Abstract

This paper reviews Artificial Intelligence techniques for distributed energy management, focusing on integrating machine learning, reinforcement learning, and multi-agent systems within IoT-Edge-Cloud architectures. As energy infrastructures become increasingly decentralized and heterogeneous, AI must operate under strict latency, privacy, and resource constraints while remaining transparent and auditable. The study examines predictive models ranging from statistical time series approaches to machine learning regressors and deep neural architectures, assessing their suitability for embedded deployment and federated learning. Optimization methods—including heuristic strategies, metaheuristics, model predictive control, and reinforcement learning—are analyzed in terms of computational feasibility and real-time responsiveness. Explainability is treated as a fundamental requirement, supported by model-agnostic techniques that enable trust, regulatory compliance, and interpretable coordination in multi-agent environments. The review synthesizes advances in MARL for decentralized control, communication protocols enabling interoperability, and hardware-aware design for low-power edge devices. Benchmarking guidelines and key performance indicators are introduced to evaluate accuracy, latency, robustness, and transparency across distributed deployments. Key challenges remain in stabilizing explanations for RL policies, balancing model complexity with latency budgets, and ensuring scalable, privacy-preserving learning under non-stationary conditions. The paper concludes by outlining a conceptual framework for explainable, distributed energy intelligence and identifying research opportunities to build resilient, transparent smart energy ecosystems.

1. Introduction

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has become a central enabler of modern energy management systems, particularly within smart grids, intelligent buildings, and IoT-Edge-Cloud infrastructures. The increasing availability of sensor data, together with the deployment of heterogeneous IoT devices and embedded controllers, has accelerated the use of Machine Learning (ML), Deep Learning (DL), Reinforcement Learning (RL), and Multi-Agent Systems (MAS) for forecasting, optimization, and autonomous control [1]. Distributed computation across edge platforms enables low-latency inference and real-time adaptation to rapidly changing operating conditions, making such architectures attractive for applications where responsiveness and resource efficiency are critical.

AI-driven controllers are being incorporated into Building Energy Management Systems (BEMSs) and microgrid operations. RL algorithms—ranging from tabular methods to advanced deep RL architectures—have demonstrated the capacity to learn optimal strategies for HVAC control, demand response, and renewable integration [2,3]. In parallel, MAS frameworks enable distributed coordination, allowing autonomous agents to negotiate actions related to consumption, generation, and storage under uncertainty and heterogeneous objectives [4]. These decentralized approaches are particularly beneficial in bandwidth-limited IoT environments, where centralized control may hinder scalability.

However, the rapid scalability of these technologies faces a critical barrier: the increasing complexity and opacity of Artificial Intelligence models. While Deep Learning and Reinforcement Learning (RL) offer superior performance in handling non-linear energy patterns, they often function as “black boxes,” making their internal logic inaccessible to human operators [5]. This lack of transparency is a major bottleneck for deployment in critical energy infrastructure, where accountability, safety, and regulatory governance are paramount [6]. Stakeholders and grid operators are often reluctant to trust automated decisions—such as load shedding or battery dispatch—if the underlying reasoning cannot be audited or explained [7]. Consequently, Explainable AI (XAI) has transitioned from a theoretical preference to an operational necessity, essential for ensuring compliance and fostering trust in automated decision-making [8].

Furthermore, the centralization of these AI models creates significant technical inefficiencies. As the number of IoT devices increases, transmitting raw high-frequency telemetry to a central cloud induces latency bottlenecks and network congestion that jeopardize real-time stability [9]. Traditional centralized optimization methods struggle to handle the computational overhead and communication delays inherent in large-scale, geographically dispersed grids [10,11]. Therefore, shifting intelligence to the Edge is not merely an architectural choice but a requirement to maintain responsiveness and data privacy [12]. Despite this, existing surveys typically focus on individual aspects such as prediction models, optimization strategies, or explainability in isolation, without providing an integrated perspective on how XAI must operate within the resource constraints of distributed IoT-Edge-Cloud architectures.

In response to these open challenges, this paper provides a comprehensive state of the art review of AI and MAS methods for energy prediction and optimization across IoT-Edge-Cloud environments, together with an analysis of explainability techniques relevant to these domains. The contributions of this work are fourfold: (i) a structured synthesis of statistical, ML, DL, heuristic, and RL approaches for energy forecasting and optimization; (ii) an examination of MAS methodologies for distributed decision-making in buildings, microgrids, and smart energy networks; (iii) an analysis of explainability methods applicable to forecasting and real-time control; and (iv) the proposal of a conceptual framework integrating AI, MAS, XAI, and distributed architectures to support scalable, interpretable, and resource-efficient energy management. The review also identifies key research gaps and outlines future directions, including federated learning approaches, resilient RL policies, and techniques for achieving end-to-end explainability in distributed settings.

The remainder of this article is structured to guide the reader progressively from foundational concepts to advanced methodological considerations. Section 2 outlines the fundamental principles underlying distributed energy systems, multi-agent coordination mechanisms, explainable AI methods, and the enabling IoT-Edge-Cloud infrastructures that support modern energy analytics. Building on this foundation, Section 3 examines the state of the art in energy forecasting, optimization and control, MAS-based decision-making, and the datasets and evaluation metrics commonly employed in the literature. Section 4 then presents the proposed explainable and distributed framework, articulating its design objectives, architectural components, and integration strategy. Section 5 offers a broader discussion of the trade-offs, practical limitations, and open research challenges that emerge from current developments. Finally, Section 6 summarizes the key insights of the study and highlights promising directions for future research.

2. Fundamentals and Context

This section provides the theoretical background necessary to understand the architectural, computational and methodological foundations of modern energy management systems. It introduces the evolution from centralized to distributed paradigms, the role of multi-agent systems, communication technologies, and the increasing relevance of Edge AI infrastructures.

2.1. Evolution from Centralized to Distributed Architectures

The transition from traditional centralized EMS/BMS deployments toward distributed and hierarchical IoT-Edge-Cloud architectures is driven by the need for scalability, resilience, and reduced latency in modern energy systems. This subsection examines the characteristics, advantages, and limitations of each paradigm.

2.1.1. Centralized EMS/BMS Systems

Centralized Energy Management Systems (EMS) and Building Management Systems (BMS) have historically used a clear hierarchy. In these systems, one coordinator gathers data from many nodes, processes it, and sends out commands to optimize energy use. Access to network-wide information enables these systems to maintain an overview and coordinate actions, thereby improving efficiency [13]. Placing all computational resources in a central location also allows complex optimization without the limits of distributed hardware. While these traits shaped early energy management, new challenges have emerged as systems have grown more complex.

However, several technical and operational drawbacks have become evident as infrastructures scale. As the number of controlled devices or subsystems increases, processing demands at the central controller scale sharply, often creating bottlenecks that hinder real-time responsiveness [14]. Continuous transmission of large volumes of sensor readings and operational metrics to a single hub introduces significant communication overhead. Any delay in data transfer or command dissemination subsequently propagates throughout the entire network [13]. Centralization also creates a single point of failure: if the primary controller fails or is subject to cyberattacks, the entire infrastructure may be disrupted. Privacy and security concerns further intensify this issue, as a centralized data repository becomes an attractive target for malicious actors. Mitigation strategies—redundancy, cybersecurity hardening, and backup infrastructures—add complexity without eliminating fundamental vulnerabilities [11].

Centralized EMS/BMS architectures work well where coordination is needed or where local autonomy risks creating resource conflicts. For instance, pre-computed load-balancing or charging schedules can be applied to all participants, which is useful for predictable demand or strict industrial rules [15]. However, as infrastructure adds a range of assets—such as renewables with variable output, storage with different charge-discharge cycles, and diverse loads—scalability issues become more apparent. This shift opens the door to distributed and hybrid models.

From an algorithmic standpoint, centralized control enables the use of advanced methods such as Deep Q-Networks (DQN), Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO), or hybrid schemes combining reinforcement learning with model predictive control, all of which rely on continuous access to a global state representation. While manageable in simplified contexts, maintaining an accurate global view becomes challenging in distributed environments with intermittent connectivity or rapidly changing dynamics. These challenges motivate the development of architectures that better accommodate decentralized information.

Electric vehicle (EV) charging networks highlight these issues. Centralized scheduling optimizes system metrics but struggles with local demand spikes, such as many arrivals at a single station. Scalability is challenged in citywide smart grids powered by renewables that vary over time. External factors—such as weather-driven solar changes or unpredictable human activity—can quickly render preset schedules ineffective [11]. Relying on distant computation slows responses, while local decision-making architectures respond faster, showing the need for new control approaches.

Hybrid models address these issues by allowing local agents to handle low-level decisions while a central controller manages strategy [15]. This setup reduces communication and maintains coordination. But as infrastructures integrate more distributed energy resources (DERs), microgrids, and IoT devices, it becomes harder for a single controller to keep systems efficient and resilient. This diversity fuels interest in multi-agent reinforcement learning, since centralized models now struggle to meet modern demands.

Despite their drawbacks, centralized EMS/BMS systems remain common because organizations already have the necessary infrastructure and are accustomed to how these controls work. Many are slow to adopt new systems unless the short-term benefits are clear, even if they know about the issues with scaling and the risk of failure.

2.1.2. Distributed IoT, Edge, Cloud Paradigms

Distributed IoT-Edge-Cloud architectures represent a structural departure from traditional centralized EMS/BMS systems, redistributing computation and decision-making across multiple layers. This subsection outlines their operational principles, benefits, and challenges.

Transitioning from the centralized frameworks described previously to distributed IoT-Edge-Cloud architectures introduces structural changes that reshape energy management strategies. A defining feature of these paradigms is the relocation of computational tasks closer to the point of data generation, with edge devices performing inference and preliminary analytics before selectively forwarding information to cloud systems. This distribution mitigates latency by reducing dependency on distant processing resources [9]. Instead of saturating communication channels with raw sensor readings, preprocessing at the edge ensures that only relevant or aggregated data traverse network links, thereby decreasing uplink load and reducing bandwidth consumption [12].

At an operational level, this architectural shift supports responsiveness in applications where reaction time directly impacts system performance. For instance, in environmental monitoring systems integrated with IoT protocols such as LoRaWAN and MQTT, placing computation at the edge accelerates object detection and anomaly identification without waiting for round-trip delays to a remote server. These benefits become increasingly important in systems experiencing fluctuating loads or variable network conditions. By balancing task allocation among local devices, intermediary edge nodes, and cloud servers, energy optimization can adapt dynamically to both computational constraints and operational demands [16].

A key architectural element is the intermediate processing tier (edge nodes), which enables bidirectional data exchange between IoT devices and cloud infrastructure [12]. This configuration reduces transmission volumes while improving scalability through distributed control logic. Edge nodes can execute localized machine learning tasks independently; compressed neural networks and federated learning are notable strategies in this context. Federated learning, in particular, supports privacy preservation by keeping raw datasets local while still enabling global model improvement—highly relevant in residential energy optimization or industrial settings with strict data protection requirements.

From a scientific perspective, the edge–cloud continuum introduces flexibility in computational placement. Tasks with stringent real-time requirements (e.g., critical load shedding) remain at the edge layer, whereas computationally intensive but latency-insensitive operations (e.g., long-term demand forecasting) are offloaded to the cloud. This division leverages each layer’s strengths—immediate reaction capabilities at the edge combined with deep analytics in the cloud—resulting in hybrid workflows that outperform monolithic models under variable conditions.

Despite these advantages, engineering trade-offs persist. IoT nodes typically operate under tight energy and hardware constraints; prolonged computation can strain battery life or thermal budgets. Future iterations may benefit from model compression techniques that reduce computation time while preserving predictive accuracy [17]. Experimental results show that compressed architectures executed on low-power processors can sustain adequate inference performance while prolonging device uptime.

Another core advantage of distributed paradigms is their resilience to single points of failure. If one edge node fails, others may compensate locally, or tasks may be rerouted to neighboring devices until cloud resources can provide additional support. This redundancy contrasts with centralized EMS/BMS setups, where a single outage compromises global oversight. Furthermore, local autonomy enables continued operation under partial network loss, as decisions can still rely on cached data and learned policies.

The introduction of multi-agent frameworks further enhances coordination among decentralized units by embedding decision-making capabilities directly into agents situated at different network layers [18]. Integration into smart grids adds an additional dimension: distributed IoT-Edge-Cloud systems can correlate inputs from sensors monitoring temperature, humidity, luminosity, weather patterns, and occupancy metrics in near real-time. Edge nodes can then adjust loads based on immediate conditions while maintaining alignment with overarching grid strategies developed in the cloud. Predictive models trained on historical datasets refine scheduling efficiency over longer horizons but depend on rapid edge-level feedback to remain effective.

These layered architectures also support incremental scalability. New IoT devices can attach at appropriate layers without requiring significant reconstruction of central systems. Edge-based designs promote modular expansion because computational dependencies are not rigidly tied to a single physical location. This is exemplified by hybrid ensemble optimization systems that distribute multiple algorithms across processing sites [16]. While such systems require careful orchestration to prevent conflicting actions among nodes, they offer greater adaptability across diverse use cases.

However, persistent challenges remain. Synchronizing state representations between edge and cloud layers requires robust consistency protocols; asynchronous updates may cause divergences that degrade decision quality over time [17]. Variations in sampling rates among heterogeneous sensors—common in mixed-vendor deployments—require mechanisms to harmonize incoming streams before feeding them into distributed models. Failure to address such disparities can introduce bias or instability in predictions.

The interplay between local computation efficiency and global coordination mirrors emerging studies that blend reinforcement learning with offline optimization for scalable residential energy management. In these settings, agents learn contextually optimal strategies through localized experience while preserving system-wide alignment through periodic synchronization with centrally maintained global policies. Here, communication timing becomes as critical as algorithm selection.

Ultimately, deploying distributed IoT-Edge-Cloud infrastructures reshapes AI-driven energy management; responsiveness is enhanced by moving intelligence closer to action points; resources are conserved through layered processing; privacy is preserved thanks to federated learning; decentralized coordination is enabled by hybrid control loops; and overall resilience is improved through the decentralization of decision authority. The scientific challenge ahead lies in harmonizing these components so that explainability, accuracy, stability, and scalability remain balanced under fluctuating environmental and network dynamics.

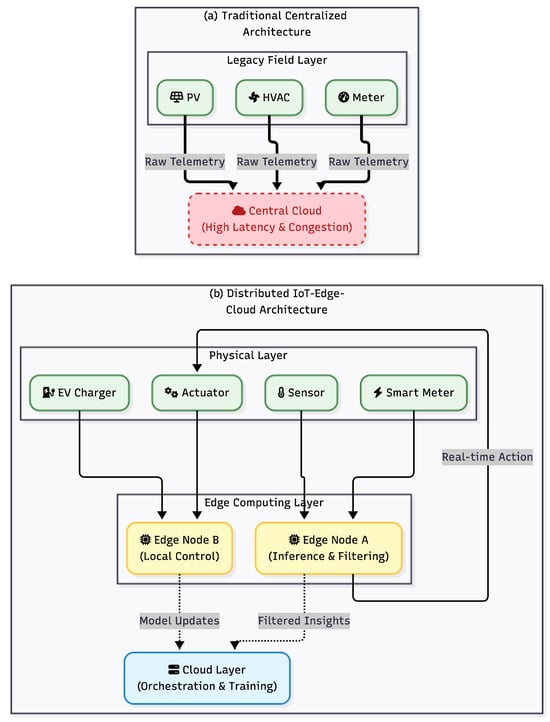

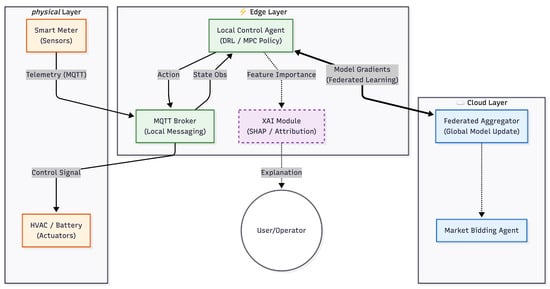

To visualize these structural differences, Figure 1 contrasts the traditional centralized topology with the distributed IoT-Edge-Cloud framework, highlighting the redirection of data flows for local processing.

Figure 1.

Evolution of energy management architectures. (a) Traditional Centralized Architecture: Raw data travels to the cloud, causing potential latency and bottlenecks. (b) Distributed IoT-Edge-Cloud Architecture: The InTec approach [9] introduces an intermediate Edge layer for local inference and filtering, reducing bandwidth congestion and enabling real-time response [12].

2.2. Multi-Agent Systems for Energy Management

This subsection outlines the role of multi-agent systems (MAS) in distributed energy management and introduces key coordination mechanisms used to align local agent decisions with system-wide objectives.

Agent Coordination Mechanisms

Coordination among agents in distributed energy management systems requires balancing local objectives with global operational targets. Agents may represent diverse entities such as EV charging stations, microgrid controllers, shared storage operators, or building subsystems. The principal challenge arises from the need to adapt decisions under partial information, fluctuating environmental conditions, and heterogeneous device capabilities.

Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning (MADRL) has become a prominent approach to addressing this complexity, enabling agents to learn optimal behaviors without relying on explicit centralized environmental models. Model-free DRL is particularly relevant in non-linear and analytically intractable scenarios, where agents iteratively refine load-balancing or charge/discharge strategies through repeated interactions with their environment.

Effective coordination demands structured negotiation between agents whose goals may conflict. Pareto front optimization is frequently employed to scalarize multiple objectives using operator-defined weights, enabling solutions that balance individual agent preferences with global performance requirements [11]. This prevents disproportionate prioritization of a single objective, such as cost minimization, at the expense of user satisfaction or grid stability.

In EV charger-sharing networks, coordination can also be achieved through auction-based mechanisms embedded within MADRL frameworks. Agents adjust bids based on historical patterns and market forecasts, facilitating resource allocation that responds to real-time capacity constraints while maintaining economic efficiency. Predictive analytics reinforce these auction mechanisms by enabling the anticipation of demand spikes or supply shortages. Dynamic pricing integrated into agent policies further incentivizes behavior that aligns local actions with system-wide benefit under changing market conditions [19]. Coordination in this setting emerges from distributed interactions rather than from any single controlling node.

Shared storage assets introduce additional coordination challenges. Conflicts between Integrated Energy Station (IES) operators regarding access to common buffers can lead to inefficiencies unless cooperative scheduling mechanisms are implemented. Decentralized frameworks allow agents to negotiate usage based on mutually agreed priorities while retaining autonomy within their own operational zones. Traditional distributed algorithms often struggle to account for nuanced energy flow patterns across interconnected resources. MADRL approaches augmented with expert demonstrations address this by guiding learning toward strategies that satisfy hard constraints such as energy balance and user comfort. The Imitation–Augmented Actor–Critic (IAAC) method integrates expert trajectories with attention mechanisms, enabling the model to concentrate its learning on the most relevant state–action subspaces, mitigating overestimation issues common in algorithms such as MADDPG when state–action spaces are large [20].

Within smart building environments, coordination involves synchronizing multiple controllable loads—HVAC systems, lighting, and other actuators—through adaptive distributed control [21]. Multi-agent RL must reconcile disparate operational rhythms while responding to changes in occupancy and weather. DRL-driven scheduling can blend predictive models with real-time sensing to stabilize consumption without compromising occupant comfort.

Scalability remains a central obstacle for multi-agent coordination. As agent populations grow, communication overhead increases unless information exchange protocols are optimized. Cross-chain blockchain schemes have been proposed to coordinate local and global markets within EV charging infrastructures, distributing record-keeping to reduce bottlenecks while maintaining transparency and security. Such schemes support trusted sharing of load states among geographically dispersed nodes without relying on centralized intermediaries.

Policy complexity also affects scalability. Lightweight policy representations enable faster computation on resource-constrained edge devices while remaining compatible with global strategies learned at higher tiers. Balancing local autonomy with periodic synchronization—often through federated learning updates—helps maintain alignment across heterogeneous hardware environments. Nevertheless, pure decentralization risks strategic divergence if communication delays or failures occur. Incorporating fallback consensus protocols ensures coherent behavior under degraded network conditions.

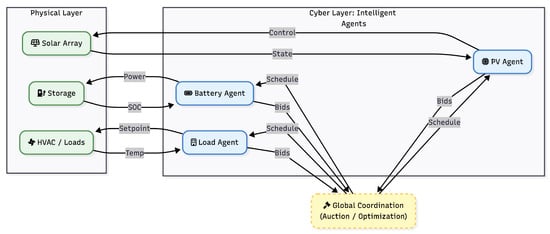

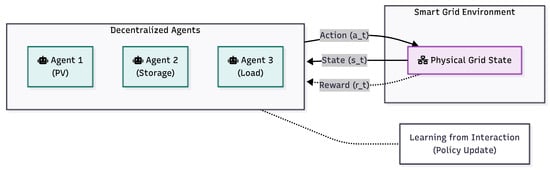

The interaction between these autonomous entities requires a structured hierarchy to maintain system stability. Figure 2 illustrates the separation between the cyber layer (agents) and the physical layer, demonstrating how local bids are reconciled by a global coordination mechanism.

Figure 2.

Simplified hierarchical coordination loop in Multi-Agent Systems. The architecture decouples the Physical Layer (assets) from the Cyber Layer (agents). Local agents process state data (e.g., SOC, temperature) and submit bids to a global Coordinator. This mechanism resolves conflicts via auction or Pareto optimization before executing control actions [19,22,23].

2.3. Communication Protocols and Deployment

This subsection introduces the communication mechanisms that enable interoperability and efficient data exchange across IoT, edge, and cloud layers, focusing first on lightweight messaging protocols widely adopted in energy management systems.

2.3.1. MQTT for Lightweight Messaging

MQTT has emerged as a preferred communication protocol in many IoT-Edge-Cloud energy management deployments due to its suitability for resource-constrained environments and its publish–subscribe architecture, which minimizes unnecessary message traffic. Its inherently lightweight design reduces packet size, a critical advantage in scenarios where devices operate over low-bandwidth or wireless links such as Zigbee or LoRa [24]. In energy-optimization systems, this efficiency directly affects power consumption at both transmitting and receiving nodes, since reduced processing and shorter transmission times translate into lower energy expenditure. When combined with edge-based decision-making, MQTT provides a fast communication channel between distributed agents without introducing additional latency that could hinder real-time control loops [9].

The decoupling between publishers and subscribers enables flexible scaling as device populations grow, without restructuring communication patterns. For example, an edge node monitoring aggregated load data can publish updates simultaneously to multiple cloud analytics services while pushing alerts to local actuators. Message routing occurs through the broker, which can be located close to the edge tier, thereby reducing round-trip delays. This becomes essential when supporting high-frequency data streams from smart meters or photovoltaic inverters [25], where timely dissemination enables proactive adjustments to maintain grid stability.

In multi-agent reinforcement learning frameworks, MQTT enables asynchronous yet reliable inter-agent communication, preventing congestion that can arise in naïve peer-to-peer architectures. Its Quality of Service (QoS) levels allow for fine-grained tuning between delivery guarantees and bandwidth consumption. Low QoS levels can be applied to non-critical telemetry, while higher levels can be reserved for control directives where lost messages may violate operational constraints [26]. Such selective reliability is valuable in integrated energy stations or shared storage systems where hard constraints must be maintained. Although the broker’s central role introduces a potential single point of failure, redundancy through clustered brokers or distributed deployments can mitigate this risk. Local brokers within microgrids can also sustain internal coordination during WAN interruptions, with devices resynchronizing once external connectivity is restored.

MQTT integration across heterogeneous devices—from MCU-based smart plugs to Raspberry Pi gateways—is facilitated by its minimal implementation overhead, with many IoT SDKs supporting it natively. In building energy systems, MQTT-enabled sensors can coexist with mobile applications subscribed to the same topics, enabling edge nodes and AI-driven controllers to reconcile manual overrides with automated strategies in real time. Hierarchical topic structures further support segmentation by zone, device type, or operational state, allowing AI modules to selectively subscribe to relevant data rather than ingest full streams. This targeted subscription reduces the memory footprint at consuming agents, which is important when models must run on RAM-limited hardware.

Security considerations remain essential: MQTT does not enforce encryption or authentication by default. Deployments typically wrap payloads within TLS-secured channels and introduce token-based access control at the broker. For critical infrastructures such as smart grids or renewable energy communities [25], these layers are vital to prevent spoofing attacks or message tampering. Resource-constrained edge devices may require lightweight cryptographic routines to maintain responsiveness.

MQTT’s temporal characteristics align well with demand-response strategies. Short latencies between detecting grid frequency deviations and issuing actuation commands help stabilize the supply-demand balance before deviations accumulate. Adaptive publishing intervals support dynamic trade-offs between responsiveness and network load—higher frequencies during volatility, slower updates when conditions remain stable [27]. Predictive-maintenance routines likewise benefit from prompt anomaly reporting, as alerts regarding inverter inefficiencies or unusual appliance usage can reach diagnostic modules without delay.

From a deployment standpoint, MQTT supports bridging across diverse transport layers, acting as a mediator between wireless sensor networks (e.g., LoRaWAN) and IP-based cloud analytics platforms [24]. Gateways translate incoming frames into MQTT topics consumable by downstream decision engines, while preserving semantic labeling, which is important for explainable AI modules [6]. Ensuring alignment between messaging structures and interpretable model inputs maintains transparency and traceability across the pipeline.

In federated learning workflows for distributed optimization, MQTT enables efficient transmission of model updates rather than raw datasets [17]. This conserves bandwidth while preserving privacy in residential and industrial settings. Federated updates, being small in size, fit naturally within MQTT’s packet structure, and retained messages ensure that late-joining nodes receive the latest model parameters immediately. This highlights how the selection of communication protocols affects not only delivery speed but also the efficiency of collaborative learning across heterogeneous electrical subsystems coordinated via multi-agent principles [20].

2.3.2. BACnet and Building Automation Interoperability

BACnet, or Building Automation and Control Networks, was conceived to address longstanding interoperability limitations in early building automation systems. Before its development, many deployments relied on proprietary communication protocols, resulting in siloed infrastructures where controllers, sensors, and actuators from different vendors could not interoperate. Introduced in 1987, BACnet provided a standardized protocol defining common object types and services, enabling heterogeneous devices to exchange information without vendor-specific translation layers. This shared semantic model extends beyond HVAC to include lighting, access control, fire safety, and energy metering, supporting multi-vendor ecosystems and facilitating long-term scalability.

Unlike lightweight IoT messaging protocols such as MQTT, which focus primarily on efficient data transfer, BACnet incorporates richer semantic descriptions of device capabilities. This allows receiving systems to not only read data but also to interpret and act on it consistently. In modern IoT-Edge-Cloud environments, gateways often bridge BACnet’s object-oriented structure with topic-based or REST-style interfaces, ensuring compatibility with cloud analytics or edge-deployed AI modules.

Adopting BACnet in buildings with legacy proprietary systems often requires structured mapping between older control points and standardized BACnet objects. Although the protocol enforces interoperability, optional features and vendor-specific extensions still necessitate rigorous commissioning and occasional custom bindings. Nevertheless, its openness enables incremental upgrades: new devices can announce their capabilities via standardized descriptors, allowing AI-driven energy management modules to automatically incorporate them into optimization routines.

As BACnet implementations increasingly run over IP networks, cybersecurity becomes critical. The original protocol assumed physically isolated environments and lacked native cryptographic features. Contemporary deployments typically add TLS, VPN tunneling, or token-based authentication, especially when BACnet shares infrastructure with IoT protocols. Harmonizing security mechanisms across both ecosystems prevents cross-protocol vulnerabilities, an important consideration for smart grids and large commercial facilities.

Interoperability plays a key role in how energy management algorithms interact with physical assets. An edge-level predictive HVAC controller may issue setpoint commands through MQTT while relying on occupancy or temperature data retrieved from BACnet-only devices. Gateways translate between these models to ensure that multi-agent control strategies receive coherent and timely state information. Such coordination is particularly important when aligning actions across HVAC, lighting, and ventilation systems under stringent latency constraints.

From an operational perspective, BACnet’s unified communication layer mitigates vendor lock-in and reduces long-term system costs by allowing for component replacement or expansion without architectural overhauls. When combined with explainable AI models that leverage historical logs encoded in standardized BACnet objects, operators gain transparent, traceable insights into the reasoning behind automated control actions.

Maintaining consistent state representations across heterogeneous protocols is essential in hybrid IoT-Edge-Cloud deployments. When optimization engines rely on BACnet-derived measurements while issuing control commands through MQTT, misalignment between protocol layers can degrade performance. BACnet’s event-notification mechanisms help mitigate such mismatches by pushing state changes immediately rather than relying solely on fixed polling cycles [25]. In emerging environments such as IoT-rich smart grids and microgrids, middleware platforms increasingly reconcile syntactic and semantic differences across devices and communication schemes, ensuring that AI-driven and multi-agent control frameworks operate over a unified and coherent conceptual model [28].

Ensuring interoperability between these legacy protocols and modern cloud services is critical. Figure 3 depicts the data workflow through a Smart Gateway, which maps semantic BACnet objects to lightweight MQTT topics for upstream analytics.

Figure 3.

Interoperability workflow in hybrid environments. A Smart Gateway bridges the gap described in Section 2.3.2, translating semantic BACnet objects from legacy equipment into lightweight MQTT topics [24,29], enabling efficient integration of legacy OT domains with modern IT optimization engines.

2.3.3. Semantic Interoperability and Modeling

While protocols like MQTT and BACnet facilitate data transport, they function primarily at the syntactic level. A critical limitation in raw MQTT deployments is the lack of inherent context; a topic named building1/sensor/temp carries a payload, but without a semantic layer, consuming agents cannot distinguish whether this represents an indoor ambient temperature, a boiler return temperature, or a setpoint [30]. To achieve the “Interoperability” required for scalable Multi-Agent Systems, the framework must incorporate semantic modeling standards such as Brick Schema or Project Haystack.

Semantic layers provide a standardized ontology that maps low-level I/O points to high-level physical concepts and relationships (e.g., “Sensor A isPointOf VAV Box B feeds Room C”). This abstraction is essential for MAS scalability; it allows an agent trained on one building’s dataset to transfer its policy to another building by mapping inputs via the semantic graph rather than hard-coded tag names [31]. Furthermore, semantic standardization is a prerequisite for meaningful Explainable AI. As noted in Section 5.3, explaining a decision based on raw tags is opaque to facility managers; linking those tags to semantic definitions enables natural language explanations (e.g., “HVAC reduced because Zone North occupancy is zero”) [6,32].

2.4. Edge AI Platforms and Hardware

As energy management architectures shift toward distributed IoT-Edge-Cloud paradigms, the capabilities and constraints of edge hardware become central to system performance. This section examines the role of embedded platforms and specialized edge devices in supporting AI-driven optimization under strict power, latency, and memory limitations.

Low-Power Embedded Systems

Energy-aware AI deployments are shaped by hardware capabilities and constraints. In low-power embedded contexts, especially with microcontrollers, design constraints are explicit: operating at milliwatt power levels, kilobyte memory, and low clock speeds. These limits require algorithmic strategies distinct from those for edge servers or cloud platforms. Tiny Machine Learning (TinyML) enables ML inference directly on microcontrollers, without constant external computation. Model pruning, quantization, and compression enable local deployment of deep neural networks with only a few milliwatts of power. This is crucial for battery-powered IoT devices that must operate autonomously for long periods.

Quantization reduces numerical precision to 8-bit fixed-point formats, lowering storage requirements and speeding up multiply-accumulate operations. Similarly, pruning removes redundant parameters, which maintains accuracy while reducing inference cost. These methods work in tandem with hardware-specific optimizations in lightweight ML libraries that provide efficient kernels for convolutions, activations, and other operations tailored to microcontroller instruction sets. Consequently, portability may sometimes be sacrificed for optimal hardware efficiency.

Low-latency response is often as important as energy efficiency. In real-time control loops—such as adjusting HVAC output in response to occupancy—local inference avoids cloud-offload delays that would hinder responsiveness [33]. This advantage also reduces dependence on persistent connectivity; devices remain functional during network disruptions. Within IoT-Edge-Cloud hierarchies [9], low-power embedded systems naturally occupy the “thing” tier. They perform preliminary filtering or event detection before invoking local neural inference, minimizing upstream bandwidth usage and distributing computational load effectively across large device populations.

Integrating DRL or MARL at the microcontroller level remains challenging due to the high training time requirements [3]. While on-device training is generally infeasible, running compressed policies locally is achievable. Knowledge distillation enables small student models to inherit decision quality from large teacher networks. Periodic policy updates from edge or cloud servers can be distributed via lightweight protocols such as MQTT, enabling adaptive behavior without overwhelming constrained devices.

Hardware developments increasingly support embedded ML workloads. Modern MCUs include DSP extensions or AI accelerators designed for SIMD operations, enhancing throughput per watt for convolutional workloads. Memory architectures remain a limiting factor: constrained SRAM and slower flash storage require model designs that minimize intermediate activations. Techniques such as operator fusion reduce memory usage and lower instruction counts. Shallow but wide architectures often outperform deeper networks under strict latency and memory constraints.

Security concerns are similar to higher tiers but complicated by a few resources. Cryptographic routines use cycles and memory, so lightweight ciphers secure device-gateway communication without harming responsiveness. Thermal concerns arise in sealed enclosures; repeated short inference bursts can raise temperatures. Event-driven processing reduces this risk and extends battery life.

Low-power embedded systems broaden the reach of AI-driven energy optimization into remote or infrastructure-poor environments [12]. Examples include solar-powered agricultural pumps performing local anomaly detection (spotting unusual behavior), isolated microgrids fine-tuning inverter settings via occasional satellite-updated control signals, or campus lighting systems maintaining context-aware dimming during WAN (wide area network) outages. Interfacing these embedded nodes with upstream controllers requires careful tuning of synchronization frequency (how often data or models are updated). Infrequent updates risk model drift (loss of accuracy over time) as environmental patterns evolve, while excessive synchronization reduces the bandwidth savings gained by local inference. Federated learning (models trained across many devices without centralizing data) offers a compromise: devices transmit gradient updates (changes in the model) or compressed weight deltas (differences from previous model versions) rather than raw telemetry [16], aligning distributed models efficiently.

Ultimately, low-power embedded systems serve both as endpoint actuators (devices that take physical action) and as localized intelligence engines (processors that make decisions) within distributed AI infrastructures for energy management. Their importance will continue to grow as chip-level innovations and model compression techniques enable richer inference capabilities within strict power envelopes. By placing computation close to energy-relevant phenomena, these devices provide rapid responses under tight constraints while forwarding concise contextual information upstream, embodying architectural principles that link IoT “things” to edge nodes and cloud-level optimization engines.

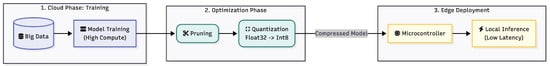

Deploying complex models on such constrained hardware requires a specialized workflow. Figure 4 outlines the typical TinyML deployment pipeline, from cloud-based training to the optimization steps (pruning and quantization) necessary for efficient edge inference.

Figure 4.

The TinyML deployment pipeline for constrained hardware. To address power and memory limits, models undergo quantization and pruning [33] before deployment on microcontrollers. This flow enables low-latency local inference [34] without continuous cloud dependency.

3. State of the Art in AI for Energy Prediction and Optimization

Recent advances in Artificial Intelligence have significantly expanded the range of methodologies available for forecasting, optimization, and control within modern energy systems. Building on the architectural and technological foundations discussed in the previous section, current research spans statistical models, machine learning regression techniques, deep learning architectures, and reinforcement learning strategies operating across distributed IoT, Edge, and Cloud environments. These approaches differ markedly in terms of interpretability, computational demands, data requirements, and suitability for real-time deployment. This section reviews the principal families of methods used in energy prediction and optimization, highlighting their capabilities, limitations, and relevance within emerging distributed and explainable energy management frameworks.

3.1. Energy Prediction Models

Imagine the benefits of accurate energy forecasting—it is central to the optimization and control strategies throughout this work. Prediction models span a wide methodological spectrum, from classical statistical formulations to modern learning-based techniques. To clarify the progression, this section examines the main families of approaches. It begins with statistical time-series methods, which remain essential for interpretability and strong performance under well-characterized temporal structures.

3.1.1. Statistical Time Series Approaches

Statistical time series approaches in energy prediction continue to serve as foundational tools even in increasingly AI-driven contexts. Unlike neural network architectures or complex ensemble models, these methods build forecasts directly on identifiable temporal structures inherent in historical data. Techniques such as autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA), seasonal decomposition of time series (STL), and exponential smoothing focus on modeling trend, seasonality, and noise components, enabling explicit interpretation of patterns across different horizons. This emphasis on signal decomposition aligns with the broader pursuit of transparency, as operators can trace outputs to well-defined mathematical constructs rather than opaque learned representations.

An important refinement to classical frameworks involves mode decomposition, in which aggregated consumption data is partitioned into interpretable subsequences that capture distinct operational behaviors—daily cyclic variations, abrupt demand spikes, or room-level activity patterns. Such segmentation provides a granular view of how consumption evolves across spaces or microgrid assets. Each subsequence may correspond to a specific scenario, for instance, HVAC use during peak hours versus baseline nighttime loads, enabling more targeted forecasting while preserving interpretability.

This decomposition can be integrated with hybrid predictive pipelines in which deterministic components feed traditional statistical models, while residual or irregular patterns are passed to non-linear learners optimized for stochastic variability. In doing so, model complexity is managed effectively: interpretable components remain in mathematical form, while high-variance elements benefit from the flexibility of AI-based adaptation. Beyond prediction, feature decomposition supports behavior inference; systematic deviations from baseline sequences may reveal shifts in occupancy routines or equipment usage. This reinforces the diagnostic value of statistical approaches within broader optimization strategies, especially when communicating results to stakeholders who require comprehensible explanations instead of abstract algorithmic outputs.

Classical time series analysis also facilitates alignment between method capability and forecast horizon. Seasonal indices extracted via STL decomposition support medium-term planning—e.g., cooling demand in climates with strong summer peaks—while ARIMA models capture short-term autocorrelation patterns suited for hour-ahead dispatch scheduling [35]. Misalignment between forecast horizon and methodological assumptions often degrades accuracy more than parameter calibration issues. Seasonal adjustment, combined with trend estimation, also enables scenario testing under hypothetical modifications, such as energy retrofits or behavioral campaigns, that affect long-term trajectories.

Despite their advantages, statistical methods face challenges under non-stationarity induced by unpredictable events, abrupt equipment changes, or sudden occupancy shifts. Rolling-window estimation mitigates such issues by updating coefficients with recent data slices, though care must be taken to avoid overfitting transient anomalies. Recent advances integrate explainable artificial intelligence principles with traditional models—for instance, combining Shapley value attribution with residual analysis to reveal which exogenous variables (e.g., weather or schedules) drive forecast fluctuations during particular intervals.

Industrial forecasting settings often employ multivariate regression extensions with exogenous predictors such as weather metrics, calendar effects, and market prices. These structures capture interactions between internal system inertia and external influences while retaining transparency through interpretable regression coefficients. Interactive effects become evident when coefficients vary across seasons or economic cycles, offering insights into the contexts in which certain interventions exert greater leverage.

In smart building applications enriched by IoT sensing arrays (Section 2.4), rolling multivariate regressions leverage high-frequency data streams without losing periodic structure. Statistical baselines derived from historical datasets serve as reference modes to flag deviations significant enough to trigger adaptive control actions. Moreover, statistical decomposition is often used as a preprocessing step in hybrid AI pipelines for UBEM tasks [36], thereby improving the efficiency of downstream neural networks by isolating deterministic patterns from stochastic residuals. This resonates with explainable composite models where transparent statistical layers complement deeper but less interpretable learners.

Integration of statistical approaches into distributed management architectures also benefits from federated learning setups [17]. Lightweight seasonal decompositions executed at local nodes can propagate parameter updates upstream without sharing raw datasets, preserving privacy while improving collective accuracy across diverse environments.

In terms of system suitability, statistical models such as ARIMA and Exponential Smoothing offer distinct advantages for edge deployment due to their low computational footprint and high interpretability. Their mathematical transparency allows operators to easily validate baseline forecasts without complex post-hoc explainability tools [37]. However, their primary limitation lies in their inability to capture complex non-linear dependencies or rapidly incorporate high-dimensional exogenous variables (e.g., occupancy images or complex weather grids) as effectively as deep learning approaches [17]. Consequently, these methods are best suited for Level 1 (Edge) deployment in microcontrollers or gateways where memory is scarce, serving as reliable fallback mechanisms when cloud connectivity is lost.

3.1.2. Machine Learning Regression Models

Regression-based machine learning models play an essential role in energy prediction pipelines, particularly when continuous-valued outputs are required, such as load forecasts, temperature estimates, or consumption profiles. In contrast to the statistical time series methods discussed in Section 3.1.1, these algorithms learn predictive mappings from potentially high-dimensional input spaces without being bound to linear relationships or stationarity assumptions.

Before analyzing each regression family in detail, Table 1 summarises the main machine learning approaches used in energy prediction, highlighting their typical data requirements, computational demands, interpretability properties, and suitability for IoT-Edge-Cloud deployments.

Table 1.

Comparison of machine learning regression models for energy prediction in IoT-Edge-Cloud environments.

Support Vector Regression (SVR) exemplifies how kernelized approaches manage non-linear dependencies between predictors and target load values [21]. By transforming inputs into higher-dimensional feature spaces and optimizing a tolerance margin around the regression function, SVR accommodates irregular patterns common in real-world energy datasets, where operational schedules or environmental conditions shift unpredictably. Selecting appropriate kernels—radial basis functions for smooth, non-linear variation or polynomial kernels for power-law tendencies—remains a key modeling decision that influences accuracy and computational cost. However, SVR’s memory footprint scales quadratically with the number of support vectors, posing challenges when processing high-frequency sensor streams typical of IoT–Edge deployments.

Decision tree regression models partition input space via threshold-based splits that often align with interpretable operational conditions. For example, a division of outdoor temperatures can separate HVAC cooling-dominant from heating-dominant regimes, with subsequent splits refining predictions based on occupancy or appliance usage data. This hierarchical partitioning enhances interpretability because each path from root to leaf reflects a sequence of intuitive conditions leading to an energy forecast. Ensemble variants such as gradient boosting regression trees iteratively correct residual errors, improving accuracy compared to single-tree solutions at the expense of transparency unless complemented by XAI tools such as SHAP or LIME [5].

Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), including multilayer perceptrons and deeper architectures, offer high expressivity by learning complex non-linear mappings end-to-end [41]. They integrate temporally lagged features with static building descriptors to represent intertwined temporal—spatial relationships in consumption data. With sufficiently large and heterogeneous training sets, ANNs can generalize across varied operational contexts. However, their opacity—especially in deep configurations—limits direct attribution without specialized interpretability layers. Methods such as partial dependence plots (PDPs) clarify how individual features influence predictions by holding other features constant [45], thereby supporting trust during deployment in sensitive infrastructure.

Hybrid modeling strategies frequently emerge in real-world smart building scenarios. Linear regression baselines serve as benchmarks against which more advanced ML regressors are evaluated [5]. Linear models remain valuable when relationships are predominantly additive and proportional; their coefficients provide straightforward sensitivity estimates for informing demand reduction policies. However, as many load datasets exhibit multimodal behavior beyond the linear scope—such as peak shifting due to tariffs or abrupt drops during equipment maintenance—the need arises to transition to more flexible learners. For example, k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) regressors estimate outputs by averaging observations most similar to current input conditions [41]. This local adaptation is well-suited when similar operational states recur, although KNN performance can degrade if environmental conditions change rapidly.

Extreme Learning Machines (ELMs) expand the range of fast regression models for energy prediction. They randomly assign hidden-layer weights, then solve for output weights in closed form. This enables rapid training suited for edge deployments with limited resources. Such models must update often. Comparative studies benchmark ELMs against SVR and Generalized Regression Neural Networks (GRNN) for short-horizon indoor temperature estimation. These studies demonstrate ELM’s robustness to changing weather patterns. This stability is valuable where models must perform reliably within control loops despite outside volatility.

Explainability overlays are increasingly used alongside ML regressors in urban building energy modeling (UBEM). Stakeholders demand not only accuracy but also clarity about the causal pathways linking policy interventions—such as insulation retrofits—to predicted savings [36]. To meet these demands, XAI techniques quantify how critical factors influence regression outcomes, thereby reducing uncertainty and helping align optimization decisions with regulatory or sustainability goals. Among these methods, QLattice regressors combine transparent symbolic modeling with predictive performance beyond that of simple parametric forms. QLattice models yield compact analytical expressions for variable interactions that can be scrutinized directly.

In IoT–Edge–In IoT-Edge-Cloud contexts, the computational footprint becomes as decisive as predictive accuracy. Deploying resource-intensive gradient-boosting models on constrained edge hardware is often impractical without compression or distillation. Knowledge distillation transfers learned behavior from complex “teacher” models into lightweight “student” models capable of low-power inference, as required for embedded systems, noted in Section 2.4. Regression modeling also aligns naturally with federated learning paradigms, where local nodes train individualized regressors on site-specific consumption data and share model updates rather than raw measurements. This preserves privacy while combining insights from diverse environments to refine global parameter sets and distribute them back to each node. Maintaining this under non-stationary conditions—such as shifting occupancy habits or evolving tariff structures—remains critical. Online learning variants update parameters incrementally as new data arrives, maintaining relevance while reducing overhead compared to full retraining. Coupled with XAI dashboards that monitor feature importance drift, operators can detect early signals of behavioral shifts that affect prediction reliability.

From a deployment view in UBEM applications [36], regression algorithm selection balances expressivity, interpretability, scalability, and resistance to temporal drift. Options range from linear models to kernel-based SVR, ensemble trees, GRNNs, KNNs, ELMs, symbolic QLattices, and deep ANNs. This breadth allows practitioners to choose predictive cores suited for AI-driven optimization in IoT-Edge-Cloud systems that require explainable decision-making.

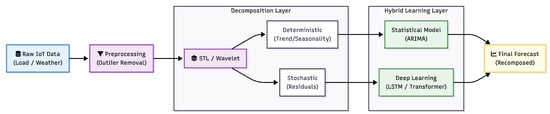

To illustrate the increasing complexity of modern forecasting pipelines, Figure 5 depicts a hybrid workflow. Here, raw IoT data is decomposed into deterministic components (handled by statistical methods) and stochastic residuals (processed by deep learning), enhancing overall accuracy as discussed in [35].

Figure 5.

A hybrid data-driven forecasting pipeline. By decomposing time series data into trend/seasonal and residual components, the system leverages the interpretability of statistical models for stable patterns while utilizing Deep Learning (e.g., LSTMs) to capture complex non-linear irregularities [17,35].

To consolidate the diverse modelling approaches discussed in this section, Table 2 provides a comparative overview of the principal families of prediction and optimization methods used in energy management. The table contrasts these approaches in terms of their underlying techniques, data requirements, computational characteristics, interpretability, and domain suitability. This synthesis helps clarify the practical trade-offs between statistical, machine learning, deep learning, hybrid, heuristic, and reinforcement learning paradigms, and serves as a reference point for selecting appropriate models in IoT-Edge-Cloud energy infrastructures.

Table 2.

Comparative summary of energy prediction and optimization approaches.

Regarding deployment suitability, traditional ML regressors like SVR and Random Forests present a balanced trade-off. SVR is highly effective for small-to-medium datasets often found in building-level metering, providing robust accuracy for non-linear loads [38]. However, its quadratic training complexity makes it unsuitable for continuous on-device retraining in resource-constrained IoT nodes. Deep Learning models (LSTMs, Transformers), while offering superior accuracy for multi-building forecasting [17,39], suffer from high computational opacity and resource demands. Therefore, a hybrid placement strategy is often required: heavy training and hyperparameter tuning are relegated to the Cloud layer, while optimized inference (via quantization or pruning) is deployed to Edge servers or advanced IoT controllers using TinyML frameworks [33,34].

3.2. Optimization and Control Methods

Before examining advanced control architectures, this section outlines the main classes of optimization techniques applied in energy management, emphasizing methods that balance computational feasibility with practical operational constraints.

To contextualize the diversity of available optimization techniques, Table 3 provides a comparative summary of the main control and optimization families used in energy management. The table contrasts their computational requirements, suitability for IoT-Edge-Cloud deployments, and typical application scenarios. This overview helps frame the detailed discussions that follow in subsequent subsections.

Table 3.

Comparison of optimization and control methods in energy management.

3.2.1. Mathematical Optimization Strategies

Before exploring heuristic and learning-based strategies, it is fundamental to acknowledge that mathematical optimization remains the cornerstone of energy management. Approaches such as Linear Programming (LP), Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP), and Convex Optimization provide rigorous guarantees of global optimality and are the standard for Economic Dispatch and Optimal Power Flow (OPF).

Recent advancements have extended these methods to handle the complexities of modern microgrids. For instance, Liang et al. [48] demonstrated that steady-state convex models can enable high-efficiency economic dispatch in hybrid AC/DC networked microgrids. By employing least squares approximation to simplify non-convex bi-directional converter models, they achieved significant reductions in solution time while maintaining physical feasibility. However, as system complexity increases with distributed IoT assets and unknown non-linear dynamics, the reliance on explicit physical models often necessitates shifting toward the heuristic and data-driven methods discussed in the following subsections.

3.2.2. Heuristic and Metaheuristic Strategies

Heuristic and metaheuristic strategies occupy a distinct niche in energy prediction and optimization workflows, balancing exact optimality with computational tractability in complex, high-dimensional decision spaces. In many energy systems, particularly those incorporating distributed resources, storage units, and variable renewable generation, the search space for scheduling or dispatch decisions is too vast for deterministic algorithms to evaluate exhaustively under real-time constraints. Heuristic approaches simplify this problem using rule-based or approximate methods that converge efficiently toward acceptable solutions without incurring the heavy computational overhead of exact solvers. These rules may emerge from expert knowledge, simulation-informed patterns, or operational heuristics accumulated over long deployment periods, allowing for quick adaptation to fluctuating conditions with minimal computation.

Traditional heuristic scheduling in building energy management may prioritize appliance operations based on predefined weights, such as cost savings or user comfort. A simple priority queue can rank devices that may be deferred without degrading service and sequence their activation around tariff shifts. Although such schemes lack the ability to adjust dynamically to unforeseen changes—such as sudden peak periods or abrupt drops in renewable output—their simplicity makes them attractive when hardware limitations preclude more computationally intensive optimization [21]. Coupling heuristics with lightweight sensing platforms enables context-aware adjustments based on occupancy detection or temperature deviations while respecting battery constraints in embedded controllers.

Metaheuristic methods extend these ideas by embedding stochastic exploration into optimization searches, increasing the probability of escaping local optima at the expense of deterministic repeatability. Algorithms such as Genetic Algorithms (GA), Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), Ant Colony Optimization (ACO), and Simulated Annealing introduce probabilistic operators that explore diverse regions of the solution space concurrently or iteratively refine candidate sets. In microgrid dispatch scenarios where integrated renewable sources create unstructured variability, these methods can outperform purely heuristic baselines because they tolerate noisy fitness landscapes and multi-modal payoff surfaces. For instance, PSO can simulate the collective behavior of agents by adjusting scheduling proposals based on both individual performance scores and the best-known global schedules, aligning decentralized behaviors without requiring full centralization.

Hybrid algorithms blending deterministic components with metaheuristics have been proposed to improve convergence speed while retaining flexibility under uncertain input conditions [46]. The imperialist competition algorithm, combined with sequential quadratic programming, illustrates this hybridity: an overarching metaheuristic explores promising regions of the solution space before a mathematical optimization routine fine-tunes the results locally. This symbiosis mitigates the risk that large-scale exploratory phases yield candidate solutions that are far from feasibility, an important safeguard when physical constraints such as load balance, thermal limits, or reserve margins must be satisfied.

Heuristic and metaheuristic strategies also adapt well to multi-agent contexts where coordination among distributed units is essential but global state information may be incomplete or delayed [22]. In such environments, metaheuristics serve as decentralized problem-solving tools, with each agent exploring its subset of possible actions in parallel while periodically exchanging performance summaries with peers. Pareto-based integration mechanisms can synthesize localized results into composite strategies that reflect trade-offs between economic efficiency and technical reliability, thereby avoiding brute-force enumeration across all agents’ joint action spaces.

One practical use case involves the dynamic scheduling of HVAC systems across multiple buildings interconnected through a district grid. Here, a GA can encode combinations of setpoints and operational sequences as chromosomes evaluated against objectives such as aggregate energy reduction and occupant comfort preservation [2]. Crossover operations recombine features from high-performing sequences found across different buildings, spreading effective control patterns throughout the network without imposing a strictly centralized architecture.

Within IoT-Edge-Cloud frameworks discussed in Section 2.4, applying metaheuristics requires sensitivity to latency constraints introduced by distributed computation. Lightweight variants such as Differential Evolution with reduced population sizes can execute directly on edge servers near data sources [16], reducing uplink communication delays by resolving feasible schedules locally before pushing summaries upstream. This layered optimization distributes computational load efficiently across tiers while preserving responsiveness at critical control points.

The uncertainty inherent in renewable generation outputs invites the use of metaheuristics capable of real-time adaptability through continuous re-optimization cycles [46]. Rolling horizon frameworks implement this concept by recalculating schedules periodically within overlapping prediction intervals. At each iteration, heuristic initialization seeds are drawn from previously successful configurations, providing informed starting points for subsequent exploration phases. Embedding forecast errors prevents overfitting to idealized inputs that rarely match live environmental conditions.

In multi-objective situations typical of smart grid operations—balancing cost minimization against carbon reduction—metaheuristics often incorporate objective scalarization techniques within their fitness evaluations [22]. Weight vectors applied within scalarization functions allow for the dynamic adjustment of priorities without retraining models or restructuring algorithm flow. This tunability is particularly valuable under shifting policy mandates or seasonal variations where economic incentives fluctuate relative to sustainability targets.

Explainability challenges are pronounced because stochastic search processes do not offer straightforward causal chains linking inputs to outputs. Interpretable surrogates can partially address this gap: post hoc regression models fitted to logged heuristic or metaheuristic decisions approximate decision boundaries in more transparent mathematical terms, enabling analysts to infer predominant drivers behind observed optimization patterns even when direct path tracing through probabilistic search history is infeasible.

Another layer appears when federated learning concepts intersect with metaheuristics deployed across heterogeneous nodes [17]. Instead of sharing raw datasets, nodes exchange tuned parameter sets—mutation rates, crossover probabilities—shown to perform well locally. Aggregating this “algorithm configuration intelligence” can accelerate global convergence faster than redistributing consumption data alone, while maintaining privacy and leveraging diverse experiential coverage.

Applications spanning distributed storage management highlight how metaheuristics accommodate discrete action sets alongside continuous control variables [3]. Scheduling charge/discharge cycles involves binary activation decisions paired with continuous rate settings driven by predicted demand; encoding both seamlessly within candidate representations enables joint optimization without artificial problem decomposition.

Integrating domain-specific heuristics into generic metaheuristic frameworks enhances the practicality of solutions. Constraint-handling mechanisms tailored to energy systems—such as penalty functions tied directly to violations of power-quality metrics—guide exploration toward deployable configurations rather than abstract optima misaligned with physical realities. This blend respects structural limitations while leveraging stochastic breadth to react effectively under operational pressure.

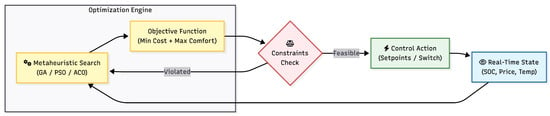

The execution flow of these heuristic strategies is visualized in Figure 6. Unlike analytical solvers, metaheuristics operate through an iterative search loop, evaluating candidate solutions against an objective function and physical constraints before issuing a control action.

Figure 6.

The iterative optimization loop in heuristic-based energy management. The engine receives real-time state data and explores the solution space (e.g., via Genetic Algorithms or PSO) to find optimal setpoints that satisfy physical constraints [1,46].

The suitability of these optimization methods varies significantly across the architecture. Simple heuristic strategies (rule-based) are extremely lightweight and deterministic, making them ideal for the lowest IoT tier (e.g., smart plugs or thermostats) where immediate, fail-safe actuation is required [21]. In contrast, metaheuristics like GA or PSO offer the advantage of navigating non-convex solution spaces—typical in multi-source microgrid dispatch—without requiring gradient information. Their main limitation is the stochastic nature of the search, which does not guarantee global optimality and can be computationally expensive per iteration [46]. Thus, metaheuristics are best deployed at the Edge Server or Fog layer, where sufficient computing power exists to run population-based simulations within acceptable operational time windows.

Recent advancements in optimization have moved beyond standalone metaheuristics toward hybrid and hierarchical frameworks that address the limitations of traditional bio-inspired algorithms. While standard evolutionary methods effectively navigate non-convex spaces, modern approaches increasingly integrate them with learning-based components to handle dynamic constraints. For instance, hierarchical structures now allow for adjustable levels of control, where high-level agents determine strategic parameters while low-level optimizers manage device-specific constraints, significantly outperforming fixed-hierarchy baselines [46,50]. Furthermore, to address the multi-objective nature of microgrid scheduling (e.g., balancing cost vs. battery degradation), recent techniques have adopted Pareto optimization combined with Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) agents. This integration allows the system to dynamically select actions from a set of Pareto-dominant solutions based on operator preferences, rather than relying on static weightings common in older heuristic implementations [22]. Similarly, safety-constrained optimization has evolved to incorporate “safety filters” directly into the learning loop, ensuring that stochastic search actions do not violate physical grid limits [51].

3.3. Multi-Agent Approaches in Energy Systems

To frame how autonomous entities collaborate within modern energy infrastructures, this section reviews distributed coordination mechanisms that enable scalable, resilient, and interoperable multi-agent operation.

Distributed Coordination Strategies

Distributed coordination in multi-agent energy systems concerns how locally autonomous decision-makers align their actions to maintain overall operational objectives without relying on continuous centralized oversight. Strategies here must account for diverse factors: communication topology, computational distribution, heterogeneity in device capabilities, and fluctuating environmental conditions. One recurrent theme is negotiating the trade-off between decentralized autonomy and the need for global coherence in executing schedules or balancing loads. Purely decentralized algorithms offer advantages in latency and privacy by keeping decisions close to data sources, but risk suboptimality if agents lack sufficient situational awareness. Conversely, central optimization can, in theory, reach better global optima, yet often stalls under the computational and communication burdens of large-scale real-time control.

A common approach to distributed coordination is decomposition-based optimization, in which a large centralized problem is split into smaller local subproblems assigned to each agent. Coordination proceeds by iteratively exchanging aggregate variables or dual information that guide local solvers toward consistency. These methods scale well when the local subproblems remain convex [23], as in certain storage-scheduling or demand-response formulations. However, nonconvexities introduced by discrete decisions, such as binary ON/OFF states in diesel backup generators, may compromise convergence guarantees or necessitate heuristics to repair feasibility. In microgrid contexts, hybrid arrangements have been trialed: a centralized model predictive control (MPC) layer computes reference trajectories for distributed agents equipped with reinforcement learning policies that rapidly adjust to deviations [3]. Here, distributed reinforcement learners adapt to short-term anomalies while the centralized planner enforces long-term goals.

Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning (MARL) frameworks form another pillar for coordination strategies under distribution. By modeling energy management interactions as partially observable Markov decision processes (POMDPs), MARL enables each agent to learn policies conditioned on local observations while embedding mechanisms—such as reward shaping and parameter sharing—that incentivize alignment with system-level performance metrics. Variants like Multi-Agent Proximal Policy Optimization (MAPPO) have demonstrated stable policy improvements in domains such as peer-to-peer (P2P) trading and EV charging management, where agents must balance self-interest with collective welfare over repeated interactions. Coordination emerges indirectly through learned value functions that internalize both individual and shared payoffs.

Auction-based protocols integrated into MARL settings leverage market analogies: agents submit bids reflecting their local utility for resources such as charging capacity or discharge opportunities from shared storage; allocation follows predefined rules that aim to maximize social welfare under constraints [19]. Such dynamic pricing exchanges enable flexible load shifting in response to forecasted congestion or scarcity, capitalizing on predictive features embedded in agent policies. The strategy’s strength lies in converting complex coupling constraints into price signals interpretable by heterogeneous devices—from advanced controllers to lighter embedded nodes—without revealing sensitive raw data about local states.

In bi-level optimization schemes suited for building-to-grid coordination, an upper strategic level determines parameters such as time-varying tariffs or demand response targets, while a lower operational level executes these directives inside each building energy management system [52]. This hierarchical distribution separates concerns: the upper tier addresses market integration and grid stability; the lower tier handles occupant comfort and device-specific constraints. Information flows upward via aggregated forecasts and downward via control setpoints or incentive parameters, thereby reducing bandwidth requirements relative to full-state broadcasting.

Peer-to-peer topologies present additional opportunities where no fixed hierarchy exists. Agents interact directly with neighbors to negotiate bilateral exchanges of energy or capacity commitments. Reputation systems or credit mechanisms can reinforce cooperative behavior amongst self-interested entities operating over unreliable communication links. When paired with fuzzy Q-learning adaptations [43], agents can navigate uncertain partner behaviors or incomplete operational data by adjusting policy confidence based on interaction outcomes.