Abstract

In recent years, the rapid development of commercial satellite projects, such as low-Earth orbit (LEO) communication and remote sensing constellations, has driven the satellite industry toward low-cost, rapid development, and large-scale deployment. Commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) components have been widely adopted across various commercial satellite platforms due to their advantages of low cost, high performance, and plug-and-play availability. However, the space environment is complex and hostile. COTS components were not originally designed for such conditions, and they often lack systematically flight-verified protective frameworks, making their reliability issues a core bottleneck limiting their extensive application in critical missions. This paper focuses on COTS solid-state drives (SSDs) onboard the Jilin-1 KF satellite and presents a full-lifecycle reliability practice covering component selection, system design, on-orbit operation, and failure feedback. The core contribution lies in proposing a full-lifecycle methodology that integrates proactive design—including multi-module redundancy architecture and targeted environmental stress screening—with on-orbit data monitoring and failure cause analysis. Through fault tree analysis, on-orbit data mining, and statistical analysis, it was found that SSD failures show a significant correlation with high-energy particle radiation in the South Atlantic Anomaly region. Building on this key spatial correlation, the on-orbit failure mode was successfully reproduced via proton irradiation experiments, confirming the mechanism of radiation-induced SSD damage and providing a basis for subsequent model development and management decisions. The study demonstrates that although individual COTS SSDs exhibit a certain failure rate, reasonable design, protection, and testing can enhance the on-orbit survivability of storage systems using COTS components. More broadly, by providing a validated closed-loop paradigm—encompassing design, flight verification and feedback, and iterative improvement—we enable the reliable use of COTS components in future cost-sensitive, high-performance satellite missions, adopting system-level solutions to balance cost and reliability without being confined to expensive radiation-hardened products.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the proposal of mega-constellations has driven a paradigm shift in the global satellite industry, particularly within the commercial space sector, characterized by low cost, rapid development, and large-scale deployment [1]. Commercial satellite projects, represented by low Earth orbit (LEO) communication and remote sensing constellations, have imposed unprecedented stringent demands on the cost-effectiveness and development cycles of satellite platforms [2,3]. Against this backdrop, commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) components have been widely adopted across various commercial satellite platforms—from onboard computers and communication payloads to rechargeable batteries and even critical mission management units—due to their significant cost advantages, high performance levels, and plug-and-play availability [4,5,6,7]. Among these, high-capacity onboard storage products based on COTS components are particularly critical for supporting data-intensive missions such as high-resolution Earth observation and on-board intelligent processing.

However, the space environment is extremely complex and hostile, encompassing multiple adverse factors such as high-energy particle radiation, extreme temperature fluctuations, and vacuum conditions. Unlike traditional space-grade components, which undergo stringent process control and protective design, COTS components are not originally designed for such harsh environments. Their inherent reliability issues have become a core bottleneck limiting their widespread application in critical missions. Common radiation effects include single-event effects (SEE), total ionizing dose (TID), and displacement damage (DD) [8,9,10], which can severely impact system performance, leading to anomalies or even catastrophic failures [11,12]. SEE induced by high-energy particle radiation, particularly single-event upsets (SEU) that may corrupt data and single-event latch-ups (SEL) that can cause functional interruptions, pose significant threats to the stable on-orbit operation of COTS products [13]. Although COTS components can substantially reduce initial costs, their potential for anomalies and failures may jeopardize the success of the entire mission, thereby incurring higher lifecycle costs. For instance, the COTS SRAM chip from CYPRESS incorporates a novel latch-up suppression circuit. However, during high-energy particle irradiation testing, SEE still induced burst multiple-bit upsets in the chip, with the number of flipped bits exceeding 100. Analyses confirmed that this phenomenon is attributed to local latch-up effects, which significantly diminish the effectiveness of error detection and correction hardening in the space environment [14]. Furthermore, during the on-orbit operation of the PROBA-V satellite, the COTS SRAM memory in its redundant modules exhibited unexpectedly high error rates. By comparing experimental simulation data with the flight data, researchers analyzed and concluded that temperature and shielding variations may be responsible for the discrepancy in error rates between the primary and redundant lines [15]. Therefore, COTS components still require additional radiation hardening measures—such as enhanced shielding and redundancy design—for deployment in space environments like those of LEO satellites. Shielding designs utilizing high-atomic-number materials such as tantalum, tungsten, and lead offer effective protection against low-energy particle radiation and TID effects [16]. However, their effectiveness is limited against high-energy particles and heavy ions, and they are largely ineffective against SEE. Therefore, the most robust approach to ensuring reliability typically includes circuit-level radiation-hardened-by-design techniques or system-level triple modular redundancy (TMR). For instance, a highly stable and radiation-hardened latch named HITTSFL, which is tolerant to triple-node upsets (TNUs) and single-event transients (SET), has been proposed. It utilizes three inverters to converge the stored values from multi-parallel Dual-Interlocked-storage Cells to the input of a Schmitt trigger, thereby preventing the flipped values caused by a TNU from being maintained and filtering out SETs [17]. A highly reliable radiation-hardened-by-design memory cell, RHBD-14T, has also been introduced. By employing redundant nodes at the circuit level and implementing node isolation and source isolation techniques at the layout level, the RHBD-14T cell can recover to the correct state from multi-node upsets induced by SEE [18].

However, considering the potential power consumption burden and the current level of technological maturity associated with the hardware improvements mentioned above, these methods are generally not yet suitable for modern small satellite missions. Additionally, for aerospace systems utilizing COTS components, a series of fast recovery strategies for fault detection and isolation have been explored. These strategies can be broadly categorized into hardware-centric solutions and software-centric solutions. A parity-based dual-modular redundancy method has been proposed for the interconnect interface of COTS System-on-Chips in nanosatellites, aiming to enhance the reliability of data transmission between the core processing unit and the FPGA. This method was validated through simulation experiments and compared with TMR technology. The simulations demonstrated that the total error percentage for this configured method decreases and approaches that of TMR as the SEU rate decreases. Concurrently, this method reduces hardware resource utilization and power consumption compared to a TMR implementation [19]. The French National Centre for Space Studies (CNES) has specifically developed two fault-tolerant architectures for COTS components in spacecraft. One, known as the DMT architecture, is based on a temporal redundancy scheme. The other, called the DT2 architecture, is based on a structural duplex framework with minimal replication design. Both architectures not only reduce the susceptibility of COTS components to SEE but also offer advantages in terms of lower lifecycle cost, reduced mass, and lower power consumption compared to traditional TMR designs [20]. To address SEU faults in COTS software-defined radios, a pure software framework for fault detection, isolation, and recovery was designed specifically for AD936x radio frequency agile transceivers. This method relies on three core technologies: active register scrubbing, real-time health monitoring, and autonomous fault recovery. In test scenarios, this method achieved 100% fault coverage with negligible computational overhead [21].

To address the reliability challenges of complex space missions, current research primarily focuses on reconfigurable systems [22,23], agile engineering processes [24], and system-level verification techniques [25,26]. These three aspects are key methods for enhancing both the efficiency of the development process and the resilience of the systems themselves. These directions aim to ensure the reliability and effectiveness of COTS-based complex systems in the space environment. Although extensive research has been conducted on the reliability of COTS components for aerospace applications, it has yet to systematically address the usability issues of COTS. This gap stems from a significant divide between theoretical protective strategies for COTS device deployment and systematically verified practical frameworks. Existing efforts often concentrate on isolated stages, such as analyzing the mechanisms of radiation effects, designing hardened circuits, or developing system-level fault-tolerant algorithms. There is a lack of a closed-loop methodology that seamlessly integrates multiple phases: pre-flight design and screening, real-time on-orbit performance monitoring, data-driven root-cause analysis of failures, and the feedback of on-orbit experience. This fragmented research model struggles to meet the practical engineering needs of commercial satellites, which require a balanced trade-off among cost, performance, and reliability. Consequently, it fails to establish a continuous improvement cycle.

Given this research status, this paper proposes and constructs a reliability study framework covering the entire lifecycle of COTS components, integrating the previously fragmented aspects of COTS reliability into an organic, closed-loop, and engineering-applicable system. The goal is to systematically ensure the reliability of COTS components for space missions without significantly compromising their cost and performance advantages, thereby providing technical support and a practical foundation for developing future high-performance, low-cost commercial satellites. Our work makes three core contributions: First, considering the pronounced demand for capacity and reliability in storage systems for high-resolution remote sensing satellites, we focus on a typical COTS-based onboard storage product and detail a practical strategy incorporating redundancy and protection. Second, moving beyond conventional ground testing, we conducted an actual on-orbit mission deploying a specific COTS model, investigated potential failure scenarios, collected in-flight failure data, and performed comprehensive analysis of this data to evaluate the capability of COTS components to operate in the space environment. Through this process, employing statistical and geospatial techniques, we empirically pinpointed the South Atlantic Anomaly (SAA) region as the primary driver of SSD failures—an insight critical for mission planning and risk assessment. Third, and most significantly, we completed the closed-loop corroboration by correlating in-flight data with controlled ground experiments, thereby transforming observational data into a verified physical failure mechanism. This finding directly drives the optimized design of next-generation products. This entire process—from design for flight qualification, through fault reproduction, to design feedback—establishes a paradigm for a continuous reliability growth cycle.

2. Satellite Development, Testing, and On-Orbit Operations

The Jilin-1 KF Satellite is a remote sensing satellite within the Jilin-1 satellite constellation, where KF means wide remote sensing image swath. It carries a high-performance space camera designed to provide high-resolution and ultra-wide-swath remote sensing image products. Due to the extremely high optical bandwidth product of its imaging system, a large-capacity storage component is essential to support data compression and temporary storage requirements. To meet these storage demands, KF Satellites are often equipped with Solid State Drives (SSDs), the number of which can be several times greater than that on standard remote sensing satellites. To ensure the satellite operates normally in the space environment, the storage system typically employs space-grade components. However, this significantly increases the manufacturing cost of the KF Satellite. Consequently, a trial operation using COTS SSD has been proposed to reduce satellite manufacturing costs, particularly for satellites like the KF Satellite which have high storage capacity requirements.

2.1. Functional and Reliability Design of the System

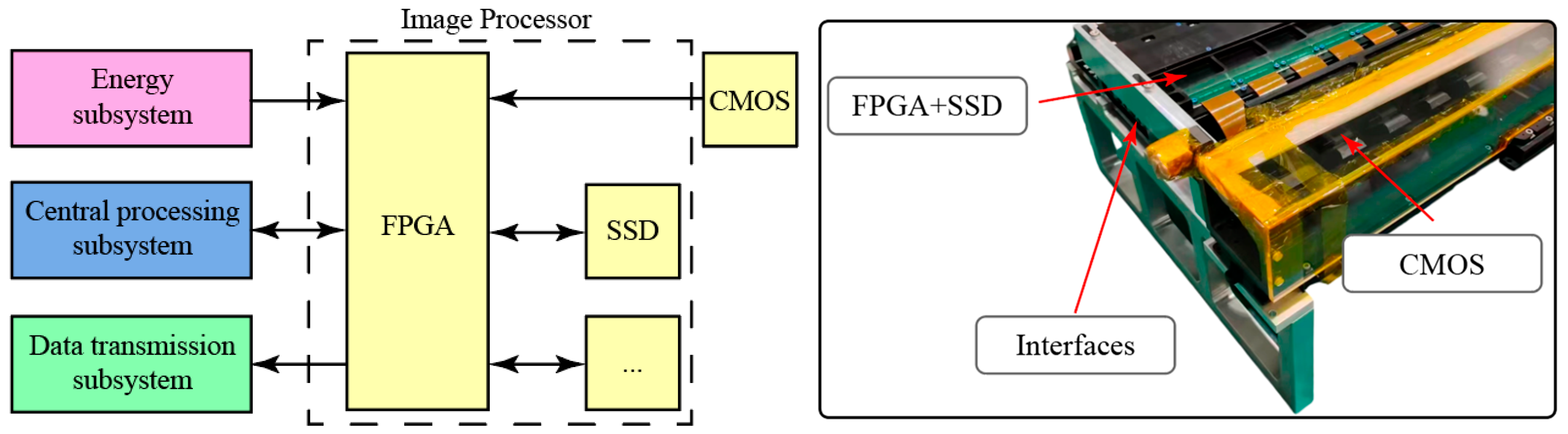

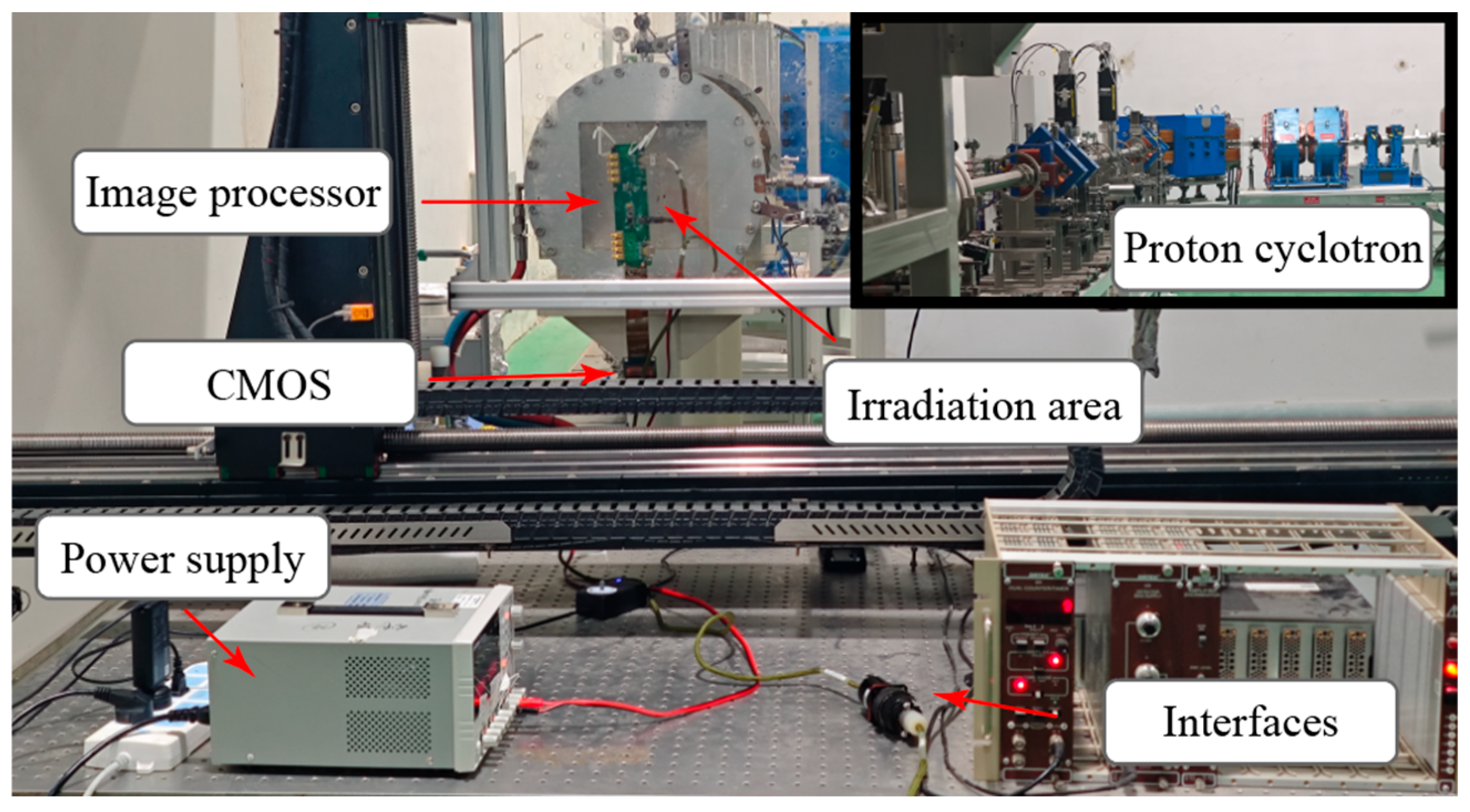

The KF Satellite comprises several subsystems. Its imaging subsystem includes the optical lens assembly, the image detector, and the image processor. Among these, the SSDs are the component of the image processor. The overall architecture of the image processor is illustrated in Figure 1. Its functionalities include: (1) Storing image data from the CMOS sensor during imaging operations into non-volatile SSDs; (2) Sending the data stored on the SSDs to the data transmission subsystem to complete satellite-to-ground data transfer; (3) Receiving and executing command programs from the central processing subsystem and feeding back the status data of the imaging subsystem; (4) Other functions. The KF Satellite carries the image processor utilizing industrial-grade SSDs. In this design, the SSDs are dedicated solely to the storage function, while control functions such as read/write operations and bad block management are implemented by an FPGA. This system features three SSDs configured in a multi-parallel redundancy architecture.

Figure 1.

Functional architecture of the image processor with other components and its partial physical photos.

To ensure that the image processor can fulfill its operational requirements throughout the satellite’s intended lifespan, several reliability protection measures have been designed and implemented, including: (1) Derating design of components, selecting parts with wider operational margins than standard specifications to reduce the probability of system failure due to abnormal conditions; (2) Mechanical protection design, rationally designing the weight, strength, and stiffness of printed circuit boards to mitigate the impact of rocket and satellite platform vibrations on the system; (3) Thermal protection design, forming efficient thermal pathways through rational layout to prevent abnormal temperature rises in components caused by heat accumulation; (4) Electrostatic discharge protection and electromagnetic compatibility design, ensuring that internal and external electrical or magnetic stresses do not interfere with normal system operation; (5) Other control measures such as process quality control and supply chain quality control. Furthermore, several environmental adaptation designs have been implemented, including: (1) Protection against TID from space radiation by installing tantalum foil shielding on the exterior of the image processor structure [27]; (2) Protection against SEL from space radiation by incorporating resettable fuses in the power management module to achieve partitioned overcurrent protection design; (3) Protection against SEU from space radiation by implementing a multi-parallel redundancy strategy for critical data and programs within the FPGA.

2.2. Reliability Testing of COTS SSDs

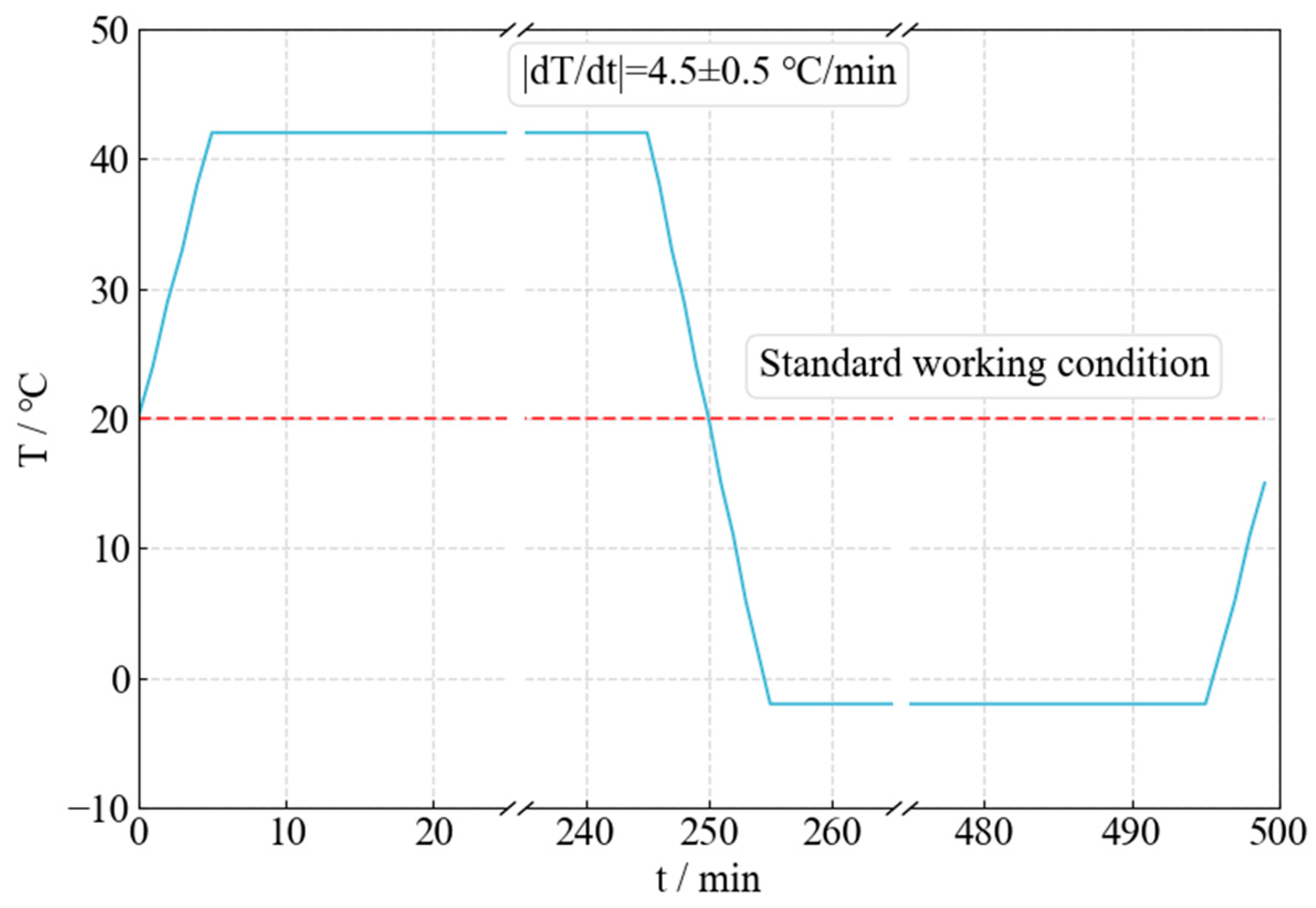

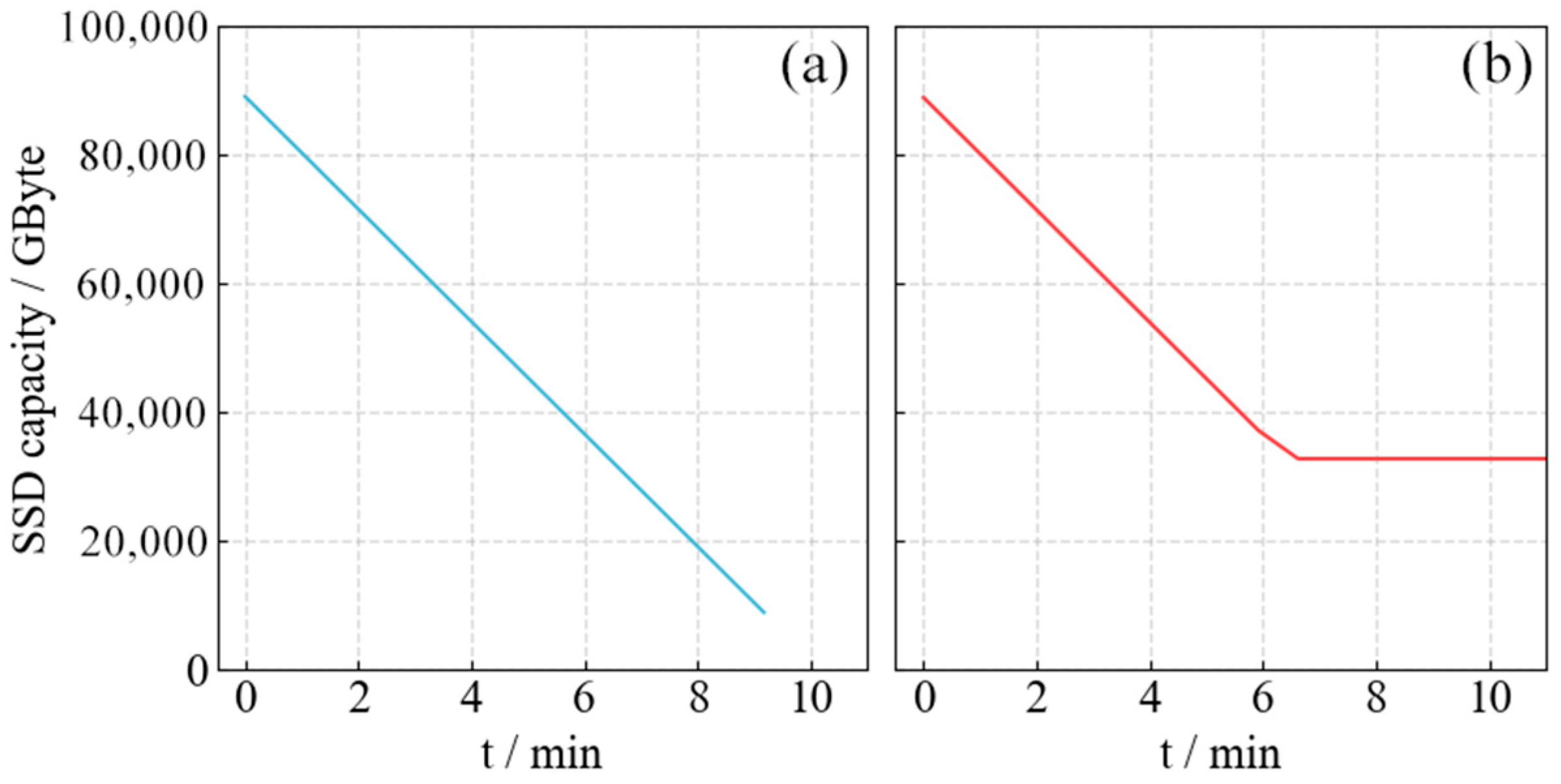

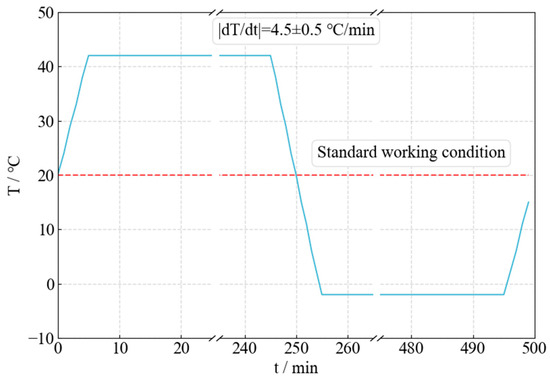

Based on relevant standards and historical experience, in addition to the necessary functional testing of the entire satellite, specific tests were conducted to screen for early failures and assess environmental adaptability. The reliability tests performed on the image processor included atmospheric thermal cycling and vacuum thermal cycling. For the COTS SSDs, these tests served multiple integrated purposes: (1) Reliability screening, using elevated temperatures to rapidly eliminate products with inherent process defects; (2) Reliability qualification, evaluating the reliability level of the SSDs under combined thermal and electrical stress under a right-censored scenario; (3) Reliability acceptance, ensuring the SSDs pass mandatory environmental adaptability tests to obtain flight approval for on-orbit deployment. Within the reliability test regimen, atmospheric thermal cycling was used to accelerate the detection of early failures, while vacuum thermal cycling was employed to accelerate the verification of their adaptability to the vacuum space environment. The profile for a single cycle of the environmental testing was established based on the satellite’s mission profile and the principles of high-temperature accelerated testing, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Profile of the environmental testing within a single cycle.

Constrained by development timelines and testing costs, the reliability testing was implemented following a right-censored life test plan. A total of 420 SSD samples participated in the test, which was conducted in two rounds. In each round, the thermal cycling test lasted for 10.5 cycles, and the thermal vacuum test lasted for 3.5 cycles. Throughout the entire testing process, samples exhibiting early failures—such as read/write speeds failing to meet technical specifications—were screened out. Beyond this, all components operated normally, with all performance metrics meeting requirements, and no samples exhibited random failures.

2.3. On-Orbit Operations of COTS SSDs

The SSDs that underwent testing were carried on the KF Satellite and launched into LEO to provide storage functionality for imaging missions. After the satellite completed its on-orbit testing phase and began routine operations, the COTS SSDs started to fail successively following a period of mission execution. The failure manifestation is as follows: the FPGA activates the controller to power on the SSD, and the SSD can provide a startup response signal, but the FPGA fails to initialize the SSD. When attempting initialization, the SSD cannot return File Allocation Table (FAT) information, and the available capacity is reported as 0. Upon failure of a single COTS SSD, a cold-backup SSD takes over its function. Part of the survival data, with individual SSDs as the unit, is shown in Table 1. In response to this on-orbit performance, we analyzed the failure mechanisms and attempted to identify the root causes.

Table 1.

A partial display of survival data for individual SSDs. The study period spanned from 20 November 2024 (commencement of routine operations) to 30 October 2025 (end of data collection).

3. Failure Mode and Mechanisms Analysis in Space Storage

During ground testing, after screening out early failures, the reliability of the COTS SSDs reached the random failure period of the bathtub curve. However, no failures occurred in the ground environment, allowing failures caused by design issues to be ruled out. Analysis of satellite system problems over the past few decades indicates that a significant portion of issues are attributed to the space environment [28]. For the on-orbit failures, the impact of the external space environment on the SSDs warrants consideration. Since the KF Satellite operates in LEO, the failure mechanisms of the SSDs will be investigated by analyzing both external factors related to the LEO space environment and internal factors related to storage principles.

3.1. LEO Space Environment

3.1.1. Thermal Stress

Solar electromagnetic radiation refers to the energy transmitted by the Sun in the form of electromagnetic waves. While it provides energy input to the satellite, it can also cause unintended temperature increases. Furthermore, a portion of the solar radiation incident on Earth’s atmosphere is scattered by the atmosphere and reflected by the Earth’s surface back into space. The temperature of a satellite is primarily influenced by the combined effects of solar radiation and Earth-atmosphere radiation, which can be expressed as [29]

where , , and represent the internal heat dissipation, solar radiation energy, and Earth-atmosphere radiation energy, respectively, while denotes the overall specific heat capacity of the satellite system. The cooling mechanism of the satellite is described by the fourth term in Equation (1), which represents the heat radiated into space from the satellite’s surface, adhering to the Stefan-Boltzmann law. The primary factors affecting satellite temperature are the solar constant and the surface areas responsible for receiving and emitting thermal radiation. The solar constant, defined as the solar radiation energy received per unit area per unit time at the mean Earth-Sun distance with the surface perpendicular to the solar rays, generally remains stable [30]. Therefore, during on-orbit operations, the rate of temperature change in a satellite is mainly influenced by variations in its operational attitude and orbital position and may experience significant temperature variations under certain extreme conditions [31].

3.1.2. Electrical Stress

Solar electromagnetic radiation interacts with the upper atmosphere, ionizing it to form low-energy plasma regions. The interaction between the satellite and the plasma layer can be described by the particle transport equations [32] as

where represents the electron density at a specific time and position , denotes the electron mobility, is the electron diffusion coefficient, is the electric potential, and signifies the ionization frequency for the generation of new electrons. The terms in this equation include: the rate of change in electron density with time, the electron drift under the influence of an external electric field, the thermal diffusion of electrons, and the rate of ionization due to radiation in different orbits. This exerts electrical effects on satellites, leading to various phenomena, primarily including: (1) Charged plasma bombarding the satellite surface, generating significant voltage [33]; (2) Abnormal arc discharge pulses occurring in the satellite’s high-voltage solar arrays [34]; (3) Interaction between the satellite’s surface potential and charged plasma in space, forming ion drag [35]. These effects can cause unexpected changes in the satellite’s attitude and orbit, while also interfering with the normal operation of signal and power systems. Long-term variations in the electrical properties of the plasma layer are primarily related to solar activity, while also exhibiting seasonal cycles, diurnal cycles, and correlations with latitude and altitude [36].

3.1.3. High-Energy Particle Stress

Previous analyses of satellite system issues have shown that a significant proportion of problems are induced by high-energy particle radiation in space [37]. High-energy particles primarily consist of galactic cosmic rays and solar cosmic rays. The fluxes of both types peak alternately with the solar cycle and can significantly induce electronic component anomalies as well as biological effects. For example, high-energy charged particles can generate internal electric field pulses in local regions of a satellite [38], as

where the satellite is approximated as a sphere of radius with uniform electrical properties. represents the electric field distribution at a specific time and radial distance ; the parameters and denote the relative permittivity of the satellite material and the vacuum permittivity, respectively; is the average energy lost by an incident high-energy electron as it penetrates the satellite’s surface Debye shielding layer. This value determines the maximum depth reachable by the high-energy particle and the resulting charge injection density . Consequently, different satellite designs can lead to concentrations of electric field stress in different locations, potentially causing damage to specific components.

Fortunately, the radiation belts formed by Earth’s magnetosphere trapping these high-energy particles provide relatively effective protection for the region inside them. Earth has two radiation belts, with the Van Allen inner radiation belt mainly distributed at orbital altitudes around 3000 km above the equatorial plane. Over the South Atlantic Anomaly (SAA) region, it dips to a minimum altitude of approximately 500 km [39]. The dominant particles in the Van Allen inner radiation belt are high-energy protons. Their flux is influenced not only by Earth’s magnetosphere but also by extreme events such as solar flares. For LEO satellites, traversing the SAA region entails significant risks of failures caused by high-energy particle radiation [40].

3.2. Typical Failure Mechanisms of NAND Flash Memory

NAND flash memory, due to its superior read speed and robustness, is widely used in computers, large-scale data storage systems, and enterprise servers. The advantages of commercial NAND flash memory are particularly attractive for satellite applications where space and weight are critical, and many space programs have begun adopting state-of-the-art NAND flash memory in on-orbit applications [41]. Related technologies are also rapidly evolving, including multi-level cell (MLC) technology [42] and 3D NAND [43], which enhance storage density. The basic unit of NAND flash memory consists of an N-type MOSFET and a polysilicon floating gate. The control circuit of the storage system applies specific electric fields by altering the electrical signals at the terminals of the MOSFET. These fields control the injection or emission of electrons into or from the floating gate, changing its electrical state to achieve data storage and programming.

Under normal operating conditions, the reliability of flash memory systems primarily refers to their ability to program and store data correctly throughout their lifecycle. This reliability is mainly influenced by the high electric field stress during Fowler-Nordheim tunneling (FN-t) [44]. Unfortunately, the normal functionality of flash memory cells is significantly affected by the space environment: (1) As a typical semiconductor device, flash memory is sensitive to temperature variations, which may accelerate aging due to FN-t, enhance trap-assisted tunneling, and cause charge detrapping [45]; (2) Since electrical signals are used for programming and storage, external electric fields can significantly interfere with normal flash memory behavior, such as inducing unintended charge migration [46]; (3) High-energy particle bombardment of semiconductor devices can cause bit flips [47] and DD [48]. These factors can lead to hardware and data failures, resulting in mission failure or even satellite system malfunctions.

In ground systems, the SSD typically functions as external storage for data retention. However, from the perspective of satellite operations, after the satellites complete imaging missions, data is temporarily stored on SSDs. Once the satellite communicates with ground stations and transfers data to ground-based data systems, the drives are formatted [49]. Thus, the satellite’s SSDs essentially function as high-capacity, relatively long data lifetime temporary memory within the entire remote sensing data service system of the satellite. Compared to terrestrial applications, their use in space storage operations leads to higher frequencies of programming and erasing, which often accelerates the degradation of the tunneling oxide layer and reduces data retention capabilities [50].

3.3. Failure Analysis of the Spaceborne Storage

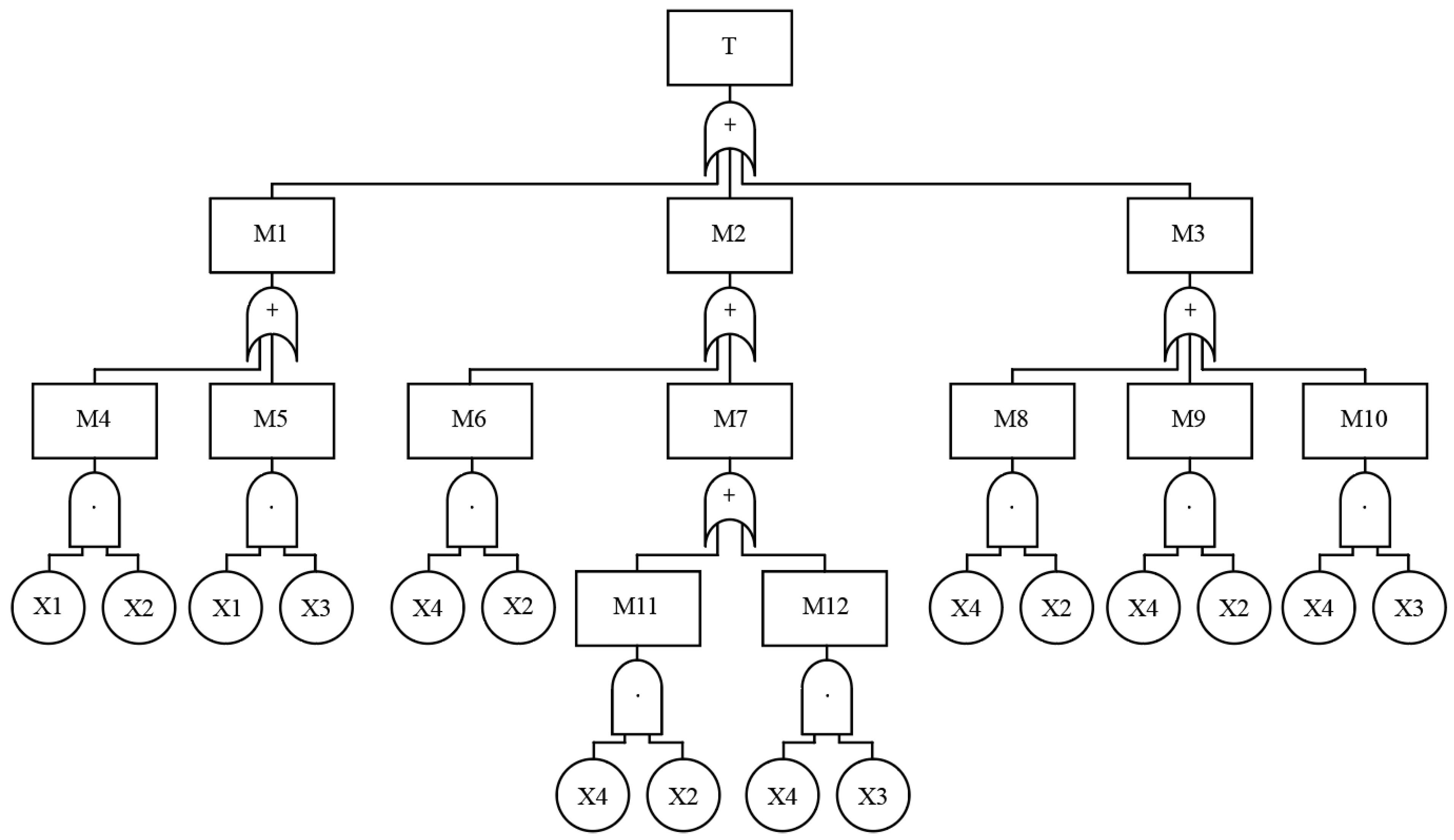

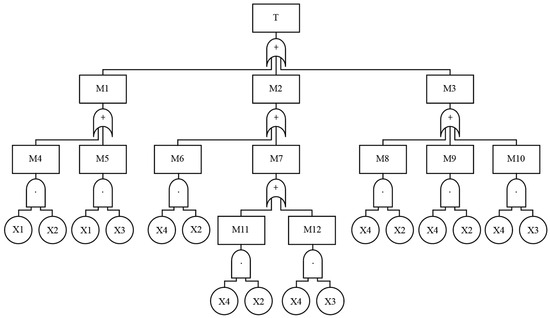

The success state space and failure state space of a system can complementarily describe all its possible states. The failure space is often finite and composed of independent elements, making it more suitable for deductive analysis of the system’s state [51]. To systematically analyze the failures of the spaceborne storage system, a fault tree can be constructed to clarify the failure mechanisms, as illustrated in Figure 3. Based on the operational principles of the satellite’s storage system shown in Figure 1, its failures can be attributed to three sub-events: (1) SSD failure, where the drive itself malfunctions, affecting storage functionality. This includes hardware damage due to aging or external environmental factors (e.g., flash memory and peripheral circuits) or corruption of logical states (such as FAT) caused by high-energy particle radiation; (2) Control module failure, where the drive’s control module fails to operate according to commands. Examples include damage to the FPGA itself or interface failures between the FPGA and the drive due to inadequate process control; (3) Power supply module failure, where the drive does not receive the required operational voltage. This could result from hardware damage to power components, interface failures, or latch-up events in MOSFETs induced by high-energy particle radiation, leading to voltage drop.

Figure 3.

The fault tree analysis for spaceborne storage failure. The event definitions in the tree are as follows: T, Top Event, spaceborne storage failure; M1, SSD failure; M2, control module failure; M3, power supply module failure; M4, critical hardware damage of SSD; M5, critical data corruption of SSD; M6, FPGA-SSD interface damage; M7, FPGA failure; M8, power device damage; M9, latch-up of power circuit MOS device; M10, power supply interface damage; M11, critical hardware damage of FPGA; M12, critical data corruption of FPGA; X1, quality grade does not meet environmental adaptation requirements; X2, random Space environmental stress effect; X3, SEE; X4, quality defects due to insufficient quality control.

The relationship between the system failure top event and the basic events is expressed as

where denotes insufficient quality grade of the COTS components, including design or manufacturing processes that fail to meet the reliability requirements for the space environment, or batch-related issues; signifies random Space environmental stress, which may cause random failures in components; refers to high-energy particle radiation, which can trigger latch-up or bit flips in semiconductor devices, leading to power supply failures or logical errors in software; represents process defects due to inadequate quality management during system development and production. On one hand, based on historical flight experience and batch-related issues observed in on-orbit performance, the basic event of process defects can largely be ruled out. On the other hand, given that the SSD can provide an initialization response signal to the FPGA and based on the design logic of the storage system, the intermediate events (control module failure) and (power supply module failure) can also be excluded. Therefore, logically, the failure of the spaceborne storage system can be attributed to the intermediate event (SSD failure). To further pinpoint the exact cause, quality data from both ground testing and on-orbit operations will be analyzed in detail.

4. Analysis of Test and On-Orbit Data, and Failure Reproduction Experiments

To further clarify the failure mechanisms and provide a basis for subsequent reliability management decisions, a series of related data analyses were conducted. These included reliability analysis of ground test and on-orbit operational data, as well as statistical analysis of telemetry data under on-orbit conditions. The analysis pinpointed high-energy particle radiation as the primary cause of failure. Consequently, a high-energy particle radiation test was performed on the hard drives, successfully reproducing the on-orbit failure mode. This step effectively closed the quality issue feedback loop for the COTS SSDs.

4.1. Failure Rate Analysis

As described in Section 2.2, reliability qualification testing under thermal stress was conducted on the COTS SSDs on the ground. Due to constraints in the development timelines, this test was a right-censored accelerated life test. The acceleration factors consist of two parts. First, within the 250 h life test, there was a 120 h high-temperature operating phase. The elevated test environment caused thermal acceleration. During the high-temperature phase, the test temperature was 42.5 °C, while the standard operating temperature is 20 °C. Based on the Arrhenius Model, the acceleration factor is given by

where is the activation energy, taken as 1.3 eV [52,53]; = 8.623 × 10−5 eV/K is the Boltzmann constant; and , are the standard and accelerated operating temperatures in Kelvin, respectively. Therefore, the 120 h high-temperature operation is equivalent to approximately 4700 h under standard conditions. Furthermore, the temperature cycling accelerated failures induced by thermal shock stress. Under normal operating conditions, the duration of a single imaging mission is approximately 10 min, with a temperature rise rate in the satellite’s image processor area of about 1 °C per minute. In contrast, during the test, the temperature change rate was 4.5 °C per minute, reaching a maximum of 42.5 °C and a minimum of −2.5 °C. Thus, according to the Coffin-Manson Model, the acceleration factor is given by

where the constant exponents are referenced from [54], and and represent the temperature change range and rate, respectively. Consequently, the 9.3 h of temperature cycling is equivalent to approximately 2200 h under standard conditions. Finally, neglecting the potential acceleration effect on SSD failures from the 0 °C low-temperature exposure in this test setup, the operational duration under those conditions totals 104 h. Thus, under the combined thermal and thermal shock stresses, this test is equivalent to a lifespan of approximately 7000 h. Under the right-censored test condition, assuming a constant failure rate , the probability of observing zero failures in the samples follows the Poisson process

where is the number of failures, is the total number of samples, and h is the total equivalent test duration. At a 95% confidence level, we have

so could be obtained. This result implies that, under random internal and external stresses and adopting a 5% failure risk criterion (i.e., a reliability of 0.95), the minimum expected lifetime of the SSDs is approximately 5.7 years.

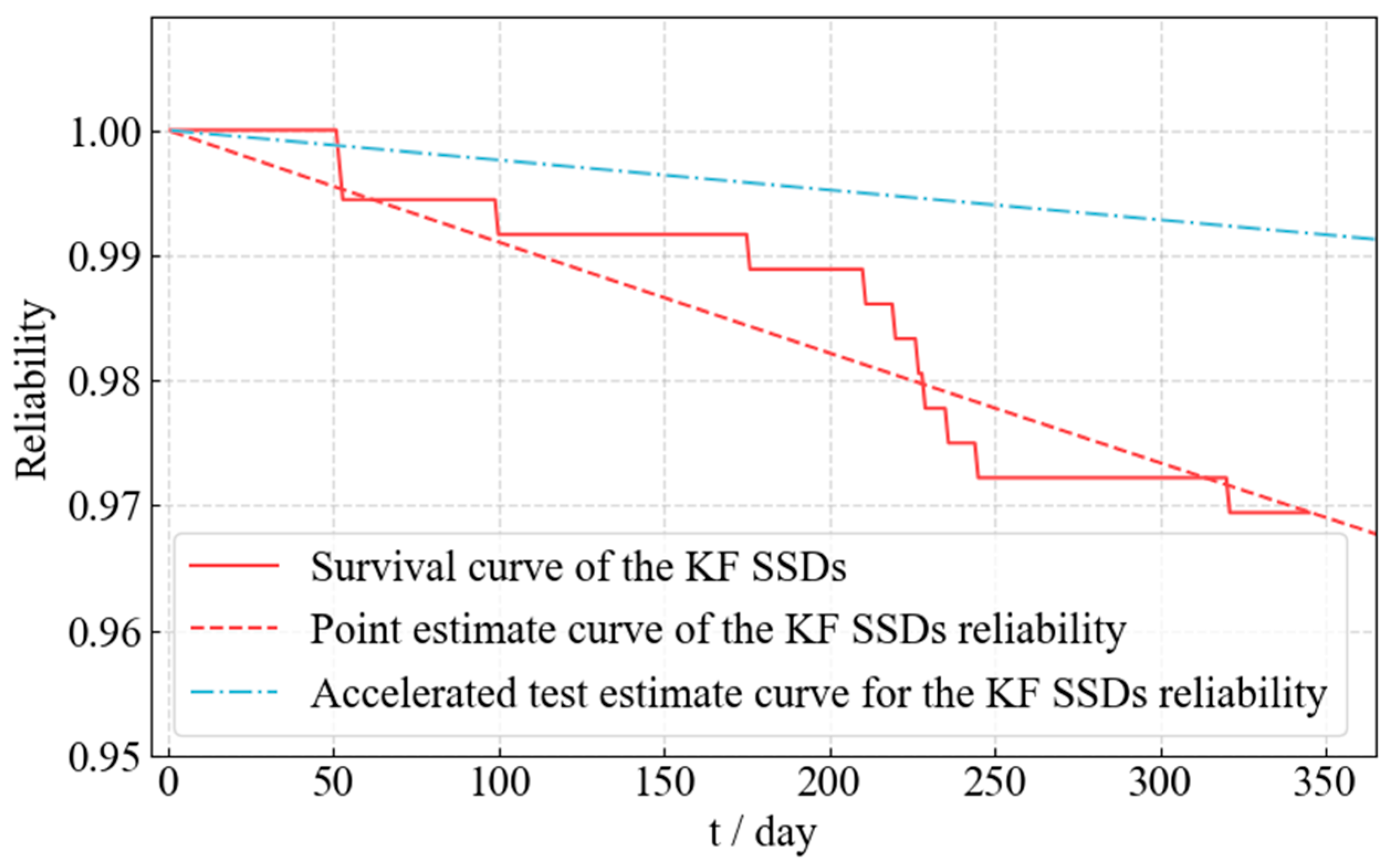

On the other hand, the on-orbit operational conditions for the COTS hard drives spanned approximately one year—from the start of routine operations to the end of the statistical window for failure data. During this period, 10 failures occurred. The likelihood function for the failure rate is given by

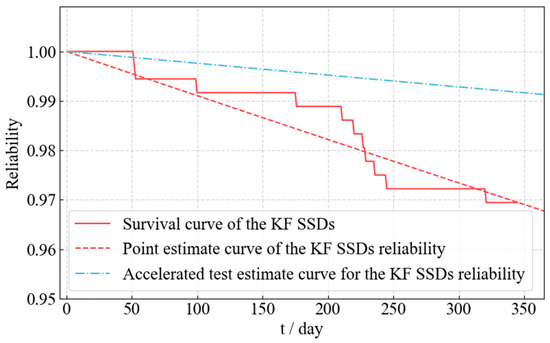

where is the number of surviving samples, is the survival time of each sample, and is the censoring time. Based on the failure data provided in Section 2.3, the maximum likelihood estimate for the random failure rate of the SSDs is . This result is markedly different from the reliability conclusion derived from ground testing, as shown in Figure 4. Therefore, beyond failures attributable to the natural lifespan degradation of the SSDs, other factors must be contributing to the observed failures. To determine the root cause of these failures, investigation into other environmental stresses is essential.

Figure 4.

The survival curve of KF SSD, the point estimate curve of its reliability under the assumption of a constant failure rate, and the lower bound curve of the reliability interval estimate based on ground testing. Evidently, the actual on-orbit survival performance of the SSD falls far short of that observed during ground tests.

4.2. Analysis of On-Orbit Operating Conditions

To analyze instantaneous failures caused by factors such as thermal shock, electrical shock, and high-energy particle impact, telemetry data from the period surrounding SSD failures was examined. The raw format of the telemetry data is shown in Table 2. Using specific decoding rules, this data was converted into corresponding actual physical values. The telemetry data has a frequency of one record every 4 s, covering a total of 5706 operational missions, amounting to approximately 1.1 million data records. Each record includes 23 sensor data items, including time, thermal status, electrical status, SSD status, and orbital status. The overall dataset can be represented as

where denotes the length of i-th telemetry data for each mission varying from tens to hundreds of records, = 5706 is the total number of missions, and = 23 is the number of sensor parameters.

Table 2.

A partial display of telemetry raw data during periods of SSD failure, totaling approximately 1.1 million entries. Due to varying mission durations, the length of telemetry data corresponding to each mission ID differs.

We converted the 19 thermal and electrical status time-series data items from the telemetry data of each operational mission into feature data [55] to align the data dimensions across different missions. Specifically, for any finite-length time-series data, a feature extraction mapping

is defined to transform the time-series dataset D into a feature dataset , which is then normalized to standardize each feature. In the equation above, represents the feature dimension for a single sensor’s time-series data, including metrics such as global average energy, the sum of absolute first-order differences, local linear regression coefficients, and autocorrelation coefficients. = 19 denotes the number of sensor data items related to electrical and thermal status. Additionally, the feature dataset has a corresponding state dataset , indicating whether the SSD was damaged during the mission. Subsequently, we proceeded to explore the relationships between the thermal/electrical feature data X and the SSD state data Y. We attempted to employ directed acyclic graphs [56] to explore causal relationships within the data by optimizing

In this formulation, BCE denotes the binary cross-entropy loss, is the sigmoid activation function, represents the regression coefficient matrix, whose structure ensures no outgoing edges from Y to X in the causal graph, and is a bias constant. The optimization objective comprises three terms: (1) the fidelity term , which aims to uncover the causal influence of X itself on Y; (2) the sparsity regularization term , which enforces sparsity in the causal graph to mitigate noise interference; and (3) the acyclicity regularization term , which ensures that the learned causal graph contains no cyclic dependencies. Under strict sparsity and acyclicity constraints, the objective was optimized using the Adam algorithm [57]. However, the resulting model exhibited poor generalization. On one hand, the discovered causal relationships appeared to be dominated by noise. On the other hand, the outcome suggested that the posterior distribution of Y given the observed features X remained close to its prior distribution, indicating potential independence between X and Y [58]. To strengthen confidence in the conclusion of no causal relationship, we applied the Hilbert-Schmidt Independence Criterion (HSIC) test [59]. Each feature and the SSD state data were separately mapped into Reproducing Kernel Hilbert Spaces (RKHS) using a Gaussian kernel and a Kronecker delta function, respectively, and the distance between their distributions was measured. The results of the independence test consistently indicated a high degree of independence between the operational condition features and the SSD state data. Finally, we attempted to cluster the feature data X using the unsupervised DBSCAN algorithm [60] to identify anomalous operating conditions. We then manually examined whether any correlation existed between these anomalies and SSD failure states. Several mission profiles deviating from the majority of standard operational conditions were identified—for instance, anomalies in telemetry data caused by bit errors during downlink transmission to ground stations. Despite the presence of such anomalous conditions, none coincided with missions in which SSD failures occurred. Based on this analysis, we can reasonably conclude with high confidence that the SSD failures are unlikely to have originated from thermal or electrical stress shocks.

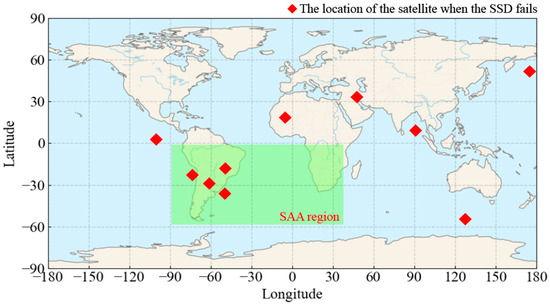

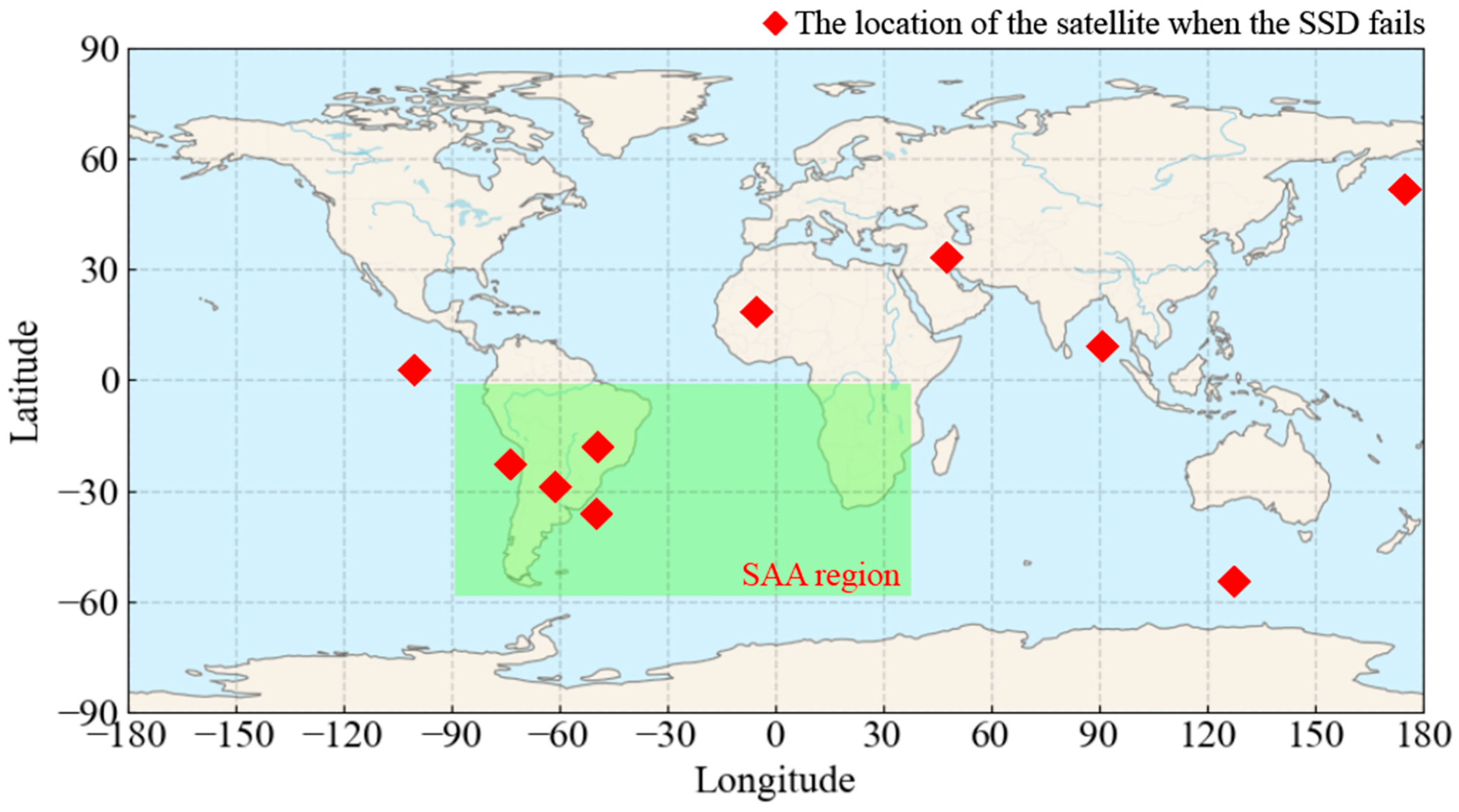

On the other hand, since the satellite is not equipped with sensors to detect high-energy particle radiation, it is impossible to directly analyze the satellite’s high-energy radiation conditions during operation. Considering the inhomogeneity of Earth’s radiation field, the relationship between SSD failure occurrences and orbital position can be investigated. From each sample in the total dataset D, the SSD status and orbital position during a mission are extracted to form a new subset

where () represents the latitude and longitude where the i-th mission was executed, and indicates whether an SSD failure occurred during that mission. Plotting this data on a map reveals the failure distribution, as shown in Figure 5. Visually, SSD failures are significantly concentrated within the SAA radiation region. Using the Mercator projection, we employed the minimum path distance between any two spatial points as the distance metric and adopted the highest silhouette coefficient as the clustering objective when applying DBSCAN [60] for clustering. This approach allowed the failure points within the SAA region to be clustered into an SAA failure cluster, while the remaining failure points were labeled as noise without cluster affiliation. By treating the other failure points as a single cluster, we calculated an average silhouette coefficient of 0.64 for the SAA cluster. Given the small sample size, this value indicates satisfactory clustering performance, demonstrating the spatial concentration of failure points within the SAA region. Therefore, we conduct a hypothesis test analysis. First, due to the characteristics of the satellite’s orbit—each orbital pass traverses the polar regions while the longitude of the path between the poles changes uniformly—and given that the satellite moves at a nearly constant velocity for the vast majority of the time, its probability of being at any given coordinate in a Mercator projection is essentially uniform. If SSD failures are unaffected by radiation, the expected ratio of failures within the radiation region to failures elsewhere should equal the ratio of the area of the radiation region to the total area. Consequently, we formulate the null hypothesis H0: The spatial distribution of SSD failures is independent of the spatial distribution of the radiation region. The alternative hypothesis H1 is that there is a significant correlation between the two spatial distributions. Under H0, the number of failure locations falling within the radiation region follows the binomial distribution

where = 10 is the total number of failure samples, and p = 0.1 is the orbit proportion of the radiation region [40]. Based on this model and the observed data, the p-value for H0—the probability of observing at least 4 failure samples within the radiation region—is calculated to be

At the 95% significance level, there is sufficient evidence to reject the H0 hypothesis that the spatial distribution of SSD failures is independent of the spatial distribution of the radiation region. This indicates that the observed significant clustering of failure points strongly supports the alternative hypothesis H1 that SSD failures are associated with the radiation environment.

Figure 5.

Locations of SSD failures during satellite mission execution. The SSD failures are notably concentrated within the SAA region, particularly over the area of Africa where the magnetic field is weakest.

Figure 5.

Locations of SSD failures during satellite mission execution. The SSD failures are notably concentrated within the SAA region, particularly over the area of Africa where the magnetic field is weakest.

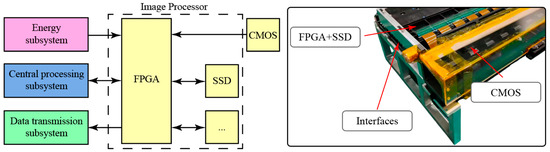

4.3. Failure Recurrence Experiments

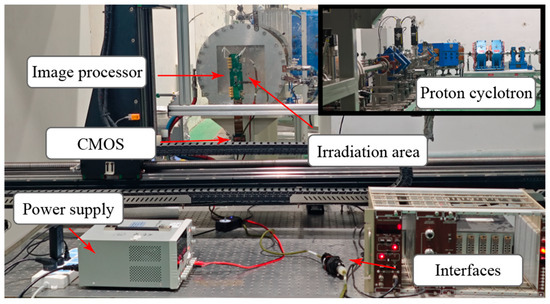

Based on the analysis in Section 4.2 and the fact that proton flux constitutes the most significant component of high-energy particle radiation affecting satellites in LEO, this study conducted proton irradiation experiments on operational SSDs using a 50 MeV proton cyclotron to simulate the effects of high-energy protons in the LEO environment. The experimental setup is illustrated in Figure 6. The SSD was mounted on an FPGA controller, and both were connected to a computer. The computer simulated the central processing subsystem by sending operational commands to the FPGA. During proton irradiation, the SSD operated under conditions analogous to on-orbit operation: the central computer sequentially sent the FPGA commands for drive selection, power-on, imaging, and data storage. The FPGA executed these commands in order, writing data from the CMOS sensor into the SSD. Once the SSD storage capacity fell below a low-capacity threshold, the central computer commanded the FPGA to power down the drive, thereby completing one storage task. The SSD was then formatted to erase all data, after which the storage task cycle was repeated until the irradiation experiment finished.

Figure 6.

High-energy proton irradiation experiment setup for the SSD.

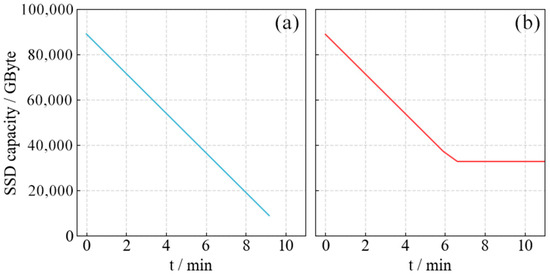

During the experiment, the storage capacity of the SSD could be queried via telemetry commands sent through the communication interface. First, under non-irradiated conditions, three consecutive storage tasks were performed. The change in SSD capacity remained essentially consistent across all three tasks, as shown in Figure 7a. As real-time image data was stored, the SSD capacity decreased at a constant write speed of 145 MByte/s. Under high-energy proton irradiation, the SSD operated normally for 90 min. At the next storage task, a failure occurred, as shown in Figure 7b. In this task, the write speed remained normal for the first 395 s. Between 395 s and 400 s, the write speed dropped to 27 MByte/s. After 400 s, the SSD became unable to write data. Following the experiment, multiple attempts to re-execute the storage task resulted in a condition identical to the on-orbit failure: after power-up, the available capacity was reported as 0, and this condition could not be recovered through self-annealing. After thorough investigation, the root cause of the failure in this SSD sample was identified as physical damage to the disk sector containing the FAT. This damage prevented the SSD system information from being recognized. After the FPGA driver rewrote the FAT information to a physically undamaged sector manually and removed the bad blocks from the storage capacity mapping, the SSD resumed normal operation.

Figure 7.

As the storage task proceeds, the remaining capacity curves of the hard drive under non-irradiated and irradiated conditions are shown in (a) and (b), respectively.

5. Conclusions and Management Decisions

With the shift toward low-cost and rapid-development satellite projects in the commercial field, exemplified by LEO communication and remote sensing constellations, the application of COTS components across various commercial satellite platforms has become increasingly widespread. However, as COTS devices are not inherently designed for harsh space environments, their inherent reliability issues have become a core bottleneck limiting their extensive use in critical missions. This paper conducted a practical mission deployment of spaceborne COTS storage devices, including (1) comprehensive consideration of the technical specifications and reliability of satellites carrying COTS storage devices, implementing protective measures and environmental adaptation designs; (2) conducting ground testing of COTS storage devices and, upon acceptance, launching them into orbit to execute Earth imaging missions, recording the on-orbit performance of the COTS storage devices. Over a nearly one-year operational period, approximately 3% of the hard drives failed, yet the spaceborne storage system itself experienced no failures due to the multi-parallel redundancy strategy; (3) analyzing ground test data and on-orbit data to identify the causes of COTS storage device failures and reproduce the failure modes. Thanks to the multi-parallel redundancy strategy, while the reliability of an individual hard drive at the one-year mark was 0.9678, the reliability of the overall spaceborne storage system remained close to 1. Building on this, and disregarding the natural wear-out of the hard drives, the spaceborne storage system can still maintain a high reliability of 0.9877 by the end of the satellite’s 8-year design life. Although this does not meet the traditional reliability requirements allocated to spaceborne storage systems, from the perspective of exploring the practical application of COTS, this conclusion remains sufficiently optimistic. Furthermore, ground-based repair commands can be attempted to recover failed hard drives at the cost of temporarily reducing the availability of the satellite constellation.

The aforementioned practical experience and analysis also yield several general conclusions: (1) The batch application of COTS components in commercial spacecraft is feasible; (2) COTS components remain significantly susceptible to radiation effects, making necessary reliability protection measures essential during spacecraft design; (3) Through rational redundancy design, the on-orbit survivability of storage systems employing COTS components can be significantly enhanced, effectively balancing cost and reliability. Furthermore, the risks associated with COTS failures remain severe. This practice informs subsequent quality management decisions for constellation development: (1) When employing spaceborne COTS components, it is crucial to thoroughly identify the failure risks posed by the space environment and implement essential reliability design and protection measures against high-risk high-energy particle radiation effects. Based on the reliability data obtained, the required number of backup storage units can be quantified in subsequent models to ensure the system reliability meets quality requirements. (2) Different COTS component models exhibit potentially significant variations in design and manufacturing processes. Therefore, we have incorporated COTS components into the aerospace unit maturity grading and management program. It stipulates that products that have undergone sufficient ground verification and reached a certain maturity level can be used in formal flight models, and only those that have undergone sufficient on-orbit flight verification and reached a higher maturity level are qualified for use in mass-produced satellite models. The principle of “prioritizing products with higher maturity levels” is enforced to ensure the selected COTS component models have undergone adequate screening and qualification. (3) Establishing a continuous on-orbit data—ground analysis—design optimization feedback mechanism, utilizing actual flight data as a basis for improving subsequent satellite system development, facilitates reliability growth. We have established an aerospace product maturity and heritage-level database to systematically accumulate lifespan and failure data. This provides data support for satellite lifetime estimation and design optimization, addressing the challenge of high failure rates inherent to COTS components while leveraging their cost advantages, thereby controlling satellite failure risks. Through the above work, this paper has completed a closed-loop management process encompassing satellite development and design, on-orbit practice and problem reporting, problem analysis and reproduction, and the improvement of management decisions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.Z. and J.P.; Methodology, J.P.; Software, J.P.; Validation, H.S.; Formal Analysis, J.P.; Investigation, C.Z., J.P. and H.S.; Resources, C.Z. and H.S.; Data Curation, J.P.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, C.Z., J.P. and H.S.; Writing—Review and Editing, C.Z., X.L., K.X., Y.Z. and L.Z.; Visualization, J.P.; Supervision, K.X., Y.Z. and L.Z.; Project Administration, X.L.; Funding Acquisition, L.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Department of Science and Technology of Jilin Province (20230201023GX).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because of trade secrets.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Chunjuan Zhao, Jianan Pan, Hongwei Sun, Xiaoming Li, Kai Xu and Lei Zhang were employed by the company Chang Guang Satellite Technology Co., Ltd. The remaining author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LEO | Low Earth orbit |

| COTS | Commercial off-the-shelf |

| SEE | Single-event effects |

| TID | Total ionizing dose |

| DD | Displacement damage |

| SEU | Single-event upsets |

| SEL | Single-event latch-ups |

| TMR | Triple modular redundancy |

| TNU | Triple-node upsets |

| SET | Single-event transients |

| CNES | National Centre for Space Studies |

| SSDs | Solid State Drives |

| FAT | File Allocation Table |

| MLC | Multi-level cell |

| FN-t | Fowler-Nordheim tunneling |

| HSIC | Hilbert-Schmidt Independence Criterion |

| RKHS | Reproducing Kernel Hilbert Spaces |

| SAA | South Atlantic Anomaly |

References

- Zhang, J.; Cai, Y.; Xue, C.; Xue, Z.; Cai, H. LEO mega constellations: Review of development, impact, surveillance, and governance. Space Sci. Technol. 2022, 2022, 9865174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, Y.; Zhang, E.; Zhang, W.; Ma, H.; Wu, T. A survey on the development of low-orbit mega-constellation and its TT&C methods. In Proceedings of the 2022 5th International Conference on Information Communication and Signal Processing (ICICSP), Shenzhen, China, 26–28 November 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 324–332. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, P.; Tan, T.; Yu, Y. Enlightenment for China’s LEO Internet Satellite Industry from Typical Development Model of European Commercial Satellite. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Symposium on Networks, Computers and Communications (ISNCC), Shenzhen, China, 19–22 July 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Torchiano, M.; Jaccheri, L.; Sørensen, C.F.; Wang, A.I. COTS products characterization. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Software Engineering and Knowledge Engineering, Larnaca, Cyprus, 22–24 August 2022; pp. 335–338. [Google Scholar]

- Adamo, F.; Simoncini, G.; Pauletto, S.; Carrato, S.; Gregorio, A. Design of a 17.3–21.2 GHz SATCOM Upconverter Based on COTS with Low Spurious Emission. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE Space Hardware and Radio Conference (SHaRC), San Juan, PR, USA, 19–22 January 2025; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 12–15. [Google Scholar]

- Lahti, D.; Grisbeck, G.; Bolton, P. ISC (Integrated Spacecraft Computer) Case Study of a Proven, Viable Approach to Using COTS in Spaceborne Computer Systems; Small Satellite: Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Casado, P.; Blanes, J.M.; Garrigós, A.; Marroquí, D.; Torres, C. COTS Battery Charge Equalizer for Small Satellite Applications. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poivey, C. RADECS Short Course Section 4 Radiation Hardness Assurance (RHA) for Space Systems. In RADECS 2003; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- George, J.S. An overview of radiation effects in electronics. In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on the Application of Accelerators in Research and Industry, Grapevine, TX, USA, 12–17 August 2018; AIP Publishing: Melville, NY, USA, 2019; Volume 2160, p. 060002. [Google Scholar]

- Fleetwood, D.M. Radiation effects in a post-Moore world. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2021, 68, 509–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecoffet, R. Overview of in-orbit radiation induced spacecraft anomalies. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2013, 60, 1791–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, A.H. Radiation effects in optoelectronic devices. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2013, 60, 2054–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetti, G.; Campiti, G.; Tagliente, M.; Ciminelli, C. Cots devices for space missions in leo. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 76478–76514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin-Hong, L.; Feng-Qi, Z.; Hong-Xia, G.; Hui, Z.; Li-Sang, Z.; Dong-Mei, J.; Chen, S.; Ding, G.; Hajdas, W. Single-event cluster multibit upsets due to localized latch-up in a 90 nm COTS SRAM containing SEL mitigation design. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2014, 61, 1918–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattos, A.M.; Santos, D.A.; Luza, L.M.; Gupta, V.; Borel, T.; Dilillo, L. Investigation on radiation-induced latch-ups in COTS SRAM memories onboard PROBA-V. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2024, 71, 1614–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzel, R.; Özyildirim, A. A study on the local shielding protection of electronic components in space radiation environment. In Proceedings of the 2017 8th International Conference on Recent Advances in Space Technologies (RAST), Istanbul, Turkey, 19–22 June 2017; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 295–299. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, A.; Feng, X.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, H.; Cui, J.; Ying, Z.; Girard, P.; Wen, X. HITTSFL: Design of a cost-effective HIS-Insensitive TNU-Tolerant and SET-Filterable latch for safety-critical applications. In Proceedings of the 2020 57th ACM/IEEE Design Automation Conference (DAC), San Francisco, CA, USA, 19–23 July 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Lu, J.; Zhao, Q.; Hao, L.; Peng, C.; Lu, W.; Lin, Z.; et al. Novel radiation-hardened-by-design (RHBD) 14T memory cell for aerospace applications in 65 nm CMOS technology. Microelectron. J. 2023, 141, 105954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, A.C.; Silveira, L.F.; Kreutz, M.E.; Dias, S.M. A Parity-Based Dual Modular Redundancy Approach for the Reliability of Data Transmission in Nanosatellite’s Onboard Processing. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 90815–90828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pignol, M. DMT and DT2: Two fault-tolerant architectures developed by CNES for COTS-based spacecraft supercomputers. In Proceedings of the 12th IEEE International On-Line Testing Symposium (IOLTS’06), Lake of Como, Italy, 10–12 July 2006; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2006; p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, L. Enhancing the Reliability of AD936x-Based SDRs for Aerospace Applications via Active Register Scrubbing and Autonomous Fault Recovery. Sensors 2025, 25, 6801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyke, J.C.; Christodoulou, C.G.; Vera, G.A.; Edwards, A.H. An introduction to reconfigurable systems. Proc. IEEE 2015, 103, 291–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, H. Radiation effects in reconfigurable FPGAs. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 2017, 32, 044001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, J.M.; Roibás-Millán, E. Agile methodologies applied to Integrated Concurrent Engineering for spacecraft design. Res. Eng. Des. 2021, 32, 431–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, R.C.; Kourtis, G.; Dennis, L.A.; Dixon, C.; Farrell, M.; Fisher, M.; Webster, M. A review of verification and validation for space autonomous systems. Curr. Robot. Rep. 2021, 2, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkowski, T.; Saigne, F.; Wang, P.X. Radiation qualification by means of the system-level testing: Opportunities and limitations. Electronics 2022, 11, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, K.O.N.G.; Yan, L.I.; Duanpeng, H.E.; Yang, W.A.N.G.; Jingjing, Z.H.A.N.G.; Jiao, L.I.; Botian, L.I.; Bing, W.U. Radiation-resistant materials in space and their reliability evaluation technology: A review. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2025; Volume 3093, p. 012012. [Google Scholar]

- Iucci, N.; Levitin, A.E.; Belov, A.V.; Eroshenko, E.A.; Ptitsyna, N.G.; Villoresi, G.; Chizhenkov, G.V.; Dorman, L.I.; Gromova, L.I.; Parisi, M.; et al. Space weather conditions and spacecraft anomalies in different orbits. Space Weather 2005, 3, 01001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meseguer, J.; Pérez-Grande, I.; Sanz-Andrés, A. Spacecraft Thermal Control; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gueymard, C.A. A reevaluation of the solar constant based on a 42-year total solar irradiance time series and a reconciliation of spaceborne observations. Sol. Energy 2018, 168, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Bárcena, D.; Bermejo-Ballesteros, J.; Pérez-Grande, I.; Sanz-Andrés, Á. Selection of time-dependent worst-case thermal environmental conditions for Low Earth Orbit spacecrafts. Adv. Space Res. 2022, 70, 1847–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Wang, X.; Feng, N.; Tang, X.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, G. Research on the Charging Process of LEO Spacecraft Surface Materials Based on Particle Transport Equations; IEEE Access: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, P.C. Characteristics of spacecraft charging in low Earth orbit. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2012, 117, A07308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodeau, M. Observation of sustained arc circuit failure on solar array backside in low earth orbit. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2015, 43, 2961–2974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fede, S.; Banninthaya, A.; Huang, Z.; Hu, Y.; Elhadidi, B.; Magarotto, M.; Chan, W.L. Ionospheric plasma drag on small satellites in low-earth orbit. Acta Astronaut. 2025, 239, 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Gao, C.; Yuan, L.; Guo, P.; Calabia, A.; Ruan, H.; Luo, P. Long-term variations of plasmaspheric total electron content from topside GPS observations on LEO satellites. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdarie, S.; Xapsos, M. The near-earth space radiation environment. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2008, 55, 1810–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surkov, V.V.; Mozgov, K.S. Electrification of Dielectric Satellites under the Influence of Electron Flows of the Earth’s Radiation Belts. Geomagn. Aeron. 2021, 61, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingos, J.; Jault, D.; Pais, M.A.; Mandea, M. The South Atlantic Anomaly throughout the solar cycle. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2017, 473, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasuddin, K.A.; Abdullah, M.; Abdul Hamid, N.S. Characterization of the South Atlantic anomaly. Nonlinear Process. Geophys. 2019, 26, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabiano, M.; Furano, G. NAND flash storage technology for mission-critical space applications. IEEE Aerosp. Electron. Syst. Mag. 2013, 28, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, K.; Tanaka, T.; Tanzawa, T. A multipage cell architecture for high-speed programming multilevel NAND flash memories. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2002, 33, 1228–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, H.; Kido, M.; Yahashi, K.; Oomura, M.; Katsumata, R.; Kito, M.; Fukuzumi, Y.; Sato, M.; Nagata, Y.; Matsuoka, Y.; et al. Bit cost scalable technology with punch and plug process for ultra high density flash memory. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE Symposium on VLSI Technology, Kyoto, Japan, 12–14 June 2007; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 14–15. [Google Scholar]

- Aritome, S.; Shirota, R.; Hemink, G.; Endoh, T.; Masuoka, F. Reliability issues of flash memory cells. Proc. IEEE 1993, 81, 776–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutet, J.; Marc, F.; Dozolme, F.; Guétard, R.; Janvresse, A.; Lebossé, P.; Pastre, A.; Clement, J.C. Influence of temperature of storage, write and read operations on multiple level cells NAND flash memories. Microelectron. Reliab. 2018, 88, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Seo, J.; Nam, J.; Kim, Y.; Song, K.W.; Song, J.H.; Choi, W.Y. Electric field impact on lateral charge diffusivity in charge trapping 3D NAND flash memory. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Reliability Physics Symposium (IRPS), Dallas, TX, USA, 27–31 March 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. P29-1–P29-5. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D.; Wilcox, E.; Ladbury, R.L.; Seidleck, C.; Kim, H.; Phan, A.; LaBel, K.A. Heavy ion and proton-induced single event upset characteristics of a 3-D NAND flash memory. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2017, 65, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srour, J.R.; Palko, J.W. Displacement damage effects in irradiated semiconductor devices. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2013, 60, 1740–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, K.; Kawamoto, Y.; Nishiyama, H.; Kato, N.; Toyoshima, M. An efficient utilization of intermittent surface–satellite optical links by using mass storage device embedded in satellites. Perform. Eval. 2015, 87, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhail, M.; Harp, T.; Bridwell, J.; Kuhn, P.J. Effects of Fowler Nordheim tunneling stress vs. channel hot electron stress on data retention characteristics of floating gate non-volatile memories. In Proceedings of the 2002 IEEE International Reliability Physics Symposium. Proceedings. 40th Annual (Cat. No. 02CH37320), Dallas, TX, USA, 7–11 April 2002; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 439–440. [Google Scholar]

- Vesely, W.E.; Goldberg, F.F.; Roberts, N.H.; Haasl, D.F. Fault Tree Handbook; (No. NUREG0492); Nuclear Regulatory Commission: Washington, DC, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Lakshminarayanan, V.; Sriraam, N. The effect of temperature on the reliability of electronic components. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Electronics, Computing and Communication Technologies (CONECCT), Bangalore, India, 6–7 January 2014; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.; Kang, M.; Seo, S.; Li, D.H.; Kim, J.; Shin, H. Analysis of failure mechanisms and extraction of activation energies Ea in 21-nm NAND flash cells. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2012, 34, 48–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H. Accelerated temperature cycle test and Coffin-Manson model for electronic packaging. In Proceedings of the Annual Reliability and Maintainability Symposium, 2005. Proceedings, Alexandria, VA, USA, 24–27 January 2005; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 556–560. [Google Scholar]

- Christ, M.; Braun, N.; Neuffer, J.; Kempa-Liehr, A.W. Time series feature extraction on basis of scalable hypothesis tests (tsfresh–a python package). Neurocomputing 2018, 307, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Aragam, B.; Ravikumar, P.K.; Xing, E.P. Dags with no tears: Continuous optimization for structure learning. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2018, 31, 9492–9503. [Google Scholar]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Learning Representations, San Diego, CA, USA, 7–9 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Duda, R.O.; Hart, P.E. Pattern Classification; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gretton, A.; Bousquet, O.; Smola, A.; Schölkopf, B. Measuring statistical dependence with Hilbert-Schmidt norms. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Algorithmic Learning Theory, Singapore, 8–11 October 2005; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 63–77. [Google Scholar]

- Ester, M.; Kriegel, H.P.; Sander, J.; Xu, X. A density-based algorithm for discovering clusters in large spatial databases with noise. In Kdd; University of Munich: Munich, Germany, 1996; Volume 96, pp. 226–231. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.