of a material and a process that might transform that material. For instance, in trying to melt an input of metamorphic rock, Noelle connected the increase in heat to the transformation of a rock to hot magma, stating “Because you’re putting heat on the rock so then it will turn into magma because magma is really hot.” Likewise, while experimenting with recipes and cooling, students provided explanations of why cooling was the only process that worked with magma/lava by connecting it to temperature. James, for example, stated that this happens “because magma and lava is hot.” Likewise, Michael explained, “You can’t cool any type of rock except for magma. […] ‘Cause if you cool any type of rock it won’t really make an effect on anything except for the temperature.”

Additionally, students distinguished between solid and non-solid materials. For instance, Michael stated that “magma and lava is a liquid kind of” while James argued that sediment is “not a full rock, it’s like, it’s not like solid.” Noelle also reasoned similarly in explaining why magma did not work with weathering and erosion, stating “Because magma is kind of like a liquid. It’s not a solid. […] It’s not a solid rock and all the other ones are solid.” She later attributed sediment and magma as “not working” with certain processes while cooking “cause they’re not like a rock.” Similarly, Daniel identified that magma/lava and cooling would “turn into igneous rock” arguing that, “you can’t really cool something that isn’t melted. When you cool something that is melted, it forms into a rock.”

Students also discussed the difference between sediment and rocks, with James stating that sediment “is not like a full rock” and Laura explaining that it is “tiny pieces of the rock.” It was evident in their explanations, that they began connecting specific processes with the form of specific output materials, such as the process of weathering and erosion breaks down the rocks into sediment which is a broken down material consisting of tiny pieces. To exemplify, Daniel explained that “weathering and erosion, it slowly breaks down the metamorphic rock for certain tiny pieces and you call those tiny pieces sediment.” As Noelle tried sediment with weathering & erosion, she stated that “when you weather and erode sediment it’s already sediment so it’s not going to turn into sediment so it’s already like broken down.”

Additionally, students began making connections between the form of input materials and specific processes, such as arguing that the process of compacting and cementing brought together the little pieces of sediment into a compacted and cemented rock. For example, when asked why Noelle thought compacting & cementing worked for sediment, she explained, “Because sediment it’s not together so when you compact cement, […] it will get together.” Noelle and James similarly explained that sediment worked with compacting & cementing because it was a material that had not been compacted & cemented (brought “together”) yet. Laura stated, “When you compact sediment and it’s like pressure when it’s compacting it over like millions of years it turns into sedimentary rock.” Daniel used the simulation to cook metamorphic rock and compacting & cementing he explained, “the metamorphic rock is kind of already compacted. […] The metamorphic rock is already compacted and it’s cemented already. When asked which rock was most interesting to him, Daniel drew upon his trials in the simulation and stated,

Sedimentary rock […] because it’s kind of cool that it’s formed out sometimes little tiny pieces that because they will come back together it’s just a little tiny piece. […] It has to be compact for sedimentary rock to form.

During students’ experimentations, their explanations illustrate that they identified that materials can be transformed and began connecting the materials’ transformations (input and output materials) with specific processes. The next section describes how students developed these connections between materials and processes into various forms of relationships.

4.2. Component 2—Identifying Relationships Among the Parts of the System

As students continued to explore the simulation and experiment with different recipes, they constructed relationships between the processes and materials they identified. Our analysis illustrated three different types of relationships for each process: particular, partial, and holistic. We characterize particular relationships as the relationships that depict the interconnectedness between a single input and a single process with a specific output, such as metamorphic rock + melting → magma & lava. We identify holistic relationships as the relationships that depict a web of connections between input(s), process(es), and output(s). For example, any rock + melting → magma & lava. Table 3 presents an overview of the six students’ constructions of holistic relationships for each rock cycle process. Gray shaded cells illustrate that the student showed evidence of constructing the relationship. White cells illustrate that we do not have enough evidence from that student to make a claim that they constructed the relationship at that time (Note: At times our evidence was limited by data collection factors such as unintelligible audio and blocked screens on the video recordings). Finally, we define partial relationships as the relationships that are missing input(s) or output(s) in their web of connections. For example, compacting & cementing → sedimentary rock.

Table 3.

Overview of Students’ Holistic Relationships for Each Process.

The following subsections delve deeper into each process by providing examples of how students’ constructed and reorganized particular, partial, and holistic relationships. We also highlight the diverse ways students engaged in exploration and how our questioning supported their constructions and reorganizations of relationships.

4.2.1. Melting

Table 4 presents the relationships that students explored and constructed about melting. Students who cooked the particular relationships with the simulation are represented with an S in the table. The students who verbally expressed the relationship are represented by shaded cells. As Table 1 shows, all students explored almost all five ingredients with the melting process and determined which ones produced valid recipes and which did not. In the following paragraphs, we provide examples to describe how students began with particular relationships and, through experimentation, were able to notice patterns and reorganize their thinking to more holistic relationships.

Table 4.

Statements made by Students about Melting Relationships.

For example, as James and Noelle were exploring the simulation they both cooked sedimentary + melting → magma/lava. When asked what happened, James described the particular relationship, “The sedimentary rock got melted so it turned into magma/lava.” Similarly, Noelle pointed to the recipe and stated, “when you melt it usually turns into magma.” James was then asked if he also noticed that when rocks melted they turned into magma/lava, and he said, “yes.” Then they were both prompted to use the simulation to explore different recipes to prove if any rock melting would create magma/lava. As she cooked the three rocks, Noelle stated, “Yeah this one [igneous] did and sedimentary did. And metamorphic.” In addition, James tried magma/lava, which provided an opportunity to ask the students why that material did not work. James stated, “Because it’s already melted”.

Later in the DE, Noelle was again asked what happened with melting and explained that melting “turns into magma. […] Because you’re putting heat on the rock so then it will turn into magma because magma is really hot.” She was then asked, “So if I put heat into any rock will it turn into magma?” Noelle replied, “I think, yes. I think except for the magma, because it’s already magma. And for the sediment. Maybe, I don’t know about the sediment. I know for sedimentary rocks, metamorphic and igneous, it will turn into magma.” She was then prompted to try the ones she was not sure about. Noelle tried magma/lava and sediment and explained “this[magma/lava] is already magma […] So it’s already heated. And sediment. It doesn’t work for sediment.” Finally, when asked why they did not work, Noelle stated, “‘Cause they’re not a rock.” As seen in this example, the researcher’s questions and prompts helped Noelle to validate her existing holistic relationship any rock + melting → magma/lava by excluding magma/lava and sediment as additional materials that did not work and providing explanations of why only rocks were included.

Similarly to Noelle and James, Laura and Daniel used the simulation to create various recipes to construct the same holistic relationship. However, in Arianna’s and Michael’s statements the rock vs. non-rock distinction was rather blurred. For instance, Arianna stated, “all the rocks, except magma and lava when you melt them they all become magma and lava.” Her statement illustrates the relationship any rock (except magma/lava) + melting → magma/lava, without distinguishing magma/lava from rocks. In a similar manner, when Michael was asked about what happens with melting, he stated and demonstrated using the simulation that “if you melt any type of rock, [cooked metamorphic + melting → magma] it always becomes magma and lava because magma and lava is…melted rock.” Then he cooked sediment + melting → X, stating, “oh wait, except for sediment.” While his statement illustrates the holistic relationship of any rock (except sediment) + melting → magma/lava, we do not have evidence of him distinguishing sediment from rocks. During the experiment the researchers did not notice this lack of distinction in their meanings, so no follow up questions were asked to help clarify their thinking.

4.2.2. Cooling

Table 5 illustrates which of the materials each student cooked in a recipe with cooling and the verbal statements that they made. Similarly to melting, the students experimented with the simulation and all six of them constructed the particular relationship magma/lava + cooling → igneous rock. Next, students considered both this relationship and the non-relationships they noticed to reorganize their thinking to more holistic relationships. We observed two distinct holistic relationships emerging in students’ thinking, which we describe below, highlighting the role our questioning might have played in their construction.

Table 5.

Statements made by Students about Cooling Relationships.

To begin with, one student (Arianna) was asked questions intended to help her examine one material with multiple processes (e.g., “[this material] has to undergo what process?”). Through these, she identified cooling as the only process that worked with magma/lava and eliminated other processes to construct the relationship magma/lava + only cooling → igneous rock. For example, after identifying the particular relationship magma/lava + cooling → igneous rock, she identified that “Magma and lava is not a rock. So it can’t weather or erode.” She was then asked what the only process that worked was and answered, “Cooling.” In contrast, three students (Michael, Laura, Daniel) identified magma/lava as the only material that worked with cooling and eliminated other materials to construct the relationship only magma/lava + cooling → igneous rock. For example, when asked what can be cooled, Laura identified that “you can cool magma and lava, you can’t cool sediments or metamorphic rock, sedimentary, igneous,” leaving magma/lava as the only ingredient which can be cooled. We noticed that two of those students (Laura and Daniel) were asked questions that were focused on the materials (e.g., “what material can be cooled?”) rather than the process, which might have led to the specific type of the holistic relationship.

Two students (James and Noelle) constructed both of these holistic relationships, with Noelle making a distinct transition from one to the other. For instance, after experimenting with the simulation, Noelle was asked what processes would work with magma/lava. She cooked magma/lava + heat & pressure → X and explained that it was “Cooling. […] ‘Cause if you put heat and pressure [pointed to equation she just tried on the simulation] it’s already heated, so if you put melting it’s already heated but cooling like it can cool to form something else.” When asked what this cooling produces, she replied with “igneous rock” while tracing the path on her computer screen with her finger (Figure 7a). She was then asked if cooling only works for magma/lava. Noelle cooked metamorphic with cooling, and explained “I think it only works for magma and lava because when I tried the other ones it just does that” pointing to the X in the simulation (Figure 7b). Noelle’s example demonstrates a transition from examining one material with multiple processes to considering multiple materials for one process after being asked questions focusing on both processes and the materials, respectively.

Figure 7.

Recreation of (a) Noelle’s path traced by her finger and (b) Noelle’s simulation usage.

4.2.3. Weathering and Erosion

Table 6 illustrates which of the materials each student cooked in a recipe with weathering and erosion and the verbal statements that they made. While experimenting with the simulation, four out of six students (Daniel, Michael, Noelle, and Laura) verbally constructed the holistic relationship any rock + weathering & erosion → sediment, one student (Arianna) constructed a single non-relationship, and one student (James) tested recipes but we do not have evidence of him expressing the relationships in words. We discuss the four students’ constructions and reorganizations below.

Table 6.

Statements made by Students about Weathering and Erosion Relationships.

All four students who constructed a holistic relationship were supported by probing questions that focused on input materials (e.g., “is it [that relationship] true for every rock?”, “for which [inputs] does it work?”, “What are those rocks that have to experience weathering and erosion”) and questions that focused on processes/outputs (e.g., “So when do we get sediment?”, “how do you make sediment?”, “Do you know how sediments form?”). To begin with, following her initial exploration, Laura was asked, “how is this going?”, and she replied, “I wanted to try [to] see, if any other process can turn into sediments, because so far it’s just been weathering and erosion.” She then stated,

I realized that every single time we selected ingredients and then choose a process and we cook it, it always, the answer is always weathering and erosion because you can’t compact it, and it will turn it to sediment. Nor is cooling or melting. And heat and pressure like turns it though [inaudible].

A few minutes later, Laura was asked if she noticed any patterns, to which she responded, “I noticed that all of the rocks, if you choose weathering and erosion, they turn into sediment.” When asked about “all of them” she stated “Igneous, sedimentary, and metamorphic. If you choose all of them.” She was then asked about the other materials and she responded by explaining that “sediment can’t really erode more” and that “magma and lava aren’t rocks, they’re material made to use rocks.” At the end of the cooking rocks lesson, she confidently stated that “if any type of rock weathers and erodes away it can turn into sediments.” Her explanation of both the process that produces sediment and materials that did and did not work led her to reorganize her thinking to the holistic relationship, any rock + weathering & erosion → sediment. Even though Noelle and Michael’s reorganizations were led by an exploration of materials first, and then an exploration of processes, they still constructed the holistic relationship any rock + weathering & erosion → sediment.

Daniel differed from the other students in that he verbally connected three relationships of weathering and erosion depicted in the diagram to his prior explorations with the different recipes. When he was asked how sediment was formed he pointed to the three rocks in the diagram (Figure 8a) stating “For every rock, sedimentary rock, metamorphic rock, igneous rock […] they all have to experience weathering and erosion to create sediment” and pointed to sediment. When later in the DE he was asked again about how sediment forms he pointed on the arrows as illustrated in Figure 8b emphasized that “It’s shown on the diagram. The arrows pointed.” Daniel’s reasoning illustrates that the combination of actively engaging with the recipes and also having the rock cycle diagram visible on screen may have supported students in making connections between their experimentations and the different possible paths that involve a specific process.

Figure 8.

Recreation of Daniel’s Pointing for Weathering and Erosion (a) inputs and (b) product.

4.2.4. Compacting and Cementing

Table 7 illustrates which of the materials each student cooked in a recipe with compacting and cementing and the verbal statements that they made. All six students identified that sediment was the only material that could be compacted and cemented and that it turns into sedimentary rock, constructing several different holistic relationships, including only sediment + compacting & cementing → sedimentary rock, only sediment + only compacting & cementing → sedimentary rock, and only (sediment + compacting & cementing → sedimentary rock). While engaging with the simulation, students systematically explored different recipes using two distinct approaches. We describe these approaches below and discuss how these might have been influenced by our questioning.

Table 7.

Statements made by Students about Compacting & Cementing Relationships.

The first approach was evident in four students’ work. James, Noelle, Michael, and Laura started exploring different input materials with compacting and cementing as a fixed process. All four students’ simulation explorations were supported by questions about the different input materials (e.g., “what do you compact and cement”, “which [material] do you think would work here [with compacting and cementing]?”) and constructed the holistic relationship only sediment + compacting & cementing → sedimentary rock.

Contrastingly, Daniel used a different approach by testing recipes of a single material with different processes. For example, he was asked, “Do you notice if you use metamorphic rock with a different process, can you try each one and then see how it goes?” As he tested processes with metamorphic rock, he noted that it did not work “because the metamorphic rock is kind of already compacted.” Recall that Daniel described sedimentary rock as his favorite rock that is created by bringing together and compacting little pieces of sediment (see Section 4.1). Later he was asked, “Did you master how sedimentary rock forms?” Daniel noted that “sedimentary rock forms from sediment that is compact. […] No, there isn’t any other way.” By considering which processes worked with specific input materials and which processes produced specific output materials, respectively, he was able to reorganize his thinking to the holistic relationship only (sediment + compacting & cementing → sedimentary rock).

Arianna’s case differed because she transitioned between these two approaches (varying the materials versus varying the process) and this transition supported a reorganization of a different holistic relationship. Similarly to the first group of students, Arianna started exploring multiple materials with compacting and cementing. When asked what she noticed about the simulation, Arianna stated, “For compacting and cementing, you can only do it with sediment. None of the others. […] because when I select different types of […] ingredients they don’t compact or cement.” As she spoke, she systematically used the simulation by trying different materials to show that only sediment can be compacted & cemented. Later, when she was asked questions prompting her to think about which processes work with a single material (e.g., “So what’s the only process that can go with it?”), she shifted to cooking all processes with sediment, and stated, “For sediment, there’s only one process, compacting and cementing, that works for it.” These statements illustrate partial relationships that she has constructed between the input material and the process, only Sediment + Compacting & Cementing, and Sediment + only Compacting & Cementing respectively. She then connected these to the output material, stating,

This demonstrated that Arianna constructed the relationship only sediment + only compacting & cementing → sedimentary rock. This also showed that she was able to link her relationship to the depiction in the diagram, as seen in Figure 9.I think the only process there is for sediment is like, cause the only process like I think of equals sedimentary, cause that’s what sedimentary rocks are made out of […] from the arrows it seems [the only process for sediment is] compaction and cementing [pointing to the arrows around G (compacting & cementing)].

Figure 9.

Recreation of Arianna’s Pointing of Outputs for Compacting & Cementing.

4.2.5. Heat and Pressure

Table 8 illustrates which of the materials each student cooked in a recipe with heat and pressure and the verbal statements that they made. We have evidence of five students (Arianna, Michael, Noelle, James, and Laura) verbally expressing relationships about heat and pressure. Three students (Noelle, James, and Michael) constructed the holistic relationship any rock + heat & pressure → metamorphic rock while two students (Laura and Arianna) only constructed particular and/or partial relationships.

Table 8.

Statements made by Students about Heat & Pressure Relationships.

To elaborate, James initially cooked just metamorphic rock with heat and pressure and noted that “metamorphic rock is going through heat & pressure and then it turns into metamorphic rock.” This illustrated the construction of a particular relationship metamorphic rock + heat & pressure → metamorphic rock. James then systematically tested the three rocks with heat and pressure. James was asked if he noticed anything interesting, to which he replied “any rock you add heat and pressure to, it turns into a metamorphic rock,” revealing a reorganization to the holistic relationship any rock + heat & pressure → metamorphic rock. He was then asked what materials did not work with heat & pressure. James tested both sediment and magma/lava with heat and pressure using the simulation, and confirmed “Sediment and magma.”

Three other students (Michael, Noelle, Laura) explored the simulation similarly by testing different materials with heat and pressure. They were also supported by questions focused on those materials (e.g., “Any type of rock [works with heat and pressure]?”, “Does [heat and pressure] work for all the rocks?”). Through this experimentation, Michael and Noelle were able to reorganize their thinking to the holistic relationship any rock + heat & pressure → metamorphic rock. We do not have evidence of Laura constructing this holistic relationship.

Arianna’s case helped us identify the kind of questioning and exploration that can and cannot support students as they explore a single process with multiple input materials. Similar to the other students, Arianna started with a systematic exploration of multiple materials as input for heat and pressure. However, she was not asked to articulate any relationships during this free exploration. She then moved to an exploration of multiple processes with each material, after which she was asked the question, “Can you tell me or any friend that hasn’t seen this simulation, how metamorphic rock forms?” and she stated, “I think from what I remember, heat and pressure,” illustrating the partial relationship heat & pressure → metamorphic rock. She then cooked igneous rock with heat & pressure and elaborated, “Yeah, heat and pressure with most rock” reorganizing her relationship to most rocks + heat & pressure → metamorphic rock.

The researcher then decided to direct her attention to the arrows of the diagram pointing to the arrows around metamorphic rock on the simulation in Figure 10, “do these arrows help you find what the sources of metamorphic rock are?” Arianna did not mention any materials stating, “it’s only heat and pressure looking at the arrows.” The partial relationship might have been the result of looking only at the green arrows in Figure 10 only and disregarding the arrows that begin from the input sources (in blue). It is possible that having two sets of arrows for each relationship (one pointing to the process and one pointing to the output) might encourage partial relationships.

Figure 10.

Recreation of Arianna’s tracing of the diagram to produce Metamorphic Rock. The arrows (in green) that point from heat and pressure to metamorphic rock and the arrows (in blue) between the input materials and heat and pressure.

She was then asked about other rocks working with heat & pressure, aiming to direct her attention to the various materials that can be used as inputs. Arianna responded, “Heat and pressure I’ve only seen igneous for now. But I haven’t tried sedimentary rock. [Combined sedimentary rock + heat & pressure], Metamorphic rock.” She was then prompted to try sediment as input and this ended up shifting the conversation to weathering and erosion. As a result, we do not have evidence of Arianna articulating a more holistic relationship about heat and pressure. Arianna’s case showed how multiple approaches can and should be taken to probe students’ thinking further.

4.3. Component 3—The System as a Whole

During the Cooking Rocks exploration, students started illustrating traces of conceptualizing the system as a whole by beginning to chain multiple processes together. For example, Daniel argued that, “you can’t really cool something that isn’t melted. When you cool something that is melted, it forms into a rock.” This explanation acknowledged that a material that was melted could then be cooled to form a rock, illustrating a loose chain of processes and materials. During the two simulations that followed (Bob’s Life and the George’s Life), students’ conceptualization of the rock cycle as both a cyclic process and a chain of processes and materials was more evident. Table 9 presents a summary of which students we observed demonstrating evidence of these sub-components. As the table illustrates, we have evidence from five students (except Arianna) describing the chain of processes and materials and from five students (except Michael) discussing the cyclic nature of the rock cycle. The following sections will describe examples from each simulation exploration that illustrate the nature of how students reasoned about these sub-components and the system as a whole.

Table 9.

Summary of students who demonstrated evidence of the sub-components of Component 3 of systems thinking.

4.3.1. Bob’s Life

In the Bob’s Life simulation, students were asked to move Bob through the cross-section of his environment in the Canary Islands and observe what happens as he moves through a single continuous sub-cycle through the rock cycle. This illustration of a continuous path supported five students (all except Michael) to discuss the cyclic nature of the sub-cycle in this simulation. For example, Arianna stated that “he’s getting recycled” and “it just restarts once it goes into the conduit pipe.” Daniel also acknowledged that “it’s a cycle” and “this whole cycle restarts again.” Noelle stated, “It restarts. […] because the cycle keeps going” as she motions with her finger in a circular motion over the simulation. These explanations were elicited when students were exploring or explaining what happens to Bob when he reaches the magma chamber and then subsequently travels through the conduit pipe to erupt from the volcano.

When they were asked what they noticed or how they would explain the simulation to someone else, two students (Laura and James) also identified a chain of materials and/or processes. For instance, Laura explained and gestured to the simulation (Figure 11):

The lower you get, like the deeper you get, his form changes [pointed to Bob’s form on the left of the simulation] from like it gets to the coast line [pointed to the water] it changes sediment then sedimentary rock, and then, so it cools from here [pointed to the Surface/Sea Level area where Bob would be if he was at 0 km] and turns into igneous, it has, then it breaks down to sediment [pointed to Below Shoreline area] and turns into sedimentary rock [pointed to Upper Crust area, which is where Bob currently was] because it gets compacted and then the, the pressure increases so then it turns into metamorphic for most of it [pointed to Lower Crust area], once it reaches the lava it turns back into magma. […] It turns back into magma and it goes back up into lava [used finger to trace path up to the surface].

Figure 11.

Recreation of Laura’s gestures to the approximate locations where the processes work to change Bob’s form.

Laura identified that Bob’s form was changing and connected the materials and processes together in the hypothetical situation of Bob. The rock cycle processes were not shown in this simulation, yet she mentioned cooling, compacting, and pressure, in addition to rocks “break[ing] down” as a way to describe weathering and erosion. This shows that Laura used the relationships she constructed between the materials and processes from the Cooking Rocks simulation as she explored this simulation. We also interpret Laura’s recognition that Bob would turn “back into” magma to signify a conception of a repeating sub-cycle. [Please note: Laura appears to have described the magma chamber (the large red area at the bottom of the simulation) as “reaching the lava”.] In contrast to Laura, James described the chain of materials without the connecting processes as he moved Bob,

I would say that over time a rock goes down into the, starting at sea level and then it goes down. Which [Bob] turns into sediment and then once it goes into the ground it turns into sedimentary rock and then once it goes down far enough it turns into metamorphic rock and then when it goes like, when it goes really far down it turns into magma and then once it goes deep, really, really far down it, it restarts the cycle.

As Bob moved further down in the environment, James noted that the cycle would “restart” demonstrating an understanding of the endless cycling of matter in the rock cycle. Laura and James were the only two students who explicitly connected two or more transformations of material in this simulation, illustrating the potential for this simulation to support students in connecting what they learned in the Cooking Rocks simulation to the context of this hypothetical situation. While both Laura’s and James’ responses were elicited by general questions, more specific questioning about connecting the processes and materials in the context of this simulation may have supported other students to verbally express a chain of processes and/or materials.

4.3.2. George’s Life

In the George’s Life activity on Scratch, George was incorrectly programmed to move around the rock cycle diagram providing an opportunity for students to take a more holistic view of the rock cycle (see the Section 3.2.3). First, students were asked to state what they noticed in the simulation and to identify the mistake in George’s movement. Five students (Laura, Daniel, Arianna, Michael, and Noelle) mentioned the incorrect movement of George in the simulation from metamorphic to igneous through heat and pressure. For example, Laura responded, “It’s saying that the metamorphic goes straight to igneous.”

Next, the students were asked to identify the correct path that Goerge should travel to match the story and five students (Michael, Noelle, Daniel, Laura, and James) described the correct path. We noticed that students drew from their prior explorations with Cooking Rocks to make sense of this new hypothetical situation. Michael, for instance, explained that, “if it [metamorphic rock]’s getting worn down by the water and other rocks knocking into him, it would have to go to weathering and erosion and end up as sediment.” Noelle explicitly mentioned the Cooking Rocks simulation and the holistic relationship she constructed for weathering and erosion:

Well, on the first thing, like Cooking Rocks, every time I put weather and erosion to any rock it turned into sediment [pointed to sediment on the diagram]. So that’s why I think metamorphic rock [pointed to metamorphic rock on diagram] when you go through weather and erosion [pointed to Weather and Erosion] it also turns into sediment [pointed to Sediment].

The students then worked to debug George’s path through the cycle to match the story. Two students (Laura and Michael) were able to successfully program George to move through the chain described by the story. For instance, when Laura was asked to describe the path she had programmed, she pointed to locations on the diagram stating (Figure 12),

It’s just that it goes to metamorphic, and then goes to weathering, sediment, compacting and then to sedimentary. I think it went through heat and pressure to metamorphic and then melting, magma, cooling, igneous, heat and pressure ending at metamorphic.

Laura’s description of the path repeatedly passing through metamorphic rock illustrated the cyclic nature of the rock cycle and movement through two connected loops forming sub-cycles. We noticed that asking students to explain their paths provided an insight into their construction of chains of processes and materials and the sub-cycles.

Figure 12.

Recreation of Laura’s chain of processes and materials through the Rock Cycle starting at the star and following the green arrows.

Noelle and James’ exploration was slightly different as they identified and programmed multiple possible chains for George’s movement through the cycle, which were not always aligned with the hypothetical situation of the story. For example, when Noelle was asked about how she would fix the cycle to match the story, she explained and traced the chain with her mouse (Figure 13a),

It goes down to weather and erosion, then turn[s] into sediment. And then it will go through compacting and sedimenting. And then turns into sedimentary rock. Then, goes to melting. Can it also go here? [pointed to heat and pressure coming from sedimentary rock. Researcher nodded head yes] So I’ll just do that way. [She continued tracing the path with the mouse starting from sedimentary rock—purple arrows] And then it goes through heat and pressure. And then it turns back to metamorphic rock. […] And then metamorphic rock, heat and pressure again. And then it goes back to it, metamorphic rock. Then through melting it turns into magma. And then when the magma cools, it turns into igneous rock. And then um over.

Figure 13.

(a) Recreation of Noelle’s description and tracing of how she would fix George’s path and (b) Arrows representing the multiple chains that Noelle had discussed.

As Noelle considered the path that Goerge should take, she considered multiple pathways, illustrated by blue and purple arrows diverging from sedimentary rock in Figure 13a. Noelle also included a detour in the middle of the purple chain (from metamorphic rock to heat and pressure to metamorphic rock) that did not match the story. By saying that George goes “back to” metamorphic, passes through heat and pressure “again”, or stating that it continues “over” again, we interpret Noelle to be showing evidence that a single material (metamorphic rock) can serve as a connecting point for multiple sub-cycles. Noelle was then asked how many ways there are through the cycle. She pointed to the diagram (Figure 13b) and stated,

From here [pointed to Sediment] you can go this way [pointed to Compacting and Cementing to Sedimentary Rock] and then this way [pointed from Sedimentary Rock to Melting—blue arrow], or that way [pointed from Sedimentary Rock to Heat and Pressure to Metamorphic—purple arrow] And then, can you go this way too [pointed from Sedimentary to Weathering and Erosion—orange arrow]? [Interviewer nods head] And then that way so, from here [pointed to Sedimentary], there’s three ways you can go.