Abstract

Climate change is expected to reduce coffee yields and intensify infestations by Hypothenemus hampei, the most destructive coffee pest worldwide. Strengthening host plant resistance offers a sustainable approach to mitigate these impacts. This study aimed to characterize F3 progenies derived from crosses between Castillo®—a variety with high agronomic performance and resistance to Hemileia vastatrix—and Ethiopian Coffea arabica introductions exhibiting antibiosis to H. hampei for agronomic traits and, for the first time, modeled reductions in H. hampei infestation under projected climate change scenarios. Thirteen F3 progenies with medium plant stature, rust resistance, and high productivity were selected using a 6 × 7 lattice design. Antibiosis was quantified under controlled conditions by infesting individual coffee beans with a single female borer and validated under field conditions by artificially infesting productive branches with 100 females. Relative to the susceptible control, oviposition decreased by 18.0–25.8% under controlled conditions and by 24.1–69.8% in the field. To anticipate progeny performance under warmer conditions, simulation modeling integrating laboratory and field data under Neutral and El Niño scenarios for the Naranjal and Paraguaicito experimental stations, indicated that progenies exhibiting 34–55% reductions in oviposition would maintain infestation below the economic damage threshold (5%) throughout the eight-month fruit development period. Progenies with the highest antibiosis (55%) would reach the action threshold (2%) only in the seventh month. These findings demonstrate the potential of antibiosis-based resistance to reduce insecticide use and strengthen integrated pest management under projected climate change scenarios.

1. Introduction

Recent taxonomic revisions indicate that the genus Coffea comprises nearly 132 species [1]. Among these, Arabica (Coffea arabica L.) and Robusta (Coffea canephora Pierre ex A. Froehner) dominate global production and trade, contributing an estimated USD 245.6 billion to the international coffee market [2] and supporting the livelihoods of nearly 25 million growers, most of them smallholders [3,4]. Arabica accounts for 56.6% of global production and is widely recognized for its superior sensory attributes [5]. It is typically cultivated at elevations of 950–1950 m a.s.l. under climatic conditions similar to those of its center of origin [6], with optimal annual mean temperatures of 18–21 °C [7]. In Colombia, Arabica coffee is the most economically significant agricultural product and the second-most traded commodity after oil, with an estimated harvest value of COP 16.1 billion in 2024 [8].

Climate projections indicate that Arabica is highly vulnerable to increases in air temperature of 1.7–2.5 °C and to broader regional warming trends [9,10]. Such changes are expected to shift cultivation to higher elevations, reducing the extent of suitable coffee-growing areas, even within Ethiopia, the species’ center of origin [11,12,13,14,15,16]. Rising temperatures are also anticipated to lower global coffee production [17,18] and increase susceptibility to the coffee berry borer (Hypothenemus hampei Ferrari), whose reproductive rate and geographic distribution expand under warmer conditions [12,19,20].

H. hampei is the most destructive insect pest of coffee in Colombia and in nearly all coffee-producing countries, except Nepal and Australia [21]. Fertile females bore into berries 120–150 days after flowering, once dry matter exceeds 20% [22], creating tunnels and galleries where they oviposit [23]. Emerging larvae feed on the endosperm, reducing parchment weight [24], and infested berries often exhibit sensory deterioration due to fungal contamination [25,26,27]. Because females remain inside the berry and oviposit over extended periods (7–50 days), all life stages may coexist within a single fruit [28]. Under controlled conditions, the insect completes its life cycle in 28 days at 26 °C in parchment beans with 40% moisture [29], whereas, in the field, at 20.7–21.6 °C, development requires 45–60 days [30].

Integrated pest management (IPM) strategies developed by Cenicafé have successfully maintained H. hampei populations below the economic damage threshold [31]. However, projected climate change scenarios characterized by higher temperatures and more frequent and intense El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) events [32] present new challenges. In Colombia, ENSO events result in reduced rainfall and increased air temperature, solar radiation, and brightness across most coffee-growing regions [33]. These conditions enhance reproductive capacity and shorten the doubling time of H. hampei [19,34], particularly in low-elevation and warmer cultivation zones [35].

Host plant resistance (HPR) is a promising complementary IPM strategy. HPR relies on genetically inherited, constitutive plant traits [36] and encompasses three primary mechanisms: antixenosis (reduced host attractiveness), antibiosis (adverse effects on insect development, survival, or fecundity), and tolerance (ability to withstand herbivory without substantial yield loss) [36,37]. HPR has proven highly effective and economically advantageous in many crops [38,39,40], reducing pest damage and production costs while improving yield and quality [38,41]. Despite these advantages, progress in breeding coffee varieties resistant to key pests, including H. hampei, has been limited [42,43,44,45], mainly due to scarce resistance sources, long generation times, and the complex nature of resistance mechanisms [41].

Following the introduction of H. hampei into Colombia [46], extensive screening of C. arabica germplasm identified Ethiopian introductions from Kaffa with pronounced antibiosis effects [29]. These genotypes markedly reduced insect fecundity, resulting in lower net reproductive and intrinsic growth rates and longer population doubling times relative to the susceptible variety Caturra [47]. Importantly, these Ethiopian accessions did not participate in the domestication of C. arabica and therefore constitute a valuable genetic reservoir for broadening the species’ narrow genetic base [48,49]. Collected from the humid forests of Kaffa, Illubabor, and Gojjam, west of the Great Rift Valley, these introductions evolved under prolonged geographic isolation, maintained mainly until the nineteenth century due to the Rift Valley barrier and the delayed political integration of Kaffa [50].

Genetic analyses further show that Kaffa accessions cluster within Group I, together with other western Ethiopian introductions, and remain clearly differentiated from eastern accessions [49]. These western introductions possess desirable phenotypic and genetic attributes, including incomplete resistance to Hemileia vastatrix Berkeley and Broome [51], resistance to Meloidogyne incognita Kofoid and White [52] and Colletotrichum kahawae JM Waller and PD Bridge [48], drought tolerance [53], and antibiosis to H. hampei [21,42]. Such traits distinguish them from intensively domesticated Arabica cultivars and from eastern Ethiopian accessions, which exhibit more pronounced genetic bottlenecks due to Arabica’s predominantly self-pollinating reproductive system [49]. This erosion of gene diversity likely contributed to the loss of resistance to pests and diseases and reduced tolerance to abiotic stressors, as observed for insect resistance in domesticated C. arabica [54].

To introgress antibiosis into commercial germplasm, a conventional breeding program was initiated and advanced through the F1 and F2 generations. Building on these efforts, the present study aimed to characterize the F3 progenies derived from these F2 populations for key agronomic traits and, for the first time, to model reductions in H. hampei infestation under projected climate change scenarios.

2. Results

2.1. Agronomic Variables

Across the 36 F3 progenies, plant height at 24 months after field establishment ranged from 117.2 to 202.3 cm (Table 1). Thirteen progenies (52, 57, 70, 106, 164, 199, 220, 253, 261, 263, 292, 304, and 340) exhibited shorter mean heights (117.2–140.9 cm; p ≤ 0.0001) than the commercial controls, corresponding to reductions of 22.0–45.7 cm relative to Caturra (mean: 162.9 cm) and 20.0–43.7 cm relative to Cenicafé 1 (mean: 160.9 cm) (Table 1). In contrast, progenies 42 and 534 exhibited the tallest mean heights (177.5 and 202.3 cm, respectively), both exceeding those of the commercial controls (p ≤ 0.0001). The remaining 21 progenies (144.7 to 175.4 cm) did not differ from the controls (p ≥ 0.05) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Mean values, standard errors (SE) for plant height and yield, and percentage of plants with Hemileia vastatrix incidence ≤ 3 on the Eskes and Toma-Braghini scale for 36 F3 progenies and the commercial controls.

Cumulative yield over three consecutive harvests ranged from 5.9 to 13.0 kg of cherry coffee plant−1 (Table 1). Fourteen progenies (15, 21, 304, 311, 324, 363, 371, 373, 391, 406, 416, 489, 534, and 699) produced higher yields (p ≤ 0.0001) than Caturra (mean: 6.7 kg plant−1) and Cenicafé 1 (mean: 8.0 kg plant−1), with gains of 3.9–6.3 kg and 2.6–5.0 kg plant−1, respectively. Six additional progenies (42, 128, 220, 297, 354, and 452) yielded 9.3–10.3 kg plant−1, exceeding Caturra. The remaining 16 progenies produced yields comparable to those of the commercial controls (p ≥ 0.05).

Percentile analysis of H. vastatrix incidence revealed that fifteen F3 progenies (21, 42, 46, 53, 57, 70, 106, 263, 363, 371, 452, 489, 534, 698, and 699) were resistant, with 70–97% of plants scoring ≤ 3, on the disease-incidence scale [55]. The remaining twenty-one progenies were susceptible, with only 3–67% of plants scoring ≤ 3 (Table 1).

2.2. Antibiosis Assessment Under Controlled Conditions

Table 2 summarizes the mean total number of H. hampei developmental stages for the thirteen rust-resistant F3 progenies (70–97% of plants scoring ≤ 3) and their controls across one to six evaluation periods. In all cases, the F3 progenies exhibited fewer developmental stages than the susceptible control, with reductions of 18.0–25.8% and an overall mean reduction of 20.5%.

Table 2.

Mean values, standard errors (SE), and percentage reduction in Hypothenemus hampei developmental stages of F3 progenies and their respective susceptible controls under controlled conditions.

When group F3 progenies and controls were compared across evaluation periods, the contrast test (Fc = 210.6; p < 0.0001) indicated fewer developmental stages per bean in the progenies, with >95% confidence, which corresponds to an estimated 19.2% reduction in oviposition (Table 2).

2.3. Antibiosis Assessment Under Field Conditions

Across evaluation periods 1–5, progenies consistently exhibited fewer H. hampei developmental stages than their susceptible controls (Table 3). Reductions ranged from 24.1% to 69.8%, with an overall mean reduction of 42.4%.

Table 3.

Mean values, standard errors (SE), and percentage reduction in Hypothenemus hampei developmental stages of F3 progenies and their susceptible controls under field conditions.

The contrast test for the group F3 progenies (Fc = 383.16; p < 0.0001) further confirmed differences in favor of the progenies, with >97% confidence, corresponding to a 35.2% reduction in oviposition (Table 3).

Agronomic and antibiosis traits under controlled and field conditions for the thirteen selected progenies chosen for rust resistance, medium stature, high productivity, and antibiosis are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Mean values and standard errors (SE) of agronomic traits and antibiosis parameters, and percentage reduction in Hypothenemus hampei developmental stages in F3 progenies evaluated under controlled and field conditions.

2.4. Impact of the Reduction in H. hampei Developmental Stages in F3 Progenies on the Population Dynamics of the Pest

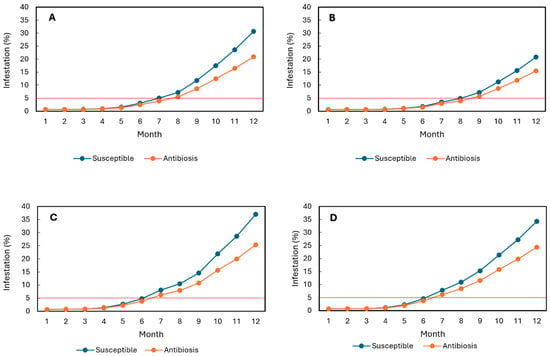

At the Naranjal Experimental Station, simulations indicated that progenies exhibiting an average 19% reduction in developmental stages under controlled conditions would reach the economic damage threshold (5% infestation) after seven months during El Niño and after eight months under Neutral conditions (Figure 1A,B). In contrast, the susceptible variety Caturra reached the economic threshold within seven months under El Niño and within eight months under Neutral conditions (Figure 1A,B).

Figure 1.

Simulation of Hypothenemus hampei infestation in F3 progenies exhibiting antibiosis (19% average reduction in total developmental stages under controlled conditions) and in the susceptible Caturra variety over a 12-month fruit development period. (A,B) Naranjal Experimental Station under El Niño and Neutral conditions, respectively. (C,D) Paraguaicito Experimental Station under El Niño and Neutral conditions, respectively. The red line indicates the economic damage threshold.

At the Paraguaicito Experimental Station, progenies exhibiting a 19% reduction in oviposition were predicted to reach 5% infestation between the sixth and seventh months under both climatic scenarios (Figure 1C,D), approximately one month earlier than at Naranjal under El Niño conditions. Caturra, however, reached the economic threshold within six months under both scenarios (Figure 1C,D). These results indicate that a 19% reduction in developmental stages is insufficient to maintain infestation below the economic threshold throughout the entire eight-month fruit development period at either station during El Niño events.

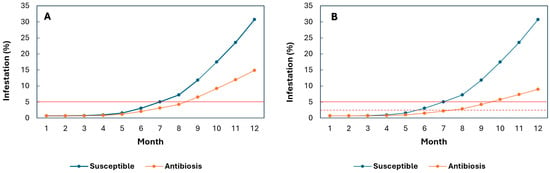

Because reductions in total developmental stages were substantially greater under field than laboratory conditions, simulations were also conducted using field-based reduction rates. Assuming 34–55% decreases in total developmental stages (Figure 2A,B), progenies at Paraguaicito during El Niño events were predicted to maintain infestation below the economic threshold for 8–9 months. In contrast, Caturra exceeded the threshold 1–2.5 months earlier at 34% and 55% antibiosis, respectively. For progenies exhibiting a 55% reduction, the action threshold (2%) was reached only after the seventh month, approximately one month before the main harvest (Figure 2B). Conversely, in Caturra, the action threshold was reached between the fifth and sixth months (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Simulation of Hypothenemus hampei infestation during El Niño events in F3 progenies exhibiting antibiosis under field conditions, and in the susceptible Caturra variety over a 12-month fruit development period. (A) At the Paraguaicito Experimental Station, F3 progenies showed an average reduction of 34% in the total number of developmental stages. (B) At the Paraguaicito Experimental Station, F3 progenies showed an average decrease of 55% in the total number of developmental stages. The solid red line represents the economic damage threshold, and the dashed red line indicates the action threshold (2%).

3. Discussion

Our results demonstrate that antibiosis was inherited in thirteen F3 progenies resistant to H. vastatrix, with 70–97% of plants scoring ≤ 3 on the incidence scale. These progenies reduced H. hampei reproductive fitness by 18.0–25.8% under controlled conditions (Table 2) and by 24.1–69.8% under field conditions (Table 3). Similarly, F2 plants previously reduced the total number of H. hampei developmental stages (eggs, larvae, prepupae, pupae, and adults) by 18.7–37.7% in laboratory assays and by 29.1–73.1% in the field [42]. Together, these findings confirm that selection based on antibiosis expressed under controlled conditions reliably predicts field performance, facilitating the identification of genotypes with reduced oviposition. The more substantial reductions observed under field conditions likely reflect insect exposure to fluctuating temperatures, which affect development, survival, and fecundity [56]. In contrast, constant laboratory conditions allow H. hampei to express its full reproductive potential. This study further demonstrates that antibiosis detected under controlled conditions is maintained and even enhanced in natural field environments due to stronger expression of inducible plant defense mechanisms.

Antibiosis in Ethiopian accessions has been linked to seed proteins, including protease inhibitors (PIs), some of which also function as storage proteins [57]. These compounds inhibit digestive enzymes, reducing amino acid availability for vitellogenesis and thereby decreasing oviposition while negatively affecting development and survival across life stages [58,59]. Antibiosis has been successfully incorporated into coffee breeding, as exemplified by the commercial hybrid Siriema AS1 (C. arabica × Coffea racemosa), which reduces larval survival of Leucoptera coffeella (Guerin-Meneville and Perrottet) and decreases leaf damage [45]. Similarly, 29 C. arabica × C. racemosa progenies expressed antibiosis to L. coffeella via reduced larval hatching [60], and antibiosis-based resistance has also been documented in C. canephora against Oligonychus ilicis McGregor [44].

Developing a composite variety composed of multiple progenies that combine antibiosis to H. hampei, resistance to H. vastatrix, medium stature, and high yield (Table 4) aligns with the genetic-diversity strategy of Cenicafé’s Coffee Breeding Program. This strategy led to the release of the Colombia variety more than four decades ago [61] and the Castillo® variety, which has been widely cultivated for over twenty years [62], both characterized by durable resistance to H. vastatrix. Similarly, the Ruiru 11 variety, whose rust resistance to H. vastatrix originated from eight F4 progenies derived from the ‘Caturra × Hybrid of Timor’ cross developed by Cenicafé [63], is among the most rust-resistant cultivars in the global coffee-trial network [64].

Selecting medium-statured F3 progenies enables higher planting densities and increased productivity per unit area. Five progenies (21, 363, 371, 489, and 699) yielded more than Caturra and Cenicafé 1 (p ≤ 0.0001), while progeny 452 yielded more than Caturra alone (Table 1). The remaining seven progenies produced yields comparable to commercial controls, confirming the high productivity of these 13 F3 progenies.

Modeling H. hampei population dynamics under field-derived antibiosis levels (34–55% reductions in developmental stages) indicated that, during El Niño events in Paraguaicito, total infestation would remain below the economic damage threshold (5%) throughout the eight-month fruit development period (Figure 2A,B). This trait would help maintain coffee production and prevent price penalties associated with deteriorated bean quality when infestation exceeds 5%. Progenies exhibiting the highest antibiosis (55%) would reach the action threshold (2%) only in the seventh month (Figure 2B), allowing harvest with minimal or no insecticide use. Reducing pesticide dependence enhances sustainability by lowering production costs and minimizing agrochemical inputs.

In contrast, susceptible commercial varieties with higher reproductive rates require insecticide applications 1–1.5 months earlier than antibiosis-bearing progenies (Figure 2), once infestation surpasses 2% and more than 50% of females penetrate fruits at positions A and B [31]. At this stage, fruits reach physiological maturity. They are fully susceptible to attack [65], resulting in reduced harvested weight and lower cherry-to-parchment conversion ratios from 5:1 to 8:1, requiring a greater quantity of cherry coffee to obtain 1 kg of dry parchment coffee [66]. Consequently, losses in yield and parchment weight range from 10.82% to 45.12% [24], accompanied by declines in market price as infestation increases [67], and sensory defects caused by microorganisms in bored beans [26,27].

Climatic records show that during strong El Niño events, maximum annual temperatures in Paraguaicito may rise by up to 1.6 °C [68]. Additionally, uneven rainfall distribution produces two pronounced drought periods: one between January and February, affecting the May harvest, and another between June and August (3.5–4.5 months after flowering), which can severely compromise fruit filling during the main November harvest. This period coincides with rapid fruit growth and the critical infestation window, which begins at ~20% dry matter content [65,69]. Under these conditions, progenies that exhibit antibiosis to H. hampei and high agronomic performance could help mitigate climate change–driven losses in both yield and bean quality, as demonstrated by the simulations conducted in this study (Figure 2). In contrast, climatic records from Naranjal indicate that during El Niño events, temperature increases (1.2 °C) and rainfall reductions (25%) are less pronounced than those recorded in Paraguaicito (31%) [68]. Moreover, the more evenly distributed rainfall at Naranjal supports fruit filling and stabilizes production [70], suggesting that this site may be less vulnerable to climate-related stress. These contrasting climatic patterns underscore the substantial environmental heterogeneity across Colombian coffee-growing regions and the variable impacts of rising temperatures on H. hampei infestation pressure.

Climatic data since 1950 indicate that the Colombian coffee region maintains mean annual temperatures of 18–21 °C, high cloud cover, and abundant rainfall exceeding 2000 mm in most years [68]. These conditions promote multiple flowering events, generating fruits at different developmental stages throughout the year [71] and providing a continuous food supply for H. hampei. Rising temperatures associated with climate change and El Niño–driven climatic variability are expected to increase both the number of individuals per generation and the annual number of generations, thereby complicating pest management, particularly at lower elevations.

These projections are consistent with observations from Aguadas (Caldas, Colombia), where lower elevations (<1500 m a.s.l.) exhibit higher infestation levels than higher elevations (>1700 m a.s.l.) due to warmer local temperatures [72]. Similar patterns have been documented in Hawaii, where farms below 1000 m a.s.l. show increased numbers of individuals per fruit and more generations per season at ~200–300 m, attributable to shorter developmental times at elevated temperatures compared with farms at 600–780 m [34]. In eastern Africa, increases in H. hampei generations have likewise been predicted for C. arabica across elevations of 900–1800 m a.s.l. [20], driven by an 8.5% rise in maximum intrinsic growth rate per 1 °C increase in temperature up to the optimal developmental threshold (26.7 °C), along with reduced developmental time across life stages [19].

Advancing the antibiosis-carrying F3 progenies to later generations (F4 and F5) and evaluating them in low-elevation coffee-growing regions where vulnerability to H. hampei is most significant due to higher temperatures [35,41] represents a sustainable strategy to strengthen coffee production in areas where this pest has historically constrained yields. Such progenies may also help compensate for the loss of climatic suitability for coffee cultivation in regions increasingly affected by climate change and escalating infestation pressure. A cultivar that consistently reduces the reproductive fitness of H. hampei will lower the number of individuals produced per generation, thereby maintaining pest populations below the economic damage threshold. This approach is economically viable, easily adoptable by growers, and compatible with existing integrated pest management strategies.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental Conditions, Plant Material, and Experimental Design

The study was conducted at the Naranjal Experimental Station of Cenicafé, located in Chinchiná, Caldas, Colombia, on the eastern slope of the Central Andes (4°58′57″ N, 75°36′13″ W). The site is situated at 1381 m a.s.l. and is characterized by a mean annual temperature of 21.4 °C, yearly precipitation of 2782 mm, and an average relative humidity of 77.5%.

The female parents consisted of five Castillo® progenies (CX.2710, CX.2178, CX.2848, CX.2391, and CU.1812), which exhibit desirable agronomic attributes, including intermediate plant stature, resistance to H. vastatrix, the most damaging disease affecting coffee production in Colombia and worldwide [73], and high yield potential [63]. The male parents comprised three Ethiopian Coffea arabica introductions (CCC.534, CCC.477, and CCC.470) characterized by tall stature, low yield, and the antibiosis trait, expressed as reduced oviposition and fewer H. hampei developmental stages relative to the susceptible variety Caturra [29]. The H. hampei females used for artificial infestations in laboratory and field assays were obtained from mass-rearing colonies maintained by Biocafé.

A total of 36 third filial generation (F3) progenies were evaluated for agronomic performance and antibiosis. These progenies were selected from F2 populations described by Molina et al. (2022) [42]. Four female parents and two commercial controls (Caturra and Cenicafé 1) were included, totaling 42 treatments. Genotypes were planted in June 2019 in a 2706 m2 plot at a density of 6666 plants ha−1 (1.5 m between rows × 1.0 m between plants), following a 6 × 7 lattice design. Each experimental unit consisted of a 12-plant row, with 10 effective plants per plot and three replicates per treatment, for a total of 30 plants. Ethiopian male introductions were excluded from field planting due to excessive plant height.

Seedlings were produced by germinating 100 seeds per treatment. From these, 50 normal, vigorous plants with 2–4 pairs of true leaves were transplanted into 17 × 23 cm polyethylene bags containing 2.2 kg of soil. Abnormally developed seedlings were discarded. Fertilization and soil acidity correction were applied according to soil test recommendations.

At 24 months after field establishment, plant height (measured from the soil base to the apex) and cumulative yield across three consecutive harvests (2021–2023), expressed as kilograms of cherry coffee plant−1, were recorded. H. vastatrix incidence was evaluated in April and August of 2021, 2022, and 2023 using Scale I of Eskes and Toma-Braghini (1981) [54]. Chemical control was applied only to the susceptible control Caturra.

For the laboratory antibiosis evaluation, mature fruits (200–240 days old) were collected weekly and processed as described by Molina et al. (2022) [42]. Healthy parchment beans (40% moisture) were placed individually in borosilicate vials and infested with a single fertile H. hampei female. Each vial was sealed with a perforated plastic lid (1 mm opening). A total of 2400 experimental units per treatment (80 per plant) were established in a completely randomized design. At 28 days post-infestation, beans were dissected to quantify eggs, larvae, prepupae, pupae, and adults under a stereomicroscope (ZEISS Stemi; Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH, Oberkochen, Germany). A minimum of 29 valid units per treatment was required.

Progenies with plant height equal to or shorter than the commercial controls and yield equal to or greater than the controls were selected. Using H. vastatrix incidence as a selection criterion, progenies with ≥70% of plants scoring ≤ 3 were retained. From the laboratory antibiosis data, mean total developmental stages per bean and percentage reductions relative to controls were calculated.

To validate antibiosis under field conditions, the same progenies were evaluated using the method of Molina et al. (2022) [42]. Fifty healthy fruits (~150 days old) per plant were selected from three randomly chosen branches and enclosed in entomological sleeves, for a total of 150 fruits. The fruits were infested with 100 H. hampei females for 36 h. At 45 days post-infestation, fruits were dissected to quantify all developmental stages; uninfested fruits were discarded.

4.2. Statistical Analysis

For agronomic variables, means and standard errors were estimated, and ANOVA was performed using a 6 × 7 lattice design. The least significant difference (LSD) test at the 5% level was applied to identify progenies with performance equal to or superior to the commercial controls. For H. vastatrix incidence, the maximum score observed per treatment was recorded, and progenies with ≥70% of plants scoring ≤3 were selected.

For laboratory antibiosis, Duncan’s multiple-range test (p ≤ 0.05) was used to compare progenies sharing a common susceptible control. When a progeny had its own control, the LSD test (p ≤ 0.05) was applied. For progenies with significantly reduced developmental stages, the percentage reduction relative to the control was calculated descriptively. For field antibiosis, the same procedures were used.

To evaluate the impact of reduced developmental stages on population dynamics, the simulation model of Montoya et al. (2022) [74] was applied to two contrasting sites: Naranjal (1381 m a.s.l.; 2805 mm rainfall; 20.9 °C mean temperature; 1690 sunshine hours year−1) and Paraguaicito (1203 m a.s.l.; 2169 mm rainfall; 21.7 °C mean temperature; 1671 sunshine hours year−1) [68]. Neutral and El Niño ENSO phases were simulated for each site, and two developmental-stage reduction scenarios were evaluated for each site-ENSO combination.

Initial model inputs included eight infested fruits per tree remaining after harvest; five infested fruits per tree on the ground; two live adults per fruit on the tree; two live adults per fruit on the ground; and an average oviposition rate of three eggs per female per day. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

5. Conclusions

This study achieved substantial advances in the development and evaluation of F3 progenies that combine antibiosis against H. hampei, resistance to H. vastatrix, medium plant stature, and high productivity. Through conventional breeding, the antibiosis trait from Ethiopian C. arabica introductions was successfully introgressed into the commercial Castillo® genetic background. Modeling results further indicate that F3 progenies expressing 34–55% reductions in oviposition may maintain H. hampei infestation below the economic damage threshold throughout the fruit development period, even under El Niño conditions. Progenies exhibiting the highest level of antibiosis (55%) are expected to remain below the action threshold for more than seven months, substantially reducing the need for insecticide applications. These findings underscore the potential of antibiosis-based resistance to provide an effective, sustainable response to the projected impacts of climate change on coffee production.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.M.; Data curation, D.M. and R.M.; Formal analysis, E.C.M., R.M. and P.B.; Funding acquisition, D.M. and C.P.F.-R.; Investigation, D.M.; Methodology, D.M. and P.B.; Project administration, D.M.; Resources, D.M. and C.P.F.-R.; Supervision, D.M.; Validation, D.M. and P.B.; Visualization, D.M.; Writing—original draft, D.M.; Writing—review and editing, D.M., E.C.M., R.M. and P.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Coffee Research Center (Cenicafé) (Crossref Funder ID 100019597).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely appreciate Gilbert Rodriguez, Esteban Quintero, Claudia Tabares, Carlos Augusto Vera, Jairo Jaramillo, and Steven Giraldo for their technical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, the writing of the manuscript, or the decision to publish the results.

References

- World Flora Online (WFO). Coffea L. 2024. Available online: https://www.worldfloraonline.org/taxon/wfo-4000008851 (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- International Coffee Organization (ICO). Coffee Market Report; ICO: London, UK, 2025; Available online: https://www.ico.org/documents/cy2024-25/cmr-0125-e.pdf (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Amrouk, E.M.; Palmeri, F.; Magrini, E. Global Coffee Market and Recent Price Developments. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/handle/20.500.14283/cd4706en (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Poncet, V.; Van Asten, P.; Millet, C.P.; Vaast, P.; Allinne, C. Which Diversification Trajectories Make Coffee Farming More Sustainable? Curr. Opin. Environ. Sust. 2024, 68, 101432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Coffee Organization (ICO). Coffee Development Report 2022–23; ICO: London, UK, 2024; Available online: https://www.ico.org/documents/cy2024-25/annual-review-2023-2024-e.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Davis, A.P.; Govaerts, R.; Bridson, D.M.; Stoffelen, P. An Annotated Taxonomic Conspectus of the Genus Coffea (Rubiaceae). Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2006, 152, 465–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alègre, C. Climates et Caféiers d’Arabie. Agron. Trop. 1959, 14, 23–58. [Google Scholar]

- Federación Nacional de Cafeteros de Colombia. Informe del Gerente General 2024; FNC: Bogota, Colombia, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DaMatta, F.M.; Avila, R.T.; Cardoso, A.A.; Martins, S.C.V.; Ramalho, J.C. Physiological and Agronomic Performance of the Coffee Crop in the Context of Climate Change and Global Warming: A Review. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 5264–5274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, J.I.; Rodrigues, A.P.; Marques, I.; Leitão, A.E.; Pais, I.P.; Semedo, J.N.; Partelli, F.L.; Rakočević, M.; Lidon, F.C.; Ribeiro-Barros, A.I.; et al. Ecophysiological Responses of Coffee Plants to Heat and Drought, Intrinsic Resilience and the Mitigation Effects of Elevated Air [CO2] in a Context of Climate Changes. In Advances in Botanical Research; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; Volume 114, pp. 63–95. ISBN 978-0-443-22294-8. [Google Scholar]

- Ovalle-Rivera, O.; Läderach, P.; Bunn, C.; Obersteiner, M.; Schroth, G. Projected Shifts in Coffea arabica Suitability among Major Global Producing Regions Due to Climate Change. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0124155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magrach, A.; Ghazoul, J. Climate and Pest-Driven Geographic Shifts in Global Coffee Production: Implications for Forest Cover, Biodiversity and Carbon Storage. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0133071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moat, J.; Williams, J.; Baena, S.; Wilkinson, T.; Gole, T.W.; Challa, Z.K.; Demissew, S.; Davis, A.P. Resilience Potential of the Ethiopian Coffee Sector under Climate Change. Nat. Plants 2017, 3, 17081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grüter, R.; Trachsel, T.; Laube, P.; Jaisli, I. Expected Global Suitability of Coffee, Cashew and Avocado Due to Climate Change. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0261976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.L.; Von Dos Santos Veloso, R.; De Oliveira, G.S.; Queiroz, R.B.; Araújo, F.H.V.; De Andrade, A.M.; Da Silva, R.S. Effects of the Climate Change Scenario on Coffea Canephora Production in Brazil Using Modeling Tools. Trop. Ecol. 2024, 65, 559–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorençone, J.A.; De Oliveira Aparecido, L.E.; Lorençone, P.A.; Torsoni, G.B.; De Lima, R.F.; Da Silva Cabral De Moraes, J.R.; De Souza Rolim, G. Agricultural Zoning of Coffea arabica in Brazil for Current and Future Climate Scenarios: Implications for the Coffee Industry. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 27, 4143–4166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, P.D.S.; Giarolla, A.; Chou, S.C.; Silva, A.J.D.P.; Lyra, A.D.A. Climate Change Impact on the Potential Yield of Arabica Coffee in Southeast Brazil. Reg. Environ. Change 2018, 18, 873–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, C.G.; Martins, F.B.; Martins, M.A. Climate Risks and Vulnerabilities of the Arabica Coffee in Brazil under Current and Future Climates Considering New CMIP6 Models. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 907, 167753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo, J.; Chabi-Olaye, A.; Kamonjo, C.; Jaramillo, A.; Vega, F.E.; Poehling, H.-M.; Borgemeister, C. Thermal Tolerance of the Coffee Berry Borer Hypothenemus hampei: Predictions of Climate Change Impact on a Tropical Insect Pest. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e6487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaramillo, J.; Muchugu, E.; Vega, F.E.; Davis, A.; Borgemeister, C.; Chabi-Olaye, A. Some Like It Hot: The Influence and Implications of Climate Change on Coffee Berry Borer (Hypothenemus hampei) and Coffee Production in East Africa. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e24528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina, D. Revisión Sobre La Broca Del Café, Hypothenemus hampei (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae) Con Énfasis En La Resistencia Mediante Antibiosis y Antixenosis. Rev. Colomb. Entomol. 2022, 48, 11172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, P.S. Some Aspects of the Behavior of the Coffee Berry Borer in Relation to Its Control in Southern Mexico. Folia Entomol. Mex. 1984, 61, 9–24. [Google Scholar]

- Le Pelley, R.H. Collembola and Coleoptera. In Pests of Coffee; Le Pelley, R.H., Ed.; Longmans: Harlow, UK, 1968; pp. 99–178. [Google Scholar]

- Montoya, E.C. Caracterización de La Infestación de Café Por La Broca y Efecto Del Daño En La Calidad de La Bebida. Rev. Cenicafé 1999, 50, 245–258. [Google Scholar]

- Alves Da Silva, S.; Fonseca Alvarenga Pereira, R.G.; De Azevedo Lira, N.; Micotti Da Glória, E.; Chalfoun, S.M.; Batista, L.R. Fungi Associated to Beans Infested with Coffee Berry Borer and the Risk of Ochratoxin A. Food Control 2020, 113, 107204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puerta, G.I. Buenas Prácticas Para La Prevención de Los Defectos de La Calidad Del Café: Fermento, Reposado, Fenólico y Mohoso. Avan. Tec. Cenicafé 2015, 461, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, S.A.; Pereira, R.G.F.A.; Chalfoun, S.M.; Teixeira, A.R. Physical and Chemical Attributes of Beans Damaged by the Coffee Berry Borer at Different Levels of Infestation. Bragantia 2024, 83, e20230251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergamin, J. Contribuição Para o Conhecimento Da Biologia Da Broca Do Café Hypothenemus hampei (Ferrari, 1867) (Coleoptera: Ipidae). Arq. Inst. Biol. 1943, 14, 31–72. [Google Scholar]

- Romero, J.V.; Cortina, H.A. Fecundidad y Ciclo de Vida de Hypothenemus hampei Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae En Introducciones Silvestres de Café. Rev. Cenicafé 2004, 55, 221–231. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Cárdenas, R.; Baker, P. Life Table of Hypothenemus hampei (Ferrari) in Relation to Coffee Berry Phenology under Colombian Field Conditions. Sci. Agric. 2010, 67, 658–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benavides, P.; Gongora, C.; Bustillo, A. IPM Program to Control Coffee Berry Borer Hypothenemus hampei, with Emphasis on Highly Pathogenic Mixed Strains of Beauveria Bassiana, to Overcome Insecticide Resistance in Colombia. In Insecticides—Advances in Integrated Pest Management; Perveen, F., Ed.; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2012; ISBN 978-953-307-780-2. [Google Scholar]

- Thirumalai, K.; DiNezio, P.N.; Partin, J.W.; Liu, D.; Costa, K.; Jacobel, A. Future Increase in Extreme El Niño Supported by Past Glacial Changes. Nature 2024, 634, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo-Robledo, Á.; Arcila-Pulgarín, J. Variabilidad climática en la zona cafetera colombiana asociada al evento de El Niño y su efecto en la caficultura. Avan. Tec. Cenicafé 2009, 390, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, L.J.; Hollingsworth, R.G.; Sabado-Halpern, M.; Manoukis, N.C.; Follett, P.A.; Johnson, M.A. Coffee Berry Borer (Hypothenemus hampei) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) Development across an Elevational Gradient on Hawai‘i Island: Applying Laboratory Degree-Day Predictions to Natural Field Populations. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0218321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Constantino, L.M.; Gil, Z.N.; Montoya, E.C.; Benavides, P. Coffee Berry Borer (Hypothenemus hampei) Emergence from Ground Fruits Across Varying Altitudes and Climate Cycles, and the Effect on Coffee Tree Infestation. Neotrop. Entomol. 2021, 50, 374–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Painter, R.H. Insect Resistance in Crop Plants. Soil Sci. 1951, 72, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogan, M.; Ortman, E.F. Antixenosis-A New Term Proposed to Define Painter’s “Nonpreference” Modality of Resistance. Bull. Entomol. Soc. Am. 1978, 24, 175–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karjagi, C.G.; Sekhar, J.C.; Lakshmi, S.P.; Suby, S.B.; Kaur, J.; Mallikarjuna, M.G.; Kumar, P. Breeding for Resistance to Insect Pests in Maize. In Breeding Insect Resistant Crops for Sustainable Agriculture; Arora, R., Sandhu, S., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 201–229. ISBN 978-981-10-6055-7. [Google Scholar]

- Danso Ofori, A.; Su, W.; Zheng, T.; Datsomor, O.; Titriku, J.K.; Xiang, X.; Kandhro, A.G.; Ahmed, M.I.; Mawuli, E.W.; Awuah, R.T.; et al. Jasmonic Acid (JA) Signaling Pathway in Rice Defense Against Chilo Suppressalis Infestation. Rice 2025, 18, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.-J.; Liu, Y.; Ma, Y.-S.; Wang, Y.-L.; Wang, X.-Y.; Ma, Y.; Xie, L.-L. Insect Resistance Responses of Ten Aster Varieties to Damage by Tephritis Angustipennis in the Three Rivers Source Region of China. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 6962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.M. Conventional Breeding of Insect-Resistant Crop Plants: Still the Best Way to Feed the World Population. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2021, 45, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, D.; Moncada-Botero, M.-P.; Cortina-Guerrero, H.A.; Benavides, P. Searching for a Coffee Variety with Antibiosis Effect to Hypothenemus hampei Ferrari (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Euphytica 2022, 218, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, J.V.; Bustamante, L.J.; Cortina, H.A.; Moncada, M.D.P. Evaluación por resistencia a Hypothenemus hampei Ferrari en poblaciones derivadas de cruces entre Caturra e introducciones etíopes. Rev. Cenicafé 2012, 2, 31–49. [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva, R.S.; Soares, J.R.S.; Barbosa Dos Santos, I.; Pimentel, M.F.; Farias, E.D.S.; Martins, J.C.; Zambolim, L.; Picanço, M.C. Evaluation of the Resistance of Coffea canephora to Oligonychus ilicis (Acari: Tetranychidae) and the Preimaginal Conditioning Effect on Resistance Using a Biological Life Table. Int. J. Pest Manag. 2019, 65, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, D.C.M.; Souza, B.H.S.; Carvalho, C.H.S.; Guerreiro Filho, O. Characterization and Levels of Resistance in Coffea arabica × Coffea racemosa Hybrids to Leucoptera coffeella. J. Pest. Sci. 2025, 98, 1075–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardenas, M.R.; Bustillo, A.E. La Broca Del Café En Colombia. In Proceedings of the I Reunión Intercontinental sobre Broca del Café, Tapachula, México, 17–22 November 1991; pp. 42–44. [Google Scholar]

- Romero, J.V.; Cortina-G., H.A. Tablas de Vida de Hypothenemus hampei (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae) Sobre Tres Introducciones de Café. Rev. Colomb. Entomol. 2007, 33, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagnon, C.; Bouharmont, P. Multivariate Analysis of Phenotypic Diversity of Coffea arabica. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 1996, 43, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, F.; Bertrand, B.; Quiros, O.; Wilches, A.; Lashermes, P.; Berthaud, J.; Charrier, A. Genetic Diversity of Wild Coffee (Coffea arabica L.) Using Molecular Markers. Euphytica 2001, 118, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, F.G. Notes on Wild Coffea arabica from Southwestern Ethiopia, with Some Historical Considerations. Econ. Bot. 1965, 19, 136–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskes, A.B. Incomplete Resistance to Coffee Leaf Rust (Hemileia vastatrix). Ph.D. Thesis, Landbouwhogeschool Wageningen, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Anzueto, F.; Bertrand, B.; Sarah, J.L.; Eskes, A.B.; Decazy, B. Resistance to Meloidogyne Incognita in Ethiopian Coffea arabica Accessions. Euphytica 2001, 118, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, D.; Medina Rivera, R. Identifying Coffea Genotypes Tolerant to Water Deficit. Coffee Sci. 2022, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, S.R.; Turcotte, M.M.; Poveda, K. Domestication Impacts on Plant–Herbivore Interactions: A Meta-Analysis. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 2017, 372, 20160034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskes, A.B.; Toma-Braghini, M. Métodos de Evaluación de La Resistencia Contra La Roya Del Cafeto (Hemileia vastatrix Berk. et Br.). Boletín Fitosanit. FAO 1981, 29, 56–66. [Google Scholar]

- Azrag, A.G.A.; Babin, R. Integrating Temperature-Dependent Development and Reproduction Models for Predicting Population Growth of the Coffee Berry Borer, Hypothenemus hampei Ferrari. Bull. Entomol. Res. 2023, 113, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina, D.; Patiño, L.; Quintero, M.; Cortes, J.; Bastos, S. Effects of the Aspartic Protease Inhibitor from Lupinus bogotensis Seeds on the Growth and Development of Hypothenemus hampei: An Inhibitor Showing High Homology with Storage Proteins. Phytochemistry 2014, 98, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, P.K.; Singh, D.; Singh, R.; Sinha, M.K.; Singh, S.; Jamal, F. Cassia Fistula Seed’s Trypsin Inhibitor(s) as Antibiosis Agent in Helicoverpa Armigera Pest Management. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2016, 6, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Shi, Y.; Lin, X.; Li, Z.; Xiao, J.; Yang, X. Effects of Wild, Local, and Cultivated Tobacco Varieties on the Performance of Spodoptera Litura and Its Parasitoid Meteorus pulchricornis. Pest Manag. Sci. 2023, 79, 2390–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, A.F.; De Rezende Abrahão, J.C.; Andrade, V.T.; Bauti, V.M.; Dos Santos, C.S.; De Oliveira, A.C.B.; Pereira, A.A.; De Oliveira, A.L.; De Oliveira, I.P.; Carvalho, G.R.; et al. Egg-Induced Resistance and Morphological Mechanisms in Coffea arabica × Coffea racemosa Progenies Affecting Leucoptera coffeella. Euphytica 2025, 221, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno Ruiz, G.; Castillo Zapata, J. La Variedad Colombia; Una Variedad de Café Con Resistencia a La Roya/Hemileia vastatrix/Berk y Br. Bol. Téc. Cenicafé. 1984, 9, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado-Alvarado, G.; Posada-Suárez, H.E.; Cortina, H.A. Castillo: Nueva Variedad de Café Con Resistencia a La Roya. Avan. Tec. Cenicafé 2005, 337, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, H.A.; Acuña Zornosa, J.R.; Moncada, M.d.P.; Herrera, J.C.; Molina, D. Variedades de Café: Desarrollo de Variedades. In Manual del Cafetero Colombiano: Investigación y Tecnología para la Sostenibilidad de la Caficultura; Federación Nacional de Cafeteros de Colombia, Ed.; Cenicafé: Chinchiná, Colombia, 2013; Volume 1, pp. 169–202. [Google Scholar]

- Berny Mier Y Teran, J.C.; Pruvot-Woehl, S.; Maina, C.; Barrera, S.; Gimase, J.M.; Banda, B.; Meza, A.; Kachiguma, N.A.; Gichuru, E.K.; Alvarado, J.; et al. Global Coffea arabica Variety Trials Reveal Genotype-by-Environment Interactions in Resistance to Coffee Leaf Rust (Hemileia vastatrix). Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1583595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, M.R.; Arcila, A.; Riaño, N.; Bustillo, A.E. Crecimiento y Desarrollo Del Fruto de Café y Su Relación Con La Broca. Avan. Tec. Cenicafé 1993, 194, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Saldarriaga, G. Evaluación de Prácticas Culturales En El Control de La Broca Del Café Hypothenemus hampei (Ferrari 1867) (Coleoptera: Scolytidae). Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogota, Colombia, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Duque, H.; Baker, P.S. Devouring Profit the Socio-Economics of Coffee Berry Borer IPM; Cenicafé: Chinchiná, Colombia, 2003; ISBN 978-958-97218-4-1. [Google Scholar]

- Jaramillo-Robledo, A. El Clima de la Caficultura en Colombia; Cenicafé: Chinchiná, Colombia, 2018; ISBN 978-958-8490-21-2. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, R. Efecto de La Fenología Del Fruto Del Café Sobre Los Parámetros de La Tabla de Vida de La Broca Del Café Hypothenemus hampei (Ferrari). Universidad de Caldas, Caldas, Colombia, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Arcila, J.; Jaramillo, A. Relación Entre La Humedad Del Suelo, La Floración y El Desarrollo Del Fruto Del Cafeto. Avan. Tec. Cenicafé 2003, 311, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Arcila, J.; Jaramillo, A.; Baldion, J.V.; Bustillo, A.E. La Floración Del Cafeto y Su Relación Con El Control de La Broca. Avan. Tec. Cenicafé 1993, 193, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker, L.; Gonzalez-Moreno, P.; Lowry, A.; Velez, L.J.; Aristizabal, V.; Aristizabal, L.F.P.; Edgington, S.; Murphy, S. The effect of an altitudinal gradient on the abundance and phenology of the coffee berry borer (Hypothenemus hampei) (Ferrari) (Coleoptera: Scolytidae) in the Colombia Andes. Int. J. Pest Mang. 2024, 70, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ángel, C.C.A.; Marín-Ramírez, G.A.; Maldonado, C.E. Genome Sequence of Hemileia vastatrix Berk. and Br. (Race I), the Causal Agent of Coffee Leaf Rust, Isolate from Risaralda, Colombia. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2023, 12, e00444-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montoya, E.C.; Benavides Machado, P.; Arcila-Pulgarin, J.; Jaramillo-Robledo, A.; Quiroga, F. Modelo de Simulación Para El Comportamiento de La Infestación Por Broca En El Cultivo de Café. Bol. Téc. Cenicafé. 2022, 47, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).