Abstract

Utilizing a panel of 125 economies spanning from 1970 to 2019, we examine the role of manufacturing as a fundamental pillar of development in the era of global value chains (GVCs). We employ a layered clustering approach that categorizes countries based on income per capita and structural characteristics, such as the share of manufacturing, export complexity, resource dependence, productivity, and wages while maintaining consistency over time. Prior to 1990, most trajectories exhibited a progression from early industrialization to diversification, enhanced industrialization, increased export complexity, rising income levels, and subsequently to deindustrialization. However, post-1990, deindustrialization began to permeate middle- and low-income economies, with export complexity frequently increasing in the absence of deeper domestic industrial development. Two distinct manufacturing pathways are evident: one characterized by functional specialization amid moderate manufacturing levels and another exemplified by the East Asian model, which demonstrates sustained high manufacturing intensity. Resource-driven growth has led to income increases without significant structural transformation, and such growth has not enabled economies to achieve high-income status without initial industrialization. Manufacturing remains essential as a domestic foundation; therefore, policy efforts should focus on securing this base, enhancing capabilities within higher-value GVCs, and strategically investing resource revenues to bolster industrial capacity.

1. Introduction

Understanding the transformation of economic structures in countries is essential for explaining long-term development. Classical theorists, including Lewis (1954), Rostow (1960), and Kuznets (1971), characterized development as a sequential progression from agrarian economies to industrial ones, and ultimately to service-based economies. This shift was seen as driven by industrialization, export diversification, and increasing productivity. The structuralist perspective was further formalized and empirically tested through extensive cross-country comparisons by Chenery and Syrquin (1975) and Chenery et al. (1986), whose frameworks defined developmental benchmarks during the postwar industrialization period.

However, since the early 1990s, this conventional sequence has become increasingly unreliable. Many countries have attained middle-income status without experiencing profound industrialization, while others have faced premature deindustrialization, wherein manufacturing has declined at income levels lower than those recorded historically (Rodrik, 2016). The global fragmentation of production—intensified by global value chains (GVCs), trade liberalization, and rapid technological advancements (Baldwin, 2016)—has enabled countries to enter manufacturing through low-value-added segments, often without the accompanying structural deepening or long-term income convergence (Haraguchi et al., 2017; Sen, 2019).

This study builds upon the foundation laid by Chenery and Syrquin by updating their empirical approaches to reflect the contemporary global economy. Utilizing a layered clustering method, it examines 125 countries from 1970 to 2019, focusing on both income and structural indicators such as the share of manufacturing, export complexity, and resource dependence to compare development pathways before and after the globalization surge of the 1990s.

The analysis seeks to address three core questions: First, how have the trajectories of structural transformation shifted in light of global production realignment? Second, to what extent do contemporary development patterns diverge from classical models of sequential industrialization? Third, what new clusters of development arise from this divergence, and how do they shed light on alternative routes to income convergence?

2. Literature Review

Chenery and Syrquin’s (1975) research on structural transformation emerged during a pivotal period in mid-20th-century development theory. At that time, dominant frameworks developed by theorists such as Lewis (1954), Clark (1940), Kuznets (1971), and Rostow (1960) suggested that economic development progressed through a linear shift from agriculture and primary commodities to manufacturing, and ultimately, to services. These models focused on linear transitions and internal surpluses but depended heavily on historical narratives and selective generalizations. Importantly, they lacked the empirical rigor needed to test their applicability across diverse national contexts.

Among these theories, Rostow’s (1960) five-stage model of development stands out as one of the most detailed explanations of the development. It outlines a linear progression through five stages: Traditional Society, Preconditions for Take-Off, Take-Off, Drive to Maturity, and Age of High Mass Consumption. The early stages focus on agrarian structures with minimal productivity, followed by agricultural surpluses and infrastructure development. The Take-Off phase represents the expansion of manufacturing and exports, fueled by investment and technological diffusion. Maturity involves industrial diversification and the formation of human capital. Finally, the Age of High Mass Consumption reflects a consumer-driven economy dominated by services.

Despite its enduring influence, Rostow’s model primarily represented the historical experiences of Western industrial economies. It assumed that all nations would follow a similar developmental path while giving insufficient attention to external influences, institutional factors, or global disparities. Consequently, it had limited utility in evaluating development strategies across varied geographic and historical contexts.

Chenery and Syrquin (1975) aimed to address these limitations by adopting a comparative and quantitative methodology. They analyzed cross-national panel data to examine how sectoral output, employment, trade, and investment patterns changed with income levels. Their research revealed significant variation in development trajectories, demonstrating that industrialization did not always result from domestic surplus mobilization or infrastructural investment. Instead, many countries industrialized through trade integration and external capital inflows.

Their analysis introduced a crucial refinement to classical development theory: a broader conceptualization of capital accumulation. While Rostow emphasized the importance of domestic savings, Chenery and Syrquin highlighted the catalytic role of external sources, such as foreign direct investment (FDI), development assistance, and international borrowing. These mechanisms often compensated for domestic financial constraints and facilitated earlier industrialization in trade-dependent or smaller economies.

Chenery and Syrquin also challenged the assumption of a universally linear path of development. Their empirical work demonstrated that countries could stagnate, regress, or bypass expected transitions due to institutional rigidities, policy failures, or external shocks. This cast doubt on the predictive validity of Rostow’s deterministic framework and called for a more nuanced understanding of development pathways.

Additionally, they noted that certain countries could achieve higher-income status without undergoing significant structural transformation, particularly resource-rich nations. Under specific conditions, these resource-rich countries could reach high-income levels without completing the full sequence of industrialization. However, Chenery and Syrquin cautioned that following such resource-dependent pathways could expose these nations to structural vulnerabilities, including limited diversification, weak productivity growth, and a susceptibility to commodity price fluctuations. While they did not explicitly use the term “resource curse,” their analysis anticipated critiques from later researchers such as Auty (1993) and Sachs and Warner (1995).

Building on the insights of Chenery and Syrquin (1975), Porter (1990) developed a modernized stage model centered on international competitiveness, institutional development, and innovation. His framework shares a structural similarity to Rostow’s model regarding its sequential logic but reconceptualizes development in terms of strategic adaptation and firm-level dynamics. Porter divides economic progress into four stages: Factor-Driven, Investment-/Efficiency-Driven, Innovation-Driven, and Wealth-Driven.

In the Factor-Driven stage, countries depend on natural endowments such as labor and land. Development is stimulated by FDI and export-oriented production rather than by domestic capital as Rostow has suggested. This aligns more closely with Chenery and Syrquin’s focus on globalization and financial openness.

The Investment- or Efficiency-Driven stage corresponds to industrial take-off and early maturity. Porter (1990) emphasizes that productivity must keep pace with wage growth to maintain competitiveness. As labor costs rise, economies must begin offshoring low-value manufacturing and develop the institutional capacity necessary to sustain export-led growth, a trend that mirrors Chenery and Syrquin’s (1975) observations regarding structural evolution toward increasingly complex forms of output. This underscores that structural upgrading is not automatic but depends on policy and efficiency.

In the Innovation-Driven stage, nations must transition toward knowledge-based industries and high-value exports. Innovation becomes a proactive strategy for maintaining competitiveness in the face of rising production costs. Unlike Rostow, who regarded innovation as a byproduct of affluence, Porter (1990) considers it a key driver of economic transformation. Functional upgrading—shifting into research and development (R&D), branding, and advanced services—becomes essential. Within this framework, rising wages signify greater market sophistication and facilitate upward mobility within global value chains.

Porter’s final stage, the Wealth-Driven economy, underscores the structural risks linked to high standards of living, including institutional inertia, declining innovation, and the entrenchment of elites. Without strategic reinvestment, high-income economies may encounter stagnation or deindustrialization. This perspective resonates with Chenery and Syrquin’s warnings regarding non-linear development, highlighting that even advanced economies are susceptible to regression. Furthermore, Porter emphasized the resource path identified by Chenery and Syrquin (1975), which marks the transition from the Factor stage to the Wealth-Driven stage. He also pointed out the vulnerabilities associated with this trajectory; countries that rely on resource revenues can achieve wealth, but without structural transformation and enhancement of the fundamental indicators that enabled this wealth, their situation may deteriorate once resource revenues diminish.

Porter’s model introduces a significant structural extension: rising wages in advanced economies compel the relocation of low-value production to countries with cheaper labor. This insight paves the way for Ozawa’s (1992, 2001) work on the international division of labor. Ozawa’s “flying geese” model illustrates how industrial leadership shifts from advanced to emerging economies. As wealthy countries move production overseas to manage costs, they retain core high-value functions—such as design, innovation, and marketing—within their borders.

Ozawa (1992) argues that outward FDI from innovation-driven economies fosters industrial diffusion, enabling developing countries to absorb relocated production. However, this transfer is selective: while assembly and low-end tasks migrate, the strategic functions remain centralized. This situation results in advanced economies de-industrializing in terms of jobs while still maintaining control over the highest value-added stages. Although Porter acknowledges the importance of raising wages, he stresses the complexities that arise in sustaining competitiveness during these transitions.

Building on this, Ohno (2013, 2014) poses the question: how can late-industrializing countries that receive outsourced production achieve sustained development? Unlike Porter and Ozawa, who focus on advanced economies, Ohno centers his framework on the upgrading path for latecomers participating in global value chains (GVCs).

Ohno outlines a five-stage framework tailored for countries engaged in GVCs.

Stage 0 (“Pre-industrial”) involves minimal industrial activity and reliance on aid or commodities. Although it bears conceptual similarities to Rostow’s (1960) “Traditional Society,” this stage takes contemporary factors into account, such as post-conflict reconstruction efforts and external donor involvement.

Stage 1 (“FDI Entry”) marks the onset of export-oriented, foreign-led manufacturing. This phase resembles Porter’s (1990) “Factor-Driven” stage, characterized by production dominated by foreign enterprises and low labor costs. However, Ohno (2013) highlights the integration into GVCs as the primary mechanism for industrialization, contrasting it with the typical focus on domestic capital accumulation or infrastructure development.

Stage 2 (“Supporting Linkages”) sees domestic firms start supplying inputs and services to foreign companies, thus fostering local supply chains, enhancing domestic content, and gaining capabilities through experiential learning. This stage aligns with the early portion of Porter’s (1990) “Efficiency-Driven” phase and Rostow’s (1960) “Take-Off,” but emphasizes upgrading among domestic suppliers over broader macroeconomic transformations.

Stage 3 (“Production Capability”) focuses on developing independent production competencies. At this stage, countries begin exporting more sophisticated goods and entering higher-value segments of global value chains (GVCs), which is accompanied by rising productivity and wages. This phase corresponds with the latter part of Porter’s (1990) “Efficiency-Driven” stage and Rostow’s (1960) “Drive to Maturity,” but prioritizes production competence over broader patterns of sectoral diversification or consumer growth.

Stage 4 (“Innovation Leadership”) marks full industrial maturity, where firms develop proprietary technologies, establish global brands, and drive growth through outward FDI. At this stage, export portfolios expand to include both manufactured goods and intangible services, such R&D, design, and intellectual property (Ohno, 2013).

Ohno’s model addresses the developmental trap where countries focus on production without having control over innovation or design. His solution involves a sequenced process of capability-building, local linkages, and institutional learning. This approach directly tackles the structural imbalance highlighted by Porter and Ozawa: while outsourcing offers opportunities, upgrading necessitates internal transformation.

Despite its clarity, Ohno’s framework is not universally applicable. It is well-suited for export-oriented East Asian economies with favorable geography, institutions, and market access. However, it provides limited guidance for resource-rich or service-heavy countries that lack a strong manufacturing base. Nonetheless, it fills an important theoretical gap by adapting stage theory to the realities of globalization.

Baldwin (2006, 2013, 2016) elaborates on the global production transformation through his theory of “second unbundling.” Advances in information and communication technology (ICT) have enabled production processes to fragment across borders, with high-value functions remaining in core economies. This has led to the emergence of GVCs, where knowledge-intensive tasks are centralized, while routine manufacturing is outsourced.

Baldwin (2016) confirms the idea of Ohno (2014) that, in the GVC era, manufacturing does not automatically guarantee development. Countries can now achieve industrialization without establishing comprehensive domestic industrial ecosystems, a phenomenon he refers to as “factory-free industrialization.” This redefines the role of manufacturing from being a driver of broad-based transformation to a fragmented activity with limited developmental spillovers.

This shift impacts both developed and developing economies. Wealthy countries may lose industrial employment but retain control over design, R&D, and marketing. Developing countries often enter GVCs through low-value roles, such as assembly, without acquiring broader competencies. Industrialization can become a shortcut—a form of foreign-led growth that lacks embedded learning.

Empirical research by Haraguchi et al. (2017) supports this view. While global manufacturing output remains stable, it is concentrated geographically in a few populous countries such as China, Vietnam, and Thailand. For most latecomers to industrialization, improving their industrial standing is often blocked unless existing industries move up the value chain.

Rodrik (2016) builds on this idea with his concept of premature deindustrialization. Many countries are now losing manufacturing jobs and output before achieving high-income status. This trend is not simply a shift toward services but reflects a structural failure to maintain industrial transformation. It aligns with the GVC logic discussed by Baldwin (2016) and the geographic exclusion highlighted by Haraguchi et al. (2017). Based on evidence indicating that formal manufacturing industries exhibit strong unconditional productivity convergence across nations (Rodrik, 2013, 2016), Rodrik contends that premature deindustrialization poses significant challenges. A declining manufacturing sector at relatively low- or middle-income levels threatens to undermine one of the few avenues through which latecomer countries have historically narrowed productivity gaps.

Sen (2019) confirms this trend through sectoral employment data. Instead of a traditional progression from agriculture to manufacturing and then to services, many countries are moving directly from agriculture to low-productivity services. This indicates a breakdown in the conventional understanding of structural transformation.

Even countries engaged in manufacturing may not benefit significantly. Baldwin (2016) and Baldwin and Ito (2022) demonstrate through the Smile Curve that most value lies in upstream functions (R&D, design) and downstream activities (branding, logistics). Production alone yields diminishing returns unless it is accompanied by functional upgrading.

Research on functional specialization corroborates these findings. Stöllinger (2019) reveals that countries focused on “factory functions” generate low value-added. Peneder and Streicher (2017) note that efficiency-driven industrial upgrades may paradoxically accelerate deindustrialization. Kordalska and Olczyk (2023) show that even industrially active countries in Eastern Europe struggle with income convergence unless they transition into advanced services and innovation.

These findings challenge the relevance of classical stage models, such as Rostow’s, as well as firm-centered frameworks like Porter’s. The contemporary landscape characterized by globalization, functional segmentation, and GVCs necessitates a new analytical framework.

This study addresses this need by developing a comparative, data-driven classification of development. Using cluster analysis, it categorizes countries based on key structural indicators: manufacturing share, export complexity, average wages, capital stock per worker, resource dependence, and income. By analyzing transitions before and after 1990 (the inflection points of GVC-led globalization), we highlight the differences between the trajectories of these periods.

The selection of indicators is informed by the reviewed literature. Rostow (1960) emphasized industrialization and surplus; Porter (1990) focused on competitiveness, wages, and innovation; Ozawa (1992) and Ohno (2013) highlighted capability-building and GVC integration; the resource curse literature underscored the risks associated with commodity dependence. Together, these variables reflect both historical development drivers and modern structural constraints.

By extending the empirical tradition of Chenery and Syrquin into the post-industrial era, this study contributes a classification that reflects the real-world diversity of development paths. It acknowledges that high income is no longer attained solely due to industrial scale, but also due to strategic positioning within global production networks.

3. Materials and Methods

This section presents the stepwise procedure used to construct a layered clustering framework for classifying countries based on structural development traits. The objective is to produce a robust, transparent, and interpretable classification of development stages that allows for consistent tracking of transitions across time—particularly before and after the globalization turning point of the early 1990s. We adopt a unified clustering structure applied across all decades (1970–2019), ensuring that historical comparisons remain valid and classification remains temporally coherent.

3.1. Data Collection and Preprocessing

The dataset is constructed at the country-decade level (e.g., “Brazil 1980”), covering the period 1970–2019. Variables were selected based on literature linking structural features to development outcomes (e.g., Ohno, 2014; Rodrik, 2016). Data was obtained from the World Bank, UN COMTRADE, UNIDO, and the Penn World Table v10.0. Monetary indicators are expressed in constant 2015 USD, PPP (See Table 1).

Table 1.

Data sources and description.

3.2. Initial Clustering by GNI per Capita

GNI per capita is used as the anchor variable for initial clustering due to its interpretability and relevance to global income groupings (Han et al., 2011). Clustering is performed using the K-means++ algorithm (Arthur & Vassilvitskii, 2007) with Euclidean distance as the metric. The optimal number of clusters is determined using the Elbow method, implemented via the Kneedle algorithm (Satopaa et al., 2011), which identifies the inflection point in the within-cluster sum of squares (WCSS) curve.

While K-means has known limitations (e.g., sensitivity to non-convex clusters; Jain, 2010), its transparency and consistency make it preferable for layered classification construction.

3.3. Variable Ordering by R2-Based Feature Selection

To maintain structural interpretability, variables are layered incrementally based on least-explained variance. Following Gelman and Hill (2007), each structural indicator is regressed on GNI, and the variable with the lowest R2—i.e., the least variance explained by GNI—was selected for inclusion first. This ranking ensured that variables with the weakest direct association to GNI were evaluated early, enabling the identification of distinct informational contributions.

In each iteration, the variable with the lowest R2 (based on GNI as the response) was added to the growing predictor group. This process was repeated until all six indicators were included in the explanatory set.

3.4. Layered Clustering and Label Reordering

At each layer, K-means is applied within each parent cluster using the newly added variable. The optimal number of child clusters is again determined via the Elbow-Kneedle method. To ensure robustness, the algorithm is repeated across 100 random seeds. Cluster outcomes were considered stable if the standard deviation of assignments was below 1% (Han et al., 2011). Clustering methodologies have been implemented in Python 3.9 using standard libraries, notably scikit-learn for the k-means++ algorithm with Euclidean distance, set to n_init = 100 and max_iter = 300. The kneed library assists in optimal elbow detection. Prior to clustering, feature-wise Min-Max scaling was applied for data normalization, utilizing only standard library functions without bespoke code.

After clustering, labels are reordered based on ascending mean values of the clustering variable. This rule ensures that higher labels represent more advanced structural performance—except in the case of resource dependence, where lower values are preferred.

3.5. Structural Transitions and Post-Clustering Analysis

To analyze development trajectories, country movements across cluster labels are tracked over time using a unified classification. Transitions are evaluated across two historical periods—pre- and post-1990—to account for globalization-era structural shifts (Rodrik, 2016).

To ensure the reliability of observed transitions, a five-year persistence rule is implemented: only transitions that are sustained for at least five consecutive years are retained. This rule reduces the impact of short-term volatility, especially for countries fluctuating near structural thresholds. As a result, the filtered set of transitions is more likely to reflect substantive shifts in economic structure rather than measurement noise or temporary reversals.

This hybrid methodology offers a transparent and theoretically grounded framework for identifying development patterns and tracking structural trajectories over time.

4. Results

This section presents the main empirical findings of the study, based on a layered clustering approach applied to 125 countries from 1970 to 2019. In Section 3.1, we construct a multi-level classification using sequential clustering on income and structural indicators such as manufacturing share, resource dependence, and export complexity, resulting in 19 distinct clusters. Section 3.2 refines these classifications by filtering out short-term fluctuations to focus on stable, meaningful transitions. Section 3.3 examines development pathways both prior to and following 1990, contrasting traditional industrialization patterns with transitions influenced by accelerated globalization and deindustrialization.

4.1. Empirical Clusters from K-Means

This section presents the results of a multi-level clustering analysis developed to classify countries according to a sequential layering of structural indicators. These include GNI per capita, the share of manufacturing in total output, dependence on resource exports, total factor productivity (TFP), the proportion of mid- and high-technology exports, capital stock per worker, and average wages. The core objective of this hierarchical framework is to uncover latent structural and technological differences across economies that are not adequately captured by income-based classifications. By incrementally incorporating additional variables at each stage, the model enables a more granular differentiation of development patterns and economic structures.

The clustering procedure begins with GNI per capita as the base layer, serving as a proxy for a country’s overall economic development and income level. This initial segmentation divides countries into broad macroeconomic categories based on national income. Following the methodology specified in the earlier section, the model identifies three income clusters using threshold values of $2178 and $16,856. Accordingly, Cluster 1 includes low-income economies (GNI between $103.2 and $2178.2), Cluster 2 represents middle-income economies ($2185.9 to $16,856.7), and Cluster 3 corresponds to high-income countries ($16,874.4 to $128,981.1), as summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

1st layer of clustering. Data clustered by GNI per capita, USD.

The second layer introduces structural differentiation based on the manufacturing share in total production, selected as the next most explanatory variable using an R-squared ranking. Each of the three income groups from the first layer is further subdivided into three categories according to their level of industrialization, producing a total of nine clusters. Specifically, countries are categorized as non-industrial, industrialized, or highly industrialized within their respective income tiers. For low-income countries, a manufacturing share below 12% defines non-industrial economies, between 12% and 20.3% defines industrialized economies, and above 20.3% corresponds to highly industrialized economies. In the middle-income group, the respective thresholds are 0.9–13.2% (non-industrial), 13.2–21.7% (industrialized), and 21.7–39.1% (highly industrialized). High-income economies are divided using the thresholds of 0–14.7%, 14.7–23.5%, and 23.6–37.3%. These divisions underscore the heterogeneity of production structures even among countries with comparable income levels. By the end of this layer, the classification expands to nine clusters reflecting joint income and industrialization characteristics (summarized in Table 3).

Table 3.

2nd layer of clustering. Data clustered by manufacturing share in production, %.

The third layer incorporates resource export dependence as a differentiating variable, adding eight new splits and increasing the total number of clusters to seventeen. A threshold of approximately 60% has been established to differentiate between resource-dependent and diversified countries. For instance, within the low-income, non-industrial category, economies with resource exports ranging from 59.8% to 99.9% are classified as resource-dependent, whereas those with export shares between 11.5% and 59.5% are considered diversified. A similar cutoff (59.6%) applies to the middle-income, industrial group. In contrast, the high-income, highly industrialized group remains undivided due to a limited range of resource export levels (6.5% to 58.6%), indicating a greater degree of export diversification among the highly industrialized high-income countries. Ultimately, eight of the nine clusters from the preceding layer are divided based on this variable, with Group 9 remaining unchanged due to uniformly low levels of resource exports among its members (summarized in Table 4).

Table 4.

3rd layer of clustering. Data clustered by share of resource exports, %.

In the following step, total factor productivity (TFP) was evaluated as a candidate for further subdivision. However, this variable did not yield any statistically meaningful splits within the existing clusters. The next layer introduces technological complexity, proxied by the share of mid- and high-technology exports in total exports. This indicator reflects both a country’s capacity for innovation and the sophistication of its production structure. Unlike previous variables that produced broader segmentation, technological complexity led to only two significant subdivisions. These emerged solely among middle-income, diversified, industrial economies—where the dispersion in technological export intensity was sufficiently pronounced to warrant further differentiation.

A clear pattern emerges: export complexity tends to increase with income level. The lower-income clusters could not be further subdivided based on this indicator due to their consistently low complexity values. Notably, the Highly Industrialized Diversified Low-income group boasts the highest export complexity at 36.7, significantly surpassing all other groups, with the next highest being the Industrialized Diversified group at 31.6 in terms of mid and high-tech goods export share of total exports. Certain middle- and high-income clusters, particularly those heavily reliant on resources, also displayed limited technological sophistication and remained undivided. In contrast, clusters exhibiting consistently high complexity showed no internal differentiation. Consequently, only two groups—Group 10 and Group 12—were differentiated based on share of mid and high-tech goods export in total exports.

Within the middle-income, industrial, diversified group, a threshold of 37.2% in mid- and high-tech exports delineated the cluster into two distinct subgroups: one characterized by low technological complexity (5.7–36.8%) and another exhibiting high complexity (37.2–76.9%). A comparable group division was observed in the middle-income, highly industrial, diversified cluster, where a 36.9% threshold separated countries with low export complexity (3.97–36.5%) from those with higher levels (36.9–79.3%). These refinements enhanced the granularity of the classification within this segment of the development spectrum. Other clusters, particularly within the low-income tier, were not further subdivided at this stage, as their members exhibited uniformly low levels of technological exports. Similarly, most high-income clusters already demonstrated consistently high export complexity, resulting in limited intra-group variation and precluding any meaningful additional stratification (summarized in Table 5).

Table 5.

4th layer of clustering. Data clustered by mid- and high-tech exports share, %.

Capital stock per employee and average wage levels did not contribute to meaningful differentiation among the clusters at this stage.

In summary, the layered clustering procedure identified 19 distinct country groups, each defined by a unique combination of GNI per capita, the share of manufacturing in GDP, reliance on resource exports, and the proportion of mid- and high-technology exports. These clusters effectively capture the structural diversity of national economies across various dimensions, including income level, industrialization, resilience, specialization, and technological sophistication. Comprehensive empirical ranges and the harmonized labeling scheme—featuring operational definitions, cutoff values, and defining indicators—are detailed in Appendix A (Table A1 and Table A2).

4.2. Persistence Adjustment for Improved Transition Mapping

The finalized classification offers a more refined alternative to conventional income-based classifications. By integrating both structural and income dimensions, it reveals a wide array of development trajectories—thus providing a more comprehensive understanding of global economic heterogeneity. Table A2 (Appendix A) presents a summary of the final clustering results, highlighting the defining economic features of each group across four key indicators: GNI per capita, resource dependence, manufacturing share, and export complexity. These variables serve as the foundation for classifying clusters into developmental tiers, each reflecting distinct stages of productivity and structural transformation.

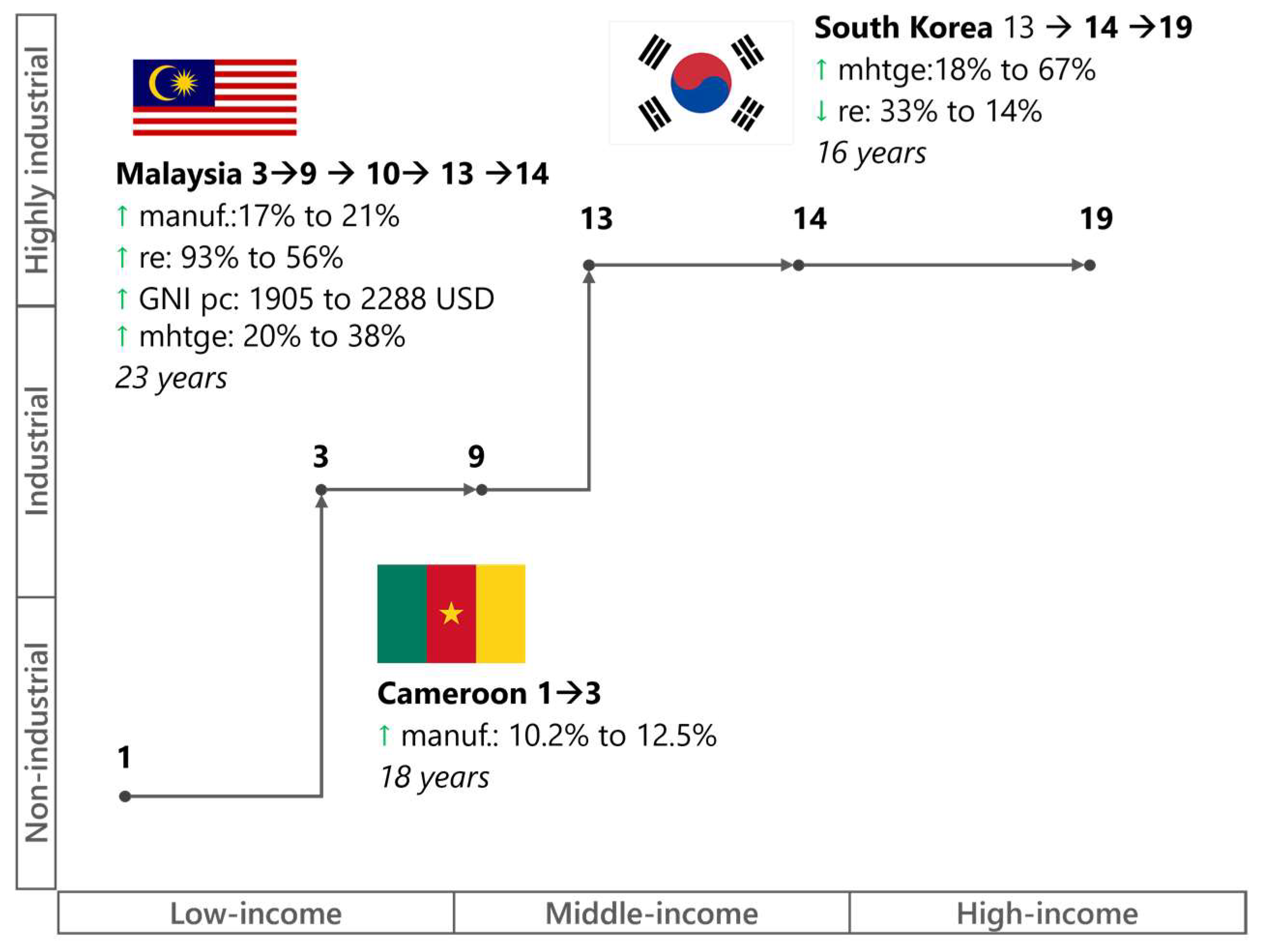

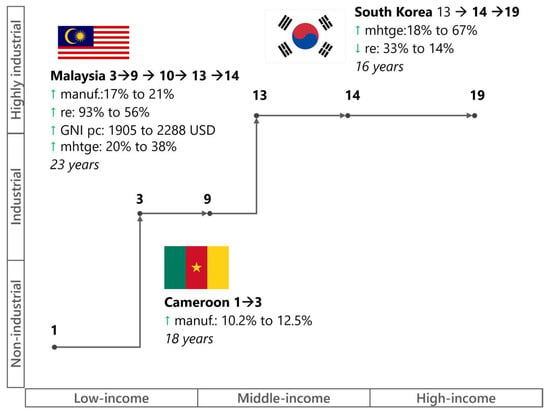

Once group characteristics were established, the analysis proceeded to track country movements across clusters to identify recurring patterns in development trajectories. Across the five-decade span, no country advanced directly from the least developed cluster (Group 1) to the most advanced (Group 19). Rather, structural progress unfolded through a sequence of gradual transitions. Illustrative examples include Cameroon’s shift from Group 1 to Group 3, Malaysia’s progression from Group 3 to Group 13, and South Korea’s advancement from Group 14 to Group 19—each reflecting the stepwise nature of sustained structural transformation.

An illustrative development trajectory from early-stage growth to advanced industrialization can be observed by combining the transitions of three countries: Cameroon, Malaysia, and South Korea. Over eighteen years, Cameroon has increased its manufacturing share of GDP from 10% to 12%, moving from Group 1—characterized by low income and minimal structural development—to Group 3. Meanwhile, Malaysia continued its ascent, advancing from Group 3 to Group 9 as its income rose from $1905 to $2288. This growth was accompanied by a reduction in the share of resource exports from 93% to 56%, enabling Malaysia to progress to the Group 10 category. The expansion of its manufacturing sector from 17% to 21.8% facilitated its advancement to Group 13. Subsequently, Malaysia progressed to Group 14, marked by an increase in export complexity from 20% to 38%. Overall, Malaysia’s transition from Group 3 to Group 14 spanned over twenty-eight years. Finally, South Korea completed the sequence by advancing from Group 14 to Group 19 in just sixteen years, with its income soaring from $5922 to $17,436—signifying its entry into the high-income, industrialized, and technologically advanced tier. This pathway is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Example of the route from low to high income, composed of partial transitions of 3 countries.

To extract broader patterns, the study quantifies transitions both within and across income tiers, thereby identifying recurring trajectories of development. By systematically mapping these movements, it becomes possible to construct stylized pathways that illustrate how countries tend to advance through successive stages of structural transformation. This analysis sheds light on the thresholds and enabling conditions required for long-term economic upgrading and sustained upward mobility.

One limitation of the clustering model is the recurrence of transitions between adjacent groups, often caused by countries fluctuating near structural thresholds. For instance, Malawi frequently shifted between Clusters 1 and 3 without undergoing substantive change, reducing the reliability of transitions as indicators of development.

To mitigate this, a five-year rule was applied: only transitions sustained for at least five consecutive years are retained. This filters out short-term volatility and ensures that only meaningful shifts contribute to the analysis. As a result, the number of transitions decreases from 457 to 197, with Malawi’s count falling from 10 to 2 (see Table 6).

Table 6.

Malawi example of the Five-Year persistence criterion adjustment.

This adjustment enhances interpretability by focusing on durable structural shifts. The final analysis draws on 198 robust transitions from 125 countries between 1970 and 2019, forming the empirical basis for identifying typical development pathways (see Appendix B, Table A3).

The analysis is divided into two periods—pre-1990 and post-1990—to reflect the structural break identified by Rodrik (2016) concerning premature deindustrialization. Of the 198 transitions, 54 occurred before 1990 and 144 after. The post-1990 increase reflects both broader country coverage (103–125 countries vs. 76–103 pre-1990) and a longer observation window (30 years vs. 20 years) (Appendix B, Table A4).

4.3. Structural Transition Pathways Before and After 1990

This section offers an overview of the transitions between cluster groups among countries, highlighting recurring development trajectories. Each transition is defined by its initial and final group, and the structural threshold specific to the transition crossed. For example, a move from Group 1 (Non-Industrial low-income) to Group 3 (Industrialized resource-dependent low-income) occurs when a country’s share in manufacturing surpasses the 12 percent threshold. In total, there were 198 between 1970 and 2019: 54 occurred before 1990, while 144 took place afterward. Among these transitions, 97 followed a manufacturing-led path, 26 were resource-led, and 75 indicated deindustrialization, with 66 of these occurring post-1990.

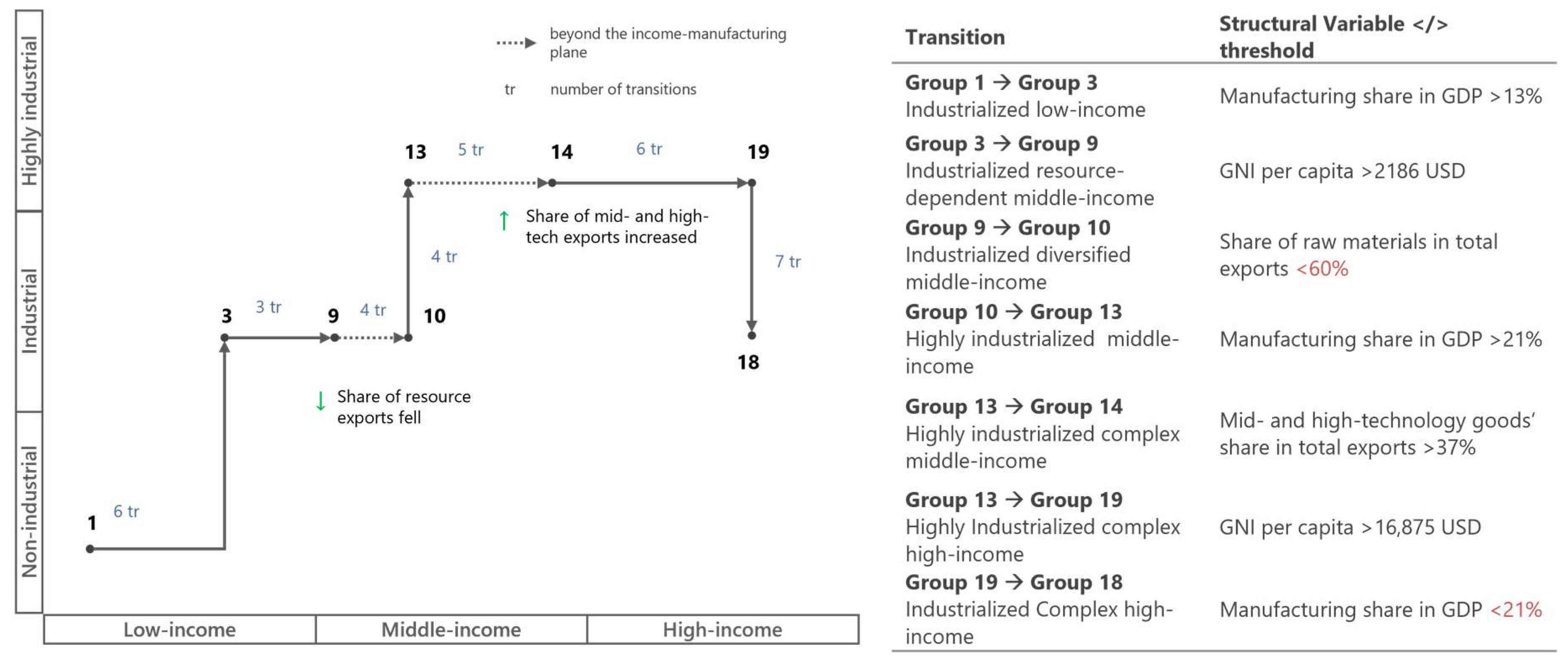

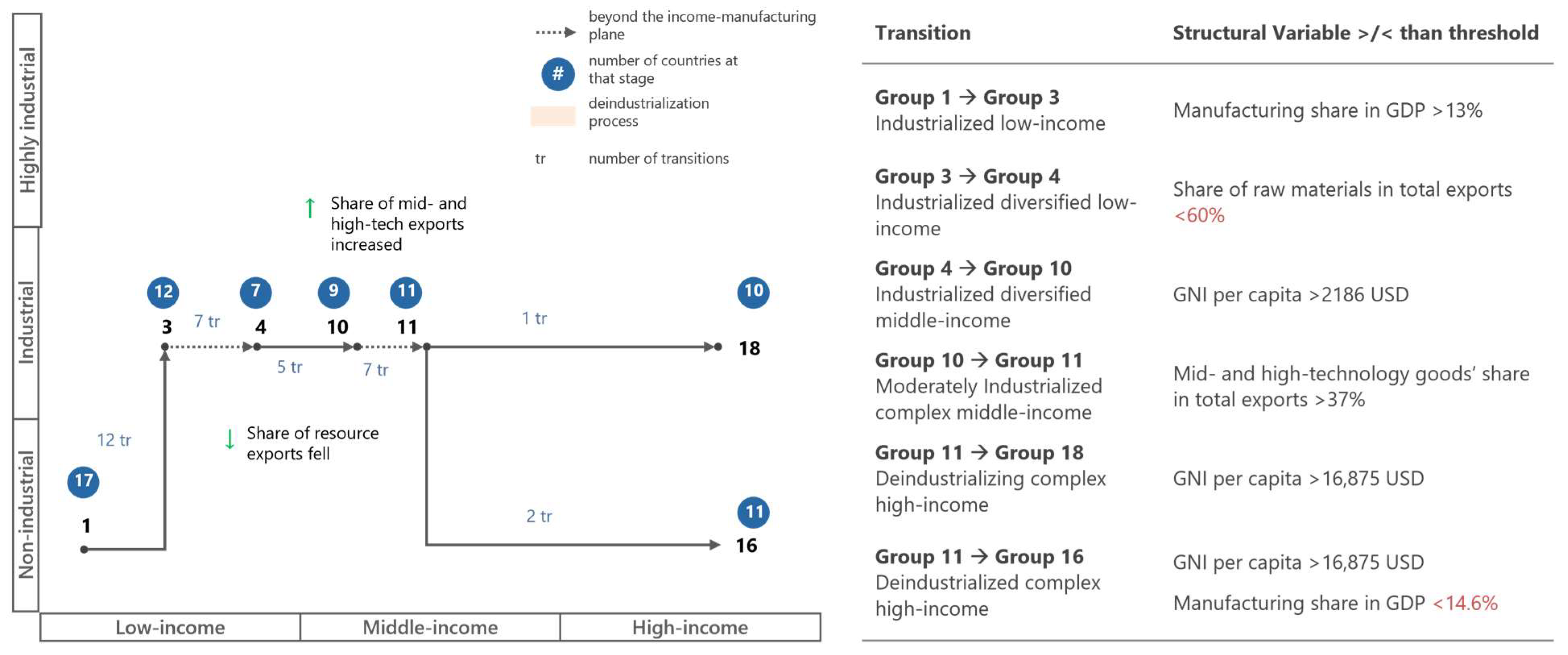

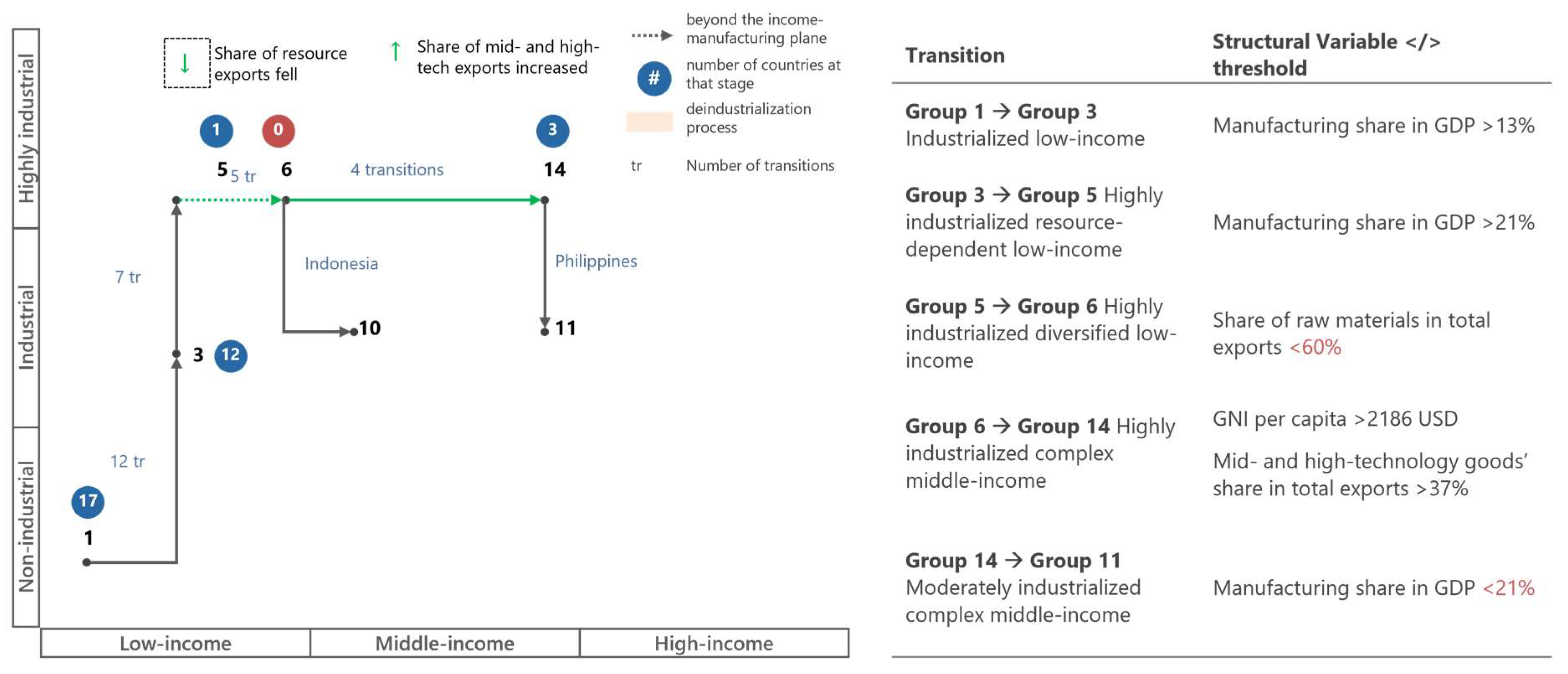

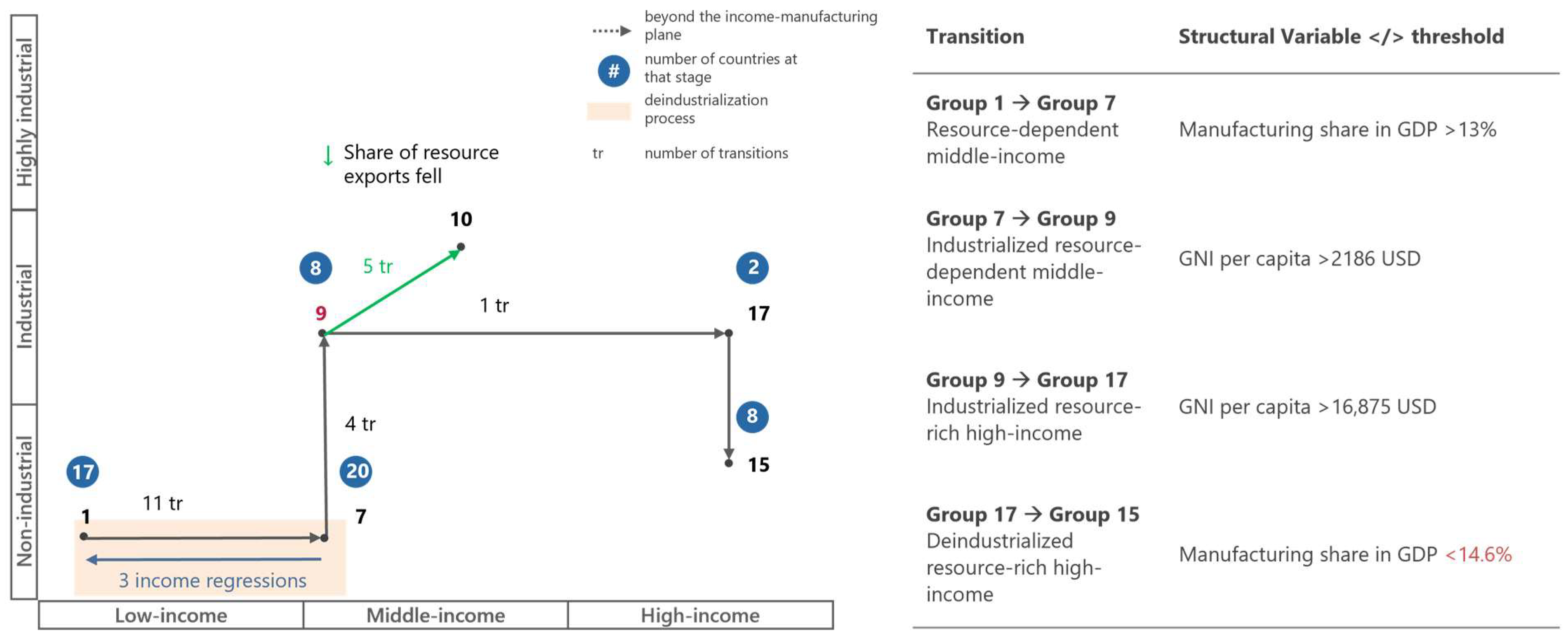

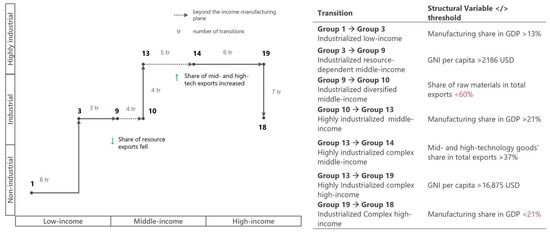

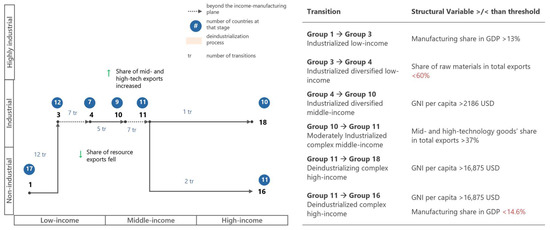

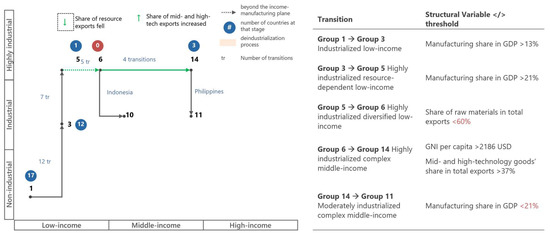

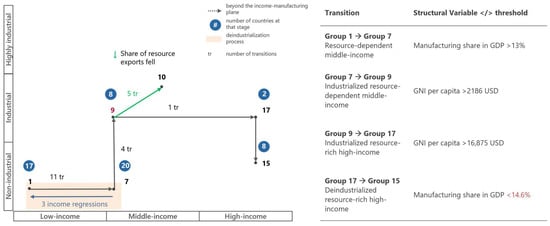

Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4 summarize the principal pathways analyzed in this paper; Appendix C reports the full list of transitions, thresholds, and country cases. Figure 1 shows the pre-1990 manufacturing-led path; Figure 2 the post-1990 modified manufacturing path; Figure 3 the East Asian manufacturing-concentration path; and Figure 4 the resource-export path. In each figure, the vertical axis denotes manufacturing intensity, and the horizontal axis denotes income category. Solid lines indicate observed transitions; dashed lines indicate movements beyond the income–manufacturing plane. The right-hand panel lists group names and the thresholds used to define transitions.

Figure 2.

Pre-1990 manufacturing-led path.

Figure 3.

Post-1990 modified manufacturing path.

Figure 4.

East Asian Manufacturing-Concentration path.

The manufacturing-led path prior to 1990, illustrated in Figure 2, outlines a typical sequence that captures 33 of the 54 economic transitions observed during this timeframe (Appendix C, Table A5). This trajectory follows an established developmental framework that begins with early industrialization, which is then followed by increases in income, diversification of exports, further industrialization, and growing complexity of exports, ultimately leading to the achievement of high-income status. Upon reaching high income, economies enter a post-industrial phase marked by deindustrialization.

Notably, the predominant early transition involved a shift from Group 1 (Non-industrial low-income) to Group 3 (Industrialized resource-dependent low-income), observed in six countries: Bolivia, Burundi, Cameroon, Malawi, Kenya, and Tunisia. However, it is significant to note that none of these nations achieved middle-income status during the interval from 1970 to 1990. Malaysia illustrates how an industrialized resource-dependent, low-income economy diversified into the middle-income range. In 1970, Malaysia was classified within Group 3, characterized by a gross national income (GNI) per capita of USD 1905, an overwhelming reliance on resource exports (approximately 92 percent), and a modest manufacturing sector contributing 13.7 percent to its GDP. Malaysia entered Group 9 (industrialized resource-dependent middle-income) once GNI per capita exceeded USD 2186. Notably, three countries accomplished this transition prior to 1990. By the mid-1980s, Malaysia had diversified sufficiently to progress to Group 10 (industrialized diversified middle-income), where manufacturing accounted for nearly 20.7 percent of GDP, resource exports made up 56 percent, and GNI reached approximately USD 4035. This transition was achieved by two countries in the pre-1990 period.

Singapore provides an illustrative example of the subsequent phases within the manufacturing-led economic pathway, advancing from Group 10 (Industrialized diversified middle income) to Group 19 (Highly industrialized complex high-income). By the 1970s, Singapore had already established itself as a diversified middle-income economy, with a GNI per capita of USD 7331. Through processes of industrial deepening, Singapore was elevated to Group 13 (Highly industrialized diversified middle income), a transition realized by other four economies before 1990. The rising complexity of its exports subsequently facilitated its advancement to Group 14 (highly industrialized complex middle income), a transition documented in five instances. By 1985, Singapore had surpassed the high-income threshold of USD 16,875, advancing to Group 19 (highly industrialized complex high-income). Manufacturing continued to rise, peaking at 27% of GDP in 2004. However, as the manufacturing share subsequently declined to below 23.6 percent, Singapore transitioned to Group 18 (Industrialized complex high-income) in 2008 despite maintaining its export sophistication. The proportion of medium- and high-technology goods was 58 percent upon entering Group 19 and increased slightly to 59 percent while in Group 18.

For context, among high-income economies, the transition from Group 19 to Group 18 during deindustrialization was a common trend. By 1970, some countries were already classified in Group 18, and between 1970 and 1990, seven additional nations—Hong Kong, Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, and the Netherlands—shifted from Group 19 to Group 18 as their manufacturing shares fell below the 23.6% threshold, despite maintaining high export complexity. Group 18 encompasses manufacturing shares ranging from 23.6% to 14.7%; notably, in the pre-1990 sample, no high-income country recorded a manufacturing share below 14.7%.

Collectively, Malaysia and Singapore exemplify the comprehensive sequence of the pre-1990 manufacturing-led pathway, encompassing the early phases of industrialization and diversification in Malaysia, culminating in an increase in the complexity of exports and the attainment of high-income status, followed by subsequent deindustrialization in Singapore. Figure 2 delineates the thresholds and indicator values that underlie these transitions.

Post-1990, the global landscape of economic development underwent a significant transformation due to widespread deindustrialization, altering the traditional manufacturing-led development path (See Figure 3; Appendix C, Table A6). While some nations adhered to established developmental paradigms, deindustrialization emerged as a common phenomenon not only for high-income countries but also across middle and low-income economies, thereby disrupting the conventional sequence of structural advancements. Among the 144 documented transitions post-1990, nearly half (66 instances) represented deindustrialization events. Notably, 45 of these events occurred in low- and middle-income economies, in stark contrast to the single instance of deindustrialization in a low- or middle-income country prior to 1990, which was Colombia in 1987 (see Appendix C, Table A7).

At the high-income tier, the typical transition from Group 19 (highly industrialized complex high-income) to Group 18 (industrialized complex high-income) continued to be observed. Nine countries followed this pathway after 1990. However, since the 1990s, several advanced economies have experienced significant declines in manufacturing, reaching levels below 14.7%. This shift led to the appearance of Group 16 (deindustrialized complex high-income) in 1993, which includes economies characterized by sophisticated exports but minimal industrial capacity. An extreme example is Hong Kong, which transitioned to Group 16 through deindustrialization from Groups 19 and 18. Hong Kong achieved high-income status before 1990 with manufacturing contributing nearly 24% of its GDP. By 2019, manufacturing had dropped to about 1%, while export sophistication increased from 40% to 42% across its reclassifications from Group 19 to Group 18 and eventually to Group 16. In total, nine economies made the transition to Group 16 during the post-1990 period.

Within the middle-income category, a notable development was the dissolution of Group 13 (Highly industrialized diversified middle income). Before 1990, four economies, including Singapore, followed a deepening sequence in which manufacturing first rose above 21.7 percent of GDP to enter Group 13, and only then did export complexity increase sufficiently to reach Group 14 (Highly industrialized complex middle income). Post-1990, only two economies entered Group 13; both did so in 1991, and by 2007, Group 13 had effectively ceased to exist. Two forces explain the disappearance of Group 13 after 1990: first, four deindustrialization transitions led countries to regress from Group 13 to Group 10 (Industrialized diversified middle income); second, the trajectory of structural upgrades increasingly inclined toward a Group 11 (Industrialized complex middle income), which emerged post-1990 as a less industrialized counterpart to Group 14. Group 11 encompasses manufacturing shares ranging from 13.2 to 21.7 percent of GDP, coupled with export complexity indices above 37 percent. Seven transitions into Group 11 were recorded post-1990, all originating from Group 10. Advancement beyond Group 11 was infrequent, with only three economies progressing further—two into Group 16 and one into Group 18.

Shifting dynamics were also observed at the low-income level. Twelve economies regressed from Group 3 (Industrialized resource-dependent low-income) to Group 1 (Non-industrial low-income) as their manufacturing sectors fell below the 12 percent threshold. More significantly, a diversification-before-income growth pattern emerged, reversing the order of steps. Prior to 1990, countries in Group 3 typically transitioned to Group 9 (Industrialized resource-dependent middle-income) as their incomes increased, followed by diversification into Group 10. Post-1990, several economies adopted a diversification-first sequence, moving from Group 3 to Group 4 (Industrialized diversified low-income) even while remaining below the middle-income classification, before subsequently advancing to Group 10. In total, seven such transitions into Group 4 were noted, one instance with Tunisia occurring before 1990 and six thereafter, of which five later progressed from Group 4 to Group 10.

Tunisia serves as a representative case illustrating how these structural shifts altered the manufacturing-led pathway (Figure 3). In 1970, Tunisia was classified in Group 1, with manufacturing contributing 9 percent to GDP, resource exports accounting for 81 percent, and a Gross National Income (GNI) per capita of USD 1149. As manufacturing surpassed the 12 percent threshold, Tunisia transitioned into Group 3. By 1986, as resource export dependence declined to below 59.6 percent, Tunisia shifted to Group 4 while remaining below the middle-income threshold. By 1994, GNI per capita exceeded USD 2186, enabling Tunisia to advance into Group 10. By 2010, export complexity reached 37 percent, although manufacturing experienced a slight decline from 16 percent to 15 percent, resulting in Tunisia’s classification in Group 11. As of 2019, GNI per capita had increased to USD 11,064, while manufacturing further declined to 14.3 percent. With the continued downward trend in manufacturing juxtaposed against stable export sophistication, Tunisia’s most plausible future trajectory suggests a shift towards Group 16 (this group encompasses a manufacturing share below 14.7%). Through this sequence, Tunisia illustrates how the post-1990 reordering operates in practice.

The second post-1990 route centered on unusually high manufacturing intensity, where economies’ manufacturing share in GDP exceeded the 20.3 percent threshold early in their development (see Figure 4; Appendix C, Table A8). This path starts with an initial phase of industrialization, where countries advance from Group 1 to Group 3, followed by an increase in manufacturing intensity above 20.3 percent to reach Group 5. Before 1990, six countries entered Group 5 (Highly industrialized resource-dependent low-income). After 1990, only Myanmar joined Group 5, and it has remained in this category as of 2019. Subsequently, five East Asian economies: China, Vietnam, the Philippines, Indonesia, and Thailand subsequently reached Group 6 (Highly industrialized diversified low-income) by reducing their dependence on resource exports to below 59.6 percent, all while still being classified as low-income based on GNI thresholds. This transition mirrors the diversification shift from Group 3 to Group 4, where diversification precedes income growth. Conversely, countries outside East Asia that reached Group 5 failed to diversify, regressing instead back to Group 3 (Industrialized resource-dependent low-income).

Among the five East Asian nations, China, Vietnam, and Thailand successfully entered Group 14 (Highly industrialized complex middle-income) by combining high manufacturing intensity with increased export complexity and income. Following 1990, new entrants to Group 14 emerged solely through this pathway, moving from Group 5 to Group 6. The previously utilized deepening route that allowed transitions from Group 10 to Group 13 ceased to produce new entrants, with the exception of Malaysia. Malaysia’s ascent began earlier, reaching Group 13 in 1991 and subsequently increasing its complexity to move into Group 14 in 1998. By 2019, Group 14 consisted of four economies: Malaysia, China, Vietnam, and Thailand.

Not all five East Asian countries that transitioned to Group 6 converged with Group 14. The Philippines also reached Group 14 in 1993; however, it later faced deindustrialization, which led to its regression to Group 11 (Industrialized complex middle-income) by 2009. In contrast, Indonesia did not achieve Group 14. After moving from Group 5 to Group 6, it ultimately stabilized in Group 10 (Industrialized diversified middle-income), where it increased its income but struggled to attain significant industrial depth and export complexity.

While the East Asian Manufacturing-Concentration path could, in theory, lead to Group 19 (Highly industrialized complex high-income), by 2019, no country pursuing this route had attained high-income status. The highest observed GNI per capita within this group was USD 10,128 in China, which falls short of the USD 16,875 threshold. As of 2019, Group 6 had no remaining members as all five East Asian economies had surpassed it, and no new entrants emerged; only Myanmar remained in Group 5, leaving Myanmar as the only candidate to advance along this trajectory. Collectively, these observations suggest that from 1970 to 2019, the East Asian manufacturing-concentration pathway exhibited limited participation and showed restricted near-term potential for transitions to high-income status.

Figure 5 illustrates the resource-export-led path, in which countries achieved income gains with limited structural change (See Appendix C, Table A9). This pattern has exhibited consistency both before and after 1990. Typically, economies progress from Group 1 (non-industrial low-income) to Group 7 (non-industrial resource-dependent middle income) upon surpassing a Gross National Income (GNI) per capita threshold of USD 2186. Prior to 1990, three nations achieved this upward transition, while six countries accomplished it in the years that followed. Notably, after 1990, certain economies categorized as Group 3 (Industrialized resource-dependent low-income) also ascended to Group 7, reaching middle-income status despite an accompanying contraction in their manufacturing share in GDP. Thus, along the resource-led path, income gains often occurred without commensurate structural change and sometimes alongside erosion of manufacturing capacity.

Figure 5.

Resource-led path.

The sustainability of this pathway proved fragile; three countries have transitioned from Group 7 back to either Group 1 due to income declines that fell below USD 2186. A notable example is Côte d’Ivoire, which recorded a GNI per capita of USD 2538 in 1970, yet fell below the middle-income threshold by 1985. By 1996, its GNI per capita had significantly dropped to USD 844, and by 2019, it had only partially recovered to USD 2036, still below its 1970 level.

Advancement from Group 7 (non-industrial resource-dependent middle-income) to high-income status is theoretically achievable; however, no country within our sample has made this transition directly. The observed upward trajectory consistently necessitated entry into Group 9 (industrialized resource-dependent middle income), which occurs when the manufacturing sector reaches at least 13.2% of GDP. This transition occurred twice before 1990 and four times subsequently.

Upon entering Group 9, the most common progression involved diversification, which required reducing resource dependence below 59.6% to access Group 10 (industrialized diversified middle income). In certain instances, countries further elevated their export sophistication to at least 37% to enter Group 11 (industrialized complex middle income). Mexico and Costa Rica are notable examples of this sequence, having advanced from Group 9 to Group 10 and subsequently to Group 11. Theoretically this route could continue to high-income, for example via transitions into Group 16 or Group 18. However, within our 1970–2019 window, no country that diversified out of the resource-led path reached high-income status.

A less common trajectory involved reaching high income without reducing resource dependence. Trinidad and Tobago moved from Group 9 to Group 17 (industrialized resource-rich high-income) between 1970 and 2010, with GNI per capita rising from USD 5554 to about USD 16,966, just above the USD 16,875 threshold, despite limited structural transformation. Notably, several major resource exporters were already classified as high-income in 1970, and their prior advancements fall outside the 1970–2019 timeframe and hence are not included in these figures.

Among high-income resource exporters, deindustrialization manifests as a shift from Group 17 (industrialized resource-rich high-income) to Group 15 (deindustrialized resource-rich high-income), as manufacturing activities decline below 14.7 percent of GDP. This trend mirrors the late-stage progression observed in high-income economies that follow manufacturing-led development, where a decline below roughly 23.6 percent indicates a transition from Group 19 to Group 18. However, this transition occurs at a lower level of manufacturing since no resource-rich country in our sample achieved the 23.6 percent threshold. Norway transitioned from Group 17 to Group 15 in 1982, and after 1990, Australia, Iceland, and New Zealand followed suit. By 2019, only Trinidad and Tobago and Bahrain remained in Group 17.

The findings reveal that, since 1990, the development trajectory centered on manufacturing has undergone significant reorganization. Initial industrialization no longer reliably leads to achieving middle-income status; instead, the deep-industrialization sequence from Group 10 to Group 13 to Group 14 has become increasingly rare. This has largely been supplanted by a moderate-intensity pathway towards higher export complexity, represented by Group 11. In the high-income tier, the trend of deindustrialization has intensified, becoming a common phenomenon post-1990. Economies have maintained complex export profiles while experiencing reduced manufacturing shares, resulting in reclassifications from Group 19 to Group 18, and, more frequently after 1990, into Group 16.

In contrast, the resource-export trajectory has shown little change: countries have continued to advance to Group 7, achieving income gains without significant structural transformation. Notably, with the exception of Trinidad and Tobago, which reached high income through an industrialized resource-dependent pathway (moving from Group 9 to Group 17), there have been no new high-income cases along this trajectory within our 1970–2019 timeframe. The discussion section contextualizes these patterns within the literature on premature deindustrialization and the fragmentation of global value chains.

5. Discussion

Prior to 1990, trajectories largely followed a classic manufacturing-led sequence. Countries typically transitioned from low-income agrarian structures to early industrialization, then to diversification, deeper industrialization, higher export complexity, and ultimately to high income, followed by deindustrialization. This pre-1990 pattern is consistent with canonical frameworks and provides the baseline for our post-1990 comparison (Chenery & Syrquin, 1975; Kuznets, 1971; Lewis, 1954; Rostow, 1960). In our classification, the sequence appears as stepwise movements across structurally distinct groups defined by income per capita, manufacturing share, export complexity, and resource dependence. For comparability over time, we apply standardized cutoffs, including 12.0 and 13.2 percent manufacturing thresholds, 21.7 percent for deep industrialization, 37 percent for export complexity, 59.6 percent for resource dependence, and a threshold of $ 16,875 in constant 2015 USD for the high-income boundary.

After 1990, the organization of global production shifted in ways that altered structural transformation. We identified 198 robust transitions, with 144 occurring after 1990 and 54 before 1990. Of the 144 post-1990 transitions, 66 were deindustrialization events, and 45 of these occurred in middle- and low-income economies. Liberalization and ICT expanded cross-border fragmentation, which lowered entry barriers into assembly while raising the bar for domestic consolidation and learning. These patterns are consistent with the second unbundling, the smile curve, and premature deindustrialization (Baldwin, 2016; Rodrik, 2016; Stöllinger, 2019; Baldwin & Ito, 2022). In high-income economies, deindustrialization intensified, reflecting the functional relocation of fabrication, while higher-value activities remained onshore. Hong Kong illustrates the extreme, with manufacturing falling from more than one-quarter of GDP to about 1 percent, while export sophistication remained high. Price effects that lowered the relative price of manufactures and rising service demand also contributed, suggesting a recomposition rather than a technological retreat (Peneder & Streicher, 2017).

The post-1990 period diverged from the classical ladder in two salient ways. First, diversification increasingly occurred before or alongside the rise to middle income. Countries that once transitioned from early industrialization to middle-income status as industrialized resource producers more often diversified while still low-income and crossed the income threshold later. Historically, initial industrialization often sufficed to achieve middle-income status; after 1990, entry typically requires both initial industrialization and early export diversification. This diversification-before-income sequence is consistent with the smile-curve logic, which locates a larger share of value in upstream and downstream functions rather than in fabrication (Baldwin, 2016; Stöllinger, 2019; Baldwin & Ito, 2022).

Second, after initial industrialization and diversification, many economies raised export complexity without further increases in manufacturing depth, because participation in GVC elevated product profiles even when a complete domestic ecosystem had not formed (Bah, 2011; Baldwin, 2016; Haraguchi et al., 2017). Tunisia illustrates this revised manufacturing-led path. It industrialized from a non-industrial, low-income economy to a resource-dependent, low-income economy, diversified while still in a low-income category, and then transitioned into an industrialized, diversified, middle-income economy, increasing export complexity later while maintaining moderate manufacturing levels.

A second post-1990 route persisted in East Asia, remaining narrow and capacity-intensive. Countries that achieved very high manufacturing shares early progressed from industrialized low-income to highly industrialized low-income, diversified at that high level of fabrication, and later raised export complexity. China, Vietnam, and Thailand reached a highly industrialized, complex middle-income position on this route. The Philippines later deindustrialized, reverting to a middle-income position, and Indonesia stabilized at a middle-income level, with a diversified industrial base, after its manufacturing share fell below the threshold for deep industrialization. By 2019, none of the economies on this manufacturing-intensive ladder had reached high income within the observation window, which underscores that fabrication-centric strategies require timely movement into upstream and downstream functions to avoid stalling (Baldwin, 2016; Stöllinger, 2019; Baldwin & Ito, 2022). The broader evidence suggests that global manufacturing did not decline. It concentrated in a small number of populous hubs, which increased the minimum scale and learning hurdles for latecomers (Baldwin, 2016; Haraguchi et al., 2017).

Resource-based development remained a viable but limited route to middle-income status. Countries either moved directly from non-industrial, low-income to non-industrial, resource-dependent middle-income, or from industrialized, resource-dependent low-income to non-industrial, resource-dependent middle-income, as income rose even while the manufacturing share fell below the industrial threshold. Three countries regressed from a resource-dependent middle-income to a low-income status within our window, which is consistent with the volatility and institutional risks highlighted in the resource-curse literature. Advancement to high income did not occur directly from the non-industrial, resource-dependent middle-income position. All resource-rich cases that reached high income passed through an industrialized, resource-dependent middle-income stage, which implies that some manufacturing capability remained a necessary stepping stone. In high-income, resource-rich positions, subsequent deindustrialization within the tier was observed, while rare instances of re-industrialization also appeared. These patterns underscore that sustained progress for resource exporters requires investment of rents in competitive diversification and resource-based industrialization, supported by domestic learning and linkages (Auty, 1993; Sachs & Warner, 1995; Haraguchi et al., 2017; Sen, 2019).

Cross-period evidence clarifies magnitudes. The number of countries that achieved middle-income status rose from 7 before 1990 to 20 after 1990. The number of entries into high-income positions increased only marginally, from 6 to 7, when counting entries from non-high-income positions as well. These raw counts are not directly comparable because the first window spans 20 years and the second spans 30 years, and because coverage expands from approximately 76 to 103 countries before 1990 to approximately 103 to 125 after 1990. Normalized by time, the rate of entry into high income declined from approximately three transitions per decade in the 1970s to 1990s to about two transitions per decade in the 1990s to 2019. The widening gap between entry into middle-income and high-income categories is consistent with insertion into GVC, which enhances diversification and measured sophistication, but falls short of fostering the domestic capabilities necessary for countries to progress into advanced functions (Baldwin, 2016; Ohno, 2013, 2014; Sen, 2019).

Taken together, the evidence resolves four recurrent pathways with clear implications for income convergence. The classical manufacturing-led pathway remains but is less prevalent. It is characterized by industrialization, diversification, deepening, rising export complexity, high income, and later deindustrialization (Chenery & Syrquin, 1975; Kuznets, 1971; Lewis, 1954; Rostow, 1960). The modified manufacturing pathway involves early industrialization and diversification, followed by higher export complexity at moderate manufacturing intensity in Group 11. It can achieve high income when functional upgrading proceeds and when manufacturing remains at least in the low-teens share (Baldwin, 2016; Haraguchi et al., 2017). The Factory Asia pathway features early and high manufacturing intensity, followed by a later rise in complexity, and remains real but narrow and capacity-intensive. As shown above, this route did not produce completed high-income transitions within our window. For successful transitions, there needs to be subsequent upgrading beyond basic fabrication (Ohno, 2013; Stöllinger, 2019; Baldwin & Ito, 2022). The resource-based pathway elevates countries to middle-income status and often limits them to a ceiling at the non-industrial, resource-dependent level. Advancement requires movement through an industrialized, resource-dependent middle-income stage, with eventual diversification and complexity gains if convergence is to continue (Auty, 1993; Sachs & Warner, 1995; Haraguchi et al., 2017). Across these pathways, we observe the continued importance of manufacturing in the successful transitions to high-income status, alongside a rising trend of premature deindustrialization. In our analysis, all notable transitions to high income occur in contexts where manufacturing shares are at least in the low teens, typically after passing through either a complex industrialized middle-income stage or a highly industrialized, complex middle-income phase. No resource-dependent economy has achieved high income without first reaching an industrialized, resource-dependent middle-income level. More broadly, we do not see sustainable transitions to high income from economies that experience deindustrialization at low or middle income, which supports Rodrik’s concern that the manufacturing escalator is being curtailed rather than replaced (Rodrik, 2013, 2016).

Policy implications follow directly. Entry into the middle-income group in the current environment requires both initial industrialization and early export diversification, often while income is still low. Convergence to high income depends on functional upgrading into upstream and downstream tasks while maintaining at least a modest domestic manufacturing base that supports learning, linkages, and scale. For resource exporters, the reliable route passes through industrialized, resource-dependent middle-income positions, with disciplined use of resource rents to build competitive supplier networks and capabilities in adjacent tradables. For manufacturing-intensive aspirants, the window is narrow without rapid movement into design, engineering, and brand-intensive functions that anchor value locally (Auty, 1993; Baldwin, 2016; Baldwin & Ito, 2022; Haraguchi et al., 2017; Ohno, 2013, 2014; Rodrik, 2016; Stöllinger, 2019).

6. Conclusions

This paper offers a comparative, data-driven analysis of development trajectories across up to 125 countries between 1970 and 2019. By integrating income per capita with structural indicators such as manufacturing intensity, resource dependence, export complexity, wages, capital stock per worker, and TFP, we identify recurring structural configurations and track their transitions before and after 1990. The resulting trajectories provide a long-run map of how countries move through different income–structure combinations and highlight both continuity with the classic manufacturing-led development model and important breaks associated with the era of hyper-globalization.

Prior to 1990, many countries followed development paths similar to the classical manufacturing-led model, commencing with early industrialization and subsequently progressing through diversification and the deepening of their economies. This process typically involved sustained increases in manufacturing intensity and, for those nations that thrived, culminated in achieving high-income status, often followed by a later phase of deindustrialization. After 1990, economic liberalization and the expansion of global value chains facilitated faster, more frequent transitions into middle-income status but also changed the way countries industrialized. In our data, deep manufacturing-led trajectories previously observed across a wider set of successful economies are increasingly concentrated in a small number of populous hubs. Many other countries reached middle-income status either as resource-based exporters, as in earlier decades, or as participants in global value chains with relatively modest domestic manufacturing bases and limited local linkages. These post-1990 patterns broadened access to middle-income positions, but relatively few of the countries that followed them subsequently moved into high-income groups. Our analysis of transitions between groups shows a marked increase in entries into middle-income categories after 1990, yet fewer observed promotions to high-income status than in the earlier period.

Within this landscape, the trajectories can be interpreted as reflecting several distinct development paths to high income, and these paths share a common manufacturing-intensive middle phase. A first path consists of large manufacturing hubs that follow a pattern close to the pre-1990 standard route: they build substantial domestic manufacturing bases, diversify and deepen production, and only later deindustrialize from a position of high income. A second path comprises economies that integrate into global value chains, expand manufacturing, and then move into high-income configurations that combine higher productivity, rising wages, and greater export complexity while retaining a non-trivial manufacturing base. In these cases, movement toward higher income is associated with a shift away from predominantly low-value fabrication toward more knowledge-intensive, higher-value-added activities. A third path involves resource-exporting countries that attain high-income status only after combining resource wealth with a significant industrial component: in our classification, all of the high-income resource economies we observe pass through industrialized, resource-dependent middle-income groups with a non-trivial share of manufacturing. Taken together, these patterns indicate that, in our sample, very different country types—manufacturing hubs, GVC upgraders, and resource-rich economies—reach high-income status only after a period in which manufacturing plays a substantial role in their structural configuration.

This empirical regularity is consistent with Rodrik’s argument that formal manufacturing exhibits strong unconditional productivity convergence and retains a distinctive role as an engine of growth (Rodrik, 2013, 2016). It is in manufacturing that firms and workers accumulate production capabilities, process expertise, and innovation skills that can later be leveraged in more advanced services and other activities. In that sense, it is not surprising that the observed routes to high income all pass through a period in which domestic manufacturing plays a role beyond the margins.

Our results also confirm that deindustrialization in low- and middle-income countries has become common in the post-1990 period: many countries in our sample have lost manufacturing share and exited industrialized middle-income configurations without ever reaching high-income status. The trajectories and existing evidence suggest that this premature deindustrialization reflects external and structural constraints rather than a benign shift into high-productivity services. Rodrik (2016) links this pattern to trade and technological changes that expose latecomer industries to intense competition and reduce the scope for labour-intensive manufacturing, with workers often moving into low-productivity services instead. Our findings are also consistent with evidence that global manufacturing has become increasingly concentrated in a small number of populous hubs, making it difficult for smaller latecomers to expand or even maintain their own manufacturing bases (Haraguchi et al., 2017). At the same time, many developing countries integrate into global value chains mainly in low-value, footloose fabrication stages, or rely heavily on resource exports, both of which weaken incentives and capabilities to build deep domestic manufacturing (Baldwin, 2016; Stöllinger, 2019). In this environment, manufacturing often peaks at modest shares of GDP and at low or middle-income levels, without the sustained upgrading along value chains that we observe in the relatively few paths that continue to high-income status in our data. This pattern is consistent with Rodrik’s notion of premature deindustrialization. It might suggest that opportunities to build and upgrade a domestic manufacturing base of the kind seen in successful latecomers have become more limited. These dynamics help to explain why, despite more frequent transitions into middle-income positions, we observe fewer promotions to high-income status in the post-1990 period.

Our analysis concludes in 2019 and does not take into account subsequent political tensions, new trade barriers, or the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, nor the heightened concerns about strategic dependencies that these disruptions have triggered in advanced economies. Recent studies on global value chains suggest that these events have encouraged firms to diversify their supplier networks and to restructure production to rely more on regional, politically stable sources (Bacchetta et al., 2023; Javorcik, 2020). Policy documents such as the Draghi (2024) report on European competitiveness similarly emphasize the necessity of de-risking supply chains by shifting away from a limited number of foreign suppliers, particularly in Asia, for semiconductors and critical raw materials, rather than pursuing rapid, large-scale reshoring. This transition, together with the gradual upgrading and relocation of some labor-intensive manufacturing stages within incumbent hubs (Haraguchi et al., 2017), may create new opportunities, as recent work on GVC reconfiguration suggests, for countries beyond the current manufacturing-intensive centers to engage in specific segments of fabrication. However, reorganizing complex value chains requires substantial coordination and entails sunk costs, which can diminish some of the productivity gains realized through long-distance specialization. As a result, any diversification-driven relocation of manufacturing activities is likely to unfold slowly and unevenly, rather than through rapid, large-scale movements (Antràs, 2020; Miroudot, 2020). The trends observed from 1970 to 2019 should therefore be viewed as a baseline for assessing whether post-2019 de-risking efforts genuinely reopen industrialization opportunities for latecomers or merely rearrange production within the existing set of hubs.

Although the layered clustering approach enhances interpretability, it does have limitations. The classification is influenced by choices regarding variable selection, scaling, and the number of clusters, though these issues are addressed through transparent, replicable criteria. Moreover, the analysis focuses on observable structural outcomes and does not directly incorporate underlying drivers such as institutional quality, industrial policy, or geopolitical factors. Data constraints also prevented the inclusion of post-1990 variables such as detailed measures of GVC positioning or service exports, which are increasingly important but unavailable for the entire period. Finally, the method cannot fully capture feedback loops between structural change and distributional or political dynamics.

Future research could build on this framework in several directions, particularly in light of the premature deindustrialization patterns highlighted here. One priority is to combine trajectory-based classifications with richer indicators of GVC participation and functional upgrading to more clearly distinguish between shallow, footloose forms of industrialization and deeper capability building. Another is to integrate institutional and policy variables to explain why some countries manage to sustain manufacturing-intensive middle-income phases while others deindustrialize early. A related avenue is to link these structural trajectories to measures of income distribution to examine how inequality shapes the capacity to sustain upgrading and whether distributional patterns follow hypotheses such as the Kuznets curve along different paths. Extending the analysis to include post-2019 data also allows assessing whether recent de-risking initiatives and changes in the global trade regime have begun to reopen industrialization opportunities for latecomers, or merely reallocated production within existing hubs.