Abstract

Debate persists over whether classical econometric or modern machine learning (ML) approaches provide superior forecasts for volatile monthly price series. Despite extensive research, no systematic cross-domain comparison exists to guide model selection across diverse asset types. In this study, we compare traditional econometric models with classical ML baselines and hybrid approaches across financial assets, futures, commodities, and market index domains. Universal Python-based forecasting tools include month-end preprocessing, automated ARIMA order selection, Fourier terms for seasonality, circular terms, and ML frameworks for forecasting and residual corrections. Performance is assessed via anchored rolling-origin backtests with expanding windows and a fixed 12-month horizon. MAPE comparisons show that ARIMA-based models provide stable, transparent benchmarks but often fail to capture the nonlinear structure of high-volatility series. ML tools can enhance accuracy in these cases, but they are susceptible to stability and overfitting on monthly histories. The most accurate and reliable forecasts come from models that combine ARIMA-based methods with Fourier transformation and a slight enhancement using machine learning residual correction. ARIMA-based approaches achieve about 30% lower forecast errors than pure ML (18.5% vs. 26.2% average MAPE and 11.6% vs. 16.8% median MAPE), with hybrid models offering only marginal gains (0.1 pp median improvement) at significantly higher computational cost. This work demonstrates the domain-specific nature of model performance, clarifying when hybridization is effective and providing reproducible Python pipelines suited for economic security applications.

1. Introduction

Accurately forecasting prices in global markets is essential to economic security, e.g., for international business. Ianioglo and Polajeva (2016) emphasize that most definitions of enterprise economic security highlight resilience to external and internal risks and threats. From this perspective, forecasting assumes a central role, since ISO 31000 (2018) defines risk as “uncertainty that affects objectives.” Thus, robust forecasting can be understood as a managed reduction of uncertainty surrounding the key factors that determine a firm’s performance indicators. Hence, forecasting accuracy is crucial to decision-making and defining trading and purchasing business strategies, risk management, economic security, etc. Despite progress in statistical and computational methods and tools, valuable prediction remains challenging because of financial and commodity markets’ inherent complexity and volatility. Classical econometric models, such as regression, ARIMA, and GARCH, offer statistically interpretable frameworks for capturing linear trends and volatility (Hyndman & Athanasopoulos, 2018; Min et al., 2025; Baranovskyi et al., 2021; Sen & Mehtab, 2021; Karamolegkos & Koulouriotis, 2025; Wang et al., 2023). However, their rigidity in handling non-linear dynamics, non-stationary data, and abrupt regime shifts, which are frequent in assets such as cryptocurrencies and features (Lago et al., 2021; Bitto et al., 2022), as well as iron, crude oil, natural gas, electricity, and wheat, constrains their effectiveness in modern, fast-moving markets.

Machine learning (ML) methods, like learning models such as Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) and Support Vector Machines (SVM), long short-term memory (LSTM) networks, or Gradient Boosting Models (GBMs), are used to define complex temporal and behavioral dependencies. However, because they often operate as “black boxes,” their interpretability is too low (Lago et al., 2021; Demirel et al., 2021; Ding et al., 2022).

This gap can be bridged by contrasting paradigms via combining the explanatory power of classical econometrics with the adaptive capabilities of ML, supported by the extensive Python programming ecosystem. Developing a means of applying the hybrid frameworks and analytical programming tools, such as Fourier-SARIMA-ML or ARIMA + Prophet, thereby integrating seasonal decomposition with deep learning to capture multi-frequency patterns and market volatility, may satisfy the requirements for valuable prediction and decision support (Sherly et al., 2025; Karamolegkos & Koulouriotis, 2025). Furthermore, advanced Python libraries can improve forecasting workflows by ensuring reproducibility and scalability, ranging from automated feature engineering (Horn et al., 2019) to cross-validation and hyperparameter optimization (Passos & Mishra, 2022).

In this study, we compare classical ARIMA models, ML methods (GBM, Random Forest, SVM, etc.), and hybrid approaches across different market asset types, including currencies, stocks, and commodities, offering domain-specific model selection recommendations. We test various hypotheses about forecasting model combinations and determine which combination best captures market price volatility, seasonality, and growth indices. Python-based workflows shorten development time without sacrificing predictive accuracy and forecast robustness.

The central scientific problem addressed in this study is the compromise between interpretability and efficiency: although classical econometric models provide transparent statistical inference, they can miss complex nonlinear dynamics, while ML methods capture these dynamics in exchange for transparency and higher computational costs. This study systemically evaluates how econometric and ML methods can be combined to improve forecasting reliability. To this end, various modern approaches are developed based on Python programming language tools and various market datasets.

2. Research Background

Many early and recent publications address improving forecast efficiency. We review only a few of these studies based on recent papers indexed in international scientific databases, using the keywords econometrics, forecasting, commodity prices, financial markets, stocks, and Python. The results highlight relevant studies that have made significant contributions to solving the identified problem.

Classical econometric models like ARIMA and its various interpretations remain fundamental for price forecasting because of their transparency and ability to model linear trends, seasonality, and volatility. Statistical forecasting indicates that ARIMA and exponential smoothing serve as essential benchmarks for more advanced models (Hyndman & Athanasopoulos, 2018). For example, Lago et al. (2021) thoroughly reviewed electricity price forecasting and found that ARIMA effectively captures seasonal price patterns. Similarly, Bitto et al. (2022) applied ARIMA models in cryptocurrency markets, demonstrating decent short-term predictive performance while acknowledging challenges in modeling the high volatility of crypto assets. Stier et al. (2021) introduced a multiresolution framework combining wavelet decomposition with an ARIMA-based approach to handle complex seasonal structures, thereby improving prediction accuracy for stocks and commodities by accounting for multiple seasonal cycles. However, classical models struggle with non-stationary data and nonlinear shifts. In volatility modeling, Sen and Mehtab (2021) showed that GARCH models capture time-varying volatility in Indian equity markets but cannot easily incorporate exogenous factors such as macroeconomic indicators. Researchers have thus explored extensions of classical methods to improve adaptability. For example, Mák (2023) used Gaussian Mixture Regression to model seasonal uncertainty in electricity loads, effectively managing heteroscedasticity that would be missed by standard ARIMA models. These efforts highlight the need to enhance traditional econometric models with modern methods and analytical tools to increase their flexibility and accuracy.

ML and deep learning methods have received attention for their ability to model nonlinear patterns and complex temporal dependencies in financial data such as stocks, forex, and cryptocurrencies. Many studies have shown that recurrent neural networks, especially LSTM models, often outperform traditional models in market forecasting. Demirel et al. (2021) compared various models (ANN, CNN, LSTM, and others) for stock price prediction. They found that LSTM achieved the highest accuracy because of its ability to capture long-term sequential dependencies. Similarly, Ding et al. (2022) demonstrated that an LSTM-based model significantly reduced the RMSE relative to ARIMA when forecasting the Shanghai Stock Exchange 50 Index, highlighting deep learning’s effectiveness for financial time series. In the case of exchange-traded funds, Shih et al. (2024) showed that deep learning models (LSTM and GRU) outperformed the traditional Fama–French three-factor model in predicting ETF returns, successfully capturing nonlinear relationships that the linear factor model could not. However, the high risk of overfitting these models and the need for personalized hyperparameter tuning limit their practical use in decisions related to economic security. Researchers have noted the importance of careful model design and tuning to address these challenges. Pavlatos et al. (2023) optimized an RNN architecture for electrical load forecasting, noting that proper hyperparameter tuning and simpler network structures (e.g., stacked SipleRNN layers) can achieve high accuracy while reducing complexity. Yalcin et al. (2024) offer another perspective by using a convolutional neural network to optimize fuel cell systems; their advanced CNN (featuring 2D and 3D convolution layers) accurately predicted hydrogen yield and gas concentrations, surpassing other AI methods. This shows that deep learning’s ability to capture complex patterns can lead to better forecasts in volatile commodity markets. However, large datasets, proper regularization, and substantial computational resources remain essential for deploying ML in financial forecasting and other practical tasks in which the time series set is not so large.

Hybrid models, which synergize the strengths of classical and ML approaches, may be used to solve these problems. Instead of treating statistical models and ML as mutually exclusive, these frameworks combine them to handle different data patterns. Durairaj and Mohan (2021) developed a hybrid model that integrates ARIMA with a gradient boosting machine, effectively modeling linear components with ARIMA and capturing nonlinear residual patterns with the boosted tree model. This hybrid outperformed each component model alone in financial time series prediction, illustrating the benefit of combining interpretable statistical models with flexible ML algorithms. Similarly, Zakrzewski et al. (2024) introduced ReModels, a Python toolkit implementing quantile regression averaging ensembles for probabilistic energy price forecasting. By adjusting forecasts from multiple models, their approach achieved more robust and accurate predictions across various quantiles. A recent ARIMA–Prophet hybrid (Sherly et al., 2025) formalized hybrid logic with explicit weight selection to minimize MAPE on validation folds. The authors’ reported gains include ≈10% lower MAPE and ≈8% lower RMSE across benchmarked series relative to either base model. These studies validate the hypothesis that hybrid approaches can yield superior accuracy and risk coverage. However, they also reveal a problem: no widely accepted standard workflow exists for building and evaluating hybrid forecasting models. As a result, comparisons across studies, datasets, and models are complex. Thus, economic security and the development of sustainable management solutions remain open challenges.

As ML models become more complex, explainable AI (XAI) frameworks are increasingly important to ensuring transparency in forecasting. In finance, model interpretability is vital for trust and regulatory compliance. Carta et al. (2022) addressed this by developing an XAI tool for statistical arbitrage strategies. They integrated black-box ML models with explainability techniques (such as feature importance and rule extraction) to shed light on a trading algorithm’s decisions. This method elucidates the transparency of the model’s predictions while maintaining comparable performance. The authors implemented their XAI tool in Python, highlighting how contemporary forecasting research can benefit from Python’s extensive ecosystem for developing and interpreting models. With XAI, analysts gain insight into why a model makes specific predictions.

Fuzzy logic models provide an alternative approach that is especially effective for managing uncertainty and vague or imprecise data. Unlike precise statistical models, fuzzy time series methods can incorporate ambiguous information using fuzzy sets and rules. Rubio-León et al. (2023) applied a fuzzy time series model to forecast electricity demand and achieved a lower MAPE than a baseline ARIMA model. A key insight from their study is the importance of correct set weighting—prioritizing more relevant fuzzy sets to generate better inference rules and improve accuracy. This method, which uses Python libraries, demonstrates the potential of fuzzy logic for financial market forecasting, especially when data are noisy or incomplete. The authors show that fuzzy models can handle uncertainty more effectively than traditional models for tasks such as predicting economic indicators and commodity prices.

The Python programming environment has become essential for modern econometric forecasting workflows. Its wide range of libraries, frameworks, and community support enables rapid development, testing, and deployment of forecasting models, as demonstrated by Reis et al. (2022), who created a Python-based microservice framework for energy price prediction. Their system breaks down the forecasting pipeline into services—one using ARIMA for short-term price patterns and another using neural networks for complex trends—enabling scalability and easy maintenance in a PowerTAC wholesale electricity market simulation. Python’s flexibility makes it easy to integrate these components and handle real-time data. Python also facilitates automated feature engineering and hyperparameter tuning. Horn et al. (2019) introduced the AutoFeat library, which automatically generates and selects valuable features from raw data within a scikit-learn pipeline. By decreasing manual feature creation, such tools can enhance model performance with minimal human effort—a benefit when working with large financial datasets with numerous potential predictors. Similarly, Passos and Mishra (2022) offered a tutorial on automated hyperparameter tuning for deep learning models, illustrating how Python frameworks (e.g., Keras Tuner or scikit-optimize) can systematically find the best model settings. Another example is the CovRegpy package by van Jaarsveldt et al. (2024), which implements regularized co-variance regression in Python to improve portfolio risk forecasting. Python is driving innovation in domain-specific forecasting solutions. Sokolovska et al. (2024) described an intelligent forecasting platform for pharmaceutical demand, featuring Python-based AI microservices that dynamically switch between forecasting models. This system constantly increases and improves forecast accuracy by selecting the best model for each scenario. This concept could be applied to financial portfolios or commodity prices. Zherlitsyn (2024) and Timbers et al. (2024) have likewise formalized common Python core workflows for uniform and domain-specific data analysis and forecasting, reflecting a trend toward standardized, open-source practices in finance. The breadth of such libraries and platforms underscores Python’s central role in unifying classical econometrics with advanced ML in research workflows.

Beyond general methodologies, several studies show that it is often necessary to tailor forecasting techniques to domain-specific characteristics. For example, in high-volatility markets, Bitto et al. (2022) demonstrated the promise of ARMA models for predicting cryptocurrency price movements, capturing spectral patterns. Baranovskyi et al. (2021) examined the linkages between cryptocurrency market trends and fundamental economic indicators using correlation and regression analyses, revealing nonlinear relationships between virtual asset prices and macroeconomic variables. Complementing these findings, Lin (2023) applied an LSTM neural network to Bitcoin price prediction and reported improved accuracy over baseline models. Their paper reports an optimized architecture for daily Bitcoin price forecasting, demonstrating that deep learning architectures can handle extreme volatility and noise in crypto markets. However, the robustness of the new data is not as evident. Other challenges arise in macroeconomic policy analysis (with low variance and short time series). Kuzheliev et al. (2020) evaluated the impact of an inflation-targeting regime on Ukraine’s macroeconomic indicators using econometric models. Their study highlighted that under highly volatile economic conditions, forecasting frameworks must be adaptive—static models can falter when policy shifts alter the underlying data patterns.

Meanwhile, Yüksel and Köseoğlu (2022) developed regression models to estimate fuel consumption and emissions from marine diesel generators in the energy and transportation sectors. They achieved remarkably high accuracy in predicting fuel use over multi-year horizons, demonstrating that even physical consumption processes can be reliably forecasted with careful modeling (and tools like Python). Techniques from such engineering applications (e.g., robust regression and trend extrapolation) may be transferable to commodity price forecasting, where supply-and-demand dynamics drive trends. Similarly, Yang et al. (2020) applied regression-based predictive modeling to online marketing, optimizing digital marketing strategies by forecasting consumer response. In the commodity price domain, e.g., iron ore, Wang et al. (2023) showcased a multiple linear regression approach. Although the volatility involved is far from that of stock prices, this example demonstrates the ability of traditional econometrics models to forecast iron ore prices with a high degree of accuracy. In these studies, classical (regression and other statistical) forecasting models were customized to each domain’s unique features, challenges, and managerial goals while leveraging advances in ML and statistics. This underscores the broad applicability of simple forecasting tools, such as marketing analytics, and supports economic decision-making.

Robust results and reproducibility are essential for advancing forecasting research and economic security conditions. Lago et al. (2021) observe that many studies lack rigorous evaluation of the methods for each or a specific dataset. This makes it difficult to objectively determine which methods perform best. To address this, Lago et al. (2021) released an open-access Python toolbox and a set of benchmark datasets to enable researchers to evaluate new models on consistent data and compare results fairly. Similarly, Schratz et al. (2019) emphasize that using appropriate validation techniques can prevent overly optimistic assessments of model performance. These insights underscore the importance of exhaustive, data-specific, rigorous, cross-validated time-series validation based on new forecasting methods and tools.

Given this research background and the requirements of businesses and policymakers, the aim of this study was to build and evaluate a robust, reproducible forecasting toolkit grounded in econometrics and selectively augmented by ML to support economic security decisions on global market prices. Python-based computational statistical methodologies are evaluated to develop adaptive, transparent, and operationally efficient forecasting results. Special attention is paid to the practical domains under economic security conditions, where risks and forecast robustness are essential for commodity markets and decision-making processes.

The scientific hypotheses proposed in this study are as follows:

H1.

ARIMA-based models match or exceed standalone ML models in 12-month forecast accuracy and robustness in selected domains.

H2.

Pure ML models underperform relative to ARIMA-based approaches in both accuracy and robustness when forecasting volatile or short-history assets.

Another core aspect of this research’s reproducibility is the use of standardized open data sources and Python 3.12.9 analytical and forecasting tools (pandas v2.3.3, NumPy v1.26.4, Statsmodels v0.14.5, SciPy v1.16.1, pmdarima v2.1.1, Scikit-learn v1.7.2, XGBoost v3.0.1, LightGBM v4.6.0, Matplotlib v3.10.6, Seaborn v0.13.2, yfinance v0.2.65). The World Bank’s database and open data from Yahoo Finance were used to obtain historical time series of commodity and financial asset prices within the Python API (yfinance) and Pandas Data Analysis Library.

3. Materials and Methods

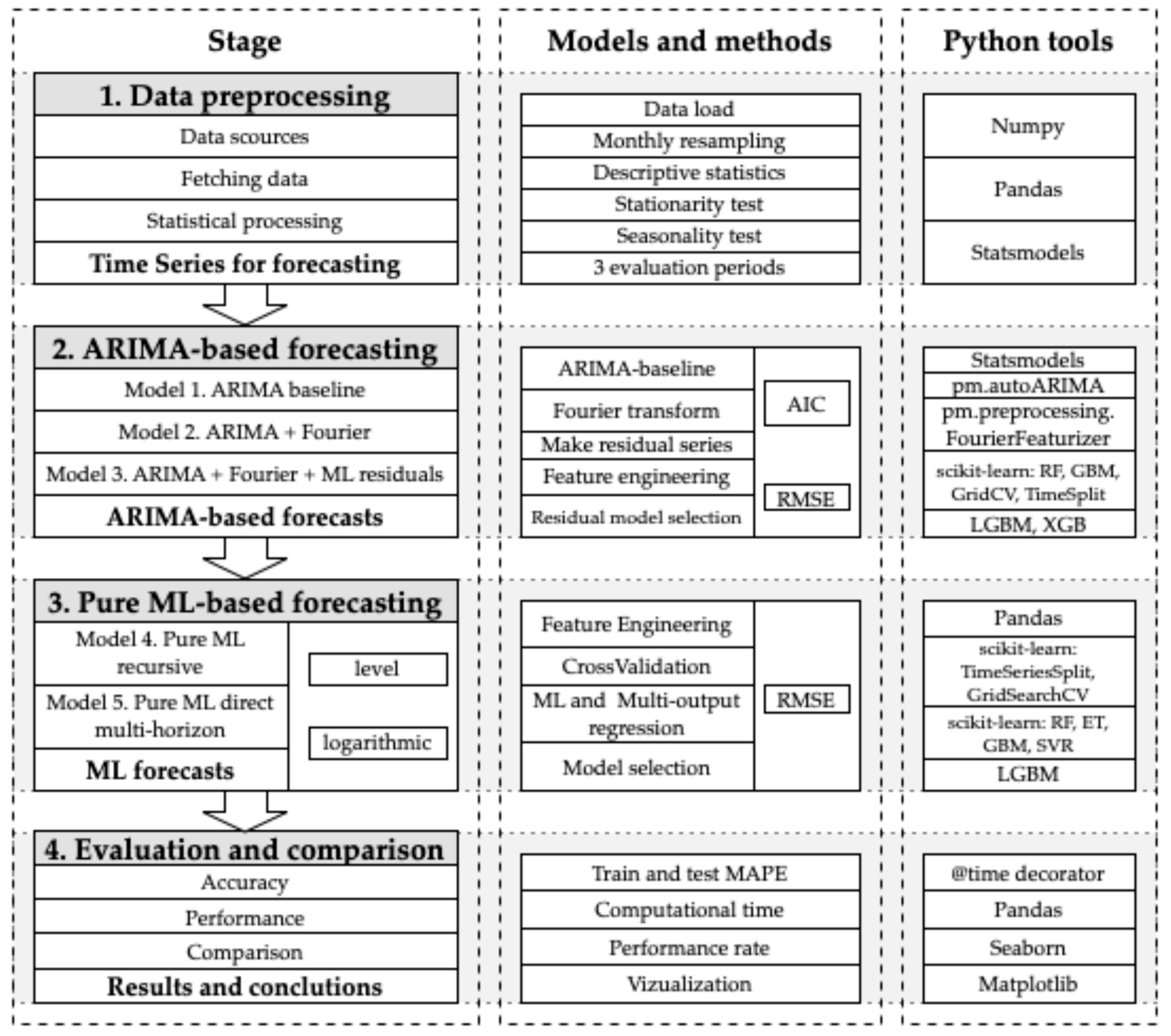

In this study, we develop a reproducible forecasting framework that integrates classical econometric ARIMA-based models with ML architectures to analyze and forecast monthly financial and commodity markets under economic security conditions. The design follows a 4-stage sequence, ensuring transparency, comparability, and methodological rigor while addressing the persistent trade-off between interpretability and computational efficiency. The research workflow is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The research workflow.

Figure 1 shows that the research workflow focuses on evaluating ARIMA-based and ML forecasting approaches in 4 stages. In Stage 1 (data preprocessing), time series (TM) from Yahoo Finance and the World Bank are consolidated, stationarity (ADF) and seasonality diagnostics are applied, and three evaluation periods (December-2023, December-2024, and July-2025) with 12-month test horizons are generated. In Stage 2 (ARIMA-based forecasting), three configurations are compared: baseline ARIMA, ARIMA + Fourier, and an ARIMA + Fourier + ML hybrid with residual correction via supervised learning (RandomForest, GradientBoosting, LGBM, and XGB). In Stage 3 (Pure ML-based forecasting: RandomForest, ExtraTrees, GradientBoosting, SVC and LGBM), recursive (one-step iterative) and direct (multi-output) strategies are implemented with gap-aware cross-validation. In Stage 4 (Evaluation and Comparison), test MAPE values, computational cost analyses, and domain- and subdomain-specific performance metrics are compared to generate model selection guidelines.

3.1. Stage 1. Data Preprocessing: Acquisition and Diagnostics

The empirical foundation of this study is a panel of monthly price series from January 2005 to July 2025 (with a maximum history depth of 247 months), assembled from distinct core data infrastructures to ensure coverage across financial markets, physical commodity spot prices and futures, and aggregate market indices.

A monthly frequency panel from two public sources was used. Yahoo Finance provides daily financial time series for equities, major FX, Bitcoin against the US dollar, benchmark equity indices (e.g., ^DJI, ^GSPC), and front-month commodity futures (e.g., CL = F, GC = F). These daily closes for Yahoo Finance (n.d.), are explicitly aggregated into a single monthly grid (Zherlitsyn, 2024; Yahoo Finance Python API, 2025). The World Bank open data source provides monthly spot commodity prices and composite commodity indices. These series are ingested as published and aligned to month-end timestamps (World Bank, n.d.). All preprocessing is time-causal and performed within the analysis window to avoid information leakage (Zherlitsyn, 2024; Timbers et al., 2024).

To systematically analyze the empirical results, each series is categorized by domain and subdomain within those market roles using the following symbols:

FC—Financial asset domain, crypto subdomain, consisting of

BTC—Bitcoin price (BTC-USD), USD/token;

ETH—Ethereum price (ETH-USD), USD/token;

USDT—Tether price (USDT-USD), USD/token;

XRP—Ripple price (XRP-USD), USD/token.

FS—Financial asset domain, equity (share) subdomain, consisting of

AVGO—Broadcom Inc stock price (AVGO), USD/share;

CELH—Celsius Holdings Inc. stock price (CELH), USD/share;

KO—The Coca-Cola Company stock price (KO), USD/share;

LUMN—Lumen Technologies Inc. stock price (LUMN), USD/share;

MARA—Marathon Digital Holdings Inc stock price (MARA), USD/share;

MO—Altria Group Inc stock price (MO), USD/share;

MSFT—Microsoft Corporation stock price (MSFT), USD/share;

MSTR—MicroStrategy Inc stock price (MSTR), USD/share;

NVDA—NVIDIA Corporation stock price (NVDA), USD/share;

SCHW—Charles Schwab Corporation stock price (SCHW), USD/share;

STLA—Stellantis N.V. stock price (STLA), USD USD/share;

TSLA—Tesla Inc. stock price (TSLA), USD/share;

TSM—Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company stock price (TSM), USD/share;

UMC—United Microelectronics Corporation stock price (UMC), USD/share;

V—Visa Inc. stock price (V), USD/share;

WMT—Walmart Inc. stock price (WMT), USD/share.

FX—Financial asset domain, FX spot subdomain, consisting of

EUR—Euro to US dollar spot exchange rate (EURUSD = X), USD/EUR;

JPY—US dollar to Japanese yen spot exchange rate (JPY = X), JPY/USD;

KZT—US dollar to Kazakhstani tenge spot exchange rate (KZT = X), KZT/USD.

FA—Futures domain, agricultural futures subdomain, consisting of

FCC—Cocoa futures price (CC = F), USD;

FCT—Cotton futures price (CT = F), USD;

FKC—Coffee futures price (KC = F), USD;

FSB—Sugar futures price (SB = F), USD;

FZC—Corn futures price (ZC = F), USD;

FZS—Soybeans futures price (ZS = F), USD;

FZW—Wheat futures price (ZW = F), USD.

FE—Futures domain, energy futures subdomain, consisting of

FBZ—Brent crude oil futures price (BZ = F), USD;

FCL—WTI crude oil futures price (CL = F), USD;

FNG—US natural gas Henry Hub futures price (NG = F), USD.

FM—Futures domain, metal futures subdomain, consists of

FGC—Gold futures price (GC = F), USD;

FHG—Copper futures price (HG = F), USD;

FPL—Platinum futures price (PL = F), USD;

FSI—Silver futures price (SI = F), USD.

CA—Commodity domain, agricultural spot subdomain (World Bank commodity series), consisting of

COA—Cocoa spot price, USD/kg;

CFAR—Coffee, Arabica (ICO) price, USD/kg;

MAIZ—Maize spot price, USD/mt;

PALM—Palm oil spot price, USD/mt;

SBOIL—Soybean oil spot price, USD/mt;

SOY—Soybeans spot price, USD/mt;

SUGW—World sugar spot price, USD/kg;

WHRW—US HRW wheat spot price, USD/mt;

KCL—Potassium chloride fertilizer spot price, USD/mt.

CE—Commodity domain, energy spot subdomain (World Bank commodity series), consisting of

WTI—WTI crude oil spot price, USD/bbl;

NGEU—European natural gas hub spot price, USD per MMBtu;

NGUS—US natural gas spot price, USD/mmbtu.

CM—Commodities domain, metal spot subdomain (World Bank commodity series), consisting of

AL—Aluminum spot price, USD/mt;

CU—Copper spot price, USD/mt;

GOLD—Gold spot price, USD/troy oz;

IORE—Iron ore spot price cost and freight, World Bank series (cfr spot), USD/dmtu;

ZN—Zinc spot price, USD/mt.

IC—Market index domain, commodity index subdomain (World Bank commodity series), consisting of

AGRI—World Bank agriculture price index;

TCI—World Bank total commodity price index;

ENER—World Bank energy price index;

BMEX—World Bank base metals price index excluding iron ore;

MMIN—World Bank metals and minerals price index;

PMET—World Bank precious metals price index.

IF—Market index domain, equity index subdomain, consisting of

DJI—Dow Jones Industrial Average index level (^DJI);

SPX—Standard and Poor’s 500 index level (^GSPC).

Descriptive diagnostics follow established practice in applied forecasting (Zherlitsyn, 2024; Hyndman & Athanasopoulos, 2018). The mean, median, standard deviation, and coefficient of variation for each series are computed to quantify the level and dispersion. We summarize distributional shape using unbiased sample skewness and excess kurtosis. Weak stationarity in the unit-root sense is screened with the Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) test, using the information-criterion lag selection; we record the minimal differencing order at which the ADF rejects at the 5% level and the corresponding p-value. Deterministic annual seasonality is summarized using an STL decomposition at period 12 in robust mode, reporting the standard seasonal strength measure. STL is computed only when at least 36 monthly observations are available to ensure stable components (Hyndman & Athanasopoulos, 2018; Schratz et al., 2019; Mák, 2023).

3.2. Stage 2. ARIMA-Based Forecasting and ML Residual Correction

In this stage, we apply a baseline ARIMA backbone with a Fourier adjustment and a constrained ML layer that learns only the residual structure. The primary model is a monthly ARIMA-based model with Fourier regressors.

Model 1. Baseline ARIMA(p, d, q) model in compact notation (Hyndman & Athanasopoulos, 2018):

Model 2. ARIMA model with Fourier regressors (Hyndman & Athanasopoulos, 2018; Smith, 2025):

where is the time series observation at time ;

is the backshift (lag) operator ();

is the differencing operator of order (, etc.);

is a constant (drift term);

is the AR polynomial of order ;

are autoregressive coefficients;

is the MA polynomial of order ;

are moving average coefficients;

are white noise innovations (error terms);

is the order of the autoregressive part;

is the degree of differencing;

is the order of the moving average part;

is the Fourier feature vector at time t;

and are regression coefficients for the k-th Fourier harmonic;

is the seasonal Fourier period;

is the Fourier harmonic ( is the maximum number for and is selected via cross-validation).

ARIMA orders are selected using information criteria (AIC) in the training window, using the AutoARIMA estimator from the Python 3.12.9 pmdarima library, with conservative caps to avoid over-parameterization (Zherlitsyn, 2024; Timbers et al., 2024; Smith, 2025). Although the primary studies used SARIMA models with autoregression as a baseline, the AutoARIMA model estimator tool indicated that the optimal models were classical ARIMA models. Therefore, the ARIMA model is considered the basic starting point in this study. The differencing order is searched in the range . The ADF diagnostic from Stage 1 is used only to guide the search, not to fix . The p and q ARIMA orders are limited to 6. Fourier harmonics enter as exogenous regressors to capture multi-frequency annual components. Candidate pairs are evaluated on a time-ordered validation slice taken from the tail of the training sample; the pair minimizing the AIC is then fixed for the final selection (Karamolegkos & Koulouriotis, 2025; Hyndman & Athanasopoulos, 2018; Smith, 2025).

After fitting the ARIMA + Fourier models, strictly out-of-fold residuals are generated via an expanding-window procedure and modeled with a small, regularized learner (e.g., scikit-learn-based gradient boosting or random forests and LightGBM/XGBoost using conservative depth and learning-rate settings). Residual forecasts for the 12-month horizon are recursively added to the ARIMA + Fourier baseline (Karamolegkos & Koulouriotis, 2025; Timbers et al., 2024; Zherlitsyn, 2024). To prevent information leakage, residuals are generated out-of-fold via an expanding-window scheme: at each time t within the training sample, the model is refit to and a one-step prediction is recorded; the out-of-fold residual is retained. This yields a time-causal residual series for supervised learning. A lightweight, strictly causal feature set is built from the residual lags and a lagged 12-month rolling mean. A small portfolio of regularized learners is compared using rolling, time-ordered cross-validation (TimeSeriesSplit) combined with a constrained hyperparameter search via GridSearchCV on the residual-training sample; the learner with the lowest cross-validated RMSE is selected and refit to all available residuals (Timbers et al., 2024; Schratz et al., 2019). Residual forecasts for the 12-month horizon are then generated recursively and added pathwise to the ARIMA + Fourier baseline, model 3:

All estimation and validation occur within the training window; the terminal 12 months are held out for testing. This preserves the primary dynamics’ interpretability and confines ML to the incremental, non-linear remainder (Durairaj & Mohan, 2021; Timbers et al., 2024).

3.3. Stage 3. Pure ML-Based Forecasting (Direct vs. Recursive)

To compare the core forecasts from Stage 2 with the ML methods, we implement two strictly time-causal, standalone ML baselines that learn only from each series’ internal history and are evaluated on the same 12-month period. All preprocessing and validation occur within the training window to prevent look-ahead bias. Models are trained on monthly actual prices (levels) and logarithmic (logs) input data. The training window is limited to 36–240 monthly observations to avoid very short fits and dilution from outdated regimes (Zherlitsyn, 2024; Timbers et al., 2024).

Model 4, a pure ML recursive model, is a recursive one-step learner that produces a 12-month path by iterating one-month-ahead predictions. At month , features are constructed exclusively from : autoregressive lags ; lag-only rolling statistics (mean and standard deviation over months); a mild momentum proxy; and calendar month/quarter dummies. Model selection is conducted on the training data via expanding, rolling-origin validation, with a gap that holds out the most recent observations before each validation block (to avoid overlapping-target contamination). We compare shallow, variance-controlled learners (Random Forests, Extra-Trees, LightGBM, XGB, and SVR) and then refit the best model on all supervised rows before strict recursive rollout of h-steps, feeding each prediction back as the next lag (Zherlitsyn, 2024; Timbers et al., 2024).

Model 5, a pure ML direct model, is a horizon learner that predicts the vector in a single step using the same no-leak feature set. Multi-output regressors from the same model families (Random Forests, Extra-Trees, LightGBM, XGBoost, and SVR) are used. The validation design enforces (i) a minimum expanding train size of 48 months, (ii) a fixed-length validation window, and (iii) a gap at least as long as the evaluation horizon, thereby preventing implicit peeking through overlapping inputs/targets. Where beneficial, a light ridge calibration on the 12-dimensional output is tested and retained only if it lowers the in-sample multi-horizon RMSE. As in the recursive design, L and the horizon are reduced adaptively for very short histories to stabilize variance (Schratz et al., 2019; Hyndman & Athanasopoulos, 2018).

Across both ML baselines, feature engineering is intentionally minimal and strictly causal (no exogenous covariates are used), so performance reflects learned temporal structure rather than auxiliary signals. Hyperparameter search spaces are constrained to prevent overfitting.

3.4. Stage 4. Evaluation and Comparison

Out-of-sample evaluation employs an anchored rolling origin scheme with expanding training windows and a fixed 12-month forecast horizon (3 time series slices ending in July 2025, December 2024, and December 2023). For each series, multiple non-overlapping twelve-month evaluation periods are generated by incrementing the terminal date of the estimation sample. Within each backtest iteration, all modeling decisions are determined solely from the training window to prevent information leakage.

Model comparison proceeds via MAPE, which provides dimensionless scale normalization. The evaluation includes both the median MAPE, which is robust to outliers, and minimum, first-quartile, and third-quartile MAPEs to capture best-case performance for each configuration. In addition, the Python implementation records search, training, and prediction times in seconds for every run. These timings are rescaled by the effective length of the training sample to obtain adjusted computation times on the four performance cores of the Apple Silicon M2Pro—the same hardware configuration is used for all models. Thus, each configuration is evaluated jointly in terms of forecast accuracy and computational cost. This synthesis is aimed at balancing forecast accuracy, runtime efficiency, and model parsimony under economic-security constraints, where stability, transparency, and reproducibility are essential.

4. Results

4.1. Data Collection and Descriptive Statistics

The Stage 1 results cover a broad panel of monthly time series grouped into financial assets (23), futures markets (14), core commodities (17), and commodity and financial indices (8), as previously described in the methodology workflow. Each series spans January 2005–July 2025 and is expressed at a month-end frequency. Table 1 provides an aggregate subdomain-level summary of the core descriptive statistics and time-series diagnostics. The detailed series-level diagnostics are available in Table A1 in Appendix A.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and time-series diagnostics for financial assets, futures, commodity prices, and commodity indices by subdomain *.

Table 1 shows that the equity and crypto subdomains exhibit the highest dispersion (CV ≈ 0.83–0.94), while commodities and FX remain stable (CV ≈ 0.17–0.32) and energy markets are intermediate (CV ≈ 0.53–0.54). Stationarity properties differ markedly: futures, commodities, and indices achieve stationarity at d = 0 or d = 1, whereas crypto shows no stationarity in the range of 0 to 3 (0% stationary at d = 0, 75% at d = 1), and equity shows mixed stationarity across both levels.

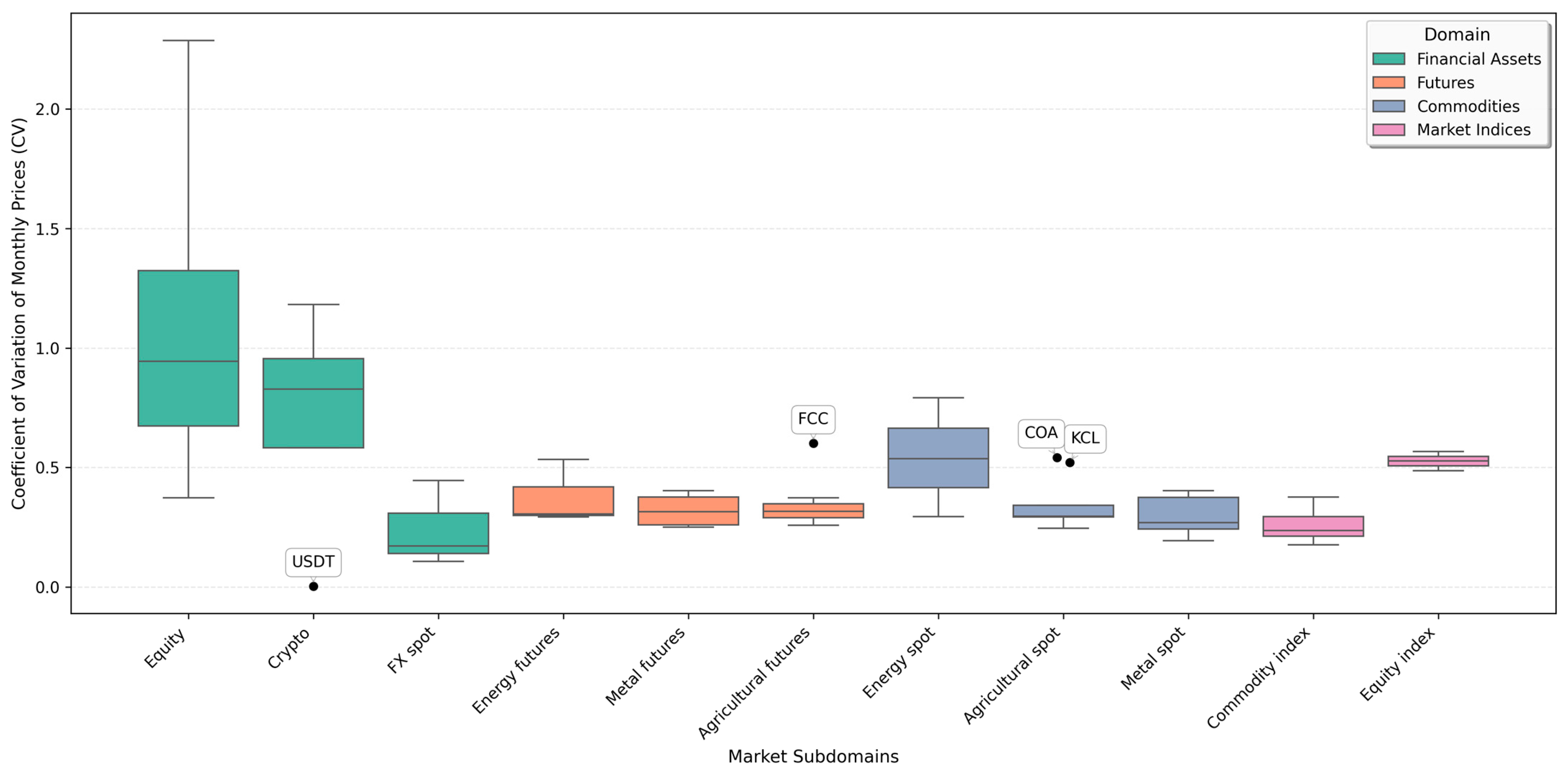

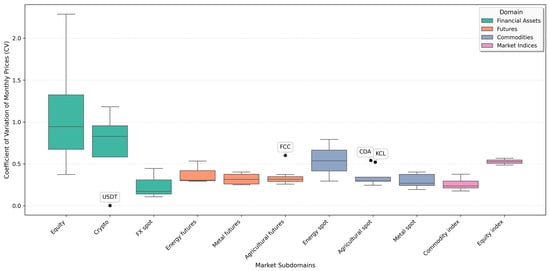

In addition, Figure 2 shows that the coefficients of variation are broadly similar across all domains except equity, crypto, and energy spots, with median CVs below 0.5. The assets in the forex market subdomain behave similarly to those in other markets. In contrast, the equity and crypto subdomains are clearly more volatile. In this regard, ML models may be more appropriate for capturing their dynamics than purely linear time-series specifications.

Figure 2.

Cross-subdomain distribution of monthly CV.

Figure 2 also highlights three notable outliers. USDT is an almost perfectly stable instrument, fluctuating narrowly around 1 USD and standing apart from the generally high-risk financial assets. Among the commodity-related prices, cocoa futures (FCC) and cocoa spot (COA) exhibit unusually high dispersion relative to other agricultural contracts. The same outliers are shown for potassium chloride (KCL) prices. These cases signal markets in which price risk is structurally higher and forecast uncertainty and economic-security implications warrant particular attention, as well as the potential application of more sophisticated analytical and forecasting methods.

As Table 1 shows, in the crypto and energy spot subdomains, high dispersion is coupled with pronounced asymmetry and fat tails in a subset of series, so skewness and kurtosis jointly indicate that large upward or downward moves are more frequent than under a Gaussian benchmark. In contrast, the futures domain is much better behaved in terms of variation. The agricultural and metal spot prices exhibit lower average dispersion. Here, the absolute value of skewness is small, and kurtosis is close to the Gaussian benchmark for most series, making them suitable for standard ARIMA specifications with minimal differencing. Market indices behave as diversified aggregates. Their CV values are lower than those of the underlying risky assets, so they primarily reflect aggregated or exogenous influences that relatively simple time-series structures can capture.

Across the subdomains summarized in Table 1, the STL-based annual seasonal strength is close to zero in the median, and only a few precious metals and selected financial or futures series show modest seasonal components. This means that deterministic 12-month cycles explain only a small fraction of the overall variance and that, for most series, volatility domains and regime dependence are more important than regular seasonal patterns.

Therefore, two practical implications for the modeling program follow. First, the ARIMA family is an appropriate baseline for the commodity and index domains, often applied in levels or with a single difference and without relying heavily on seasonal terms. Second, the financial asset block, especially high-growth tech and crypto, exhibits a combination of high dispersion, non-stationarity after multiple differences, positive skew, and heavy tails; here, baseline ARIMA must be augmented (Fourier terms where warranted, volatility models, regime-switching, or robust hybrids with ML residual correction) to achieve economically meaningful error bounds. In economic security, forecast risk, and thus the size of hedging buffers and liquidity cushions implied by a prudent risk appetite, is structurally larger for the financial asset block. At the same time, commodities and indices offer a more stable foundation for level-based econometric forecasts. Thus, the Stage 2 evaluation systematically compares ARIMA baselines to Fourier-augmented and residual-corrected hybrids across all series.

4.2. ARIMA-Based Model Results

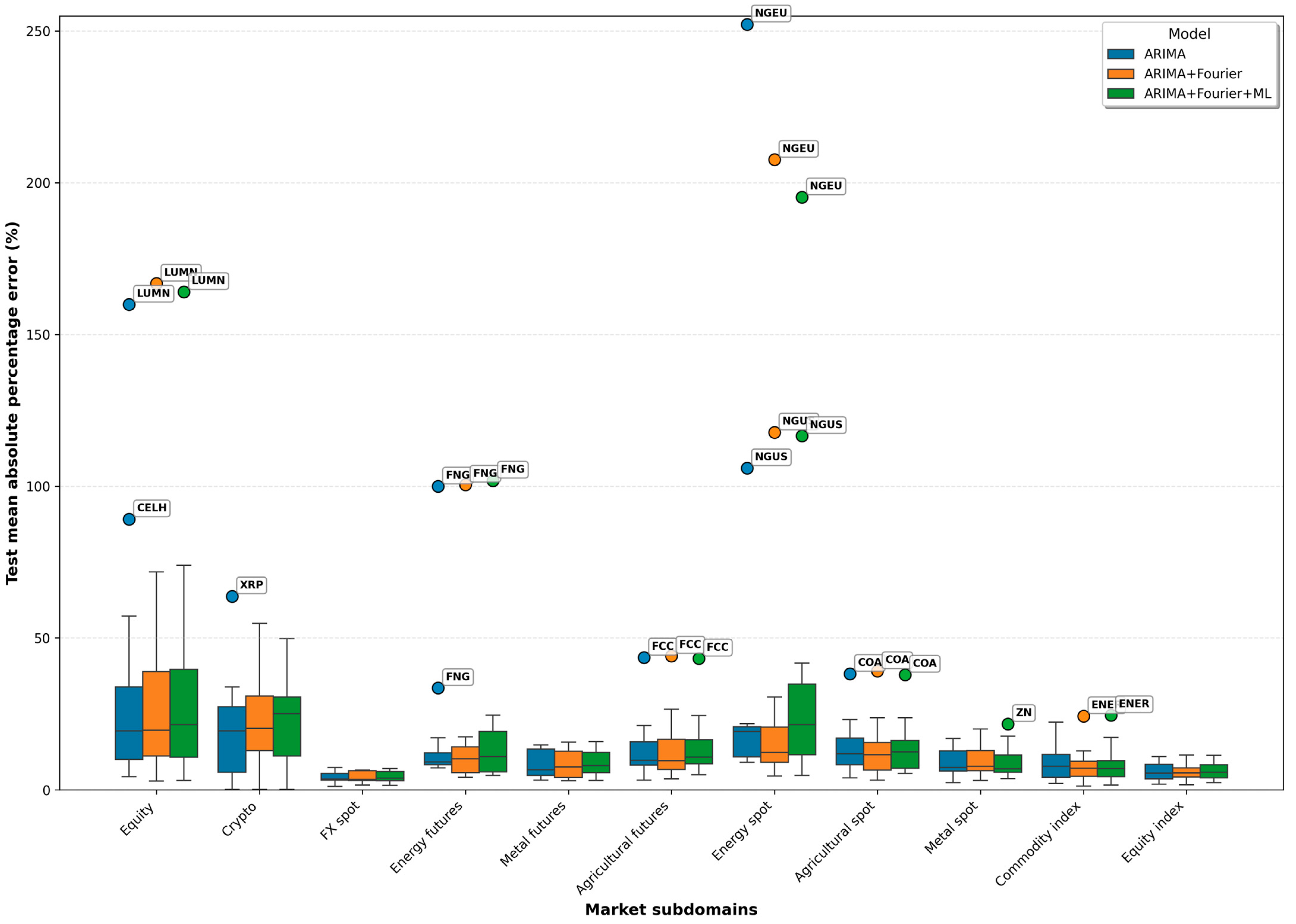

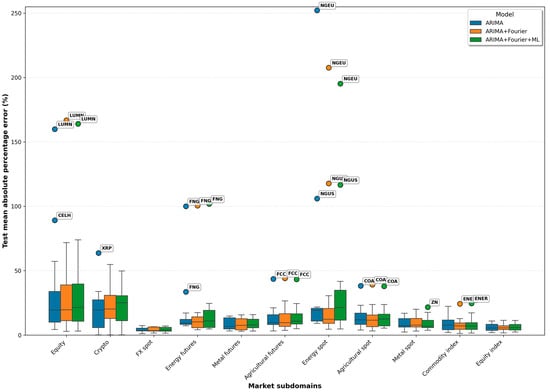

Stage 2 evaluates three ARIMA-based specifications: baseline ARIMA, ARIMA + Fourier (seasonal augmentation), and ARIMA + Fourier + ML (hybrid with residual correction). Table 2 reports subdomain-level results, Table A2 provides series-level and domain-level detail, and Figure 3 illustrates the MAPE distribution and outliers.

Table 2.

Forecast accuracy and adjusted computation time for ARIMA-based models by market subdomain.

Figure 3.

Test MAPE across market subdomains for ARIMA-based models.

Across all subdomains, median MAPE values remain broadly similar for the three ARIMA-based specifications. In most cases, the difference in medians across ARIMA, ARIMA + Fourier, and ARIMA + Fourier + ML is within 1–2 pp, indicating that the overall explanatory gain from Fourier regressors or residual ML correction is modest at the subdomain aggregation level. At the same time, the minimum achievable MAPE varies substantially across series, ranging from 0.08% for stable assets such as USDT (hybrid model) to 7.26% in the energy futures subdomain and 9.15% for the energy commodities subdomain, demonstrating that the best-fitting ARIMA-type models can achieve very high accuracy for stable assets but remain structurally limited for volatile ones.

These patterns align with the Stage 1 domain diagnostics. Subdomains with the highest dispersion (equity, crypto, and energy spot) also exhibit the highest median MAPE values, typically around 20%, regardless of the ARIMA specification. In contrast, FX spot and equity indices—characterized by the lowest variance and nearly universal stationarity at d = 0 or d = 1—consistently deliver median MAPE values below 6%. The commodity subdomains occupy the intermediate band with typical medians of 8–15%, consistent with their moderate CV levels. Significantly, computational time grows almost proportionally with model complexity: the hybrid ARIMA + Fourier + ML model exhibits runtimes 40–190 times longer, primarily due to repeated fitting and cross-validated hyperparameter search of the residual learner.

Figure 3 shows the findings through the distribution of test errors. A sharp separation is visible between the crypto, energy spot, and equity subdomains—where the boxplots show wide dispersion and median MAPEs near or above 20–25%—and the lower-volatility groups such as FX spot, equity indices, and metal spot. Energy futures show partial dispersion but remain below the volatility of the energy spot markets. For most subdomains outside these high-volatility groups, the boxplots show overlapping interquartile ranges, indicating that switching between ARIMA, Fourier-augmented ARIMA, or hybrid models does not materially alter the central distribution of forecast errors. Outliers are rare and tightly associated with specific assets—most prominently LUMN, NGEU, NGUS, XRP, FNG, and CELH. These cases reflect idiosyncratic structural breaks, extreme kurtosis, or episodic jumps rather than model misalignment, underscoring the asset-specific nature of forecasting difficulty and the need for individual treatment in these markets.

Appendix A Table A2 provides the underlying series-level evidence. Average MAPE values (which are more sensitive to extreme errors than medians) are consistent across the three model families for most assets, reinforcing the similarity of subdomain-level medians. Meaningful improvements of ARIMA + Fourier over baseline ARIMA occur for specific series with mild periodicity or a cyclical structure, including MO, MSFT, MSTR, FBZ, FCL, FNG, TCI, and several commodity futures. The hybrid ARIMA + Fourier + ML configuration also yields selective improvements, notably for SBOIL (from 10.70% to 8.80%), USDT (0.12% to 0.08%), V (10.08% to 9.43%), and several metal commodities. However, for most high-volatility assets (e.g., NGUS, NGEU, MARA, CELH), the hybrid model provides no systematic accuracy gains and may even worsen performance due to noise amplification in nonlinear residual dynamics.

Taken together, the results show that minimal MAPE accuracy below 5% is attainable across all subdomains. Low and moderate median MAPEs are found for FX spot, equity indices, and metal spots and agricultural spots, metal futures, and commodity indices, respectively. In contrast, energy spot, crypto, and high-growth equities continue to exhibit elevated MAPEs across model specifications due to their inherent volatility and distributional irregularities.

In practical terms, better prediction of economically sensitive series—e.g., food commodity prices, energy prices, or exchange rates—means that organizations and governments can more proactively manage reserves, adjust procurement, or hedge risks before a price shock hits. In other words, high-volatility commodities (like energy) and most financial assets require more complex prediction tools and econometric models.

Thus, traditional ARIMA models are still valuable. The addition of domain-specific features and ML improves forecast accuracy, strengthens decision-making, reduces the risk of unfounded management decisions, and positively impacts overall economic security. The next stage of this study delves deeper into future forecasting models and Python-based tools, extending the discussion to core ML approaches and advanced workflows.

4.3. ML Technology in Prediction Tasks

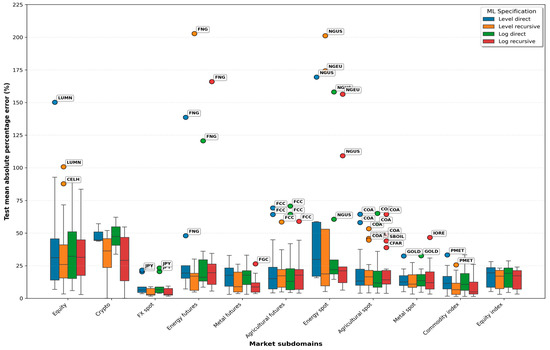

For Stage 2, ML forecasts and evaluations are shown on the same monthly panel as before. Table 3 reports the median and minimum test MAPE, the median performance ratio (ratio of test MAPE to train MAPE), and the median adjusted computation time for each subdomain and ML model. If the performance ratio > 1, it indicates degradation out-of-sample; values above ~1.5 signal material overfitting. Detailed data, including test MAPE and performance ratio values, are provided in Table A3 of Appendix A. Figure 4 shows the distribution of test MAPE values across subdomains and highlights individual outliers.

Table 3.

Forecast accuracy and performance metrics for ML models by market subdomain.

Figure 4.

Test MAPEs across market subdomains for ML-based models.

Across subdomains, the median test MAPE remains broadly comparable across the four ML settings and, in most cases, does not differ dramatically from the ARIMA-based results of Stage 2. Median errors are generally below 20% across all subdomains except crypto, equity, and energy spot, where median values frequently fall in the 25–40% range, consistent with the volatility hierarchy documented in Stage 1. The differences between direct and recursive ML are moderate at the subdomain level. Recursive ML usually achieves slightly lower median MAPE values than direct ML, particularly for FX spot, equity indices, energy spot, and metal futures. In contrast, level-based and log-based variants behave similarly in most markets. These patterns support the view that ML is competitive with econometric approaches for stable subdomains but provides only partial gains in highly volatile settings.

The minimum MAPE values show a much more apparent difference between the methods. Recursive ML achieves the lowest minima across nearly every subdomain, typically below 5% and often close to 1–3% for FX spot, commodity indices, and several futures. The direct ML configurations perform substantially worse in this respect. For example, in the crypto subdomain, the best direct-level minimum is 43.81%, and in energy spot, it is 15.83%, while the corresponding log-direct minima are 33.85 and 14.59%, respectively. All other subdomains exhibit substantially lower minima under recursive ML, indicating that iterative one-step procedures capture short-term dependencies more effectively and generalize more robustly. This result holds for both scales, even when volatility is pronounced.

The median performance ratios show that direct ML often produces training MAPEs that are unrealistically low relative to test MAPEs. In several assets, the ratio exceeds 2, indicating material overfitting. These include series such as FCT, FPL, FZC, MARA, IORE, and KCL, where extremely low in-sample errors coexist with much higher test MAPEs, thereby confirming that the direct 12-month multi-output approach is prone to learning noise within the training window. In contrast, recursive ML maintains performance ratios mostly between 0.3 and 0.8, a range that signals stable generalization and a substantially better balance between training and testing behavior. This divergence between direct and recursive ML aligns closely with theoretical expectations.

A difference in computation time complements these accuracy patterns. Direct ML is consistently fast, with median adjusted times ranging from 1.6 to 2.4 s across subdomains. Recursive ML is slower, typically taking 9–11 s, because each iteration requires repeated cross-validation and hyperparameter tuning.

The detailed results shown in Table A3 reinforce these conclusions. Several assets achieve average test MAPEs below 10% across different ML settings. These include AGRI, TCI, BMEX, FPL, FC, FCT, FZC, EUR, JPY, ALUM, CU, MAIZ, and WTI. These assets exhibit lower dispersion and moderate tail behavior, which support the use of ML. The series with short histories such as ETH, XMR, and USDT constrain direct ML because insufficient observations limit the construction of multi-horizon feature sets; recursive ML is more resilient in these settings because it relies on one-step features and shorter lag windows.

Figure 4 complements this analysis by illustrating the cross-subdomain dispersion of test MAPEs. Once again, crypto, equity, and energy spot form the high-variance cluster. The magnitude of outliers is substantial, often exceeding 100 percent and occasionally approaching 150–200 percent. LUMN remains the most extreme case, with Table A3 showing average ML test MAPEs between approximately 168 and 315%, a regime-breaking pattern that distorts the scale of the boxplot. The same behavior is observed for NGEU and NGUS, confirming that heavy-tailed or jump-driven series remain difficult for ML models. FX spot forms the most stable group, with exceedingly low dispersion and nearly flat lines for only one crypto asset, USDT, achieving minimum test MAPE values of about 0.04% and exhibiting almost perfect temporal stability. These properties contribute to the robust accuracy observed for currencies and specific indices.

The combined evidence from Table 3 and Table A3, and Figure 4 confirms that ML is a valuable but not universally superior forecasting family. The best performance is observed in recursive configurations, which yield the most accurate minimum MAPEs and the most balanced performance ratios, at the cost of significantly longer computation times. Direct ML is faster, but it is systematically more prone to overfitting and yields unreliable test behavior, particularly in volatile domains. In stable subdomains such as FX spot, commodity indices, and several futures, ML competes effectively with ARIMA-based approaches. In contrast, the high-volatility domains of crypto, equity, and energy spot remain substantially more challenging, and in these cases, ML baselines often underperform relative to the ARIMA + Fourier and ARIMA + Fourier + ML hybrids. For forecasting tasks tied to economic security, where interpretability, parsimony, and robustness are critical, the ARIMA-based frameworks from Stage 2 retain notable advantages.

4.4. Evaluation and Comparison

Table 4 summarizes cross-model performance across the entire panel, combining average, median, and quartile test MAPEs, minimum errors, outlier rates, and median computation times in seconds.

Table 4.

Summarizing forecast accuracy and performance metrics across the investigated models.

The three ARIMA-based specifications are close in terms of accuracy. The average test MAPE lies between 18.20 and 18.75%, with median values around 11.5–11.9% and interquartile ranges ranging from 6.3–6.6% for Q1 to 20.0–21.7% for Q3. Minimum MAPEs are uniformly low, ranging from 0.08% to 0.12%, confirming that for the easier series, all three ARIMA variants achieve nearly perfect one-year-ahead fits. The outlier rate is 3.8–4.8%, and computation times scale monotonically with model complexity. The baseline ARIMA has a median adjusted time of 0.48 s per series, the ARIMA + Fourier regressors requires about 1.91 s, and the hybrid ARIMA + Fourier + ML reaches 2.41 s when counting only search and fitting time for the residual learner, since the underlying Python routine executes a more complex grid-searched training loop.

The pure ML models show a distinctly different profile. The average test MAPE is higher across all four configurations, at 24.14–28.47%, with medians around 16–17% and wider interquartile ranges. Minimum MAPEs can be very low, down to 0.04% in the recursive specifications, which confirms that ML can match or beat ARIMA for a subset of series. However, these gains are offset by heavier tails. The outlier rate rises almost double to 6.1–7.9%. The median computation time remains modest for the direct variants, about 1.6–1.75 s, but increases sharply for the recursive specifications to about 8.8–8.9 s, reflecting the cost of iterative forecasting and repeated grid-searched cross-validation. When the performance ratios shown in Table 3 and Table A3 are considered, direct ML appears systematically more overfitted than the recursive variants, with several series exhibiting ratios above 2. In contrast, recursive ML usually keeps the ratio below 1, thereby providing a more balanced relationship between in-sample and out-of-sample errors.

These aggregated results support a cautious hierarchy. Across the whole panel and for one-year horizons, the ARIMA-based models deliver lower central errors, fewer extreme failures, and shorter or at least comparable computation times relative to the ML baselines, making them the most reliable default under economic-security constraints. The hybrid ARIMA + Fourier + ML approach does not improve the global averages and, in some domains, slightly increases dispersion. Still, it offers targeted benefits on a subset of mildly nonlinear commodity and index series, where its improvements are small, interpretable, and rooted in residual structure rather than opaque pattern mining. In contrast, pure ML shows stronger best-case performance, especially in recursive form, yet this comes with a greater incidence of outliers and, for direct ML, evident signs of overfitting. From a risk-management perspective, this asymmetry is unfavorable because occasional spectacular gains are purchased at the cost of larger and less predictable forecast errors precisely in the volatile series that matter most for economic security.

Therefore, ARIMA with or without Fourier regressors remains the primary tool for operational forecasting in this setting, while ML plays a complementary role. Recursive pure ML is less prone to overfitting than direct ML, yet its average and median test MAPEs are rarely better than those of ARIMA or ARIMA + Fourier.

Economic security requires robustness rather than overfitting accuracy. Forecasts should not drift between backtests. High errors between training and testing results increase budget risk, weaken hedging capabilities, and contribute to false accuracy. Pure ML demonstrated this pattern across several financial assets. The ARIMA + Fourier + ML hybrid performed better because it first accounts for trend, seasonality, and persistence, after which ML accounts for residual curvature. Where the hybrid wins, the improvement is understandable and small. Where it loses, the penalty is significant and random. Such asymmetry is not a good bet on risk.

Thus, the ARIMA-based models performed better on average over a one-year horizon, with the ML models treated as a limited complement rather than a substitute. The logarithmic scale proved more balanced for heavy-tailed series, improving forecasting in pure ML models. Forecasting horizons should also be shortened to 3–8 months for economic security, regularly retrained, and validated without leaks, considering gaps.

5. Discussion

The comparative analysis demonstrates that forecasting performance varies systematically across subdomains, with distinct volatility, distributional shape, and stationarity properties. Consistent with the established forecasting literature, ARIMA-based models performed well on well-behaved, level-stationary or mildly differenced series, confirming their role as a reliable benchmark for structured linear dynamics. This aligns with the results of Hyndman and Athanasopoulos (2018) and the empirical evaluation by Stier et al. (2021), who showed that ARIMA-based models maintain competitive accuracy in stable industrial and commodity environments. In our monthly panel, the median MAPEs for ARIMA and ARIMA + Fourier remained near 11–12%, and the minimum errors approached 0.1%.

Fourier-augmented ARIMA produced selective gains, principally in subdomains with identifiable or partially deterministic seasonal components such as FX spot, agricultural futures, and commodity indices. This behavior aligns with the energy market evidence reported by Karamolegkos and Koulouriotis (2025), where frequency-domain decomposition clarified the interaction between seasonal cycles. In our study, however, the improvements remained modest, confirming that seasonal augmentation helps only when structural periodicity is present. Significantly, Fourier augmentation did not materially change accuracy in high-volatility domains.

The hybrid ARIMA + Fourier + ML models delivered localized improvements for a subset of commodities (for example, SBOIL, ALUM, and WTI) and for stable assets such as USDT, where residual ML captured nonlinear components not explained by ARIMA. These outcomes are broadly consistent with earlier hybrid-model research showing that hybridization can generate incremental gains when the underlying series is only mildly nonlinear (Durairaj & Mohan, 2021; Sherly et al., 2025). However, none of the reviewed studies using ARIMA-based hybrids—including Durairaj and Mohan (2021), Sherly et al. (2025), or the recent ARIMA–Prophet hybrid published in Results in Engineering—provide evidence that hybrid models systematically outperform ARIMA in high-volatility financial markets. Our findings confirm this pattern: at the subdomain level, the hybrid did not improve median accuracy and frequently amplified residual noise in highly volatile assets such as natural gas, crypto-exposed equities, and metals with structural breaks. This behavior is consistent with the instability of hybrid models reported in volatility-dominated environments (Pavlatos et al., 2023) and with the error propagation behavior observed in deep learning or ensemble settings (Ding et al., 2022).

The analysis of pure machine learning models showed that ML does not systematically outperform ARIMA under monthly data and limited historical depth. Although ML often demonstrates higher accuracy in high-frequency settings (Demirel et al., 2021; Ding et al., 2022; Shih et al., 2024), our results show that direct ML baselines frequently suffer from severe overfitting, with performance ratios exceeding 2 across several assets. Recursive ML produced lower test errors but had a substantially longer runtime and increased sensitivity to volatility. These findings are consistent with previous evidence that ML requires long histories and rich feature spaces to generalize reliably (Lago et al., 2021) and that ML error is sharply magnified under structural breaks (Carta et al., 2022). Our performance ratio analysis extends these conclusions by quantifying the relative robustness of recursive ML across fixed horizons and showing that overfitting is most severe in speculative assets and in thin-sample conditions.

The other result of this study concerns the role of the Python computational environment in ensuring reproducible forecasting pipelines. The Python ecosystem—primarily pmdarima for ARIMA estimation, statsmodels diagnostics, scikit-learn and LightGBM/XGBoost for residual learning, and TimeSeriesSplit for causal cross-validation—enabled full control over differencing decisions, seasonal specification, and model selection without information leakage. These capabilities align with recent emphasis on Python as an enabler of transparent, standardized, and leak-free forecasting workflows (Timbers et al., 2024; Horn et al., 2019; van Jaarsveldt et al., 2024; Zherlitsyn, 2024). In our experiments, Python’s deterministic handling of timestamps, consistent out-of-fold validation, and reproducible hyperparameter search directly supported the economic-security goal of building forecasting systems with stable behavior and verifiable reliability.

From an economic-security perspective, the results converge on an essential conclusion. Robustness, interpretability, and stability matter more than narrow gains in point accuracy. ARIMA-type models and their Fourier extensions provide stable behavior, low outlier sensitivity, and transparent parametric structure, all of which are crucial for budgeting, hedging, supply-chain planning, and liquidity decisions. Hybrid and ML models remain valuable tools but must be applied selectively since uncontrolled variance directly increases risk exposure. For highly volatile markets, this study confirms that more complex models do not automatically translate into improved predictive control and may result in misleading accuracy.

6. Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations that define clear avenues for further work.

The analysis relies exclusively on monthly data, which substantially reduces the adequate sample size available for model estimation and cross-validation. This frequency is well-suited for medium-term economic security evaluation, yet it limits ML models’ ability to learn complex temporal dynamics and increases their variance. Higher-frequency (weekly or daily) data would enable richer feature extraction, more robust validation, and a more precise assessment of whether the relative performance of ARIMA-based and ML-based approaches persists when intra-week cycles, structural breaks, and volatility clustering become more pronounced.

Several models are sensitive to parameter tuning and training-window configuration. Although all hyperparameter optimization was performed with strictly time-ordered, leakage-free procedures, the constrained length of the historical window reduces the reliability of grid searches, which could lead to unstable hyperparameter selection for volatile assets. Future research could examine how expanding the training window or using adaptive rolling hyperparameter schemes affects ML generalization.

All ML models were trained on univariate lag-based feature sets. This choice ensures comparability with ARIMA and prevents information leakage but limits the models’ ability to exploit cross-market interactions. Excluding exogenous variables (e.g., macroeconomic indicators, implied volatility indices, geopolitical risk measures, market indices, or sentiment-derived features) limits the expressive capacity of ML models.

Although this study evaluates a transparent and interpretable hybrid residual correction, the scope of hybridization remains restricted. Other hybrid architectures—SARIMAX with exogenous regressors, regime-switching models, multi-step decomposition, Prophet-based seasonal extraction, ensemble hybrids, or parameter-varying ARIMA formulations —may capture structural characteristics that this framework cannot. More flexible decomposition-based hybrids warrant further exploration.

The pure MLs omit deep learning architectures, including LSTM, GRU, Temporal Convolutional Networks, and Transformer-based fusion models. These architectures are increasingly used in financial forecasting and may offer substantial gains for series with long-range dependencies. Future research could benchmark deep models against ARIMA-based pipelines while explicitly evaluating their robustness, interpretability, and stability.

Subdomain-level modeling may obscure meaningful heterogeneity across assets. Several high-volatility series (e.g., LUMN, natural-gas prices, crypto-related equities) exhibit asset-specific tail behavior and structural breaks that require specialized feature engineering or asset-level tuning. Future work could incorporate clustering-based segmentation, separate modeling strategies for structurally volatile assets, or dynamic pooling methods.

However, it should be noted that any expansion must maintain the central principle: improvements in predictive accuracy must not come at the expense of robustness, transparency, or stability, which are foundational for forecasting in the context of economic-security risk management.

7. Conclusions

Economic security encompasses the stability of cash flows, the maintenance of operational continuity, and the preservation of market positions under external shocks. Within this context, forecasting of prices, demand, exchange rates, and interest rates functions as an early warning tool: it shifts corporate responses from ex post to ex ante, enabling adjustments in procurement, pricing, production volumes, hedging strategies, and contract structures before risks materialize.

This study demonstrates that ARIMA-based Python forecasting systems provide the most reliable balance of accuracy, interpretability, and robustness for medium-term (12-month) financial and commodity price prediction. The results confirm the central hypothesis (H1) that ARIMA-based models match or surpass standalone ML across most domains and the second hypothesis (H2) that ML underperforms for volatile, short-history assets.

Across the entire panel, ARIMA-based models achieved average test MAPEs ≈ 18.20–18.75% with consistently low outlier rates, whereas pure ML models produced higher central errors (≈24–28%) and substantially higher outlier incidence. Hybrid ARIMA + Fourier + ML models delivered selective improvements for structured series, supporting the idea that ML is most effective when applied to residual nonlinearities rather than the whole series.

The Python implementation played a critical role in ensuring reproducible, leakage-free, and computationally efficient forecasting workflows. Automated ARIMA’s order selection (pmdarima), cross-validated hyperparameter tuning (scikit-learn, LightGBM, XGBoost), residual learning, and precise timing of routines enabled consistent evaluation across more than 60 series. This demonstrates that Python-based tools are not merely convenient but also essential for scalable, transparent forecasting in economic security environments.

In practical terms, organizations can apply these results to strengthen procurement, hedging, and budget planning systems. ARIMA-based forecasts offer sufficient transparency to support regulatory reporting, internal audit, and risk-limit frameworks. Meanwhile, selective ML residual correction may benefit markets with moderate non-linearity. These findings extend the prior literature by demonstrating that hybrid strategies can be operationalized in a fully automated Python environment and integrated into economic security decision processes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.Z. and V.K.; methodology, D.Z. and V.K.; software, D.Z. and V.K.; validation, D.Z., V.K., O.M. and O.S.; formal analysis, D.Z. and O.K. (Oleh Kolodiziev); investigation, D.Z., O.M. and O.S.; resources, O.M. and O.K. (Olena Khadzhynova); data curation, O.M.; writing—original draft preparation, V.K., O.M. and O.S.; writing—review and editing, D.Z., O.K. (Oleh Kolodiziev) and O.K. (Olena Khadzhynova); visualization, O.K. (Olena Khadzhynova) and O.K. (Oleh Kolodiziev); supervision, D.Z.; project administration, D.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All raw market data used in this study are publicly accessible. Daily financial series were retrieved from Yahoo Finance (https://finance.yahoo.com/, accessed on 24 August 2025). Monthly commodity spot prices and related indices were obtained from the World Bank Commodity Markets “Pink Sheet” Data (monthly prices, https://www.worldbank.org/commodities, accessed on 24 August 2025). No proprietary or restricted data were used.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used Grammarly Desktop 1.144.1 (Superhuman) and ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-5.1 Thinking model) for language polishing and minor text editing, and Claude Code (Anthropic, Claude Sonnet 4.5 model), Google Colab (Google, Gemini 2.5 Flash), and GitHub Copilot (Microsoft, OpenAI GPT-4.1 model) for code debugging and technical refinement. The authors reviewed and edited all AI-assisted outputs and take full responsibility for the final content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Descriptive statistics and time-series diagnostics for financial assets, futures, commodity prices, and market indices.

Table A1.

Descriptive statistics and time-series diagnostics for financial assets, futures, commodity prices, and market indices.

| Symbol of the Series | N | Median | CV | Skew | Kurtosis | ADF-d | ADF-p | STL-s |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TSLA | 182 | 19.16 | 1.28 | 1.06 | −0.36 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| MSTR | 240 | 13.34 | 2.02 | 4.03 | 16.35 | 3 | 0.51 | 0.00 |

| MARA | 159 | 20.12 | 1.03 | 1.37 | 1.02 | 0 | 0.04 | 0.00 |

| LUMN | 240 | 11.92 | 0.37 | −0.61 | 0.10 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.12 |

| MSFT | 240 | 39.41 | 1.16 | 1.34 | 0.54 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| TSM | 240 | 16.87 | 1.22 | 1.73 | 2.41 | 3 | 0.45 | 0.00 |

| V | 209 | 77.01 | 0.82 | 0.67 | −0.67 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.10 |

| NVDA | 240 | 0.66 | 2.29 | 3.04 | 8.58 | 3 | 1.00 | 0.00 |

| AVGO | 192 | 18.66 | 1.47 | 2.43 | 5.86 | 3 | 1.00 | 0.24 |

| CELH | 223 | 1.29 | 1.71 | 2.10 | 4.26 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| WMT | 240 | 20.16 | 0.71 | 1.70 | 2.89 | 3 | 0.82 | 0.00 |

| MO | 240 | 25.49 | 0.61 | 0.23 | −1.01 | 1 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| SCHW | 240 | 25.03 | 0.68 | 0.87 | −0.46 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| UMC | 240 | 1.59 | 0.86 | 1.34 | 0.10 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| KO | 247 | 29.56 | 0.50 | 0.56 | −0.70 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| STLA | 182 | 6.13 | 0.65 | 0.76 | −0.03 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| BTC | 131 | 9630.72 | 1.18 | 1.42 | 1.29 | 3 | 0.09 | 0.00 |

| ETH | 93 | 1621.30 | 0.78 | 0.38 | −1.07 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| XRP | 93 | 0.49 | 0.88 | 2.19 | 4.21 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.12 |

| USDT | 93 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 1.31 | 10.01 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.26 |

| EUR | 247 | 1.20 | 0.11 | 0.47 | −0.62 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| JPY | 247 | 109.83 | 0.17 | 0.47 | 0.09 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.05 |

| KZT | 247 | 182.82 | 0.45 | 0.38 | −1.49 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.04 |

| FCL | 247 | 70.76 | 0.29 | 0.27 | −0.30 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| FBZ | 217 | 75.63 | 0.30 | 0.16 | −0.84 | 0 | 0.03 | 0.00 |

| FNG | 247 | 3.58 | 0.53 | 1.62 | 2.76 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| FGC | 247 | 1298.53 | 0.40 | 0.79 | 1.43 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.13 |

| FSI | 247 | 17.89 | 0.37 | 0.62 | −0.06 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| FPL | 237 | 1034.45 | 0.26 | 0.93 | −0.08 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| FHG | 247 | 3.19 | 0.25 | −0.08 | −0.38 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.03 |

| FZC | 247 | 398.23 | 0.32 | 0.58 | −0.49 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| FZS | 247 | 1029.51 | 0.26 | 0.08 | −0.72 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.08 |

| FZW | 247 | 543.74 | 0.27 | 0.83 | 0.91 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| FKC | 247 | 134.61 | 0.37 | 1.71 | 3.34 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| FCC | 247 | 2552.38 | 0.60 | 2.99 | 8.68 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| FSB | 247 | 16.32 | 0.30 | 0.64 | −0.06 | 0 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| FCT | 247 | 71.20 | 0.32 | 2.18 | 7.03 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.03 |

| WTI | 247 | 70.84 | 0.29 | 0.27 | −0.31 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| NGUS | 247 | 3.54 | 0.54 | 1.60 | 2.77 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| NGEU | 247 | 8.79 | 0.79 | 3.74 | 17.88 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| COA | 247 | 2.48 | 0.54 | 2.98 | 9.24 | 1 | 0.04 | 0.00 |

| CFAR | 247 | 3.47 | 0.34 | 1.42 | 2.11 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| PALM | 247 | 826.02 | 0.30 | 0.78 | 0.92 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| SOY | 247 | 430.11 | 0.25 | 0.27 | −0.62 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| SBOIL | 247 | 911.90 | 0.29 | 0.81 | 0.52 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| MAIZ | 247 | 177.43 | 0.31 | 0.59 | −0.54 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| WHRW | 247 | 246.25 | 0.30 | 0.73 | 0.21 | 0 | 0.02 | 0.00 |

| SUGW | 247 | 0.37 | 0.28 | 0.47 | −0.38 | 0 | 0.05 | 0.04 |

| KCL | 247 | 301.50 | 0.52 | 2.00 | 5.08 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| ALUM | 247 | 2069.24 | 0.19 | 0.47 | −0.22 | 0 | 0.03 | 0.00 |

| IORE | 247 | 100.10 | 0.37 | 0.62 | −0.42 | 0 | 0.02 | 0.00 |

| CU | 247 | 7061.02 | 0.24 | −0.25 | −0.54 | 0 | 0.04 | 0.00 |

| ZN | 247 | 2366.68 | 0.27 | 0.40 | 0.07 | 0 | 0.04 | 0.00 |

| GOLD | 247 | 1299.58 | 0.40 | 0.80 | 1.45 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.14 |

| TCI | 247 | 94.40 | 0.26 | 0.36 | −0.64 | 0 | 0.04 | 0.00 |

| ENER | 247 | 94.71 | 0.31 | 0.39 | −0.43 | 0 | 0.03 | 0.00 |

| AGRI | 247 | 93.72 | 0.18 | −0.17 | −0.77 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| MMIN | 247 | 90.28 | 0.22 | −0.02 | −0.75 | 0 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| BMEX | 247 | 94.23 | 0.21 | −0.01 | −0.62 | 0 | 0.04 | 0.00 |

| PMET | 247 | 102.30 | 0.38 | 0.65 | 1.02 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.11 |

| DJI | 247 | 17,302.14 | 0.49 | 0.71 | −0.72 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| SPX | 247 | 2028.18 | 0.57 | 0.99 | −0.06 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

Table A2.

Forecast accuracy for the ARIMA-based, Fourier-augmented, and ML residual-corrected models.

Table A2.

Forecast accuracy for the ARIMA-based, Fourier-augmented, and ML residual-corrected models.

| Domain/Symbol of the Series | Model/Metric | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARIMA | ARIMA + Fourier | ARIMA + Fourier + ML | ||||

| Average of Test MAPE | Min of Test MAPE | Average of Test MAPE | Min of Test MAPE | Average of Test MAPE | Min of Test MAPE | |

| Financial assets | 23.75 | 0.11 | 24.21 | 0.12 | 24.71 | 0.08 |

| AVGO | 17.37 | 10.82 | 16.80 | 9.31 | 16.53 | 9.43 |

| BTC | 29.61 | 26.00 | 31.23 | 25.79 | 30.20 | 24.98 |

| CELH | 49.89 | 20.50 | 51.38 | 39.42 | 53.36 | 41.22 |

| ETH | 23.14 | 18.38 | 24.66 | 17.35 | 24.54 | 14.96 |

| EUR | 2.21 | 1.16 | 2.21 | 1.56 | 2.16 | 1.43 |

| JPY | 6.13 | 5.40 | 6.40 | 6.30 | 6.40 | 6.03 |

| KO | 7.00 | 5.81 | 6.72 | 4.93 | 6.68 | 5.21 |

| KZT | 3.63 | 3.20 | 4.03 | 3.16 | 4.35 | 3.62 |

| LUMN | 89.78 | 39.40 | 93.92 | 43.31 | 93.78 | 43.43 |

| MARA | 30.58 | 21.52 | 32.62 | 14.88 | 36.11 | 17.86 |

| MO | 11.04 | 4.80 | 10.82 | 2.90 | 11.08 | 3.18 |

| MSFT | 17.00 | 4.37 | 13.61 | 4.10 | 13.75 | 4.01 |

| MSTR | 49.92 | 45.00 | 48.85 | 45.59 | 48.54 | 45.35 |

| NVDA | 41.27 | 33.91 | 40.83 | 28.40 | 40.97 | 28.83 |

| SCHW | 19.55 | 7.50 | 19.71 | 8.76 | 19.78 | 10.61 |

| STLA | 33.84 | 19.26 | 38.78 | 25.14 | 39.56 | 26.87 |

| TSLA | 25.28 | 17.49 | 26.33 | 20.18 | 28.99 | 21.48 |

| TSM | 19.41 | 8.53 | 21.53 | 14.76 | 21.85 | 15.45 |

| UMC | 11.11 | 7.91 | 10.32 | 5.78 | 10.89 | 6.74 |

| USDT | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.08 |

| V | 10.08 | 5.48 | 9.73 | 5.56 | 9.43 | 5.01 |

| WMT | 16.38 | 5.18 | 16.24 | 5.17 | 15.20 | 4.71 |

| XRP | 32.04 | 11.43 | 29.89 | 17.24 | 33.98 | 22.56 |

| Futures | 14.21 | 3.21 | 13.80 | 3.03 | 14.40 | 3.09 |

| FBZ | 11.19 | 7.26 | 9.33 | 4.33 | 10.51 | 5.22 |

| FCC | 24.99 | 10.19 | 25.36 | 9.75 | 25.44 | 10.49 |

| FCL | 9.57 | 8.06 | 8.21 | 4.20 | 8.90 | 4.76 |

| FCT | 7.31 | 5.18 | 7.76 | 4.84 | 8.63 | 5.97 |

| FGC | 10.47 | 4.77 | 10.04 | 4.12 | 9.97 | 3.91 |

| FHG | 10.88 | 4.64 | 10.10 | 3.03 | 9.35 | 3.09 |

| FKC | 18.74 | 8.26 | 19.07 | 10.62 | 18.26 | 11.49 |

| FNG | 48.64 | 12.41 | 46.99 | 13.15 | 48.51 | 19.01 |

| FPL | 5.50 | 3.28 | 5.73 | 3.43 | 6.30 | 5.09 |

| FSB | 10.13 | 6.64 | 9.65 | 6.50 | 10.83 | 7.89 |

| FSI | 8.19 | 3.92 | 9.18 | 3.94 | 10.13 | 6.28 |

| FZC | 14.69 | 11.27 | 14.87 | 11.91 | 14.86 | 11.29 |

| FZS | 12.58 | 8.40 | 10.69 | 4.36 | 11.08 | 4.96 |

| FZW | 6.15 | 3.21 | 6.19 | 3.63 | 8.82 | 5.66 |

| Commodities | 19.83 | 2.40 | 18.51 | 3.12 | 19.30 | 3.76 |

| ALUM | 8.98 | 2.40 | 8.79 | 3.12 | 8.55 | 3.76 |

| CFAR | 14.18 | 8.24 | 14.03 | 6.37 | 13.91 | 6.74 |

| COA | 24.14 | 12.86 | 24.77 | 14.20 | 24.93 | 15.90 |

| CU | 6.19 | 5.13 | 6.09 | 3.78 | 5.52 | 4.19 |

| GOLD | 10.51 | 4.82 | 10.12 | 4.33 | 9.91 | 3.80 |

| IORE | 10.22 | 6.55 | 10.81 | 7.44 | 10.54 | 6.53 |

| KCL | 14.56 | 3.93 | 14.75 | 3.23 | 14.20 | 5.36 |

| MAIZ | 15.01 | 9.90 | 14.99 | 8.02 | 15.99 | 9.73 |

| NGEU | 97.08 | 19.25 | 79.17 | 10.45 | 86.15 | 21.49 |

| NGUS | 55.37 | 21.85 | 56.75 | 21.91 | 62.07 | 28.76 |

| PALM | 12.57 | 9.41 | 12.08 | 6.90 | 11.96 | 8.20 |

| SBOIL | 10.70 | 5.41 | 9.02 | 5.58 | 8.80 | 6.04 |

| SOY | 15.31 | 11.62 | 12.75 | 9.39 | 13.36 | 9.93 |

| SUGW | 10.11 | 5.36 | 9.47 | 4.90 | 9.99 | 6.02 |