Astaxanthin as a Natural Photoprotective Agent: In Vitro and In Silico Approach to Explore a Multi-Targeted Compound

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

2.2. Antioxidant Capacity

- DPPH radical scavenging activity assay

- ABTS radical scavenging activity assay

- NBT/Riboflavin/SOD test

2.3. Cell Line

2.4. Cell Proliferation

2.5. UVB Radiation

2.6. Wound Healing

2.7. Cell Adhesion Assay

2.8. Assessment of Intracellular ROS Production

2.9. Cellular Lysosomal Enzyme Activity

2.10. Measurement of Nitric Oxide (NO) Production

2.11. Acridine Orange/Ethidium Bromide (AO/EtBr) Staining

3. Molecular Docking Procedure

3.1. Formulation of a Cream Based on the Astaxanthin and Estimation of the Sun Protection Factor (SPF) In Vitro

- EE(λ): represents the erythemal effect spectrum;

- I(λ): denotes the solar intensity spectrum;

- (λ): is the absorbance of the tested sample at each wavelength;

- CF: corresponds to the correction factor, which is equal to 10.

3.2. Statistical Analysis

3.3. Antioxidant Activity of Astaxanthin

3.4. Effect of Astaxanthin on HaCaT Cell Viability

3.5. Protective Effect of Astaxanthin on UVB-Induced Cytotoxicity

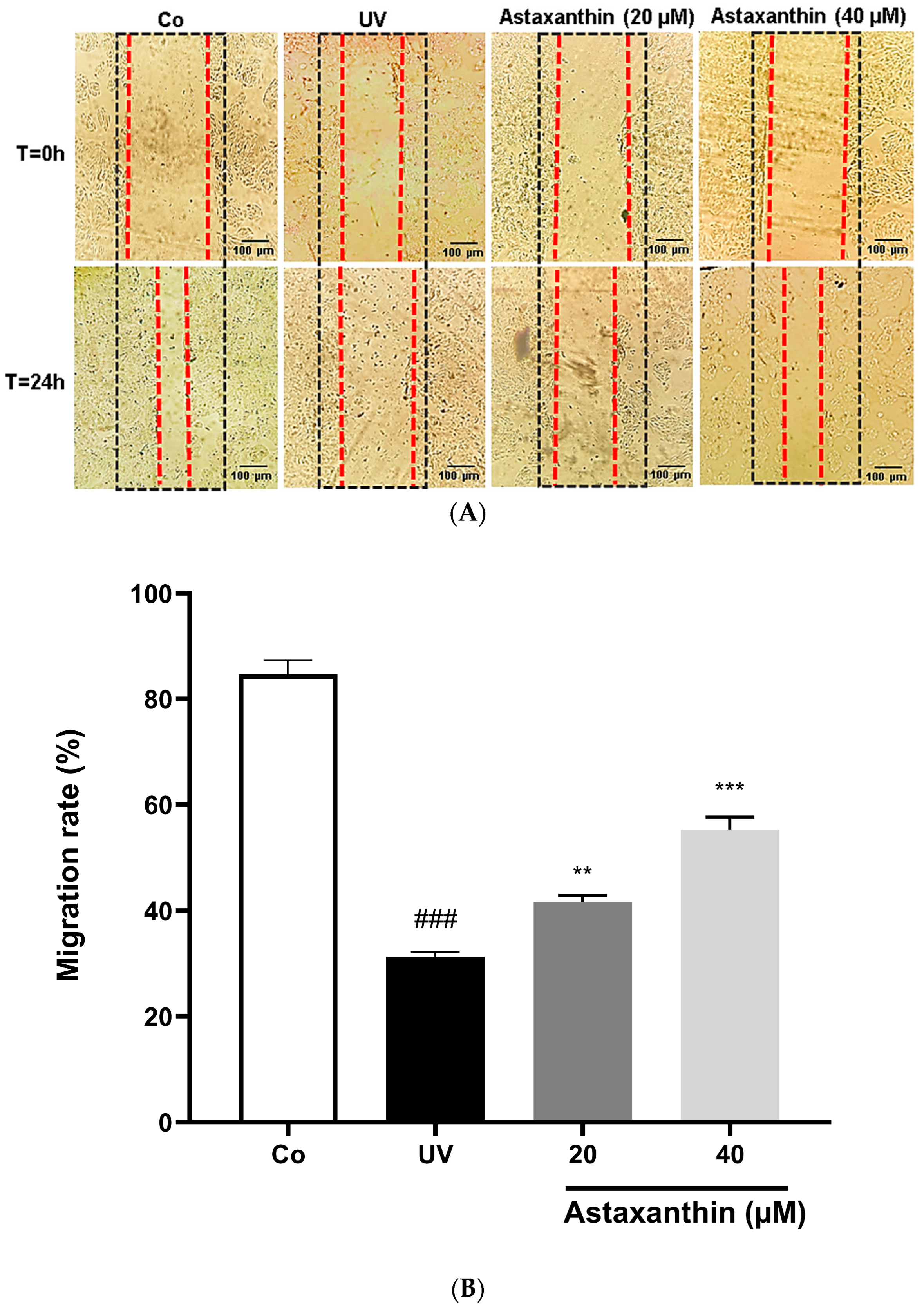

3.6. Effect of Astaxanthin on UVB-Treated Cell Migration

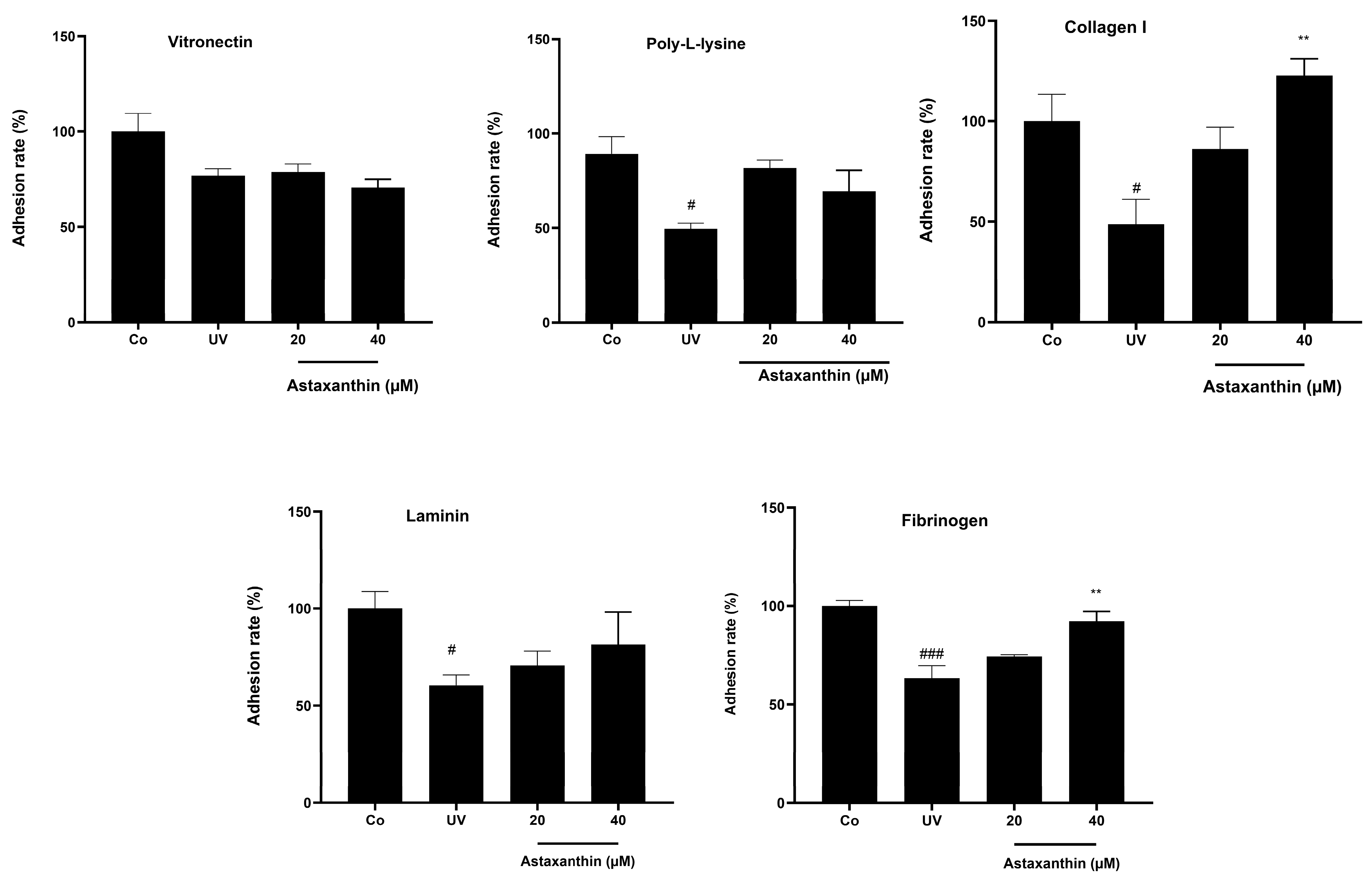

3.7. Effect of Astaxanthin on Cell Adhesion

3.8. Effect of Astaxanthin Against UV-Induced Apoptosis

3.9. Effects of Astaxanthin Supplementation on UVB-Induced ROS Production in HaCaT Cells

3.10. Effect of Astaxanthin on Nitric Oxide Production in UV-Treated HaCaT Cells

3.11. Effect of Astaxanthin on Lysosomal Stability in UV-Treated HaCaT Cells

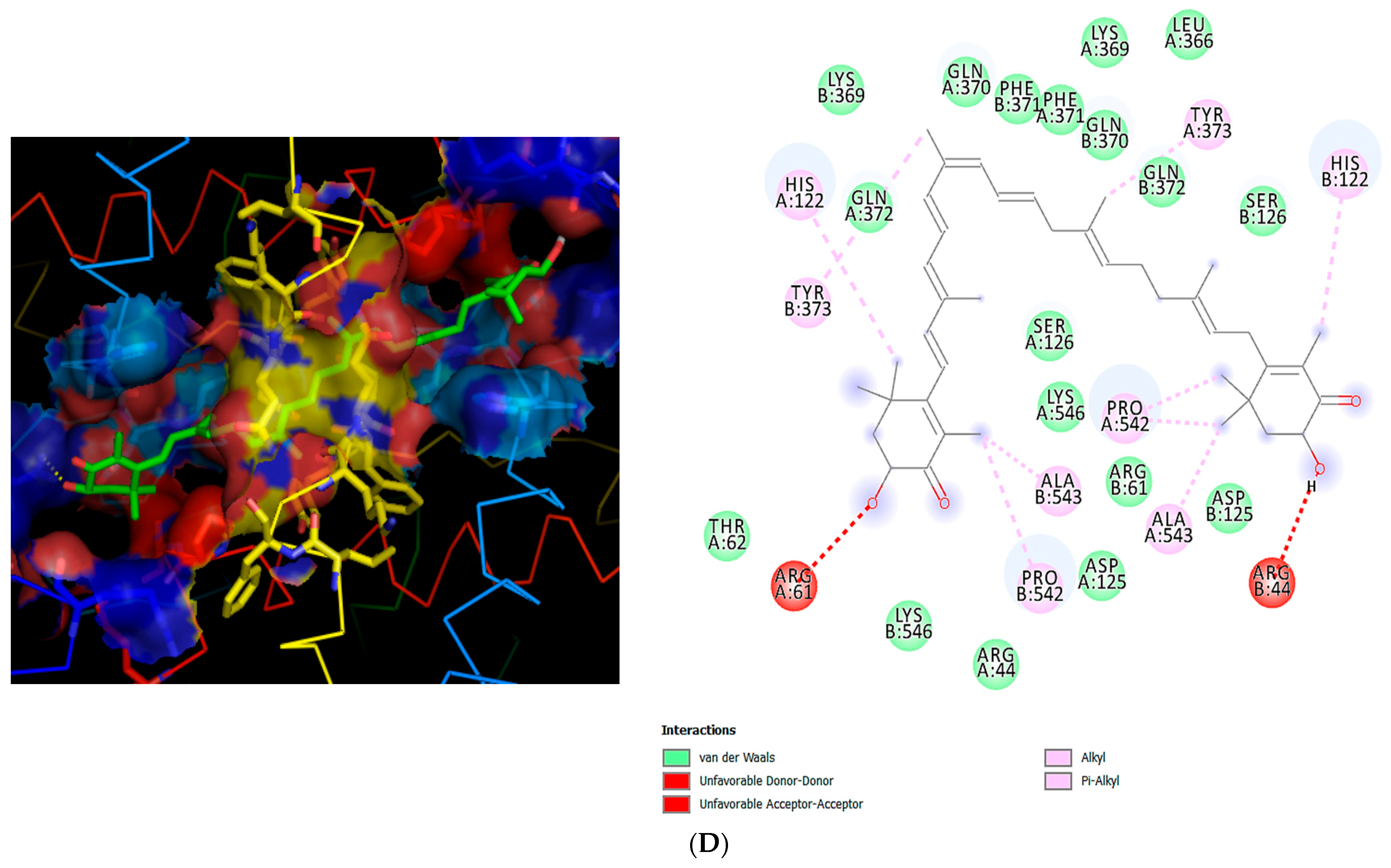

4. Molecular Docking

5. Assessment of SPF Value of a Cream Enriched with 0.5% Astaxanthin

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Milito, A.; Castellano, I.; Damiani, E. From Sea to Skin: Is There a Future for Natural Photoprotectants? Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeifer, G.P. Mechanisms of UV-Induced Mutations and Skin Cancer. Genome Instab. Dis. 2020, 1, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Orazio, J.; Jarrett, S.; Amaro-Ortiz, A.; Scott, T. UV Radiation and the Skin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 12222–12248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussen, N.H.a.; Abdulla, S.K.; Ali, N.M.; Ahmed, V.A.; Hasan, A.H.; Qadir, E.E. Role of Antioxidants in Skin Aging and the Molecular Mechanism of ROS: A Comprehensive Review. Asp. Mol. Med. 2025, 5, 100063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, J.; Chien, A.L. Photoprotection for Skin of Color. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2022, 23, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, S.L.; Lim, H.W. A Review of Inorganic UV Filters Zinc Oxide and Titanium Dioxide. Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2019, 35, 442–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clergeaud, F.; Giraudo, M.; Rodrigues, A.M.S.; Thorel, E.; Lebaron, P.; Stien, D. On the Fate of Butyl Methoxydibenzoylmethane (Avobenzone) in Coral Tissue and Its Effect on Coral Metabolome. Metabolites 2023, 13, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowska, A.; Lewandowski, T.; Rudzki, G.; Próchnicki, M.; Laskowska, B.; Pavlov, S.; Vlasenko, O.; Rudzki, S.; Wójcik, W. The Risk of Melanoma Due to Exposure to Sun and Solarium Use in Poland: A Large-Scale, Hospital Based Case-Control Study. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2023, 24, 2259–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørklund, G.; Gasmi, A.; Lenchyk, L.; Shanaida, M.; Zafar, S.; Mujawdiya, P.K.; Lysiuk, R.; Antonyak, H.; Noor, S.; Akram, M.; et al. The Role of Astaxanthin as a Nutraceutical in Health and Age-Related Conditions. Molecules 2022, 27, 7167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morilla, M.J.; Ghosal, K.; Romero, E.L. More Than Pigments: The Potential of Astaxanthin and Bacterioruberin-Based Nanomedicines. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelazim, K.; Ghit, A.; Assal, D.; Dorra, N.; Noby, N.; Khattab, S.N.; El Feky, S.E.; Hussein, A. Production and Therapeutic Use of Astaxanthin in the Nanotechnology Era. Pharmacol. Rep. 2023, 75, 771–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarasin, A. The Molecular Pathways of Ultraviolet-Induced Carcinogenesis. Mutat. Res. 1999, 428, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenneisen, P.; Sies, H.; Scharffetter-Kochanek, K. Ultraviolet-B Irradiation and Matrix Metalloproteinases: From Induction via Signaling to Initial Events. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2002, 973, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, J.-P.; Peng, J.; Yin, K.; Wang, J.-H. Potential Health-Promoting Effects of Astaxanthin: A High-Value Carotenoid Mostly from Microalgae. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2011, 55, 150–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidd, P. Astaxanthin, Cell Membrane Nutrient with Diverse Clinical Benefits and Anti-Aging Potential. Altern. Med. Rev. 2011, 16, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ambati, R.R.; Phang, S.M.; Ravi, S.; Aswathanarayana, R.G. Astaxanthin: Sources, Extraction, Stability, Biological Activities and Its Commercial Applications—A Review. Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 128–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, P.H.; Norval, M. Ultraviolet Radiation-Induced Immunosuppression and Its Relevance for Skin Carcinogenesis. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2018, 17, 1872–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komatsu, T.; Sasaki, S.; Manabe, Y.; Hirata, T.; Sugawara, T. Preventive Effect of Dietary Astaxanthin on UVA-Induced Skin Photoaging in Hairless Mice. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davinelli, S.; Nielsen, M.E.; Scapagnini, G. Astaxanthin in Skin Health, Repair, and Disease: A Comprehensive Review. Nutrients 2018, 10, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Matsumoto, T.; Takuwa, M.; Saeed Ebrahim Shaiku Ali, M.; Hirabashi, T.; Kondo, H.; Fujino, H. Protective Effects of Astaxanthin Supplementation against Ultraviolet-Induced Photoaging in Hairless Mice. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshihisa, Y.; Rehman, M.U.; Shimizu, T. Astaxanthin, a Xanthophyll Carotenoid, Inhibits Ultraviolet-Induced Apoptosis in Keratinocytes. Exp. Dermatol. 2014, 23, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Focsan, A.L.; Polyakov, N.E.; Kispert, L.D. Photo Protection of Haematococcus pluvialis Algae by Astaxanthin: Unique Properties of Astaxanthin Deduced by EPR, Optical and Electrochemical Studies. Antioxidants 2017, 6, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, B.Y.; Park, S.H.; Yun, S.Y.; Yu, D.S.; Lee, Y.B. Astaxanthin Protects Ultraviolet B-Induced Oxidative Stress and Apoptosis in Human Keratinocytes via Intrinsic Apoptotic Pathway. Ann. Dermatol. 2022, 34, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, W.; Li, J.; Rajabi, S. Molecular Mechanisms, Endurance Athlete, and Synergistic Therapeutic Effects of Marine-Derived Antioxidant Astaxanthin Supplementation and Exercise in Cancer, Metabolic Diseases, and Healthy Individuals. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 13, e70470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baliyan, S.; Mukherjee, R.; Priyadarshini, A.; Vibhuti, A.; Gupta, A.; Pandey, R.P.; Chang, C.-M. Determination of Antioxidants by DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity and Quantitative Phytochemical Analysis of Ficus Religiosa. Molecules 2022, 27, 1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant Activity Applying an Improved ABTS Radical Cation Decolorization Assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, L.R.; Kumar, S.N.; Das, A.A.; Nambisan, B.; Shabna, A.; Mohandas, C.; Anto, R.J. In Vitro Evaluation of the Antioxidant, 3,5-Dihydroxy-4-Ethyl-Trans-Stilbene (DETS) Isolated from Bacillus Cereus as a Potent Candidate against Malignant Melanoma. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.-A.; Bae, D.; Oh, K.-N.; Oh, D.-R.; Kim, Y.; Kim, Y.; Jeong Im, S.; Choi, E.; Lee, S.; Kim, M.; et al. Protective Effects of Quercus Acuta Thunb. Fruit Extract against UVB-Induced Photoaging through ERK/AP-1 Signaling Modulation in Human Keratinocytes. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2022, 22, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Geng, F.; Tang, X.; Yu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Song, B.; Tang, Z.; Wang, B.; Ye, B.; Yu, D.; et al. UV Radiation-Induced Peptides in Frog Skin Confer Protection against Cutaneous Photodamage through Suppressing MAPK Signaling. MedComm 2024, 5, e625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Lai, X.; Li, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhang, H.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Yan, Y.; Wang, B. UVB-Induced Necroptosis of the Skin Cells via RIPK3-MLKL Activation Independent of RIPK1 Kinase Activity. Cell Death Discov. 2025, 11, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varol, M. Cell-Extracellular Matrix Adhesion Assay. Methods Mol. Biol. 2020, 2109, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Xue, X. Detection of Total Reactive Oxygen Species in Adherent Cells by 2’,7’-Dichlorodihydrofluorescein Diacetate Staining. J. Vis. Exp. 2020, 160, e60682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löffler, B.M.; Hesse, B.; Kunze, H. A Combined Assay of Three Lysosomal Marker Enzymes: Acid Phosphatase, Beta-D-Glucuronidase, and Beta-N-Acetyl-D-Hexosaminidase. Anal. Biochem. 1984, 142, 312–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, D.; Tripathi, A.; Al Ali, H.; Shahi, Y.; Mishra, K.K.; Alarifi, S.; Alkahtane, A.A.; Manohardas, S. ROS-Dependent Bax/Bcl2 and Caspase 3 Pathway-Mediated Apoptosis Induced by Zineb in Human Keratinocyte Cells. Onco Targets Ther. 2018, 11, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayre, R.M.; Agin, P.P.; LeVee, G.J.; Marlowe, E. A Comparison of in Vivo and in Vitro Testing of Sunscreening Formulas. Photochem. Photobiol. 1979, 29, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budzianowska, A.; Banaś, K.; Budzianowski, J.; Kikowska, M. Antioxidants to Defend Healthy and Youthful Skin—Current Trends and Future Directions in Cosmetology. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brotosudarmo, T.H.P.; Limantara, L.; Setiyono, E. Heriyanto, null Structures of Astaxanthin and Their Consequences for Therapeutic Application. Int. J. Food Sci. 2020, 2020, 2156582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sztretye, M.; Dienes, B.; Gönczi, M.; Czirják, T.; Csernoch, L.; Dux, L.; Szentesi, P.; Keller-Pintér, A. Astaxanthin: A Potential Mitochondrial-Targeted Antioxidant Treatment in Diseases and with Aging. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 3849692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarneshan, S.N.; Fakhri, S.; Farzaei, M.H.; Khan, H.; Saso, L. Astaxanthin Targets PI3K/Akt Signaling Pathway toward Potential Therapeutic Applications. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 145, 111714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-J.; Bai, S.-K.; Lee, K.-S.; Namkoong, S.; Na, H.-J.; Ha, K.-S.; Han, J.-A.; Yim, S.-V.; Chang, K.; Kwon, Y.-G.; et al. Astaxanthin Inhibits Nitric Oxide Production and Inflammatory Gene Expression by Suppressing I(Kappa)B Kinase-Dependent NF-kappaB Activation. Mol. Cells 2003, 16, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davinelli, S.; Saso, L.; D’Angeli, F.; Calabrese, V.; Intrieri, M.; Scapagnini, G. Astaxanthin as a Modulator of Nrf2, NF-κB, and Their Crosstalk: Molecular Mechanisms and Possible Clinical Applications. Molecules 2022, 27, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhen, A.X.; Kang, K.A.; Piao, M.J.; Madushan Fernando, P.D.S.; Lakmini Herath, H.M.U.; Hyun, J.W. Protective Effects of Astaxanthin on Particulate Matter 2.5-induced Senescence in HaCaT Keratinocytes via Maintenance of Redox Homeostasis. Exp. Ther. Med. 2024, 28, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Yue, J.; Lei, Q.; Gou, X.; Chen, S.-Y.; He, Y.-Y.; Wu, X. Ultraviolet B (UVB) Inhibits Skin Wound Healing by Affecting Focal Adhesion Dynamics. Photochem. Photobiol. 2015, 91, 909–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, H.; Yamaguchi, H.; Yamada, T. Vinculin Migrates to the Cell Membrane of Melanocytes After UVB Irradiation. BPB Rep. 2020, 3, 126–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lim, J.W.; Kim, H. Astaxanthin Inhibits Matrix Metalloproteinase Expression by Suppressing PI3K/AKT/mTOR Activation in Helicobacter Pylori-Infected Gastric Epithelial Cells. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritto, D.; Tanasawet, S.; Singkhorn, S.; Klaypradit, W.; Hutamekalin, P.; Tipmanee, V.; Sukketsiri, W. Astaxanthin Induces Migration in Human Skin Keratinocytes via Rac1 Activation and RhoA Inhibition. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2017, 11, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Li, Y.; Yue, B.Y.J.T. Oxidative Stress Affects Cytoskeletal Structure and Cell-Matrix Interactions in Cells from an Ocular Tissue: The Trabecular Meshwork. J. Cell. Physiol. 1999, 180, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuluaga, M.; Barzegari, A.; Letourneur, D.; Gueguen, V.; Pavon-Djavid, G. Oxidative Stress Regulation on Endothelial Cells by Hydrophilic Astaxanthin Complex: Chemical, Biological, and Molecular Antioxidant Activity Evaluation. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 8073798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, D.; Wen, X.; Liu, L.; Wang, L.; Zhou, X.; Li, Y.; Zeng, X.; He, G.; Jiang, X. Sanshool Improves UVB-Induced Skin Photodamage by Targeting JAK2/STAT3-Dependent Autophagy. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Chu, Z.; Yang, C.; Yang, T.; Yang, Y.; Wu, H.; Sun, J. Discovery of Potent STAT3 Inhibitors Using Structure-Based Virtual Screening, Molecular Dynamic Simulation, and Biological Evaluation. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1287797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Guan, J.-L. Focal Adhesion Kinase and Its Signaling Pathways in Cell Migration and Angiogenesis. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2011, 63, 610–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, A.; Chaturvedi, S.S.; Fields, G.B.; Karabencheva-Christova, T.G. A Synergy Between the Catalytic and Structural Zn(II) Ions and the Enzyme and Substrate Dynamics Underlies the Structure-Function Relationships of Matrix Metalloproteinase Collagenolysis. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 26, 583–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caley, M.P.; Martins, V.L.C.; O’Toole, E.A. Metalloproteinases and Wound Healing. Adv. Wound Care 2015, 4, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale Wilson, B.; Moon, S.; Armstrong, F. Comprehensive Review of Ultraviolet Radiation and the Current Status on Sunscreens. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol. 2012, 5, 18–23. [Google Scholar]

| Protein (PDB) | Binding Energy (kcal/mol) | Redock | Residues Involved | Predicted Biological Effect | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Co- Crystalized Ligand | RMSD (Å) | Binding Energy (kcal/mol) | ||||

| JAK2 (4BBE) | −9.9 | NVP-BBT594 (BBT) | 1.22 | −8.5 | Lys882, Asp994, Glu898, Leu983 | Predicted to possibly interact with kinase activity, leading to decreased STAT3 phosphorylation and attenuation of inflammatory signaling. |

| STAT3 (6NJS) | −7.3 | Phospho-Tyr peptide (PTR) | 1.87 | −7.4 | Arg609, Lys591, Ser636 | Predicted to possibly bind to the SH2 domain, preventing dimerization and transcriptional activation. |

| FAK (4Q9S) | −8.3 | TAE226 analog (52Q) | 1.58 | −7.1 | Lys454, Asp564, Leu567, Gly563 | Predicted to stabilize the ATP-binding site, enhancing adhesion and migration signaling. |

| COX-2 (5IKR) | −8.6 | Acetylated ligand (ACT) | 1.46 | −7.6 | Arg120, Tyr355, Ser530, His90 | Predicted to possibly inhibit COX-2 activity, reducing production of pro-inflammatory mediators. |

| NF-κB (1NFI) | −8.7 | κB DNA duplex (DNA) | 2.25 | −8.0 | Lys221, Glu260, Ser276, Asp243 | Predicted to possibly block the DNA-binding domain, leading to suppression of inflammatory gene transcription. |

| MMP2 (1CK7) | −8.8 | Hydroxamate inhibitor (ANH) | 1.32 | −8.3 | His403, Glu404, His409, Leu397 (Zn2+ site) | May interfere with catalytic site, limiting matrix degradation and promoting tissue repair. |

| MMP9 (1L6J) | −9.0 | Hydroxamate inhibitor (XCT) | 1.28 | −8.7 | His401, Glu402, His405, Leu188 (Zn2+ site) | May interfere with catalytic site, exerting protective and pro-regenerative effects. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Österreichische Pharmazeutische Gesellschaft. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lahmar, A.; Abdelaziz, B.; Gouader, N.; Salek, A.; Waer, I.; Ghedira, L.C. Astaxanthin as a Natural Photoprotective Agent: In Vitro and In Silico Approach to Explore a Multi-Targeted Compound. Sci. Pharm. 2026, 94, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/scipharm94010008

Lahmar A, Abdelaziz B, Gouader N, Salek A, Waer I, Ghedira LC. Astaxanthin as a Natural Photoprotective Agent: In Vitro and In Silico Approach to Explore a Multi-Targeted Compound. Scientia Pharmaceutica. 2026; 94(1):8. https://doi.org/10.3390/scipharm94010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleLahmar, Aida, Balkis Abdelaziz, Nahla Gouader, Abir Salek, Imen Waer, and Leila Chekir Ghedira. 2026. "Astaxanthin as a Natural Photoprotective Agent: In Vitro and In Silico Approach to Explore a Multi-Targeted Compound" Scientia Pharmaceutica 94, no. 1: 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/scipharm94010008

APA StyleLahmar, A., Abdelaziz, B., Gouader, N., Salek, A., Waer, I., & Ghedira, L. C. (2026). Astaxanthin as a Natural Photoprotective Agent: In Vitro and In Silico Approach to Explore a Multi-Targeted Compound. Scientia Pharmaceutica, 94(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/scipharm94010008