Abstract

The floor acoustic package is a crucial component of a vehicle’s overall acoustic insulation system, and its performance directly influences the interior sound field distribution and acoustic comfort. Conventional investigations of acoustic package performance primarily rely on experimental testing and computer-aided engineering (CAE) simulations. However, these methods often suffer from limited accuracy control, high computational cost, and low efficiency. In contrast, data-driven modeling approaches have recently demonstrated strong potential in addressing these challenges. In this paper, a Squeeze-and-Excitation Residual Network (SE-ResNet) is proposed to predict and analyze the sound insulation performance of vehicle floor systems based on the original structural and material parameters of acoustic package components. By replacing the conventional CAE process with a data-driven framework, the proposed method enhances prediction accuracy and computational efficiency. With the lowest recorded RMSE of 0.4048 dB across the 200–8000 Hz spectrum, the SE-ResNet model ranks first in overall performance. It substantially outperforms the SE-CNN (0.9207 dB) and also shows a clear advantage over both the SE-LSTM (0.4591 dB) and the ResNet (0.4593 dB). Validation using the acoustic package data of a new vehicle model further confirms the robustness of the proposed approach, yielding an overall RMSE = 0.4089 dB and CORR = 0.9996 on the test dataset. These results collectively demonstrate that the SE-ResNet-based method presents a promising and robust solution for forecasting the sound insulation performance of vehicle floor systems. Moreover, the proposed framework offers methodological and technical support for the data-driven prediction and analysis of other vehicle noise and vibration problems.

1. Introduction

Driven by economic advancement and swift progress in the automotive industry, ride comfort has become a paramount competitive factor. Among various comfort evaluation indicators, NVH (noise, vibration, and harshness) performance is closely linked to the perceived comfort of vehicles and serves as a crucial indicator for assessing overall ride quality, having garnered widespread attention across the automotive sector [1,2]. The sources of noise inside a vehicle are closely related to external traffic noise and vibration. Road traffic noise and vibration share the same source but propagate in different directions, both heavily dependent on vehicle type, operating conditions, and road surface quality [3]. Vibrations generated by these external stimuli are transmitted through the structure to the vehicle body, particularly the floor system, directly impacting the NVH levels inside the cabin. Research also indicates that the interaction between road surface irregularities and vehicle design [4] translates into structural noise and vibration within the cabin, significantly affecting the vehicle’s overall NVH performance. As the primary passive control measure for reducing interior sound pressure—particularly mid-to-high-frequency airborne noise—the acoustic package directly shapes the cabin’s sound field and acoustic quality. Moreover, its sound absorption and insulation capabilities fundamentally govern the vehicle’s ultimate NVH performance level [5]. As a critical element of the acoustic package, the floor system acts as a barrier between the external environment and the interior cabin and governs the penetration of external noise into the occupant space [6]. Advanced acoustic package design achieves multiple objectives, including cabin noise reduction, acoustic quality enhancement, and satisfaction of lightweight and cost targets, making it a field of considerable practical value and direct applicability in engineering.

The early phase of acoustic package design and development was predominantly driven by prototype testing and comparative component validation, as conventional simulation techniques like the Finite Element Method lacked the requisite accuracy for medium-to-high-frequency noise predictions. These methods not only have a long cycle and high cost but also rely too much on experience [7]. Advancements in Statistical Energy Analysis (SEA) theory [8], along with the proliferation of commercial software such as VA One, have substantially enhanced the prediction accuracy for mid-to-high-frequency cabin noise. To address the optimization of automotive acoustic packages, Dong et al. [9] proposed an efficient robust method, which begins by constructing a vehicle model based on the SEA method. In their work, the original two-layer nested optimization problem was converted into a consolidated single-layer formulation via the interval possibility method, thereby enabling a significant improvement in sound insulation performance while reducing the package weight. By integrating both material cost considerations and quality requirements constraints with the application of the SEA method, Musser [10] achieved the simultaneous optimization of acoustic performance and resource efficiency. Based on the SEA method, Wu et al. [11] proposed an acoustic package component target setting method that transforms performance design into an optimization task. It synthesizes component insertion loss and driver’s ear-side SPL constraints, enabling early-stage NVH target decomposition and vehicle model refinement. Through the application of a simplified SEA cavity model, Liu et al. [12] analyzed the impact of interior materials on cabin sound pressure and confirmed its excellent agreement with measured data across mid and high frequencies. Lee et al. [13] used sensitivity analysis to reveal how trim materials and subsystem divisions affect SEA parameters. Separately, Salmani et al. [14] developed and validated a model to assess vehicle acoustic package sound insulation based on SEA. Their results showed strong agreement between simulations and experiments conducted using a reverberation-room-to-semi-anechoic-chamber setup. Chen et al. [15] carried out in-depth acoustic package optimization for specific models (such as diesel pickups). They innovatively combined SEA with engine noise attenuation methods to accurately identify the weak links of acoustic packages such as the front wall and middle channels. Through material and structural improvement, the interior noise and speech intelligibility of the vehicle have been significantly improved. The research of Zhang et al. [16] focused on the lightweight and performance collaborative optimization of acoustic packages. They determined the key optimization component (the front wall metal) through the SEA model verified by experiments and innovatively combined the response surface method with the range analysis to select the significant factors as variables. By adhering to the constraint of maintaining the original thickness and weight, the optimization process successfully achieved a dual outcome: a notable enhancement in mid-frequency noise reduction for the entire vehicle and a net reduction in the mass of the acoustic package itself. Although methods such as SEA have made positive progress in promoting acoustic package modeling and optimization, traditional methods generally have limitations such as relying on empirical equations, high test costs, and insufficient modeling of complex nonlinear relationships [17]. As the automotive industry evolves toward electrification and lightweight design, acoustic issues demonstrate increasingly complex mechanistic characteristics, while the limitations of traditional simulation methods become more apparent. Therefore, it is urgent to develop new prediction methods to describe the performance of acoustic packets more efficiently and accurately.

The rapid evolution of deep learning offers a powerful new paradigm for predicting acoustic performance. Deep learning can automatically extract complex features and learn nonlinear mapping relationships, which provides an effective means to solve the bottleneck of traditional methods in high-dimensional nonlinear modeling and prediction accuracy [18]. Within the domain of vehicle NVH research, a growing interest has emerged in exploring the application of diverse deep learning models for predicting acoustic package performance. To address the optimization challenges in electric vehicle acoustic packages, Huang et al. [19] introduced an innovative knowledge-and-data-driven approach. Their method integrates a multi-layer, multi-objective knowledge model with a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network based on an adaptive learning rate forest, significantly enhancing the effectiveness and robustness of optimizing sound performance. To address the challenge of assessing acoustic comfort within engineering machinery cabs, Dai et al. [20] developed a combined subjective-objective evaluation framework and proposed a hybrid model that integrates Particle Swarm Optimization with a Random Forest (PSO-RF). The model enabled accurate prediction, which has facilitated the acoustic package design optimization for specialized vehicle cabs. Zhao et al. [21] developed a machine learning model (GA-RF) that integrates genetic algorithm and random forest for assessing vibration comfort in engineering machinery cabs. By combining subjective and objective evaluation methods, they developed a quantitative relationship between vibration signatures and human comfort response, allowing reliable forecasting of vibration comfort levels. Schaefer et al. [22] constructed the mapping relationship between the material type, cost, and weight of the acoustic package through the deep neural network and realized the lightweight optimization of the acoustic package by combining the particle swarm optimization algorithm. This optimization yielded a concurrent 15.21% reduction in weight and a 9.7% reduction in cost, while fully maintaining the original sound insulation performance. Shang et al. [23] introduced a structural path optimization approach based on a genetic algorithm and convolutional neural network (GA-CNN), which effectively identifies and suppresses critical vibration transmission paths. Their results confirmed its efficacy in reducing the contribution of the engine mount’s structural path to interior noise irritation, leading to a significant improvement in overall sound quality. To achieve efficient and precise assessment of front wall system acoustic insulation, Ma et al. [24] developed an adaptive weighted feature learning convolutional neural network (AWFL-CNN). This data-driven method thereby allows for efficient performance evaluation. Aiming at the road noise problem of electric vehicles, Pang et al. [25] introduced a systematic modeling methodology that integrates mechanistic and data-driven approaches. Within this framework, an Autoencoder Long Short-Term Memory (AE-LSTM) network was employed to achieve accurate predictions, thereby establishing an efficient hybrid tool for exploring the acoustic package design space and analyzing performance trade-offs. Huang et al. [26] introduced a deep convolutional neural network (CNN) model that leverages noise time-frequency representations as input to evaluate vehicle interior sound quality. This data-driven approach enables autonomous feature learning, providing an end-to-end intelligent solution for assessing the acoustic package’s contribution to the in-cabin sound environment.

However, the existing deep learning methods still have shortcomings in acoustic performance prediction. Some methods have limited generalization performance when dealing with complex multi-layer structures, and some models have insufficient extraction of key acoustic information in feature expression [27]. As an important extension of deep learning, attention mechanisms have been gradually applied to complex system modeling and acoustic performance prediction [28]. Different types of attention mechanisms show their own advantages in feature selection and representation enhancement. Spatial attention (SA) can focus on the local positional relationship of input features and is suitable for salient region modeling of image or time-frequency spectrum signals [29]. Hybrid attention (HA) has achieved good results in speech recognition and semantic segmentation tasks by combining channel and spatial weight allocation at the same time [30]. Conditionally Parameterized Convolutions achieve a significant improvement in model expressiveness by dynamically adjusting the convolution kernel parameters under input-dependent conditions [31]. However, most of these methods rely on the support of large-scale datasets, and the computational cost is large. It is easy to produce over-fitting in small and medium sample scenarios, and the interpretability of engineering problems is limited.

In contrast, the Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) method [32] shows higher applicability in feature prediction due to its simple structure, low computational cost, and good portability. The SE module performs weight calibration on the input feature channel through the “compression-excitation” process, so that the model can highlight the physical features highly related to the target output and suppress redundant information, improve the prediction accuracy, and give the model stronger interpretability. Liu et al. [33] proposed SE-Block and significantly improved the performance of the Residual Network (ResNet) in image recognition tasks. Duan et al. [34] applied the SE mechanism to the speech recognition network, which effectively enhanced the correlation modeling ability between channels. Ying et al. [35] proposed a new PSE module using parameterized Sigmoid activation function for SE block, which is widely used in visual tasks. This module is capable of simultaneously suppressing non-informative features and enhancing discriminative ones, a capability which was validated across multiple datasets. In their work based on the SE-ResNet principle, Xu et al. [36] constructed both channel-pooling and position-pooling attention modules to extract highly discriminative features. Experiments on PASCAL and Cityscapes datasets show that its performance is significantly better than basic models such as FCN. In summary, SE-ResNet integrates residual learning with a channel attention mechanism. This architecture not only mitigates the gradient vanishing problem inherent in deep network training but also enhances prediction accuracy and stability through adaptive feature recalibration. SE-ResNet is especially suitable for acoustic modeling scenarios with limited input feature dimensions but significant channel physical meaning, such as automotive floor systems. Therefore, this paper proposes that SE-ResNet as a prediction framework is reasonable and targeted, not just a direct application of deep learning methods.

As indicated by prior studies, the sound insulation performance of acoustic packages exhibits highly nonlinear characteristics. Traditional methods like the SEA method prove inefficient in handling such problems, often incurring significant labor and costs [37]. The data-driven method provides a new way to solve such problems. By employing measured data as inputs, the data-driven method for predicting floor system sound insulation offers dual advantages: parameter acquisition is simplified, and modeling efficiency is high. Moreover, its continuous learning capability enables ongoing model enhancement, which significantly boosts prediction efficiency and accuracy while diminishing the need for traditional testing. Current data-driven approaches are confronted with two primary obstacles in the modeling process: limited sample sizes and insufficient feature extraction, thus potentially compromising the model’s generalization ability [38].

Guided by the foregoing discussion, this research presents an SE-ResNet-based framework to predict and analyze sound insulation performance of automotive floor systems in the 200–8000 Hz frequency range. The key innovations, which address existing challenges, lie in two primary aspects:

- This paper proposes a data-driven methodology that enables accurate prediction of automotive floor system sound insulation performance, creating a direct mapping from structural and material parameters to system-level acoustic characteristics. It breaks through the limitations of traditional simulation analysis that relies on a large number of calculations and experimental verifications. It significantly enhances modeling efficiency without compromising prediction accuracy, thereby offering a promising alternative for NVH development in the early vehicle design phase.

- The SE-ResNet model is constructed by combining the channel attention mechanism with the ResNet, which effectively enhances the performance of key acoustic features and improves the generalization performance of the model. This approach effectively captures the intricate interactions within complex acoustic structures, a challenge for traditional deep learning models, while maintaining interpretability. It thereby delivers more actionable insights to guide acoustic package design and optimization decisions.

The structure of this paper is as follows: Section 2 introduces the deep learning methods used, including the basic principles of ResNet and its application in acoustic prediction, and further elaborates the improvement ideas and network structure of SE-ResNet. Section 3 describes the acquisition and experimental design process of sound insulation performance data of an automobile system, which provides data support for model construction and verification. Section 4 details the development process of the SE-ResNet prediction model, including network construction, training strategy, and implementation of prediction results. Section 5 discusses and analyzes the performance of the model. Firstly, the prediction advantage of SE-ResNet is verified by comparison with SE-CNN, SE-LSTM, and ResNet, and then its generalization ability and stability are tested by independent samples. Section 6 concludes the paper by highlighting the main contributions and innovations and suggests potential directions for future research.

2. The Proposed Method

2.1. ResNet

Traditional CNN faces two major problems when stacking deep networks: gradient disappearance/explosion and network degradation [39]. With the increase in network depth, the gradient needs to be amplified layer by layer in the back propagation process, which easily leads to the shallow gradient approaching zero (disappearing) or infinitely increasing (exploding), thus affecting the effective update of the underlying parameters [40]. For example, Hasan et al. [41] found that VGG-19 requires 36 epochs more than VGG-16 on the same dataset, GPU time increases by 37%, and training loss is higher. When the depth exceeds 16 layers, the optimization difficulty increases significantly. More importantly, even with normalization techniques applied to mitigate gradient issues, merely increasing network depth can still lead to degradation—a phenomenon where the deep model exhibits a higher training or test error than its shallower counterpart. This phenomenon is not due to overfitting but because the optimization difficulty of nonlinear mapping increases exponentially with depth [42]. To address these issues, Kaiming He et al. [43] introduced the ResNet in 2016. The core idea is to introduce RL and Shortcut Connection (SC) to transform the network layer from direct fitting target mapping to learning residual mapping. Through this design, the network can flexibly skip redundant layers, retain shallow features, and effectively alleviate the problem of gradient propagation attenuation.

The basic unit of ResNet is the residual block [44], which mainly includes two types: (1) the basic block is composed of two 3 × 3 convolutional layers, which is suitable for shallow networks (such as ResNet-18/34); (2) the bottleneck block first reduces the dimension and then increases the dimension through 1 × 1 convolution (the structure is 1 × 1 → 3 × 3 → 1 × 1), which is suitable for deep networks (such as ResNet-50/101/152), while reducing the amount of calculation. The whole network can be divided into three parts: (1) the initial layer quickly downsamples the input features through convolution and maximum pooling. (2) The residual stage is stacked by multiple residual blocks. Within each block, a convolution with a specific stride is applied to reduce the spatial size of the feature maps, serving to simultaneously increase the channel count by a factor of two. (3) The classification layer consists of a Global Average Pooling (GAP) module and a fully connected layer. The GAP operation condenses the spatial features and inputs them to the fully connected layer for final prediction. In order to achieve RL, the architecture employs skip connections to mitigate the problem of gradient vanishing. Its implementation involves two scenarios: Identity Shortcut is applied when the input and output dimensions match, enabling direct addition. When dimensions differ, however, a 1 × 1 convolution adjusts the channels to enable effective feature fusion.

The specific expression of the residual block is as follows:

Here, represents the underlying mapping to be learned, denotes the residual function, and denotes the input.

The residual block employs a dual-pathway mechanism for processing feature data: one pathway applies nonlinear transformation via the residual function , while the other preserves the original input via the identity mapping . When the matrices from both paths are aligned in spatial size and channel depth, they are combined through element-wise addition. The resultant signal is then processed by the ReLU activation function, yielding the final output of the residual block:

Here, represents the residual block output, denotes the residual function, and x denotes the input feature. If the two paths are inconsistent in size or number of channels, they need to be aligned first: when the spatial dimension is different, the smaller matrix can be extended by padding; when the number of channels is inconsistent, the input channel is adjusted by 1 × 1 convolution WWW to match the residual path. After the alignment is completed, the matrix still adopts the element-by-element addition method, and the final result is output by the ReLU activation function:

Here, denotes the output of the residual block, and represents the convolutional kernel weights. These parameters ensure effective fusion of features from different paths and maintain stable gradient propagation through the deep network.

2.2. SE-ResNet

The flexibility of ResNet has spawned a variety of improved versions, including the following: ResNeXt achieves multi-path feature fusion by introducing grouping convolution (Cardinality) to improve model expression ability. SE-ResNet incorporates a channel attention mechanism, specifically the SE block, into the standard ResNet architecture. This integration allows the network to dynamically recalibrate the importance of individual feature channels. Meanwhile, Wide-ResNet is better suited for small datasets by prioritizing an increase in the number of channels per layer (i.e., a “width-first” approach) over simply stacking more layers. Jie Hu et al. [45] proposed SE-ResNet in 2018. Its core innovation is a two-stage process integrated into the residual block: first, the incorporation of a SE module, and second, the deployment of a channel attention mechanism. This mechanism dynamically recalibrates feature channel weights, thereby enhancing the network’s perception of informative features. This enhances the model’s sensitivity to critical features and strengthens its overall representational capacity. Specifically, SE-ResNet can be understood from three parts: residual branch, SE module, and skip connection [46]. The residual branch is responsible for learning the residual function between input and target output, and its calculation can be expressed as follows:

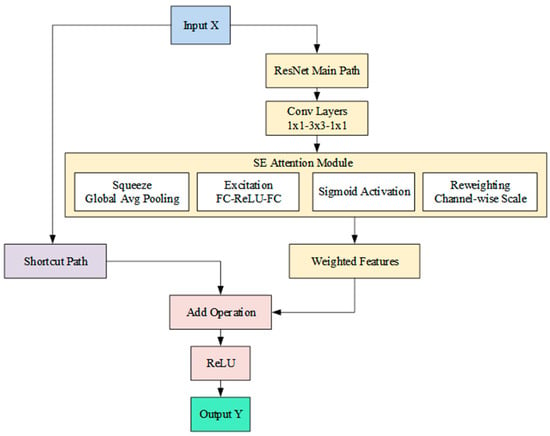

Here, and denote the weights of convolution kernels, BN denotes the batch normalization operation, ReLU serves as the activation function, denotes the input, and represents the residual function. The integration of the SE module into the residual branch enables dynamic feature recalibration through attention-weighted channel responses, producing a dual effect: it amplifies the expressiveness of salient features while ensuring robust information flow via the skip connection. The corresponding structure of SE-ResNet is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Structure diagram of SE-ResNet.

The SE module is strategically embedded at the terminus of the residual branch. This placement enables it to calibrate the channel-wise weights of the residual output, thereby selectively enhancing the responses of the most critical channels. The SE module mainly includes three steps: compression (Squeeze), excitation (Excite), and feature recalibration. In the Squeeze stage, the spatial content of each channel in the input feature map is compressed by GAP into a channel-wise global descriptor. This operation is mathematically formulated as follows:

Here, represents the c-th channel of the input feature map with a spatial size of , and is its compressed channel value. The Excitation phase models the interdependencies among channels using two fully connected layers and a nonlinear activation function, thereby generating a channel weight vector:

Here, denotes the weight matrix of the first fully connected layer, serving to reduce dimensionality to . Subsequently, , the weight of the second fully connected layer, restores the dimension to the original channel number . Furthermore, δ represents the ReLU activation function, while σ denotes the Sigmoid function. These serve distinct roles in the attention mechanism, with ReLU enabling non-linear transformation and Sigmoid generating normalized channel weights. In the feature recalibration stage, the channel weight is multiplied by the residual branch output channel by channel, and the weighted feature map is obtained:

Here, represents the weighted feature map, and denotes the channel-wise weight. Finally, the original input is combined with the SE-processed residual output via a skip connection. For the case where the input and output dimensions are aligned, the residual block produces the following output:

If the dimensions do not match, the input is mapped by 1 × 1 convolution and then added:

This design ensures the effective combination of channel attention mechanism and jump connection, so that the network can highlight the key features in the deep structure while maintaining stable gradient transmission.

3. Experiment

In acoustic research, sound insulation quantity is a pivotal metric for evaluating material performance [47], as it quantifies the energy attenuation of sound waves transmitted across materials. The quantity R (in dB) is defined mathematically as follows, representing ten times the base-10 logarithm of the incident to transmitted sound energy ratio:

Here, E represents the total acoustic energy incident upon the material, denotes the acoustic energy transmitted from the material, and refers to the sound energy transmission coefficient.

Sound transmission loss is denoted as STL [48]. It is quantified as ten times the base-10 logarithm of the ratio of the incident sound energy to the transmitted sound energy, with results expressed in decibels (dB). A larger value of this parameter indicates a smaller amount of transmitted sound energy, meaning that the sound insulation capability of the assembly is superior. Its mathematical expression is:

Here, is defined as the incident acoustic energy and as the transmitted acoustic energy. Based on measurement results, is calculated as follows:

Here, represents the average sound pressure (Pa) in the reverberation chamber. Characterized by minimal sound absorption, long reverberation time, and a diffuse sound field, the reverberation chamber maintains an exceptionally stable and consistent sound pressure level. Therefore, three acoustic sensors can be arranged in the reverberation chamber for measurement and averaging. In addition, S is the measured area (m2), ρ is the air density (1.29 kg/m3), and c is the sound velocity in the air (340 m/s). The transmitted acoustic energy can be expressed as:

Here, represents the average sound intensity (W/m2) on the surface of the test specimen, which is measured by the sound intensity probe at multiple positions and averaged, and S denotes the area of the test specimen. By integrating the equations presented above, we can derive the final expression for the STL:

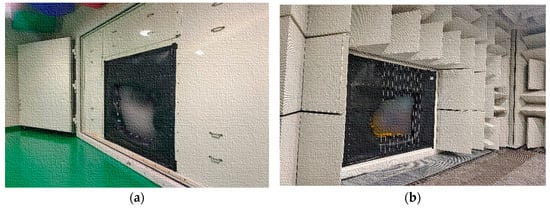

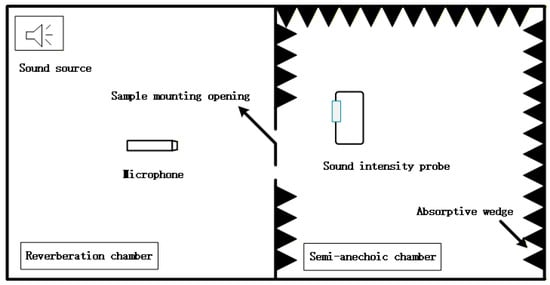

The sound insulation performance of the floor system is evaluated following a standardized testing methodology that employs a reverberation chamber as the sound source room and a semi-anechoic chamber as the receiving room. The STL is utilized as the key quantitative metric for this assessment. All testing follows the protocols defined in the SAE J1400-2700 standard published by the International Society of Automotive Engineers [49]. The experimental arrangement is configured as follows: The sample is mounted in the test opening of the insulation wall. Firstly, the reverberation chamber acts as the source room, designed to generate the sound field. The reverberation chamber is equipped with four microphones to record sound pressure levels under white noise excitation at an overall level of 120 dB. The semi-anechoic chamber, which simulates a free-field acoustic environment, serves as the receiving room. Within it, two sound intensity probes systematically scan specific areas to measure the transmitted sound intensity. By integrating these measurements with the equations presented earlier, the STL of the test specimen can be determined. Figure 2 shows a schematic of the test environment configuration, and the schematic diagram of the test apparatus layout is shown in Figure 3. The connections between the fixture and sample are sealed with acoustic sealant to prevent sound leakage during testing, ensuring that the only preserved opening on the sample is the channel connecting the source and receiving chambers. In the test, the acoustic sealing strip can effectively seal the pores and reduce the acoustic leakage and structural vibration. Characterized by strong adhesion, the adhesive attaches securely to the sound insulation surface, a feature critical for maintaining the accuracy of the test outcomes. Following standard testing protocols, the sealing strip must cover all potential leakage paths, with the exact coverage dictated by the relevant test specifications and experimental design.

Figure 2.

Reverberation-semi-anechoic chamber environment for sound insulation performance test: (a) reverberation room; (b) semi-anechoic room.

Figure 3.

Test setup layout diagram.

In addition, the original structural parameters of the typical pure electric vehicle floor system selected are illustrated in Table 1, including the area and coverage of the carpet, trunk carpet, rear floor carpet, and front, middle, and rear floor metal. The thickness distribution characteristics of different sound insulation components are listed in Table 2. The carpet is mainly composed of medium and high thickness layers, the trunk carpet is thinner as a whole, and the rear floor carpet is the highest in the thickness range of 10 mm. The thickness information of the sheet metal parts is shown in Table 3. The equivalent thickness of the front, middle, and rear floor metal ranges from 0.7 to 1.2 mm, a design that balances sound insulation effectiveness with lightweight requirements. These structural parameters provide a data foundation for subsequent sound insulation performance prediction and model training.

Table 1.

Original parameters of the floor system components.

Table 2.

Sound insulation pad thickness.

Table 3.

Sheet metal thickness.

The input parameters of the model cover the geometric and material characteristics of the floor sheet metal and the multi-layer sound insulation pad, including the surface area, coverage, and equivalent thickness of the carpet, trunk carpet, and the sound insulation pad under the back floor, as well as the surface area and equivalent thickness of the front floor sheet metal, the middle floor sheet metal, and the back floor sheet metal. Due to the absence of the coverage parameter in sheet metal, zero padding is used to align the input data dimensions. The complete input parameter table is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Input parameter.

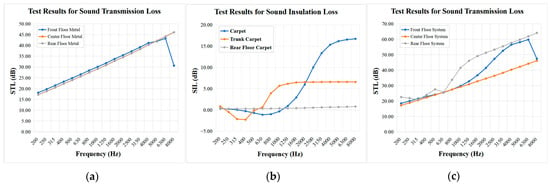

The aforementioned components were evaluated in a reverberation semi-anechoic chamber, yielding the sound insulation performance curves for each component as shown in Figure 4. These curves generally increase with the increase in frequency and STL increases, and there are fluctuations in some frequency bands, reflecting the acoustic differences of different materials and structural layers in the middle and high frequency bands, which provides a reliable experimental baseline for subsequent model training and component/system level mechanism analysis.

Figure 4.

Test results of floor components: (a) STL test results of sheet metal parts; (b) sound insertion loss test results of insulation pad; (c) system-level STL test results.

4. Model Development

4.1. Development of SE-Resnet Model

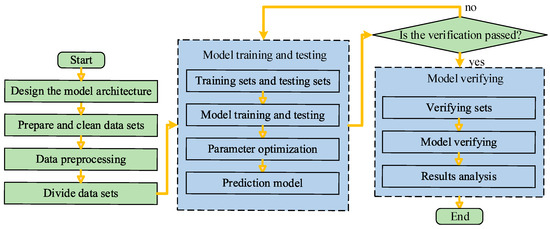

To establish a reliable framework for forecasting the acoustic insulation of automotive floor systems, a specialized SE-ResNet architecture was developed. This development primarily encompassed three key stages. The first stage of the research involves data preparation and preprocessing. This is followed by the second stage, which is the construction and training of the algorithmic model, encompassing key steps such as network structure design, hyperparameter optimization, and iterative training. The third stage is model performance prediction. The overall modeling process is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

SE-ResNet modeling flow chart.

The sample data utilized for model development were sourced from both experimental tests and numerical simulations, as detailed in Section 3. The complete dataset comprises 400 distinct instances, each representing the sound insulation performance of the floor system. Among them, 200 sets of data were obtained through testing, and the other 200 sets of data were corrected from the VA ONE simulation results.

The output parameters of the model are defined as the STL values of the vehicle floor system at 17 one-third octave band center frequencies, spanning from 200 Hz to 8000 Hz. Since the input and output parameters differ considerably in their numerical scales, all data undergo a normalization process before being introduced to the model, where they are linearly transformed to the [0,1] interval to enhance the model’s convergence rate and ensure training stability. This preprocessing step is implemented to mitigate the adverse effects of scale disparity among disparate features on training accuracy, thereby effectively reducing training bias [50]. The detailed normalization computation is presented in Equations (15) and (16):

Here, X represents the two-dimensional data matrix to be normalized; X. max (axis = 0) is the row vector composed of the maximum values in each column; X. min (axis = 0) denotes the row vector consisting of the minimum values in each column; max and min are the maximum and minimum values of the target mapping interval, with default values of 1 and 0, respectively; is the normalization result; represents the denormalized results. The normalized 400 groups of samples are divided into training set and test set according to the ratio of 8:2. The dataset is partitioned into 320 groups for training and 80 for testing. The model’s generalization capability and predictive accuracy are then evaluated on the test set by analyzing the errors between predicted and measured values [51].

The constructed SE-ResNet network combines the advantages of RL and a channel attention mechanism. The residual module effectively alleviates the problem of gradient disappearance through fast connection and enhances the extraction ability of deep features [52]; the SE module realizes the adaptive weight distribution of channel features through the “compression-excitation” operation, highlighting the most critical feature information for STL prediction. The overall network architecture incorporates three sets of SE-embedded residual blocks for feature extraction. In the final phase, the processed features are passed through a GAP layer and a two-layer fully connected network to perform the STL prediction. Dropout is introduced in appropriate layers of the network structure to suppress overfitting and enhance generalization ability [53].

The main structural parameters of the SE-ResNet are illustrated in Table 5.

Table 5.

The main structural parameters of SE-ResNet.

The model training is conducted using the PyTorch 2.6.0 deep learning framework and the Python 3.10 programming language. Huber loss is selected as the loss function to take into account the ability to resist outliers and convergence stability. An Adam optimizer is employed with an initial learning rate of 0.001. A weight decay coefficient of 1e-5 is applied to prevent overfitting. The training was conducted on a computer with an Intel Core i7-14700 KF (Intel, Santa Clara, CA, USA) processor, 64 GB of memory, and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4060 Ti graphics card (NVIDIA, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The trained model demonstrates high prediction accuracy and stability across the entire frequency range, enabling rapid analysis and prediction of the vehicle floor system’s sound insulation performance.

4.2. Prediction of SE-Resnet Model

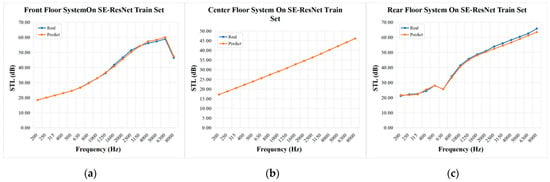

This paper conducts a systematic evaluation of the aforementioned SE-ResNet model’s predictive performance using both training and test set samples. To test its efficacy, a comprehensive comparison is made between the predicted values and the experimentally measured values at 17 one-third octave center frequency points within the 200–8000 Hz range. The 400 datasets are randomly divided into training, test, and validation sets at a ratio of 7:1.5:1.5. Figure 6 and Figure 7 illustrate the comparison between the prediction results of the model on the training set and the test set and the real values. The hyperparameters in this study are selected by a systematic program. Specifically, Latin hypercube sampling is first used to generate multiple hyperparameter combinations. Then, each combination is used to train a model, and their prediction performance is compared mainly based on root mean square error (RMSE) and correlation coefficient (CORR). Finally, the hyperparameter set with the best performance on the validation set is selected for model training. This method allows effective exploration of the parameter space and determines the optimal configuration based on clear performance indicators.

Figure 6.

Prediction results of the SE-ResNet model for the sound insulation performance of the floor system (training set): (a) results of the front floor system; (b) results of the middle floor system; (c) results of the rear floor system.

Figure 7.

Prediction results of the SE-ResNet model on the sound insulation performance of the floor system (test set): (a) results of the front floor system; (b) results of the middle floor system; (c) results of the rear floor system.

As shown in the figures above, the prediction trend of the SE-ResNet model aligns closely with the measured values across most frequency points, effectively capturing the STL characteristics of the floor system in different frequency bands. Particularly in the mid- to high-frequency range, the predicted curve nearly overlaps with the measured one, demonstrating the model’s robust fitting capability and stability in handling the complex acoustic behavior of the multi-layer floor system. To more precisely quantify the prediction accuracy, this paper selects the RMSE and the CORRas quantitative evaluation metrics. RMSE and CORR serve to measure the global deviation and the linear correlation strength, respectively, between the predictions and the actual measurements [54]. These metrics are mathematically defined by Equations (17) and (18):

Here, denotes the true value of the th sample, represents the predicted value of the th sample, denotes the number of samples, and E is the expected operator.

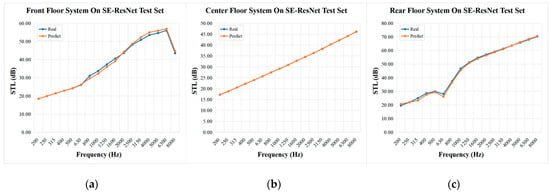

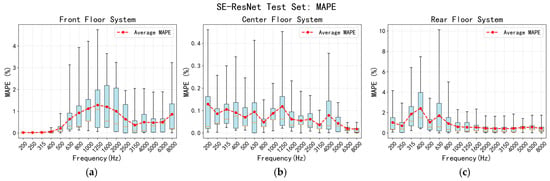

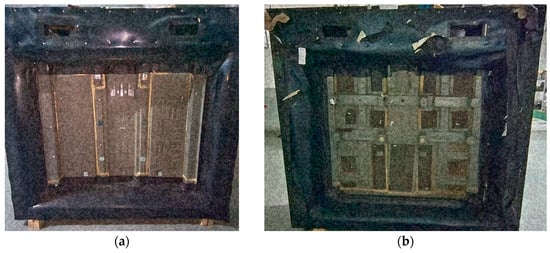

To quantify the model performance, prediction errors were systematically calculated and analyzed for all samples in the training and test sets using the aforementioned methodology. A comprehensive evaluation of the model’s performance is graphically presented in Figure 8 and Figure 9, which present the results on the training and test sets, respectively. The box plot reveals that the mean relative error of the SE-ResNet model across the 17 frequency points is concentrated between 0% and 7.8%, indicating low prediction variance. The maximum error peaks at 7.8% (400 Hz), while errors at all other frequencies remain below 7%. The overall results indicate that the SE-ResNet model effectively and reliably captures the variation patterns in the floor system’s sound insulation performance.

Figure 8.

Error statistical results of sound insulation performance prediction of floor system (training set): (a) the front floor system; (b) the middle floor system; (c) the rear floor system.

Figure 9.

Error statistical results of sound insulation performance prediction of floor system (test set): (a) the front floor system; (b) the middle floor system; (c) the rear floor system.

In addition, Table 6 presents the RMSE results on the test set. As shown, the SE-ResNet model achieves an RMSE of 0.4048 dB across the entire frequency range, signifying high predictive accuracy and strong generalization capability. Combined with the preceding analysis, these results collectively demonstrate the model’s considerable potential for engineering applications in predicting the acoustic behavior of complex vehicle structures.

Table 6.

The SE-ResNet model verifies the results on the train set and test set.

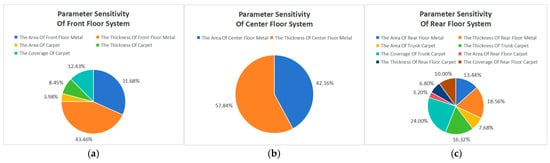

Based on the establishment of the SE-ResNet model, this paper further analyzes the parameter sensitivity of the parameters of the floor system to the system-level sound insulation performance. The results are shown in Figure 10. For the front floor system, the parameters affecting the system-level sound insulation performance mainly include the front floor metal area, the front floor metal thickness, the carpet area, the carpet thickness, and the carpet coverage. Of the five parameters, the highest sensitivity is the front floor metal thickness, and the sensitivity accounts for 43.46%. For the middle floor system, the parameters affecting the system-level sound insulation performance mainly include the two parameters of the middle floor metal area and the middle floor metal thickness. Among them, the highest sensitivity is the middle floor metal thickness, and the sensitivity accounts for 57.84%. For the rear floor system, the parameters affecting the system-level sound insulation performance mainly include the rear floor metal area, the rear floor metal thickness, the luggage carpet area, the luggage carpet thickness, the luggage carpet coverage, the rear floor carpet area, the rear floor carpet thickness, and the rear floor carpet coverage. Of the eight parameters, the highest sensitivity is the luggage carpet coverage, and the sensitivity accounts for 23.89%.

Figure 10.

Sensitivity analysis results of structural parameters of floor system: (a) the front floor system; (b) the middle floor system; (c) the rear floor system.

5. Result and Discussion

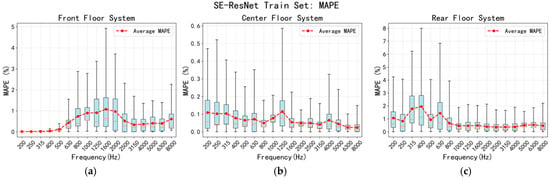

5.1. Comparison of Prediction Model

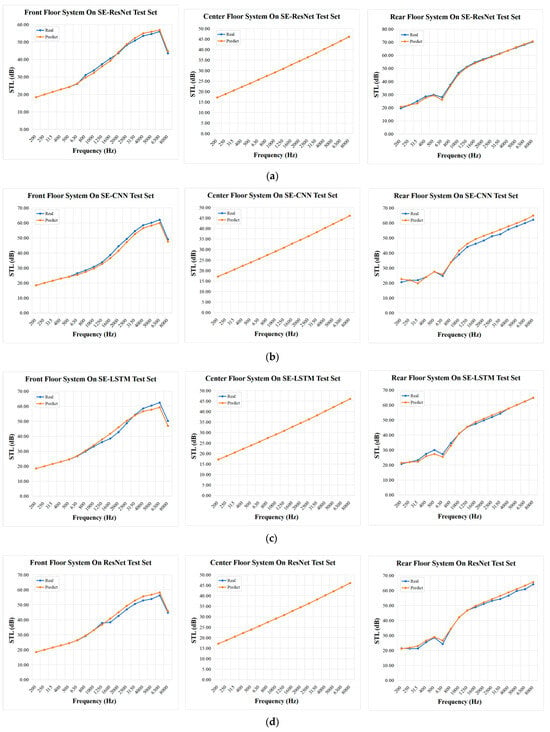

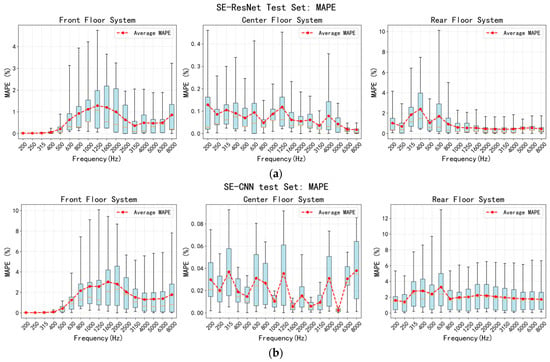

This paper extends the modeling framework beyond SE-ResNet by constructing three deep learning models: SE-CNN, SE-LSTM, and ResNet. These models are collectively applied to the prediction of sound insulation performance in vehicle floor systems, facilitating a comprehensive comparison. In order to verify the effectiveness of each model in the prediction of sound insulation performance, the prediction results of the test set of the four models at some 1/3 octave center frequency points in the range of 200–8000 Hz and the prediction results of the simulation model at some 1/3 octave center frequency points in the range of 200–8000 Hz are compared with the actual test data. The results are shown in Figure 11. The four models and simulation results can better reflect the acoustic transmission characteristics of the floor system at most frequency points, and the prediction curve is consistent with the overall trend of the measured values. However, there are some deviations between the simulation results and the experimental results. Although ResNet also has some deviations in some middle and high frequency bands, it is better than the simulation results. The SE-CNN and SE-LSTM models with a channel attention mechanism have improved prediction accuracy and stability.

Figure 11.

Comparison of the prediction results of the four models on the sound insulation performance of the vehicle floor system: (a) the SE-ResNet model; (b) the SE-CNN model; (c) the SE-LSTM model; (d) the ResNet model; (e) the simulation results.

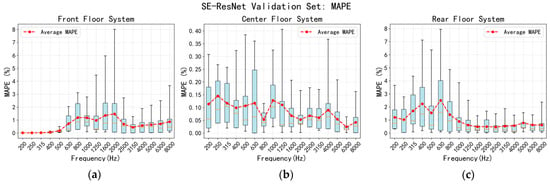

In order to quantify the prediction performance of each model, MAPE is used as the evaluation index, and the comparison results are shown in Figure 12. The SE-ResNet model results have lower MAPE values than the other three machine learning model results and simulation results, and the performance is optimal. Moreover, SE-ResNet has the lowest RMSE value and the highest CORR value, which are 0.4048 dB and 0.9996, respectively, which are significantly better than SE-CNN (0.9207 dB and 0.9979), SE-LSTM (0.4591 dB and 0.9995), and ResNet (0.6493 dB and 0.9990), as shown in Table 7. The results confirm that incorporating a channel attention mechanism into the residual structure enables more effective highlighting of salient features and filtering of non-essential information, which strengthens the model’s representational power and consequently improves its predictive performance. Compared with SE-CNN and SE-LSTM, SE-ResNet exhibits higher robustness and stability in the modeling of complex multi-layer floor systems.

Figure 12.

The accuracy comparison results of four prediction models: (a) the SE-ResNet model; (b) the SE-CNN model; (c) the SE-LSTM model; (d) the ResNet model; (e) the simulation results.

Table 7.

Prediction performance comparison of four models.

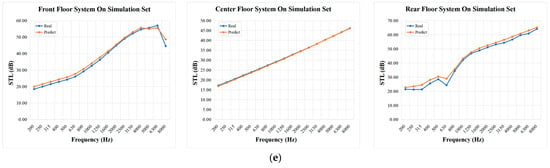

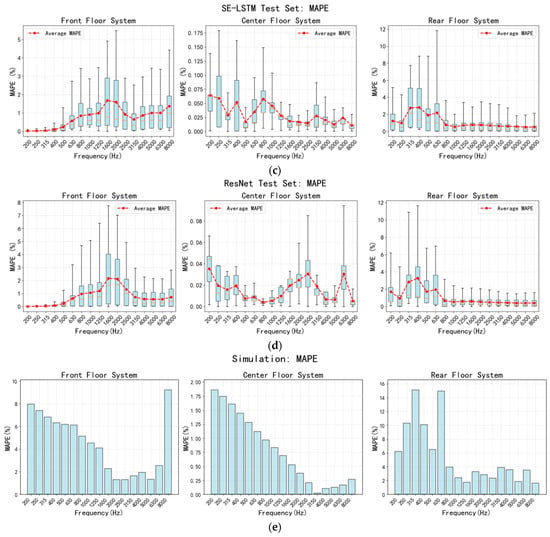

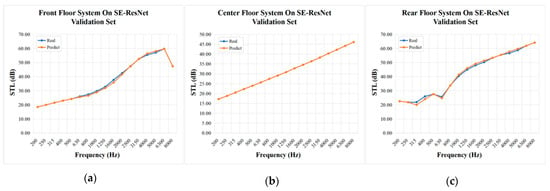

5.2. Validation of the Prediction Results

To rigorously assess the generalization capability of the SE-ResNet model, an independent verification set was constructed. This set contains sound insulation performance data and corresponding structural parameters of vehicle floor systems that were completely withheld from the model training process. The ground truth values of this set were obtained through the semi-anechoic chamber-reverberation chamber method, with the physical test specimen depicted in Figure 13. Upon feeding the validation set into the SE-ResNet model, the comparative results between predictions and measured data (Figure 14) demonstrate remarkable alignment: the predicted curve exhibits high consistency with the measured curve across most frequency points, accurately capturing the overall trend and spectral variation characteristics. Particularly in mid-to-high frequency bands, the predicted values show near-perfect overlap with experimental measurements, with only minor deviations observed at isolated low-frequency points. These findings confirm that the model not only effectively learns the feature distribution from training samples but also maintains strong predictive performance when confronted with unseen data.

Figure 13.

Floor system test specimen: (a) front; (b) the opposite.

Figure 14.

Prediction results of the SE-ResNet model on the sound insulation performance of the new floor system are as follows: (a) the results of the front floor system; (b) the results of the middle floor system; (c) the results of the rear floor system.

Statistical results of the errors for the validation sample reveal that its mean relative error across the 200–8000 Hz frequency band is 2.15%, as shown in Figure 15. It is noteworthy that the maximum error, reaching 8.10%, occurs at the 400 Hz frequency point; beyond this, the errors at all other frequency points are strictly confined within a 6% range. The overall RMSE and CORR of the validation set are only 0.4089 dB and 0.9996. The results demonstrate consistent predictive performance of the SE-ResNet model across the training, validation, and independent test sets, thereby substantiating its generalization capability and robustness. In summary, the SE-ResNet model not only shows high prediction accuracy in the existing sample data but can also maintain a stable prediction effect in the face of new samples that have not been seen before. These results collectively attest to the feasibility and effectiveness of the model for modeling the acoustic performance of complex multi-layer floor systems and pave the way for its subsequent application in engineering practice.

Figure 15.

The accuracy comparison results of SE-ResNet validation set: (a) the front floor system; (b) the middle floor system; (c) the rear floor system.

6. Conclusions

This paper develops a SE-ResNet-driven deep learning method with the goal of predicting vehicle floor system sound insulation performance and conducts a systematic assessment of its predictive effectiveness and engineering utility. As shown in the results, the prediction curve closely follows the trend of the measured results throughout the 200–8000 Hz frequency range, indicating that the model faithfully captures the system’s acoustic behavior. The overall RMSE and CORR of the test set are only 0.4048 dB and 0.9996, respectively, which are significantly improved compared to SE-CNN (0.9207 dB and 0.9979), SE-LSTM (0.4591 dB and 0.9995), and ResNet (0.6493 dB and 0.9990). The error statistics further show that the relative error of most frequency points is controlled within 6%, and the maximum error is not more than 9%, which reflects the high precision and stability of this method in the acoustic modeling of complex multi-layer structures.

Compared with the traditional simulation model, the prediction accuracy of the three machine learning models such as SE-ResNet shows significant advantages. Moreover, compared with the other three machine learning models, SE-ResNet achieves performance breakthroughs in two key designs: first, the channel attention mechanism is introduced to enhance the extraction and expression of key acoustic features, so that it can surpass the original ResNet in feature recognition ability; second, the fusion residual connection structure effectively overcomes the problem of gradient disappearance in the deep network, making it superior to SE-CNN and SE-LSTM in training stability and deep representation ability. These improvements jointly improve the capture accuracy and robustness of the model with regard to the complex acoustic response characteristics of the vehicle floor system. On the independent validation set, the prediction results of the SE-ResNet model are highly consistent with the experimental measurement data, which further proves that it has excellent generalization performance and engineering reliability in the face of unknown data.

This study has successfully constructed an efficient and high-precision deterministic prediction framework, which provides a reliable tool for the early evaluation of vehicle NVH performance and the design of an acoustic package. However, the current work mainly focuses on deterministic prediction and has not yet quantified the uncertainty of model output, such as constructing prediction intervals or evaluating the confidence of prediction results. In practical engineering applications, the uncertainty of quantitative prediction is of great significance for risk assessment and decision support, and it is also a key step to taking the model from “available” to “credible”. Therefore, in future research, we will further introduce the probabilistic modeling method to carry out uncertainty quantification and calibration analysis to improve the practicability and robustness of the model in complex engineering scenarios and promote the method to further develop in the direction of more comprehensive and reliable intelligent aided design.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.M. and J.W.; methodology, D.P. and W.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.M. and J.W.; writing—review and editing, J.W.; software, J.W.; validation, X.Y., X.L. and W.D.; investigation, D.P.; visualization, J.Y.; supervision, W.Z.; funding acquisition, X.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Major Science and Technology Project of Jilin Province and Changchun City (Grant No. 20240301010ZD), the China FAW Corporation Limited, grant number RBJ37-ZX.

Data Availability Statement

The authors do not have permission to share data.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support provided by the Institute of Energy and Power Research for the experimental research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- Huang, H.; Huang, X.; Ding, W.; Yang, M.; Yu, X.; Pang, J. Vehicle vibro-acoustical comfort optimization using a multi-objective interval analysis method. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 213, 119001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soresini, F.; Barri, D.; Ballo, F.; Manzoni, S.; Gobbi, M.; Mastinu, G. Vibration, and Harshness Countermeasures of Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor with Viscoelastic Layer Material. SAE Int. J. Veh. Dyn. Stab. NVH 2025, 9, 537–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilevicius, A.; Karpenko, M.; Krivanek, V. Research on the Noise Pollution from Different Vehicle Categories in the Urban Area. Transport 2023, 38, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpenko, M.; Prentkovskis, O.; Skackauskas, P. Analysing the impact of electric kick-scooters on drivers: Vibration and frequency transmission during the ride on different types of urban pavements. Eksploat. I Niezawodn.-Maint. Reliab. 2025, 27, 199893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.; Liu, X.; Peng, C.; Cai, K.; Yan, J.; Huang, H. Prediction of vehicle front wall sound insulation performance using Wasserstein generative adversarial network and Res-InceptionNet. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part D—J. Automob. Eng. 2025, 09544070251359709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Cheng, S.; Sun, M.; Ren, C.; Song, J.; Huang, H. Prediction of Sound Transmission Loss of Vehicle Floor System Based on 1D-Convolutional Neural Networks. Sound Vib. 2024, 58, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Dai, P.; Yin, Y.; Wang, D.; Wang, Y.; Huang, H. Predicting and optimizing pure electric vehicle road noise via a locality-sensitive hashing transformer and interval analysis. ISA Trans. 2025, 157, 556–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; He, T.; Wang, Y.; Niu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Shen, C.; Zhang, C. Research on the Influence of Door and Window Sealing on Interior Wind Noise Based on Statistical Energy Analysis. SAE Int. J. Veh. Dyn. Stab. NVH 2025, 9, 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Ma, F.; Gu, C.; Hao, Y. Highly Efficient Robust Optimization Design Method for Improving Automotive Acoustic Package Performance. SAE Int. J. Veh. Dyn. Stab. NVH 2020, 4, 291–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musser, C.T.; Manning, J.E.; Peng, G.C. Predicting Vehicle Interior Sound with Statistical Energy Analysis. Sound Vib. 2012, 46, 8–14. Available online: http://www.sandv.com/downloads/1212muss.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Wu, W.; Ding, P.; Zi, X.; Liu, B. An Acoustic Target Setting and Cascading Method for Vehicle Trim Part Design; SAE Technical Paper 2019-01-1581; SAE: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Fard, M.; Davy, J.L. Prediction of the acoustic effect of an interior trim porous material inside a rigid-walled car air cavity model. Appl. Acoust. 2020, 165, 107325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.R.; Kim, H.Y.; Jeon, J.H.; Kang, Y.J. Application of global sensitivity analysis to statistical energy analysis: Vehicle model development and transmission path contribution. Appl. Acoust. 2019, 146, 368–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmani, H.; Khalkhali, A.; Mohsenifar, A. A practical procedure for vehicle sound package design using statistical energy analysis. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part D–J. Automob. Eng. 2023, 237, 3054–3069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Huang, C.; Zhong, C.; Wang, L.; Han, H.; Deng, L. Optimization of pickup truck engine noise based on SEA and ENR methods. J. Vib. Shock. 2025, 44, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yang, W.; Cao, S.; Luo, X. Design and optimization of acoustic packages using RSM coupled with range analysis. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part D–J. Automob. Eng. 2025, 239, 4345–4361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Liu, X.; Huang, H.; Wu, Y.; Ding, W.; Yang, M. Multi-Objective Prediction and Optimization of Vehicle Acoustic Package Based on ResNet Neural Network. Sound Vib. 2023, 57, 73–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Liu, Z.; Chen, W.; Luo, T.; Sun, M.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y. A multi-dimensional driving condition recognition method for data-driven vehicle noise and vibration platform based on speed separation strategy and deep learning model. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2025, 236, 113001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Huang, X.; Ding, W.; Zhang, S.; Pang, J. Optimization of electric vehicle sound package based on LSTM with an adaptive learning rate forest and multiple-level multiple-object method. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2023, 187, 109932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, R.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, W.; Ding, W. Exploratory study on sound quality evaluation and prediction for engineering machinery cabins. Measurement 2025, 253, 117684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Yin, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhao, W.; Ding, W.; Huang, H. Evaluation and prediction of vibration comfort in engineering machinery cabs using random forest with genetic algorithm. SAE Int. J. Veh. Dyn. Stab. NVH 2024, 8, 4–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, N.; Bergen, B.; Keppens, T.; Desmet, W. A Design Space Exploration Framework for Automotive Sound Packages in the Mid-Frequency Range. In Proceedings of the SAE 2017 Noise and Vibration Conference and Exhibition, NVC 2017, Grand Rapids, MI, USA, 13–15 June 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Z.; Hu, F.; Zeng, F.; Wei, L.; Xu, Q.; Wang, J. Research of transfer path analysis based on contribution factor of sound quality. Appl. Acoust. 2021, 173, 107693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Yan, J.; Deng, J.; Liu, X.; Pan, D.; Wang, J.; Liu, P. The Prediction of Sound Insulation for the Front Wall of Pure Electric Vehicles Based on AFWL-CNN. Machines 2025, 13, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, J.; Mao, T.; Jia, W.; Jia, X.; Dai, P.; Huang, H. Prediction and Analysis of Vehicle Interior Road Noise Based on Mechanism and Data Series Modeling. Sound Vib. 2024, 58, 59–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Huang, H.; Wu, J.; Yang, M.; Ding, W. Sound quality prediction and improving of vehicle interior noise based on deep convolutional neural networks. Expert Syst. Appl. 2020, 160, 113657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Hong, S.; Seo, J.; Lee, K.; Song, Y. Correlation Analysis of Noise, Vibration, and Harshness in a Vehicle Using Driving Data Based on Big Data Analysis Technique. Sensors 2022, 22, 2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Xiong, X.; Shen, H.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y. Small-sample and imbalanced milling chatter detection: Improved GAN with attention and hybrid deep learning. Sound Vib. 2025, 59, 3502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubb, M.A.; Behrmann, M.; Egan, R.; Minshew, N.J.; Carrasco, M.; Heeger, D.J. Endogenous Spatial Attention: Evidence for Intact Functioning in Adults With Autism. Autism Res. 2025, 6, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Jiang, W. Hybrid attention based vehicle trajectory prediction. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part D—J. Automob. Eng. 2024, 238, 2281–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Bender, G.; Le, Q.V.; Ngiam, J. CondConv: Conditionally Parameterized Convolutions for Efficient Inference. In Proceedings of the 33rd Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019; pp. 1296–1307. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.B.; Li, R.X.; Yang, M.L.; Lim, T.C.; Ding, W.P. Evaluation of vehicle interior sound quality using a continuous restricted Boltzmann machine-based DBN. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2017, 84, 245–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Liu, M.; Wu, Y.; Li, Z.; Xiao, Y. A Multiscale Model Based on Squeeze-and-Excitation Network for Classifying Obstacles in Front of Vehicles in Autonomous Driving. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 14219–14228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, R.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Cheng, P.; Yonghui, L. A High Resolution Convolutional Neural Network with Squeeze and Excitation Module for Automatic Modulation Classification. China Commun. 2024, 21, 132–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, Y.; Zhang, N.; Shan, P.; Miao, L.; Sun, P.; Peng, S. PSigmoid: Improving squeeze-and-excitation block with parametric sigmoid. Appl. Intell. 2021, 51, 7427–7439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Huang, Y.; Hancock, E.R.; Wang, S.; Zhou, W. Pooling Attention-based Encoder-Decoder Network for semantic segmentation. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2021, 93, 107260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Huang, X.; Ding, W.; Yang, M.; Fan, D.; Pang, J. Uncertainty optimization of pure electric vehicle interior tire/road noise comfort based on data-driven. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2022, 165, 108300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Dai, R.; Liu, T.; Liu, J.; Yang, S.; Wang, J. Research on Vehicle Road Noise Prediction Based on AFW-LSTM. Machines 2025, 13, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Lim, T.C.; Wu, J.; Ding, W.; Pang, J. Multitarget prediction and optimization of pure electric vehicle tire/road airborne noise sound quality based on a knowledge- and data-driven method. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2023, 197, 110361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Xu, J. Engineering vibration recognition using CWT-ResNet. Sound Vib. 2025, 59, 2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafapourtehrany, M.; Rezaie, F.; Jun, C.; Heggy, E.; Bateni, S.M.; Panahi, M.; Özener, H.; Shabani, F.; Moeini, H. Mapping Post-Earthquake Landslide Susceptibility Using U-Net, VGG-16, VGG-19, and Metaheuristic Algorithms. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, T. Analysis on the Relationship between Convolutional Network Depth and Model Performance in Tree Species Classification. Forests 2022, 13, 1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh-Seol, K. Vehicle Detection Algorithm Using Super Resolution Based on Deep Residual Dense Block for Remote Sensing Images. J. Broadcast Eng. 2023, 28, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Albanie, S.; Sun, G.; Wu, E. Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2020, 42, 2011–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M. SE-ResNet based disturbance identification algorithm for microthrust measurement system. AIP Adv. 2025, 15, 065111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, D.; Dai, P.; Yang, M.; Jia, W.; Jia, X.; Huang, H. Research on maglev vibration isolation technology for vehicle road noise control. SAE Int. J. Veh. Dyn. Stab. NVH 2022, 6, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Dai, R.; Liu, T.; Wang, M.; Ying, Q.; Huang, H. Physics-informed GRU model for vehicle road noise prediction: Integrating transfer path analysis and hybrid data. Sound Vib. 2025, 59, 3143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J1400-2023; Laboratory Measurement of the Airborne Sound Barrier Performance of Flat Materials and Assemblies. SAE: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2023.

- Huang, Y.; Boerboom, M.; Wolff, K.; Bengt, J. Find Optimal Suspension Kinematics Targets for Vehicle Dynamics Using Reinforcement Learning. SAE Int. J. Veh. Dyn. Stab. NVH 2025, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marotta, R.; Strano, S.; Terzo, M.; Tordela, C. Enhancing Roll Reduction in Road Vehicles on Uneven Surfaces through the Fusion of Proportional Control and Reinforcement Learning. SAE Int. J. Veh. Dyn. Stab. NVH 2025, 9, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Wang, Y.; Wu, J.; Ding, W.; Pang, J. Prediction and optimization of pure electric vehicle tire/road structure-borne noise based on knowledge graph and multi-task ResNet. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 255, 124536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqi, M.R.; Saharkhiz, A.; Milani, S.; Fu, C.; Jazar, R.; Marzbani, H. Analysis for Comfortable Handling and Motion Sickness Minimization in Autonomous Vehicles Using Ergonomic Path Planning with Cost Function Evaluation. SAE Int. J. Connect. Autom. Veh. 2022, 5, 147–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Wu, J.; Lim, T.C.; Yang, M.; Ding, W. Pure electric vehicle nonstationary interior sound quality prediction based on deep CNNs with an adaptable learning rate tree. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2021, 148, 107170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.