Expression Profiling of the Aluminum-Activated Malate Transporter (ALMT) Gene Family in Pumpkin in Response to Aluminum Stress and Exogenous Polyamines

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

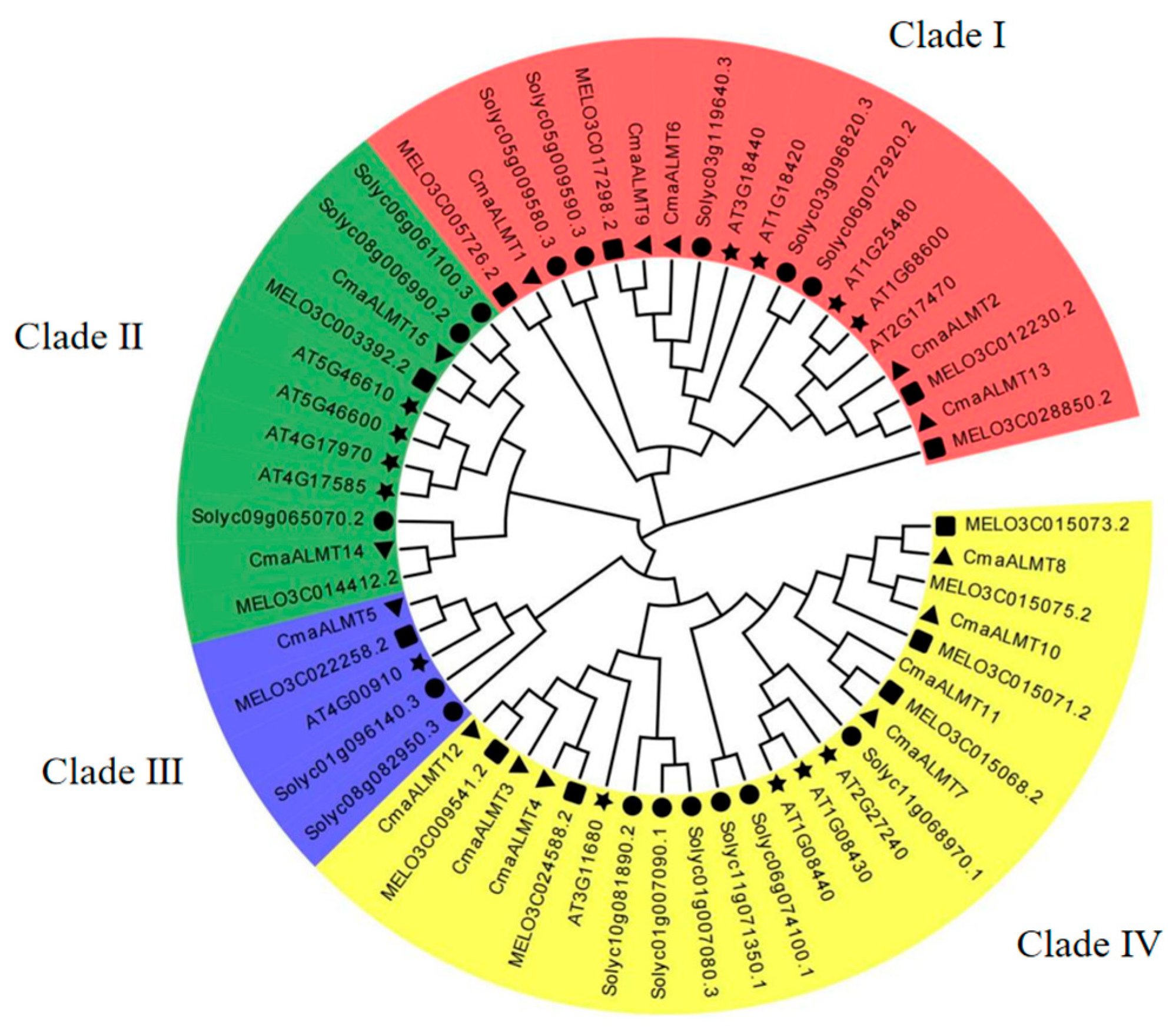

2.1. Identification of the Pumpkin ALMT Gene Family

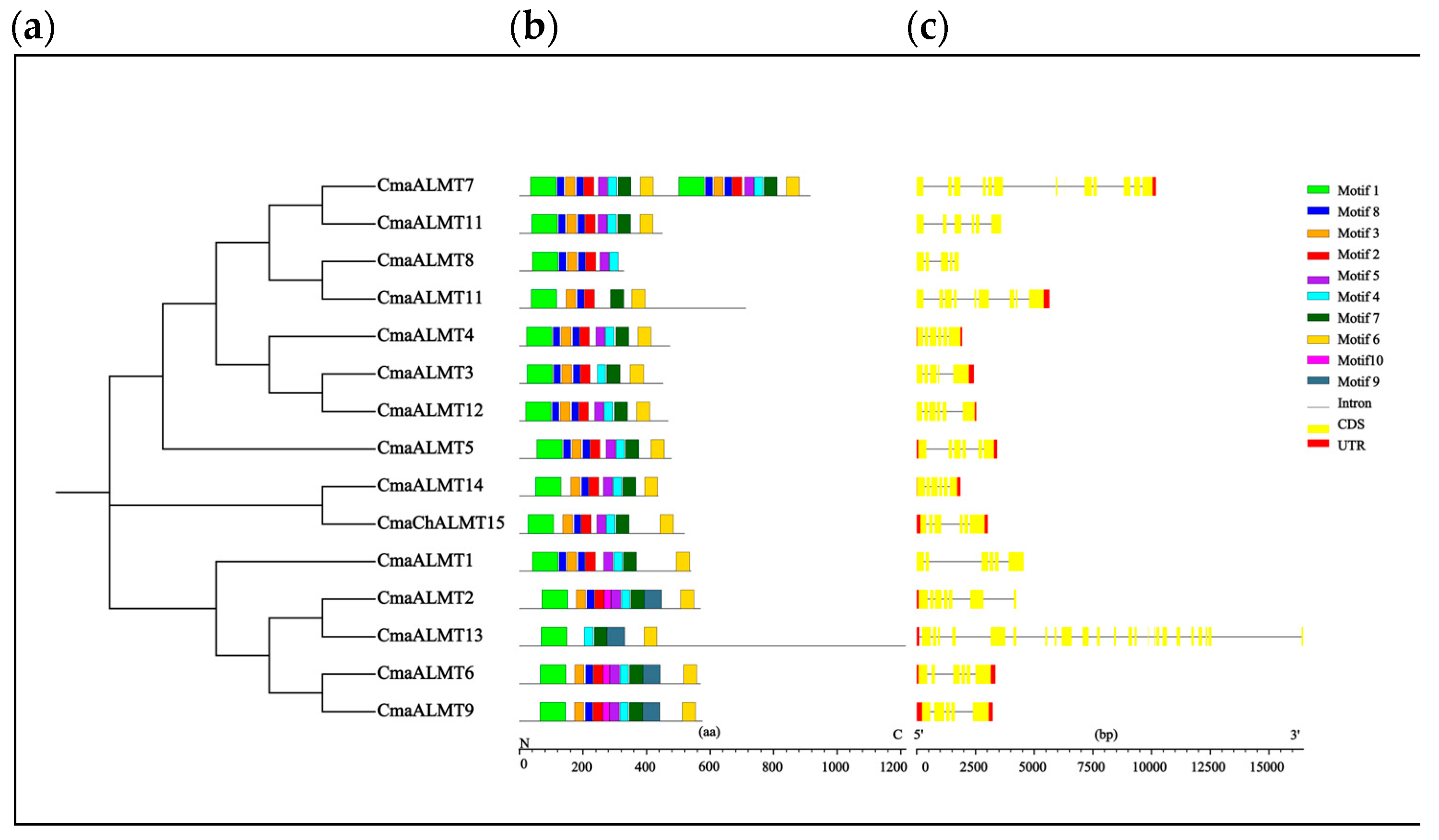

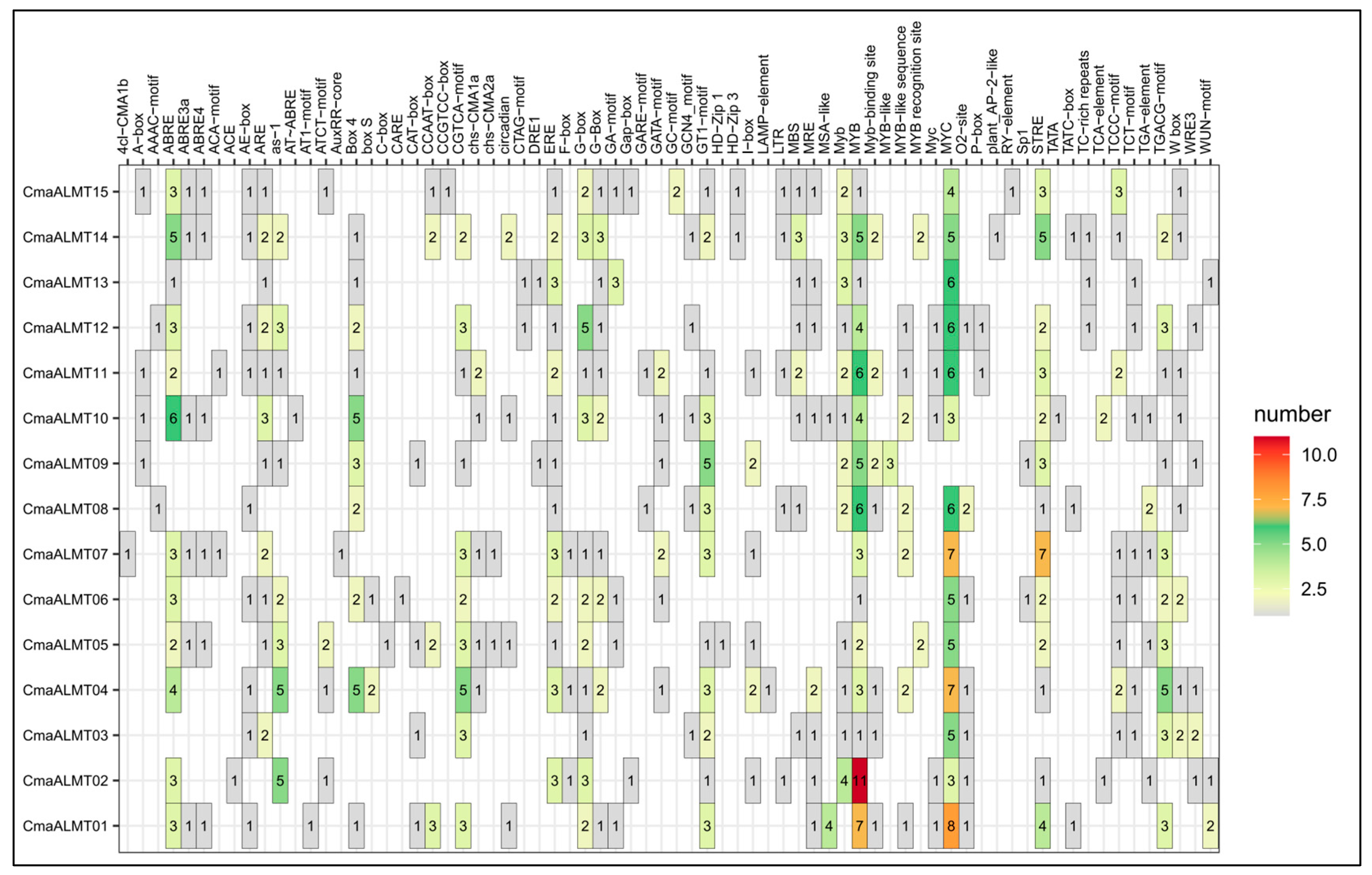

2.2. Gene Structure and Promoter Analysis

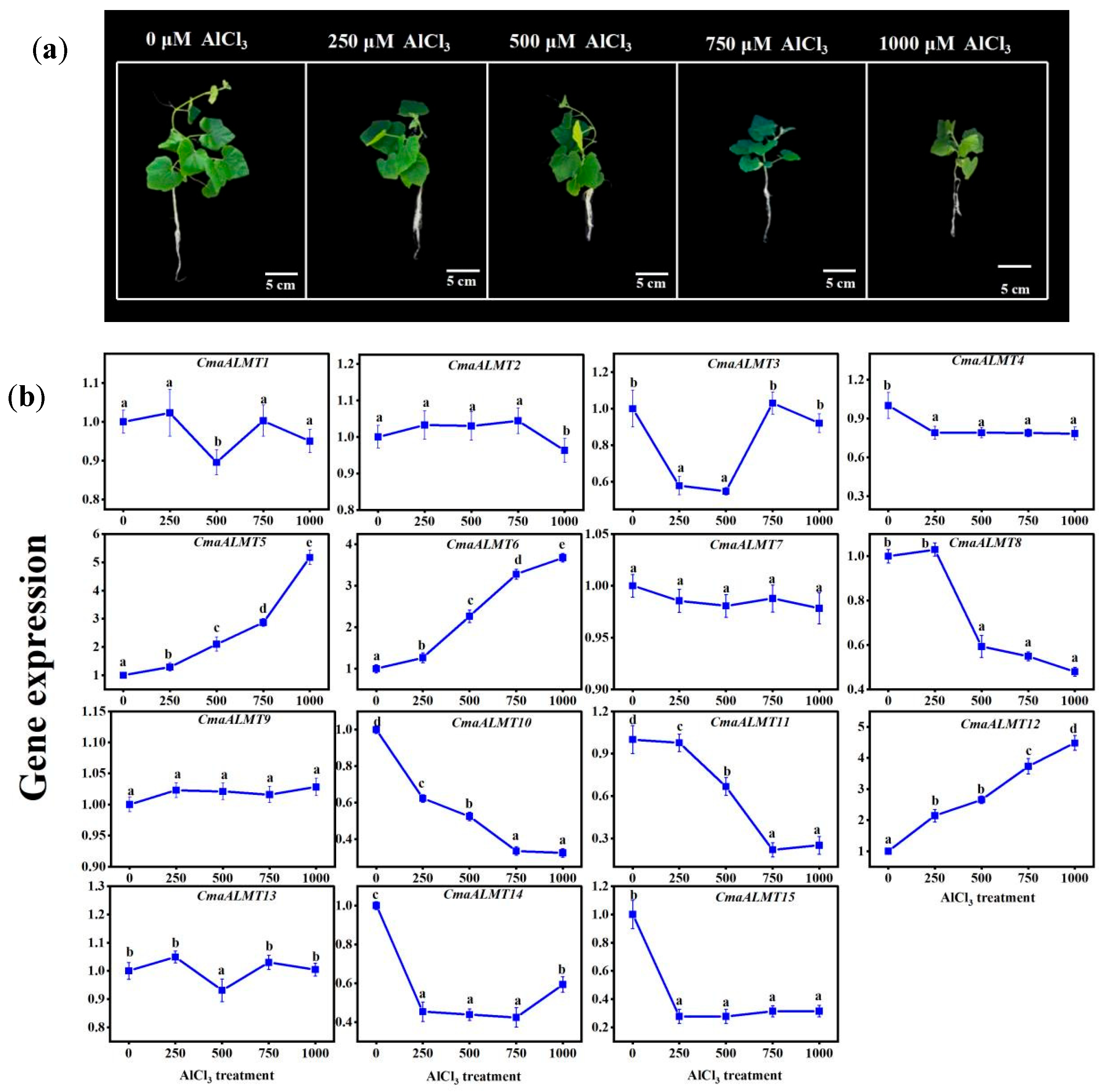

2.3. Expression Analysis of ALMT Genes Under Al Stress

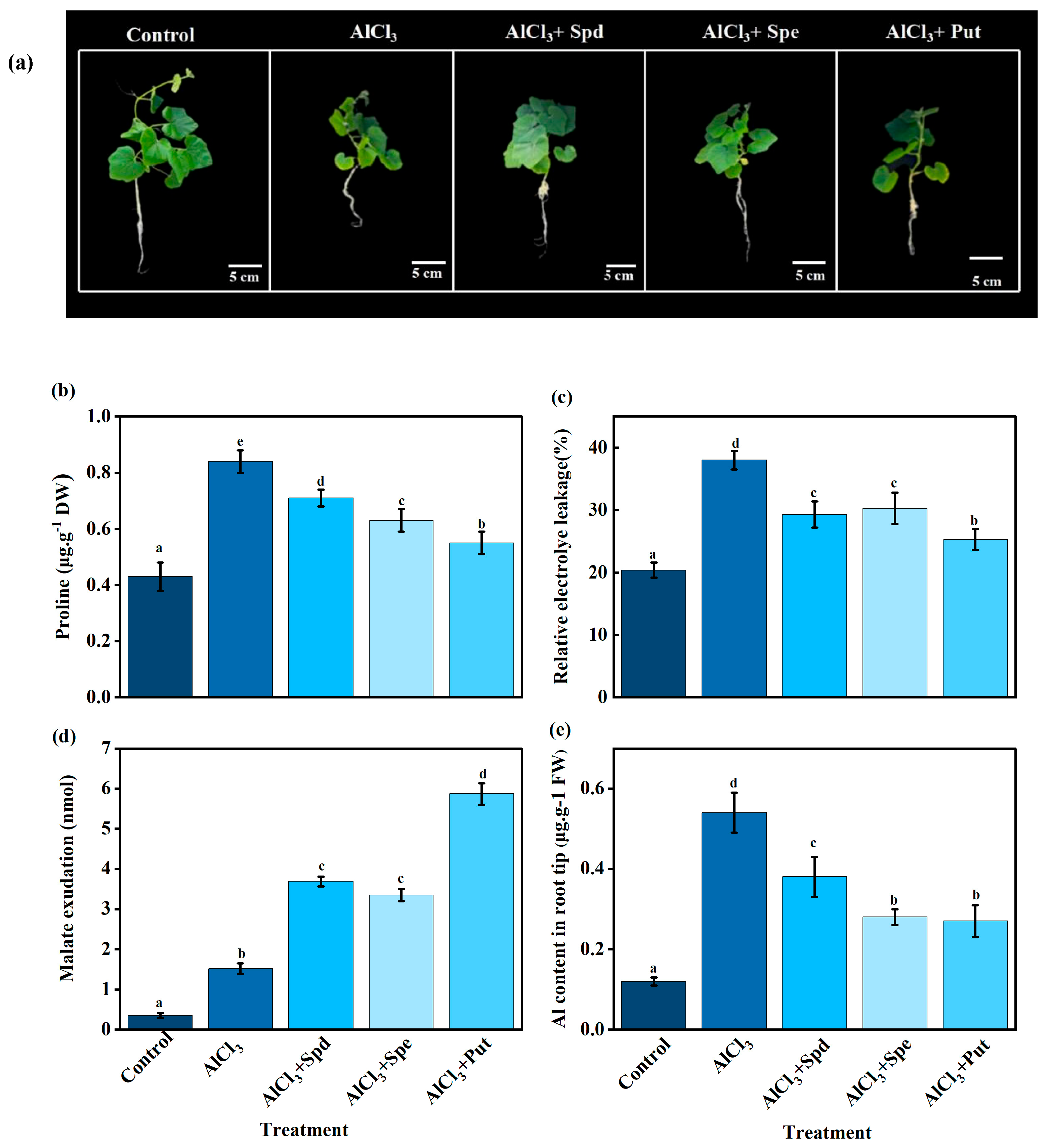

2.4. Effects of Exogenous Polyamines on Root Phenotype and Malate Content in Pumpkin Seedlings Under Aluminum Stress

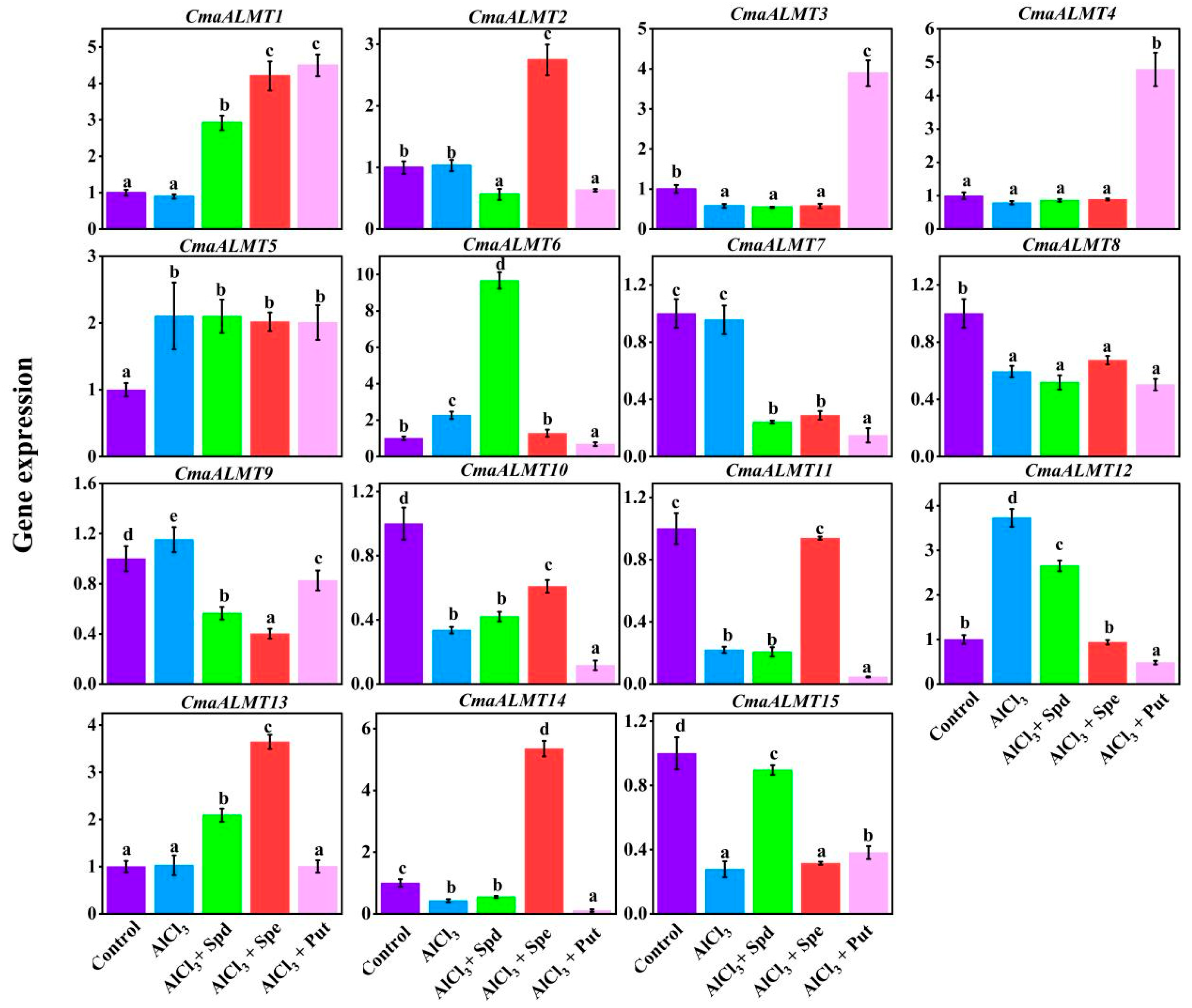

2.5. Expression Analysis of ALMT Gene Family Members Under Aluminum Stress with Exogenous Polyamines

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials and Stress Treatments

4.2. Bioinformatic Analysis of the Pumpkin ALMT Gene Family Members

4.3. RNA Extraction and Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR) Analysis

4.4. Determination of Relative Electrolyte Leakage, Proline, Malate Content and Al Content

4.5. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kang, Y.C.; Zhu, S.D.; Li, G.Y.; Jiang, Y.B.; Teng, W.C.; Luo, M.; Wei, J.; Cao, F.; Wang, Z.; Huang, J. Phosphorus applied to the root half without Al3+ exposure can alleviate Al toxicity on the other root half of the same eucalyptus seedling. J. Plant Nutr. 2020, 44, 829–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Barros, I.R.; Benincá, C.; Zanoelo, E.F. Kinetics of the precipitation reaction between aluminium and contaminant orthophosphate ions. Environ. Technol. 2023, 45, 4266–4283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, A.; Sinha, R.; Sharma, T.R.; Pattanayak, A.; Singh, A.K. Alleviating aluminum toxicity in plants: Implications of reactive oxygen species signaling and crosstalk with other signaling pathways. Physiol. Plant 2021, 173, 1765–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosa, K.A.; Ramamoorthy, K.; Elnaggar, A.; Kumar, K.; Sultan, R.A.; Sabbagh, S.M.; Alnaqbi, S.M.; Kamal, S.Y. Aluminum induced physiochemical alterations, genotoxic effects, and gene expression changes in hydroponically grown cucumber (Cucumis sativus). Hortic. Environ. Biotechnol. 2025, 66, 967–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assefa, A.; Bezabih, A.; Girmay, G.; Alemayehu, T.; Lakew, A. Evaluation of sorghum (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench) variety performance in the lowlands area of wag lasta, north eastern Ethiopia. Cogent Food Agric. 2020, 6, 1778603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, K.X.; Yang, Z.M.; Zhan, M.Q.; Zheng, M.H.; You, J.F.; Meng, X.X.; Li, H.; Gao, J. Two sweet sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L.) WRKY transcription factors promote aluminum tolerance via the reduction in callose deposition. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phukunkamkaew, S.; Tisarum, R.; Pipatsitee, P.; Samphumphuang, T.; Maksup, S.; Cha-um, S. Morpho-physiological responses of indica rice (Oryza sativa sub. indica) to aluminum toxicity at seedling stage. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 29321–29331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.H.; Kao, C.H. Morphological and cellular changes in rice roots (Oryza sativa L.) caused by Al stress. Bot. Bull. Acad. Sin. 2012, 53, 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, S.; Hou, X.; Liang, X. ResPonse mechanisms of Plants under saline-alkali stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 667458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riaz, M. Aluminum Toxicity in Plants: Mechanisms of Aluminum Toxicity and Tolerance. In Beneficial Elements for Remediation of Heavy Metals in Polluted Soil; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; pp. 33–54. [Google Scholar]

- Kocjan, A.; Kwasniewska, J.; Szurman-Zubrzycka, M. Understanding Plant tolerance to aluminum: ExPloring mechanisms and PersPectives. Plant Soil 2025, 507, 195–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrahari, R.K.; Enomoto, T.; Ito, H.; Nakano, Y.; Yanase, E.; Watanabe, T.; Sadhukhan, A.; Iuchi, S.; Kobayashi, M.; Panda, S.K.; et al. Expression GWAS of PGIP1 identifies STOP1-dependent and STOP1-independent regulation of PGIP1 in aluminum stress signaling in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 774687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tripathi, A.; Singh, D.; Bhati, J.; Singh, D.; Taunk, J.; Alkahtani, J.; Al-Hashimi, A.; Singh, M.P. Genome wide identification of MATE and ALMT gene family in lentil (Lens culinaris Medikus) and expression profiling under Al stress condition. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, C.; Piñeros, M.A.; Tian, J.; Yao, Z.F.; Sun, L.L.; Liu, J.P.; Shaff, J.; Coluccio, A.; Kochian, L.V.; Liao, H. Low pH, aluminum, and phosphorus coordinately regulate malate exudation through GmALMT1 to improve soybean adaptation to acid soils. Plant Physiol. 2013, 161, 1347–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, T.; Yamamoto, Y.; Ezaki, B.; Katsuhara, M.; Ahn, S.J.; Ryan, P.R.; Delhaize, E.; Matsumoto, H. A wheat gene encoding an aluminum-activated malate transporter. Plant J. 2004, 37, 645–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligaba, A.; Katsuhara, M.; Ryan, P.R.; Shibasaka, M.; Matsumoto, H. The BnALMT1 and BnALMT2 genes from rape encode aluminum-activated malate transporters that enhance the aluminum resistance of plant cells. Plant Physiol. 2006, 142, 1294–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoekenga, O.A.; Maron, L.G.; Pineros, M.A.; Cancado, G.M.A.; Shaff, J.; Kobayashi, Y.; Ryan, P.R.; Dong, B.; Delhaize, E.; Sasaki, T.; et al. AtALMT1, which encodes a malate transporter, is identified as one of several genes critical for aluminum tolerance in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 9738–9743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Jiang, S.X.; Li, Q.; Song, Z.Y.; Yang, Y.; Yu, S.R.; Nie, Z.Y.; Chu, M.L.; An, Y.L. Identification of the ALMT gene family in the potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) and analysis of the function of StALMT6/10 in response to aluminum toxicity. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1274260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Wu, W.W.; Peng, J.C.; Li, J.J.; Lin, Y.; Wang, Y.N.; Tian, J.; Sun, L.L.; Liang, C.Y.; Liao, H. Characterization of the soybean GmALMT family genes and the function of GmALMT5 in response to phosphate starvation. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2018, 60, 216–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.P.; Vinecky, F.; Duarte, K.E.; Santiago, T.R.; Casari1, R.A.C.N.; Hell, A.F.; Cunha, B.A.D.B.; Martins, P.K.; Centeno, D.C.C.; Molinari, P.A.O.M.; et al. Enhanced aluminum tolerance in sugarcane: Evaluation of SbMATE over-expression and genome-wide identification of ALMTs in Saccharum spp. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Xin, Q.; Ming, Y.Z.; Shao, Z. Genome-Wide analysis of aluminum-activated malate transporter family genes in six rosaceae species, and expression analysis and functional characterization on malate accumulation in Chinese white pear. Plant Sci. 2018, 274, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Yuan, Y.Y.; Gao, M.; Xing, L.B.; Li, C.Y.; Li, M.J.; Ma, F.W. Genome-wide identification, molecular evolution, and expression divergence of aluminum-activated malate transporters in apples. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blázquez, M.A. Polyamines: Their role in plant development and stress. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2024, 75, 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Qu, J.; Fang, Y.; Yang, H.; Lai, W.; Pan, L.; Liu, J.H. Polyamines: The valuable bio-stimulants and endogenous signaling molecules for plant development and stress response. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2025, 67, 582–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, R.K.; Shao, J.; Mattoo, A.K. Genomic analysis of the polyamine biosynthesis pathway in duckweed Spirodela polyrhiza L.: Presence of the arginine decarboxylase pathway, absence of the ornithine decarboxylase pathway, and response to abiotic stresses. Planta 2021, 254, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.S.; Dennis, C.; Naqvi, I.; Dailey, L.; Lorzadeh, A.; Ye, G.; Zaytouni, T.; Adler, A.; Hitchcock, D.S.; Lin, L.; et al. Ornithine aminotransferase supports polyamine synthesis in pancreatic cancer. Nature 2023, 616, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichugovskiy, A.; Tron, G.C.; Maslov, M. Recent advances in the synthesis of polyamine derivatives and their applications. Molecules 2021, 26, 6579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schibalski, R.S.; Shulha, A.S.; Tsao, B.P.; Palygin, O.; IIatovskaya, D.V. The role of polyamine metabolism in cellular function and physiology. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2024, 327, C341–C356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pál, M.; Szalai, G.; Gondor, O.K.; Janda, T. Unfinished story of polyamines: Role of conjugation, transport and light-related regulation in the polyamine metabolism in plants. Plant Sci. 2021, 308, 110923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tofiq, A.; Ahmad, H.K.; Khoshnoodi, A. The role of polyamines in plants: A review. J. Plant Sci. Technol. 2023, 5, 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Spormann, S.; Soares, C.; Teixeira, J.; Fidalgo, F. Polyamines as key regulatory players in plants under metal stress—A way for an enhanced tolerance. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2020, 178, 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.J.; Liu, X.P.; Gao, K.K.; Cui, M.Q.; Zhu, H.H.; Li, G.X.; Yan, J.Y.; Wu, Y.R.; Ding, Z.J.; Chen, X.W.; et al. ART1 and putrescine contribute to rice aluminum resistance via OsMYB30 in cell wall modification. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2023, 65, 934–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, P.; Yadav, A.; Borah, S.P.; Moulick, D.; Choudhury, S. Exogenously applied putrescine regulates aluminium [al (III)] stress in maize (Zea mays L.): Physiological and metabolic implications. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2024, 60, 103277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, H.A.A.; Alshammari, S.O.; Abd El-Sadek, M.E.; Kenawy, S.K.M.; Badawy, A.A. The promotive effect of putrescine on growth, biochemical constituents, and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) plants under water stress. Agriculture 2023, 13, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkő, P.; Gémes, K.; Fehér, A. Polyamine oxidase-generated reactive oxygen species in plant development and adaptation: The polyamine oxidase—NADPH oxidase nexus. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Wang, P.; Li, S.; Liu, T.; Hu, X. Polyamine oxidase triggers H2O2-mediated spermidine improved oxidative stress tolerance of tomato seedlings subjected to saline-alkaline stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pattyn, J.; Vaughan-Hirsch, J.; Van de Poel, B. The regulation of ethylene biosynthesis: A complex multilevel control circuitry. New Phytol. 2021, 229, 770–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, H.F.; Wu, X.L.; Yang, X.Q.; Sun, M.X.; Liang, J.H.; Xiao, Y.S.; Peng, F.T. Silicon inhibits gummosis by promoting polyamine synthesis and repressing ethylene biosynthesis in peach. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 986688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.B.; Chen, B.X.; Kurtenbach, R. Spermidine and spermine converted from putrescine improve the resistance of wheat seedlings to osmotic stress. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2023, 70, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.P.; Gao, L.J.; She, B.T.; Li, G.X.; Wu, Y.R.; Xu, J.M.; Ding, Z.J.; Ma, J.F.; Zheng, S.J. A novel kinase subverts aluminium resistance by boosting ornithine decarboxylase-dependent putrescine biosynthesis. Plant Cell Environ. 2022, 45, 2520–2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.J.; Gong, Z.M.; Chen, X.; Wang, H.J.; Tan, R.R.; Mao, Y.X. Transcriptomic responses to aluminum stress in tea plant leaves. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 5800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, P.; Glasheen, B.M.; Bains, S.K.; Long, S.L.; Minocha, R.; Walter, C.; Minocha, S.C. Transgenic manipulation of the metabolism of polyamines in poplar cells. Plant Physiol. 2001, 125, 2139–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, N.H.; Kim, B.S.; Hwang, B.K. Pepper arginine decarboxylase is required for polyamine and γ-aminobutyricacid signaling in cell death and defense response. Plant Physiol. 2013, 162, 2067–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, S.A.; Tverman, S.D.; Xu, B.; Bose, J.; Kaur1, S.; Conn1, V.; Domingos, P.; Ullah, S.; Wege, S.; Shabala, S.; et al. GABA signalling modulates plant growth by directly regulating the activity of plant-specific anion transporters. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Liu, B.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Cai, J.; Cui, J. Integrative multi-omics analysis of chilling stress in pumpkin (Cucurbita moschata). BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.S.; Wang, L.; Nawaz, M.A.; Niu, M.L.; Sun, J.Y.; Xie, J.J.; Kong, Q.S.; Huang, Y.; Cheng, F.; Bie, Z.L. Ectopic expression of Pumpkin NAC transcription factor CmNAC1 improves multiple abiotic stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, N.; Das, A.; Pal, S.; Roy, S.; Sil, S.K.; Adak, M.K.; Hassanzamman, M. Exploring Aluminum Tolerance Mechanisms in Plants with Reference to Rice and Arabidopsis: A Comprehensive Review of Genetic, Metabolic, and Physiological Adaptations in Acidic Soils. Plants 2024, 13, 1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; Kulik, E.; Majláth, I.; Khan, I.; Janda, T.; Pál, M. Different reactions of wheat, maize, and rice plants to putrescine treatment. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2024, 213, 114757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.Q.; Yu, X.F.; Ding, Z.J.; Zhang, X.K.; Yuan, T.; Zheng, S.J.; Yang, W.; Luo, Y.P.; Xu, X.M.; Xie, Y.; et al. Structural basis of ALMT1-mediated aluminum resistance in Arabidopsis. Cell Res. 2022, 32, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, T.; Ariyoshi, M.; Yamamoto, Y.; Mori, I.C. Functional roles of ALMT-type anion channels in malate-induced stomatal closure in tomato and Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Environ. 2022, 45, 2337–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dreyer, I.; Gomez-Porras, J.L.; Riaño-Pachón, D.M.; Hedrich, R.; Geiger, D. Molecular evolution of slow and quick anion channels (SLACs and QUACs/ALMTs). Front. Plant Sci. 2012, 3, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, S.; Mumm, P.; Imes, D.; Endler, A.; Weder, B.; Al-Rasheid, K.A.S.; Geiger, D.; Marten, I.; Martinoia, E.; Hedrich, R. AtALMT12 represents an R-type anion channel required for stomatal movement in Arabidopsis guard cells. Plant J. 2010, 63, 1054–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, D.K.; Yadav, V.; Vaculík, M.; Gassmann, W.; Pike, S.; Arif, N.; Singh, V.P.; Deshmukh, R.; Sahi, S.; Tripathi, D.K. Aluminum toxicity and aluminum stress-induced physiological tolerance responses in higher plants. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2021, 41, 715–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, A.; Chakraborty, M.; Saha, J.; Gupta, B.; Gupta, K. Polyamines: Osmoprotectants in plant abiotic stress adaptation. In Osmolytes and Plants Acclimation to Changing Environment: Emerging Omics Technologies; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 97–127. [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan, B.; Patra, S.; Dash, S.R.; Maharana, S.; Behera, C.; Jena, M. Antioxidant responses against aluminum metal stress in Geitlerinema amphibium. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.H.; Xu, C.M.; Zhao, B.; Wang, X.D.; Wang, Y.C. Improved Al tolerance of saffron (Crocus sativus L.) by exogenous polyamines. Acta Physiol. Plant 2008, 30, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.F.; Shen, R.F.; Nagao, S.; Tanimoto, E. Aluminum targets elongating cells by reducing cell wall extensibility in wheat roots. Plant Cell Physiol. 2004, 45, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene ID | Gene Name | N-amino Acids | Molecular Weight | Theoretical pI | Transmembrane Domain | Subcellular Localization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CmaCh02G014150 | CmaALMT1 | 539 | 49624.01 | 8.03 | 6 | Plas |

| CmaCh04G015300 | CmaALMT2 | 570 | 64330.74 | 6.56 | 5 | Plas |

| CmaCh06G005250 | CmaALMT3 | 451 | 49427.12 | 6.89 | 6 | Plas |

| CmaCh07G008230 | CmaALMT4 | 473 | 52024.12 | 6.24 | 6 | Plas |

| CmaCh08G001080 | CmaALMT5 | 478 | 52692.11 | 5.84 | 7 | Plas |

| CmaCh10G002420 | CmaALMT6 | 570 | 64065.79 | 6.49 | 6 | Plas |

| CmaCh10G008660 | CmaALMT7 | 915 | 100938.32 | 8.31 | 11 | Nucl |

| CmaCh10G008670 | CmaALMT8 | 328 | 36890.29 | 9.26 | 6 | Plas |

| CmaCh11G002660 | CmaALMT9 | 576 | 64695.56 | 6.17 | 6 | Plas |

| CmaCh11G009010 | CmaALMT10 | 712 | 77716.19 | 8.46 | 5 | Plas |

| CmaCh11G009020 | CmaALMT11 | 449 | 49716.03 | 8.56 | 6 | Plas |

| CmaCh14G003580 | CmaALMT12 | 467 | 51243.36 | 8.35 | 6 | Plas |

| CmaCh18G010330 | CmaALMT13 | 1215 | 136721.87 | 6.56 | 5 | Plas |

| CmaCh19G000480 | CmaALMT14 | 436 | 48169.09 | 8.61 | 5 | Plas |

| CmaCh19G004590 | CmaALMT15 | 519 | 57705.82 | 8.99 | 5 | Plas |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guo, X.; Wang, M.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C. Expression Profiling of the Aluminum-Activated Malate Transporter (ALMT) Gene Family in Pumpkin in Response to Aluminum Stress and Exogenous Polyamines. Plants 2025, 14, 3745. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243745

Guo X, Wang M, Chen Q, Zhang Y, Zhang C. Expression Profiling of the Aluminum-Activated Malate Transporter (ALMT) Gene Family in Pumpkin in Response to Aluminum Stress and Exogenous Polyamines. Plants. 2025; 14(24):3745. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243745

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Xinqi, Mingshan Wang, Qiang Chen, Ying Zhang, and Chong Zhang. 2025. "Expression Profiling of the Aluminum-Activated Malate Transporter (ALMT) Gene Family in Pumpkin in Response to Aluminum Stress and Exogenous Polyamines" Plants 14, no. 24: 3745. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243745

APA StyleGuo, X., Wang, M., Chen, Q., Zhang, Y., & Zhang, C. (2025). Expression Profiling of the Aluminum-Activated Malate Transporter (ALMT) Gene Family in Pumpkin in Response to Aluminum Stress and Exogenous Polyamines. Plants, 14(24), 3745. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243745