Computational Workflow for Chemical Compound Analysis: From Structure Generation to Molecular Docking

Abstract

1. Introduction

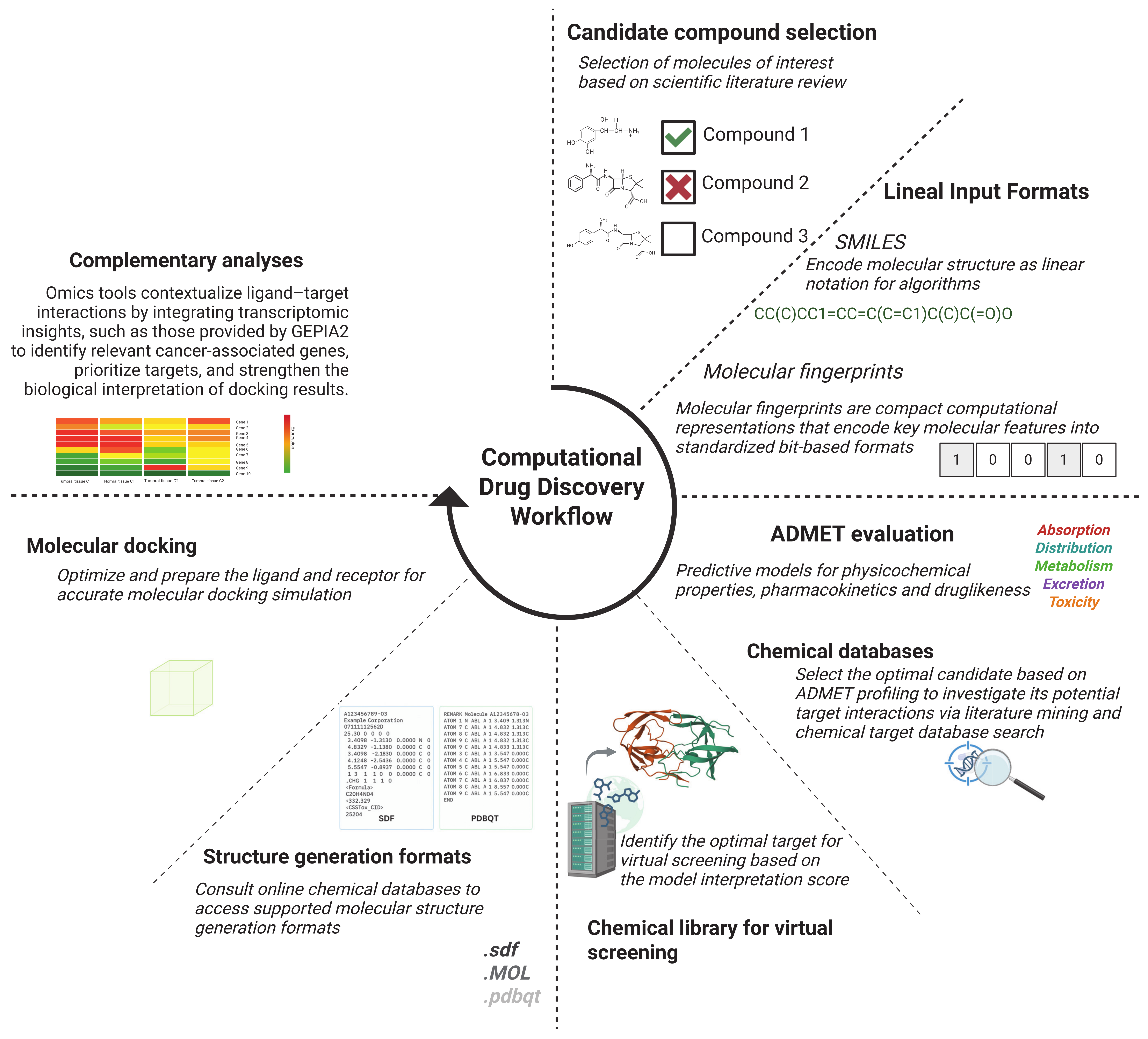

2. Chemical Databases and Libraries in Virtual Screening

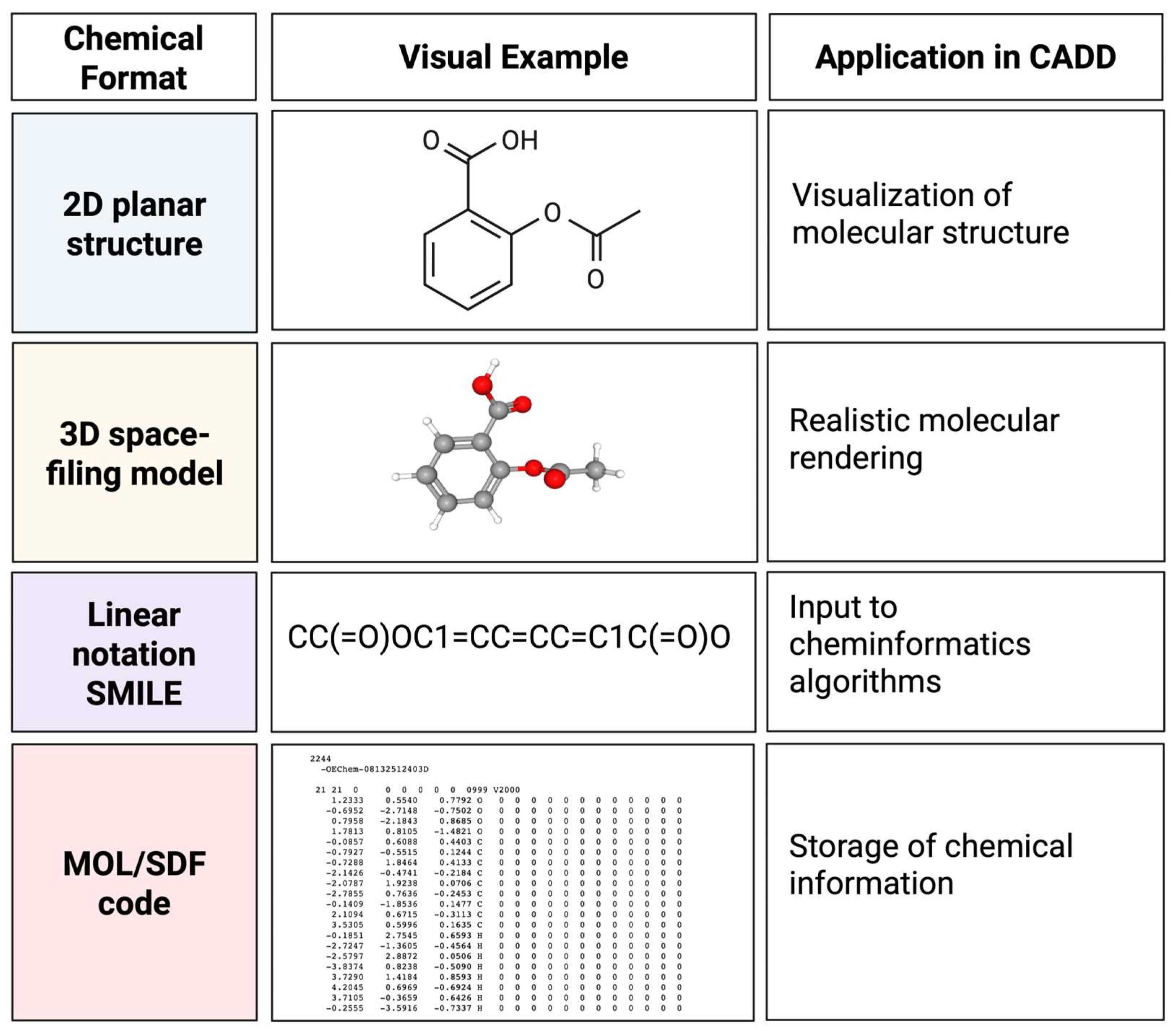

3. Chemical Structure Generation and Linear Input Formats

4. ADMET Property Evaluation

5. Target Prediction and Receptor Selection

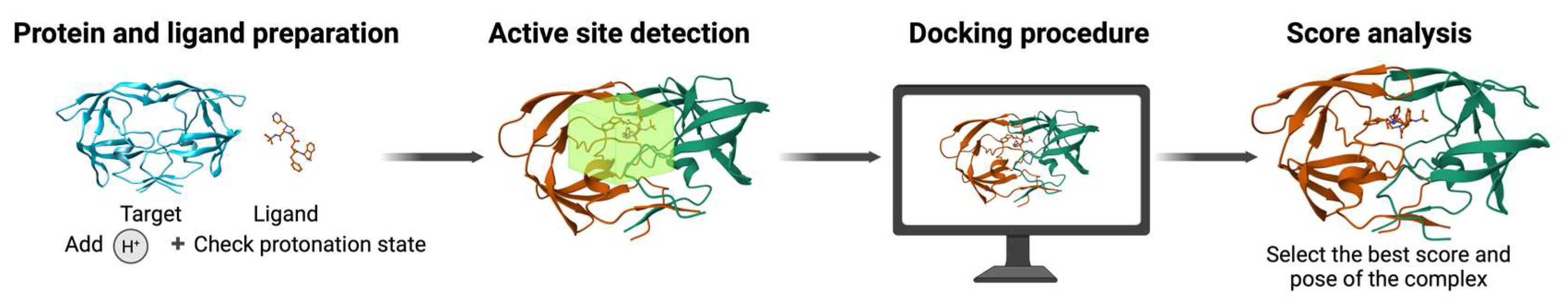

6. Molecular Docking: Evaluating Ligand–Protein Binding Affinity

| Web Server | Tools/Features | Suggested Use Cases | URL | Cite |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PatchDock | Geometry-based docking; detects shape complementarity with minimal clashes and large interface areas | Protein–protein, protein–ligand, and protein–DNA docking | https://bioinfo3d.cs.tau.ac.il/PatchDock/ (accessed on 5 October 2025) | [130] |

| ZDOCK | Protein–protein docking using 3D FFT; statistical potentials; improved speed (>8×) and reduced memory | Large scale protein–protein docking, flexible molecule docking | https://zdock.wenglab.org (accessed on 5 October 2025) | [131] |

| CB-DOCK2 | Blind protein–ligand docking; cavity detection + AutoDock Vina + template guidance (FitDock) | Binding site prediction and docking for homologous proteins | https://cadd.labshare.cn/cb-dock2/index.php (accessed on 5 October 2025) | [111,132] |

| SwissDock | Docking with AutoDock Vina (fast) and Attracting Cavities (accurate); flexible input formats; web access | Small-molecule docking, virtual screening, quick tests, covalent docking | https://www.swissdock.ch (accessed on 7 October 2025) | [133] |

| HADDOCK | Data-driven docking using experimental or biophysical restraints (AIRs) | Protein–protein docking guided by NMR or mutagenesis data | https://rascar.science.uu.nl/haddock2.4/ (accessed on 7 October 2025) | [134] |

| Webina 1 | In-browser AutoDock Vina via WebAssembly; includes PDBQT Convert | Quick ligand–receptor docking; teaching and rapid tests | https://durrantlab.pitt.edu/webina/ (accessed on 7 October 2025) | [135] |

| ProteinsPlus | Tools for structure check (EDIA), hydrogen placement (Protoss), conformations (SIENA), interaction diagrams (PoseView), interface classification (HyPPI), pocket detection and druggability (DoGSiteScorer) | Preprocessing, binding site analysis, early-stage modeling | https://proteins.plus (accessed on 7 October 2025) | [136] |

| HPEPDOCK 2.0 | Blind protein–peptide docking; hierarchical algorithm with MODPEP ensembles; global and local docking | Protein–peptide interaction modeling; global and local docking | http://huanglab.phys.hust.edu.cn/hpepdock/ (accessed on 11 October 2025) | [137] |

| HawkDock | Deep learning flexible docking (GeoDock); binding affinity (VD-MM/GBSA); mutation analysis | Protein–protein docking, affinity prediction, mutation impact studies | https://cadd.zju.edu.cn/hawkdock/ (accessed on 11 October 2025) | [138,139] |

| EDock | Blind docking with replica exchange Monte Carlo; integrates I-TASSER and COACH | Docking on low-resolution protein models; binding site prediction | https://zhanggroup.org/EDock/ (accessed on 11 October 2025) | [140] |

7. Integrative Workflow Summary

8. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Majumder, S.; Panigrahi, G.K. Advancements in Contemporary Pharmacological Innovation: Mechanistic Insights and Emerging Trends in Drug Discovery and Development. Intell. Pharm. 2025, 3, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapetanovic, I.M. Computer-aided drug discovery and development (CADDD): In Silico-Chemico-Biological Approach. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2008, 171, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou-Yang, S.; Lu, J.; Kong, X.; Liang, Z.; Luo, C.; Jiang, H. Computational Drug Discovery. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2012, 33, 1131–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.; Patel, M.; Shah, M.; Patel, M.; Prajapati, M. Computational Transformation in Drug Discovery: A Comprehensive Study on Molecular Docking and Quantitative Structure Activity Relationship (QSAR). Intell. Pharm. 2024, 2, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brogi, S. Computational Approaches for Drug Discovery. Molecules 2019, 24, 3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baig, H.M.; Ahmad, K.; Roy, S.; Ashraf, J.M.; Adil, M.; Siddiqui, M.H.; Khan, S.; Kamal, M.A.; Provaznik, I.; Choi, I. Computer Aided Drug Design: Success and Limitations. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2016, 22, 572–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pârvu, L. QSAR—A piece of drug design. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2003, 7, 333–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namasivayam, V.; Silbermann, K.; Wiese, M.; Pahnke, J.; Stefan, S.M. C@PA: Computer-Aided Pattern Analysis to Predict Multarget ABC Transporter Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 3350–3366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radaeva, M.; Ban, F.; Zhang, F.; LeBlanc, N.; Lallous, N.; Rennie, P.S.; Gleave, M.E.; Cherkasov, A. Devepent of Novel Inhibitors Targeting the D-Box of the DNA Binding Domain of Androgen Receptor. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ton, A.T.; Foo, J.; Singh, K.; Lee, J.; Kalyta, A.; Morin, H.; Perez, C.; Ban, F.; Leblanc, E.; Lallous, N.; et al. Development of VPC-70619, a Small-Molecule N-Myc Inhibitors as a Potential Therapy for Neuroendocrine Prostate Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Chen, D.; Pan, Y.; Shi, X.; Liu, Q.; Lu, X.; Xu, X.; Chen, G.; Cai, Y. Discover of a Novel MyD88 Inhibitor M20 and its Protection Against Sepsis-Mediated Acute Lung Ingury. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 775117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, B.T.; Bame, E.; Bell, N.; Bohnert, T.; Bowden-Verhoek, J.K.; Bui, M.; Cancilla, M.T.; Conlon, P.; Cullen, P.; Erlanson, D.A.; et al. Utilizing structure based drug design and metabolic soft spot identification to optimize the in vitro potency and in vivo pharmacokinetic properties leading to the discovery of novel reversible Bruto´ns tyrosine inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2021, 44, 116275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.S.; Zhou, Z.Y.; Sun, L.Q.; Yi, H.; Xue, S.T.; Li, Z.R. Structured-based virtual screening towards the discovery of novel FOXM1 inhibitors. Future Med. Chem. 2022, 14, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Yu, X.; Song, Y.; Zeng, H.; Zhang, H.; Chen, B.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; He, Q.; Zhou, W. Screening of and mechanism underlying the action of serum and glucorticoid-regulated kinase 3-targeted drugs againts estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2022, 927, 174982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Jensen, K.; Houang, E.; McRobb, F.M.; Bhat, S.; Svensson, M.; Bochevarov, A.; Day, T.; Dahlgren, M.K.; Bell, J.A.; et al. Discovery of a Novel Class of d-Amino Acid Oxidase Inhibitors Using the Schrödinger Computational Platform. J. Med. Chemistry. 2022, 65, 6775–6802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadybekov, A.A.; Sadybekov, A.V.; Liu, Y.; Illiopoulos-Tsoutsouvas, C.; Huang, X.P.; Pickett, J.; Houser, B.; Patel, N.; Tran, N.K.; Tong, F.; et al. Synthon-based ligand discovery in virtual libraries of over 11 billion compoundss. Nature 2022, 601, 452–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, A.L.; Confair, D.N.; Kim, K.; Barros-Álvarez, X.; Rodriguez, R.M.; Yang, Y.; Kweon, O.S.; Che, T.; McCorvy, J.; Kamber, D.N.; et al. Bespoke library docking for 5HT2A receptor agonists with anti-depressant activity. Nature 2023, 610, 582–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beroza, P.; Crawford, J.J.; Ganichkin, O.; Gendelev, L.; Harris, S.F.; Klein, R.; Miu, A.; Steinbacher, S.; Kligler, F.M.; Lemmen, C. Chemical space docking enables large-scale structured-based virtual screening to discover ROCK1 kinase inhibitors. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortat, Y.; Nedyalkova, M.; Schindler, K.; Kadakia, P.; Demirci, G.; Sovari, S.N.; Crochet, A.; Salentinig, S.; Lattuada, M.; Steiner, O.M.; et al. Computer-Aided Drug Design and Synthesis of Rhenium Clotrimazole Antimicrobial Agents. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, G.M.; Kronenberger, T.; Maltarollo, V.G.; Poso, A.; de Moura Gatti, F.; Almeida, V.M.; Marana, S.R.; Lopes, C.D.; Tezuka, D.Y.; de Albuquerque, S.; et al. Trypanosoma cruzi Sirtuin 2 as Relevant Druggable Target: New Inhibitors Developed by Computer-Aided Drug Design. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Q.; Kumar, A.; Pan, G.; Kelvin, D.J. Nifuroxazide Activates the Parthanatos to Overcome TMPRSS2: ERG Fusion-Positive Prostate Cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2023, 22, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurung, A.B.; Ali, M.A.; Lee, J.; Farah, M.A.; Al-Anazi, K.M. An Updated Review of Computer-Aided Drug Design and Its Application to COVID-19. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 8853056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool, M.; Ahmad, B.; Choi, S. A Structure-Based Drug Discovery Paradigm. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 20, 2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanenkov, Y.A.; Savchuk, N.P.; Ekins, S.; Balakin, K.V. Computational Mapping Tools for Drug Discovery. Drug Discov. Today 2009, 14, 767–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prada-Gracia, D.; Huerta-Yépez, S.; Moreno-Vargas, L.M. Application of Computational Methods for Anticancer Drug Discovery, Design, and Optimization. Bol. Méd. Hosp. Infant. Méx. Engl. Ed. 2016, 73, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, J.D.; Tatonetti, N.P. Informatics and Computational Methods in Natural Product Drug Discovery: A Review and Perspectives. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grisoni, F. Chemical Language Models for de Novo Drug Design: Challenges and Opportunities. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2023, 79, 102527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoichet, B.K. Virtual Screening of Chemical Libraries. Nature 2004, 432, 862–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabe, V.T.; Jhamba, L.A.; Maguire, G.E.M.; Govender, T.; Naicker, T.; Kruger, H.G. Current Trends in Computer Aided Drug Design and a Highlight of Drugs Discovered via Computational Techniques: A Review. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 224, 113705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlsson, J.; Luttens, A. Structure-Based Virtual Screening of Vast Chemical Space as a Starting Point for Drug Discovery. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2024, 87, 102829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grygorenko, O.O.; Radchenko, D.S.; Dziuba, I.; Chuprina, A.; Gubina, K.E.; Moroz, Y.S. Generating Multibillion Chemical Space of Readily Accessible Screening Compounds. iScience 2020, 23, 101681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, J.; Wang, S.; Balius, T.E.; Singh, I.; Levit, A.; Moroz, Y.S.; O’Meara, M.J.; Che, T.; Algaa, E.; Tolmachova, K.; et al. Ultra-Large Library Docking for Discovering New Chemotypes. Nature 2019, 566, 224–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Chen, J.; Cheng, T.; Gindulyte, A.; He, J.; He, S.; Li, Q.; Shoemaker, B.A.; Thiessen, P.A.; Yu, B.; et al. PubChem 2025 Update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D1516–D1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M.; Nowotka, M.; Papadatos, G.; Dedman, N.; Gaulton, A.; Atkinson, F.; Bellis, L.; Overington, J. ChEMBL Web Services: Streamlining Access to Drug Discovery Data and Utilities. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, 612–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zdrazil, B.; Felix, E.; Hunter, F.; Manners, E.J.; Blackshaw, J.; Corbett, S.; de Veij, M.; Ioannidis, H.; Lopez, D.M.; Mosquera, J.F.; et al. The ChEMBL Database in 2023: A Drug Discovery Platform Spanning Multiple Bioactivity Data Types and Time Periods. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, D1180–D1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, J.J.; Tang, K.G.; Young, J.; Dandarchuluun, C.; Wong, B.R.; Khurelbaatar, M.; Moroz, Y.S.; Mayfield, J.; Sayle, R.A. ZINC20—A Free Ultralarge-Scale Chemical Database for Ligand Discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2020, 60, 6065–6073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tingle, B.I.; Tang, K.G.; Castanon, M.; Gutierrez, J.J.; Khurelbaatar, M.; Dandarchuluun, C.; Moroz, Y.S.; Irwin, J.J. ZINC-22─A Free Multi-Billion-Scale Database of Tangible Compounds for Ligand Discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2023, 63, 1166–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, C.; Wilson, M.; Klinger, C.M.; Franklin, M.; Oler, E.; Wilson, A.; Pon, A.; Cox, J.; Chin, N.E.L.; Strawbridge, S.A.; et al. DrugBank 6.0: The DrugBank Knowledgebase for 2024. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, D1265–D1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekhar, V.; Rajan, K.; Kanakam, S.R.S.; Sharma, N.; Weißenborn, V.; Schaub, J.; Steinbeck, C. COCONUT 2.0: A Comprehensive Overhaul and Curation of the Collection of Open Natural Products Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D634–D643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorokina, M.; Merseburger, P.; Rajan, K.; Yirik, M.A.; Steinbeck, C. COCONUT Online: Collection of Open Natural Products Database. J. Cheminform. 2021, 13, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, L.; Thakkar, A.; Mercado, R.; Engkvist, O. Molecular Representations in AI-Driven Drug Discovery: A Review and Practical Guide. J. Cheminform. 2020, 12, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polanski, J.; Gasteiger, J. Computer Representation of Chemical Compounds. In Handbook of Computational Chemistry; Leszczynski, J., Kaczmarek-Kedziera, A., Puzyn, T.G., Papadopoulos, M., Reis, H.K., Shukla, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 1997–2039. ISBN 978-3-319-27282-5. [Google Scholar]

- Walters, W.P. Virtual Chemical Libraries. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 1116–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Shaker, B.; Lee, J.; Choi, S.; Yoon, S.; Singh, M.; Basith, S.; Cui, M.; An, J.; Kang, S.; et al. Employing Automated Machine Learning (AutoML) Methods to Facilitate the In Silico ADMET Properties Prediction. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2025, 65, 3215–3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, A. Dextrosinistral Reading of SMILES Notation: Investigation into Origin of Non-Sense Code from String Manipulations. Digit. Chem. Eng. 2025, 15, 100222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, G.; Mucelini, J.; Soares, M.; Prati, R.; Da Silva, J.; Quiles, M. Machine Learning Prediction of Nine Molecular Properties Based on the SMILES Representation of the QM9 Quantum-Chemistry Dataset. J. Phys. Chem. A 2020, 124, 9854–9866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, V. Machine Learning Prediction of Empirical Polarity Using SMILES Encoding of Organic Solvents. Mol. Divers. 2023, 27, 2331–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjerrum, E.J. SMILES Enumeration as Data Augmentation for Neural Network Modeling of Molecules. arXiv 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjerrum, E.J.; Sattarov, B. Improving Chemical Autoencoder Latent Space and Molecular De Novo Generation Diversity with Heteroencoders. Biomolecules 2018, 8, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mswahili, M.E.; Jeong, Y.-S. Transformer-Based Models for Chemical SMILES Representation: A Comprehensive Literature Review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e39038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPA Appendix F SMILES Notation Tutorial. Sustainable Futures P2 Framework Manual 2012 EPA-748-B12-001. 2012. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2015-05/documents/appendf.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- O’Boyle, N.M. Towards a Universal SMILES Representation—A Standard Method to Generate Canonical SMILES Based on the InChI. J. Cheminform. 2012, 4, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muresan, S.; Sitzmann, M.; Southan, C. Mapping Between Databases of Compounds and Protein Targets. In Bioinformatics and Drug Discovery, 2nd ed.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2012; Volume 910, pp. 145–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Zhou, Y.; Li, L.; Shen, X.; Chen, G.; Wang, X.; Liang, X.; Tan, M.; Huang, Z. Computational Approaches in Preclinical Studies on Drug Discovery and Development. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roney, M.; Mohd Aluwi, M.F.F. The Importance of In-Silico Studies in Drug Discovery. Intell. Pharm. 2024, 2, 578–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valerio, L.G. In Silico Methods. In Encyclopedia of Toxicology, 3rd ed.; Wexler, P., Ed.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 1026–1029. ISBN 978-0-12-386455-0. [Google Scholar]

- Jamrozik, E.; Śmieja, M.; Podlewska, S. ADMET-PrInt: Evaluation of ADMET Properties: Prediction and Interpretation. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2024, 64, 1425–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creanza, T.M.; Delre, P.; Ancona, N.; Lentini, G.; Saviano, M.; Mangiatordi, G.F. Structure-Based Prediction of hERG-Related Cardiotoxicity: A Benchmark Study. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021, 61, 4758–4770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, H. Computational Prediction of Cytochrome P450 Inhibition and Induction. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2020, 35, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilar, S.; Sobarzo-Sánchez, E.; Uriarte, E. In Silico Prediction of P-Glycoprotein Binding: Insights from Molecular Docking Studies. Curr. Med. Chem. 2019, 26, 1746–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E.B.; Hwang, H.; Shelley, M.; Placzek, A.; Rodrigues, J.P.G.L.M.; Suto, R.K.; Wang, L.; Akinsanya, K.; Abel, R. Enabling Structure-Based Drug Discovery Utilizing Predicted Models. Cell 2024, 187, 521–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moroy, G.; Martiny, V.Y.; Vayer, P.; Villoutreix, B.O. Toward in Silico Structure-Based ADMET Prediction in Drug Discovery. Drug Discov. Today 2011, 17, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peter, S.C.; Dhanjal, J.K.; Malik, V.; Radhakrishnan, N.; Jayakanthan, M.; Sundar, D. Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR): Modeling Approaches to Biological Applications. Encycl. Bioinform. Comput. Biol. 2019, 2, 661–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, M.B.; Clewell, H.J.; Lave, T.; Andersen, M.E. Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Modeling: A Tool for Understanding ADMET Properties and Extrapolating to Human. In New Insights into Toxicity and Drug Testing; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissADME: A Free Web Tool to Evaluate Pharmacokinetics, Drug-Likeness and Medicinal Chemistry Friendliness of Small Molecules. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, D.E.V.; Blundell, T.L.; Ascher, D.B. pkCSM: Predicting Small-Molecule Pharmacokinetic and Toxicity Properties Using Graph-Based Signatures. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 4066–4072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.; Li, W.; Zhou, Y.; Shen, J.; Wu, Z.; Liu, G.; Lee, P.W.; Tang, Y. admetSAR: A Comprehensive Source and Free Tool for Assessment of Chemical ADMET Properties. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2012, 52, 3099–3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Lou, C.; Sun, L.; Li, J.; Cai, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, W.; Liu, G.; Tang, Y. admetSAR 2.0: Web-Service for Prediction and Optimization of Chemical ADMET Properties. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 1067–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Shi, S.; Yi, J.; Wang, N.; He, Y.; Wu, Z.; Peng, J.; Deng, Y.; Wang, W.; Wu, C.; et al. ADMETlab 3.0: An Updated Comprehensive Online ADMET Prediction Platform Enhanced with Broader Coverage, Improved Performance, API Functionality and Decision Support. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, W422–W431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, G.; Wu, Z.; Yi, J.; Fu, L.; Yang, Z.; Hsieh, C.; Yin, M.; Zeng, X.; Wu, C.; Lu, A.; et al. ADMETlab 2.0: An Integrated Online Platform for Accurate and Comprehensive Predictions of ADMET Properties. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W5–W14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swanson, K.; Walther, P.; Leitz, J.; Mukherjee, S.; Wu, J.C.; Shivnaraine, R.V.; Zou, J. ADMET-AI: A Machine Learning ADMET Platform for Evaluation of Large-Scale Chemical Libraries. Bioinformatics 2024, 40, btae416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, N.K.; Agarwal, S.; Raghava, G.P. Prediction of Cytochrome P450 Isoform Responsible for Metabolizing a Drug Molecule. BMC Pharmacol. 2010, 10, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filimonov, D.A.; Lagunin, A.A.; Gloriozova, T.A.; Rudik, A.V.; Druzhilovskii, D.S.; Pogodin, P.V.; Poroikov, V.V. Prediction of the Biological Activity Spectra of Organic Compounds Using the Pass Online Web Resource. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2014, 50, 444–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Tao, Y.; Sha, C.; He, M.; Li, X. DrugMetric: Quantitative Drug-Likeness Scoring Based on Chemical Space Distance. Brief. Bioinform. 2024, 25, bbae321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roskoski, R., Jr. Properties of FDA-approved small molecule protein kinase inhibitors. Pharmacol. Res. 2019, 144, 19–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghose, A.K.; Viswanadhan, V.N.; Wendoloski, J.J. A Knowledge-Based Approach in Designing Combinatorial or Medicinal Chemistry Libraries for Drug Discovery. 1. A Qualitative and Quantitative Characterization of Known Drug Databases. J. Comb. Chem. 1999, 1, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veber, D.F.; Johnson, S.R.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Smith, B.R.; Ward, K.W.; Kopple, K.D. Molecular Properties That Influence the Oral Bioavailability of Drug Candidates. J. Med. Chem. 2002, 45, 2615–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muegge, I.; Heald, S.L.; Brittelli, D. Simple Selection Criteria for Drug-like Chemical Matter. J. Med. Chem. 2001, 44, 1841–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicak, Y. Synthesis, Predictions of Drug-Likeness, and Pharmacokinetic Properties of Some Chiral Thioureas as Potent Enzyme Inhibition Agents. Turk. J. Chem. 2021, 46, 665–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, W.J.; Kenneth, M.M.; Baldwin, J.J. Prediction of Drug Absorption Using Multivariate Statistics. J. Med. Chem. 2000, 43, 3867–3877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kralj, S.; Jukič, M.; Bren, U. Molecular Filters in Medicinal Chemistry. Encyclopedia 2023, 3, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, P.; Kemmler, E.; Dunkel, M.; Preissner, R. ProTox 3.0: A Webserver for the Prediction of Toxicity of Chemicals. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, W513–W520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patlewicz, G.; Jeliazkova, N.; Safford, R.J.; Worth, A.P.; Aleksiev, B. An Evaluation of the Implementation of the Cramer Classification Scheme in the Toxtree Software. SAR QSAR Environ. Res. 2008, 19, 495–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravarti, S.; Saiakhov, R.D. MultiCASE Platform for In Silico Toxicology. In In Silico Methods for Predicting Drug Toxicity; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana: New York, NY, USA, 2022; Volume 2425, pp. 497–518. ISBN 978-1-0716-1960-5. [Google Scholar]

- Raheem, A.K.A.; Dhannoon, B.N. Comprehensive Review on Drug-Target Interaction Prediction—Latest Developments and Overview. Curr. Drug Discov. Technol. 2024, 21, 56–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasul, H.O.; Ghafour, D.D.; Aziz, B.K.; Hassan, B.A.; Rashid, T.A.; Kivrak, A. Decoding Drug Discovery: Exploring A-to-Z In Silico Methods for Beginners. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2025, 197, 1453–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Wu, F.; Yang, N.; Zhan, X.; Liao, J.; Mai, S.; Huang, Z. In Silico Methods for Identification of Potential Therapeutic Targets. Interdiscip. Sci. Comput. Life Sci. 2022, 14, 285–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Li, W.; Liu, G.; Tang, Y. Network-Based Methods for Prediction of Drug-Target Interactions. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Wu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, M.; Li, W.; Liu, G.; Tang, Y. Network-Based Methods and Their Applications in Drug Discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2024, 64, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Caba, K.; Ballester, P. A Precise Comparison of Molecular Target Prediction Methods. Digit. Discov. 2025, 4, 2548–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenes-Vargas, K.; Pazos, A.; Munteanu, C.R.; Perez-Castillo, Y.; Tejera, E. Prediction of Compound-Target Interaction Using Several Artificial Intelligence Algorithms and Comparison with a Consensus-Based Strategy. J. Cheminform. 2024, 16, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.-Q.; Ye, Q.; Ding, J.; Yin, M.-Z.; Lu, A.-P.; Chen, X.; Hou, T.; Cao, D.-S. Current Advances in Ligand-Based Target Prediction. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2020, 11, e1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durant, J.L.; Leland, B.A.; Henry, D.R.; Nourse, J.G. Reoptimization of MDL Keys for Use in Drug Discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2002, 42, 1273–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Ren, P.; Yang, H.; Zheng, J.; Bai, F. TEFDTA: A Transformer Encoder and Fingerprint Representation Combined Prediction Method for Bonded and Non-Bonded Drug–Target Affinities. Bioinformatics 2024, 40, btad778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Z.-J.; Dong, J.; Che, Y.-J.; Zhu, M.-F.; Wen, M.; Wang, N.-N.; Wang, S.; Lu, A.-P.; Cao, D.-S. TargetNet: A Web Service for Predicting Potential Drug–Target Interaction Profiling via Multi-Target SAR Models. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2016, 30, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, K.; Goede, A.; Preissner, R.; Gohlke, B.-O. SuperPred 3.0: Drug Classification and Target Prediction—A Machine Learning Approach. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, W726–W731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissTargetPrediction: Updated Data and New Features for Efficient Prediction of Protein Targets of Small Molecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W357–W364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keiser, M.J.; Roth, B.L.; Armbruster, B.N.; Ernsberger, P.; Irwin, J.J.; Shoichet, B.K. Relating Protein Pharmacology by Ligand Chemistry. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007, 25, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, R.P.; Vieira, T.F.; Melo, A.; Suosa, S.F. Chapter 15—In Silico Development of Quorum Sensing Inhibitors. In Recent Trends in Biofilm Science and Technology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 329–357. ISBN 978-0-12-819497-3. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, L.K.Y.; Yada, R.Y. Predicting Global Diet-Disease Relationships at the Atomic Level: A COVID-19 Case Study. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2022, 44, 100804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya, C.G.; Chakraborty, C.; Narayan, V.; Kumar, T. Chapter Ten—Computational Approaches and Resources in Single Amino Acid Substitutions Analysis Toward Clinical Research. In Advances in Protein Chemistry and Structural Biology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; Volume 94, pp. 365–423. ISBN 978-0-12-800168-4. [Google Scholar]

- Gianti, E.; Carnevale, V. Chapter Two—Computational Approaches to Studying Voltage-Gated Ion Channel Modulation by General Anesthetics. In Methods in Enzymology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; Volume 602, pp. 25–59. [Google Scholar]

- Morgnanesi, D.; Heinrichs, E.J.; Mele, A.R.; Wilkinson, S.; Zhou, S.; Kulp, J.L., III. A Computational Chemistry Perspective on the Current Status and Future Direction of Hepatitis B Antiviral Drug Discovery. Antivir. Res. 2015, 123, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanna, V.; Ranganathan, S.; Petrovsky, N. Rational Strucute-Based Drug Design. In Encyclopedia of Bioinformatics and Computational Biology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; Volume 2, pp. 585–600. ISBN 978-0-12-811432-2. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, K.; Kar, S.; Das, R.N. Other Related Techniques; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 357–425. ISBN 978-0-12-801505-6. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, G.; Huey, R.; Lindstrom, W.; Sanner, M.F.; Belew, R.; Goodsell, D.S.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated Docking with Selective Receptor Flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 30, 2785–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BIOVIA, Dassault Systèmes. Discovery Studio, Web-Based Software; Dassault Systèmes: San Diego, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, W.J.; Balius, T.E.; Mulkherjee, S.; Brozell, S.R.; Moustakas, D.; Lang, T.; Case, D.A.; Kuntz, I.D.; Rizzo, R.C. DOCK 6: Impact of New Features and Current Docking Performance. J. Comput. Chem. 2015, 5, 1132–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Geng, C.; Zeng, Q.; Huang, T.; Tang, J.; Chu, Y.; Zhao, K. Dockey: A Modern Integrated Tool for Large-Scale Molecular Docking and Virtual Screening. Brief. Bioinform. 2023, 24, bbad047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, V.A.; Thompson, E.E.; Pique, M.E.; Perez, M.S.; Ten, L.F. DOT2: Macromolecular Docking with Improved Biophysical Models. J. Comput. Chem. 2013, 34, 1743–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Liu, Y.; Gan, J.; Xiao, Z.-X.; Cao, Y. FitDock: Protein–Ligand Docking by Template Fitting. Brief. Bioinform. 2022, 23, bbac087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rarey, M.; Kramer, B.; Lengauer, T.; Klebe, G. A Fast Flexible Docking Method Using an Incremental Construction Algorithm. J. Mol. Biol. 1996, 261, 470–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesner, R.A.; Banks, J.L.; Murphy, R.B.; Halgren, T.A.; Klicic, J.; Mainz, D.T.; Repasky, M.; Knoll, E.H.; Shelley, M.; Perry, J.K.; et al. Glide: A New Approach for Rapid, Accurate Docking and Scoring. 1. Method and Assessment of Docking Accuracy. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 47, 1739–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G.; Willet, P.; Glen, R.C.; Leach, A.R.; Taylor, R. Development and Validation of a Genetic Algorithm for Flexible Docking. J. Mol. Biol. 1997, 267, 727–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Copeland, M.M.; Kundrotas, P.J.; Vakser, I.A. GRAMM Web Server for Protein Docking. In Computational Drug Discovery and Design; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana: New York, NY, USA, 2024; Volume 2714, pp. 101–112. ISBN 978-1-0716-3441-7. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, K.-C.; Chen, Y.-F.; Lin, S.-R.; Yang, J.-M. iGEMDOCK: A Graphical Environment of Enhancing GEMDOCK Using Pharmacological Interactions and Post-Screening Analysis. BMC Bioinform. 2011, 12, S33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Xu, Z. Using LeDock as a Docking Tool for Computational Drug Design. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 218, 012143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terwilliger, T.C.; Klei, H.; Adams, P.D.; Moriarty, N.W.; Cohn, J. Automated Ligand Fitting by Core-Fragment Fitting and Extension into Density. Biol. Crystallogr. 2006, 62, 915–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakkennes, M.L.A.; Buda, F.; Bonnet, S. MetalDock: An Open Access Docking Tool for Easy and Reproducible Docking of Metal Complexes. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2023, 63, 7816–7825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chemical Computing Group ULC. Molecular Operating Environment (MOE); Chemical Computing Group: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen, R.; Christensen, M.H. MolDock: A New Technique for High-Accuracy Molecular Docking. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 3315–3321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shnecke, V.; Swanson, C.A.; Getzoff, E.D.; Tainer, J.A.; Kuhn, L. Screening a Peptidyl Databse for Potential Ligands to Proteins with Side-Chain Flexibility. Proteins Struct. Funct. Genet. 1998, 33, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabier, M.; Gambacorta, N.; Trisciuzzi, D.; Kumar, S.; Nicolotti, O.; Matthew, B. MzDOCK: A Free Ready-to-Use GUI-Based Pipeline for Molecular Docking Simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 2025, 45, 1980–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, R.B.; Philipp, D.M.; Friesner, R.A. A Mixed Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics (QM/MM) Method for Large-Scale Modeling of Chemistry in Protein Environments. J. Comput. Chem. 2000, 21, 1442–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morley, S.D.; Afshar, M. Validation of an Empirical RNA-Ligand Scoring Function for Fast Flexible Docking Using RiboDock. J. Comput.-Aided Mol. Des. 2004, 18, 189–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdonk, M.L.; Cole, J.C.; Taylor, R. SuperStar: A Knowledge-Based Approach for Identifying Interaction Sites in Proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 1999, 289, 1093–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bursulaya, B.; Totrov, M.; Abagyan, R.; Brooks, C.L., 3rd. Comparative study of several algorithms for flexible ligand docking. J. Comput.-Aided Mol. Des. 2003, 17, 755–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, Y.; Cheng, T.; Liu, Z.; Wang, R. Evaluation of the performance of four molecular docking programs on a diverse set of protein complexes. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 2109–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Sun, H.; Yao, X.; Li, D.; Xu, L.; Li, Y.; Tian, S.; Hou, T. Comprehensive evaluation of ten docking programs on a diverse set of protein-ligand complexes: The prediction accuracy of sampling power and scoring power. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 12964–12975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duhovny, D.; Wolfson, H.J. Efficient Unbound Docking of Rigid Molecules. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. 2002, 2452, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, B.G.; Wiehe, K.; Hwang, H.; Kim, B.-H.; Vreven, T.; Weng, Z. ZDOCK Server: Interactive Docking Prediction of Protein-Protein Complexes and Symmetric Multimers. Bioinform. Oxf. Engl. 2014, 30, 1771–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, X.; Gan, J.; Chen, S.; Xiao, Z.-X.; Cao, Y. CB-Dock2: Improved Protein–Ligand Blind Docking by Integrating Cavity Detection, Docking and Homologous Template Fitting. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, W159–W164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosdidier, A.; Zoete, V.; Michielin, O. SwissDock, a Protein-Small Molecule Docking Web Service Based on EADock DSS. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honorato, R.V.; Trellet, M.E.; Jiménez-García, B.; Schaarschmidt, J.J.; Giulini, M.; Reyes, V.; Koukos, P.I.; Rodrigues, J.P.; Karaca, E.; van Zundert, G.C.; et al. The HADDOCK2.4 Web Server for Integrative Modeling of Biomolecular Complexes. Nat. Protoc. 2024, 19, 3219–3241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochnev, Y.; Hellemann, E.; Cassidy, K.C.; Durrant, J.D. Webina: An Open-Source Library and Web App That Runs AutoDock Vina Entirely in the Web Browser. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 4513–4515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöning-Stierand, K.; Diedrich, K.; Ehrt, C.; Flachsenberg, F.; Graef, J.; Sieg, J.; Penner, P.; Poppinga, M.; Ungethüm, A.; Rarey, M. ProteinsPlus: A Comprehensive Collection of Web-Based Molecular Modeling Tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, 611–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Jin, B.; Li, H.; Huang, S.-Y. HPEPDOCK: A Web Server for Blind Peptide-Protein Docking Based on a Hierarchical Algorithm. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, G.; Wang, E.; Wang, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhu, F.; Li, D.; Hou, T. HawkDock: A Web Server to Predict and Analyze the Protein–Protein Complex Based on Computational Docking and MM/GBSA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Jiang, L.; Weng, G.; Shen, C.; Zhang, O.; Liu, M.; Zhang, C.; Gu, S.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; et al. HawkDock Version 2: An Updated Web Server to Predict and Analyze the Structures of Protein–Protein Complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Bell, E.W.; Yin, M.; Zhang, Y. EDock: Blind Protein–Ligand Docking by Replica-exchange Monte Carlo Simulation. J. Cheminform. 2020, 12, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GERÇEK, Z.; CEYHAN, D.; ERÇAĞ, E. Synthesis and Molecular Docking Study of Novel COVID-19 Inhibitors. Turk. J. Chem. 2021, 45, 704–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, S.K.E.; Bhadra, S.; Kumar, N. Exploring Potential Therapeutic Candidates against COVID-19: A Molecular Docking Study. Discov. Mol. 2024, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phosrithong, N.; Ungwitayatorn, J. Molecular Docking Study on Anticancer Activity of Plant-Derived Natural Products. Med. Chem. Res. 2010, 19, 817–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Chander, P.C.; Kumar, V. In Silico Molecular Docking Analysis of Natural Pyridoacridines as Anticancer Agents. Adv. Chem. 2016, 2016, 5409387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ru, X.; Xu, L.; Han, W.; Zou, Q. In silico methods for drug-target interaction prediction. Cell Rep. Methods 2025, 5, 101184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Software | License Type | Main Features | Recommended Use | Cite |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autodock | Open-source | Binding orientation and affinity of small molecules to 3D receptors | Virtual screening, structure-based design, recommended for academic projects | [106] |

| Discovery Studio | Commercial and Academic | Docking with ligand conformational search (Monte Carlo) and LigandFit preparation | Comprehensive modeling, docking workflows, industry-level projects | [107] |

| DOCK | Commercial and Academic | Geometric matching to place ligands/fragments in binding sites; includes solvent effects | Academic research, fragment docking, solvent-inclusive studies | [108] |

| Dockey | Open-source | Graphical interface integrating preparation, parallel docking, interaction detection, and visualization | Comprehensive and user-friendly docking workflows | [109] |

| DOT | Open-source | Docking of macromolecule interactions; predicts binding via electrostatic and van der Waals energies | Protein–protein and large complex docking; biologically relevant models | [110] |

| FitDock | Academic | Improves protein–ligand docking by using similar co-crystal structures; enhances sampling and scoring | Structure-based drug design with accuracy improvement | [111] |

| FlexX | Commercial and Academic | Uses incremental construction: docks ligand fragments | Fast docking of fragment-based ligands in diverse binding pockets | [112] |

| Glide | Commercial | Ligand–receptor docking, supports virtual screening and binding mode prediction | High-precision docking, virtual screening in pharma research | [113] |

| GOLD | Commercial and Academic | Genetic algorithm for ligand binding predictions; flexible across diverse protein targets | Reliable docking in drug discovery, protein–ligand interaction studies | [114] |

| GRAMM | Commercial | Explores intermolecular energy landscape; predicts stable and transient protein–protein docking poses | Protein–protein interaction modeling and complex prediction | [115] |

| iGEMDOCK | Open-source | Identifies pharmacological interactions by virtual screening | Ligand screening and pharmacological interaction prediction | [116] |

| LeDock | Academic | Fast and accurate flexible docking of small molecules; | High-throughput virtual screening and pose prediction | [117] |

| LigandFit | Commercial | Shape-based docking using cavity detection, Monte Carlo conformational search, and grid-based scoring | Protein–ligand docking, pose prediction, and high-throughput virtual screening | [118] |

| MetalDock | Open-source | Specialized in metal–organic docking; supports multiple metal types and automates workflow | Protein, DNA, and biomolecule docking with metal complexes | [119] |

| MOE | Commercial | Integrated modeling platform: docking, QSAR, pharmacophore design, homology modeling | Comprehensive drug discovery workflows, method development, academic evaluation | [120] |

| Molegro Virtual Docker | Commercial | Docking platform with novel optimization algorithm and user-friendly interface | Protein–ligand docking, virtual screening with high usability | [121] |

| MSU SLIDE | Commercial and Academic | Manages large binding-site templates with multi-stage indexing; ranks ligands by steric complementarity | Efficient virtual screening of large libraries with binding-site template matching | [122] |

| MzDOCK | Open-source | GUI-based docking tool; simplifies workflows and improves reproducibility | User-friendly option for beginners and teaching | [123] |

| Qsite | Commercial | QM/MM multi-scale tool combining quantum and molecular mechanics to predict configurations, energetics, and electronic structures | Accurate modeling of reactive systems, catalytic sites, and mechanistic studies | [124] |

| rDOCK | Open-source | Docking of small molecules to proteins and nucleic acids | Virtual screening, binding mode prediction, protein and nucleic acid targets | [125] |

| SuperStar | Commercial | Generates protein interaction maps from crystallographic data; predicts “hot-spots” for favorable interactions | Binding site analysis, hot-spot prediction, and molecular design support | [126] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Österreichische Pharmazeutische Gesellschaft. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

García-Díaz, J.M.; Garibaldi-Ríos, A.F.; Gallegos-Arreola, M.P.; Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez, F.; Delgado-Saucedo, J.I.; Martínez-Velázquez, M.; Puebla-Pérez, A.M. Computational Workflow for Chemical Compound Analysis: From Structure Generation to Molecular Docking. Sci. Pharm. 2026, 94, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/scipharm94010009

García-Díaz JM, Garibaldi-Ríos AF, Gallegos-Arreola MP, Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez F, Delgado-Saucedo JI, Martínez-Velázquez M, Puebla-Pérez AM. Computational Workflow for Chemical Compound Analysis: From Structure Generation to Molecular Docking. Scientia Pharmaceutica. 2026; 94(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/scipharm94010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcía-Díaz, Jesus Magdiel, Asbiel Felipe Garibaldi-Ríos, Martha Patricia Gallegos-Arreola, Filiberto Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez, Jorge Iván Delgado-Saucedo, Moisés Martínez-Velázquez, and Ana María Puebla-Pérez. 2026. "Computational Workflow for Chemical Compound Analysis: From Structure Generation to Molecular Docking" Scientia Pharmaceutica 94, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/scipharm94010009

APA StyleGarcía-Díaz, J. M., Garibaldi-Ríos, A. F., Gallegos-Arreola, M. P., Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez, F., Delgado-Saucedo, J. I., Martínez-Velázquez, M., & Puebla-Pérez, A. M. (2026). Computational Workflow for Chemical Compound Analysis: From Structure Generation to Molecular Docking. Scientia Pharmaceutica, 94(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/scipharm94010009