1. Introduction

Credit rationing is a mechanism of limiting the supply of loans to be given to borrowers at the current interest rate by restricting lending by lenders. When the lenders are unable to differentiate the borrowers according to their risk concerning the capability of their payoff, they might give credit to high-risk borrowers, and the amount of non-performing loans (NPLs) in the credit market may increase, which is called adverse selection. When lenders face risky borrowers and an increasing non-performing loans ratio due to borrowers’ riskiness, they may increase the lending interest rate to compensate for their possible loss. Adverse selection may happen, and the amount of credit given to the market may be decreased, which may cause credit rationing in the credit markets.

Rationing in credit markets is explained by variables that can be counted as interest rate, riskiness, competition between lenders, money supply, amount of loans given in the past, profitability of lenders, collateral, adverse selection, moral hazard, monitoring, repayment habits of borrowers in the past, and the loan application process. The majority of the variables listed can cause rationing by affecting riskiness independently of the interest rate effect. Therefore, whether credit rationing is sensitive to the changing risk structure in the economy will also determine the relationship between riskiness and the economic contraction that credit rationing may cause.

Credit rationing may adversely affect borrowers by limiting their ability to invest or launch new businesses. It can also have broader economic implications, such as reducing overall growth and productivity. Policymakers may introduce tools such as credit scoring systems or collateral requirements to lessen the impact of credit rationing.

In this study, an empirical VAR analysis was developed to determine whether credit rationing is made by the banks operating in the Polish banking sector, due to risky credits, represented by non-performing loans, and to determine how long credit rationing persists. Based on the results of the empirical analysis, we strive to arrive at policy recommendations for the Polish banking sector.

This article contributes to the existing literature on credit rationing and financial stability by focusing on and analyzing data from the Polish banking sector. The study expands the theoretical and empirical understanding of credit rationing by highlighting that the determinants of credit supply constraints can vary significantly across countries due to different banking systems, institutional structures, and portfolio compositions. It also offers valuable insights into credit policy by demonstrating that credit risk alone may not be a sufficient predictor of credit rationing in stable and well-regulated banking sectors, as exemplified by the Polish banking sector.

2. The Theory of Credit Rationing in the Literature and Its Macroeconomic Effects Through Credit Markets

Credit rationing refers to the limitations of lenders’ loan availability, even when borrowers are willing to accept the prevailing interest rate. After the second half of the 1900s, this concept was discussed in the economics literature with the introduction of the Availability Doctrine. This doctrine was introduced into the literature by R. V. Roosa in 1951. According to the doctrine’s main theme (

Scott, 1957), monetary policy affects the supply of lending funds in the fund market and, therefore, the amount of loans that lenders are willing to give. Thus, a contractionary monetary policy affects the economy in a contractionary way by causing a decrease in lenders’ lending funds; in contrast, an expansionary monetary policy leads to an increase in loanable funds in the credit market. Although the doctrine provides a superficial explanation of the concept of credit rationing, it forms the basis for the formation of the concept of credit rationing. Within this framework, it determines how the central bank directs monetary policy, how it can affect the behavior of banks, and thus how it causes credit rationing.

After the Availability Doctrine, D. R. Hodgman made an important contribution to the literature in 1960. According to

Hodgman (

1960), the attractiveness of lending for banks depends on interest and risk. As the amount of credit offered in the market increases, so does the risk of loss for borrowers. If borrowers’ repayment commitments increase, banks’ expected returns on loans change accordingly. Borrowers’ debt repayment commitments have a maximum limit, which is set independently of interest. An increase in the supply of loans in the market can increase the riskiness of loans. Riskiness cannot be compensated for by raising interest rates. In other words, according to Hodgman, commitments that are not affected by interest rates affect bank profitability, but as the amount of credit offered in the market increases, the risk of credit, which varies independently of interest rates, increases.

It can be said, then, that credit rationing since the end of the 1960s has been affected by the profitability factor, which may vary according to the contraction in the money supply or the amount of credit granted. In other words, the contraction in the money supply causes credit rationing, and the increase in the amount of loans given causes an increase in risk. This increase in risk causes credit rationing according to whether it will affect lenders’ profitability. Accordingly, it can be said that if the profitability of lenders decreases, credit rationing increases, and if profitability increases, credit rationing decreases. In a sense, the current period credit rationing differs according to the change in the money supply and the loans given in the past periods due to risk and profitability.

Freimer and Gordon (

1965) argued that there were two different types of credit rationing. The first of these is the rationing, called weak credit rationing, which is made by differentiating the amount of the loan given by changing the interest rate up to a certain upper limit. The second is the strict credit rationing, which is performed by not giving a loan other than the loan planned to be given in advance at a certain interest rate without changing the interest rate. Therefore, credit rationing can occur without a change in the interest rate in the credit market. According to Freimer Gordon, the credit supply curve initially shows a positive sloping structure due to an increase in the interest rate, and then shows a reverse curved structure after a certain interest rate level. Therefore, as the interest rate increases, the amount of credit offered by lenders initially increases, while after a certain interest level, the amount of credit supplied begins to decrease. In other words, credit rationing begins.

With the study of

Freimer and Gordon (

1965), it was revealed that the interest rate and the loans planned to be given in the past period determine credit rationing and that there is an inverse U-shaped relationship between the interest rate and credit rationing. Accordingly, it is emphasized that even if the interest rate increases, loans that were previously planned to be given to creditworthy borrowers can be given, and that credit rationing will not be strictly applied, and, therefore, the interest rate will have a limited role in determining credit rationing.

Another theory, regarding credit rationing, in the literature is the

Jaffee and Modigliani (

1969) model, which claims that credit rationing is in the form of size rationing, and when the demand for credit exceeds the supply of credit, it occurs due to three reasons, which are the rise in interest rates, the inability of banks to classify customers according to their riskiness, and competition in the banking sector. If there are regulations or institutional constraints in the market that prevent interest rates from rising above a certain level, the demand for credit may exceed the supply of credit. In this case, banks may have to ration loans because they cannot raise interest rates to a level that balances the market. In the absence of perfect competition in the banking sector and the presence of a monopolistic structure, banks can engage in credit rationing to ensure profit maximization. In a market with a limited number of lenders, there may be a tendency to generate higher profits by restricting the supply of credit.

Therefore, along with the riskiness in the credit market, the market structure of the banking sector is also the determinant of interest rates. While the increase in competition in the banking sector reduces interest rates, the monopolistic structure that may occur in the sector increases interest rates and increases bank profitability. Increased profitability also reduces credit rationing. Therefore, credit rationing may not depend on interest rates.

In the 1970s, G. Akerlof attributed credit rationing to the phenomenon of asymmetric information in markets and the related problem of adverse selection. According to the study of

Jaffee and Russell (

1976), which entered the literature after Akerlof’s theory, credit rationing based on incomplete information and uncertainty in credit markets is seen in the form of size rationing. When borrowers cannot be differentiated by lenders based on their risk, default can occur after the loan is disbursed. When the default does not incur a high cost to the borrower, there may be a non-repayment incentive for borrowers, and it may be possible for lenders to conduct credit rationing. If collateral is required from borrowers in credit markets and the credit market is a monopolistic market, credit rationing is less common.

According to

Jaffee and Russell (

1976), when riskiness increases, credit rationing is made or not according to the effect of increasing riskiness on profitability. In addition, if high collaterals are demanded as a lending condition and defaults do not reduce profitability, credit rationing also decreases.

In the 1980s, the studies of Stiglitz and Weiss made an important contribution to the subject. According to the model of

Stiglitz and Weiss (

1981), credit rationing occurs when the expected returns on loans do not increase despite the increase in interest rates in the credit markets. This is considered an indication of increased risk in the credit market. When the risk increases, credit rationing occurs in two ways. First, when lenders choose risky borrowers for crediting, adverse selection occurs in the market, and credit rationing occurs, and the profitability of lenders decreases as a result of adverse selection. Second, rising interest rates in the credit markets cause borrowers to engage in high-risk activities, and a moral hazard may occur. Moreover, when this situation cannot be controlled by lenders, it results in a decrease in the expected returns of lenders, and credit rationing occurs. According to the model, credit rationing occurs under the assumption that lenders do not receive collateral. As the collateral required by lenders increases, credit rationing may decrease. On the other hand, the increase in collateral demands may also cause borrowers to enter risky projects and may also cause credit rationing to continue. According to the results of the analysis in the model, the increase in interest rates and the excessive demand for collateral make the portfolios of lenders risky, and the possibility of credit rationing increases.

According to

Bester (

1985), borrowers with a high probability of default prefer a loan agreement with lower collateral and a higher interest rate, while borrowers who are less likely to default tend to opt for contracts with higher collateral and a lower interest rate. Because of this, risky borrowers in the market can be identified due to the fact that they prefer loan contracts with lower collateral and higher interest rates. When collateralization has no cost, lenders can profitably exploit any credit shortfall by increasing the collateral and interest rate at the same time, which eliminates rationing in equilibrium.

A new model of credit rationing was also included in the literature by

Williamson (

1986,

1987), along with the concept of monitoring. In his study, it is argued that if the borrowers are monitored by the lenders, credit rationing may not be enacted, depending on the adverse selection. According to

Williamson (

1986,

1987), asymmetric information is about borrowers’ returns. Credit rationing also occurs because there is a difference in information between lenders and borrowers on this issue. Lenders, who lack information about yields compared to borrowers, face monitoring costs to compensate for this shortfall. This additional cost leads to a decrease in profitability. According to the model, when loan interest rates increase, banks’ interest income increases. However, this increases borrowers’ risk of default, causing banks to face high monitoring costs.

Diamond (

1989) argued that in the credit market, borrowers’ past behavior regarding loan repayments and their long-term activities in the market are determinants of their recognition. In the study, it was stated that these determinants make it easier for borrowers to obtain loans, and therefore, the probability of adverse selection in the credit market with borrowers who have not defaulted in the past is low.

According to

Levenson and Willard’s (

2000) study, maturity is essential in credit rationing. Loan rationing decreases if there is not much time between applying for a loan and receiving a loan. When this period is extended, credit rationing increases. If there is an expectation that the time between the application process and the approval of the loan will be long, borrowers may be reluctant to take a loan or even not apply for a loan at all. In particular, small-scale companies may not want to apply for loans in this context. It is also desirable to give less credit to small companies. Therefore, self-rationing can be seen more in credit markets.

Based on these theories, it can be claimed that there are important references about the risk structure and default risk of borrowers in credit markets, and the effect of credit repayment behaviors of borrowers in the past on credit rationing that can be associated with the risk.

When we consider the theoretical studies in the literature, it can be emphasized that it is possible to have a mutual effect between riskiness and credit rationing. According to many theoretical studies, borrowers’ riskiness in the credit market affects credit rationing. However, in his 1969 study, Hodgman argues that the riskiness in the credit market, regardless of loan interest rates, increases as the supply of credit increases. In this context, the level of riskiness of borrowers in the credit market can be a determinant of the credit supply in the credit market and, thus, of credit rationing, or the credit supply itself can be a determinant of riskiness by acting as a determinant of risk in the credit market.

Credit rationing theory also accounts for how imperfections in credit markets influence macroeconomic dynamics. In a standard economy, interest rates reconcile savings and investments; however, when credit rationing occurs, the amount of credit allocated to borrowers determines investment levels. Credit rationing can generate volatility in investment and output. Thus when companies, particularly small and medium enterprises (SMEs), confront credit constraints/restrictions or banks restrict lending they are forced to use less liquid assets and seek expensive financing, which suppresses investment or they need to be more open for funding their expenditure with their internal resources, such as profits and retained earnings. This may lead to situation when they become more sensitive to internal funds, causing fluctuations in the business cycle and limiting growth by restricting productive investments. Credit rationing is, therefore, not merely a microeconomic concern, as it may shape macroeconomic dynamics and carry significant macroeconomic consequences, including growth reduction via diminished investment, output volatility, business cycle fluctuation, employment level, interruptions in monetary policy transmission, risks and increased inequality and structural rigidities. It is also worth mentioning that credit rationing can also pose a threat to financial stability by pushing firms into informal or hidden credit markets, thus increasing systemic risk. Restricting corporate liquidity can trigger a credit crunch and a deep recession, which can lead them to seek other, informal solutions.

A section of the research underscores how banking-sector frictions and credit rationing may shape the transmission and amplification of macroeconomic shocks, as reflected in the following key contributions.

Gross et al. (

2018) have shown that high leverage ratios (debt-to-equity ratio) in the banking sector are a source of macroeconomic instability. Excessive leverage makes the banking system much more vulnerable to shocks. In the event of an economic shock, banks’ equity quickly decreases because leverage is high. Banks tend to dramatically cut the credit supply (i.e., rationing credit) rather than raising interest rates to protect their decreasing capital and reduce risks. This situation further intensifies the economic contraction. Also

Mittnik and Semmler (

2018) use empirical and structural models to demonstrate how financial fragility, particularly banking sector instability, can influence recessions. They argue that higher leverage ratios of banks and borrowers can trigger credit rationing by making the system more vulnerable to shocks. In other words, excessive indebtedness raises banks’ perceived risk, which causes them to restrict the volume of loans rather than increase interest rates. What is more,

Bernanke et al. (

1999), proved how initial shocks in the economy can cause business cycle fluctuations through the credit market. Credit market imperfections affects those fluctuations through the financial accelerator. When a borrower’s net worth declines due to a shock, external finance becomes more expensive because of higher agency costs. This causes credit rationing and reduces investment and national income.

Credit rationing may also affect monetary policy transmission by weakening its effectiveness. According to the credit channel mechanism, the level of national income is affected by credit flows through changes in the interest rate. However, in rationed credit markets, even low interest rates may not stimulate borrowing. Therefore, it is visible that the impact of monetary policy on the economy must be achieved not only through interest rates but also through the availability of credit. Another important aspect here, emphasized in several studies by

Mishkin (

1990,

1992), is the role of information asymmetry in financial markets and its impact on monetary policy transmission.

Mishkin (

1994) argued that the deterioration of bank balance sheets in the context of lower capital, declining borrowers’ net worth, and increased risk leads to significant credit rationing, which in turn deepens the crisis. Therefore, effective financial regulation and central bank intervention are crucial to reducing systemic risk. The intervention necessity is also recognized by

Bernanke and Gertler (

1995). They highlight the need for policy tools that directly target credit, not just the money supply. When banks perceive higher default risk and there are severe credit restrictions, credit constraints cause output fluctuations. In this case, money supply expansion does not necessarily lead to higher growth, and central bank policy becomes less effective when credit conditions tighten.

As demonstrated by Bernanke, Gertler, Mishkin, Mittnik, and Semmler, credit rationing and the banking system play an important role in generating macroeconomic disruptions. Frictions in the credit market and balance sheet vulnerabilities can arise in economic downturns, leading to severe macroeconomic disruptions, such as recessions and financial crises. For this reason, there may be a need for robust financial regulation and macroprudential policies. Policymakers may promote credit guarantees, borrower screening mechanisms, and interventions that keep credit supply stable and eliminate the negative effects of credit rationing.

3. Non-Performing Loans, Credit Rationing, Profitability, and Credit Markets of Polish Banking Sector

Within the framework of theoretical studies in the literature about credit rationing that have taken place since the Availability Doctrine was introduced, it has been argued that different variables, which are monetary policy, interest rates, riskiness of the borrowers or their default risk in the credit market, competition in the banking sector, collateral, monitoring costs, past behaviors of the borrowers, and also credit supply, are held as determining factors for credit rationing. These variables can also affect each other. For example, in

Shoko et al.’s (

2025) study, credit length and the amount of loans used in the past are considered explanatory variables for determining the risk of default.

Many of these variables affect credit rationing by influencing riskiness. A variable that may represent riskiness in the literature is the non-performing loans (NPLs) ratio. In the macroeconomic context, the ratio of non-performing loans to total loans, belonging to commercial banks in credit markets, can be considered as an indicator of the repayment behavior of borrowers and therefore their riskiness in credit markets. Since a significant part of the credit supply in credit markets is generally made by commercial banks, the ratio of commercial banks’ total loans to their total assets is considered an important indicator of credit rationing in the credit market. In this context, it may be possible to consider these two variables as those that affect each other in credit markets and are mutually determinant of each other according to

Hodgman (

1960).

If riskiness is represented by the NPL ratio and credit rationing is represented by the ratio of loans to total assets, the changes of these two variables over time can give an idea of whether these variables change in accordance with the theory.

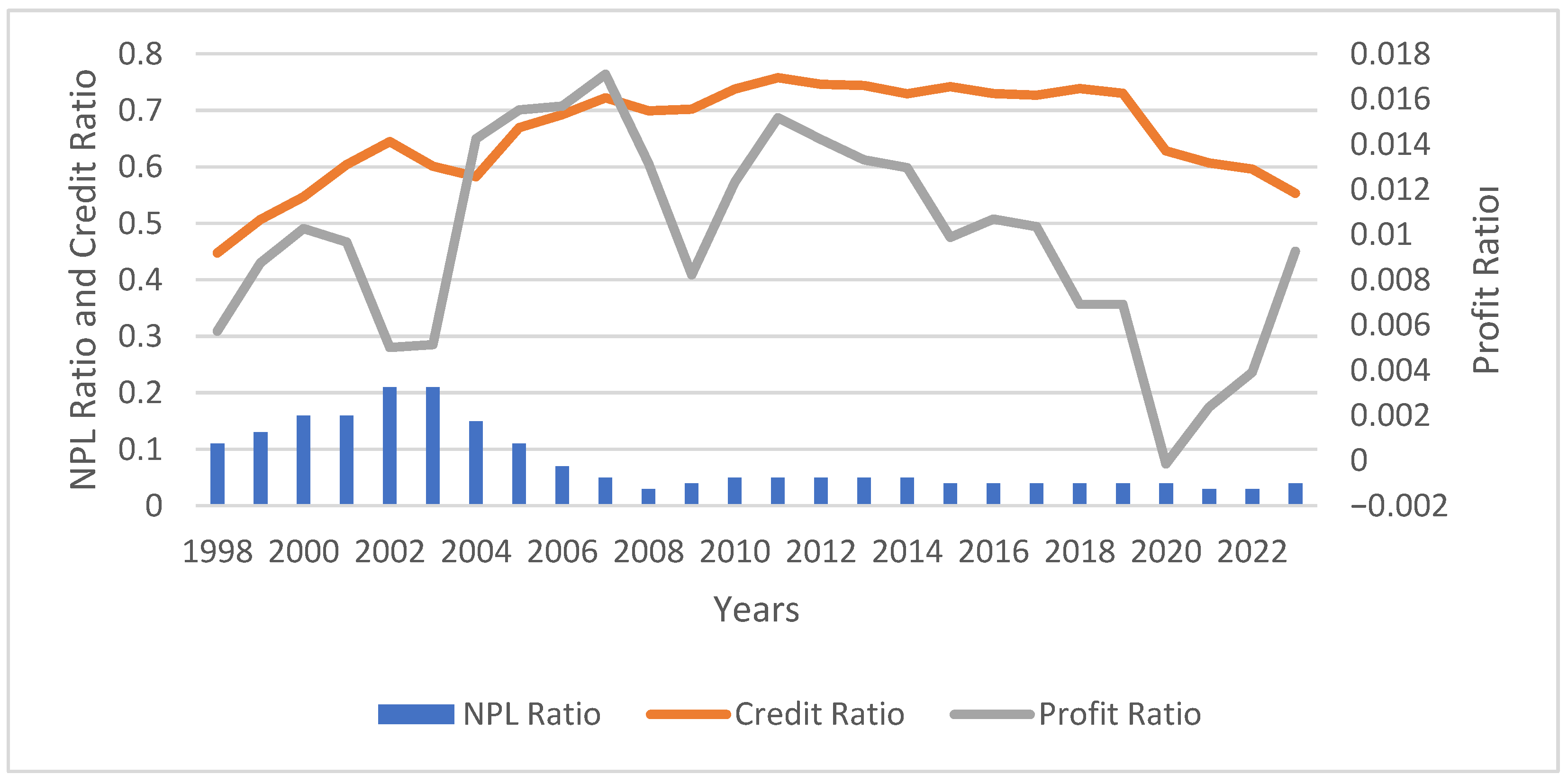

Considering the data of the Polish banking sector from 1998 to 2023, the changes in the ratio of non-performing loans (NPLs) to total loans as a factor that can represent borrowers’ risk and the ratio of total loans to total assets, which can represent credit rationing, can be examined in

Table 1 and

Figure 1. Additionally, the profitability ratio that may theoretically vary in relation to these variables, is shown in

Table 1 and

Figure 2. As claimed in theoretical studies mentioned in this article, it is argued that credit rationing can be made when the interest rate in the credit market is not changed; the interest rate in the credit market is not included in the analysis. In

Table 1, the NPL ratio shows the ratio of NPLs to total loans, the credit ratio represents the proportion of total credits to total assets, and the profit ratio presents the contribution of net profit to total assets.

Figure 1 shows that while the risk in the credit market increased from 1998 to 2003 based on non-performing loans, the banking sector did not ration loans and continued to provide loans to the market. Since 2003, the risk has been decreasing and then continuing at a certain average. During this period, the credit ratio does not change in a risk-related manner.

Credit rationing may be caused by a difference in information regarding the return on investments between lenders and borrowers. This means that if, in comparison to borrowers, lenders have incomplete information about the return on possible investments made by borrowers, lenders face monitoring costs to compensate for this situation. This additional cost is incurred if borrowers default, resulting in a decrease in lenders’ profitability. According to

Kosztowniak (

2023), high NPL ratios reduce profitability and restrict new lending. Therefore, when examining the change between risk and credit rationing, it may be necessary to examine how the banking sector’s profitability also changes. The mutual changes of these variables can be seen by examining

Figure 2.

As visible in

Figure 2, from 1998 to 2007, the profitability ratio changed in the opposite direction to the NPL ratio risk; on the contrary, the profitability ratio changes in the same direction as loan rates. Since 2007, profitability has been observed to be independent of riskiness and credit ratio. This situation may also arise from the general structure of the Polish banking sector, existing regulations, and some unique characteristics of the sector. Therefore, examining these issues is also important in the analysis of credit rationing.

As per reviews of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) as early as 2014, it was clear that, in practice, the tax authorities in Poland permitted more substantial deductions of loan losses and debt relief than would be expected based on a strict interpretation of the law. The IMF report suggested that preventing NPLs from potentially constraining credit expansion and following economic growth is essential. It could be applied through tax disincentives (including restrictions on deducting loan losses or debt reliefs) and other barriers, such as insolvency procedures (

IMF, 2014).

Before describing the characteristics of the Polish banking sector, it is important to highlight several elements influencing this market, which may result from historical events, the previous system and the policies pursued at that time, as well as the general social characteristics of the country. In Poland, households are much less indebted than those in other eurozone countries. At the end of August 2024, household debt in banks amounted to PLN 795.25 billion (

KIG, 2024). In 2024, as per Trading Economics, the average household’s liabilities in Poland constitute approximately 23% of the GDP, whereas in the eurozone, it was 51–52% of the GDP (

Trading Economics, 2024). This may result from reduced trust in any institution and a strong distinction between “ownership” itself and the vision of “ownership on credit”. The exceptions are mortgage loans, which constitute a significant part of loans granted to households in Poland, which is a characteristic of the Polish banking sector, reflecting the popularity of home ownership and the boom in the real estate market. Although mortgage loans still constitute a significant part of the banks’ offer, a noticeable drop in demand for these loans has occurred over the past few years, which is the result of rising interest rates and economic uncertainty. Currently, almost an equal portion of the structure of loans granted by banks to non-financial enterprises takes current loans (42%) and investment loans (41%). Real estate loans account for approximately 15% of the total loan volume (

Kancelaria Senatu, 2025).

In general, the banking sector in Poland is considered stable, as confirmed by the Polish Financial Supervision Authority (KNF)

1 and Bank Guarantee Fund (BFG)

2 reports and data presented in

Table 2. It remains that the Polish banking sector is well capitalized, with a solvency ratio of 17%, which is higher than the minimum requirements set by law and significantly higher than the EU average of around 8–10%.

Regarding profitability growth, it is still limited by macroeconomic difficulties, changing regulations, or decreasing interest margins. The Polish banking sector is also characterized by strong financial innovativeness and digital adoption—70% of consumers use online or mobile banking, which is above the percentage of many EU countries. This sector combines traditional banking services operating within the framework of current regulations with rapidly developing fin-tech services and continues to evolve, focusing on further digital transformation and adapting to economic and regulatory changes in the European Union. At the same time, the Polish banking sector is one of the smallest in Europe in terms of the assets-to-GDP ratio. Therefore, it occupies a very weak position both in terms of its real size and the scale of financing the economy. Importantly, the role of the banking sector will be fundamental from the perspective of the expected economic recovery and the need to implement the transformation of the Polish economy and increase its innovativeness (

Pawlonka, 2024).

As a member of the European Union, the Polish banking sector is a subject to significant influence of EU monetary policy, including decisions of the European Central Bank (ECB) on interest rates and regulatory changes. These policies play a significant role in shaping the direction of the Polish financial market. Therefore, the Polish system is strictly regulated and requires compliance with EU banking regulations and directives, which ensures its financial stability. Regulations such as the Capital Requirements Directive and Basel III guidelines are enforced to ensure that banks maintain sufficient capital buffers. The functioning of banks in Poland is based on Act of 29 August 1997—Banking Law and the Act of 21 July 2006 on Financial Market Supervision. In addition, the activities of banks in Poland are regulated by, among others, the Act of 29 August 1997 on the National Bank of Poland, the Act of 29 August 1997 on mortgage bonds and mortgage banks, and the Act of 10 June 2016 on the Bank Guarantee Fund, the deposit guarantee system and compulsory restructuring (

MF, 2024b). A significant role for the Polish banking sector is also played by the legally non-binding but highly influential guidelines of the Polish Financial Supervision Authority (

GUS, 2018).

In Poland, there are institutions established to represent banks, such as the Polish Bank Association (ZBP)

3, which supports the development of the banking sector and represents its interests. The Polish banking sector is also well supervised by the Polish Financial Supervision Authority (UKNF) and the Bank Guarantee Fund (BFG), which helps ensure banking sector stability and customer deposit security (

Polakoszczedza.pl, n.d.). The BFG is responsible for the aforementioned security of deposits, which means it guarantees deposits up to a specified amount (specified in the Act of 10 June 2016 on the Bank Guarantee Fund, the deposit guarantee system and compulsory restructuring) and ensures the security of customer funds in the case of a bank’s bankruptcy (

MF, 2024b). The deposit guarantee covers funds up to the equivalent in PLN of 100,000 EUR. This means that the total value of funds accumulated by a given customer in each bank (even in different accounts) is secured up to the specified amount, and the BFG guarantees no longer cover the abovementioned amount (

MF, 2024a). The BFG website contains a list of banks covered by the deposit guarantee system, including 25 commercial banks and approximately 480 cooperative banks, as well as 18 Cooperative Savings and Credit Unions known as SKOK

4 (

BFG, 2025).

The banking sector in Poland has undergone a consolidation process, resulting in a smaller number of larger and more significant entities in the market. Minor banks have been taken over by larger entities, resulting in greater operational efficiency and a broader range of products. Foreign banks—particularly German, French, and Austrian banks—that are present in the Polish market, also play an important role in the Polish market. Some large foreign banking groups treat Poland as a key market in the CEE region, influencing its overall dynamics.

The Polish banking sector stands out from other countries, especially the eurozone. A few distinguishing features are worth mentioning:

Low share in GDP. As already mentioned, the assets of financial institutions in Poland constitute a smaller percentage of the GDP than in many Western European countries (

Stefański, 2009, p. 50). In terms of economy size, the Polish banking sector is one of the smallest in Europe (

PZU, 2020). The nominal value of the Polish banking sector assets is growing (in real terms, i.e., in relation to the size of the economy). In 2010, banking sector assets constituted almost 82% of GDP, and as of the end of Q2 2024, their share reached 88.7%. However, compared to France (324.1%), Finland (281.9%) seems to be extremely low (

Pawlonka, 2024). Even considering the average level for the eurozone, which is approximately 165%, the Polish share in GDP is marginal.

Small value of equity. The Polish banking sector remains one of the smallest among the European banking sectors in terms of the real value of equity. At the end of Q2 2024, the Polish banking sector’s equity reached PLN 259.41 billion, but in real terms (in relation to GDP) decreased to around 7.4%. Comparing it to the eurozone average of around 14% or the GDP share for countries such as Luxembourg (29.4%), Austria (22%), or France (20.9%), it is also extremely low. From the perspective of the analysis of the banking sector’s ability to finance the needs of the developing economy and its future needs related to, among other things, the energy transformation of the economy, ensuring the expansion and transformation of the banking sector and enabling it to build equity remains crucial (

Pawlonka, 2024).

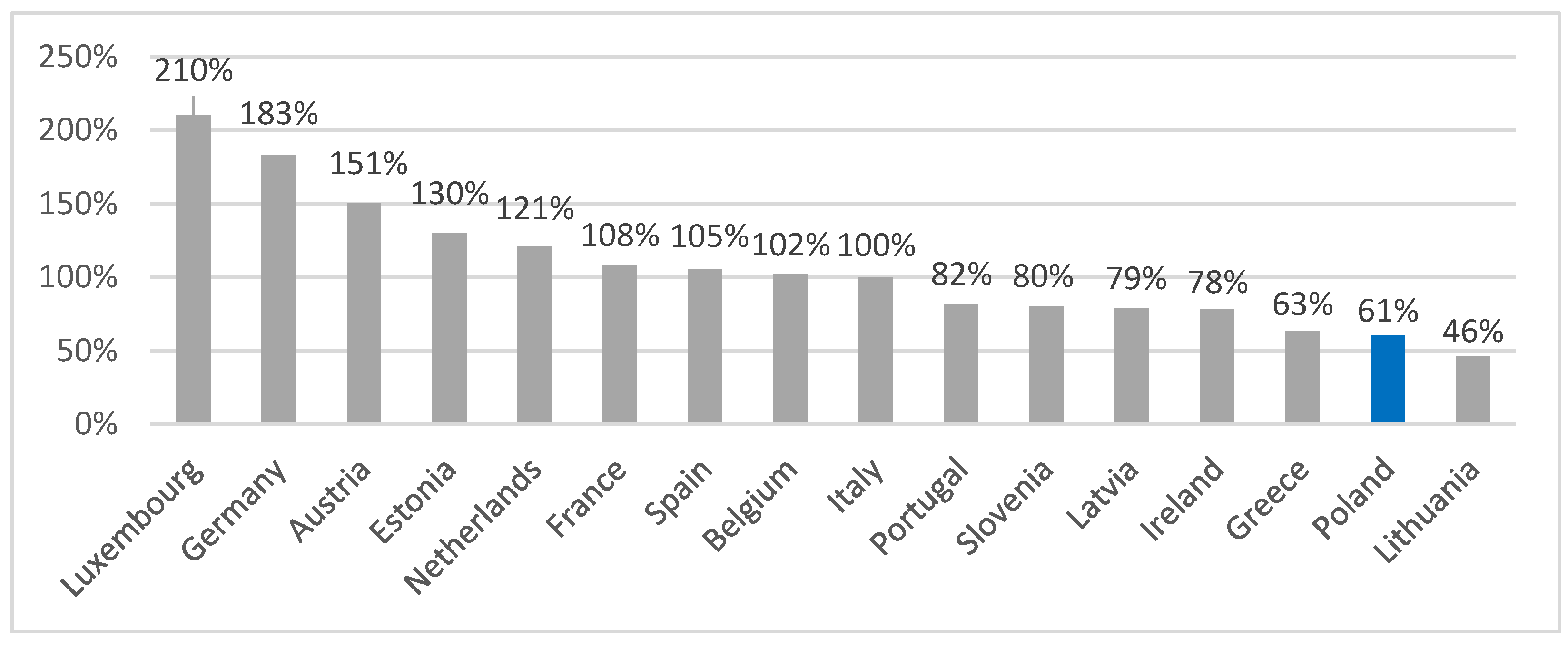

High share of debt instruments. As shown in

Figure 3, the Polish banking sector has one of the highest shares of debt instruments among bank assets in Europe. Consequently, the banking sector is no longer a credit sector, as it is equally strongly involved in financing debt instruments. The banking tax formula, penalising the credit activity of banks and the increasing legal risk related to credit activity, means that Polish banks are largely involved in financing debt instruments. Their share in the assets of Polish banks reached 34.6% at the end of June 2024, placing the Polish banking sector in first place among the European banking sectors.

High excess liquidity of the sector. In the Polish banking sector, the ratio of loans to the non-financial sector to non-financial sector deposits at the end of the first half of 2024 reached 60.6%, positioning the Polish banking sector in the penultimate place among European banking sectors, as shown in

Figure 4.

A low share of corporate loans. At the end of June 2024, the corporate loan portfolio reached PLN 398 billion, similar to the end of 2021. In nominal terms, this portfolio has not grown for 2.5 years. In relation to GDP, their share fell to 11.3%, which is the lowest level since 2010. As a result, the real value of the corporate loan portfolio places the Polish banking sector in the penultimate position among the European banking sectors. A lower ratio of corporate loans to GDP is recorded only in Lithuania’s banking sector.

Lending Conservativeness. Polish banks are generally conservative in their lending practices, focusing on creditworthiness and adhering to strict lending standards. This cautious approach has helped maintain stability, even despite global economic uncertainty.

High level of innovation in the banking sector. The Polish banking industry stands out for its strong implementation and usage of modern technologies. In Poland, users of banking services are eager to use online and mobile banking, which supports the development of new financial products, such as online loans, contactless payments, and BLIK payments. In Europe, Poland is the leader in terms of penetration of online and mobile banking. In Poland, there has been a rapid increase in cashless payments and the use of payment cards, as well as contactless technologies. Compared to many European countries, Poland has one of the highest rates of adoption of modern payment technologies. Poland is one of the leading European countries in terms of the number of developing Fin-tech companies that offer innovative financial solutions, such as micropayments, online loans, or modern investment tools. This distinction distinguishes Poland from other European countries, where finance technologies do not develop at the same pace. The development of FinTech companies and digital-only banks has increased competition in the Polish market. According to Deloitte, the Fin-tech market is widely regarded as a leader in banking innovation and electronic payments (

Deloitte, 2016). Revolut, N26, and Alior Bank’s digital banking services are examples of how unconventional financial institutions are challenging established players.

In recent years, an important topic in the banking sector has been, and still is, the issue of Swiss franc (CHF) loans. Individuals decided to take out mortgages in this currency, and due to exchange rate instability, the burden became almost impossible to bear. Governments have taken various initiatives to solve this problem, which has been associated with the risk for banks, which have had to face increasing costs resulting from numerous court cases and potential claims. Other European countries do not struggle with the same problem to such an extent, although they also have loans in foreign currencies. CHF loans were both an opportunity and a threat to the Polish banking sector. In one respect, they enabled an increase in bank lending and higher margins, but at the same time they led to legal risks related to court cases of CHF-loan-users, financial problems due to higher reserve costs or a decrease in the value of bonds, and also caused greater regulatory uncertainty due to government interference in order to protect the interests of both parties (

ESRB, 2023).

Another significant factor that recently influenced the banking sector was the COVID-19 pandemic. As reported by the Polish Financial Supervision Authority in its “Information on the banking sector in 2021”, the main point that the sector focused on was the recovery of the Polish economy from the COVID-19 pandemic and monitoring the legal risk related to the portfolio of mortgage-secured foreign currency housing loans. This year, the Polish Financial Supervision Authority has been taking actions to strengthen banks’ capital base in order to increase the banking sector’s security. According to the report, the most crucial factors influencing banks’ results included, among others (

UKNF, 2022, p. 3):

Acceleration of lending (especially real estate loans for households);

Three-fold increase in the reference rate by the Monetary Policy Council (MPC), respectively: on October 7 (by +0.40 p.p.); November 4 (by +0.75 p.p.), and December 9 (by +0.50 p.p.) to 1.75%;

A significant increase in the number of court cases related to foreign currency mortgage loans, causing a significant increase in the level of reserves of banks exposed to this risk;

Acceleration of the process of entering settlements by borrowers with foreign currency mortgage loans and the resulting process of converting foreign currency loans into PLN.

4. Empirical Studies in the Literature and VAR Analysis for Credit Markets in the Polish Banking Sector

By considering the theoretical framework and the data regarding the NPL ratio and credit ratio, it may only be possible to determine whether the interaction of the NPL ratio, which represents risk, and the credit ratio, which represents credit rationing, is in accordance with the structure predicted by the theory by conducting an econometric study for the Polish banking sector.

It can be stated that there are some studies concerning this subject, including empirical analyses of banking systems, for example, in Turkey, Caribbean nations, or Italy. Some of their examined variables, their type of analysis performed, and their results can be mentioned as follows.

Müslümov and Aras (

2004) analyzed the causality relationship between the NPL ratio and the total loans ratio with the Granger causality test by using the quarterly data between 1992:4 and 2001:4 time series data regarding NPL ratios and total credit to total assets ratios of the Turkish Banking Sector in order to determine whether there is a credit rationing due to the NPL ratio or not. A negative correlation is observed between non-performing loans and total loans. When the non-performing loans ratio increases, the ratio of total loans decreases. These findings show that the credit rationing mechanism is valid in Turkey and that banks face adverse selection, limiting their loans in order to reduce their losses.

Tracey and Leon (

2011) present an analysis examining the effect of Non-performing Loans (NPLs) on the growth of loan portfolios in three Caribbean nations: Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago. The authors use a threshold model to assess how banks respond to rising NPL ratios, positing that lending behavior changes significantly once NPLs exceed a certain level, potentially restraining economic activity. The balance sheet data of the commercial banking system of Jamaica (from 1996 Q1 to 2011 Q2) and Trinidad and Tobago (from 1995 Q3 to 2010 Q4) were used in this study. It was found that when NPLs/Loan ratios are high, banks become more risk-averse in loan granting.

Cucinelli (

2015) examines the lending behavior of banks during the period 2007–2013 of the financial downturn. The primary aim of the study is to understand whether the increase in credit risk leads banks to lower their lending activities or not. The study used fixed effect and OLS regression analyses on a sample of 488 Italian banks using annual data from 2007 to 2013. The study clearly shows that credit risk has a negative impact on bank lending behavior. This effect is demonstrated by both NPLs and the loan loss provision ratio measurements. The increase in non-performing loans forces banks to restrict their credit limits and thus to a slowdown in the rate of increase in gross loans. This shows that banks take less risk due to the deterioration in their past loan portfolios. As a result, based on the Italian banking sector’s data, it is seen that the increases in credit risk of banks in the past years (especially measured by non-performing loans and loan provisions) negatively affect their lending behavior.

Burlon et al. (

2016) offer indicators of corporate credit rationing in the term loan market for Italian non-financial companies. The authors conclude that credit rationing is mostly explained by the increased risk of non-performing loans faced by lenders and the collateral provided by borrowers to obtain bank loans.

Accornero et al. (

2017) investigated the relationship between NPLs and bank credit supply in Italy from 2008 to 2015 and analyze the dataset of borrower loans of non-financial firms and Italian banks’ balance sheets to determine if a rise in NPLs negatively impacts a bank’s ability to lend. This study yields two main results regarding the relationship between NPLs and bank credit supply in Italy during the analysis period. The study finds that the level of NPL ratios, by itself, does not causally influence bank lending behavior. The observed negative correlation between NPL ratios and credit growth is primarily driven by firm-related factors, such as changes in firms’ conditions, profitability, investment opportunities, and contractions in their demand for credit. Once these demand-side factors are properly accounted for, a bank’s lending behavior appears unrelated to its NPL ratio.

Based on theoretical and empirical studies, it is possible that credit supply and risky loans in the economy can mutually affect each other dynamically. In cases where two economic variables can dynamically affect each other, the structure of this effect can be determined by the VAR analysis.

In some of the theoretical studies on credit rationing, it is also stated that credit rationing can be done depending on the risk in the market, but independently of the interest rate. For this reason, the empirical analysis is planned to be carried out between NPL ratios, which are one of the ratios that indicate risk in credit markets, and the ratios of loans to total loans, representing credit rationing.

As mentioned in the theoretical studies in the literature, since the majority of the variables affecting credit rationing cause credit rationing by affecting riskiness and credit rationing can be performed without changing interest rates, riskiness, which might theoretically represent the majority of these variables, was taken into account. The relationship between NPL ratios, which may represent riskiness, and credit rationing was strived to be analyzed.

Our study aims to determine the dynamic relationship between riskiness and credit rationing in the Polish economy. In order to make this determination, NPL ratios representing riskiness and the ratio of total loans to total assets representing credit rationing were analyzed. Since the data regarding these variables for the Polish economy are available on a quarterly basis from 2009 Q1, which is the earliest period that the data are available, to 2023 Q3. The information on the variables used in the analysis is given in

Table 3. Thus, the dataset for this study includes 59 observations on a quarterly basis between Q1 2009 and Q3 2023 (

Helgi Library, n.d.).

The Vector Autoregression (VAR) model developed by

Sims (

1980) is broadly applied to analyze the dynamic effect of random disturbances on a system of variables in an interrelated time series. The application of VAR is a model that treats every intrinsic variable in the system as a function of the lagged values of all intrinsic variables in the system. (

Brahmasrene et al., 2014). The coefficients obtained in the VAR model are generally not interpreted, and the dynamic relationships between the variables are determined by impulse-response and variance decomposition analysis.

The mathematical representation of a VAR model with two variables is shown as follows:

In the model, (

P) represents the length of the delays and (

v) represents the error terms. The time series of the variables included in the VAR analysis must be stationary. For this reason, time series of

Yt and

Xt must be stationary in the model. If this model is applied to time series analysis in our study, the NPL ratio and the credit ratio for the Polish banking sector series must be stationary. For this reason, the Augmented Dickey Fuller Tests (ADF Tests) were performed to show the stationarity of the time series in

Table 4. This table shows the results of the ADF unit root test. According to the results of the performed unit root test; it was determined that series, named the ratio of bank loans to bank assets at I(1) level and ratio of NPL to total loans at I(0) level are stationary.

Before the impulse response analysis, at this stage of the study, VAR lag order selection criteria were used to determine the most appropriate lag length, and the most appropriate lag length was determined as lag level 2 according to

Table 5.

Diagnostics of the VAR model and related test results, regarding heteroskedasticity, can be seen at the following in

Table 6.

The VAR Residual Heteroskedasticity Test assesses whether the variance of the residuals from the VAR model is constant over time (homoskedastic) or if it changes (heteroskedastic). Heteroskedasticity can lead to inefficient coefficient estimates and incorrect standard errors, affecting the validity of inferences to be made. The results of the VAR Residual Heteroskedasticity Test determine that there is no significant evidence of heteroskedasticity in the VAR residuals, due to the fact that the Joint Test results are Chi-sq(30) = 24.76722, p-value = 0.7363, and the p-value is greater than the conventional significance levels 0.05 or 0.10. Therefore, it can be stated that the variance of the errors is constant and the standard errors and hypothesis tests derived from the VAR model are likely to be reliable.

The VAR Residual Serial Correlation LM test is used to determine if there is any remaining serial correlation (autocorrelation) in the residuals of the Vector Autoregression (VAR) model.

Regarding the VAR Residual Serial Correlation Test,

Table 7 can be examined. The presence of serial correlation in the residuals indicates that the VAR model might not be adequately capturing all the dynamic relationships in the data, which could lead to inefficient coefficient estimates and incorrect standard errors.

The test results show that there is no significant evidence of serial correlation in the residuals of our VAR Model at the tested lags; due to the fact that p-values are greater than common significance levels 0.05 and 0.10, which means that we fail to reject the null hypothesis that there is no serial correlation at the tested lag. This result validates the chosen lag length for our VAR model and supports the assumption that our coefficient estimates are efficient and our standard errors are reliable for hypothesis testing.

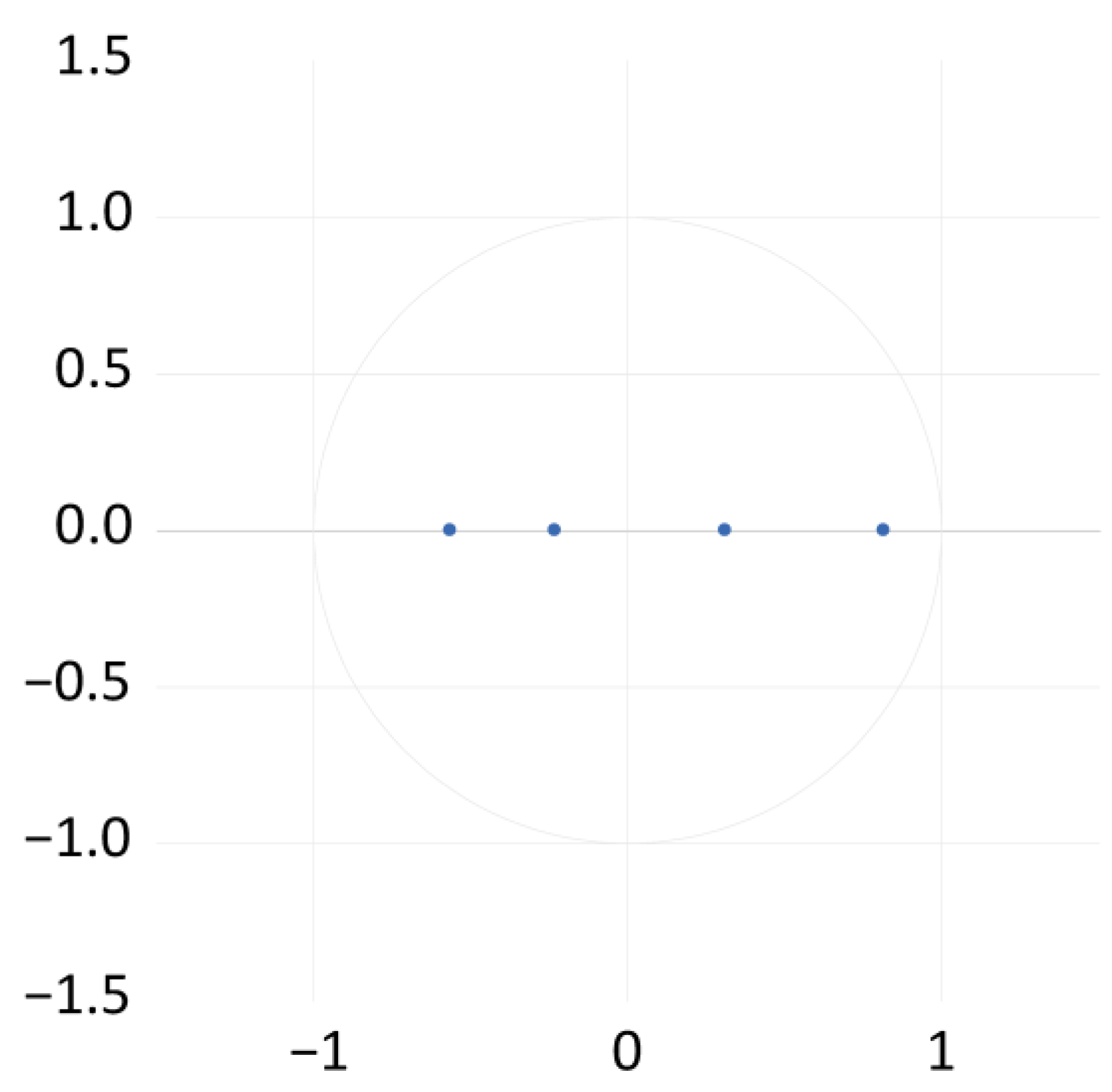

Regarding the stability of the model, the Inverse Roots of the AR Characteristic Polynomial Graph can be examined in

Figure 5.

Figure 5, titled “Inverse Roots of AR Characteristic Polynomial,” is used to assess the stability of the VAR model. For a VAR Model to be stable, all the inverse roots of its characteristic polynomial must lie inside the unit circle. For stability interpretation, the inverse roots of the characteristic polynomial should ideally lie inside the unit circle for the VAR model to be stable. In this case, the points appear within the unit circle, suggesting that the VAR process is likely stable.

The coefficients obtained in the VAR model are generally not interpreted, and the dynamic relationships between the variables are determined by impulse-response analysis and variance decomposition analysis. The variables themselves in the system or the reactions of other variables to “one standard error” shocks are important for the analysis. Error terms are often used in time series models to represent these “one standard error” shocks. As a result, it is expressed as the response or reaction of each variable included in the model in response to itself and the errors of other variables. In the impulse-response analysis, there is an effect for the variable that gives the “one standard error” shock, while there is a reaction for the variable that receives the shock. This analysis is based on the relationship between different variables, where one of the variables causes the other. The effect of shocks is examined by impulse-response analysis and variance decomposition analysis, which are components of the VAR analysis.

Regarding the Impulse Response Analysis, the reactions of all variables in the system to a standard error shock of the analyzed variables themselves or other variables are measured, and the measurements are graphed. Thus, the response or reaction of each variable included in the model in response to its own or other variables’ standard errors is revealed. In the impulse-response analysis, there is an impulse for the variable that gives a standard error shock, while there is a response for the variable that receives the shock.

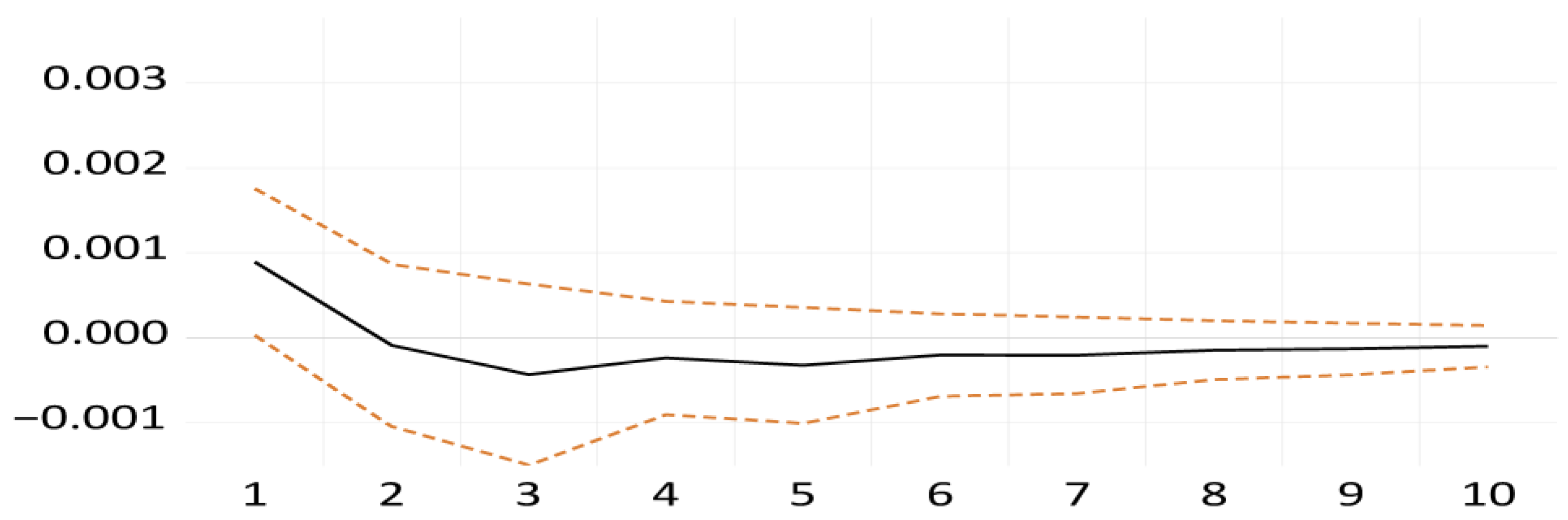

Figure 6 illustrates the response of credit rationing to non-performing loans over 10 periods.

In other words, the graphic shows the reaction or response of credit rationing when the NPL ratio changes. In

Figure 6, the horizontal axis, labelled from 1 to 10, represents the number of periods, and the vertical axis represents the magnitude of the response of credit rationing. The black line starts very close to zero in period 1. This suggests that an unexpected one-standard-deviation shock to the NPL ratio has almost no immediate impact on credit rationing. An unexpected one-standard-deviation increase in the NPL ratio appears to have no statistically significant impact on the change in bank loans to bank assets over the 10 periods following the shock. The response is very close to zero for all periods, and at no point does it significantly deviate from zero, due to the fact that the confidence interval always includes zero. Therefore, it can be claimed that shocks to non-performing loans do not significantly influence the level of bank loans relative to bank assets.

Figure 7, presented below, illustrates the response of non-performing loans to the credit ratio over 10 periods.

Figure 7 shows the reaction or response of the NPL ratio when the credit ratio changes. In this graph, the horizontal axis, labelled from 1 to 10, represents the number of periods, and the vertical axis represents the magnitude of the response of the NPL ratio. According to the graph above, the unexpected one-standard-deviation increase in the credit ratio appears to have no statistically significant impact on the change in the NPL ratio over the 10 periods following the shock. Therefore, it can be claimed that shocks to the credit ratio do not significantly influence the level of the NPL ratio.

VAR analysis also offers the option to display variance decomposition in tabular form. The variance decomposition analysis shows the rate at which the shock that occurs in the error term of one variable is explained by other variables. Variance decomposition is one of the methods used to examine the reasons for the change in the series and is obtained from the moving averages part of the VAR model. The method shows the sources of shocks that occur in the variables themselves and in other variables as a percentage. It shows what percentage of a change in the variables in the model is caused by itself and what percentage is caused by other variables (

Enders, 1995).

According to the variance decomposition analysis, the effect of the NPL ratio on credit rationing is even below the 1 percent level for 10 periods.

Table 8 shows that the change in bank loans to bank assets is almost entirely driven by its own past shocks. Shocks to non-performing loans have a negligible impact on credit rationing. On the other hand, while shocks to the change in bank loans to bank assets do have a small but consistent explanatory power (around 7%) over the variation in non-performing loans, the variations in non-performing loans are primarily driven by their own past shocks.

These results show that a relatively weak causal relationship exists from the credit ratio to the NPL ratio and virtually no causal relationship in the other direction, within the specified VAR model and Cholesky ordering. This situation aligns with the impulse response graphs, showing non-significant responses.

Granger Causality Analysis, presented in

Table 9, can also be another part of VAR analysis as a valuable statistical tool for understanding dynamic relationships between time series variables by assessing their predictive power.

This analysis is a formal way to assess if one variable “Granger-causes” another in the context of a Vector Autoregression (VAR) model. Granger causality means that past values of one variable help in predicting the future values of another. For each dependent variable in the model, the Granger Causality Test checks if the lagged values of an “Excluded” variable (or a block of excluded variables, if there were more than two) have a statistically significant impact on the dependent variable.

The first section of Granger Causality Analysis tests whether the ratio of NPL to Total Loans causes bank loans to bank assets. In the first section, the Chi-square statistic is 0.036331 with a p-value of 0.9820, which is higher than the significance levels of 0.05 or 0.10 and indicates that there is no statistically significant evidence that the NPL ratio causes credit rationing. This means that past values of the non-performing loans ratio do not help predict the change in the bank loans to bank assets ratio.

The second section of Granger Causality Analysis tests whether the ratio of bank loans to bank assets causes the ratio of NPL to total loans. In the second section, the Chi-square statistic is 3.547966 with a p-value of 0.1697, which is higher than the significance levels of 0.05 or 0.10 and indicates that there is no statistically significant evidence that the ratio of bank loans to bank assets causes the ratio of NPL to total loans. This means that past values of the ratio of bank loans to bank assets do not help predict the change in the ratio of NPL to total loans.

In conclusion, based on these Granger causality tests, there is no statistically significant evidence of a predictive relationship in either direction between D(Bankloans_to_Bankassets) and Npl_to_Total_Loans within our VAR model. These Granger Causality test results are consistent with the Impulse Response Functions (IRFs) and Variance Decompositions (VDs) previously provided.

5. Conclusions

There are many factors that affect credit rationing, including those related to risk. In this study, the effect of riskiness represented by NPL on credit rationing was strived to be tested by VAR analysis using the quarterly credit market data of the Polish banking sector between 2009 Q1 and 2023 Q4. According to the result of VAR analysis, made in this study, Since there is no result that NPL ratios affect credit rationing, it can be claimed that the risky structure, represented by NPLs in the credit market of the Polish banking sector, might not be considered as one of the determinants of credit rationing in the Polish banking sector.

According to the mentioned Jaffe and Russell’s study, credit rationing, which is expected to be affected by riskiness, is a phenomenon that occurs due to the effect of riskiness on profitability. In other words, especially when the risk related to default increases, if this risk increase does not reduce profitability, credit rationing may not be made. In addition, as stated in the theories of both Jaffe and Russell and Stiglitz and Weiss, if collaterals are required in credit granting, credit rationing decreases. This may also apply to the credit markets of the Banking Sector of the Polish Economy. This situation can be recognized when looking at the annual data of the relevant variables in the credit markets of the banking sector in the Polish Economy between 1998 and 2023. Credit rationing does not change according to riskiness. There is profitability that varies in the same way as loan ratios, but profitability does not change according to riskiness. Looking at the general outlook of the Polish banking sector, it is a stable banking sector that is not large compared to GDP is observed, and debt instruments are more than loans in total assets proportionally. In addition, the low share of commercial loans in total loans, very strict loan granting strategies, the predominance of housing loans in total loans, and the fact that houses purchased through loans constitute direct collateral may prevent banks from encountering a risky portfolio. Therefore, it may be possible that a risk-sensitive credit granting strategy may not be followed by the banking sector. Therefore, it is possible to say that credit granting policies in the credit market are similar to the situation predicted by studies of Jaffe and Russell, as well as Stiglitz and Weiss.

On the other hand, as mentioned in this study, the necessity of high collaterals as a loan-granting condition leads loan users to misuse loans and creates a moral hazard. However, banks can make low-cost monitoring due to the fact that housing loans are given conditional on the purchase of housing, banks have residential ownership until the end of the loan repayment period, and the banking sector has advanced innovations, fin-tech, and a competitive structure. Since the house purchased with the loan is owned by the bank until the end of the loan repayment period, the risk is greatly reduced, and the banking sector can control the risk with low monitoring costs. In addition, the existence of low indebtedness rates of Polish households compared to other eurozone countries makes it possible for banks operating in the Polish banking sector to follow a risk-insensitive credit granting strategy in accordance with the theory of Bester and Williamson mentioned in this study.

Although the Polish banking sector’s NPL ratio is 4% and higher than 2%, which is the EU average, the Polish banking sector seems insensitive to the NPL ratio. The reason why the Polish banking sector is not very sensitive to the risky structure in credit markets due to non-performing loans might be the ratio of credits to total assets, which is lower than the share of debt instruments in total assets and the higher proportion of housing credits, having significant collateral, in total credits.

As per Mishkin, Bernanke, and Gertler, the influence of monetary policy on the economy operates not only through interest rates but also through the availability of credit. For this reason, robust financial regulation and timely central bank intervention play a vital role in containing systemic risk. Consequently, in the Polish banking sector, the effectiveness of monetary policy depends not only on interest-rate adjustments but also on the regulatory environment that shapes credit availability. In practice, credit conditions are strongly influenced by monetary policy and supervisory frameworks (such as capital requirements, interest rates, the broader macroeconomic situation, and the guidelines of the Polish Financial Supervision Authority (UKNF)—all of which directly affect banks’ lending capacity and the volume of credit granted. Additionally, more factors, such as borrower creditworthiness or interest rate volatility, might be considered to be more influential in credit rationing conducted by banking institutions. These factors constitute a strong basis for increasing credited clients’ solvency security in banking procedures. NPL is seen as a measure of the past quality of a loan portfolio rather than a direct tool for shaping current credit policy. Banks make credit decisions based on risk, liquidity, profitability and regulations. A high level of NPL may make banks cautious, but it does not oblige them to restrict lending; thus, it is rather an internal risk management strategy.

Banks in Poland tend to adopt a passive “waiting” strategy, which means that instead of actively selling NPL portfolios or restructuring them, they prefer to maintain the balance sheets, “hoping” for an improvement in the overall economic situation. Restructuring is problematic for two reasons: many NPLs are held by individuals, making it difficult to recover or sell quickly (unlike large corporate portfolios, which are easier to sell). Secondly, a significant percentage of loans are mortgages, making them a strategic asset on balance sheets. Therefore, banks have a strong incentive to hold these portfolios, even if some of them are distressed. Selling or restructuring mortgage NPLs could significantly impact asset values and capital ratios.

The reason why banks in the Polish banking sector do not follow a risk-sensitive credit granting strategy may also be due to some regulations in the banking sector and EU regulations. In some other countries, for example from the euro zone, banking supervision led by the European Central Bank (ECB) actively enforces NPL reduction by imposing limits and requirements for coverage with reserves. In Poland, the UKNF takes a softer approach, which may explain the lower pressure placed on banks. It is believed that the fact that the EU NPL Directive 2021/2167, which has not yet been formally implemented in Poland, may explain why the Polish banking sector reacts less dynamically to the NPL problem than banks in countries that have already adapted their regulations to EU requirements. It is, however, important to remember, that this directive, 2021/2167, regulates the activities of entities servicing NPLs but does not impose direct restrictions on banks in terms of granting new loans. Its aim is rather to organize the secondary market for receivables and protect consumers. On the other hand, in the preamble to this directive we will find fragments that clearly indicate expectations toward credit institutions and Member States. One of them indicates that “The development of a comprehensive strategy to address the problem of non-performing loans is a priority for the Union. Although the primary responsibility for addressing the problem of non-performing loans lies with credit institutions and Member States, there is also a clear EU dimension in reducing the currently recorded volumes of non-performing loans” (

Directive UE 2021/2167, 2021).

In the Polish banking sector, if the ratios of housing loans in total loans decrease and NPL ratios increase, there would be collateral based rationing and following an approach sensitive to the risk of default would be an appropriate and correct strategy for the banking sector.