Complexity-Aware Vector-Valued Machine Learning of State-Level Bond Returns: Evidence on South African Trade Spillovers Under SALT and OBBBA

Abstract

1. Introduction

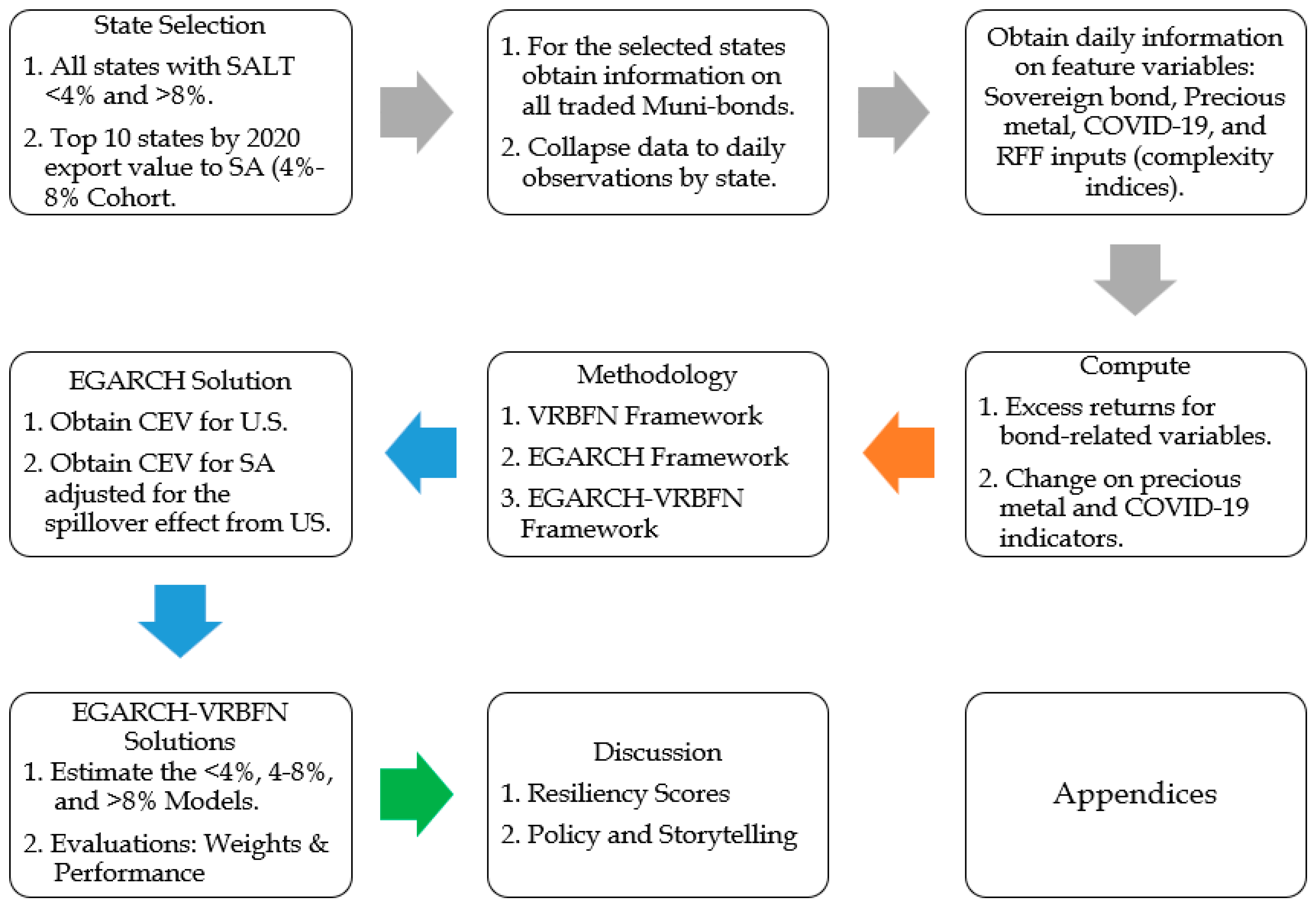

- Methodological Contribution: This study advances hybrid spillover modeling by extending EGARCH–machine learning frameworks to a multi-target architecture. We integrate EGARCH volatility dynamics with the nonlinear cross-sectional predictive capabilities of the VRBFN, utilizing Haykin’s fixed-width kernel tuning (Haykin, 1994) to optimize learning and capture complex, asymmetric spillover effects across multiple financial series.

- Complexity-Aware Predictive Modeling: Our study develops a predictive framework for daily state-level municipal bond returns, where measures of Gaussian and SVM-based complexity take precedence in explaining how fiscal and financial structures influence market behavior. South African trade exposure, the U.S. tax structure, and a global commodity pricing proxy are additional factors that help reveal how complexity conditions the absorption and transmission of external shocks.

- Evaluation of State-level Resiliency: The study introduces a novel state-level resiliency score that measures each municipal bond market’s capacity to absorb and recover from internal disruptions and external shocks. This standardized metric enables a comparative analysis of fiscal stability and shock response across states, providing policymakers and investors with actionable insights.

2. Data

2.1. TCJA and SALT State Selection

2.2. Data and Pricing of Municipal Bond Transactions

2.3. Global Financial and Macroeconomic Feature Variables

2.3.1. Sovereign Bond Indices

2.3.2. Precious Metal Indicators

2.3.3. COVID-19 Indicator

2.4. Structural and Complexity Features

2.5. Market and Commodity Returns

2.6. Average State Returns

3. Methodology

3.1. The VRBFN Framework

3.1.1. Regularization and Width Specification

3.1.2. Implementation

3.2. EGARCH Framework

3.3. EGARCH-VRBFN Framework

3.4. Study Hypotheses

4. Empirical Results

4.1. EGARCH Model Results

4.2. EGARCH-VRBFN Model Performance

4.3. EGARCH-VRBFN Feature Weights and Network Map

5. Discussion

5.1. High-Resilience States (Resilience ≥ 0.40)

5.2. Moderate-Resilience States (0.40 > Resilience ≥ −0.20)

5.3. Low-Resilience States (−0.20 > Resilience ≥ −0.60)

5.4. Structurally Fragile States (Resilience Score < −0.60)

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Schematic of a Single-Target RBFN and LSTM Networks

| Feature | RBFN | LSTM |

|---|---|---|

| Primary domain | Spatial/static function approximation | Temporal/sequential data |

| Hidden representation | Fixed radial centers (local response) | Dynamic memory (contextual response) |

| Structure | 3 layers: Input → Hidden → Linear output | Recurrent: includes memory cells and gates |

| Training | Feedforward | Fully backpropagated through time |

| Interpretability | Highly interpretable, localized | Harder to interpret, temporal dynamics |

| Memory type | Implicit (through radial centers) | Explicit (through cell state and gates) |

| Activation functions | Gaussian, Multiquadric, Inv. Multiquadric, Cauchy, etc. | Sigmoidal and Tanh |

| Overfitting | Lesser probability unless too many neurons or centers | Higher probability due to sequential architecture |

Appendix B. Complexity Regressions

| CPI | Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers: All Items in U.S. City Average (CPIAUCSL) |

| PCE | Trimmed Mean PCE Inflation Rate (PCETRIM12M159SFRBDAL) |

| UEMP | Unemployment Rate (UNRATE) |

| GDP | Real GDP per Capita (A939RX0Q048SBEA) |

| SACPI | Consumer Price Index: All Items Total for South Africa (NGDPRSAXDCZAQ) |

| WUI | Smoothed World Uncertainty Index for South Africa (WUIMAZAF) |

| EXP | International Merchandise Trade Statistics: Exports: Commodities for South Africa (XTEXVA01ZAM664S) |

| SAGDP | Real Gross Domestic Product for South Africa (NGDPRSAXDCZAQ) |

| CPIWUI | The interaction term between SACPI and WUI captures the extent to which economic uncertainty influences inflation and overall economic activity in South Africa. |

Appendix C. Robustness and Over- and Under-Fitting

Appendix D. VRBFN Weights and Network Maps

| Cohort | State | Intercept | Lagged States | Lagged USA | Lagged SA | Lagged COVID | Lagged GP | Lagged SA Vol | Gaussian Complexity (ComplexityG) | SVM Complexity (ComplexitySVM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Less than 4% | AK | −0.0437 | −0.2314 | −0.2829 | −0.0467 | 0.3632 | −0.1404 | 0.0239 | −0.1588 | −0.1571 |

| IN | 0.1198 | −0.0519 | −0.0138 | 0.0429 | 0.0286 | −0.0373 | 0.0951 | −0.0761 | −0.0753 | |

| ND | −0.0021 | −0.2707 | −0.1716 | 0.1593 | 0.5819 | −0.2140 | 0.1257 | −0.3397 | −0.2551 | |

| SD | −0.0721 | −0.1720 | −0.2878 | 0.1296 | 0.1304 | −0.1961 | −0.1576 | −0.0351 | −0.1448 | |

| WV | 0.1139 | 0.0122 | 0.0257 | 0.1460 | 0.0721 | −0.0488 | 0.0422 | −0.0449 | 0.0632 | |

| WY | 0.1781 | −0.2386 | −0.1752 | 0.2731 | 0.1797 | −0.1355 | −0.0241 | −0.1775 | −0.0398 | |

| Avg. | 0.0490 | −0.1587 | −0.1509 | 0.1174 | 0.2260 | −0.1287 | 0.0175 | −0.1387 | −0.1015 | |

| AIC = −7946.00 | Errors: Training = 0.0007; Validation = 0.0012; MSE = 0.0019 | M. Dir = 97.4% r = 1.54; 40% Training | ||||||||

| 4 to 8% | AL | 0.0044 | 0.0541 | 0.0258 | 0.0436 | −0.0378 | 0.0549 | 0.0093 | 0.0184 | 0.0078 |

| GA | −0.0659 | −0.0442 | −0.0567 | −0.0118 | −0.1204 | −0.0309 | −0.1068 | −0.0953 | −0.0337 | |

| IL | −0.0193 | 0.0059 | −0.0169 | 0.0220 | −0.0633 | −0.0380 | −0.0027 | 0.0237 | −0.0350 | |

| MI | −0.0938 | −0.0979 | −0.1050 | −0.0693 | −0.0846 | −0.0591 | −0.0859 | −0.0455 | −0.1085 | |

| OK | −0.0819 | −0.1498 | −0.1785 | −0.1379 | −0.0788 | −0.1197 | −0.1381 | −0.0848 | −0.1894 | |

| SC | −0.0471 | −0.1080 | −0.1045 | −0.0703 | −0.0093 | −0.0664 | −0.0520 | 0.0055 | −0.0941 | |

| TN | −0.0276 | −0.0776 | −0.0720 | −0.0241 | −0.0962 | −0.0467 | −0.0861 | −0.0688 | −0.0425 | |

| TX | 0.0030 | −0.0305 | −0.0551 | −0.0177 | −0.0843 | −0.0459 | −0.0754 | −0.0412 | −0.0524 | |

| Avg. | −0.0410 | −0.0560 | −0.0704 | −0.0332 | −0.0718 | −0.0440 | −0.0672 | −0.0360 | −0.0685 | |

| AIC = −10757.47 | Errors: Training = 0.0002; Validation = 0.0003; MSE = 0.0002 | M. Dir = 98.4% r = 1.15; 60% Training | ||||||||

| Greater than 8% | CA | 0.0821 | −0.0528 | 0.0416 | 0.0013 | −0.1672 | 0.0474 | −0.1154 | 0.0209 | 0.0054 |

| CT | 0.0480 | −0.0937 | −0.2031 | 0.0948 | 0.0379 | −0.1349 | −0.2081 | 0.1103 | −0.1227 | |

| DC | 0.1523 | 0.0655 | −0.0296 | 0.1317 | 0.0584 | 0.0459 | −0.0893 | 0.3947 | −0.0143 | |

| MD | −0.0706 | 0.0716 | 0.0324 | 0.0213 | −0.0803 | 0.1277 | 0.1067 | 0.0926 | −0.1094 | |

| NJ | 0.0292 | −0.1193 | −0.0474 | 0.0167 | 0.0132 | −0.1779 | −0.1246 | 0.2476 | −0.1234 | |

| NY | −0.1569 | −0.1507 | −0.0718 | −0.0718 | −0.1131 | −0.0884 | −0.0691 | 0.0526 | −0.0965 | |

| Avg. | 0.0140 | −0.0466 | −0.0463 | 0.0323 | −0.0419 | −0.0300 | −0.0833 | 0.1532 | −0.0768 | |

| AIC = −10462.17 | Errors: Training = 0.0002; Validation = 0.0003; MSE = 0.0003 | M. Dir = 98.3% r = 1.17; 70% Training | ||||||||

| Variables Listed on VRBFN Network Charts | Corresponding Variables |

|---|---|

| LL4%, L4to8%, and L_G8% | |

| L_COVID | |

| L_ExR_TLT | |

| L_ExR_20YrSA | |

| L_R_GC2PL2 | |

| L_SACEV20Yr | |

| AvgGCompl | |

| AvgSVMCompl | |

| ExR_Statename |

Appendix E. Summary of Findings

| Resilience Group | States | Shock Response Characteristics | Complexity Interpretation | Tax Asymmetry Hypothesis | Overall Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-Resilience | DC, WV | Absorb external shocks with limited spillover into municipal bond pricing—minimal transmission of South African financial or commodity volatility. | High Gaussian Complexity indicates strong adaptive adjustment capacity; SVM Complexity is stable and non-amplifying. | Not supported. These states do not rely on SALT-sensitive tax structures and maintain stable fiscal buffers. | Structural adaptability and diversified fiscal networks prevent amplification of external disturbances. |

| Moderate- Resilience | MD, AL, IN, IL, CA, WY | Mixed shock transmission depending on industrial composition and revenue flexibility. Commodity and trade effects are present but not uniformly persistent. | Varies by state. Positive Gaussian complexity offsets negative SVM rigidity in some states; others rely more on cyclical stabilizers. | Supported equally for MD and CA. Other states show consistent or mixed alignment. | Resilience outcomes depend on whether adaptive complexity outweighs sectoral concentration and fiscal exposure. |

| Low-Resilience | NJ, ND, TX, CT, TN, SC, GA, MI | External shocks propagate into municipal bond returns and persist over time. Both commodity-linked and trade-driven channels are active. | SVM Complexity is predominantly negative, indicating structural rigidity and limited capacity to reconfigure under volatility. | Strongly supported for CT. Support for NJ is strong. Others show vulnerability through narrower tax bases rather than SALT effects. | Structural and revenue constraints hinder the ability to absorb shocks, leading to persistent financial fragility. |

| Structurally Fragile | AK, NY, SD, OK | Shocks are magnified rather than transmitted. Volatility generates reinforcing cycles in bond pricing and revenue expectations. | Consistently low Gaussian and SVM Complexity reflect narrow economic bases and low adaptive flexibility. | Strongly supported for NY due to SALT-driven exposure; weaker evidence for AK, SD, OK where fragility stems from commodity dependence rather than tax asymmetry. | Structural configuration amplifies shocks regardless of origin, producing chronic vulnerability and limited recovery capacity. |

References

- Abrahams, L., Burke, M., & Mouton, J. (2022). Crafting the South African digital economy and society: Home is where the smart is? (Public Policy Paper Series No. 1. LINK Centre). University of the Witwatersrand. [Google Scholar]

- Adesina, A. A. (2025, May 26–30 Afican Development Bank Group. ). African economic outlook 2025 [Conference session]. Making Africa’s Capital Work Better for Africa’s Development, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire. [Google Scholar]

- Ahir, H., Bloom, N., & Furceri, D. (2022). The world uncertainty index (NBER working paper series, report 29763). National Bureau of Economics Research. Available online: https://www.nber.org/papers/w29763 (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Bahrami, F., Shahmoradi, B., Noori, J., Turkina, E., & Bahrami, H. (2022). Economic complexity and the dynamics of regional competitiveness a systematic review. Competitiveness Review: An International Business Journal Incorporating Journal of Global Competitiveness, 33(4), 711–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, D. (2020). Dynamics and correlation of platinum-group metals spot prices. Resources Policy, 68, 101772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartha, J. R., Cebulab, R. J., Nguyen, T., & Nguyenc, H. (2023). New empirical evidence on factors influencing the yield on high-grade municipal bonds. American Business Review, 26(2), 503–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastourre, D., Carrera, J., & Ibarlucia, J. (2010). Commodity prices: Structural factors, financial markets and non-linear dynamics. BCRA working paper series, (RePEc:bcr:wpaper:201050). Central Bank of Argentina, Economic Research Department. [Google Scholar]

- Batten, J. A., Ciner, C., & Lucey, B. M. (2008). The macroeconomic determinants of volatility in precious metals markets. SSRN. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayoumi, T., Goldstein, M., & Woglom, G. (1995). Do credit markets discipline sovereign borrowers? Evidence from U.S. states. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 27(4), 1046–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benbya, H., & McKelvey, B. (2006). Toward a complexity theory of information systems development. Information Technology & People, 19(1), 12–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoudjit, N., & Verleysen, M. (2003). On the kernel widths in radial-basis-function networks. Neural Processing Letters, 17(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollerslev, T. (1986). Generalized autoregressive conditional heteroskedasticity. Journal of Econometrics, 31, 307–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, T., Huemann, Z., Hu, J., & Rahmim, A. (2023). A guide to cross-validation for artificial intelligence in medical imaging. Radiology Artificial Intelligence, 5(4), e220232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broomhead, D. S., & Lowe, D. (1988). Multivariate functional interpolation and adaptive networks. Complex Systems, 2, 321–355. [Google Scholar]

- Buendía-Carrillo, D., Navarro-Galera, A., Lara-Rubio, J., & Gómez-Miranda, M. E. (2025). Understanding the relationship between municipal structure and size, depopulation and default risk. Public Budgeting and Finance, 45(3), 110–128. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X., & Mo, D. (2025). Revaluating safe havens: The effectiveness of traditional assets during extreme crises? International Review of Economics & Finance, 104, 104620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craven, P., & Wahba, G. (1979). Smoothing noisy data with spline functions. Numerische Mathematik, 31(4), 377–403. [Google Scholar]

- Crouse, R. H., Chun, J., & Hanumara, R. C. (1995). Unbiased ridge estimation with prior information and ridge trace. Communication in Statistics-Theory and Methods, 24(9), 2341–2354. [Google Scholar]

- Daily frequency reporting of new COVID-19 cases and deaths by date reported to WHO. (2024). Available online: https://bit.ly/43oLQit (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Dash, G., Kajiji, N., Zhou, H., & Vonella, D. (2023). Municipal bond volatility spillover modeling with COVID-19 effects by hybrid integration of GARCH and machine learning: The connectedness of U.S. states and South African bond markets. The Business and Management Review, 14(1), 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Nero, L., & Giudici, P. (2025). Machine learning models to predict stock market spillovers. Finance Research Letters, 86, 108508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C., Xie, J., & Zhao, X. (2023). Analysis of the impact of global uncertainty on abnormal cross-border capital flows. International Review of Economics & Finance, 87, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diebold, F. X., & Yilmaz, K. (2012). Better to give than to receive: Predictive directional measurement of volatility spillovers. International Journal of Forecasting, 28(1), 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diebold, F. X., & Yılmaz, K. (2014). On the network topology of variance decompositions: Measuring the connectedness of financial firms. Journal of Econometrics, 182(1), 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, D. (2018, September 12). AI stock market prediction: Radial basis function vs. lstm network. Medium. Available online: https://bit.ly/4qWaSQg (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Engle, R. F. (1982). Autoregressive conditional heteroskedasticity with estimates of the variance of U.K. inflation. Econometrica, 50, 987–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erling, M. (2016). Analyzing precious metals returns using a kalman smoother approach. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2827061 (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Everitt, B. S., & Dunn, G. (1991). Applied multivariate data analysis. Edward Arnold. [Google Scholar]

- Florida, R. (2014). The creative class and economic development. Economic Development Quarterly, 28(3), 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, U., Rahman, S., & Aziz, A. (2023). Informality, economic complexity, and internalization of rules: The role of education and social capital in reducing inequality. Frontiers in Sociology, 8, 1241473. [Google Scholar]

- Gladston, A., Sharmaa, A., & Bagirathan, S. S. K. G. (2022). Regression Approach for GDP Prediction Using Multiple Features From Macro-Economic Data. International Journal of Sofware Science and Computational Intelligence, 14(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, S., Kelly, B., & Xiu, D. (2020). Empirical asset pricing via machine learning. The Review of Financial Studies, 33(5), 2223–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldane, A., & May, R. (2011). Systemic risk in banking ecosystems. Nature, 469, 351–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartmann, D., Guevara, M. R., & Hidalgo, C. A. (2017). Linking economic complexity, income inequality, and economic resilience. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 42, 25–38. [Google Scholar]

- Hausmann, R., & Hidalgo, C. A. (2011). The network structure of economic output. Journal of Economic Growth, 16(4), 309–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haykin, S. (1994). Neural Networks a Comprehensive Foundation. Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo, C. A. (2023). The policy implications of economic complexity. Research Policy, 52(9), 104863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, C. A., & Hausmann, R. (2009). The building blocks of economic complexity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(26), 10570–10575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, D., & Kilic, M. (2019). Gold, platinum, and expected stock returns. Journal of Financial Economics, 132(3), 50–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajiji, N. (2001). Adaptation of alternative closed form regularization parameters with prior information to the radial basis function neural network for high frequency financial time series. University of Rhode Island; Kingston. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, B., Malamud, S., & Zhou, K. (2023). The virtue of complexity in return prediction. The Journal of Finance, 79, 459–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilian, L. (2009). Not all oil price shocks are alike: Disentangling demand and supply shocks in the crude oil market. American Economic Review, 99(3), 1053–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahiani, A., Mefteh-Wali, S., & Vasbieva, D. G. (2021). The safe-haven property of precious metal commodities in the COVID-19 era. Resources Policy, 74, 102340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamprecht, N., & Tolmay, A. S. (2017). Performance of South African automotive exports under the African growth and opportunity act from 2001 to 2015. International Business and Economic Research Journal, 16, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemus, G. (2018). Why financial time series LSTM prediction fails. Medium. Available online: https://bit.ly/3LBQgwh (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- León-Delgado, H. d., Praga-Alejo, R. J., Gonzalez-Gonzalez, D. S., & Cantú-Sifuentes, M. (2018). Multivariate statistical inference in a radial basis function neural network. Expert Systems with Applications, 93, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. C., Sun, L. P., Wu, X., & Tao, C. (2025). Enhancing financial time series forecasting with hybrid Deep Learning: CEEMDAN-Informer-LSTM model. Applied Soft Computing, 177, 113241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, M., & Zhou, L. (2005). Exponential Duration: A more accurate estimation of interest rate risk. The Journal of Financial Research, 28(3), 343–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, L., Zhang, D., Alptekinoğlu, A., & Karamalidis, A. K. (2025). Enhancing the resilience of platinum group metal supply chains: Mine to (Re)use. sustainable development. Sustainable Development, 33(5), 7069–7085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahfooz, S. Z., Ali, I., & Khan, M. N. (2022). Improving stock trend prediction using LSTM neural network trained on a complex trading strategy. Ijraset Journal For Research in Applied Science and Engineering Technology, V10, VII. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R., & Sunley, P. (2006). Path dependence and regional economic evolution. Journal of Economic Geography, 6(4), 395–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mealy, P., Farmer, J. D., & Teytelboym, A. (2019). Interpreting economic complexity. Science Advances, 5(1), eaau1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mena, C. (2022). International trade resilience and the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Business Research, 139, 1247–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A. N. M. (2024). Hybrid cryptocurrency price prediction: Integrating EGARCH and LSTM with explainable AI. International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology, 9(12), 731–738. [Google Scholar]

- Naufal, G. R., & Wibowo, A. (2023). Time series forecasting based on deep learning CNN-LSTM-GRU model on stock prices. International Journal of Engineering Trends and Technology, 71(6), 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, D. B. (1991). Conditional heteroskedasticity in asset returns: A new approach. Econometrica, 59, 347–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppedahl, D. (2017). The downturn in agriculture: Implications for the Midwest and the future of farming. Chicago fed letter, (374). Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago. [Google Scholar]

- Orr, M. J. L. (1995). Regularisation in the selection of radial basis function centres. Neural Computation, 7(3), 606–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poggio, T., & Girosi, F. (1990). Regularization algorithms for learning that are equivalent to multilayer networks. Science, 247, 978–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poterba, J. M., & Rueben, K. S. (2001). Fiscal news, state budget rules, and tax-exempt bond yields. Journal of Urban Economics, 50(3), 537–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prathiba, R., BalasinghMoses, M., Devaraj, D., & Karuppasamypandiyana, M. (2016). Multiple output radial basis function neural network with reduced input features for on-line estimation of available transfer capability. Control Engineering and Applied Informatics, 18(1), 95–106. [Google Scholar]

- Pugliese, E., Cimini, G., Patelli, A., Zaccaria, A., Pietronero, L., & Gabrielli, A. (2019). Unfolding the innovation system for the development of countries: Coevolution of science, technology and production. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 16440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, A., & Recht, B. (2007, December 3-9). Random features for large-scale kernel machines. Available online: https://papers.nips.cc/paper_files/paper/2007/file/013a006f03dbc5392effeb8f18fda755-Paper.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Raubitzek, S., & Neubauer, T. (2022). An exploratory study on the complexity and machine learning predictability of stock market data. Entropy, 24(3), 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, H. (2013). Dilemma not trilemma: The global financial cycle and monetary policy independence. National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickman, D., & Wang, H. (2020). What goes up must come down? The recent economic cycles of the four most oil and gas dominated states in the US. Energy Economics, 86, 104665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roszyk, N., & Ślepaczuk, R. (2024). The hybrid forecast of S&P 500 volatility ensembled from VIX, GARCH and LSTM models. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4903194 (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Sammartino, F., Stallworth, P., & Weiner, D. (2018). The effect of the TCJA individual income tax provisions across income groups and across the states. Tax Policy Center, Urban Institute & Brookings Institution. Available online: https://bit.ly/43osASl (accessed on 15 October 2020).

- SAS-V9.4. (2013). The SAS system. The SAS Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Schwert, M., & Testa, C. (2020). Municipal bonds and the macroeconomy: Evidence from high-frequency data. Review of Financial Studies, 33(9), 4051–4090. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, H. A. (1962). The architecture of complexity. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 106(6), 467–482. [Google Scholar]

- Stulz, R. M. (2005). The limits of financial globalization. The Journal of Finance, 60(4), 1595–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, B. (2024). The impacts of the african growth opportunity act on the economic performances of sub-saharan african countries: A comprehensive review. Sci, 6(1), 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, P., Xu, W., & Wang, H. (2024). Network-based prediction of financial cross-sector risk spillover in China: A deep learning approach. NAJEF, 72, 102151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikhonov, A., & Arsenin, V. (1977). Solutions of Ill-posed problems. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Urom, C., Anochiwa, L., Yuni, D., & Idume, G. (2019). Asymmetric linkages among precious metals, global equity and bond yields: The role of volatility and business cycle factors. The Journal of Economic Asymmetries, 20, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Binbergen, J. H., Nozawa, Y., & Schwert, M. (2025). Duration-based valuation of corporate bonds. The Review of Financial Studies, 38(1), 158–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, T. V. (2020). Economic complexity and health outcomes: A global perspective. Social Science & Medicine, 265, 113480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vuyyuri, S., & Mani, G. S. (2005). Gold pricing in India: An econometric analysis. Journal of Economic Research, 16(1), 29–44. [Google Scholar]

- WinORS-2023. (2023). The NKD Group, Inc. Available online: https://www.nkd-group.global (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Wu, Q., Schölkopf, B., & Smola, A. J. (2012). Regularization networks and support vector machines. In J. Suykens, G. Horváth, & S. Basu (Eds.), Advances in learning theory: Methods, models and applications (pp. 9–27). IOS Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, E., Wahib, M., Zhong, R., & Munetomo, M. (2024). Learning from the Past Training Trajectories: Regularization by Validation. Journal of Advanced Computational Intelligence and Intelligent Informatics, 28(1), 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H., Zhou, Z., & Chen, J. (2021). RLSTM: A new framework of stock prediction by using random noise for overfitting prevention. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience, 2021, 8865816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H., Dash, G., & Kajiji, N. (2023, July 10–14). Comparing the performance of shallow and deep learning techniques in predicting South African SMEs’ growth during COVID-19. 23rd Conference of the International Federation of Operational Research Societies, Santiago, Chile. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y., & Yan, J. (2020). A hybrid deep learning approach for systemic financial risk prediction. In Computational science and its applications—ICCSA 2020. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter Estimates | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | DF | Estimate | Standard Error | t Value | Approx Pr > |t| |

| Intercept () | 1 | −0.0046 | 0.0023 | −1.99 | 0.0460 |

| USAEGCev () | 1 | 205.5383 | 78.8551 | 2.61 | 0.0091 |

| EARCH0 () | 1 | −3.7188 | 0.0420 | −88.64 | 0.0001 |

| EARCH1 ) | 1 | 1.4696 | 0.0391 | 37.59 | 0.0001 |

| EGARCH1 ) | 1 | 0.0738 | 0.0061 | 12.07 | 0.0001 |

| THETA () | 1 | −0.3233 | 0.0154 | −20.99 | 0.0001 |

| States | Intercept | Lagged States | Lagged USA | Lagged SA | Lagged COVID | Lagged GP | Lagged SA Vol | Gaussian Complexity | SVM Complexity | Rank Muni Trades | Trade Rank | Cohort |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CA | + | – | + | + | – | + | – | + | + | 1 | 4 | >8% |

| NY | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | 2 | 7 | >8% |

| TX | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | 3 | 1 | 4%–8% |

| NJ | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | + | − | 4 | >10 | >8% |

| IL | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | 5 | 2 | 4%–8% |

| MI | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | 6 | 6 | 4%–8% |

| GA | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | 7 | 9 | 4%–8% |

| MD | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | 8 | >10 | >8% |

| CT | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | + | − | 9 | >10 | >8% |

| IN | + | − | − | + | + | − | + | − | − | 10 | >10 | <4% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dash, G.; Kajiji, N.; Vonella, D.; Zhou, H. Complexity-Aware Vector-Valued Machine Learning of State-Level Bond Returns: Evidence on South African Trade Spillovers Under SALT and OBBBA. Econometrics 2026, 14, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/econometrics14010001

Dash G, Kajiji N, Vonella D, Zhou H. Complexity-Aware Vector-Valued Machine Learning of State-Level Bond Returns: Evidence on South African Trade Spillovers Under SALT and OBBBA. Econometrics. 2026; 14(1):1. https://doi.org/10.3390/econometrics14010001

Chicago/Turabian StyleDash, Gordon, Nina Kajiji, Domenic Vonella, and Helper Zhou. 2026. "Complexity-Aware Vector-Valued Machine Learning of State-Level Bond Returns: Evidence on South African Trade Spillovers Under SALT and OBBBA" Econometrics 14, no. 1: 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/econometrics14010001

APA StyleDash, G., Kajiji, N., Vonella, D., & Zhou, H. (2026). Complexity-Aware Vector-Valued Machine Learning of State-Level Bond Returns: Evidence on South African Trade Spillovers Under SALT and OBBBA. Econometrics, 14(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/econometrics14010001