Abstract

Building on Fox’s Scope Economy, Takahashi proposes an analysis of scope interactions in Japanese null argument constructions. Scope Economy prevents covert scope-shifting operations such as Quantifier Raising (QR) from being semantically vacuous. Equating scrambling of Japanese null arguments with QR, Takahashi argues that null arguments are also subject to Scope Economy and thus exhibit the same scope asymmetries observed in English VP-ellipsis. In this paper, we examine Korean null argument constructions, which exhibit the same patterns as their Japanese counterparts, and argue that Takahashi’s Scope Economy-based account falls short of capturing the full range of scope facts. Specifically, we show that scope asymmetries persist even when Scope Economy-violating scrambling takes place. This problem is not confined to null argument constructions but also arises in fragments. We argue that Schwarzschild’s GIVENness constraint, in conjunction with Parallelism, accounts for scope patterns in Korean null argument constructions, without recourse to Scope Economy. We further suggest that the proposed analysis can extend to English, thereby undermining the necessity of Scope Economy in both languages.

1. Introduction

Korean is one of the languages that allow quantificational null arguments. In the null argument construction in (1), the null object in (1B) receives the same interpretation as the corresponding Quantified Phrase (QP) in the antecedent sentence.1

| (1) | (Speaker) A: | John-i | taypwupwun-uy | sensayngnim-ul | conkyenghay. | |

| John-nom | most-gen | teacher-acc | respect | |||

| ‘John respects most teachers.’ | ||||||

| (Speaker) B: | Mary-to | e | conkyenghay. | |||

| Mary-also | respect | |||||

| ‘Mary also respects most teachers.’ | ||||||

Being quantificational, the null object is expected to interact with other overt QPs in a sentence. (2) shows that the null argument is indeed involved in scope interactions but in a very interesting way. In (2A), the object QP is scrambled across the indefinite subject, and when uttered alone, the sentence is ambiguous. Interestingly, when it is followed by the null argument construction in (2B), the scope of one sentence mirrors that of the other, allowing only two-way parallel interpretations. That is, when the antecedent sentence takes the object-wide scope, the null argument sentence allows only the same object-wide scope. When the antecedent takes the subject-wide scope, the null argument sentence has the same parallel scope. The other two non-parallel interpretations are not available.

| (2) | A: | [taypwupwun-uy | sensayngnim-ul]i | enu | yehaksayng-i | ti | conkyenghay. | |||

| most-gen | teacher-acc | some | female.student-nom | respect | ||||||

| lit. ‘Most teachers, some female student respects.’ | ||||||||||

| B: | enu | namhaksayng-to | e | conkyenghay. | (some > most) | (most > some) | ||||

| some | male.student-also | respect | ||||||||

| lit. ‘Some male student also respects.’ | ||||||||||

Another interesting aspect of the null argument construction is that when the subject of the null argument construction is a non-quantified NP, the antecedent is disambiguated in such a way that it allows only the subject-wide scope, as shown in (3).

| (3) | A: | [taypwupwun-uy | sensayngnim-ul]i | enu | yehaksayng-i | ti | conkyenghay. | ||

| most-gen | teacher-acc | some | female.student-nom | respect | |||||

| lit. ‘Most teachers, some female student respects.’ | (some > most) | (*most > some) | |||||||

| B: | John-to | e | conkyenghay. | ||||||

| John-also | respect | ||||||||

| lit. ‘John also respects.’ | |||||||||

English VP/vP-ellipsis constructions exhibit the same pattern. For example, when uttered alone, the antecedent sentence in (4a) is ambiguous. However, when it is followed by the elliptical sentence, only two-way parallel interpretations are allowed. Furthermore, when the subject of the elliptical sentence is a non-quantified NP, only the subject-wide scope is available, as shown in (4b) (Sag, 1976; Williams, 1977; Hirschbühler, 1982).

| (4) | a. | A boy admires every teacher. A girl does | (∃ > ∀) (∀ > ∃) |

| b. | A boy admires every teacher. Mary does | (∃ > ∀) (*∀ >∃) |

Fox (2000) provides an influential account of the contrast in (4), arguing that a principle called Scope Economy (together with a parallelism condition) captures the asymmetry in (4). Building on Fox’s analysis, Takahashi (2008) offers an account of scope interactions in Japanese null argument constructions, which exhibit the same scope pattern as those in Korean (2) and (3).

The goal of this paper is to investigate scope interactions in Korean null argument constructions. We first demonstrate that Takahashi’s (2008) Scope Economy-based account cannot fully capture the relevant scope patterns.2 As an alternative, we argue that Schwarzschild’s (1999) GIVENness constraint provides a straightforward account of the observed scope facts. This leads to the conclusion that Scope Economy is not necessary, aligning with suggestions by Tomioka (1997) and Rooth (2005).

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 introduces Fox’s (2000) Scope Economy. Section 3 discusses Takahashi’s (2008) extension of Scope Economy to Japanese null argument constructions and addresses certain issues and shortcomings that arise. In Section 4, we examine how alternative views on scrambling fare with the scope interactions in null argument constructions. In Section 5, we present an account based on Schwarzschild (1999). Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Scope Economy and Parallelism

Fox (2000) investigates the possibility of Quantifier Raising (QR) in examples such as (5). In (5a), the object QP can undergo QR over the indefinite subject, as evidenced by the availability of inverse scope. In contrast, in (5b), it is not straightforward whether QR applies, since such movement would not yield any semantic effect. To address this, Fox introduces a diagnostic tool and argues that QR in (5b) is disallowed due to an economy principle he terms Scope Economy. The definition of Scope Economy is given in (6).

| (5) | a. | A boy admires every teacher. |

| b. | John admires every teacher. |

| (6) | Scope Economy (Fox, 2000, p. 75) |

| Covert optional operations (i.e., Quantifier Raising and Quantifier Lowing) cannot be | |

| scopally vacuous. |

How can we detect that QR does not apply in (5b)? Fox suggests that an independently motivated condition on parallelism serves as a diagnostic. It is widely assumed that a certain parallelism condition must be met to license ellipsis and phonological reduction (see Lasnik, 1972; Tancredi, 1992; Chomsky & Lasnik, 1993; Fiengo & May, 1994; Fox & Lasnik, 2003, among others). Fox assumes the definition of Parallelism in (7).

| (7) | Parallelism (Fox, 2000, p. 91)3 |

| The LF of a sentence that contains the elided/downstressed material, βE, is structurally | |

| isomorphic to a sentence that contains the antecedent, βA. |

With this in mind, let us consider (4a), repeated as (8a), for convenience.4

| (8) | a. | A boy admires every teacher. A girl does | (∃ > ∀) | (∀ > ∃) |

| b. | A boy admires every teacher. A girl admires every teacher, too. | (∃ > ∀) | (∀ > ∃) |

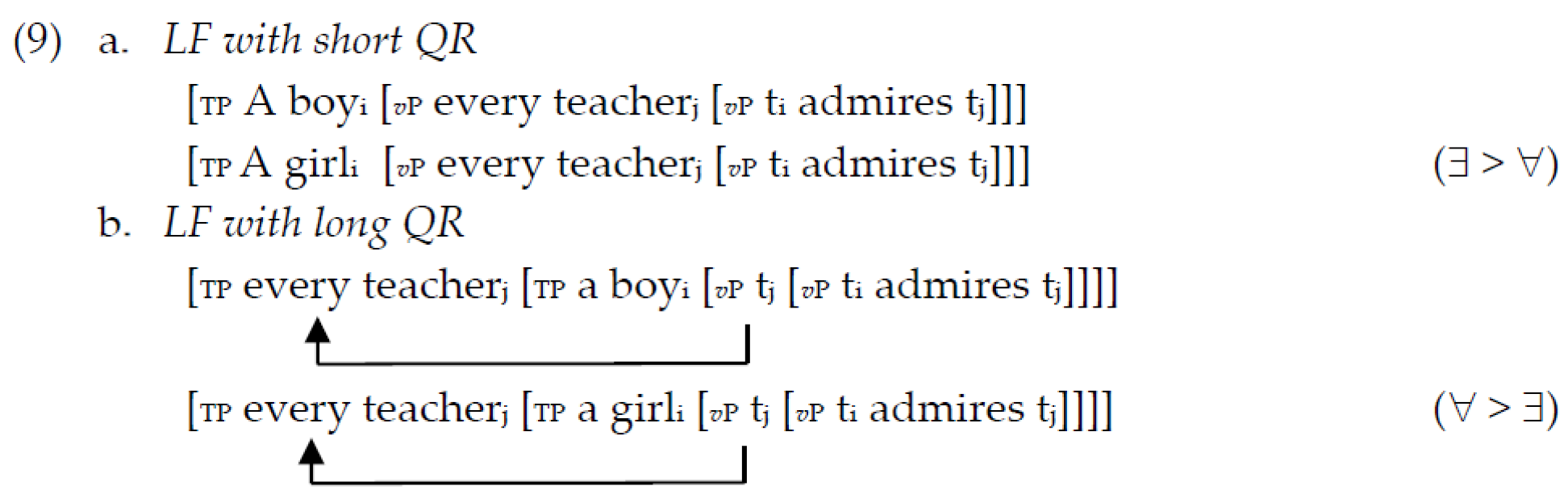

As discussed above, (8a) allows only two-way parallel interpretations. Fox attributes these interpretations to Parallelism (7). Under the assumption that universal quantifiers cannot remain in the base-generated object position due to a type mismatch (Heim & Kratzer, 1998), the object QPs in the antecedent and elliptical sentence obligatorily undergo short QR to vP, as illustrated in (9a). This satisfies Parallelism and yields the subject-wide scope in both sentences. By contrast, long QR over the subject is optional. Parallelism ensures that when the object QP undergoes long QR, it does so in parallel in both sentences, as shown in (9b). In this configuration, the object QP takes wide scope in both sentences. The same analysis applies to (8b), where the VP is phonologically reduced (or downstressed).

Let us now consider how the disambiguation effect in (4b), repeated as (10a), can be captured.

| (10) | a. | A boy admires every teacher. Mary does | (∃ > ∀) (*∀ > ∃) |

| b. | A boy admires every teacher. Mary admires every teacher, too. | (∃ > ∀) (*∀ > ∃) |

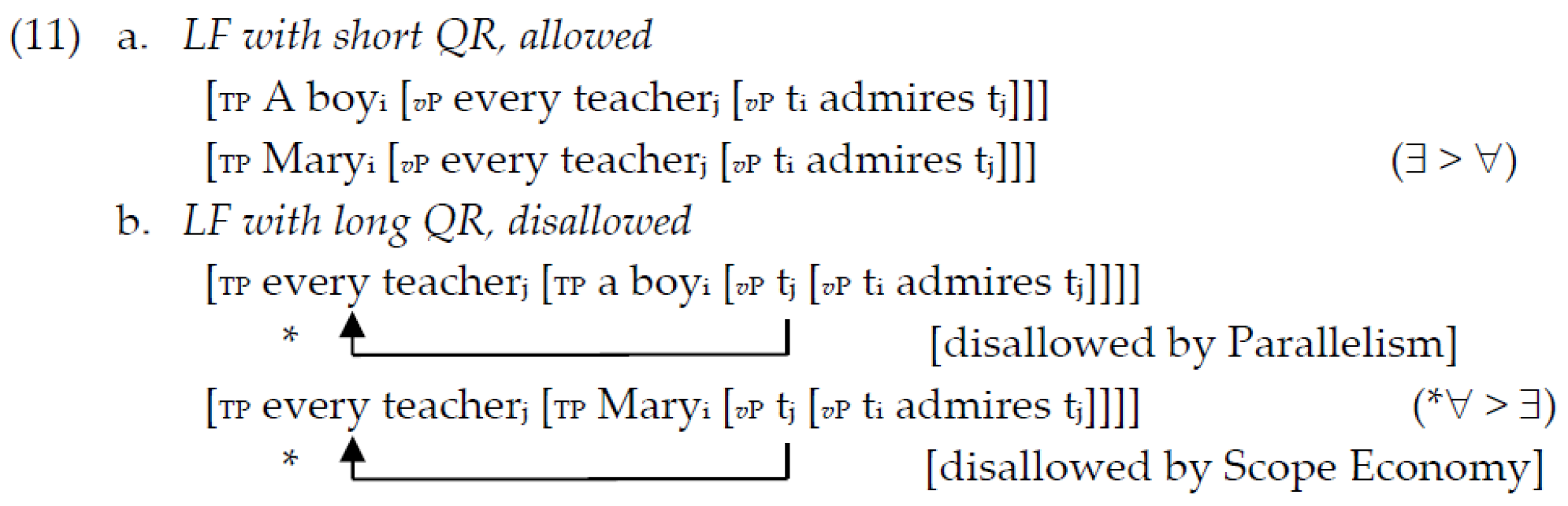

Fox (2000) argues that Scope Economy plays a crucial role in deriving the disambiguation effect in (10). The indefinite subject-wide scope obtains when the object QP undergoes obligatory short QR below the subject, as illustrated in (11a). In contrast, optional long QR is constrained by Scope Economy. As shown in (11b), long QR over the non-quantified subject is prohibited since it would be semantically vacuous. Then, Parallelism requires that the object QP in the antecedent also not undergo long QR over the subject. The only representation that satisfies both Scope Economy and Parallelism is the one in (11a), resulting in the disambiguation effect. The same applies to the phonological reduction counterpart in (10b).

Fox further argues that Quantifier Lowering (QL), like QR, is also subject to Scope Economy. The relevant examples in (12)–(13) pattern with those involving QR in the relevant respects. Specifically, ellipsis and phonological reduction in (12) permit only two-way parallel interpretations, and when the subject of the second sentence is a non-quantified NP, as in (13), only the wide scope of the indefinite subject is available.

| (12) | a. | An American runner seems to Bill to have won a gold medal. A Canadian runner | |

| does | (∃ > seem) (seem > ∃) | ||

| b. | An American runner seems to Bill to have won a gold medal. A Canadian runner | ||

| seems to Bill to have won a gold medal, too. | (∃ > seem) (seem > ∃) | ||

| (13) | a. | An American runner seems to Bill to have won a gold medal. Mary does | |

| (∃ > seem) (*seem > ∃) | |||

| b. | An American runner seems to Bill to have won a gold medal. Mary seems to Bill to | ||

| have won a gold medal, too. | (∃ > seem) (*seem > ∃) | ||

Anticipating the discussion in the following section, it is worth noting that Scope Economy is formulated as a special case of a more general economy principle that Fox (2000) terms Output Economy. Output Economy demands that optional operations—whether covert or overt—must affect the output (Fox, 2000, p. 75). It subsumes both Scope Economy and Word Order Economy. Word Order Economy requires that overt optional operations not be string-vacuous, since they would not yield any output effect at PF.5 Consequently, Word Order Economy is irrelevant to QR or QL in English, since these are covert operations. However, as will be clearer in later sections (Section 3.1 and Section 3.2), both Scope Economy and Word Order Economy play a role in Takahashi’s analysis of scope phenomena in null argument constructions.

In the next section, we turn to scope interactions in Korean null argument constructions and examine Takahashi’s (2008) Scope Economy-based account in detail.

3. Scope in Null Argument Constructions

3.1. Scope Economy and Null Argument

In languages such as Korean and Japanese, when quantified NPs appear in the canonical SOV order, only the surface scope is available, as illustrated with the Korean sentence in (14). This scope rigidity has been widely taken as indicating that these languages lack covert QR (Kuno, 1973; Kuroda, 1971; Hoji, 1985; S.-H. Ahn, 1990; Sohn, 1995; Watanabe, 1998; Yatsushiro, 2001).6 However, when scrambling occurs, the sentence becomes ambiguous, as shown in (15). Saito (1989) suggests that the ambiguity arises since the scrambled object QP can optionally be undone/reconstructed at LF. Such reconstruction yields the narrow scope interpretation of the object.

| (14) | enu | yehaksayng-i | taypwupwun-uy | sensayngnim-ul | conkyenghay. | |

| some | female.student-nom | most-gen | teacher-acc | respect | ||

| ‘Some female student respects most teachers.’ | (some > most) (*most > some) | |||||

| (15) | [taypwupwun-uy | sensayngnim-ul]i | enu | yehaksayng-i | ti | conkyenghay. | |

| most-gen | teacher-acc | some | female.student-nom | respect | |||

| lit. ‘Most teachers, some female student respects.’ | (some > most) (most > some) | ||||||

Let us now consider scope interactions in null argument constructions. When the sentence in (16A) is followed by the null argument construction in (16B), only the subject-wide scope is available for both sentences. As Takahashi (2008) notes for Japanese, the null argument in (16B) may be interpreted as an E-type pronoun (Evans, 1980), under which the group of teachers respected by some male student is identical to the group respected by some female student. Crucially, however, (16B) also allows for an interpretation in which the two groups differ. The availability of this interpretation in (16B) supports the view that null arguments can be derived by ellipsis, as indicated with strikethrough in (16B’) (Huang, 1991; Oku, 1998; S. Kim, 1999; Saito, 2007; Takahashi, 2008; Takita, 2011; Lee, 2011; Park & Bae, 2012; Sakamoto, 2020; Fujiwara, 2022; H. Kim, 2023, among many others).7 Given the SOV order in (16A) and (16B), only the subject-wide scope is available in both sentences.8

| (16) | A: | enu | namhaksayng-i | taypwupwun-uy | sensayngnim-ul | conkyenghay. | |||

| some | male.student-nom | most-gen | teacher-acc | respect | |||||

| ‘Some male student respects most teachers.’ | |||||||||

| B: | enu | yehaksayng-to | e | conkyenghay. | (some > most) (*most > some) | ||||

| some | female.student-also | respect | |||||||

| lit. ‘Some female student also respects.’ | |||||||||

| B’: | enu | yehaksayng-to | conkyenghay. | ||||||

| some | female.student-also | most-gen | teacher-acc | respect | |||||

| ‘Some female student also respects most teachers.’ | |||||||||

With this background, let us consider the two-way parallel interpretations observed in (2), repeated as (17), for convenience. Observing that the Japanese counterpart exhibits the same scope interpretations, Takahashi (2008) argues that Fox’s Scope Economy, in conjunction with Parallelism, can straightforwardly account for them. In the rest of this section, we introduce Takahashi’s analysis.

| (17) | A: | [taypwupwun-uy | sensayngnim-ul]i | enu | yehaksayng-i | ti | conkyenghay. | ||||

| most-gen | teacher-acc | some | female.student-nom | respect | |||||||

| lit. ‘Most teachers, some female student respects.’ | |||||||||||

| B: | enu | namhaksayng-to | e | conkyenghay. | (some > most) (most > some) | ||||||

| some | male.student-also | respect | |||||||||

| lit. ‘Some male student also respects.’ | |||||||||||

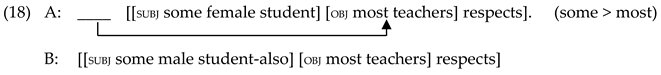

According to Takahashi’s (2008) analysis, the subject-wide scope in both sentences arises when the scrambled object in the antecedent sentence (17A) is reconstructed at LF, as illustrated in (18A) (where corresponding English words are used for ease of exposition). This reconstruction satisfies Parallelism at LF, thereby licensing ellipsis of the object at PF (see Takahashi, 2013, 2025, for supporting arguments in favor of Parallelism in null argument constructions).

The object-wide scope, on the other hand, obtains when the object in the null argument sentence (17B) undergoes scrambling in overt syntax (prior to ellipsis at PF). At LF, Parallelism is satisfied, as shown in (19), thereby licensing ellipsis of the scrambled object. The other two non-parallel LF representations are ruled out by Parallelism, and thus the corresponding non-parallel interpretations are disallowed.

| (19) | A: | [OBJ most teachers]i [[SUBJ some female student] | ti | respects] | (most > some) |

| B: | [OBJ most teachers]i [[SUBJ some male student-also] | ti | respects] |

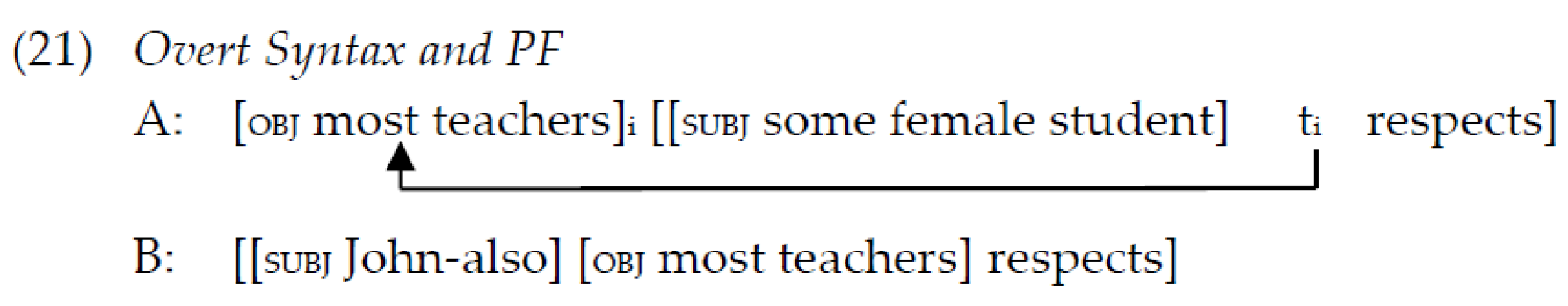

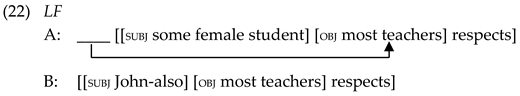

As mentioned above, the examples in (3), repeated as (20), allow only the subject-wide scope. These are structurally identical to (17), except that the elliptical sentence in (20B) contains a non-quantified subject. The overt syntax/PF and LF representations assumed by Takahashi (for Japanese counterparts) are given in (21) and (22), respectively. In the overt syntax, the object in (20A) undergoes scrambling, as shown in (21A). Subsequently, at LF, the scrambled object in (20A) can be reconstructed, as shown in (22A). The LF representations in (22) satisfy Parallelism, thereby yielding the subject-wide scope.9 Since Parallelism is satisfied, ellipsis of the object is licensed at PF in (21B).

| (20) | A: | [taypwupwun-uy | sensayngnim-ul]i | [enu | yehaksayng-i | ti | conkyenghay]. | ||

| most-gen | teacher-acc | some | female.student-nom | respect | |||||

| lit. ‘Most teachers, some female student respects.’ (some > most) (*most > some) | |||||||||

| B: | John-to | e | conkyenghay. | ||||||

| John-also | respect | ||||||||

| lit. ‘John also respects.’ | |||||||||

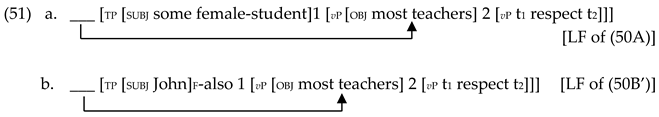

Crucially, under Takahashi’s analysis, (20) does not allow the overt syntax/PF and LF representations illustrated in (23) and (24), respectively, due to Fox’s (2000) Output Economy. Recall that Output Economy constrains both covert optional operations and overt optional operations, allowing them only when they affect the output. Assuming with Saito (1989) that scrambling is an optional operation, Takahashi claims that its application as in (23B) does not yield any output effect (p. 324); it is semantically vacuous (since it moves the object QP over the non-quantified subject) and phonetically vacuous (since the scrambled object is elided at PF).10 Consequently, the LF in (24B) is not allowed. Parallelism then prohibits the LF in (24A), and, as a result, the object-wide scope is not permitted, just as the analysis predicts.

| (24) | LF, disallowed | ||||

| A: | [OBJ most teachers]i [[SUBJ some female student] | ti | respects] | ||

| B: | [OBJ most teachers]i [[SUBJ John-also] | ti | respects] | ||

In the next section, we critically examine Takahashi’s analysis, considering the relevant phenomena from different analytical perspectives.

3.2. Phonological Reduction

Recall that under Takahashi’s analysis of unambiguous sentences such as (20), it is crucial that the null object QP not undergo scrambling; otherwise, it would incorrectly yield an object-wide scope interpretation. This also applies to English VP-ellipsis and phonological reduction in (10), where Scope Economy prohibits QR of the object QP over the non-quantified subject. For the sake of argument, let us now imagine a hypothetical situation in which the object QP in English could undergo QR over a non-quantified subject. In such a case, the object-wide scope would be predicted to be allowed. Of course, this prediction cannot be directly tested, since English QR is always covert. Crucially, however, unlike English, Korean allows overt scrambling of (non-elided) object QPs over subjects of any type. This property provides a direct empirical test for evaluating Takahashi’s proposal that Output Economy constrains scope interactions in null argument constructions.

The case at issue involves phonological reduction. Recall that Fox argues that both VP-ellipsis and the corresponding phonological reduction in English are constrained by Scope Economy, exhibiting the same scope patterns. If, as Takahashi proposes, null argument constructions are constrained by Scope Economy and Word Order Economy, the prediction is that the corresponding phonological reduction likewise should be subject to both constraints, yielding the same scope patterns.

To test this prediction, let us first reconsider the null argument construction in (17), which allows two-way parallel interpretations. Recall that under Takahashi’s Scope Economy-based analysis, object-wide scope becomes available only if the elided object QP occupies the scrambled position. This prediction can be directly tested with phonological reduction, as shown in (25). In (25), when the antecedent sentence (25A) is followed by the sentence in (25B), where the object is phonologically reduced, only the subject-wide scope interpretation is allowed. This is expected: given that (25B) reflects the basic SOV word order, only the subject-wide scope is possible, and Parallelism ensures that the scrambled object in the antecedent sentence (25A) must be reconstructed at LF. This yields the subject-wide scope interpretation in both sentences. By contrast, when the phonologically reduced object in (25B’) is scrambled, two-way parallel readings arise, as Takahashi’s analysis predicts. When the scrambled objects remain in their surface (scrambled) positions at LF, the object-wide scope obtains in both the sentences. When they are reconstructed at LF, the subject-wide scope results. Thus, the scope interpretations observed with phonological reduction in (25) strongly support Takahashi’s analysis.

| (25) | A: | [taypwupwun-uy | sensayngnim-ul]i | enu | yehaksayng-i | ti | conkyenghay. | |||||||

| most-gen | teacher-acc | some | female.student-nom | respect | ||||||||||

| lit. ‘Most teachers, some female student respects.’ | ||||||||||||||

| B: | enu | namhaksayng-to | [taypwupwun-uy | sensayngnim-ul] | conkyenghay. | |||||||||

| some | male.student-also | most-gen | teacher-acc | respect | ||||||||||

| ‘Some male student also respects most teachers.’ | (some > most) (*most > some) | |||||||||||||

| B’: | [taypwupwun-uy | sensayngnim-ul]i | enu | namhaksayng-to | ti | conkyenghay. | ||||||||

| most-gen | teacher-acc | some | male.student-also | respect | ||||||||||

| lit. ‘Most teachers, some male student also respects.’ (some > most) (most > some) | ||||||||||||||

Takahashi’s analysis, however, fails to account for the disambiguation effect observed in (26), where only the subject-wide scope is available.11 Note first that in (26B), the phonologically reduced object remains in situ and the antecedent sentence in (26A) permits only the subject-wide scope interpretation, resulting in a disambiguation effect. This aligns with Takahashi’s prediction; when the scrambled object in (26A) is reconstructed at LF, Parallelism is satisfied, and the subject-wide scope interpretation obtains. The problem arises in (26B’), where the phonologically reduced object is scrambled. Under Takahashi’s analysis, this configuration is predicted to permit the object-wide scope, because both sentences contain scrambled objects at LF (which satisfy Parallelism). Contrary to this prediction, however, the interpretation still patterns with (26B); only the subject-wide scope is allowed. This result is unexpected, especially considering that scrambling of the object QP in (26B’) does not violate Output Economy; Scope Economy is irrelevant here, since the scrambling is overt, and Word Order Economy is obeyed, since the operation is not string-vacuous. Thus, the unavailability of the object-wide scope in (26B’) poses a problem for Takahashi’s account.

| (26) | A: | [taypwupwun-uy | sensayngnim-ul]i | enu | yehaksayng-i | ti | conkyenghay. | ||||

| most-gen | teacher-acc | some | female.student-nom | respect | |||||||

| lit. ‘Most teachers, some female student respects.’ (some > most) (*most > some) | |||||||||||

| B: | John-to | [taypwupwun-uy | sensayngnim-ul] | conkyenghay. | |||||||

| John-also | most-gen | teacher-acc | respect | ||||||||

| ‘John also respects most teachers.’ | |||||||||||

| B’: | [taypwupwun-uy | sensayngnim-ul]i | John-to | ti | conkyenghay. | ||||||

| most-gen | teacher-acc | John-also | respect | ||||||||

| lit. ‘Most teachers, John also respects.’ | |||||||||||

Note further that the Scope Economy-based account incorrectly predicts not only that the object-wide scope should be available, but that it should, in fact, be the only available interpretation for the pair (26A) and (26B’). The reasoning is as follows: For the subject-wide scope to be derived, both the scrambled objects in (26A) and (26B’) must be reconstructed at LF. However, Scope Economy prohibits the reconstruction of the scrambled object in (26B’), since it would be semantically vacuous. Consequently, it is predicted that only the object-wide scope should be available. This prediction is clearly falsified, since the attested interpretation in (26A) and (26B’) is precisely the opposite; only the subject-wide scope is available.

The disambiguation effect observed in the pair (26A) and (26B’) also presents a non-trivial challenge to Takahashi’s analysis of null argument constructions. Recall that under his analysis, the null object QP in (20B) is not allowed to undergo scrambling over a non-quantified subject. However, (26B’), which involves a phonologically reduced object, shows that whether or not scrambling over the non-quantified subject occurs, the resulting interpretation remain the same (i.e., only the subject-wide scope is available). This, in turn, indicates that the scope interpretation is unaffected by whether the null object QP in (20B) undergoes scrambling, contradicting the prediction made by the Scope Economy-based account.

The issue appears to be more general. Consider the object ellipsis case in (27B) and the corresponding phonological reduction in (27B’), which are possible responses to the antecedent sentence in (27A). In the antecedent sentence in (27A), the subject is a non-quantified NP. Under the Scope Economy-based analysis, the elided object in (27B) is assumed to remain in its canonical object position. Parallelism then requires that the scrambled object in (27A) be reconstructed at LF. However, Scope Economy prohibits this reconstruction since it would be semantically vacuous. As a result, Parallelism cannot be satisfied, and ellipsis or phonological reduction should therefore not be licensed, contrary to fact. Reversing the structure, as in (28), raises the same issue.

| (27) | A: | [taypwupwun-uy | sensayngnim-ul]i | Mary-ka | ti | conkyenghay. | ||||

| most-gen | teacher-acc | Mary-nom | respect | |||||||

| lit. ‘Most teachers, Mary respects.’ | ||||||||||

| B: | John-to | e | conkyenghay. | |||||||

| John-also | respect | |||||||||

| lit. ‘John also respects.’ | ||||||||||

| B’: | John-to | [taypwupwun-uy | sensayngnim-ul] | conkyenghay. | ||||||

| John-also | most-gen | teacher-acc | respect | |||||||

| ‘John also respects most teachers.’ | ||||||||||

| (28) | A: | Mary-ka | [taypwupwun-uy | sensayngnim-ul] | conkyenghay. | |

| Mary- nom | most- gen | teacher-acc | respect | |||

| B: | [taypwupwun-uy | sensayngnim-ul]i | John-to | ti | conkyenghay. | |

| most | teacher- acc | John-also | respect | |||

In the next section, we discuss another type of elliptical construction, fragments, and demonstrate that they also present challenges for the Scope Economy-based account.

3.3. Fragments

Korean allows a wide range of fragments. Although fragmentary expressions lack overt full-fledged sentential structure, they are nevertheless interpreted as having full sentential meanings. Under the standard assumption that fragments involve remnant fronting, followed by TP-ellipsis (Morgan, 1973; J.-S. Kim, 1997; Merchant, 2004, 2010; Park, 2005, 2013, among many others),12 we expect that the scope interactions observed in null argument constructions should also arise in fragments. In this section, we show that the relevant fragments indeed exhibit the same scope patterns, thereby posing a similar challenge to the Scope Economy-based account.

Let us first consider the fragment in (29B). Given that (29A) reflects the basic word order where the indefinite subject precedes the object QP, in isolation it allows only the surface scope, i.e., the subject-wide scope. (29B) involves remnant fronting of the object QP over the indefinite subject, followed by TP-ellipsis. As noted above and discussed further below, this configuration allows scope ambiguity when considered in isolation. However, as observed by Park (2003), when (29B) follows the antecedent (29A), a disambiguation effect arises, mirroring the pattern in the null object counterpart. The Scope Economy-based analysis could account for this fact by assuming that, due to Parallelism, the fronted object in the elliptical sentence in (29B) must be reconstructed at LF.13 This reconstruction results in the subject-wide scope, which is the only available interpretation. Note here that the same scope interpretation is observed with phonological reduction as shown in (29B’).

| (29) | A: | enu yehaksayng-i | taypwupwun-uy | paywu-lul | coahay. | |||||||||

| some female.student-nom | most-gen | actor-acc | like | |||||||||||

| ‘Some female-student likes most actors.’ | ||||||||||||||

| B: | [taypwupwun-uy | kaswu-to]i | ||||||||||||

| most-gen | singer-also | some | female.student-nom | like | ||||||||||

| lit. ‘Most singers also (some female student likes).’ | (some > most) (*most > some) | |||||||||||||

| B’: | [taypwupwun-uy | kaswu-to]i | [TP | enu | yehaksayng-i | ti | coahay]. | |||||||

| most-gen | singer-also | some | female.student-nom | like | ||||||||||

| lit. ‘Most singers also, some female student likes.’ | (some > most) (*most > some) | |||||||||||||

Given the discussion above, another prediction regarding fragments is that if ambiguous interpretations are ever permitted, they should be restricted to two-way parallel interpretations. This prediction is borne out, as shown in (30). The example in (30) is identical to (29), except that the object in the antecedent is scrambled. While each sentence is ambiguous, when (30B) follows (30A), only two-way parallel interpretations are available. (The same pattern holds in the corresponding phonological reduction.) This interpretive pattern could be accounted for by extending Takahashi’s account of null argument constructions to fragments.

| (30) | A: | [taypwupwun-uy | paywu-lul]i | enu | yehaksayng-i | ti | coahay. | |||

| most-gen | actor-acc | some | female.student-nom | like | ||||||

| lit. ‘Most actors, some female-student likes.’ | ||||||||||

| B: | [taypwupwun-uy | kaswu-to]i | ||||||||

| most-gen | singer-also | some | female.student-nom | like | ||||||

| lit. ‘Most singers also (some female student likes).’ | (some > most) (most > some) | |||||||||

As with the null argument construction, the same disambiguation effect is observed when the subject fragment is a non-quantified NP. The relevant example is given in (31) below.

| (31) | A: | [taypwupwun-uy | paywu-lul]i | enu | yehaksayng-i | ti | coahay. | |||||

| most-gen | actor-acc | some | female.student-nom | like | ||||||||

| lit. ‘Most actors, some female-student likes.’ | ||||||||||||

| B: | John-to | |||||||||||

| John-also | most- gen | actor-acc like | ||||||||||

| lit. ‘John also (likes most actors).’ | (some > most) (*most > some) | |||||||||||

(31B) involves fronting of the non-quantified subject John, followed by TP-ellipsis. When this fragment follows (31A), (31A) becomes disambiguated; only the subject-wide scope is available in (31A), patterning with the corresponding null argument construction in (20).

However, the acceptability of (32) and (33) poses a problem for the Scope Economy-based account. Recall from Section 3.1 that Korean lacks covert QR (or, LF-scrambling), which implies that the object in (32A) stays in situ throughout the derivation. In (32B) and (32B’), Scope Economy prohibits reconstruction of the fronted object since it would be semantically vacuous. This predicts a violation of Parallelism and thus that both ellipsis in (32B) and phonological reduction in (32B’) should be disallowed, contrary to fact. The same problem arises in the reversed environment in (33), where Scope Economy prohibits reconstruction of the scrambled object in the antecedent.

| (32) | A: | John-i | taypwupwun-uy | paywu-lul | coahay. | |||||

| John-nom | most-gen | actor-acc | like | |||||||

| ‘John likes most actors.’ | ||||||||||

| B: | [taypwupwun-uy | kaswu-to]i | ||||||||

| most-gen | singer-also | John-nom | like | |||||||

| lit. ‘Most singers also (John likes).’ | ||||||||||

| B’: | [taypwupwun-uy | kaswu-to]i | [TP John-i | ti | coahay]. | |||||

| most-gen | singer-also | John-nom | like | |||||||

| lit. ‘Most singers also (John likes).’ | ||||||||||

| (33) | A: | [taypwupwun-uy | paywu-lul]i | Mary-ka | ti | coahay. | |||||

| most-gen | actor-acc | Mary-nom | like | ||||||||

| lit. ‘Most actors, Mary likes.’ | |||||||||||

| B: | John-to | ||||||||||

| John-also | most-gen | actor-acc | like | ||||||||

| lit. ‘John also (likes most actors).’ | |||||||||||

| B’: | John-to | taypwupwun-uy | paywu-lul | coahay. | |||||||

| John-also | most-gen | actor-acc | like | ||||||||

| ‘John also likes most teachers.’ | |||||||||||

In this section, we have shown that scope interpretations in fragments pattern with those in their null argument counterparts, and present the same empirical challenge for the Scope Economy-based account.14 Takahashi (2008) assumes that scrambling is an optional operation, and that scrambling of the null argument is thus subject to Scope Economy. In light of the issues discussed above, it is necessary to examine alternative views of scrambling that do not treat it as an optional operation. In the next section, we discuss two major proposals: Bošković and Takahashi (1998) and Miyagawa (2011). As will be shown, although Scope Economy is irrelevant under these approaches, we reach the same conclusion that the disambiguation effect remains unexplained.

4. What if Scrambling Is Not Optional?

4.1. Bošković and Takahashi (1998)

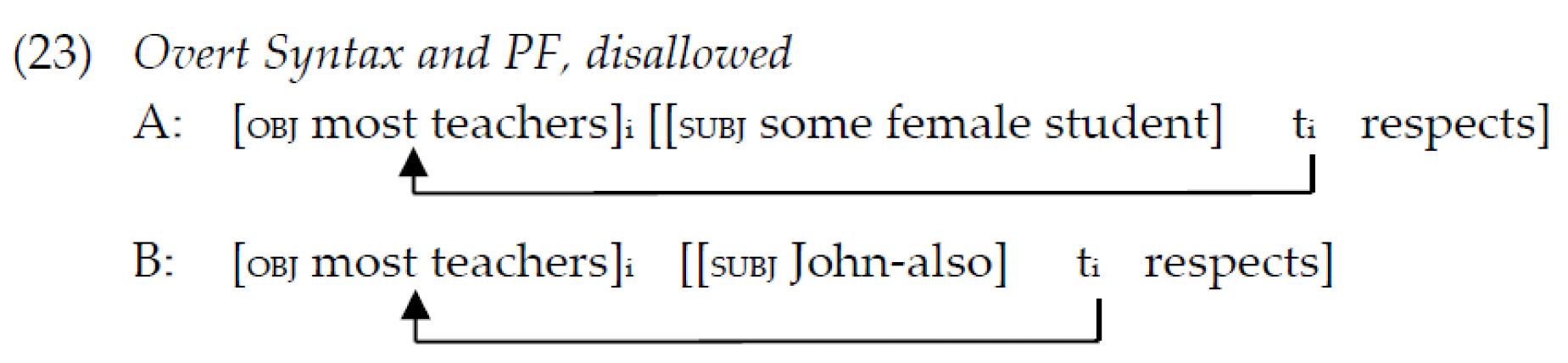

Bošković and Takahashi (1998) propose a feature-checking analysis of scrambling, according to which the scrambled object is base-generated in its surface position. At LF, it can undergo reconstruction to check its θ-feature, or remain in the scrambled position if reanalysis permits θ-feature checking there. Under this view, scrambling is not considered an optional operation and thus is not subject to Scope Economy, which is assumed to constrain only optional operations. As Park (2003) points out, this analysis allows the phonologically reduced scrambled object in (28B), repeated as (34B), to be reconstructed at LF to check its θ-feature without violating Scope Economy, as illustrated in (34B’). As a result, Parallelism is satisfied, and phonological reduction is correctly predicted to be licensed.

However, this analysis falls short of capturing the disambiguation effect in phonological reduction in (26), repeated as (35). Under this analysis, the scrambled object in both (35A) and (35B’) is base-generated in the surface (scrambled) position in overt syntax and is allowed to remain in this position at LF, which satisfies Parallelism. But this incorrectly predicts that the object-wide scope should be available for the pair (35A) and (35B’), contrary to fact; only the subject-wide scope is attested.

| (35) | A: | [taypwupwun-uy sensayngnim-ul]i enu yehaksayng-i | ti | conkyenghay. | |||||||

| most-gen | teacher-acc some female.student-nom | respect | |||||||||

| ‘Some female student respects most teachers.’ | (some > most) (*most > some) | ||||||||||

| B: | John-to | [taypwupwun-uy | sensayngnim-ul] | conkyenghay. | |||||||

| John-also | most-gen | teacher-acc | respect | ||||||||

| ‘John also respects most teachers.’ | |||||||||||

| B’: | [taypwupwun-uy | sensayngnim-ul] | John-to | conkyenghay. | |||||||

| most-gen | teacher-acc | John-also | respect | ||||||||

| lit. ‘Most teachers, John also respects.’ | |||||||||||

4.2. Miyagawa (2011)

Miyagawa (2011) provides an account of how scrambling gives rise to the scope ambiguity in Japanese. The Korean counterpart is shown in (36), repeated from (15), where scrambling renders the otherwise unambiguous sentence ambiguous. According to Miyagawa’s (2011) account, the ambiguity arises from two distinct derivations, illustrated in (37a) and (37b).

| (36) | taypwupwun-uy | sensayngnim-uli | [enu | yehaksayng-i | ti | conkyenghay]. | ||

| most-gen | teacher-acc | some | female.student-nom | respect | ||||

| lit. ‘Most teachers, some female student respects.’ | (some > most) (most > some) | |||||||

| (37) | a. | most > some | |||||||||

| [CP [TP [taypwupwun-uy | sensayngnim-ul]i [vP ti [vP | enu | yehaksayng-i | [VP ti | |||||||

| most-gen | teacher-acc | some | female.student-nom | ||||||||

| conkyenghay ]]]]] | |||||||||||

| respect | |||||||||||

| b. | some > most (will obtain after reconstruction of the scrambled QP at LF) | ||||||||||

| [CP [taypwupwun-uy | sensayngnim-ul]i [TP | enu | yehaksayng-ij | [vP ti [vP tj [VP ti | |||||||

| most-gen | teacher-acc | some | female.student-nom | ||||||||

| conkyenghay]]]]]] | |||||||||||

| respect | |||||||||||

In (37a), the object moves to Spec,TP to satisfy the EPP (Miyagawa, 2001), while the indefinite subject remains in its base position within vP. This derivation yields the object-wide scope. In contrast, the subject-wide scope arises from the derivation in (37b), where the subject moves to Spec,TP and the object moves from the outer edge of vP to CP as an optional operation, not required by the EPP requirement. Adopting a version of Fox’s (2000) Scope Economy, Miyagawa argues that the fronted object in CP must be reconstructed at LF; otherwise, it would redundantly replicate the scope relation already established at the vP phase level. This reconstruction yields the subject-wide scope.

However, Miyagawa’s account also fails to fully capture the scope interactions under discussion. The problem arises from the derivation in (37a), in which the object moves to Spec,TP to satisfy the EPP. As in Bošković and Takahashi’s (1998) analysis, this implies that the object in (35B’) may remain in the scrambled position (Spec,TP) both in overt syntax and at LF. Then, the object wide scope is predicted to be available in the examples discussed above, contrary to fact.

5. Scope and GIVENness

5.1. Where We Are

The discussion thus far has demonstrated that Takahashi’s (2008) Scope Economy-based analysis fails to account for the full range of scope interactions in Korean null argument constructions. In what follows, we propose an alternative account that does not rely on Scope Economy. In presenting our analysis, we adopt the standard view that scrambling is an optional operation (Saito, 1989).15

Note incidentally that abandoning Scope Economy removes any restrictions on the position of the null argument, contrary to the assumption in Takahashi (2008). This allows for the possibility that the disambiguation case in (3), repeated as (38), conceals two distinct derivations depending on where the null argument is. In one derivation, it is elided in its canonical position. In the other, it is elided in the scrambled position. These derivations are schematically illustrated in (39B) and (39B’), respectively (with corresponding English words).

| (38) | A: | [taypwupwun-uy | sensayngnim-ul]i | enu | yehaksayng-i | ti | conkyenghay. | ||

| most-gen | teacher-acc | some female.student-nom | respect | ||||||

| lit. ‘Most teachers, some female student respects.’ | (some > most) (*most > some) | ||||||||

| B: | John-to | e | conkyenghay. | ||||||

| John-also | respect | ||||||||

| lit. ‘John also respects.’ | |||||||||

| (39) | A: | [OBJ most teachers]i | [TP some female-student ti likes] | (some > most)(*most > some) | ||

| B: | [TP John-also [OBJ most teachers] | likes] | [Derivation 1: Overt Syntax and PF] | |||

| B’: | [OBJ most teachers]i [TP John-also ti likes] | [Derivation 2: Overt Syntax and PF] | ||||

| (40) | B’: | [OBJ most teachers]i [TP John-also ti likes] | [LF of Derivation 2] |

One key question at this point is how to correctly rule out the unavailable object-wide scope (most > some), when Derivation 2 is sent to LF, as illustrated in (40B’). As discussed in Section 3.2, the same question arises with the corresponding phonological reduction example in (26), whose derivations are schematically represented in (41).

| (41) | A: | [OBJ most teachers]i [TP some female-student ti likes] | (some > most) (*most > some) | ||

| B: | [TP John-also [OBJ most teachers] likes | [Derivation 1: Overt Syntax, PF and LF] | |||

| B’: | [OBJ most teachers]i [TP John-also | ti likes] | [Derivation 2: Overt Syntax, PF and LF] | ||

In what follows, building on Schwarzschild’s (1999) theory of focus and in the spirit of Tomioka (1997), we provide a unified account of the relevant scope phenomena. In the next section, we first introduce the core components of Schwarzschild (1999).

5.2. Schwarzschild (1999)

Schwarzschild’s (1999) theory of focus aims to characterize the relationship between accent placement and discourse through independent constraints operating at the interface between syntax and semantics. To capture the relationship, Schwarzschild proposes the GIVENness constraint in (42).

| (42) | GIVENness (Schwarzschild, 1999, p. 155) |

| If a constituent is not F-marked, it must be GIVEN. |

The notion of GIVEN is defined in (43), and the Existential F-Closure of U is defined in (44).

| (43) | Definition of GIVEN (Schwarzschild, 1999, p. 151) | |

| An utterance U counts as GIVEN iff it has a salient antecedent A and: | ||

| a. | if U is type e, then A and U corefer; | |

| b. | otherwise: modulo ∃-type shifting, A entails the Existential F-Closure of U. | |

| (44) | Existential F-Closure of U =def the result of replacing F-marked phrases in U with variables and existentially closing the result, modulo existential-type-shifting (Schwarzschild, 1999, p. 150). | |

Let us now consider how the GIVENness constraint applies in the sample examples in (45).

| (45) | A: | John ate a green apple. |

| B: | No, he ate a RED apple. |

Accenting in (45B) results in the following F(ocus)-marking.

| (46) | No, [TP he [VP ate [NP a [AP [RED]F apple]]]] |

First, at the level of individual words, the GIVENness constraint applies straightforwardly. For example, the verb ate in (45B) is not accented and thus cannot be F-marked. According to (42), this implies that it must be GIVEN. As defined in (43), this is indeed GIVEN since ate occurs in the antecedent (45A), and the relevant entailment relation holds, as shown in (47).

| (47) | ∃x∃y[ate(x)(y)] entails ∃x∃y[ate(x)(y)] |

As shown in (47), the type of ate in (45A) and (45B) is shifted to the propositional type by existentially binding unfilled arguments. Schwarzschild refers to this process as Existential(∃)-type shifting. This ∃-type shifting is necessary, as entailment is defined between propositions rather than between unsaturated predicates.

The F-marking on a prenominal adjective such as red in (46) cannot project any higher (Cinque, 1993; Selkirk, 1996; Truckenbrodt, 1995). The problem, then, is the constituents which contain the F-marked AP but are themselves non-F-marked constituents (i.e., NP, VP and TP). In order to render these constituents GIVEN, Schwarzschild incorporates Existential F-Closure of U in (44) as part of the definition of GIVENness in (43). This process allows an F-marked constituent to be replaced by an existentially bound variable of the same type (referred to as F-variables) in the computation of GIVENness. The Existential(∃) F-Closures of the relevant constituents are presented in (48).

| (48) | a. | [NP a [AP RED]F apple]] : ∃P∃x[P(x) & apple(x)] |

| b. | [VP ate [NP a [AP RED]F apple]] : ∃P∃y∃x[P(x) & apple(x) & ate(x)(y)] | |

| c. | [TP he [VP ate [NP a [AP RED]F apple]]] : ∃P∃x[P(x) & apple(x) & ate(x)(John)] |

All these ∃-F-closures are entailed by the corresponding ∃-Type-Shifted constituents in (45A), as shown in (49). Consequently, all the non-F-marked phrases are correctly considered GIVEN.

| (49) | a. | The ∃-Type-Shifted NP [NP a green apple] is ∃x[green(x) & apple(x)] and entails |

| the ∃-F-Closure of NP: ∃P∃x[P(x) & apple(x)]. | ||

| b. | The ∃-Type-Shifted VP [VP ate a green apple] is ∃y∃x[green(x) & apple(x) & | |

| ate(x)(y)] and entails the ∃-F-Closure of VP: ∃P∃y∃x[P(x) & apple(x) & ate(x)(y)]. | ||

| c. | The denotation of TP is ∃x[green(x) & apple(x) & ate(x)(John)] and entails | |

| the ∃-F-Closure of TP: ∃P∃x[P(x) & apple(x) & ate(x)(John)]. |

With this background in mind, we now turn to the next section and demonstrate that the GIVENness constraint accounts for the scope interpretations in Korean null argument constructions.

5.3. GIVENness and Scope Interpretation in Null Argument Constructions

5.3.1. Disambiguation Effect

Let us first consider the disambiguation effect. The relevant data exhibiting this effect with phonological reduction in (26) are repeated as (50A)–(50B’), and the example with a null argument in (20B) is repeated as (50B”), for convenience. (They are now represented with appropriate F-marking.) Recall that while (50A) is ambiguous in isolation, it becomes disambiguated, when followed by (50B), (50B’), or (50B”), yielding only the indefinite subject-wide scope. In this section, we demonstrate how the GIVENness constraint, in conjunction with Parallelism, accounts for the disambiguation effect without assuming Scope Economy.

| (50) | A: | [taypwupwun-uy sensayngnim-ul]i | enu | yehaksayng-i | ti | conkyenghay. | ||||||||

| most-gen teacher-acc | some female.student-nom respect | |||||||||||||

| lit. ‘Most teachers, some female student respects.’ | (some > most) (*most > some) | |||||||||||||

| B: | [John]F-to | [taypwupwun-uy | sensayngnim-ul] | conkyenghay. | ||||||||||

| John-also | most-gen | teacher-acc | respect | |||||||||||

| ‘John also respects most teachers.’ | ||||||||||||||

| B’: | [taypwupwun-uy | sensayngnim-ul]i | [John]F -to | ti | conkyenghay. | |||||||||

| most-gen | teacher-acc | John -also | respect | |||||||||||

| lit. ‘Most teachers, John also respects.’ | ||||||||||||||

| B”: | [John]F-to | e | conkyenghay. | |||||||||||

| John-also | respect | |||||||||||||

| lit. ‘John also respects.’ | ||||||||||||||

- Deriving the Subject-Wide Scope (‘Some > Most’)

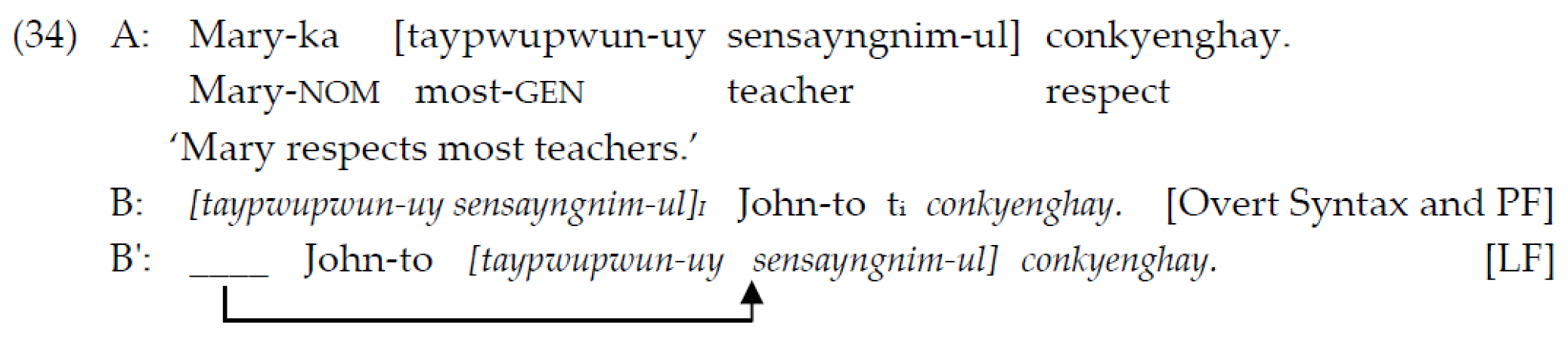

The indefinite subject-wide scope interpretation is the only available interpretation in (50). Let us first consider how this interpretation arises in the pair (50A) and (50B’). It obtains when the scrambled object in both sentences is reconstructed in parallel fashion, satisfying Parallelism, as illustrated in (51) (with corresponding English words). Crucially, reconstruction of the scrambled object QP across the non-quantified subject is permitted since Scope Economy is not operative.16

The LFs in (51) satisfy the GIVENness constraint. The non-F-marked constituents that must be evaluated for GIVENness in (51b) are the object NP, the lower vP and the higher vP. With ∃-Type-Shifting, their denotations are shown in (52a)–(52c), respectively. Given that each is identical to the corresponding ∃-Type-Shifted constituent in the antecedent in (51a), as shown in (51a)–(51c), the entailment relation holds between them (via logical equivalence), satisfying the GIVENness constraint.17 The TP in (51b) contains the F-marked subject and thus must also be checked for GIVENness with ∃-F-Closure, as shown in (52d). The ∃-F-Closure of TP in (52d) is entailed by the ∃-Type-Shifted higher vP in (53c), satisfying GIVENness. Consequently, the indefinite subject-wide scope obtains.

| (52) | The constituents that must be evaluated for GIVENness in (51b) | |

| a. | The ∃-Type-Shifted object NP (= [OBJ most teachers]): ∃P[|{x| teacher(x) & P(x)}| | |

| > |{x| teacher(x) & ¬P(x)}|] | ||

| b. | The ∃-Type-Shifted lower vP (= [vP t1 respect t2]): ∃y∃x[respect (x)(y)] | |

| c. | The ∃-Type-Shifted higher vP (= [vP [OBJ most teachers] 2 [vP t1 respect t2]]): ∃y[|{x| | |

| teacher(x) & respect(x)(y)}| > |{x| teacher(x) & ¬respect(x)(y)}|]18 | ||

| d. | The ∃-F-Closure of TP (= [TP [SUBJ John]F-also 1 [vP [OBJ most teachers] 2 [vP t1 respect | |

| t2]]]) : ∃y[|{x| teacher(x) & respect(x)(y)}| > |{x| teacher(x) & ¬respect(x)(y)}|] | ||

| (53) | The ∃-Type-Shifted constituents in (51a) | |

| a. | The ∃-Type-Shifted object NP (= [OBJ most teachers]): ∃P[|{x| teacher(x) & P(x)}| | |

| > |{x| teacher(x) & ¬P(x)}|] entails (52a). | ||

| b. | The ∃-Type-Shifted lower vP: ∃y∃x[respect (x)(y)] entails (52b). | |

| c. | The ∃-Type-Shifted higher vP: ∃y[|{x| teacher(x) & respect(x)(y)}| > |{x| | |

| teacher(x) & ¬respect(x)(y)}|] entails (52c) and (52d). | ||

The same account applies to the pair (50A) and (50B). When the scrambled object in (50A) is reconstructed and the object in (50B) remains in situ at LF, the resulting LFs are identical to those in (51). Accordingly, the GIVENness constraint is satisfied, and the indefinite subject-wide scope is derived.

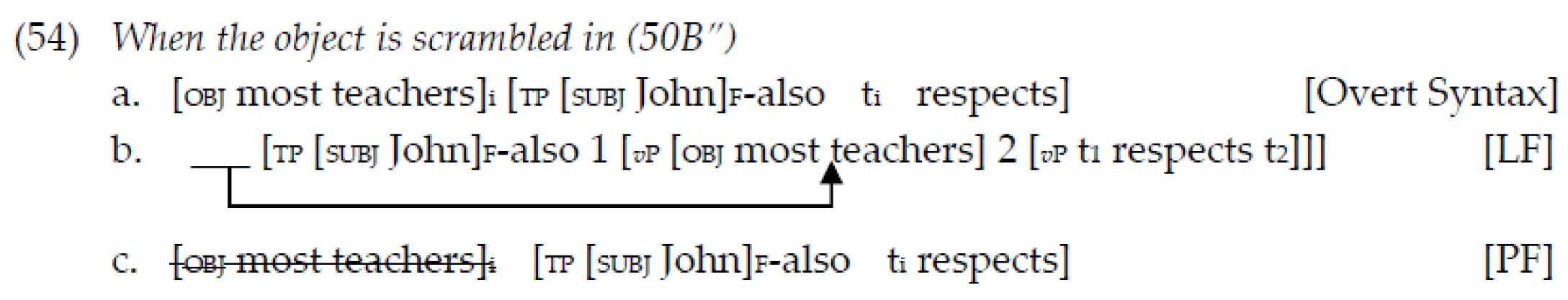

Let us now consider how the indefinite subject-wide scope arises for the pair (50A) and (50B”). In order to derive this interpretation, the scrambled object in the antecedent in (50A) must be reconstructed at LF, as shown in (51a) above. Depending on the position of the null argument in (50B”), there are two possibilities to derive (50B”) and they are both allowed under the current analysis. First, when it appears in its canonical object position in overt syntax, it remains in this position at LF,19 satisfying Parallelism. The resulting LFs are identical to those in (51), which satisfy the GIVENness constraint and allow the indefinite subject-wide scope. When the object is deleted at PF, (50B”) is derived. The same LFs are also derived when the object in (50A) is scrambled in overt syntax.20 This is because, in order to derive the subject-wide scope, the scrambled object in (50B”) must be reconstructed, resulting in the same LFs as those in (51). The overt and LF representations of this derivation are shown in (54a) and (54b), respectively. Under the standard assumption that non-focused, given elements may be either elided or phonologically reduced (Rooth, 1992; Tomioka, 1997; Fox, 2000),21 the scrambled object in (54c) is eligible for ellipsis at PF, deriving (50B”).

- Ruling Out the Object-Wide Scope (‘Most > Some’)

Let us now consider how the GIVENness constraint correctly rules out the object-wide scope (i.e., most > some) for the pair (50A) and (50B’). Assuming Parallelism, the LFs that would incorrectly derive the object wide scope for both sentences are shown in (55).

| (55) | a. | [TP2 [OBJ most teachers] 2 [TP1 [SUBJ some female-student]1 [vP t1 respect t2 ]]] | |

| [LF of 50A)] | |||

| b. | [TP2 [OBJ most teachers] 2 [TP1 [SUBJ [John]F-also 1 [vP t1 respect t2]]] | [LF of (50B’)] | |

What is relevant for our purposes is to show that at least one constituent in (55b) is not GIVEN. This is confirmed by the fact that the ∃-F-Closure of TP2 in (55b) is not entailed by any of the constituents in (55a), as shown in (56) and (57) below. As a result, the LFs in (55) are ruled out by the GIVENness constraint, thereby correctly accounting for the unavailability of the object-wide scope interpretation.

| (56) | The ∃-F-Closure of TP2 in (55b) |

| ∃y[|{x| teacher(x) & respect(x)(y)}| > |{x| teacher(x) & ¬respect(x)(y)}|] |

| (57) | The ∃-Type-Shifted constituents and the denotation of TP2 in (55a) | |

| a. | The ∃-Type-Shifted subject NP (= [SUBJ some female-student]): ∃y[female(y) & | |

| student(y)] | ||

| b. | The ∃-Type-Shifted object NP (= [OBJ most teachers]): ∃P[|{x| teacher(x) & P(x)}| | |

| > |{x| teacher(x) & ¬P(x)}|] | ||

| c. | The ∃-Type-Shifted vP (= [vP t1 respect t2]): ∃y∃x[respect (x)(y)] | |

| d. | The ∃-Type-Shifted TP1 (= [TP1 [some female-student]1 [vP t1 respect t2]]): | |

| ∃y∃x[female(y) & student(y) & respect (x)(y)] | ||

| e. | The denotation of TP2 (= [TP2 [most teachers] 2 [TP1 [some female-student]1 [vP t1 respect | |

| t2]]]): |{x|teacher(x) & ∃y[female(y) & student(y) & respects(x)(y)]}| > | ||

| |{x|teacher(x) & ¬∃y[female(y) & student(y) & respects(x)(y)]}| | ||

This account also extends to (50B). To derive the unavailable object-wide scope in this case, the scrambled object in (50A) should remain in the scrambled position throughout the derivation, and scrambling of the object in (50B) would have to occur at LF, due to Parallelism. However, as discussed in Section 3.1, such scrambling is independently prohibited in Korean and Japanese, since these languages do not allow QR or LF-scrambling.

Under the proposed analysis, the object-wide scope is not permitted in the null object construction in (50B”), either. To derive the object wide scope, the object in (50B”) should be scrambled in overt syntax (prior to ellipsis at PF) and is sent to LF as such. This would result in the same LFs in (55). However, as discussed above, these LFs fail to satisfy the GIVENness constraint and thus are ruled out.

5.3.2. Two-Way Parallel Interpretations

In this section, we show that the two-way parallel interpretations can also be straightforwardly accounted for with the GIVENness constraint and Parallelism. The relevant examples are reproduced below as (58), with appropriate F-marking and phonological reduction.22 Recall that only the two-way parallel interpretations are available for the pair (58A) and (58B) and for the pair (58A) and (58B’).

| (58) | A: | [taypwupwun-uy | sensayngnim-ul]i | enu | yehaksayng-i | ti | conkyenghay. | ||||||||

| most-gen | teacher-acc | some | female.student-nom | respect | |||||||||||

| lit. ‘Most teachers, some female student respects.’ | |||||||||||||||

| B: | enu | [nam]F-haksayng-to | e | conkyenghay. | (some > most) (most > some) | ||||||||||

| some | male.student-also | respect | |||||||||||||

| lit. ‘Some male student also respects.’ | |||||||||||||||

| B’: | [taypwupwun-uy | sensayngnim-ul]i | enu | [nam]F-haksayng-to | ti | conkyenghay. | |||||||||

| most-gen | teacher-acc | some | male.student-also | respect | |||||||||||

| lit. ‘Most teachers, some male student also respects.’ | |||||||||||||||

- Subject-Wide Scope (‘Some > Most’)

When following (58A), the null argument construction in (58B) and phonological reduction constructions in (58B’) permit the parallel subject-wide scope interpretation (i.e., some > most). This is because they both allow parallel LF configurations where the subject c-commands the object, as discussed below.

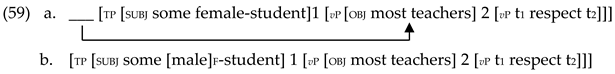

First, let us consider how the parallel subject-wide scope obtains for the pair (58A) and the null argument construction in (58B). This interpretation arises, when the scrambled object in the antecedent (58A) is reconstructed at LF, and the (null) object in (58B) occupies its canonical object position in overt syntax and at LF, thereby satisfying Parallelism. This yields the LFs in (59). (Note here that when the object occupies the scrambled position in overt syntax (prior to ellipsis at PF) it must be reconstructed at LF.)

The LFs in (59) satisfy the GIVENness constraint. In (59b), the object NP, the higher vP and the lower vP are all considered GIVEN, since each has a corresponding identical counterpart in the antecedent. The remaining two constituents that must be evaluated for GIVENness are the subject NP and TP in (59b). These are also GIVEN since their ∃-F-Closures are entailed by the corresponding constituents in the antecedent in (59a), as shown in (60).

| (60) | a. | The ∃-F-Closure of the subject NP (= [some [male]F-student]) in (59b) is |

| ∃P∃y[P(y) & student(y)] and is entailed by the ∃-Type-Shifted subject NP | ||

| (= [some female-student]) in (59a): ∃y[female(y) & student(y)]. | ||

| b. | The ∃-F-Closure of TP in (59b) is ∃P∃y[P(y) & student (y) & [|{x|teacher(x) & | |

| respect(x)(y)}| > |{x|teacher(x) & ¬respect(x)(y)}|]] is entailed by the denotation | ||

| of TP in (59a): ∃y[female(y) & student(y) & [|{x|teacher(x) & respect(x)(y)}| > | ||

| |{x|teacher(x) & ¬respect(x)(y)}|]]. |

When the scrambled object is phonologically reduced, as in (58B’), the same parallel subject-wide scope is observed. This scope interpretation arises when the scrambled object in (58A) and (58B’’) is reconstructed in parallel at LF, yielding the same LFs as those in (59).23

- Object-Wide Scope (‘Most > Some’)

The parallel object-wide scope interpretation for the pair (58A) and (58B) obtains when the object in the former remains in the scrambled position throughout the derivation, and the object in the latter likewise undergoes scrambling in overt syntax (prior to ellipsis) and remains in this position at LF. The resulting LFs are presented in (61).

| (61) | a. | [TP2 [OBJ most teachers] 2 [TP1 [SUBJ some female-student]1 [vP t1 respect t2 ]]] |

| b. | [TP2 [OBJ most teachers] 2 [TP1 [SUBJ some [male]F-student]1 [vP t1 respect t2 ]]] |

The LFs in (61) not only satisfy Parallelism but also obey the GIVENness constraint. In (61b), the object QP is GIVEN, since it has a corresponding identical counterpart in the antecedent in (61a). The remaining ∃-F-Closures of the constituents in (61b) that must be evaluated for GIVENness are presented below.

| (62) | a. | The ∃-F-Closure of the subject NP: ∃P∃y [P(y) & student(y)] |

| b. | The ∃-F-Closure of TP1: ∃P∃y∃x[P(y) & student(y) & respect(x)(y)] | |

| c. | The ∃-F-Closure of TP2: |{x|teacher(x) & ∃P∃y[P(y) & student(y) & | |

| respect(x)(y)]}| > |{x|teacher(x) & ¬∃P∃y[P(y) & student(y) & respect(x)(y)]}| |

As shown in (63), each ∃-F-Closure in (62) is entailed by the corresponding constituent in the antecedent in (61a). That is, (62a)–(62c) are entailed by (63a)–(63c), respectively. Consequently, the GIVENness constraint is satisfied, licensing the parallel object-wide scope in both sentences.

| (63) | a. | The ∃-Type-Shifted subject NP in (61a): ∃y[female(y) & student(y)] |

| b. | The ∃-Type-Shifted TP1 in (61a): ∃y∃x[female(y) & student(y) & respect(x)(y)] | |

| c. | The denotation of TP2 in (61a): |{x|teacher(x) & ∃y[female(y) & student(y) & | |

| respect(x)(y)]}| > |{x|teacher(x) & ¬∃y[female(y) & student(y) & respect(x)(y)]}| |

The same parallel object-wide scope is permitted for the pair (58A) and (58B’). This interpretation obtains when the object in both sentences remain in the scrambled position at LF, resulting in the same LFs as in (61).

5.3.3. Scope Economy in English Revisited

The proposed analysis readily extends to English. The relevant examples are repeated in (64) with appropriate F-marking. Recall that Fox (2000) argues that Scope Economy prohibits QR of the object QP over the non-quantified NP Mary in (64b). Parallelism then ensures that the same restriction applies to the antecedent, yielding only the subject-wide scope.

| (64) | a. | A boy admires every teacher. [A [girl]F] does | |

| (∃ > ∀) (∀ > ∃) | |||

| b. | A boy admires every teacher. [Mary]F does admire every teacher, too. (∃ > ∀) (*∀ > ∃) | ||

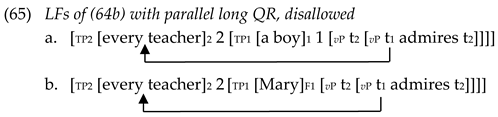

Given the discussion of Korean null object constructions that exhibit the same scope patterns as those in (64), we argue that the proposed GIVENness-based account, in conjunction with Parallelism, can also straightforwardly capture the scope patterns in (64), without recourse to Scope Economy. In particular, without Scope Economy, the object QP in the elliptical clause in (64b) is allowed to undergo QR over the non-quantified subject at LF, and Parallelism ensures that the parallel QR also takes place in the antecedent clause. The resulting LFs are shown in (65). If these were permitted, the object-wide scope interpretation would incorrectly be predicted to be available.

However, the LFs in (65) can be correctly filtered out by the GIVENness constraint (just as in the case of the Korean null object and phonological reduction constructions in (50)). Among the constituents in (65b), the ∃-F-Closure of TP2 is provided in (66) and is not entailed by any constituents in (65a), as shown in (67). Since the GIVENness constraint is not satisfied, the LFs in (65) are not allowed. (As the reader can verify, the subject-wide scope interpretation obtains when the object QP in both clauses undergoes short QR below the subject.)

| (66) | The ∃-F-Closure of TP2 in (65b): ∃y∀x [teacher(x) → admire(x)(y)] |

| (67) | Constituents of (65a) | ||

| a. | The ∃-Type-Shifted subject NP is ∃P∃x[boy(x) & P(x)] and does not entail (66). | ||

| b. | The ∃-Type-Shifted object NP is ∃P∀x[teacher(x)→P(x)] and does not entail (66). | ||

| c. | The ∃-Type-Shifted higher/lower vP is ∃y∃x [admire(x)(y)] and does not entail (66). | ||

| d. | The ∃-Type-Shifted TP1 is ∃x∃y[boy(y) & admire(x)(y)] and does not entail (66). | ||

| e. | The denotation of TP2 is ∀x[teacher(x) → ∃y[boy(y) & admire(x)(y)]] and does | ||

| not entail (66). | |||

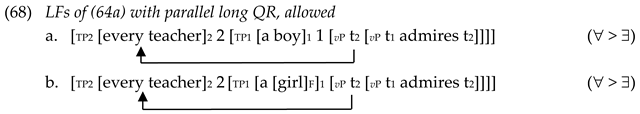

As with the Korean null argument and phonological reduction constructions in (58), the sentences in (64a) allow only two-way parallel interpretations. The same GIVENness-based account proposed for (58) extends to (64a) without appealing to Scope Economy. As with Korean data, Parallelism also plays a crucial role. For instance, when the object QP in the antecedent clause undergoes long QR, the one in the elliptical clause must also undergo the same long QR, as illustrated in (68).

All the constituents in (68b) are entailed by some of the ∃-Type-Shifted constituents in (68a). For instance, the ∃-F-Closures of TP1 and TP2 are properly entailed, as shown in (69). Since the GIVENness constraint is satisfied in (68), the object-wide scope interpretation is available for both clauses.24

| (69) | a. | The ∃-F-Closures of TP1 in (68b) is ∃P∃y∃x[P(y) & admire(x)(y)] and is entailed |

| by the ∃-Type-Shifted lower TP1 in (68a): ∃y∃x[boy(y) & admire(x)(y)]. | ||

| b. | The ∃-F-Closures of TP2 in (68b) is ∃P∀x[teacher(x) → ∃y[P(y) & admire(x)(y)]] | |

| and is entailed by the denotation of TP2 in (68a): ∀x[teacher(x) → ∃y[boy(y) & | ||

| admire(x)(y)]]. |

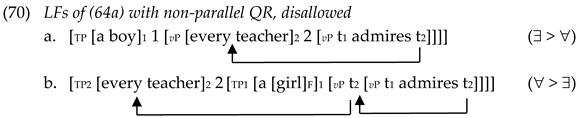

Without Parallelism, however, (64a) would incorrectly be predicted to allow non-parallel interpretations. Suppose, for instance, that while the object QP in the antecedent clause does not undergo long QR over the subject, the one in the elliptical clause does, as illustrated in (70).

The ∃-F-Closures of TP1 in (70b) (= ∃P∃y∃x[P(y) & admire(x)(y)]) is entailed by the ∃-Type-Shifted lower vP in (70a) (= ∃y∃x[admire(x)(y)]). Crucially, The ∃-F-Closures of TP2 in (70b) is also entailed by the denotation of TP in (70a), as shown in (71).

| (71) | The ∃-F-Closures of TP2 in (70b) is ∃P∀x[teacher(x) → ∃y[P(y) & admire(x)(y)]] and is entailed by the denotation of TP in (70a): ∃y[boy(y) & ∀x[teacher(x) → admire(x)(y)]]. |

In other words, the denotation of TP in (70a) is that there exists some boy y such that for every teacher x, y admires x and (logically) entails the ∃-F-Closures of TP2 in (70b): for every teacher x, there is some person y with a property P such that y admires x. Thus, the LFs in (70) would satisfy the GIVENness constraint, thereby incorrectly yielding the non-parallel interpretations in (64a): subject-wide scope for the antecedent clause and object-wide scope for the elliptical clause. However, these non-parallel interpretations can be correctly ruled out by the application of Parallelism, which disallows the LFs in (70).25

In this section, we have shown that the proposed analysis can account for the scope interactions in English. It offers greater explanatory power than the Scope Economy-based account, since it provides a uniform account of scope interactions in both English and Korean.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we have shown that scope interactions in Korean null argument constructions cannot be fully accounted for by Takahashi’s (2008) Scope Economy-based analysis. To evaluate the validity of Scope Economy, we employed phonological reduction as a diagnostic for scope interpretations and demonstrated that the same scope interpretation persists even when the null argument is scrambled over a non-quantified subject, contrary to predictions of the Scope Economy-based account. We further observed that this problem is not confined to null argument constructions but also arises in fragments. These findings lead to the conclusion that scope interactions in Korean null argument constructions are not constrained by Scope Economy. Dispensing with Scope Economy, we have argued that Schwarzschild’s (1999) GIVENness constraint, in conjunction with Parallelism, offers a principled account of the observed scope interactions in Korean.

We have also shown that the proposed account can readily be extended to scope patterns observed in English. Since it accounts for scope interactions in both Korean and English without recourse to Scope Economy, we conclude that Scope Economy can—and should—be dispensed with. The view that Scope Economy is not necessary for accounting for scope patterns in English has been advanced by Tomioka (1997) and Rooth (2005). The present study strengthens this line of argument from a cross-linguistic perspective, offering a unified and empirically grounded alternative to Scope Economy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.-S.P. (first author) and S.-R.O. (corresponding author); methodology B.-S.P.; validation S.-R.O.; formal analysis, B.-S.P. and S.-R.O.; investigation, B.-S.P. and S.-R.O.; resources, S.-R.O.; data curation B.-S.P.; writing−original draft preparation, B.-S.P.; writing−review and editing, S.-R.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to the Languages editor and two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and to the guest editors of this special issue for their kind invitation and help. We would also like to thank the audience of the Workshop on Quantifier Scope (IKER, the Basque Country, 2014), where an earlier version of this paper was presented, especially Urtzi Etxeberria, Anastasia Giannakidou and Jeffrey Lidz, for their valuable discussions and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACC | question marker |

| GEN | question marker |

| PAST | question marker |

| DEC | question marker |

| Q | question marker |

| CL | classifier |

| LF | Logical Form |

| PF | Phonetic Form |

Notes

| 1 | In this paper, the null object is represented using the symbol e. As will become clearer below, however, this symbol is not intended to indicate the exact syntactic position of the null object. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | In this paper, we focus on Korean null argument constructions, which exhibit the same scope patterns as their Japanese counterparts. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | Fox (2000) derives Parallelism in (7) as a consequence of Rooth’s (1992) Alternative Semantics of Focus. In addition to (7), which he refers to as Direct Parallelism, Fox also proposes Indirect Parallelism to account for phonologically reduced expressions that cannot undergo ellipsis (see fn. 21 for related discussion). However, considerations of Indirect Parallelism are immaterial to the discussion in this paper. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | Small italics are used to indicate phonological reduction. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | Fox (2000) takes extraposition to be an optional overt operation subject to Word Order Economy. As illustrated by the contrast between (ia) and (ib), the obviation of Condition C effect arises only when extraposition applies (see Taraldsen, 1981). Fox suggests that the Condition C effect in (ic) indicates that extraposition has failed to apply, in accordance with Word Order Economy.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | See also Bobaljik and Wurmbrand (2012) for related discussion. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7 | In defense of the pro approach to null arguments, Hoji (1998) argues that pro can stand for a bare indefinite argument. Under this approach, the null argument is interpreted as the indefinite NP sensayngnim-ul ‘teacher’ and derives the relevant quantificational interpretations via pragmatic mechanisms (see also H.-D. Ahn & Cho, 2012). However, as noted by Saito (2007) and Park and Bae (2012), this approach faces problems in negative environments as in (i). The sentence in (iB) conveys the interpretation that Max didn’t read two books, a reading that is expected by the ellipsis approach. This interpretation, however, cannot be accounted for if the null argument is analyzed as pro construed as a bare indefinite (see also Park & Oh, 2013; Fujiwara, 2022, for related discussion). As shown in (iB’), when the corresponding overt indefinite chayk-ul ‘book-Acc’ is used in place of the null object, the sentence yields only the reading that Max didn’t read any books, an interpretation that is unavailable in (iB). Throughout this paper, we assume the ellipsis approach, at least for cases in which the null argument is quantificational.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 | In (16B), the null object can also occupy the scrambled position. However, as discussed below, Parallelism ensures that it is reconstructed at LF, yielding the same subject-wide scope (see fn. 23 for related discussion). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9 | The same scope patterns are observed when the universal QP motun sensayngnim ‘every teacher’ is used in place of taypwupwun-uy sensayngnim ‘most teachers’. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10 | Takahashi (2008) appears to assume that scrambling of the object in (23B), followed by ellipsis of it, violates Word Order Economy as well, since it is ultimately string-vacuous once ellipsis takes place at PF. This assumption, however, would give rise to a more general problem. If (23B) is ruled out due to a violation of Word Order Economy, then by the same reasoning, scrambling of the object in (17B) should also violate Word Order Economy after ellipsis occurs, as illustrated in (19B). This would incorrectly predict that object-wide scope should be unavailable, contrary to fact. Importantly, the issue arises independently of Scope Economy, since a violation of Word Order Economy alone should suffice to block the derivation. While we acknowledge this as a potential issue, our discussion will center on Scope Economy, unless otherwise noted. A reviewer raises the possibility that scrambling of the elided object as in (23B) might give rise to other semantic effects such as potential differences in information structure, which could allow the derivation in (23B). However, as shown with phonological reduction in the next section, under the current context, scrambling of this kind does not appear to yield any such semantic effects. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11 | All six of our informants confirmed this judgement. The Japanese counterparts to (26) were also reported to exhibit the same patterns by two Japanese native speakers. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12 | Park (2005, 2013) offers several arguments (such as connectivity effects) against alternative approaches to fragments in Korean, including the Direct Interpretation Approach, which maintains that fragments are not derived via ellipsis but are interpreted via pragmatic processes (Yanofsky, 1978; Morgan, 1989; Barton, 1990; Stainton, 1995, 2006; Barton & Progovac, 2005), and the cleft approach, which posits that the underlying source of fragments is a cleft structure (Shimoyama, 1995; Nishiyama et al., 1996; Fukaya & Hoji, 1999; Sohn, 2000). See also Bae and Park (2018) for further arguments based on the variability of the Clause-Mate Condition effect. Note further that as shown below, scope interpretations in fragments exhibit the same patterns as their phonological reduction and null argument counterparts. The parallel patterns can most straightforwardly be captured under the ellipsis approach to fragments. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13 | In this paper, we assume that remnant fronting in this environment can be regarded as scrambling, given that it parallels scrambling in the relevant respects: it appears to be optional, as is characteristic of scrambling, and, as shown below, it yields the same scope interpretations as scrambling in null argument constructions. Alternatively, one might assume that remnant fronting is an instance of focus movement. However, insofar as it exhibits the properties noted above, this assumption does not affect the present discussion. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 14 | Park (2003) suggests that the reconstruction of the scrambled object in (32) and (33) is allowed without violating Scope Economy, as it can be motivated by feature checking at LF, in the sense of Bošković and Takahashi (1998). However, as discussed in Section 4.1, this analysis remains insufficient to account for the relevant facts. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15 | As the reader can verify, the proposed analysis below is also compatible with Bošković and Takahashi’s (1998) approach to scrambling. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16 | We assume that the scrambled object QP is reconstructed to the outer edge of vP, allowing it to be interpreted without inducing the type-mismatch problem (see Section 2 for relevant discussion). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 17 | Likewise, at the level of individual words, the verb respect in (51b) is entailed by the identical verb in the antecedent in (51a) (with ∃-Type-Shifting), as discussed in Section 5.2. In what follows, we set aside entailment relations holding between identical constituents or elements | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 18 | This is read as: there exists a y such that the number of teachers whom y respects is greater than the number of teachers whom y does not respect (Barwise & Cooper, 1981; Chierchia & McConnell-Ginet, 1990; Heim & Kratzer, 1998). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 19 | To be precise, the object QP raises to the outer edge of vP at LF, due to type considerations (fn. 16). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 20 | Fujiwara (2022) argues that argument ellipsis can only take place in a fronted position, i.e., CP. Under this analysis, the elided object QP in (50B”) always occupies this position. Fujiwara’s analysis is compatible with the proposed analysis in this paper, as long as the fronted object QP in (50B”) is allowed to be reconstructed at LF, as in (54b) (due to the considerations of Parallelism). In contrast, Fujiwara’s analysis may not be compatible with the Scope-Economy based account, which prohibits scrambling of an elided object QP across a non-quantified NP. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 21 | It should be noted that not all instances of phonological reduction are eligible for ellipsis (Rooth, 1992; Tancredi, 1992; Wold, 1995). For example, the VP/vP in (ia) may undergo phonological reduction but cannot be elided. Given that no entailment relation holds, we can assume that implicational bridging (Rooth, 1992), as incorporated into Schwarzschild’s theory, may also serve as a licensing condition for phonological reduction. The basic idea is that if someone is called an idiot, it implicates that the person is insulted but, not vice versa, as illustrated in (ib) (see Tomioka, 1997, for detailed discussion). What, then, prevents VP-ellipsis in (ia)? One possibility is that ellipsis is subject to additional licensing conditions, such as LF-identity (Fiengo & May, 1994) or mutual entailment between the antecedent and the elliptical VP (Merchant, 2001). Such issues do not arise for argument ellipsis discussed in this paper, since the elided and antecedent arguments are (literally) identical.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 22 | We assume that contrasting with ye ‘female’ in the antecedent, the modifier nam ‘male’ is F-marked (Selkirk, 1996). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 23 | Thus far, we have assumed Parallelism in deriving the appropriate scope interpretation (see Fox & Lasnik, 2003; Hartman, 2011, among others, for approaches that treat Parallelism as an independent condition). Parallelism also straightforwardly accounts for the scope interpretation in an example like (i). The pair (iA) and (iB) allows only the subject-wide scope interpretation. This interpretation is correctly predicted by Parallelism, since it demands that the scrambled object in (iB) be reconstructed at LF. The resulting LFs are identical to those in (59), which yield only the subject-wide scope interpretation.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 24 | The higher and lower vPs and the object NP in (68b) are entailed (via ∃-Type-Shifting) by the corresponding identical constituents in the antecedent in (68a). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||