Abstract

This study proposes a robust control strategy to improve the stability and reliability of grid-following inverters with LCL filters, particularly under varying disturbances and instability conditions. A detailed survey of existing control strategies is presented to identify their limitations and highlight the advantages of Internal Model-Based Control (IMC). The analytical representation of IMC has been examined by demonstrating its inherent robustness against system uncertainties and external disturbances. The research focuses on a control method for grid-following inverters operating under challenging conditions such as grid disturbances, nonlinearities, and parameter variations. The effect of these factors on inverter performance is analyzed, and corresponding mitigation strategies such as advanced filtering and adaptive control mechanisms are discussed. A simulation framework is developed to assess the effectiveness of the proposed IMC-based control approach under various grid conditions. The results confirm that IMC enhances system stability, reduces harmonic distortion, and improves dynamic response. Moreover, the outcomes highlight the potential of IMC as a robust and adaptive control solution by providing valuable evaluations for advancing inverter technologies in weak grid environments and optimizing filter designs to achieve improved power quality.

1. Introduction

The electricity grid is evolving with the increasing integration of distributed energy resources (DERs) by shifting from a centralized model to a more decentralized, flexible, and sustainable system. Inverters and power converters which facilitate the connection of DERs such as photovoltaic (PV) systems, wind turbines, energy storage systems (ESS), and combined heat and power (CHP) plants to the grid play a crucial role in this transition. While this transformation enhances grid resilience, efficiency, and sustainability, it also introduces new challenges in control and management by emphasizing the need for advanced control strategies to ensure stable and efficient operation [1].

Grid-following inverters (GFLI), which are predominantly used to interface renewable energy sources (RES) such as wind turbines and PV systems, rely on a phase-locked loop (PLL) controller to synchronize with the grid voltage. The PLL continuously tracks the phase angle and frequency of the grid, which enables the converter to inject current in alignment with the existing grid waveform. While effective under strong and stable grid conditions, this dependence on an external voltage reference makes GFLI vulnerable during disturbances. The PLL may function improperly or become unstable under weak grid conditions, voltage sags, frequency variations, or fault events, which raises the possibility of loss of synchronization (LOS). This can consequently cause transient stability problems since the converter would not be able to continue operating coherently with the grid, which could result in power oscillations, current spikes, or even converter disconnection. Power systems with a high penetration of RESs frequently use GFLIs. They introduce both active and reactive power into the electrical network by controlling the currents, but they are unable to present voltage and frequency references for the utility grid [2,3].

On the other hand, grid-forming (GFM) converters, which are commonly deployed in battery energy storage systems (BESS), operate on fundamentally different principles. Rather than tracking the grid voltage, GFM converters actively establish and regulate their own voltage and frequency, effectively behaving as controllable voltage sources. This intrinsic capability allows them to provide virtual inertia and damping, supporting system frequency and voltage during transient events. As a result, GFM converters are inherently more robust against grid disturbances and can partially mitigate the risk of LOS, especially in low-inertia or weak grids with high penetration of inverter-based resources. Their ability to sustain grid voltage and frequency also contributes to improved transient stability that makes GFM-based BESS a key enabler for maintaining reliable operation in future power systems dominated by renewable generation [4,5].

GFLI control is a popular approach among grid-connected systems in modern power generation systems, particularly in renewable energy applications. It is recommended due to its good adaptability to various grid conditions and operating requirements, high energy conversion efficiency, and relatively simple control structure. The GFLI control is now a widely used technique for integrating inverter-based resources with traditional power systems due to these characteristics. However, as the use of power electronic-interfaced generation increases, the overall system inertia significantly decreases since these converters do not provide rotational inertia by default. At the same time, the short-circuit ratio (SCR) at the point of common coupling (PCC) significantly falls, which indicates a weaker grid at the inverter connection point. This reduction in SCR causes weak grid characteristics such as low voltage stiffness and a higher sensitivity to disturbances. Under such situations, the performance of GFLI may deteriorate and make it more prone to synchronization challenges, control interactions, and stability issues, particularly during faults or transient occurrences [4,6].

Although both GFL and GFM control strategies are widely used, each is subject to small-signal stability issues under certain grid conditions. The strength of the power grid is commonly quantified by the SCR, which reflects the ability of the grid to maintain voltage and frequency in the presence of disturbances. According to IEEE Standard 1204-1997, a grid with an SCR below two is described as very weak, whereas a grid with an SCR greater than three is generally regarded as strong [7]. In weak grid conditions where the SCR is below three, GFL-controlled inverters are particularly vulnerable to instability. This is primarily due to the PLL, which introduces an asymmetric positive feedback mechanism between the grid voltage and the converter control dynamics. When the SCR is low, this feedback can significantly degrade the damping of the system, which leads to oscillations and eventual loss of stability [4]. Under these conditions, the PLL introduces a negative resistance component into the output impedance of the inverter that destabilizes the system by amplifying small disturbances. This instability can lead to oscillations or voltage fluctuations, which makes it crucial to design robust control mechanisms for enhancing the inverter’s ability to operate reliably under weak grid conditions [8].

Advanced control techniques are essential for improving the performance of GFLIs to address stability challenges in weak grids. Internal model-based controllers (IMCs) offer a promising solution by utilizing mathematical models of grid and inverter dynamics to ensure stability and robustness. These controllers dynamically adjust inverter responses to compensate for PLL-induced instability. Moreover, adaptive control techniques further enhance inverter resilience by continuously modifying control parameters based on real-time grid measurements that allow stable operation under varying conditions. Inverters that are controlled by integrating virtual synchronous machines (VSMs), IMCs, model predictive control (MPC), and adaptive control methods can effectively mitigate instability, improve reliability, and optimize the performance of RESs in weak grid environments [9,10,11].

This study focuses on implementing a robust control strategy to enhance the stability and reliability of grid-connected inverters equipped with LCL filters, particularly under various disturbances and instability challenges. The primary objective of the proposed study is to improve inverter capabilities to maintain stable operation while ensuring effective power regulation, even in dynamic and weak grid conditions. The presented study outlines several core development objectives focused on model-based control strategies to accomplish this aim. The proposed control approach leverages IMC as its foundation by integrating additional damping mechanisms to mitigate resonance issues associated with the LCL filter. This configuration enables accurate current regulation while efficiently suppressing undesired oscillations that would otherwise threaten system performance. The proposed IMC-based scheme is designed to provide additional ancillary services beyond its core function of regulating power flow and injecting power into the grid. These include voltage and frequency support, harmonic compensation, and enhanced disturbance rejection, which contribute to improved grid stability and power quality. The key contributions of this paper can be summarized as follows:

- −

- A reliable IMC is developed to ensure stable performance of GFLIs with improved adaptability to various grid conditions, including weak and highly fluctuating grids.

- −

- The proposed control approach enables independent regulation of active and reactive power.

- −

- Passive damping techniques are integrated into the LCL filter design to effectively reduce resonance.

- −

- The control strategy maintains high power quality by minimizing total harmonic distortion (THD) that ensures the injected current and output voltage of the inverter comply with grid standards.

These contributions present a comprehensive approach to improving the stability, efficiency, and power quality of GFLIs that make them suitable for renewable energy and distributed generation applications. The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides a comprehensive review of the current control methods employed in inverters within distributed generation systems. The system description and IMC design are given in Section 3. The proposed control strategy is assessed through simulation in Section 4, where various test scenarios, case studies, and results, along with their analyses, are provided in Section 5. The discussions about the proposed IMC-based GFLI design and its reliability are presented in Section 6, followed by Section 7, which draws the concluding remarks.

2. Literature Survey

The control strategies for grid-connected systems have evolved from simple single-loop control to more advanced dual- or multiple-loop systems that manage both voltage and current. The current control loop is critical for maintaining power quality by regulating the output current. A commonly used method for current regulation in inverters is the proportional-integral (PI) controller, which helps the output current align with a reference signal based on the desired power transfer to the grid. While PI controllers are effective under balanced grid conditions, they struggle in more complex and unbalanced environments. The voltage fluctuations can degrade power quality by leading to higher harmonic distortion and reducing the efficiency of energy transfer. Many control methods have been developed to overcome the limitations of conventional PI controllers in grid-connected systems. These methods provide more robust and adaptive solutions for maintaining power quality, especially in the presence of unbalanced grid conditions, harmonics, and fluctuating parameters. Addressing these issues to ensure stable and secure integration of renewable energy into the grid is recognized as a complex task, and it is widely accepted that inverters must be equipped with robust control algorithms to manage these challenges effectively [1,12,13]. In addition to the control methods, the filter alignments based on LC and LCL configurations are precisely used to reduce current harmonics in voltage source inverters (VSIs), which facilitate the transfer of energy from DERs to the grid. The LCL filters are gaining popularity due to their superior performance over simpler L or LC filters. These filters enable inverters to function efficiently at lower switching frequencies that offer better harmonic attenuation, and reduce grid current ripple, while improving the quality of power fed into the grid. Despite their advantages in harmonic reduction, LCL filter-based systems require more complex control strategies compared to L or LC filters. Advanced control methods are needed to handle resonance effects, maintain system stability, and ensure optimal performance [14,15,16,17].

The Lyapunov-based control strategies are highly effective for addressing the stability issues introduced by LCL filters in grid-connected systems, particularly in dynamic grid environments. In the context of inverters, the goal is to design a control law that ensures the system state converges to a stable equilibrium and tracks the parameters even under varying and uncertain grid conditions. Although the LCL filters provide better harmonic attenuation and improve power quality, they introduce additional complexities into the system due to their higher-order dynamics. Specifically, the introduction of two additional poles in the system transfer function increases the risk of resonance, which can destabilize the reliable operation of the inverter. This is particularly problematic when grid conditions fluctuate, as these variations can lead to instability in systems using simpler control methods. In such cases, traditional control strategies may fail to maintain stable operation by resulting in poor power quality and potential grid destabilization, as discussed in the literature [11,17,18,19,20].

The IMC approach presented in this study integrates the benefits of both feedforward and feedback control strategies. This hybrid method not only suggests enhanced performance but also ensures better response, which makes it suitable for complex systems like GFLIs. A key advantage of IMC is its simple design, which requires only a single tuning parameter. This parameter is essential as it optimally balances closed-loop performance with system robustness that allows the controller to compensate for any inaccuracies or uncertainties in the system model. This characteristic makes IMC particularly advantageous in applications where precise model accuracy is not often achievable. The key feature of the IMC technique is to control and reduce inaccuracies between the model and actual system behaviour, which demands continuous and reliable performance under dynamic situations [21,22,23].

The literature review shows that model-based control algorithms, especially IMC, have not been widely explored in grid-connected inverters. Since their introduction, only a few studies have applied IMC methods. For example, an IMC algorithm was successfully used for current control in an RL filter-based VSI, and a similar approach was later adopted for voltage regulation in the islanded operation of generators in 2014 [24]. Moreover, a few other significant studies have specifically focused on examining the stability conditions of grid-connected inverters, two of which explore three-phase systems and one that addresses a single-phase system [25,26]. The model-based current controllers offer significant advantages compared to traditional feedback control strategies that rely on PI algorithms. These controllers improve the damping ratios of critical eigenvalues, provide better resistance to changes in system parameters, and achieve faster response times. Additionally, they effectively minimize transient overshoot and undershoot in both voltage and current, which makes them a more robust and reliable solution for ensuring stable operation in grid-connected inverters. The studies conducted so far reveal that the application of model-based control algorithms, particularly in the context of small-signal analysis, is relatively limited. It is important to note that the IMC method significantly differs from traditional PI and PID feedback control strategies [20,27].

The IMC approach is based on a well-defined model of the system, which provides a straightforward and efficient design with a single tuning parameter that balances system performance and robustness. The proposed controller provides a more efficient and reliable solution by directly incorporating the system model into the controller, particularly in grid-connected inverter applications where real-time performance and stability are critical.

3. Modelling of the System and Design of the Controller

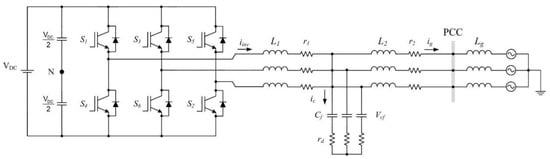

The typical configuration of a GFLI with an LCL filter is illustrated in Figure 1. The output filter of this configuration comprises three main components per phase: the inverter-side inductance (L1), the filter capacitance (Cf), and the grid-side inductance (L2). These elements collectively form the LCL filter, which is widely used to mitigate switching harmonics and improve the quality of the injected current into the grid. The LCL filter improves system performance and assures grid compliance by reducing the high-frequency components produced by the pulse-width modulation (PWM) switching. A single-phase equivalent circuit of the GFLI model is presented in Figure 2 using the stationary αβ coordinate frame to better understand the dynamic behaviour of this system. This transformation simplifies the analysis by representing the three-phase system in a two-dimensional plane, which aids in designing control strategies and analyzing harmonic effects. The traditional two-level three-phase topology is the basis for the operation of the GFLI. In this topology, each phase-leg of the inverter comprises two switching devices. The arrangement of these switching devices is specified as follows: S1 and S4 for one phase, S3 and S6 for the second phase, and S5 and S2 for the third phase, as depicted in Figure 1. These switches are controlled in a complementary manner to ensure proper operation and to prevent short circuits in the DC link. The switching states of the inverter are determined by the gating signals Sa, Sb, and Sc, which control the on/off states of the respective switches. The inverter generates the desired AC output voltage waveform by modulating these signals using a control scheme such as space vector pulse-width modulation (SVPWM) or sinusoidal PWM [28,29].

Figure 1.

The GFLI model with the LCL filter.

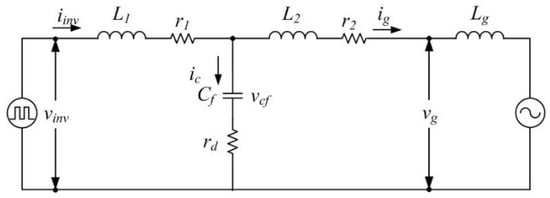

Figure 2.

Equivalent circuit of the GFLI with LCL filter in the stationary (αβ) frame.

The vectoral representation of switching states can be given as follows:

where . Each switching state determines a specific set of phase voltages for the inverter relative to the negative busbar (vaN, vbN, and vcN). The output voltage space vectors generated by the inverter are defined by:

where vaN, vbN, and vcN are the phase-to-neutral voltages of the inverter.

In analytical design studies, a discrete-time state-space model of the GFLI is developed to serve as the internal model for the proposed model-based controllers. This model mathematically represents the dynamic behaviour of the system by aiding in the design and implementation of advanced control strategies. The state-space model is derived from the differential equations that describe the interactions between the system components of the LCL filter. These equations define the voltage–current relationships governing the system operation. The equivalent circuit shown in Figure 2 is used to construct this model. This representation simplifies the system into a single-phase equivalent form in the stationary αβ reference frame, which makes it more suitable for control analysis and digital implementation. A discrete-time model is obtained by discretizing the continuous-time equations, which is essential for digital controllers operating in sampled-data systems. This discrete-time state-space representation serves as the basis for model-based control approaches, such as predictive control or state feedback control, ensuring precise voltage and current regulation while maintaining grid stability and compliance.

The GFLI current iinv, grid current ig, capacitor voltage vcf, and grid voltage vg are defined as the state parameters. The inverter voltage vinv is defined as a function of the voltage across L1, the capacitor voltage vcf, and the damping resistance rd voltage as given in Equation (3), while the grid voltage vg is defined in Equation (4).

The state variables are identified based on the inverter and grid voltage Equations given in (3) and (4) are defined as follows:

The state-space model of GFLI in continuous time can be described as seen below.

where the state vectors are x(t) = [iinv vcf]T and u(t) = [vinv ig]T. The matrices A and B are given below as follows [20,27,30]:

3.1. Design and Dynamics Analysis of LCL Filter

The power flow of the inverter can be effectively regulated through appropriate control methods that ensure stable and efficient grid interaction while maintaining power quality standards. Among the various filtering solutions, the LCL filter is the most advanced and effective configuration due to its third-order structure, which significantly enhances harmonic attenuation. Unlike the single-inductor filter, the LCL filter provides a much higher attenuation rate of 60 dB per decade, which efficiently reduces both current and voltage harmonics. This performance allows for the use of smaller inductors, which not only minimizes power losses but also reduces overall system size and cost compared to L and LC filters. The complexity of LCL filter design introduces challenges, particularly in preventing resonance, which can lead to instability at certain frequencies. The advanced control strategies, such as active damping techniques, are required to ensure stable operation while maximizing the filter efficiency in suppressing high-frequency harmonics [31,32]. The design procedure of the LCL filter used in the proposed modelling studies is performed by referring to the cited publications and application notes in the literature. The following expressions and control parameters are improved regarding the parameters and network presented in Figure 2. The filter capacitor Cf is determined according to the design base values that are defined as given below.

where VLL is the phase (line-to-line) voltage of the grid, Zb is the base impedance, and ωg = 2πfg is the angular frequency of the grid. The filter capacitance is typically chosen as a percentage of the base capacitance value, Cb, which represents the nominal capacitance of the system. The filter capacitance is carefully selected based on the maximum allowable power variation observed by the grid to maintain stability and achieve effective filtering. This variation is typically restricted to a range of 1% to 5% to prevent excessive reactive power injection and ensure compliance with grid regulations. The proper tuning of the capacitance helps balance the harmonic attenuation and system stability while avoiding undesirable resonance effects that could compromise the inverter’s performance. The filter capacitance can be calculated as Cf = 0.05 Cb to effectively smooth out voltage and current fluctuations, which ensures that harmonic distortion remains within acceptable limits by setting the maximum power variation at 5%. At low frequencies, the LCL filter functions similarly to a single inductor with a total inductance, Ldc, which is the sum of the inductances of the inverter-side inductor L1 and the grid-side inductor L2 in Figure 2. This total inductance is expressed as follows:

In this low-frequency range, the current through the filter capacitor Cf is considered negligible in comparison to the current through the inductors, meaning the capacitors mainly filter high-frequency components, while the inductors dominate at lower frequencies. There is an optimal relationship between L1 and L2 that minimizes the voltage drop at the fundamental frequency while maximizing the filter capability to reduce higher-frequency harmonics. This relationship is expressed by representing L1 and L2 as percentages of the total inductance Ldc and L2 using a variable α (where ). The inductances are then given by:

The α parameter determines how the total inductance is split between the inverter-side and grid-side inductors. The filter performance can be optimized by balancing the minimization of losses (voltage drop at fundamental frequency) and the maximization of harmonic attenuation by adjusting the α parameter. The LCL resonant circuit comprises the components L1, L2, and Cf, all in parallel, which together determine the resonant frequency of the filter. The resonant frequency ωr can be calculated as follows:

To simplify the analysis, the equivalent inductance Leq, which sets the resonant frequency, can be defined as the parallel combination of L1 and L2.

The minimum equivalent inductance Leq occurs when L1 = L2 = 0.5 L2dc, meaning the two inductances are equal, which results in the most efficient harmonic attenuation at the resonant frequency. To design the filter, the total inductance Ldc is often chosen as 10% of the base inductance value Lb based on empirical data, and the individual inductances L1 and L2 can be determined as referring to this data. This configuration balances the filtering performance and minimizes voltage drop across the inductors while ensuring effective attenuation of high-frequency harmonics [31,33].

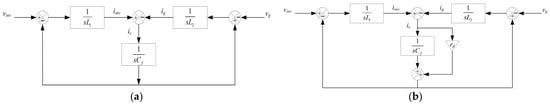

Figure 3 illustrates a damped filter configuration, where a damping resistor is connected in series with the filter capacitor as shown in Figure 2. This method is part of passive damping, which reduces resonance but introduces power losses due to a physical resistor. The s-domain block diagram in Figure 3 further demonstrates that the same damping effect can be achieved within the control scheme of an ideal LCL filter by incorporating a virtual gain component which emulates the damping resistor “rd” in Figure 2. This approach, known as active damping, relies on modifying the control to simulate the resistor effect. For active damping, the filter capacitor currents need to be measured. This requires additional analogue inputs/outputs, specifically, three measurements for a three-phase system or only two for balanced three-phase currents. The state equations that describe the filter behaviour in the s-domain are based on the configuration shown in Figure 3a without a damping resistor as follows:

Figure 3.

The s-domain block diagram of the LCL filter at the grid-connected inverter: (a) without a damping resistor; (b) with a damping resistor.

The voltage and current transfer functions of the ideal LCL filter in this configuration are as follows:

The voltage and current transfer functions of an LCL filter with a damping resistor, shown in Figure 3b, consider the additional resistor placed in series with the capacitor, which is part of the passive damping approach. The damping resistor, rd, helps suppress resonance at the LCL filter resonant frequency, but it also modifies the transfer functions of the system, as given below [31,32,33]:

The parameter definition of inductors along the LCL filter is dependent on the current ripple rates and related limits. The maximum current ripple ΔILmax at the output of a GFLI can be derived from the characteristics of the switching process and the filter inductance. The maximum current ripple derived from the parameters is expressed below.

where m is the modulation index of the modulator, and fsw is the switching frequency. The peak-to-peak current ripple depends on the product of m (1 − m), which means that the ripple is minimized at m = 0 or m = 1 and maximized when m = 0.5;

A 10% ripple of the rated current for the design parameters is given by ΔILmax = 0.01 Imax, where the L1 value is derived as in Equation (25) [31];

Determining the value of the grid-side inductance (L2) in an LCL filter of a grid-connected inverter involves balancing several factors, including resonance frequency, harmonic attenuation, system stability, and power quality requirements. The process typically considers the overall inductance of the filter, the grid requirements, and the switching characteristics. Equations given in (11)–(14) are essential to determine the exact L2 value after selecting the L1. To avoid harmonic amplification near the switching frequency of the inverter, the resonant frequency, fres, is generally chosen to be within a specific range

which ensures that the resonance occurs at a frequency high enough to avoid interaction with the grid frequency but low enough to avoid amplifying switching harmonics. The damping resistor, rd, placed in series with the filter capacitor, attenuates part of the ripple around the switching frequency to avoid resonance. The value of the damping resistor is typically set as a fraction of the impedance of the capacitor at the resonant frequency. Specifically, rd should be one-third of the capacitor impedance at the resonant frequency, as expressed in:

The damping resistor, rd, is a critical element in an LCL filter for a grid-connected inverter, as it reduces the impact of resonance without adding significant losses to the system. By carefully selecting rd, based on the resonant frequency and capacitance, the system can achieve effective harmonic attenuation while maintaining stability. After determining the equations of GFLI and LCL filter based on the specified principles, modelling studies were carried out using MATLAB 2023a and Simulink to design the GFLI with the IMC system.

3.2. Design Studies of IMC and Its Control Objectives

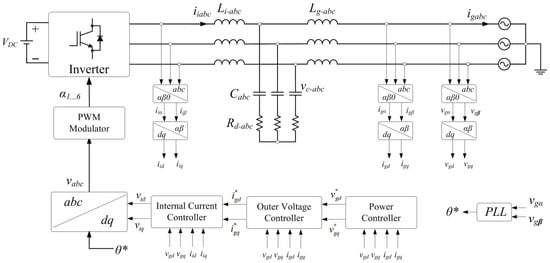

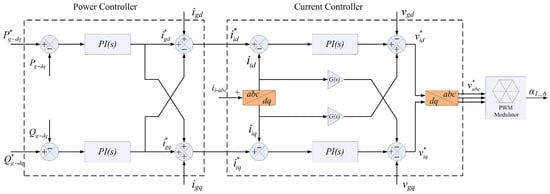

The IMC technique requires mathematical models of the system to be produced for the controller. The IMC of GFLI is designed to enhance performance, stability, and power quality by leveraging precise mathematical models of the inverter and its interactions with the grid. This approach allows the controller to predict system behaviour accurately and apply corrections proactively to ensure robust operation even under dynamic grid conditions. As part of this work, the schematic representation of the GFLI controlled using the proposed IMC algorithm was developed, and the corresponding control block diagrams are illustrated in Figure 4. The IMC algorithm is designed with two fundamental internal controllers responsible for power control, relying on voltage and current controllers. Each of these controllers operates based on the model parameters generated from the state space equations of the inverter, filter, and grid. The simplified interconnection network of the grid-connected inverter is obtained by referring to the equivalent circuit given in Figure 2. The filter branch can be expressed with a single inductor L, which is the sum of L1 and L2, while the resistance comprises the grid-side resistance.

Figure 4.

The grid-connected LCL inverter and model-based controllers.

The GFLI shown in Figure 4 comprises a voltage source inverter supplied by a DC link and connected to the utility grid through an LCL filter. The DC source (VDC) provides the input energy, which is converted into three-phase AC power by the inverter PWM. The voltages and currents are measured at both the inverter and grid sides to enable accurate control. These three-phase signals are first transformed from the stationary (abc) frame to the αβ frame and then to the synchronously rotating dq frame. The dq transformation allows decoupled control of active and reactive power components, which is essential for grid-following operation. The transformation relies on the grid phase angle, which is provided by a PLL controller. The PLL plays a critical role in synchronizing the inverter with the grid. The PLL estimates the grid phase angle (θ*) and frequency by using the measured grid voltages in the αβ frame. This information aligns the inverter control reference frame with the grid voltage, ensuring that the injected currents remain synchronized with the grid. As a result, the inverter operates as a current-controlled source that follows the grid voltage rather than establishing it. The control system adopts a cascaded structure with multiple hierarchical control loops.

At the outermost level, a power controller regulates the active and reactive power exchanged between the inverter and the grid. The outer power control loop is responsible for regulating the active and reactive power exchanged between the inverter and the grid. In this loop, the measured active power, P, and reactive power, Q, are driven to track their respective reference values, P* and Q*. This loop runs at a low bandwidth because power dynamics are comparatively slow and significantly affected by grid conditions. The primary objective of the power control loop is to determine the desired operating point of the inverter in terms of power injection, based on grid requirements, energy management methods, or higher-level supervisory commands.

The power controller generates reference voltage signals in the dq frame, which reflect the desired power injection objectives based on the measured grid-side voltages and currents. These voltage references are processed by an outer voltage control loop, which compares the reference (vgd* and vgq*) and measured grid voltages (vgd and vgq), and generates corresponding current references, igd* and igq*. The purpose of this loop is to ensure proper voltage regulation at the point of connection while providing smooth setpoints for the inner current control loop. It connects the slower power dynamics with the faster current dynamics in this way. The inner current controller forms the fastest control loop in the system. It tracks the reference currents by regulating the inverter-side currents (igd and igq) in the dq frame. The feedforward and decoupling terms are typically included to compensate for cross-coupling effects and grid voltage disturbances, thereby improving dynamic response and stability. The output of this controller is a set of reference inverter voltages (vid and viq) in the dq frame. Afterwards, the reference voltages are transformed back into the abc frame and fed to the PWM modulator, which generates the gating signals for the inverter switches. The GFLI achieves accurate power regulation while meeting grid standards by injecting regulated currents into the grid in synchronization with the grid voltage.

The GFLI is controlled in the synchronous reference frame aligned with the grid voltage vector through the PLL. Under this alignment, vgq ≈ 0, enabling decoupled control of active and reactive power.

Assuming grid voltage orientation (vgq = 0), the instantaneous active and reactive power exchanged between the inverter and the grid are given by:

Thus, the power references obtained at the power and voltage control blocks are converted into current references by substituting (vgq = 0) into Equation (28), respectively.

The internal current loop seen in Figure 4 tracks igd* and igq*, while the outer loops generate these references based on power and voltage objectives. The Kirchhoff’s Voltage Law (KVL) is applied in the Clarke and Park transformations to the natural abc reference frame equations to obtain the two orthogonal axes of the stationary reference frame (α, β), and then the d- and q-axis rotating reference frame components, respectively. The transformation equations are described as follows:

where Viabc denotes the output voltage of the inverter in the natural reference frame, while the stationary reference frame and the rotating reference frame coefficients are presented as Viαβ and Vidq, respectively. Similarly, iiabc is the inverter current, and Vgabc is the grid-side voltage. The stationary reference frame current of the inverter, iiαβ, is transformed to the rotating reference frame aαβ = ejθ transformation. The d- and q-axis components of the inverter voltage in the rotating reference frame are expressed as shown in Equation (33), derived from the complex equation adq = ad + jaq. The inverter-side current dynamics in the synchronous frame are described by:

where Li and Ri denote the inverter-side filter inductance and resistance, respectively. The PLL may become unstable and experience severe coupling effects under weak-grid conditions (low SCR) due to voltage disturbances and phase changes caused by the grid impedance. The simplified plant model is obtained by compensating the cross-coupling terms in Equation (33) using feedforward decoupling to enable robust controller synthesis.

The internal model of the plant is chosen as the nominal inverter current model, as given in Equation (34), which captures the dominant dynamics while maintaining robustness against grid impedance uncertainty caused by low SCR conditions. The small-signal stability of grid-following inverters is strongly influenced by the strength of the grid, which is commonly quantified by the SCR at PCC. The SCR is defined as follows:

where is the short-circuit capacity of the grid at the PCC, and is the rated power of the inverter. A low SCR (<3) corresponds to a weak grid with high grid impedance, whereas a high SCR indicates a stiff grid [4].

The block diagram of the proposed cascaded IMC-based power regulator, consisting of an internal current control algorithm, is presented in Figure 5. The cascaded voltage controller-based IMC model has been proposed in [34]. In the literature review, it is also seen that similar model-based control algorithms were developed by utilizing PI and PID controllers, whereas cascaded controller models have been considered [35,36]. The tuning parameters of the PI controllers that are optimized for regulating the desired active and reactive power adjust the power values through the coefficients KP-P, KI-P for active power and KP-Q, KI-Q for reactive power, respectively. Similarly, the d- and q-axis components of the inverter current are controlled using the coefficients KP-Cd, KI-Cd for the d-axis and KP-Cq, KI-Cq for the q-axis, as illustrated in the PI controller blocks in Figure 5. The integrator outputs in the general structure of the stepwise controller seen here are selected as the state variables of the system, and thus, the inputs are converted into derivatives of the state variables. The overall objective of this structure is to regulate the active and reactive power exchanged with the grid while ensuring fast and stable current dynamics. The controller is composed of two main subsystems: the power controller (outer loop) and the current controller (inner loop), which are followed by coordinate transformations and PWM.

Figure 5.

The model-based controllers of the GFLI.

The power controller constitutes the outer control loop and operates on slow dynamics. It receives the reference active and reactive powers, P*g-dq and Q*g-dq, and compares them with the measured grid-side active and reactive powers, Pg-dq and Qg-dq. The resulting power errors are processed by two independent PI controllers. The outputs of these PI controllers generate preliminary current reference components in the dq frame, denoted as i*gd and i*gq, which correspond to the desired active and reactive power injection, respectively.

The cross-coupling between the d- and q-axis is accounted for through the interconnection shown between the two current reference paths for improving the decoupling and steady-state accuracy. These grid-side current references are then adjusted using feedback of the measured grid currents igd and igq that yield the inverter-side current references i*id and i*iq. This transition assures that grid-side objectives are consistent with inverter-side operation, especially when filter dynamics and grid impedance are present. The inner current control loop uses the generated current references as its inputs.

The current controller represents the inner and fastest control loop in the system. The measured inverter-side three-phase currents ii-abc are first transformed from the abc frame to the dq frame using the synchronous reference angle provided by the PLL. The d- and q-axis current errors, which are obtained by comparing i*id with iid and i*iq with iiq, are each processed by dedicated PI controllers. These controllers are designed to provide rapid tracking of the reference currents and strong disturbance rejection. The feedforward compensation terms denoted by the blocks G(s) are incorporated in both axes to enhance dynamic performance and decouple the d- and q-axis dynamics. The grid voltage disturbances and cross-coupling effects caused by the filter inductance and grid voltage components vgd and vgq are compensated for by these terms. The reference inverter voltages v*id and v*iq are produced by the feedforward compensation and the outputs of the PI controllers. Consequently, the reference voltages in the dq frame are transformed back into the three-phase abc frame to produce v*abc. These voltage references are applied to the PWM modulator, which generates the switching signals for the inverter power switches. Through this coordinated control structure, the inverter accurately follows the grid voltage phase and frequency while injecting the commanded active and reactive power with fast current regulation and enhanced stability, particularly under weak-grid conditions.

The IMC comprises:

where F(s) is a low-pass filter introduced to ensure realizability and robustness. A first-order filter is selected as follows:

Substituting Equations (34) and (37) into Equation (36) yields:

The parameter λ directly determines the closed-loop bandwidth and plays a crucial role in maintaining stability under weak-grid conditions. Therefore, the IMC filter parameter λ is selected to balance dynamic performance and robustness:

where Li/Ri is the electrical time constant of the inverter-side filter. The IMC in Equation (38) can be expressed in an equivalent PI form as follows:

These expressions show that instead of being achieved through heuristic or trial-and-error adjustment, the PI parameters provided in Table 1 are analytically derived from the IMC formulation. The parameters are calculated in m-file iterations under the MATLAB 2023a environment. The chosen gains ensure lower sensitivity to grid impedance and PLL interactions, improved robustness under weak-grid (low SCR) situations, and consistent dynamic performance across operating points. The proposed IMC-based PI controller offers a methodical and physically comprehensible tuning technique for grid-following inverters operating in low-inertia, weak power grids.

Table 1.

IMC-based PI controller parameters for the inner current control loop.

In simulation modelling of proposed controller studies, the analytical designs are implemented regarding the state-space equations of the inverter, filter, and grid model. The analytical model is developed in a real-time simulation environment using MATLAB 2023a and Simulink software.

4. Simulation Setup and Modelling Studies

The simulation study is conducted using MATLAB/Simulink, which is a widely used software environment for modelling and analyzing power systems and control algorithms. The flexibility of this platform allows for accurate modelling of the GFLI and its associated control schemes. The proposed IMC is implemented using discrete-time blocks to reflect its real-time operability in hardware. The simulation setup replicates real-world operational conditions while maintaining the adaptability needed to test diverse scenarios, ensuring a reliable assessment of the proposed system performance.

4.1. Simulation Environment

The simulation model represents a GFLI system that includes a full-bridge inverter, an LCL filter for harmonic attenuation, and a balanced three-phase grid complying with the block diagrams presented in Figure 4. The modulator of the GFLI is modelled with sinusoidal pulse-width modulation (SPWM), which transforms the control signals into gate pulses for the switching devices. The LCL filter ensures that the switching harmonics produced by the inverter are mitigated, and the quality of the current injected into the grid is improved. The grid is modelled with nominal voltage and frequency, with options to introduce disturbances such as voltage sags, harmonics, and frequency deviations for stress testing the system. The control structure comprises current controllers in the dq-reference frame, where separate PI controllers regulate the d- and q-axis currents. Decoupling terms are integrated into the control design to handle the cross-coupling effects between the axes for ensuring precise active and reactive power control. The parameters of the simulation model are carefully selected to reflect realistic operational scenarios. The rated power of GFLI, DC-link voltage, and switching frequency are aligned with typical values seen in medium-sized grid-tied systems. For the LCL filter, the inductance (Lf) and capacitance (Cf) are designed to achieve an optimal trade-off between harmonic attenuation and system stability. Resonance-damping techniques are employed to address potential oscillations at the filter resonant frequency. The grid model operates at a nominal voltage and frequency of 50 Hz with provisions to introduce varying short-circuit ratios to mimic weak or strong grid conditions. These parameter settings presented in Table 2 ensure that the simulation is both representative of practical applications and robust enough to accommodate different operating scenarios.

Table 2.

Parameters of the GFLI.

4.1.1. LCL Filter Modelling

The LCL filter plays a crucial role in the designed grid-connected inverter system since it acts as a buffer to attenuate high-frequency switching harmonics and ensures the delivery of suitable current to the grid. Analyzing the transfer function presents crucial insights into the frequency-domain characteristics of the filter and the impact of damping on its overall performance. The fundamental transfer function of the LCL filter is defined as HLCL = ig/vi, where ig represents the grid-side current and vi the inverter voltage. This analysis assumes that the grid voltage (vg) acts as an ideal voltage source that can absorb harmonic frequencies. When operating under current-controlled conditions, where vg = 0, the transfer function of the undamped LCL filter is expressed as [32,33].

Here, Li and Lg denote the inverter-side and grid-side inductances, respectively, while Cf represents the filter capacitance. The absence of damping leads to a sharp gain spike at the filter resonant frequency, which can compromise system stability if not mitigated. To suppress this resonance, a damping resistance (Rf) is introduced in series with the capacitor (Cf) that modifies the transfer function as follows:

The inclusion of the term Cf Rf s in the numerator introduces damping factors that effectively reduce the gain spike. This modification not only smooths the response but also enhances the overall stability of the filter by mitigating the high-frequency resonant behaviour.

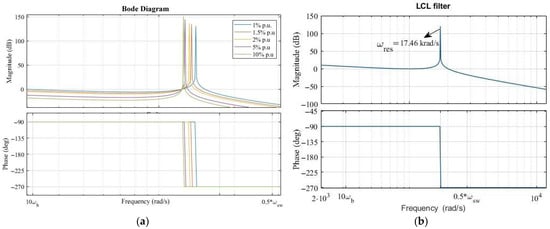

An examination of the frequency response of the LCL filter through Bode plots presented in Figure 6 shows significant improvements with damping. The filter exhibits a phase shift that approaches −270° at higher frequencies and an apparent gain peak at its resonant frequency when there is no suppression. This tendency is undesirable since it amplifies disturbances and reduces control loop efficiency. On the other hand, adding damping results in a smoother response and removes the gain spike. The phase shift is restricted to −180° at higher frequencies, which improves the stability margins of the system and ensures better performance, as shown in Figure 6a, which examines the impact of the grid-side inductor configuration.

Figure 6.

Resonance frequency responses of LCL filter: (a) response to the change in grid-side inductor; (b) response of the designed filter (ωres = 17.46 krad/s).

The Bode analysis also highlights the importance of limiting the closed-loop bandwidth of the inverter system. To maintain stability, the bandwidth should be limited to below 1000 Hz, where the phase shift in the LCL filter is approximately −90°. Exceeding this range may lead to excessive phase lag, which could compromise system stability and degrade the performance of current regulations. The transfer function and Bode plots are used to design and improve the stability of the LCL filter with its damping components. The selected values of Cf, Rf, Li, and Lg as presented in Table 1 have been modelled in Simulink, and stability analyses have been performed as shown in Figure 6b to validate the reliability of the LCL filter. The effective resonance suppression obtained in the design ensures sufficient harmonic attenuation to meet power quality standards and maintains compatibility with the bandwidth requirements of the control loop. This balance ensures the filter enhances both the stability and performance of grid-connected inverter systems under a wide range of operating conditions.

4.1.2. Phase-Locked Loop (PLL) Modelling

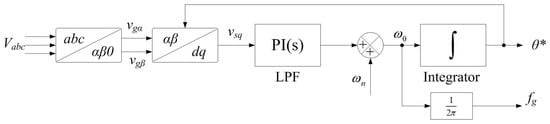

The modelled GFLI is controlled using the synchronous reference frame Phase-Locked Loop (SRF-PLL), which is a widely adopted method for three-phase systems. The block diagram of the implemented PLL is shown in Figure 7, where the three-phase grid voltages (Vabc) are first transformed into a rotational reference frame. The rotational frame is further converted into a stationary frame through a dq transformation. The direct (d) and quadrature (q) components obtained from this transformation are used for active and reactive power control, respectively. This conversion process is analogous to the one used in Space Vector Modulation (SVM), where the abc components are first transformed into the αβ stationary frame using the Clarke transformation, and then further into the dq frame using the Park transformation. Once the reference frame transformation is complete, the estimated phase angle of the utility grid (θ*) is fed back to the Park transformation to ensure accurate compensation of the dq components [37,38,39].

Figure 7.

Block diagram of SRF-PLL.

The SRF-PLL is proposed to be operated in unbalanced grid voltages, where the transformation components generate twice the fundamental grid frequency that can be used in phase detectors. The Park transformation voltage coefficients represent direct and quadrature components as two-axis output, and the estimated phase angle is identical to the phase angle of the grid under balanced and undistorted grid conditions. In these operating conditions, Vd would be equal to the magnitude of the grid voltage, while Vq represents zero as depicted in the following equations. SRF-PLL is designed to operate effectively under unbalanced grid voltage conditions. In such scenarios, the transformation components produce frequency components at twice the fundamental grid frequency, which can be utilized in the phase detection process. The Park transformation coefficients represent the direct (Vd) and quadrature (Vq) components as two-axis outputs. The estimated phase angle aligns precisely with the grid phase angle under balanced and undistorted grid conditions. In these ideal operating conditions, Vd corresponds to the magnitude of the grid voltage, while Vq equals zero, as illustrated in the following equations. This characteristic ensures accurate phase tracking and stability even under challenging grid conditions [37,39];

Figure 8 illustrates the operation of the SRF-PLL controller in synchronizing with the grid that is modelled in Simulink. It shows the main signals measured and processed during the operation of the SRF-PLL, which include the grid voltages, the derived phase angle (θ), and the voltage components in the stationary αβ-reference frame. The three-phase grid voltages (Vabc) are presented in their original sinusoidal form. These voltages are the input to the SRF-PLL and serve as the basis for phase synchronization. The grid voltages are transformed from the three-phase system to the stationary two-phase αβ-reference frame using the Clarke transformation.

Figure 8.

Output measurements of the PLL controller.

This step produces the orthogonal components Vα and Vβ, which are shown in the third axis of the figure as sinusoidal and cosine-like waveforms, respectively. These components serve as inputs to the PLL controller. The PLL extracts the phase angle (θ) of the grid voltage by processing the Vαβ components. This derived phase angle is critical for synchronizing the inverter with the grid and ensuring proper alignment for current injection. The phase angle is depicted as a continuously increasing signal by representing the time-dependent position of the rotating reference frame. The figure also highlights the feedback nature of the SRF-PLL, where the derived phase angle (θ) is used to generate the dq-axis transformation matrix, which ensures accurate phase tracking. The control loop maintains synchronization by minimizing the error between the projected Vd component and zero.

5. Analysis and Case Studies

The modelled power system is subjected to various operating conditions to test its capabilities and to evaluate the performance of the proposed control scheme comprehensively. The first scenario examines steady-state operation under nominal grid conditions. In this case, the GFLI operates with fixed active (P) and reactive (Q) power references that allow for the measurement of power tracking accuracy and steady-state errors. The metrics, such as THD of the injected current, are also evaluated to assess compliance with power quality standards. The second scenario involves dynamic power changes, where the active and reactive power setpoints are varied in steps to evaluate the transient response of the controller. The system’s ability to track changes with minimal overshoot, fast settling time, and accurate tracking is assessed. This scenario demonstrates the effectiveness of control systems in handling load variations or shifts in power demand.

In the third scenario, grid disturbances are introduced to test the robustness of the control system. The voltage sags, where the grid voltage is reduced to 80% of its nominal value, are simulated to analyze the ability of GFLI to maintain stability and regulate power under adverse conditions. Additionally, harmonic distortions in the grid voltage are modelled to evaluate the disturbance rejection capabilities of the controller and its impact on the current waveform quality. The fourth scenario relies on frequency deviations where the grid frequency, ranging between 49 Hz and 52 Hz, is applied to test the robustness of the PLL and the synchronization mechanisms of the system.

Scenario 1: Steady-state operation under nominal grid conditions.

Scenario 2: Performance under grid disturbances (e.g., voltage sags/swells).

Scenario 3: Dynamic response to sudden load deviations.

Scenario 4: Efficiency in grid-following operation under frequency deviation.

5.1. Scenario 1: Steady-State Operation Under Nominal Grid Conditions

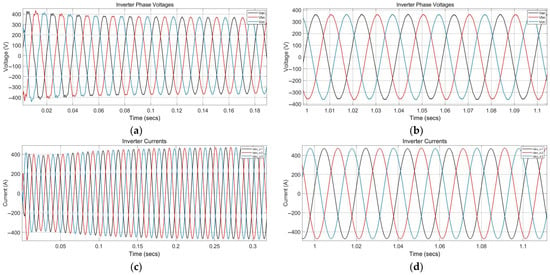

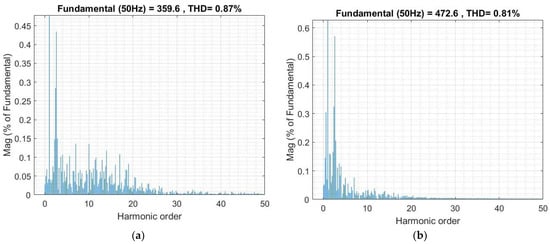

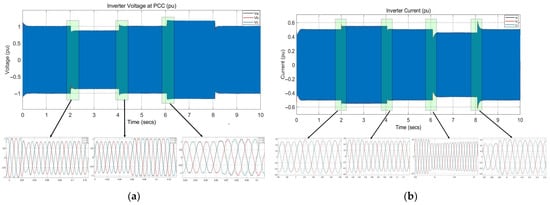

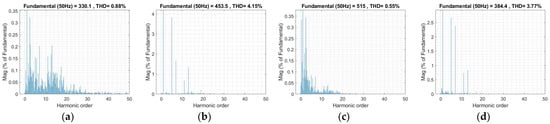

In this case study, the system is operated with a nominal 380 V grid-line voltage and a 50 Hz line frequency. The active power (P) and reactive power (Q) setpoints are fixed at predefined values: P = 250 kW and Q = 50 kVAr. The inverter injects power into a balanced three-phase grid without significant variations in grid conditions or load demands. Figure 9 illustrates the voltage and current waveform analysis of the GFLI connection at the PCC. The short transient intervals seen in Figure 9a,c confirm the rapid response of the proposed controller, while the steady-state measurements denote the reliability and uniform structure of voltage and current waveforms. The power quality performance of the proposed controller has been analyzed with THD measurements that run up to the 50th order of harmonics to cover the switching frequency spectrum, as shown in Figure 10. The THD ratio of voltage during the grid connection is observed to be around 0.87% while the THD of the line current is 0.81%. The comparison of THD ratios to the other methods proposed in the literature is presented in the following sections.

Figure 9.

Output voltage and current analyses of the GFLI at the grid connection: (a) transient response of voltage; (b) voltage waveforms in steady state; (c) transient response of current; and (d) current waveforms in steady state.

Figure 10.

Spectrum of the GFLI: (a) voltage THD (359.6 V), and (b) current THD (472.6 A).

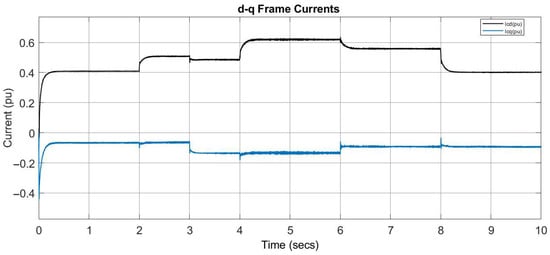

Figure 11 depicts the d- and q-axis components of the filter current (iL) responses of the grid-connected inverter with the IMC method. The id current stabilizes around 0.5 per unit (pu), indicating that the system is successfully delivering the desired amount of active power to the grid. This steady value reflects efficient control of active power flow. The iq current stabilizes at approximately −0.1 pu, suggesting a controlled exchange of reactive power where the negative sign indicates that reactive power is injected into the grid depending on the system requirements. The id and iq currents in this system demonstrate good transient performance, proper decoupling, and stable operation, ensuring effective active and reactive power control in the grid-connected inverter.

Figure 11.

The d- and q-axis components of the filter current.

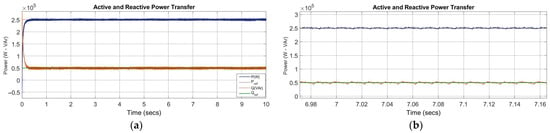

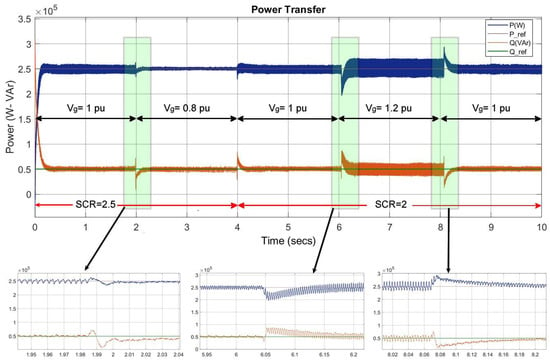

Figure 12 illustrates the P and Q exchange over time in the grid-connected operation of the IMCled inverter with the respective reference values (Pref and Qref). The active power quickly reaches its steady-state value by matching the reference closely without any noticeable overshoot or oscillation due to its stable system response with fast dynamics. The green line (Qref) shows the reference for reactive power, while the brown line (Q) represents the actual reactive power delivered to the grid. The reactive power closely tracks the reference with minimal error and stabilizes quickly. Both P and Q measurements exhibit smooth and rapid transient responses, reaching steady-state values within approximately 100 ms. The detailed measurements of active and reactive power are shown in Figure 12b, where each one closely tracks the reference values with minimum ripple rates. The steady-state operation under nominal grid conditions of the control system demonstrates minimal steady-state error, low THD in the output current and output voltages, and stable operation under nominal grid conditions. The presented analyses confirm the reliability of the proposed control to ensure the compliance of the controlled inverter with grid interconnection standards.

Figure 12.

Power exchange analysis of the GFLI. (a) Active and reactive power measurement; (b) zoomed view of a particular instant.

5.2. Scenario 2: System Performance Under Grid Disturbances

In the second case study, the system is operated with a voltage sag by reducing the grid voltage to 80% of its nominal value for 2 s, and then a voltage swell is introduced by increasing the grid voltage to 120% of its nominal value for 2 s after the 3rd second of restoration. The active power (P) and reactive power (Q) setpoints are fixed at predefined values: P = 250 kW and Q = 50 kVAR, as in the first scenario. Figure 13a represents GFLI voltages, while Figure 13b denotes the current waveforms measured in the grid disturbance scenario. The GFLI is operated at normal grid conditions from [0–2s] at the first interval, and the voltage waveforms are observed to be stable and sinusoidal with an amplitude of 1 pu during this period. The inverter operates under nominal grid conditions without disturbances, which ensures balanced three-phase output voltages (Va, Vb, Vc). At t = 2 s, a voltage sag is introduced by reducing the voltage magnitude to 0.8 pu to simulate a grid disturbance such as a fault or a sudden increase in load demand. The zoomed-in plot highlights the reduced amplitude of all three-phase voltages while maintaining their sinusoidal nature and synchronization. The internal model-based controller compensates for the disturbance by ensuring stable operation during the sag. After the sag, the voltage amplitudes were restored to 1 pu at t = 4.05 s, which indicates a return to nominal grid conditions. The zoomed-in plot during this interval shows smooth transitions back to sinusoidal voltages without overshoots or oscillations owing to the strong transient stability of the system. At t = 6.1 s, a voltage swell is introduced to the system by increasing the voltage magnitude to 1.2 pu.

Figure 13.

Output voltage and current analyses of the GFLI under grid disturbances. (a) Transient response of voltage; (b) transient response of current.

This disturbance mimics scenarios such as a sudden reduction in load or a grid switching event. The zoomed-in plot reveals an increase in amplitude across all three phases while maintaining sinusoidal waveforms. The controller effectively mitigates the potential instability caused by the swell and ensures the inverter remains synchronized with the grid, as shown in the last scope of Figure 13a. After the swell, the voltage amplitude returns to 1 pu at t = 8.1 s, which indicates the system’s ability to restore nominal operation post-disturbance. The smooth recovery of waveforms shows the ability of the system to maintain power quality and stability. Across all scenarios, the GFLI maintains sinusoidal waveforms for the three-phase voltages, even during sag and swell conditions. The phase alignment between the three-phase voltages is maintained throughout the disturbance events, confirming that the internal model-based controller ensures grid synchronization. The controller also adapts the current amplitude in response to voltage disturbances by increasing it during sags and reducing it during swells. This adjustment highlights the robustness of the internal model-based controller in regulating power flow and maintaining system performance under varying grid conditions, as shown in Figure 13b.

The THD analyses of the GFLI have been performed to observe the power quality of grid-connected operation under various disturbances. The voltage and current THD ratios are shown in Figure 14a,c during the voltage sag disturbances. The measured values (THDV = 0.88% and THDI = 0.55%) validate that the proposed controller ensures stable and reliable operation under voltage sag conditions, and the measured harmonic rates comply with international standards of IEEE and IEC. On the other hand, the THD values of inverter voltage and currents under voltage swell disturbances are obtained at 4.15% and 3.77%, as seen in Figure 14b and Figure 14d, respectively.

Figure 14.

Spectrum analyses of the GFLI. (a) THDV during voltage sag; (b) THDV during voltage swell; (c) THDI during voltage sag; and (d) THDI during voltage swell.

Figure 15 illustrates the P and Q exchange between the inverter and the grid during scenarios involving an 80% voltage sag and a 120% voltage swell. The analysis also compares the actual power (P, Q) with the reference power values (Pref and Qref). During normal operation, the active power output tracks the reference value (Pref) closely at approximately 0.5 pu. The reactive power output remains near 0.1 pu with zero shift from the reference value. The steady and precise tracking of reference values confirms the efficiency of the proposed controller under nominal conditions. At t = 2.02 s, the grid voltage drops significantly and causes a transient dip in active power. The zoomed-in section reveals that active power output momentarily decreases due to the sudden voltage drop, but quickly recovers to track Pref in around 50 ms. Reactive power output experiences a sharp transient spike, which reflects the controller’s reactions to stabilize voltage and support the reactive power demand during the sag period. The spike decays rapidly and returns to the Qref value as the system stabilizes around 60 ms, similarly to active power control. Another screenshot seen at t = 6 s denotes the starting period of the voltage swell. The grid voltage increases to 120% of the nominal value, which causes a transient overshoot in active power output. The zoomed-in section shows that the controller manages to suppress the overshoot, restoring the active power to its reference value within a short duration of 40 ms. Like the voltage sag, the swell induces a transient spike in reactive power that compensates for the overvoltage and quickly settles back to the reference value. In order to test the IMC in weak grid conditions, the grid SCR has been set to 2 and 2.5 in these analyses.

Figure 15.

Power exchange analysis of the GFLI during voltage disturbances.

The power response during both sag and swell demonstrates strong transient stability. The active power exhibits minimal overshoot or undershoot and closely tracks the reference values after disturbances. The reactive power spikes during disturbances indicate the ability of the inverter to provide dynamic voltage support. These transient responses play a critical role in stabilizing the grid under sag and swell conditions. The analysis demonstrates that the inverter controlled with its internal model-based controller successfully manages voltage disturbances while ensuring stable and reliable active and reactive power exchange with the grid. The system exhibits a remarkable ability to respond dynamically to both voltage sags and swells, as evidenced by the rapid recovery of power outputs to their reference values. This capability minimizes the impact of transients on the grid and ensures consistent operation under varying conditions.

5.3. Scenario 3: Dynamic Response to Sudden Load Deviation

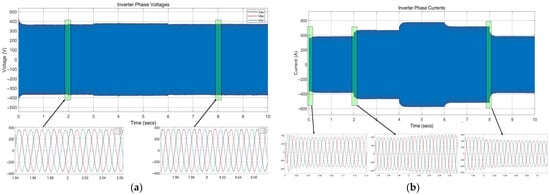

In the third case study scenario, the system is operated with varying load values in terms of both active and reactive power. The active power has been shifted to [200 kW, 250 kW, 320 kW, 280 kW, and 200 kW] at [0 s, 2 s, 4 s, 6 s, and 8 s] of the simulation while the reactive power was shifted to [60 kVAr, 100 kVAr, and 75 kVAr] at [0 s, 3 s, and 6 s] intervals. Figure 16a represents the inverter voltages, while Figure 16b denotes the current waveforms measured in the load change scenario. The GFLI is operated at normal grid conditions with 200 kW active and 60 kVAr reactive power demand in [0–2s] at the first interval. The inverter operates under nominal grid conditions without disturbances, which ensures balanced three-phase output voltages (Va, Vb, Vc). At t = 2 s, an increment in active power is introduced by increasing the P to 250 kW in load demand, which is followed by a 320 kW active power demand at t = 4 s. The first zoomed-in plot highlights that there is no remarkable variation in the inverter current as seen in Figure 16a. The internal model-based controller compensates for the sudden load changes by ensuring stable operation during the increasing power demand. At t = 3 s, the reactive power demand is increased to 100 kVAr as seen in the voltage and current measurements of Figure 16a,b, respectively. The zoomed-in plot during this interval shows a smooth increment in the inverter voltages without overshoots or oscillations owing to the strong transient stability of the system.

Figure 16.

Output voltage and current analyses of the GFLI at grid connection. (a) Transient response of voltage; (b) transient response of current.

At t = 6 s, a remarkable load disconnection is introduced to the system by decreasing the active power from 320 kW to 280 kW and decreasing the reactive power from 100 kVAR to 75 kVAR. The zoomed-in plot of Figure 16b reveals a decrease in current amplitude across all three phases while maintaining sinusoidal waveforms. Despite the abrupt load reduction, the inverter maintains synchronization with the grid as evidenced by the smooth waveforms and steady operation in the final segment of Figure 16b. At t = 8 s, the active power demand drops further to 200 kW, and the inverter responds swiftly and smoothly by ensuring stability and consistent output voltages.

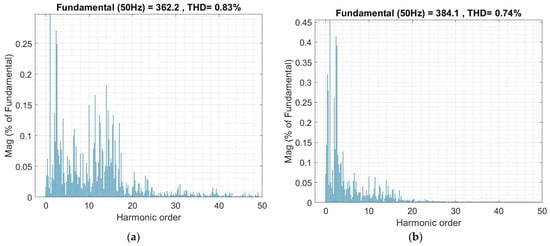

The THD analyses of the GFLI have been performed to observe the power quality of grid-connected operation under various load profiles. The voltage and current THD ratios have been shown in Figure 17. The two voltage and current THD measurements shown in the figure are for the highest load intervals between 4 s and 6 s. The measured THDV = 0.83%, shown in Figure 17a, is obtained under 320 kW and 100 kVAr load. The THD ratio of the GFLI current is measured as THDI = 0.74%, as shown in Figure 17b. The measurements validate that the proposed controller ensures stable and reliable operation under varying load conditions, and the measured harmonic rates comply with international standards of IEEE-519 and IEC 61000 [40,41].

Figure 17.

Spectrum of the GFLI. (a) THDV at max load; (b) THDI at max load.

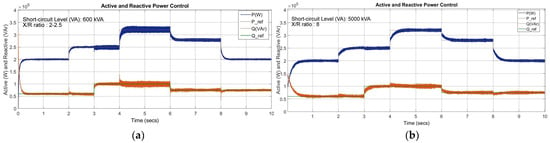

Figure 18 illustrates the scenario involving sudden load deviations that are reflected in the sharp transitions observed in both P and Q. These abrupt shifts represent the instantaneous change in load demand and operating conditions, which the GFLI must respond to effectively. The analysis also compares the actual power (P, Q) with the reference power values (Pref and Qref) as presented above. At specific time intervals (e.g., 2, 4, 6, and 8 s), there are noticeable steps in the active power output. Each sudden change corresponds to a new steady-state load level. The system rapidly adjusts the active power to match the new reference value (Pref) with minimal overshoot or oscillations. In Figure 18a, the inverter operates under a weak grid condition characterized by a low short-circuit level of 600 kVA that corresponds to an SCR of approximately 1.5, with the X/R ratio varying between 2 and 2.5. Under these conditions, the grid impedance is relatively high and predominantly resistive, which amplifies the interaction between the inverter control loops and the grid. As observed, the active power tracks its reference with acceptable steady-state accuracy. The reactive power response exhibits transient deviations and slower damping by indicating relatively reduced robustness of the GFL control in weak grids. These effects are mainly attributed to the strong coupling between the PLL dynamics, grid impedance, and current control loop, which becomes more pronounced as the SCR decreases.

Figure 18.

Power exchange analysis of the GFLI during sudden load deviations. (a) Weak grid conditions (SCR = 1.5); (b) strong grid conditions (SCR = 12.5).

On the other hand, Figure 18b depicts the GFLI behaviour under a stiff grid condition, where the short-circuit level is increased to 5000 kVA, corresponding to an SCR of approximately 12.5 with a higher X/R ratio of 8. In this case, the grid appears much stronger from the GFLI perspective, which results in reduced sensitivity to control-grid interactions. Both active and reactive power responses demonstrate faster settling times, reduced overshoot, and significantly lower ripple compared to the weak-grid case. The inverter closely follows the reference power commands across all operating intervals, and transient disturbances are rapidly attenuated. This confirms that a higher SCR effectively improves system damping and mitigates adverse PLL-induced interactions.

Despite operating under a very weak grid condition (SCR ≈ 1.5 with a low X/R ratio of 2–2.5), as shown in Figure 18a, the results clearly demonstrate the reliability and robustness of the proposed GFLI control strategy. The inverter remains fully synchronized with the grid throughout the entire simulation with no evidence of LOS or control instability, even during multiple step changes in active and reactive power references. This is a critical indicator of reliable operation in weak grids, where PLL–grid interactions often lead to instability. The active power response consistently tracks the reference commands at all operating intervals. Although increased ripple and transient oscillations are observable, which is an expected characteristic in low-SCR systems, the power response remains bounded, well-damped, and free of sustained oscillations. The absence of growing oscillatory modes confirms that the closed-loop system preserves adequate stability margins under weak-grid conditions.

On the other hand, the reactive power control exhibits stable and repeatable behaviour with transient deviations quickly settling to their commanded values. Even with a resistive-dominant grid (low X/R ratio), the controller prevents excessive coupling between active and reactive channels, demonstrating effective decoupling and robust current regulation. The observed oscillations in Figure 18a are non-divergent and decay rapidly, indicating that the system operates well within its small-signal stability limits despite the reduced SCR. This confirms that the IMC-based PI tuning enhances robustness against grid impedance uncertainty and PLL sensitivity, which are typically the primary sources of instability in weak grids.

Figure 18 validates that the proposed control scheme enables reliable, stable, and resilient GFLI operation under severe weak-grid conditions, maintaining acceptable power quality and control performance even at SCR values where conventional GFLI controllers are prone to instability.

5.4. Scenario 4: Efficiency of Grid-Following Operation Under Frequency Deviations

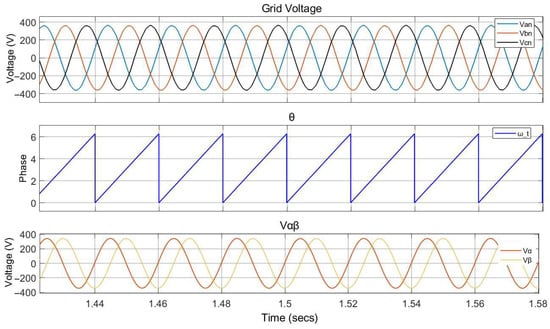

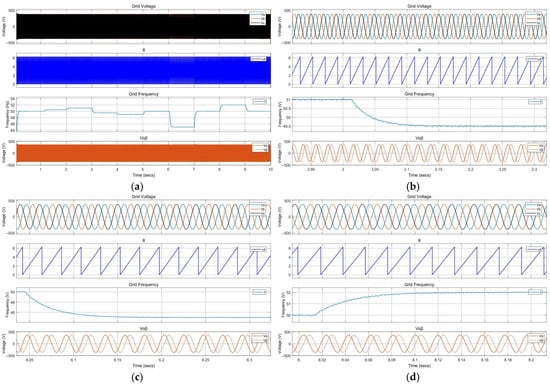

In the fourth case study scenario, the system performance is evaluated under varying grid frequency conditions to test the reliability and stability of both the PLL and internal model-based control algorithms. The grid frequency is intentionally perturbed by decreasing to 49 Hz and subsequently increasing to 52 Hz, simulating realistic grid disturbances that can occur in practical operations. This dynamic frequency variation is introduced to analyze how effectively the PLL maintains synchronization and how well the IMC adapts to these changes without compromising the system stability or control accuracy. The test intentionally introduces a controlled frequency deviation. Figure 19 illustrates the dynamic performance of the PLL of the grid-following inverter under various grid frequency deviation scenarios, demonstrating the robustness of the synchronization mechanism over a wide frequency range.

Figure 19.

PLL operation against frequency deviation tests. (a) Frequency deviations (fg = [50, 50.5, 51, 49.5, 49, 50, 45, 50, 52, 50] Hz); (b) frequency sag (fg = 51 Hz to 49.5 Hz); and (c) frequency sag (fg = 50 Hz to 45 Hz); (d) frequency swell (fg = 50 Hz to 52 Hz).

Figure 19a presents the PLL response to a sequence of discrete grid frequency variations, where the grid frequency is successively changed among fg = [50, 50.5, 51, 49.5, 49, 50, 45, 50, 52, 50] Hz. This test represents operating conditions in low-inertia power systems, where frequency fluctuations occur due to load–generation imbalance. The PLL accurately tracks each frequency step without exhibiting sustained oscillations or loss of synchronization. The estimated frequency rapidly converges to the imposed grid frequency following each change, indicating fast dynamic response and strong damping characteristics. Figure 19b depicts a moderate frequency sag scenario in which the grid frequency decreases from 51 Hz to 49.5 Hz. The PLL smoothly follows this downward frequency transition with minimal transient deviation. The absence of overshoot and the short settling time confirm that the PLL is properly tuned to handle typical under-frequency events while maintaining stable phase tracking.

A severe frequency sag scenario, in which the grid frequency decreases from 50 Hz to 45 Hz, is depicted in Figure 19c. The PLL maintains stability and precisely tracks the grid frequency in spite of this significant variance. The fast and deep frequency change causes an increased transient response, but the PLL rapidly stabilizes without oscillating, showing a high degree of robustness against severe under-frequency situations. Figure 19d illustrates a frequency swell scenario, with the grid frequency increasing from 50 Hz to 52 Hz. The PLL effectively follows the frequency increase, achieving rapid convergence to the new operating point. The response remains smooth and well-damped, with no evidence of instability or excessive phase error.

A frequency swell scenario is shown in Figure 19d, where the grid frequency rises from 50 Hz to 52 Hz. The PLL quickly settles to the new operating point by efficiently following the frequency increase. The response is smooth and well-damped without any sign of instability or severe phase error. Thus, the results in Figure 19 show that the PLL used in the proposed GFLI control scheme performs reliably and robustly even under moderate and severe frequency variations. The PLL ensures perfect synchronization over a wide frequency range, which is required for steady grid-following performance in modern power systems with low inertia and frequent frequency changes.

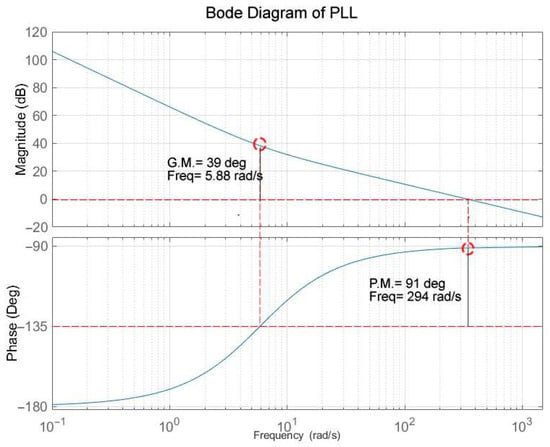

The Bode diagram in Figure 20 illustrates the frequency-domain characteristics of the PLL employed in the GFLI. It can be observed from the magnitude plot that the PLL exhibits a high gain at low frequencies, which ensures accurate tracking of slow variations in grid phase and frequency. As the frequency increases, the magnitude response decreases with a characteristic roll-off that indicates effective attenuation of high-frequency disturbances and measurement noise. The gain crossover frequency is identified at approximately 5.88 rad/s, where the magnitude crosses the 0 dB line. At this frequency, the reported gain margin of approximately 39 dB indicates that the PLL possesses sufficient robustness against gain variations and modelling uncertainties.

Figure 20.

Frequency-domain stability analysis of the PLL in the GFLI.

The phase plot shows a smooth phase transition from nearly −180° at low frequencies toward higher phase values as the frequency increases. The phase crossover occurs at around 294 rad/s, where the phase reaches −180°. At this point, the system exhibits a phase margin of approximately 91 degrees, which reflects a well-damped PLL response with a low tendency toward oscillatory behaviour. Such a large phase margin implies strong stability reserves and reduced sensitivity to parameter variations. The PLL design achieves a careful balance between fast synchronization and robust stability. The relatively low bandwidth, as indicated by the low gain crossover frequency, helps limit the interaction between the PLL and the inner current control loop, which is particularly important in weak-grid (low SCR) scenarios. At the same time, the large phase and gain margins confirm that the PLL is conservatively tuned, which reduces the risk of loss of synchronization and adverse coupling with inverter current dynamics. The presented Bode characteristics demonstrate that the PLL is well-suited for GFLI operation in low-inertia and weak-grid environments.