The Effects of Self-Access Web-Based Pragmatic Instruction and L2 Proficiency on EFL Students’ Email Request Production and Confidence

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Email Requests to Faculty

2.2. Effects of Pragmatic Instruction on the Production of Email Requests to Faculty in English

2.3. Self-Access Web-Based Pragmatic Instruction

3. The Present Study

- RQ 1: Does self-access web-based pragmatic instruction work as a means to improve EFL learners’ ability to write appropriate email requests to faculty in English? If so, which aspects of email requests are affected by instruction?

- RQ 2: Do effects of self-access web-based pragmatic instruction vary according to learners’ L2 proficiency level? If so, which aspects of email requests are affected by proficiency?

- RQ 3: Do self-access web-based pragmatic instruction and L2 proficiency level have an effect on EFL learners’ confidence in the appropriateness of their email requests to faculty?

4. Methodology

4.1. Participants

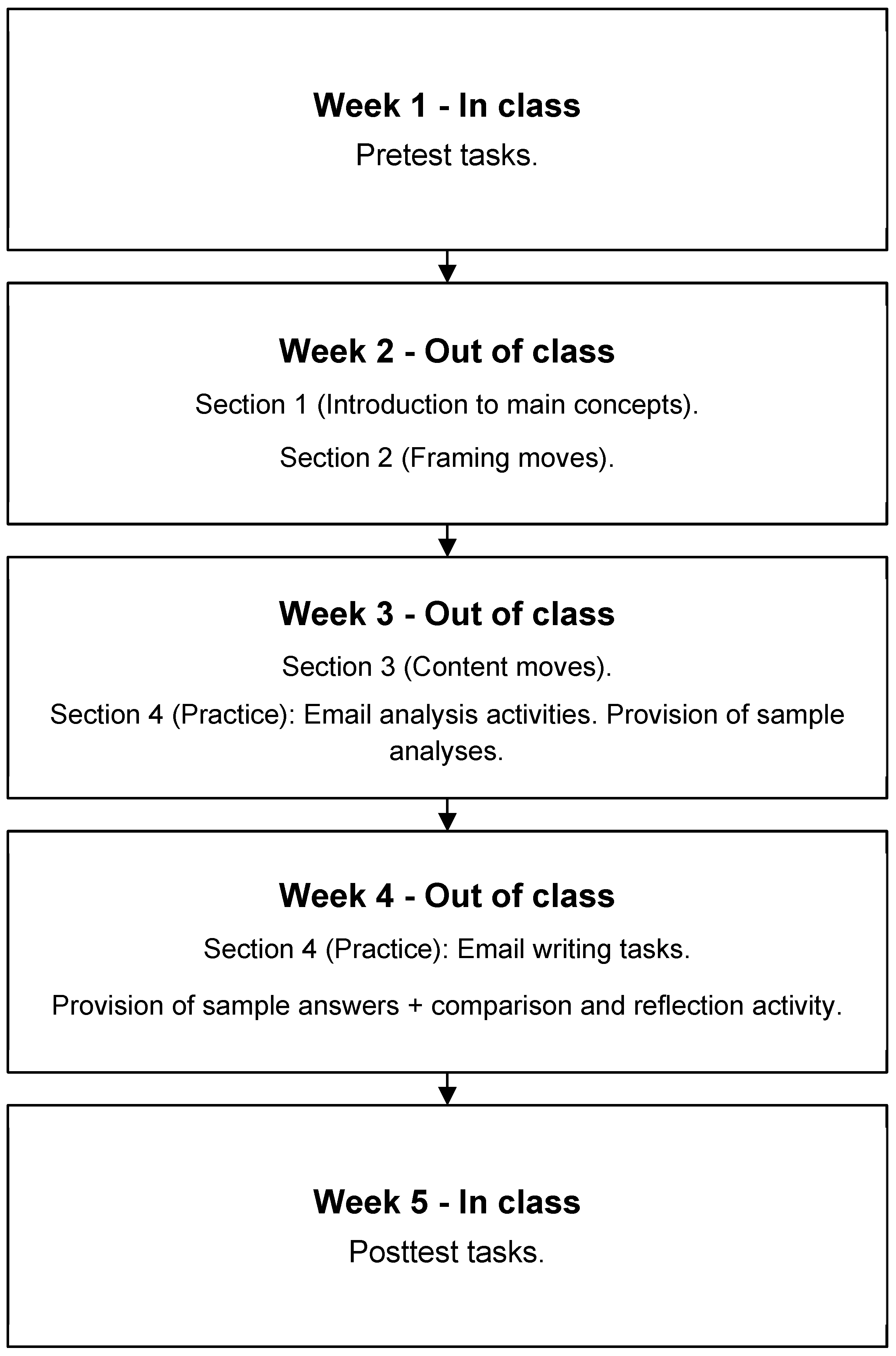

4.2. Self-Access Instruction

4.3. Data Collection

- Readability: Effort required on the part of the reader to understand the email purpose and ideas.

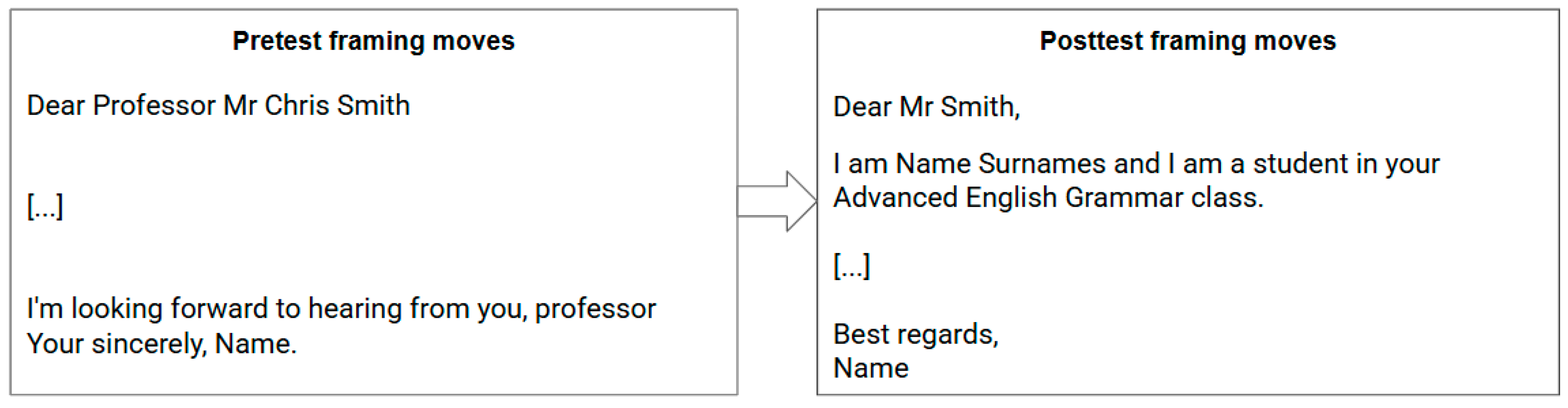

- Organization: Presence or absence of framing moves and of a general structure that facilitates identification of key information.

- Request appropriateness: Directness of the request and use of internal mitigators (both syntactic and lexical–phrasal) in relation to the given communicative situation.

- Use of content moves: Relevance and adequacy of the content moves included in the email according to the specific communicative situation.

- Overall sociopragmatic awareness: Appropriateness of register in the communicative situation (student–professor relationship, rank of imposition), evidenced in the level of formality, politeness, and word choices.

5. Results and Discussion

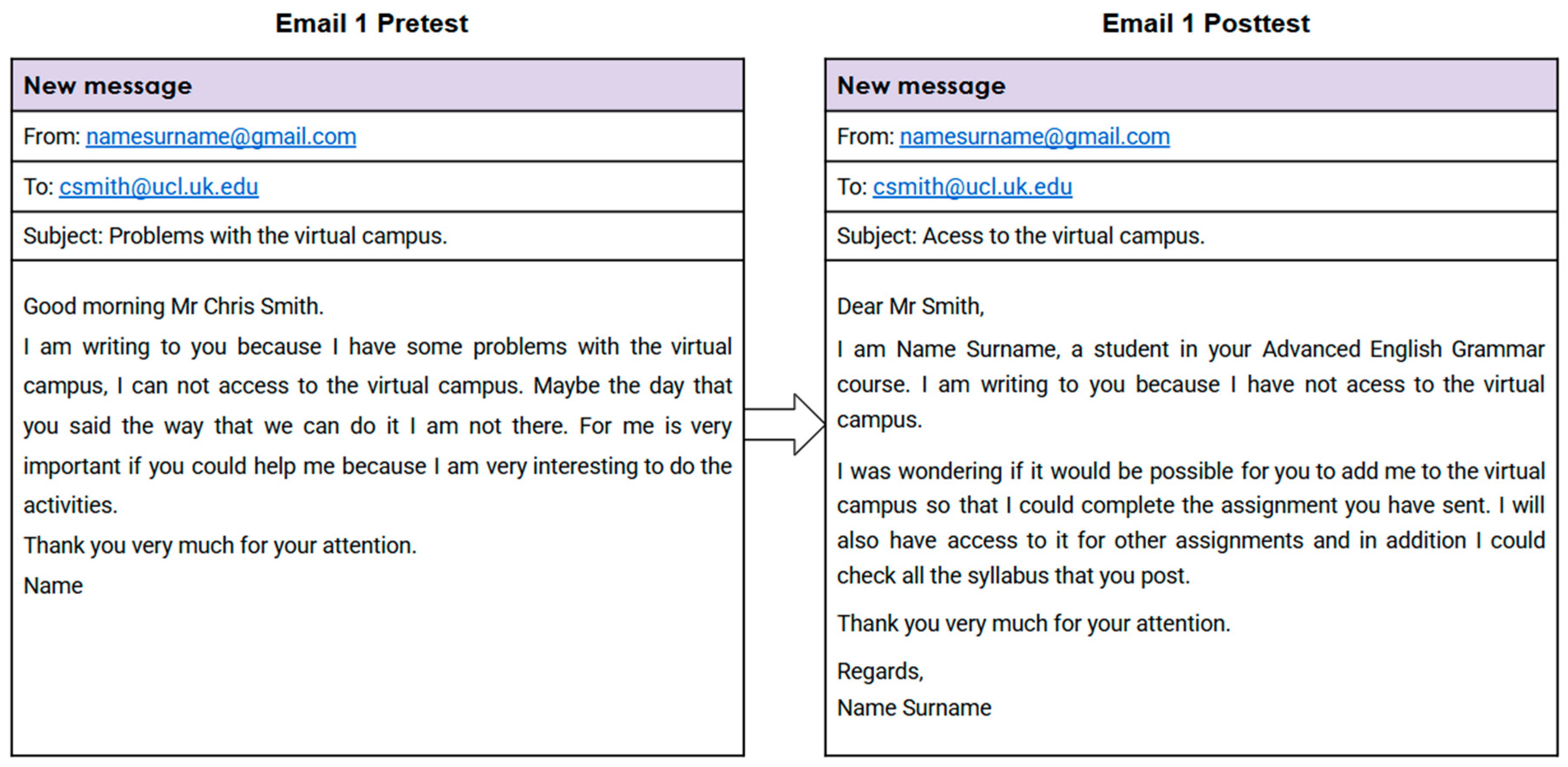

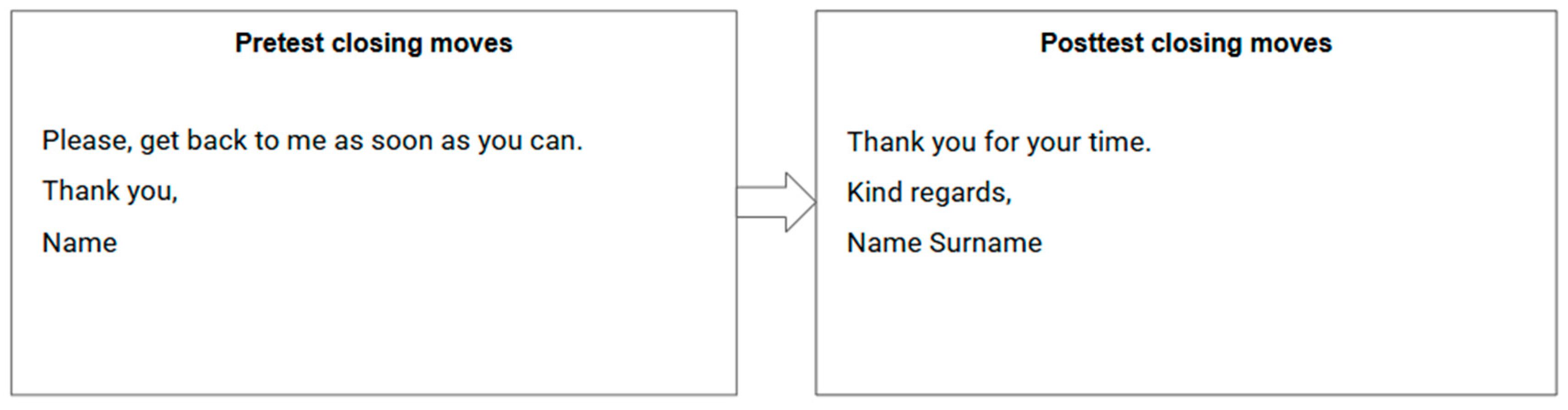

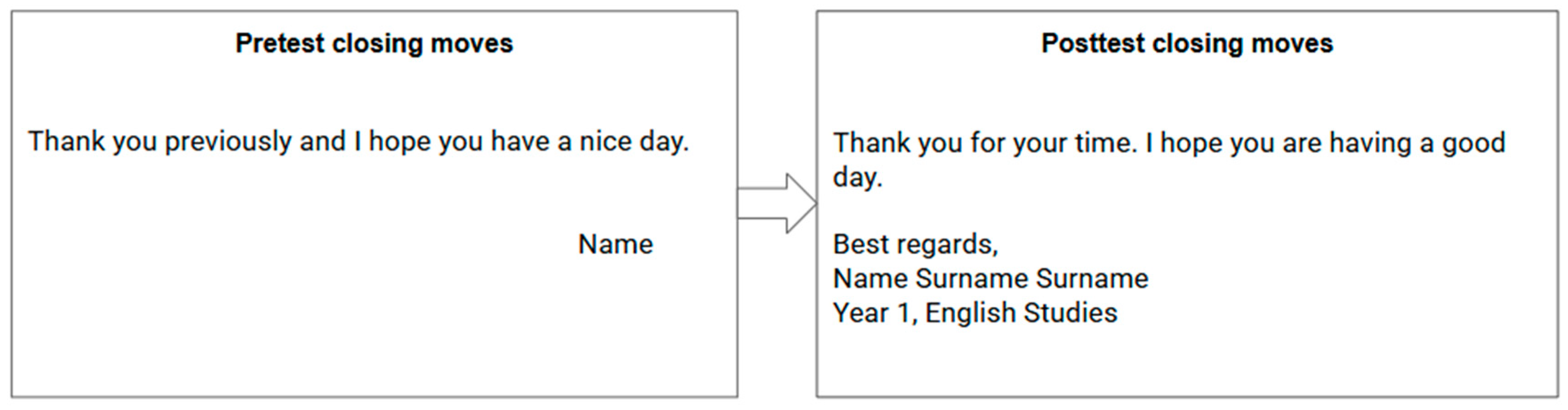

5.1. Effects of Self-Access Instruction

5.2. Influence of L2 Proficiency Level on Self-Access Instruction Effects

5.3. Effects of Instruction and L2 Proficiency Level on Confidence Level

- (1)

- “With these activities, I feel quite insecure because I think I don’t express myself as well as I should, or that I don’t have the vocabulary I should have. I feel like I’m constantly making spelling mistakes or that I’m expressing myself poorly.” (Original in Spanish) (Student 51; B1; Email 2; pretest)

- (2)

- “It really has been a bit difficult for me to write it [the email] overall, because I think some of the words I used may not be appropriate in this context, but I couldn’t find another way to say them in English. Also, I think some of the sentences sound a bit ‘Spanish-like’.” (Original in Spanish) (Student 62; B1; Email 2; Pretest)

- (3)

- “I’m not sure whether it [the email] is entirely appropriate. [...] I’ve realized that I can’t think of any other way to begin the email besides saying ‘I am getting in touch with you,’ and I’m not even sure whether that phrase is the most appropriate for a formal context.” (Original in Spanish) (Student 3; C1; Email 2; Pretest).

- (4)

- “I find it difficult to write emails in English when I have to use formal language because it’s something I’m not used to and don’t use in my daily life. [...] I’ve only used this register in assignments or official exams, but never as part of my routine.” (Original in Spanish) (Student 71; B1; Email 2; pretest)

- (5)

- “The biggest difficulty is using formal language when writing an email in another language, especially since when I studied this, it wasn’t taught with the goal of being used in the future, but just to pass an exam.” (Original in Spanish) (Student 22; B2; Email 1; pretest)

- (6)

- “After writing so many emails I don’t find it difficult anymore; I just try to find the best way to write them so they are specific, clear and appropriate” (Student 37; C1; Email 1; posttest)

- (7)

- “I haven’t really found any difficulties, I only paid more attention to the things that I saw that my emails lacked of [sic] when I compared them to the models in Task 3.” (Student 2; B2; Email 1; posttest)

- (8)

- “I think that thanks to the skills and abilities I’ve developed during this project, I feel more confident about what I’ve written. I used to think that the more text I wrote, the better the task would be. But now I’ve realized that sometimes brevity and clarity are better than writing a lot.” (Original in Spanish) (Student 51; B1; Email 2; posttest)

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

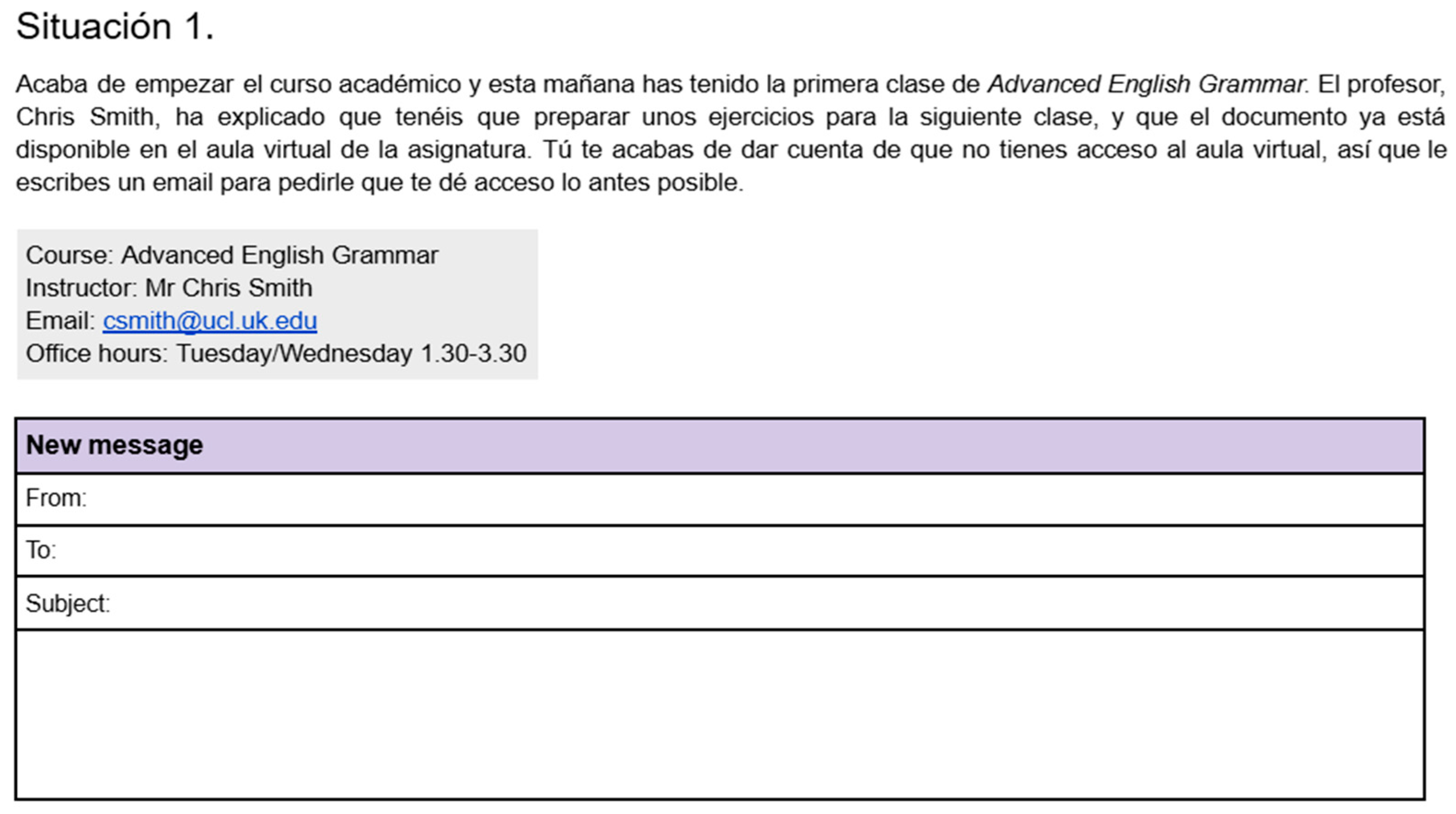

- Scenario 1 (original in Spanish):

- The academic year has just started, and this morning you had your first Advanced English Grammar class. The lecturer, Chris Smith, has explained that you need to prepare some exercises for the next session, and that the file is already available on the course online learning platform. You’ve just realized that you don’t have access to the learning platform, so you decide to write an email to ask them to grant you access as soon as possible.

- Lecturer information:

- Email:

- Office hours:

- Scenario 2 (original in Spanish; situation adapted from Y. Chen, 2015):

- After attending several sessions of the Advanced English Grammar course, you realize that the level of difficulty is very high and that passing the class will be challenging for you. You would like to request a change of course and enroll in World Englishes, which seems very interesting. Since the class is already quite full, you have been told that you need explicit permission from the lecturer, Cathy Barnes, in order to transfer. You decide to write an email to the professor, whom you don’t know, to request her permission.

- Lecturer information:

- Email:

- Office hours:

Appendix B

| Dimension | Level 4 (Completely Appropriate/ Adequate) | Level 3 (Mostly Appropriate/ Adequate) | Level 2 (Slightly Inappropriate/ Inadequate) | Level 1 (Inappropriate/ Inadequate) | Level 0 (Absence) |

| Readability Refers to the effort required on the part of the reader to understand the email purpose and ideas.

| The email is easily comprehensible and reads smoothly; the purpose and ideas are clearly stated. Absence of elements that hinder comprehension. Key university–life terminology is accurately used. | The email is comprehensible. Only a few sentences are unclear but are understood, without too much effort, after a second reading. Some mistakes in key university–life terminology may be found. | Some sentences are hard to understand at first reading. A second reading helps to clarify the purposes of the email and the ideas conveyed; some doubts may persist. Frequent mistakes related to university–life terminology are found. Too many ideas make the purpose of the email difficult to find. | The email is scarcely comprehensible. Its purpose is not clearly stated and the reader struggles to understand the ideas. The reader has to guess most of them. Lack of general knowledge of university–life terminology. False friends and made-up words are used. | The email is not comprehensible. |

| Organization Refers to the presence/absence of framing moves (a subject line, salutation, opening, body and closure) and of a general structure that facilitates identification of key information. | Contains all necessary framing moves. Clear structure. Facilitates finding information in the email. | Most framing moves are present. Clear structure. | Some framing moves are missing. Lacks some structure. | Most framing moves are missing. Mostly lacks structure. It is difficult to find key information in the email. | No clear framing moves. No clear structure. |

| Request appropriateness Refers to the directness of the request, and the use of internal mitigators (both syntactic and lexical–phrasal), in relation to the given context. | The level of directness and mitigation is completely appropriate for the given context. | The level of directness and/ or mitigation is mostly appropriate for the given context. | Some mitigation or indirectness appears, but it is slightly inappropriate for the given context. | Unmitigated, direct request, inappropriate for the given context. The request is too vague to be actionable. The request does not match the instructions of the task. | No clear request is included. |

| Use of content moves Refers to the relevance and adequacy of the content moves included according to the situation. | All content moves included are relevant and adequate in the given situation. The request is adequately supported. | Most content moves are relevant and adequate in the given situation. Some support may still be needed. | Some content moves are included but may be irrelevant or inadequate in the given situation. Unnecessary information is included. | Necessary content moves are missing. Those included are not relevant/ adequate in the given situation. | No supporting moves are included. |

| Overall sociopragmatic awareness Refers to the appropriateness of register in the given context (distance, imposition) evidenced in the level of formality, politeness, and word choices. Considerations of awareness of student–professor relationship in the given context.

| Register is appropriate to the given context. The choice of register shows fine-tuned awareness of the student–professor relationship in the given context. It shows fine-tuned awareness of the imposition of the request. No aggravators are found. | Register is mostly appropriate to the given context. Minor lapses in register may appear. Shows general awareness of the student–professor relationship in the given context. It shows some awareness of the imposition of the request. One aggravator may be found. | Register is slightly inappropriate to the given context. Certain points show some awareness of the student–professor relationship in the given context. It shows a general lack of awareness of the imposition of the request. Aggravators can be found in the email. | Register is not appropriate to the given context. It shows a general lack of awareness of the student–professor relationship in the given context. It shows lack of awareness of the imposition of the request. Aggravators can be found in the email. | Complete lack of awareness is shown. |

| 1 | For a detailed account of the module development and its theoretical underpinnings please see López-Serrano (2025). |

References

- Alcón-Soler, E. (2015a). Pragmatic learning and study abroad: Effects of instruction and length of stay. System, 48, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcón-Soler, E. (2015b). Instruction and pragmatic change during study abroad email communication. Innovation in Language Teaching and Learning, 9(1), 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, D. (2004). Oxford placement test. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bardovi-Harlig, K. (2018). Matching modality in L2 pragmatics research design. System, 75, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoldi, E., & Gesuato, S. (2025, May 26–31). Exploiting AI to provide corrective-constructive feedback on student writing: The case of EFL email requests to faculty. 21st EALTA Annual Conference, Salzburg, Austria. [Google Scholar]

- Biesenbach-Lucas, S. (2007). Students writing e-mails to faculty: An examination of e-politeness among native and non-native speakers of English. Language Learning and Technology, 11(2), 59–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. (2015). Developing Chinese EFL learners’ email literacy through requests to faculty. Journal of Pragmatics, 75, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. S., Hsu, H. T., & Tai, H. Y. (2023). The relative effects of corrective feedback and language proficiency on the development of L2 pragmalinguistic competence: The case of request downgraders. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, 63(1), 341–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codina-Espurz, V. (2022). Students’ perception of social contextual variables in mitigating email requests. The Grove. Working Papers on English Studies, 29, 57–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codina-Espurz, V., & Salazar-Campillo, P. (2019). Student to faculty email consultation in English, Spanish and Catalan in an academic context. In P. Salazar-Campillo, & V. Codina-Espurz (Eds.), Investigating the learning of pragmatics across ages and contexts (pp. 196–217). Brill. [Google Scholar]

- East, M. (2009). Evaluating the reliability of a detailed analytic scoring rubric for foreign language writing. Assessing Writing, 14(2), 88–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economidou-Kogetsidis, M. (2011). ‘Please answer me as soon as possible’: Pragmatic failure in non-native speakers’ e-mail requests to faculty. Journal of Pragmatics, 43, 3193–3215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Félix-Brasdefer, J. C. (2012). E-mail requests to faculty: E-politeness and internal modification. In M. Economidou-Kogetsidis, & H. Woodfield (Eds.), Interlanguage request modification (pp. 87–118). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, S. (2006). The use of pragmatics in e-mail requests made by second language learners of English. Studies in Language Sciences 5, 143–162. [Google Scholar]

- Fryer, L. K., Bovee, H. N., & Nakao, K. (2014). E-learning: Reasons students in language learning courses don’t want to. Computers & Education, 74, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Lloret, M. (2022). Technology-mediated tasks for the development of L2 pragmatics. Language Teaching Research, 26(2), 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halenko, N., Savić, M., & Economidou-Kogetsidis, M. (2021). Second language email pragmatics: Introduction. In M. Economidou-Kogetsidis, M. Savić, & N. Halenko (Eds.), Email pragmatics and second language learners (pp. 1–12). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Halenko, N., & Winder, L. (2021). Experts and novices: Examining academic email requests to faculty and developmental change during study abroad. In M. Economidou-Kogetsidis, M. Savić, & N. Halenko (Eds.), Email pragmatics and second language learners (pp. 101–126). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks, B. (2010). An experimental study of native speaker perceptions of non-native request modification in e-mails in English. Intercultural Pragmatics, 7, 221–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L., Kubelec, S., Keng, N., & Hsu, L. (2018). Evaluating CEFR rater performance through the analysis of spoken learner corpora. Language Testing in Asia, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishihara, N. (2010). Assessing learners’ pragmatic ability in the classroom. In D. Tatsuki, & N. Houck (Eds.), Pragmatics: Teaching speech acts (pp. 209–227). TESOL Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara, N. (2018). Intercultural pragmatic failure. In J. I. Liontas, & M. DelliCarpini (Eds.), The TESOL encyclopedia of English language teaching. Wiley-Blackwell. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/9781118784235.eelt0284 (accessed on 17 May 2025).

- Keller, J. M. (2010). Motivational design for learning and performance: The ARCS model approach. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Kerber, N., Shea, J., & Tecedor, M. (2023). “Sorry, that’s all I know!”: A study on web-based pragmatic instruction for novice learners. Foreign Language Annals, 56(3), 645–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuiken, F., & Vedder, I. (2022). Measurement of functional adequacy in different learning contexts: Rationale, key issues, and future perspectives. TASK, 2(1), 8–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S., & Kunnan, A. J. (2016). Investigating the application of automated writing evaluation to Chinese undergraduate English majors: A case study of WriteToLearn. CALICO Journal, 33(1), 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Serrano, S. (2025). Integrating L2 pragmatics into the curriculum: Design, implementation, and EFL students’ and teachers’ perceptions of a self-access web-based module on email requests to faculty. Revista de Lingüística y Lenguas Aplicadas, 20, 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacIntyre, P. D., Clément, R., Dörnyei, Z., & Noels, K. A. (1998). Conceptualizing willingness to communicate in a L2: A situational model of L2 confidence and affiliation. Modern Language Journal, 82, 545–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacIntyre, P. D., Gregersen, T., & Mercer, S. (2016). Positive psychology in second language acquisition. Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Flor, A. (2006). The effectiveness of explicit and implicit treatments on EFL learners’ confidence in recognizing appropriate suggestions. In K. Bardovi-Harlig, C. Felix- Brasdefer, & A. S. Omar (Eds.), Pragmatics and Language Learning (Vol. 11, pp. 199–225). University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 9780824831370. [Google Scholar]

- Merrison, A. J., Wilson, J., Davies, B. L., & Haugh, M. (2012). Getting stuff done: Comparing e-mail requests from students in higher education in Britain and Australia. Journal of Pragmatics, 44(9), 1077–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, A. A. (2022). Using self-access materials to learn pragmatics in the US Academic setting: What do Indonesian Learners pick up? In N. Halenko, & J. Wang (Eds.), Pragmatics in language teaching (pp. 200–227). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, M. T. T. (2018). Pragmatic development in the instructed context. A longitudinal investigation of L2 email requests. Pragmatics, 28, 217–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M. T. T., Do, H. T., Pham, T. T. T., & Nguyen, A. T. (2017). The effectiveness of corrective feedback for the acquisition of L2 pragmatics: An eight-month investigation. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, 56(3), 345–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M. T. T., Do, T. T. H., Nguyen, A. T., & Pham, T. T. T. (2015). Teaching email requests in the academic context: A focus on the role of corrective feedback. Language Awareness, 24(2), 169–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rau, D. H. V., & Rau, G. (2016). Negotiating personal relationships through email terms of address. In Y. Chen, D. H. Rau, & G. Rau (Eds.), Email discourse among Chinese using English as a lingua franca (pp. 11–36). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, W., Li, S., & Lü, X. (2022). A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of second language pragmatics instruction. Applied Linguistics, 44(6), 1010–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar-Campillo, P. (2018). Student-initiated email communication: An analysis of openings and closings by Spanish EFL learners. Sintagma, 30, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelton-Strong, S. J., & Mynard, J. (2020). Promoting positive feelings and motivation for language learning: The role of a confidence-building diary. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 15, 458–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sykes, J. M., & Cohen, A. D. (2008). Observed learner behavior, reported use, and evaluation of a website for learning Spanish pragmatics. In M. Bowles, R. Foote, & S. Perpiñán (Eds.), Second language acquisition and research: Focus on form and function. Selected proceedings of the 2007 second language research forum (pp. 144–157). Cascadilla Press. [Google Scholar]

- Taguchi, N., Kostromitina, M., & Wheeler, H. (2022). Individual difference factors for second language pragmatics. In S. Li, P. Hiver, & M. Papi (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of second language acquisition and individual differences (pp. 310–330). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Usó-Juan, E. (2021). Long-term instructional effects on learners’ use of email request modifiers. In M. Economidou-Kogetsidis, M. Savić, & N. Halenko (Eds.), Email pragmatics and second language learners. John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Usó-Juan, E. (2022). Exploring the role of strategy instruction on learners’ ability to write authentic email requests to faculty. Language Teaching Research, 26(2), 213–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercellotti, M. L., & McCormick, D. E. (2021). Constructing analytic rubrics for assessing open-ended tasks in the language classroom. The Electronic Journal for English as a Second Language, 24(4). Available online: https://tesl-ej.org/wordpress/issues/volume24/ej96/ej96a2/ (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Wain, J., Timpe-Laughlin, V., & Oh, S. (2019). Pedagogic principles in digital pragmatics learning materials: Learner experiences and perceptions. Educational Testing Service Research Reports, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigle, S. C. (2002). Assessing writing. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L. (2016). Learning to express gratitude in Mandarin Chinese through web-based instruction. Language Learning & Technology, 20, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L. (2017). The effects of L2 proficiency on pragmatics instruction: A web-based approach to teaching Chinese expressions of gratitude. L2 Journal, 9(1), 62–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L. (2024). Effects of website-delivered instruction on development of pragmatic awareness in L2 Chinese. In S. Li (Ed.), Pragmatics of Chinese as a second language (pp. 237–256). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L. (2025). Exploring the learning benefits of website-delivered pragmatics instruction: The case of L2 Mandarin Chinese. Foreign Language Annals, 58(2), 417–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefi, M., & Nassaji, H. (2019). A meta-analysis of the effects of instruction and corrective feedback on L2 pragmatics and the role of moderator variables: Face-to-face vs. computer-mediated instruction. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 170(2), 277–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Distance | Imposition | Communicative Purpose | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Email 1 | + | − | Request for help accessing the class online learning platform. |

| Email 2 | + | + | Request for permission to enroll in the lecturer’s class. |

| N | Pretest M (SD) | Posttest M (SD) | Gains M | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total score | 68 | 18.81 (5.33) | 32.82 (4.88) | 14.01 | −23.086 | <.001 |

| Email 1 | 68 | 9.51 (2.85) | 16.71 (2.42) | 7.19 | −22.521 | <.001 |

| Email 2 | 68 | 9.29 (2.80) | 16.12 (2.87) | 6.82 | −18.265 | <.001 |

| Total Score | Pretest M (SD) | Posttest M (SD) | Gains M | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Readability | 4.75 (1.16) | 6.45 (1.19) | 1.70 | −11.624 | <.001 |

| Organization | 3.87 (1.50) | 7.25 (1.02) | 3.38 | −18.891 | <.001 |

| Request appropriateness | 2.60 (1.37) | 6.09 (1.49) | 3.49 | −16.045 | <.001 |

| Content moves | 3.57 (1.28) | 6.23 (1.17) | 2.66 | −17.515 | <.001 |

| Sociopragmatic awareness | 4.01 (1.35) | 6.79 (1.08) | 2.78 | −17.442 | <.001 |

| Group | N | Pretest M (SD) | Posttest M (SD) | Gains M | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | 22 | 16.04 (4.61) | 30.04 (4.96) | 14.00 | −10.915 | <.001 |

| B2 | 23 | 18.91 (5.38) | 33.65 (3.54) | 14.74 | −15.907 | <.001 |

| C1 | 23 | 21.35 (4.78) | 34.65 (4.98) | 13.30 | −13.941 | <.001 |

| B1 | Gain | B2 | Gain | C1 | Gain | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre M (SD) | Post M (SD) | Pre M (SD) | Post M (SD) | Pre M (SD) | Post M (SD) | ||||

| Readability | 4.00 (0.87) | 5.59 (1.05) | 1.59 | 4.61 (1.03) | 6.61 (0.99) | 2.00 | 5.61 (0.99) | 7.13 (1.01) | 1.52 |

| Organization | 3.32 (1.42) | 7.04 (1.13) | 3.72 | 3.96 (1.55) | 7.43 (0.97) | 3.47 | 4.30 (1.40) | 7.26 (1.05) | 2.96 |

| Request appropriateness | 2.31 (1.39) | 5.41 (1.38) | 3.10 | 2.52 (1.20) | 6.13 (1.22) | 3.61 | 2.96 (1.50) | 6.70 (1.33) | 3.74 |

| Content moves | 3.00 (1.02) | 5.59 (1.10) | 2.59 | 3.65 (1.33) | 6.39 (1.03) | 2.74 | 4.04 (1.30) | 6.70 (1.15) | 2.66 |

| Sociopragmatic awareness | 3.41 (1.26) | 6.41 (1.14) | 3.00 | 4.17 (1.40) | 7.09 (0.79) | 2.92 | 4.43 (1.24) | 6.87 (1.21) | 2.44 |

| N | Pretest M (SD) | Posttest M (SD) | Gains | Z | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global rating | 68 | 3.55 (0.63) | 4.03 (0.46) | 0.48 | −5.133 | <.001 |

| Email 1 | 68 | 3.51 (0.72) | 4.10 (0.55) | 0.59 | −4.835 | <.001 |

| Email 2 | 68 | 3.58 (0.73) | 3.97 (0.54) | 0.39 | −3.281 | <.001 |

| Group | N | Pretest M (SD) | Posttest M (SD) | Gains | Z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | 22 | 3.36 (0.51) | 3.89 (0.51) | 0.53 | −3.152 | .001 |

| B2 | 23 | 3.54 (0.62) | 4.11 (0.45) | 0.57 | −3.245 | <.001 |

| C1 | 23 | 3.74 (0.72) | 4.11 (0.42) | 0.37 | −2.499 | .011 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

López-Serrano, S.; Martínez-Flor, A.; Sánchez-Hernández, A. The Effects of Self-Access Web-Based Pragmatic Instruction and L2 Proficiency on EFL Students’ Email Request Production and Confidence. Languages 2025, 10, 279. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10110279

López-Serrano S, Martínez-Flor A, Sánchez-Hernández A. The Effects of Self-Access Web-Based Pragmatic Instruction and L2 Proficiency on EFL Students’ Email Request Production and Confidence. Languages. 2025; 10(11):279. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10110279

Chicago/Turabian StyleLópez-Serrano, Sonia, Alicia Martínez-Flor, and Ariadna Sánchez-Hernández. 2025. "The Effects of Self-Access Web-Based Pragmatic Instruction and L2 Proficiency on EFL Students’ Email Request Production and Confidence" Languages 10, no. 11: 279. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10110279

APA StyleLópez-Serrano, S., Martínez-Flor, A., & Sánchez-Hernández, A. (2025). The Effects of Self-Access Web-Based Pragmatic Instruction and L2 Proficiency on EFL Students’ Email Request Production and Confidence. Languages, 10(11), 279. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10110279